Abstract

Aim:

The study purpose is to explore adolescent and adult women’s experiences, perceptions, beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors related to bladder health across the life course using a socioecological perspective. Lower urinary tract symptoms affect between 20-40% of young adult to middle-aged women, with symptoms increasing in incidence and severity with aging. There is limited evidence to address bladder health promotion and prevention of dysfunction. This first study of the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium is designed to address gaps in existing qualitative research in this area.

Design:

This focus group study will be implemented across seven geographically diverse United States research centers using a semi-structured focus group guide informed by a conceptual framework based on the socioecological model.

Methods:

The study was approved in July 2017. A total of 44 focus groups composed of 6-8 participants representing six different age categories (ranging from 11 to over 65 years) will be completed. We aim to recruit participants with diverse demographic and personal characteristics including race, ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, urban/rural residence, physical/health conditions, and urinary symptom experience. Up to 10 of these focus groups will be conducted in Spanish. Focus group transcripts will undergo content analysis and data interpretation to identify and classify themes and articulate emerging themes.

Discussion:

This foundational qualitative study seeks to develop an evidence base to inform future research on bladder health promotion in adolescent and adult women.

Impact:

This study has the potential to provide new insights and understanding into adolescent and adult women’s lived experience of bladder health, the experience of lower urinary symptoms, and knowledge and beliefs across the life course.

Keywords: Bladder health, qualitative research, women, adolescents, females, focus groups, urinary symptoms

1.0. Introduction

Although extensive research has been conducted on bladder function and dysfunction, research is limited on healthy bladder habits, what it means to have a healthy bladder, and primary prevention of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Important gaps in the literature include an operational definition of bladder health and how normal bladder function contributes to bladder health. To address these and other gaps in knowledge about bladder health, the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium is engaging in transdisciplinary research to conceptualize and define bladder health, with the goal of developing evidence for the primary prevention of LUTS and promotion of bladder health across the life course (Harlow et al., 2018).

The PLUS Consortium defines women’s bladder health in terms of bladder function that “permits daily activities, adapts to short-term physical or environmental stressors, and allows optimal well-being (e.g., travel, exercise, social, occupational, or other activities)” and is “not merely the absence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) (Lukacz et al., 2018).” These characteristics are consistent with World Health Organization guidelines, which affirm that health is more than an absence of dysfunction or disease and includes physical, mental, and social well-being (Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, 1946).

Little is known about how adolescent and adult women view bladder health and the socioecological factors that shape bladder habits. To inform primary prevention efforts, it is important to understand the experience of a healthy bladder and to explore how individuals make meaning of bladder experiences. This includes characterizing the social processes shaping the individual’s lived experience of bladder health, and identifying language used by adolescent and adult women to describe bladder function (Digesu et al., 2008). These research efforts are critical in helping construct explanatory frameworks for understanding what makes or keeps the bladder healthy.

To foster understanding of bladder health from adolescent and adult women’s perspectives, the PLUS Consortium will conduct the Study of Habits, Attitudes, Realities and Experiences (SHARE). The aim of this qualitative study is to explore adolescent and adult women’s experiences, perceptions, beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors related to bladder health and function. It will use focus group methodology to gain insight from people in a shared social context (Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, 2014; Ulin, Robinson, & Tolley, 2005). This paper outlines the transdisciplinary research protocol used for this multi-site qualitative focus group investigation. The protocol describes how a life course perspective is applied to engage adolescent and adult women in describing their lived experiences of bladder health. To characterize and contextualize focus group participants, information about participants’ history of LUTS and typical toileting practices will be collected through quantitative measures administered after the focus group sessions.

2.0. Background

The SHARE study aims to address gaps in existing qualitative and quantitative bladder health research in adolescent and adult women. Limitations of the existing literature include paradigms emphasizing biological and disease-focused thinking and limited attention to diversity of race and ethnicity, geographic, and socioeconomic characteristics. For example, in a recent systematic review of qualitative evidence, Mendes et. al identified 28 studies that explored urinary incontinence in women aged ≥18 and found that many of them described how adult women generally do not perceive urinary incontinence as a preventable condition, but rather see it as an inevitable process of aging (Mendes, Hoga, Goncalves, Silva, & Pereira, 2017). Similarly, at least one qualitative study found a gap in information on pelvic floor disorders among African American and Latin American women, despite a demand for health education. Other studies have explored adult women’s experiences of bladder sensations (De Wachter, Heeringa, van Koeveringe, & Gillespie, 2011; Heeringa, de Wachter, van Kerrebroeck, & van Koeveringe, 2011; Zhou, Newman, & Palmer, 2018) associated with LUTS, such as urinary tract infections (Baerheim, Digranes, Jureen, & Malterud, 2003), recurrent cystitis (Alraek & Baerheim, 2001), and overactive bladder (OAB) (Heeringa, van Koeveringe, Winkens, van Kerrebroeck, & de Wachter, 2012).

The few studies that have examined experiences among non-symptomatic populations (Coyne, Harding, Jumadilova, & Weiss, 2012; Heeringa et al., 2011) suggest that the experiences and terminology used by healthy women can differ from those with LUTS, indicating a need for health care providers and researchers to better understand experiences of women without LUTS. Additionally, existing qualitative studies generally have not explored a life course perspective, and instead have examined discrete groups such as older adults (Andersson, Johansson, Nilsson, & Sahlberg-Blom, 2008; Dowd, 1991; Horrocks, Somerset, Stoddart, & Peters, 2004; Park, Yeoum, Kim, & Kwon, 2017; Smith et al., 2011; Teunissen, van Weel, & Lagro-Janssen, 2005) or post-partum women (Buurman & Lagro-Janssen, 2013; Wagg, Kendall, & Bunn, 2017). Further, the existing literature has minimal integration of theoretical or conceptual models and rarely includes a socioecological perspective (Fultz & Herzog, 2001; Hagglund & Wadensten, 2007). SHARE addresses this limitation by being one of the first studies to purposefully employ a life course perspective and socioecological conceptual framework to formulate novel insights about bladder health.

2.1. Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

The PLUS Consortium developed a conceptual framework to guide its initial prevention research agenda (Brady et al., 2018). This framework acknowledges that individuals are embedded within social ecologies. Socioecological models are based on theories of individual behavior and interpersonal relations, which may be thought of as proximal influences on health, as well as sociological structures, such as institutions, communities, cultures, and policy landscapes, which may be thought of as distal social influences (Sallis & Owen, 2015). The PLUS conceptual framework informed the development of the SHARE focus group interview guide. Questions are designed to encourage participants to reflect upon their current and past experiences in different socioecological and life course contexts.

3.0. The Study

3.1. Study Aim

The purpose of the study is to explore adolescent and adult women’s experiences, perceptions, beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors related to bladder health and function across the life course.

3.2. Design

The PLUS Consortium identified a need for a qualitative research study to explore how adolescent and adult women perceive and experience bladder health and function across the life course. Qualitative methods facilitate the description of complex phenomena. Focus groups were selected as the qualitative research methodology because they provide an interactive forum for the expression of a wide range of responses and common/divergent opinions and beliefs. Focus groups are well-suited for the exploration of social norms and processes, cultural influences, and institutional influences, as well as the language people use when talking to peers. Focus groups are particularly appropriate for our population, which ranges from young adolescents to older adult women who may have widely varying levels of experience with LUTS, with some participants having little or no experience. Group discussion may help participants generate ideas between each other, activate and uncover memories of experiences, and serve to generate or formulate opinions. In the health sciences, focus groups are becoming the method of choice for eliciting input from a broad range of constituencies, including key stakeholders and marginalized groups of individuals whose voices often are not heard.

3.3. Organization of Study Team

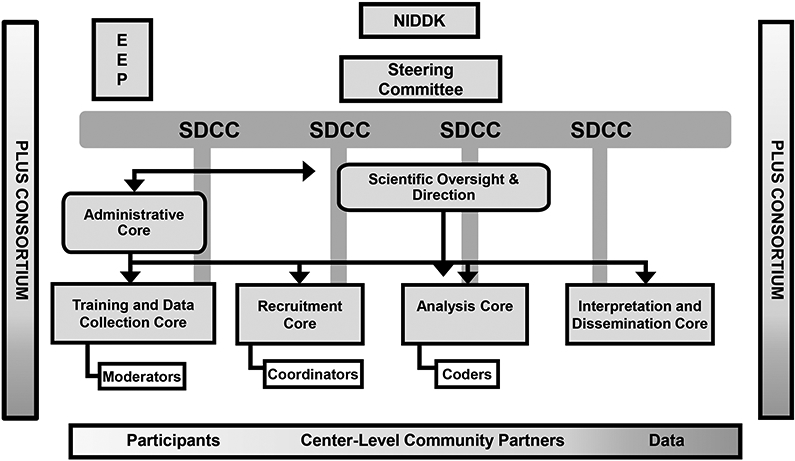

Consistent with the transdisciplinary composition of the PLUS Consortium, the SHARE study team is comprised of scientists, clinicians, and advocates with expertise in a range of disciplines, including social and behavioral science (social psychology, medical sociology, health education); medicine (pediatrics, geriatrics, urogynecology, midwifery, behavioral medicine); public health (health disparities, community-based participatory research); and a community-based advocate. To support the level of study activities essential for the development and implementation of our multi-site focus group study, the transdisciplinary study team is organized into five cores for specific study-related tasks: administrative project management; recruitment; moderator training and data collection; data analysis; and data interpretation and dissemination (Figure 1). Each core consists of 2-4 members who developed initial protocols for their component. Protocols were reviewed and amended as needed by the full study team. As each component of the study unfolds, the aligned core will take leadership in operationalizing and monitoring the process as outlined in the manual of procedures. This approach allows us to capitalize on individual expertise and efficiency while continuing to support a transdisciplinary approach to the overall study process.

Figure 1. Organizational chart for the Study of Habits, Attitudes, Realities, and Experiences (SHARE).

EEP – External Expert Group

SDCC – Scientific Data Coordinating Center

NIDDK – National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

PLUS – The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

3.4. Study setting and participants

This multi-site study will be conducted across seven geographically diverse U.S. research centers using a study-specific semi-structured focus group guide. All PLUS research centers will participate in recruiting participants and conducting focus groups.

3.4.1. Participants.

Participants will be recruited in 6 age groups:

Early adolescents: 11-14 years

Adolescent girls: 15-17 years

Young adult women: 18-25 years

Adult women: 26-44 years

Middle-aged women: 45-64 years

Older women: 65+ years

3.4.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria.

Eligibility criteria include cisgender women and adolescents who are English-speaking (for English language focus groups); Spanish-speaking (for Spanish language focus groups); able to read and provide written informed consent (or assent and parental consent for minors); and have an absence of any physical or mental condition that would impede participation. Pregnant women will be excluded due to the known effects of pregnancy on LUTS, but prior pregnancy is not an exclusion or inclusion criterion.

Although we will not recruit based on parity, we will periodically examine the distribution of parity within and across focus groups. If our observations suggest an issue with combining parous and non-parous women, we could further delineate groups by parous and non-parous status, retaining the age categories previously noted.

While our focus is on understanding adolescent and adult women’s experiences of a healthy bladder, to ensure we have a full conceptualization of this experience, we will include participants without respect to LUTS status. This strategy contributes to a representative sample of adolescent and adult women with a wide range of experiences, which may or may not be defined by women as abnormal. In a prior study that purposefully recruited based on continence status, women’s discussion of the experience of leakage changed over time after a screening process during which new terminology and concepts of leaking were introduced by the investigative team (Thomas et al., 2010). To avoid this risk, we will not pre-screen potential participants, but will collect individual written information about LUTS and toileting behavior at the end of each focus group session. This will allow us to monitor the distribution of adolescent and adult women with respect to past and present experience of LUTS. If needed, we will adjust recruitment strategies or inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure a range of experience. We aim to recruit a sample that is diverse with respect to race, ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, physical/health conditions, LUTS status, and urban/rural residence—including up to 10 focus groups conducted in Spanish.

3.4.3. Sample Size.

Within each of the six age group categories, we will conduct 3-5 focus groups, consistent with best practice recommendations,(e.g., (Morgan, 1997). The unit of analysis is the focus group itself, regardless of the number of participants comprising each group session. We therefore proposed a sample size of 40-44 focus groups, with an average of 6-8 participants per focus group, necessitating the recruitment of 240-352 participants.

3.5. Recruitment Methods

Recruitment will be conducted across all seven PLUS research centers, leveraging the recruitment method(s) most suited for success at each center. In preparation for this study, the PLUS Community Engagement Subcommittee conducted a survey of centers to identify center-specific recruitment expertise and research populations (see Table 1 for overview). Trained Research Coordinators (RCs) at each PLUS center will conduct recruitment to saturate the planned age groups and ensure variability and comparability across sites and samples.

Table 1.

Potential populations for recruitment by age group and special populations

| Age Group | Special Populations | Geography | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Adolescents (11-14) |

Adolescents (15-17) |

Young women (18-25) |

Adult women (26-44) |

Middle-aged women (45-64) |

Older women (65+) |

LGBTQ | People who speak a language other than English |

Racial and/or ethnic minority groups |

People who are uninsured or have low SES |

Occupations of interest to PLUS |

Urban | Rural | |

| Site | |||||||||||||

| Site 1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Site 2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Site 3 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Site 4 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Site 5 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Site 6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Site 7 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

SES=socioeconomic status

We will utilize a matrix outlining major (a) socio-ecologic considerations of each age group, (b) ideal recruitment groups relevant to bladder health, (c) age-related issues relevant to recruitment within each age group, (d) optimal recruitment portals by age group, and (e) optimal recruitment methods (Table 2). Whenever possible, we will reach out through existing community partnerships to optimize recruitment efforts. Community partners, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, and/or community health centers that are trusted community resources will serve as recruitment portals and advisors to facilitate the recruitment of racial and ethnic minority populations, rural populations, and women whose primary language is Spanish. Community engagement partners will also advise on locations for hosting focus group sessions to accommodate potential participants’ preferences and optimize attendance.

Table 2.

Priority populations by age group, socioecological context, and recruitment considerations

| Adolescence | Adulthood | Older Adulthood | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Adolescent | Emerging Adulthood |

Young Adult | Mid/Late | ||

| Chronological Age | 11-14 | 15-17 | 18-25 | 26-44 | 45-64 | 65+ |

| Major Social Ecological Considerations | ✓ Onset of menarche ✓ Puberty ✓ Onset of sexual activity ✓ School/peers ✓ Sports |

✓ Puberty ✓ School ✓ Sports ✓ Dating/Peers ✓ Onset of sexual activity |

✓ Sexual activity ✓ Pregnancy ✓ Childbirth ✓ Work ✓ School ✓ Childrearing |

✓ Sexual activity ✓ Pregnancy ✓ Childbirth ✓ Work ✓ School ✓ Childrearing |

✓ Work ✓ Aging parents ✓ Child/grandchild rearing ✓ College planning ✓ Planning for retirement |

✓ Transitioning roles–parent, partner, caregive ✓ Issues of retirement |

| Ideal Recruitment Groups† | ✓ Girl-focused after school programs | ✓ Running clubs ✓ School clubs |

✓ College athletes ✓ Workers in restricted context |

✓ Workers in restricted context ✓ Mothers groups |

✓ Caregivers ✓ Workers in restricted context |

✓ Senior clubs, activity groups |

| Age-Related Issues Relevant to Recruitment | ✓ Parental consent ✓ Highly engaged in social media |

✓ Parental consent ✓ Highly engaged in social media |

✓ Busy ✓ Multitasking |

✓ Busy ✓ Multitasking |

✓ Busy ✓ Multitasking |

✓ Mobility ✓ Computer literacy ✓ Larger font material ✓ Trust-building |

| Optimal Recruitment Portals | ✓ Schools ✓ Sports teams ✓ Online ✓ Girls Scouts |

✓ Schools ✓ Sports teams-community ✓ Sports teams–school ✓ School clubs ✓ Online |

✓ School ✓ Work ✓ Community resources ✓ Health/ community centers ✓ OB/GYN practices |

✓ Work ✓ Community resources ✓ Health/ ✓ community centers ✓ OB/GYN practices ✓ Elementary schools |

✓ Worksites ✓ High schools/college ✓ Community sites ✓ Grocery stores ✓ Health/wellness centers ✓ Healthcare settings |

✓ Community senio centers ✓ YMCAs ✓ Faith-based groups ✓ Area Agencies o Aging ✓ Healthcare settings |

| Optimal Recruitment Methods | ✓ Social Media ✓ Text |

✓ Social Media ✓ Text ✓ Flyer (trusted coffee shop, store) |

✓ Email ✓ Social Media ✓ Text ✓ Flyer |

✓ Email ✓ Social Media ✓ Text ✓ Flyer |

✓ Email ✓ Flyer |

✓ Word of mouth ✓ Flyer ✓ Phone call |

Ideal recruitment groups are based on the recruitment goal of identifying groups of participants with a shared social context suitable to engage in facilitated dialogue, while also finding adequate diversity by sociodemographic characteristics for which there is a known association to health (e.g., race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education), both within and across groups.

Focus groups will be conducted in four phases to allow for monitoring the composition of the recruited focus groups for diversity and to identify gaps in recruitment (Table 3). This recruitment plan allows us to leverage age-appropriate best practices with center-specific strengths, allowing for an adaptive approach to recruitment.

Table 3.

Phases and planned distribution of focus groups by age and population across sites†

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 45-64 years, English | 65+ years | 26-44 years, English | 18-25 years | 15-17 years | 18-25 years | 11-14 years |

| Phase 2 | 26-44 years, English 45-64 years Spanish |

45-64 years, African American 65+years, African American |

26-44 years, Spanish 45-64 years, English |

18-25 years 26-44 years |

18-25 years, rural 65+ years, rural |

26-44 years 45-65 years |

11-14 years 15-17 years |

| Phase 3 | 26-44 years, Spanish 65+ years English |

45-64 years, rural 65+ years, rural |

45-64 years, Spanish 65+ years, English |

26-44 years 45-64 years |

26-44 years, urban 45-64 years, urban |

26-44 years 45-64 years |

15-17 years 18-25 years |

| Phase 4 | 65+ years Spanish | 45-64 years | 65+ years, Spanish | 15-17 years | 11-14 years 11-14 years, African American |

65+ years | 18-25 years |

Additional attention to diversity of participants by socioeconomic status, which was also considered in recruitment outreach

3.6. Study Implementation

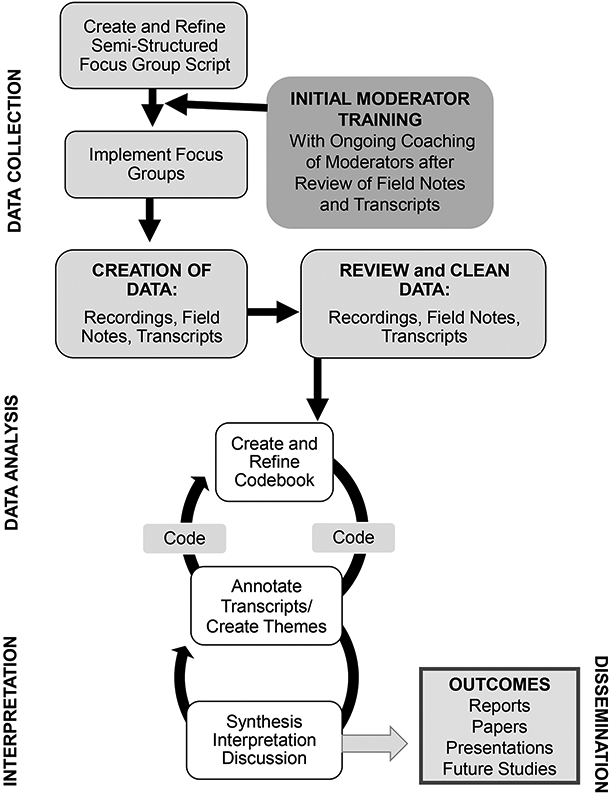

The overall study flow for this qualitative project is provided in Figure 2. A Manual of Procedures (MOP) developed by the research team is in place to guide the study process.

Figure 2.

Study Flow

3.6.1. Focus Group Moderator Training.

Moderators trained in qualitative research principles and focus group methodology will conduct each session. In focus group methodology, the moderators serve as the primary data collection instruments guided by a well-designed focus group guide. Focus group moderators will be female. Given significant geographic and disciplinary differences in qualitative research training and practice, it is important that moderators be grounded in the PLUS conceptual framework and the value of a community-informed approach, which are central tenets of the SHARE study. Therefore, all focus group moderators will receive training in the qualitative research principles adopted by the PLUS Consortium, best practices for focus group research, and the focus group study protocol. Training will be both online and in-person; use action learning, community-engagement and didactic sessions; and continue through focus group data collection.

3.6.2. Focus Group Procedures.

Each focus group session will be guided by a semi-structured focus group guide and will last approximately 90 minutes. The focus group guide is derived from the PLUS conceptual framework. The guide has five sections and 16 core questions with accompanying probes (See Table 4). Each section and accompanying questions correspond to categories of the conceptual framework. For each focus group, a site-specific designated member of the research team will take written field notes using a standardized format to record methodological, contextual, and reflective observations. Sessions will be audio-recorded for later transcription.

Table 4.

Focus group guide questions and corresponding categories of the PLUS conceptual framework

| Focus Group Concepts† | Individual Biology/Body |

Individual Mind/Behavior |

Interpersonal | Institutions and Organizations |

Society and Community |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEALTHY BLADDER | |||||

| 1. Have you heard about the bladder (where it is)? | |||||

2. What are your ideas about what it means to have a Healthy Bladder? (or When you hear the phrase Healthy Bladder, what does this mean to you or what comes to mind)

|

|||||

| 3. What are your ideas about what it means to have an unhealthy bladder? (or When you hear the phrase Healthy Bladder, what come to mind?) | |||||

4. In your view, what are some of the things that help people to have a Healthy Bladder?

|

|||||

5. What are some of the things that might cause our bladders to be unhealthy? (or cause bladder problems)

|

|||||

| 6. Are there certain conditions that might affect your bladder health? | |||||

| 7. Are there rules at home or on the job that might affect your bladder health? | |||||

8. When your bladder gets full or is ready to empty, how does that feel to you?

|

|||||

| KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION | |||||

| 9. What have you heard about the bladder, where it is, and what it does? | |||||

10. How/where, did you learn about your bladder and how it works?

|

|||||

11. How do you think people (your age) learn about bladder habits, that is, when to go to the bathroom or how often?

|

|||||

12. If someone (your age) had a question about their bladder and/or bladder function, who do you think they would talk to?

|

|||||

| LUTS and CARE-SEEKING | |||||

| 13. What challenges have you (or people your age) faced with the bladder, how it feels, or how it works? | |||||

14. How do you (or people) cope with the challenges when it happens?

|

|||||

| 15. Is there a certain time of day (or night) when your bladder is especially a problem? | |||||

| 16. Are there certain places or activities when your bladder is especially a problem? | |||||

| TERMINOLOGY | |||||

17. What do you (people your age) call it when you go to the bathroom to pass urine?

|

|||||

| PUBLIC HEALTH MESSAGING | |||||

18. We are thinking of developing some programs to inform the public about bladder health.

|

LUTS=lower urinary tract symptoms; PLUS: Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Shaded boxes show the level of the PLUS conceptual framework that a particular concept may inform.

At the conclusion of the focus group, participants will be asked to complete self-administered measures (Table 5) to characterize demographics, medical history (focusing on OB/Gyn/Urologic history), LUTS status, and toileting behaviors. Completion is expected to take about 30 minutes. Each participant will receive a gift certificate valued at $50.

Table 5.

Quantitative measures

| Construct | Questionnaire | Tool Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Adults | Lower Urinary Tract Symptom (LUTS) Tool |

|

| Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Children | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Pediatric Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-CLUTS)† |

|

| Toileting Behaviors | Toileting Behaviors-Women’s Elimination Behaviors (TB-WEB) |

|

| Demographic and Medical History | Demographic and Medical History Questionnaire |

|

De Gennaro M, Niero M, Capitanucci ML, von Gontard A, Woodward M, Tubaro A, Abrams P. Validity of the international consultation on incontinence questionnaire-pediatric lower urinary tract symptoms: a screening questionnaire for children. J Urol. 2010 Oct;184(4 Suppl):1662-7

3.7. Quantitative Measures

The Lower Urinary Tract Symptom Tool (LUTS Tool) will be used to assess LUTS in adult women. A separate instrument, the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Pediatric Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-CLUTS), will be used to measure LUTS in participants between the ages of 11 and 17 years. Toileting behaviors will be assessed using the Toileting Behaviors-WEB (TB-WEB), which elicits information about behaviors women use in public and private environments to empty their bladders (Palmer & Newman, 2015; Wang & Palmer, 2010, 2011). These measures will be used to summarize participant characteristics using descriptive statistics.

4.0. Qualitative Data Management, Analysis, and Interpretation

4.1. Data Management

The steps for data management are iterative (See Figure 2). Audio-recordings will be uploaded to the PLUS Scientific Data-Coordinating Center (SDCC). Audio recordings will be professionally transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by the site-specific research coordinator. Names of specific places or individuals will be redacted. Each participant in the focus groups will be identified by their pseudonym throughout recording and transcription to protect confidentiality and to facilitate tracking responses and linking them to survey and demographic variables, if needed during analysis.

The Spanish-language focus groups will be transcribed in Spanish and then translated into English using best practices to assure accuracy in translation (Clark, Birkhead, Fernandez, & Egger, 2017). Briefly, a native Spanish-speaking moderator and the translator will review all original and translated transcripts. All significant inconsistencies will be discussed and resolved by a team of three native Spanish speakers, including a co-investigator, moderator, and translator.

A glossary of terms will be maintained to inventory shared terminology. Data analysis will be conducted with de-identified written transcripts. Field notes will be appended to the transcription and used in data analysis and interpretation. Field notes also will serve as a tool for assessing fidelity of the interview guide and determining ongoing moderator training needs.

4.2. Data Analysis

The analysis will be guided by the socioecological model and the life course approach. For identifying themes and concepts associated with the experience of healthy bladders, we will perform a directed content analysis (DCA). DCA is a systematic process for making context-based inferences from the data (Elo & Kyngas, 2008). It begins with a conceptual framework for structuring the analysis and utilizes a deductive approach to explore textual data for insights relevant to the research question, with the goal of validating and extending knowledge in the area of interest. This analytic approach has particular utility in research areas where current theory or previous evidence needs further elucidation and description (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This analysis will assist researchers in identifying emergent insights related to 1) the lived experience of bladder health across the life course; 2) socioecological contextual factors shaping bladder behavior; and 3) knowledge, assumptions, beliefs, values, and understandings about a healthy bladder. Participants’ dialogue may also inform the Consortium’s understanding of specific risk and protective factors potentially linked to bladder health and LUTS.

Our main subgroup analysis will focus on age. For coding, each focus group will be identified by its participants’ age group and language used (Spanish or English). The general demographic descriptors for the composition of the groups will also be available for use during analysis. There will be the opportunity to conduct analyses within age group, as well as across age categories, to identify similarities and differences.

Standard qualitative data analysis techniques will be used, beginning with coding and memoing (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Saldaña, 2015). We will analyze transcripts using a deductive coding scheme informed by the socioecological model and our working definition of bladder health. All transcripts will be imported into DeDoose®, an online platform for qualitative data analysis designed to facilitate the organization and analysis of qualitative data. As a web-based platform, it will be accessible in real time from multiple locations. This will facilitate the analytical work performed at a single site for the initial content analysis and will also allow for site-specific analysis as needed for selected scenarios, populations, or age-specific considerations.

Memoing entails making notations of researchers’ conceptual and theoretical insights relating to the themes and potential codes. Although it is part of the analytic process, memoing also plays an important role in the development and articulation of conceptual and theoretical frameworks during the interpretative phase of the study. Review of the field notes will be completed to complement the memoing process, contextualize focus group data, and identify any unique codes or concepts that may augment the initial coding scheme.

The codebook will be developed after each life course group is complete to ensure that it was applicable to all the data (inclusive of new concepts/topics/subthemes). Each code will be designated by name (typically using participant phrasing) and specified by an operational definition with inclusion and exclusion criteria and quotes from focus group excerpts illustrative of codes. Variations within codes will generate subcodes. Patterns and associations across codes and coded text segments will be analyzed to develop thematic categories that indicate relationships among codes. These relationships can be configured in several ways, including linear, sequential, circular, concentric, and hierarchal arrangements.

Coders will be trained in the codebook and in DCA. The analysis core members (see Figure 1) will read all the transcripts independently and develop a list of coding categories that capture the range of participants’ responses. Using an iterative process, team members will compare results until a consensus is reached on the codes and their definitions. Following the completion of this process, the coding team will compile the resulting coding scheme and the definitions of the codes into a codebook. A separate team of coding staff will then use the codebook to code all transcripts.

The investigators will conduct weekly supervision meetings with staff and resolve coding disagreements through consensus. Developing the codebook will be an iterative process, and refinements may be made during the debriefing sessions described below (see Data Interpretation). Additional research questions and analytic approaches may emerge, prompting subsequent re-analysis of the data. These data management and analysis approaches meet the “Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research” for content analysis and grounded theory, as described by O’Brien et al. (O'Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014) and recommended by others (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory, 2010; The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research, 2010).

4.3. Data Interpretation

Data interpretation is an iterative and reflexive process for deriving meaning, making theoretical connections, constructing explanatory frameworks, and drawing relevant and credible conclusions supported by the data. The socioecological model and life course approach will guide the initial phase of the interpretative process. Subsequently, data interpretation will proceed as an open-ended, inductive process guided by team science and informed by a transdisciplinary perspective that utilizes the integrative expertise and experience of social and behavioral scientists, clinicians and interventionists, public health researchers and educators, and community-based advocates.

The key mechanisms of data interpretation are data immersion and team dialogue, which will require regularly scheduled conference calls and dedicated face-to-face meetings. During these interactions, we will discuss emerging themes and insights from the analysis. We will include focus group moderators in the debriefing process to ensure that their perspectives are represented. The emergence of team insights that transcend disciplines and cut across socioecological contexts can usher in innovative ways of thinking about the healthy bladder and how to promote bladder health. Additionally, the insights will be shared with community engagement groups when feasible to obtain feedback on the interpretation of emergent insights.

4.4. Validity and Reliability

Validity and reliability within qualitative research are often discussed as credibility and trustworthiness (Holloway & Galvin, 2016; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014). The following strategies will be employed for building credibility and trustworthiness of our data and interpretations at multiple points during our study.

Before and during data collection.

Moderator training will support validity by ensuring that different focus groups were asked similar questions and that the context of the focus group was conducive to open and honest answers from participants with a range of backgrounds. This increases what Lincoln and Guba (1985) refer to as “dependability,” which offers transparency in our research approach, as well as what Holloway and Galvin (2016) refer to as “authenticity and fairness.” Researchers will have prolonged engagement with the study and its data, with the same researchers involved in and observing data collection and interpretation to offer opportunities for reflection and awareness of context.

During analysis.

Our analytic strategy has several built-in methods with attention to credibility and trustworthiness. Coders will be trained and transcripts will be double-coded for accuracy of code assignment; coders will also be trained to look for consistencies and inconsistencies with codes and emerging themes. Research team members who observed the focus groups will be involved in the inductive code development and will oversee the coding process to ensure that context is kept relevant and at the forefront of coding decisions. A detailed accounting of coding decisions and actions will be maintained to provide a “decision trail” of analytic decisions (Holloway & Galvin, 2016).

During interpretation.

Interpretation teams will consist of experienced investigators who work together to understand what the data are saying and seek alternative explanations, rather than relying on disciplinary paradigms. The investigator team represents a range of disciplines and expertise, with varying levels of previous experience in bladder health and qualitative research. This diversity will aid the interpretation process, with fewer assumptions about what will be learned or found in the data, and will help triangulate interpretive findings. Also, during interpretation, credibility and trustworthiness will be supported through community validation strategies, a variation on member checking. The preliminary findings will be presented to multiple stakeholder groups to ‘check’ the findings against the experiences and expertise of other knowledgeable informants, including community members, research participants, moderators, research coordinators, and other PLUS investigators.

4.5. Ethical considerations

Institutional review board (IRB) review was completed in July 2017 using a central process for six of the seven sites. This included having one of the research centers serve as the lead for the IRB process and the other five sites’ IRBs giving oversight to the primary lead site. The internal IRB for the seventh site did not have a process in place to support using such a reliance agreement, so it completed a separate approval process using the same protocol and materials as the primary site. Participants will complete the written informed consent process when they arrive for the focus group.

To assure confidentiality, participants will be asked to select and use a pseudonym or a number to identify themselves when they are speaking. Instructions to the participants will include asking them to not use names during the discussion. The moderator will be trained to use friendly reminders to limit mention of specific names of places or people during focus group discussion and to have focus group participants use their pseudonym when speaking to facilitate transcription. Finally, any personal identifiers used inadvertently will be deleted from the written transcripts.

While the protocol is low risk, we considered the potential for participants to become uncomfortable or distressed by discussing bodily functions or experiences. Using a trauma-informed lens, the research team was cognizant of the high prevalence of adolescent and adult women experiencing trauma in the United States. In recognition of the potential that a participant may have a negative response to discussing bodily experiences, a trauma-informed approach was used to develop a protocol based on best practices to manage distress should it arise during the conduct of a focus group session (Baccellieri et al., 2018).

5.0. Discussion

The protocol for the SHARE focus group study uses a transdisciplinary approach to design, develop, and implement research investigating adolescent and adult women’s perceptions of bladder health and function to address gaps in existing qualitative and quantitative bladder health research. Merging clinical, social behavioral, and public health perspectives, our transdisciplinary approach brings together investigators with a unique array of expertise.

Innovative approaches for focus group recruitment include leveraging the networks of previously established community partnerships to recruit adolescent and adult women of all ages from diverse racial and ethnic groups (i.e., White, African American, Hispanic [both English-speaking and Spanish-speaking]) and rural, urban, and suburban communities across the United States. This approach augments the transferability of the study by facilitating the inclusion of diverse and underrepresented populations. This further addresses the gaps of prior qualitative investigations. Future investigations should expand inclusion of underrepresented populations. Additionally, community engagement research would optimally include community partners in the initial development of the study design.

Because this is not a longitudinal study, we are not able to interview participants more than once—making a life course design beyond the scope of this study. However, SHARE does apply a life course perspective on bladder health and function by recognizing that experiences during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood can accumulate to impact bladder health over time. Adolescent and adult women will be asked to reflect on their current and past experiences during the focus groups. This approach will enable us to collect data that, combined across age groups, may inform future life course research questions. For example, identifying perceived facilitators of and constraints on toileting behaviors at different ages could contribute to new understandings of how accumulated environmental risk and protective factors may impact bladder health. This approach can lead to the development of further life course research questions or strategies to address facilitators and barriers to bladder health.

The SHARE protocol systematically employs a socioecological conceptual framework to structure the focus group interview guide and carry out data analyses and interpretation. This approach is facilitated by the collaboration of SHARE investigators whose own programs of research have focused on different levels of social ecology across the individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and societal levels.

The development of the SHARE protocol was a process that unfolded over time, requiring insight and flexibility to respond to emerging issues. For example, early in the protocol development process, we recognized the need to develop and implement a centralized training program for focus group moderators to assure consistency of research procedures across sites. Additionally, we recognized the need for a distress protocol to sensitize moderators to the potential for emotional distress during focus group sessions and provide guidelines for responding to distress. We also found it necessary to make adjustments to study design and instrument development to accommodate adolescent and Spanish-speaking populations.

5.1. Limitations

Study limitations include potential difficulties in making comparisons or drawing meaningful conclusions about variation in bladder health attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors among age, race, ethnic, or residential sub-groups. Additionally, while this is a study about bladder health and function among adolescent and adult women and includes participants with and without LUTS, it is not designed to make comparisons based on participants’ symptomology or clinical status.

6.0. Conclusions

This multi-site qualitative focus group study employs best practice approaches to conducting a focus group investigation, including an organizational and operational structure that promotes transdisciplinary team science. Use of the PLUS conceptual framework, which employs a socioecological model with a life course perspective, will allow for potential insights and new understanding of the lived experiences of adolescent and adult women’s bladder health and/or LUTS.

Acknowledgements

Participating research centers at the time of this writing are as follows:

Loyola University Chicago - 2160 S. 1st Avenue, Maywood, Il 60153-3328

Linda Brubaker, MD, MS, Multi-PI; Elizabeth Mueller, MD, MSME, Multi-PI; Colleen M. Fitzgerald, MD, MS, Investigator; Cecilia T. Hardacker, RN, MSN, Investigator; Jeni Hebert-Beirne, PhD, MPH, Investigator; Missy Lavender, MBA, Investigator; David A. Shoham, PhD, Investigator

University of Alabama at Birmingham - 1720 2nd Ave South, Birmingham, AL 35294

Kathryn Burgio, PhD, PI; Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH, Investigator; Alayne Markland, DO, MSc, Investigator; Gerald McGwin, PhD, Investigator; Beverly Williams, PhD, Investigator

University of California San Diego - 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0021

Emily S. Lukacz, MD, PI; Sheila Gahagan, MD, MPH, Investigator; D. Yvette LaCoursiere, MD, MPH, Investigator; Jesse N. Nodora, DrPH, Investigator

University of Michigan - 500 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Janis M. Miller, PhD, MSN, PI; Lawrence Chin-I An, MD, Investigator; Lisa Kane Low, PhD, MS, CNM, Investigator

University of Pennsylvania – Urology, 3rd FL West, Perelman Bldg, 34th & Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Diane Kaschak Newman, DNP, ANP-BC, FAAN PI; Amanda Berry, PhD, CRNP, Investigator; C. Neill Epperson, MD, Investigator; Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD, MPH, FACSM, FTOS, Investigator; Ariana L. Smith, MD, Investigator; Ann Stapleton, MD, FIDSA, FACP, Investigator; Jean Wyman, PhD, RN, FAAN, Investigator

Washington University in St. Louis - One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130

Siobhan Sutcliffe, PhD, PI; Colleen McNicholas, DO, MSc, Investigator; Aimee James, PhD, MPH, Investigator; Jerry Lowder, MD, MSc, Investigator; Mary Townsend, ScD, Investigator

Yale University - PO Box 208058 New Haven, CT 06520-8058

Leslie Rickey, MD, PI; Deepa Camenga, MD, MHS, Investigator; Toby Chai, MD, Investigator; Jessica B. Lewis, MFT, MPhil, Investigator

Steering Committee Chair: Mary H. Palmer, PhD, RN; University of North Carolina

NIH Program Office: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases, Bethesda, MD

NIH Project Scientist: Tamara Bavendam MD, MS; Project Officer: Ziya Kirkali, MD; Scientific Advisors: Chris Mullins, PhD and Jenna Norton, MPH;

Scientific and Data Coordinating Center (SDCC): University of Minnesota - 3 Morrill Hall, 100 Church St. S.E., Minneapolis MN 55455

Bernard Harlow, PhD, Multi-PI; Kyle Rudser, PhD, Multi-PI; Sonya S. Brady, PhD, Investigator; John Connett, PhD, Investigator; Haitao Chu, MD, PhD, Investigator; Cynthia Fok, MD, MPH, Investigator; Sarah Lindberg, MPH, Investigator; Todd Rockwood, PhD, Investigator; Melissa Constantine, PhD, MPAff, Investigator

Funding

The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) - National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) through cooperative agreements (grants U01DK106786, U01DK106853, U01DK106858, U01DK106898, U01DK106893, U01DK106827, U01DK106908, U01DK106892). Additional funding from: National Institute on Aging, NIH Office on Research in Women’s Health and the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributor Information

Lisa KANE LOW, Women’s Studies and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan.

Beverly Rosa WILLIAMS, Department of Medicine, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB).

Deepa R. CAMENGA, Department of Emergency Medicine, Section of Research, Yale School of Medicine.

Jeni HEBERT-BEIRNE, Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Sonya S. BRADY, Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Diane K. NEWMAN, Department of Surgery, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia PA.

Aimee S. JAMES, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO.

Cecilia T. HARDACKER, Howard Brown Health, Chicago, IL; Rush University College of Nursing.

Jesse NODORA, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

Sarah E. LINKE, Department of Family Medicine & Public Health, UC San Diego.

Kathryn L. BURGIO, Department of Medicine, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Department of Veterans Affairs, Birmingham, Alabama.

References

- Alraek T, & Baerheim A (2001). 'An empty and happy feeling in the bladder.. .': health changes experienced by women after acupuncture for recurrent cystitis. Complement Ther Med, 9(4), 219–223. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Johansson JE, Nilsson K, & Sahlberg-Blom E (2008). Accepting and adjusting: older women's experiences of living with urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs, 28(2), 115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccellieri A, Low LK, Brady S, Bavendam T, Burgio K, Williams B, … The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. (2018). Distress Protocol for Focus Group Methodology: Bringing a Trauma-Informed Practice to the Research Process for the PLUS Consortium Study of Habits, Attitudes, Realities and Experiences (SHARE) Study. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting & Expo, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Baerheim A, Digranes A, Jureen R, & Malterud K (2003). Generalized symptoms in adult women with acute uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection: an observational study. MedGenMed, 5(3), 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Bavendam TG, Berry A, Fok CS, Gahagan S, Goode PS, … Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Research, C. (2018). The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) in girls and women: Developing a conceptual framework for a prevention research agenda. Neurourol Urodyn, 37(8), 2951–2964. doi: 10.1002/nau.23787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman MB, & Lagro-Janssen AL (2013). Women's perception of postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction and their help-seeking behaviour: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci, 27(2), 406–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Birkhead AS, Fernandez C, & Egger MJ (2017). A Transcription and Translation Protocol for Sensitive Cross-Cultural Team Research. Qual Health Res, 27(12), 1751–1764. doi: 10.1177/1049732317726761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne KS, Harding G, Jumadilova Z, & Weiss JP (2012). Defining urinary urgency: patient descriptions of "gotta go". Neurourol Urodyn, 31(4), 455–459. doi: 10.1002/nau.21242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wachter SG, Heeringa R, van Koeveringe GA, & Gillespie JI (2011). On the nature of bladder sensation: the concept of sensory modulation. Neurourol Urodyn, 30(7), 1220–1226. doi: 10.1002/nau.21038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digesu GA, Khullar V, Panayi D, Calandrini M, Gannon M, & Nicolini U (2008). Should we explain lower urinary tract symptoms to patients? Neurourol Urodyn, 27(5), 368–371. doi: 10.1002/nau.20527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd TT (1991). Discovering older women's experience of urinary incontinence. Res Nurs Health, 14(3), 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngas H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs, 62(1), 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fultz NH, & Herzog AR (2001). Self-reported social and emotional impact of urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc, 49(7), 892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagglund D, & Wadensten B (2007). Fear of humiliation inhibits women's care-seeking behaviour for long-term urinary incontinence. Scand J Caring Sci, 21(3), 305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Bavendam TG, Palmer MH, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, Lukacz ES, … Simons-Morton D (2018). The Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium: A Transdisciplinary Approach Toward Promoting Bladder Health and Preventing Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Women Across the Life Course. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 27(3), 283–289. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa R, de Wachter SG, van Kerrebroeck PE, & van Koeveringe GA (2011). Normal bladder sensations in healthy volunteers: a focus group investigation. Neurourol Urodyn, 30(7), 1350–1355. doi: 10.1002/nau.21052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa R, van Koeveringe GA, Winkens B, van Kerrebroeck PE, & de Wachter SG (2012). Do patients with OAB experience bladder sensations in the same way as healthy volunteers? A focus group investigation. Neurourol Urodyn, 31(4), 521–525. doi: 10.1002/nau.21232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway I, & Galvin K (2016). Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks S, Somerset M, Stoddart H, & Peters TJ (2004). What prevents older people from seeking treatment for urinary incontinence? A qualitative exploration of barriers to the use of community continence services. Fam Pract, 21(6), 689–696. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberelis G, & Dimitriadis G (2014). Focus group research: retrospect and prospect. In Leavy P (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 315–340). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacz ES, Bavendam TG, Berry A, Fok CS, Gahagan S, Goode PS, … Brady SS (2018). A Novel Research Definition of Bladder Health in Women and Girls: Implications for Research and Public Health Promotion. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 27(8), 974–981. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes A, Hoga L, Goncalves B, Silva P, & Pereira P (2017). Adult women's experiences of urinary incontinence: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep, 15(5), 1350–1408. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldaña J (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: PAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL (1997). Focus Group as Qualitative Research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, & Cook DA (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med, 89(9), 1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MH, & Newman DK (2015). Women's toileting behaviours: an online survey of female advanced practice providers. Int J Clin Pract, 69(4), 429–435. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Yeoum S, Kim Y, & Kwon HJ (2017). Self-management Experiences of Older Korean Women With Urinary Incontinence: A Descriptive Qualitative Study Using Focus Groups. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 44(6), 572–577. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. (2010). (Bryant A & Charmaz K Eds.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. (2010). (Bourgeault Ivy, Dingwal R, & Vries RD Eds.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2015). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, & Owen N (2015). Ecological Models of Health Behavior. In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (Eds.), Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL, Nissim HA, Le TX, Khan A, Maliski SL, Litwin MS, … Anger JT (2011). Misconceptions and miscommunication among aging women with overactive bladder symptoms. Urology, 77(1), 55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen D, van Weel C, & Lagro-Janssen T (2005). Urinary incontinence in older people living in the community: examining help-seeking behaviour. Br J Gen Pract, 55(519), 776–782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Low LK, Tumbarello JA, Miller JM, Fenner DE, & DeLancey JO (2010). Changes in self-assessment of continence status between telephone survey and subsequent clinical visit. Neurourol Urodyn, 29(5), 734–740. doi: 10.1002/nau.20827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulin PR, Robinson ET, & Tolley EE (2005). Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wagg AR, Kendall S, & Bunn F (2017). Women's experiences, beliefs and knowledge of urinary symptoms in the postpartum period and the perceptions of health professionals: a grounded theory study. Prim Health Care Res Dev, 18(5), 448–462. doi: 10.1017/S1463423617000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, & Palmer MH (2010). Women's toileting behaviour related to urinary elimination: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs, 66(8), 1874–1884. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, & Palmer MH (2011). Development and validation of an instrument to assess women's toileting behavior related to urinary elimination: preliminary results. Nurs Res, 60(3), 158–164. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182159cc7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Newman DK, & Palmer MH (2018). Urinary Urgency in Working Women: What Factors Are Associated with Urinary Urgency Progression? J Womens Health (Larchmt), 27(5), 575–583. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]