Abstract

Background

Beta-2 microglobulin (β2M) accumulates in hemodialysis (HD) patients, but its consequences are controversial, particularly in the current era of high-flux dialyzers. High-flux HD treatment improves β2M removal, yet β2M and other middle molecules may still contribute to adverse events. We investigated patient factors associated with serum β2M, evaluated trends in β2M levels and in hospitalizations due to dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA), and estimated the effect of β2M on mortality.

Methods

We studied European and Japanese participants in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Analysis of DRA-related hospitalizations spanned 1998–2018 (n = 23 976), and analysis of β2M and mortality in centers routinely measuring β2M spanned 2011–18 (n = 5332). We evaluated time trends with linear and Poisson regression and mortality with Cox regression.

Results

Median β2M changed nonsignificantly from 2.71 to 2.65 mg/dL during 2011–18 (P = 0.87). Highest β2M tertile patients (>2.9 mg/dL) had longer dialysis vintage, higher C-reactive protein and lower urine volume than lowest tertile patients (≤2.3 mg/dL). DRA-related hospitalization rates [95% confidence interval (CI)] decreased from 1998 to 2018 from 3.10 (2.55–3.76) to 0.23 (0.13–0.42) per 100 patient-years. Compared with the lowest β2M tertile, adjusted mortality hazard ratios (95% CI) were 1.16 (0.94–1.43) and 1.38 (1.13–1.69) for the middle and highest tertiles. Mortality risk increased monotonically with β2M modeled continuously, with no indication of a threshold.

Conclusions

DRA-related hospitalizations decreased over 10-fold from 1998 to 2018. Serum β2M remains positively associated with mortality, even in the current high-flux HD era.

Keywords: β2M, dialysis, high flux dialysis, dialysis-related amyloidosis, ESRD

INTRODUCTION

Beta-2 microglobulin (β2M) is a protein expressed on the surfaces of all nucleated cells; it is a middle molecule (molecular weight, 11.8 kDa) and a light-chain component of the major histocompatibility Class I molecules associated with the heavy-chain components on cell surfaces. Excess β2M forms fibrillar structures and amyloid deposits [1], primarily in osteoarticular structures and the viscera [2, 3]. β2M accumulation in the blood has been associated with a decrease in residual kidney function [4–6] and an increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and infectious deaths [7–11].

β2M clearance has long been a surrogate for middle-molecule clearance among patients receiving hemodialysis (HD) [12]. The combination of declining residual kidney function and a low rate of β2M removal by low-flux cuprophane and cellulose acetate dialysis membranes did not provide sufficient β2M reduction [13]. This impaired β2M clearance became associated with a higher risk of dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA), a rare but devastating complication resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), organ deposition of amyloid deposits, and a painful and debilitating arthropathy. In addition to the DRA-related increased hospitalization rates and quality of life issues observed during the utilization period of these membranes, β2M accumulation potentially contributed to morbidity and mortality from other causes.

In contrast, modern HD therapy includes the use of highly permeable and high-flux membranes that enhance β2M clearance. Yet dialysis treatment itself may increase β2M production by acting as an inflammatory stimulus; this may vary by membrane type and dialysate buffer (acetate versus bicarbonate) and the use of ultrapure dialysate [2, 14]. The combined use of ultrapure dialysates and advanced biocompatible membranes is thought to help reduce inflammation and β2M production [15, 16].

Although the incidence of DRA has decreased over time [17], the resulting impact of increasing β2M removal remains controversial. The Hemodialysis (HEMO) study did not show a beneficial effect of high-flux dialyzers on all-cause deaths [18]; however, a subanalysis indicated that their use was associated with decreased risk of death in patients with longer vintage [19]. On the other hand, the Membrane Permeability Outcome study of only incident patients showed that the use of high-flux membranes conferred a significant survival benefit among patients with serum albumin ≤4 g/dL and in a post hoc analysis in the subset of patients with diabetes [20].

These findings call for a better understanding of the impact of β2M levels on the mortality of dialysis patients. This is particularly salient in the modern era of high-flux HD where direct β2M-related toxicity appears to be decreasing in response to enhanced β2M clearance. If higher β2M levels remain associated with increased risk of other adverse outcomes, then further reduction may be an important therapeutic target in the management of chronic HD patients. The most compelling results will require analyses of data from large national samples of HD patients who received β2M measurement as part of routine care, an uncommon situation. Our data and approach uniquely support this study’s objectives to identify patient factors associated with serum β2M level, evaluate trends over time in β2M levels and DRA-related hospitalizations, and estimate the effect of β2M on mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dataset

We examined data from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). The DOPPS (http://www.dopps.org) is an international prospective cohort study of HD patients ≥18 years of age. At the start of each study phase, DOPPS enrolls random samples of patients from stratified, national random samples of dialysis facilities, with departing patients replaced as described previously [21–23].

We analyzed DOPPS patients from Japan and Europe (France, Italy and Spain). Analysis of DRA included DOPPS Phases 1–6 (1998–2018), while analysis of β2M used Phases 4–6 (2011–18) as β2M measures were not collected in previous DOPPS phases. Individual patients enrolled in multiple study phases may be represented multiple times.

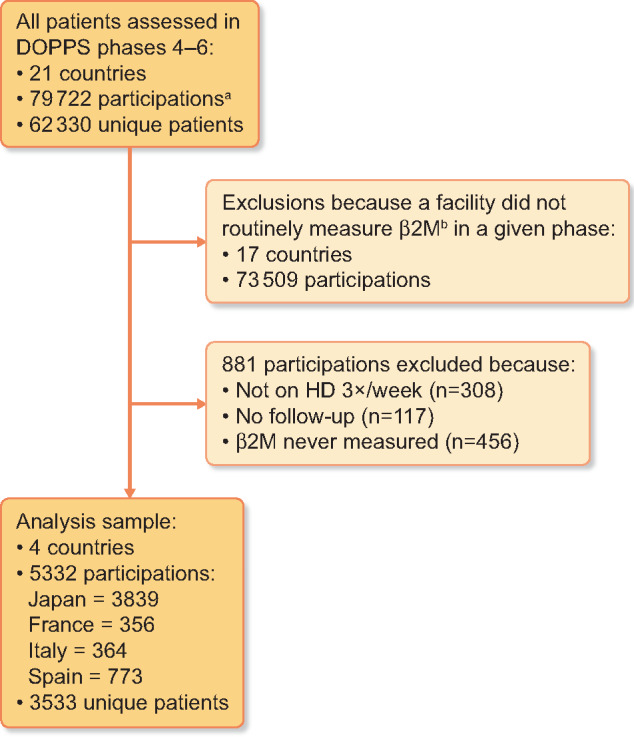

For inclusion in our analyses of β2M in DOPPS Phases 4–6, we identified 5332 patient measures from 3533 individuals in 77 HD facilities in Japan (n = 3839) and Europe (n = 1493; France n = 356, Italy n = 364 and Spain n = 773; Figure 1). β2M values were obtained via predialysis blood test. Over 70% of these samples were collected in Japan, where β2M measurement is now routine at many HD centers. For analysis of DRA in Phases 1–6, we identified 23 976 patient measures from 336 HD facilities in Japan (n = 9081) and Europe (n = 14 895).

FIGURE 1:

Patient flow diagram for β2M analyses.

aNumber of participations represents patient phases; unique individuals may have data in one, two or three phases, thus contributing up to three participations. In our analysis, patients’ data are considered independent across phases.

bWithin each phase, a facility was determined to ‘routinely measure β2M’ if ≥50% of patients had β2M reported in ≥50% of patient rounds.

Patient medical record abstraction provided demographic data, comorbid conditions, laboratory values and dialysis treatment parameters. We collected mortality and hospitalization events during study follow-up. To reduce confounding from the presence of residual kidney function in the DRA analysis, we restricted the sample to patients dialyzing for at least 1 year. To reduce bias from measurement-by-indication in analyses of β2M, in each phase we restricted to sites that routinely measured β2M; this was defined as ≥50% of patients having β2M levels reported in ≥50% of their 4-month follow-up visit intervals.

A central Institutional Review Board approved each study phase. We obtained additional study approvals and informed patient consents as required by national and local ethics regulations.

Statistical analyses

For β2M analyses, we ascertained baseline patient characteristics as of the date of β2M measurement. We employed linear regression to evaluate a time trend in β2M levels across DOPPS Phases 4–6, adjusting for age, sex, dialysis vintage, diabetes diagnosis and region (Japan or Europe). We chose generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with exchangeable working correlation structure to account for patients clustered in facilities. Assessment of DRA-related hospitalization rates across DOPPS Phases 1–6 was achieved with Poisson regression, both unadjusted and adjusted as in the linear model above, and using GEE with independent working correlation structure. We defined DRA-related hospitalizations as those where the identified cause was listed as DRA or CTS.

Cox regression was used to estimate the association [hazard ratio (HR), 95% confidence interval (CI)] between tertile categories of baseline β2M and all-cause mortality in Phases 4–6. We adjusted for baseline age, sex, dialysis vintage, region, DOPPS phase, residual urine volume (≥200 or <200 mL/day), serum albumin and five comorbidities (diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and other cardiovascular diseases). We fit models using all patients and in prespecified subgroups based on region, residual urine volume (≥200 or <200 mL/day) and dialysis modality [hemodiafiltration (HDF) or HD]. We also fit a Cox model where β2M was used continuously, coding it as a natural cubic spline with knots at 1.7, 2.3, 2.9 and 3.5 mg/dL, corresponding approximately to the 10th, 33rd, 67th and 90th percentiles; adjustments were as in the model with categorical β2M. Patient clustering within facilities was accounted for with the robust sandwich covariance estimator [24]. Time at risk for all Cox models began at baseline and ended at death or last date of study follow-up.

We used multiple imputations, implemented by IVEware [25], to impute missing covariate values for the survival analyses. Overall, missingness was low, at <2% for all covariates except for Kt/Vurea (11%) and residual urine volume (12%). We imputed 20 complete data sets, performed all Cox regressions with each data set and combined the results using Rubin’s rules [26]. All analyses used SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

In a cross-sectional, unadjusted analysis, patients in the highest β2M tertile (>2.9 mg/dL) had longer dialysis vintage, greater likelihood of urine volume <200 mL/day, lower prevalence of diabetes, and higher levels of serum creatinine, phosphorus and C-reactive protein (CRP) than patients in the middle (2.3–2.9 mg/dL) and lowest (≤2.3 mg/dL) β2M tertiles (Table 1). We observed little association between β2M and HD treatment time or catheter use. Among patients using HDF, patients in the highest β2M tertile tended to have lower replacement fluid volume than patients in the middle and lowest tertiles.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to β2M tertile, by region

| Characteristics | Europe |

Japan |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest (n = 591) | Middle (n = 374) | Highest (n = 528) | Lowest (n = 1214) | Middle (n = 1426) | Highest (n = 1199) | |

| Male, % | 65 | 59 | 62 | 70 | 67 | 63 |

| Age, years | 67 ± 15 | 69 ± 15 | 66 ± 15 | 66 ± 12 | 65 ± 12 | 65 ± 12 |

| Vintage, years | 3.2 ± 5.0 | 5.0 ± 5.9 | 6.0 ± 6.9 | 4.2 ± 7.7 | 8.0 ± 7.6 | 8.6 ± 7.0 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26 ± 5 | 26 ± 5 | 25 ± 5 | 22 ± 4 | 22 ± 3 | 21 ± 4 |

| Pain (self-report, higher is less pain)a | 61 ± 32 | 50 ± 32 | 55 ± 31 | 70 ± 30 | 67 ± 29 | 65 ± 31 |

| Urine volume <200 mL/day, % | 54 | 73 | 80 | 61 | 80 | 89 |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||||

| Kt/Vurea | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Treatment time, h | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.4 |

| HDF, % | 26 | 32 | 20 | 7 | 13 | 15 |

| Catheter use, % | 33 | 26 | 32 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| HDF replacement fluid volume, % | ||||||

| <4.0 L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 4.0–15.0 L | 10 | 5 | 7 | 33 | 37 | 43 |

| 15.1–20.0 L | 26 | 30 | 41 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| >20.0 L | 64 | 65 | 51 | 59 | 59 | 51 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| β2M, mg/dL | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.5 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 6.9 ± 2.4 | 8.2 ± 2.4 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 8.5 ± 2.6 | 10.8 ± 2.7 | 11.1 ± 2.6 |

| Phosphorus, g/dL | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.5 |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 304 ± 286 | 333 ± 330 | 324 ± 337 | 180 ± 189 | 164 ± 167 | 163 ± 148 |

| TSAT, % | 26.4 ± 12.0 | 26.6 ± 12.1 | 27.0 ± 12.7 | 24.5 ± 11.6 | 25.5 ± 12.2 | 23.6 ± 12.5 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 420 ± 399 | 429 ± 307 | 495 ± 436 | 135 ± 193 | 143 ± 232 | 152 ± 271 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.5 ± 1.5 | 11.6 ± 1.5 | 11.6 ± 1.5 | 10.7 ± 1.2 | 10.6 ± 1.3 | 10.7 ± 1.3 |

| CRP, mg/L | 13.0 ± 32.2 | 10.9 ± 16.8 | 16.2 ± 27.9 | 3.8 ± 14.3 | 4.0 ± 10.6 | 7.5 ± 19.0 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||

| Diabetes | 45 | 32 | 28 | 49 | 39 | 36 |

| Hypertension | 93 | 86 | 83 | 83 | 85 | 81 |

| Coronary heart disease | 32 | 27 | 29 | 27 | 28 | 27 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 14 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 17 | 15 |

| Congestive heart failure | 21 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 19 | 21 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 36 | 37 | 33 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 32 | 35 | 31 | 20 | 26 | 28 |

| Cancer (nonskin) | 12 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| GI bleeding | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Lung disease | 20 | 21 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Neurologic disease | 14 | 14 | 13 | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 18 | 18 | 23 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Recurrent cellulitis or gangrene | 8 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Carpal tunnel | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

β2M tertiles are lowest (≤2.3 mg/dL), middle (2.3–2.9) and highest (>2.9). Characteristics are reported as mean ± SD or %.

Self-reported pain score from the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-36 Survey (KDQOL-36). Note that 44% of patients had missing data for this item.

Across DOPPS Phases 4–6 (2011–18), median [interquartile range (IQR)] β2M changed nonsignificantly from 2.71 mg/dL (2.28–3.14) to 2.67 (2.22–3.12) to 2.65 (2.28–3.05). In adjusted regression, the P-value for linear trend in β2M levels over DOPPS Phases was P = 0.87. The crude rate of DRA-related hospitalizations fell sharply across Phases 1–6 (1998–2018), from 3.10 (95% CI 2.55–3.76) to 0.23 (95% CI 0.13–0.42) hospitalizations per 100 patient-years (Supplementary data, Figure S1). Consistent with the crude rates, the adjusted rate of hospitalizations declined across phases (P < 0.0001).

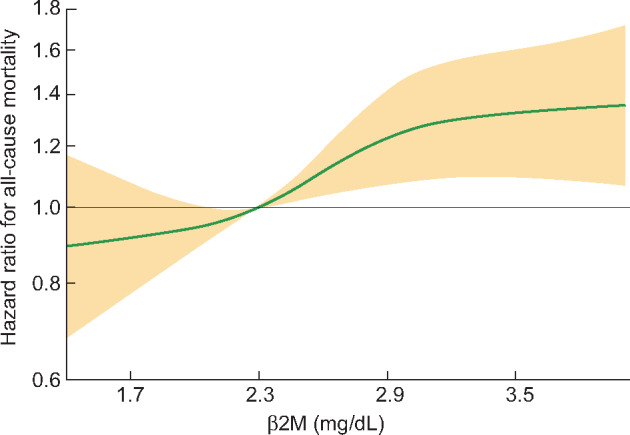

Median (IQR) follow-up time for mortality analyses was 2.2 years (1.5–2.8) in Japan and 1.3 years (0.8–2.1) in Europe. Crude death rates in the lowest, middle and highest β2M tertiles were 4.5, 4.9 and 6.0 deaths per 100 patient-years in Japan and 11.1, 15.1 and 14.9 in Europe. In adjusted Cox regression with data combined across regions, the highest β2M tertile was strongly associated with increased risk of death (HR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.13–1.69) relative to the lowest tertile (Table 2). This finding was replicated within all subgroups. Among patients with urine volume ≥200 mL/day, the associations were notably stronger, with both the highest (HR = 1.96, 95% CI 1.34–2.86) and middle (HR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.04–2.32) tertiles having increased risk of death relative to the lowest. With β2M coded as a spline (Figure 2), the adjusted hazard of death increased monotonically across the range of β2M values. These findings were nearly identical in separate models that additionally adjusted for the dialysis treatment characteristics of Kt/Vurea, treatment time and use of HDF versus HD (Supplementary data, Table S1).

Table 2.

HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality by β2M tertile, relative to the lowest tertile

| Patient group | n | Deaths | HR (95% CI) by β2M tertile |

Interaction P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Middle | Highest | ||||

| All patients | 5332 | 696 | 1 (ref) | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 1.38 (1.13–1.69) | |

| By region | ||||||

| Europe | 1493 | 288 | 1 (ref) | 1.32 (1.00–1.74) | 1.44 (1.09–1.91) | 0.40 |

| Japan | 3839 | 408 | 1 (ref) | 1.11 (0.82–1.50) | 1.32 (1.00–1.75) | |

| By residual urine volume | ||||||

| ≥200 mL/day | 1367 | 139 | 1 (ref) | 1.56 (1.04–2.32) | 1.96 (1.34–2.86) | 0.02 |

| <200 mL/day | 3965 | 557 | 1 (ref) | 1.09 (0.86–1.40) | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) | |

| By dialysis modality | ||||||

| HDF | 823 | 112 | 1 (ref) | 1.04 (0.69–1.56) | 1.30 (0.79–2.15) | 0.65 |

| HD | 4509 | 584 | 1 (ref) | 1.17 (0.93–1.48) | 1.40 (1.12–1.73) | |

Based on Cox regression, adjusting for age, sex, region (Europe or Japan), DOPPS phase, dialysis vintage, residual urine volume (≥200 or <200 mL/day), serum albumin and five comorbidities (diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and other cardiovascular diseases). Interaction P-values test the interactions between β2M and each of region, residual urine volume and dialysis modality (HDF or HD). β2M tertiles are lowest (≤2.3 mg/dL), middle (2.3-2.9) and highest (>2.9).

FIGURE 2:

Adjusted HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality by continuous β2M level, relative to a β2M of 2.3 mg/dL.

Based on Cox regression, with β2M coded as a natural cubic spline with knots at 1.7, 2.3, 2.9 and 3.5 mg/dL, corresponding to the 10th, 33rd, 67th and 90th percentiles of β2M in our sample. Adjusted for age, sex, region (Europe or Japan), DOPPS Phase, dialysis vintage, residual urine volume (≥200 or <200 mL/day), serum albumin and five comorbidities (diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and other cardiovascular diseases). Plot extends between the 5th and 95th percentiles of β2M, that is, between 1.4 and 4.0 mg/dL.

DISCUSSION

In this study, despite the observation of non-significant changes in circulating β2M during DOPPS Phases 4–6 (2011–18), the rate of DRA-related hospitalizations decreased 10-fold across Japan and Europe from 1998 to 2018. Higher serum β2M levels were associated with lower survival rates in both Japan and Europe in analysis of data from the current high-flux dialysis era (2011–18), even with adjustment for numerous patient and dialysis treatment characteristics.

A subanalysis of the HEMO study showed that β2M levels >3.5 mg/dL were associated with a higher risk of death than β2M levels <2.75 mg/dL [9]. The Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) clinical guideline for maintenance HD showed that β2M levels ≥3.0 mg/dL were associated with a higher risk than β2M levels between 2.5 and 3.0 mg/dL [11]. Based on this finding, the JSDT clinical guideline for maintenance HD recommended achieving serum β2M levels <3.0 mg/dL [11]. However, in our study, the relationship between mortality and β2M levels was monotonic, without a clear indication of a threshold in the range of β2M from 1.4 to 4.0 mg/dL (Figure 2). Considering these findings, targeting still lower β2M levels may improve patients’ prognosis. However, the causality of this association cannot be assessed by the present observational study. Interventional studies are needed to show the threshold of β2M levels for better survival.

The results of our study corroborate the importance of middle molecules, including serum β2M accumulation as a marker for death. Thus, appropriate selection of dialyzer membrane material is important for the effective clearance of β2M and other middle molecules, with potential implications for patient prognosis. Indeed, high-flux membrane dialysis effectively removes β2M [27, 28] and is recommended by the JSDT clinical guideline for maintenance HD, the European Best Practice Guideline on dialysis strategies and the Kidney Health Australia-Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment Guideline Dialysis adequacy [11, 29, 30].

In our subgroup analyses, the mortality risk associated with elevated β2M was greater for patients with residual urine volume ≥200 versus <200 mL/day (P = 0.02 for interaction). While preserving residual kidney function is an important strategy to maintain low β2M levels, the cause of this stronger positive association of mortality with β2M among persons with residual urine volume requires further study. Perhaps not all urine volume represents the same degree of clearance, and higher levels of β2M may serve as a surrogate for impaired renal clearance of other middle and large molecules. In this regard, Evenepoel et al. [31] demonstrated that in a cohort of HD patients, 17% of total β2M clearance was due to residual urinary clearance compared with only 6% of total urea clearance, suggesting that residual kidney clearance of β2M is significant even among HD patients. The presence of a higher inflammatory burden may also play a role among patients with residual kidney function, as CRP levels are higher in patients with higher β2M levels. In another subgroup analysis, the risk of death in patients with high versus low β2M was similar in HD and HDF, indicating that the negative impact of high β2M levels on patient outcome can be observed across modalities. Further study is needed to quantify the relative contribution of β2M production versus excretion on the excess mortality risk of β2M among patients with residual kidney function.

A meta-analysis showed that convective therapies (high-flux HD, hemofiltration or HDF) are more effective than low-flux HD in reducing all-cause mortality; increasing the clearance of middle molecules (β2M); reducing the circulating levels of homocysteine, advanced glycation end products and pentosidine; and decreasing serum concentration of inflammatory biomarkers [32]. Furthermore, medium cut-off dialyzers hold the potential to positively impact β2M levels, since these novel filters remove a wide range of middle and larger molecules more effectively than high-flux HD [33]. Although a higher residual kidney function, higher dialyzer flow, higher cut-off membranes and convective therapies may reduce serum β2M level, none appears individually sufficient to normalize β2M levels in many patients. Further studies are necessary to explore whether or not enhanced removal of β2M via dialytic approaches stands to improve survival for HD patients, which could not be assessed in the present study.

The frequency of serum β2M measurements was higher in Japan than in the included European countries and much higher than in other DOPPS countries. Since the JSDT clinical guideline recommends routine measurement of serum β2M level every 3 months, it is common practice in Japan to select an appropriate dialyzer with high-flux membrane characteristics and change to other modes of dialysis therapy such as HDF in patients with high serum β2M levels [11]. The impact of the practice of using β2M levels to guide clinicians in the selection of dialyzer and dialysis modality on clinical outcomes deserves further investigation.

This work has some limitations largely related to the observational nature of this study, which cannot definitively establish a causal relationship between β2M and mortality. In this regard, unmeasured confounders may bias the results. The positive association between β2M levels and mortality may possibly reflect patient factors that lead to higher systemic inflammation or other comorbid illnesses that, in turn, result in increased generation or reduced clearance of β2M. Multiple myeloma could be a source for increased β2M production; however, this diagnosis was very rare in our sample (0.3%). β2M may also be a surrogate for other middle molecules, which may have led to the higher mortality risk that we observed. That is, outcomes may be poor among patients with elevated β2M independent of efforts to enhance dialytic β2M removal. Additionally, while we show that serum β2M level is informative, it may not be a true reflection of the total body burden of β2M. In our analysis, we also did not include patients with missing β2M data, which may have resulted in selection bias despite our attempt to address this by only including patients from facilities conducting regular β2M measurement in the majority of their patients. The data in this analysis did not indicate the types of dialyzer used or the dialyzer specifications for β2M clearance or the use of ultrapure dialysate. Thus, we were unable to evaluate the specific effects of these technological differences on β2M clearance or risk of death. In addition, when evaluating the reduction of DRA-related hospitalization rates, we must consider the fact that the surgical treatment for CTS changed from an inpatient to an outpatient procedure and that DRA-related hospitalization was self-reported by the clinic and was not validated by any histologic confirmation.

CONCLUSIONS

The current era of high-flux HD provides the technological means to support improved clearance of β2M and other middle molecules. Despite this treatment availability, some HD patients still experience higher levels of serum β2M, a status we found to be associated with increased mortality, even when controlling for potential confounders. The dialysis community needs future studies to evaluate the effectiveness of evolving dialytic strategies that target yet greater clearance of β2M and other middle or large molecules and their impact on clinical outcomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ckj online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Janet Leslie, Medical Technical Writer with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, assisted in revising the presentation of the researchers’ results and finalizing the manuscript. Jennifer McCready-Maynes, a Medical Editor with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on the manuscript.

FUNDING

Global support for the ongoing Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Programs is provided without restriction on publications by a variety of funders. For details, see https://www.dopps.org/AboutUs/Support.aspx. This manuscript was directly supported by Baxter Healthcare.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

B.B., D.M., F.K.P. and B.M.R. are employees of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which administers the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. See www.dopps.org for a list of study sponsors. F.L. reports personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Roche and personal fees from GSK, outside the submitted work. R.P.-F. reports grants from Fresenius Medical Care, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from AKEBIA and personal fees from Nono Nordisk outside the submitted work. J.P. reports consulting for Baxter Healthcare, Davita Healthcare Partners, Fresenius Medical Care and LiberDi and has received speaking honoraria from AstraZeneca, Satellite Healthcare, Davita Healthcare Partners, Fresenius Medical Care and Dialysis Clinics Incorporated. A.C. and E.K. declare that they have no relevant financial interests or other conflicts of interest concerning this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eichner T, Radford SE.. Understanding the complex mechanisms of β2-microglobulin amyloid assembly. FEBS J 2011; 278: 3868–3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scarpioni R, Ricardi M, Albertazzi V. et al. Dialysis-related amyloidosis: challenges and solutions. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2016; 9: 319–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campistol JM, Cases A, Torras A. et al. Visceral involvement of dialysis amyloidosis. Am J Nephrol 1987; 7: 390–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown PH, Kalra PA, Turney JH. et al. Serum low-molecular-weight proteins in haemodialysis patients: effect of residual renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1988; 3: 169–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inker LA, Levey AS, Coresh J.. Estimated glomerular filtration rate from a panel of filtration markers-hope for increased accuracy beyond measured glomerular filtration rate? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2018; 25: 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Argyropoulos CP, Chen SS, Ng YH. et al. Rediscovering beta-2 microglobulin as a biomarker across the spectrum of kidney diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017; 4:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheung AK, Greene T, Leypoldt JK. et al. Association between serum 2-microglobulin level and infectious mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3: 69–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liabeuf S, Lenglet A, Desjardins L. et al. Plasma beta-2 microglobulin is associated with cardiovascular disease in uremic patients. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 1297–1303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheung AK, Rocco MV, Yan G. et al. Serum beta-2 microglobulin levels predict mortality in dialysis patients: results of the HEMO study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 546–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okuno S, Ishimura E, Kohno K. et al. Serum beta2-microglobulin level is a significant predictor of mortality in maintenance haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 24: 571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Watanabe Y, Kawanishi H, Suzuki K. et al. ; “Maintenance Hemodialysis: Hemodialysis Prescriptions” Guideline Working Group, Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. Japanese society for dialysis therapy clinical guideline for “Maintenance hemodialysis: hemodialysis prescriptions”. Ther Apher Dial 2015; 19: 67–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masakane I, Sakurai K.. Current approaches to middle molecule removal: room for innovation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: iii12–iii21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Locatelli F, Mastrangelo F, Redaelli B. et al. Effects of different membranes and dialysis technologies on patient treatment tolerance and nutritional parameters. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 1293–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Domrongkitchaiporn S, Chuncharunee S, Archararit N. et al. Effect of dialyzer membranes on beta-2 microglobulin production in Thai hemodialysis patients. J Med Assoc Thai 1997; 80: S138–S143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaneko S, Yamagata K.. Hemodialysis-related amyloidosis: is it still relevant. Semin Dial 2018; 31: 612–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jadoul M, Drüeke TB.. β2 microglobulin amyloidosis: an update 30 years later. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 507–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoshino J, Masakane I, Yamagata K. et al. Significance of the decreased risk of dialysis-related amyloidosis now proven by results from Japanese nationwide surveys in 1998 and 2010. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eknoyan G, Beck GJ, Cheung AK. et al. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 2010–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheung AK, Levin NW, Greene T. et al. Effects of high-flux hemodialysis on clinical outcomes: results of the HEMO study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 3251–3263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Locatelli F, Martin-Malo A, Hannedouche T. et al. Effect of membrane permeability on survival of hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 645–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young EW, Goodkin DA, Mapes DL. et al. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): an international hemodialysis study. Kidney Int 2000; 57: S74–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pisoni RL, Gillespie BW, Dickinson DM. et al. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): design, data elements, and methodology. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 44: 7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Young EW. et al. Anemia management and outcomes from 12 countries in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 44: 94–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin DY, Wei L-J.. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc 1989; 84: 1074–1078 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Van Hoewyk J. IVEware imputation and variance estimation software. Survey Methodology Program. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2002

- 26. Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roumelioti M-E, Trietley G, Nolin TD. et al. Beta-2 microglobulin clearance in high-flux dialysis and convective dialysis modalities: a meta-analysis of published studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018; 33: 1025–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palmer SC, Rabindranath KS, Craig JC. et al. High-flux versus low-flux membranes for end-stage kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2012 (9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tattersall J, Martin-Malo A, Pedrini L. et al. EBPG guideline on dialysis strategies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: ii5–ii21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerr PG, Toussaint ND, Australia KH. et al. KHA-CARI guideline: dialysis adequacy (haemodialysis): dialysis membranes. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013; 18: 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evenepoel P, Bammens B, Verbeke K. et al. Superior dialytic clearance of β2-microglobulin and p-cresol by high-flux hemodialysis as compared to peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 2006; 70: 794–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Susantitaphong P, Siribamrungwong M, Jaber BL.. Convective therapies versus low-flux hemodialysis for chronic kidney failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013; 28: 2859–2874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirsch AH, Lyko R, Nilsson L-G. et al. Performance of hemodialysis with novel medium cut-off dialyzers. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 32: 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.