Abstract

Introduction:

In the retina, noncoding RNA (ncRNA) plays an integral role in regulating apoptosis, inflammatory responses, visual perception, and photo-transduction, with altered levels reported in diseased states.

Areas covered

MicroRNA (miRNA), a class of ncRNA, regulates post-transcription gene expression through the binding of complementary binding sites of target messenger RNA (mRNA) with resulting translational repression. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) are double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) that regulate gene expression, leading to selective silencing of genes through a process called RNA interference (RNAi). Another form of RNAi involves short hairpin RNA (shRNA). In age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and in diabetic retinopathy (DR), miRNA has been implicated in the regulation of angiogenesis, oxidative stress, immune response, and inflammation.

Expert opinion

Many RNA-based therapies in development are conveniently administered intravitreally, with potential for panretinal effect. The majority of these RNA therapeutics are synthetic ncRNA’s and hold promise for the treatment of AMD, DR and inherited retinal diseases (IRDs). These RNA-based therapies include siRNA therapy with its high specificity, shRNA to “knock down” autosomal dominant toxic gain of function mutated genes, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), which can restore splicing defects, and translational read-through inducing drugs (TRIDS) to increase expression of full-length protein from genes with premature stop codons.

Keywords: Antisense oligonucleotides, inherited retinal disease, microRNA, noncoding RNA, RNA therapeutics, short hairpin RNA, small interfering RNA, translational read-through inducing drugs

Introduction:

Gene therapy has emerged as a potentially viable treatment strategy for many conditions, especially as our understanding of human genomics continues to expand. Therapeutically, DNA, and messenger RNA (mRNA) are promising targets as precursors of proteins, with the potential to alter the structure and function of resulting proteins to address genetic disease. RNA therapeutics have garnered significant interest following approval to treat systemic disorders such as spinal muscular atrophy (nusinersen/Spinraza; Biogen) and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (eteplirsen/Exondys 51 and golodirsen/Vynondys 53; Sarepta).[1–3] Additionally, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines are in development with potential for the development of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in early clinical trials.[4]

Historically, the retina has played an important role in RNA therapy development, with the first approval for an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) in 1998 for intravitreal treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis (fomivirsen/Vitravene; Isis Pharmaceuticals).[5] Inherited retinal dystrophies are one such category of diseases that have shown significant advancement in treatment strategies, namely following FDA approval of the first gene therapy for a genetic disease in 2017 (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl/LUXTURNA, Spark Therapeutic).[6] This review will provide an overview of the current principles and development of RNA therapeutics for retinal diseases.

1. Background:

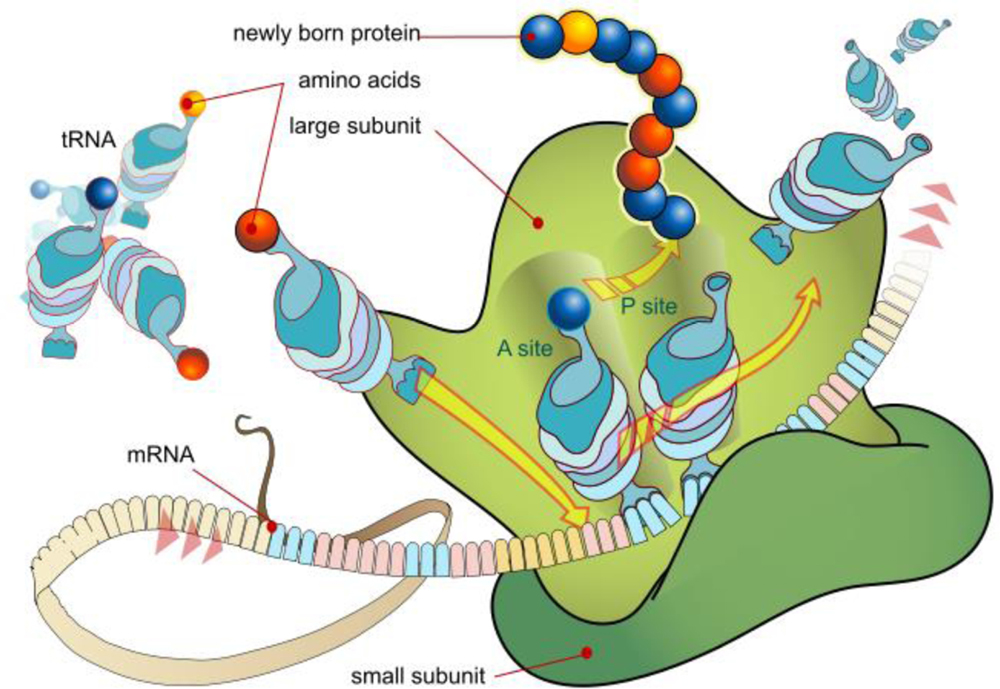

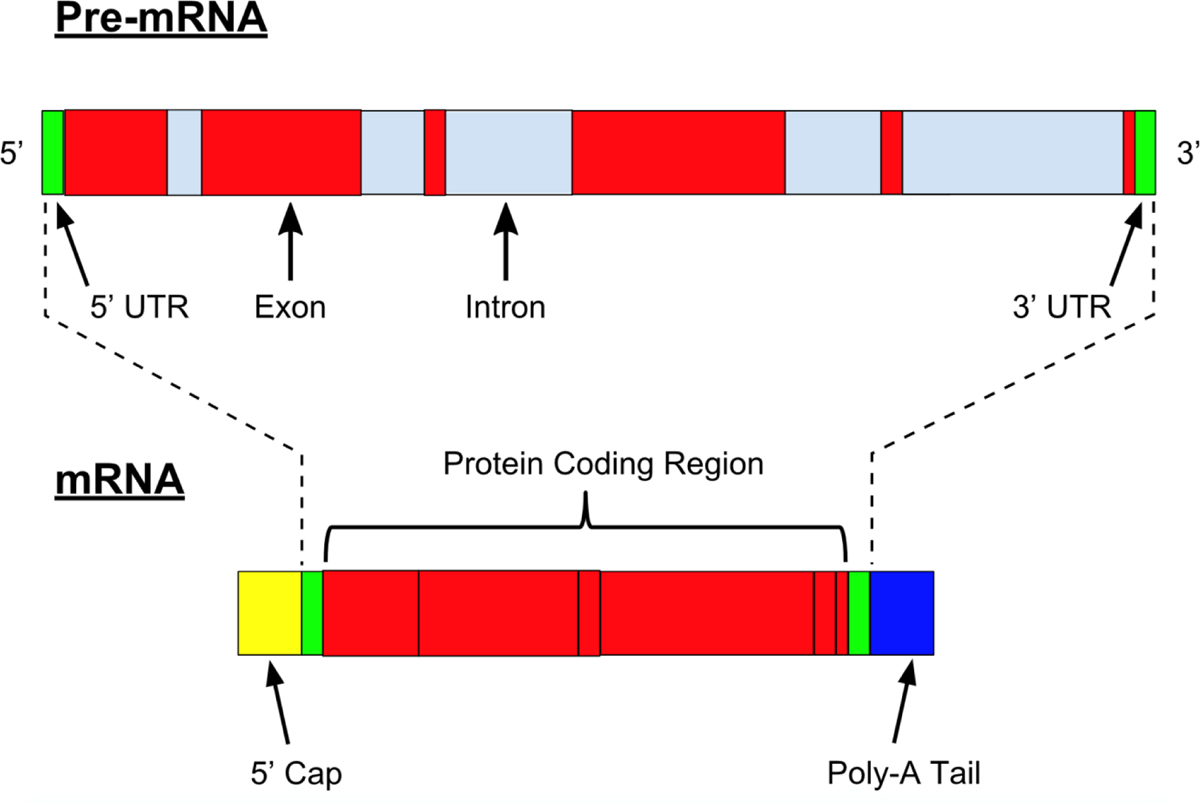

In understanding RNA therapy, a basic knowledge of DNA transcription and mRNA translation is necessary (Figure 1). In the cell nucleus, genes consist of DNA exons that encode proteins, and DNA introns, which, while not expressed, can play a crucial role in regulation (Figure 2). These elements of cellular regulation provide possible avenues for RNA therapy.

Figure 1:

mRNA Translation at Ribosome

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ribosome_mRNA_translation_en.svg

Figure 2:

Pre-mRNA and mRNA. From Nastypatty / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pre-mRNA.svg.

2. Noncoding RNA (ncRNA)

Gene expression of a given cell is influenced by noncoding RNA (ncRNA), which, while not encoding proteins, contributes to the regulation of other RNAs. ncRNA’s are inherent in the genome, and as a result, disease states are associated with their differential expression. In the retina, ncRNA has been shown to play a significant functional role, regulating factors involved in apoptosis, inflammatory response, visual perception, and photo-transduction, with altered levels noted in diseased states.[7, 8] As such, ncRNA’s are prime targets for clinical application, with the majority of RNA therapeutics in development being synthetic ncRNA’s. These regulatory elements can further be classified as micro-RNA (miRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA), as well as long noncoding RNA (lcnRNA), although less is known regarding their involvement in the retina and retinal diseases.

2.1. miRNA

MicroRNA (miRNA) is a class of ncRNA that regulates post-transcription gene expression through the imperfect binding of complementary binding sites of target mRNA with resulting translational repression and mRNA destabilization.[9] Each miRNA can target hundreds of mRNA genes, making them a prime focus for therapeutic development.[10] Additionally, their small size (20–25 bps) and stability, along with their ability to be readily taken up by endosomes and microvesicles, contribute to their potential as excellent therapeutic candidates.[11]

miRNAs are transcribed in the nucleus, often with genes of functionally related miRNA clustered on the same chromosome and expressed as a single primary transcript (pri-miRNA). Double-stranded short hairpin structures are contained within the pri-miRNA and are recognized in the nucleus by a protein complex with resulting cleavage by the RNAse III-type enzyme, Drosha, resulting in precursor miRNA (pre-miRNAs). The pre-miRNAs are then transported to the cytosol through the nuclear pore complex by exportin5, where final cleavage by another RNAse III-type enzyme, called Dicer, takes place. This results in a double-strand miRNA, where one strand then interacts and is bound to argonaute (AGO) proteins, which are then assembled to form an RNA-Induced silencing complex (RISC). Through the miRNA “guide strand”, this complex is then guided to target mRNA through imperfectly complementary target sites, usually in the 3’ untranslated region (UTR), with resulting repression of its translation.[9, 12]

2.2. siRNA

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) are another class of ncRNA that have shown potential therapeutic capabilities. Structurally, siRNA are double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) 21–23 base pairs in length.[13] Similar to miRNA, siRNA function to regulate gene expression and can lead to selective silencing of genes. Evolving as a natural defense mechanism against RNA viruses, siRNA gene silencing can lead to selective degradation of target mRNA through a process called RNA interference (RNAi).[14]

The siRNA mediated RNAi pathway begins with cytoplasmic cleavage of long dsRNA by Dicer, with resulting short dsRNA. These short dsRNA is then incorporated into a RISC complex where the two strands are separated. This strand then guides the complex to the complementary target mRNA, ultimately resulting in site-specific mRNA cleavage following association with the effector AGO 2 proteins.[15, 16] The result is then reduced expression of the target mRNA, inhibiting the translation of its functional protein. In contrast to miRNA, siRNA binding to its target is highly specific, and has been shown to have the potential ability to distinguish between genes that differ by a single nucleotide.[12, 17]

While siRNA have been observed in plant species, their existence in humans is controversial.[18] Therefore, while RNAi does not intrinsically occur in mammalians, shared proteins between the previously discussed miRNA pathway and RNAi allow for activation through synthetic molecules.[12] As such, the role of endogenous siRNA is unclear in the human or mammalian system, however exogenous siRNAs have become a powerful avenue for regulation of gene expression. Consequently, siRNA holds potential for a broad spectrum of therapeutic applications, ranging from viral infections, hereditary disorders and cancer.

Theoretical advantages of RNAi mediated by synthetic siRNA are its ability for potent target gene silencing based on the target mRNA strand sequence. This single strand of siRNA can be recycled for multiple rounds of mRNA cleavage, with its efficiency varying significantly based on numerous factors and interactions. While current knowledge is limited, several key factors are known to influence the efficiency of mRNA degradation and recycling, including siRNA design, thermodynamic end stability, target accessibility, as well as other structural features.[19–21]

siRNA are particularly susceptible to degradation by enzymes found in the serum and tissues, as well as intracellular RNAses, posing difficulty in achieving target activity.[19] Additionally, there is potential for off-target silencing, thought to be due to homology of six or seven nucleotides in the “seed region” of the siRNA sequence with endogenous miRNAs, leading to unexpected cell transformation.[19, 22] Additionally, while typically well-tolerated, in some cases, an unpredictable immune response can be triggered, along with the potential for binding to and activating Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7), which normally recognizes single stranded RNA of viruses to activate cytokine-mediated immunity.[19, 23]

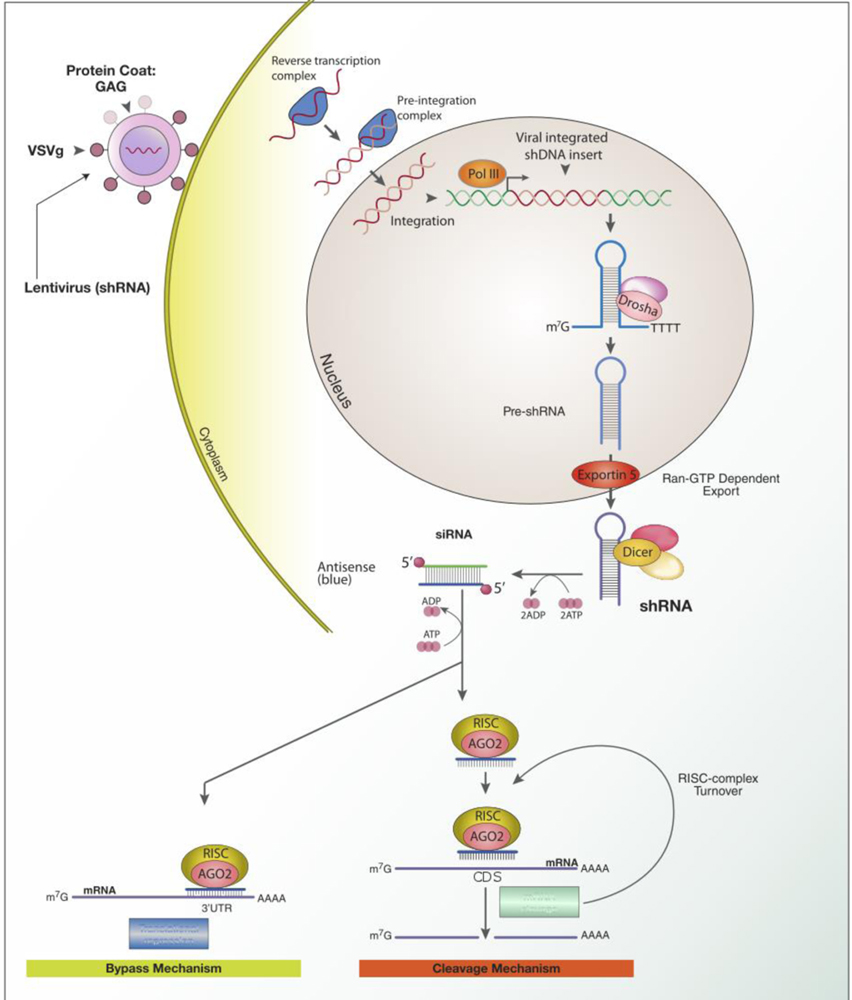

2.3. shRNA

Another form of RNAi involves short hairpin RNA (shRNA). These shRNAs can be transcribed in the nucleus by an exogenous DNA expression vector (Figure 3).[16] The shRNA transcripts are similar in structure to miRNA, consisting of two complementary 19–22 base pair RNA sequences, linked by a short hairpin of 4–11 nucleotides, in essence, forming a short dsRNA with a terminal loop.[24] The transcript is processed by an enzyme Drosha, an RNase III endonuclease and is exported to the cytoplasm as pre-shRNA for further processing by Dicer.[16] Triggering the RNAi process mentioned previously, the siRNA duplexes bind to their target mRNA and are incorporated into the RISC complex for mRNA target-specific degradation (Figure 3).[24]

Figure 3.

Delivery of shRNA and the mechanism of RNA interference. From: Dan Cojocari / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ShRNA_Lentivirus.svg

Therefore, in contrast to siRNA, the use of shRNA involves the delivery of DNA as opposed to RNA effector molecules. This allows the use of the cell’s own machinery to produce the specific shRNA transcripts. Thus, there is the ability to provide high potency sustainable effects through the use of low copy numbers. It is also thought that this provides the ability for a better safety profile with fewer off-target effects.

3. ncRNA and retinal diseases

3.1. AMD

In age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the third leading cause of blindness worldwide, miRNA regulation has been implicated as a contributing pathogenic mechanism, in addition to documented environmental risk factors and genetic predispositions. As an acquired degeneration of the retina, vision loss typically results from retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) abnormalities and drusen formation, with progression to geographic atrophy and/or choroidal neovascularization. Together, oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, inflammation, and dysregulation of the complement cascade are implicated in the pathogenesis and disease course.

As such, miRNA has been implicated in the regulation of angiogenesis, oxidative stress, immune response, and inflammation, with recent research suggesting dysregulation of the miRNA contributing to AMD pathology.[25] Past studies have evaluated miRNA expression profile in AMD patients, with miR-146a and miR155 showing the most correlation.[26, 27] Thought to be regulators of inflammation and microglial activation in response to stress, they have both been shown to be dysregulated in the retina of AMD patients.[26]

Alteration of miRNA activity levels is also associated with the development of choroidal neovascularization, with their regulation resulting in the reduction of neovascularization.[28–30] miRNA implicated in angiogenesis include miR-125b, which has been shown to be upregulated in mouse retina undergoing oxidative stress, as well as miR-17, thought to be a regulator of angiogenesis and apoptosis.[26] Consequently, further understanding of epigenetics mechanisms and miRNA, as well as their implication in the development and progression of AMD, may provide a promising avenue in treatment.

3.2. Diabetic Retinopathy

Similarly, the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy, a leading cause of blindness worldwide, is multifactorial, with evidence of aberrant expression of ncRNA contributing to development. Diabetes commonly affects the microvascular circulation of the retina, with resulting structural changes, increased permeability and altered proliferation of endothelial cells, ultimately resulting in edema and abnormal neovascularization of the retina, with subsequent vision loss. Factors shown to contribute to disease progression include oxidative stress as a result of excess reactive oxygen species due to elevated blood glucose, inflammatory mediators, and neurodegeneration with apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells.[31]

As alluded to above, miRNA plays a significant role in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis of cells, including in the retina. Also, given their role in pathogenic processes involved in diabetic retinopathy, such as angiogenesis, inflammation, and oxidative stress, miRNA have been implicated as potential biomarkers in the diagnosis and therapeutic targeting. With still much to be discovered regarding miRNA involvement in diabetic retinopathy, recent research has implicated miR-200b, miR-146a, and miR-126 as suspected contributing factors.[31] Additionally, miR-21 has been implicated due to its role in the regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-a (PPARa). In mice models, overexpression of miR-21 resulted in the downregulation of PPARa, which has been shown to contribute to retinal neovascularization. Knockout of miR-21 resulted in the prevention of the decrease in PPARa, with a reduction in retinal neovascularization and inflammation.[32] One of the earlier studies by Kovacs et al. performed RNA profiling of the retina and rat endothelial cells to show an upregulation of 80 miRNA and downregulation of 6 miRNAs, the miR-223 was found to be highly upregulated, and miR-20b was downregulated.[33] Additionally, miRNA profiling of retinal endothelial cells from diabetic mice also indicates increased expression of three miRNAs: miR-146a [34], miR-155, miR-21 and miR-200b [35]. It is noteworthy that activation of miR-146a, miR-155, miR-132 and miR-21 results in activation of NF-κB [33, 36], a key modulator of inflammation that plays an important role in the early phases of diabetic retinopathy. The miRNA levels in peripheral circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) may serve as the biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy severity. The CACs play a dual role due to 99% similarity with endothelial cells; they provide a window to retinal vascular health, and the dynamic nature of miRNA levels further helps in retinopathy severity assessment. The miR-92a is one of the candidate miRNAs, which has shown uniquely changed in diabetic retinopathy patients. miR-92a is a negative regulator of toll-like receptors (TLRs) [37] and its overexpression in CACs of diabetic individuals led to a decrease in pro-inflammatory markers, such as IL-1β and CD14 [38].

3.3. Inherited retinal disease (IRDs)

Inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are a rare group of heterogeneous disorders that are generally characterized by progressive photoreceptor loss or dysfunction, severe retinal degeneration, and resulting vision loss. IRDs can be classified as affecting the retinal periphery, central retina or macula, or both. Exhibiting a wide range of phenotypes, the most common IRDs include retinitis pigmentosa (RP), Usher syndrome, Stargardt disease, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, choroideremia, achromatopsia, and X-linked Retinoschisis, with causative mutations identified in over 270 genes. [39–43]

IRDs have been at the forefront of the development of gene and RNA therapy, given the retina’s favorable anatomic and immunologic characteristics, as well as a large number of monogenic disorders. Naturally, the retina provides a non-invasive ability to monitor for disease progression or therapeutic response. Additionally, the retina offers accessibility for target cell delivery, as well as a relative immune privilege, which limits inflammatory response.

Most frequently, IRDs result from mutations in a single gene, mainly occurring in the photoreceptors or, less frequently, RPE cells. In non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa (RP), for example, more than 3000 mutations from 70 genes have currently been identified.[44] The inheritance pattern for RP includes autosomal dominant (15–25%), autosomal recessive (5–20%), X-linked (5–15%), and unknown patterns (40–50%). In autosomal dominant RP (adRP), mutations in 22 genes have been identified, with RHO being most common (20–30%), in addition to PRPF31, PRPH2, and RP1. The most common causative gene in autosomal recessive RP (arRP) is USH2A (10–15%), with the RPGR and RP1 genes accounting for most cases of X-linked RP (xlRP).[44]

Thus far, there has been one causative mutation identified in miRNA resulting in IRD, with a heterozygous mutation in the seed region of miR-204 resulting in retinal dystrophy and bilateral coloboma. This is thought to be due to a gain-of-function mutation, shedding light on the role of miRNA as pathogenic agents in genetic diseases.[45] Oxidative stress is also thought to play a significant role in etiopathogenesis of IRDs, such as RP, through ncRNA. Induction of oxidative stress has been shown to result in altered expression of both miRNA and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), with resulting altered regulation of angiogenesis, extracellular matrix integrity, physiologic or pathologic autophagy, and cell death induction, ultimately leading to retinal cell death.[46, 47] Several miRNA and lncRNA are thought to contribute to RP development and progression with five RP causative genes associated with these altered miRNA.[48, 49]

In mice, miR-124a, the most abundant miRNA expressed in vertebrate CNS, has been shown to be essential for the proper development of the retina through prevention of apoptosis through regulation of key elements.[50] Mice models have also demonstrated the importance of miR-183/96/182 cluster for proper postnatal cellular differentiation and photoreceptor development. Knockout of this miRNA cluster resulted in early-onset and progressive photoreceptor defects, with resulting scotopic and photopic electroretinogram abnormalities.[51] Additionally, dysregulation of miRNA in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) has been shown, corroborating their role in the development of inherited retinal degenerations.[8, 52]

4. ncRNA in treating retinal diseases

4.1. miRNAs

While promising following their initial discovery in 1993, miRNA utility as therapeutic agents is yet to be successful in reaching clinical application. Their limitations are thought to be due to the nature of the imperfect binding of the miRNA to its target sequence, requiring only a 2–8 nucleotide seed sequence.[12] While this ability to target numerous transcripts has been seen as a potential advantage as pharmacology aims to regulate multiple targets when combatting disease, the ubiquitous binding can result in adverse off-target effects.[53–55] For example, while the synthesized mRNA compounds are designed to bind to their targets exclusively, the imperfect nature of its binding may allow it to bind and regulate another gene. In addition, this binding capacity is accentuated by the limited length of the eight nucleotides long seed sequence, increasing the chance for similar sequences to be present at the intended target, and in turn, increased likelihood for off-target effects.[12] Further, miRNA interactions are not entirely understood, with no surety of physiologic mRNA regulation, even with high seed sequence complementarity.[56] Recently, however, intravitreal miR-146 has shown therapeutic potential in diabetic rat models, inhibiting diabetes-induced NK-κβ activation, along with its downstream effects of associated microvascular leakage and retinal function defects.[57]

4.2. siRNA

In the retina, early clinical trials involving siRNA agents showed potential in patients with AMD, however, the studies ultimately failed to reach primary efficacy endpoints and thus halted their development. Sirna-027 (AGN-211745, Allergan), a clinical candidate designed to silence the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene, for example, failed to reach the endpoint in randomized control trials compared to ranibizumab (Table 1).[58] Bevasiranib (Cand5, Opko Health, INC./Acuity Pharmaceuticals), another clinical candidate developed to target VEGF in AMD patients, demonstrated stabilization of visual acuity in the majority of patients and improvement in visual acuity in more than one-third of patients in initial studies. Later, a phase 3 trial testing Bevasiranib, in combination with ranibizumab, failed to meet the primary endpoint (Table 1).[59, 60]

Table 1.

Retina RNA Therapeutics Clinical Trials. Data obtained from https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

| Clinical Trials | RNA Therapeutic Strategy | Disease | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00363714 | siRNA (SIRNA-027) | Sub-foveal CNVM secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration | Completed |

| NCT00306904 | siRNA (Cand5/Bevasiranib) | Diabetic Macular Edema | Completed |

| NCT01445899 | siRNA (PF-04523655) | Diabetic Macular Edema | Completed |

| NCT01064505 | siRNA (QPI-1007) | Optic Nerve Atrophy in NAION | Completed |

| NCT02947867 | ASO (Aganirsen) | Ischemic CRVO to prevent Neovascular Glaucoma | Unknown |

| NCT03780257 | ASO (QR-421a) | Retinitis Pigmentosa/Usher Syndrome Type 2 | Recruiting |

| NCT04123626 | ASO (QR-1123) | Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa | Recruiting |

| NCT03815825 | ASO (IONIS-FB-LRx) | Geographic Atrophy secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration | Recruiting |

| NCT03913143 | ASO (Sepofarsen/QR-110) | Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis | Recruiting |

However, potential promising siRNA candidates continue to exist, such as PF-4523655 (Pfizer/Quark Pharmaceuticals). Developed for the treatment of AMD and diabetic macular edema, PF-4523655 is a siRNA targeting DNA damage-inducible transcript 4 (DDIT-4) gene (also known as REDD1 or RTP-801) to inhibit its expression. In Phase I/II clinical studies, this synthetic siRNA was well-tolerated and later showed a dose-dependent increase in visual acuity in patients with diabetic macular edema in a Phase 2 study.[61–63] Currently, this candidate remains under investigation in a Phase 2b clinical study. Additional siRNA therapeutic agents remain in development, with Regeneron and Alnylam pharmaceuticals recently announcing a collaboration in 2019 (Table 1).[64]

4.3. shRNA

The use of shRNA is encouraging, especially in cases of autosomal dominant disorders, namely adRP. Here, gene therapy typically must suppress a mutation causing a toxic gain of function. A promising approach involves a “knockdown and replace” strategy, whereby shRNA targets RHO in a mutation independent manner and is co-packaged in a single adeno-associated viral vector with an RNAi resistant replacement RHO gene. Efficacy of this technique was shown in pre-clinical canine models demonstrating suppression of endogenous RHO RNA with replacement RHO gene resulting in 30% of normal protein levels, as well as protection of photoreceptors from retinal degeneration following subretinal vector administration.[65] Iveric Bio is currently attempting to apply this model to humans using mutation independent gene therapy (IC-100).[66] Additional studies have shown the ability to silence endogenous VEGF production with anti-VEGF shRNA AAV2/8 vector administered subretinally, demonstrating reduction of choroidal neovascularization in AMD mouse models.[67]

4.4. Antisense Oligonucleotides

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) are synthetic single-strand RNA (or DNA) oligonucleotides 16–21 nucleotides in length that have enjoyed success in retinal disease in the past.[68, 69] Fomivirsen, for example, was a very effective ASO agent used in the treatment of AIDS patients suffering from CMV retinitis, even in cases resistant to conventional therapies.[70] It was eventually withdrawn from the market in 2006 with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, which dramatically reduced the incidence of CMV retinitis, but Fomivirsen paved the way for potential future ASO-based retinal treatments.

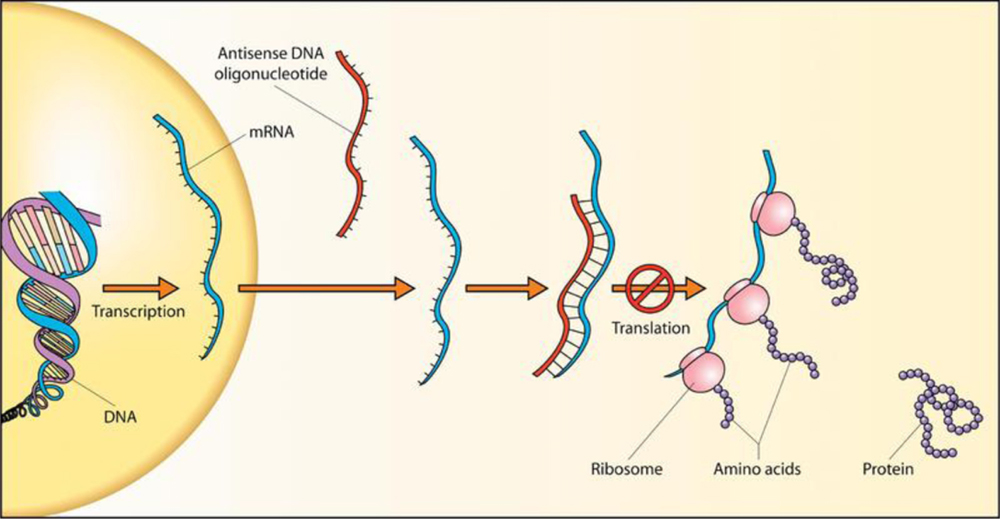

The majority of ASOs are developed to bind to target RNA and promote RNA cleavage and degradation through the enzyme RNase H1 (Figure 4). The RNase H family of enzymes are present in all mammalian cells and mediates cleavage of RNA in an RNA-DNA heteroduplex.[71] RNase H1, active as a single peptide, is directed by the ASO containing five or more consecutive DNA nucleotides and binds to the RNA-DNA heteroduplex through an RNA binding domain on the N-terminus of the protein with subsequent cleavage of the RNA strand.[71]

Figure 4:

Antisense DNA oligonucleotide.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antisense_DNA_oligonucleotide.png

Additionally, ASOs can modulate RNA in several other ways through a diverse set of post-binding mechanisms, without resulting RNA degradation. The process by which this occurs is referred to as translation or hybridization arrest. These ASO are designed to bind to, or adjacent to, the translation initiation region of an mRNA. This binding is thought to result in either the blocking of the 40S subunit scanning of the transcript, assembling of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, or movement of the ribosome down the transcript following binding.[71] The use of ASO in this manner is limited therapeutically; however, as the translation arrest does not lead to decreased mRNA levels, it is difficult to quantify protein variation. Also, there is limited space on the mRNA where binding is effective.[71]

ASOs do, however, provide an avenue for potential therapeutic strategies without RNA degradation through interfering with RNA intermediary metabolism. In RNA metabolism, most mRNA goes through several processing steps, including splicing, polyadenylation, and addition of the 7mG 5’-cap structure. Additionally, approximately 90% of human transcripts demonstrate alternative splicing, resulting in proteins that can exhibit distinct biological functions.[71] Further, many mRNA’s contain alternate polyadenylation sites, resulting in the inclusion or loss of RNA regulatory elements. Thus, ASOs represent the unique ability for RNA intermediary metabolism therapy through two strategies. One mechanism is through modulating RNA splicing, masking enhancer, and repressor sequences. Another mechanism is through modulation of poly-A site selection in a transcript.[71]

In the retina, current ASO therapies in development are targeting disease mutations which result in splicing defects. ProQR, for example, has demonstrated promising results in a phase 1/2 clinical trial for its experimental drug sepofarsen (QR-110) in patients with Leber’s congenital amaurosis 10 (LCA10). This novel therapy is an ASO that targets the p.Cys998X mutation in the CEP290 gene, which results in aberrant splicing with resulting premature stop codon, a frequent cause of LCA ciliopathies.[72, 73] Sepofarsen restores correct splicing and, as a result, has demonstrated vision improvement after 12 months of treatment their recent trial, with plans to proceed to a phase 2/3 clinical trial (Table 1).[74]

Additionally, ProQR is developing an ASO for Usher syndrome type 2 and non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa due to mutations in exon 13 of the USH2A gene, with an ongoing phase 1/2 study of an experimental drug QR-421a.[75] Similarly, development and early clinical trials are underway for the treatment of adRP due to the P23H mutation in RHO, through binding and degradation of the mutated RHO mRNA by RNase mediated cleavage (QR-1123).[76] Lastly, ProQR is also developing an ASO, QR-1011, to correct a common mutation in ABCA4, resulting in aberrant splicing with the exclusion of exon 39 (Table 1).[77]

4.5. Translational Read-through inducing drugs and Eukaryotic ribosomal selective glycosides

In humans, three of the sixty-four triplet codons (UAA, UAG, UGA) promote the translational arrest and are referred to as “stop codons”. Point mutations may arise in the triplet codon normally encoding a specific amino acid, altering the product to a premature stop codon that is then transcribed into the mRNA. As mentioned above, this results in premature translational arrest of the mRNA and the absence of full-length functional protein.

To some extent, however, this stop codon is occasionally overridden and ignored by the translational machinery, in a phenomenon known as translational read-through. This occurs when a similar tRNA successfully competes with termination factors at the nonsense codon, where the tRNA mispairing results in the incorporation of an amino acid into the peptide chain and elongation of protein synthesis with the translation of the full-length protein from the mutated mRNA.[78] While this process usually is infrequent, therapies aim to target these mutations through targeting post-transcriptional control processes and inducing translational read-through, using drugs called translational read-through inducing drugs (TRIDS) to increase expression of the full-length protein.

Eukaryotic ribosomal selective glycosides (ERSG) are one type of TRIDS that functions to increase ribosomal read-through activity of an mRNA. Unlike other types of RNA therapeutics discussed previously, ERSG are not mutation specific. Eloxx pharmaceuticals is currently developing ERSG for treatment of cystic fibrosis and cystinosis, with their lead compound, ELX-02, currently undergoing phase 2 study following successful demonstration of safety and tolerability.[79] Pre-clinical studies of ELX-02 demonstrated the ability to restore expression and function of disease-associated nonsense mutations in cystic fibrosis models through induction of translation read through. This read-through activity of ELX-02 is carried out by increasing the probability that a near cognate transfer RNA (tRNA) will bind premature stop codons and remove class 1 releasing factors, enabling the continuation of translation.[79]

Inherited diseases also may result from nonsense (noncoding) mutations, which cause premature terminating codons and subsequent premature translational arrest of the mRNA. Approximately 12% of inherited diseases are caused by nonsense mutations, with much higher rates in certain diseases, such as choroideremia where 30% of cases arise due to premature stop codons.[80] As such, nonsense mutations provide an important target for clinical application. Eloxx has plans to apply their ERSG strategy to rare IRDs caused by nonsense mutations with initial focus on Usher syndrome.[81]

5. Conclusion

Significant scientific and technological advancements have furthered our understanding of genetic conditions and inherited diseases, and RNA based therapeutics have drawn great attention recently as the basis of vaccine development amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond this urgent application, however, RNA (and DNA) therapeutics provide a potential avenue for the treatment of genetic conditions, as well as acquired retinal diseases with genetic associations. At the forefront, therapies are in development for common conditions such as DR and AMD, targeting ncRNA as our understanding of regulatory elements and their association with pathogenesis of these diseases grows. Additionally, RNA therapies are in development to target IRD using multiple approaches, such as shRNA targeting autosomal dominant conditions in a “knockdown and replace” strategy, ASO to restore splicing defects, and ERSG targeting nonsense mutations. As our understanding of genetic conditions, inherited diseases and acquired multifactorial diseases improves, RNA therapeutics provide a potential avenue for treatment, correcting genetic defects at a cellular level, potentially as permanent solutions.

6. Expert Opinion

RNA therapies have gained significant traction following their approval to treat devastating systemic conditions such as spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, as well as the potential for generating neutralizing antibodies amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In the retina, ncRNA has been implicated in the pathogenesis of common retinal diseases such as AMD and DR. miRNA are thought to regulate angiogenesis, oxidative stress, the immune response, and inflammation, with their dysregulation contributing to the development of DR and AMD, as well as its complications of choroidal neovascularization. miRNA may also serve as biomarkers of these diseases.

Consequently, there has been great interest in RNA-based therapies for AMD and DR, but early siRNA clinical candidates failed to reach primary efficacy endpoints (Sirna-027, Cand5). Currently, PF-4523655 is undergoing Phase 2b clinical study for DME. Additional development of siRNA therapies, potentially for AMD and DR, is underway with recently announced collaboration between Regeneron and Alnylam pharmaceuticals. As our understanding and discovery of causative ncRNA and regulatory elements improve, there is potential for broad applicability of RNA therapy to the treatment of these common acquired conditions, with current high unmet needs.

The retina has played a role in gene therapy development given a large number of monogenic disorders, its relative immune privilege, and the ability to noninvasively monitor disease progression and therapeutic response. In inherited retinal diseases, RNA-based therapy has the potential to address heretofore untreatable disorders that cause relentless loss of vision. Numerous RNA-based treatment strategies are in development, including siRNA therapy with its high specificity, shRNA to “knock down” autosomal dominant toxic gain of function mutated genes, ASO multifaceted approach to restore splicing defects or RNA cleavage, and ERSGs with potentially broad applicability across mutations.

ASOs are furthest along in development, with the first approval for an ASO in 1998 for intravitreal treatment of CMV retinitis, and the early clinical data from ProQR’s trial of sepofarsen (QR-110) in patients with LCA10 shows great promise. ProQR is also developing QR-421a for Usher syndrome type 2 and non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa due to mutation in USH2A gene, QR-1123 for adRP due to P23H mutation in RHO, and QR-1011 for Stargardt disease. Strategies involving shRNA are also hopeful, as this approach could be used in gene therapies to “knock down” a toxic gain of function mutated gene in adRP, a rather common IRD, and replace the mutated with concomitant gene augmentation. Iveric Bio is developing IC-100 with this strategy to target RHO in adRP.

Unlike gene augmentation therapy, which is typically administered via pars plana vitrectomy and subretinal injection, many RNA-based therapies can be conveniently administered intravitreally and have potential for a pan-retinal effect. However, RNA-based therapies are generally mutation-specific and may require repeat administration, unlike gene augmentation, which provides an entire normal copy of a gene after one-time administration. Nevertheless, ERSGs have potential utility across mutations for IRDs that involve premature stop codons. With promising early clinical trials of ELX-02 (Eloxx Pharmaceuticals) in cystic fibrosis, this approach will target IRDs resulting from nonsense mutations, with an initial focus on Usher syndrome.

In summary, despite limited understanding of the complex regulatory elements in the human genome, and the potential for unforeseen off-target effects, there has been rapid advancement of RNA-based therapies. The versatility of these therapies, with multiple therapeutic strategies, and applicability to both common disorders as well as rare IRDs, shows great promise. Accordingly, the retina community eagerly looks forward to an expanding repertoire of novel treatments for blinding conditions such as AMD, DR, and IRDs.

Article Highlights.

Gene expression is precisely controlled through complex regulatory elements, including noncoding RNA (ncRNA).

ncRNA is further classified as microRNA (miRNA), regulating gene expression through the binding to complementary sites on the target RNA, resulting in translation repression, and small-interfering RNA (siRNA), leading to selective degradation of the target messenger RNA (mRNA) through RNA interference (RNAi), as well as long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) although still early in their discovery of association with retinal diseases. RNAi can also be triggered by short hairpin RNA (shRNA), which are transcribed in the nucleus by exogenous DNA vectors, and ultimately lead to mRNA target specific degradation.

ncRNA has been implicated in the pathogenesis of common retinal diseases such as AMD and DR. miRNA are thought to be regulators of angiogenesis, oxidative stress, the immune response, and inflammation, with their dysregulation contributing to the development of DR and AMD, as well as complications of choroidal neovascularization. miRNA may also serve as biomarkers of these diseases.

Dysregulation of miRNA is also thought to contribute to the development of inherited retinal diseases (IRD), such as retinitis pigmentosa.

RNA therapeutics are in development for the treatment of retinal diseases by targeting ncRNA. As a therapeutic target, further research into miRNA mechanisms and strategies is needed due to the nature of their imperfect binding with the potential for inadvertent off-target effects. Similarly, earlier siRNA clinical candidates failed to reach primary efficacy endpoints (Sirna-027, Cand5). PF-4523655, however, is a siRNA clinical candidate showing promise in the treatment of patients with diabetic macular edema and is currently undergoing Phase 2b clinical study.

shRNA therapies have shown promise in the treatment of autosomal dominant disorders, such as autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP), using a “knockdown and replace” strategy. IC-100 (Iveric Bio) is a clinical candidate looking to apply this strategy in a mutation independent approach to target RHO through shRNA co-packaged with replacement RHO DNA.

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASO), another avenue for RNA therapeutics, can promote RNA cleavage and degradation or modulate RNA through post-binding mechanisms without resulting RNA degradation through translation (or hybridization) arrest or through interfering with RNA intermediary metabolism. Current therapies in development by ProQR target splicing defects, such as QR-110 for patients with Leber’s congenital amaurosis 10, QR-421a for Usher syndrome type 2 and non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa due to mutation in USH2A gene, QR-1123 for adRP due to P23H mutation in RHO, and QR-1011 for Stargardt disease.

Translational Read-through inducing drugs (TRID) and eukaryotic ribosomal selective glycosides (ERSG) target nonsense mutations causing premature stop codons with the therapeutic goal of increasing expression of the normal full-length protein. Successful early clinical trials of ELX-02 (Eloxx Pharmaceuticals) in cystic fibrosis patients has been demonstrated, and this approach will target IRDs resulting from nonsense mutations, with an initial focus on Usher syndrome.

Funding

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Eye Institute (R01 EY027779).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

TA Ciulla has an employment relationship at Clearside Biomedical Inc. However, this manuscript was written during his work as a Volunteer Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology at Indiana University School of Medicine, and none of the work herein represents any official position or opinion of Clearside or its management. A Bhatwadekar reports funding support from NEI R01 EY027779. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Mercuri E, et al. , Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med, 2018. 378(7): p. 625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell JR, et al. , Longitudinal effect of eteplirsen versus historical control on ambulation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol, 2016. 79(2): p. 257–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heo YA, Golodirsen: First Approval. Drugs, 2020. 80(3): p. 329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbett KS, et al. , SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness. bioRxiv, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.A randomized controlled clinical trial of intravitreous fomivirsen for treatment of newly diagnosed peripheral cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with AIDS. Am J Ophthalmol, 2002. 133(4): p. 467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maguire AM, et al. , Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl in RPE65 Mutation-Associated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: Results of Phase 1 and 3 Trials. Ophthalmology, 2019. 126(9): p. 1273–1285.*Demonstrates potential efficacy of gene therapy in retinal diseases.

- 7.Desjarlais M, et al. , MicroRNA expression profile in retina and choroid in oxygen-induced retinopathy model. PLoS One, 2019. 14(6): p. e0218282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuzic M, et al. , Retinal miRNA Functions in Health and Disease. Genes (Basel), 2019. 10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundermeier TR and Palczewski K, The physiological impact of microRNA gene regulation in the retina. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2012. 69(16): p. 2739–2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carthew RW and Sontheimer EJ, Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell, 2009. 136(4): p. 642–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harries LW, RNA Biology Provides New Therapeutic Targets for Human Disease. Frontiers in genetics, 2019. 10: p. 205–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajan S and Hutvagner G, RNA-Based Therapeutics: From Antisense Oligonucleotides to miRNAs. Cells, 2020. 9(1): p. 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaczmarek JC, Kowalski PS, and Anderson DG, Advances in the delivery of RNA therapeutics: from concept to clinical reality. Genome Med, 2017. 9(1): p. 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster S, Miesen P, and van Rij RP, Antiviral RNAi in Insects and Mammals: Parallels and Differences. Viruses, 2019. 11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crooke ST, et al. , RNA-Targeted Therapeutics. Cell Metab, 2018. 27(4): p. 714–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coutinho MF, et al. , RNA Therapeutics: How Far Have We Gone? Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019. 1157: p. 133–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz DS, et al. , Designing siRNA that distinguish between genes that differ by a single nucleotide. PLoS genetics, 2006. 2(9): p. e140–e140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daugaard I and Hansen TB, Biogenesis and Function of Ago-Associated RNAs. Trends Genet, 2017. 33(3): p. 208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavrilov K and Saltzman WM, Therapeutic siRNA: principles, challenges, and strategies. Yale J Biol Med, 2012. 85(2): p. 187–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song E, et al. , Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat Biotechnol, 2005. 23(6): p. 709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heale BS, et al. , siRNA target site secondary structure predictions using local stable substructures. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005. 33(3): p. e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birmingham A, et al. , 3’ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat Methods, 2006. 3(3): p. 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornung V, et al. , Sequence-specific potent induction of IFN-alpha by short interfering RNA in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Nat Med, 2005. 11(3): p. 263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore CB, et al. , Short hairpin RNA (shRNA): design, delivery, and assessment of gene knockdown. Methods Mol Biol, 2010. 629: p. 141–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, et al. , miRNAs as potential therapeutic targets for age-related macular degeneration. Future Med Chem, 2012. 4(3): p. 277–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berber P, et al. , An Eye on Age-Related Macular Degeneration: The Role of MicroRNAs in Disease Pathology. Mol Diagn Ther, 2017. 21(1): p. 31–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strafella C, et al. , The Interplay between miRNA-Related Variants and Age-Related Macular Degeneration: EVIDENCE of Association of MIR146A and MIR27A. Int J Mol Sci, 2019. 20(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Q, et al. , Regulation of angiogenesis and choroidal neovascularization by members of microRNA-23~27~24 clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(20): p. 8287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen J, et al. , MicroRNAs regulate ocular neovascularization. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy, 2008. 16(7): p. 1208–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabatel C, et al. , MicroRNA-21 exhibits antiangiogenic function by targeting RhoB expression in endothelial cells. PLoS One, 2011. 6(2): p. e16979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong Q and Su G, Roles of miRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Biosci Rep, 2017. 37(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Q, et al. , Pathogenic Role of microRNA-21 in Diabetic Retinopathy Through Downregulation of PPARα. Diabetes, 2017. 66(6): p. 1671–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacs B, et al. , MicroRNAs in early diabetic retinopathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011. 52(7): p. 4402–9.*Important study highliging miRNA upregulation in retinal endothelial cells.

- 34.Wang Q, et al. , Regulation of Retinal Inflammation by Rhythmic Expression of MiR-146a in Diabetic Retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2014. 55(6): p. 3986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McArthur K, et al. , MicroRNA-200b regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated alterations in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes, 2011. 60(4): p. 1314–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowan C, et al. , MicroRNA-146 Inhibits Thrombin-Induced NF-κB Activation and Subsequent Inflammatory Responses in Human Retinal Endothelial Cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2014. 55(8): p. 4944–4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai L, et al. , MicroRNA-92a negatively regulates Toll-like receptor (TLR)-triggered inflammatory response in macrophages by targeting MKK4 kinase. J Biol Chem, 2013. 288(11): p. 7956–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatwadekar AD, et al. , miR-92a Corrects CD34+ Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes by Modulating Core Circadian Genes Involved in Progenitor Differentiation. Diabetes, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Sohocki MM, et al. , Prevalence of mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa and other inherited retinopathies. Human mutation, 2001. 17(1): p. 42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.RetNet. [cited 2020 May 21]; Retinal Information Network]. Available from: https://sph.uth.edu/RETNET/.

- 41.Donato L, et al. , Stargardt Phenotype Associated With Two ELOVL4 Promoter Variants and ELOVL4 Downregulation: New Possible Perspective to Etiopathogenesis? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2018. 59(2): p. 843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Angelo R, et al. , Possible protective role of the ABCA4 gene c.1268A>G missense variant in Stargardt disease and syndromic retinitis pigmentosa in a Sicilian family: Preliminary data. Int J Mol Med, 2017. 39(4): p. 1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scimone C, et al. , A novel RLBP1 gene geographical area-related mutation present in a young patient with retinitis punctata albescens. Hum Genomics, 2017. 11(1): p. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dias MF, et al. , Molecular genetics and emerging therapies for retinitis pigmentosa: Basic research and clinical perspectives. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2018. 63: p. 107–131.*Important work discussing inheritance patterns for retinitis pigmentosa.

- 45.Conte I, et al. , MiR-204 is responsible for inherited retinal dystrophy associated with ocular coloboma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015. 112(25): p. E3236–45.*miRNA shown to be directly associated with development of inherited retinal dystrophy.

- 46.Donato L, et al. , Effects of A2E-Induced Oxidative Stress on Retinal Epithelial Cells: New Insights on Differential Gene Response and Retinal Dystrophies. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020. 9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donato L, et al. , Discovery of GLO1 New Related Genes and Pathways by RNA-Seq on A2E-Stressed Retinal Epithelial Cells Could Improve Knowledge on Retinitis Pigmentosa. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020. 9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donato L, et al. , miRNAexpression profile of retinal pigment epithelial cells under oxidative stress conditions. FEBS Open Bio, 2018. 8(2): p. 219–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donato L, et al. , Transcriptome Analyses of lncRNAs in A2E-Stressed Retinal Epithelial Cells Unveil Advanced Links between Metabolic Impairments Related to Oxidative Stress and Retinitis Pigmentosa. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020. 9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanuki R, et al. , miR-124a is required for hippocampal axogenesis and retinal cone survival through Lhx2 suppression. Nat Neurosci, 2011. 14(9): p. 1125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lumayag S, et al. , Inactivation of the microRNA-183/96/182 cluster results in syndromic retinal degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2013. 110(6): p. E507–E516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Genini S, et al. , Altered miRNA expression in canine retinas during normal development and in models of retinal degeneration. BMC genomics, 2014. 15(1): p. 172–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jackson AL, et al. , Widespread siRNA “off-target” transcript silencing mediated by seed region sequence complementarity. RNA (New York, N.Y.), 2006. 12(7): p. 1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh S, Narang AS, and Mahato RI, Subcellular fate and off-target effects of siRNA, shRNA, and miRNA. Pharm Res, 2011. 28(12): p. 2996–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Y, et al. , Bottleneck limitations for microRNA-based therapeutics from bench to the bedside. Pharmazie, 2015. 70(3): p. 147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seitz H, Redefining microRNA targets. Curr Biol, 2009. 19(10): p. 870–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhuang P, Muraleedharan CK, and Xu S, Intraocular Delivery of miR-146 Inhibits Diabetes-Induced Retinal Functional Defects in Diabetic Rat Model. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 2017. 58(3): p. 1646–1655.*This study demonstrates therapeutic potential of miRNA.

- 58.Kaiser PK, et al. , RNAi-based treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration by Sirna-027. Am J Ophthalmol, 2010. 150(1): p. 33–39.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singerman L, Combination therapy using the small interfering RNA bevasiranib. Retina, 2009. 29(6 Suppl): p. S49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garba AO and Mousa SA, Bevasiranib for the treatment of wet, age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Eye Dis, 2010. 2: p. 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang J, et al. , Progress on ocular siRNA gene-silencing therapy and drug delivery systems. Fundam Clin Pharmacol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Nguyen QD, et al. , Dose-ranging evaluation of intravitreal siRNA PF-04523655 for diabetic macular edema (the DEGAS study). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012. 53(12): p. 7666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.PF-655. Pipeline [cited 2020 June 23]; Available from: http://quarkpharma.com/?page_id=28.

- 64.Regeneron. Investors and Media. [cited 2020 June 23]; Available from: https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regeneron-and-alnylam-announce-broad-collaboration-discover.

- 65.Cideciyan AV, et al. , Mutation-independent rhodopsin gene therapy by knockdown and replacement with a single AAV vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018. 115(36): p. E8547–e8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bio I Gene Therapy [cited 2020 June 27]; Available from: https://ivericbio.com/gene-therapy/#adrp.

- 67.Askou AL, et al. , Reduction of choroidal neovascularization in mice by adeno-associated virus-delivered anti-vascular endothelial growth factor short hairpin RNA. J Gene Med, 2012. 14(11): p. 632–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Geary RS, et al. , Pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and cell uptake of antisense oligonucleotides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2015. 87: p. 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bennett CF, Therapeutic Antisense Oligonucleotides Are Coming of Age. Annu Rev Med, 2019. 70: p. 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jabs DA and Griffiths PD, Fomivirsen for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol, 2002. 133(4): p. 552–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bennett CF and Swayze EE, RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2010. 50: p. 259–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.ProQR. QR-110 Clinical Trial: Study 001 [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://www.proqr.com/sepofarsen-phase-1-2-study-001-for-lebers-congenital-amaurosis/.

- 73.Cideciyan AV, et al. , Effect of an intravitreal antisense oligonucleotide on vision in Leber congenital amaurosis due to a photoreceptor cilium defect. Nature Medicine, 2019. 25(2): p. 225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.ProQR. News Release [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://ir.proqr.com/news-releases/news-release-details/proqr-announces-positive-top-line-results-phase-12-study.

- 75.ProQR. About Usher Syndrome Type 2 [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://www.proqr.com/qr-421a-for-usher-syndrome-type-2/.

- 76.ProQR. About adRP. [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://www.proqr.com/qr-1123-for-adrp/.

- 77.ProQR. ProQR R&D Day Presentation. 2019. [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://ir.proqr.com/static-files/a04d2d08-6e89-437a-9057-3d409f6f447e.

- 78.Nagel-Wolfrum K, et al. , Translational read-through as an alternative approach for ocular gene therapy of retinal dystrophies caused by in-frame nonsense mutations. Vis Neurosci, 2014. 31(4–5): p. 309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leubitz A, et al. , Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Single Ascending Doses of ELX-02, a Potential Treatment for Genetic Disorders Caused by Nonsense Mutations, in Healthy Volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev, 2019. 8(8): p. 984–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nagel-Wolfrum K, et al. , Targeting Nonsense Mutations in Diseases with Translational Read-Through-Inducing Drugs (TRIDs). BioDrugs, 2016. 30(2): p. 49–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pharmaceuticals E Development plans and pipeline. [cited 2020 June 28]; Available from: https://www.eloxxpharma.com/pipeline/.