Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also referred to as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), is a hypothesized neuroimmune illness with debilitating, heterogeneous symptoms that negatively impact daily functioning and quality of life, and often overrepresented among women (Broderick et al., 2012; Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2009; Smylie et al., 2013). Commonly experienced symptoms of CFS include severe fatigue, post-exertional malaise, sore throat, headache, memory and concentration difficulty, dizziness, sensory abnormalities, and significant sleep-related issues (Carruthers et al., 2011; Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue et al., 2015; Fukuda et al., 1994; Milrad et al., 2017).

A report issued by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) indicates that CFS affects approximately 836,000 to 2.5 million Americans (Bested & Marshall, 2015; Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue et al., 2015; Dimmock et al., 2016). The economic consequences of this illness are staggering; in the United States, the high rate of disability among people suffering from CFS accounts for 18–24 billion dollars per year of lost productivity and medical costs (Bested & Marshall, 2015; Dimmock et al., 2016). It is estimated that 30% of people with CFS and 51% of people suffering from CFS and a commonly comorbid, yet distinct diagnosis of fibromyalgia is unemployed in the US (Bombardier & Buchwald, 1996). The symptoms of the illness render patients more functionally impaired than those who suffer from other chronic illnesses such as congestive heart failure, multiple sclerosis, depression, and end-stage renal disease (Dimmock et al., 2016).

Not only does this chronic illness negatively affect the patient’s quality of life, but CFS may also drastically change the patient’s role in a number of domains: spousal and/or family, friendships, and within the workplace, as many people with CFS are unable to work at their premorbid level, if at all (Dimmock et al., 2016). CFS may add stress and adversity to the patient’s intimate relationships, especially in the context of partner caregiving burden due to disability and unemployment, which may precipitate or increase patient’s depressive symptoms (Verspaandonk et al., 2015). Relationship compatibility and how couples cope with the illness may contribute to depression and illness burden (Blazquez et al., 2012). The patient’s satisfaction related to the efforts of the couple (often in a patient-caregiver arrangement) to cope with an illness in response to the needs of the patient has not been formally conceptualized.

One major focus of the present study was to examine if relationship satisfaction, and/or couple-based coping strategies related to communicating support needs are associated with depressive symptoms and the experience of CFS symptoms. Though the research regarding couples’ satisfaction, depression and CFS symptoms, such as fatigue, is relatively scarce, the evidence generally mirrors that of other relevant work in chronic illnesses, in that marital discord and negative or solicitous (e.g. critical or patronizing comments and behavior) communication by the partner is detrimental to the CFS patient’s physical and mental well-being, including increased depression (Band et al., 2015; S.S. Goodwin, 1997; S.S. Goodwin, 2000; Romano et al., 2009).

CFS research typically involves women since they are two to four times more likely than men to be diagnosed with CFS (Klimas & Koneru, 2007). Women suffering from CFS reported more symptoms when they reported conflicts with their partners and relationship discord (S.S. Goodwin, 2000). In women with “chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome” (CFIDS), a condition synonymous with CFS, marital adjustment scores and husbands’ self-empathy scores were associated with less symptom severity, while the wives’ conflict scores were associated with greater symptom severity (S.S. Goodwin, 1997). While statistically controlling for demographic and marriage-related variables in the model, husbands’ and wives’ perceived marital support accounted for the most variance in CFIDS symptoms (S. S. Goodwin, 1997). Communication satisfaction, as wells as relationship satisfaction, may affect the patient’s experience with CFS and treatment outcomes.

There is a relative paucity of patient-caregiver communication-related research in the context of CFS, but a recent review of 14 studies details the associations between the responses of the significant other and CFS symptom outcomes (Band et al., 2015). CFS is a stigmatizing illness which is commonly misunderstood by both medical professionals and society in general (Looper & Kirmayer, 2004). Expectantly, people suffering from CFS tend to feel distressed when their partners do not understand their symptoms or validate the pain and distress caused by these symptoms (Band et al., 2015; Dickson et al., 2007). Furthermore, in one longitudinal study, negative interactions and perceived lack of social support predicted greater fatigue severity at 8-month follow-up (Prins et al., 2004). In that study, CFS and chronically fatigued (but not CFS diagnosed) patients received less social support and more negative interactions than breast cancer survivors and healthy controls (Prins et al., 2004). In sum, people with CFS are affected not only by their symptoms, but by their own emotional and behavioral response to their symptoms, and by the responses of their partner and others in their social circle (Band et al., 2015; Dempster et al., 2011).

The present study expands this line of work by examining how relationship satisfaction among CFS patients and their caregiving partner can impact the CFS patient’s experience of the illness, including their psychological and physical well-being. Specifically, this study investigated the associations among patient reports of relationship satisfaction and CFS-related fatigue severity, while also testing couples’ coping and communication about symptoms and patients’ depressive symptom severity as intermediary variables. The study uses structural equation modeling to test the hypothesis that a) greater relationship satisfaction is associated with less depressive symptoms, greater communication satisfaction, and less CFS-related fatigue in CFS patients, and b) there is an indirect effect of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity through communication satisfaction and/or depression.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants in this study were recruited for a trial of the biopsychosocial effects of a stress management intervention for CFS patients and their partners. All participants received a physician-determined CFS diagnosis, as defined by the CDC criteria (Fukuda et al., 1994). Recruitment methods included physician referral, support groups, CFS conferences, and advertisements in CFS-related websites. The CFS sample was selected from the patient population of the Center for the Study of CFS Pathogenesis at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (UMMSOM), and the Chronic Fatigue Center for Research and Treatment for Neuroimmune Disorders at Nova Southeastern University; the chronic pain, CFS, and fibromyalgia clinic within UMMSOM; community based physicians in Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach Counties; and via community support groups, newspaper and web advertisements, and CFS-related internet sites. All study procedures were approved by University of Miami’s Institutional Review Board (IRB # 20100771). This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS R01NS072599) and registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01650636).

Participants.

A total of 759 potential subjects were referred and screened, 166 were deemed eligible and enrolled, 16 subsequently withdrew from the study, and a total of 150 patient-partner dyads (N = 300) between the age of 21 and 75 years were recruited into the study during the period July 2010 –September 2016. The sample reflects the sociodemographic profile of CFS patients in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties.

Inclusion criteria.

A documented diagnosis of CFS as designated by the Fukuda criteria (Fukuda et al., 1994) was the main criterion for participation. This included experiencing prolonged, persistent fatigue for at least six consecutive months that is not explained by another medical condition, in addition to at least four of the following concurrent symptoms: impaired memory or concentration, sore throat, tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes, muscle pain, multi-joint pain, new headaches, unrefreshing sleep, and post-exertional malaise. All participants were also required to be fluent in English, partnered (living together or separately), and willing to complete the study protocol.

Exclusion criteria.

Potential patient participants were excluded for the following reasons: less than 21-years or more than 75-years old, history of significant inability to keep scheduled clinic appointments, or positive serology for Lyme’s disease. During screening, all patients were assessed for psychiatric diagnosis at the time of recruitment with a detailed screening questionnaire including selected Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-IV) modules. Based on this assessment, we excluded patients with DSM-IV diagnoses for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, or if they were actively suicidal, as assessed by a brief screening measure adapted from the SCID-IV (First et al., 1997). Participants were also excluded if they showed markedly diminished cognitive capabilities, as evidenced by making four or more errors on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer, 1975) or a score of less than 20 points on the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) (Brandt et al., 1988). Presence of another condition (e.g., AIDS, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)) that might influence biological processes associated with CFS symptomatology or taking medications that would modulate immune or neuroendocrine functioning excluded patient participants from the study.

Procedures.

Participants in this study were recruited for a trial of the biopsychosocial effects of a remotely delivered stress management intervention (CBSM) for CFS patients and their partners, compared to an attention-matched health promotion control intervention. Upon enrollment, participants signed an informed consent and completed a baseline assessment battery consisting of questionnaires as well as blood and saliva collection prior to the intervention, at 5 months post-baseline (after the intervention was completed), and at 9 months post-baseline. Only CFS patients were asked to provide saliva and blood samples. CFS patients and their caregiving partners completed the surveys independently. To ease the burden of commuting, all participants were assessed wherever was most convenient for them (in-person or on the phone); electronic surveys were emailed to them via a secure, online survey platform called SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., California, USA) and could be completed on their tablet or computer. After completing surveys participants were compensated $50 for their time.

Measures

Psychosocial Functioning.

Patients completed measures of stress, depression, relationship quality, coping, social disruption, and social support using an online link to a questionnaire. Although partners completed other forms, for the present study, only patient data was used in analyses. Means and standard deviations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics on Model Variables (N=150)

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| DAS Total | 110.61 | 21.35 |

| CES-D | 22.12 | 11.17 |

| PSDS | 204.73 | 76.72 |

| Fatigue Severity | 6.13 | 1.93 |

DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

PSDS = Patient Symptom Disclosure Satisfaction

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS).

The 32-item DAS (Spanier, 1976) was used to assess a global measure of relationship satisfaction. Sample items include: “For each item on the following list, please indicate the approximate extent of agreement or disagreement between you and your partner… How often do you confide in your partner? How often would you say the following events occur between you and your mate?” Global scores range from 0–151; a higher score indicates higher relationship functioning. The DAS Total score is reliable in our sample (α=0.924).

Patient Symptom Disclosure Satisfaction (PSDS).

Communication satisfaction was measured by the Patient Pain Communication Self-Efficacy measure, which was adapted to this patient population from other communication efficacy scales (Lorig et al., 1989; Porter et al., 2008). Patients rate their ability to communicate their symptoms to their partner using a scale from 10 (very uncertain) to 100 (very certain). Patients are asked “1. How certain are you that you can let your partner know how much your ME/CFS symptoms are bothering you? 2. How certain are you that your partner understands how much your ME/CFS symptoms bother you? 3. How certain are you that your partner will respond to your ME/CFS symptoms in a way that meets your needs?” In our sample, the subscale is reliable (α=0.875).

Fatigue Symptom Inventory (FSI).

The 4-item fatigue intensity subscale of the FSI assessed fatigue intensity (Hann et al., 1998). Items from the subscale were rated on an 11-point scale. Here 0 indicated feeling “not at all fatigued” and 10 indicated feeling “as fatigued as I could be” for the following 4 fatigue intensity items. Items include: “1. Rate your level of fatigue on the day you felt most fatigued during the past week. 2. Rate your level of fatigue on the day you felt least fatigued during the past week. 3. Rate your level of fatigue on the average in the last week. 4. Rate your level of fatigue right now.” The FSI is reliable in our sample (α=0.894 for fatigue intensity). Fatigue intensity was renamed “fatigue severity” for this manuscript.

Center for Epidemiologic Survey Depression Scale (CES-D).

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item measure that assesses depressive symptomatology over the past week. Participants were asked questions such as “I felt sad” and responded on a 4-point scale ranging from “Rarely or none of the time (<1 day)” to “Most or All of the Time (5–7 days).” A score of 16 or above indicates clinically significant depressive symptoms. The measure is reliable in the current sample (α = 0.70) and has been shown to be a valid and reliable indicator of depressive symptoms in medical populations (Antoni et al., 2001).

Descriptive and Control Measures

Demographic variables such as age, race, ethnicity, Hollingshead index for socioeconomic status (SES), education, employment status, current living situation, and relationship status were assessed at study entry. Age and body mass index (BMI) were used as theoretically derived covariates in the final models, as they are shown to contribute to the variability in psychosocial, neuroendocrine, and immunological measurements (O’Connor et al., 2009). Preliminary descriptive analysis of our baseline sample shows that most of the sample has completed some or all of college; therefore, “education” was not included as a covariate in these analyses. Similarly, “gender” was not used as a covariate, as most of the sample are women (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample (N=150)

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 19 | 12.7 |

| Female | 131 | 87.3 |

| Ethnic Identification | ||

| Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 98 | 65.3 |

| Black/African American | 2 | 1.3 |

| Caribbean Islander | 3 | 2.0 |

| Hispanic | 45 | 30.0 |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 | 0.7 |

| Other | 1 | 0.7 |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | |

| Age in years | 48.0 | 10.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 | 6.8 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-Time | 32 | 21.3 |

| Part-Time | 16 | 10.7 |

| Student | 5 | 3.3 |

| On Disability | 38 | 25.3 |

| Retired | 8 | 5.3 |

| Unemployed | 27 | 18.0 |

| Volunteer Worker | 2 | 1.3 |

| Other | 20 | 12.7 |

| Education Level | ||

| Some high school | 3 | 2.0 |

| High school graduate | 5 | 3.3 |

| GED | 4 | 2.7 |

| Trade school | 6 | 4.0 |

| Some college | 36 | 24.0 |

| College graduate | 55 | 36.7 |

| Graduate degree | 39 | 26.0 |

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics were computed for every variable to ensure that all values were within expected ranges and to identify and eliminate any data entry or collection errors that may have occurred.

Missing Data.

The data collected from the 150 patients were used for the present study. Across measures, 4.8% of data were missing (range across measures = 0% to 16.0%). Little’s test for data that is Missing Not Completely at Random (MCAR) was not significant (p = 0.88), indicating that the data was MCAR. Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) was employed within Mplus Software Version 8 (Muthen and Muthen, Los Angeles, CA) to generate maximum likelihood estimates of simultaneous equations for use in structural equation modeling (Markus, 2012; Wothke, 2000).

Estimates of Direct and Indirect Effects.

Direct and indirect effects were estimated simultaneously using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus (Markus, 2012), using age and BMI as covariates. Bootstrapping (10,000 iterations) was used to estimate the effects (Hayes, 2009, 2017). Model fit indices were compared against Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08, and Chi-square tests at α = 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Parallel Mediation Models.

Parallel mediation modeling (Hayes, 2017) was performed using hypothesized, concomitant intermediary variables, patient symptom disclosure satisfaction (PSDS), and depression. Parallel mediator modeling increases the power available to detect indirect effects and provides the ability to compare the sizes of the indirect effects (e.g. through communication satisfaction vs. depression) on the outcome of interest (Hayes, 2017). Therefore, this method provides additional information about the potential mechanism(s) that underlie variance in CFS-related fatigue.

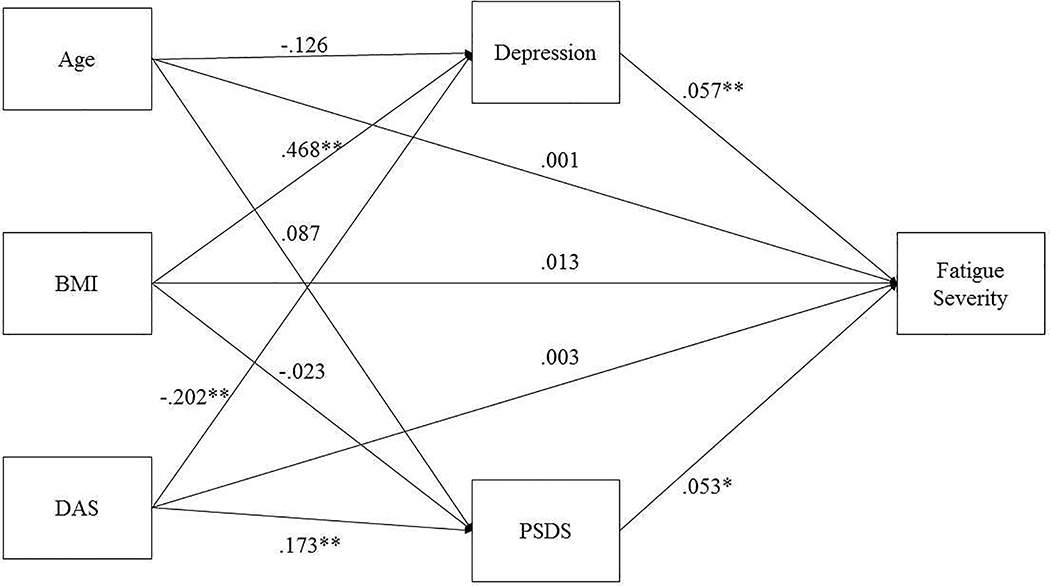

The model investigated the effects of relationship satisfaction (Dyadic Adjustment Scale-DAS Total Score), patient symptom disclosure satisfaction (PSDS-communication satisfaction), and depressive symptoms on fatigue (Figure 1). Age and BMI were entered as covariates for all analyses since they significantly predict variance associated with depression in both men and women (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2015; O’Connor et al., 2009). Power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that regression analysis using 150 subjects, with one predictor and three covariates afforded power of at least 0.92 to detect a small to medium effect size (f2 > 0.10). To analyze indirect effects (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes, 2017), 150 subjects was sufficient to detect a combined (a*b) small to medium effect of f2 > 0.05 (power = 0.84, using one direct predictor, two indirect predictors, and two covariates). The alpha was set at p < 0.05 to minimize the risk for Type 1 error.

Fig. 1.

Structural Equation Model of Direct and Indirect Effects on Fatigue Severity in CFS Patients. Unstandardized estimates are shown with their respective path arrows.

*p<.05; **p<.01.

Results

Sample Description

The sample for this study was 150 patients with CFS, with a mean age of 48.0 years (SD = 10.9), as shown in Table 1. The sample was predominately non-Hispanic White (65.3%) and highly educated (62% were enrolled in college or received a college or graduate degree). As shown in Table 2, mean fatigue severity scores (M = 6.13) were indicative of clinically significant fatigue (scores ≥ 3) (Donovan et al.) and the sum total fatigue severity score in our sample (M = 24.53) was comparable to that of another CFS sample (M = 26.74) (Lattie et al., 2012). For reference, the present study sample’s mean fatigue severity scores were higher than that of breast cancer patients undergoing primary treatment (M = 3.4), and age and gender-matched healthy controls (M = 2.8) (Hann et al., 1998). Depressive symptom severity scores on the CES-D (M = 22.13) were above the clinical cut-off of 16 (Radloff, 1977), and were comparable to another CFS patient population (M = 25.37) reported elsewhere (Lattie et al., 2012).

Main Analyses

Models were tested using SEM to determine the total, direct and indirect effects of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity. First, the effect of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity was tested without the intermediate variables in the model. Controlling for age and BMI, the association between relationship satisfaction and fatigue severity was not significant (b < −0.01, se < 0.01, p = 0.72). Covariates age and BMI also did not significantly relate to fatigue severity. The model fit the data and was just identified (RMSEA= 0.00, CFI= 0.00, TLI=1.00, SRMR= 0.00, χ2(0) = 0.00, p = 0.99).

Next, a parallel multiple mediator model was examined to test direct and indirect associations between variables. Specifically, the direct effect of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity and the indirect effects of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity, by way of depression and communication satisfaction, were examined simultaneously (Figure 1). The model fit the data moderately well (RMSEA = 0.09, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02, χ2(1) = 2.19, p = 0.14) and the direct effect of relationship satisfaction remained non-significant when the intermediary variables were added to the model (b < 0.01, se = 0.01, p = 0.74). As depicted in Figure 1, relationship satisfaction and BMI related to (M1) depression, while only relationship satisfaction significantly related to (M2) communication satisfaction. Both depression and communication satisfaction significantly related to fatigue severity, even with age, and BMI included in the model (Table 3, Figure 1). Results are summarized in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Direct Effects of Relationship Satisfaction, Parallel Mediators and Covariates on Fatigue Severity (N=150).

| Depression (Mediator1) | PSDS (Mediator2) | Fatigue Severity (Outcome) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| DAS Total | −.20 | .05 | <.01 | .17 | .03 | <.01 | <.01 | .01 | .74 |

| Depression | .06 | .02 | <.01 | ||||||

| PSDS | .05 | .03 | .03 | ||||||

| Age | −.13 | .08 | .10 | .09 | .05 | .06 | <.01 | .01 | .92 |

| BMI | .47 | .14 | <.01 | −.02 | .09 | .79 | .01 | .03 | .61 |

| Constant | 37.57 | 6.55 | <.01 | −2.07 | 4.46 | .64 | 2.99 | 1.23 | .02 |

Unstandardized estimates are shown.

DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale

PSDS = Patient Symptom Disclosure Satisfaction

BMI = Body Mass Index (kg/m2)

Finally, tests of the indirect effects revealed several patterns (see Figure 1). There was a significant direct effect of relationship satisfaction on depression, and a significant direct effect of depression on fatigue severity (Table 3, Figure 1), resulting in a significant indirect effect of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity through depression (a1b1 = −0.01, se = 0.01, p = 0.02). Turning to communication satisfaction, there was a significant direct effect of relationship satisfaction on communication satisfaction, and a significant direct effect of communication satisfaction on fatigue severity (Table 3, Figure 1), resulting in a non-significant indirect effect of relationship satisfaction on fatigue severity through communication satisfaction (a2b2 = 0.01, se = 0.01, p = 0.06). Post-hoc analyses including gender, ethnicity, and education as additional covariates did not significantly change the conclusive relationships evident in the model discussed here (Figure 1).

Discussion

As hypothesized, the results of the present study indicate that relationship satisfaction and the responses of the partner to patient symptoms can affect the patient’s experience of CFS symptoms and its treatment (Romano et al., 2009; Schmaling et al., 2017; Schmaling et al., 2000; Verspaandonk et al., 2015). Patients and their partners may jointly cope with the illness or instead might experience incongruency about the interpretation of symptoms and their consequent management, which may affect the perceived and/or actual support given by partners and by a larger support network (Band et al., 2015; Brooks et al., 2014; Dickson et al., 2007). The present study tested the associations of relationship satisfaction, depression, and patient symptom disclosure satisfaction (communication satisfaction) on fatigue severity in patients with CFS. Depression and communication satisfaction were examined as intermediary variables of the hypothesized effects of relationship satisfaction on CFS-related fatigue (Table 3, Figure 1). Relationship satisfaction, as measured by the composite DAS score, showed no direct effects on fatigue severity (Table 3, Figure 1). Relationship satisfaction, did however, relate to less depression and greater communication satisfaction (Table 3, Figure 1), as hypothesized based upon prior work (S.S. Goodwin, 1997; S.S. Goodwin, 2000; Romano et al., 2009). With regards to the intermediary variables, both communication satisfaction and depression related to greater fatigue severity (Table 3, Figure 1).

However, when the intermediary variables were added to the model, relationship satisfaction was related to fatigue severity, by way of depression primarily, and communication satisfaction secondarily (Table 3, Figure 1). These results confirmed the hypothesis that the proposed intermediary variables (depression and communication satisfaction) were significantly associated with both relationship satisfaction and fatigue severity, which underscores the importance of considering these factors in research and treatment development aimed at benefitting CFS patients and possibly their caregiving partners jointly coping with CFS.

Importantly, the hypothesis that greater relationship satisfaction would be significantly associated with decreased fatigue severity was based on extant research of pain patients and their caregiving partners, given the relative lack of research available for CFS patients and their partners. In contrast to the relative paucity of literature examining the effects of relationship satisfaction in CFS, much of the extant literature focused on the effects of depression and the type of communication style that a caregiving partner used (Band et al., 2015) (e.g. solicitous, distracting). Like the research exploring partners’ responses to pain communication, solicitous partner responses were associated with increased fatigue severity and bodily pain in CFS (Schmaling et al., 2000). Interestingly, distracting and punishing partner responses were not significantly associated with fatigue, pain, disability, or physical functioning (Schmaling et al., 2000). In a hierarchical modeling analysis of dyads coping with CFS and/or FM, or idiopathic chronic fatigue (ICF), more solicitous partner responses covaried with more tender points; also, more negative partner responses covaried with more bodily pain, more CFS symptom severity, worse physical functioning, and worse mental health over time (Schmaling et al., 2017). Additionally, more distracting partner responses covaried with better mental health functioning over the same time period of 18 months (Schmaling et al., 2017).

Importantly, the study participants did not meet full criteria for CFS (ICF), and both CFS and FM are hypothesized to have distinct symptoms and heterogeneous patient populations. Therefore, these prior results may not be fully generalizable to a “pure” CFS sample, or possibly only to certain subtypes of CFS. While these analyses were preliminary, the results provide support that solicitous partner responses may act as a perpetuating factor in CFS, as was suggested for pain behavior and partner solicitous responses (Schmaling et al., 2000). The type of communication (e.g. distraction, solicitous) was not analyzed as part of the present study; however, the patient’s subjective appraisal of the quality of their interactions surrounding discussion of CFS symptoms is studied here (e.g. communication satisfaction). Extant research within the topic of CFS patients and their caregiving partners also did not use FSI-derived fatigue severity as an outcome measure, nor was the DAS total score used to quantify relationship satisfaction as a construct (Band et al., 2015). Therefore, the documented associations among interpersonal variables examined here were novel and filled a gap in the CFS literature.

Depression and CFS symptoms (including fatigue) are positively related in many patient populations, including CFS patients (Janssens et al., 2015); therefore, the finding that depression related to greater fatigue severity was in line with the extant literature (Table 3, Figure 1). However, it is interesting to note that communication satisfaction (as well as depression) was related to greater fatigue severity, even when depression was included in the model (Table 3, Figure 1).

Depression could be a confounder in this analysis, as depression could have led to lower relationship satisfaction and more CFS-related fatigue. This study specifically wanted to develop the basis for a nuanced model based off the Marital Discord Model of Depression, which supports that marital discord is an antecedent in the development of a depressive episode, especially in those who are chronically dysphoric, and this effect generalizes across different sample factors including ethnicity (Beach & O’Leary, 1993; Beach et al., 1990; Hollist et al., 2007). The effect is bi-directional, as baseline depressive symptoms can predict marital discord at follow-up (Whisman & Uebelacker, 2009). Using the study variables in the context of CFS is relatively novel; additional time-lagged studies are warranted to further clarify the role of depression in the experience of couples coping with CFS.

The observed relationship between greater communication satisfaction and greater fatigue severity was incongruent with one longitudinal study which showed that perceived negative interactions and decreased social support among dyads predicted greater fatigue severity in patients diagnosed with CFS and chronic fatigue (Prins et al., 2004). Importantly, Prins et al. did not measure perceived satisfaction about couples’ communications about symptoms, but instead used a more global measure encompassing six types of social support.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study was that the patients’ perceived type of partner response (i.e. solicitous versus supportive) and fatigue-related disability were not assessed. Extant literature showed that relationship satisfaction moderated the positive relation between partners’ solicitous responses and fatigue-related disability, and fatigue severity in the context of CFS, such that the effect was stronger for those dyads with the highest level (low, average, high) of relationship satisfaction (Schmaling et al., 2000). It is possible that solicitous responses may be perceived as positive by the patient and reflected in a higher communication satisfaction score, thereby contributing to the current findings. The present study was similarly cross-sectional, therefore causative claims cannot be made, especially the implication that partner responses perpetuate fatigue severity or fatigue-related disability (operant theory) in CFS (Romano et al., 2009; Schmaling et al., 2000).

Conclusions

The present study’s results, in combination with extant literature findings, suggested that the relationship between greater communication satisfaction and greater fatigue may reflect the fact that partners were being (appropriately) attentive to patients with CFS. This was particularly evident when patients reported having greater somatic symptom severity (e.g. fatigue). Possibly, greater fatigue severity encourages the couple to adapt and grow stronger together, by increasing their communication and support, as shown anecdotally in one semi-qualitative pilot study of couples coping with CFS/ME (Lingard & Court, 2014). Partners reported greater appreciation for their significant other, increased spirituality (within Christianity), greater couple resilience, and increased fondness and admiration for one another compared to life before caring for a CFS partner (Lingard & Court, 2014). Additionally, the couples expressed that coping with CFS/ME has helped them reappraise their relationship, discover new strengths in their relationship, enhance proactivity in addressing CFS/ME related concerns, self-improve, improve relationships with other people, and greater capacity for sensitivity to the emotions of himself or herself, and his or her partner (Lingard & Court, 2014). We also acknowledge that this study’s sample reported high relationship satisfaction and symptom disclosure satisfaction (Table 2). Therefore, future testing with samples reporting poorer relationship satisfaction is warranted. Additionally, analyses should further confirm the bi-directional relationship between CFS-related fatigue and relationship satisfaction, using CFS-related fatigue as the predictor.

Finally, future research should examine whether relationship satisfaction might moderate effects of psychosocial interventions on CFS-related outcomes. Currently, our group is conducting a follow-up analyses of the intermediary variables (i.e., using parallel mediator modeling with moderation). Future longitudinal work should allow for time-lagged mediation analyses that would inform mechanism of change research, including an analysis of health behaviors, which are sensitive to marital dysfunction (Roberson et al. 2018). Ensuing analyses of the importance of communication satisfaction in couples coping with CFS would potentially also benefit from adding an examination of communication styles that were previously shown to be significant in CFS literature among couples (Band et al., 2015; Schmaling et al., 2017; Schmaling et al., 2000). This would hone in on adaptive or maladaptive communication variables that may be targeted in the therapeutic realm, as well as inform stress and depressive-related perpetuating mechanisms of CFS symptomology. The therapeutic implications of these preliminary results highlight the importance of developing interventions that utilize and support greater communication satisfaction among couples, while also decreasing depression and fatigue in CFS patients, and theoretically, lower caregiving burden.

Highlights.

Relationship satisfaction and depression can impact CFS-related fatigue.

Patient symptom disclosure satisfaction (PSDS) is a hypothesized intermediate.

Depression and PSDS were examined as intermediary variables of this relationship.

Relationship satisfaction was related to fatigue severity via depression and PSDS.

This underscores the importance of considering these factors in the context of CFS.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS R01NS072599) and registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01650636).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, et al. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol, 20, 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band R, Wearden A, & Barrowclough C (2015). Patient Outcomes in Association With Significant Other Responses to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clinical Psychology, 22, 29–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, & O’Leary KD (1993). Marital discord and dysphoria: For whom does the marital relationship predict depressive symptomatology? J. Soc. Pers. Relat, 10, 405–420. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Sandeen E, & O’Leary KD (1990). Depression in marriage: A model for etiology and treatment: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bested AC, & Marshall LM (2015). Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev. Environ. Health, 30, 223–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez A, Guillamo E, Alegre J, Ruiz E, & Javierre C (2012). Psycho-physiological impact on women with chronic fatigue syndrome in the context of their couple relationship. Psychol. Health Med, 17, 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardier CH, & Buchwald D (1996). Chronic fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia: disability and health-care use. Medical Care, 34, 924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Spencer M, & Folstein M (1988). The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. Behav. Neurol, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick G, Katz BZ, Fernandes H, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Smith FA, et al. (2012). Cytokine expression profiles of immune imbalance in post-mononucleosis chronic fatigue. J. Transl. Med, 10, 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks J, King N, & Wearden A (2014). Couples’ experiences of interacting with outside others in chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative study. Chronic Illness, 10, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, et al. (2011). Myalgic encephalomyelitis: international consensus criteria. J. Int. Med, 270, 327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue, S., Board on the Health of Select, P., & Institute of, M. (2015). The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). Copyright 2015 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster M, McCorry NK, Brennan E, Donnelly M, Murray LJ, & Johnston BT (2011). Do changes in illness perceptions predict changes in psychological distress among oesophageal cancer survivors? J. Health Psychol, 16, 500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson A, Knussen C, & Flowers P (2007). Stigma and the delegitimation experience: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of people living with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychology and Health, 22, 851–867. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock ME, Mirin AA, Jason LA (2016) Estimating the disease burden of ME/CFS in the United States and its relation to research funding. J. Med. Therap 1: DOI: 10.15761/JMT.1000102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB, Small BJ, Munster PN, & Andrykowski MA Identifying Clinically Meaningful Fatigue with the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. J. Pain Symptom Manag, 36, 480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, & Buchner A (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods, 39, 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, & Spitzer RL (1997). User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders: SCID-II: American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DB, William AH, Strauss AC, Unger ER, Jason L, Marshall GD Jr., et al. (2014). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Current Status and Future Potentials of Emerging Biomarkers. Fatigue, 2, 93–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher MA, Zeng XR, Barnes Z, Levis S, & Klimas NG (2009). Plasma cytokines in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Transl Med, 7, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, & Komaroff A (1994). The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann. Int. Med, 121, 953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SS (1997). The marital relationship and health in women with chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome: views of wives and husbands. Nurs Res, 46, 138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SS (2000). Couples’ perceptions of wives’cfs symptoms, symptom change, and impact on the marital relationship. Issues in mental health nursing, 21, 347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, Martin SC, Curran SL, Fields KK, et al. (1998). Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual. Life Res, 7, 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hollist CS, Miller RB, Falceto OG, & Fernandes CLC (2007). Marital satisfaction and depression: A replication of the marital discord model in a Latino sample. Fam. Process, 46, 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens KA, Zijlema WL, Joustra ML, & Rosmalen JG (2015). Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Results From the LifeLines Cohort Study. Psychosom. Med, 77, 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, & Fagundes CP (2015). Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am. J. Psychiatry, 172, 1075–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimas NG, & Koneru AO (2007). Chronic fatigue syndrome: inflammation, immune function, and neuroendocrine interactions. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep, 9, 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattie EG, Antoni MH, Fletcher MA, Penedo F, Czaja S, Lopez C, et al. (2012). Stress management skills, neuroimmune processes and fatigue levels in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain. Behav. Immun, 26, 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingard RJ, & Court J (2014). Can Couples Find a Silver Lining Amid the Dark Cloud of ME/CFS: A Pilot Study. Fam. J, 22, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Looper KJ, & Kirmayer LJ (2004). Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J. Psychosom. Res, 57, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, & Holman HR (1989). Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol, 32, 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus KA (2012). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling by Rex B. Kline. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Milrad SF, Hall DL, Jutagir DR, Lattie EG, Ironson GH, Wohlgemuth W, et al. (2017). Poor sleep quality is associated with greater circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and severity and frequency of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) symptoms in women. J. Neuroimmunol, 303, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M-F, Bower JE, Cho HJ, Creswell JD, Dimitrov S, Hamby ME, et al. (2009). To assess, to control, to exclude: effects of biobehavioral factors on circulating inflammatory markers. Brain. Behav. Immun, 23, 887–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E (1975). A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc., 23, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Wellington C, & de Williams A (2008). Pain communication in the context of osteoarthritis: patient and partner self-efficacy for pain communication and holding back from discussion of pain and arthritis-related concerns. Clin. J. Pain, 24, 662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins JB, Bos E, Huibers M, Servaes P, Van Der Werf S, Van Der Meer J, et al. (2004). Social support and the persistence of complaints in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychother. Psychosom, 73, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson PN, Shorter RL, Woods S, & Priest J (2018). How health behaviors link romantic relationship dysfunction and physical health across 20 years for middle-aged and older adults. Soc. Sci. Med, 201, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano JM, Jensen MP, Schmaling KB, Hops H, & Buchwald DS (2009). Illness behaviors in patients with unexplained chronic fatigue are associated with significant other responses. J. Behav. Med, 32, 558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaling KB, Fales JL, & McPherson S (2017). Longitudinal outcomes associated with significant other responses to chronic fatigue and pain. J. Health Psychol, 1359105317731824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaling KB, Smith WR, & Buchwald DS (2000). Significant other responses are associated with fatigue and functional status among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom. Med, 62, 444–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smylie AL, Broderick G, Fernandes H, Razdan S, Barnes Z, Collado F, et al. (2013). A comparison of sex-specific immune signatures in Gulf War illness and chronic fatigue syndrome. BMC Immunol, 14, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J. Marriage Fam, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Verspaandonk J, Coenders M, Bleijenberg G, Lobbestael J, & Knoop H (2015). The role of the partner and relationship satisfaction on treatment outcome in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol. Med, 45, 2345–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, & Uebelacker LA (2009). Prospective associations between marital discord and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging, 24, 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W (2000). Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. pp. 219–240, 269–281). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]