Abstract

Objective:

This article aims to review the literature published over the past five decades related to the experiences of women who have undergone induced lactation.

Methods:

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted using PubMed, the Library of Congress, Google Scholar, SAGE, and ScienceDirect. The following search keywords were used: adoptive breastfeeding, induced lactation, non-puerperal lactation, extraordinary breastfeeding, and milk kinship. The search was restricted to articles written in English and published from 1956 to 2019. All study designs were included except for practice protocols.

Results:

A total of 50 articles about induced lactation were retrieved. Of these, 17 articles identified the experiences of women who underwent induced lactation. The articles included original papers (n=7), reviews (n=5), and case reports (n=5). Four articles were specifically related to Malaysia, and the others were international. These 17 articles concerning the experiences of women who induced lactation will be reviewed based on four themes related to inducing lactation: (a) understanding women’s perception of satisfaction, (b) emotional aspects, (c) enabling factors, and (d) challenges.

Conclusion:

Identifying a total of only 17 articles on induced lactation published over the last 53 years suggests that the subject is understudied. This review provides emerging knowledge regarding the experiences of women who have induced lactation in terms of satisfaction, emotions, enabling factors and challenges related to inducing lactation.

Keywords: adoptive breastfeeding, induced lactation, milk kinship

Introduction

Adoptive breastfeeding, referred to as induced lactation, is relevant in non-puerperal cases. Induced lactation is the process by which a non-puerperal woman is stimulated to lactate; more simply, the term refers to breastfeeding without prior pregnancy.1,2 Induced lactation has been described as the process of breastmilk production in a mammal (woman) without recent pregnancy and/or birth and may involve the use of herbs, supplements, medications, mechanical stimulation, and/or the infant to facilitate breastmilk production.2

Healthcare practitioners must comprehend the experiences of women who induce lactation to be able to provide unique, customized support for each individual.3 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports this stance in its policy statement on “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk,” noting that pediatricians should provide counseling to adoptive mothers who decide to breastfeed through induced lactation, a process that requires professional support and encouragement.4

Malaysia is a Muslim country, which has a bearing on the topic as a motivating factor for Muslim adoptive parents to induce lactation is to establish religious milk kinship. Saari et al. reported a lack of research on induced lactation in Malaysia, particularly involving the Muslim community, regarding why women might induce lactation and the factors that motivate them to do so.5 Rahim et al. recommended that future investigations develop a practical model for induced lactation in Malaysia to explore maternal views related to the mothers’ needs, obstacles, experiences, perceptions, and motivations.6

The objective of this article is to review the literature that has been published over the past five decades regarding the experiences of women who have undergone induced lactation. Therefore, this review covers perceptions of satisfaction, emotional aspects, enabling factors, and the challenges that women who underwent induced lactation have experienced. It is hoped that this review will provide healthcare professionals insight into women’s experience of induced lactation and acknowledge the vital role they play in assisting women in this process.

Methods

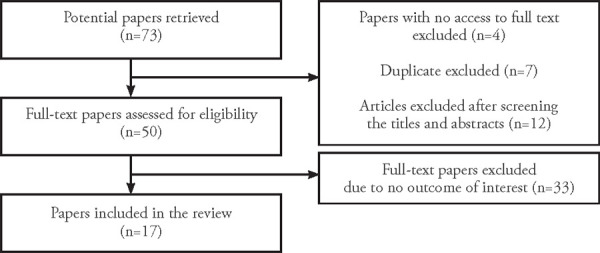

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted using PubMed, the Library of Congress, Google Scholar, SAGE, and ScienceDirect. The inclusion criteria were articles written in English, published from 1956 to 2019, and reporting outcomes related to satisfaction, emotions, enablers, and challenges in induced lactation. The search included the following study designs: reviews, original papers, and case reports. The exclusion criteria were articles in languages other than English, articles without access to the full paper, and outcomes not related to satisfaction, emotions, enablers, and challenges in induced lactation. Studies with a practice protocol design were also excluded. The following search keywords were used: adoptive breastfeeding, induced lactation, non-puerperal lactation, extraordinary breastfeeding, and milk kinship. The retrieved articles were compiled and managed using EndNote X8 software according to the respective topics. The search was conducted with multiple databases, which resulted in retrieving some duplicate citations, which were deleted using the EndNote X8 software. After deduplication, the search results were screened by title and abstract, followed by reading the full texts and removing the articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Based on the repetition of the themes that emerged when reading the full texts, four aspects were chosen for consideration: satisfaction, emotions, enablers, and challenges in inducing lactation. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the screening and reviewing process.

Figure 1. Screening process for the literature review.

Results

A total of 73 potential papers about induced lactation were retrieved. During the screening process, papers that were excluded were those lacking access to the full text (n=4), duplicates (n=7), and articles with titles and abstracts that did not match the review’s objective (n=12). Consequently, 50 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility, from which full-text papers with no outcome of interest (n=33) were excluded. The content of the papers that offered no outcome of interest included folklore, religious views, and using galactogogues to induce lactation. Finally, 17 papers were included in the review. Four articles were specifically related to Malaysia, and the others were international. The resulting studies comprised seven original papers, five reviews, and five case reports. Based on the themes that repeatedly emerged when reading the full-text papers, the women’s experiences were reviewed based on the following topics related to inducing lactation: (a) understanding women’s perception of satisfaction, (b) emotional aspects, (c) enabling factors, and (d) challenges.

Understanding Women’s Perception of Satisfaction in Inducing Lactation

Auerbach et al. conducted a study in which 240 women who experienced adoptive nursing were asked about the parameters that led to success in a self-report questionnaire comprising closed-ended questions.7 The study reported that most of the women were satisfied with their experiences.7 Along the same lines, Goldfarb asked 228 participants how satisfied they were with their efforts to induce lactation. In this case, most of the women who induced lactation reported being satisfied with the overall experience and, given the opportunity, 83% said they would repeat the process.2

Most of the participants in Saari et al.’s study did not experience pregnancy or childbirth, yet they expressed the desire to enjoy motherhood by breastfeeding their adopted child.5 In that study, 67% of the mothers claimed that they enjoyed breastfeeding their child. The researchers noted repeated mentions of the words “satisfied,” “relieved,” “enjoy,” “pleasure,” and “indescribable feeling.”5 In contrast to the papers that focused on understanding the mothers’ perspectives, Bryant8 and Wittig et al.3 published systematic reviews focusing on pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods to induce lactation. Both reviews reported that the maternal-infant bonding that resulted from induced lactation was the main source of satisfaction among the participants despite the rigorous process and their inability to produce an adequate milk supply to breastfeed exclusively.3,8

Table 1 summarizes the findings on understanding women’s perception of satisfaction in inducing lactation in chronological order by year of publication. Based on the publications mentioned above, it is evident that the satisfaction of inducing lactation helps establish the maternal-infant bond, which is promoted by the process of inducing lactation.

Table 1. Findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation.

Author (Year) |

Study design Number of participants/articles |

Summary of the findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation |

|---|---|---|

Auerbach et al.7 (1981) |

Original paper (quantitative design) 240 participants |

Most of the participants felt that the mother-infant relationship was important, and 76% evaluated adoptive nursing “positively.” No clarification of the term “positively.” |

Bryant8 (2006) |

Review 26 articles as references |

The primary goal was not milk production but establishing an emotional bond with the infant. |

Wittig et al.3 (2008) |

Review 18 articles as references |

Based on information drawn from the articles in the review, it can be concluded that most women who induce lactation cannot produce enough breastmilk to exclusively breastfeed their infant, but they find satisfaction in this process because of the maternal-infant bonding it promotes. |

Goldfarb2 (2010) |

Original paper (mixed qualitative and quantitative design) 228 participants |

The author reported that 76% of the women were “satisfied” with no clarification of the term “satisfied” because that part of the study was quantitative. |

Saari et al.5 (2015) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 12 participants |

The findings showed that 67% of the mothers enjoyed breastfeeding their child, with repeated mentions of the words “satisfied,” “relieved,” “enjoy,” “pleasure,” and “indescribable feeling.” |

Emotional Aspects of Inducing Lactation

Gribble reviewed the evidence in physiological and behavioral research studies regarding how breastfeeding plays a significant role in developing the attachment relationship between an adopted child and mother.9 The results revealed that breastfeeding an adopted child is an attempt to ensure the quality of attachment between the mother and baby, whereby physical contact between them through breastfeeding enables a baby suffering from the trauma of separation from his/her birth mother to feel secure.9

In the qualitative section of Goldfarb’s paper, the participants were asked to describe how they felt during the process of inducing lactation2 The text was analyzed for repeated words, phrases, and themes. The prevalent comments were feelings of awe, wonder, and amazement, followed by love. Mothers reported healing from grief due to infertility as an essential motivation for inducing lactation.2

Saari et al. asserted that induced lactation undertaken by participants elicited maternal instincts in adoptive mothers.5 After experiencing induced lactation, all participants agreed that the process prepared them to be mothers and that breastfeeding was a pleasurable experience. All the participants also agreed that breastfeeding entailed affection and touch, exerting a positive impact on the adoptive mothers and the babies they were nursing.5

Table 2 presents a summary of the findings on the emotional aspects of inducing lactation in chronological order by year of publication. Both positive and negative emotions were associated with induced lactation, as addressed by Goldfarb.2 Positive emotions were viewed as a source of motivation to induce lactation, and negative emotions were associated with challenges to inducing lactation.2

Table 2. Findings on the emotional aspects of inducing lactation.

Author (Year) |

Study design Number of participants/articles |

Summary of the findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation |

|---|---|---|

Gribble9 (2006) |

Review 163 articles as references |

Breastfeeding an adopted child was an attempt to ensure the quality of attachment between the mother and baby. Physical contact between the mother and baby through breastfeeding helped a baby suffering from the trauma of separation from his/her birth mother feel secure. |

Saari et al.5 (2015) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 12 participants |

Induced lactation led to a unique feeling, i.e., maternal instinct in adoptive mothers. All the participants agreed that breastfeeding prepared them to be mothers and was a pleasurable experience. All the participants also agreed that the affection and touch associated with breastfeeding had a positive impact. |

Goldfarb2 (2010) |

Original paper (mixed qualitative and quantitative design) 228 participants |

Mothers reported that healing from grief due to infertility was the most significant motivation to induce lactation. Positive emotions were related to the mother-infant relationship, whereas negative emotions were related to technical challenges in inducing lactation, such as concerns about breastmilk supply, finding time to pump, and issues related to breast pumps. |

Enabling Factors in Inducing Lactation

In this paper, enabling factors make it possible (or easier) for a woman to induce lactation. Based on an international article, this sub-topic is divided into psychosocial and technical factors, including the regimes and tools used to induce lactation.3

Psychosocial Factors Enabling Induced Lactation

Szucs et al. published a case report of premature twins whose adoptive mother induced lactation.10 Both infants received their adoptive mother’s milk exclusively at the age of two months. This approach reflects careful planning by the adoptive mother beginning in the prenatal period, her active role during the infants’ hospital stay, and the support she received from healthcare personnel and family members.10

Lakhkar11 and Nemba12 maintained that the mothers’ motivation was the primary factor that enabled them to induce lactation, followed by family support. The researchers concluded that a mother who was motivated, confident, and knowledgeable about induced lactation had the best chance to succeed.11,12 Goldfarb2 and Auerbach et al.7 found that enhancing the bond between the mother and baby was a key factor in breastfeeding an adopted child.

Women in Malaysia are driven to breastfeed their adopted babies through cultural exposure and religious beliefs to obtain milk kinship.5 Saari et al. developed a model for adoptive breastfeeding that integrated both the Fiqh and scientific perspectives of adoptive breastfeeding.5 Research has reported that the psychosocial enablers to induce lactation help fulfill religious milk kinship (Shariah-based) and, from a humanitarian perspective, foster compassion (science-based).13 Table 3 presents a summary of the findings on the psychosocial factors enabling induce lactation in chronological order by year of publication.

Table 3. Findings on the psychosocial factors enabling induced lactation.

Author (Year) |

Study design Number of participants/articles |

Summary of the findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation |

|---|---|---|

Auerbach et al.7 (1981) |

Original paper (quantitative design) 240 participants |

Factors reported as psychosocial enablers for inducing lactation: i. Mother-infant bonding ii. Fulfilling emotional needs of babies iii. Body contact with baby iv. Nutritional benefits of infants v. Care by the mother vi. Ability to produce breastmilk vii. Breastfeeding as a reflection of femininity viii. Mother’s physical changes |

Nemba12 (1994) |

Case report 37 participants |

A mother who was motivated, confident, and knowledgeable on the topic experienced the best chance of successfully inducing lactation. |

Lakhkar11 (2000) |

Case report 23 participants |

A mother’s motivation and family support acted as psychosocial enablers to induce lactation. |

Gribble14 (2003) |

Review 87 articles as references |

Suggested that adoptive mothers in developing countries might have greater milk production than mothers in Western countries because the former were more knowledgeable about breastfeeding, practiced frequent breastfeeding, had close physical contact with children, and lived in cultures that supported breastfeeding. |

Goldfarb2 (2010) |

Original paper (qualitative and quantitative design) 228 participants |

Inducing lactation fulfilled the emotional needs of babies and healed the mothers’ grief due to infertility. |

Szucs et al.10 (2010) |

Case report 1 participant |

Support from healthcare professionals and family members played a role in ensuring that premature twins received their adoptive mother’s milk exclusively at the age of 2 months. |

Saari et al.5 (2015) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 12 participants |

The themes outlined with regard to these psychosocial factors included “mahram,” “maternal instinct,” “psychology,” “offspring,” and “obligation.” These themes are briefly summarized as follows: i. “Mahram” and “Obligation”: To establish religious milk kinship ii. “Maternal instinct”: To satisfy the maternal instincts of adoptive mothers who have not experienced childbirth iii. “Psychology”: Fulfill the desire to establish a bond between the adoptive mother and child iv. “Offspring”: To overcome grief from not being able to conceive |

Saari et al.13 (2017) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 12 participants |

This study developed a Guideline Model of Breastfeeding Adopted Child alligned with the Fiqh and science perspective. Psychosocial enablers for inducing lactation included obligation to fulfill religious milk-kinship (shariah-based) and compassion (science-based). |

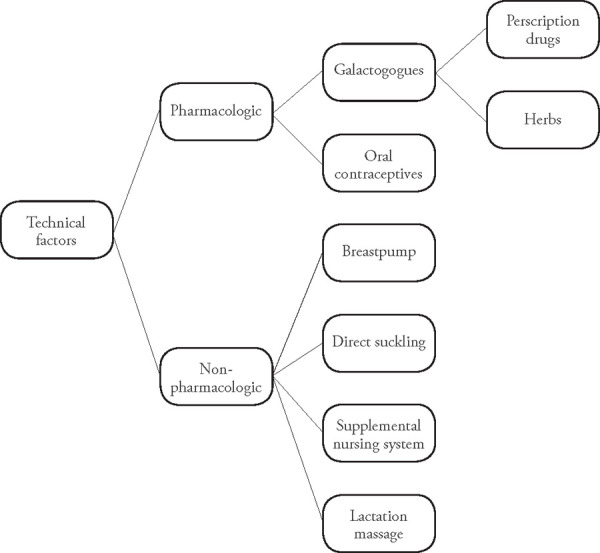

Technical Factors: Different Regimes that Enable Inducing Lactation

Common approaches to inducing lactation include pharmacologic (hormonal stimulation) and non-pharmacologic (breast stimulation) methods, often used in combination.3 Non-pharmacologic methods may involve women inducing lactation via breast stimulation through hand expression, using a breast pump, via direct suckling at the breast, or using a supplemental nursing system.2,3,7,15

Table 4 summarizes the reported technical factors, including pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic approaches, that enable women to induce lactation in chronological order by year of publication. Auerbach et al.7 and Goldfarb2 described various regimes used to induce lactation. Patel also demonstrated that a back massage is a simple method that can be implemented in a regime to induce lactation without straining resources.16 Cheales-Siebenaler et al. described an adoptive mother who produced breastmilk for her infant via various regimes, which resulted in adequate weight gain for her infant.17

Table 4. Technical factors enabling induced lactation.

Author (Year) |

Study design Number of participants/articles |

Summary of the findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation |

|---|---|---|

Wittig et al.3 (2008) |

Review 18 articles as references |

Procedures commonly used to induce lactation include pharmacologic (hormonal stimulation) and non-pharmacologic (breast stimulation) methods, often in combination. |

Goldfarb2 (2010) |

Original paper (mixed-methods design) 228 participants |

This paper described various regimes and their popularity (by percentage) in terms of being used to induce lactation, summarized below: i. Domperidone (92%) ii. Fenugreek (78%) iii. Birth control pill (63%) iv. Blessed thistle (68%) v. Nothing (6%) vi. Metoclopramide (4%) vii. Expressed breastmilk before infant’s arrival via pumping (75%) or hand expression (14%) viii. Pumped after most feeds for 10 minutes (40%) ix. Pumped after baby arrived, but not yet suckling on the breast (32%) x. Put baby to the breast with a supplemental nursing system (51%) Maximum milk supply was reported by the participants using the following protocols: i. Domperidone, birth control, and pumping (45%) ii. Domperidone and pumping (12%) iii. Domperidone and supplemental nursing system (12%) |

Rahim et al.6 (2017) |

Review 19 articles as references |

No previous research has revealed any effective guidelines in place for induced lactation in Malaysia. Establishing these guidelines is essential in Malaysia, given the recent expansion in Malaysians’ awareness of breastfeeding adopted children. |

Auerbach et al.7 (1981) |

Original paper (quantitative design) 240 participants |

This paper reported that most of the respondents practiced one or more of the following to induce lactation: i. Read three or four books about breastfeeding or two or more articles on adoptive nursing before the arrival of their adopted infant ii. Improved or supplemented maternal diet iii. Practiced nipple stimulation before or after infant’s arrival iv. Occasionally used hormone preparations to simulate pregnancy or increase milk ejection reflex |

Abejide et al.15 (1997) |

Case report 6 participants |

All six women in the case study produced breastmilk by breast-suckling alone; however, no details were included indicating how long they breastfed. |

Cheales-Siebenaler et al.17 (1999) |

Case report 1 participant |

An adoptive mother induced lactation by bilateral pumping, metoclopramide, and oxytocin nasal spray. She did not use oral or parenteral hormones to induce lactation. She supplemented her adopted infant at the breast with the help of a supplementary feeding-tube device. She began to produce breastmilk when the infant was 4 months old (suddenly began to express four ounces of breastmilk per breast). The mother stopped her protocol at this time (stopped pumping and taking medications) and proceeded to direct-feed her infant without supplementation throughout the fourth and fifth months, with the infant gaining adequate weight. |

Patel et al.16 (2013) |

Original paper (quantitative design) 220 participants |

Back massage was effective in improving lactation in all the parameters assessed regarding the baby’s well-being, which was significantly progressive in the study group in comparison to the control group. |

Challenges in Inducing Lactation

In 2015, Saari et al. described the challenges of breastfeeding an adopted child in Malaysia.5 For example, some people may remain skeptical about breastfeeding an adopted child and consider the practice to be against human nature.5 Four years later, Cazorla et al. reported the challenges faced by mothers inducing lactation and divided them into three categories: challenges during induction of lactation, challenges during breastfeeding, and difficulties during breastfeeding cessation.18

Nemba conducted a study in Africa with 37 non-puerperal women ranging in age from 19 to 55.12 A total of 27 women completed the lactation induction program, 24 (89%) of whom successfully breastfed their well-nourished children. All the women who had never previously lactated were successful. Of the three mothers in whom induction was unsuccessful, two obtained a bottle from other sources; their children were malnourished. This study indicates that given a high degree of motivation combined with medication, support, and encouragement, lactation induction is likely to be highly successful and a critical factor in child survival.12

Table 5 presents a summary of the findings on the challenges in inducing lactation in chronological order by year of publication.

Table 5. Challenges in inducing lactation.

Author (Year) |

Study design Number of participants/articles |

Summary of the findings on the perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation |

|---|---|---|

Nemba12 (1994) |

Case report 37 participants |

Internal factor: i. Demotivated External factor: i. Lack of support and encouragement |

Gribble9 (2006) |

Review 163 articles as references |

Internal factor: i. Emotional instability in adoptive infants characterized by the cycle of progression-regression-progression of trying to directly breastfeed an adopted child. |

Bryant8 (2006) |

Review 26 articles as references |

Internal factor: i. Difficulty in committing time to frequently pump or breastfeed External factor: i. Lack of support from the public, which views inducing lactation as odd or not worth the effort |

Goldfarb2 (2010) |

Original paper (qualitative and quantitative design) 228 participants |

Internal factors: i. Worrying about the baby getting enough milk ii. Sore nipples/breasts iii. Fatigue iv. Getting baby to breastfeed v. Lack of preparation time External factor: i. Equipment difficulties |

Saari et al.5 (2015) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 12 participants |

Internal factors: i. Lack of commitment ii. Health problems External factors: i. Misconceptions ii. Lack of support iii. Non-conducive work environment iv. Career setback |

Cazorla-Ortiz18 (2019) |

Original paper (qualitative design) 9 participants |

Internal factors: i. Hardship to endure induced-lactation protocols ii. Doubts and fears while inducing lactation, such as not being able to produce milk or producing an insufficient amount of milk iii. Problems with breasts, such as cracked nipples, nipple blebs, blocked ducts, pain, and suction problems iv. Doubts if amount of milk supplied was sufficient during breastfeeding period v. The end of shared responsibility for breastfeeding with the partner during breastfeeding cessation vi. Reduced feeling of closeness to the child during breastfeeding cessation External factor: i. Difficulty obtaining information from health professionals |

Discussion

Understanding Women’s Perception of Satisfaction in Inducing Lactation

An adoptive mother seeking to induce lactation is a unique client in need of customized and personalized care. Although understanding the perception of satisfaction in inducing lactation is vital,3 the studies reviewed on this subject failed to clarify the term “satisfaction” in inducing lactation.2,3,5,7,8

Saari et al.5 and Goldfarb2 produced original papers that reported the outcome of experiences of induced lactation. For their part, Wittig et al.3 and Bryant8 presented reviews that reported conclusions drawn by reviewing previous studies. Several studies reported that satisfaction in women who induced lactation arose from the bond the practice established between the mother and the infant.3,5,7,8

In light of this factor, healthcare professionals helping mothers induce lactation should ask the mothers beforehand about their perceptions of satisfaction in inducing lactation. Practicing this approach will allow healthcare professionals to work with these mothers to achieve their goals.7 Because inducing lactation is an ongoing process, the perception of satisfaction might change as the process unfolds. It is recommended that healthcare professionals continually ask women who are inducing lactation about how they perceive satisfaction before they induce lactation and during follow-up visits. Such ongoing communication will enable professionals to develop the most realistic plan for an individual woman to achieve lactation.3

Emotional Aspects of Inducing Lactation

The studies that mentioned positive emotions associated with inducing lactation reported that the practice healed grief due to infertility, increased a woman’s maternal instincts, and benefited the adopted babies by ensuring a secure feeling after the trauma of being separated from their birth mother. In support of this idea, Goldfarb2 and Saari et al5 wrote original papers that reported on the outcome of experiences of induced lactation, and Gribble9 published a review based on the conclusions reported in previous studies.

The emotions reported from the studies mentioned above correlate with a recommendation rooted in dependency theory (Attachment Theory), which was developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in 1950. According to this theory, a baby’s dependency on the mother or mother figure is predicated on acceptance, protection, security, and caring.19 Based on these phenomena, love between a mother and child can be nurtured as early as the birth of the baby through such acts as breastfeeding. The positive effects that inducing lactation can have on women’s emotions support the recommendation that healthcare professionals should always take time to ask the women they are assisting about their emotional well-being during different phases of the lactation-inducing process. This approach provides healthcare professionals with both an opportunity to document the emotional changes that mothers go through when inducing lactation and additional insight about how women feel during different phases of that process. Thus, healthcare professionals will be better able to understand how to assist mothers in inducing lactation. The importance of this recommendation is underlined by the fact that over the course of 53 years, only three studies have addressed this subject, suggesting that more research on this topic is needed.2,5,9

Women who induce lactation may experience both positive and negative emotions. The negative emotions are related to the technical challenges, such as being concerned about breastmilk supply, finding time to pump, and issues related to breast pumps.2 Healthcare professionals can assist women with these aspects by offering regular follow-ups to identify the triggers that lead to negative emotions and discuss a plan to avoid those triggers and reduce or eliminate those emotions. Women going through induced lactation should be well supported emotionally because negative emotions will impair the autocrine process of lactation.20 Consultation sessions should also be attended by family members, a friend, a spouse, or a partner so that they can form a support system for the women inducing lactation to help them avoid emotional breakdowns.

Psychosocial and Technical Factors that Enable Inducing Lactation

Information regarding the social norms that positively affect a woman’s ability to induce lactation in developing countries is somewhat similar to breastfeeding in general. In developing countries, mothers are knowledgeable about breastfeeding because they have observed the practice from a young age.14,21 This familiarity results in increased confidence in breastfeeding and fewer breastfeeding problems.22,23 Some women also have beliefs about child care that optimize breastfeeding. For example, they allow unrestricted breastfeeding and keep their babies in close physical contact, day and night.24,25 This technique maximizes prolactin secretion and breast emptying, accelerating breast development and increasing milk production.26

The participants in the studies by Goldfarb2 and Auerbach et al.7 highly valued the development of love and an affectionate relationship between an adoptive mother and her adopted child because the adoptive woman did not carry the child in her womb. Efforts to establish a bond between an adoptive mother and her adopted child are unequivocally important as a Muslim in a local community in order to establish a mahram relationship. Both motivations act as psychosocial enablers to induce lactation, albeit from different perspectives. The goals are similar, involving an attempt to accept an adopted child as a part of one’s family to avoid any issue of segregation despite the lack of a biological connection.2,5,7 It is recommended that healthcare professionals understand the psychosocial factors that help women to induce lactation. While the reports regarding these psychosocial factors acknowledged their role in enabling induced lactation, it is recommended that healthcare professionals seek more in-depth information on this subject throughout the different phases of inducing lactation and during follow-ups. Each adoptive mother and breastfeeding baby has their own unique experience, and the psychosocial aspect has received less priority than the nutritional and immunity-enhancing aspects of breastfeeding.9 Seven articles on this subject over the past 53 years suggests that this topic is severely understudied and deserves further investigation. Gaining insight into the psychosocial enablers in inducing lactation will help healthcare professionals assist women in making practical management plans and managing their expectations.8

Moreover, many technical factors should be considered in induced lactation programs due to variations in the adoptive mothers’ religious and ethnic backgrounds, health status, and financial and environmental challenges.2,3,6,7,15–17 Figure 2 presents a summary of the technical factors that enable women to induce lactation.

Figure 2. Summary of the technical factors that enable a woman to induce lactation.

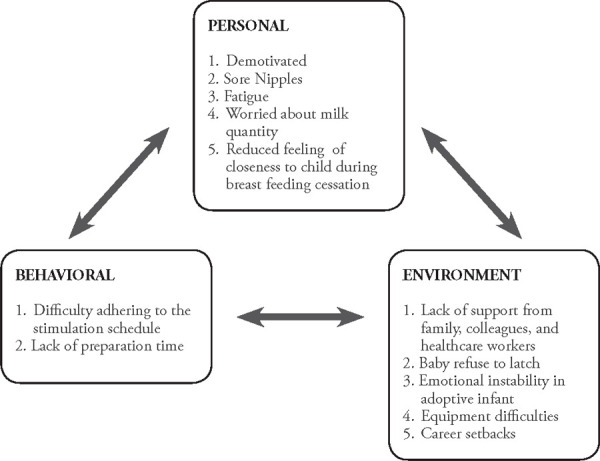

Challenges in Inducing Lactation

Although a review of the challenges to inducing lactation is limited in light of the lack of previous research in this area, women who induce lactation face internal challenges and external challenges. In general, internal challenges include a mother’s lack of motivation, difficulty maintaining the stimulation protocol while inducing lactation, encountering breast problems while pumping or breastfeeding, and the lack of confidence in the ability to produce breastmilk.2,5,8,12,13,18 External challenges are the lack of support from people, the lack of efficient tools for stimulation, and the emotional instability of the adopted child causing latching difficulties.5,9,12,18

Bandura’s27 social cognitive theory serves to summarize the challenges women go through when inducing lactation. Social cognitive theory is founded on a model of causation involving triadic reciprocal determinism. In reciprocal causation, behavior, cognition, personal factors, and environmental influences are interacting determinants that influence each other bidirectionally.27 Figure 3 describes how social cognitive theory can be incorporated into the results from the review considering the challenges of inducing lactation. As an elaboration of the theory, consider an example from the results that demonstrates the role of environmental factors, personal factors, and behavioral factors. A woman who lacks support from the people around her may be demotivated to induce lactation and have difficulty adhering to the stimulation schedule. For example, breastfeeding equipment difficulties (environmental factor) could lead her to have difficulty adhering to the stimulation schedule (behavioral factor) and cause her to worry about the quantity of breastmilk production (personal factor).

Figure 3. Social cognitive theory used to summarize the challenges faced when inducing lactation.

Conclusion

The review presented in this paper summarized the experiences of women who have induced lactation. The discussion enables a better understanding of participants’ perception of satisfaction, their emotions when inducing lactation, the enablers to inducing lactation, and the challenges in doing so. The information gathered from the articles on induced lactation in the past 53 years supports the conclusion that women seeking to induce lactation perceive satisfaction in terms of the maternal-infant bonding that develops as the process unfolds.3,8 Women who induced lactation also experienced positive and negative emotions. Positive emotions were related to the mother-infant relationship, while negative emotions stemmed from the technical challenges faced when inducing lactation, such as concerns about the breastmilk supply, finding time to pump, and issues related to breast pumps.2,5,9

Enablers for inducing lactation can be psychosocial or technical. Psychosocial enablers are related to bonding, nutritional benefits, feelings of self-competency when producing breastmilk, support from people in one’s surroundings, and the obligation to fulfill religious milk kinship.2,5,7,11,12 Technical enablers include pharmacologic (hormonal stimulation) and non-pharmacologic (breast stimulation) methods.3,6,7,15–17 used to induce lactation. The challenges associated with induced lactation encompass a variety of internal and external factors, reciprocally influenced by personal, behavioral, and environmental factors (one’s surroundings).2,5,8,9,12,18

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM/JEPeM/18040194).

Informed consent

The writing of this manuscript did not involve any respondents; therefore, informed consent was not required.

References

- 1.Biervliet FP, Atkin SL. Lactation by a commissioning mother in surrogacy. Human Reprod. 2012;l6(3):4l2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldfarb L. Results of a survey to assess the experiences of women who induced lactation. J Hum Lact. 2010;26(4):432–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittig SL, Spatz DL. Induced lactation: Gaining a better understanding. Matern Child Health J. 2008;33(2):76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000313413.92291.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AAP Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk [Internet] 2005. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2004-2491 Available from:

- 5.Saari Z, Yusof FM. Motivating factors to breastfeed an adopted child in a Muslim community in Malaysia. Jurnal Teknologi. 2015;74(1):211–20. doi: 10.11113/jt.v74.4424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahim NCA, Sulaiman Z, Ismail TAT. The availability of information on induced lactation in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24(4):5. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.4.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auerbach KG, Avery JL. Induced Lactation: A study of adoptive nursing by 240 women. Am J Dis Child. 1981;135(4):340–3. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1981.02130280030011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant CA. Nursing the adopted infant. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(4):374–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gribble KD. Mental health, attachment and breastfeeding: Implications for adopted children and their mothers. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szucs KA, Axline SE, Rosenman MB. Induced lactation and exclusive breast milk feeding of adopted premature Twins. J Hum Lact. 2010;26(3):309–13. doi: 10.1177/0890334410371210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakhkar BB. Breastfeeding in adopted babies. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37(10):1114–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemba K. Induced lactation: A study of 37 non-puerperal mothers. J Trop Pediatr. 1994;40(4):240–2. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saari Z, Yusof FM. Guideline model of adoptive breastfeeding for Muslim foster mothers in the Malay community in Malaysia. Int J of Islamic Studies. 2017;8(5):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gribble KD. The influence of context on the success of adoptive breastfeeding:developing countries and the west. Breastfeeding review. 2003;12(1):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abejide OR, Tadese MA, Babajide DE, Torimiro SEA, Davies-Adetugbo AA, Makanjuola ROA. Non-puerperal induced lactation in a Nigerian community: Case reports. Ann Trop Pediatr. 1997;17(2):109–14. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1997.11747872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel U, Ds G. Effect of back massage on lactation among postnatal mothers. Int J of Med Research and Review. 2013;1(1):5–13. doi: 10.17511/ijmrr.2013.i01.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheales-Siebenaler NJ. Induced lactation in an adoptive mother. J Hum Lact. 1999;15(1):41–3. doi: 10.1177/089033449901500111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cazorla-Ortiz G, Galbany-Estragués P, Obregon-Gutiérrez N, Goberna-Tricas J. Understanding the challenges of induction of lactation and relactation for non-gestating Spanish mothers. J Hum Lact. 2020;36(3):528–36. doi: 10.1177/0890334419852939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowlby J. The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal. 1958;39(5):350–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McManaman JL, Neville MC. Lactation: Physiology, nutrition and breastfeeding: Springer Nature. 2012. https://books.google.com.my/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hNvTBwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=lactation+physiology&ots=H3Ld6nJfkM&sig=eQdTofJzV2DYSVTG0uZkI1mGNPE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=lactation%20physiology&f=false Available from:

- 21.Jelliffe DB. Jelliffe EP Non-puerperal induced lactation. Pediatrics. 1972;50(1):170–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill PD, Aldag J. Potential indicators of insufficient milk supply syndrome. Research in Nursing & Health. 1991;14(1):11–9. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarter-Spaulding DE, Kearney MH. Parenting self-efficacy and perception of insufficient breast milk. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30(5):515–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuart-Macadam P. Breastfeeding: Bioculturual perspectives: Routledge. 2017. https://books.google.com.my/books?hl=en&lr=&id=SGZQDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=stuart+macadam&ots=a1r5PnS4My&sig=ftBnaL6gQPe0g8Nmil1a5gOIqEk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=stuart%20macadam&f=false Available from:

- 25.Lozoff B, Brittenham G. Infant care: Cache or carry. J Pediatr. 1979;95(3):478–83. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(79)80540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daly SEJ, Kent JC, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Frequency and degree of milk removal and the short-term control of human milk synthesis. Exp Physiol. 1996;81(5):861–75. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith K, Hitt M. Great minds in management: The process of theory development: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2006. https://books.google.com.my/books/about/Great_Minds_in_Management.html?id=P8kSDAAAQBAJ&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y Available from: [Google Scholar]