Abstract

Objectives:

To conduct a metasynthesis of eight qualitative studies of the experiences of midwives in integrated maternity practice; to identify common motifs among the eight studies through a thematic interpretive integration known as reciprocal translation; and to explore the effects on midwifery processes of care in the setting of integrated maternity practice.

Design:

A qualitative metasynthesis to analyze, synthesize, and interpret eight qualitative studies on the experiences of midwives and the effect on the midwifery processes of care in the setting of integrated maternity practice.

Sample and Setting:

Participants from the primary studies included a total of 160 midwives providing hospital-based intrapartum care. All primary studies were conducted in settings with midwives and obstetricians working together in an integrated or collaborative manner.

Findings:

Three overarching themes emerged from the data: professional dissonance, functioning from a position of risk, and practicing down.

Key conclusions:

The findings indicated that integrated maternity practice affects the professional experience of midwives. Through a qualitative exploration, a clear process of deprofessionalization and deviation from the midwifery model of care is detailed. Midwives experienced decreasing opportunity to provide the quality woman-centered physiologic care that evidence shows benefits childbearing women.

Implications for practice:

Integrated maternity practice, where low-risk and high-risk pregnancies are managed by midwife/physician teams, have proliferated as a solution to the need for quality, safe, and efficient health care. Insufficient evidence exists detailing the success or failure of this model of care. Qualitative studies suggest that the increasing medicalization occurring in integrated maternity practices minimizes the profession of midwifery and the ability to provide evidence-based quality midwifery care.

Keywords: Midwifery, Obstetrics, Delivery of health care, Integrated, Collaborative maternity care, Qualitative research

Introduction

The shift to hospital-based childbirth from home-based childbirth indelibly altered the landscape of maternity care in the twentieth century (DeVries et al., 2001). That shift brought increased institutional control over childbirth and displaced birth as a physiologic event by relocating birth in the medical domain. Now, hospital-based, integrated maternity practices, in which midwives and obstetricians work together to manage women in childbirth, have increasingly become a solution for quality, safe, and efficient health care (Angelini et al., 2012; Beasley et al., 2012; Shamian, 2014). Unfortunately, there is limited research regarding the structures, processes, and outcomes of integrated maternity care models (Downe et al., 2010; Waldman et al., 2012). Despite research showing that midwifery-led care improves care of childbearing women (Everly, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2016; McConville and Lavender, 2014; Renfrew et al., 2014) small numbers of practicing midwives limit the influence of midwifery philosophy in maternity care; in the United States, midwives participate in fewer than 10% of births, the lowest proportion of midwives to births in any industrialized nation (ACNM, 2018; AIUSA, 2010). Therefore, systematic data collection addressing the influence of integrated practice on outcomes of care, including the effect on midwifery care, is needed (Freytsis et al., 2017; Smith, 2015).

Midwifery model of care

Multiple researchers concur that the concept of normalcy is the critical characteristic of the midwifery model of care (Renfrew et al., 2014; Davis-Floyd et al., 2001), while an expectation of abnormality characterizes the predominant medicalized model of maternity care (Mackenzie Bryers and Van Teijlingen, 2010). In a review of the theoretical basis of midwifery care, Cragin and Kennedy (2006) identified consensus among midwifery theorists of three essential characteristics of the midwifery paradigm of care: (1) acknowledgment of a holistic connection between the mind and body and the environment of the childbearing woman, (2) an individualistic and woman-centered approach to care, and (3) processes of care that provide “protection and nurturance of the ‘normal’” in childbirth (p. 386). Reviews by Renfrew et al. (2014) and Kennedy et al. (2016) outline an evidence-based framework for quality maternal and newborn care and the need to “support a system-level shift from maternal and newborn care focused on identification and treatment of pathology for the minority to skilled care for all” (Renfrew et al., 2014, p. 1129). In this framework, the organization of care, philosophy of care, and the role of care providers all support optimality in care - that women are provided with specialized care and services centered around normalcy that are also congruent with their biological, psychological, social, and cultural needs. Optimality assesses for the best possible outcome, replacing “the focus on risk and adverse outcomes with a focus on measuring the frequency of ‘optimal’ (good, desired) outcomes” (Murphy and Fullerton, 2001, p. 274).

Interprofessional collaborative maternity care

Integrated practice, or interprofessional collaborative maternity care, is defined as “[a] model in which prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care is provided collaboratively by an integrated team of maternity care provider types including at least two of the following: obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine physicians, family practice physicians, midwives, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants” (Freytsis et al., 2017, p. 103). A key attribute of successful collaboration in integrated care is adoption of a shared mental model or philosophy of care (King et al., 2012; Skinner and Foureur, 2010; Smith, 2015). Prior studies suggest that the increasing medicalization occurring in integrated maternity practices minimizes the contributions midwives make (Reiger, 2008), and authors advise cautious acceptance of collaborative maternity care until this shared mental model is achieved (Downe et al., 2010; Hutchison et al., 2011; Watkins, 2015). Reaching a shared mental model of care between professionals with opposing philosophies of childbirth may prove difficult. While collaborative practices may serve the needs of high-risk childbearing women well with technology and staffing readily available for acute care, for healthy childbearing women these settings promote levels of medical intervention and risk-aversion practices that are not evidence-based and jeopardize positive maternal and infant outcomes typically seen with a midwifery-led model of care (Kennedy et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016).

Midwifery workforce

Midwives have the opportunity to fill a growing gap in the maternity workforce and improve maternity care in the United States (Thumm and Flynn, 2018). A supportive workplace climate allowing for expression of the midwifery model of care is an important component of workforce satisfaction and retention (Crowther et al., 2016; Thumm and Flynn, 2018). Can integrated maternity practices offer support for the midwifery model and provide this professional satisfaction? Extant studies indicate that integrated models may not meet these needs (Berg et al., 2012).

This mono-method qualitative metasynthesis focuses on the experiences of midwives in integrated practices and through an exploration of their own words, how the midwifery model of care and professional identity are impacted in these workplace environments. The question for this metasynthesis is: how do midwives practice a normalcy-based model of midwifery within an integrated practice setting?

Participants, ethics and methods

Metasynthesis of primary qualitative studies was guided by a senior qualitative researcher (Jones, 2015; Jones et al., 2015), informed by a social constructivist perspective and in line with established international standards (Tong et al., 2012). The design consisted of four sequential processes; (1) a systematic literature search to answer a structured research question, (2) formal quality appraisal and data immersion, (3) interpretive synthesis of the data within and across studies, and (4) re-situating the derived themes through reciprocal translation to each of the primary studies. The primary author developed the research question and completed the literature search. An integrated team approach was used for data analysis and synthesis.

Qualitative research offers the opportunity to listen to the voices of obstetric providers about their lived-experiences in integrated practice. It allows for the exploration of complex human phenomenon situated in everyday understandings through social interaction and finds its expression through language. Interpretations by researchers of participants talk in a primary qualitative study gives access to their meanings. Qualitative metasynthesis, particularly thematic synthesis as an interpretive process, expands new knowledge from existing primary qualitative research that can then build theoretical generalizability (Hoang et al., 2014; Moher et al., 2009).

Data sources and study selection

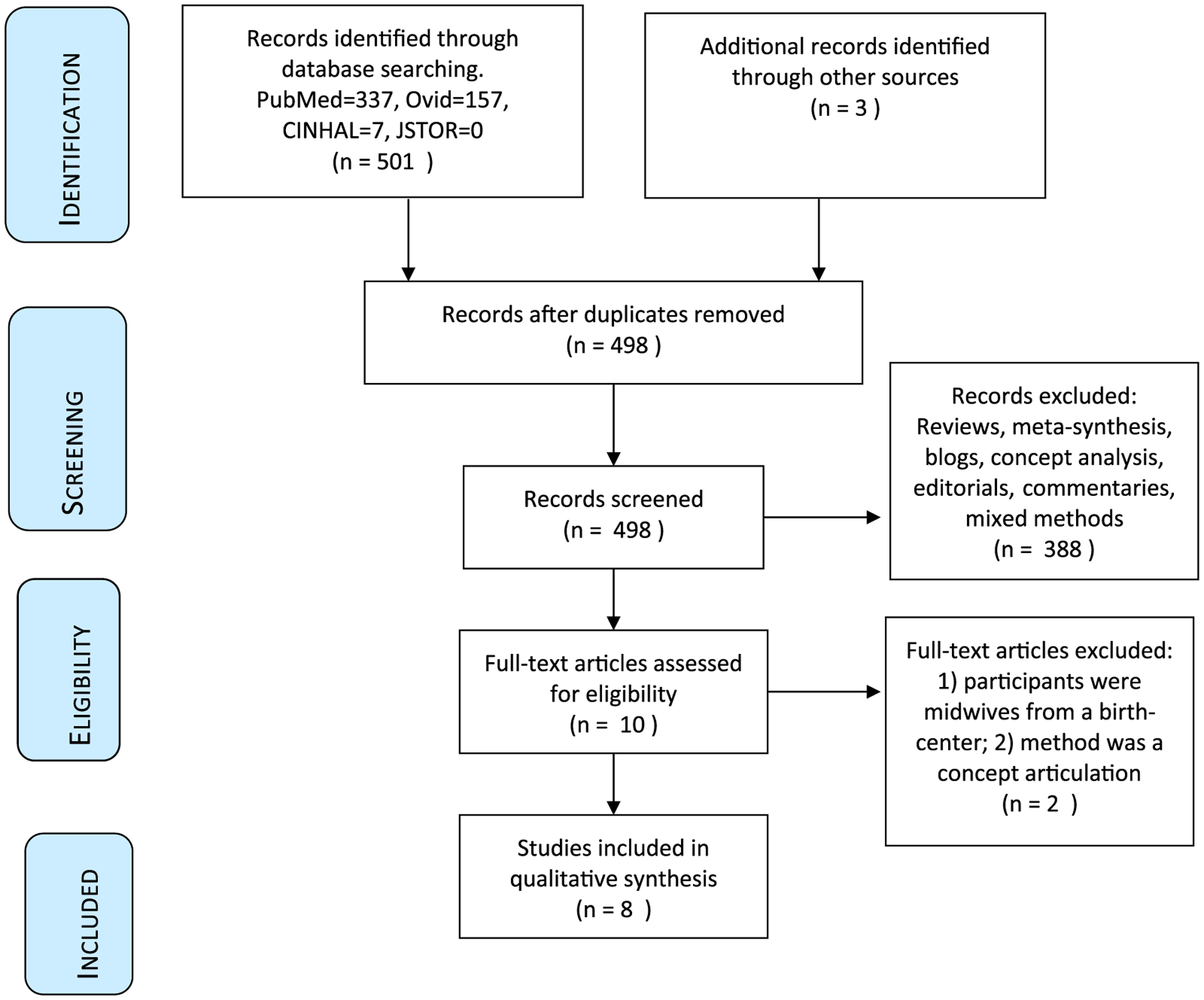

The literature search was conducted in March-April 2018. PubMed, CINHAL, JSTOR, and OVID were queried. Search terms were used that combined “midwives”, “qualitative”, “obstetrics”, and “collaborative”. Language was limited to English. In an effort to increase the yield, there was no date limit set. The search strategy is outlined in Fig. 1 in a PRISMA (Moher et al., 2009) flow diagram.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of search strategy (Moher et al., 2009).

After the removal of duplicates, literature reviews, syntheses, blogs, editorials, commentaries, quantitative studies, mixed methods studies or articles that did not include an account of midwives working in integrated practice, seven articles remained. Articles with mixed methods were excluded specifically to maintain the rich contextual interpretations gained from the participant view-point alone. Careful reading and evaluation of each article was then completed confirming the desired inclusion criteria: qualitative research, reference to the experiences of midwives, and with the majority of participants working collaboratively with obstetricians. Two more articles were excluded during this final reading, in one study all participants were birth-center based midwives with no physicians present and one study was a concept articulation. Five articles remained that suited the inclusion criteria. Returning to the previously discarded reviews and meta-syntheses, references and similar articles were hand searched and three more publications were found, for a total of eight articles included in the meta-synthesis. Studies included were conducted in Belgium, Sweden, Australia, South Wales, Ireland, England (2) and the United States. The final literature yield is presented in Table 1. The entire text of each research article constituted data for this study.

Table 1.

Included studies.

| Author | Article # | Purpose | Methodology | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catling et al.; Australia | 1 | Explore midwifery workplace culture from perspective of midwives. | Phenomenology. Semi-structured interviews. SCARF framework. Inductive analysis. |

23 midwives |

| Everly; USA | 2 | Explore factors that affect labor management decisions of midwives. | Grounded theory. Interviews. |

10 midwives |

| Hunter; South Wales, UK | 3 | Explore the emotion work of hospital-based midwives. | Ethnography. Focus groups, observations and interviews. |

44 midwives |

| Keating & Fleming; Ireland | 4 | Explore midwives’ experiences of facilitating normal birth in obstetric-led unit. | Narrative. Semi-structured interviews. |

10 midwives |

| Larrson et al.; Sweden | 5 | Explore how midwives experience their role and identity after 20 years of change. | Explorative, descriptive. Focus group interviews. |

20 midwives |

| Pollard; England | 6 | Explore how NHS midwives’ discursive practices relate to the status quo in maternity care. | Critical discourse analysis. Non-participant observation and interviews. |

Observation of large number of maternity staff. Interviews of 20 midwives. |

| Spendlove; England | 7 | Explores impact of “risk work” of maternity care on professional boundaries of OBs and midwives. | Ethnography. Participant observation and semi-structured interviews. |

37 participants: 21 midwives and 17 obstetricians |

| Van kelst et al.; Belgium | 8 | Explore midwives’ views on ideal vs actual maternity care. | Hermeneutic phenomenology. Interviews | 12 midwives. 9 hospital based. |

Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal tool designed by Letts et al. (2007) was used for formal critical analysis of the eight qualitative studies. The tool evaluates 17 domains of quality based on study design, qualitative methodology, sampling, data collection, data analysis, and credibility. Focused review of each study by all team members formed step two, data immersion. Consistent with current thematic synthesis practices, articles were not discarded based on quality criteria as each study is accepted as a novel interpretative account (Thomas and Harden, 2008; Thorne et al., 2014).

Data analysis and synthesis

Principles of metasynthesis informed by Noblit and Hare (1988); Sandelowski et al., (1997) and Thomas and Harden (2008) guided the study. The analytic process is a complex interpretive activity “peeling away the surface layers of studies to find their hearts and souls in a way that does the least damage to them” (Sandelowski et al., 1997, p. 370). A structured inductive, deductive and abductive toolkit for theme analysis was used across the whole of each article and not just on participant text to answer the research question (Goins et al., 2015; Messer et al., 2018). In step three of the process the studies were repeatedly read for thematic content within each study and then, building iteratively, for patterns of meaning and for themes of similarities and differences that enhance understanding of midwives experiences. Singular accounts were noted that help to understand and answer the study question. A comprehensive and integrated picture emerged from the combined articles drawing on interpretive insights from all team members facilitating epistemological triangulation (Creswell 2008). Further refinement of themes occurred as writing progressed and team consensus on theme language and meaning was achieved. The derived themes, supporting articles, and illustrative quotations were organized into a final reciprocal translation table presented in Table 2. Reciprocal translation enhances transparency in an analytic audit trail where each derived theme is then back tracked within and across each primary study signposting theoretical similarities and differences.

Table 2.

Reciprocal translation table (Letts et al., 2007).

| Derived Themes | Article# | Stated Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional dissonance | |||

| Facilitation | 1, 2, 3, 8 | Hierarchical thinking; Woman-centered care; The environment | “there were differences in the ease or difficulty the midwives experienced when making their decisions, depending on the people they were working with.” (#2, p. 50) |

| Maneuvering | 3,4,8 | Either/or thinking; Woman-centered care | “These tactics not only gave the appearance of compliance but were also used to provide opportunities for keeping birth normal and hence achieving ‘real’ midwifery.” (#3, p. 260) |

| Separate cultures - with woman vs with institution | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 | Bullying and resilience; Hierarchical thinking; Anxiety over uncertainty | “Bullying was seen as being linked to ‘us and them’ cultures with hierarchical structures.” (#1, p. 139) |

| Struggle to maintain ideal professional role | 1,4,5 | Hierarchical thinking; Either/or thinking; Cultural change | “Participants discussed their sense of powerlessness to change things within their workplace, and as a consequence of this, midwives felt fatigued and fatalistic about their workplace.” (#1, p. 1) |

| Disillusionment - ideal vs actual | 3,8 | Junior midwives’ responses; Support | “…despondency and disillusionment created grave doubts about their choice of career.” (#3, p. 260) |

| Passion despite the struggle to maintain ideal role | 1,4,8 | Importance of support for midwifery; Either/or thinking | “It is worthwhile to research why people choose to study for a profession of which they know they will most likely not practice it to the full.” (#8, p. e16) |

| Functioning from a position of risk | |||

| Medical model orientation/reorientation | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8 | Anxiety over uncertainty; woman-centered care; Changing professional role of the midwife | “Increasing demands for safety have affected traditional professional knowledge and experience, and modern technology has replaced many of the judgements that midwives used to make.” (#5, p. 376) |

| Decision-making process affected by fear | 1,2,5,7,8 | Anxiety over uncertainty; Trust birth | “In their views OBs emphasized risks and hereby sometimes even ‘created’ pathology.”(#8, p. e13) |

| Authoritative knowledge/hierarchy | 1,4,7 | Either/or thinking; Shifting of professional role boundaries | “This was evidenced by obstetricians themselves presenting medical knowledge and obstetric-led care as authoritative, suggesting that if midwives were able to adequately justify that medical intervention was not required, obstetricians would ‘back off.” (#7, p. 15) |

| Use of technology despite evidence | 1,3,4,5,6,7,8 | Professionalism; Shifting of professional role boundaries | “The imposition of these rules frustrated novice midwives, who considered them to be arbitrary, unscientific and illogical, in contrast to their own approach, which was described as focusing on normality, research evidence and a women-centered approach.” (#3, p. 259) |

| Practicing down | |||

| Acculturation/resocialization | 1,3,4,5,6,7 | Either/or thinking; Anxiety over uncertainty | “It was evident from observational fieldnotes that senior midwives used a ‘realistic’ discourse based on their lengthy clinical experience and expertise to justify their actions and attitudes.” (#3, p. 257) |

| Devaluation of the midwifery model | 1,3,4,5,8 | Either/or thinking; Cultural change | “Many of the midwives felt disempowered and frustrated working in a system where they were unable to utilize their midwifery skills, and they frequently felt that they were at risk of ridicule from their colleagues for not conforming to the medical model of birth.” (#4, p. 522) |

| Decreased autonomy | 1,2,3 | Bullying and resilience; The environment | “Perhaps the most clinically significant finding in the current study is the resistance midwives encounter when trying to practice midwifery care in the hospital setting.” (#2, p. 52) |

| Decreased professional identity and fidelity | 1,2,4,5,6,7,8 | Hierarchical thinking; Shifting of professional role boundaries; Professionalism | “The younger midwives were not yet anchored as experts in normal childbirth and were more dependent on written guidelines and doctor’s support that midwifery knowledge and experience.” (#5, p. 378) |

| Diminishment of midwifery over time | 1,3,4,5,7 | Hierarchical thinking, Either/or thinking; Shifting of professional role boundaries | “The midwives mentioned that handcraft is becoming less valued and is at risk of total disappearance, which will give them a poorer professional identity.” (#5, p. 377) |

Results

This synthesis of eight primary studies illustrating the experiences of 160 midwives in integrated maternity practice generated three key themes: professional dissonance, functioning through risk, and practicing down. These themes emerged through a dynamic iterative process aimed at understanding how midwives practice a normalcy-based model of midwifery within an integrated practice setting. When looked at as an aggregate, the midwives in these studies reported they were constrained in their ability to practice within a midwifery model focused on normalcy and situated within a culture that did not allow for professional expression and satisfaction. Each theme is explicated and illustrated with quotations and comments from the primary studies. Subthemes are also addressed. The studies included were published from 2005–2017.

Theme 1: professional dissonance

Dissonance is defined as a lack of agreement between the truth and what people want to believe. Professional dissonance occurs then when the reality of practice does not meet professional expectation. The primary studies presented a picture of the midwife maneuvering through conflicting demands, leading to a persistent gap between the ideal and the actual practice of midwifery, and to a state of disharmony with the professional standards of midwifery (Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Van Keltz et al., 2013). Midwives expressed that they felt the care they provided was medical care not midwifery care (Van Keltz et al., 2013). Six subthemes emerged: facilitation of normal birth, maneuvering, separate cultures (with woman vs with institution), struggle to maintain ideal professional role, disillusionment, and passion despite the struggle.

Midwives expressed the need to facilitate normal birth for the women in their care (Catling et al., 2017; Everly 2012; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Van Kelst et al., 2013).

“I do try to facilitate normal physiological birth as much as I can. I find it easier on night duty, probably ‘cause there is not so many doctors and people around so you can get into your room and be with your woman and try to do as much as you can normally” (Keating and Fleming, 2009, p. 524).

This effort meant that midwives made choices they felt were necessary to promote woman-centered care that offered an “illusion of compliance” with the prevailing workplace culture (Van Keltz et al., 2013). Methods of communication with physicians were adjusted depending on who the consultant was in order to achieve desired results (Everly, 2012).

“These tactics not only gave the appearance of compliance but were also used to provide opportunities for keeping birth normal and hence achieving ‘real’ midwifery” (Hunter, 2005, p. 260).

This maneuvering through the system was necessary to meet the conflicting demands presented by the hospital setting.

Midwives revealed this maneuvering led to a tension between separate cultures – a “with-woman” non-interventionist approach versus a more medical “with institution” approach (Hunter, 2005). Who resided on either side of this divide differed but contributed to an atmosphere of conflict that often presented in bullying behavior. While bullying was experienced with the “us and them” of typical hierarchical structures (Catling et al., 2017), some of the bullying was intercolleagueal, some was interprofessional, and some was between staff and manager (Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017). One midwife remarked on the tension between junior and senior midwives.

“…colleagues can be the biggest thing, this animosity from senior staff – the issue of bullying at work…It can crush an atmosphere, it can crush a situation, it can crush a relationship with a woman, it can crush you professionally” (Hunter, 2005, p. 256).

Another noted that with the obstetrician as final authority and a midwifery management structure that similarly ascribed to the medical model, “many of the midwives were scared of and influenced by the doctors” (Keating and Fleming, 2009). Midwives also reported organizational hierarchy and bullying.

“Given I’m a pawn in an industrial assembly line, I have very little [power]. Except when I’m in charge, slightly more…within the organization there is an almost sadistic delight being taken in oppressing initiative discouraging staff through lack of consultation and collaboration in the workplace…” (Catling et al., 2017, p. 141).

Midwives struggled to maintain their ideal professional role. They felt powerless to change the situation, leading to despondency about their workplace, their choice of career and their profession (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009).

“I think we could lose professionalization. I think we could lose the role of the midwife and that frightens me…we could become obstetric nurses and… lose our professional status. I think as a bunch of women, we’ve lost the sisterhood. We don’t support our sisters in moving the profession forward” (Spendlove, 2017, p. 13).

This discursive dissention between philosophies left midwives so disillusioned that they considered leaving their jobs (Hunter, 2005; Van Kelst et al., 2013).

“I got to a stage where I thought, ‘I hate it, I don’t want to go to work at all’- because I was so fed up – I felt I was bullied all the time to do things I didn’t want to do, it wasn’t in the woman’s best interest” (Hunter, 2005, p. 260).

The picture presented was of dissonance between the ideal of a beloved profession and the reality of the practice setting. Despite the struggle, several studies noted the passion with which midwives talked about midwifery, wondering why people would strive to enter a profession that would ultimately prove disappointing (Catling et al., 2017; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Van Kelst et al., 2013).

“I can’t explain in words how I love midwifery – my passion for the job. But I hate working where I work. I want to leave…which makes me sad” (Catling et al., 2017, p. 142).

Theme 2: functioning from a position of risk

Midwives were unanimous that labor management decisions were made based on heightened perceptions of risk rather than on the trust in normalcy essential to midwifery. There were 4 related subthemes: reorientation to the medical model, decision-making process affected by fear, authoritative knowledge/hierarchy, and use of technology despite evidence.

Though based in a desire for quality care, increasing demands for safety have resulted in loss of respect for the traditional professional knowledge and experience of midwives as technological interventions have supplanted simpler ways of knowing (Catling et al., 2017; Everly, 2102; Hunter, 2005; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017; Van Kelst et al., 2013).

“We are …more defensive practitioners, there’s more medicalization in the way we practice because we are afraid too. Any deviation from the norm, we don’t kind of think laterally any more, and think, well it could be because of this, so we’re straight in there [medicalizing care] as well because we’re afraid that if something happens, they’ll say, well you should have done this…so we change the way we practice…I look how we worked when I qualified to how we work now, normality in midwifery seems to have disappeared…It’s such a shame” (Spendlove, 2017, p. 8).

This evolution in the process of decision-making was experienced as so pronounced by midwives that they felt the obstetricians “created pathology” (Van Kelst, 2013, p. e13) which then all providers had to act upon (Catling et al., 2017; Everly, 2012; Larsson et al., 2009; Spendlove, 2017; Van Kelst, 2013). Midwives reported it was increasingly difficult for them to trust the normal process of birth in the hospital setting in which they worked.

“I found that sometimes, like when I’m worried in a hospital, having to remind myself… you can trust this process, like don’t be, don’t give in to the fear” (Everly, 2012, p. 50).

This increased risk perception, and the changes in care processes that resulted from it, underscored a hierarchical imbalance in authoritative knowledge (Catling et al., 2017; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Spendlove, 2017). Midwives experienced increased pressure by obstetricians to acquiesce by asserting their “medical knowledge and obstetric-led care as authoritative” (Spendlove, 2017, p. 15).

Midwives expressed deep frustration with the use of technology despite evidence against its use in many cases (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017; Van Kelst et al., 2013). This was especially noted by novice midwives, who expressed weariness with the “arbitrary, unscientific and illogical” imposition of rules that were in direct contrast to the evidence-based woman-centered approach in which they were trained (Hunter, 2005 p. 259).

Theme 3: practicing down

P racticing down speaks to the long-term effect of being pushed to practice outside and beneath the midwifery model while lacking effective avenue for recourse (Everly, 2012; Hunter, 2005; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017; Van Kelst et al., 2013). Midwives felt unable to function as experts in normal childbirth in the medicalized setting (Van Kelst et al., 2013, p. e16). There were 5 subthemes: Acculturation/resocialization, devaluation of the midwifery model, decreased autonomy, decreased professional identity and model fidelity, and diminishment of midwifery over time.

Midwives noted a process of acculturation to the prevailing medical culture (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017). Some noted that senior midwives justified practices that were not evidence-based by using a “realistic discourse” that their actions were based in clinical experience and expertise (Hunter, 2005, p. 257). Other studies noted a sense of resignation.

“There is a great sense of fatigue and ‘you can’t change things’ …and ‘it’s always been like this’, ‘it doesn’t matter anyways’, ‘I don’t have a voice’, ‘we tried that it didn’t work’…that’s the narrative, we just shrug our shoulders and do what we have to toe the line” (Catling et al., 2017, p. 141).

A belief that midwifery care was devalued and that midwifery skills were being disregarded was reported (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009; Van Kelst et al., 2013). Midwives made choices to conform to the medical model to avoid “ridicule from their colleagues” (Keating and Fleming, 2009, p. 522).

Midwives felt they had less autonomy to make decisions and to use their midwifery knowledge base (Catling et al., 2017; Everly, 2012).

“They wanted me to go around rupturing membranes, you know, get that birthing started, get them on Pit…that was the pressure that you felt. I tried to avoid that as much as I could. But if they…were really after me, I would do it” (Everly, 2012, p. 51).

Experienced midwives expressed a diminished sense of professional identity and fidelity to the midwifery model and a concern for the new generation of midwives because of it (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009; Pollard, 2011; Spendlove, 2017; Van Kelst et al., 2013).

“The younger midwives were not yet anchored as experts in normal childbirth and were more dependent on written guidelines and doctor’s support than midwifery knowledge and experience” (Larsson et al., 2009, p. 378).

Discussion

As detailed from the eight primary studies used in this meta-synthesis, midwives experienced a workplace culture that conflicted with their professional ability and identity. The collective synthesis of data revealed a complex process of adaptation to the demands of the environment of care. A most striking aspect of this study is the overarching sadness and dismay expressed by midwives at their inability to practice within the normalcy-based model in which they were trained.

The professional dissonance reported by midwives led to maneuvering through the system to take care of oneself and to provide woman-centered care. This “orchestration of an environment of care” (Kennedy et al., 2012) forces the modern midwife to be “a shapeshifter (she knows how to subvert the medical system while appearing to comply with it), a bridge-builder (she makes alliances with biomedicine where possible), and a networker” (Davis-Floyd et al., 2001, p. 119). The midwife voices in this metasynthesis spoke negatively of this aspect of integrated maternity practice and clearly expressed dissatisfaction with the reality of midwifery care processes in this setting.

Functioning from a position of risk has changed the landscape of maternity care. As maternity settings become more medically focused, midwives adapt their approach to mirror that of the prevailing culture (Porter et al., 2007). While the idea of defensive medicine is not a new one, this metasynthesis explained how the concept of fear and risk reduction has impacted the practice of midwifery and the resulting discontent felt by midwives. Rather than making decisions based on a belief in the midwifery model, this altered focus created doubt and “latent worries that lurk in the back of the midwife’s mind and drive her practice” (Scamell, 2011, p. 988).

Midwives who no longer practice to their potential and instead take the path of least resistance, expressed as practicing down, was worrisome. Surrounded by a medical culture that minimizes the unique contribution offered by midwifery, midwives changed their practice rather than continuing efforts to practice according to their own professional and philosophical perspective.

The three themes that emerged in this metasynthesis, professional dissonance, functioning from a position of risk and practicing down, when considered holistically, illustrate a professional evolutionary struggle that speaks to concern for the midwifery workforce but probably more importantly to the loss of a philosophy of care as embodied in the midwifery model that provides women and infants with the quality care they need. Midwives in the reviewed studies noted that the uniqueness and expertise of midwifery was not acknowledged. They reported that “midwifery handcraft was at risk of total disappearance” (Larsson et al., 2009, p. 377), and they expressed concern for the deprofessionalization of midwifery (Catling et al., 2017; Hunter, 2005; Keating and Fleming, 2009; Larsson et al., 2009; Spendlove, 2017).

“Midwifery care has been demonstrated over and over to be excellent and associated with positive maternal-infant outcomes” (Kennedy et al., 2004, p.22). Renfrew et al. (2014) illustrated clearly the many outcomes improved by care within the scope of midwifery, including decreased maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity, decreased stillbirth and preterm birth rates, decreased use of unnecessary interventions and improved psychosocial and public health while utilizing fewer resources and providing more patient-centered care. To provide for optimality in midwifery care, based on normalcy of labor and birth, midwives need to be able to practice within the model of care for which they were trained and in which they believe. Thumm (2018) notes the importance of a practice setting conducive to “the well-being of individual midwives, the midwifery workforce, and ultimately the women that midwives serve” (p. 13).

This metasynthesis looks directly at the voices of midwives and their situated experiences practicing in integrated maternity practice. The question asked here has been about the experiences of midwives as they attempt to offer normalcy-based care in integrated maternity settings, but implicit in this question is when midwives cannot practice to the height of their ability and training, they are not able to offer the advantages of the midwifery model of care and that thus, women and their families are not afforded access to the full extent of what midwifery care can provide.

There are limitations to the findings of this metasynthesis. To mitigate potential methodological limitations in the primary studies, an initial critical evaluation of each study was undertaken. Current guidelines for qualitative synthesis were rigorously applied to minimize potential shortcomings (Thorne et al., 2004; Tong et al., 2012; Sandelowski et al., 1997), providing a strengthened standard of quality for the new analysis (Kennedy et al., 2003). Only eight studies were found that fit the inclusion criteria but by combining data from all studies a relatively large sample size was achieved improving transferability of the findings. Most of the primary studies are European, which does potentially limit generalizability of the findings across countries, highlighting the need for this type of research in the United States.

Conclusion

This qualitative metasynthesis highlights the need for further exploration and understanding of the conflicting pressures on the profession of midwifery that arise from integrating midwifery care into the dominant medical culture. Quality integrated practice should provide the best of both midwifery and obstetrics. Respect for the opposing philosophies of the midwifery model and the medical model is crucial; seeing them as a continuum rather than as polarities is one step toward developing an effective collaborative relationship. Acceptance and respect for both models is needed, but we should work towards mutual admiration of each other’s abilities. With that achieved we can better manage the reality of current health care system demands for hospital-based integrated care to the advantage of midwives, physicians and patients. The concept of optimality in maternity care has been touched on here; it perhaps offers an avenue for a positive evaluation of care in integrated maternity practices, a method to consider the full range of needs of all patients that allows for both models of care to flourish for the best care of patients.

Studies should also be done that include the voices and experiences of physicians in these integrated practices. Issues of workplace satisfaction and workforce retention also apply to the collaborating providers. How do physicians experience the need to find a common mental model of care when their training has emphasized pathology and abnormality? What do their experiences tell us about the relationships between midwives and physicians in these settings? How do they experience risk and the added responsibility of collaboration with midwives? What do their experiences tell us about the health care system at large and its effect on providers of all types?

The most desired system of care should be one that provides optimal care for women and newborns. An important aspect of this system of care is to apply evidence that supports quality care, among which is the use of midwifery-led care. In integrated models, there is potential for the loss of the philosophical and professional standards of midwifery care that lead to these outcomes. To preserve the tenets of midwifery care in interprofessional collaborative models, it will be important for researchers to identify the factors and influences that contribute to the themes identified in this study.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- ACNM. 2018. Midwives: the answer to the US maternity care provider short-age. Retrieved from http://www.midwife.org/acnm/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000005828/DetailedTPsonMaternityCareWorkforce.pdf. Accessed 02/28/2019.

- AIUSA. 2010. Deadly delivery: the maternal health care crisis in the USA. From Amnesty International Secretariat Peter Benenson House.

- Angelini D, O’Brien B, Singer J, Coustan D, 2012. Midwifery and obstetrics: twenty years of collaborative academic practice. Obstetrics and Gynecologic Clinics of North America (39) 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley S, Ford N, Tracy SK, Welsh AW, 2012. Collaboration in maternity care is achievable and practical. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol 52 (6), 576–581. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Ólafsdóttir A, Lundgren I, 2012. A midwifery model of woman-centred childbirth care in Swedish and Icelandic settings. Sex. Reprod. Healthc 3 (2), 79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catling CJ, Reid F, Hunter B, 2017. Australian midwives’ experiences of their workplace culture. Women Birth 30, 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragin L, Kennedy HP, 2006. Linking obstetric and midwifery practice with optimal outcomes. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 35 (6), 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, 2008. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther S, Hunter B, McAra-Couper J, Warren L, Gilkison A, Hunter M, Kirkham M, 2016. Sustainability and resilience in midwifery: a discussion paper. Midwifery 40, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Floyd R, Pigg S, Cosminsky S, 2001. Introduction. Daughters of time: the shifting identities of contemporary midwives. Med. Anthropol 20 (2–3), 105–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries R, Benoit C, Van Teijlingen ER, Wrede S, 2001. Birth By Design: Pregnancy, Maternity Care, and Midwifery in North America and Europe. Routledge, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Downe S, Finlayson K, Fleming A, 2010. Creating a collaborative culture in maternity care. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 55 (3), 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everly MC, 2012. Facilitators and barriers of independent decisions by midwives during labor and birth. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 57 (1), 49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freytsis M, Phillippi JC, Cox KJ, Romano A, Cragin L, 2017. The American College of Nurse-Midwives clarity in collaboration project: describing midwifery care in interprofessional collaborative care models. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 62 (1), 101–108. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Jones J, Schure M, Rosenberg DE, Phelan EA, Dodson S, et al. , 2015. Older adults’ perceptions of mobility: a metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Gerontologist 55, 929–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang H, Le Q, Ogden K, 2014. Women’s maternity care needs and related service models in rural areas: a comprehensive systematic review of qualitative evidence. Women Birth 27 (4), 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter B, 2005. Emotion work and boundary maintenance in hospital-based midwifery. Midwifery 21 (3), 253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison MS, Ennis L, Shaw-Battista J, Delgado A, Myers K, Cragin L, Jackson RA, 2011. Great minds don’t think alike: collaborative maternity care at San Francisco General Hospital. Obstet. Gynecol 118 (3), 678–682. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182297d2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Nowels CT, Sudore R, Ahluwalia S, Bekelman DB, 2015. 2015. The future as a series of transitions: qualitative study of heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. J. Gen. Intern. Med 30, 176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, 2015. The contested terrain of focus groups, lived experience, and qualitative research traditions. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs 44 (5), 565–566. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating A, Fleming VE, 2009. Midwives’ experiences of facilitating normal birth in an obstetric-led unit: a feminist perspective. Midwifery 25 (5), 518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H, Rousseau A, Low L, 2003. An exploratory metasynthesis of midwifery practice in the United States. Midwifery 19 (3), 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HP, Doig E, Hackley B, Leslie MS, Tillman S, 2012. “The midwifery two-step”: a study on evidence-based midwifery practice. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 57 (5), 454–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HP, Shannon MT, Chuahorm U, Kravetz MK, 2004. The landscape of caring for women: a narrative study of midwifery practice. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 49 (1), 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HP, Yoshida S, Costello A, Declercq E, Dias MA, Duff E, Renfrew MJ, 2016. Asking different questions: research priorities to improve the quality of care for every woman, every child. Lancet Global Health 4 (11), e777–e779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King T, Laros R, Parer J, 2012. Interprofessional collaborative practice in obstetrics and midwifery. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am 39, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Aldegarmann U, Aarts C, 2009. Professional role and identity in a changing society: three paradoxes in Swedish midwives’ experiences. Midwifery 25 (4), 373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, Stewart D, Bosch J, Westmorland M, 2007. Guidelines for critical review form: qualitative studies (Version 2.0). Available at http://srs-mcmaster.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Guidelines-for-Critical-Review-Form-Qualitative-studies.pdf. Last accessed 15 September 2017.

- Mackenzie Bryers H, Van Teijlingen E, 2010. Risk, theory, social and medical models: a critical analysis of the concept of risk in maternity care. Midwifery 26 (5), 488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConville F, Lavender DT, 2014. Quality of care and midwifery services to meet the needs of women and newborns. BJOG 121 (Suppl 4), 8–10. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer LH, Johnson R, Driscoll KA, Jones J, 2018. Best friend or spy: a qualitative meta-synthesis on the impact of continuous glucose monitoring on life with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Med, 35: 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med, 151: 264–269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PA, Fullerton JT, 2001. Measuring outcomes of midwifery care: development of an instrument to assess optimality. J. Midwifery Women’s Health, 46: 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblit G, Hare R, 1988. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KC, 2011. How midwives’ discursive practices contribute to the maintenance of the status quo in English maternity care. Midwifery, 27(5): 612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S, Crozier K, Sinclair M, Kernohan G, 2007. New midwifery? A qualitative analysis of midwives’ decision-making. J. Adv. Nurs, 60: 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiger K, 2008. Domination or mutual recognition? Professional subjectivity in midwifery and obstetrics. Soc. Theory Health, 6:132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, Declercq E, 2014. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet, 384(9948): 1129–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C, 1997. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res. Nurs. Health, 20: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scamell M, 2011. The swan effect in midwifery talk and practice: a tension between normality and the language of risk. Sociol. Health Illn, 33(7): 987–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamian J, 2014. Interprofessional collaboration, the only way to save every woman and every child. Lancet, 384(9948): e41–e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Guise JM, Shah N, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Joseph KS, Levy B, Main EK, 2016. Drivers of maternity care in high-income countries: can health systems support woman-centred care? Lancet, 388(10057): 2282–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JP, Foureur M, 2010. Consultation, referral, and collaboration between midwives and obstetricians: lessons from New Zealand. J. Midwifery Womens Health, 55(1): 28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, 2015. Midwife–physician collaboration: a conceptual framework for interprofessional collaborative practice. J. Midwifery Womens Health, 60(2): 128–139. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spendlove Z, 2017. Risk and boundary work in contemporary maternity care: tensions and consequences. Health Risk Soc., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2017.1398820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Harden A, 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol, 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M, 2004. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res, 14: 1342–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Fleming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J, 2012. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ.. BMC Med. Res. Methodol, 12: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumm EB, Flynn L, 2018. The five attributes of a supportive midwifery practice climate: a review of the literature. J. Midwifery Womens Health, 63(1): 90–103. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kelst L, Spitz B, Sermeus W, Thomson AM, 2013. A hermeneutic phenomenological study of Belgian midwives: views on ideal and actual maternity care. Midwifery, 29(1): e9–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman R, Kennedy HP, Kendig S, 2012. Collaboration in maternity care: possibilities and challenges. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am, 39(3): 435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins V, 2015. Collaboration in maternity care: are we missing the point? Aust. Nurs. Midwifery J, 22(11): 51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]