Keywords: nodose, NTS, pregnenolone sulfate, quantal, temperature

Abstract

Vagal afferent fibers contact neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and release glutamate via three distinct release pathways: synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous. The presence of TRPV1 in vagal afferents is predictive of activity-dependent asynchronous glutamate release along with temperature-sensitive spontaneous vesicle fusion. However, pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of TRPV1 does not eliminate the asynchronous profile and only attenuates the temperature-dependent spontaneous release at high temperatures (>40°C), indicating additional temperature-sensitive calcium conductance(s) contributing to these release pathways. The transient receptor potential cation channel melastatin subtype 3 (TRPM3) is a calcium-selective channel that functions as a thermosensor (30–37°C) in somatic primary afferent neurons. We predict that TRPM3 is expressed in vagal afferent neurons and contributes to asynchronous and spontaneous glutamate release pathways. We investigated these hypotheses via measurements on cultured nodose neurons and in brainstem slice preparations containing vagal afferent to NTS synaptic contacts. We found histological and genetic evidence that TRPM3 is highly expressed in vagal afferent neurons. The TRPM3-selective agonist, pregnenolone sulfate, rapidly and reversibly activated the majority (∼70%) of nodose neurons; most of which also contained TRPV1. We confirmed the role of TRPM3 with pharmacological blockade and genetic deletion. In the brain, TRPM3 signaling strongly controlled both basal and temperature-driven spontaneous glutamate release. Surprisingly, genetic deletion of TRPM3 did not alter synchronous or asynchronous glutamate release. These results provide convergent evidence that vagal afferents express functional TRPM3 that serves as an additional temperature-sensitive calcium conductance involved in controlling spontaneous glutamate release onto neurons in the NTS.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Vagal afferent signaling coordinates autonomic reflex function and informs associated behaviors. Thermosensitive transient receptor potential (TRP) channels detect temperature and nociceptive stimuli in somatosensory afferent neurons, however their role in vagal signaling remains less well understood. We report that the TRPM3 ion channel provides a major thermosensitive point of control over vagal signaling and synaptic transmission. We conclude that TRPM3 translates physiological changes in temperature to neurophysiological outputs and can serve as a cellular integrator in vagal afferent signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Vagal afferent neurons relay sensory information from visceral organs to the brainstem nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and initiate autonomic reflex pathways (1–3). Central vagal afferent terminals release glutamate via both action-potential-dependent (synchronous and asynchronous release) and -independent (spontaneous) release pathways (4). Together these distinct forms of fast neurotransmission shape the charge transfer profile at this synapse and convey information over a relatively broad timescale (milliseconds to seconds) (4, 5). Both asynchronous and spontaneous forms of quantal vesicle release are abundant at this synapse and highly temperature sensitive. This unique temperature sensitivity is due, in part, to the functional expression of thermosensitive transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels (6–10).

TRP ion channel function is well characterized in somatic sensory neurons where they control neuronal excitability at both the peripheral and central nerve terminals and largely mediate thermo- and nociception (11). Our work and others have begun to detail that primary vagal afferent neurons also express an array of TRP channels, yet their role in signaling in autonomic neurons and within the central nervous system is unclear (12). Spontaneous glutamate release from central vagal afferent terminals is temperature sensitive and partly relies on the contribution of TRPV1 for these responses (13). However, genetic ablation of TRPV1 receptors does not completely eliminate temperature sensitivity, suggesting that additional temperature-gated ion channels may be present and contribute to these responses (9). In addition to TRPV1, a relatively small subgroup of TRP channels are thermosensitive, and generally, coexpress within neurons to detect a wide range of temperatures (14–16). Core body temperatures in mammals vary over a narrow range in response to circadian rhythms, feeding, and fever (17–19). Thus, we began investigating the functional expression of TRP ion channels that are active within the physiological temperature range. We hypothesized that the TRP melastatin subtype 3 (TRPM3) ion channel may contribute to vagal afferent signaling by conveying temperature fluctuations within the physiological range through changes in quantal glutamate release.

Similar to other TRP channels, TRPM3 is a tetrameric calcium-permeable nonselective cation channel with a PCa/PCs of 10 (20, 21). TRPM3 is gated by many stimuli, including neurosteroids, such as pregnenolone sulfate (PregS), and warm temperature (30–37°C) (22, 23). In spinal and primary trigeminal afferent neurons, TRPM3 contributes to detection of noxious heat stimuli and is broadly coexpressed with TRPV1 (22). Immunohistochemical staining in vagal afferent neurons shows that a majority of neurons contain TRPM3 (∼80%), which largely overlaps with TRPV1 expression (24). Functional expression was additionally confirmed in airway-specific afferents with calcium imaging and single-unit recordings, where TRPM3 activation increased neuronal excitability (25). These findings strongly suggest that TRPM3 could be an endogenous thermosensor in vagal afferent neurons and its expression on afferent terminals may contribute to the control of central synaptic glutamate release.

Here, we extend the characterization of TRPM3 in vagal afferent neurons using immunohistochemical, molecular, and functional assays. We detail ligand pharmacology and electrophysiological properties in dissociated nodose neurons, and test the hypothesis that TRPM3 contributes to the control of glutamate release.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (120–250 g; Simonsen Laboratories), male C57BL/6 mice (20–30 g), and TRPM3-knockout (TRPM3 KO) mice; (20–30 g) were used under procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Washington State University. Animals were housed under 12 h light/12 h dark conditions and fed standard pellet chow ad libitum.

Immunohistochemistry

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Simonsen) were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Nodose ganglia and brain were then removed, postfixed, and cryoprotected in 25% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Frozen nodose ganglia were sectioned at 15 µm using a Leica cryostat and were directly mounted to slides. For nodose slices, all further reactions occurred on the slides are similar to the brainstem slices. Frozen coronal sections of the brainstem containing the NTS were taken at 30 µm. These sections were incubated in anti-TRPM3 primary antibody (1:200 dilution, rabbit anti-TRPM3, NB100-98864, lot #401451; Novus Biologicals) free-floating overnight at 4°C, then in AlexaFluor-555 (1:400 dilution, donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody, A31572, lot #1134920; Life Technologies) secondary antibody for 5 h at room temperature. Omission controls were run in parallel and included removal of either the primary or secondary antibody. Once complete, the sections were washed, mounted on Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and dried. Coverslips were mounted on the slides using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies) and allowed to dry overnight. Slides were then imaged on a Nikon Eclipse 80i and processed using Nikon Elements image software (Nikon Instruments). Images were collected with identical exposure settings within an antibody.

Molecular Biology

Total RNA was extracted from rat nodose ganglia using the Qiazol Reagent (Qiagen) and steel beads in the TissueLyser (Qiagen). The RNA was then purified using the RNeasy Micro kit on the QIAcube and quantified using the Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of cDNA were synthesized using the Ambion DNA-free kit (Life Technologies) in combination with the Quantitect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) was carried out using IDT primer sets and Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were run with three technical replicates with primer-only as a negative control, and a melt curve was run to ensure amplification of a single product. The ΔCT method of analysis was used with GAPDH as the housekeeping gene, and relative abundance was calculated as 2−ΔCt. See Table 1 for forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sequences.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

| TRPM3 F | CAC GTG CAG CCA GAT GTT AC |

| TRPM3 R | GAA CTC CAA GCT GAG AAT TGA AG |

| TRPV1 F | GGC TGT CTT CAT CAT CCT GTT A |

| TRPV1 R | GTT CTT GCT CTC TTG TGC AAT C |

| GAPDH F | CGT GTT CCT ACC CCC AAT GT |

| GAPDH R | ACA GGA GAC AAC CTG GTC CT |

Nodose Ganglion Isolations and Primary Neuronal Cultures

Nodose ganglia were isolated bilaterally from rats and mice under a deep plane of anesthesia (ketamine, 25 mg/100 g; with xylazine, 2.5 mg/100 g) using aseptic surgical conditions as previously reported (26, 27). Following a midline incision in the neck, the musculature was retracted and blunt dissection techniques were used to dissociate the vagal trunk from the common carotid artery. High-magnification optics (×10–100 dissecting scope; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) were used to visualize the nodose ganglia and facilitate complete removal. Once isolated, nodose ganglia were desheathed and digested in Ca2+/Mg2+ free Hank’s balanced salt solution containing 1 mg/mL of both dispase II (Hoffmann-La Roche) and collagenase type 1 A (Sigma Aldrich) (90 min at 37°C in 95% air/5% CO2). Neurons were dispersed by gentle trituration through siliconized pipettes (Sigmacote, Sigma Aldrich), and then, washed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Dispersed cells were plated onto poly-lysine-coated coverslips and maintained in DMEM + 10% FBS (37°C in 95% air/5% CO2). Measurements were made within 24 h of isolation.

Ratiometric Fluorescent Calcium Measurements

Intracellular calcium measurements were made with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Manipulations were made at room temperature in a physiological saline bath (in mM: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 6 glucose, and 10 HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). High K+ bath (HiK) had 55 mM KCl with an equimolar reduction of NaCl to 90 mM. Neurons on coverslips were loaded with 1 μM Fura-2-AM for 1 h followed by a 15 min wash for de-esterification. Coverslips were mounted into a closed chamber and constantly perfused with physiological bath. Fluorescence was measured using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) with ×40 oil immersion objective, and an Andor Zyla sCMOS digital camera (Andor, South Windsor, CT). Neurons containing Fura-2 were alternatively excited with 340 nm and 380 nm light and fluorescence was monitored at 510 nm. Data points were collected with MetaFluor software (Molecular Devices) at 6 s time points. Ratios of fluorescence intensity were converted to Ca2+ concentrations with a standard curve. Peak calcium responses were quantified, analyzed, and compared statistically. The TRPV1 agonist capsaicin (CAP, 100 nM) was applied to identify the presence of TRPV1, suggestive of a C-fiber afferent phenotype (28).

Whole Cell Patch-Clamp Recordings

Whole cell recordings were performed on dissociated nodose ganglion neurons using an inverted Olympus IX50 microscope and on NTS neurons contained in horizontal brainstem slices using an upright Nikon FN1 microscope. Recording electrodes (2.8–3.8 MΩ) were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) 10 CsCl, 130 Cs-Methanesulfonate, 11 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2ATP, and 0.2 Na2GTP. The intracellular solution was pH 7.4 and 296 mOsm. All neurons were studied under voltage clamp conditions with an Axopatch 200 A or MultiClamp 700 A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA). Neurons were held at VH = −60 mV using pipettes in whole-cell patch configuration. Signals were filtered at 3 kHz and sampled at 30 kHz using p-Clamp software (v. 10, Molecular Devices). Liquid junction potentials were not corrected. Extracellular solution [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)] was continuously perfused and specific drugs were bath applied.

Horizontal Brainstem Slice Preparation

Brainstem slice experiments were performed on rats anesthetized with isoflurane as previously described (29). The medulla was removed from just rostral to the cerebellum to the first cervical vertebrae and placed in ice-cold aCSF containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 dextrose, and 2 CaCl2, bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2. Once chilled and firm, the tissue was trimmed to remove the cerebellum. A wedge was taken from the ventral surface causing the brainstem to sit slightly to the right (or left, if desired) when horizontal and orienting the solitary tract (ST) afferent axons with the NTS in a common plane for cutting. The tissue block was then mounted horizontally to a pedestal with cyanoacrylate glue and submerged in cold (5°C) aCSF on a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1200S). Approximately 300 µm was removed from the dorsal surface and then a single 250-µm thick horizontal slice was collected containing the ST together with the neuronal cell bodies of the medial NTS region. Slices were cut with a sapphire knife (Delaware Diamond Knives, Wilmington, DE) and secured using a fine polyethylene mesh in a perfusion chamber with continuous perfusion of aCSF bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 at 32–33°C and 300 mOsm.

Functional Identification of Second-Order NTS Neurons

To selectively activate ST afferent fibers, a concentric bipolar stimulating electrode (200 µm outer tip diameter; Frederick Haer Co., Bowdoinham, ME) was placed on distal portions of the visible ST rostral to the recording region. Constant current shocks to the ST occurred every 6 s (shock duration 60 µs) using a Master-8 isolated stimulator (A.M.P.I., Jerusalem, Israel). Suprathreshold shocks caused long-latency excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in second-order NTS neurons. These evoked EPSCs result from the action-potential-driven synchronous release of glutamate vesicles, activating postsynaptic α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA) type glutamate receptors in these recording conditions. Latency is the time between the shock artifact and onset of the synchronous EPSC. Synaptic “jitter” is the standard deviation of ST-EPSC latencies for 30 trials. Jitters of <200 µs identify monosynaptic afferent inputs onto the NTS neuron (30). The TRPV1 selective agonist CAP (100 nM) was applied to identify ST afferents possessing TRPV1. Spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) were measured in the absence of tetrodotoxin.

Statistical Analyses

Calcium imaging experiments.

For each experiment, data were collected from 3–4 nodose ganglion cell cultures taken from different animals. Protocols were designed to be within subject and analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by post hoc comparisons against control. Parameters of dose-response relationships (EC50, slope, maximum) were determined by sigmoid fit of the data. For studies involving agonists (PregS), we grouped neurons according to their responsiveness. Neurons identified as responders are those that responded during the drug application, had a >10% change and was resolved following wash. For antagonist studies (ruthenium red, etc.) all neurons received each treatment and were compared using within subject t tests. Data are expressed as the average ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA), with statistically significant differences determined with an α value of (P < 0.05).

Electrophysiological experiments.

Whole cell currents taken from isolated nodose ganglion cells were normalized to the membrane capacitance to control for the large variability in neuron size. Statistical tests for experiments run on isolated neurons are the same as those performed for calcium imaging experiments. For brainstem slice recordings, the digitized waveforms of synaptic events were analyzed using an event detection and analysis program (MiniAnalysis, Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) for all quantal synaptic currents and Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices) for all ST-stimulated currents. All events >10 pA were counted for frequency values. Fitting of quantal EPSC amplitudes and decay kinetics (90%–10%) were performed using a fitting protocol (MiniAnalysis) on >100 discrete events. For statistical comparisons t tests, Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, and linear regression analysis were used when appropriate (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). For group comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Chemicals and Drugs

The chemicals and drugs used for this series of studies were purchased from retail distributors. Specifically, capsaicin, pregnenolone sulfate, mefenamic acid, ruthenium red, and tetrodotoxin (TTX) were sourced from Tocris. Fura-2 AM was purchased from Invitrogen, and the general salts used for making bath solutions were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

RESULTS

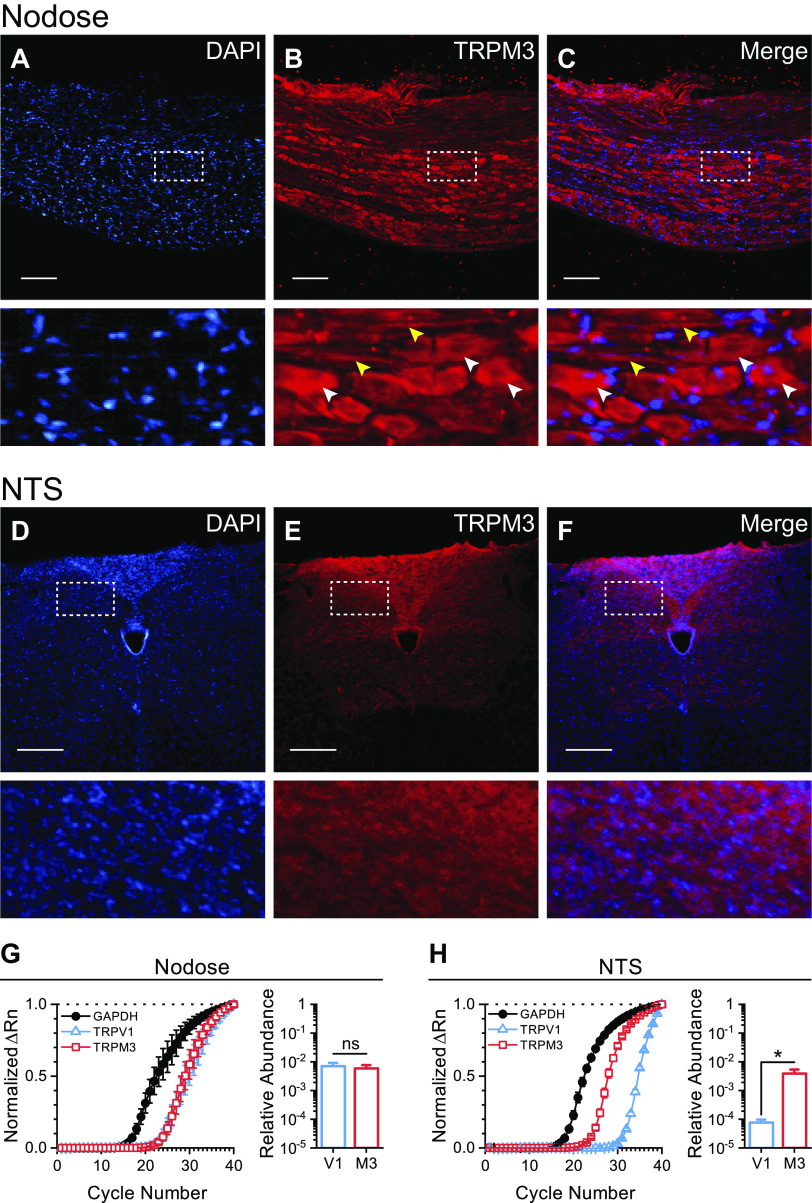

Our initial survey of mRNA and protein analysis suggests that TRPM3 is prominently expressed in nodose ganglion neurons (Fig. 1). We resolved specific staining against TRPM3 in slide mounted rat nodose ganglia and NTS slices with immunohistochemistry. TRPM3 protein is produced in nodose ganglia cell bodies and axons, as indicated by abundant fluorescent staining (Fig. 1, A–C), with only neuropil staining observed in the NTS of the mounted brainstem slices (Fig. 1, D–F). Omission controls suggest selective binding of the secondary antibody with no intrinsic fluorescence of the primary antibody. We used RT-qPCR to confirm the genetic expression of TRPM3 and compare it to the highly expressed TRPV1. TRPM3 mRNA relative abundance was nearly equivalent to that of TRPV1 in the nodose ganglia (Fig. 1G). TRPM3 expression was significantly higher than TRPV1 in the NTS (Fig. 1H). Although there is limited to no correlation between mRNA abundance and protein levels (31), these findings together suggest high expression of both TRPM3 mRNA and protein in the primary afferent neurons of the vagus.

Figure 1.

Vagal afferent neurons abundantly express TRPM3. A–C: top row, photomicrographs of fluorescent immunohistochemical staining, using DAPI nuclear counterstain and a TRPM3 selective antibody in rat nodose ganglion slices. Bottom row, enlarged images indicate high labeling of TRPM3 in both nodose neuron cell bodies (white arrows) and afferent axon fibers (yellow arrows). D–F: top row, photomicrographs of fluorescent immunohistochemical staining, using DAPI nuclear counterstain and a TRPM3 selective antibody in brainstem slice sections, containing the terminations of the vagal afferent neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). Bottom row, enlarged images indicate TRPM3 labeling is primarily contained to the neuropil within the NTS with minimal to no staining on cell bodies. Scale bars represent 200 µm. G and H: quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) amplification curves for GAPDH, TRPV1, and TRPM3 in rat nodose ganglion and NTS normalized to the ΔRn at cycle number 40. Bar graph shows the average ± SE calculated relative abundance (2−ΔCt) of TRPM3 and TRPV1 compared with GAPDH. There was no statistical difference between the relative abundance of TRPM3 and TRPV1 in nodose ganglia (n = 4 rats, P = 0.21, paired t test) (G). TRPM3 mRNA expression was significantly higher that TRPV1 in the NTS (n = 6 rats, *P = 0.03, paired t test) (H).

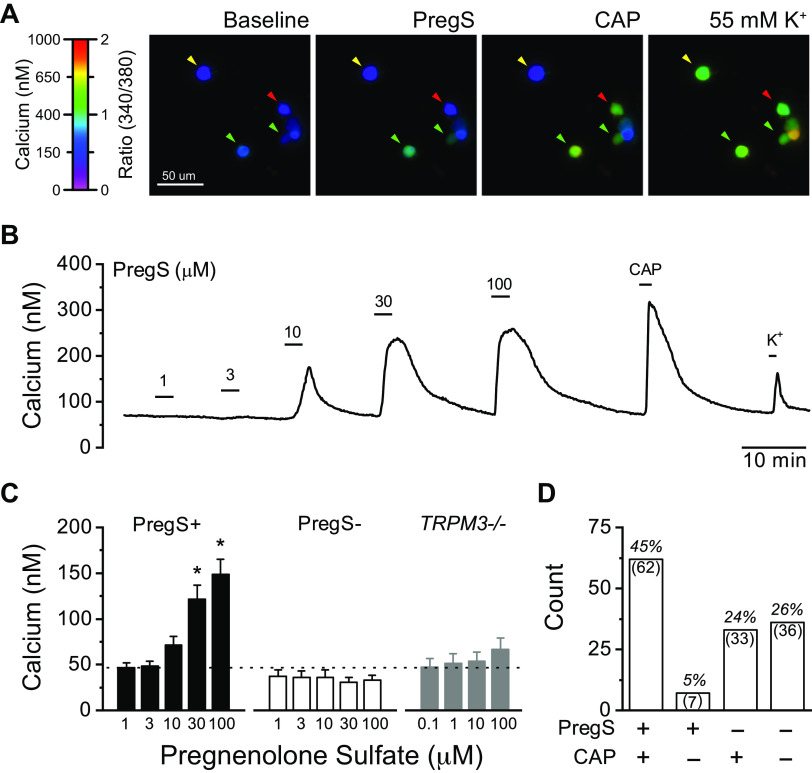

TRPM3 is activated by numerous stimuli, including changes in osmolarity, warm temperatures, and the neurosteroid pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) (32). To pharmacologically assess the presence of TRPM3, we used bath application of PregS, as it is considered the most selective agonist. We determined the functional expression of TRPM3 in cultured rat nodose ganglion neurons using ratiometric fluorescent calcium imaging (Fig. 2). Bath application of PregS produced a rapid increase in cytosolic calcium, which reversed following wash (Fig. 2A). Responses were concentration-dependent and significantly increased by 30 µM PregS in responsive neurons. PregS failed to increase cytosolic calcium at any concentration in nodose neurons taken from TRPM3 KO mice (Fig. 2B). Across all calcium imaging experiments, PregS activated over half of the nodose neurons tested (n = 162 of 264 neurons, 61%). In a subset of neurons, we tested their responsiveness to the TRPV1 agonist CAP (100 nM). The majority of neurons activated by PregS were also activated by CAP (n = 62 of 69 neurons, 90%), suggesting TRPM3 is preferentially expressed in TRPV1-containing neurons typical of C- and Aδ-fiber afferents (Fig. 2C) (22, 33).

Figure 2.

Pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) activates a subset of vagal afferent neurons via TRPM3. A: representative images showing ratiometric fluorescent calcium responses to PregS, capsaicin (CAP), and 55 mM K+. Arrows indicate responsiveness to both PregS and CAP (green), CAP only (red), and nonresponsive neurons (yellow). B: representative calcium trace showing concentration-dependent activation by PregS (1–100 µM) in a CAP responsive neuron. Elevated potassium (K+, 55 mM) was applied to confirm cell viability. C: average calcium responses from dissociated rat nodose ganglia show a significant concentration-dependent increase in intracellular calcium in PregS responsive neurons (PregS+, n = 83 neurons/5 rats, P < 0.001, Friedman’s test), and no change in PregS nonresponsive neurons (PregS−, n = 43 neurons, P = 0.98, RM-ANOVA). Post hoc comparison against control showed statistical differences at 30 and 100 μM PregS (*P < 0.05). Nodose ganglia neurons from TRPM3 KO mice (TRPM3−/−) lacked PregS responses at all concentrations (n = 34 neurons/4 mice, P = 0.39, RM-ANOVA). Dotted line represents average baseline calcium concentration. D: distribution of PregS and CAP responsive and nonresponsive neurons across all experiments where neurons were also exposed to CAP. PregS and CAP responsiveness significantly cosegregated (n = 228 neurons/5 rats, P < 0.001, χ-square).

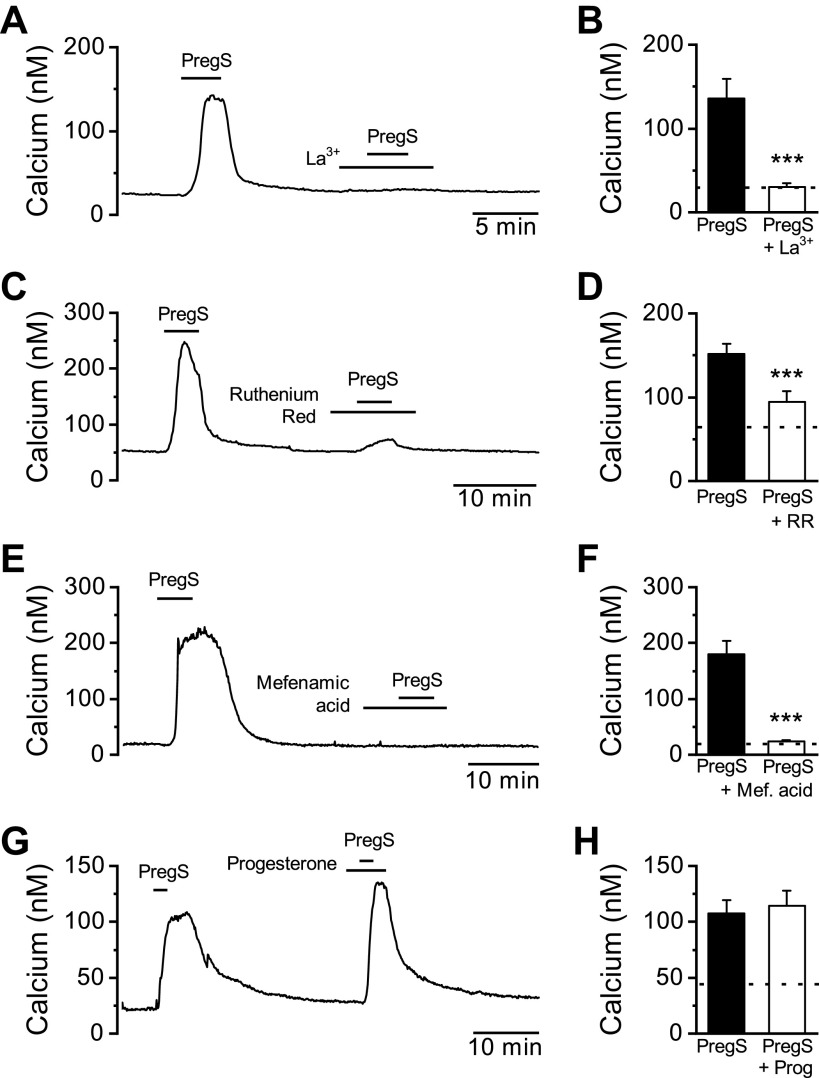

Calcium permeation of TRPM3 can be completely blocked by application of the trivalent metal ion lanthanum (La3+) and attenuated with the charged organic dye ruthenium red (34). PregS-induced calcium responses were eliminated with La3+ pretreatment and significantly reduced with ruthenium red, consistent with TRPM3 activation in the nodose neurons (Fig. 3, A–D). Furthermore, the fenamate class of chemicals, including the clinically used mefenamic acid, are known to inhibit TRPM3 calcium influx (35). We found that pretreatment with mefenamic acid completely prevented subsequent activation by PregS (Fig. 3, E and F), providing further pharmacological evidence of functional TRPM3 signaling in vagal afferent neurons.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological characterization of pregnenolone sulfate (PregS)-induced activation. A representative calcium trace showing PregS-induced (50 µM) increase in cytosolic calcium is eliminated following pretreatment with the channel pore blocker lanthanum (La3+, 100 µM). B: average data for PregS responses before and following La3+ (n = 15 neurons/3 rats, ***P < 0.001, paired t test). C: pretreatment with the broad spectrum TRP channel pore blocker ruthenium red (RR; 1 µM) reduced, but did not eliminate the PregS response. D: average data for PregS activation before and following ruthenium red pretreatment (n = 15 neurons/3 rats, ***P < 0.001, paired t test). E: pretreatment with mefenamic acid (Mef. acid; 50 µM) completely eliminated the response to PregS. F: average data for PregS activation before and following mefenamic acid pretreatment (n = 9 neurons/2 rats, ***P < 0.001, paired t test).

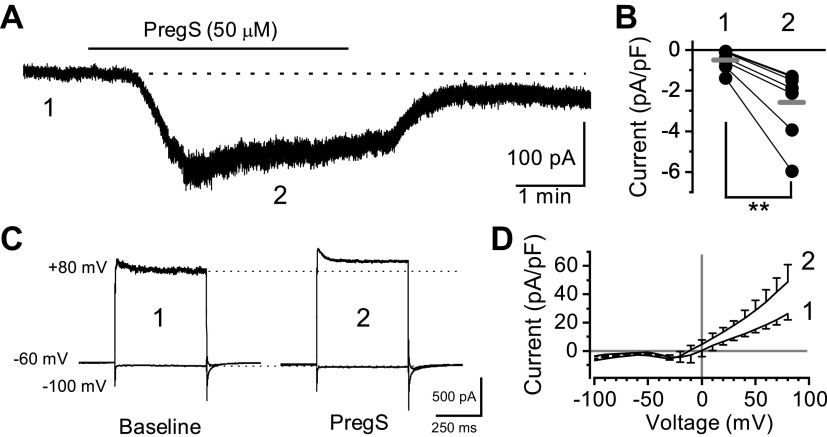

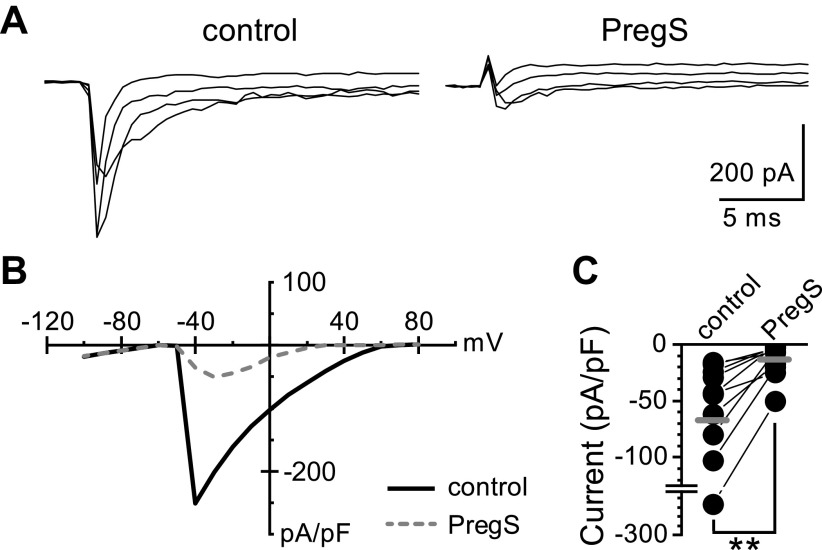

TRPM3 is a nonselective cation channel that produces a strong outwardly rectifying current under physiological bath conditions (22). Using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, we measured PregS-induced macroscopic currents in nodose neurons (Fig. 4). Bath exposure to PregS (50 µM) resulted in a slowly desensitizing inward current in 7 of 10 neurons (70%) held at Vm = −60 mV (Fig. 4, A and B). Voltage steps from −100 mV to +80 mV highlighted an outward PregS-induced current component at positive potentials (Fig. 4, C and D). In all neurons recorded, PregS inhibited the voltage-activated sodium current (Nav) independent of the apparent TRPM3-mediated responses (Fig. 5). Thus, although PregS robustly activates TRPM3, its usefulness in studying action-potential-driven forms of signaling is limited (36).

Figure 4.

Characterization of pregnenolone sulfate (PregS)-induced membrane currents. Data was collected using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology in voltage-clamp configuration. A: PregS (50 µM) produces a large inward current at a negative membrane potential (−60 mV) that reverses following wash. B: individual neuron current responses in control bath (1) and following PregS (2) exposure (n = 7 neurons/3 rats, **P = 0.006, paired t test). Gray bars represent the average responses. Currents have been normalized to cell capacitance to account for differences in cell size. C: resulting current responses from voltage steps in control bath (1) and during PregS (2) exposure. Neurons were held at −60 mV and then stepped from −100 mV to +80 mV by 10 mV increments. Only the maximum inward (−100 mV) and maximum outward (+80 mV) sweeps are shown for clarity. D: average current-voltage response to PregS (2) compared with control (1). PregS produced an outwardly rectifying conductance consistent with activation of TRPM3.

Figure 5.

Pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) inhibits voltage-activated sodium channels independent of TRPM3. A: current changes in response to voltage steps (−100 mV to +80 mV), showing the rapidly inactivating voltage-activated sodium current in control (left) or following PregS (50 µM, right). Only steps from −50 mV to −20 mV are shown for clarity. B: the resulting current-voltage relationship shows a dramatic inhibition of the voltage-activated sodium current in all neurons tested irrespective of PregS-induced changes in holding current. C: maximum voltage-activated sodium currents were significantly reduced by PregS (n = 10 neurons/3 rats, **P = 0.002, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Black circles represent individual neuron responses whereas gray bars represent the average.

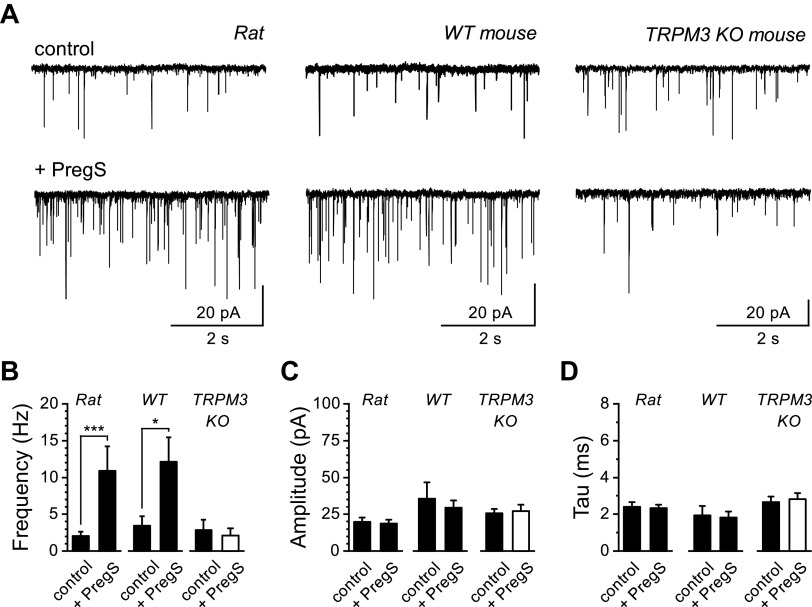

Activation of TRPV1 controls quantal forms of glutamate release, including spontaneous and asynchronous release pathways from vagal afferent central terminals in the NTS (5, 13). We investigated the ability of TRPM3 to also control glutamate release from vagal central terminals by using PregS with patch-clamp electrophysiology of second-order NTS neurons (Fig. 6). We found that PregS significantly increased the frequency of spontaneous glutamate release in rat (n = 12 of 15 neurons/11 rats, 80%) and wild-type mice (n = 6 of 10 neurons/3 mice, 60%; Fig. 6, A and B). This effect was likely mediated presynaptically as there was no statistically significant change in the sEPSC amplitudes and kinetics postsynaptically (Fig. 6, C and D). Consistent with these changes being TRPM3 dependent, bath exposure to PregS in NTS recordings from TRPM3 KO mice failed to produce any change in sEPSC frequency (n = 4 mice; Fig. 6, A–D).

Figure 6.

Pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) increases the frequency of spontaneous glutamate release. Recordings were made from second-order nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) neurons contained in brainstem slice preparations. Neurons were held at −60 mV. A: representative current traces showing spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) during control and following bath exposure to PregS (50 µM). Large increases in sEPSC frequency were seen in rat (left) and wild-type (WT) mouse (middle) neurons but absent from TRPM3 knockout (KO) mouse neurons (right). B: mean sEPSC frequencies in control and during PregS exposure across rats, WT mice, and TRPM3 KO mice. PregS significantly increased sEPSC frequency in rats (n = 12 neurons/11 rats, ***P < 0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and WT mice (n = 7 neurons/3 mice, *P = 0.014, paired t test) but failed to increase frequency in recordings from TRPM3 KO mice (n = 7 neurons/4 mice, P = 0.101, paired t test). Populations of quantal events were analyzed and fit to determine the mean sEPSC amplitude (C) and decay time-constant (τ) in control and during PregS exposure across rat, WT mice, and TRPM3 KO mice (D). PregS did not significantly affect sEPSC amplitude or τ in any condition.

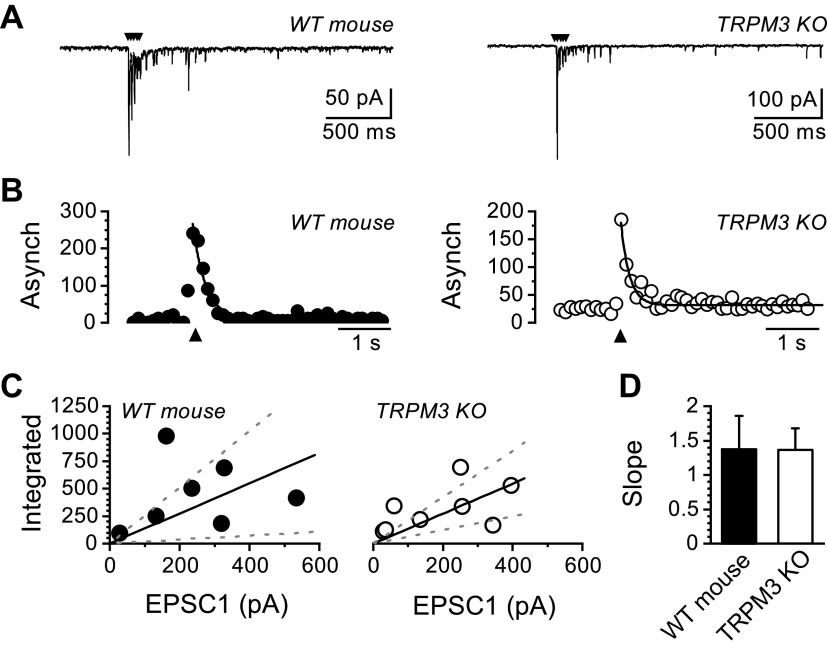

We next assayed the contribution of TRPM3 to action-potential-driven asynchronous glutamate release by comparing recordings from control wild-type mice to TRPM3 KO mice (Fig. 7). Asynchronous release occurs immediately, following a train of action-potential-evoked synchronous EPSCs and was not noticeably different between wild-type and TRPM3 KO mice (Fig. 7A). The magnitude of the asynchronous release processes can be quantified across multiple trials as the peak increase in frequency of quantal events following the synchronous EPSCs (Fig. 7B). In mice, the peak asynchronous release decays as a first-order exponential following the peak (9). The size of asynchronous glutamate release is proportional to that of the evoked synchronous EPSCs (31, 32, 37). To account for the variability in evoked synchronous EPSCs, we plotted the synchronous to asynchronous relationship and fit it with a linear function. The slope of this fit reflects the proportion of asynchronous glutamate release as a function of vesicle release sites and was not significantly different between wild-type and TRPM3 KO mice (Fig. 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

Genetic deletion of TRPM3 does not impact asynchronous glutamate release. Recordings were made from second-order nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) neurons with suprathreshold shocks delivered to the solitary tract (ST) to evoke action-potential-driven synchronous release, followed by asynchronous release. Five shocks occurred at 50 Hz every 6 s. A: representative current traces showing evoked synchronous and asynchronous excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) from wild-type (WT) and TRPM3 knockout (KO) mice. Stimulus artifacts have been removed and are indicated with the black arrows. B: histograms of quantal events plotted across time show a transient increase in frequency immediately following the stimulus train (black arrow) that peaks rapidly and decays with a single exponential function. The asynchronous (Asynch) glutamate release profile was present in both WT and TRPM3 KO synapses. C: scatter-plot showing the integrated area under the curve of asynchronous quantal events as a function of evoked synchronous EPSC amplitude. Data is fit with a best fit linear function (solid line) and standard deviation (dotted lines). Asynchronous release scales with the size of the evoked synchronous release. D: bar graph comparing the slope of the synchronous to asynchronous ratio. There was no significant difference between WT and TRPM3 KO mice (WT: n = 7 neurons/3 mice and TRPM3 KO: n = 8 neurons/3 mice, P = 0.79, unpaired t test).

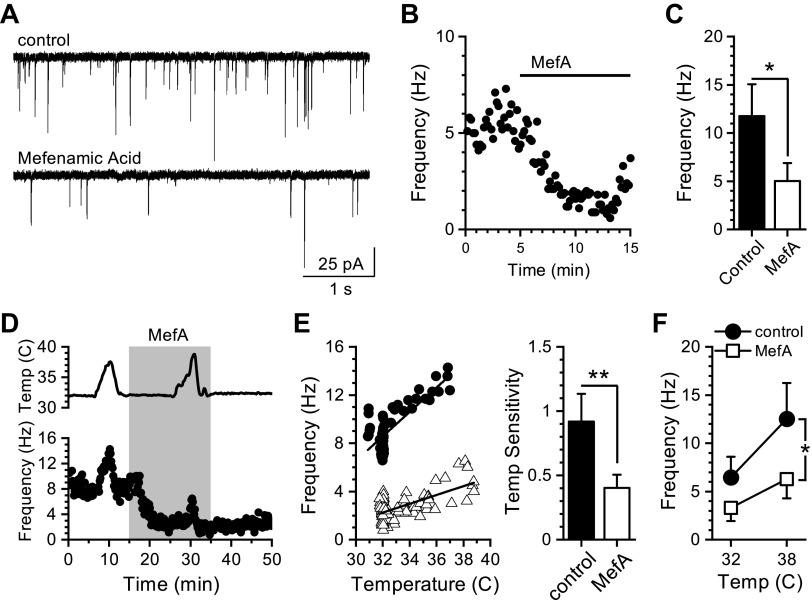

We next determined the contribution of TRPM3 to temperature-driven spontaneous glutamate release from vagal afferent terminals. Blockade of TRPM3 signaling with mefenamic acid (MefA, 50 µM) decreased control and temperature-evoked increases in sEPSC frequency (Fig. 8). At standard recording temperature (32°C), MefA significantly reduced sEPSC frequency in all NTS neurons recorded (Fig. 8, A–C). Increasing bath temperature from 32°C to 38°C produced a large increase in sEPSC frequency, which was significantly reduced in the presence of MefA (Fig. 8D). We calculated the slope of the change in frequency (in Hz) as a function of temperature (in °C) to estimate temperature sensitivity. MefA significantly reduced both the sensitivity of the temperature-driven release (Fig. 8E) and the average frequency across the range of temperatures (Fig. 8F). The amplitudes of sEPSCs were not changed across the range of temperatures or in response to MefA. These results suggest that TRPM3 contributes to constitutive and temperature-driven spontaneous glutamate release similar to TRPV1 (13).

Figure 8.

Mefenamic acid reduces basal and temperature-driven spontaneous glutamate release. Recordings were made from second-order nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) neurons contained in brainstem slice preparations. A: representative current traces showing spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) during control recording at 32°C and after bath application of mefenamic acid (MefA, 50 µM). B: diary plot of a representative experiment showing the effect of MefA on basal sEPSC frequency at 32°C. Each point represents a 10-s bin. C: average sEPSC frequencies in control bath and during MefA exposure (n = 9 neurons/6 rats, *P = 0.02, paired t test). D: plot showing sEPSC frequency over time with temperature (Temp) ramps before and during exposure to MefA. Bath temperature over time is plotted in the top trace. E: left, scatter-plot of the binned sEPSC frequencies from control and MefA treatment from a representative recording plotted as a function of bath temperature. Across frequency data from control and MefA treatment periods were fit with a linear function over the temperature range (control: R2 = 0.57 ± 0.07 and MefA: R2 = 0.42 ± 0.07). Right, average slopes of the linear fits of temperature-dependent changes in frequency across neurons. MefA significantly reduced the slope of the temperature sensitivity (n = 8 neurons/4 rats, **P = 0.008, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). F: plot of the average frequency during control bath temperature (32°C) and following temperature increase (38°C) during control (black circles) and after MefA (open squares). There is a significant interaction between MefA treatment and temperature on sEPSC frequency (n = 8 neurons/4 rats, *P = 0.018, two-way RM-ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

These studies collectively demonstrate the functional expression of the TRPM3 ion channel in primary vagal afferent neurons. Here we show that TRPM3 coexpressed with TRPV1 on vagal afferent cell bodies and mediated calcium influx. In the brain TRPM3 contributed to both basal and temperature-dependent changes in spontaneous glutamate release at synaptic terminals in the NTS. This broad distribution of TRPM3 throughout the afferent neuron is similar to TRPV1 and suggests the possibility of different signaling roles depending on its cellular localization. The unique features of TRPM3 to respond to various stimuli, including steroids and physiological temperatures, positions it as a key point of control over vagal signaling and neurotransmission in the NTS. Given its abundance and large signaling profile, we predict it will meaningfully impact vagally mediated reflex pathways and behaviors.

Consistent with a presynaptic localization of TRPM3, we report immunohistochemical and functional TRPM3 signaling in the majority of nodose neurons along with abundant mRNA amplification from isolated nodose ganglia (Figs. 1 and 2). TRP channel pharmacology is complicated by the general lack of selective agonists and antagonists. With few exceptions, identification of native TRP channel signaling is accomplished by convergent positive and negative forms of evidence ruling in, or out, TRP channels based off their constellation of traits. The steroid agonist PregS is known to be a strong agonist at TRPM3; however, endogenous effects of PregS at TRPM3 have not been demonstrated. In addition to TRPM3, PregS has effects on several targets involved in neuronal signaling, including GABAA receptors, NMDA receptors, TRPM1, and TRPM3 (38). Although these alternative targets are present to varying degrees in vagal afferent neurons, we are confident that the majority of the PregS-induced calcium influx was mediated by TRPM3 due to the reduction by RuR, blockade by La3+ and mefenamic acid, and absence in the TRPM3 KO mice (Figs. 2 and 3). This was confirmed again with the NTS recordings, when PregS failed to alter spontaneous frequency in the TRPM3 KO mice (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the PregS-induced changes in whole-cell current were consistent with previous publication studying TRPM3 channels in isolation (Fig. 4) (22).

It is common to use both rat and mice animal models to investigate vagal afferent neurophysiology and TRP channel signaling. Although broadly similar, there are important differences to note. Specifically, mouse TRPV1 is less sensitive to capsaicin activation (39) and the rate of spontaneous glutamate release is markedly slower than in rats, both parameters relevant to the current study. The extent to which TRPM3 differs between rats and mice has not been systematically characterized but should be considered an important possibility. In these current studies, we did not detect any notable differences in putative TRPM3 signaling between rat and mouse vagal afferents or NTS neurons.

We next investigated the role of TRPM3 in controlling synaptic glutamate release onto recorded NTS neurons. The release of glutamate from vagal afferent terminals occurs via evoked, action-potential-synchronized release as well as quantal release asynchronously and spontaneously (4). TRP channel activation potentiates the quantal forms of release, including temperature-evoked changes in spontaneous vesicle fusion (5, 40). We found that manipulation of TRPM3 signaling selectively impacted spontaneous neurotransmission similar to TRPV1 (Fig. 6) (40). Activation with PregS produced a rapid increase in the frequency of spontaneous release with no significant changes in the postsynaptic EPSC waveforms or holding current, consistent with a presynaptic site of action. This effect was also present in recordings from wild-type mice but absent in TRPM3 KO animals, confirming the necessity of TRPM3 in mediating the excitatory effects of PregS. Somewhat surprisingly, documentation of TRPM3 signaling in the brain to control glutamate release has been reported only once previously in the cerebellar cortex during early developmental stages (41). Here, we extend the role of TRPM3 and report its signaling in fully adult animals.

Due to the ongoing constitutive nature of spontaneous glutamate release, this form of synaptic transmission conveys a large portion of the charge transfer at NTS synapses (42). Release frequency is extremely dynamic, in which it can either be inhibited or augmented, and spans several orders of magnitude (0.1–50 Hz). In contrast, evoked synchronous release is nearly maximal and is generally modulated to a lesser extent. Thus, TRPM3 coupling to quantal forms of release amplifies its impact on synaptic transmission, both as a function of total charge transfer and across a relatively long time scale. By extension we predict that endogenous signals which change TRPM3 gating have a strong point of leverage over neurotransmission and synaptic throughput.

In addition to the TRPM3 in the primary afferents, we also report amplification of TRPM3 mRNA from NTS tissue at a much higher level than TRPV1 (Fig. 1). This suggests that TRPM3 may reside within cells types of the NTS in addition to the afferents and contribute to signaling. Although we did not observe PregS produce direct currents in recorded NTS neurons, this does not rule out the possibility of glial expression or small, highly calcium selective, signaling in the neurons that would have been difficult to resolve. If true, this would be an exciting possibility given the very limited distribution of TRPM3 in the brain.

Physiological changes in temperature due to circadian rhythms, changes in metabolism, feeding, or febrile responses to infection are monitored by the brain and represent an important signal to alter information processing, including autonomic reflex function (43). However, the mechanisms through which temperature impacts neurophysiological processes in many brain areas, including the NTS, are not well characterized. Previously, we identified that spontaneous glutamate release from TRPV1 containing vagal afferents is highly temperature sensitive and requires calcium influx via thermosensitive TRP channels, including TRPV1 itself (13). However, the temperature threshold for TRPV1 gating is well above the physiological range (>40°C) and seemed unlikely to solely account for the temperature-driven release at physiological temperatures. Pharmacological or genetic deletion of TRPV1 did not fully remove temperature sensitivity, suggesting additional thermosensitive mechanisms consistent with a redundant system of temperature monitoring (4, 9). Only a handful of TRP channels are temperature gated in this range, including TRPV3, TRPV4, and TRPM3 (44). Although there appears to be some expression of TRPV3 in a handful of vagal afferents, it does not seem to be a prominent thermosensitive ion channel for vagal afferent signaling (45). Similarly, TRPV4 expression is very low (46). The abundant expression of TRPM3 in nodose ganglia suggested that it contributes to temperature-driven spontaneous glutamate release.

Here, we report that TRPM3 controls temperature-driven spontaneous release in the physiological temperature range (Fig. 8). Previous reports have demonstrated that TRPM3 contributes to temperature sensing in primary somatosensory afferents (47). We expand on those findings and demonstrate that TRPM3 also signals at the central terminals and conveys temperature sensing in the physiological temperature range that is sensitive enough to detect even small changes in temperature that occur in the brain (48). Bath application of mefenamic acid rapidly inhibited the frequency of spontaneous release at normal recording temperature and significantly reduced the gain of the temperature-evoked increases in release. This temperature sensitivity coupled with the responsiveness to steroids, position TRPM3 to integrate various inputs and control synaptic transmission (47). Given that body temperature fluctuates as a function of time of day, following feeding, and in response to systemic infection, the presence of the warm-sensitive TRPM3 provides a plausible point of control to translate changes in temperature to neurophysiological signaling of the vagus. Moving forward, work characterizing the role of TRPM3 in vagally mediated physiological responses to temperature and other stimuli will prove particularly important and interesting.

Evidence suggests that synaptic TRP channels can selectively target different vesicle release pathways (7). In the NTS, activation of TRPV1 has been shown to dramatically increase action-potential-independent spontaneous glutamate release, contribute to action-potential-driven asynchronous release, but inhibit action-potential-dependent synchronous release (5, 40). This suggests some degree of specificity in the vesicle pools targeted by TRP-mediated calcium influx. PregS is quite effective at inhibiting voltage-activated sodium channels, thus complicating the study of action-potential-evoked release pathways. Here, we found that genetic deletion of TRPM3 did not significantly impact either the synchronous or asynchronous vesicle release pathways. This suggests that TRPM3 may not be essential in these vesicle release pathways. In this model, TRPM3 calcium influx would be predicted to localize to subcellular domains targeting vesicles “specified” for spontaneous release and not synchronous and asynchronous release pathways (7, 49). Some evidence exists supporting this functional dissection of calcium influx pathways and vesicle pools, although a consensus across excitatory neuron subtypes does not exist.

Alternatively, germline deletion of TRPM3 may result in compensatory expression of other similar TRP channels to maintain its role as seen in other thermosensitive afferents (15). Our previous work with TRPV1 genetic-knockout mice suggested that additional TRP channels could “stand-in,” when TRPV1 was absent, and largely maintain TRP-driven vesicle release. Similar to the TRPV1-knockout animals, genetic deletion of TRPM3 did not produce significant changes in any form of glutamate release, including basal spontaneous frequency (Figs. 6 and 7). The clearest difference was the lack of responsiveness to PregS with the loss of TRPM3. Thus, although the TRPM3 KO was useful in confirming that PregS-induced activation was a function of TRPM3 expression, it may serve to underreport the cellular effects of TRPM3 signaling in the native condition. This remains intriguing and consistent with the possibility of redundant TRP channel expression and function (15).

Activation of thermosensitive TRP channels in somatosensory neurons is clear and contributes meaningfully to thermosensation in vitro. However, the utility of their expression in primary vagal afferent neurons is only beginning to be well understood (43). In addition to being able to detect physiological changes in internal temperature, they may also serve to transduce G protein-coupled receptor signaling activated by circulating hormones or translate direct steroid signaling into rapid changes in neurotransmission (50). Thus, the multimodal activation profile of TRPM3 positions it as an important integrator of physiological signals with strong influence over NTS signaling, and we predict autonomic function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK092651 (to J. H. Peters).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.P.R. and J.H.P. conceived and designed research; F.J.R., R.A.A., A.J.F., T.P.R., J.E.M.L., B.P., and J.H.P. performed experiments; F.J.R., R.A.A., A.J.F., T.P.R., J.E.M.L., B.P., and J.H.P. analyzed data; F.J.R., R.A.A., A.J.F., T.P.R., B.P., and J.H.P. interpreted results of experiments; F.J.R. and J.H.P. prepared figures; F.J.R. and J.H.P. drafted manuscript; F.J.R., R.A.A., A.J.F., T.P.R., J.E.M.L., B.P., and J.H.P. edited and revised manuscript; F.J.R., R.A.A., A.J.F., T.P.R., J.E.M.L., B.P., and J.H.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Lane Brown for providing the TRPM3 KO mice. We also thank Dallas Kinch, Shu Yi Qi, and Andrea Hafar for contributing to the data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Browning KN, Verheijden S, Boeckxstaens GE. The vagus nerve in appetite regulation, mood and intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 152: 730–744, 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loewy AD, Spyer KM. Central Regulation of Autonomic Functions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saper CB. The central autonomic nervous system: conscious visceral perception and autonomic pattern generation. Annu Rev Neurosci 25: 433–469, 2002. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.032502.111311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu S-W, Fenwick AJ, Peters JH. Channeling satiation: a primer on the role of TRP channels in the control of glutamate release from vagal afferent neurons. Physiol Behav 136: 179–184, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Primary afferent activation of thermosensitive TRPV1 triggers asynchronous glutamate release at central neurons. Neuron 65: 657–669, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fawley JA, Hofmann ME, Andresen MC. Cannabinoid 1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptors discretely modulate evoked glutamate separately from spontaneous glutamate transmission. J Neurosci 34: 8324–8332, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0315-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fawley JA, Hofmann ME, Andresen MC. Distinct calcium sources support multiple modes of synaptic release from cranial sensory afferents. J Neurosci 36: 8957–8966, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1028-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawley JA, Hofmann ME, Largent-Milnes TM, Andresen MC. Temperature differentially facilitates spontaneous but not evoked glutamate release from cranial visceral primary afferents. PLoS One 10: e0127764, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenwick AJ, Wu S-W, Peters JH. Isolation of TRPV1 independent mechanisms of spontaneous and asynchronous glutamate release at primary afferent to NTS synapses. Front Neurosci 8, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stacey SM, Muraro NI, Peco E, Labbe A, Thomas GB, Baines RA, van Meyel DJ. Drosophila glial glutamate transporter Eaat1 is regulated by fringe-mediated notch signaling and is essential for larval locomotion. J Neurosci 30: 14446–14457, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1021-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sousa-Valente J, Andreou AP, Urban L, Nagy I. Transient receptor potential ion channels in primary sensory neurons as targets for novel analgesics. Br J Pharmacol 171: 2508–2527, 2014. doi: 10.1111/bph.12532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzone SB, Undem BJ. Vagal afferent innervation of the airways in health and disease. Physiol Rev 96: 975–1024, 2016. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoudai K, Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Andresen MC. Thermally active TRPV1 tonically drives central spontaneous glutamate release. J Neurosci 30: 14470–14475, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan C-H, McNaughton PA. TRPM2 and warmth sensation. Pflugers Arch 470: 787–798, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00424-018-2139-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vandewauw I, De Clercq K, Mulier M, Held K, Pinto S, Van Ranst N, Segal A, Voet T, Vennekens R, Zimmermann K, Vriens J, Voets T. A TRP channel trio mediates acute noxious heat sensing. Nature 555: 662–666, 2018. [Erratum in Nature 559: E7, 2018]. doi: 10.1038/nature26137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vay L, Gu C, McNaughton PA. The thermo-TRP ion channel family: properties and therapeutic implications. Br J Pharmacol 165: 787–801, 2012.doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries J, Strubbe JH, Wildering WC, Gorter JA, Prins AJA. Patterns of body temperature during feeding in rats under varying ambient temperatures. Physiol Behav 53: 229–235, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90198-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison SF. Central control of body temperature. F1000Res 5: F1000 Faculty Rev-880, 2016. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7958.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Refinetti R, Menaker M. The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Physiol Behav 51: 613–637, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Held K, Voets T, Vriens J. TRPM3 in temperature sensing and beyond. Temperature (Austin) 2: 201–213, 2015. doi: 10.4161/23328940.2014.988524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberwinkler J, Lis A, Giehl KM, Flockerzi V, Philipp SE. Alternative splicing switches the divalent cation selectivity of TRPM3 channels. J Biol Chem 280: 22540–22548, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vriens J, Owsianik G, Hofmann T, Philipp SE, Stab J, Chen X, Benoit M, Xue F, Janssens A, Kerselaers S, Oberwinkler J, Vennekens R, Gudermann T, Nilius B, Voets T. TRPM3 is a nociceptor channel involved in the detection of noxious heat. Neuron 70: 482–494, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner TFJ, Loch S, Lambert S, Straub I, Mannebach S, Mathar I, Düfer M, Lis A, Flockerzi V, Philipp SE, Oberwinkler J. Transient receptor potential M3 channels are ionotropic steroid receptors in pancreatic beta cells. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1421–1430, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ncb1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yajima T, Sato T, Shimazaki K, Ichikawa H. Transient receptor potential melastatin-3 in the rat sensory ganglia of the trigeminal, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. J Chem Neuroanat 96: 116–125, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonvini S, Arshad M, Wortley MA, Adcock JJ, Dubuis E, Kosmidou K, Maher SA, Shala F, Vriens J, Voets T, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG. TRPM3: a regulator of airway sensory nerves and respiratory reflexes. Eur Resp J 48: PA5070, 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2016.PA5070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lancaster E, Weinreich D. Sodium currents in vagotomized primary afferent neurones of the rat. J Physiol 536: 445–458, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0445c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simasko SM, Wiens J, Karpiel A, Covasa A, Ritter RC. Cholecystokinin increases cytosolic calcium in a subpopulation of cultured vagal afferent neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R1303–R1313, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00050.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holzer P. TRPV1 and the gut: from a tasty receptor for a painful vanilloid to a key player in hyperalgesia. Eur J Pharmacol 500: 231–241, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doyle MW, Bailey TW, Jin Y-H, Appleyard SM, Low MJ, Andresen MC. Strategies for cellular identification in nucleus tractus solitarius slices. J Neurosci Methods 137: 37–48, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle MW, Andresen MC. Reliability of monosynaptic sensory transmission in brain stem neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 85: 2213–2223, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meissner M, Obmann VC, Hoschke M, Link S, Jung M, Held G, Philipp Se Zimmermann R, Flockerzi V. Chapter 6. Lessons of studying TRP channels with antibodies [Online]. In: TRP Channels, edited by Zhu MX. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92823/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiel G, Rubil S, Lesch A, Guethlein LA, Rössler OG. Transient receptor potential TRPM3 channels: pharmacology, signaling, and biological functions. Pharmacol Res 124: 92–99, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen Ho L, Tran Van N, Le Thuong V, Hoang Chan P, Kantrow SP, Duong Duy K, Smith DL. Hilar asymmetry in endobronchial tuberculosis patients: an often-overlooked clue. Int J Infect Dis 80: 80–83, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimm C, Kraft R, Sauerbruch S, Schultz G, Harteneck C. Molecular and functional characterization of the melastatin-related cation channel TRPM3. J Biol Chem 278: 21493–21501, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klose C, Straub I, Riehle M, Ranta F, Krautwurst D, Ullrich S, Meyerhof W, Harteneck C. Fenamates as TRP channel blockers: mefenamic acid selectively blocks TRPM3. Br J Pharmacol 162: 1757–1769, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horishita T, Ueno S, Yanagihara N, Sudo Y, Uezono Y, Okura D, Sata T. Inhibition by pregnenolone sulphate, a metabolite of the neurosteroid pregnenolone, of voltage-gated sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Sci 120: 54–58, 2012. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12106SC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Andresen MC. TRPV1 marks synaptic segregation of multiple convergent afferents at the rat medial solitary tract nucleus. PLoS One 6: e25015, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harteneck C. Pregnenolone sulfate: from steroid metabolite to TRP channel ligand. Molecules 18: 12012–12028, 2013. doi: 10.3390/molecules181012012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinch DC, Peters JH, Simasko SM. Comparative pharmacology of cholecystokinin induced activation of cultured vagal afferent neurons from rats and mice. PLoS One 7: e34755, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doyle MW, Bailey TW, Jin Y-H, Andresen MC. Vanilloid receptors presynaptically modulate cranial visceral afferent synaptic transmission in nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurosci 22: 8222–8229, 2002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamudio-Bulcock PA, Everett J, Harteneck C, Valenzuela CF. Activation of steroid-sensitive TRPM3 channels potentiates glutamatergic transmission at cerebellar Purkinje neurons from developing rats. J Neurochem 119: 474–485, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kavalali ET. The mechanisms and functions of spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Nat Rev Neurosci 16: 5–16, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nrn3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang RB. Body thermal responses and the vagus nerve. Neurosci Lett 698: 209–216, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Señarís R, Ordás P, Reimúndez A, Viana F. Mammalian cold TRP channels: impact on thermoregulation and energy homeostasis. Pflugers Arch 470: 761–777, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00424-018-2145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu S-W, Lindberg JEM, Peters JH. Genetic and pharmacological evidence for low-abundance TRPV3 expression in primary vagal afferent neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R794–R805, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00366.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang L, Jones S, Brody K, Costa M, Brookes SJH. Thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels in vagal afferent neurons of the mouse. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G983–G991, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00441.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vriens J, Voets T. Sensing the heat with TRPM3. Pflugers Arch 470: 799–807, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-2100-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison SF, Nakamura K. Central mechanisms for thermoregulation. Annu Rev Physiol 81: 285–308, 2019. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chanaday NL, Kavalali ET. Presynaptic origins of distinct modes of neurotransmitter release. Curr Opin Neurobiol 51: 119–126, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberwinkler J, Philipp SE. TRPM3. Handb Exp Pharmacol 222: 427–459, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]