Previous reports have speculated on the effect of polyamines on bacterial biofilm formation. However, the regulation of biofilm formation by polyamines in Escherichia coli has not yet been assessed.

KEYWORDS: glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase, spermidine N-acetyltransferase, spermidine synthase, polyamine

ABSTRACT

Polyamines are essential for biofilm formation in Escherichia coli, but it is still unclear which polyamines are primarily responsible for this phenomenon. To address this issue, we constructed a series of E. coli K-12 strains with mutations in genes required for the synthesis and metabolism of polyamines. Disruption of the spermidine synthase gene (speE) caused a severe defect in biofilm formation. This defect was rescued by the addition of spermidine to the medium but not by putrescine or cadaverine. A multidrug/spermidine efflux pump membrane subunit (MdtJ)-deficient strain was anticipated to accumulate more spermidine and result in enhanced biofilm formation compared to the MdtJ+ strain. However, the mdtJ mutation did not affect intracellular spermidine or biofilm concentrations. E. coli has the spermidine acetyltransferase (SpeG) and glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase (Gss) to metabolize intracellular spermidine. Under biofilm-forming conditions, not Gss but SpeG plays a major role in decreasing the too-high intracellular spermidine concentrations. Additionally, PotFGHI can function as a compensatory importer of spermidine when PotABCD is absent under biofilm-forming conditions. Last, we report here that, in addition to intracellular spermidine, the periplasmic binding protein (PotD) of the spermidine preferential ABC transporter is essential for stimulating biofilm formation.

IMPORTANCE Previous reports have speculated on the effect of polyamines on bacterial biofilm formation. However, the regulation of biofilm formation by polyamines in Escherichia coli has not yet been assessed. The identification of polyamines that stimulate biofilm formation is important for developing novel therapies for biofilm-forming pathogens. This study sheds light on biofilm regulation in E. coli. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that only spermidine can stimulate biofilm formation in E. coli cells, not putrescine or cadaverine. Last, ΔpotD inhibits biofilm formation even though the spermidine is synthesized inside the cells from putrescine. Since PotD is significant for biofilm formation and there is no ortholog of the PotABCD transporter in humans, PotD could be a target for the development of biofilm inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria have self-defense mechanisms to survive in various environments. Most bacteria, especially pathogenic species, can switch from planktonic growth to a biofilm life cycle as a survival strategy when faced with environmental stress (1, 2). Biofilms are communities of bacteria and/or other microorganism assemblages within an extracellular matrix comprising polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular nucleic acids, and lipids (3, 4), which function as a shield to protect the cells within the biofilm (5). Biofilms are generated in response to specific environmental stimuli and can be formed on both biotic and abiotic surfaces (6). In comparison to free-living bacterial cells, bacteria in biofilms have lower proliferation and metabolism rates and higher antibiotic resistance (7, 8). Furthermore, biofilms of pathogenic microorganisms are generally more resistant to host immune responses (9, 10). As a result, diseases caused by pathogens forming biofilms are difficult to cure (11–13).

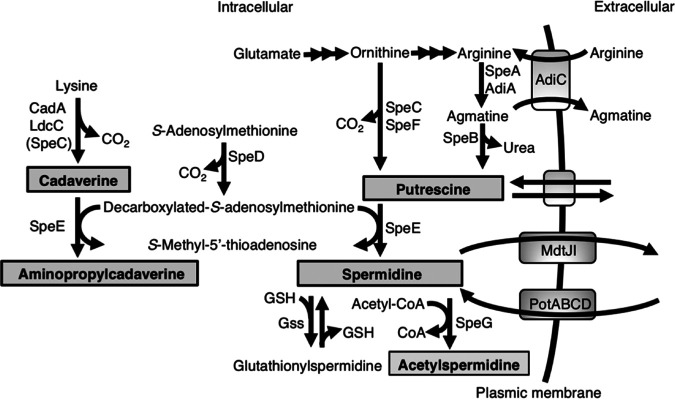

Polyamines are polycationic molecules whose hydrocarbon structures contain at least two primary amino groups (14). They are produced by many prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and archaeal organisms (15–17). Polyamines participate in cell proliferation, growth, and differentiation by exerting effects on the translation process (18–21). Therefore, higher concentrations of polyamines have been detected in rapidly proliferating cells such as stem cells and cancer cells (22, 23). Cadaverine, putrescine, and spermidine exist in many bacterial cells. In Escherichia coli, putrescine generated from ornithine or arginine can be converted to spermidine, while cadaverine is synthesized from lysine (Fig. 1). However, a high concentration of spermidine is toxic to cells (24, 25). Therefore, bacteria have mechanisms to decrease the amount of spermidine.

FIG 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of polyamines in E. coli K-12. Putrescine is synthesized through two pathways: generated from ornithine by ornithine decarboxylase (SpeC and SpeF) or from arginine by the sequential reactions of arginine decarboxylase (SpeA and AdiA) and agmatinase (SpeB). Since SpeB is the only agmatinase in E. coli, ΔspeB strains cannot make putrescine even when AdiA is present. Both SpeF and AdiA are activated only at low pH. In fact, we did not observe agmatine accumulation in the cells in this study. Spermidine is synthesized from putrescine through a SpeD-SpeE-dependent mechanism, and cadaverine is synthesized from lysine by lysine decarboxylase (CadA and LdcC) or SpeC. Spermidine acetyltransferase (SpeG) and glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase (Gss) convert spermidine to acetylspermidine and glutathionylspermidine, respectively. The AdiC antiporter takes up extracellular arginine and excretes intracellular agmatine into the medium. Spermidine is excreted by the MdtJI transporter and imported by the PotABCD spermidine-preferential ATP-binding cassette transporter.

Numerous reports have investigated the role of polyamines in the regulation of biofilm formation. In Yersinia pestis, there is a positive correlation between biofilm formation and putrescine content but not spermidine (26, 27). Norspermidine functions as an intracellular signaling molecule and is necessary for the attachment of Vibrio cholerae to the biotic surface. Moreover, spermine plays a role as a signaling molecule via the NspS/MbaA system of V. cholerae (28, 29). Additionally, norspermidine and spermidine stimulate biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica (30). Furthermore, in Bacillus subtilis, spermidine is required to stimulate robust biofilm formation by interacting with the SlrR regulator to activate the production of exopolysaccharide in the biofilm matrix and increase transcription of tasA operons (31). Burrell et al. (32) reported that biofilm formation was abrogated in an arginine decarboxylase-deficient (speA) B. subtilis strain. This defect was rescued by exogenous supplementation with either spermidine or the putrescine precursor (agmatine), while the addition of putrescine had no effect. Since putrescine is generated from agmatine by agmatinase (SpeB) and can be converted to spermidine by S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SpeD) and spermidine synthase (SpeE) (33, 34), it was unclear whether putrescine was insufficient to stimulate biofilm formation or whether B. subtilis was simply unable to import putrescine. Additionally, Hobley et al. suggested that B. subtilis may take putrescine up from the medium but could be incapable of converting putrescine to spermidine (31).

Among all facultative enteric organisms, Escherichia coli is the predominant species that readily adhere to surfaces and forms biofilms (35). Many studies on E. coli biofilms have been published (36). E. coli synthesizes spermidine, putrescine, and cadaverine. It can synthesize putrescine from arginine through the SpeA-SpeB pathway or from ornithine by ornithine decarboxylase (SpeC) (Fig. 1). Moreover, E. coli has a spermidine preferential uptake transporter, PotABCD, and five putrescine transporters: PotE, PotFGHI, PuuP, PlaP (YeeF), and YdcSTUV (37–44). The overexpression of PotD plays an important role in biofilm formation related to the SOS system (45). Sakamoto et al. demonstrated that exogenous putrescine stimulates biofilm formation and cell viability in E. coli cultures (46). Besides, the addition of putrescine stimulates surface motility on LB glucose semisolid plates (43). Wood et al. (47) reported the motility of E. coli related to the biofilm formation. In their experiment, the strain which demonstrated the highest motility could form the best biofilm. Moreover, Guttenplan and Kearns reported on this phenomenon in 2013; a cyclic-di-GMP is a key regulator to stimulate biofilm formation in many bacteria by activating the protein which relates to motility and, as a result, stimulating biofilm formation (47, 48). Polyamine also affects B. subtilis; however, it was still unclear whether putrescine or spermidine synthesized from putrescine directly promotes biofilm formation.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between polyamines and biofilm formation in E. coli K-12 using a systematic mutagenesis approach. We conclude that, of the polyamines, spermidine specifically promotes biofilm formation. Furthermore, we confirmed that PotD of PotABCD transporter is essential for biofilm formation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparison of biofilm formation between wild-type and polyamine-deficient strains.

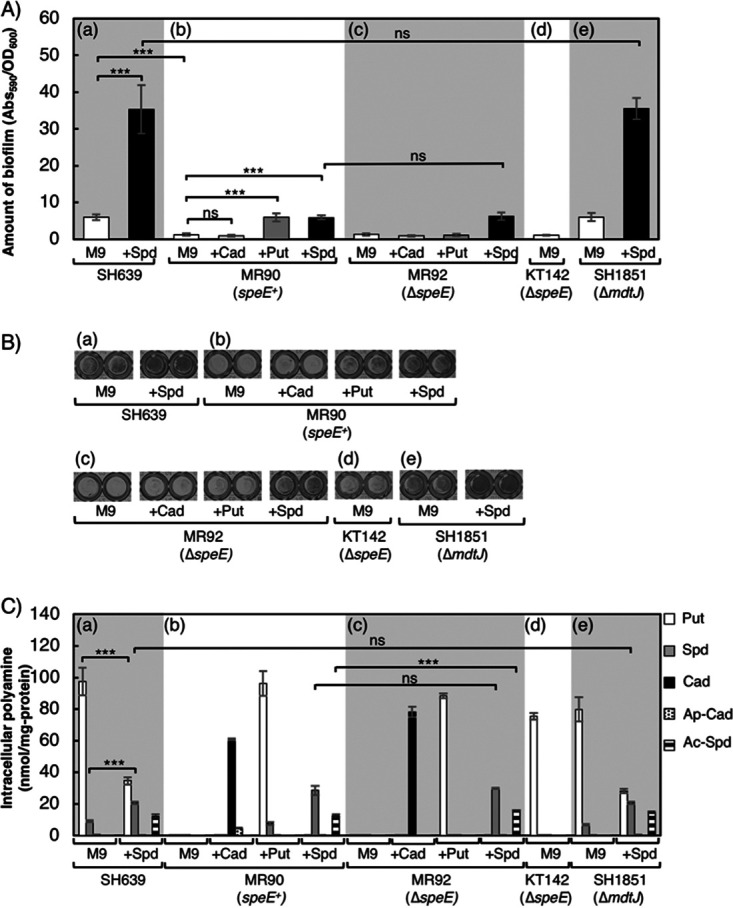

To confirm that polyamines support biofilm formation, the E. coli wild-type strain (SH639) and strain MR90, which has defects in all polyamine-biosynthetic enzymes, were compared. These strains were grown in M9-Gal medium (polyamine-free medium) and incubated for 24 h to allow biofilm formation. SH639 generated a robust biofilm (Fig. 2Aa, M9; Fig. 2Ba, M9), while MR90 could form only a small amount of biofilm (Fig. 2Ab, M9; Fig. 2Bb, M9). Intracellular concentrations of polyamines of the cells in the biofilms were measured. SH639 cells contained 97.4 nmol of putrescine/mg protein, 9.0 nmol of spermidine/mg protein, and a trace amount of cadaverine (Fig. 2Ca, M9). On the other hand, MR90 cells contained no detectable polyamines (Fig. 2Cb, M9). This indicates that polyamines are important for stimulating biofilm formation.

FIG 2.

Effect of polyamines on biofilm formation of various strains. (a) SH639 (wild type); (b) MR90 (putrescine and cadaverine synthesis deficient); (c) MR92 (MR90 but ΔspeE); (d) KT142 (SH639 but ΔspeE); (e) SH1851 (SH639 but ΔmdtJ). (A) Amounts of biofilm formed by the cells, which were statically cultured in M9-Gal medium without (M9) or with (+Cad, +Put, and +Spd) the addition of polyamines at 30°C. Values are averages ± standard deviations (SD). ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different. (B) Biofilm formation of strains grown as indicated in a 96-well plate after treatment with crystal violet. (C) Intracellular polyamine concentrations of the cells in biofilms formed as indicated. Put, putrescine; Spd, spermidine; Cad, cadaverine; Ap-Cad, aminopropylcadaverine; Ac-Spd, and acetylspermidine. Values are averages ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different.

Effect of individual polyamines on biofilm formation.

Although MR90 cannot synthesize polyamines, it still expresses transporters that import cadaverine, putrescine, and spermidine from the medium as well as the wild-type SpeE. SpeE transfers aminopropyl groups from decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine to putrescine to form spermidine. SpeE also catalyzes the transfer of an aminopropyl group to cadaverine to form aminopropylcadaverine as a side reaction (49). To determine which polyamine could enhance the ability to form biofilms, MR90 was grown in M9-Gal medium supplemented with either cadaverine, putrescine, or spermidine (Fig. 2Ab and Fig. 2Bb). After 24 h of incubation, MR90 generated 4.7-fold more biofilm with the addition of putrescine and spermidine than in M9-Gal medium alone. On the other hand, MR90 grown in M9-Gal medium with the addition of cadaverine exhibited no significant difference in biofilm formation. The results indicate that polyamine biosynthesis-deficient E. coli strains can stimulate biofilm formation by the addition of either putrescine or spermidine but not by the addition of cadaverine (Fig. 2Ab and Bb).

The addition of cadaverine in the medium increased the intracellular cadaverine concentration to 60.7 nmol/mg protein and the aminopropylcadaverine concentration to 4.6 nmol/mg protein (Fig. 2Cb, +Cad). Although it was reported that aminopropylcadaverine was synthesized to compensate for the deficiency of putrescine and spermidine physiologically (50, 51), these results indicate that neither cadaverine nor aminopropylcadaverine stimulates biofilm formation, despite their high intracellular accumulation. When putrescine was added to the medium (Fig. 2Cb, +Put), both putrescine (96 nmol/mg protein) and spermidine (7.4 nmol/mg protein) accumulated. Thus, SpeE was likely to synthesize spermidine from putrescine under this condition. With the addition of spermidine to the medium (Fig. 2Cb, +Spd), intracellular acetylspermidine (12.4 nmol/mg protein) was detected in addition to spermidine (28.5 nmol/mg protein). Acetylspermidine is generated by SpeG through the transfer of the acetyl group from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) when intracellular spermidine concentrations are too high. Acetylspermidine is the inactive state of spermidine (Fig. 1) and is supposed to be excreted from cells (52, 53), but no detectable acetylspermidine was found in the medium. These results demonstrate that putrescine and/or spermidine could stimulate biofilm formation in the MR90 strain, but cadaverine could not.

Spermidine, but not putrescine, promotes biofilm formation.

The addition of both spermidine and putrescine stimulated biofilm formation of MR90. Since MR90 can make spermidine from putrescine, it is not clear whether putrescine stimulates biofilm formation directly or whether spermidine synthesized from putrescine stimulates biofilm formation (Fig. 2Ab, Fig. 2Bb, and Fig. 2Cb). To evaluate whether putrescine can stimulate biofilm formation directly, we constructed MR92, which is a SpeE-deficient derivative of MR90. MR92 was grown in M9-Gal medium without or with the addition of polyamines (Fig. 2Ac, Bc, and Cc). MR92 formed a robust biofilm with the addition of spermidine, while it formed only a small amount of biofilm even with the addition of the cadaverine and putrescine. Intracellular concentrations of cadaverine and putrescine in strain MR92 (ΔspeE) cells grown with the addition of cadaverine and putrescine were 78.2 and 88.4 nmol/mg protein, respectively, whereas neither aminopropylcadaverine nor spermidine was detected. These results indicate that putrescine cannot directly stimulate biofilm formation but does so indirectly through spermidine synthesis.

These results suggest that E. coli has a limitation system for intracellular spermidine concentrations which is regulated by converting spermidine into acetylspermidine. This result correlates with results of previous studies (54–56) showing that the overaccumulation of spermidine leads to cell toxicity and that excess spermidine is converted to acetylspermidine by SpeG.

SpeE-deficient E. coli strain has reduced biofilm formation.

The addition of exogenous spermidine stimulated biofilm formation in MR90 and MR92 strains. To clarify whether spermidine is essential to stimulate biofilm formation, we compared the wild-type strain SH639 to KT142, which is deficient in the spermidine synthase gene (ΔspeE). After culturing in M9-Gal medium, the wild-type strain generated a robust biofilm (Fig. 2Aa, M9, and Fig. 2Ba, M9), whereas the ΔspeE strain could form only a small amount of biofilm (Fig. 2Ad and Bd). The intracellular concentration of polyamines is shown in Fig. 2Ca, M9, and Cd. Both SH639 and KT142 synthesized putrescine by themselves. However, only the wild-type strain (SH639) could generate spermidine from putrescine (Fig. 2Ca, M9). These results confirm that spermidine stimulates biofilm formation.

Exogenous spermidine stimulates biofilm formation of wild-type E. coli.

To confirm whether exogenous spermidine accelerates biofilm formation in the wild-type strain, the amount of biofilm formed by SH639 was measured without or with the addition of exogenous spermidine. Figure 2Aa and Ba show that the amount of biofilm formed by SH639 supplemented with spermidine was significantly larger than that without the addition of spermidine. With the addition of spermidine to the medium, the amount of intracellular spermidine was increased, but the amount of intracellular putrescine was decreased through repression and feedback inhibition of SpeA (15, 57, 58) (Fig. 2Ca). It is also suggested that the uptake of spermidine into the cells is not regulated by the high intracellular spermidine concentration. These results confirm that the intracellular concentration of spermidine in the wild-type strain increases with the addition of spermidine to the medium and stimulates biofilm formation.

Influence of spermidine exporter MdtJI on biofilm formation.

It has been previously reported that the protein complex MdtJI is a spermidine exporter (51). Strain SH1851, which lacks mdtJ, was constructed, and the effects of ΔmdtJ on intracellular spermidine concentration and biofilm formation were assessed. As shown in Fig. 2, there was no significant difference in intracellular spermidine concentrations (Fig. 2Ca and Ce) and biofilm formation (Fig. 2Aa and Ae) between SH639 and SH1851 strains, even when they were grown in medium supplemented with spermidine.

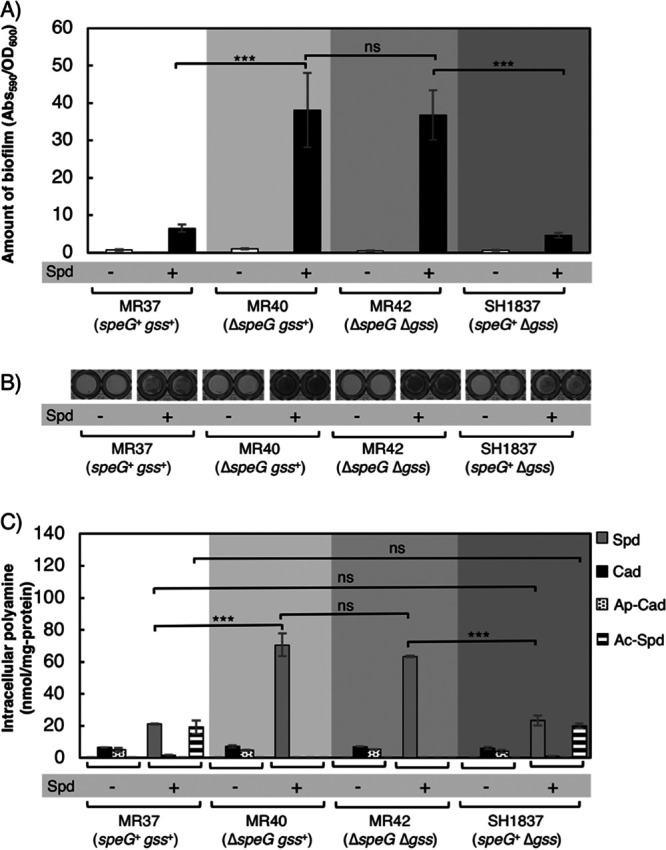

Comparison of the effects of spermidine acetyltransferase and glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase on biofilm formation in E. coli.

SpeG and glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase (Gss) convert spermidine to acetylspermidine and glutathionylspermidine, respectively (53, 59, 60). The putrescine biosynthesis-deficient strain MR37 (speG+ gss+) and its derivatives, MR40 (ΔspeG gss+), MR42 (ΔspeG Δgss), and SH1837 (speG+ Δgss), were constructed to compare the effects of SpeG and Gss on biofilm formation. Among these strains, ΔspeG strains (MR40 and MR42) formed denser biofilms than the corresponding speG+ strains (MR37 and SH1837) when they were grown in medium supplemented with spermidine (Fig. 3A and B). Additionally, there was no difference in biofilm formation among all of the strains grown in M9-Gal medium. There were no significant differences in biofilm formation and the intracellular amount of spermidine in MR40 (ΔspeG gss+) and MR42 (ΔspeG Δgss) strains grown in M9-Gal medium with the addition of spermidine (Fig. 3). Whether strains were Gss+ or Gss− did not affect intracellular spermidine concentrations, but SpeG+ or SpeG− status had a decisive effect on this measure, which affected the amount of biofilm. Because of the energetic effect, converting spermidine to acetylspermidine is more favorable for E. coli than synthesizing glutathionylspermidine (61).

FIG 3.

Comparison of the effects of spermidine acetyltransferase and glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase on biofilm formation. (A) The amount of biofilm formed by the strains. MR37 (speG+ gss+), MR40 (ΔspeG gss+), MR42 (ΔspeG Δgss), and SH1837 (speG+ Δgss) grown in M9-Gal medium without (−) or with (+) the addition of 400 μM spermidine. These four strains cannot synthesize putrescine. Values are averages ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different. (B) Biofilm formation of strains grown as indicated in a 96-well plate after treatment with crystal violet. (C) Intracellular concentrations of polyamines of the cells in biofilms formed as indicated. Spd, spermidine; Cad, cadaverine; Ap-Cad, aminopropylcadaverine; Ac-Spd, acetylspermidine; ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different. Values are averages ± SD.

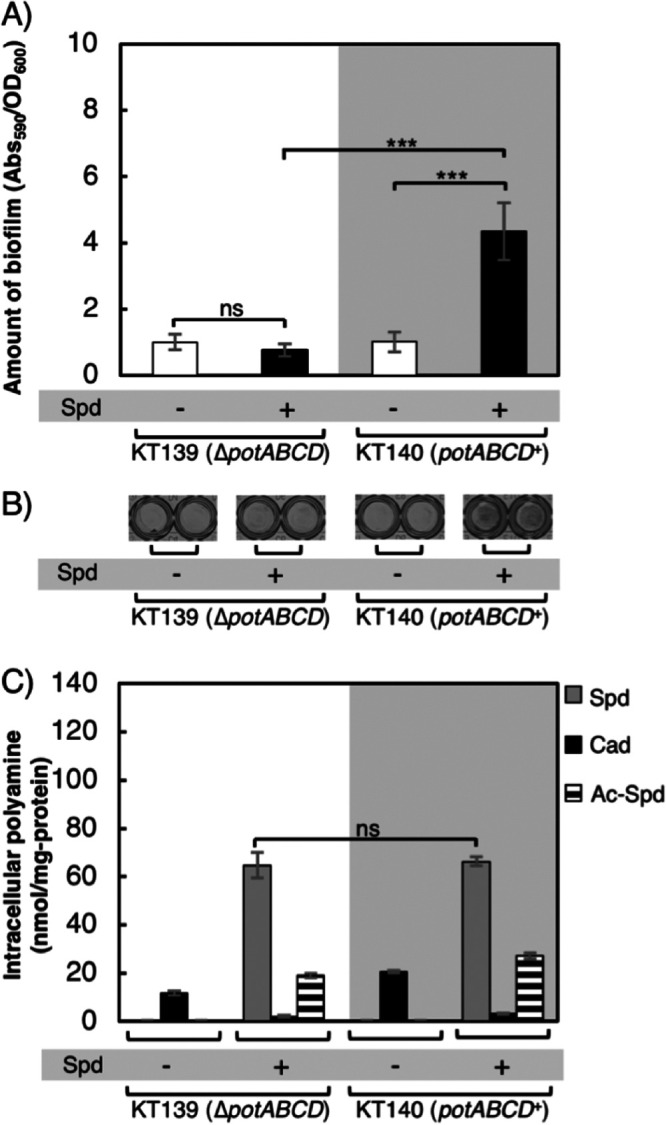

Effect of PotABCD transporter on biofilm formation.

The potABCD operon is reported to encode the spermidine transporter (37, 38). We assessed whether this transporter is essential for biofilm formation for strains which cannot synthesize putrescine and spermidine (KT139 and KT140) in medium supplemented with spermidine. KT139 lacks the potABCD operon, while KT140 possesses the intact potABCD operon (potABCD+). As expected, biofilm formation for KT140 was significantly higher than that of KT139 when these strains were grown in medium supplemented with spermidine (Fig. 4A and B). To our surprise, however, there was no significant difference in intracellular polyamine concentrations between KT139 and KT140 (Fig. 4C). The method we used to measure the amount of intracellular spermidine cannot completely rule out the possibility that spermidine stuck to the cell surface was included. However, we think that the values we obtained by our method accurately represent the amounts of intracellular polyamine. This is because even when the same amount of spermidine was added to the culture media of MR37 and MR40, which are defective in de novo synthesis of putrescine and spermidine, their intracellular spermidine concentrations were very different (Fig. 3C). Spermidine was taken up by the KT139 (ΔpotABCD) strain, and its intracellular concentration was comparable to that of KT140, but biofilm formation of KT139 was not augmented by the addition of spermidine as in KT140 (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Effect of PotABCD protein on biofilm formation. (A) Amounts of biofilm formed by strains KT139 (ΔpotABCD) and KT140 (potABCD+), both of which cannot synthesize putrescine and spermidine, grown in M9-Gal medium without (−) or with (+) the addition of 400 μM spermidine. Values are averages ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different. (B) Biofilm formation of strains grown as indicated in a 96-well plate after treatment with crystal violet. (C) Intracellular concentrations of polyamines of the cells in biofilms formed as indicated. Spd, spermidine; Cad, cadaverine; Ac-Spd, acetylspermidine; ns, not significantly different. Values are averages ± SD.

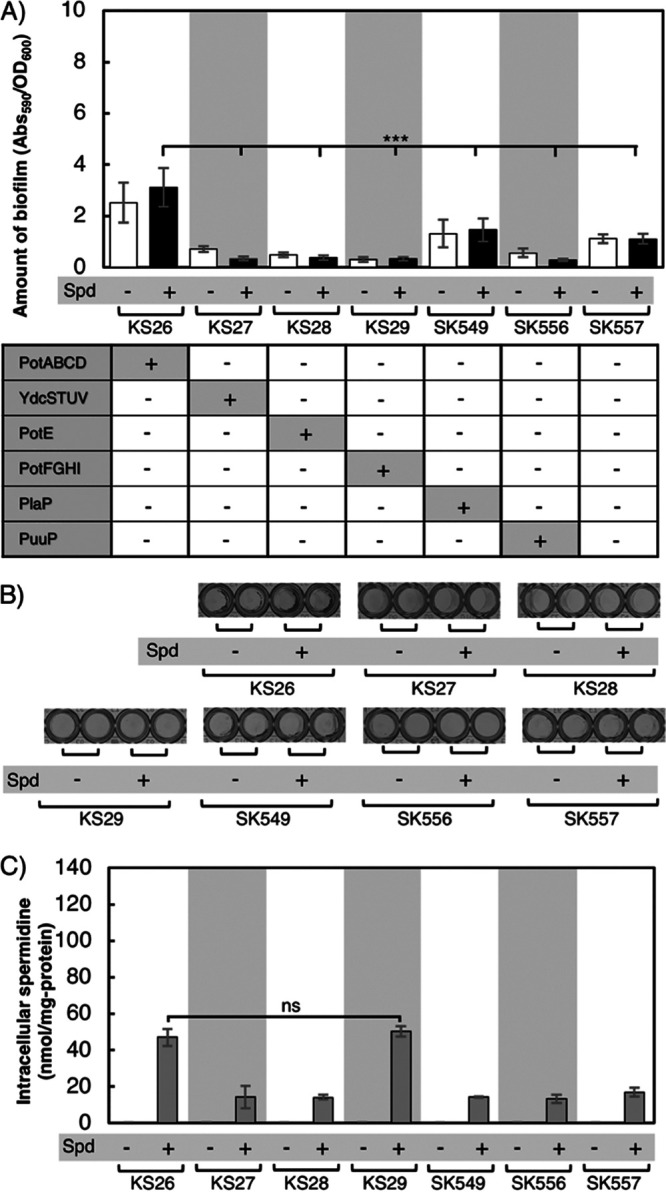

It is quite possible that spermidine is imported by another transporter(s) aside from PotABCD. We speculated that a putrescine transporter(s) may transport spermidine into the cells. Five putrescine transporters have been identified in E. coli: YdcSTUV, PotE, PotFGHI, PlaP (YeeF), and PuuP (37–44). To evaluate the relationship between spermidine uptake and putrescine transporters, we constructed strains which cannot synthesize putrescine, deleted PotABCD, and deleted all but one of the putrescine transporters; KS27 (ydcSTUV+), KS28 (potE+), KS29 (potFGHI+), SK549 (plaP+), and SK556 (puuP+). KS26 lacked all five putrescine transporters but was PotABCD+, and SK557 lacked all five putrescine transporters and PotABCD. Biofilm formation of these seven strains was compared (Fig. 5A and B). KS26 formed a larger amount of biofilm in M9-Gal medium supplemented with 400 μM spermidine than the other strains. Strains SK549 and SK557 showed slightly higher A590/optical density at 600 nm (OD600) than KS27, KS28, KS29, and SK556. This is because the OD600 of SK549 and SK557 were slightly smaller than those of the other four strains. Interestingly, the intracellular spermidine concentrations of KS26 and KS29 strains were significantly different from those of the other strains (KS27, KS28, SK549, SK556, and SK557) when grown in medium supplemented with spermidine. However, there was no significant difference between the intracellular spermidine concentration of KS26 and KS29. This result suggests that PotFGHI can also function as compensatory importers of spermidine when PotABCD is absent under the biofilm-forming conditions. This result contradicts the previous report by Pistocchi et al., though they did not check if PotFGHI can uptake spermidine under the biofilm-forming condition (40). Even though KT139 and KS29 had high intracellular spermidine concentrations (Fig. 4C and 5C), their biofilm formation was not stimulated like that of the PotABCD+ strains (KT140 and KS26) (Fig. 4A and B and 5A and B).

FIG 5.

Evaluation of whether some of the known putrescine transporters can take up spermidine from the medium to compensate for the deficiency of potABCD. (A) Amounts of biofilm formed. KS26 lacks all five known putrescine transporters but is potABCD+. KS27, KS28, KS29, SK549, and SK556 lack the potABCD operon and all known putrescine transporters, except one. SK557 lacks all putrescine transporters and PotABCD. These strains cannot synthesize putrescine. All strains were grown in M9-Gal medium without (−) or with (+) the addition of 400 μM spermidine. Values are averages ± SD. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Biofilm formation of strains grown as indicated in a 96-well plate after treatment with crystal violet. (C) Intracellular concentrations of spermidine in strains KS26, KS27, KS28, KS29, SK549, SK556, and SK557 grown and washed three times with PBS. ns, not significantly different. Values are averages ± SD.

These results suggested that both high intracellular concentrations of spermidine and the PotABCD protein itself play an important role in biofilm formation. It was previously reported that overexpression of PotD, the periplasmic binding protein of the PotABCD transporter, enhances biofilm formation in E. coli (45). This may be true in our case, although our strains express PotABCD from the genome using the wild-type promoter(s).

When grown in a medium without spermidine, strains KT139 and KT140, which cannot synthesize putrescine or spermidine, exhibited increased intracellular accumulation of cadaverine; however, this accumulation was not observed when the strains were grown in the presence of spermidine. This finding is consistent with a previous study which reported that intracellular cadaverine concentration increases as a compensatory polyamine when neither putrescine nor spermidine is synthesized de novo or supplied exogenously (50, 51). Figure 5C shows that strains KS27, KS28, SK549, SK556, and SK557 accumulated nonnegligible amounts of spermidine in cells when grown in medium supplemented with spermidine. This amount of spermidine in the cells is equivalent to that found in the cells of SH639 grown in M9-Gal medium (Fig. 2Ca, M9). This indicates that E. coli possesses an unidentified spermidine transporter. These results suggest that intracellular accumulation of spermidine is not the only factor that promotes biofilm formation and that PotABCD proteins affect biofilm formation by a mechanism independent of its transporter activity. PotD functions as a periplasmic binding protein of PotABCD transporter and affects the polyamine content in E. coli cells by taking up spermidine from the medium (62, 63). Besides its role as a periplasmic binding protein, PotD could have a regulatory role on the transcription of potABCD operon (64).

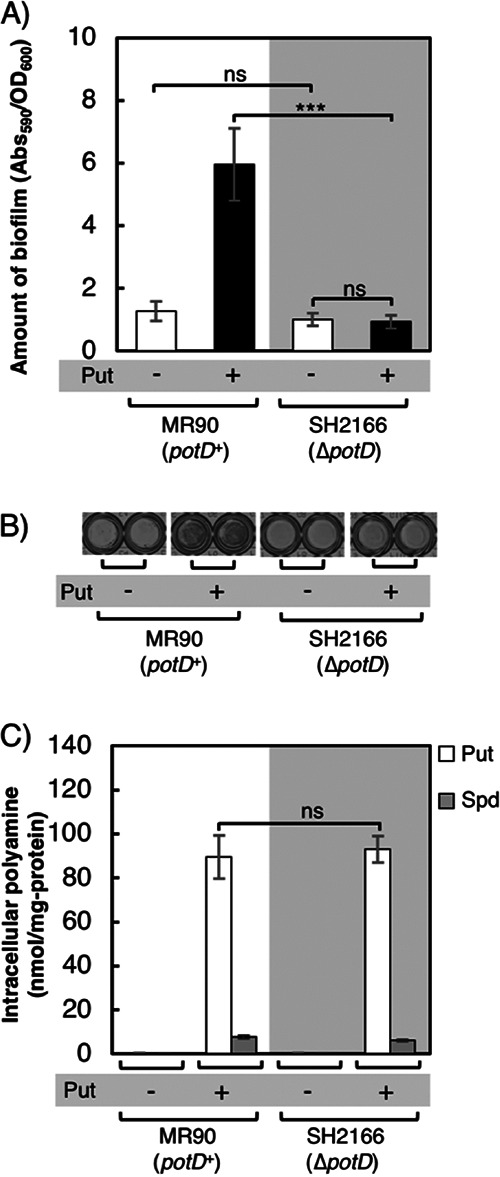

Deletion of PotD abolishes biofilm formation.

To confirm the effect of PotD protein on biofilm formation, we constructed a PotD deletion strain (SH2166) and compared it with the parental strain, MR90 (speE+). Though potC and potD have overlapping coding regions, the ΔpotD::FRT-kan+-FRT strain of the Keio collection has a complete potC gene, and the deletion of the potD gene starts from the second codon (65). Biofilm formation was compared in M9-Gal medium without or with the addition of putrescine. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, biofilm formation was not different between the two strains (MR90 and SH2166) grown in M9-Gal medium. Interestingly, supplementation of putrescine promoted robust biofilm formation of the potD+ strain, whereas the ΔpotD strain (SH2166) could form only a small amount of biofilm in the same medium, even though no significant difference was observed in the intracellular polyamines (Fig. 6C). This result was similar to the previous report by Zhang et al. that PotD is associated with biofilm formation in E. coli (45). However, in that study, the researchers overexpressed potD and did not measure intracellular polyamine concentrations. They concluded that PotD protein affects the rate of polyamine synthesis and activates the transcription of genes related to the SOS system followed by stimulation of biofilm formation. However, our results showed that even though there existed similar amounts of intracellular putrescine and spermidine (Fig. 6C), the presence or absence of PotD strongly affected biofilm formation (Fig. 6A). This result indicates that PotD regulates biofilm formation through an unknown different pathway besides polyamine synthesis.

FIG 6.

Stimulation of biofilm formation by PotD. (A) Amounts of biofilm formed by strains MR90 (potD+) and SH2166 (ΔpotD) grown in M9-Gal medium without (−) or with (+) the addition of 400 μM putrescine. These strains cannot synthesize putrescine and cadaverine. Values are averages ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; ns, not significantly different. (B) Biofilm formation of strains grown as indicated in a 96-well plate after treatment with crystal violet. (C) Intracellular concentrations of polyamines of the cells in biofilms formed as indicated. Bars indicate the amounts of putrescine (Put) and spermidine (Spd). ns, not significantly different. Values are averages ± SD.

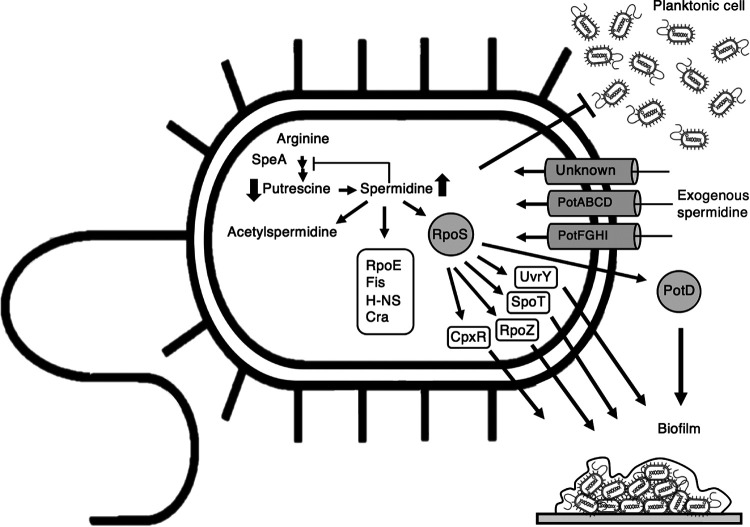

In this study, we found that a high intracellular spermidine concentration promotes biofilm formation in E. coli cells. Moreover, acetylspermidine is produced when the intracellular concentration of spermidine becomes very high. It was previously reported that polyamine regulates many genes and regulators. Igarashi and Kashiwagi discovered that the translation of various proteins was stimulated by polyamine (66). Among them, RpoS is a sigma factor required at the stationary phase. The DNA-binding transcriptional activator UvrY, DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator CpxR, bifunctional (p)ppGpp synthase/hydrolase SpoT, and ω subunit of RNA polymerase (RpoZ) are the proteins which are expressed at stationary phase and could stimulate biofilm formation (67). Mitra et al. reported the mutation of uvrY in E. coli repressed biofilm formation (68). Many studies have shown that CpxR also affects biofilm formation (69–71). The report of Balzer and McLean mentioned that SpoT affects biofilm production under low-nutrition conditions (72). Also, the RpoZ mutant strain is defective in biofilm formation in minimal media (73). Sigma E (RpoE), sigma S (RpoS), DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator Fis, DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator H-NS, and DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator Cra are related to the transition from the planktonic state to biofilm. Translation of these proteins is activated by polyamine (66, 67, 74). The deletion of potABCD did not completely abolish spermidine uptake, and we found that PotFGHI can function as a spermidine transporter. Besides PotABCD and PotFGHI, there might exist a currently unidentified transporter which can take up spermidine. Finally, the spermidine transporter protein PotD is likely to be involved in biofilm formation (Fig. 7). As discussed above, PotD has an unknown regulatory role in biofilm formation in addition to the periplasmic binding protein of the transporter and the regulator of polyamine synthesis.

FIG 7.

Schematic of biofilm formation under excessive spermidine conditions in E. coli. Exogenous spermidine is taken up into bacterial cells through transporters (PotABCD, PotFGHI, and an unknown transporter[s]). Spermidine induces the bacteria to form a biofilm. An excessive amount of spermidine directly represses and inhibits putrescine synthesis through feedback inhibition on arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) (15). In addition, the high level of spermidine stimulates translation of the RpoS transcription regulator which, regulates transcription of genes in stationary phase. RpoS stimulates the transcription of the genes for UvrY, CpxR, SpoT, and RpoZ, and this results in acceleration of the biofilm formation. Moreover, the translation of RpoE, Fis, H-NS, and Cra proteins could be activated by polyamine (66, 67, 74), and these proteins are related to transition from the planktonic state to biofilm. However, since a high concentration of spermidine is toxic to the cells, E. coli transforms spermidine into its nonactive derivative, acetylspermidine. It was suggested that not only spermidine but also PotD protein has positive effects on biofilm production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cultivation conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. They are all derivatives of E. coli K-12. The chromosomal genes gss, mdtJ, speE, cadA, ldcC, and potD were replaced with FRT (FLP recombination target)-kan+-FRT from the Keio gene knockout collection using P1vir transduction (65). The speF, speG, and speAB genes were disrupted as described elsewhere (75) using PCR products amplified using pKD13 as a template and with del_speF_F_pKD13 and del_speF_R_pKD13, del_speG_F_pKD13 and del_speG_ R _pKD13, and speAB-F and speAB-R as primers, respectively (Table 2). The speC gene was disrupted similarly using pKD3 as a template with speC-F and speC-R as primers. The mutations were compiled through P1vir transduction (76). The puuP gene was disrupted as described previously (42). The kan+ and cat+ genes were eliminated from FRT-kan+-FRT and FRT-cat+-FRT, respectively, by Flp flippase carried by pCP20 (75). Colony PCRs were performed with primers that annealed upstream and downstream of the genomic regions containing the mutations, and the sizes of amplified DNA were measured to confirm the deletions.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| KS26 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔplaP::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔpuuP::tet+ ΔydcSTUV::FRT | This study |

| KS27 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔplaP::FRT ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔpuuP::tet | This study |

| KS28 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔplaP::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔpuuP::tet+ ΔydcSTUV::FRT | This study |

| KS29 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔplaP::FRT ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔpuuP::tet+ ΔydcSTUV::FRT | This study |

| KT139 | KT140 except ΔpotABCD::FRT-cat+-FRT | This study |

| KT140 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT ΔspeC::FRT ΔspeE::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| KT142 | SH639 except ΔspeE::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| MG1655 | F− rph-1 | C. A. Gross |

| MR37 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT ΔspeC::FRT ΔspeF::FRT | This study |

| MR40 | MR37 except ΔspeG::FRT | This study |

| MR42 | MR37 except ΔspeG::FRT Δgss::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| MR90 | MR37 except ΔcadA::FRT ΔldcC::FRT | This study |

| MR92 | MR37 except ΔcadA::FRT ΔldcC::FRT ΔspeE::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| SH639 | MG1655 except Δggt-2 | 79 |

| SH1837 | MR37 except Δgss::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| SH1851 | SH639 except ΔmdtJ::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| SH2166 | MR90 except ΔpotD::FRT-kan+-FRT | This study |

| SK497 | MG1655 except ΔspeG::FRT-kan+-FRT | Laboratory stock |

| SK549 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔpuuP::tet+ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔydcSTUV::FRT | Laboratory stock |

| SK556 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔplaP::FRT ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔydcSTUV::FRT | Laboratory stock |

| SK557 | SH639 except ΔspeAB::FRT-kan+-FRT ΔspeC::FRT ΔpotE::FRT ΔpuuP::tet+ΔpotABCD::FRT ΔpotFGHI::FRT ΔplaP::FRT-cat+-FRT ΔydcSTUV::FRT | Laboratory stock |

| pCP20 | pSC101 replicon (Ts) bla+ cat+ Flp (λRp) cI857 | 75 |

| pKD3 | oriRγ bla+ FRT-cat+-FRT | 75 |

| pKD13 | oriRγ bla+ FRT-kan+-FRT | 75 |

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| del_speF_F_pKD13 | 5′-AATTGAGGACCTGCTATTACCTAAAATAAAGAGATGAAAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| del_speF_R_pKD13 | 5′-GTTAACTGAACGACGCCCATTTTGTTCGATTTAGCCTGACATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ |

| del_speG_F_pKD13 | 5′-CCCTAACCTGTTATTGATTTAAGGAATGTAAGGACACGTTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| del_speG_R_pKD13 | 5′-GGTTTACACCATCAAAAATACGATCGATTATTATTAATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ |

| speAB-F | 5′-CCGACATTAATGGCACGTTTTACCCGTGCGCATCGCATCTGGTGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| speAB-R | 5′-AGTCGTTAACTGTTTTACACTTAATAAAATAATTTGAGGTTCGCTATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC-3′ |

| speC-F | 5′-GCAAAGAAAAACGGGTCGCCAGAAGGTGACCCG TTTTTTTTATTCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′ |

| speC-R | 5′-TGATGTCTGGCGGTCGGAGCTGGTGACCAGTTTGACCCATATCTCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′ |

For DNA manipulation and strain construction, cultures were grown in LB medium (76). Where appropriate, cultures were supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml tetracycline, or 100 μg/ml ampicillin. For the biofilm precultures, a single colony was used to inoculate 10 ml of M9 medium, which does not contain polyamines and is supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) galactose, in 100-ml flasks. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with reciprocal shaking at 140 rpm.

Quantification of biofilm formation.

Precultures were incubated for 16 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in M9-Gal medium. E. coli strains were diluted in a 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Iwaki, Shizuoka, Japan) containing 100 μl of M9-Gal medium in the presence or absence of 400 μM putrescine, cadaverine, or spermidine. The initial densities of the cells were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05. Plates were then incubated at 30°C for 24 h to allow biofilm formation. Culture supernatants (containing planktonic cells) were removed from the wells, and the OD600 of each was measured to determine the cell density with a GeneQuant100 spectrophotometer (GeneQuant100; Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). To measure the amounts of biofilms formed, biofilms in the wells were stained with 200 μl of 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet solution. Plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 20 min, the crystal violet solution was removed, and the wells were washed twice with 200 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After the microtiter plate had been dried by being turned upside down, the stained cells within the biofilms were solubilized by incubating at room temperature with 200 μl of an 80% ethanol–20% acetone (vol/vol) solution for 20 min. Then, 150 μl of solutions was transferred from each well to a new 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate (Iwaki). The amounts of biofilms were then assessed by determining the A590 of the resulting solutions with a VersaMax plate reader (VersaMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). When the A590 was too high, the solution was diluted with an 80% ethanol–20% acetone (vol/vol) solution. The level of biofilm formation of each strain was expressed as the average of A590 of the biofilm solution of each well divided by OD600 of the culture supernatant of each well, which was obtained from triplicate independent experiment sets (n = 10 in each set), and the results are shown with standard deviations.

Analysis of intracellular polyamine concentrations.

Intracellular concentrations of polyamines were measured in the strains grown in a 60-mm polystyrene dish (Iwaki) containing 4 ml of M9-Gal medium. The initial densities of the cells were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05. Plates were then incubated under biofilm-inducing conditions in the presence or absence of exogenous polyamines. After the medium was removed, the biofilms were scraped off the culture dish and collected by centrifugation. Pellets were washed twice (or three times for Fig. 4) with 1 ml of PBS, and lysates were generated by resuspending the pellets in 0.2 ml of 5% trichloroacetic acid (wt/vol) (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) followed by boiling for 15 min. Supernatants were filtered through Millex-LH filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and the concentrations of polyamines were measured using an LC-20 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) device (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a TSKgel Polyaminepak (Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously (77). The only modifications were that the column temperature was set at 50°C and only one mobile-phase solution (mobile phase II) was used. This system can separate and detect putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, and aminopropylcadaverine levels with elution times of 6, 8, 11, and 15 min, respectively. The flow rate of the mobile phase solution was 0.5 ml/min, and that of the detection reagent was 0.42 ml/min. The two buffer systems described previously (77) were used for acetylspermidine analysis, which was detected at 18 min. Standard acetylspermidine, putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, and aminopropylcadaverine were purchased from Nacalai Tesque. The precipitated protein was dissolved in 0.2 ml of 0.1 N NaOH. The protein concentration was measured using the Lowry Folin assay using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard (78), and the polyamine concentrations were calculated in nanomoles per milligram of protein. Polyamine quantities are presented as the averages for three cultures with standard deviations.

Data analysis.

All data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, New York, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine significant differences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research 23658079 to H.S. from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kera K, Nagayama T, Nanatani K, Saeki-Yamoto C, Tominaga A, Souma S, Miura N, Takeda K, Kayamori S, Ando E, Higashi K, Igarashi K, Uozumi N. 2018. Reduction of spermidine content resulting from inactivation of two arginine decarboxylases increases biofilm formation in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 200:e00664-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00664-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flemming HC, Wingender J. 2010. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougald D, Rice SA, Barraud N, Steinberg PD, Kjelleberg S. 2011. Should we stay or should we go: mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:39–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candela T, Maes E, Garénaux E, Rombouts Y, Krzewinski F, Gohar M, Guérardel Y. 2011. Environmental and biofilm-dependent changes in a Bacillus cereus secondary cell wall polysaccharide. J Biol Chem 286:31250–31262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitchurch CB, Tolker-Nielsen T, Ragas PC, Mattick JS. 2002. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science 295:1487–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies D. 2003. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2:114–122. doi: 10.1038/nrd1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. 2016. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumbaugh KP, Sauer K. 2020. Biofilm dispersion. Nat Rev Microbiol 18:571–586. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Y, Geng M, Bai L. 2020. Targeting biofilms therapy: current research strategies and development hurdles. Microorganisms 8:1222. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mah TFC, O'Toole GA. 2001. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol 9:34–39. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01913-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu L, Hu W, Tian Z, Yuan D, Yi G, Zhou Y, Cheng Q, Zhu J, Li M. 2019. Developing natural products as potential anti-biofilm agents. Chin Med 14:11. doi: 10.1186/s13020-019-0232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Chua TK, Tkaczuk KL, Bujnicki JM, Sivaraman J. 2010. The crystal structure of Escherichia coli spermidine synthase SpeE reveals a unique substrate-binding pocket. J Struct Biol 169:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabor CW, Tabor H. 1985. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev 49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/MR.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pegg AE. 1986. Recent advances in the biochemistry of polyamines in eukaryotes. Biochem J 234:249–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2340249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michael AJ. 2016. Polyamines in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. J Biol Chem 291:14896–14903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.734780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heby O. 1981. Role of polyamines in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation. Differentiation 19:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feuerstein BG, Williams LD, Basu HS, Marton LJ. 1991. Implications and concepts of polyamine–nucleic acid interactions. J Cell Biochem 46:37–47. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. 2019. The functional role of polyamines in eukaryotic cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 107:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michael AJ. 2018. Polyamine function in archaea and bacteria. J Biol Chem 293:18693–18701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.005670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerner EW, Meyskens FL. 2004. Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nat Rev Cancer 4:781–792. doi: 10.1038/nrc1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allmeroth K, Kim CS, Annibal A, Pouikli A, Chacón-Martínez CA, Latza C, Antebi A, Tessarz P, Wickström SA, Denzel MS. 2020. Polyamine-controlled proliferation and protein biosynthesis are independent determinants of hair follicle stem cell fate. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/2020.04.30.070201. [DOI]

- 24.Veen S, Martin S, Haute CV, Benoy V, Lyons J, Vanhoutte R, Kahler JP, Decuypere JP, Gelders G, Lambie E, Zielich J, Swinnen JV, Annaert W, Agostinis P, Ghesquière B, Verhelst S, Baekelandt V, Eggermont J, Vangheluwe P. 2020. ATP13A2 deficiency disrupts lysosomal polyamine export. Nature 578:419–424. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1968-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakamoto A, Sahara J, Kawai G, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Uemura T, Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K, Terui Y. 2020. Cytotoxic mechanism of excess polyamines functions through translational repression of specific proteins encoded by polyamine modulon. Int J Mol Sci 21:2406. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel CN, Wortham BW, Lines JL, Fetherston JD, Perry RD, Oliveira MA. 2006. Polyamines are essential for the formation of plague biofilm. J Bacteriol 188:2355–2363. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2355-2363.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wortham BW, Oliveira MA, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. 2010. Polyamines are required for the expression of key Hms proteins important for Yersinia pestis biofilm formation. Environ Microbiol 12:2034–2047. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karatan E, Duncan TR, Watnick PI. 2005. NspS, a predicted polyamine sensor, mediates activation of Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation by norspermidine. J Bacteriol 187:7434–7443. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7434-7443.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Sperandio V, Frantz DE, Longgood J, Camilli A, Phillips MA, Michael AJ. 2009. An alternative polyamine biosynthetic pathway is widespread in bacteria and essential for biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem 284:9899–9907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900110200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nesse LL, Berg K, Vestby LK. 2015. Effects of norspermidine and spermidine on biofilm formation by potentially pathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica wild-type strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2226–2232. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03518-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hobley L, Li B, Wood JL, Kim SH, Naidoo J, Ferreira AS, Khomutov M, Khomutov A, Stanley-Wall NR, Michael AJ. 2017. Spermidine promotes Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation by activating expression of the matrix regulator slrR. J Biol Chem 292:12041–12053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.789644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burrell M, Hanfrey CC, Murray EJ, Stanley-Wall NR, Michael AJ. 2010. Evolution and multiplicity of arginine decarboxylases in polyamine biosynthesis and essential role in Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. J Biol Chem 285:39224–39238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekowska A, Bertin P, Danchin A. 1998. Characterization of polyamine synthesis pathway in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol Microbiol 29:851–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekowska A, Coppée JY, Le Caer JP, Martin–Verstraete I, Danchin A. 2000. S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase of Bacillus subtilis is closely related to archaebacterial counterparts. Mol Microbiol 36:1135–1147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun F, Yuan Q, Wang Y, Cheng L, Li X, Feng W, Xia P. 2020. Sub-minimum inhibitory concentration ceftazidime inhibits Escherichia coli biofilm formation by influencing the levels of the ibpA gene and extracellular indole. J Chemother 32:7–14. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2019.1678913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beloin C, Roux A, Ghigo JM. 2008. Escherichia coli biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322:249–289. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuchi T, Kashiwagi K, Kobayashi H, Igarashi K. 1991. Characteristics of the gene for a spermidine and putrescine transport system that maps at 15 min on the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Biol Chem 266:20928–20933. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashiwagi K, Miyamoto S, Nukui E, Kobayashi H, Igarashi K. 1993. Functions of PotA and PotD proteins in spermidine-preferential uptake system in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 268:19358–19363. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kashiwagi K, Miyamoto S, Suzuki F, Kobayashi H, Igarashi K. 1992. Excretion of putrescine by the putrescine-ornithine antiporter encoded by the potE gene of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:4529–4533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pistocchi R, Kashiwagi K, Miyamoto S, Nukui E, Sadakata Y, Kobayashi H, Igarashi K. 1993. Characteristics of the operon for a putrescine transport system that maps at 19 minutes on the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Biol Chem 268:146–152. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)54126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurihara S, Oda S, Kato K, Kim HG, Koyanagi T, Kumagai H, Suzuki H. 2005. A novel putrescine utilization pathway involves γ-glutamylated intermediates of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 280:4602–4608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurihara S, Tsuboi Y, Oda S, Kim HG, Kumagai H, Suzuki H. 2009. The putrescine importer PuuP of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 191:2776–2782. doi: 10.1128/JB.01314-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurihara S, Suzuki H, Oshida M, Benno Y. 2011. A novel putrescine importer required for type 1 pili-driven surface motility induced by extracellular putrescine in Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 286:10185–10192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saier MH, Jr, Reddy VS, Tsu BV, Ahmed MS, Li C, Moreno-Hagelsieb G. 2016. The transporter classification database (TCDB): recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D372–D379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, Zhang Y, Liu J, Liu H. 2013. PotD protein stimulates biofilm formation by Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett 35:1099–1106. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakamoto A, Terui Y, Yamamoto T, Kasahara T, Nakamura M, Tomitori H, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Michael AJ, Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. 2012. Enhanced biofilm formation and/or cell viability by polyamines through stimulation of response regulators UvrY and CpxR in the two-component signal transducing systems, and ribosome recycling factor. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44:1877–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood TK, Barrios AFG, Herzberg M, Lee J. 2006. Motility influences biofilm architecture in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 72:361–367. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guttenplan SB, Kearns DB. 2013. Regulation of flagellar motility during biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:849–871. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman WH, Tabor CW, Tabor H. 1973. Spermidine biosynthesis. Purification and properties of propylamine transferase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 248:2480–2486. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K, Hamasaki H, Miura A, Kakegawa T, Hirose S, Matsuzaki S. 1986. Formation of a compensatory polyamine by Escherichia coli polyamine-requiring mutants during growth in the absence of polyamines. J Bacteriol 166:128–134. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.1.128-134.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higashi K, Ishigure H, Demizu R, Uemura T, Nishino K, Yamaguchi A, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. 2008. Identification of a spermidine excretion protein complex (MdtJI) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190:872–878. doi: 10.1128/JB.01505-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filippova EV, Weigand S, Kiryukhina O, Wolfe AJ, Anderson WF. 2019. Analysis of crystalline and solution states of ligand-free spermidine N-acetyltransferase (SpeG) from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75:545–553. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319006545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Limsuwun K, Jones PG. 2000. Spermidine acetyltransferase is required to prevent spermidine toxicity at low temperatures in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 182:5373–5380. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5373-5380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He Y, Kashiwagi K, Fukuchi J, Terao K, Shirahata A, Igarashi K. 1993. Correlation between the inhibition of cell growth by accumulated polyamines and the decrease of magnesium and ATP. Eur J Biochem 217:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poulin RP, Coward JK, Lakanen JR, Pegg AE. 1993. Enhancement of the spermidine uptake system and lethal effects of spermidine overaccumulation in ornithine decarboxylase-overproducing L1210 cells under hyposmotic stress. J Biol Chem 268:4690–4698. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53451-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuchi J, Kashiwagi K, Yamagishi M, Ishihama A, Igarashi K. 1995. Decrease in cell viability due to the accumulation of spermidine in spermidine acetyltransferase-deficient mutant of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 270:18831–18835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu WH, Morris DR. 1973. Biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase from Escherichia coli. Purification and properties. J Biol Chem 248:1687–1695. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)44245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah P, Swiatlo E. 2008. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol 68:4–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwon DS, Lin CH, Chen S, Coward JK, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM. 1997. Dissection of glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase from Escherichia coli into autonomously folding and functional synthetase and amidase domains. J Biol Chem 272:2429–2436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chattopadhyay MK, Chen W, Tabor H. 2013. Escherichia coli glutathionylspermidine synthetase/amidase: phylogeny and effect on regulation of gene expression. FEMS Microbiol Lett 338:132–140. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voet D, Voet J. 1995. Biochemistry, 2nd ed. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugiyama S, Vassylyev DG, Matsushima M, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K, Morikawa K. 1996. Crystal structure of PotD, the primary receptor of the polyamine transport system in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 271:9519–9525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugiyama S, Matsuo Y, Maenaka K, Vassylyev DG, Matsushima M, Morikawa K, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K, Morikawa K. 1996. The 1.8‐Å X‐ray structure of the Escherichia coli PotD protein complexed with spermidine and the mechanism of polyamine binding. Protein Sci 5:1984–1990. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Antognoni F, Del Duca S, Kuraishi A, Kawabe E, Fukuchi-Shimogori T, Kashiwagi K, Igarashi K. 1999. Transcriptional inhibition of the operon for the spermidine uptake system by the substrate-binding protein PotD. J Biol Chem 274:1942–1948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in‐frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. 2015. Modulation of protein synthesis by polyamines. IUBMB Life 67:160–169. doi: 10.1002/iub.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kusano T, Suzuki H. 2015. Polyamines: a universal molecular nexus for growth, survival, and specialized metabolism. Springer, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitra A, Palaniyandi S, Herren CD, Zhu X, Mukhopadhyay S. 2013. Pleiotropic roles of uvrY on biofilm formation, motility and virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. PLoS One 8:e55492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dorel C, Vidal O, Prigent-Combaret C, Vallet I, Lejeune P. 1999. Involvement of the Cpx signal transduction pathway of E. coli in biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 178:169–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma Q, Wood TK. 2009. OmpA influences Escherichia coli biofilm formation by repressing cellulose production through the CpxRA two‐component system. Environ Microbiol 11:2735–2746. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dudin O, Geiselmann J, Ogasawara H, Ishihama A, Lacour S. 2014. Repression of flagellar genes in exponential phase by CsgD and CpxR, two crucial modulators of Escherichia coli biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 196:707–715. doi: 10.1128/JB.00938-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Balzer GJ, McLean RJ. 2002. The stringent response genes relA and spoT are important for Escherichia coli biofilms under slow-growth conditions. Can J Microbiol 48:675–680. doi: 10.1139/w02-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bhardwaj N, Syal K, Chatterji D. 2018. The role of ω‐subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in stress response. Genes Cells 23:357–369. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amores GR, de Las Heras A, Sanches-Medeiros A, Elfick A, Silva-Rocha R. 2017. Systematic identification of novel regulatory interactions controlling biofilm formation in the bacterium Escherichia coli. Sci Rep 7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurihara S, Oda S, Tsuboi Y, Kim HG, Oshida M, Kumagai H, Suzuki H. 2008. γ-Glutamylputrescine synthetase in the putrescine utilization pathway of Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 283:19981–19990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Suzuki H, Kumagai H, Echigo T, Tochikura T. 1989. DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli K-12 γ-glutamyltranspeptidase gene, ggt. J Bacteriol 171:5169–5172. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5169-5172.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]