Abstract

Disruption of the reparative process, often found in diabetic patients, results in chronic, non-healing wounds that significantly impact a patient’s quality of life. This highlights the need of new therapeutic options to improve the healing of diabetic wounds. In this study, we focused on developing a cell-free hydrogel dressing loaded with mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-conditioned media (CM) to potentially improve the healing of hard-to-heal wounds. We simulated a hyperglycemic environment by incubating human dermal fibroblasts in a high glucose environment (30 mM) and validated that MSC-CM rescued the impaired functions (proliferation and migration) of hyperglycemic fibroblasts. Further, we investigated the effect of loading MSC-CM in gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)-poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hybrid hydrogels in improving the proliferative activity of glucose-treated fibroblasts. The controlled release of bioactive factors from MSC-CM loaded GelMA-PEGDA hydrogels promoted the metabolic activity of hyperglycemic fibroblasts. In addition, the growth rate of hyperglycemic fibroblasts was found to be similar to that of normal fibroblasts. Our observations, thus, suggest the potential application of cell-free, MSC-secretome-loaded hydrogel in the healing of diabetic or chronic wounds.

Keywords: Diabetic wounds, Fibroblasts, Hyperglycemic, Hydrogels, Mesenchymal stem cells, Secretome

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Normal or acute wounds progress through a well-coordinated cascade of overlapping events of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, matrix deposition, angiogenesis, and re-epithelialization [1]. However, due to systemic abnormalities, such as diabetes, dysregulation of reparative process halts the typical repair process resulting in chronic (non-healing or hard-to heal) wounds. Such wounds exhibit characteristics such as persistent infections, excessive inflammation, peripheral neuropathy, impaired angiogenesis [2], and the formation of drug resistant microbial biofilms, which altogether results in the failure of these wounds to heal [3]. Because of their hard-to-heal nature and the associated challenges, chronic wounds have become a significant burden to the healthcare system with 2.4 to 4.5 million people getting affected in the United States alone [3]. Chronic wounds associated with diabetes often include leg and foot ulcers [3]. Such ulcers can linger an average of 12 to 13 months [3] and have a recurrence rate of 66% within 5 years [4], significantly reducing a patient’s quality of life. In addition, those affected are at an extreme risk for lower extremity amputation due to sepsis or osteomyelitis, which can be accompanied with morbidity, mortality, and major financial consequences. Current therapies to enhance chronic wound healing include the utilization of extracellular matrices, engineered skin, and negative pressure wound therapy [3, 4]. However, the efficacy of these therapies is limited; thereby highlighting the need of new strategies to improve healing of chronic wounds.

Due to their multipotency and ability to self-renew, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have become a focus for clinical therapeutic applications, including the restoration of tissue and the treatment of various diseases [5]. The presence of MSCs and their critical role in the inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling phases of wound healing suggest that MSC therapy is a potential option for treating hard-to-heal or non-healing wounds [6]. Studies have shown that topical applications of MSCs have improved wound healing and angiogenesis [7, 8], while injections of MSCs can decrease inflammation and increase vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [9]. However, poor engraftment efficiency, cell retention and cell survival limit the success of MSC-based therapies [10]. Recent evidence suggests that the MSC “secretome”, which is comprised of angiogenic factors, hormones, cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix proteases, plays an essential role in reparative processes [5, 11]. Studies have reported that the MSC-conditioned media improves wound healing by reducing inflammation, improving cellular functions, and enhancing granulation tissue formation [12, 13]. In addition, the superior safety profile of MSC-secretome compared to direct cell delivery [14] as well as longer shelf life makes MSC-secretome based therapy a more clinically translational strategy [15-19].

In this present study, we explored the influence of MSC-conditioned media (CM) loaded hydrogel in rescuing the impaired functions of fibroblasts in diabetic conditions. Towards this, we initially validated the ability of bone marrow derived human MSC-CM to improve the proliferation and migration of hyperglycemic fibroblasts. We simulated a diabetic environment by incubating human dermal fibroblasts in a high glucose environment of 30 mM. Next, we loaded MSC- CM within hydrogel composed of gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)-poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and confirmed improved activity of impaired fibroblasts seeded on the top of these gels in the presence of sustained release of the bioactive factors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Human (neonatal) dermal fibroblasts were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in fibroblast growth medium-2 (FGM-2, Lonza) supplemented with FGM-2 SingleQuots (containing insulin, hFGF, GA-1000, and FBS). Bone marrow-derived human MSCs were obtained from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% Penicillin Streptomycin (Pen Strep, Gibco). Cells were sustained in a humidified environment at 37 ° C and 5% carbon dioxide. Cells up to passage 7 were used in this study.

2.2. Conditioning glucose-treated fibroblasts

Fibroblasts were treated in DMEM media with 8 mM to mimic a normal glucose concentration; glucose concentrations for normal physiological conditions range from 4 to 8 mM [20]. A glucose concentration of 30 mM in DMEM media was used to simulate a diabetic/hyperglycemic environment [18, 19]. Both treatments were given to fibroblasts for 18 days.

2.3. Collection of MSC-conditioned media

50,000 MSCs were seeded in each well of a 6 well plate in complete DMEM medium. When confluency was reached, the media was replaced with serum-free DMEM medium. After 48 h, the spent media was collected and stored at −20° C until use. The MSC-conditioned media was concentrated using Vivaspin concentrators (2,000 MWCO, Sartorius). The concentrations of angiogenic (pro- and anti-) molecules within the MSC- CM was determined using Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array (R&D Systems) per manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Scratch migration assay

20,000 glucose-treated fibroblasts were seeded onto the wells of a 96 well plate. The cells were cultured in fibroblast culture media, MSC-conditioned media, and serum-free DMEM media for 48 h. Using a micropipette tip, the confluent layer of cells was scratched down the center. The cells were then washed with DPBS to remove cellular debris, media added, and images were captured using Zeiss Axio Observer A1 microscope with integrated CCD camera (t=0). The cells were then incubated for 8 h, and images of the scratch were captured (t=8). Using AxioVision software, width of the scratch was evaluated. Migration of fibroblasts was expressed as percent wound closure, using the following calculation:

At least three experiments were performed with three replicates in each experiment.

2.5. Cell proliferation on tissue culture plate

20,000 glucose-treated fibroblasts were seeded onto the wells of a 96 well plate. The cells were seeded in MSC- CM for 48 h. Cells cultured in the presence of fibroblast culture media and serum-free DMEM media acted as controls. After 48 h, the proliferative activity was measured using XTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (ATCC). Proliferation of treated fibroblasts was expressed as percent growth over the control (fibroblasts seeded in fibroblast culture media). A minimum of three experiments were performed with three replicates in each experiment.

2.6. Synthesis of methacrylated gelatin (GelMA)

Gelatin methacrylate was synthesized as described before [21]. Briefly, gelatin (type A, from porcine skin) was added to Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS, Gibco, New York) to make a 10% (w/v) solution and was stirred continuously at 50° C. To achieve methacrylation, 10% (w/v) of methacrylic anhydride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added at a rate of 0.5 mL/min and left to react for 3 hours (h) at 60° C. Following, the solution was diluted 5x with warm DPBS and transferred to dialysis cassettes (Slide-A-lyzer™, Thermo Fisher Scientific), dialyzing against distilled water at 50° C for 15 days and removing excess salts and acid. After, the solution was freeze dried, forming GelMA as a porous foam, and stored at 4° C until further use.

2.7. Fabrication and characterization of hydrogel scaffolds

200 μL of pre-polymer solutions (consisting of PEG10kDA (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 5% GelMA (w/v), and 1% photoinitiator (2-Hydroxy-4¢-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropionphenone, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)) was added to each well of a 48 well plate and exposed to UV (CL-1000 UV Crosslinker (UVP), 365 nm) for 5 min. To synthesize MSC-secretome-laden hydrogel, pre-polymer solution was created in concentrated MSC-conditioned media.

2.7.1. Compression

The stiffness of the hydrogels was measured as described earlier [21]. Briefly, the pre-polymer solutions were placed in cylindrical molds measuring 10 mm in diameter and approximately 3 mm in thickness and photo-polymerization was induced. Following which, the scaffolds were incubated in DPBS for 72 h. The hydrated samples were compressed using uniaxial testing machine (TestResources, USA) at a loading rate of 1.2 mm/min and a precision load up to 9 N. Maximum strain and stress at the moment of fracture was recorded, and the compression modulus was calculated from the initial 10% compression.

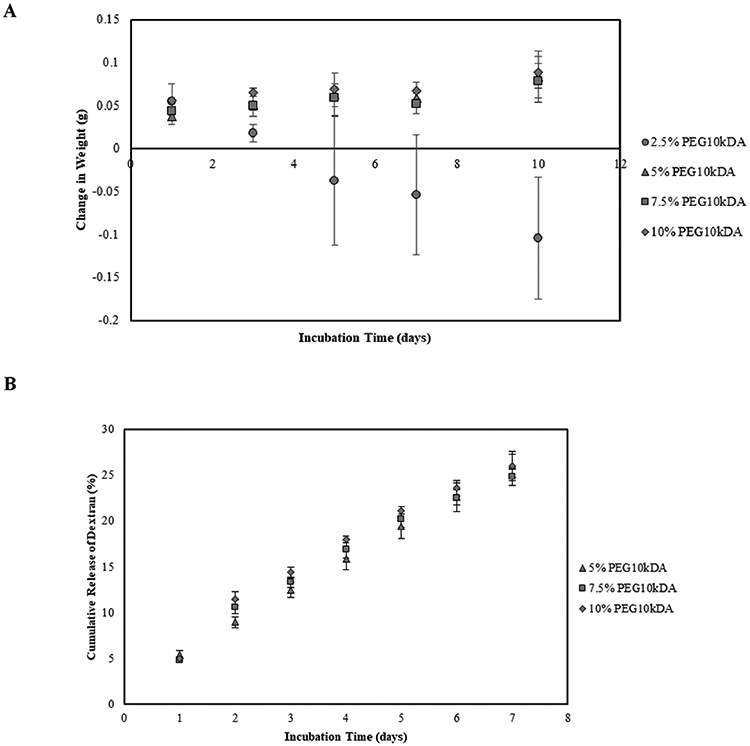

2.7.2. Degradation

Hydrogels were fabricated in 48 well plates, and the initial weights were recorded (day 0). Hydrogels were returned to well plate, and 500 μL of collagenase (Type I, 2.5 units/mL) was added on top. After 24 h (day 1), the weights of the gels were measured, and this procedure was repeated for 3, 5, 7, and 10 days. Degradation was calculated by taking the difference of sample weights at different time points from the weights recorded on day 0.

2.7.3. Porosity

Porosity was characterized by the liquid displacement method as described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, the hydrogels were incubated in water and the weights of the hydrogels before (Mwet) and after (Mdry) incubation in water was recorded. ρH20 is the density of water (1 g/mL). Porosity was calculated from the ratio of void volume (volume of water) to volume of the hydrogel.

2.7.4. Diffusion

To estimate the release kinetics of proteins from the hydrogels, the scaff olds were fabricated by incorporating 50 μg/mL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (150,000 kDA, Sigma Aldrich, USA) within the pre-polymer solutions. The dextran-loaded matrices were washed for 5 min on an orbital shaker. To facilitate the release of macromolecule from the samples, 500 μL of DPBS was added to each hydrogel and incubated at room temperature. Post incubation for 24 h, DPBS was collected and replaced with fresh buffer solution. The process was repeated over a period of 7 days. Collected samples were analyzed using SpectraMax M3 fluorescence spectrometer.

To determine the mechanism of dextran diffusion through the hydrogels, the release of macromolecules was fitted into Korsmeyer-Peppas model given by the following equation:

where, F is the fractional release of the molecule, Mt is the amount of dextran released at any time point, M0 is the total mass of dextran that was encapsulated within the initial hydrogels, k1 is the kinetic constant, t is the release time, and n is the diffusional exponent. For n ≤ 0.5, the transport of macromolecules is regulated by diffusion, 0.5 ≤ n ≤ 0.9 both by diffusion as well as polymer relaxation/erosion, and for n≥ 0.9, the transport of molecules is governed via polymer chain relaxation/erosion.

2.8. Cell proliferation on hydrogel scaffolds

50 μL of pre-polymer solutions were added to each well of a 96 well plate and UV cured to generate the hydrogels. The concentrations of PEG10kDA was varied from 5% to 10% while maintaining the concentration of GelMA constant at 5%. After fabrication, the hydrogels were washed three times, and 20,000 fibroblasts were seeded on top of the hydrogel matrix in fibroblast culture media. After 48 h, cell proliferation was measured using XTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit. To investigate the ability of bioactive factors released by MSCs to rescue the impaired function of glucose-treated fibroblasts, cells were seeded on top of hydrogels in the presence of MSC- CM. Cells seeded in presence of fibroblast culture media and serum-free DMEM media acted as controls.

To assess the effect of sustained release of bioactive factors on the proliferation of glucose-treated fibroblasts, MSC-CM -loaded hydrogels were fabricated. Fibroblasts were seeded on these gels and proliferation was measured 48 h and 96 h after seeding. Cells seeded in presence of fibroblast culture media and serum-free DMEM acted as controls.

For all experiments, cell growth was expressed as percent growth over the proliferation of fibroblasts seeded directly on tissue culture plate (TCP) in presence of fibroblasts culture media. At least three experiments were performed with three replicates in each experiment.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicates and repeated at least three times. Statistical analyses were carried out using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test. Differences between two sets of data were considered statistically significant at p-value less than 0.05. Data has been represented as (mean ± error). Error is standard error of the mean (S.E.M) (N=3).

3. Results

Hyperglycemia is encountered during many pathologic conditions including diabetes mellitus, sepsis, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome due to reduced ability to metabolize glucose. To simulate diabetic/hyperglycemic conditions, in accordance with other studies [23, 24], human dermal fibroblasts were incubated in DMEM media with 30 mM glucose (high glucose, HG). To recapitulate the normal glucose condition, the fibroblasts were also cultured in 8mM glucose (normal glucose, NG).

3.1. Glucose treatment impaired the functions of fibroblasts

To investigate the effect of hyperglycemic conditions on the cellular processes, proliferative and migratory activities of glucose-treated fibroblasts were assessed and compared with untreated fibroblasts. As observed in Figure 1A, the proliferation of HG cells in fibroblast culture medium (F) was found to be significantly reduced as compared to untreated fibroblasts (p-value < 0.05). No statistical difference in growth of NG fibroblasts was observed with respect to the untreated cells (p-value > 0.05). The proliferative activity of these cells in serum-free DMEM media (D) was also assessed. Lack of serum reduced the growth of fibroblasts irrespective of glucose treatment. However, most prominent effect was observed in case of cells maintained under HG conditions whereby 36% reduction in proliferation was observed compared to HG cells under normal growth media. The migratory activity of fibroblasts was assessed via wound closure assay. As seen in Figure 1B, a subtle decrease in the migratory activity of HG fibroblasts, as manifested from reduced wound closure, was observed when compared to untreated cells in the presence of normal fibroblast growth media. However, the difference was not statistically significant (p-value > 0.05). In serum-free media, the closure of wound by fibroblasts irrespective of glucose treatment was reduced. Taken together, our observations confirmed that culture of fibroblasts under high glucose conditions impaired their functions. No difference in the activities was observed upon treatment under normal glucose condition.

Figure 1.

Effect of MSC-secretome on the proliferation and migration assay of glucose-treated fibroblasts. Untreated (Control), high glucose (HG) and normal glucose (NG) treated fibroblasts were seeded on well plates in fibroblast culture media (F), MSC-conditioned media (C), and serum-free DMEM media (D). Assays were carried out 48 h after seeding. A) Cell growth was normalized with respect to control cells cultured in the presence of normal growth media. * indicates p<0.05 compared to Control-F. ** indicates p<0.05 compared to Control-C. Error bars are SEM (N=3). B) Scratch was induced via pipet tip, and after 8 h, the percent wound closure was analyzed. * indicates p<0.05 compared to Control-F. ** indicates p<0.05 compared to Control-C. C) Expression of angiogenic-related molecules found in MSC-conditioned media measured using Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array. The signals corresponding to different angiogenic molecules were normalized with respect to the references.

3.2. MSC-secretome rescues the functions of impaired fibroblasts

To assess whether MSC secretome can improve the functions of fibroblasts cultured under hyperglycemic conditions, we assessed the proliferation and migration of the cells in the presence of MSC-CM (C). As observed in Figure 1A, proliferation of fibroblasts, in the presence of MSC- CM, increased irrespective of glucose treatment. The maximal increase was observed for HG fibroblasts (66.6% with respect to proliferation in presence of serum-free DMEM) (p-value< 0.05). On the other hand, 27.6% and 22.3% increase in proliferation was observed for untreated and NG fibroblasts, respectively. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed in the proliferation of HG fibroblasts when incubated with MSC-CM as compared to fibroblast culture medium supplemented with cocktails of growth factors (p-value > 0.05). MSC-secretome also significantly enhanced migratory activity of HG fibroblasts, as manifested from enhanced wound closure, compared to the serum-free media and fibroblast growth media (p-value < 0.05) (Figure 1B). In addition, motility of fibroblasts (percent wound closure) in presence of MSC-CM was found to be comparable, irrespective of glucose treatment (Figure 1B) (p-value > 0.05). Taken together, our observations demonstrate recovery of impaired functions of HG fibroblasts in the presence MSC- CM confirming that MSC-secretome could be an ideal candidate for treatment of chronic wounds.

Studies have attributed the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs to their paracrine signaling [11, 25]. In this study, the factors in MSC-CM that might potentiate the enhanced proliferation and migration of HG fibroblasts were assessed via Proteome Profiler™ Human Angiogenesis Antibody Array. Several biomolecules demonstrated to contribute to the healing of wounds by promoting the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and stimulation of angiogenesis [26-28] including epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 (IGFBP-2), fibroblast growth factor acidic (FGF acidic), fibroblast growth factor basic (FGF basic), activin A, platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGF AA), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were observed in the MSC-CM (Figure 1C). .

3.3. Characterization of hydrogels

Towards the long-term goal of developing cell-free wound dressing to improve healing of diabetic wounds, hydrogels were fabricated and characterized. In this study, the concentration of PEG10kDA was varied from 2.5%, 5.0%, 7.5%, and 10.0% (w/v) while maintaining the concentration of GelMA constant at 5.0%. This permitted variation of matrix stiffness (Table 1) without altering the concentration of cell adhesive sites. The integrity of the hydrogels was assessed over a period of 10 days. As demonstrated in Figure 2A, no difference in the degradation profile of the hydrogels fabricated with 5.0%, 7.5% and 10.0% PEG10kDA was observed (p-value > 0.05). However, a decrease in integrity was observed in case of gels synthesized with 2.5% PEG10kDA. This increased rate of degradation (Table 1) can be attributed to the reduced crosslinking density in 2.5% PEG10kDA gels. Since, hydrogels with PEG10kDA concentration varying from 5.0% to 10.0% maintained their integrity over the span of 10 days, they were used for further studies. Porosity of the hydrogels was assessed via liquid displacement method. As demonstrated in Table 2, increasing the concentration of PEG10kDA did not have a significant effect on the porosity of the scaffolds (p-value > 0.05). To investigate the influence of PEG10kDA concentration on the transport of macromolecules from the gels, the diffusion of FITC-dextran molecules was monitored over a span of 7 days. As demonstrated in Figure 2B, no significant difference in the cumulative release of dextran was observed when varying the concentration of PEG10kDA from 5.0% to 10.0%. Dextran release was fitted into the Korsmeyer-Peppas transport model, which describes macromolecule release from a polymeric system [29]. Within this model, the diffusional exponent, n, indicates the mechanism of macromolecular transport through the hydrogel scaffolds. The values of the exponent, n, was found to range between 0.5 and 0.9 for all hydrogel compositions (Table 2), indicating that the release of dextran was governed both by diffusion as well as polymer relaxation. Further, there was no statistical difference between the diffusional exponents when the PEG10kDA concentration was varied.

Table 1.

Compression modulus and degradation rate of hydrogel matrices as a function of PEG10kDA concentration. Degradation rate was measured over 10 days and calculated by taking the change in weight over incubation time (g/days). Data represented as (mean ± error). Error is S.E.M (N=3).

| PEG10kDA (%) | Compression Modulus (kPa) | Degradation Rate (change in weight/incubation time, g/day) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 1.58 ± 0.29 | −0.018 ± 0.009 |

| 5 | 4.99 ± 1.02 | 0.005 ± 0.002 |

| 7.5 | 12.52 ± 1.25 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| 10 | 21.87 ± 1.32 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

Figure 2.

A) Degradation of hydrogels over 10 days presented as change in weight with respect to the initial weight of the scaffolds. Error bars are S.E.M (N=3). B) Percent of cumulative dextran released from GelMA-PEG10kDA hybrid hydrogels over an incubation period of 7 days. Error bars are SEM (N≥3).

Table 2.

Porosity and diffusional exponent of hydrogels with varying PEG10kDA concentrations from 5% to 10%. Data represented as (mean ± error). Error is S.E.M (N=3).

| PEG10kDA (%) | Porosity (%) | Diffusional Exponent, n |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 69.05 ± 10.11 | 0.846 ± 0.012 |

| 7.5 | 65.42 ± 10.81 | 0.753 ± 0.051 |

| 10 | 62.39 ± 11.35 | 0.731 ± 0.060 |

3.4. Combinatorial effect of hydrogel and media supplementation on proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts

Since the matrix stiffness has been demonstrated to regulate proliferation of different cells [30, 31], initially the growth of fibroblasts was assessed as a function of PEG10kDA concentration (matrix modulus). Untreated fibroblasts were seeded on top on the hydrogels in fibroblast culture media, and proliferation was measured after 48 h. Fibroblasts seeded on tissue culture plate (TCP) acted as the control. As demonstrated in Figure 3A, cells seeded on top of 5.0% PEG10kDA hydrogels exhibited the highest percent growth at 14.0 ± 2.1%. Further increasing the concentration of PEG10kDa did not alter the rate of proliferation of fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

Proliferation assay. A) Untreated fibroblasts were seeded on hydrogels with a varying PEG10kDA concentration from 5% to 10%. B) Untreated fibroblasts were seeded on 5% PEG10kDA hydrogels in the presence of fibroblast culture media (F), MSC-conditioned media (C), and serum-free DMEM media (D). C) Untreated fibroblasts were seeded on 5% PEG10kDA and 5% GelMA hybrid hydrogels loaded with either normal culture media (F) or MSC-conditioned media (C). The proliferation of fibroblasts under sustained release of media supplementation was compared to the proliferation of fibroblasts in the presence of direct administration of media. * indicates p<0.05 compared to F-Direct Administration and C-Direct Administration. Error bars are S.E.M (N≥4). D) Glucose-treated fibroblasts (HG and NG) were seeded on top of 5% PEG10kDA/GelMA hydrogels loaded with fibroblast culture media (FMH) or with MSC-conditioned media (CMH) and proliferation analyzed after 48 h and 96 h. Cell growth values were normalized with respect to fibroblasts seeded on TCP in fibroblast culture media. Error bars are SEM (N≥3). * indicates p<0.05 compared to HG-CMH (48 h).

Because maximal growth of untreated fibroblasts was obtained with 5.0% PEG10kDA with 5.0% GelMA, this composition of hydrogel was selected for further studies. To investigate the effect of media supplementation, fibroblasts were seeded on the hydrogel in the presence of serum-free DMEM, normal fibroblast culture media, and MSC-CM. As observed in Figure 3B, MSC- CM (enriched with bioactive factors secreted by MSCs) enhanced the proliferative activity of the cells. Compared to normal growth media and serum-free DMEM, an increase of 41.3% and 86.5% in proliferation was observed in the presence of MSC-CM.

We further compared the influence of sustained release of MSC-CM on the growth of fibroblasts. For the purpose, 5.0% PEG10kDA and 5.0% GelMA hybrid hydrogels were loaded with either MSC-CM or normal culture media and fibroblasts were seeded on the top. As demonstrated in Figure 3C, sustained release of bioactive factors significantly enhanced the proliferation of fibroblasts, irrespective of media composition.

3.5. Proliferation of glucose-treated fibroblasts on MSC-secretome-loaded hydrogel

Since maximal proliferation was observed when fibroblasts were seeded on 5.0% PEG10kDA hydrogels in the presence of sustained release of bioactive factors, the combinatorial effect of optimized hydrogel stiffness/composition and sustained release of bioactive molecules secreted by MSCs on the proliferative effect of glucose-treated fibroblasts was investigated. HG and NG cells were seeded on top of 5% PEG10kDA/GelMA hydrogels loaded with fibroblast culture media (FMH) or MSC-conditioned media (CMH). Proliferation of fibroblasts was measured 48 h and 96 h after seeding. Compared to fibroblast culture media, an increase of 13.5% and 2.9% in proliferation of HG cells was observed after 48 h and 96 h (Figure 6). In case of NG cells, the increase in proliferation was 12.4 % and 2.9% after 48 h and 96 h.

4. Discussion

MSC-based therapies have shown promise in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds by promoting rapid wound closure and increasing angiogenesis, cell proliferation and collagen synthesis [7]. Not only MSC treatment improved the healing time, there was also a reduction in topical pro-inflammatory reactions and an increase of VEGF production [9]. Despite these promising results, low retention and engraftment of MSCs at the target site [10] and challenges associated with purification and expansion of MSCs in vitro [32] limit the clinical translation of MSC-based therapy. Mounting evidence corroborates that MSCs can enhance wound healing through their paracrine secretions. Secretome from MSCs not only demonstrated therapeutic benefits similar to those observed upon direct delivery of MSCs [5, 17, 33], but can potentially circumvent many side effects including uncontrolled differentiation of engrafted MSCs [34, 35]. In addition, MSC-secretome could be produced from commercially available cell lines [36], stored for long periods of time without functional loss [37], have longer shelf life and superior safety profile compared to cell transplantation [14]. Thus, administration of MSC-secretome has emerged as a new, cell-free therapeutic approach in tissue repair and regeneration.

In this study, we investigated the influence of sustained release of MSC-secreted bioactive factors from a hybrid hydrogel composed of PEG10kDa and GelMA in improving the impaired functions of hyperglycemic dermal fibroblasts. The delivery of MSC-secretome to enhance wound healing has been explored in various studies. MSC-secreted exosomes enhanced proliferation and migration of fibroblasts, activated important signaling pathways in wound healing, and increased expression of several growth factors. Studies utilizing the MSC-secretome harvested from cell culture media have also reported to improve the reparative process of wound healing [17]. Enhancement of the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes that were exposed to a diabetic microenvironment has been demonstrated [12]. Another study reported that MSC-CM enhanced diabetic wound healing in vivo when studying inflammation, vascularization, granulation tissue formation, and gene expression [13]. Consistent with these reports, we observed improvement of functions of hyperglycemic fibroblasts, as manifested from enhanced proliferation and migration, in the presence of MSC-CM. This observation could be attributed to the high expressions of various bioactive factors including VEGF, uPA, and IGFBP-1 in MSC-conditioned media. VEGF was shown to stimulate the migration of fibroblasts in vitro [27]. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) is a key regulator of fibroblast migration, but is not crucial for proliferation [28]. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) was found to increase migration of hyperglycemic fibroblasts to levels observed in normoglycemia [26].

Towards developing a cell-free regenerative platform that could provide a structural backbone for cellular organization, ingrowth and neovascularization at the wound site, we loaded MSC-secretome within hybrid hydrogel. Hydrogels have been commonly exploited as wound dressings due to their 3D hydrophilic, porous structures and resemblance to native tissue [38, 39]. Because of their extremely hydrophilic structure, hydrogels have the ability to absorb and retain wound exudates while retaining a moist environment for wound healing. In addition, therapeutic agents can be incorporated into the hydrogel networks and delivered to the wound site in a more prolonged, sustainable release, bringing advantages over topical administration of biomolecules [40].

In this study, hybrid hydrogel composed of GelMA-PEGDA, which leverages the reproducibility and stability of synthetic polymers with the biocompatibility of natural materials, was used. The hydrogel with a composition of 5.0% PEG10kDA and 5.0% GelMA was found to be effective in promoting the proliferative activity of fibroblasts. Further, it was demonstrated that the sustained release of bioactive factors (from MSC-CM loaded hydrogels) enhanced the proliferation of hyperglycemic fibroblasts similar to the normal fibroblasts (cultured under normal glucose condition). Our study is indicative that the combinatorial effect of matrix properties and sustained release of MSC-secreted bioactive molecules can potentially rescue the diabetes-associated impaired wound healing.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank National Institutes of Health (1R03EB026526-01) and University of Michigan-Dearborn Office of Sponsored Research for their financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with regard to this manuscript.

Ethics

The cell lines were procured.

References

- 1.Gonzalez AC, Costa TF, Andrade ZA, & Medrado AR (2016). Wound healing - A literature review. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia, 91(5), 614–620. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fadini GP, Albiero M, Bonora BM, & Avogaro A (2019). Angiogenic Abnormalities in Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanistic and Clinical Aspects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 104(11), 5431–5444. 10.1210/jc.2019-00980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frykberg RG, & Banks J (2015). Challenges in the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Advances in wound care, 4(9), 560–582. 10.1089/wound.2015.0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt D (2009). Diabetes: foot ulcers and amputations. BMJ clinical evidence, 2009, 0602. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira JR, Teixeira GQ, Santos SG, Barbosa MA, Almeida-Porada G, & Gonçalves RM (2018). Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome: Influencing Therapeutic Potential by Cellular Pre-conditioning. Frontiers in immunology, 9, 2837. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Lorenz HP, Longaker MT, & Wan DC (2018). Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Cutaneous Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review of the Background, Role, and Therapeutic Potential. Stem cells international, 2018, 6901983. 10.1155/2018/6901983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JW, Lee JH, Lyoo YS, Jung DI, & Park HM (2013). The effects of topical mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in canine experimental cutaneous wounds. Veterinary dermatology, 24(2), 242–e53. 10.1111/vde.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javazon EH, Keswani SG, Badillo AT, Crombleholme TM, Zoltick PW, Radu AP, Kozin ED, Beggs K, Malik AA, & Flake AW (2007). Enhanced epithelial gap closure and increased angiogenesis in wounds of diabetic mice treated with adult murine bone marrow stromal progenitor cells. Wound repair and regeneration: official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society, 15(3), 350–359. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo YR, Wang CT, Cheng JT, Wang FS, Chiang YC, & Wang CJ (2011). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhanced diabetic wound healing through recruitment of tissue regeneration in a rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 128(4), 872–880. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182174329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kean TJ, Lin P, Caplan AI, & Dennis JE (2013). MSCs: Delivery Routes and Engraftment, Cell-Targeting Strategies, and Immune Modulation. Stem cells international, 2013, 732742. 10.1155/2013/732742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui F, Babitz SK, Rhee A, Hile KL, Zhang H, & Meldrum KK (2017). Mesenchymal stem cells protect against obstruction-induced renal fibrosis by decreasing STAT3 activation and STAT3-dependent MMP-9 production. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology, 312(1), F25–F32. 10.1152/ajprenal.00311.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li M, Zhao Y, Hao H, Dai H, Han Q, Tong C, Liu J, Han W, & Fu X (2015). Mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves the proliferation and migration of keratinocytes in a diabetes-like microenvironment. The international journal of lower extremity wounds, 14(1), 73–86. 10.1177/1534734615569053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saheli M, Bayat M, Ganji R, Hendudari F, Kheirjou R, Pakzad M, Najar B, & Piryaei A (2020). Human mesenchymal stem cells-conditioned medium improves diabetic wound healing mainly through modulating fibroblast behaviors. Archives of dermatological research, 312(5), 325–336. 10.1007/s00403-019-02016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang J, Shen D, Caranasos TG, Wang Z, Vandergriff AC, Allen TA, Hensley MT, Dinh PU, Cores J, Li TS, Zhang J, Kan Q, & Cheng K (2017). Therapeutic microparticles functionalized with biomimetic cardiac stem cell membranes and secretome. Nature communications, 8, 13724. 10.1038/ncomms13724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bari E, Perteghella S, Catenacci L, Sorlini M, Croce S, Mantelli M, Avanzini MA, Sorrenti M, Torre ML (2019). Freeze-dried and GMP-compliant pharmaceuticals containing exosomes for acellular mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulant therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond). 14(6):753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bari E, Perteghella S, Silvestre DD, Sorlini M, Catenacci L, Sorrenti M, Marrubini G, Rossi R, Tripodo G, Mauri P, Marazzi M, Torre ML (2018). Pilot Production of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Freeze-Dried Secretome for Cell-Free Regenerative Nanomedicine: A Validated GMP-Compliant Process. Cells. 7 (11), 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bari E, Silvestre DD, Mastracci L, Grillo F, Grisoli P, Marrubini G, Nardini M, Mastrogiacomo M, Sorlini M, Rossi R, Torre ML Mauri P, Sesana G, Perteghella S (2020). GMP-compliant sponge-like dressing containing MSC lyo-secretome: Proteomic network of healing in a murine wound model. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 155, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bari E, Ferrarotti I, Silvestre DD, Grisoli P, Barzon V, Belderacchi A, Torre ML, Rossi R, Mauri P, Corsico AG, Perteghella S (2019). Adipose mesenchymal extracellular vesicles as alpha-1-antitrypsin physiological delivery systems for lung regeneration. Cells. 8(9), 965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bari E, Ferrarotti I, Torre ML, Corsico AG, Perteghella S (2019). Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell secretome for lung regeneration: The long way through "pharmaceuticalization" for the best formulation. J Control Release. 309,11–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou Y, Zhou M, Xie J, Chao P, Feng Q, & Wu J (2017). High glucose levels promote the proliferation of breast cancer cells through GTPases. Breast cancer (Dove Medical Press), 9, 429–436. 10.2147/BCTT.S135665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y, Al-Ameen MA, & Ghosh G (2014). Integrated effects of matrix mechanics and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) on capillary sprouting. Annals of biomedical engineering, 42(5), 1024–1036. 10.1007/s10439-014-0987-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohanty S, Wu Y, Chakraborty N, Mohanty P, & Ghosh G (2016). Impact of alginate concentration on the viability, cryostorage, and angiogenic activity of encapsulated fibroblasts. Materials science & engineering. C, Materials for biological applications, 65, 269–277. 10.1016/j.msec.2016.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu X, Fang T, Kang P, Hu J, Yu Y, Li Z, Cheng X, & Gao Q (2017). Effect of ALDH2 on High Glucose-Induced Cardiac Fibroblast Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2017, 9257967. 10.1155/2017/9257967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang L, Wang Y, Zheng M, Wang Q, Lin H, Zhang L, & Wu L (2016). Transcriptomic study of high glucose effects on human skin fibroblast cells. Molecular medicine reports, 13(3), 2627–2634. 10.3892/mmr.2016.4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X, Ding Y, Zhang Y, Tse HF, & Lian Q (2014). Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell transplantation, 23(9), 1045–1059. 10.3727/096368913X667709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandt K, Grünler J, Brismar K, & Wang J (2015). Effects of IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-2 and their fragments on migration and IGF-induced proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts. Growth hormone & IGF research: official journal of the Growth Hormone Research Society and the International IGF Research Society, 25(1), 34–40. 10.1016/j.ghir.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brem H, Kodra A, Golinko MS, Entero H, Stojadinovic O, Wang VM, Sheahan CM, Weinberg AD, Woo SL, Ehrlich HP, & Tomic-Canic M (2009). Mechanism of sustained release of vascular endothelial growth factor in accelerating experimental diabetic healing. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 129(9), 2275–2287. 10.1038/jid.2009.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madhyastha HK, Radha KS, Nakajima Y, Omura S, & Maruyama M (2008). uPA dependent and independent mechanisms of wound healing by C-phycocyanin. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 12(6B), 2691–2703. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00272.X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dash S, Murthy PN, Nath L, and Chowdhury P (2010). Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica, 67(3), 217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Mohri H, Wu Y, Mohanty S, & Ghosh G (2017). Impact of matrix stiffness on fibroblast function. Materials science & engineering. C, Materials for biological applications, 74, 146–151. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasser M, Wu Y, Danaoui Y, & Ghosh G (2019). Engineering microenvironments towards harnessing pro-angiogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Materials science & engineering. C, Materials for biological applications, 102, 75–84. 10.1016/j.msec.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mastrolia I, Foppiani EM, Murgia A, Candini O, Samarelli AV, Grisendi G, Veronesi E, Horwitz EM, & Dominici M (2019). Challenges in Clinical Development of Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells: Concise Review. Stem cells translational medicine, 8(11), 1135–1148. 10.1002/sctm.19-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrell CR, Fellabaum C, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, & Volarevic V (2019). Molecular Mechanisms Responsible for Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Secretome. Cells, 8(5), 467. 10.3390/cells8050467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gazdic M, Volarevic V, Arsenijevic N, & Stojkovic M (2015). Mesenchymal stem cells: a friend or foe in immune-mediated diseases. Stem cell reviews and reports, 11(2), 280–287. 10.1007/s12015-014-9583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glassberg MK, Minkiewicz J, Toonkel RL, Simonet ES, Rubio GA, DiFede D, Shafazand S, Khan A, Pujol MV, LaRussa VF, Lancaster LH, Rosen GD, Fishman J, Mageto YN, Mendizabal A, & Hare JM (2017). Allogeneic Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis via Intravenous Delivery (AETHER): A Phase I Safety Clinical Trial. Chest, 151(5), 971–981. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sears V, & Ghosh G (2020). Harnessing mesenchymal stem cell secretome: Effect of extracellular matrices on proangiogenic signaling. Biotechnology and bioengineering, 117(4), 1159–1171. 10.1002/bit.27272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Hu S, Yang H, Li Z, Huang K, Su T, Wang S, & Cheng K (2019). Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Integrated with Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Secretome to Treat Endometrial Injury in a Rat Model of Asherman's Syndrome. Advanced healthcare materials, 8(14), e1900411. 10.1002/adhm.201900411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nardini M, Perteghella S, Mastracci L, Grillo F, Marrubini G, Bari E, Formica M, Gentili C, Cancedda R Torre ML, Mastrogiacomo M (2020). Growth factors delivery system for skin regeneration: an advanced wound dressing. Pharmaceutics. 12 (2), 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bari E, Perteghella S, Faragò S, Torre ML (2018). Association of silk sericin and platelet lysate: Premises for the formulation of wound healing active medications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 119, 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Silva LP, Reis RL, Correlo VM, & Marques AP (2019). Hydrogel-Based Strategies to Advance Therapies for Chronic Skin Wounds. Annual review of biomedical engineering, 21, 145–169. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-060418-052422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]