Sometimes you get exactly what you ask for. The recent report of the Canadian Senate's subcommittee of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology entitled Quality End-of-Life Care: The Right of Every Canadian1 would appear to be a case in point. Witness after witness advised the Senate that little progress has been made in the area of quality end-of-life care since their first report, Of Life and Death,2 was released in 1995. They were told that Canadians are still dying in needless pain and without adequate palliative care, that end-of-life care research receives inadequate support and that a comprehensive, national palliative care strategy needs to be developed.3 It appears that the senators were listening. Not only does their report address each of these issues, but it also provides a template that could shape palliative care in Canada for years to come.

The Senate is often charged with tasks that are deemed too controversial or contentious for the government to tackle directly. Prior to the establishment of the Special Senate Committee on Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide, Sue Rodriguez, a 42-year-old woman with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, had submitted to the Supreme Court of Canada that the law against assisted suicide was in contravention of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, primarily on the grounds that section 15 of the charter provides for equal treatment under the law for people with physical disabilities.4 In the wake of the Supreme Court's slim majority decision, upholding the prohibition against assisted suicide, the Senate was asked to examine the legal, social and ethical aspects of euthanasia and assisted suicide in what was undoubtedly the broadest and most thorough review of this issue ever conducted in Canada. Their most recent deliberations primarily examined the developments since the tabling of their initial report and provide a rather grim status report on the state of end-of-life care in Canada.

Irrespective of our response to the Senate report, the number of Canadians dying each year will continue to rise. Over 220 000 Canadians die annually, with 75% dying in hospitals and long-term care facilities.5 The Senate was told that only an estimated 5% of dying Canadians will receive integrated interdisciplinary palliative care, that is, care aimed at alleviating physical, emotional, psychosocial and spiritual suffering rather than care that aims for a cure.6,7 They were further informed that, since their last report, the number of institutional palliative care beds across the country has been cut as result of health care restructuring, and few provinces have designated palliative care as a core service with a specific budget.3 Thus, while the need for end-of-life care has never been greater, the resources available to provide this care are in some respects diminishing.

In view of death's prominence, with the mortality rate in this country remaining at one per person, clinicians need to ask themselves a number of questions. How skilled am I at providing end-of-life care for my patients and their families? How well versed am I in the area of palliative symptom management and the broad range of pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches now available? Is attending to a dying patient something I rarely do? Do I approach a dying patient with a sense of reluctance or therapeutic failure? The answer to these questions in part depends on one's type of practice, where and when one trained and to what extent one views “noncurative” interventions as falling within the domain of good medical care. The Senate report indicates that there is no consistency in whether undergraduate medical students receive any palliative care education, and that few postgraduate medical programs have mandatory palliative care rotations. As for continuing education in palliative care, there are some programs, but the decision to enrol in them is at the discretion of individual practitioners. Perhaps for any physician whose patients are mortal, the argument could be made that some continuing medical education in end-of-life care should be considered mandatory.

Those of us working in palliative care know that the successful management of a dying patient is measured not in days of life endured but, rather, in quality of life lived. Quality of life concerns also extend to families, many of whom shoulder the major portion of terminal care and make tremendous physical, emotional and even financial sacrifices in the service of attending to their loved ones.8 As a psychiatrist working in this area, I am occasionally asked by insurance companies if someone's absence from work is due to a mental disorder or, rather, simply to enable them to nurse a dying loved one. At times, diagnostic accuracy seems at odds with compassion. Fortunately, the Senate has recommended that the federal government implement income security and job protection for family members who care for the dying, along with access to community day programs, 24-hour pain and symptom management teams, respite care and bereavement follow-up.

The Senate also took note of the disturbing lack of research in Canada that addresses end-of-life care.3,9 Since the release of the Senate's 1995 report,2 many of Canada's top palliative care researchers have left the country and support for research into end-of-life care remains woefully inadequate.3 The current report strongly recommends that resources be designated to bolster research that focuses on end-of-life issues facing Canadians of all ages, with all medical conditions. Although this may require a shifting of resources, to invoke the words of the chair of the Senate subcommittee, Senator Carstairs, “As Canadians, we will afford what we value.” Sadly, despite the value of the Senate's work, good reports and bad reports are equally capable of gathering dust. Each of us in health care must take on the responsibility to ensure that this does not happen. Might I suggest the following?

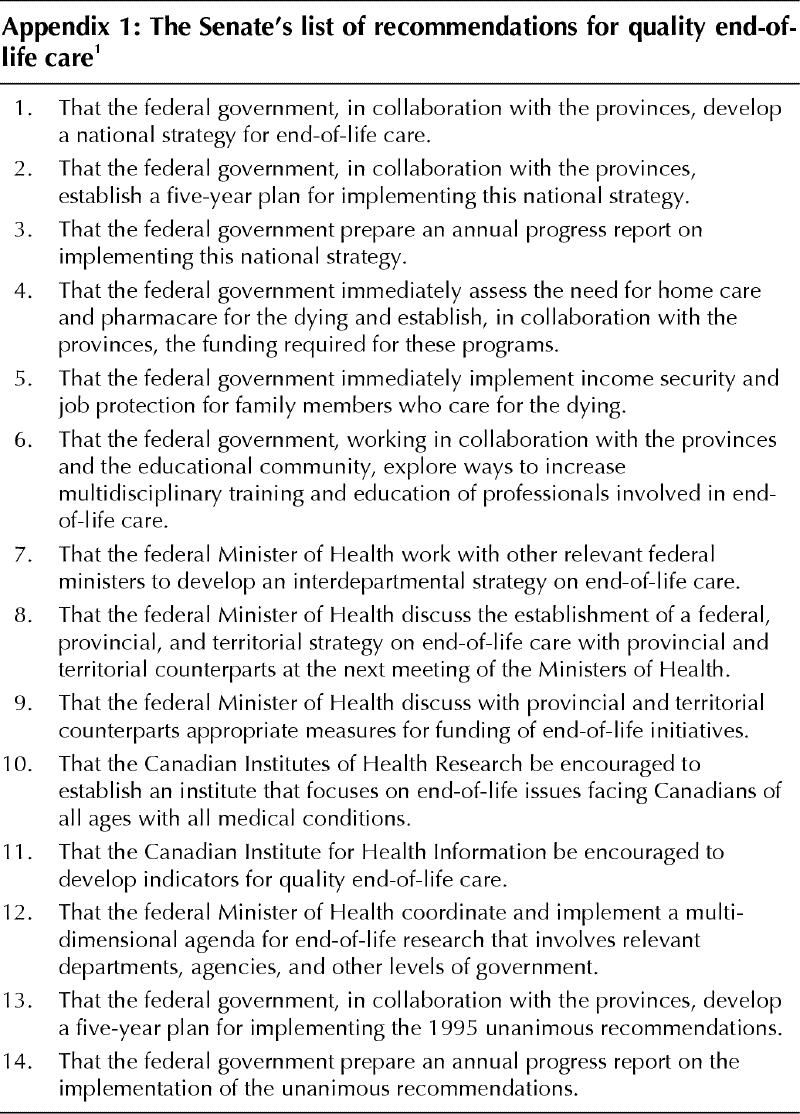

· Affix a copy of the Senate's recommendations for quality end-of-life care (Appendix 1) to your bulletin board as a reminder to spend a minimum of one day each year engaged in continuing medical education activities targeted at symptom management and end-of-life care.

· Send a copy of the Senate recommendations to your hospital or institutional administrator and ask what is being done to support quality end-of-life care for patients within your facility.

· Send a copy of the Senate recommendations to your Member of the Legislative Assembly and ask her or him to support community programs that target quality end-of-life care.

· Send a copy of the Senate's recommendation to your Member of Parliament and ask him or her to do everything in his or her power to see to it that these recommendations are quickly implemented by the federal government.

The Senate report has delivered all we could have hoped for to advance a national palliative care agenda. The ball is now clearly in our court.

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Harvey Max Chochinov, Rm. PX246, 771 Bannatyne Ave., Winnipeg MB R3E 3N4; fax 204 787-4879; chochin@cc.umanitoba.ca

References

- 1.Subcommittee of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Quality end-of-life care: the right of every Canadian. Ottawa: The Senate of Canada; 2000. Available: www.parl.gc.ca/36/2/parlbus/commbus/senate/Com-e/upda-e/rep-e/repfinjun00-e.htm (accessed 2001 Feb 9).

- 2.Special Senate Committee on Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Of life and death – final report. Ottawa: The Senate of Canada; 1995.

- 3.National Research Advisory Committee of the Canadian Palliative Care Association. Canadian agenda for research in palliative care. Ottawa: The Association; 1999. Available: www.cpca.net/research.htm (accessed 2001 Feb 9).

- 4.Chochinov HM, Wilson KG. The euthanasia debate: attitudes, practices and psychiatric considerations. Can J Psychiatry 1995;40:593-602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Perreault J. Population projections for Canada, provincial and territories 1989-2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 1990.

- 6.Latimer EJ, McGregor J. Euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide and the ethical care of dying patients. CMAJ 1994;151(8):1133-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients' perspectives. JAMA 1999;13;281:163-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kristjanson LJ, Leis A, Koop PM, Carriere KC, Mueller B. Family members' care expectations, care perceptions, and satisfaction with advanced cancer care: results of a multi-site pilot study. J Palliat Care 1997;13:5-13. [PubMed]

- 9.MacDonald N. Research — a neglected area of palliative care. J Palliat Care 1992:8:54-8. [PubMed]