Abstract

Maternal stress during pregnancy is prevailing worldwide, which exposes fetuses to intrauterine hyper glucocorticoids (GC), programming offspring to obesity and metabolic diseases. Despite the importance of brown adipose tissue (BAT) in maintaining long-term metabolic health, impacts of prenatal hyper GC on postnatal BAT thermogenesis and underlying regulations remain poorly defined. Pregnant mice were administrated with synthetic GC dexamethasone (DEX) at levels comparable to fetal GC exposure of stressed mothers. Prenatal GC exposure dose-dependently reduced BAT thermogenic activity, contributing to lower body temperature and higher mortality of neonates; such difference was abolished under thermoneutrality, underscoring BAT deficiency was the major contributor to adverse changes in postnatal thermogenesis due to excessive GC. Prenatal GC exposure highly activated Redd1 expression and reduced Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter (Ppargc1a-AP) in neonatal BAT. During brown adipocyte differentiation, ectopic Redd1 expression reduced Ppargc1a-AP expression and mitochondrial biogenesis; and the inhibitory effects of GC on mitochondrial biogenesis and Ppargc1a-AP expression were blocked by Redd1 ablation. Redd1 reduced protein kinase A phosphorylation and suppressed cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) -responsive element-binding protein (CREB) binding to the cAMP regulatory element (CRE) in Ppargc1a-AP promoter, leading to Ppargc1a-AP inactivation. In summary, excessive maternal GC exposure during pregnancy dysregulates Redd1-Ppargc1a-AP axis, which impairs fetal BAT development, hampering postnatal thermogenic adaptation and metabolic health of offspring.

Keywords: Maternal stress, Glucocorticoids, Fetus, Brown fat, REDD1, Mitochondrial biogenesis

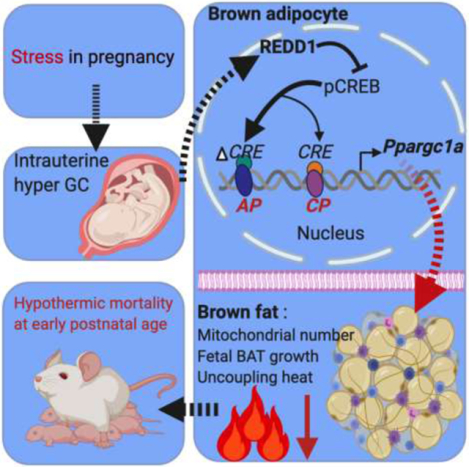

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Nearly three-quarters of women during pregnancy are reported to experience at least one stressful event, and more than half are with anxiety and depression symptoms [1–4]. The current COVID-19 pandemic evidently worsens maternal stress [5]. Maternal stress is also prevalent across other mammalian species responsive to day-to-day predation pressure, low food availability, and human disturbance in rearing environment [6, 7]. Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates stress response through secretion of stress hormone glucocorticoids (GC). During pregnancy, maternal stress increases maternal GC level in circulation and placental permeability [8], inducing fetal exposure to hyper GC in the uterus [9, 10]. Such effects presumably lead to poor birth outcome, early-life adversity, and adulthood psychological and metabolic diseases [11].

After birth, neonatal mammals must maintain their core body temperature in a narrow range, and prolonged hypothermia causes adverse neonatal outcomes and mortality, including acidosis, hypoglycemia, cardiac and respiratory injuries [12, 13]. Because neonates have higher surface area to volume ratio (heat loss), less developed shivering skeletal muscle, and poor heat insulation of subcutaneous fat and fur, neonates are susceptible to hypothermia [12, 13]. In humans, despite high-income countries are currently adopting and applying World Health Organization standards for the thermal care of newborns, the application is limited in developing countries and neonatal hypothermia is a major contributor of neonatal morbidity and mortality [12–14]. The condition is further worsened by low birth weight (more heat loss), which accounts for 60–80% of neonatal deaths [14–16]. Because maternal stress during pregnancy is robustly associated with low birth weight across mammalian species [17–21], we hypothesized that excessive GC exposure during pregnancy may impair postnatal thermogenic adaptions, increasing neonatal susceptibility to hypothermia.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) generates heat, which is critical for maintaining neonatal body temperature [22–29]. The BAT is enriched with uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1) in the inner mitochondrial membrane which converts chemical energy to heat [22–24]. Proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (Ppargc1a; protein PGC-1a) is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, which has canonical and alternative promoters [30–32]. Ppargc1a transcriptional activation promotes brown adipogenesis and UCP-1 thermogenic activity [33, 34]. In human and mouse neonates, impaired fetal BAT development and functions result in cold sensitivity and sudden death syndrome [25–29]. BAT thermogenic inactivation also contributes to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic dysfunctions in children and adults [22, 24].

BAT development initiates in the middle gestation and surges in the last trimester [22, 24, 35], thus the intrauterine environment profoundly affects prenatal BAT development and shapes postnatal thermogenic activity [36]. Up to now, the intergenerational effects of maternal GC exposure on neonatal BAT thermogenesis and postnatal viability remains unknown. In this study, we administrated pregnant mice with synthetic GC dexamethasone (DEX) at levels comparable to fetal exposure of stressed mothers during the last trimester [20, 37, 38], which corresponds to the most active stage in fetal BAT development [22, 24, 35]. We found that excessive GC exposure during pregnancy inhibits Ppargc-1a expression from the alternative promoter, which impairs brown adipogenesis, resulting in increased risks of hypothermia and mortality in neonates. Mechanistically, GC stimulates the expression of regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1 (Redd1), a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) responsive gene [39–41], which mediates GC signaling in inhibiting Ppargc-1a transcription from the alternative promoter during brown adipocyte differentiation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatments

Wildtype female C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Lab, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) at 4-month-old were mated with the same age of wildtype male mice. Mice were fed a regular diet (D12450H, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). Successful mating was assessed by the presence of a copulation plug in the vagina and marked as 0.5 embryonic days (E0.5). At E14.5, pregnant mice were randomly separated into five groups, and intraperitoneally administrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or dosed dexamethasone (DEX; D4902, Sigma, USA), including 50, 100, 300, and 500 μg/kg of body weight, until E20.5. After birth, offspring were caged with their mothers until weaning (P21) either at room temperature (22°C) or thermoneutrality (30°C). No significant difference in body mass and temperature were observed between male and female neonates. At embryonic days (E18.5) and postnatal day 1, male offspring were further euthanized by CO2, and BAT was collected for analyses. Because of the small size of neonatal BAT, male neonates from the same litter were pooled. Each dam (pregnancy) was treated as an experiment unit. All animal studies were approved by the Washington State University (WSU) Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conducted in animal facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

2.2. Isolation of mouse embryonic fibroblasts and brown adipocyte induction

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from wildtype C57BL/6J mice at E13.5. Briefly, internal organs, head, and limbs were removed following digestion in 0.025% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen, CA, USA) for 30 min in a shaking incubator at 37°C [24]. Digested tissues were filtered through 40-μm strainers. Solutions were centrifugated at 500 × g for 5 min. Precipitated cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. After growth to 80% of confluence, MEFs were induced for brown adipocyte differentiation. DMEM was supplemented with a brown adipogenic cocktail, including 0.1 μg/mL insulin, 0.5 mmol/L isobutylmethylxanthine, 1 μmol/L dexamethasone, 125 μmol/L indomethacin, and 1 μmol/L T3. Cells were refed every 48 h with a maintenance cocktail including 0.1 μg/mL insulin and 1 nmol/L T3 for additional 3 d.

2.3. Body temperature measurement

The body temperature of neonatal mice was measured with E6 infrared thermal camera (FLIR system, OR, USA) [4, 42]. After neonates were separated from nests, the temperature was obtained immediately to avoid ambient temperature effects and heat loss. During capturing images, distance and neonatal behaviors were also controlled to prevent possible artificial influences. Images were processed and analyzed by FLIR-tools-software (FLIR system).

2.4. Glucose and corticosterone measurements

In serum, glucose concentration was measured by Contour glucose monitor (Bayer, IN, USA) and corticosterone was measured by a high sensitive-corticoid kit (ADI-900, Enzo, NY, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) measurement

Intracellular cAMP concentration was measured by enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ADI-900–066; Enzo life science, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cAMP concentration was normalized to protein content measured by BCA assay (BioVision, CA, USA).

2.6. Immunohistochemistry and Oil-Red O staining

BAT was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h and embedded in paraffin as previously described [24, 42]. Tissue sections (5-μm thickness) were incubated in cold 4% PFA for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min, tissues were further incubated with primary anti-rabbit UCP-1 antibody (1:200, Cell signaling, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. After washing, tissues were incubated in secondary anti-rabbit antibody (1:1000, Alex-Fluor-555-Red; Biolegend, CA, USA) or 1 mmol/L MitoSpy-green (#424805; Biolegend) for 1 h at room temperature in dark. The background was determined by substituting the primary antibody with mouse IgG to eliminate non-specific backgrounds. Images were taken from an EVOS XL Core imaging system (Mil Creek, WA, USA). Lipids in brown adipocytes were stained by Oil-Red O [24]. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA and stained by Oil-Red O in 60% isopropanol. Images were obtained in an optical microscope. In quantification, Oil-Red O was dissolved into 100% isopropanol and absorbance value was measured in a Synergy H1 microreader (Biotek, Winooski, Vermont, USA) at 510 nm.

2.7. Transmission electron microscopy

Electron microscopic imaging was conducted as previously described [24, 42]. Briefly, fresh BAT was trimmed into tiny pieces and fixed into solution with 4% PFA (EM grade) and 3% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C. Samples were also fixed in the solution in microwave at 250 W for 2.5 min following incubation in 2% OsO4 at 4°C overnight. After dehydration, BAT was embedded in fresh resin overnight at 62°C. Concrete samples were processed for ultra-thin sectioning (60 nm) until observations of silver shadow. Sectioning samples were stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images were taken in a transmission electron microscopy (FEI Technai G2 20 Twin, 200 kV, OR, USA).

2.8. Plasmid transfection and luciferase assay

Plasmid Ppargc1a ORF (#45502), Ppargc1a wildtype promoter luciferase (#8887), delta mutation cAMP response element (CRE) luciferase (#8888), delta mutation MAD box transcriptional enhancer factor (MTEF) luciferase (#8889), and empty vector (no.13031) were purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA) as reported previously [43–45]. Plasmid Redd1 ORF (#OMu06508) was purchased from GeneScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA). CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid was purchased from GeneScript (gRNA information: Redd1 sequence, TTCGTCCTCGTCTCGAACTC). Plasmid transfection was performed using lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacture’s instruction. Luciferase activities were measured after 48 h transfection using the Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System (#E1910, Promega) according to the manufacture’s instruction.

2.9. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, NY, USA) was used to extract mRNA following instructions [24, 42, 46]. Total mRNA was reversed to cDNA by iScript™ kit (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). SYBR Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used for quantitative PCR analyses (IQ5, Bio-Rad). Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA. Primer sequences were listed in Table S1 online.

2.10. Western blot

Proteins in tissue or cells were isolated by lysis buffer as previously described [24, 42, 46]. BCA assay kit (BioVision, CA, USA) was used to quantify protein content in lysates. Protein lysates were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane were probed using primary antibody, including anti-UCP-1 (#14670, Cell Signaling), PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16; PA5–20872, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), PGC-1a (#66369-I, Proteintech, IL, USA), iodothyronine deiodinase 2 (DIO2; ab77481, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), voltage-dependent anion channels (VDAC; #4866, Cell Signaling), protein kinase A (PKA; #5842, Cell signaling), PAK at Thr197 (#4781; Cell signaling), CREB (#9197, Cell signaling), CREB at S133 (#87G3, Cell signaling), β-actin (MA5–15739, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or β-tubulin (#179513, Abcam). Secondary antibody anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IRDye was purchased from LI-COR Bioscience (Lincoln, NE, USA). Signals were detected using infrared imaging (Odyssey, LI-COR Biosciences).

2.11. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC, USA) as previously described [24, 42, 46]. Results were presented in mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired two-tail student’s t-test was applied for two-group comparisons. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in comparisons for multiple groups. For animal studies, each dam (pregnancy) was used as individual replicates. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Maternal excessive GC exposure impairs BAT development and thermogenesis, attributing to neonatal hypothermia and mortality

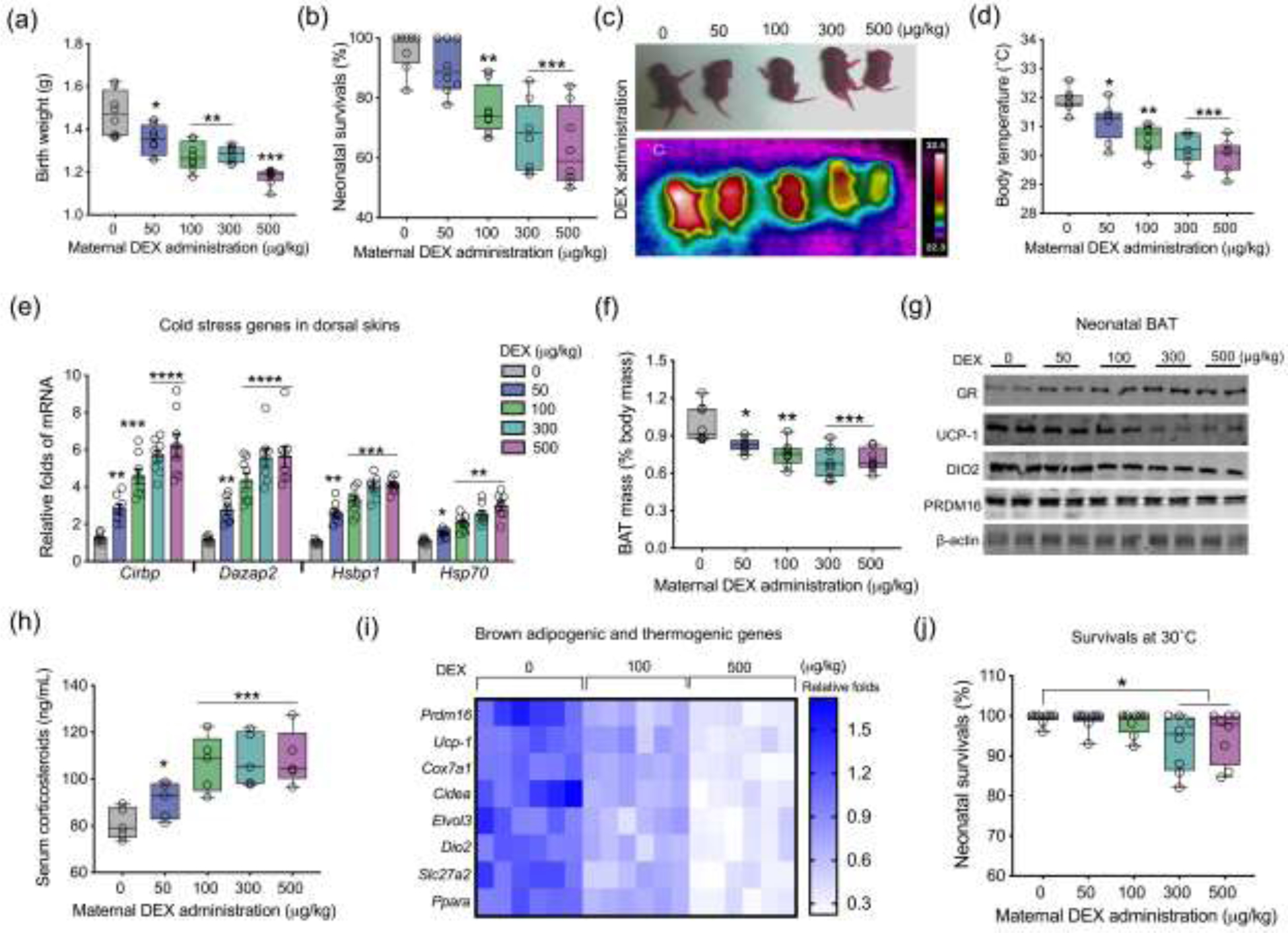

Maternal food intake, body mass, and blood glucose were not altered due to DEX administration during the third trimester (Fig. S1a–c online). Excessive GC exposure not only dose-dependently reduced neonatal body mass (Fig. 1a), but also limited survival in the first week postnatal (Fig. 1b). Neonatal survivals after the initial week were not affected by maternal DEX (Fig. S1d online). Thermal imaging showed that DEX neonates (postnatal day 1) had progressively lower body temperature as DEX dose increased (Fig. 1c and d), which were aligned with increased expression of cold stress genes in the dorsal surface skin (Fig. 1e), suggesting an increased hypothermic response. Consistently, DEX neonates had lower BAT mass (Fig. S1e‒g online), which maintained after normalized to the body weight (Fig. 1f), showing impaired fetal BAT development. GR expression was activated in BAT of DEX neonates, which was consistent with higher levels of corticosterone in neonatal serum (Fig. 1h), and correlated with reduced brown adipogenic and thermogenic protein expression, including UCP-1, DIO2, and PRDM16 (Fig. 1g, Fig. S1h online). The expression of brown adipogenic and thermogenic markers was also suppressed in DEX neonates (Fig. 1i). On the other hand, for neonates born under thermoneutrality (30°C), BAT thermogenesis was inactivated as indicated by similar expression of UCP-1 and DIO2 between control and DEX neonates (Fig. S2a online). The body temperature difference between Con and DEX neonates was abolished (Fig. S2b online), and so for the neonatal loss of DEX group in the first postnatal week (Fig. 1j), showing BAT thermogenic dysfunction due to DEX was mainly responsible for increased death of DEX neonates.

Fig. 1.

Excessive glucocorticoid exposure during pregnancy impairs brown fat development and thermogenesis, hurdling cold adaption and survivals of neonatal offspring. (a–i) Data were collected from in neonates on postnatal day 1 (P1) born from mice administrated with dosed synthetic glucocorticoids dexamethasone (DEX) in last trimester of pregnancy at room temperature (22°C) (n = 8 in each group). (a and b) Neonatal birth weight and survival percentage in the first postnatal week (n = 8 in each group). (c and d) Thermal imaging of neonates on P1 at room temperature. After neonates were removed from nests, thermal images were recorded immediately to reduce heat loss and noise effects. Scanning distance and neonatal behaviors were also controlled to avoid artificial effects (n = 8 in each group). (e) mRNA expression of cold stress genes in dorsal skins of neonates on P1. Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 8 in each group). (f) BAT mass (% body mass) of neonates on P1 (n = 8 in each group). (g) Immunoblotting measurements of GR, PRDM16, UCP-1, and DIO2 protein contents in neonatal BAT. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 8 in each group). (h) Concentration of corticosteroids in neonatal serum on P1 (n = 5 in each group). (i) Heatmap of gene expressions in brown adipogenesis and thermogenesis. mRNA expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 6 in each group). (j) Neonatal survivals in the postnatal week under thermoneutrality at 30°C (n = 8 in each group). Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate (each pregnancy); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; unpaired one-way ANOVA multiple test was used in analyses.

3.2. Maternal excessive GC exposure impairs Ppargc1a alternative transcription and mitochondrial biogenesis

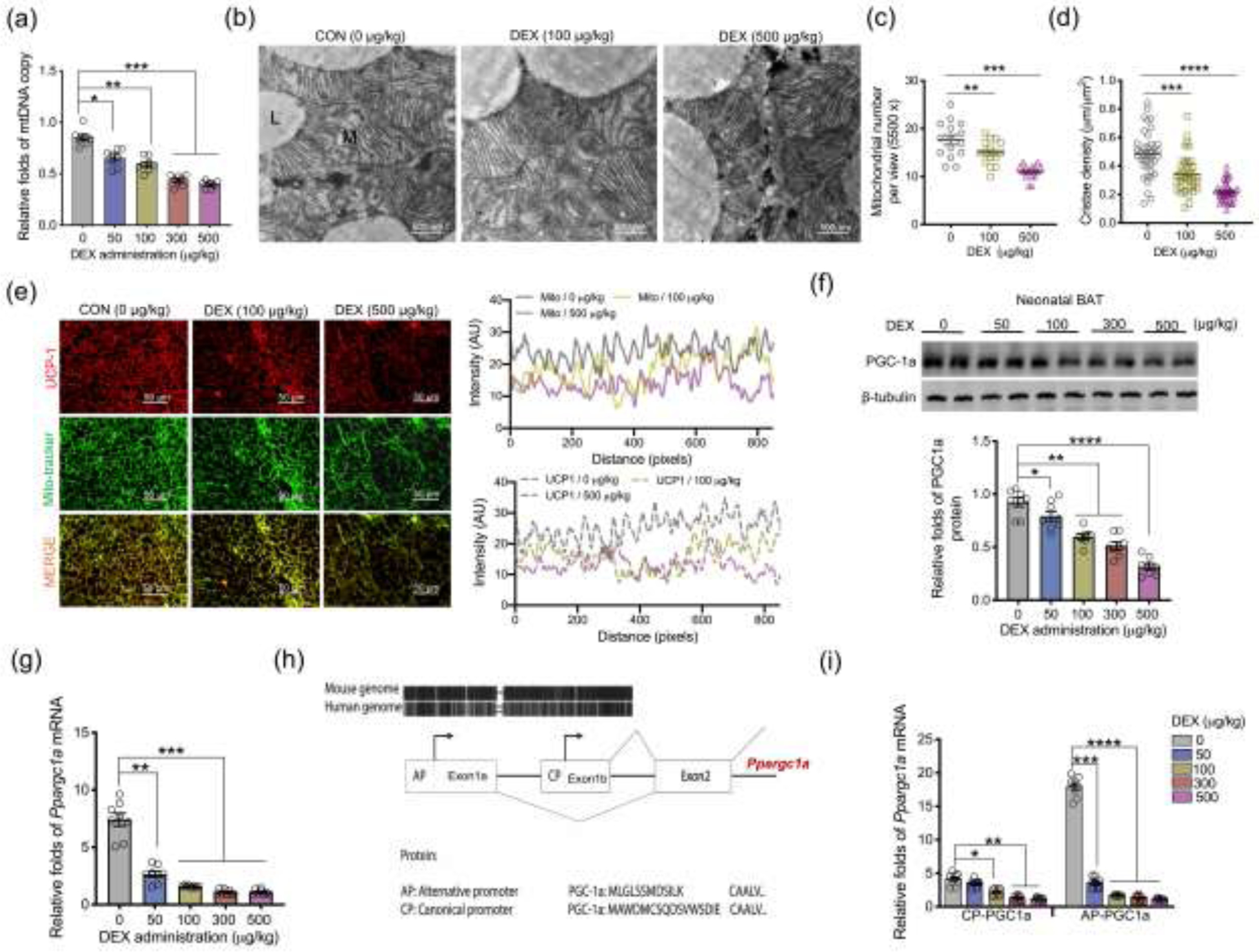

Mitochondrial biogenesis is central for BAT development [33, 34]. Maternal GC exposure reduced mtDNA content, mitochondrial number, and cristae density in neonatal BAT (Fig. 2a–d), showing impaired mitochondrial biogenesis. Reduced mitochondrial density aligned with UCP-1 inactivation in DEX neonates (Fig. 2e) [30–32]. Being a master regulator in mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC-1a protein content was dose-dependently reduced in BAT of DEX neonates (Fig. 2f and g). Ppargc1a, encoding PGC-1a protein, is transcribed from two distinct promoters, canonical and alternative promoters (Fig. 2h). Maternal GC exposure marginally reduced Ppargc1a transcription from the canonical promoter, but transcription from the alternative promoter was reduced by 13 folds in neonatal BAT (Fig. 2i), showing a preferential suppression of alternative promoter activity due to DEX. Consistently, maternal GC exposure (100 μg/kg) activated GR expression (Fig. S3a online), contributing to significant decreases of PGC-1a protein content and mitochondrial biomass markers VDAC and mito-tracker in fetal BAT at E18.5 (Fig. S3a and b online). Meanwhile, Ppargc1a was predominantly transcribed from the alternative promoter (Fig. S3c online), which was also highly suppressed in fetal BAT due to GC exposure (Fig. S3d online).

Fig. 2.

Excessive glucocorticoid exposures during pregnancy inhibit mitochondrial biogenesis and Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter in BAT of neonatal offspring. (a–j) BAT was collected and analyzed in neonates on postnatal day 1 (P1) born from maternal mice exposed synthetic glucocorticoids, dexamethasone (DEX), in the last trimester of pregnancy. (a) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number in neonatal BAT (n = 8 in each group). (b–d) Transmission electron microscopy analyzing mitochondrial number and cristae density in neonatal BAT (n = 4 in each group). “L” represents lipid droplet, and “M” represents mitochondria. Scale bar = 500 nm. (e) Immunostaining measurements of UCP-1 (red) and mitochondria (mito-tracker, green) in neonatal BAT. Intensity of UCP-1 and mito-tracker were quantified by Image-J (n = 4 in each group). Scale bar: 50 μm. (f) Immunoblotting measurement of PGC-1a protein content in neonatal BAT. β-tubulin was used as a loading control (n = 8 in each group). (g) mRNA expression of Ppargc1a in neonatal BAT. Expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 8 in each group). (h) Diagram shows the canonical promoter (CP) and alternative promoter (AP) of Ppargc1a are highly conserved between human and mice. Except for transcriptional difference in the first exon, transcription and encoded amino acids from other exons are the same between Ppargc1a CP and AP. (i) Ppargc1a mRNA expression transcribed from CP and AP in BAT of neonates born to DEX mothers. mRNA expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 8 in each group). Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate (each pregnancy); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; unpaired one-way ANOVA multiple test was used in analyses.

3.3. Ppargc1a alternative promoter inactivation accounts GC suppressive effects on brown adipogenesis

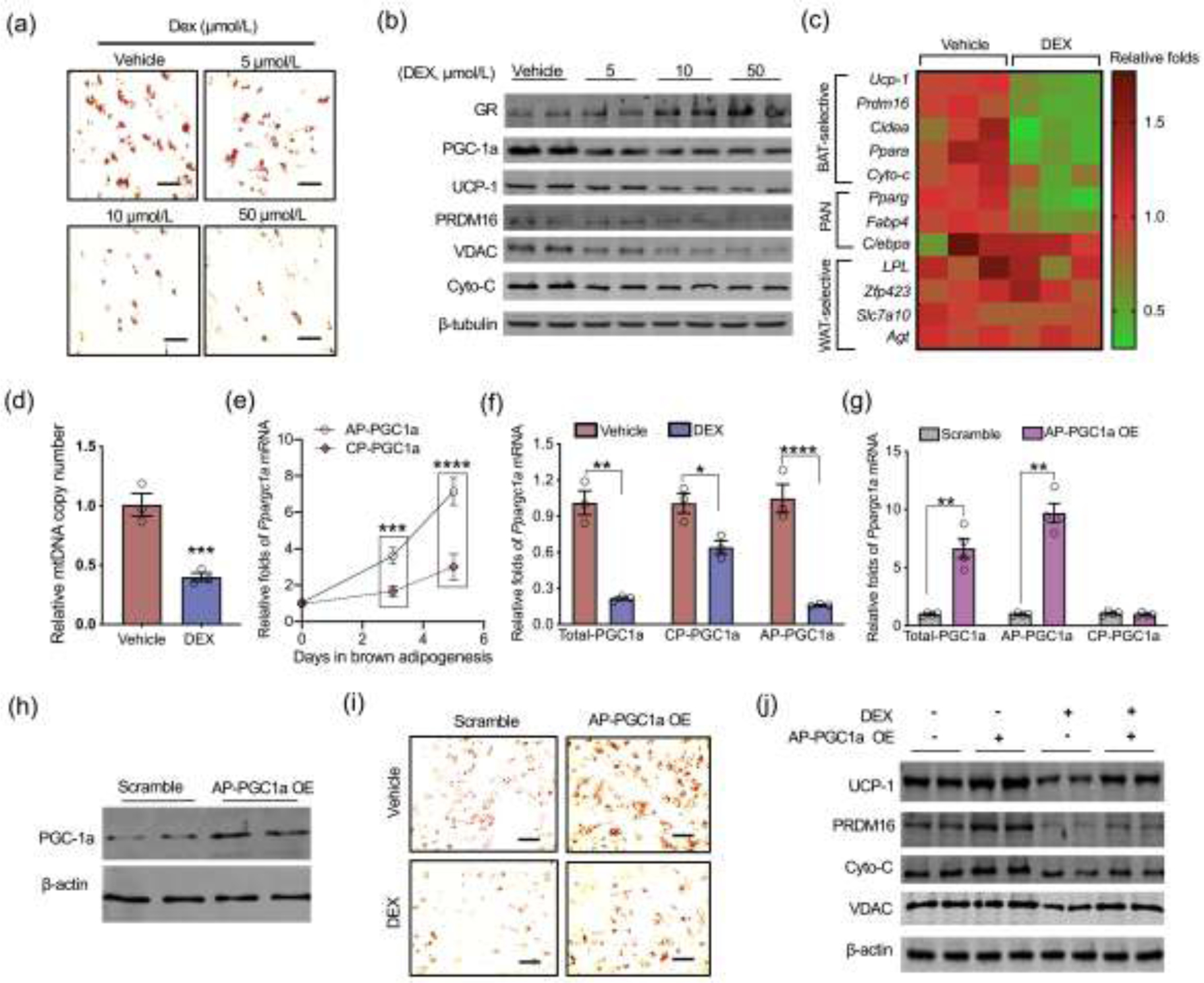

To define mechanisms leading to Ppargc1a suppression, we isolated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and induced brown adipogenesis. GC supplementation activated GR expression and hampered brown adipocyte differentiation in a dose-dependent manner, including reduced density of mature brown adipocytes and the expression of adipogenic and thermogenic proteins and genes (Fig. 3a–c). GR was expressed in early brown adipogenic differentiation towards full maturation, which was ectopically increased by GC addition (Fig. S4a online). In accordance with reduced PGC-1a protein (Fig. 3b), mtDNA and mitochondrial biomass markers, VDAC and cytochrome C, were also decreased (Fig. 3b and d), showing impaired mitochondrial biogenesis. During brown adipogenesis, Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter was highly activated relative to the canonical promoter (Fig. 3e), which was profoundly suppressed by GC (Fig. 3f). Similar effects were also observed during brown adipogenic differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells (Fig. S3b and c online). To test the effects of Ppargc1a-alternative promoter suppression due to GC in blocking brown adipocyte differentiation, we overexpressed Ppargc1a transcripts from the alternative promoter in MEFs following brown adipogenic induction (Fig. 3g and h). Ppargc1a overexpression from the alternative promoter promoted brown adipocyte differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis, which significantly reversed GC inhibitory effects (Fig. 3i and j). These data showed that the alternative promoter inactivation mainly accounts for GC suppressive effects on fetal brown adipogenesis and thermogenic activation.

Fig. 3.

Dexamethasone (DEX) inhibits transcription of Ppargc1a alternative promoter during brown adipocyte differentiation. (a–f) Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from wildtype C57BL/6J mice and induced for brown adipocyte differentiation. In brown adipogenic induction, MEFs were treated with DEX (n = 4). (a) Oil-Red O staining in differentiated mature brown adipocytes at 5 days (n = 4). Scale bar: 50 μm. (b) Immunoblotting measurement of adipogenic and thermogenic proteins in differentiated brown adipocytes, including GR, PGC-1a, UCP-1, PRDM16, VDAC, and cytochrome c (Cyto-C). β-tubulin was used as a loading control (n = 4). (c) Heatmap displaying brown adipogenic and thermogenic gene expression in differentiated brown adipocytes (vehicle vs. 10 μmol/L DEX). The mRNA expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 3). PAN: gene expressions which are shared in brown and white adipocytes, WAT: white adipose tissue. (d) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number in differentiated brown adipocytes (vehicle vs. 10 μmol/L DEX). Mitochondrial gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA and GAPDH (n = 4). (e) Ppargc1a mRNA expression transcribed from the canonical promoter (CP) and alternative promoter (AP) during brown adipocyte differentiation (n = 4). (f) Ppargc1a transcriptions from AP and CP in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with vehicle or 10 μmol/L DEX. Expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). (g–j) MEFs were transfected with plasmids with scrambled or open reading frame of Ppargc1a transcribed from the AP for over-expression (OE) (AP-PGC1a OE) followed with brown adipogenic induction. (g) Ppargc1a transcription from AP and CP in MEFs transfected with scrambled or AP-PGC1a plasmids. Expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). (h) Immunoblotting measurement of PGC-1a total protein content in MEFs transfected with scrambled or AP-PGC1a plasmids. β-actin was used as a loading control. (i and j) MEFs transfected with scrambled and AP-PGC1a OE plasmids were also treated with vehicle or 10 μmol/L DEX in brown adipocyte differentiation (n = 4). On day 5, differentiated brown adipocytes were stained by Oil-Red O (scale bar: 50 μm) (i), and contents of brown thermogenic and mitochondrial biomass proteins were measured using immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4). Data are representative of three separate experiments. Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; unpaired Student’s t-test with two-tailed distribution was used in panel (c–g) data analyses.

3.4. REDD1 mediates GC inhibitory effects on Ppargc1a transcription from alternative promoter

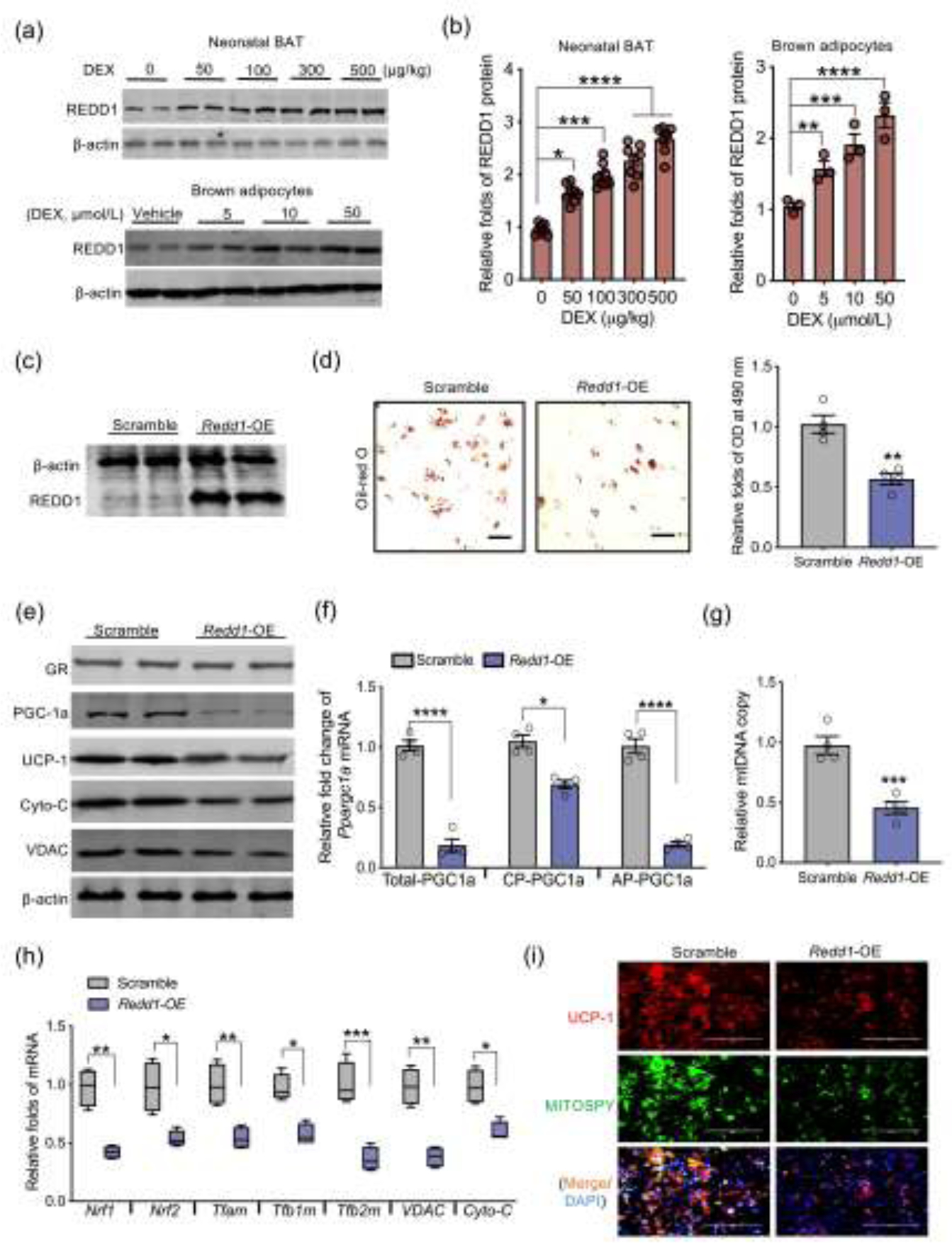

Redd1, a major GR responsive gene, has been reported to play a major role in mediating GC induced muscle atrophy [47, 48]. Reed1 was highly activated in BAT of DEX neonates and fetuses (Fig. 4a and b, Fig. S3a online), and similar activation was also observed in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with GC (Fig. 4a and b). To analyze the mediatory roles of REDD1 in linking DEX to impaired fetal brown adipogenesis, we overexpressed Redd1 in MEFs following brown adipogenic induction (Fig. 4c). Redd1 overexpression substantially reduced brown adipogenic differentiation (Fig. 4d and e). Exotic Redd1 expression inactivated Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter (Fig. 4f). Consistently, expression of downstream mitochondrial biogenic genes, mtDNA content, and mitochondrial density were decreased in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with DEX (Fig. 4g–i).

Fig. 4.

REDD1 activation inhibits brown adipogenesis and Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter. (a and b) Immunoblotting measurement of REDD1 protein content in BAT of neonates born to dexamethasone (DEX) treated mothers during the last trimester of pregnancy (n = 8). REDD1 protein shown in the bottom of Western blot figure was measured from brown adipocytes differentiated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) treated with dosed DEX (n = 4). β-actin was used as a loading control. (c–i) MEFs were transfected with scrambled or open reading frame of Redd1 plasmids for over-expression (Redd1-OE) following brown adipocyte differentiation (n = 4). (c) Immunoblotting measurement of REDD1 in MEFs transfected with Redd1-OE. β-actin was used as a loading control. (d) After brown adipocyte differentiation, lipid droplets were stained by Oil-Red O and quantified at 490 nm (n = 4). Scale bar: 50 μm. (e) Immunoblotting measurements of thermogenic and mitochondrial biomass proteins in differentiated brown adipocytes. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4). (f) Ppargc1a transcription from the canonical promoter (CP) and alternative promoter (AP) in differentiated brown adipocytes transfected scrambled or Redd1-OE plasmid. Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). (g) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content in differentiated brown adipocytes. Mitochondrial gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA and GAPDH (n = 4). (h) mRNA expression of mitochondrial biogenic genes. Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). (i) Immunostaining of UCP-1 (red color), mitochondria (MITOSPY, green color) and nucleus (DAPI, blue color) in differentiated brown adipocytes (n = 4). Scale bar: 50 μm. Data are representative of three separate experiments. Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; unpaired Student’s t-test with two-tailed distribution was used in two treatment data analyses.

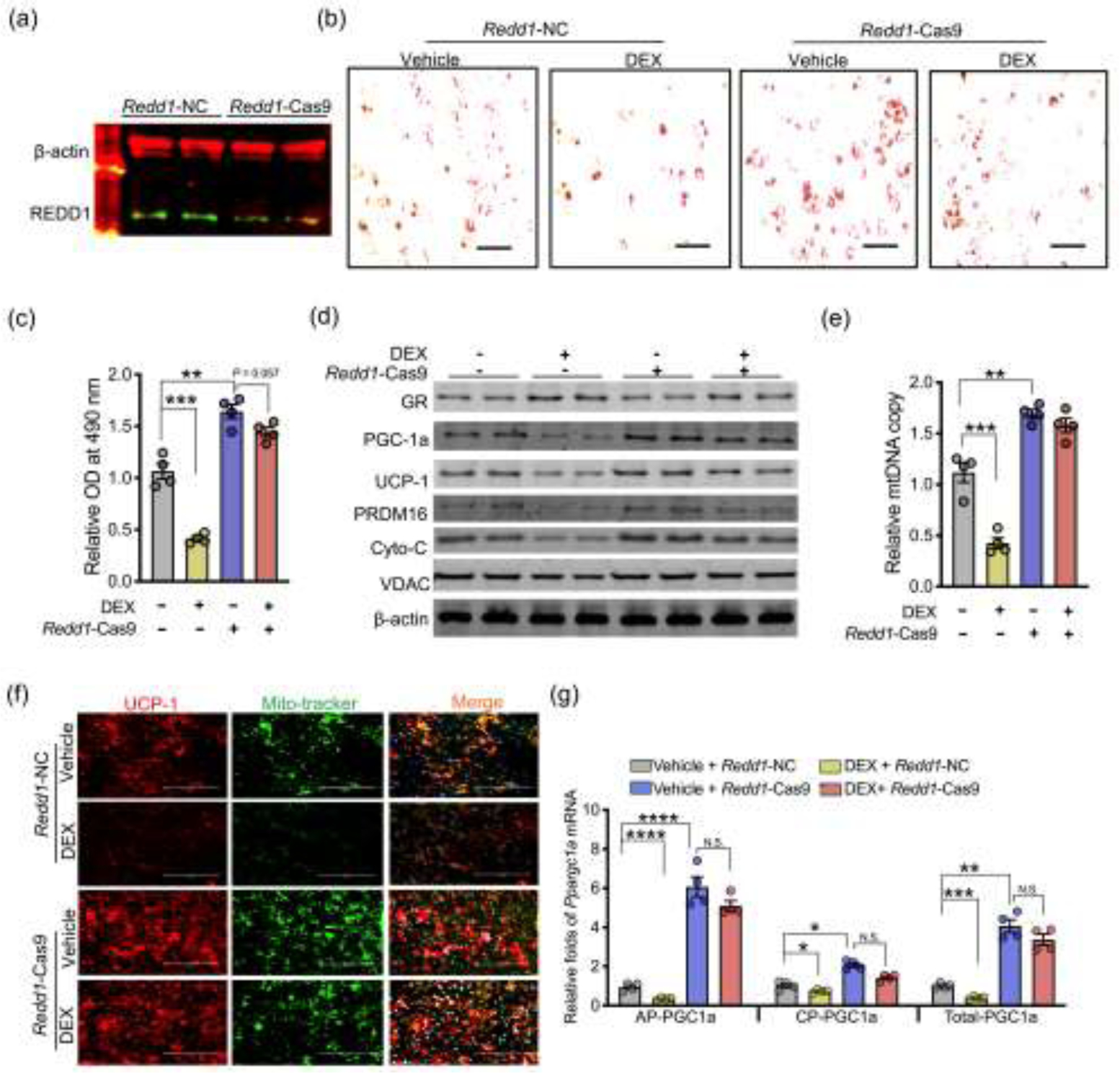

In addition, CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA was performed to knockdown Redd1 expression in MEFs (Fig. 5a). Redd1 knockdown promoted brown adipocyte differentiation, including increased differentiation of brown adipocytes, contents of adipogenic and thermogenic proteins, and the mitochondrial density (Fig. 5b–f). Meanwhile, Redd1 ablation blocked the inhibitory effects of GC on brown adipogenic differentiation and mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 5b–f). Of importance, Redd1 knockdown also rescued Ppargc1a expression from both alternative and canonical promoters, which were inhibited by GC (Fig. 5g). In combination, these data showed that Redd1 mediates GC inhibitory effects on Ppargc1a activity.

Fig. 5.

REDD1 mediates inhibition of brown adipocyte differentiation and Ppargc-1a transcriptions from the alternative promoter due to dexamethasone (DEX) treatment. (a–d) Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were transfected with negative control (Redd1-NC) or CRSPIR-Cas9 gRNA targeting Redd1 (Redd1-Cas9). After transfection, MEFs were treated with vehicle or 10 μmol/L DEX in brown adipocyte differentiation (n = 4). (a) Immunoblotting measurement of REDD1 content in MEFs transfected with Redd1 Cas9 gRNA. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4). (b and c) Lipids were stained by Oil-Red O and further quantified at 490 nm (n = 4). Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Immunoblotting measurements of thermogenic and mitochondrial biomass protein contents in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with vehicle or DEX. β-actin was used as a loading control (n = 4). (e) Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content in differentiated brown adipocytes. Mitochondrial genes were normalized to 18S rRNA and GAPDH (n = 4). (f) Immunostaining of UCP-1 (red color), mitochondria (mito-tracker, green), and nucleus (DAPI, blue) in differentiated brown adipocytes (n = 4). Scale bar: 200 μm. (g) Ppargc-1a transcription from the alternative (AP) and canonical promoters (CP) in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with vehicle or DEX. Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). Data are representative of three separate experiments. Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; Unpaired one-way ANOVA multiple test was used for data analyses.

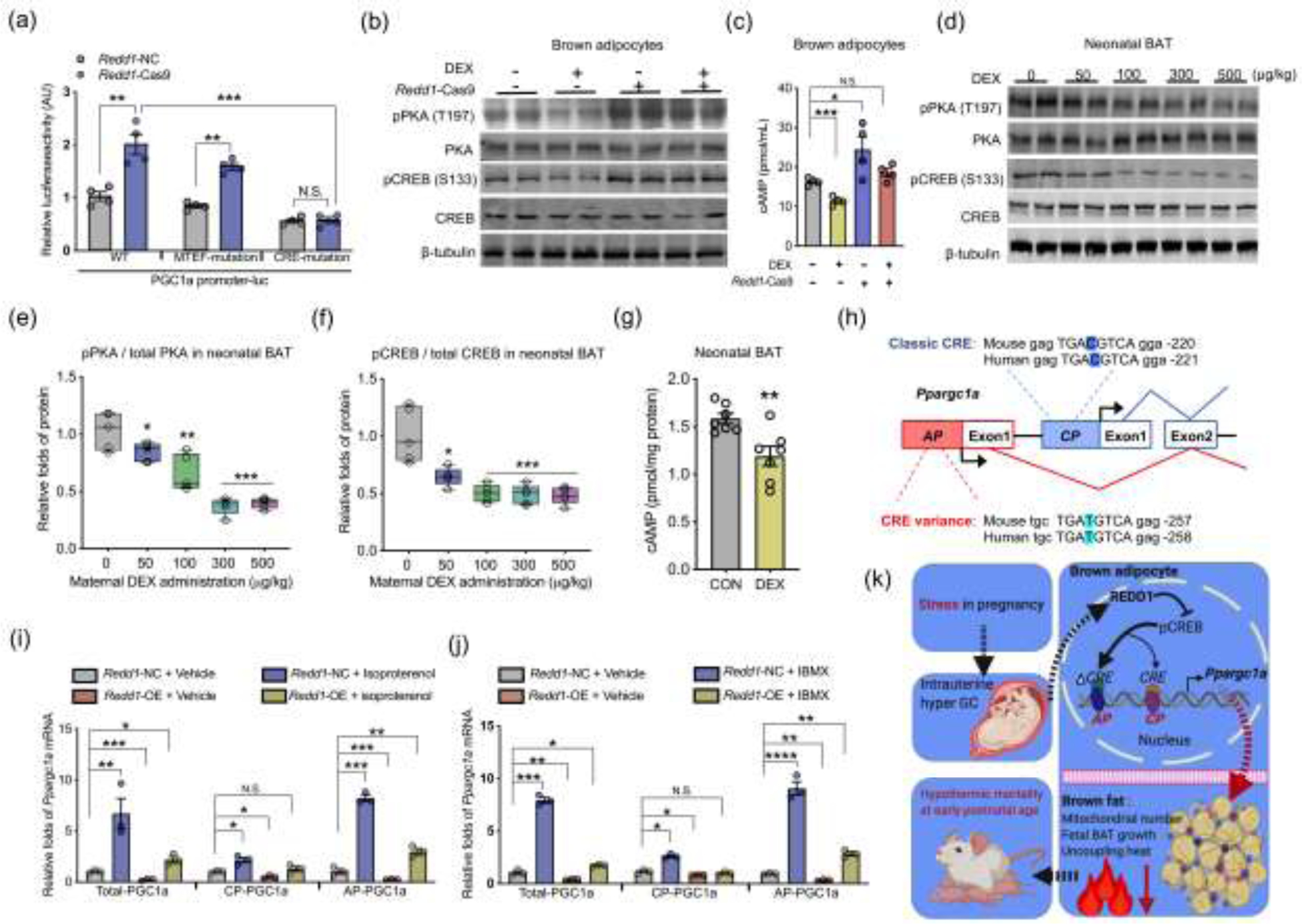

3.5. REDD1 inhibits PKA phosphorylation to suppress Ppargc1a alternative promoter activity

To identify potential pathways linking REDD1 to Ppargc1a transcription, we searched for conserved cis-element in the first 2 kb of Ppargc1a alternative and canonical promoters responsive to stress signaling. A CRE and a MAD box transcriptional enhancer factor (MTEF) binding element are conserved in alternative and canonical promoters. To test their regulatory roles, luciferase reporters were constructed for the Ppargc1a wild-type promoter, and promoters with CRE and MTEF binding elements mutated, the reporters were further transfected into MEFs. During brown adipogenesis, Redd1 knockdown increased the wild-type promoter activity; this activation was not affected in MEFs transfected with the promoter carrying MTEF mutation but was blocked when carrying CRE mutation (Fig. 6a), suggesting that CRE cis-element was responsible for Redd1 suppression. Furthermore, GC supplementation inhibited phosphorylation of PKA at Thr197 (Fig. 6b), which was aligned with reduced cAMP production (Fig. 6c), leading to cAMP responsive element-binding protein (CREB) activity suppression in differentiated brown adipocytes (Fig. 6b); these changes were abolished by Redd1 knockdown (Fig. 6b and c). Consistently, reduced cAMP production and PKA phosphorylation were observed in BAT of DEX neonates, suppressing CREB activation (Fig. 6d–g). Comparing human and mouse sequences, the conserved CRE cis-element in the Ppargc1a alternative promoter has one nucleotide variance, while the classical CREB cis-element is identical (Fig. 6h). MEFs were also treated with cAMP agonists isobutylmethylxanthine and isoproterenol during brown adipocyte differentiation [49, 50]. Both agonists profoundly activated Ppargc1a transcriptions from both canonical and alternative promoters, but the alternative promoter had higher transcriptional activation (Fig. 6i and j). Supplementation of cAMP agonists also rescued Ppargc1a expression inhibited by Redd1 overexpression (Fig. 6i and j), suggesting the mediatory roles of CREB cis-element in suppressing Ppargc1a transcription by REDD1. Taken together, our data show that intrauterine excessive GC exposure impairs BAT development and thermogenesis, hampering neonatal thermogenesis and cold adaption. Redd1 plays a critical role in mediating GC inhibition on Ppargc1a transcription, particularly from the alternative promoter, impairing mitochondrial biogenesis and brown adipocyte differentiation (Fig. 6k).

Fig. 6.

REDD1 inhibits cAMP production to inactivate Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter during brown adipocyte differentiation. (a) Luciferase reporter activities of wildtype Ppargc1a (WT) promoter, or promoters with mutated MAD box transcriptional enhancer factor (MTEF) or mutated cAMP response binding (CRE) was measured in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) transfected with Redd1 Cas9 gRNA (Redd1-Cas9) or negative control (Redd1-NC), n = 4. (b) Immunoblotting measurements of PKA, phosphorylated PKA at Thr197, CREB, and phosphorylated CREB at S133 in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with dexamethasone (DEX); β-tubulin was used as a loading control. (c) cAMP concentration in differentiated brown adipocytes transfected with Redd1 Cas9 gRNA (Redd1-Cas9) or scrambled gRNA (n = 4). (d–f) Immunoblotting measurements of PKA, CREB, and phosphorylation in neonatal BAT born from maternal mice treated with DEX administration in the last trimester of pregnancy; β-tubulin was used as a loading control. The ratio of phosphorylated protein to total protein was quantified in neonatal BAT (n = 5). (g) cAMP concentration in fresh BAT of neonates born from maternal mice treated with PBS and DEX (100 μmol/L) in the last trimester of gestation. cAMP concentration was normalized to protein content. (h) Diagram shows cAMP response binding element (CRE) in the canonical (CP) and alternative promoters (AP) of Ppargc1a. CRE in the Ppargc1a alternative promoter has a thymine nucleotide variance (T, highlighted in red color) relative to cytosine (C) in classical CRE of the canonical promoter. (i and j) Ppargc1a transcription from canonical promoter (CP) and alternative promoter (AP) in differentiated brown adipocytes treated with cAMP agonists isoproterenol (100 μmmol/L) (i) or isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX, 5 mmol/L) (j). Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA (n = 4). (k) Diagram models that intrauterine excessive glucocorticoid exposure from maternal stress during pregnancy impairs brown fat development and thermogenesis, impairing neonatal cold adaption and viability. REDD1 mediates glucocorticoid inhibition of Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter during brown adipocyte differentiation. Data are representative of three separate experiments. Data are mean ± SEM and each dot represents one replicate; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; Unpaired Student’s t-test with two-tailed distribution was used in two treatment data analyses; unpaired one-way ANOVA multiple test was used for four treatment data analyses.

4. Discussion

Adverse environmental exposure during pregnancy causes poor fetal development, programming poor neonatal outcome and predisposing to later onset diseases [11]. Nearly 8–16% of women at reproductive age are suffering depression in the US [51, 52], and the number is even worse in developing countries [1, 3]. To be a key mediator of maternal stress, GC level is substantially increased in the uterus [6, 53, 54], perturbing fetal tissue and organ development. Low birth weight and prematurity are highly associated with intrauterine excessive GC exposure in both humans and other mammals [17, 21, 55, 56], constituting major causes of neonatal mortality and morbidity [15, 16]. Our data revealed that intrauterine excessive GC exposure impaired BAT development and thermogenesis, leading to neonatal hypothermia and mortality. We further found that GC suppressed Ppargc1a transcription, particularly from the alternative promoter. Meanwhile, Redd1 was found to bridge GC signaling to inactivate Ppargc1a alternative promoter, resulting in impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and brown adipogenesis.

Homeothermic mammals must maintain body temperatures, particularly at “altricial” age, and hypothermia can cause severe infections, sepsis, and asphyxia, leading to mortality and morbidity [12, 13]. Due to the evaporation of amniotic fluid, higher surface area to volume ratio and lack of shivering heat generation and surface insulation [12, 13], physiological adaption from intrauterine thermoneutrality (30–32°C in mice) to extrauterine cold is a major challenge for postnatal survival [23]. Despite cloth covering and warm temperature prevent hypothermia of human neonates, appropriate protocols for baby birth care is often limited for homebirth and undeveloped areas, contributing to common hypothermia-induced neonatal mortality [12–14]. To be an essential organ for heat generation, neonates are packed with abundant BAT to prevent hypothermia. In this study, we administrated maternal mice with synthetic GC in the late gestation, mimicking maternal stress-induced intrauterine hyper GC conditions [20, 37, 38]. The highest DEX usage (500 μg/kg) was at least two-fold lower than the doses used for anti-inflammatory therapy and adrenal tumor studies including Cushing’s syndrome [57]. Such low doses and short-term administration may explain the lack of significant difference in food intake and body weight in maternal mice. After maternal mice were exposed to excessive GC, neonatal BAT mass and thermogenic activity were significantly reduced, contributing to increased cold sensitivity and mortality at room temperature. In order to test mediatory roles of BAT thermogenesis in neonatal viability, neonates were also born under thermoneutrality to inactivate BAT thermogenesis and prevent hypothermia. Aligned with body temperature improvement, neonatal viability was recovered, showing BAT thermogenic dysfunction attributing to neonatal mortality. In this study, DEX neonates also displayed higher levels of corticosteroids in circulation, suggesting a programmed hypothalamus stress-axis and vulnerability to postnatal stress [58–60]. Mouse neonates are born naked, blind with no moving capability, but they gain protective coat of fur and stronger skeletal muscle (shivering and nest wandering) after 7 to 10 d of age, which compensates for heat loss, partially explaining the lack of difference in mortality after the first postnatal week.

Ppargc1a is a master regulator in mitochondrial biogenesis, driving brown adipogenic and thermogenic functions [33, 34]. Recent studies reveal that Ppargc1a is transcribed from both canonical and alternative promoters in skeletal muscle and BAT [30–32]. Notably, the Ppargc-1a transcription from canonical and alternative promoters vary due to physiological stimuli, including exercise and cold [32, 61, 62]. Ppargc-1a transcription from alternative and canonical promoters was similar in resting skeletal muscle [45], but the transcription from alternative promoter is more activated relative to the canonical promoter under exercise [32]. Similarly, Ppargc-1a transcription from the alternative promoter is predominantly activated in BAT under cold exposure [62]. In this study, Ppargc-1a transcription from canonical and alternative promoters was similar in adult BAT, but the alternative promoter was dominantly increased in fetuses and neonates. The preferable activation from the alternative promoter was also observed during brown adipogenic differentiation, indicating the alterative promoter had a higher sensitivity to adipogenic stimuli [62]. Phosphorylated CREB binds to CRE of Ppargc1a promoters and increases Ppargc1a transcription [63]. Despite both alternative and canonical promoters containing CRE, the CRE site TGATGTCA in the Ppargc1a alternative promoter has a single nucleotide variance (C-T) relative to typical CRE site TGACGTCA [64], potentially contributing to an increased Ppargc1a transcriptional activation due to cold exposure and exercise [32, 62]. In this study, the alternative promoter was shown to be highly activated by cAMP agonists relative to the canonical promoter, suggesting the CRE variance (C-T) in alternative promoter may attribute to the high sensitivity to the CREB activation. Because of accumulation of cAMP and PKA activation in skeletal muscle under exercise [65], CREB activation may also attribute to the marked increase of Ppargc1a transcription from the alternative promoter due to exercise [66, 67].

Redd1 is a key GR responsive gene and highly activated by a variety of stressors, including hypoxia, DNA damage, unfolding protein response and DEX administration [41]. REDD1 inhibits mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle, halting protein synthesis and autophagy [41, 48]. REDD1 in mediating GC signaling to suppressed fetal BAT development and brown adipogenesis remain unexamined. We discovered that REDD1 inhibits Ppargc-1a transcription via blocking CRE promoter binding, suggesting the mediatory roles of REDD1 in linking extracellular GC signaling to reduced mitochondrial biogenesis. In skeletal muscle, REDD1 activation is reported to cause muscle atrophy [48], which may be associated with Ppargc-1a transcriptional inactivation [47, 48]. Meanwhile, fetal BAT development shapes adult BAT thermogenesis and energy expenditure [36]. We previously identified that the inactivation of fetal brown adipogenesis due to maternal GC exposure persistently impairs postnatal BAT thermogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis, substantially increasing the risks of offspring obesity and insulin resistance [46]. Thus, Redd1 may serve as a drug target to prevent the negative outcomes of maternal GC exposure on offspring BAT thermogenesis.

Taken together, maternal stress impairs postnatal thermogenic adaptation and viability. In addition to maintaining body temperature, BAT activation also protects humans from obesity and metabolic dysfunctions [22]. The uncovered GC-REDD1-Ppargc1a axis in regulating brown adipocyte differentiation may provide a therapeutic opportunity to treat maternal stress-induced intergenerational obesity and type 2 diabetic mellitus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH R01-HD067449). The authors also thank Washington State University Franceschi Microscopy & Imaging Center (Pullman, WA, USA) for help in electronic microscopy imaging.

Biographies

Yanting Chen received his B.S. degree at Jilin University in 2011, M.S. degree at China Agricultural University in 2013, and Ph.D. at Washington State University in 2017. After that, he is a postdoctoral fellow in Animal Science Department at Washington State University. His research focuses on transcriptional and epigenetic regulations on skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and mammary gland development and functions.

Dr. Min Du earned his B.S. from Zhejiang University in 1990, M.S. from China Agricultural University in 1993, and his Ph.D. from Iowa State University in 2001. He obtained his postdoctoral training in University of Alberta, Canada. He was hired as an Assistant Professor at the University of Wyoming in 2003 and moved to Washington State University as a Professor and Endowed Chair in 2011. His research focuses on the molecular mechanisms regulating mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation, and skeletal muscle and adipose tissue development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials to this article can be found online.

References

- [1].Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ, 2012, 90: 139g–149g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Obstetricians ACo Gynecologists. Acog practice bulletin: Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists number 76, october 2006: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2006, 108: 1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in africa: A systematic review. J Affect Disord, 2010, 123: 17–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, et al. Depression and treatment among u.S. Pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2012, 21: 830–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barisic A Conceived in the covid-19 crisis: Impact of maternal stress and anxiety on fetal neurobehavioral development. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol, 2020, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meylan S, Miles DB, Clobert J. Hormonally mediated maternal effects, individual strategy and global change. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences, 2012, 367: 1647–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Love OP, McGowan PO, Sheriff MJ. Maternal adversity and ecological stressors in natural populations: The role of stress axis programming in individuals, with implications for populations and communities. Functional Ecology, 2013, 27: 81–92 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mairesse J, Lesage J, Breton C, et al. Maternal stress alters endocrine function of the feto-placental unit in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2007, 292: E1526–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gitau R, Fisk NM, Glover V. Human fetal and maternal corticotrophin releasing hormone responses to acute stress. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2004, 89: F29–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smith AK, Newport DJ, Ashe MP, et al. Predictors of neonatal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity at delivery. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2011, 75: 90–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Braun T, Challis JR, Newnham JP, et al. Early-life glucocorticoid exposure: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, placental function, and long-term disease risk. Endocr Rev, 2013, 34: 885–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kumar V, Shearer JC, Kumar A, et al. Neonatal hypothermia in low resource settings: A review. J Perinatol, 2009, 29: 401–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lunze K, Bloom DE, Jamison DT, et al. The global burden of neonatal hypothermia: Systematic review of a major challenge for newborn survival. BMC Med, 2013, 11: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet, 2005, 365: 891–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mathews TJ, Menacker F, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2002 period: Linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 2004, 53: 1–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Blencowe H, Krasevec J, de Onis M, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health, 2019, 7: e849–e860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rondó PHC, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, et al. Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2003, 57: 266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lampe JB, Touch SM, Spitzer AR. Repeated antenatal steroids: Size at birth and subsequent development. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 1999, 38: 553–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jensen EC, Gallaher BW, Breier BH, et al. The effect of a chronic maternal cortisol infusion on the late-gestation fetal sheep. The Journal of endocrinology, 2002, 174: 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Vries A, Holmes MC, Heijnis A, et al. Prenatal dexamethasone exposure induces changes in nonhuman primate offspring cardiometabolic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. J Clin Invest, 2007, 117: 1058–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nkansah-Amankra S, Luchok KJ, Hussey JR, et al. Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of south carolina, 2000–2003. Matern Child Health J, 2010, 14: 215–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: Development, function and therapeutic potential. Nature medicine, 2013, 19: 1252–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lidell ME. Brown adipose tissue in human infants. Handb Exp Pharmacol, 2019, 251: 107–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang Q, Liang X, Sun X, et al. Ampk/alpha-ketoglutarate axis dynamically mediates DNA demethylation in the prdm16 promoter and brown adipogenesis. Cell metabolism, 2016, 24: 542–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rowland LA, Bal NC, Kozak LP, et al. Uncoupling protein 1 and sarcolipin are required to maintain optimal thermogenesis, and loss of both systems compromises survival of mice under cold stress. J Biol Chem, 2015, 290: 12282–12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Enerback S, Jacobsson A, Simpson EM, et al. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature, 1997, 387: 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fatemi A, Item C, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, et al. Sudden infant death: No evidence for linkage to common polymorphisms in the uncoupling protein-1 and the beta3-adrenergic receptor genes. Eur J Pediatr, 2002, 161: 337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Douglas RJ. Could a lowered level of uncoupling protein in brown adipose tissue mitochondria play a role in sids aetiology? Med Hypotheses, 1992, 37: 100–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sawczenko A, Fleming PJ. Thermal stress, sleeping position, and the sudden infant death syndrome. Sleep, 1996, 19: S267–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Miura S, Kai Y, Kamei Y, et al. Isoform-specific increases in murine skeletal muscle peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (pgc-1alpha) mrna in response to beta2-adrenergic receptor activation and exercise. Endocrinology, 2008, 149: 4527–4533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yoshioka T, Inagaki K, Noguchi T, et al. Identification and characterization of an alternative promoter of the human pgc-1alpha gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2009, 381: 537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chinsomboon J, Ruas J, Gupta RK, et al. The transcriptional coactivator pgc-1alpha mediates exercise-induced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106: 21401–21406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of pgc-1alpha, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr, 2011, 93: 884s–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Uldry M, Yang W, St-Pierre J, et al. Complementary action of the pgc-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell metabolism, 2006, 3: 333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Symonds ME. Brown adipose tissue growth and development. Scientifica (Cairo), 2013, 2013: 305763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schulz TJ, Tseng YH. Brown adipose tissue: Development, metabolism and beyond. The Biochemical journal, 2013, 453: 167–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lim WL, Idris MM, Kevin FS, et al. Maternal dexamethasone exposure alters synaptic inputs to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the early postnatal rat. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2016, 7: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Huang LT. The link between perinatal glucocorticoids exposure and psychiatric disorders. Pediatr Res, 2011, 69: 19r–25r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shoshani T, Faerman A, Mett I, et al. Identification of a novel hypoxia-inducible factor 1-responsive gene, rtp801, involved in apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol, 2002, 22: 2283–2293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, et al. Regulation of mtor function in response to hypoxia by redd1 and the tsc1/tsc2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev, 2004, 18: 2893–2904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lipina C, Hundal HS. Is redd1 a metabolic eminence grise? Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM, 2016, 27: 868–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Son JS, Zhao L, Chen Y, et al. Maternal exercise via exerkine apelin enhances brown adipogenesis and prevents metabolic dysfunction in offspring mice. Sci Adv, 2020, 6: eaaz0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, et al. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell, 1998, 92: 829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, et al. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha expression in muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100: 7111–7116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ruas JL, White JP, Rao RR, et al. A pgc-1alpha isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell, 2012, 151: 1319–1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chen YT, Hu Y, Yang QY, et al. Excessive glucocorticoids during pregnancy impair fetal brown fat development and predispose offspring to metabolic dysfunctions. Diabetes, 2020, 69: 1662–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shimizu N, Yoshikawa N, Ito N, et al. Crosstalk between glucocorticoid receptor and nutritional sensor mtor in skeletal muscle. Cell Metabolism, 2011, 13: 170–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Britto FA, Cortade F, Belloum Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-dependent redd1 expression reduces muscle metabolism to enable adaptation under energetic stress. Bmc Biol, 2018, 16: 65–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Morgan AJ, Murray KJ, Challiss RA. Comparison of the effect of isobutylmethylxanthine and phosphodiesterase-selective inhibitors on camp levels in sh-sy5y neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol, 1993, 45: 2373–2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cui H, Green RD. Regulation of the camp-elevating effects of isoproterenol and forskolin in cardiac myocytes by treatments that cause increases in camp. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2003, 307: 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Giurgescu C, Misra DP, Sealy-Jefferson S, et al. The impact of neighborhood quality, perceived stress, and social support on depressive symptoms during pregnancy in african american women. Soc Sci Med, 2015, 130: 172–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: A report from the american psychiatric association and the american college of obstetricians and gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2009, 31: 403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lucassen PJ, Bosch OJ, Jousma E, et al. Prenatal stress reduces postnatal neurogenesis in rats selectively bred for high, but not low, anxiety: Possible key role of placental 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2. Eur J Neurosci, 2009, 29: 97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lesage J, Blondeau B, Grino M, et al. Maternal undernutrition during late gestation induces fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids and intrauterine growth retardation, and disturbs the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in the newborn rat. Endocrinology, 2001, 142: 1692–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol, 2003, 157: 14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rondo PH, Ferreira RF, Nogueira F, et al. Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2003, 57: 266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Paragliola RM, Papi G, Pontecorvi A, et al. Treatment with synthetic glucocorticoids and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. International journal of molecular sciences, 2017, 18: 2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Welberg LA, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of the brain. J Neuroendocrinol, 2001, 13: 113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Emack J, Kostaki A, Walker CD, et al. Chronic maternal stress affects growth, behaviour and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function in juvenile offspring. Horm Behav, 2008, 54: 514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Nyirenda MJ, Lindsay RS, Kenyon CJ, et al. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation permanently programs rat hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucocorticoid receptor expression and causes glucose intolerance in adult offspring. J Clin Invest, 1998, 101: 2174–2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Norrbom J, Sallstedt EK, Fischer H, et al. Alternative splice variant pgc-1alpha-b is strongly induced by exercise in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 301: E1092–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chang JS, Fernand V, Zhang Y, et al. Nt-pgc-1alpha protein is sufficient to link beta3-adrenergic receptor activation to transcriptional and physiological components of adaptive thermogenesis. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287: 9100–9111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kim SH, Asaka M, Higashida K, et al. Β-adrenergic stimulation does not activate p38 map kinase or induce pgc-1α in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2013, 304: E844–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tadaishi M, Miura S, Kai Y, et al. Effect of exercise intensity and aicar on isoform-specific expressions of murine skeletal muscle pgc-1alpha mrna: A role of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 300: E341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Berdeaux R, Stewart R. Camp signaling in skeletal muscle adaptation: Hypertrophy, metabolism, and regeneration. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism, 2012, 303: E1–E17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Norrbom J, Sällstedt EK, Fischer H, et al. Alternative splice variant pgc-1α-b is strongly induced by exercise in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2011, 301: E1092–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Popov DV, Bachinin AV, Lysenko EA, et al. Exercise-induced expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α isoforms in skeletal muscle of endurance-trained males. J Physiol Sci, 2014, 64: 317–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.