We read with interest the case series published by Bonomo 1 presenting patients who were able to voluntarily suppress their chorea. Chorea consists of involuntary movements which are unpredictable but not generally thought to be suppressible or distractible. Interestingly, the reported patients could control their movements for a period of time on command.

As pointed out by the authors, the ability to suppress chorea has only rarely been studied. We would like to add to this discussion by presenting a patient with chorea‐acanthocytosis (CA) with remarkable improvement of chorea with distraction by motor tasks. This is a 40‐year‐old man with a five‐year history of generalized chorea and auto‐mutilation with lip biting. Associated findings include sensory neuropathy diagnosed by EMG, caudate atrophy on imaging, elevated creatine kinase, and more of 10% of acanthocytes on peripheral blood smear. He is the son of consanguineous parents. A diagnosis of chorea‐acanthocytosis was made. Over the course of the following years, he developed cognitive decline, obsessive–compulsive symptoms and worsening of motor skills with falls. Despite having severe chorea with frequent episodes of head drop and truncal extension, which have been recognized as hallmarks of the disease, 2 the patient's wife has noted that these movements consistently improve when he focuses on motor tasks, such as using a mobile (Video 1). He is, however, unable to voluntarily suppress these movements on command. Surface EMG ruled out dystonia or myoclonus as the cause of these movements (Fig. 1).

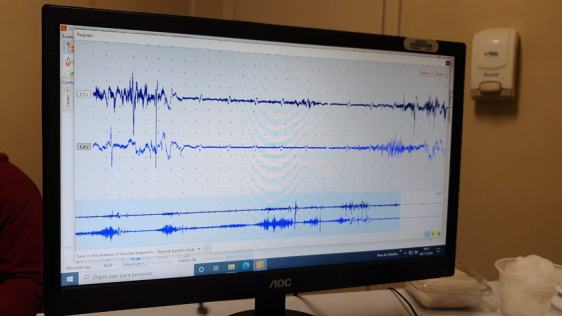

FIG. 1.

Surface electromyography recording in agonist/antagonist axial muscles shows intermittent EMG activity, sustained or in “bursts,” synchronic and assynchronic, with marked variation of amplitude, morphology and during distraction maneuver. In the register, ECG artifact can be also seen.

Video 1.

Video of patient showing generalized chorea and frequent episodes of head drop and truncal extension, all of which markedly improve when patient uses a mobile.

Typically, chorea does not improve with distractibility or with performance of motor tasks. Indeed, chorea tends to interfere with voluntary motor tasks, which contributes to the morbidity of chorea. In our patient, however, performing cognitive tasks that involve motor skills (such as unlocking a mobile) dramatically improved chorea. Chorea in CA has previously been reported to improve with voluntary motor activity, mental calculations and sensory tricks, as opposed to chorea in Huntington's disease. 3 , 4 We theorize that the performance of cognitive tasks or movement patterns requiring a certain degree of attention are capable, in this case, of diverting the basal ganglia cortical loop away from the pattern of increased corticomotor output proposed to be associated with chorea, and this ability could be useful as a form of “cognitive trick” for him to be able to temporarily suppress these abnormal movements.

Head drops and axial movements in CA are difficult to characterize phenomenologically due to their somewhat stereotypical and jerk‐like nature, but are generally considered to be a manifestation of chorea. In our patient, the analysis of burst duration, and the pattern of contraction of affected muscles were suggestive of chorea and not myoclonus or dystonia. Our patient does not report a premonitory urge, making the diagnosis of tic‐like movements unlikely.

This case adds to the knowledge of how chorea can not only be suppressed voluntarily, but also be distractible with motor tasks, two features typically seen as suggestive of a functional etiology. As discussed by the authors, we recommend caution before labeling chorea as functional in origin based solely on these features.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and critique.

R.M.: 1B, 3A

D.P.M.: 1C, 3B

F.C.: 1A, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work. The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: No specific funding was received for this work and the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Financial Disclosures for the Previous 12 Months: The authors declare that there are no additional disclosures to report.

References

- 1. Bonomo R, Latorre A, Balint B, et al. Voluntary inhibitory control of chorea: a case series. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020;7:308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schneider SA, Lang AE, Moro E, Bader B, Danek A, Bhatia KP. Characteristic head drops and axial extension in advanced chorea‐acanthocytosis. Mov Disord 2010;25:1487–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhidayasiri R, Jitkritsadakul O, Walker RH. Axial sensory tricks in chorea‐acanthocytosis: insights into phenomenology. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2017;7:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shibasaki H, Sakai T, Nishimura H, Sato Y, Goto I, Kuroiwa Y. Involuntary movements in chorea‐acanthocytosis: a comparison with Huntington's chorea. Ann Neurol 1982;12:311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]