Abstract

The pharmacotherapy of Takayasu arteritis (TAK) with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) is an evolving area. A systematic review of Scopus, Web of Science, Pubmed Central, clinical trial databases and recent international rheumatology conferences for interventional and observational studies reporting the effectiveness of DMARDs in TAK identified four randomized controlled trials (RCTs, with another longer-term follow-up of one RCT) and 63 observational studies. The identified trials had some concern or high risk of bias. Most observational studies were downgraded on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale due to lack of appropriate comparator groups. Studies used heterogenous outcomes of clinical responses, angiographic stabilization, normalization of inflammatory markers, reduction in vascular uptake on positron emission tomography, reduction in prednisolone doses and relapses. Tocilizumab showed benefit in a RCT compared to placebo in a secondary per-protocol analysis but not the primary intention-to-treat analysis. Abatacept failed to demonstrate benefit compared to placebo for preventing relapses in another RCT. Pooled data from uncontrolled observational studies demonstrated beneficial clinical responses and angiographic stabilization in nearly 80% patients treated with tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, tocilizumab or leflunomide. Certainty of evidence for outcomes from RCTs ranged from moderate to very low and was low to very low for all observational studies. There is a paucity of high-quality evidence to guide the pharmacotherapy of TAK. Future observational studies should attempt to include appropriate comparator arms. Multicentric, adequately powered RCTs assessing both clinical and angiographic responses are necessary in TAK.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10067-021-05743-2.

Keywords: Anti-rheumatic drugs, Aortoarteritis, Biological drugs, Disease-modifying systematic review, Meta-analysis, Takayasu arteritis

Introduction

Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is a granulomatous large vessel vasculitis which predominantly affects young females and is more common in Asian countries. Patients with TAK have myriad manifestations. These might be either related to systemic symptoms as a part of the inflammatory response, or vascular symptoms resulting in pulse loss, pulse inequality, vascular bruits and ischemia distal to the site of vascular occlusion. Aberrant activation of the immune system underlies the pathogenesis of TAK, with involvement of both innate (macrophages) and adaptive (T lymphocytes) immunity in driving the disease processes in TAK. Prednisolone remains the first-line therapy in newly diagnosed, active TAK. Considering the long-term adverse effects of prednisolone [1], patients with TAK who require immunosuppressive therapy are generally initiated on a steroid-sparing disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) simultaneously to minimize dose and duration of corticosteroid exposure [2].

Assessment of disease activity in TAK is challenging since the onset of vascular inflammation can be insidious. Clinical outcomes of partial or complete remission have been variously defined, either dependent on physician global assessment, or based on normalization of inflammatory markers or reduction in composite disease activity indices such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria (“Kerr” criteria) for assessing disease activity in TAK or the Indian Takayasu Clinical Activity Score (ITAS 2010). Serial angiographic assessment demonstrating stabilization of vascular territory involvement, with either lack of progression or regression of vascular segments involved on angiography, is another measure of reduction of disease activity. Reduction in vascular wall metabolic activity using 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18 FDG) positron emission tomography computerized tomography (PET-CT) is also indicative of reduction in active disease. Reduction in prednisolone dose following therapy, reduction/delay in number of relapses and prolongation of time of remission are other measures of control of disease activity that have been used in the literature[3].

Systematic reviews are considered the highest level of evidence in the hierarchy of evidence-based medicine. Information from systematic reviews underlies the development of recommendations or guidelines for disease management[4, 5]. While the role of DMARD therapy in ameliorating disease activity in TAK has been the subject of previous systematic reviews[6–9], there remains a need to update this information in the context of emerging new literature regarding the pharmacotherapy of TAK. Lack of extensive database searches is another limitation of existing systematic reviews on this topic[10]. In this context, we undertook a systematic review to critically evaluate the literature supporting the use of DMARDs in the management of TAK with respect to outcomes assessed by clinical assessment, angiography and other imaging modalities, inflammatory markers and relapses.

Methods

Protocol

The systematic review protocol was pre-published[11]. We could not register the protocol on the prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) in view of the coronavirus disease 19 pandemic delaying registration of new systematic reviews on the platform. The systematic review was conducted as per the methodology prescribed by the Cochrane collaboration [12] and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Standards for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Table 1) [13] and its recent amendment to describe in detail literature searches across multiple databases (PRISMA-S) (Supplementary Table 2) [14].

Literature searches

Scopus (which includes all the data on Medline), Web of Science and Pubmed Central (via Pubmed) were searched on 2 February 2021 for studies describing DMARDs in TAK, without any restrictions of date or language. Detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 3.

In addition, the past 3-year abstracts (2018–2020) of major international Rheumatology conferences (American College of Rheumatology (ACR), European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), Asia-Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR)) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), clinicaltrials.gov and Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) were searched for clinical trials on TAK to identify any relevant studies that might have yet been unpublished but whose results were available on these platforms. Any conference abstracts that were obtained from database searches were manually searched to identify any full papers that might have been published but were missed on database searches.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Patients diagnosed to have TAK by the clinician, or fulfilling American College of Rheumatology 1990 classification criteria [15], Ishikawa criteria [16] or Ishikawa criteria modified by Sharma [17], were included. Studies including children were classified using EULAR/Pediatric Rheumatology International Society/Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization classification criteria for pediatric-onset TAK [18], American College of Rheumatology 1990 classification criteria [15] or by a clinician diagnosis. Considering that TAK is a rare disease, studies including at least five participants were included. Studies were included irrespective of the age of participants.

Interventions

Drugs which previously had been described to have a role in therapeutics of or where targeted pathways have been identified to play a role in pathogenesis of TAK or its counterpart large vessel vasculitis, giant cell arteritis (GCA), were included (methotrexate, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate, leflunomide, cyclophosphamide, dapsone, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, abatacept, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab, tocilizumab, ustekinumab, briakinumab, secukinumab, rituximab, tofacitinib, Janus kinase inhibitors, resveratrol, curcumin)[2, 8, 9].

Comparators

Studies including comparators (placebo or any of the interventions described above as active comparator) as well as those without comparators were included.

Outcome measures

Due to the heterogenous outcome measures used in TAK, studies describing any of the following outcomes were included:

Remission based on clinical outcomes—either partial or complete remission as defined by the study investigators, or composite measures, i.e. NIH criteria[19] or ITAS2010[20].

Remission based on normalization of inflammatory markers.

Stabilization or retardation of progression on serial angiography (also referred to as angiographic stabilization).

Improvement in PET-CT.

Improvement in quality of life parameters.

Disease relapses following DMARD initiation.

A secondary outcome measure used was safety of DMARDs used, by evaluating the proportion of patients who developed adverse events. Post hoc secondary analyses assessed outcomes based on DMARD type (biologic versus conventional), infections in patients with DMARDs and reduction in prednisolone dose before and after DMARD therapy.

While the review protocol had proposed separate analyses of remission based on clinical outcomes and composite outcomes, the paucity of data on composite outcomes in the available studies led us to modify the protocol to analyse these two outcomes together.

Type of studies

Due to the paucity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in TAK[2], both observational and interventional studies were included. Observational studies which described any of the above outcomes in a defined group of patients for a defined set of DMARDs at a definite time point were included, provided such outcomes were reported in at least 5 patients. If the same cohort study described outcomes for different DMARDs in different number of TAK patients, only those outcomes reported for at least five patients were included in the synthesis of data. Studies describing outcomes for DMARDs both with and without corticosteroids were included.

Exclusion criteria

Original articles other than interventional studies or observational studies providing treatment outcomes with DMARDs.

Review articles, letter to editor not describing original data, case report or editorial.

Studies not directly reporting outcomes in TAK but rather reporting outcomes in other forms of large vessel vasculitis.

Studies presenting outcomes of corticosteroid therapy alone or endovascular/surgical interventions alone, without concomitant DMARD therapy.

Studies whose full text was not accessible and whose abstract did not provide adequate information relevant to the objectives of the systematic review.

Studies in abstract form whose full text was published elsewhere.

Screening and data extraction

All search results from Scopus, Web of Science and Pubmed Central were downloaded on to Endnote X9.3 and duplicates removed. The abstract and titles were screened independently by two investigators (DPM, PP) to identify articles of potential relevance to the objectives of the systematic review for further review, noting reasons for exclusion. Such screened articles were further screened in detail (full text where accessible, or abstracts if they provided adequate information) to identify relevant articles while noting reasons for any exclusions. Duplicate items selected from multiple databases were excluded. Further, articles that were eligible for quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) were delineated. Differences between investigators were resolved by discussion. A flowchart to delineate the search results was prepared according to the PRISMA and PRISMA-S guidelines [13, 14].

Information from the selected articles were extracted independently by two investigators (DPM, UR) on to pre-designed proformas for uncontrolled observational studies, controlled observational studies and RCTs, which are available in the study protocol[11]. Discrepancies were resolved by mutual discussion.

Quality assessment of individual studies

The Cochrane risk of bias 2 (RoB 2) tool was used to assess the risk of bias in the identified RCTs, evaluating five different areas (randomization, effect of assignment of intervention/effect of adhering to intervention, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome of interest, selective reporting of outcomes) for risk of bias. For each domain and overall, risk of bias was rated as low, some concern or high as per the instructions provided in the tool[21].

Observational studies were subject to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for cohort studies to evaluate study quality based on selection of subjects (up to four stars), comparability of subjects (up to 2 stars) and outcome assessment (up to three stars). A study could obtain a maximum of 9 stars (minimum of zero)[22]. Based on previous systematic reviews utilizing this tool, a score of 7–9 was indicative of high quality, 4–6 moderate quality and 3 or less low quality [23].

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots if there were at least ten studies for a pair of comparisons between active interventions, or between active interventions and placebo[24, 25]. Funnel plots were generated using Stata 16.1 I/C, and the egger test for evidence against the null hypothesis of no small-study effects was assessed.

Certainty of evidence

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) profiler was used to evaluate certainty of evidence for a particular outcome across multiple studies, taking into account study design, risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency or results across studies, imprecision of estimates and other quality measures including publication bias. Based on these parameters, certainty of outcomes was rated as very low, low, moderate or high degree of certainty [26].

Analysis plan

Detailed summary of findings tables were generated separately for uncontrolled observational studies and for controlled studies (both observational and interventional) to present characteristics of the patients studied. If studies did not present means with standard deviations, these were calculated from the individual data of patients if available; otherwise, the measures provided in the study (mean, mean with range, median, median with interquartile range, median with range or range alone) were presented. Means and standard deviations across groups were pooled using online calculators for the same, wherever required [27].

Meta-analyses were performed using STATA 16.1 I/C. For uncontrolled observational studies, proportions of patients (along with 95% confidence intervals—95% CI) attaining at least a partial clinical response (including both those that attained a partial or complete clinical response, as stated by the study investigators), improvement in inflammatory markers, angiographic stabilization, improvement in PET-CT, proportions of relapses, percentage reduction in prednisolone dose before and after treatment (whether presented as means or medians) and proportions of patients with adverse events were pooled across studies using the metaprop command. Confidence intervals derived using the score test and Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation, which allowed pooling of proportions with value either 0 or 1, were used[28]. For controlled observational studies, risk ratio of outcomes for one intervention compared to the other/intervention compared to placebo was calculated along with their 95% CI using online calculators[29]. These risk ratios were pooled where possible across studies using the metan command. Random effects meta-analysis was used a priori in view of heterogenous patient groups and varying follow-up periods. Heterogeneity of pooled estimates was assessed using the I2 test, with values exceeding 50% suggestive of considerable heterogeneity. For pooled results with considerable heterogeneity (I2 ≥50%), studies were excluded one at a time to evaluate whether this reduced the I2 below 50% (thereby explaining the heterogeneity). For studies not amenable to meta-analyses, a descriptive reporting of outcomes was provided. Subgroup analyses were planned based on patient populations of adults or children, due to systematic differences between patients with childhood and adult-onset TAK described previously in the literature [30, 31].

Results

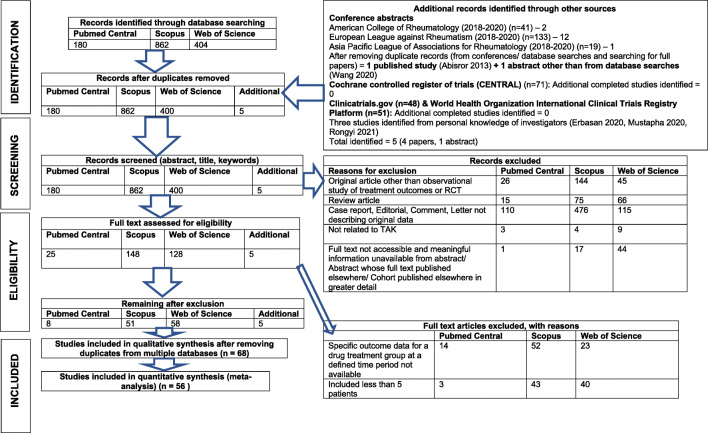

Detailed search results are presented in Supplementary Table 3. The search results are described in Fig. 1. Overall, 68 studies (2089 patients with TAK) were included in the systematic review [32–99]. There were four RCTs (and a further long-term open label follow-up of one of the clinical trials, all prospective in nature), all the other studies were observational. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of uncontrolled observational studies. One study was population based[61], rest were all hospital based. Only two of the studies on biologic drugs included DMARD-naïve TAK alone [52, 87], the rest predominantly included DMARD experienced patients with few DMARD-naïve patients. None of the studies exclusively reported composite outcomes using NIH criteria or ITAS-2010 as criteria for remission, instead considered them along with other clinical response parameters. Table 2 summarizes characteristics of controlled observational studies and clinical trials. Two of the RCTs were single-centre studies, the others were multicentric. For the observational studies, 39 were single-centre studies and 24 multicentric, whereas 28 were prospective and 35 retrospective. Furthermore, 50 studies (832 patients with TAK) from uncontrolled observational studies and 6 studies (285 patients with TAK) from controlled observational studies were synthesized in meta-analyses. The mean (±standard deviation) number of patients with TAK enrolled in each uncontrolled observational study was 16.6 (±14.1), in each controlled observational study was 56.1 (±34) and in each clinical trial was 132 (±117.2). The mean number of patients in each clinical trial was skewed considerably by two studies [65, 66] which included 466 patients.

Fig. 1.

Search results (adapted from the PRISMA flow diagram [13])

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies—uncontrolled observational studies

| Study (reference no) | Intervention | Outcomes being evaluated | Disease duration | Total subjects enrolled | Gender (M:F) | Age of subjects | Follow-up duration | Children/adults/both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shelhamer 1985 (32) | CYC | Clinical; Angio | 3 me | 7 | 0:7 | 23.57 ± 10.56 ya | NA | Both |

| Hoffman 1994 (33) | MTX | Clinical; Angio; relapse | 5.2 (1–12) yb | 18 | 3:15 | 30 (13–56) yb | 2.8 (1.3–4.8) yb | Both |

| Hahn 1998 (34) | CYC | Relapse | NA | 13 | NA | NA | NA | Children |

| Valsakumar 2003 (35) | AZA | Clinical; Angio; relapse | 12.9 ± 5.8 ma | 15 | 0:15 | 28.3 ± 7.3 ya | 1 y e | Both |

| de Franciscis 2007 (38) | MTX + CYC | Clinical; relapse; inflammatory | NA | 10 | 2:8 | 37.1 ± 4.1 ya | 5.5 (2–10) yc | Adults |

| Shinjo 2007 (39) | MMF | Clinical; ∆CS | 57.5 ± 65.8 ma | 10 | 3:7 | 29.9 ± 8.9 ya | 23.3 ± 12.1 ma | Adults |

| Goel 2010 (41) | MMF | Clinical; ∆CS | 35.5 ± 28.4 ma | 21 | 2:19 | 31.9 ± 13.8 ya | 9.6 ± 6.4 ma | Both |

| de Souza 2012 (42) | LEF | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 38 (29.1–73) md | 15 | 1:14 | 36.2 ± 12.6 ya | 9.1 ± 3 ma | Adults |

| Stern 2014 (53) | CYC | Clinical | 2.6 ± 2.4 ya | 16 | NA | NA | 12 (7–36) md | Children |

| Li 2016 (58) | MMF | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 12 (7.5–36) md | 30 | 3:27 | 24.5 (19.8,32) yd | 17 (11,28) md | NA |

| Ohigashi 2017 (64) | MTX, CsA, AZA, TAC | Clinical | 70.8 ± 40.8 ma | 44 | 3:41 | NA | NA | Both |

| Cui 2020 (82) | LEF | Clinical; Angio; relapse | NA | 56 | 14:42 | 31.85 ± 12.56 ya | 14.44 ± 6.86 ma | Both |

| Wei 2021 (97) | CYC | Clinical | 5.12 ± 7.26 ya | 71 | 7:64 | 29.44 ± 11.75 ya | 3.42 ± 2.38 ya | Both |

| Mustapha 2020 (99) | LEF | Clinical | NA | 9 | NA | NA | 24 me | NA |

| Li 2020 (86) | Tofacitinib | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 32.4 ± 25.5 ma | 5 | 0:5 | 22 ± 4.58 ya | 6 me | Both |

| Nakagomi 2018 (71) | Rituximab | Clinical; ∆CS; relapse | 5.5 yf | 8 | NA | 38 yf | 12 me | NA |

| Pazzola 2018 (75) | Rituximab | Clinical; Angio; PET; ∆CS | 4.8 ± 7.7 ya | 7 | 1:6 | 32.4 ± 17.3 ya | 32.57 ± 24.7 ma | Both |

| Hoffman 2004 (36) | TNFi (ETAN, IFX) | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse | 6.5 ye | 15 | 1:14 | 27.53 ± 9.32 ya | 20.67 ± 15.86 ma | Both |

| Baldissera 2007 (37) | TNFi (IFX, ADA,ETAN) | Angio; ∆CS | 52 (17–226) mc | 12 | 1:11 | 35 ± 10 ya | 15 (4–28) mc | NA |

| Molloy 2010 (40) | TNFi (IFX, ETAN) | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse | 116 (39–344) mc | 25 | 3:22 | 35 (15–64) yb |

IFX 28 (2–84) mc; ETAN 28 (4–82) mc |

Both |

| Mekinian 2012 (43) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; ∆CS | 37 (6–365) mc | 15 | 2:13 | 41 (17–61) yc | 43 (4–71) mc | Both |

| Quartuccio 2012 (44) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; Angio; inflammatory; ∆CS; relapse | 12 (0–96) mc | 15 | NA | 33.07 ± 14.54 ya | 74 ± 44 ma | Both |

| Schmidt 2012 (45) | TNFi IIFX, ADA,ETAN) | Clinical; Angio; relapse | 15.9 (2–32.7) md | 20 | 1:19 | 33 ± 10.2 ya | 23 (8.7–38.9) md | NA |

| Tombetti 2013 (48) | TNFi (IFX, ADA, GOL) | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | NA | 15 | 0:15 | 36 ye | 46 (11–56) mb | NA |

| Serra 2014 (52) | TNFi (ADA, IFX) | Clinical; inflammatory | Enrolled at diagnosis | 5 | 1:4 | 36.6 ± 2.41 ya | 1 ye | Adults |

| Youngstein 2014 (54) | TNFi (IFX, ADA,ETAN) | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse | NA | 8 | 1:7 | 25.88 ± 5.28 ya | 42 (5–96) mb | Both |

| Kleinmann 2017 (62) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; ∆CS; relapse | 4.7 (0.4–16) yc | 14 | 1:13 | 32 (12–56) yc | 2 ye | Both |

| Novikov 2018 (73) | TNFi (CER) | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse | 139.4 ± 73.9 ma | 10 | 0:10 | 29.6 ± 6.13 ya | 13.8 ± 9.67 ma | Adults |

| Park 2018 (74) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; PET | 4.4 ± 5.2 ya | 11 | 0:11 | 46.8 ± 13.5 ya | 30 we | Adults |

| Banerjee 2020 (79) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; PET; ∆CS | NA | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Campochiaro 2020 (81) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; Angio; PET | 95.5 ± 61.3 ma | 23 | 2:21 | 43.8 ± 14.4 ya | 12 me | NA |

| Mertz 2020 (88) | TNFi (IFX) | Clinical; ∆CS | 3 (1–5) yd | 23 | 4:19 | 33 (23–44) yd | 36.9 (10–58.7) md | NA |

| Erbasan 2020 (98) | TNFi (IFX), Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio | NA | 15 | NA | NA | 58.3 ± 9.5 ma (IFX), 19.5 ± 5 ma (Tocilizumab) | Both |

| Abisror 2013 (46) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; PET; relapse | NA | 5 | 1:4 | 54 ± 8.69 ya | 13.8 ± 6.91 ma | Adults |

| Goel 2013 (47) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; inflammatory; ∆CS | 25.5 (1.5–60) mc | 10 | 1:9 | 24.5 (13–53) yc | 5 me | Both |

| Tombetti 2013 (49) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; inflammatory | 66 (17–82) md | 7 | 0:7 | 24 (23–30) yd | 14 (10–33) md | Adults |

| Canas 2014 (50) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; inflammatory; ∆CS; relapse | 8.1 ± 10 ya | 8 | 0:8 | 27.8 ± 12.1 ya | 18.5 ± 8.5 ma | Both |

| Loricera 2014 (51) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; PET; ∆CS | NA | 7 | 0:7 | 34 ± 18.1 ya | 12.3 ± 7.4 ma | Both |

| Novikov 2015 (56) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse | 48.5 (29–146) mc | 10 | 0:10 | 23.5 (19–56) yc | 6 (3–15) mc | Adults |

| Loricera 2016 (59) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; PET; ∆CS | 11 (6–50) md | 8 | 0:8 | 34 ± 16 ya | 15.5 (12–24) md | Both |

| Zhou 2017 (68) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; inflammatory; Angio; ∆CS | 34.7 ± 31.6 ma | 13 | 12:1 | 13.2 ± 3.8 ma | 13 (7–20) mc | Adults |

| Mekinian 2018 (70) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | NA | 46 | 11:35 | 43 (29–54) yc | 0.9 (0.5–2) yc | Adults |

| Kato M 2019 (76) | Tocilizumab | Inflammatory; PET | 176 ± 136 ma | 5 | 1:4 | 42.2 ± 11.6 ya | 6–12 m | NA |

| Shah 2019 (77) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 2 (1.1–3.2) yd | 14 | 0:14 | 30.5 (25–40) yd | 6 me | NA |

| Gon 2020 (84) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; ∆CS | NA | 5 | 0:5 | 31.2 ± 3.9 ya | 24–53 mg | NA |

| Kilic 2020 (85) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 24 (12–168) mc | 15 | 2:13 | 35 (20–58) yc | 15 (3–42) mc | Adults |

| Mekinian 2020 (87) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; ∆CS; relapse | 8 (0.7–185) mc | 13 | 1:12 | 32 (19–45) yc | 6 me | Adults |

| Prieto–Pena 2020 (91) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; ∆CS | 12 (3–48) mc | 53 | 7:46 | 40.6 ± 14.6 ya | up to 12 m | Adults |

| Wang 2020 (92) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; Angio | NA | 6 | 3:3 | 7 (2–13) yc | 6 me | Children |

| Isobe 2021 (95) | Tocilizumab | Clinical; PET; ∆CS | 14.3 ± 13.9 ya | 19 | 2:17 | 41.4 ± 13.1 ya | 27.6 ± 14.4 ya | NA |

m months, w week, y years, Angio serial angiographic assessment, ∆CS change in corticosteroid dose before and after, ADA adalimumab, AZA azathioprine, CER certolizumab, CsA cyclosporine, CYC cyclophosphamide, ETAN etanercept, GOL golimumab, IFX infliximab, Inflammatory inflammatory markers, LEF leflunomide, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MTX methotrexate, PET positron emission tomography computerized tomography, TAC tacrolimus, TNFi tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

aMean ± standard deviation

bMean with range

cMedian with range

dMedian with interquartile range

eMean

fMedian

gRange

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies—observational studies with control group and interventional studies

| Study (reference no) | Intervention (I) |

Comparator (C) |

Outcomes being evaluated | Disease duration | Total subjects enrolled | Gender (M:F) | Age of subjects | Follow-up duration | Children/adults/both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Souza 2016 (57) | LEF | Other DMARDs | Angio; ∆CS | 95 (73–144) mc I, 77 (62–112) mc C | 12 (5 I, 7 C) | 1:11 | 34.9 ± 12.5 ya | 43 ± 7.6 ma | Adults |

| Aeschlimann 2017 (60) | MTX | CYC | Clinical | 6 (2.9–15.2) md | 27 total (10 I, 5 C) | 7:20 | 12.4 (9.1–14.4) d | 6 me | Children |

| Sun 2017 (67) | CYC | MTX | Clinical; Angio | 18 (4–42) yc I, 18 (5–70) yc C | 58 (46 I, 12 C) | 15:43 | 36 (27–51) yc I, 35 (25–49) yc C | 6 me | Adults |

| Dai 2020 (83) | LEF | CYC | Clinical | 20 (5–50) md | 131 (53 I, 78 C) | 29:102 | 34.5 ± 13.6ya | 9 me | Both |

| Wu 2020 (93) | LEF | MTX | Clinical; Angio; relapse | 11 (4–56) md | 68 (40 I, 28 C) | 12:56 | 34 (24–45) yd | 12 me | NA |

| Ying 2020 (94) | LEF | CYC | Clinical; Angio | 5 (1–36) md I, 12 (2.5–48) md C | 92 (47 I, 45 C) | 26:66 | 33.5 (24.5–41) yd I, 31 (26.5–49) yd C | 12 me | NA |

| Rongyi 2021 (96) | HCQ | Other DMARDs | Angio | NA | 50 (21 I, 29 C) | NA | NA | 6 me | NA |

| Mekinian 2015 (55) | TNFi | Tocilizumab | Clinical; relapse | NA | 49 | 10:39 | 42 (20–55) yc | 16 (2–85) mc | Adults |

| bDMARDs | cDMARDs | ||||||||

| Gudbrandsson 2017 (61) | TNFi | cDMARDs | Clinical; Angio | NA | 97 | 11:86 | 33.9 ± 15 ya | 11.7 ± 12 ya | Both |

| Kong 2018 (69) | Tocilizumab | CYC | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS | 10 (5–43) md I, 2 (1–24) md C | 24 (9 I, 15 C) | 6:18 | 32.11 ± 11.76 ya I, 43 ± 16.68 ya C | 6 me | Both |

| Wang 2019 (78) | Tocilizumab | CYC | Clinical; ∆CS | NA | 49 (27 I, 22 C) | NA | NA | 6 me | NA |

| Pan 2020 (90) | Tocilizumab | cDMARDs | Clinical; ∆CS | 12 (6–168) md I, 57 (5–282) md C | 22 (11 I, 11 C) | 1:21 | 37.02 ± 13.16ya | 6 me | Both |

| Campochiaro 2020 (80) | TNFi | Tocilizumab | Clinical | 119.5 ± 110.1 ma | 50 (61 I, 17 C)$ | 1:9 | 39.1 ± 12.1 ya | 2 ye | Both |

| Langford 2017 (63) | Abatacept | Placebo | Relapse |

5.1 yf (I) 0.91f (C) |

26 (11 I, 15 C) | 4:22 |

30.2 yf (I) 28.6f (C) |

12 me | Adults |

| Shao 2017 (65) | Curcumin | Placebo | Clinical | NA | 246 (120 I, 126 C) | 104: 142 |

36.2 ya (I) 34.7 ya (C) |

4 we | Adults |

| Shi 2016 (66) | Resveratrol | Placebo | Clinical | NA | 220 (112 I, 108 C) | 79: 141 | 33.47 ± 15.52 yc | 12 we | Both |

| Nakaoka 2018 (72) | Tocilizumab | Placebo | Relapse | 5.02 ± 5.94 yc | 36 (18 I, 18 C) | 5: 31 | 30.95 ± 15.80 yc |

19 we (I) 12.8 we (P) |

Both |

| Nakaoka 2020 (89) | Tocilizumab* | - | Clinical; Angio; ∆CS; relapse; QOL | 5.02 ± 5.94 yc | 36 | 5: 31 | 30.95 ± 15.80 yc | 96 we | Both |

m months, w week, y years, Angio serial angiographic assessment, ∆CS change in corticosteroid dose before and after, CYC cyclophosphamide, DMARDs disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, bDMARDs biologic DMARDs, cDMARDs conventional DMARDs, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, LEF leflunomide, MTX methotrexate, PET positron emission tomography computerized tomography, QOL quality of life, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

*Open label extension of 46 patients

$Courses of treatment

aMean ± standard deviation

bMean with range

cMedian with range

dMedian with interquartile range

eMean

fMedian

gRange

.

Assessment of risk of bias and study quality

Table 3 presents risk of bias of the RCTs assessed using RoB 2 tool. Two studies (assessing resveratrol and curcumin versus placebo) had high risk of bias due to lack of appropriate analysis for assignment of intervention and concerns regarding outcome measurement and reporting. The RCT reporting abatacept versus placebo had some concern of risk of bias due to baseline imbalances in proportions of newly diagnosed TAK patients (none in abatacept arm, 27% in placebo arm) as well as lesser median disease duration in the placebo arm (0.91 years) compared to abatacept (5.1 years). This suggested that patients in the placebo arm possibly had less severe disease. The RCT reporting tocilizumab versus placebo was deemed to have some concern about risk of bias due to lack of information about allocation concealment and the unavailability of a pre-defined statistical analysis plan.

Table 3.

Risk of bias for randomized controlled trials in patients with Takayasu arteritis

| Study (reference no) | Intervention | Randomization | Effect of assignmentof intervention | Missing outcomedata | Measurementof outcome | Selection ofreported result | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langford 2017 (63) | Abatacept | Some concern | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concern |

| Shao 2017 (65) | Curcumin | Some concern | High | Some concern | High | High | High |

| Shi 2016 (66) | Resveratrol | Some concern | High | Low | High | High | High |

| Nakaoka 2018 (72) | Tocilizumab | Some concern | Low | Low | Low | Some concern | Some concern |

Table 4 presents the assessment of uncontrolled observational studies using the NOS. Most studies lost points due to lack of a comparator arm. Table 5 presents the evaluation of controlled observational using the NOS. Most studies had moderate quality as per the NOS.

Table 4.

Assessment of study quality—uncontrolled observational studies using Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Study (reference no) | Intervention | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shelhamer 1985 (32) | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Hoffman 1994 (33) | MTX | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Hahn 1998 (34) | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Valsakumar 2003 (35) | AZA | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| de Franciscis 2007 (38) | MTX + CYC | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Shinjo 2007 (39) | MMF | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Goel 2010 (41) | MMF | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| de Souza 2012 (42) | LEF | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Stern 2014 (53) | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Li 2016 (58) | MMF | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Ohigashi 2017 (64) | MTX, CSA, AZA, TAC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Cui 2020 (82) | LEF | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Wei 2021 (97) | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mustapha 2020 (99) | LEF | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Li 2020 (86) | Tofacitinib | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Nakagomi 2018 (71) | Rituximab | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Pazzola 2018 (75) | Rituximab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Hoffman 2004 (36) | TNFi (ETAN, IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Baldissera 2007 (37) | TNFi (IFX, ADA, ETAN) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Molloy 2010 (40) | TNFi (IFX, ETAN) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mekininan 2012 (43) | TNFi (IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Quartuccio 2012 (44) | TNFi (IFX) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Schmidt 2012 (45) | TNFi IIFX, ADA, ETAN) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Tombetti 2013 (48) | TNFi (IFX, ADA, GOL) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Serra 2014 (52) | TNFi (ADA, IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Youngstein 2014 (54) | TNFi (IFX, ADA, ETAN) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Kleinmann 2017 (62) | TNFi (IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Novikov 2018 (73) | TNFi (CER) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Park 2018 (74) | TNFi (IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Banerjee 2020 (79) | TNFi (IFX) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Campochiaro 2020 (81) | TNFi (IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mertz 2020 (88) | TNFi (IFX) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Erbasan 2020 (98) | TNFi (IFX), Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Abisror 2013 (46) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Goel 2013 (47) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Tombetti 2013 (49) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Canas 2014 (50) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Loricera 2014 (51) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Novikov 2015 (56) | Tocilizumab | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Loricera 2016 (59) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Zhou 2017 (68) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mekinian 2018 (70) | Tocilizumab | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Kato M 2019 (76) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Shah 2019 (77) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Gon 2020 (84) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Kilic 2020 (85) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Mekinian 2020 (87) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Prieto-Pena 2020 (91) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Wang 2020 (92) | Tocilizumab | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Isobe 2021 (95) | Tocilizumab | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

AZA azathioprine, ADA adalimumab, CER certolizumab, CYC cyclophosphamide, ETAN etanercept, GOL golimumab, IFX infliximab, LEF leflunomide, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MTX methotrexate, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

Table 5.

Assessment of study quality—observational studies* with control group using Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Study (reference no) | Intervention | Comparator | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Souza 2016 (57) | LEF | other DMARDs | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Aeschlimann 2017 (60) | MTX | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Sun 2017 (67) | CYC | MTX | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Dai 2020 (83) | LEF | CYC | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Wu 2020 (93) | LEF | MTX | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Ying 2020 (94) | LEF | CYC | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Mekinian 2015 (55) | TNFi | Tocilizumab | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Gudbrandsson 2017 (61) | TNFi | cDMARDs | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Kong 2018 (69) | Tocilizumab | CYC | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Wang 2019 (78) | Tocilizumab | CYC | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Pan 2020 (90) | Tocilizumab | cDMARDs | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Campochiaro 2020 (80) | TNFi | Tocilizumab | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

CYC cyclophosphamide, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, cDMARDs conventional DMARDs, LEF leflunomide, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, MTX methotrexate, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

*Newcastle-Ottawa Scale could not be assessed for Rongyi 2021 (95) due to inability to access the full text of the paper

Publication bias

Formal assessment of publication bias was possible only for studies with at least 10 events, due to the low power of the egger test when there are smaller number of observations [25]. This could be assessed for proportions of patients with at least partial clinical response with tocilizumab (17 studies, p value for egger test 0.675, Supplementary Fig. 1a) and TNFi (15 studies, p value for egger test 0.464, Supplementary Fig. 1b), angiographic retardation or stabilization with tocilizumab (12 studies, p value for egger test 0.742, Supplementary Fig. 1c) and TNFi (10 studies, p value for egger test 0.873, Supplementary Fig. 1d). Although the funnel plot for the studies assessing at least partial clinical response to TNFi visually appeared to be asymmetrical, the formal egger test could not detect small-study effects; hence, publication bias was unlikely. A formal assessment of publication bias was not feasible for other uncontrolled studies since none of these outcomes comprised at least ten studies.

Effectiveness of DMARDs

Results are described for conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs) followed by biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs). Subsequently, results comparing two DMARDs or DMARD categories are discussed. Due to the paucity of studies in children alone, the planned subgroup analyses based on whether subjects were adults or children were not feasible.

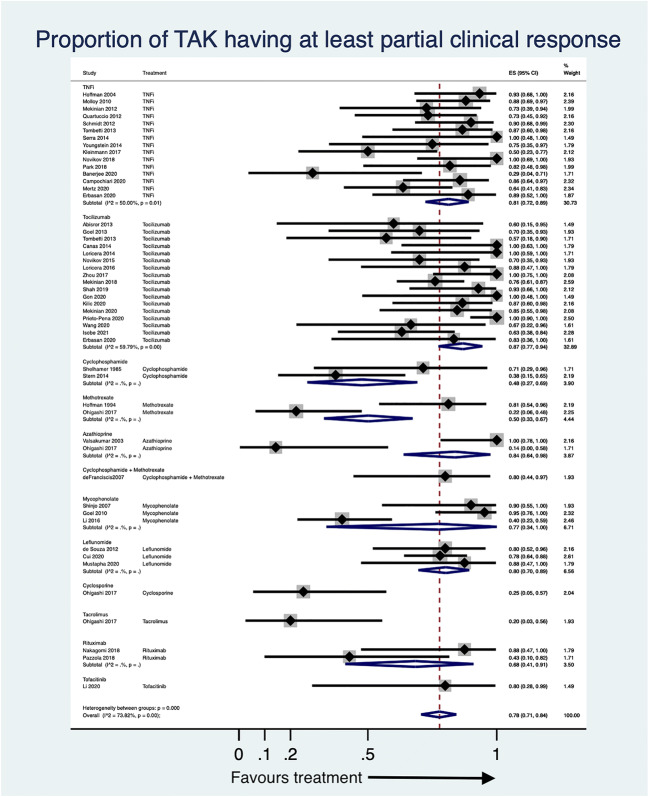

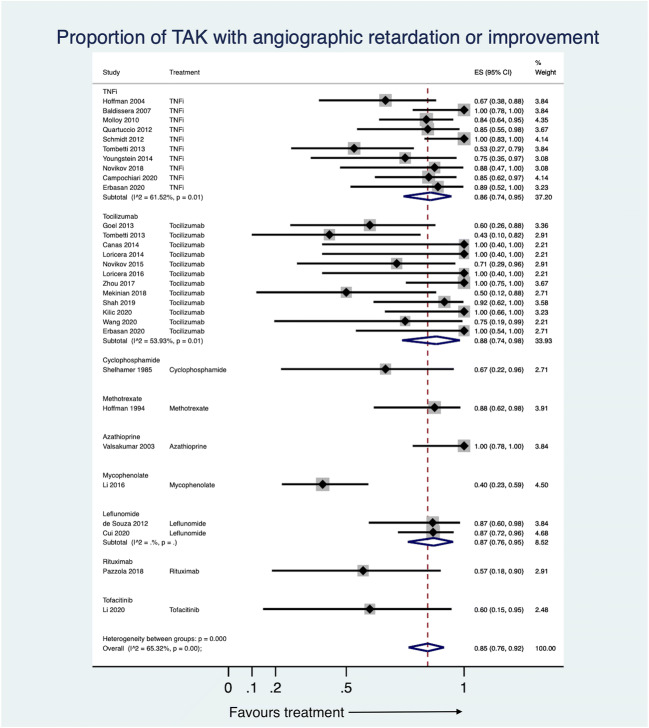

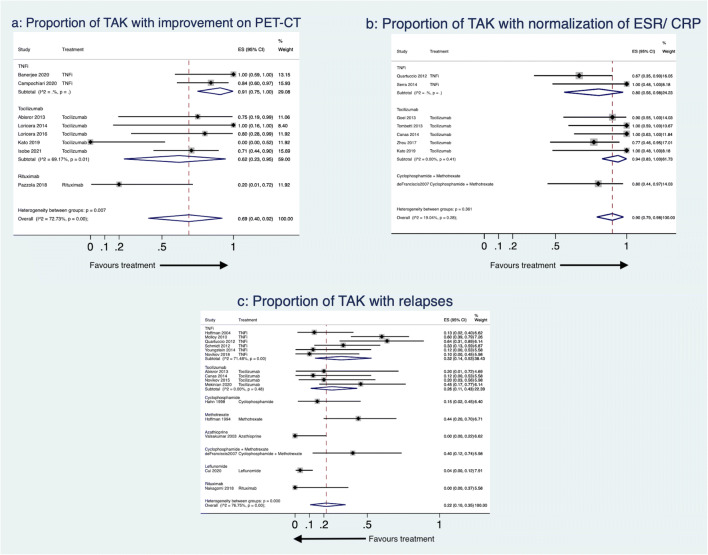

Summary results

Following treatment with DMARDs, the proportion of patients with TAK attaining at least partial clinical remission was 78% (95% CI 71–84%, 46 studies, 674 patients, I2 73.82%, Fig. 2). Angiographic stabilization was attained by 85% (95% CI 76–92%, 29 studies, 366 patients, I2 65.32%, Fig. 3). Improvement on PET-CT was observed in 69% (95% CI 40–92%, 8 studies, 64 patients, I2 72.73%, Fig. 4a). Normalization of inflammatory markers was noted in 90% (95% CI 79–98%, 8 studies, 70 patients, I2 19.04%, Fig. 4b). Relapses occurred in 22% (95% CI 10–35%, 16 studies, 239 patients, I2 76.75%, Fig. 4c). Adverse events were observed in 18% (95% CI 11–25%, 36 studies, 532 patients, I2 68.45%, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Infections occurred in 6% (95% CI 3–11%, 37 studies, 563 patients, I2 60.63%, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Some studies presented median doses of prednisolone before and after DMARDs, whereas others presented mean doses. The median reduction in prednisolone dose following DMARDs was 81% (95% CI 72–90%, 14 studies, I2 71.85%, Supplementary Fig. 3a). The mean reduction in prednisolone dose following DMARDs was 65% (95% CI 58–72%, 18 studies, I2 58.63%, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Except for the proportion of patients attaining normalization of inflammatory markers, all the other pooled estimates had a significant degree of heterogeneity.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for proportions of patients with Takayasu arteritis (TAK) with at least a partial clinical response from observational studies. 95% CI 95% confidence intervals, ES effect size, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for proportions of patients with Takayasu arteritis (TAK) with angiographic stabilization from observational studies. 95% CI 95% confidence intervals, ES effect size, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for proportions of patients with Takayasu arteritis (TAK) from observational studies with a improvement on PET-CT, b normalization of inflammatory markers and c relapses. 95% CI 95% confidence intervals, CRP C-reactive protein, ES effect size, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, PET-CT positron emission tomography computerized tomography, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors

Secondary analyses based on DMARD type are reported forthwith. There was only one study reporting outcomes in TAK with targeted synthetic DMARD (tofacitinib)[86]. Pooled proportion of TAK with at least a partial clinical response with bDMARDs was 84% (95% CI 77–89%, 33 studies, 449 patients, I2 55.92%) and with cDMARDs was 64% (95% CI 47–80%, 15 studies, 220 patients, I2 84.37%). Angiographic stabilization with bDMARDs was observed in 86% (95% CI 78–93%, 22 studies, 241 patients, I2 56.07%) and with cDMARDs in 81% (95% CI 59–97%, 6 studies, 120 patients, I2 83.55%). All studies on PET-CT improvement were in patients on bDMARDs. Normalization of inflammatory markers was seen with bDMARDs in 92% (95% CI 79–99%, 7 studies, 60 patients, I2 26.34%), one single study reported this in cDMARDs in 80% (95% CI 44–97%, 10 patients). Relapses were identified with bDMARDs in 26% (95% CI 13–41%, 11 studies, 129 patients, I2 63.4%) and with cDMARDs in 15% (95% CI 1–37%, 5 studies, 110 patients). Adverse events were noted in 21% on bDMARDs (95% CI 14–28%, 27 studies, 364 patients, I2 57.27%) and 13% on cDMARDs (95% CI 2–30%, 8 studies, 163 patients, I2 82.54%). Infections occurred in 8% on bDMARDs (95% CI 3–14%, 28 studies, 379 patients, I2 60.91%) and 2% on cDMARDs (95% CI 0–6%, 8 studies, 179 patients, I2 33.14%). All studies reporting median dose reduction in prednisolone were bDMARDs. The mean reduction in prednisolone dose following bDMARDs was 70% (95% CI 62–77%, 12 studies, I2 43.07%) and following cDMARDs was 63% (95% CI 52–74%, 5 studies, I2 52.92%). The heterogeneity in pooled estimates could be partially explained by subgrouping type of DMARDs for the outcomes of infectious adverse events and mean reduction in prednisolone dose but not for the other outcomes.

Conventional DMARDs

Methotrexate

Five observational studies assessed methotrexate in TAK [33, 60, 64, 67, 93]. Among the two studies reporting outcomes with methotrexate alone [33, 64], pooled proportion of patients attaining at least partial clinical response was 50% (95% CI 33–67%, 34 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 2). One study assessed angiographic stabilization (88%, 95%CI 62–98%, 16 patients, Fig. 3)[33] and proportions of relapses (44%, 95%CI 20–70%, 16 patients, Fig. 4c)[33]. The three studies comparing methotrexate with other DMARDs [60, 67, 93] shall be discussed subsequently.

Azathioprine

Two observational studies assessed azathioprine in TAK [35, 64]. The pooled proportion of patients attaining at least a partial clinical response was 84% (95% CI 64–98%, 22 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 2). One study with 15 patients assessed angiographic stabilization (100%, 95% CI 78–100%, Fig. 3), relapses (0%, 95% CI 0–22%, Fig. 4c) and proportions of patients with adverse events (0%, 95% CI 0–22%, Supplementary Fig. 2a)[35].

Cyclophosphamide

Ten observational studies evaluated cyclophosphamide in TAK [32, 34, 53, 60, 67, 69, 78, 83, 94, 97], including three uncontrolled studies [32, 34, 53] where no direct comparison could be made with DMARDs. Pooled proportion of patients with at least partial clinical response was 48% (95% CI 27–69%, 2 studies, 23 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 2). One study each assessed angiographic stabilization (67%, 95% CI 22–96%, 6 patients, Fig. 3)[32], relapses (15%, 95% CI 2–45%, 13 patients, Fig. 4c)[34] and proportion of patients with adverse events (100%, 95% CI 59–100%, 7 patients, Supplementary Fig. 2a)[32]. Wei et al. reported that the event free survival for patients on cyclophosphamide (compared to those without) at 1 year was 100% (versus 86%) and at 5 years was 72.2% (versus 46.3%) [97]. Using multivariable-adjusted Cox regression, the use of cyclophosphamide was associated with decreased hazard of poor prognosis by 38% (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.39–0.98) [97].

The remaining six studies comparing cyclophosphamide to other therapies shall be discussed subsequently [60, 67, 69, 78, 83, 94].

Mycophenolate mofetil

Three uncontrolled observational studies assessed the role of mycophenolate mofetil in TAK [39, 41, 58]. The pooled proportion of patients attaining at least a partial clinical response was 77% (95% CI 34–100%, 3 studies, 61 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 2). One study reported angiographic stabilization in 40% (95% CI 23–59%, 30 patients, Fig. 3)[58]. The pooled reduction in mean prednisolone dose following mycophenolate mofetil was 66% (95% CI 47–83%, 3 studies, I2 not assessable, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Adverse events were seen in 9% patients (95% CI 2–18%, 3 studies, 61 patients, I2 not assessable, Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Leflunomide

Six observational studies (and a seventh study, a longer-term follow-up of one of the previous ones) assessed leflunomide in TAK [42, 57, 82, 83, 93, 94, 99]. For the three uncontrolled observational studies, the pooled proportion of patients achieving at least a partial clinical response was 80% (95% CI 70–89%, 3 studies, 73 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 2), angiographic stabilization was observed in 87% (95% CI 76–95%, 2 studies, 53 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 3) and reduction of mean prednisolone dose following leflunomide was 59% (95% CI 46–71%, 2 studies, I2 not assessable, Supplementary Fig. 3b). One study assessed relapses (4%, 95% CI 0–12%, 56 patients, Fig. 4c) [82]. The pooled proportion of patients with adverse events was 8% (95% CI 1–19%, 3 studies, 80 patients, I2 not assessable, Supplementary Fig. 2a).

The four studies comparing leflunomide with other DMARDs [57, 83, 93, 94] shall be subsequently discussed.

Cyclosporine

One observational study reported at least partial clinical response in 25% TAK patients (95% CI 5–57%, 12 patients, Fig. 2) using cyclosporine[64].

Tacrolimus

One observational study reported at least partial clinical response in 20% TAK patients (95% CI 3–56%, 10 patients, Fig. 2) using tacrolimus[64].

Cyclophosphamide and methotrexate

A single observational study assessed responses in 10 TAK patients with a regimen of cyclophosphamide followed by methotrexate. At least a partial clinical response was observed in 80% (95% CI 44–97%, Fig. 2). Normalization of inflammatory markers was seen in 80% (95% CI 44–97%, Fig. 4b). Relapses were observed in 40% (95% CI 12–74%, Fig. 4c) [38].

Biologic DMARDs

Tocilizumab

One RCT [72] with a longer-term open label follow-up [89] and 22 observational studies [46, 47, 49–51, 56, 59, 68–70, 76–78,80,84, 85, 87, 90–92, 95, 98] evaluated tocilizumab in TAK. Eighteen patients each with relapsing TAK were randomized to receive tocilizumab 162 mg subcutaneous weekly or matching placebo. In the primary ITT analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) for time to relapse with tocilizumab versus placebo was 0.41 (95% CI 0.15 to 1.10). Although the effect size was large in favour of tocilizumab, the results did not attain statistical significance at the 5% level of difference in this primary analysis. Using a per-protocol analysis, HR for time to relapse with tocilizumab versus placebo was 0.34 (95% CI 0.11–1.00). At 24 weeks, relapse free rate (95% CI) was 50.6 (25.4–75.8)% with tocilizumab and 22.9 (0.4–45.4)% with placebo. Tocilizumab was not associated with different risk of adverse events (risk ratio 1.27, 95% CI 0.82–1.98) or serious adverse events (risk ratio 0.5, 95% CI 0.05–5.04) when compared with placebo [72]. A longer-term open-label extension of this trial was recently published, wherein patients in both arms were continued on tocilizumab until 96 weeks. There was significant lowering of daily prednisolone dose from study entry till 96 weeks (mean difference −0.12, 95% CI −0.154 to −0.087) mg/kg/day. Nearly one-half of enrolled patients could reduce their dose of prednisolone below 0.1 mg/kg/day. Of the 28 patients for whom serial angiography could be assessed, only 4 showed progression of vascular involvement. Meaningful differences in quality of life parameters assessed by using the SF-36 were observed by 24 weeks and maintained till 96 weeks. The major adverse effect associated with tocilizumab was infections (218.8 per 100 person-years), serious adverse events occurred at 17.4 per 100 person-years; however, there were no deaths. Fourteen patients experienced relapses while being enrolled in the trial (relapse rate 29.4 per 100 person-years) [89]. Overall, the data from these two studies demonstrates promise for the use of tocilizumab in TAK in terms of reduction of relapses and glucocorticoid exposure, improvement in quality of life, as well as retardation of angiographic progression of disease in nearly 83% patients.

Pooling data available from observational studies, tocilizumab was effective in attaining at least a partial clinical response in 87% patients (95% CI 77–94%, 17 studies, 226 patients, I2 59.79%, Fig. 2) although the results were heterogenous. Excluding Prieto-Pena 2020, I2 reduced below 50%. The pooled proportion of patients attaining angiographic stabilization with tocilizumab was 88% (95% CI 74–98%, 12 studies, 86 patients, I2 53.93%, Fig. 3) with considerable heterogeneity. Excluding either of Tombetti 2013, Zhou 2017 or Mekinian 2018 decreased I2 below 50%. Improvement in PET-CT with tocilizumab was seen in 62% (95% CI 23–95%, 5 studies, 33 patients, I2 69.17%, Fig. 4a) patients. The heterogeneity was entirely explainable due to Kato 2019. Normalization of inflammatory markers was seen in nearly all patients (94%, 95% CI 83–100%, 5 studies, 43 patients, I2 0%, Fig. 4b). Normalization of CRP with tocilizumab is due to a direct effect of the drug on CRP production from the liver and no more reliably reflects systemic inflammation in patients treated with tocilizumab [100]. Relapses were seen in 26% (95% CI 11–43%, 4 studies, 34 patients, I2 0%, Fig. 4c) patients treated with tocilizumab over follow-up durations ranging from 6 to 18.5 months. Patients on tocilizumab could obtain a reduction in median prednisolone dose by 83% (95% CI 71–92%, 5 studies, I2 65.94%, Supplementary Fig. 3a) or mean daily corticosteroid doses by 73% (95% CI 62–82%, 8 studies, I2 51.29%, Supplementary Fig. 3b), although estimates were heterogenous. For reduction in mean prednisolone dose, excluding either of Canas 2014, Loricera 2014, Kato 2019 or Kilic 2020 reduced I2 below 50%. However, exclusion of individual studies could not ameliorate heterogeneity for pooled estimates of mean prednisolone dose. Separately, Gon et al. reported a reduction in mean prednisolone dose by 9.7 mg 1 year following tocilizumab therapy [84]. The pooled proportion of patients experiencing any adverse effect with tocilizumab was 23% (95% CI 12–35%, 13 studies, 162 patients, I2 53.84%, Supplementary Fig. 2a) with considerable heterogeneity between estimates. I2 dropped below 50% by excluding either of Mekinian 2018 or Mekinian 2020. The two studies comparing tocilizumab with TNF inhibitors [55, 80] or with other comparators [69, 78, 90] shall be discussed subsequently.

TNF inhibitors

The various tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF) inhibitors (TNFi) used in TAK have been infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab and certolizumab pegol. We have considered this evidence for TNFi as a whole rather than for individual TNFi. Nineteen observational studies evaluated TNFi in TAK [36, 37, 40, 43–45, 48, 52, 54, 55, 61, 62, 73, 74, 79–81, 88, 98]. Pooling data across studies, TNFi were effective in attaining at least partial clinical response in 81% patients (95%CI 72–89%, 15 studies, 208 patients, I2 50%, Fig. 2) with significant heterogeneity across studies. Excluding either of Kleinmann 2017, Novikov 2018, Banerjee 2020 or Mertz 2020 reduced I2 below 50%. The proportion of patients attaining angiographic stabilization of TAK was 86% (95% CI 74–95%, 10 studies, 148 patients, I2 61.52%, Fig. 3) with considerable heterogeneity across studies. I2 reduced below 50% by excluding either Schmidt 2012 or Tombetti 2013 from the pooled data. Improvement in PET-CT was seen in 91% (95% CI 75–100%, 2 studies, 26 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 4a). Park et al. reported a decrease in median (interquartile range) of PET Vascular Activity Score from 12 (11–15.5) to 11 (8–12) with infliximab therapy over a follow-up period of 30 weeks[74]. Normalization of inflammatory markers was seen in 80% (95% CI 56–98%, 2 studies, 17 patients, I2 not assessable, Fig. 4b). Relapses were seen in 32% (95% CI 14–53%, 6 studies, 87 patients, I2 71.48%, Fig. 4c) with heterogenous estimates across studies of varying follow-up durations. The pooled percentage reduction before and after TNFi in median prednisolone dose was 81% (95% CI 61–95%, 8 studies, I2 79.85%, Supplementary Fig. 3a), in mean prednisolone dose was 61% (95%CI 49–73%, 3 studies, I2 not assessable, Supplementary Fig. 3b), with considerable heterogeneity across studies. The pooled proportion of patients with adverse events was 19% (95%CI 10–31%, 12 studies 187 patients, I2 64.30%, Supplementary Fig. 2a) with significant heterogeneity. However, excluding any individual study did not reduce the I2 below 50% for outcomes of relapses, adverse events or median reduction of prednisolone dose. Quartuccio et al. assessed improvement in health-related quality of life measured using the 36-item short-form (SF-36) questionnaire in ten patients before and after infliximab in 10 patients with TAK. They observed significant improvement in bodily pain, general health and vitality components of the SF-36 [44].

The three studies comparing TNFi with other DMARDs [55, 61, 80] shall be discussed subsequently.

Abatacept

Abatacept blocks co-stimulatory signals to T lymphocytes, thereby exerting its anti-inflammatory activity. A single RCT has evaluated abatacept in TAK. Using a withdrawal design, patients were initially administered intravenous abatacept (10 mg/kg) at day 1, 15, 29 and thereafter at 8 weeks. After a period of 12 weeks, those who were in remission were randomized to receive abatacept (n = 11) or matching intravenous placebo (n = 15) every 4 weeks. At 12 months, 22% on abatacept (and 40% on placebo) were in remission. Both arms had similar median duration of remission (5.5 months abatacept, 5.7 months placebo) and similar proportions of adverse events [63]. Overall, the data supporting the use of abatacept is not promising, as opposed to GCA where encouraging results have been found [101].

Rituximab

Two observational studies assessed rituximab in TAK [71, 75]. The pooled proportion of patients with at least a partial clinical response was 68% (95% CI 41–91%, 15 patients, Fig. 2). One study each assessed angiographic stabilization (57%, 95% CI 18–90%, 7 patients, Fig. 3) [75], reduction of disease activity assessed by PET-CT (20%, 95% CI 1–72%, 5 patients, Fig. 4a) [75] and relapses (0%, 95% CI 0–37%, 8 patients, Fig. 4c) [71]. Nakagomi et al. reported reduction in median prednisolone dose by 76% (95% CI 57–89%, Supplementary Fig. 3a)[71]. Pazzola et al. reported reduction in mean prednisolone dose by 65% (95% CI 45–80%, Supplementary Fig. 3b) [75]. Adverse events were observed in 14% patients (95% CI 0–39%, 2 studies, 15 patients, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Heterogeneity could not be quantified for any of these pooled results due to paucity of studies.

Small molecules and natural products

Tofacitinib

One observational study reported the use of tofacitinib in 5 patients with TAK. At least a partial clinical response was observed in 80% (95% CI 28–99%, Fig. 2), and angiographic stabilization seen in 60% (95% CI 15–95%, Fig. 3). Reduction in mean prednisolone dose of 27% (95% CI 12–51%, Supplementary Fig. 3b) following tofacitinib was observed. None of the patients had adverse events (95% CI 0–52%, Supplementary Fig. 2a)[86].

Resveratrol

Resveratrol is a naturally occurring compound with demonstrable in vitro anti-TNF activity, evaluated in a RCT involving 220 patients with TAK (112 resveratrol, 108 placebo). At 12 weeks, the reduction in mean Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) was greater in patients treated with resveratrol (29 to 4) when compared with placebo (28 to 24). The study had high risk of bias. The follow-up duration was too short to be meaningful, there was no assessment of angiographic progression and safety data was unavailable [66].

Curcumin

Curcumin is another naturally occurring compound which has in vitro anti-TNF activity, evaluated in a RCT involving 246 patients with TAK (120 curcumin, 126 placebo). At 4 weeks, BVAS scores decreased significantly in the curcumin group, whereas they remained similar in the placebo group. The study had high risk of bias. Short follow-up duration, lack of assessment of angiography and lack of safety data were further limitations of the study [65].

Studies comparing DMARDs

Methotrexate with cyclophosphamide

Two observational studies compared methotrexate with cyclophosphamide [60, 67]. There was no difference in the proportion of patients attaining at least partial clinical response at 6 months with methotrexate or cyclophosphamide (pooled risk ratio for methotrexate versus cyclophosphamide 1.01, 95% CI 0.7–1.45, 22 patients on methotrexate and 51 on cyclophosphamide, I2 0%, Supplementary Fig. 4a). One of the studies assessed angiographic stabilization; there were no differences between the two drugs (risk ratio for methotrexate versus cyclophosphamide 1.07, 95% CI 0.79–1.43, 12 patients on methotrexate and 46 on cyclophosphamide). Whereas wall enhancement on magnetic resonance angiography reduced in the patients treated with cyclophosphamide, there was no change observed in methotrexate-treated patients. However, stenosis or wall thickening did not differ in serial follow-up in either group. Greater reductions in mean ITAS2010 were seen with cyclophosphamide (4.7) than with methotrexate (2.2) in this study. Three patients treated with cyclophosphamide discontinued the same due to adverse events (none with methotrexate). There was one death in the cyclophosphamide arm (none with methotrexate) [67].

Cyclophosphamide with Leflunomide

Two observational studies compared cyclophosphamide with leflunomide; they are described separately[83, 94]. Dai et al. compared 78 patients treated with cyclophosphamide with 53 treated with leflunomide (further evaluated in 54 patients on cyclophosphamide and 23 on leflunomide after propensity score matching). The risk ratio for attaining at least partial clinical remission with cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide at 9 months was 0.2 (95% CI 0.1–0.6; after matching 0.8, 95% CI 0.3–2.1) and for complete remission was 0.3 (95% CI 0.1–0.6; after matching 0.1, 95% CI 0.0–0.6). The risk ratio for all adverse events for cyclophosphamide compared to leflunomide was 5.78 (95% CI 2.18–15.32). There was one death in the patients treated with leflunomide (none in the cyclophosphamide treated patients) [83]. Ying et al. compared 45 patients treated with cyclophosphamide with 47 treated with leflunomide (further evaluated in 34 patients on cyclophosphamide and 41 on leflunomide after propensity score matching). At 6 months, risk ratio for at least a partial clinical response for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide was 0.3 (95% CI 0.1–0.95) before matching and 0.33 (95% CI 0.1–1.1) after matching. Risk ratio for complete response for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide was 0.21 (95% CI 0.08–0.52) before matching and 0.20 (95% CI 0.07–0.54) after matching. At 12 months, risk ratio for at least a partial clinical response for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide was 0.23 (95% CI 0.05–1.21) before matching and 0.70 (95% CI 0.14–3.41) after matching. Risk ratio for complete response for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide was 0.22 (95% CI 0.08–0.65) before matching and 0.33 (95% CI 0.11–1.01) after matching. Similar proportions of unmatched patients attained angiographic stabilization with cyclophosphamide or leflunomide (risk ratio for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide at 6 months 0.88, 95% CI 0.74–1.05, and at 12 months 0.91, 95% CI 0.77–1.07). A higher risk of adverse events with cyclophosphamide was observed in the unmatched cohort (risk ratio for cyclophosphamide versus leflunomide 2.09, 95% CI 1.10–3.96)[94]. Although some of these confidence intervals for clinical response crossed 1, the magnitude of effect sizes favoured leflunomide over cyclophosphamide. Overall, leflunomide appeared to have a favourable clinical response and safety profile when compared with cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in TAK.

Leflunomide with other DMARDs

A longer-term follow up [57] (for 43 ± 7.6 months) of an uncontrolled observational study on leflunomide in TAK previously discussed [42] compared 5 patients from the original cohort who continued leflunomide with seven others who were changed to other DMARDs (infliximab, adalimumab or azathioprine) during this time period. Similar proportions of angiographic stabilization were observed (risk ratio for leflunomide versus other DMARDs 1.4, 95% CI 0.88–2.24). The median time to prednisolone withdrawal was 20.8 months for leflunomide and 34.1 for other DMARDs. Mean cumulative prednisolone dose was higher in other DMARD-treated patients (13.3 g) compared to leflunomide (6.3 g)[57].

Leflunomide with methotrexate

A single observational study compared leflunomide (40 patients) with methotrexate (28 patients) in TAK. Similar proportions of patients attained clinical responses at 6 months (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate for at least partial clinical response 1.13, 95% 0.88–1.46, and for complete response 1.35, 95% CI 0.91–2.01, 28 methotrexate, 40 leflunomide), 9 months (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate for at least partial clinical response 1.07, 95% 0.91–1.25, and for complete response 1.16, 95% CI 0.83–1.62, 26 methotrexate, 37 leflunomide) and 12 months (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate for at least partial clinical response 1.04, 95% 0.88–1.23, and for complete response 1.13, 95% CI 0.83–1.54, 26 methotrexate, 37 leflunomide). Angiographic stabilization was similar in both groups (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate at 6 months 1.02, 95% CI 0.90–1.16, 28 methotrexate, 40 leflunomide, and at 12 months 1.01. 95% CI 0.84–1.21, 26 methotrexate, 37 leflunomide). Frequency of relapses was similar in both groups at 12 months (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate 0.47, 95% CI 0.08–2.61, 26 methotrexate, 37 leflunomide) with no difference in proportions of patients developing adverse effects (risk ratio for leflunomide versus methotrexate 1.05, 95% CI 0.42–2.62, 26 methotrexate, 37 leflunomide) [93].

Hydroxychloroquine with other DMARDs

A single cohort study compared 21 TAK patients treated with hydroxychloroquine (along with other DMARDs) with 29 others not receiving hydroxychloroquine. At 6 months, 19% patients on hydroxychloroquine had progression of TAK on serial angiographic assessment, as opposed to 51.7% patients not receiving hydroxychloroquine. Hydroxychloroquine use was associated with reduced rate of angiographic progression (HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.08–0.94) even when adjusted for confounding factors of age and concomitant administration of tocilizumab[96].

TNFi with tocilizumab

Two observational studies provided comparative results for TNFi versus tocilizumab in TAK [55, 80]. Similar proportions of patients attained at least a partial clinical response with either treatment at 12 months (pooled risk ratio for TNFi versus tocilizumab 0.97, 95% CI 0.58–1.62, 92 TNFi and 24 tocilizumab treatment courses, Supplementary Fig. 4b) with considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2 80.1%). Campochiaro et al. further observed similar risk of continuation of drug at 24 months (suggesting effectiveness, risk ratio for TNFi versus tocilizumab 1.63, 95% CI 0.90–2.96, 61 TNFi and 17 tocilizumab treatment courses)[80]. Mekinian et al. observed similar proportions of vascular complications (risk ratio for TNFi versus tocilizumab 1.75, 95% CI 0.23–13.08), vascular interventions (risk ratio for TNFi versus tocilizumab 1.5, 95% CI 0.20–11.47) and adverse events (risk ratio for TNFi versus tocilizumab 1.08, 95% CI 0.36–3.29) during 56 courses of TNFi and 14 courses of tocilizumab treatment. Relapse-free survival at 3 years was similar (91% for TNFi, 85.7% for tocilizumab)[55].

Biologic DMARDs with conventional DMARDs

Five observational studies compared biologic with conventional DMARDs [55, 61, 69, 78, 90]. Pooled risk ratio of clinical response with biologic versus conventional DMARDs was 1.99 (95% CI 0.99–4.01, 2 studies, 41 biologic, 55 conventional, I2 0%, Supplementary Fig. 4c) and for angiographic stabilization was 1.32 (95% CI 0.98–1.78, 41 biologic, 55 conventional, I2 46.5%, Supplementary Fig. 4d)[61, 69]. Kong et al. reported similar risk of adverse events with tocilizumab or cyclophosphamide (risk ratio for tocilizumab versus cyclophosphamide 1.67, 95% CI 0.12–23.49). Mean reduction in ITAS2010 was 3 for tocilizumab and 1.8 for cyclophosphamide treated patients. Median reduction in prednisolone dose following DMARD was 20 mg in both groups[69]. Wang et al. compared outcomes in 27 patients treated with tocilizumab with 22 patients treated with cyclophosphamide at 6 months. The reported median ITAS 2010 scores at 6 months in both groups were similar (0 versus 0), so also were the median number of active items on NIH disease activity measures (0 versus 0). Proportions of adverse events were higher with cyclophosphamide (54.5%) than with tocilizumab (22.2%). The study reported greater lowering of prednisolone dose in the tocilizumab group when compared with cyclophosphamide, although exact corticosteroid doses before and after were unclear [78]. Pan et al. compared 11 patients with TAK with coronary ostial stenosis treated with tocilizumab with 11 others treated with conventional DMARDs. At 6 months, median reduction in ITAS2010 was 8 in tocilizumab group as opposed to 2 in patients treated with conventional DMARDs. Median prednisolone dose reduction following treatment in both groups was 66.7%. Median cumulative corticosteroid dose was lesser in tocilizumab-treated patients (1.65 g) when compared with those on conventional DMARDs (4.34 g), although the tocilizumab-treated patients had a much lower prednisolone dose at treatment onset (7.5 mg daily) when compared to the conventional DMARD arm (30 mg daily). Risk of adverse events was similar (risk ratio for tocilizumab versus conventional DMARDs 0.75, 95% CI 0.22–2.60) [90]. Mekinian et al. observed a greater risk of relapses with conventional DMARDs at 3 years compared with biological DMARDs (HR for relapse-free survival 0.26, 95% CI 0.09–0.73 for biologic versus conventional DMARDs). Patients on conventional DMARDs developed more vascular complications over 3 years (16.6%) when compared with biological DMARDs (5.1%)[55].

Adverse event profile of DMARDs

The proportions of adverse effects with individual drugs, where available, presented in Supplementary Fig. 2a have been discussed previously. A post hoc analysis looked at the frequency and profile of infectious adverse events. Proportions of patients developing infections with each drug in uncontrolled observational studies are presented in Supplementary Fig. 2b. The various infections encountered in different studies are summarized in Table 6. These were mainly respiratory, cutaneous and genitourinary infections, as well as reactivation of varicella zoster. The proportions of patients developing infectious adverse events with bDMARDs were numerically higher than those receiving cDMARDs.

Table 6.

Profile of infections with DMARDs in Takayasu arteritis

| Study* | Drug | Infections (number of episodes) |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||

| Langford 2017 (63) | Abatacept | URTI (2), sinusitis (2), otitis media (1), LRTI (2), cutaneous (1), pyelonephritis (1), vaginal candidiasis (2), UTI (2) |

| Nakaoka 2018 (72) | Tocilizumab | Infections (9) |

| Nakaoka 2020 (89) | Tocilizumab | Infections (32); serious infections (6): bacteremia (1), gastroenteritis (2), LRTI (2), pyelonephritis (1) |

| Controlled observational studies | ||

| Sun 2017 (67) | CYC | LRTI (3), UTI (1) |

| MTX | None | |

| Dai 2020 (83) | LEF | None |

| CYC | LRTI (3), fever (1) | |

| Wu 2020 (93) | LEF | LRTI (3), UTI (1) |

| MTX | LRTI (2), UTI (1) | |

| Ying 2020 (94) | LEF | LRTI (4), UTI (1) |

| CYC | LRTI (6), UTI (1), cutaneous (1) | |

| Kong 2018 (69) | Tocilizumab | None |

| CYC | None | |

| Pan 2020 (90) | Tocilizumab | None |

| cDMARDs | URTI (1) | |

| Uncontrolled observational studies | ||

| Shelhamer 1985 (32) | CYC | Cystitis (2), varicella zoster virus (1) |

| Hoffman 1994 (33) | MTX | Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia |

| Valsakumar 2003 (35) | AZA | None |

| Shinjo 2007 (39) | MMF | None |

| Goel 2010 (41) | MMF | Severe sepsis |

| de Souza 2012 (42) | LEF | None |

| Stern 2014 (53) | CYC | H1N1 influenza (1), cholecystitis (1), sinusitis (1), gastroenteritis (1), E. coli sepsis (1) |

| Li 2016 (58) | MMF | Hepatitis B virus reactivation (1) |

| Cui 2020 (82) | LEF | None |

| Li 2020 (86) | Tofacitinib | None |

| Nakagomi 2018 (71) | Rituximab | LRTI (1), invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (1) |

| Pazzola 2018 (75) | Rituximab | None |

| Hoffman 2004 (36) | TNFi | Histoplasmosis (1), varicella zoster virus (1) |

| Baldissera 2007 (37) | TNFi | None |

| Molloy 2008 (40) | TNFi | Viral infection (1), histoplasmosis (1) |

| Mekinian 2012 (43) | TNFi | Cutaneous (1), Epstein Barr virus (1), pulmonary tuberculosis (1) |

| Quartuccio 2012 (44) | TNFi | None |

| Schmidt 2012 (45) | TNFi | LRTI (3), varicella zoster virus (1), pyelonephritis (1), postoperative infection (1) |

| Tombetti 2013 (48) | TNFi | None |

| Serra 2014 (52) | TNFi | None |

| Youngstein 2014 (54) | TNFi | None |

| Kleinmann 2017 (62) | TNFi | None |

| Novikov 2018 (73) | TNFi | Herpes labialis (2), LRTI (1), tonsillitis (1), UTI (1), postoperative abscess (1) |

| Campochiaro 2020 (81) | TNFi | Varicella zoster virus (6), UTI (3), gastroenteritis (1) |

| Mertz 2020 (88) | TNFi | Pyelonephritis (2), otitis media (1) |

| Park 2018 (74) | TNFi | URTI (3), viral keratitis (1) |

| Erbasan 2020 (98) | TNFi, Tocilizumab | Serious infections (3), tubercular lymphadenitis (1) (in the entire cohort) |

| Goel 2013 (47) | Tocilizumab | UTI (1), URTI (1) |

| Tombetti 2013 (48) | Tocilizumab | Recurrent respiratory infections |

| Canas 2014 (50) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Loricera 2014 (51) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Novikov 2015 (56) | Tocilizumab | LRTI (3), varicella zoster virus (1) |

| Loricera 2016 (59) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Zhou 2017 (68) | Tocilizumab | UTI (1) |

| Mekinian 2018 (70) | Tocilizumab | Dental abscess (1) |

| Shah 2019 (77) | Tocilizumab | Postoperative infection (1) |

| Gon 2020 (84) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Kilic 2020 (85) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Mekinian 2020 (87) | Tocilizumab | URTI (3), viral gastroenteritis (2), UTI (1), varicella zoster virus (1) |

| Prieto-Pena 2020 (91) | Tocilizumab | LRTI (2), varicella zoster virus (1), abdominal sepsis (1) |

| Wang 2020 (92) | Tocilizumab | None |

| Isobe 2021 (95) | Tocilizumab | LRTI (1) |

*Studies which did not report infections are not mentioned here

AZA azathioprine, cDMARDs conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, CYC cyclophosphamide, LEF leflunomide, MTX methotrexate, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, TNFi tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors, LRTI lower respiratory tract infection, URTI upper respiratory tract infection, UTI urinary tract infection

Certainty of outcomes

Results are summarized in Table 7. The evidence for relapses, angiographic stabilization and reduction in prednisolone dose with tocilizumab, and for relapses and duration of remission for abatacept based on RCTs, were rated to be of moderate certainty due to some concerns about risk of bias for these studies (Table 3). For outcomes of reduction in Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score with curcumin and resveratrol, as well as for all outcomes derived from controlled or uncontrolled observational studies, the certainty of evidence was either low or very low, due to nature of studies (observational), risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, imprecision of estimates and inconsistency across studies.

Table 7.

Assessment of certainty of evidence using GRADE profiler

| Drug (reference number) | Outcomes evaluated (number of studies) | Certainty of evidence for outcome | Reason for downgrading certainty of evidence (if any) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | |||

| Tocilizumab (72) | Relapses (1) | Moderate | Serious RoB |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Moderate | Serious RoB | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–median (1) | Moderate | Serious RoB | |

| Abatacept (63) | Relapses (1) | Moderate | Serious RoB |

| Duration of remission (1) | Moderate | Serious RoB | |

| Resveratrol (66) | Reduction in BVAS (1) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious indirectness |

| Curcumin (65) | Reduction in BVAS (1) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious indirectness |

| Observational studies with control arms* | |||

| Cyclophosphamide versus methotrexate (60, 67) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| TNFi versus tocilizumab (55, 80) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious imprecision |

| bDMARDs versus cDMARDs (61, 69) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Low | - |

| Angiographic stabilization (2) | Low | - | |

| Uncontrolled observational studies* | |||

| Tocilizumab (46, 47, 49, 50, 51, 56, 59, 68, 70, 76, 77, 84, 85, 87, 91, 92, 95, 98) | At least partial clinical response (17) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency |

| Angiographic stabilization (12) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Normalization of inflammatory markers (5) | Very low | Very serious RoB | |

| Relapses (4) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Improvement on PET-CT (5) | Very low | Very serious RoB and inconsistency, serious imprecision | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (8) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–median (5) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| TNFi (36, 37, 40, 43, 44, 45, 48, 52, 54, 62, 73, 74, 79, 81, 88. 98) | At least partial clinical response (15) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency |

| Angiographic stabilization (10) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Normalization of inflammatory markers (2) | Very low | Very serious RoB | |

| Relapses (6) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Improvement in PET-CT (2) | Very low | Very serious RoB | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (3) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–median (8) | Very low | Very serious RoB, serious inconsistency | |

| Cyclophosphamide (32, 34, 53) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Methotrexate (33, 64) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious RoB |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Azathioprine (35, 64) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious RoB |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Cyclophosphamide + methotrexate (38) | At least partial clinical response (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Normalization of inflammatory markers (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Mycophenolate (39, 41, 58) | At least partial clinical response (3) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (3) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Leflunomide (42, 82, 99) | At least partial clinical response (3) | Very low | Serious RoB |

| Angiographic stabilization (2) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (2) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Cyclosporine (64) | At least partial clinical response (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Tacrolimus (64) | At least partial clinical response (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Rituximab (71, 75) | At least partial clinical response (2) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Relapses (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Improvement in PET-CT (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–median (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

| Tofacitinib (86) | At least partial clinical response (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision |

| Angiographic stabilization (1) | Very low | Serious RoB, serious imprecision | |

| Reduction in prednisolone dose–mean (1) | Very low | Serious RoB | |

*Evidence from all observational studies (controlled and uncontrolled) was downgraded for certainty of evidence due to study design

bDMARD biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, cDMARD conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, BVAS Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score, PET-CT positron emission tomography computerized tomography, RoB risk of bias, TNFi tumour necrosis factor inhibitors

DISCUSSION

The present systematic review overviews the evidence base for the management of TAK with DMARDs. There is a paucity of high-quality studies to guide the medical management of TAK. Only four distinct RCTs were identified, of which two had considerable methodological flaws. The use of conventional DMARDs in TAK is based only on observational studies. The lack of a suitable comparator group for observational studies in TAK was an important consideration downgrading the quality of evidence base.