Abstract

Background and aim

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is one of the most common pathogens causing nosocomial and community-acquired infections with high morbidity and mortality rates. Fusidic acid has been increasingly used for the treatment of infections due to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). The present study aimed to determine the precise prevalence of fusidic acid resistant MRSA (FRMRSA), fusidic acid resistant MSSA (FRMSSA), and total fusidic acid resistant S. aureus (FRSA) on a global scale.

Methods

Several international databases including Medline, Embase, and the Web of Sciences were searched (2000–2020) to discern studies addressing the prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA. STATA (version14) software was used to interpret the data.

Results

Of the 1446 records identified from the databases, 215 studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria for the detection of FRSA (208 studies), FRMRSA (143 studies), and FRMSSA (71 studies). The analyses manifested that the global prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA was 0.5%, 2.6% and 6.7%, respectively.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis describes an increasing incidence of FRSA, FRMSSA, and FRMRSA. These results indicate the need for prudent prescription of fusidic acid to stop or diminish the incidence of fusidic acid resistance as well as the development of strategies for monitoring the efficacy of fusidic acid use.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13756-021-00943-6.

Keywords: Fusidic acid, Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is one of the most important causative agents in a wide range of clinical syndromes, from the skin and soft tissue infections to infective endocarditis and bacteremia as well as different prosthetic device-related infections which are reported largely worldwide [1–3]. This bacterial species can become resistant to many antibiotics, using different mechanisms. Acquisition of mobile genetic resistance elements by horizontal gene transfer, mutations of antibiotic targets, and overexpression of endogenous efflux pumps are among the most important mechanisms [4–6]. Knowing how antibiotics work and how bacteria become resistant, as well as generating accurate statistics on the rate of antibiotic resistance in different parts of the world, are important for medical management and therapeutic decisions. Furthermore, it can help in the development of practical infection control methods as well as the prevention of bacterial resistance spreading. Fusidic acid (FA) is one of the important antibacterial agents that requires ongoingevaluation of its mode of action and assessment of its resistance rate to help improve treatment strategies, particularly in the caseof staphylococcal infections. FA, derived from the fungus Fusidium coccineum (in 1960), shows moderate activity against most Gram-positive bacteria including staphylococci and also covering methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and some anaerobic Gram-negative organisms [7]. It is generally used topically for the treatment of S. aureus skin infections. Different creams and ointments containing FA are commercially available. Intravenous and oral preparations of this antibiotic are also used as anti-staphylococcal agents to treat persistent skin infections as well as chronic bone and joint infections [7, 8]. In addition, FA is an important and valuable alternative to vancomycin to combat resistant organisms [4]. FA primarily has bacteriostatic effects, although it may be bactericidal in high concentrations [9]. FA is a specific inhibitor of the elongation factor G (EF-G) which is essential in the peptide translocation step during protein synthesis. FA inhibits the GTPase function of EF-G after binding to its target and then prevents further elongation of the polypeptide chain [10]. Plasmid mediated resistance resulted from decreased bacterial cell wall or membrane permeability. Chromosomal mutations expressed in EF-G and its associated proteins (fusB, fusC, and fusD) as well as a mutation in fusA, and fusE genes have been described as relevant factors in FA resistance [11, 13] The lack of cross-resistance with other important classes of antibiotics (beta-lactams, macrolides and, aminoglycosides) is an important feature of this antibiotic which may be due to the widely different chemical structures of these agents [10]. Nonetheless, increased antibiotic usage, combined with increased therapy duration, has been linked to an increased rate of FA resistance among S. aureus isolates [12]. FA resistance rates were evaluated in 13 European countries. The results of this survey showed that the overall prevalence of resistance to FA was 10.7% among S. aureus isolates. The highest rate of resistance (62.4%) was observed among isolates from Greece [14]. Although several studies have examined the resistance FA among of S. aureus strains, a comprehensive study reporting global data is not available. So, the current study aims to evaluate the dissemination and prevalence of all FA resistant S. aureus (FRSA), and also FA resistant MRSA (FRMRSA), and FA resistant MSSA (FRMSSA), among clinical isolates in a meta-analysis and systematic review.

Methods

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of FRSA among clinical strains based on selected keywords (Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus, S. aureus, fusidic acid, sodium fusidate, and fucidin) using three main electronic databases including Medline (via PubMed), Embase, and Web of Science (2000–2020). Original articles published in English that provided the prevalence or incidence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA were selected for further analysis. We also searched the bibliographies for additional relevant articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All original papers presenting cross-sectional studies on the prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA were included. All selected studies were screened based on titles, abstracts, and full texts consecutively. Studies were included in our analysis based on the following criteria: (1) original articles that provided sufficient data on FRSA; (2) used standard methods; (A) disk diffusion method; (B) agar dilution, microdilution, and macrodilution methods or E-test; and (C) molecular methods to detect FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA according to the CLSI (2020) guidelines [15]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) articles studying non-human samples; (2) studies considering; (A) FA resistant bacteria except S. aureus; (B) other types of antibiotic resistance except FA; (3) review articles; (4) abstracts reported in conferences; and (5) duplicate article.

Data extraction and definitions

The author’s last name, date(s) of the investigation, year of publication, country/continent, total number of S. aureus, MRSA, MSSA, FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA as well as a detection method and the source of isolates were extracted from the enrolled studies. The prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA isolates was evaluated as well. Two independent researchers recorded the data to avoid bias.

Quality assessment

All evaluated studies were subjected to a quality assessment (designed by the Joanna Briggs Institute), and only high-quality ones were selected for our final analysis [16].

Meta-analysis

STATA (version 14.0) software was used to analyze the extracted data. The data were pooled using the fixed-effects model (FEM) [17] and the random-effects model (REM) [18]. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q and I2 statistical methods [19].

Results

Characteristics of included studies

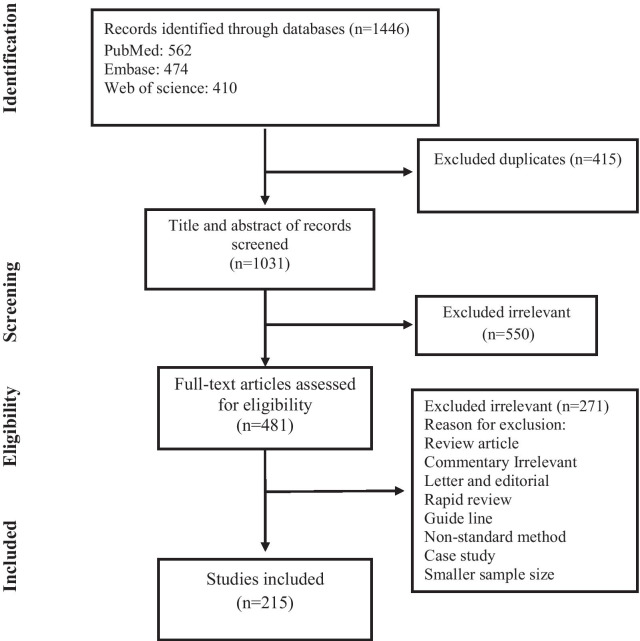

After removing duplicates, we identified a total of 1446 articles in the databases. Based on the title and abstract evaluation in secondary screening, 471 of the chosen ones were excluded (see Fig. 1 which also includes the reasons for rejection). In the next step, upon full text research, 208, 143, 71 articles were included for FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA, respectively [11, 20–233]. The characteristics of the included articles are shown in Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2, and S3.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis

The prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA among clinical isolates

The pooled and averaged prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA were 0.5 [(95% CI) 4.6–5.4] among 157,220 S. aureus isolates, 2.6 [(95% CI) 2.3–2.9] among 94,238 S. aureus isolates, 6.7 [(95% CI) 5.4–7.9] among 11,992 S. aureus isolates, respectively. Also, the pooled prevalence of FRMRSA among 50,078 MRSA isolates and FRMSSA among 70,438 MSSA isolates was 5.8 [(95% CI) 5.0–6.6] and 3.0 [(95% CI) 2.6–3.5], respectively (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1.

Prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRSSA based on study periods and continents

| Category | Subcategory | No. studies | No. strains | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRSA | ||||

| Overall | FRSA/S. aureus | 120 | 7562/157,220 | 0.5 (4.6–5.4) |

| Study period | Before 2000 | 26 | 3478/90,563 | 4.0 (3.4–4.5) |

| 2000–2009 | 55 | 2834/46,134 | 5.6 (4.9–6.2) | |

| 2010–2020 | 39 | 1250/20,523 | 5.2 (4.4–6.1) | |

| Continent | Asia | 32 | 768/11,239 | 5.6 (4.6–6.6) |

| Europe | 69 | 5519/122,267 | 4.7 (4.3–5.2) | |

| America | 9 | 408/7010 | 5.5 (3.4–7.5) | |

| Africa | 3 | 58/723 | 5.5 (0.6–10.4) | |

| Oceania | 7 | 809/15,981 | 5.0 (3.7–6.3) | |

| FRMRSA | ||||

| Overall | FRMRSA/S. aureus | 79 | 2193/94,238 | 2.6 (2.3–2.9) |

| Study period | Before 2000 | 14 | 547/39,499 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) |

| 2000–2009 | 35 | 1094/41,157 | 2.9 (2.3–3.4) | |

| 2010–2020 | 30 | 552/13,582 | 3.2(2.3–4.1) | |

| Continent | Asia | 27 | 296/7330 | 3.0 (2.1–4.0) |

| Europe | 36 | 1449/77,695 | 1.9 (1.5–2.2) | |

| America | 7 | 302/4798 | 4.3 (1.5–7.2) | |

| Africa | 6 | 111/1334 | 6.8 (3.6–9.9) | |

| Oceania | 3 | 35/3081 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| Overall | FRMRSA/MRSA | 72 | 3211/50,078 | 5.8 (5.0–6.6) |

| Study period | Before 2000 | 19 | 1410/20,768 | 5.9 (4.2–7.5) |

| 2000–2009 | 31 | 1127/20,601 | 5.0 (4.0–6.1) | |

| 2010–2020 | 22 | 674/8709 | 6.8 (5.3–8.3) | |

| Continent | Asia | 26 | 1155/11,414 | 6.4 (4.4–8.3) |

| Europe | 33 | 1637/32,906 | 1.9 (1.5–2.2) | |

| America | 7 | 295/4130 | 5.3 (3.2–7.4) | |

| Africa | 2 | 5/138 | 3.6 (0.5–6.7) | |

| Oceania | 4 | 119/1490 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| FRMSSA | ||||

| Overall | FRMSSA/S. aureus | 9 | 939/11,992 | 6.7 (5.4–7.9) |

| Study period | Before 2000 | 2 | 432/5425 | 8.0 (7.2–8.7) |

| 2000–2009 | 4 | 489/6153 | 7.1 (5.3–8.9) | |

| 2010–2020 | 3 | 18/414 | 8.0 (7.2–8.7) | |

| Continent | Asia | 2 | 9/227 | 4.0 (1.1–7.0) |

| Europe | 6 | 923/11,550 | 7.8 (6.8–8.7) | |

| America | NR | NR | NR | |

| Africa | NR | NR | NR | |

| Oceania | 1 | 7/215 | 3.3 (9.0–5.6) | |

| Overall | FRMSSA/MSSA | 42 | 2437/70,438 | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) |

| Study period | Before 2000 | 24 | 1825/57,798 | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) |

| 2000–2009 | 10 | 497/8051 | 3.8 (1.6–6.1) | |

| 2010–2020 | 8 | 115/4589 | 2.8 (1.8–3.7) | |

| Continent | Asia | 8 | 57/2845 | 1.7 (1.2–2.1) |

| Europe | 26 | 2234/62,854 | 3.1 (2.5–3.7) | |

| America | 2 | 62/2178 | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) | |

| Africa | 3 | 13/647 | 1.9 (0.3–3.5) | |

| Oceania | 3 | 71/1914 | 3.6 (2.7–4.4) | |

Table 2.

Prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRSSA based on different countries

| Category | Subcategory | No. studies | No. strains | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRSA | ||||

| Overall | FRSA/S. aureus | 120 | 7562/157,220 | 0.5 (4.6–5.4) |

| Country | Australia | 6 | 796/15,781 | 4.8 (3.4–6.2) |

| Belgium | 2 | 25/663 | 3.6 (2.2–5.0) | |

| Canada | 5 | 376/6257 | 6.3 (3.2–9.3) | |

| China | 4 | 206/2156 | 5.3 (0.6–10.0) | |

| France | 7 | 132/3120 | 5.0 (3.2–6.8) | |

| Germany | 6 | 94/2424 | 4.7 (2.8–6.6) | |

| India | 2 | 6/173 | 3.5 (0.7–6.2) | |

| Iran | 3 | 13/353 | 3.4 (1.5–5.3) | |

| Israel | 2 | 8/220 | 3.6 (1.1–6.0) | |

| Kuwait | 3 | 93/1370 | 6.8 (5.4–8.1) | |

| Malaysia | 5 | 102/1956 | 5.3 (3.6–6.9) | |

| Malta | 2 | 374/25 | 6.5 (4.0–9.1) | |

| Netherland | 2 | 63/1193 | 5.2 (4.0–6.5) | |

| Norway | 2 | 12/136 | 8.3 (3.7–12.9) | |

| Poland | 2 | 10/291 | 3.4 (1.3–5.5) | |

| Spain | 2 | 5/113 | 4.2 (0.5–8.0) | |

| Sweden | 2 | 38/616 | 5.4 (3.6–7.2) | |

| Switzerland | 2 | 18/317 | 5.6 (3.1–8.2) | |

| Taiwan | 4 | 75/1134 | 5.9 (1.9–9.9) | |

| Turkey | 9 | 223/3319 | 5.8 (3.7–7.9) | |

| UK | 22 | 4715/105,038 | 4.8 (4.1–5.5) | |

| USA | 3 | 26/653 | 3.7 (2.3–5.2) | |

| FRMRSA | ||||

| Overall | FRMRSA/S. aureus | 79 | 2193/94,238 | 2.6 (2.3–2.9) |

| Country | Australia | 2 | 33/2881 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Canada | 4 | 276/4145 | 4.5 (0.2–8.9) | |

| China | 4 | 5/295 | 1.3 (0.0–2.5) | |

| France | 3 | 33/2141 | 1.4 (0.3–2.5) | |

| Germany | 2 | 11/656 | 2.0 (0.0–4.5) | |

| Greece | 2 | 5/142 | 2.1 (0.3–3.9) | |

| Iran | 4 | 14/844 | 1.2 (0.4–1.9) | |

| Korea | 2 | 19/653 | 2.1 (0.0–5.0) | |

| Kuwait | 2 | 91/1427 | 4.5 (0.1–9.1) | |

| Malaysia | 4 | 84/1877 | 4.5 (1.9–7.2) | |

| Pakistan | 2 | 47/691 | 4.9 (0.2–12.7) | |

| Poland | 2 | 8/338 | 2.0 (0.5–3.5) | |

| Taiwan | 2 | 2/124 | 0.9 (0.0–2.1) | |

| Turkey | 7 | 77/1324 | 5.3 (2.7–7.9) | |

| UK | 10 | 1167/67,758 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | |

| USA | 3 | 26/653 | 3.7 (2.3–5.2) | |

| FRMSSA | ||||

| Overall | FRMRSA/MRSA | 72 | 3211/50,078 | 5.8 (5.0–6.6) |

| Country | Australia | 3 | 117/1470 | 7.7 (1.1–14.3) |

| Canada | 4 | 269/3477 | 6.4 (4.1–8.8) | |

| China | 3 | 4/126 | 2.9 (0.0–5.8) | |

| France | 2 | 74/1437 | 7.8 (0.0–19.0) | |

| Germany | 2 | 27/253 | 10.3 (6.5–14.0) | |

| Iran | 3 | 10/253 | 3.5 (1.2–5.7) | |

| Kuwait | 3 | 847/7002 | 9.3 (3.6–15.1) | |

| Malaysia | 4 | 84/1642 | 4.8 (3.8–5.9) | |

| Pakistan | 2 | 47/583 | 6.6 (4.6–8.6) | |

| Serbia | 2 | 6/144 | 3.6 (0.6–6.7) | |

| Taiwan | 3 | 99/716 | 8.6 (0.4–16.7) | |

| Turkey | 5 | 49/796 | 5.6 (2.7–8.6) | |

| UK | 16 | 1374/27,138 | 5.1 (4.1–6.1) | |

| USA | 3 | 26/653 | 3.7 (2.3–5.2) | |

| FRMSSA | ||||

| Overall | FRMSSA/S. aureus | 9 | 939/11,992 | 6.7 (5.4–7.9) |

| Country | UK | 4 | 906/11,265 | 8.0 (7.3–8.8) |

| Overall | FRMSSA/MSSA | 42 | 2437/70,438 | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) |

| Country | Australia | 2 | 60/1734 | 3.4 (2.6–4.3) |

| Canada | 2 | 62/2178 | 3.6 (0.6–6.6) | |

| China | 3 | 37/2203 | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | |

| Germany | 3 | 22/674 | 2.9 (1.7–4.2) | |

| Malaysia | 2 | 10/348 | 2.2 (0.0–5.1) | |

| Turkey | 4 | 10/382 | 1.8 (0.5–3.1) | |

| UK | 13 | 2184/61,050 | 3.5 (2.8–4.2) | |

The prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA in different study periods

To determine the longitudinal changes in the prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA across recent years, we designed subgroups across three periods (before 2000, 2000–2009, and 2010–2020) (Tables 1, 2). As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the incidence rate of FRSA and FRMRSA strains gradually increased from 4.0% (95% CI 3.4–4.5) of 3478/90,563 S. aureus isolates and 1.4% (95% CI 1.1–1.8) of 547/39,499 MRSA isolates before 2000 to 5.6% (95% CI 4.9–6.2) of 2834/46,134 isolates and 2.9% (95% CI 2.3–3.4) of 1094/41,157 isolates in 2000–2009, reaching 5.2% (95% CI 4.4–6.1) of 1250/20,523 S. aureus isolates and 3.2% (95% CI 2.3–4.1) of 552/13,582 MRSA isolates in 2010–2020, respectively. The changes in FRSA, and FRMRSA prevalence and also the changes in FRMSSA prevalence in all three periods are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

The prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA and FRMSSA in different regions of the world

Prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA based on geographic area in the subgroup analysis are shown in Tables 1 and 2. As can be seen, the frequency of FRSA in Asia [5.6% (95% CI 4.6–6.6)] is 1.20 and 1.12-fold higher than in Europe [4.7% (95% CI 4.3–5.2)] or Oceania [5.0% (95% CI 3.7–6.3)], respectively. The prevalence of FRSA is almost the same in Asia, America, and Africa. Also, the frequency of FRMRSA in Asia [3.0% (95% CI 2.1–4.10)] is 1.57 and 2.72-fold higher than in Europe [1.9% (95% CI 1.5–2.2)] and Oceania [1.1% (95% CI 0.8–1.5)], respectively. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of FRMRSA in Africa [6.8% (95% CI 3.6–9.9)] and America [4.3% (95% CI 1.5–7.2)] is higher than for other continents.

Discussion

The emergence of resistance to FA among S. aureus isolates has become a matter of concern in many different countries which makes it a threat to public health [153]. According to the evidence, the prevalence rate of FRSA strains differs in various geographic regions and/or patients population. In this systematic review, we noted a low prevalence of resistance to FA in 0.5% [(95% CI) 4.6–5.4] of S. aureus isolates reflecting improved infection control precautions and effectiveness of continued surveillance of S. aureus infections [14, 153, 234]. The present systematic review illustrated a higher prevalence of FRSA in Asia (5.6%) as compared to other continents. This is of serious concern reflecting inappropriate unrestricted policies and use of FA would similarly be higher in Asian countries [235, 236]. This phenomenon is related to easy access to antibiotics without prescription, paucity of suitable alternatives to FA for topical administration and cheap antibiotics, in these areas [153, 235]. Although it is difficult to recommend completely outlawing use of FA, restricted use of this antibiotic in both community and health care settings and in combination with other antibiotics is highly recommended [234, 237]. It is worth noting that the incidence rate of FRSA strains gradually increased from 4.0% before 2000 to 5.2% in 2010–2020. It seems that this increasing rate is directly linked to the increase in S. aureus infections and a shift in antibiotic pressures [14]. The present analyses exhibited a higher prevalence of FRMRSA (5.8%) compared to FRMSSA (3.0%). It is well-documented that MRSA isolates exhibited a high prevalence of multi-resistance towards antibiotics of different classes compare to MSSA strains which could limit the choices available for the control of MRSA infections. However, the use of FA outside the hospital is still not justified [236–238]. Furthermore, clinician’ and patient’ education is an important aspect promoting the appropriate use and prescription of FA together with close monitoring of antibiotic susceptibility patterns and use of this antibiotic in combination with other drugs to prevent further emergence of these strains. However, our analysis suggests that both MRSA and MSSA strains must be evaluated routinely in terms of resistance to FA. The current systematic review illustrated a high prevalence of FRMRSA in Africa (6.8%) and America (4.3%) compared to other continents. Although there is wide diversity among MRSA molecular types colonizing and infecting the population in different parts of the world, the higher relative prevalence of FRMRSA highlight the need for clinician’s awareness in administration and use of FA in community and hospital setting in Africa and America. It is well known that too many prescription guidelines are according to the outmoded data gained from observational studies of a small size. Also, it must be borne in mind that there is limited understanding of FA resistance at the epidemiological, clinical, and genetic level [239–241]. Moreover, infection control efforts as a main framework and strategy are crucial to decline the emergence and prevalence of FRMRSA strains [14, 237, 240]. One potential explanation for the higher prevalence of FRMRSA in America (4.3%) could be related to phenotypic methods used and breakpoint values applied for the screening and detection of FRMRSA. There were some drawbacks in the current review. Only published scientific studies were considered for the present meta-analysis and potential publication bias had to be considered. Secondly, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA in all countries. Since many countries had no record of the prevalence of these strains, we were not able to reach this goal. The prevalence of rampant bacteria in patients with S. aureus infection disease is not well established in many countries. So, the prevalence of these FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA in patients with S. aureus infection should be investigated in every country to gather comprehensive information.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis depicted trends towards an increasing incidence of FRSA, FRMSSA, and FRMRSA. The findings highlight the need for the implementation of (ongoing) surveillance, antibiotic stewardship measures to mitigate the emergence and spread of FRSA, gathering epidemiological data to understand the peculiarities of the epidemiology, medical burden and risk factors related to FRSA, harmonized guidelines for infection control, education of clinicians on the proper prescribing of FA, and development of strategies for monitoring the effects of FA use.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Tables S1–S3. Characteristics of included studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ali Hashemi, Department of Microbiology at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for his sincere assistance and efforts to make this project happen.

Authors' contributions

MD and BH, designed the study. BH and HG conducted the search strategy. BH, SK, SA and SZ performed the data extraction. MD, BH and MG, wrote and edited the manuscript. MD carried out the statistical analysis. MD, HG and AVB assumed overall responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by grant 4008 from the Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

Not required.

Competing interests

AVB is an employee of bioMérieux, a French company developing diagnostic tools for infectious diseases. The company has had no influence on the design and execution of the current study. No competing interests apply for the other authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mehdi Goudarzi: co-first author

References

- 1.Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Pathogenesis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):S350–S359. doi: 10.1086/533591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armin S, Fareghi F, Fallah F, Dadashi M, Nikmanesh B, Ghalavand Z. Prevalence of hlg and pvl genes in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from health care staff in Mofid Children Hospital, Tehran. Iran J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2015;9(2):1001–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Razavi S, Dadashi M, Pormohammad A, Khoramrooz SS, Mirzaii M, Gholipour A, et al. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus epidermidis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2018;13(4):e58410. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster TJ. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41(3):430–449. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadashi M, Hajikhani B, Darban-Sarokhalil D, van Belkum A, Goudarzi M. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;20:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasani A, Purmohammad A, Rezaee MA, Hasani A, Dadashi M. Integron-mediated multidrug and quinolone resistance in extended-spectrum βlactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. 2017;5:e36616.

- 7.Wu P-P, He H, Hong WD, Wu T-R, Huang G-Y, Zhong Y-Y, et al. The biological evaluation of fusidic acid and its hydrogenation derivative as antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:1945s. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S176390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turnidge J. Fusidic acid pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12(Suppl 2):S23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson JD. Fusidic acid in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(Suppl 53):37–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s3037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curbete MM, Salgado HR. A critical review of the properties of fusidic acid and analytical methods for its determination. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2016;46(4):352–360. doi: 10.1080/10408347.2015.1084225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neill AJ, Chopra I. Molecular basis of fusB-mediated resistance to fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59(2):664–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaws FB, Larsen AR, Skov RL, Chopra I, O'Neill AJ. Distribution of fusidic acid resistance determinants in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):1173–1176. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00817-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neill AJ, McLaws F, Kahlmeter G, Henriksen AS, Chopra I. Genetic basis of resistance to fusidic acid in staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(5):1737–1740. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01542-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castanheira M, Watters AA, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and molecular characterization of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. from European countries (2008) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(7):1353–1358. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne P. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020.

- 16.Institute TJB. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual. 2014. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rohani MY, Raudzah A, Lau MG, Zaidatul AAR, Salbiah MN, Keah KC, et al. Susceptibility pattern of Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Malaysian hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;13(3):209–213. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiśniewska K, Piechowicz L, Galiński J. Predominance of multidrug resistant strains with reduced susceptibility to fusidic acid among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains (MRSA) isolated in the Gdánsk region. Polski merkuriusz lekarski: organ Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego. 2000;9(53):746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atmaca S, Özekinci T, Özerdem N. Fusidic acid susceptibilities of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2001;35(1):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belabbes H, Elmdaghri N, Hachimi K, Marih L, Zerouali K, Benbachir M. Antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from community and nosocomial infections in Casablanca. Med Maladies Infect. 2001;31(1):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosbell IB, Mercer JL, Neville SA, Chant KG, Munro R. Community-acquired, non-multiresistant oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (NORSA) in South Western Sydney. Pathology. 2001;33(2):206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quentin C, Grobost F, Fischer I, Dutilh B, Brochet JP, Jullin J, et al. Antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus in extra-hospital practice: a six-month period study in aquitaine. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0369-8114(00)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer F, Bruttin O, Zografos L, Guex-Crosier Y. Bacterial keratitis: a prospective clinical and microbiological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(7):842–847. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tunger O, Arisoy A, Kurutepe S, Akcali S, Ozbakkaloglu B. In vitro susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus strains to fusidic acid. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18(5):445–447. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arkwright PD, Daniel TO, Sanyal D, David TJ, Patel L. Age-related prevalence and antibiotic resistance of pathogenic staphylococci and streptococci in children with infected atopic dermatitis at a single-specialty center. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(7):939–941. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown EM, Thomas P. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet (London, England) 2002;359(9308):803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07869-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang JH, Chu CK, Liu TC. Changes in bacteriology of discharging ears. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(9):686–689. doi: 10.1258/002221502760237957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang JH, Tsai HY, Liu TC. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in discharging ears. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(8):827–830. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000028076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livermore D, James D, Duckworth G, Stephens P. Fusidic-acid use and resistance. Lancet (London, England) 2002;360(9335):806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09921-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memikoǧlu KO, Bayar B, Kurt Ö, Çokça F. In-vitro susceptibility of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus to fusidic acid and trimethoprim—Sulfamethoxazole. Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2002;36(2):141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishijima S, Kurokawa I. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from skin infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19(3):241–243. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norazah A, Lim VKE, Koh YT, Rohani MY, Zuridah H, Spencer K, et al. Molecular fingerprinting of fusidic acid- and rifampicin-resistant strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from Malaysian hospitals. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51(12):1113–1116. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-12-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterlund A, Eden T, Olsson-Liljequist B, Haeggman S, Kahlmeter G, Swedish Study Grp Fusid A-R Clonal spread among Swedish children of a Staphylococcus aureus strain resistant to fusidic acid. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(10):729–734. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sule O, Brown N, Brown DFJ, Burrows N. Fusidic acid cream for impetigo—Judicious use is advisable. BMJ. 2002;324(7350):1394–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiśniewska K, Dajnowska-Stanczewa A, Galiński J, Garbacz K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with high resistance to mupirocin in hospitals of the Gdańsk region. Medycyna doświadczalna i mikrobiologia. 2002;54(4):285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grohs P, Kitzis MD, Gutmann L. In vitro bactericidal activities of linezolid in combination with vancomycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, fusidic acid, and rifampin against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(1):418–420. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.418-420.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kesah C, Ben Redjeb S, Odugbemi TO, Boye CS, Dosso M, Ndinya Achola JO, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in eight African hospitals and Malta. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(2):153–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorette G, Beaulieu P, Bismuth R, Duru G, Guihard W, Lemaitre M, et al. Community-acquired cutaneous infections: causal role of some bacteria and sensitivity to antibiotics. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(8–9 I):723–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norazah A, Lim VK, Munirah SN, Kamel AG. Staphylococcus aureus carriage in selected communities and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns. Med J Malays. 2003;58(2):255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rørtveit S, Rørtveit G. An epidemic of bullous impetigo in an island community in Norway in the year 2002. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2003;123(18):2557–2560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah M, Mohanraj M. High levels of fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1018–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tveten Y, Jenkins A, Allum AG, Kristiansen BE, Norwegian MSG. Heterogeneity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Norway. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(8):886–892. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akpabie A, Naga H, Giraud K, Al Rahiss R, Nadai S. Resistance to linezolid in Staphylococcus aureus before its release. Parodontol. 2004;52(8):493–496. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cartolano GL, Cheron M, Benabid D, Leneveu M, Boisivon A, Marchal MF, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides (GISA) in 63 French general hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(5):448–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Zimaity D, Kearns AM, Dawson SJ, Price S, Harrison GAJ. Survey, characterization and susceptibility to fusidic acid of Staphylococcus aureus in the Carmarthen area. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54(2):441–446. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erdenizmenli M, Yapar N, Sengonul A, Yuce A, Cakir N, Yulug N. In-vitro activity of fusidic acid against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of chemotherapy (Florence, Italy) 2004;16(3):310–311. doi: 10.1179/joc.2004.16.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoeger PH. Antimicrobial susceptibility of skin-colonizing S. aureus strains in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15(5):474–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lescat M, Dupeyron C, Faubert E, Mangeney N. Pulse-field gel electrophoresis typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains susceptible to aminoglycosides isolated from 1993 to 2002. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57(3):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindberg E, Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus colonising the intestines of Swedish infants. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(10):890–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrissey I, Burnett R, Viljoen L, Robbins M. Surveillance of the susceptibility of ocular bacterial pathogens to the fluoroquinolone gatifloxacin and other antimicrobials in Europe during 2001/2002. J Infect. 2004;49(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seydi M, Sow AI, Soumaré M, Diallo HM, Hatim B, Tine R, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in the Dakar Fann university hospital. Med Maladies Infect. 2004;34(5):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zinn CS, Westh H, Rosdahl VT. An international multicenter study of antimicrobial resistance and typing of hospital Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 21 laboratories in 19 countries or states. Microb Drug Resist. 2004;10(2):160–168. doi: 10.1089/1076629041310055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Sweih N, Mokaddas E, Jamal W, Phillips OA, Rotimi VO. In vitro activity of linezolid and other antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria from the major teaching hospitals in Kuwait. Journal of chemotherapy (Florence, Italy) 2005;17(6):607–613. doi: 10.1179/joc.2005.17.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Denis O, Deplano A, De Beenhouwer H, Hallin M, Huysmans G, Garrino MG, et al. Polyclonal emergence and importation of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains harbouring Panton-Valentine leucocidin genes in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(6):1103–1106. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilani SJK, Gonzalez M, Hussain I, Finlay AY, Patel GK. Staphylococcus aureus re-colonization in atopic dermatitis: beyond the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):10–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Norazah A, Lim VK, Rohani MY, Kamel AG. In-vitro activity of quinupristin/dalfopristin, levofloxacin and moxifloxacin against fusidic acid and rifampicin-resistant strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from Malaysian hospitals. Med J Malays. 2005;60(4):411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samra Z, Ofer O, Shmuely H. Susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, pristinamycin and other antibiotics. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7(3):148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vourli S, Perimeni D, Makri A, Polemis M, Voyiatzi A, Vatopoulos A. Community acquired MRSA infections in a paediatric population in Greece. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2005;10(5):78–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kareiviene V, Pavilonis A, Sinkute G, Liegiute S, Gailiene G. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to antibiotics and spread of phage types. Medicina (Kaunas) 2006;42(4):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim MS, Chung BS, Choi KC. A study of antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus in bacterial skin infections. Korean J Dermatol. 2006;44(7):805–810. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koning S, Mohammedamin RSA, Van Der Wouden JC, Van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Schellevis FG, Thomas S. Impetigo: Incidence and treatment in Dutch general practice in 1987 and 2001—results from two national surveys. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(2):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rennie RP. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to fusidic acid: Canadian data. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10(6):277–280. doi: 10.2310/7750.2006.00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saginur R, Stdenis M, Ferris W, Aaron SD, Chan F, Lee C, et al. Multiple combination bactericidal testing of staphylococcal biofilms from implant-associated infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(1):55–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.1.55-61.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stevens CL, Ralph A, McLeod JE, McDonald MI. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Central Australia. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2006;30(4):462–466. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2006.30.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N, Mohanakrishnan S, West PW. Antibacterial resistance and molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Kuwaiti general hospital. Med Princip Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Centre. 2006;15(1):39–45. doi: 10.1159/000089384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N, Mokaddas E, Johny M, Dhar R, Gomaa HH, et al. Antibacterial resistance and their genetic location in MRSA isolated in Kuwait hospitals, 1994–2004. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abdallah M, Zaki SM, El-Sayed A, Erfan D. Evaluation of secondary bacterial infection of skin diseases in Egyptian in-and out-patients and their sensitivity to antimicrobials. Egypt Dermatol Online J. 2007;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jorgen B, Merckoll P, Melby KK. Susceptibility to daptomycin, quinupristin-dalfopristin and linezolid and some other antibiotics in clinical isolates of methicillin resistant and methicillin sensitive S. aureus from the Oslo area. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39(11–12):1059–1062. doi: 10.1080/00365540701466231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perwaiz S, Barakzi Q, Farooqi BJ, Khursheed N, Sabir N. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Randrianirina F, Soares JL, Ratsima E, Carod JF, Combe P, Grosjean P, et al. In vitro activities of 18 antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the Institut Pasteur of Madagascar. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2007;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bernard P, Jarlier V, Santerre-Henriksen A. Antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus strains responsible for cutaneous infections in the community. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cercenado E, Cuevas O, Marin M, Bouza E, Trincado P, Boquete T, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Madrid, Spain: transcontinental importation and polyclonal emergence of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;61(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denton M, O'Connell B, Bernard P, Jarlier V, Williams Z, Henriksen AS. The EPISA study: antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus causing primary or secondary skin and soft tissue infections in the community in France, the UK and Ireland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(3):586–588. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gubbay JB, Gosbell IB, Barbagiannakos T, Vickery AM, Mercer JL, Watson M. Clinical features, epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance, and exotoxin genes (including that of Panton-Valentine leukocidin) of gentamicin-susceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (GS-MRSA) isolated at a paediatric teaching hospital in New South Wales, Australia. Pathology. 2008;40(1):64–71. doi: 10.1080/00313020701716276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jappe U, Heuck D, Strommenger B, Wendt C, Werner G, Altmann D, et al. Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology outpatients with special emphasis on community-associated methicillin-resistant strains. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(11):2655–2664. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kedzierska A, Kapinska-Mrowiecka M, Czubak-Macugowska M, Wojcik K, Kedzierska J. Susceptibility testing and resistance phenotype detection in Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients with atopic dermatitis, with apparent and recurrent skin colonization. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(6):1290–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Larsen AR, Bocher S, Stegger A, Goering R, Pallesen LV, Skov R. Epidemiology of European community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV strains isolated in Denmark from 1993 to 2004. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(1):62–68. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01381-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Niebuhr M, Mai U, Kapp A, Werfel T. Antibiotic treatment of cutaneous infections with Staphylococcus aureus in patients with atopic dermatitis: current antimicrobial resistances and susceptibilities. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17(11):953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N, Dhar R, Dimitrov TS, Mokaddas EM, Johny M, et al. Surveillance of antibacterial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Kuwaiti hospitals. Med Princip Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Centre. 2008;17(1):71–75. doi: 10.1159/000109594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Udo EE, Panigrahi D, Jamsheer AE. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in a Bahrain hospital. Med Princip Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Centre. 2008;17(4):308–314. doi: 10.1159/000129611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Woodford N, Afzal-Shah M, Warner M, Livermore DM. In vitro activity of retapamulin against Staphylococcus aureus isolates resistant to fusidic acid and mupirocin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(4):766–768. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bauer CC, Apfalter P, Daxboeck F, Bachhofner N, Stadler M, Blacky A, et al. Prevalence of panton-valentine leukocidin genes in methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus isolates phenotypically consistent with community-acquired MRSA, 1999–2007, vienna general hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28(8):909–912. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brosnikoff C, Rennie R, Kidson P, Yamamura D, Bechard C, Kelly M, et al. Surveillance of staphylococcus aureus susceptibility to fusidic acid in five Canadian laboratories. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:S43. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Claesson C, Nilsson LE, Kronvall G, Walder M, Sorberg M. Antimicrobial activity of tigecycline and comparative agents against clinical isolates of staphylococci and enterococci from ICUs and general hospital wards at three Swedish university hospitals. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41(3):171–181. doi: 10.1080/00365540902721368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Idrees F, Jabeen K, Khan MS, Zafar A. Antimicrobial resistance profile of methicillin resistant Staphylococcal aureus from skin and soft tissue isolates. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59(5):266–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim SM, Lee DC, Park SD, Kim BS, Kim JK, Choi MR, et al. Genotype, coagulase type and antimicrobial susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from dermatology patients and healthy individuals in Korea. J Bacteriol Virol. 2009;39(4):307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laurent F, Tristan A, Croze M, Bes M, Meugnier H, Lina G, et al. Presence of the epidemic European fusidic acid-resistant impetigo clone (EEFIC) of Staphylococcus aureus in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(2):420–421. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mitra A, Mohanraj M, Shah M. High levels of fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus despite restrictions on antibiotic use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(2):136–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nickerson EK, Hongsuwan M, Limmathurotsakul D, Wuthiekanun V, Shah KR, Srisomang P, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in a tropical setting: patient outcome and impact of antibiotic resistance. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(1):e4308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scangarella-Oman NE, Shawar RM, Bouchillon S, Hoban D. Microbiological profile of a new topical antibacterial: retapamulin ointment 1% Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7(3):269–279. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scicluna EA, Shore A, Thürmer A, Slickers P, Ehricht R, Borg MA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of MRSA in Malta and the description of a Maltese epidemic MRSA strain. Int J Med Microbiol. 2009;299:40–41. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0834-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uluǧ M, Ayaz C, Çelen MK. The importance of fusidic acid in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. Anatol J Clin Investig. 2009;3(4):222–226. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Willey B, Gnanasuntharam P, Rostas A, Porter V, Kreiswirth N, Louie L, et al. Molecular diversity of community-acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) in Toronto. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:S110–S111. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alsterholm M, Flytstrom I, Bergbrant IM, Faergemann J. Fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in impetigo contagiosa and secondarily infected atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(1):52–57. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Castanheira M, Farrell D, Janechek M, Jones R. CEM-102 (fusidic acid) in vitro activity and evaluation of molecular resistance mechanisms among European Gram-positive isolates, 2008–2009. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:S247–S248. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Castanheira M, Watters AA, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Jones RN. Fusidic acid resistance rates and prevalence of resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. isolated in North America and Australia, 2007–2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3614–3617. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01390-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen HJ, Hung WC, Tseng SP, Tsai JC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. Fusidic acid resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(12):4985–4991. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00523-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cirkovic I, Svabic Vlahovic M, Stepanovic S. Molecular characterization of Panton-Valentine leukocidin positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Serbia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:S278. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Elazhari M, Zerouali K, Dersi N, Saile R, Timinouni M, Hassar M. Variability of fusidic acid-resistant methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Casablanca. Morocco Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:S281. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jones RN, Castanheira M, Rhomberg PR, Woosley LN, Pfaller MA. Performance of fusidic acid (CEM-102) susceptibility testing reagents: Broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and Etest methods as applied to Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(3):972–976. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01829-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Sader HS, Jones RN. Evaluation of the activity of fusidic acid tested against contemporary Gram-positive clinical isolates from the USA and Canada. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35(3):282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rijnders M, Nys S, Driessen C, Hoebe CJ, Hopstaken RM, Oudhuis GJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus carriage among GPs in The Netherlands. Br J Gen Pract J R Coll Gen Pract. 2010;60(581):902–906. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X544078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Udo E, Sarkhoo E. The expansion of ST80-SCCmec-IV clone of communityacquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Kuwait hospitals. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e345–e346. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Udo EE, Sarkhoo E. The dissemination of ST80-SCCmec-IV community-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Kuwait hospitals. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yeung CK, Chow WC, Chan HHL, Ho PL. Carriage of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis children attending paediatric outpatient clinics, Hong Kong. J Dermatol Venereol. 2010;18(3):125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Alreshidi MA, Mariana NS. Increasing rate of detection of fusidic acid resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples in Malaysia. Med J Malays. 2011;66(3):276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Anastasiou E, Farmaki EE, Pertsas E, Kakasi E, Koteli A. In vitro activity of fusidic acid against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:S18. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Champion EA, Popowitch E, Miller M, Saiman L, Muhlebach M. MRSA: epidemiology, molecular typing and antimicrobial susceptibilities: multicenter STAR-CF study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(1):A6120. (in English)

- 112.Chang CH, Lin TC, Chang CH, Hong SJ, Tsai YC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in skin and soft tissue infections and minocyclin treatment experience in the dermatological setting of eastern Taiwan. Dermatol Sin. 2011;29(3):86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen CM, Huang M, Chen HF, Ke SC, Li CR, Wang JH, et al. Fusidic acid resistance among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Taiwanese hospital. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jones RN, Mendes RE, Sader HS, Castanheira M. In vitro antimicrobial findings for fusidic acid tested against contemporary (2008–2009) gram-positive organisms collected in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 7):S477–S486. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lemaire S, Piérard D, Van Bambeke F, Tulkens P. Intracellular activity of fusidic acid against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus of increasing MIC. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:S182–S183. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rørtveit S, Skutlaberg DH, Langeland N, Rortveit G. Impetigo in a population over 8.5 years: incidence, fusidic acid resistance and molecular characteristics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(6):1360–1364. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Titov L, Ermakova T, Gorbunov V, Lebedev F, Kazakov I, Glazkova S. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci in the Republic of Belarus: results of the National Surveillance System (2008–2010) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:S198–S199. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Baek YS, Song HJ. Fusidic acid and mupirocin resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from infected skin wounds of Korean patients. J Dermatol. 2012;39:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Berktold M, Grif K, Maser M, Witte W, Wurzner R, Orth-Holler D. Genetic characterization of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(19–20):709–715. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen X, Yang HH, Huangfu YC, Wang WK, Liu Y, Ni YX, et al. Molecular epidemiologic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from four burn centers. Burns. 2012;38(5):738–742. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Demir T, Coplu N, Bayrak H, Turan M, Buyukguclu T, Aksu N, et al. Panton-Valentine leucocidin gene carriage among Staphylococcus aureus strains recovered from skin and soft tissue infections in Turkey. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(4):837–840. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Groome MJ, Albrich WC, Wadula J, Khoosal M, Madhi SA. Community-onset Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in hospitalised African children: high incidence in HIV-infected children and high prevalence of multidrug resistance. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2012;32(3):140–146. doi: 10.1179/1465328111Y.0000000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Horner C, Kearns A, Heritage J, Wilcox M. The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in elderly residents of 65 care homes in a single primary care trust of northern England. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:341. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ibrahim N, Siti-Fairuz MH, Nurul-Iwani MAA. A survey on community acquired-meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus burden among university students. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e223. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kunsang Bhutia O, Singh TSK. Occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of community and hospital associated methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus strains in Sikkim. J Int Med Sci Acad. 2012;25(4):235–237. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nagarajan A, Arunkumar K, Saravanan M, Sivakumar G, Krishnan P. Detection of fusidic acid resistance determinants among Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing skin and soft tissue infections from a tertiary care centre in Chennai, South India. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:1. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nergiz Ş, Atmaca S, Özekinci T, Tekin A. Fusidic acid resistance in staphylococcus aureus strains in an interval of ten years (2001–2011) Turk Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2012;32(6):1668–1672. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pichon B, Hill RLR, Blackburn R, Ganner M, Harwin L, Cookson B, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in the UK-2011. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:36. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Rashid Z, Sattar A, Qureshi MIM, Farzana K, Rashid F, Murtaza G. Nasal carriage of staphylococci in medical personnel, sanitary workers and non-medical personnel. Lat Am J Pharm. 2012;31(10):1496–1500. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sasirekha B, Usha MS, Amruta AJ, Ankit S, Brinda N, Divya R. Evaluation and comparison of different phenotypic tests to detect Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and their biofilm production. Int J PharmTech Res. 2012;4(2):532–541. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Shore AC, Brennan OM, Deasy EC, Rossney AS, Kinnevey PM, Ehricht R, et al. DNA microarray profiling of a diverse collection of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates assigns the majority to the correct sequence type and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type and results in the subsequent identification and characterization of novel SCCmec-SCCM1 composite islands. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(10):5340–5355. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01247-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Somily AM, Peaper DR, Paintsil E, Murray TS. Comparison of disk diffusion and Etest methods to determine the susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus circulating in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia to fusidic acid. Int J Microbiol. 2012;2012:391251. doi: 10.1155/2012/391251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Strandén A, Frei R, Widmer AF. Lack of emergence of PVL-positive MRSA strains in a university hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:339. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Udo E, Al-sweih N. Emergence and characterisation of community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a neonatal special care unit. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e387. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ben Nejma M, Mastouri M, Bel Hadj Jrad B, Nour M. Characterization of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Tunisia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77(1):20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Champion MD, Gray V, Eberhard C, Kumar S. The evolutionary history of amino acid variations mediating increased resistance of S. aureus identifies reversion mutations in metabolic regulators. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chuamuangphan T, Chongtrakool P, Sungkanuparph S. Predicting factors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia among hospitalized patients in a tertiary-care hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;42:S147. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Coombs GW, Nimmo GR, Pearson JC, Collignon PJ, Bell JM, McLaws ML, et al. Australian group on antimicrobial resistance hospital-onset Staphylococcus aureus Surveillance Programme annual report, 2011. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2013;37(3):E210–E218. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2013.37.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dinić M, Vuković S, Kocić B, Dordević DS, Bogdanović M. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in healthy adults and in school children. Acta Facultatis Medicae Naissensis. 2013;30(1):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Egyir B, Guardabassi L, Nielsen SS, Larsen J, Addo KK, Newman MJ, et al. Prevalence of nasal carriage and diversity of Staphylococcus aureus among inpatients and hospital staff at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital. Ghana J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2013;1(4):189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hasani A, Sheikhalizadeh V, Hasani A, Naghili B, Valizadeh V, Nikoonijad AR. Methicillin resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: appraising therapeutic approaches in the Northwest of Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5(1):56–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Heng YK, Tan KT, Sen P, Chow A, Leo YS, Lye DC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and topical fusidic acid use: results of a clinical audit on antimicrobial resistance. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(7):876–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Huang YC, Su LH, Lin TY. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among pediatricians in Taiwan. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e82472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lim KT, Abu Hanifah Y, Yusof MYM, Ito T, Thong KL. Comparison of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in 2003 and 2008 with an emergence of multidrug resistant ST22: SCCmec IV clone in a tertiary hospital, Malaysia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46(3):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sahm DF, Deane J, Pillar CM, Fernandes P. In vitro activity of CEM-102 (fusidic acid) against prevalent clones and resistant phenotypes of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(9):4535–4536. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00206-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Scerri J, Monecke S, Borg MA. Prevalence and characteristics of community carriage of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in malta. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2013;3(3):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Sun M, Wang L, Liu Y, Li X, Sun J, Wang C, et al. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial resistance of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from children with skin and soft tissue infections. Chin J Infect Chemother. 2013;13(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Treesirichod A, Hantagool S, Prommalikit O. Nasal carriage and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus among medical students at the HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Medical Center, Thailand: a cross sectional study. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(3):196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Tuncer Ertem G, Öztürk B, Ataman HatIpoǧlu C, Ipekkan K, Erdem F, Adiloǧlu AK, et al. In vitro susceptibilities of staphylococcus and enterococcus isolates to linezolid, daptomycin, teicoplanin and fusidic acid. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2013;33(6):1381–1387. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Maternity Hospital, Kuwait. Med Princip Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Centre. 2013;22:535–539. doi: 10.1159/000350526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Ahmad B, Khan F, Ahmed J, Cha SB, Shin MK, Bashir S, et al. Antibiotic resistance pattern and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in burns unit of a tertiary care hospital in Peshawar, Pakistan. Trop J Pharma Res. 2014;13(12):2091–2099. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Akinkunmi EO, Adesunkanmi AR, Lamikanra A. Pattern of pathogens from surgical wound infections in a Nigerian hospital and their antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(4):802–809. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.den Heijer CD, van Bijnen EM, Paget WJ, Stobberingh EE. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage strains in nine European countries. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(6):737–745. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Gordon NC, Price JR, Cole K, Everitt R, Morgan M, Finney J, et al. Prediction of Staphylococcus aureus antimicrobial resistance by whole-genome sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(4):1182–1191. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Harastani HH, Tokajian ST. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV (CC80-MRSA-IV) isolated from the Middle East: a heterogeneous expanding clonal lineage. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Li J, Wang Q, Wang L, Sun M, Li S, Sun J, et al. Multidrug-resistant clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children with community-associated pneumonia. Chin J Infect Chemother. 2014;14(1):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Rortveit S, Skutlaberg DH, Langeland N, Rortveit G. The decline of the impetigo epidemic caused by the epidemic European fusidic acid-resistant impetigo clone: an 11.5-year population-based incidence study from a community in Western Norway. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(12):832–837. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.947317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sǎndulescu O, Grigoraş A, Streinu-Cercel A, Berciu I, Neguţ AC, Streinu-Cercel A. Resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients treated in a tertiary care hospital in Romania. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(7):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sfeir M, Obeid Y, Eid C, Saliby M, Farra A, Farhat H, et al. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant nasal and pharyngeal colonization in outpatients in Lebanon. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(2):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Udo EE, Al-Lawati BAH, Al-Muharmi Z, Thukral SS. Genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Oman reveals the dominance of Panton-Valentine leucocidin-negative ST6-IV/t304 clone. New Microbes New Infect. 2014;2(4):100–105. doi: 10.1002/nmi2.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Vindel A, Trincado P, Cuevas O, Ballesteros C, Bouza E, Cercenado E. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Spain: 2004–12. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(11):2913–2919. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wasserman E, Orth H, Senekal M, Harvey K. High prevalence of mupirocin resistance associated with resistance to other antimicrobial agents in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients in private health care, Western Cape. Southern Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2014;29(4):126–132. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Yildiz T, Çoban AY, Şener AG, Coşkuner SA, Bayramoğlu G, Güdücüoğlu H, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance mechanisms of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from 12 Hospitals in Turkey. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Al-Talib H, Al-Khateeb A, Hassan H. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Malaysian tertiary hospital. Int Med J. 2015;22(2):73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 165.Aqel AA, Alzoubi HM, Vickers A, Pichon B, Kearns AM. Molecular epidemiology of nasal isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Jordan. J Infect Public Health. 2015;8(1):90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Bari F, Wazir R, Haroon M, Ali S, Imtiaz RH, et al. Frequency and antibiotic susceptibility profile of MRSA at lady reading hospital, Peshawar. Gomal J Med Sci. 2015;13(1):62–65. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Decousser JW, Desroches M, Bourgeois-Nicolaos N, Potier J, Jehl F, Lina G, et al. Susceptibility trends including emergence of linezolid resistance among coagulase-negative staphylococci and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from invasive infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(6):622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Ellington MJ, Reuter S, Harris SR, Holden MTG, Cartwright EJ, Greaves D, et al. Emergent and evolving antimicrobial resistance cassettes in community-associated fusidic acid and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45(5):477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Park SH, Kim JK, Park K. In vitro antimicrobial activities of fusidic acid and retapamulin against mupirocin- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(5):551–556. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Salah LA, Faergemann J. A retrospective analysis of skin bacterial colonisation, susceptibility and resistance in atopic dermatitis and impetigo patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(5):532–535. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Vallières E, Rendall JC, Moore JE, McCaughan J, Tunney MM, Elborn JS, et al. MRSA eradication in CF patients with lower respiratory tract infection. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14:S83. [Google Scholar]

- 172.Wang WY, Chiueh TS, Lee YT, Tsao SM. Correlation of molecular types with antimicrobial susceptibility profiles among 670 meca-positive MRSA isolates from sterile sites (tist study, 2006–2010) J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015;48(2):S39. [Google Scholar]

- 173.Yu FY, Liu YL, Lu CH, Lv JN, Qi XQ, Ding Y, et al. Dissemination of fusidic acid resistance among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0552-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Baek YS, Jeon J, Ahn JW, Song HJ. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from skin infections and its implications in various clinical conditions in Korea. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(4):e191–e197. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Bessa GR, Machado DC, Weber MB, D’Azevedo PA, Quinto VP, Lipnharski C, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to topical antimicrobials in atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5):604–610. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Bhattacharya S, Pal K, Jain S, Chatterjee SS, Konar J. Surgical site infection by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus-on decline. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(9):DC32–DC36. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21664.8587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Bierowiec K, Ploneczka-Janeczko K, Rypula K. Is the colonisation of Staphylococcus aureus in pets associated with their close contact with owners? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0156052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Boswihi SS, Udo EE, Al-Sweih N. Shifts in the clonal distribution of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in Kuwait hospitals: 1992–2010. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0162744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Budimir A, Tićac B, Rukavina T, Farkaš M, Kalenić S. First report on PVL-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of SCCmec type V, spa type T441 in Croatia. Coll Antropol. 2016;40(2):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Cabrera A, Golding G, Campbell J, Pelude L, Bryce E, Frenette C, et al. Characterization of clinical methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from Canadian hospitals, 2010–2015. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:1746. [Google Scholar]

- 181.Farrell DJ, Mendes RE, Castanheira M, Jones RN. Activity of fusidic acid tested against staphylococci isolated from patients in U.S. Medical Centers in 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(6):3827–3831. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00238-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Flamm RK, Rhomberg PR, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. In vitro spectrum of pexiganan activity; bactericidal action and resistance selection tested against pathogens with elevated MIC values to topical agents. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;86(1):66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Harkins CP, McAleer MA, Fleury OM, Bennett D, Foster TJ, McLean WHI, et al. Staphylococcus aureus associated with atopic eczema flares: case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(5):e43. [Google Scholar]

- 184.Klein S, Nurjadi D, Eigenbrod T, Bode KA. Evaluation of antibiotic resistance to orally administrable antibiotics in staphylococcal bone and joint infections in one of the largest university hospitals in Germany: is there a role for fusidic acid? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47(2):155–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Liu Y, Xu Z, Yang Z, Sun J, Ma L. Characterization of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections: a multicenter study in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5(12):e127. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Mehdi SZ, Akber JUD, Nizam M, Dawood K, Buksh AR. Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of microorganisms isolated from hospitalized infantile burn cases in a tertiary care hospital. Pak Paediatr J. 2016;40(3):135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 187.Nawaz A, Razzaq A, Ijaz S, Nawaz A, Ali A, Kaleem A. Characterization of antibiotic resistant gene in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from surgical wounds. Adv Life Sci. 2016;3(3):83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 188.Park JM, Jo JH, Jin H, Ko HC, Kim MB, Kim JM, et al. Change in antimicrobial susceptibility of skin-colonizing Staphylococcus aureus in Korean patients with atopic dermatitis during ten-year period. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(4):470–478. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Rahimi F, Shokoohizadeh L. Characterization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among inpatients and outpatients in a referral hospital in Tehran, Iran. Microb Pathog. 2016;97:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Sarkar A, Raji A, Garaween G, Soge O, Rey-Ladino J, Al-Kattan W, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence markers in methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with nasal colonization. Microb Pathog. 2016;93:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Shahmohammadi MR, Nahaei MR, Akbarzadeh A, Milani M. Clinical test to detect mecA and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus, based on novel biotechnological methods. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44(6):1464–1468. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2015.1041639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Souli M, Karaiskos I, Galani L, Maraki S, Perivolioti E, Argyropoulou A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of resistance rates of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates from Greek hospitals, 2012–2013. Infect Dis. 2016;48(4):287–292. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2015.1110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Abouelfetouh A, Kassem M, Naguib M, El-Nakeeb M. Investigation and treatment of fusidic acid resistance among methicillin-resistant staphylococcal isolates from Egypt. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23(1):8–17. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2015.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Aktas G, Derbentli S. In vitro activity of daptomycin combinations with rifampicin, gentamicin, fosfomycin and fusidic acid against MRSA strains. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;10:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Al Balawi I, Amirthalingam P, Alyoussef AAK, Mohammed OS, Mirghani HO, Ezzat AA. Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from the isolated wound culture in the northwest region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2017;9(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 196.Błazewicz I, Jaśkiewicz M, Bauer M, Piechowicz L, Nowicki RJ, Kamysz W, et al. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with atopic dermatitis: a reason for increasing resistance to antibiotics? Postepy Dermatologii i Alergologii. 2017;34(6):553–560. doi: 10.5114/ada.2017.72461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Doudoulakakis A, Spiliopoulou I, Spyridis N, Giormezis N, Kopsidas J, Militsopoulou M, et al. Emergence of a Staphylococcus aureus clone resistant to mupirocin and fusidic acid carrying exotoxin genes and causing mainly skin infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(8):2529–2537. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00406-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Gostev V, Kruglov A, Kalinogorskaya O, Dmitrenko O, Khokhlova O, Yamamoto T, et al. Molecular epidemiology and antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus circulating in the Russian Federation. Infect Genet Evol J Mol Epidemiol Evolut Genet Infect Dis. 2017;53:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Khemiri M, Akrout Alhusain A, Abbassi MS, El Ghaieb H, Santos Costa S, Belas A, et al. Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-t6065-CC5-SCCmecV-agrII in a Libyan hospital. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;10:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Liu X, Deng S, Huang J, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Yan Q, et al. Dissemination of macrolides, fusidic acid and mupirocin resistance among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):58086–58097. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Saleem F, Fasih N, Zafar A. Susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin and other alternate agents: report from a private sector hospital laboratory. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67(11):1743–1746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Udo EE, Al-Sweih N. Dominance of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in a maternity hospital. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0179563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Udo EE, Boswihi SS. Antibiotic resistance trends in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Kuwait hospitals: 2011–2015. Med Princip Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Health Sci Centre. 2017;26(5):485–490. doi: 10.1159/000481944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Wang JT, Huang IW, Chang SC, Tan MC, Lai JF, Chen PY, et al. Increasing resistance to fusidic acid among clinical isolates of MRSA. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(2):616–618. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]