SUMMARY

Metastasis has been considered as the terminal step of tumor progression. However, recent genomic studies suggest that many metastases are initiated by further spread of other metastases. However, the corresponding pre-clinical models are lacking and underlying mechanisms are elusive. Using several approaches including parabiosis and an evolving barcode system, we demonstrated that the bone microenvironment facilitates breast and prostate cancer cells to further metastasize and establish multi-organ secondary metastases. We uncovered that this metastasis-promoting effect is driven by epigenetic reprogramming that confers stem cell-like properties on cancer cells disseminated from bone lesions. Furthermore, we discovered that enhanced EZH2 activity mediates the increased stemness and metastasis capacity. The same findings also apply to single cell-derived populations, indicating mechanisms distinct from clonal selection. Taken together, our work revealed an unappreciated role of the bone microenvironment in metastasis evolution, and elucidated an epigenomic reprogramming process driving terminal-stage, multi-organ metastases.

Keywords: Bone Metastasis, Disseminated Tumor Cells, Secondary Metastasis, Epigenomic Reprograming, EZH2, Stemness, Plasticity, Evolving Barcodes, Organ Tropism, Circulating Tumor Cells

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Delineation of cancer cell spreading from primary bone metastasis by an evolving barcode system highlights the impact of the bone microenvironment in shaping secondary metastasis through mechanisms distinct from clonal selection.

INTRODUCTION

Metastasis to distant organs is the major cause of cancer-related deaths. Bone is the most frequent destination of metastasis in breast cancer and prostate cancer (Gundem et al., 2015; Kennecke et al., 2010; Smid et al., 2008). In the advanced stage, bone metastasis is driven by the paracrine crosstalk among cancer cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, which together constitute an osteolytic vicious cycle (Esposito et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2003; Kingsley et al., 2007; Weilbaecher et al., 2011). Specifically, cancer cells secrete molecules such as PTHrP, which act on osteoblasts to modulate the expression of genes including RANKL and OPG (Boyce et al., 1999; Juárez and Guise, 2011). The alterations of these factors in turn boost osteoclast maturation and accelerate bone resorption. Many growth factors (e.g., IGF1) deposited in the bone matrix are then released, and reciprocally stimulate tumor growth. This knowledge laid the foundation for clinical management of bone metastases (Coleman et al., 2008).

The urgency of bone metastasis research is somewhat controversial. It has long been noticed that, at the terminal stage, breast cancer patients usually die of metastases in multiple organs. In fact, compared to metastases in other organs, bone metastases are relatively easier to manage. Patients with the skeleton as the only site of metastasis usually have better prognosis than those with visceral organs affected (Coleman and Rubens, 1987; Coleman et al., 1998). These facts argue that perhaps metastases in more vital organs should be prioritized in research. However, metastases usually do not occur synchronously. In 45% of metastatic breast cancer cases, bone is the first organ that shows signs of metastasis, much more frequently compared to the lungs (19%), liver (5%) and brain (2%) (Coleman and Rubens, 1987). More importantly, in more than two-thirds of cases, metastases will not be limited to the skeleton, but rather subsequently occur to other organs and eventually cause death (Coleman, 2006; Coleman and Rubens, 1987; Coleman et al., 1998). This raises the possibility of secondary dissemination from the initial bone lesions to other sites. Indeed, recent genomic analyses concluded that the majority of metastases result from seeding from other metastases, rather than primary tumors (Brown et al., 2017; Gundem et al., 2015; Ullah et al., 2018a). Thus, it is imperative to investigate further metastatic seeding from bone lesions, as it might lead to prevention of the terminal stage, multi-organ metastases that ultimately cause the vast majority of deaths.

Despite its potential clinical relevance, little is known about metastasis-to-metastasis seeding. Current preclinical models focus on seeding from primary tumors, but cannot distinguish between additional sites of dissemination. We have recently developed an approach, termed intra-iliac artery injection (IIA), that selectively deliver cancer cells to hind limb bones via the external iliac artery (Wang et al., 2015, 2018; Yu et al., 2016). Although it skips the early steps of the metastasis cascade, it focuses on the initial seeding of tumor cells in the hind limbs, and allows the tracking of secondary metastases from bone to other organs. It is therefore a suitable model to investigate the clinical and biological roles played by bone lesions in multi-organ metastasis-to-metastasis seeding.

RESULTS

Temporally lagged multi-organ metastases in mice carrying IIA-introduced bone lesions of breast and prostate cancers

IIA injection has been employed to investigate early-stage bone colonization. Both aggressive (e.g., MDA-MB-231) and relatively indolent (e.g. MCF7) breast cancer cells can colonize bones albeit following different kinetics. In both cases, cancer cell distribution is highly bone-specific at early time points, allowing us to dissect cancer-bone interactions without the confounding effects of tumor burden in other organs (Figure 1A) (Wang et al., 2015, 2018). However, as bone lesions progress, metastases, as indicated by bioluminescence signals, begin to appear in other organs, including additional bones, lungs, liver, kidney, and brain, usually 4-8 weeks after IIA injection of MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 1B). Bioluminescence imaging provides sufficient sensitivity to detect metastases (Deroose et al., 2007). However, many factors such as lesion depth and optical properties of tissues may influence signal penetration. Thus, we used a number of other approaches to validate the presence of metastases in multiple types of tissues. These include positron emission tomography (PET) (Figure 1C), micro computed tomography (μCT) (Figure 1C and S1A), whole-tissue two-photon imaging (Figure S1B), immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1D and 1E), and histological staining (H&E) (Figure S1C). Compared to bioluminescence imaging, these approaches provided independent evidence, but are either less sensitive or non-quantitative (Deroose et al., 2007) (Figure S1A). Therefore, we also used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect human-specific DNA in dissected mouse tissues and confirmed that qPCR results and bioluminescence signal intensity values are highly correlative (Figure S1D and S1E). Of note, the spectrum of metastases covers multiple other bones (Figure 1D) and soft-tissue organs (Figure 1E). Taken together, our data support occurrence of multi-organ metastases in animals with IIA-introduced bone lesions.

Figure 1. Multi-organ metastases in mice with bone lesions.

(A) Diagram of intra-iliac artery (IIA) injection and representative bioluminescent images (BLI) showing the in vivo distribution of tumor cells after IIA injection of 1E5 MDA-MB-231 fLuc-mRFP cells. .

(B-C) Representative ex vivo BLI images (B), and PET-μCT (C) on hindlimbs and other tissues of the same animal with MDA-MB-231 cells inoculated in the right hindlimb after 8 weeks. R.H, Right Hindlimb; Lu, Lung; L.H, Left Hindlimb; Li, Liver; Ki, Kidney; Sp, Spleen; Br, Brain; Ve, Vertebrae; F.L, Forelimbs; Ri, Ribs; St, Sternum; Cr, Cranium.

(D-E) Representative immunofluorescent images of tumor lesions in various bones (D) and other organs (E). To obtain complete views of entire organs, smaller fields were acquired in tiles by mosaic scanning and then stitched by Zen. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(F-H) Representative BLI images of animals and tissues after IIA injection of 2E5 prostate cancer cells PC3 (F), 1E5 ER+ breast cancer cells MCF7 (G), and 1E5 murine mammary carcinoma cells AT-3 (H) at the indicated time.

(I) Diagram of intra-femoral injection (IF) (Left) and representative ex vivo BLI images of tissues from animals received 1E5 MDA-MB-231 cells (Middle) or AT-3 cells (Right) via IF injection.

(J-K) Heat map of ex vivo BLI intensity and status of metastatic involvement on various types of tissues from animals carried MDA-MB-231 (J) and AT-3 (K) bone tumors. Columns, individual animal; rows, various tissues or status of multi-site metastases; Gray, no detectable lesion. N (# of mice): MDA-MB-231, 16 (IIA), 11 (IF); AT-3, 10 (IIA), 10 (IF). P values were assessed by Fisher’s exact test on the ratio of metastasis while by Mann-Whitney test on the tumor burden. See also Figure S1.

This phenomenon is not specific for the highly invasive MDA-MB-231 cells, but was also observed in more indolent MCF7 cells and PC3 prostate cancer cells, as well as murine mammary carcinoma AT-3 cells in immunocompetent mice, albeit after a longer lag period for PC3 cells (8-12 weeks) (Figure 1F-H and S1F).

As an independent approach to introduce bone lesions, we used intra-femoral (IF) injection that delivers cancer cells directly to bone marrow, bypassing the artery circulation involved in IIA injection. This approach also resulted in multi-organ metastases at late time points in both MDA-MB-231 and AT-3 models (Figure 1I and S1G). The frequency and distribution patterns of metastases were similar between intra-femoral and IIA injection models (Figure 1J and 1K). Thus, we hypothesize cancer cells in the bone microenvironment may gain capacity to further metastasize.

Bone lesions more readily give rise to multi-organ metastasis

The later-appearing multi-organ metastases may result from further dissemination of cancer cells in the initial bone lesions. Alternatively, they could also arise from cancer cells that leaked and escaped from bone capillaries during IIA or IF injection. In the latter case, the leaked cancer cells would enter the iliac vein and subsequently arrive in the lung capillaries. Indeed, there did appear to be bioluminescence signals in the lungs upon IIA injection (Figure 1A). To distinguish these probabilities, we performed intra-iliac vein (IIV) injection and compared the results to those of IIA injection at late time points. The IIV injection procedure should mimic the “leakage” from IIA injection, although this would allow many more cells to enter the venous system and be arrested in the lung capillaries (Figure 2A and S2A-C, compared to Figure 1A). As another relevant comparison, we also examined metastasis from orthotopic tumors transplanted into mammary fat pad (MFP) (Figure 2B, S2A-B and S2D). Furthermore, in the case of ER+ cells, recent studies suggest that intra-ductal injection provides a more “luminal” microenvironment and may promote spontaneous metastasis to other organs (Sflomos et al., 2016). As a result, specifically for MCF7 cells, the only ER+ cancer model used in our study, we also included mouse intra-ductal (MIND) injection as an additional model. In all experiments, we used total bioluminescence signal intensity to evaluate tumor burdens at hind limbs (IIA and IF), lungs (IIV) and mammary fat pads (MFP and MIND), respectively. We attempted to assess multi-organ metastasis when the “primary lesions” reach a comparable level of bioluminescent intensity, simply to rule out the source tumor burden as a confounding factor in our comparisons. This was feasible for some models such as mammary tumors and bone lesions derived from MCF7 (Figure S2E). However, in other models, mammary tumors tend to grow much faster compared to lesions growing in other sites (Figure S2F and S2G). Therefore, we chose to end experiments at the same time point for all conditions. In all experiments, multi-organ metastases were examined well before animals became moribund. Taken together, we set to ask if secondary metastasis from bone lesions follows a faster kinetics and reaches a wider spectrum of target organs as compared to that from orthotopic tumors or lungs.

Figure 2. Bone microenvironment promotes further metastasis.

(A) Diagram of intra-iliac vein (IIV) injection, and representative BLI images of animals and tissues 8 weeks after IIV injection of 1E5 MDA-MB-231 cells.

(B) Diagram of mammary fat pad (MFP) implantation, and representative BLI images of animals and tissues 8 weeks after MFP implantation of 1E5 MDA-MB-231 cells.

(C-D) Comparison of metastatic pattern and tumor burden (C) and the ratio of multi-site metastasis (D) in animals with bone (IIA/IF), lung (IIV) or mammary (MFP) tumors of MDA-MB-231 cells. N (# of mice) = 27 (Bone); 18 (MFP); 10 (Lung).

(E-F) Comparison of metastatic pattern and tumor burden (E) and the ratio of multi-site metastasis (F) in animals with bone (IIA/IF), lung (IIV) or mammary (MFP) tumors of AT-3 cells. N (# of mice) = 20 (Bone); 11 (MFP); 9 (Lung).

(G-H) Comparison of metastatic pattern and tumor burden (G) and the ratio of multi-site metastasis (H) in animals with bone (IIA), lung (IIV) or mammary (MFP or MIND) tumors of MCF7 cells. N (# of mice) = 8 (Bone); 10 (MFP); 13 (MIND); 9 (Lung).

P values were assessed by Chi-square test in C-H on the ratio of metastasis; by uncorrected Dunn’s test following Kruskal-Wallis test in C, E and H on the tumor burden. See also Figure S2.

Strikingly, the answer to this question is evidently positive in all three tumor models examined (Figure 2C-2H). We assessed 11 organs including six other bones and five soft tissue organs for metastasis. Curiously, in many cases, counter-lateral hind limbs (designated as “L.Hindlimb” for “left hind limb” as the initial bone lesions were introduced to the right hind limb) are most frequently affected among all organs in IIA models. Lungs are also frequently affected in MDA-MB-231 and AT-3 models, by metastasis from both bone lesions and orthotopic tumors. However, it is striking to note that lung metastasis in IIA and IF models is comparable or even more severe as compared to that in IIV models, despite the fact that IIV injection delivers more cancer cells directly to lungs (Figure S2H). In fact, the normalized increase of tumor burden at lungs through IIA and IF are at least 10-fold more than that through IIV injection (e.g., Figure S2H), which strongly argue that bone microenvironment promotes secondary metastasis.

Cross-seeding of cancer cells from bone lesions to orthotopic tumors

Cancer cells may enter circulation and seed other tumor lesions or re-seed the original tumors (Kim et al., 2009). By using MDA-MB-231 cells tagged with different fluorescent proteins, we asked if bone lesions can cross-seed mammary tumors (Figure 3A). Interestingly, we observed that while orthotopic tumors can be readily seeded by cells derived from bone lesions, the reverse seeding rarely occurs (Figure 3B and 3C). This difference again highlights the enhanced metastatic aggressiveness of cancer cells in the bone microenvironment.

Figure 3. Cross-seeding and parabiosis experiments support the promoting effects of bone microenvironment on further dissemination.

(A) Experimental design of cross-seeding experiment between mammary and bone tumors of mRFP or EGFP tagged MDA-MB-231 cells. Upper, mRFP (IIA), EGFP (MFP); lower, EGFP (IIA), mRFP (MFP).

(B) Representative confocal images showing the cross-seeding between bone and mammary tumors. Scale bar, 20 μm. N (# of mice) = 5 for each arm.

(C) Incidence of cross-seeding between bone and mammary tumors.

(D) Experimental design of parabiosis models to compare the metastatic capacity of bone and mammary tumors. N (# of mice) = 17 (BoM); 19 (MFP).

(E) Representative BLI images of metastatic lesions in recipient mice parabiotic with mice bearing bone metastases.

(F) Ratio of recipients with metastasis in bone and mammary tumor groups, as determined by BLI imaging.

(G)Representative immunofluorescent images on tissues from recipients of bone tumor group. To obtain complete views of entire organs, smaller fields were acquired in tiles by mosaic scanning and then stitched by Zen. Scale bar, 20 μm. Tissues from 6 animals were examined.

P value was assessed by Fisher’s exact test in C and F. See also Figure S3.

Parabiosis models support enhanced capacity of cancer cells to metastasize from bone to other organs

It is possible that IIA injection disturbs bone marrow and stimulates systemic effects that allow multi-organ metastases. For example, the injection might cause a transient efflux of bone marrow cells that can arrive at the distant organ to form pre-metastatic niche. To test this possibility, we used parabiosis to fuse the circulation between a bone lesion-carrying mouse (donor) and tumor-free mouse (recipient) one week after IIA injection. In parallel, we also performed parabiosis on donors that have received MFP injection and tumor-free recipients (Figure 3D). After seven weeks, surgical separation was performed to allow time for metastasis development in the recipients. Subsequently, the organs of originally tumor-free recipients were collected and examined for metastases four months later. Only ~20% of recipients in the IIA group were found to harbor cancer cells in various organs (Figure 3E and 3F), mostly as microscopic disseminated tumor cells (Figure 3G), indicating that the fusion of circulation system is not efficient for metastatic seeds to cross over from donor to recipient. However, in the MFP comparison group, no metastatic cells were detected (Figure 3F, S3A, and S3B), and the difference is statistically significant. Therefore, the parabiosis data also support the hypothesis that the bone microenvironment invigorates further metastasis, and this effect is unlikely to be due to IIA injection-related systemic influence.

An evolving barcode system revealed the phylogenetic relationships between initial bone lesions and secondary metastases

Barcoding has become widely used to elucidate clonal evolution in tumor progression and therapies. An evolving barcoding system has recently been invented for multiple parallel lineage tracing (Kalhor et al., 2017, 2018). It is based on CRISPR/Cas9 system but utilizes guide RNAs that are adjacent to specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) in their genomic locus, thereby allowing Cas9 to mutate its own guide RNAs. These variant guide RNAs are named homing guide RNAs (hgRNAs). When Cas9 is inducibly expressed, hgRNA sequences will randomly drift, serving as evolving barcodes (Figure 4A). A preliminary in vitro experiment demonstrated that the diversity of barcodes (measured as Shannon entropy) is a function of duration of Cas9 expression (Figure 4B and S4A).

Figure 4. In vivo barcoding of spontaneous metastases with hgRNAs.

(A) Principle of the evolving barcode system comprised of hgRNAs and inducible Crispr-Cas9.

(B) Ratio of unmutated barcode and Shannon entropy in MDA-MB-231 cells upon multiple rounds of doxycycline treatment in vitro.

(C) Schematics showing the rationale of using evolving barcodes to infer the evolution of metastatic lesions and the timing of seeding events. Barcode diversity decreases during the seeding process. Children metastases inherit a subset of signature barcodes from parental tumors. Upon Cas9 activation, barcodes start evolving and regain diversity. Diversity of barcodes can therefore infer the relative timing of seeding, and phylogenetically related metastases share a subset of signature barcodes.

(D-E) Design of in vivo barcoding experiment (D) and representative BLI images (E) of metastatic lesions from MDA-MB-231 tumors.

(F) Feature matrix of mutation events in MDA-MB-231 metastatic samples. See also Figure S4 and Supplementary Table 1.

We introduced this system into MDA-MB-231 and AT-3 cells, and transplanted them into mammary fat pads of nude and wild-type C57BL/6 mice, respectively. When orthotopic tumors reach 1 cm3, we resected the tumors and induced Cas9 by doxycycline. It should be noted that the orthotopic tumors already harbored a high diversity of mutant barcodes presumably due to leakage of Cas9 expression. This served as an initial barcode repertoire that enabled us to distinguish distinct clones that metastasize from orthotopic tumors to various organs. Further Cas9 expression yielded new mutations for delineation of parent-child relationship among lesions (Figure 4C). We rationalize that the diversity of barcodes, or the Shannon entropy, in a metastasis should reflect the “age” of metastasis. When secondary metastasis occurs, child metastases will inherit only a subset of barcodes causing a reduction of Shannon entropy. Therefore, among genetically related metastases indicated by sharing common mutant barcodes, those with higher Shannon entropy are more likely to be parental (Figure 4C). This can be supported by the observation that primary bone lesions possess higher entropy than those secondary metastases in IIA model (Figure S4B).

We isolated 29, 32, 9, and 17 metastases from two mice bearing MDA-MB-231 and two mice bearing AT3 tumors, respectively (Figure 4D-E, S4C and Supplementary Table 1). Sequencing of the barcodes carried by these metastases in combination of the analysis of the timing of seeding as indicated by the Shannon entropy of barcodes led to profound findings. First, in line with a previous study (Echeverria et al., 2018), multi-organ metastases are not genetically grouped according to sites of metastases at the terminal stage (Figure 4F and S4D). Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF) analysis of mutant barcodes suggested the early disseminated metastases, which have the highest level of Shannon entropy, were featured with a common cluster of mutant barcodes irrespective of their locations, especially in AT-3 models (Figure 5A-C and S5A-C). This is evidence against organotropism in the late stage of metastatic progression in mouse models. Second, most metastases are potentially multiclonal as indicated by multiple clusters of independent mutant barcodes (Figure 5C and S5C). Third, putative parent-child relationship between metastases with unique mutant barcodes clearly exemplified secondary metastatic seeding from bone to other distant sites (Figure 5D and S5D) in both models. Finally, we did not observe a clear correlation between tumor burden and Shannon entropy across different metastases, and the putative funder metastases can be small in tumor burden while diversified in barcode composition, suggesting that asymptomatic metastases might also seed further metastases (Figure 5E and S5E). Taken together, these data reveal potential wide-spread metastasis-to-metastasis seeding and support that secondary metastases from the bone to other distant organs happen in a natural metastatic cascade.

Figure 5. NMF analysis of evolving barcodes delineates metastatic spread.

(A-B) Plots of NMF rank survey, consensus matrix, basis components matrix and mixture coefficients matrix of 200 NMF runs on the barcodes from MDA-MB-231 metastatic lesions.

(C) Body map depicting the basis composition of MDA-MB-231 metastatic lesions.

(D) Chord diagrams illustrating the composition flow of barcode mutations between primary tumors and selected MDA-MB-231 metastatic lesions.

(E) Correlation plot of Shannon entropy and tumor burden on MDA-MB-231 samples. The tumor burden was indicated by human genomic content determined by q-PCR. Spearman r and p value was indicated. See also Figure S5.

The bone microenvironment promotes further metastasis by enhancing cancer cell stemness and plasticity

Organotropism is an important feature of metastasis. Clonal selection appears to play an important role in organ-specific metastasis, which has been intensively studied (Bos et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2003; Minn et al., 2005; Vanharanta and Massague, 2013). Herein, the metastasis-promoting effects of the bone microenvironment appear to be multi-organ and do not show specific organ-tropism. In an accompanied study, we discovered profound phenotypic shift of ER+ breast cancer cells in the bone microenvironment, which included loss of luminal features and gain of stem cell-like properties (Bado et al., 2021). This shift is expected to promote further metastases (Gupta et al., 2019; Ye and Weinberg, 2015). Therefore, we hypothesize that the enhancement of metastasis may be partly through an epigenomic dedifferentiation process.

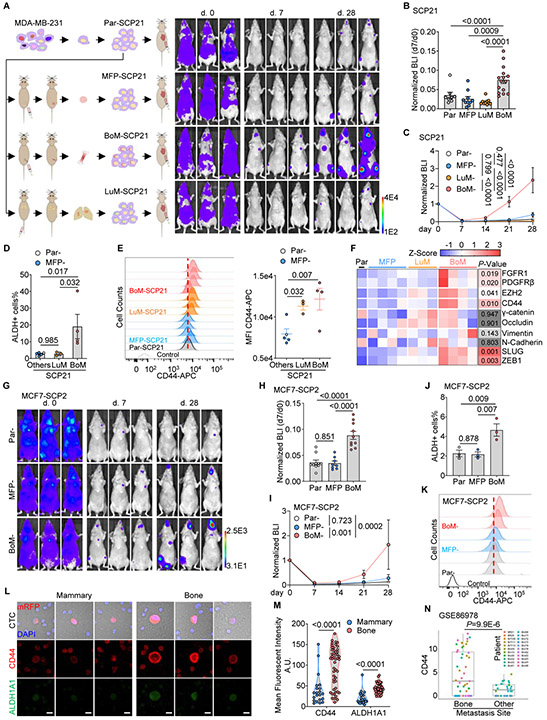

To test this possibility, we compared the metastasis capacity of a genetically identical SCP of MDA-MB-231 cells and its derivatives entrained by different microenvironments (Figure S6A and S6B). Based on a previous study (Minn et al., 2005), we picked a non-metastatic SCP termed SCP21. SCP21 cells were introduced to mammary fat pads, lungs, and hind limb bones to establish tumors. After 6 weeks, entrained cancer cells were extracted from these organs for further experiments (Figure 6A). We used intra-cardiac injection to simultaneously deliver cancer cells to multiple organs (Figure 6A). Compared to the mammary fat pad- and lung-entrained counterparts, bone-entrained SCP21 was more capable of colonizing distant organs and gave rise to much higher tumor burden in multiple sites as determined by bioluminescence (Figure 6A-6C). In mice subjected to dissection and ex vivo bioluminescent imaging, significantly more and bigger lesions were observed from mice received bone-entrained SCP21 cells in both skeletal and visceral tissues (Figure S6C-E), suggesting an increase of overall metastatic capacity rather than bone tropism in tumor cells exposed to bone environment.

Figure 6. Bone-entraining boosts the metastatic capacity of single cell-derived cancer cells.

(A) Experimental design (left) and representative BLI images (right) to test the metastatic capacity of mammary, lung, or bone-entrained SCP21s.

(B) Normalized whole-body BLI intensity 7 days after intra-cardiac (IC) injection of same number of MFP-, LuM-, BoM- or Par-SCP21 cells.

(C) Colonization kinetics of MFP-, LuM-, BoM- and Par-SCP21 cells after IC injection. N (# of mice) = 8 (Par); 10 (MFP); 15 (BoM); 10 (LuM).

(D) Percentage of ALDH+ population in MFP-, LuM-, BoM- and Par-SCP21 cells by flow cytometry.

(E) Histogram (left) and median fluorescent intensity (MFI) (right) of surface CD44 protein in MFP-, LuM-, BoM- and Par-SCP21 cells by flow cytometry.

(F) Expression levels of proteins in Par- and organ-entrained SCP21s. Protein levels were quantified and converted into Z-score from three or four western blottings.

(G-I) Representative BLI images (G), normalized BLI intensity at day 7 (H), and the colonization kinetics (I) of MFP-, BoM-, and Par- MCF7-SCP2 cells after I.C. injection. N (# of mice) = 10 (Par); 8 (MFP); 10 (BoM).

(J-K) Percentage of ALDH+ population (J) and expression of surface CD44 (K) in MFP-, BoM-, and Par- MCF7-SCP2 cells by flow cytometry. N (# of repeats) = 3 (J); 2 (K).

(L-M) Representative fluorescent images (L) and quantification (M) of CD44 and ALDH1A1 expression on CTCs from NRG mice bearing MDA-MB-231 cells derived mammary or bone tumors. CTCs were pooled from 5 blood samples. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(N) Expression levels of CD44 mRNA in CTCs from breast cancer patients with bone metastases or other metastases (GSE86978).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM in B, C, D, E, H, I and J. P values were assessed by Fisher’s LSD test following one-way ANOVA test in B, D, E, H, and J; by Fisher’s LSD test post two-way ANOVA test in C and I; by student t-test in F; by Mann-Whitney test in M and N. See also Figure S6.

Inspired by the accompanied study (Bado et al., 2021), we examined stemness markers (Al-Hajj et al., 2003; Charafe-Jauffret et al., 2009) of SCP21 cells entrained in different microenvironments. Interestingly, bone-entrained cells appeared to express a higher level of both ALDH1 activity and CD44 expression (Figure 6D and 6E). In addition, bone-entrained SCP21 cells increased expression of multiple proteins involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and in pathways shown to mediate the effects of bone microenvironment on ER+ cancer cells in our accompanied study, including FGFR1, PDGFRβ, EZH2, SLUG, and ZEB1 (Figure 6F and S6F). These data suggest that similar mechanisms may be at work to induce cancer cell stemness and plasticity in this ER− model.

Indeed, when the same approaches were applied to the SCP2 derivatives of MCF7 cells. Bone entrained MCF7-SCP2 cells showed increased initial survival and faster metastatic growth after intra-cardiac injection (Figure 6G-6I) and increased level of ALDH1 activity and CD44 expression (Figure 6J and 6K). In this epithelial model, we also observed a hybrid EMT phenotype (Figure S6G), as also elaborated in our associated study (Bado et al., 2021). It should be noted that, in this series of experiments, lung-derived subline was not developed due to the lack of lung colonization for MCF7-SCP2 cells.

In addition to cancer cells that are manually extracted from various organs, we examined naturally occurred circulating tumor cells (CTCs) emitted from bone lesions versus mammary tumors. Not surprisingly, bone lesions generated a higher number of CTCs, probably due to the more permeable vascular structures or survival advantage conferred by the bone. However, on top of the higher number, CTCs from bone lesions also express higher quantity of CD44 and ALDH1 (Figure 6L and 6M), suggesting increased stemness.

Finally, we also interrogated CD44 expression in a single-cell RNA-seq dataset of CTCs derived from breast cancer patients. When patients were divided into two groups – those carrying bone metastasis versus those carrying other metastases, significantly higher expression of CD44 was observed in the former (Figure 6N) (Aceto et al., 2018), providing clinical support for our hypothesis that the bone microenvironment promotes tumor cell stemness and plasticity, and thereby invigorate further metastasis.

EZH2 in cancer cells orchestrates the effect of bone microenvironment in secondary metastasis

Since EZH2 was revealed to play a central role in loss of ER and gain of plasticity in ER+ models in the accompanied study (Bado et al., 2021), we asked if it also mediates secondary metastasis. The frequency of ALDH1+ cells and the expression of mesenchymal and stemness markers in bone-entrained SCP21 cells were also significantly decreased upon treatment of an EZH2 inhibitor (EPZ) used in our accompanied study (Figure S7A-C), supporting EZH2 as an upstream regulator the observed phenotypic shift.

In addition to expression, we used an EZH2 target gene signature (Lu et al., 2010) to deduce EZH2 activities. This signature was then applied to RNA-seq transcriptomic profiling of SCP21 cells subjected to various treatments or entrained in different organs. EPZ treatment relieved the suppression of signature genes, resulting in higher expression (Figure S7D), which supported the validity of the signature. We then compared cells entrained in bone lesions versus mammary gland tumors or lung metastasis and observed significantly higher EZH2 activity in the bone (Figure 7A). Importantly, bone-induced changes to both EZH2 activity and frequency of ALDH1+ cells appeared to be reversible, as in vitro passages led to progressive loss of these traits (Figure 7B and 7C). Other bone microenvironment-induced factors upstream of EZH2 (e.g., FGFR1 and PDGFRβ) (Kottakis et al., 2011; Yue et al., 2019) also exhibited transient increased expression in bone-entrained cells (Figure 7D and S7E). Taken together, these data further suggest the potential role of EZH2 in secondary metastasis from bone lesions.

Figure 7. Secondary metastasis from bone lesions is dependent on EZH2 mediated epigenomic reprograming.

(A) Levels of EZH2 signature genes (GSVA) in bone entrained and other SCP21 cells.

(B) Levels of EZH2 signature genes in bone entrained-SCP21 cells after different passages in vitro.

(C) Percentage of ALDH1+ population in bone entrained-SCP21 cells at different passages.

(D) Representative western blotting of proteins in bone entrained-SCP21 cells after different passages.

(E-G) The schematic diagram and representative BLI images (E), normalized BLI intensity at day 7 (F), and the colonization kinetics (G) of BoM-SCP21 cells with in vitro EPZ011989 (EPZ) treatment before IC injection. Non-treated BoM-SCP21 cells were used as control. N (# of mice) = 15 (-EPZ); 9 (+EPZ).

(H) Comparison of ALDH1+ cells in EPZ treated and non-treated BoM-MCF7-SCP2 cells by flow cytometry. N (# of replicate) =3.

(I-K) Representative BLI images (I), normalized BLI intensity at day 7 (J), and the colonization kinetics (K) of BoM-MCF7-SCP2 cells with in vitro treatment of EPZ before IC injection. Non-treated BoM-MCF7-SCP2 cells were used as control. N (# of mice) = 10 (-EPZ); 7 (+EPZ).

(L) Experimental design assessing the multi-site metastases from bone lesions with inducible depletion of EZH2.

(M) Growth kinetics of the primary bone lesions in mice receiving doxycycline or control water, assessed by in vivo BLI imaging. BLI intensities at right hindlimbs were normalized to the mean intensity at day 0. N (# of mice) = 10 for each arm.

(N) Heat map of ex vivo BLI intensity and status of metastatic involvement in tissues from animals with EZH2 depleted or control bone metastases.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM in F, G, J, K, and M. P values were assessed by student t-test in A, F, and J; by test for linear trend following repeat measure one-way ANOVA in B and C; by LSD test following two-way ANOVA in G, K and M; by ratio paired t-test in H; by Fisher’s exact test on the ratio of metastatic involvement and Mann-Whitney test on BLI intensity in N. See also Figure S7.

Remarkably, transient treatment of EPZ before intra-cardiac injection, which did not suppress the growth of tumor cells in vitro (Figure S7F), completely abolished the enhanced metastasis of bone-entrained SCP21 cells (Figure 7E-7G) and MCF7-SCP2 cells (Figure 7H-7K) in vivo, again demonstrating that the observed effects of bone microenvironment is not through clonal selection, but rather epigenomic reprogramming driven by EZH2.

Finally, to confirm the cancer cell-intrinsic role of EZH2 during this process, we generated inducible knockdown of EZH2 (Figure S7G), that also slightly affected downstream expression of plasticity factors and stem cell markers (Figure S7G-H), but did not alter cancer cell growth rate in vitro (Figure S7I). Induction of knockdown was initiated after bone lesions were introduced for one week (Figure 7L, and S7J). Interestingly, whereas EZH2 knockdown did not alter primary bone lesion development (Figure 7M), it dramatically reduced secondary metastasis to other organs (Figure 7N). Taken together, these aforementioned results strongly implicate EZH2 as a master regulator of secondary metastases from bone lesions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, based on the IIA injection technique and through multiple independent approaches, we demonstrated that the bone microenvironment not only permits cancer cells to further disseminate but also appears to augment this process. A key question that remains is the timing of secondary metastasis spread out of the initial bone lesions: whether this occurs before or after the bone lesions become symptomatic and clinically detectable. The answer will determine if therapeutic interventions should be implemented in adjuvant or metastatic settings, respectively. Moreover, if further seeding occurs before bone lesions become overt, it raises the possibility that metastases in other organs might arise from asymptomatic bone metastases, which might warrant further investigations. Indeed, it has been reported that DTCs in bone marrow of early breast cancer patients enrich stem cell-like population (Alix-Panabières et al., 2007; Balic et al., 2006), supporting that asymptomatic bone micrometastases are potentially capable of metastasizing before being diagnosed. In this study, our evolving barcode strategy exemplified potential metastases from bone to other organs. Interestingly, we found that the putative parental metastases could remain small (Figure 5E and S5E), which may suggest that further dissemination might occur before diagnosis of existing lesions. Future studies will be needed to precisely determine the onset of secondary metastasis from bones.

The fact that the genetically homogenous SCP cells became more metastatic after lodging into the bone microenvironment suggests a mechanism distinct from genetic selection. Remarkably, this phenotype persists even after in vitro expansion, so it is relatively stable and suggests an epigenomic reprogramming process. We propose that this epigenetic mechanism may act in concert with the genetic selection process. Specifically, the organ-specific metastatic traits may pre-exist in cancer cell populations (Minn et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2013) and determine the first site of metastatic seeding. The epigenomic alterations will then occur once interactions with specific microenvironment niches are established and when cancer cells become exposed chronically to the foreign milieu of distant organs. Our data suggest that such alterations drive a second wave of metastases in a less organ-specific manner. This may explain why terminal stage of breast cancer is often associated with multiple metastases (DiSibio and French, 2008).

Here we suggested that the enhanced EZH2 activity underpins the epigenetic reprograming of tumor cells in bone microenvironment for further metastases. EZH2 maintains the dedifferentiated and stem cell-like status of breast cancer cells by repressing the lineage-specific transcriptional programs (Chang et al., 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2014). Pharmacologically or genetically targeting EZH2 has been reported to inhibit tumor growth, therapeutic resistance and metastases with different efficacies in preclinical models (Hirukawa et al., 2018; Ku et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). It was noted that in our models, EZH2 inhibition could not suppress the cell growth in vitro or in the primary injection site, whereas both the transient treatment of EZH2 inhibitor or inducible knock-down of EZH2 in cancer cells dramatically decreased secondary metastasis, suggesting targeting EZH2 may block the metastatic spread rather than the tumor growth.

In the clinic, some bone metastases can be managed for years without further progression, while others quickly develop therapeutic resistance and are associated with subsequent metastases in other organs (Coleman, 2006). These different behaviors may suggest different subtypes of cancers that are yet to be characterized and distinguished. Alternatively, there may be a transition between these phenotypes. In fact, depending on different interaction partners, the same cancer cells may exist in different status in the bone. For instance, while endothelial cells may keep cancer cells in dormancy (Ghajar et al., 2013; Price et al., 2016), osteogenic cells promote their proliferation and progression toward micrometastases (Wang et al., 2015, 2018). Therefore, it is possible that the transition from indolent to aggressive behaviors is underpinned by an alteration of specific microenvironment niches. Detailed analyses of such alteration will lead to unprecedented insights into the metastatic progression.

Limitations of the Study

In this study, we did not provide direct clinical evidence that bone metastasis can seed other metastases in cancer patients. Although this is reported in several previous studies (Brown et al., 2017; Gundem et al., 2015; Ullah et al., 2018b), the prevalence of secondary metastases seeded from bone lesions remains to be determined in patients. Future genomic studies with improved depth and informatics will likely dissect this process in greater depth and elucidate spatiotemporal paths of metastasis. The evolving barcode strategy was useful in tracing metastatic evolution. The most striking and robust finding from these experiments is that genetically closely-related metastases do not localize in the same type of tissues and are usually highly distinct from orthotopic tumors. This in principle argues against independent seeding events from primary tumors and supports metastasis-to-metastasis seeding. However, the deduction of specific parental-child relationship based on Shannon entropy is intuitive and qualitative, and needs to be analyzed by more quantitative models in future work.

We principally demonstrated that compared to lungs, bones are more capable of promoting secondary metastasis. However, further studies will be required to determine whether other organs, such as liver and lymph nodes, might also exert similar effects on metastatic spread. We postulate that two factors may regulate an organ’s capacity to promote secondary metastases. First, the initial wave of orgnotropic metastasis will pose a selection of metastatic seeds that arrive and survive in a specific organ. Second, the subsequent interactions with resident cells will induce adaptive epigenetic changes on top of the genetic selection, which together dictate whether the metastatic journey may extend to other organs.

Although data presented in this study indicate that cancer cells colonizing the bone acquire intrinsic traits for further dissemination, we cannot rule out systemic effects that may also contribute to this process. At the late stage, bone metastases are known to cause strong systemic abnormality such as cachexia (Waning et al., 2015), which may influence secondary metastasis. Even at early stages before bone metastases stimulate severe symptoms, the disturbance of micrometastases to hematopoietic cell niches may mobilize certain blood cells to migrate to distant organs, which may in turn result in altered metastatic behaviors (Peinado et al., 2017). These possibilities will need to be tested in future research.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources or reagents should be directed to the lead contact Dr. Xiang H.-F. Zhang (xiangz@bcm.edu).

Materials Availability

Plasmids and cells generated in this study are available upon requests with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement (MTA). There are restrictions to the availability of EPZ011989 due to the restriction of MTA with Epizyme.

Data and Code Availability

The raw data of mRNA sequencing, WES sequencing and barcode sequencing are available in NIH Gene Expression Omnibus with the accession number GSE160773, GSE161181 and GSE161145. The GEO reference series GSE161146 links all the datasets. The TraceQC package can be found at https://github.com/LiuzLab/TraceQC. The code for the NMF analysis of barcodes can be found at https://github.com/LiuzLab/CRISPR_bone_metastasis-manuscript.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines and Cell Culture

Human triple negative breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231(RRID: CVCL_0062), human estrogen receptor positive luminal breast cancer cell line MCF7 (RRID: CVCL_0031), human prostate cancer cell line PC-3 (RRID: CVCL_0035), and HEK293T cells (RRID: CVCL_0063) were obtained from ATCC. AT-3 cells (RRID: CVCL_VR89) was a gift from Dr. Scott Abrams at Roswell Park Cancer Center. SCP21 cells were from Joan Massague lab. MCF7 SCPs were generated from single cells of parental MCF7 cells in the lab. All cells were maintained in DMEM high glucose media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in 5% CO2 37°C incubator. MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and their derivative cells were authenticated by the Cytogenetics and Cell Authentication Core at MD Anderson Cancer Center by STR profiling. The mycoplasma contamination was routinely examined in the lab using PlasmoTest™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (InvivoGen) and no contamination was detected in the cells used in this study. Incucyte (Essen BioScience) was used to assess the cell growth in culture.

Animals

The in vivo studies were covered by and conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Nude mice [Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu] were purchased from Envigo, while female C57BL/6J (RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664) and immunodeficient NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1Mom Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (RRID: IMSR_JAX:007799) mice were from Jackson Laboratories. Age-matched female or male mice of 6- to 8-week-old were used for breast cancer cells, or prostate cancer cells, respectively. In tumor models using MCF7 and MCF7-SCP2 cells, slow-released estradiol tubes were implanted under the dorsal neck skin of animals one week prior the tumor implantation. 2 weeks after arrival, mice were randomly allocated to experimental groups.

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmid Construction

TLCV2 plasmid was a gift from Adam Karpf (Addgene plasmid # 87360)(Barger et al., 2019). To construct the TLCV2-hgRNA-A26 plasmid, the synthesized hgRNA-A26 oligos were annealed and ligated with BsmBI and EcoRI digested TLCV2 plasmid. The TRIPZ inducible EZH2 shRNA plasmids (Clone ID: V2THS_63066 and V2THS_63067) were purchased from Horizon Discovery Ltd. Plasmids were extracted from the growing bacterial clones and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The oligo sequences are listed in the Supplementary Table 2.

Lentiviral Production and Transduction

Luciferase/fluorescent protein reporter plasmids, or TRIPZ-shEZH2, or TLCV2-hgRNA-A26 were transfected together with psPAX2 and pMD2.G packaging plasmids into HEK293T cells using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Sigma). 48 hours later, the supernatant was harvested and filtered by 0.45 um filter (VWR International). Cancer cells were transduced by the fresh lentivirus together with 8ug/ml polybrene (Sigma). Two days later, GFP/mRFP positive cells were sorted to generate reporter cell lines. For cells with inducible evolving barcodes or shEZH2, cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin for 10 days before experiments.

In vitro activation of hgRNA barcodes

5E5 barcoded MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded on the 10-cm dish and the next day treated with 100μg/ml doxycycline for 2 hours. Cells were then rinsed by PBS three times to completely remove doxycycline and then allowed to grow in vitro for 4 days. 1 million cells were collected for barcode sequencing and 0.5 million cells were re-cultured and received next round of doxycycline treatment 24 hours later.

Intra-iliac artery and Intra-iliac vein Injection

Both intra-iliac artery and vein injections were performed as previously described (Yu et al., 2016). Briefly, animals were anesthetized and restrained on a warming pad. The surgery area was sterilized, and a 7-8 mm incision was made between the right hind limb and abdomen to expose the common iliac vessels. Cancer cells were suspended in 100μl PBS and injected to the iliac artery or vein by 31G insulin syringe (Becton Dickinson) to generate bone or lung metastases, respectively. For inducible knockdown of EZH2 in vivo, animals were randomly separated into two groups, and given 0.2 mg/ml doxycycline in 1% sucrose water or vehicle for 7 weeks one week after the injection, respectively.

Intra-femoral and Intra-Cardiac Injection

For intra-femoral injection, a port through the right femoral plateau was made by a 28G syringe needle into the bone marrow cavity. Then, cancer cells in 20 μl PBS was slowly delivered into the bone marrow cavity through the port. The syringe was then hold for about 20 seconds to allow the equilibrium of bone marrow before retrieval. For intra-cardiac injection, cancer cells in 100 μl PBS were directly injected into the left ventricle of anesthetized animals using 26G syringe.

Mammary Fat Pad and Intra-Ductal Injection

For mammary tumor models, cancer cells mixed 1:1 with growth factor reduced Matrigel Matrix (Corning) were orthotopically implanted into the fourth mammary fat pad of mice. In the cross-seeding experiment, the mammary tumors were implanted on the opposite side of mammary fat pad immediately after the IIA injection of same number of cancer cells in the right hind limb on the same animal. The intra-ductal injection (or MIND model) was performed as previously reported (Nguyen et al., 2000). Briefly, the tip of the fourth nipples was cut off and cancer cells in 10 ul PBS were directly injected into the exposed duct using 30G blunt needle fitted to a Hamilton syringe.

Parabiosis and Reverse Procedure

The procedure for parabiosis and reverse procedure were described previously (Kamran et al., 2013). Mice were housed in pairs for at least two weeks to ensure the harmonious cohabitation before the surgery. The donor mice were given a tumor implantation surgery on the right side of the body via MFP or IIA injection one week before the parabiosis surgery. During parabiosis surgery, both donor and recipient mice were anesthetized by isoflurane and placed back to back on a warming pad. A longitudinal incision was made on the left side of donor mice and right side of recipient mice starting from the elbow to the knee joints, and then the skin was gently detached from the subcutaneous fascia. The joints between parabiotic pairs were tightly connected with non-absorbable 4-0 suture. The skin incision was then closed side-by-side with absorbable 5-0 suture. The parabiotic pairs were closely monitored until full recovery. 7 weeks after the surgery, a reverse procedure was performed to separate the parabiotic pairs. The recipient mice were then continuously monitored with bioluminescent imaging bi-weekly till the detection of metastatic lesions or up-to 4 months.

In vivo activation of hgRNA barcodes

1E5 barcoded MDA-MB-231 or AT-3 cells were implanted in nude or C57BL/6 mice respectively to form mammary tumors. For MDA-MB-231 cells, 5 weeks later, the mammary tumors were completely removed, and a single dose of 5mg/kg doxycycline was then applied to the animals via I.P. injection weekly for 5 weeks. At week 12, tissues with metastatic MDA-MB-231 lesions were dissected and subjected to further analysis. The AT-3 tumors were resected 18 days after implantation, and mice were given a dose of 5mg/kg doxycycline via I.P. injection weekly. The metastatic tissues of AT-3 cells were dissected at day 42 after tumor implantation.

Bioluminescence Imaging and Tissue Collection

In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed weekly with IVIS Lumina II (Advanced Molecular Vision). Briefly, the anesthetized animals were imaged immediately after administration of 100 μl 15 mg/ml D-luciferin (Goldbio) via retro-orbital venous sinus. To ease the comparison across different animals and tissues, the exposure setting was fixed in this study except that the duration of exposure was adjusted to avoid saturation of signals. If not specified, all the animals were sacrificed 8 weeks after the tumor engraftment. At the end point, live animals were given D-Luciferin and immediately dissected. The tissues were examined by ex vivo BLI imaging following a fixed order. The whole process of dissection and ex vivo imaging was typically done in less than 15 minutes for each animal. The excised tissues were either snap frozen immediately or fixed by 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight, cryopreserved with 30% sucrose PBS solution, and then embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek). For bone tissues, a 7-day decalcification in 14% PH 7.4 EDTA solution was required before embedding. To quantify the metastatic burden, the total BLI flux was calculated over the same region of interest defined specifically for each type of tissues using Living Image software (PerkinElmer) and presented as total count/s to normalize the influence of exposure duration. The status of ‘multi-site metastases’ refers to the metastatic involvement of at least 3 tissues other than the primary site of implantation (IIA or IF, right hindlimb; IIV, lung; MFP or MIND, mammary gland). Metastatic lesions were defined as the clustered, normally distributed bioluminescent signals above the threshold of 15 counts/pixel under the maximum 120-second exposure.

Small Animal PET-CT Scanning

PET-CT scanning on tumor bearing mice was performed by the Small Animal Imaging Facility (SAIF) core at Texas Children Hospital. Briefly, animals were fasted for about 12 hours and given with Flourine-18 labeled fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) one hour before the scanning via intra-peritoneal injection (Cyclotope, Houston, TX). The scanning was performed with appropriate anesthesia and monitoring to maintain normal breathing rates of subjects. Images were acquired by an Inveon scanner (Siemens AG, Knoxville, TN). 220 CT scan projections were acquired with 290 ms exposure under 60 kVp X-ray tube voltage and 500 μA current, followed by a 30-minute PET scan. The PET scans were then reconstructed and corrected with CT scans using OSEM3D method. A thresholding of 90% of SUVmax was applied to the PET images to indicate the tumors.

Deep Imaging of Intact Tissues

Animals with metastases were retro-orbitally given 1mg 70kDa fluorescein-dextran (Invitrogen) and 10mg Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti-mouse CD31 antibody (R&D System) to label vasculatures. 10 minutes afterward, tissues with metastatic lesions were excised guiding by ex vivo BLI imaging. The dissected tissues were then cleaned with cold PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 4 hours at 4 °C. To create the window for deep imaging, part of the cortical bones was gently peeled off. Bone tissues were then decalcified at 4 °C overnight with constantly shaking. Then, tissues were equilibrated in 30% sucrose solution and later in RapiClear® 1.49 (SunJin Lab Co) overnight until the tissues became transparent. The cleared tissues were mounted with RapiClear® 1.49 and Z-stack imaging was performed with a Fluoview FV2000MPE microscope (Olympus). The vasculatures and tumor lesions were reconstructed with Imaris Viewer (Oxford Instrument).

Immunofluorescent Staining

Frozen sections and HE-stained slides were prepared by the Breast Center Pathology Core at Baylor College of Medicine. The immunofluorescent staining was performed with antibodies against mRFP (Rockland, 600-401-379), EGFP (Abcam, 13970), mouse CD31 (R&D Systems, AF3628), and mouse VE-Cadherin (R&D Systems, AF1002). Briefly, the frozen slides were warmed at room temperature for 10 minutes and rinsed with PBS twice. 50mM Ammonium chloride in PBS were applied to the slides to reduce the autofluorescence. Then the sections were penetrated with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 minutes and blocked by 10% donkey serum in PBS-GT (2% Gelatin, 0.1% TritonX-100) for 1 hour at RT. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, after PBS washing for three times, the slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated Donkey anti-Chicken IgY (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 703-546-155), Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher, A31572), and Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated Donkey anti-Goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 705-606-147) for 2 hours at RT. The stained sections were then washed, and mounted with ProLong™ Gold antifade mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher, P36935). Images were acquired by a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope, or a Leica DMi8 inverted microscope, or a Zeiss Axioscal.Z1 scanner. Immunofluorescent images were first exported by ZEN (Zeiss), or LAS X (Leica Microsystem). The exported images were then analyzed and quantified by Fiji.

Genomic DNA Extraction from Tissues and Cells

The spatially isolated metastatic lesions were excised and separated with the guide of BLI imaging. The tools were cleaned with 70% isopropanol followed by a bead-sterilizer in between different collections to avoid cross-contamination. The dissected tissues were snap-frozen and stored in −80°C freezer until next step. Samples were then homogenized with lysis buffer from Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, D4068) by Precellys Lysing Kit (Bertin Instruments, CK14 or MK28-R) on a Precellys Evolution homogenizer (Bertin Instruments). Then, the homogenized tissues or cells were incubated at 55°C for 3 h and treated with 0.33 mg/mL RNase A at 37°C for 15 min. Genomic DNA was further extracted using Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit. The final product was assessed by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) and 100 ng DNA from each sample was used in q-PCR to determine the human/mouse DNA ratio with primers specifically targeting human HPRT and mouse Gapdh gene. For the samples do not reach the threshold at the end of 40 cycles of PCR, a Ct value of 40 cycles was assigned for the calculation of human DNA ratio.

Amplification and Sequencing of hgRNA Barcodes

Barcodes were amplified by two rounds of PCR. The first round of PCR was performed with 100 ng genomic DNA using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) with Barcode-For and Barcode-Rev primers in 15 cycles. The second round of PCR were performed in a real-time setting and stopped in mid-exponential phase using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) with Barcode-P5-For and Barcode-P7-Rev primers. The sequences of primers are provided in Key Resources Table. PCR products were then column-purified with QIAquick PCR purification Kit (QIAGEN) and assessed with Qubit. The NEBNext Multiplex oligos for Illumina (Dual index primer set 1,NEB, E7600S) and the NEB library preparation kit for Illumina (NEB, #E7645S) were used for library preparation as previously described (Kalhor et al., 2017). Barcodes from MDA-MB-231 spontaneous metastases were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq lanes provided by Novogene while other samples were sequenced with NextSeq 500/550 lanes by the Genomic and RNA profiling Core at Baylor College of Medicine.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| mRFP in 1:500, Rabbit | Rockland | Cat# 600-401-379 RRID: AB_2209751 |

| GFP in 1:500, Chicken | Abcam | Cat# ab13970 RRID: AB_300798 |

| Anti-Mouse CD31 in 1:200, Goat | R&D Systems | Cat# AF3628 RRID: AB_2161028 |

| Anti-Mouse VE-Cadherin in 1:200, Goat | R&D Systems | Cat# AF1002 RRID: AB_2077789 |

| In Vivo Ready™ Anti-Mouse CD16 / CD32 (2.4G2), 1:100 | Tonbo Biosciences | Cat# 40-0161-M001 RRID: AB_2621443 |

| Anti-CD44 Rat Monoclonal Antibody APC, 1:100 | Tonbo Biosciences | Cat# 20-0441-U100 RRID: AB_2621572 |

| Anti-ALDH1A1 (B-5) Alexa Fluor 488, 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-374149-AF488 RRID: AB_10917910 |

| DsRed Antibody (E-8) Alexa Fluor® 594, 1:100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-390909-AF594 RRID: AB_2801575 |

| anti-Chicken IgY, Alexa Fluor 488 in 1:500, Donkey | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#703-546-155 RRID: AB_2340376 |

| anti-Mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 in 1:500, Donkey | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#715-545-151 RRID: AB_2341099 |

| anti-Rat IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 in 1:500, Donkey | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat#712-545-153 RRID: AB_2340684 |

| anti-Rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 in 1:500, Donkey | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A31572 RRID: AB_162543 |

| anti-Goat IgG, Alexa Fluor 647 in 1:500, Donkey | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 705-606-147 RRID: AB_2340438 |

| anti-Rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 647 in 1:500, Donkey | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat# 711-605-152 RRID: AB_2492288 |

| Anti-Mouse CD31, Alexa Fluor 488 | R&D Systems | Cat# AF3628G-100 |

| Anti-Cytokeratin 8, Rat, 1:100 | DSHB | Cat# TROMA-I RRID: AB_531826 |

| Anti-Cytokeratin 19, Rat, 1:100 | DSHB | Cat# TROMA-III RRID: AB_2133570 |

| PDGF Receptor β (28E1) Rabbit mAb, 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3169S RRID: AB_2162497 |

| Fgf Receptor 1 (D8E4) XP® Rabbit mAb, 1:1000 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9740S RRID: AB_11178519 |

| Ezh2 (D2C9) XP® Rabbit mAb, 1:1000 in western blotting, 1:100 in immunofluorescent staining | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5246S RRID: AB_10694683 |

| HCAM/CD44 rat antibody (IM7), 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-18849 RRID: AB_2074688 |

| γ-catenin Antibody (H-1), 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-8415 RRID: AB_628152 |

| Occludin Antibody (E-5), 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-133256 RRID: AB_2156317 |

| Anti-N Cadherin antibody, 1:200 | Abcam | Cat# ab12221 RRID: AB_298943 |

| Anti-human vimentin antibody, 1:2000 in western blotting, 1:200 in immunofluorescent staining | Leica | Cat# VIM-V9-L-CE RRID: AB_564055 |

| ZEB1 Antibody (H-3), 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-515797 |

| SLUG Antibody (A-7), 1:200 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-166476 RRID: AB_2191897 |

| GAPDH Antibody (FL-335), 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-25778 RRID: AB_10167668 |

| Goat Anti-Rat IgG Polyclonal Antibody (IRDye® 800CW) | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32219 RRID: AB_1850025 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Polyclonal Antibody (IRDye® 800CW) | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32211 RRID: AB_621843 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG Polyclonal Antibody (IRDye® 800CW) | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926-32210 RRID: AB_621842 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Dextran, Fluorescein, 70000 MW | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# D1822 |

| EPZ011989 | Epizyme | N/A |

| RapiClear® 1.49 | SunJin Lab | Cat# RC149001 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| NEBNext® Multiplex Oligos for Illumina | New England BioLabs | Cat# E7600S |

| NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | New England BioLabs | Cat# E7645S |

| Nextseq 500/550 high output v2 kit | Illumina | Cat# 20024908 |

| NEBNext® High-Fidelity 2X PCR Master Mix | New England BioLabs | Cat# M0541S |

| PlatinumTaq DNA Polymerase | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10966026 |

| Tumor Dissociation Kit, Mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-396-730 |

| Aldefluor™ Kit | Stemcell Tech | Cat# 01700 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw data of Barcode Sequencing | GEO | GSE161145 |

| Raw data of RNA Sequencing of SCP21 cells | GEO | GSE160773 |

| Raw data of WES Sequencing of SCP21 cells | GEO | GSE161181 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human breast cancer MCF7 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-22 RRID:CVCL_0031 |

| Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-26 RRID:CVCL_0062 |

| Human prostate cancer PC-3 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1435 RRID:CVCL_0035 |

| Murine breast cancer AT-3 | EMD Millipore | Cat# SCC178 RRID:CVCL_VR89 |

| MCF7 Single cell derived population SCP2 | This Paper | N/A |

| MDA-MB-231 Single cell derived population SCP21 | This Paper | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu | Envigo | N/A |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratories | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Mouse: NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1Mom Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | Jackson Laboratories | RRID:IMSR_JAX:007799 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for CD44, GAPDH, ZEB1, CDH1, FN1, CDH2, VIM, EZH2, SNAI2, GJA1, and JUP mRNA, see Table S2 | This Paper | N/A |

| Primers for human HPRT1 and mouse Gapdh DNA, see Table S2 | This Paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides for cloning of TLCV2-A26, see Table S2 | This Paper | N/A |

| Primers for library preparation of barcodes, see Table S2 | This Paper | N/A |

| shRNA targeting sequence: EZH2 #1: TTACTGTCCCAATGGTCAG | Horizon Discovery | Cat# RHS4696-200690448 |

| shRNA targeting sequence: EZH2 #2: TTTGGCTTCATCTTTATTG | Horizon Discovery | Cat# RHS4696-200688725 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pwpt-Fluc/GFP or pwpt-Fluc/RFP | Wang et al., 2015 | NA |

| TLCV2 | Barger et al., 2019 | Addgene #87360 |

| TRIPZ-shEZH2-1 | Horizon Discovery | Cat# RHS4696-200690448 |

| TRIPZ-shEZH2-2 | Horizon Discovery | Cat# RHS4696-200688725 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | National Institute of Health | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Living Image | PerkinElmer | https://www.perkinelmer.com.cn/product/spectrum-200-living-image-v4series-1-128113 |

| Inveon Research Workplace | SIEMENS | https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/en-us/molecular-imaging/preclinical-imaging/inveon-workplace/ |

| Inkscape | The Inkscape Project | https://inkscape.org/ |

| R 3.3.4 | R Core Team | https://rstudio.com/ |

| Graphpad Prism 8 | GraphPad Software, Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| FlowJo, v10.0 | BD | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Imaris Viewer | Oxford Instrument | https://imaris.oxinst.com/imaris-viewer |

| TraceQC | Hu et al., 2020 | https://github.com/LiuzLab/TraceQC |

| Cutadapt | Martin, 2011 | https://github.com/marcelm/cutadapt/ |

| Trim Galore | Felix Krueger | https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore |

| SAMtools | Li et al., 2009 | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| Picard | Broad Institute | http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ |

| VarScan2 | Koboldt et al., 2012 | http://dkoboldt.github.io/varscan/ |

| Expands | Andor et al., 2014 | http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/expands |

| Other | ||

| Barcode Analysis Code | This paper | https://github.com/LiuzLab/CRISPR_bone_metastasis-manuscript |

Evolving Barcode Data Processing

A customized pipeline was used to extract the sequences and counts of barcodes from FASTQ files. Briefly, to identify the barcoding region, the R1 sequence was globally aligned to the A26 reference barcode. The parameters used for alignment are: +2 for match score, −2 for mismatch score, −6 for gap opening penalty and −0.1 for gap extension penalty. Next, the adapter sequences were trimmed off from the annotated sequence. Then, the sequences with alignment scores lower than 200 or with count less than 10 were removed from the subsequent analysis. Barcode sequence from each read was extract, which is 117 bps starting from 58 bp before the predicted TSS of TLCV2 plasmid. Then the mutation events were categorized by TraceQC package (https://github.com/LiuzLab/TraceQC) into 4 attributes of barcodes: type of mutations, starting position, length of mutation, and the mutant sequence. The mutation events were normalized by the read count per million (RPM) approach and the normalized count was used to generate the feature matrixes for metastases in each animal. The Shannon entropy of mutation events were calculated using the formula: .

Non-negative matrix factorization analysis

To delineate the phylogenetic relation across metastases of different sites, we performed the Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) analysis on the normalized mutation count matrix using NMF package in R (Gaujoux and Seoighe, 2010). The NMF analysis generate robust clusters on both mutation events and metastatic samples, which can be further interpreted into features shared across clonotypes. Given the dimension of the mutation count matrix, we ran the NMF analysis 200 times to perform the rank survey. To determine the appropriate rank (k) for NMF analysis, in addition to visually examination of the clusters, Cophenetic and Silhouette scores were used to quantitatively evaluate the robustness of NMF clusters. The Cophenetic score measures the similarity of two objects to be clustered into one cluster in the consensus matrix. High Cophenetic correlation means the consensus matrix possesses better separated clusters. In mouse 510, k=6, while in mouse 509, k=7 or 8; in mouse 121 and 520, k<5, is the local optimum as shown in the Cophenetic score curve. The Silhouette score was then used to validate the choice of k, as it indicates the similarity of an object to its belonged cluster. The Silhouette scores also evaluate the consistency between the consensus map and the coefficient matrix. Based on the Silhouette curves, k= 6 in mouse 510 while k=7 for mouse 509, k=3 for both mouse 121 and 520 is the local optimum for the consensus matrix in NMF analysis of individual mutation matrix. To enable the reproducibility of the NMF analysis, the final factorization was run with an initial seed on the chosen rank. The body maps were then generated from the values of each basis in a specific metastasis in the mixture coefficient matrix in combination with the value of Shannon entropy. To illustrate the composition flow of barcodes across samples, the count matrix of mutation events was firstly ranked and segmented to enable the most connectivity between two samples by Excel. The difference of Shannon entropy was used to decide the direction of flow. Chord diagrams were generated by Inkscape to proportionally reflect the flow of mutation events. Bar length indicates the entropy. Solid proportion, mutation events pre-existed in the primary tumor; striped proportion, mutation events induced by doxycycline. The numbers of mutation events are denoted. Connections with the break are mutation events that are absent in the parental lesions but present in primary tumors.

Assessment of Metastasis of Organ-entrained SCPs

SCP21 or MCF7-SCP2 cells tagged with mRFP and luciferase gene were implanted to the mammary fat pads, hind limbs, or lungs of female nude mice through MFP, IIA or IIV injection, respectively. 6 weeks later, 4 mammary, 3 lung and 4 bone entrained cells were recovered from SCP21 xenografts. For MCF7-SCP2 cells, two mammary tumors and one bone metastases were recovered. All the animals failed to develop lung metastases after receiving one million MCF7-SCP2 cells through tail vein injection, therefore lung-entrained MCF7-SCP2 cells were not examined in this study. mRFP+ tumor cells were then sorted out from the single cell mixture prepared by the tumor dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). For bone metastases, bone marrow was discarded, and the bone fragments were subjected to the collagenase digestion prior the tumor dissociation. The organ-entrained cells were then expanded under regular culture condition, and cryopreserved immediately after reaching confluency, and considered as P1 SCPs. If not specified, cells were sub-cultured every 5 days and most experiments were performed with SCPs at passage 3. The in vitro treatment of EPZ011989 (1uM) was started with BoM-SCPs at passage 2 and lasted for 5 days. 1E5 different organ entrained cells (randomly selected) at passage 3 and parental SCP21 cells were injected into the left ventricle (intra-cardiac injection) of nude mice. The animals were monitored by BLI imaging weekly.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were trypsinated at about 80% confluence and the cell number was counted. 20E4 cells were resuspended in 1 ml ALDEFUOR™ Assay buffer, and 5 ul of activated substrate was added into the cell suspension. Then, 0.5 ml of the mixture was transferred to another tube with 5 ul DEAB to inactivate the ALDH enzymatic reaction. Both the DEAB and test samples were incubated at 37°C for 45 min. For CD44 staining, cells were blocked with mouse anti-CD16/32 antibody (Tonbo Biosciences) for 10 minutes and then stained with APC conjugated CD44 antibody (Tonbo Biosciences) on ice for 30 minutes. ALDH+ cells and CD44 expression were then examined with BD LSR Fortessa Analyzer, and analyzed with FlowJo v10.0 (BD). The percentage of ALDH1+ population in test samples was determined with the same gate containing 0.1% positive cells in the corresponding DEAB sample.

RNA and Protein Extraction and Quantification

Total RNA was extracted from TRIzol™ (Invitrogen) lysed cells by Direct-zol RNA miniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) with an extra step of in-column DNase treatment. For qRT-PCR, cDNA was generated with RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, K1622) with 1 ug of total RNA following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher) on Biorad CFX Real-Time system. The expression levels of GAPDH mRNA were used as the internal control. The primer sequences are listed in the Supplementary Table 2. For western blotting, cells were directly scratched from the culture dishes and lysed with RIPA buffer. 20 μg of total proteins were used for electrophoresis with NuPAGE® Novex® Gel system (Invitrogen). Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using iBlot™ Transfer System (Invitrogen). The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The next day, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (LI-COR Bioscience) and scanned by the Odyssey® infrared imaging system. The antibodies and conditions used in this study were listed in Key Resources Table.

RNA-Sequencing and Whole Exome Sequencing

mRNA sequencing, read mapping, normalization and quantification were performed by Novogene. One of four MFP-SCP21 samples failed the quality check and was excluded from the subsequent analysis. EZH2 signature were calculated as the average expression of EZH2-suppressed genes (MSigDB geneset: LU_EZH2_TARGETS_DN) (Lu et al., 2010). Whole exome sequencing was performed by the Genomic and RNA profiling Core at Baylor College of Medicine with 100X coverage. Sequences were trimmed by Cutadapt (Martin, 2011) and Trim Galore and aligned to hg19 reference genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm after the quality check by FastQC and MultiQC. SAMtools (Li et al., 2009) and Picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) were then used to filter the BAM files and remove duplicated reads. The control sample was from 1000-Genomes (ERR031938) and processed accordingly. Copy number and somatic variations were then analyzed with VarScan 2 (Koboldt et al., 2012). The variants with p-value less than 0.01 were subjected to the following analyses and processed on Galaxy platform (Afgan et al., 2018). The EXPANDS package (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/expands) was used to delineate the clonal structure of SCP21 sublines as previously described (Andor et al., 2014).

Capture and Staining of CTCs

500μl blood were draw from the right ventricle of anesthetized NRG mice inoculated with mammary tumors or bone metastases after 6 weeks. Blood samples were immediately mixed with 8 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 250 g for 10 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was discarded. The same steps were repeated once to completely remove red blood cells. Cell pellets were then re-suspended with cold PBS and transferred to poly-L-lysine coated slides. The slides were placed in the 37°C incubator for 30 minutes, and fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes. Fixed cells were rinsed with PBS for three times, and permeated with 0.3% Triton-X 100 for 30 minutes at RT. Slides were then blocked with donkey serum (Sigma) and anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (Tonbo Biosciences) for 2 hours and incubated with fluorescence conjugated primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The next day, slides were stained with DAPI and mounted with Prolong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant (Molecular Probe). Circulating tumor cells were identified and imaged by a CyteFinder® instrument (Rarecyte) with same exposure setting.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Number of animals or independent replicates, and the type of statistical test used are denoted in the figure legends or figures. In most animal experiments, the investigators were not blind to the allocation of animals due to the nature of the experimental design and the need of continual monitoring on subjects. All the in vitro study has been repeated at least twice with more than three independent replicates, and the investigators were blind until the assessment of outcome. Sample sizes were chosen empirically or based on the preliminary experiments, and no statistical approach was used to pre-determine the group size. If not specified otherwise, all the data and statistical analysis were generated by GraphPad Prism 8. Graphs generally show all replicate values. In bar and curve plots, data are represented as Mean±SEM. Some data points were accidentally not saved during the BLI imaging and therefore missing in Fig 1J, Fig 2C, and Fig 2G. Only part of the animals in Fig 5A were examined after dissection due to the institutional lockdown during the pandemic. All the other available data points were included and two-sided tests were performed in the analysis. F test was performed prior to the Student’s t test to assess the variance difference. Welch’s correction was applied to the Student’s t-test if the null hypothesis of F test was rejected. P < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Metastatic spread in animals with established bone metastases, Related to Figure 1

(A) Metastatic lesions detected by microCT and the corresponding ex vivo bioluminescent imaging (lower) on the same bones. Right table showing that 12 in 35 lesions recovered by BLI were not detected by microCT in this study.

(B)Deep imaging of metastases in various tissues from mice with primary bone metastases at the right hindlimb. Clarified tissues were imaged in tiles. The obtained image tiles were then stitched by Fluoview to reconstruct views of vasculatures and tumor lesions by Imaris View. The dotted box indicates a part of image that was not appropriately scanned and stitched due to lack of focus. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(C) H&E staining of tumor lesions across various tissues from mice with IIA-injected bone metastases. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(D-E) Correlation plots showing the relationship between ex vivo BLI intensities and the lesion size across paired hindlimbs (D) or various tissues (E). The lesion size refers to the ratio of human genomic content on tissues of the same weight here. Such ratio was calculated with the Ct values of human HPRT and mouse Gapdh DNA by q-PCR. Spearman correlation r and p value were indicated.

(F) Heat map showing the metastatic pattern in animals with established PC3 or MCF7 bone lesions via IIA injection. Red cells indicate the presence while gray cells represent the absence of detectable lesions by ex vivo BLI imaging. N (# of mice) = 8 (PC3); 8 (MCF7).

(G)Representative immunofluorescent images of tumor lesions in skeletal and other tissues from animals with intra-femoral injected MDA-MB-231 cells. To obtain complete views of entire organs, smaller fields were acquired in tiles by mosaic scanning and then stitched by Zen. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Supplementary Figure 2. Established bone tumors metastasize more to other tissues, Related to Figure 2

(A) PET scanning of mammary gland, lung, and hindlimbs of animals with established mammary tumors (MFP), lung metastases (LuM) or bone metastases (BoM).

(B) microCT scanning of the hindlimbs from mice with established mammary tumors, lung metastases, or bone metastases and tumor-free control mice.