Abstract

Aim

To explore the perception of education and professional development of final-year nursing students who carried out health relief tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a global health emergency. This situation has exacerbated the need for additional healthcare employees, forcing the Spanish government to incorporate volunteer nursing students as auxiliary health staff.

Design

A qualitative study framed in the constructivist paradigm.

Methods

Twenty-two students of nursing were recruited. A purposeful sampling was implemented until reaching saturation. A semi-structured interview as a conversational technique was used to collect information based on three dimensions: academic curriculum, disciplinary professional development, and patient care. Subsequently, a content analysis of the information was carried out. Three phases were followed in the data analysis process: theoretical, descriptive-analytical, and interpretive. The COREQ checklist was used to evaluate the study.

Results

The most important results are linked to the students’ professional and academic preparation, how the nurses handled the pandemic situation and the characteristics of the COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions

Students require training in order to offer holistic care to patients, adapted to the context. Participants highlight the importance of professional values and recognise a high level of competence and autonomy in nurses.

Keywords: Competence, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Nursing, Qualitative study, Student

1. Introduction

We are facing a worldwide pandemic caused by an infection produced by the COVID-19 virus. In this situation, control, containment and exploration activities must be a global health priority (Corless et al., 2018). Thus, COVID-19 has been defined as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Ministerio de Sanidad & Gobierno de España, 2020a). A PHEIC always negatively affects large population groups (Simón Soria, 2016) and has an impact on health services and especially health professionals, nurses and, consequently, nursing students.

The effect of this pandemic on future nursing professionals stands out at the Spanish state level. First, it was seen at the academic level, as COVID-19 caused the suspension of clinical practice placements of nursing students in the first weeks of March 2020 and subsequently all face-to-face sessions after the declaration of a state of emergency (Ministerio de la Presidencia Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria democrática, 2020). Then, due to the lack of healthcare employees, the ministerial order SND/232/2020 of 15 March by the Government of Spain (Ministerio de Sanidad & Gobierno de España, 2020b) regulated the hiring of final-year nursing students as auxiliary health staff to carry out support activities under the supervision of a professional. Some students accepted these jobs because of social commitment, vocation, and professional ethics (Collado-Boira et al., 2020). Certainly, this scenario has caused a turning point in students' education and in the perception of their future profession.

Given that we are facing an unprecedented worldwide situation, the COVID-19 pandemic has completely transformed educational activity (Weis and Li, 2020). This crisis took the university community completely off guard and has highlighted the need to develop teaching strategies adapted to students’ healthcare preparation (Cervera-Gasch et al., 2020). These strategies should be based on periodic educational interventions and training programmes about COVID-19 (Modi et al., 2020).

Additionally, it should be noted that specific competencies are required to address the complexity of this situation under the disciplinary nursing domain, responding to the needs of professional practice (Duran, 2002). Skill development of newly graduated students is based on their personal background and experience, but also on organisational factors such as stability or workload (Charette et al., 2019). This transition from student to professional is a stressful and challenging process, modulated by the learning environment, amount of clinical work, and received supervision (Kaihlanen et al., 2018).

According to the facts already presented, it is necessary to explore the experiences of final-year nursing students who have worked as auxiliary health staff during the COVID-19 epidemic. The study is aimed at two specific objectives: 1. to establish the students’ perception of their education to prepare for this pandemic, and 2. to describe the students’ professional development from their perspective as future professionals.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This is a qualitative study framed in the constructivist paradigm that seeks to understand the problem based on the individual experiences of the participants (Ruiz Olabuénaga, 2012). Hence, according to personal constructivism, people learn by interacting with the environment and making sense of it and their experience (Mogashoa, 2014). From the constructivist perspective, the experience is fundamental since the conception of reality is based on the student and the construction that he or she makes of his or her experience. This approach rests on the fact that there is no objective reality, and that experience allows for the understanding of social constructions about the meaning of what has happened.

2.2. Context and participants

Participants were final-year students in the nursing degree programme at the Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Spain. A nursing degree in Spain is a four-year, full-time programme with an academic load of 240 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). ECTS has been adopted by most of the countries in the European Higher Education Area. It helps students to move between countries and to have their academic qualifications validated. It is the academic unit that represents the amount of work done by a student. Theoretical and practical lessons are integrated into this unit of measurement, including hours of work and study; the minimum number of hours is 25 and the maximum is 30 for ECTS (Royal Decree, 1125/2003). Based on this system, 60 ECTS credits (about 1500 h) reflect the dedication to work in an academic year. Additionally, this programme includes the 2300 h of clinical practice placement that students must complete according to European regulations (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2013). At the time of the suspension of the placements due to the pandemic, the final-year students had completed 84.6% of their placement hours.

The students were selected using purposeful sampling based on pragmatic and convenience criteria (feasibility, access, interest, time) until data saturation was reached (Berenguera et al., 2014, Luciani et al., 2019). The sample consisted of 22 students out of a population of 54. As required criteria, they had to work as auxiliary health staff in COVID-19 units (hospitals or nursing homes) or specialised units such as intensive care and emergency rooms. There were no exclusion criteria.

The recruitment of the students as auxiliary health staff was done by the department of health of the state government. The Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Spain offered the students advice and support during the period of their hiring, which started in March and ended in June 2020. Due to the immediacy of the measures and the situation of confinement and social isolation, the Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Spain offered online resources on the subject of COVID-19 to all the students of the faculty.

2.3. Data collection

For the data collection, the semi-structured interview as a conversational technique. The researchers carried out an interview protocol based on three content areas (Academic Preparation, Disciplinary Professional Development, Patient Care) to respond to the proposed objectives. Finally, a 10-question script was developed ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Research Questions.

| Content areas interview | Research questions |

|---|---|

| Academic preparation | How do you experience the COVID-19 pandemic situation? Tell me in what way you feel prepared to face your professional life. How would you describe your preparation to confront this crisis situation? Considering your education, what has helped you? Where is it lacking? |

| Disciplinary professional development | How has your perception of nursing changed? What about the care nurses would you highlight at this time? And about the rest of the health staff? |

| Patient care | What would you highlight with regard to the care given to COVID-19 patients? Do you think this situation somehow changed the care of the patients? |

The interviews were carried out by four researchers (OM, TC, AL, JR) during the month of April 2020. Note that the researchers are Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Spain professors with doctoral degrees (PhD). Although a teaching relationship with the interviewees was developed in previous courses, students in their final year only do clinical practice placements, to which none of the researchers were in any way linked. Therefore, the students should not have felt forced to participate for academic reasons. The students participated in the research voluntarily, and no compensation was given for participation Table 2.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic data.

| Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 3 | 13,6 |

| Women | 19 | 86,4 | |

| Way to university | Secondary education | 18 | 81,8% |

| Others | 4 | 18,2% | |

| Health worker | No | 14 | 63,7 |

| Yes | 8 | 36,3 | |

| Place of work | Hospital | 20 | 91% |

| Nursing homes | 2 | 9% | |

| Areas of care | Units COVID-19 | 19 | 86,4% |

| Special care units | 3 | 13,6% | |

The students who volunteered as auxiliary health staff and who met the inclusion criteria were contacted via the university register. Each researcher contacted five students at their convenience by telephone or email to provide information and request participation in the study. All the students contacted agreed to be interviewed. Later, in the analysis phase, the research team decided to include two more verification interviews to give consistency to the results, despite the fact that with 20 interviews the information had been saturated.

In response to the emergency situation decreed by the Spanish Government with indications of confinement and social isolation, the interviews were conducted via Skype and were recorded with the permission of all participants. A private space was recommended to ensure confidentiality and avoid interruptions. No interviews were repeated. The interviewers took field notes. The minimum duration was 35 min and the maximum was 1 h: 18 min. Subsequently, the interviews were transcribed verbatim and forwarded to the participants for their approval of the content.

2.4. Data analysis

The three phases described marked by Arbeláez, Onrubia (2014) were followed in the process: 1) Theoretical phase. The information was organised through an initial review of the documents; 2) Descriptive-analytical phase. First the interviews were described and analysed. Units of meaning were identified and later coded by condensation; 3) Interpretive phase. The content analysis obtained was interpreted according to the subtopics and emerging topics. These authors define the purpose of content analysis as verifying the presence of themes, words or concepts in a text, and their meaning in a specific context.

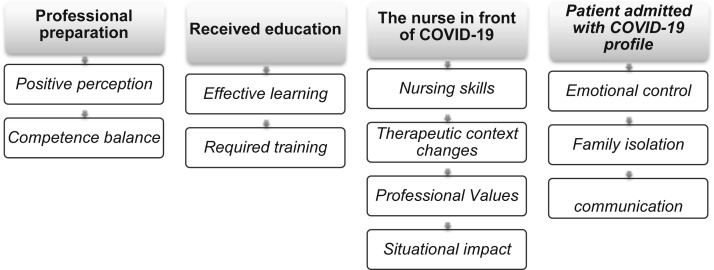

In our study, the content analysis was inductive; first, meaning units were selected from the interviews to later group and code them. The codes were grouped by their similarity and at the same time mutually excluded by the differences between them. This process resulted in 16 possible subtopics. Through the discussion process, the research team agreed on 11 subtopics. Finally, from these, 4 topics were obtained from the students’ experiences: perception of professional education; received training; insight on the nurse facing COVID-19 and experience with the patient admitted with a COVID-19 profile. This process was executed with the support of the ATLAS.ti version 8.0 computer program.

2.5. Rigour and quality criteria

To ensure the criteria of credibility, transferability and dependability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985, Graneheim and Lundman, 2004, Graneheim et al., 2017) a series of actions was carried out: 1) a protocol of a semi-structured interview to ask the same questions to all participants was used; 2) the selection of participants ensured proximity to the phenomenon studied and the wealth of information; 3) the context and characteristics of the participants were reported on in detail; 4) the presentation of the findings was accompanied by abundant quotes from the participants’ discourse; 5) the interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and returned to obtain confirmation by participants to ensure the accuracy of the recorded data; 6) the analysis was carried out independently by two researchers, and the entire research team participated in the consensus process, validating the results. A review system was established to allow the process to be replicated step by step. The execution and evaluation of the study were assessed with the COREQ qualitative design checklist (Tong et al., 2007).

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was submitted to the Studies Commission of the Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Spain for evaluation and authorisation. Informed consent was requested and participants were informed in writing. Confidentiality of the data and anonymity were ensured throughout the process by assigning each interview an alpha-numeric code, in compliance with Organic Law 3/2018 on the protection of personal data.

3. Findings

The participants were 22 nursing students between the ages of 20 and 30, the average being 23 years. The group was composed of 19 women (86.4%) and 3 men (13.6%). The majority of the students—18 out of 22 (81.8%)—had studied secondary education, and 36.3% have experience in the health field (8 of 22 students). The majority of the healthcare contracts (91%) were placed in hospitals (20 of 22 students), with only 9% (2 of 22 students) in nursing homes. The hospitalisation units were for COVID-19 patients and only 13.6% (3 of 22 students) worked in special care units. The work shifts were 12 h (day or night).

Results are presented following a structure that corresponds to the four themes and eleven sub-themes emerged in each of them (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Matrix of findings: themes and subthemes.

3.1. Theme 1. Professional preparation: identification of the competence balance and positive perception

First of all, it is important to note that most students felt prepared to start their career. During their education they had acquired the necessary competencies, technical skills, theoretical knowledge and attitudes:

“I think I am well-prepared,… the first days will always be harder because the whole hospital process is a bit hard… but I think that with the four years we have had enough but there will be a lot to learn.” P9

“… the truth is that I do feel prepared, we have all the necessary knowledge as the only thing we hadn't done yet were the placements, at the time of the pandemic we had passed all the theoretical courses…” P22

In contrast, only a minority felt prepared to face the COVID-19 crisis, although all were aware that, due to their contract type, they did not have full responsibility for patient care, and that their interventions were delegated by expert nurses:

“This situation is so new and so different…. When I got there the first day and saw the scope… I didn´t feel at all prepared to face it, but luckily I always had the nurse to help me.” P4

In this sense, they recognised the problems with transferring these competencies into the context of a pandemic, especially during the first two weeks, which were the hardest ones, as they coincided with the peak of the pandemic and with maximum pressure on the healthcare system:

“… the first 10-15 days were the hardest because of a lack of management, I mean, we didn´t know how to manage the situation…” P11

This perception of minor preparation is articulated around three reasons. First, being in an extreme emergency that compromised the safety of patients and nurses, while it was unpredictable and generated extremely complex situations:

“I believe that nobody is prepared, neither professionally, emotionally nor at any level. no one has trained you for a pandemic, no one has explained it to you. there is insufficient research.” P12

Second, the idea of having some capacities still in the development process, such as assuming the responsibility of caring for a COVID-19 patient, the ability to work under pressure, or the need for diligent adaptation to unusual circumstances:

“This support work we are doing I can do, but I don´t feel prepared to take care of COVID-19 patients, I mean take care of them with absolute responsibility.” P5

Third, some students expressed their lack of experience upon entering the world of work:

“I think the first day on the job, without experience, demands respect, even more so in a pandemic.” P10

3.2. Theme 2. Received education: effective learning and required training

Of the curricular learning developed, the education received in three types of courses stood out: clinical practice placement; basic courses such as anatomy and physiology; and clinical nursing courses, dealing with topics such as medication administration and isolation management:

“All that you have studied for four years was valuable and you know how to use it, you understand the patient and how they react… you can relate the anatomy or physiology to the clinical courses… I can understand why a patient is saturated at 89, or why … So I do feel prepared.” P13

When students joined the healthcare centres they received basic information, but they lacked training on security and protection measures for the professionals, the patients, and environment management:

“We didn’t receive any training, so my first day was to find out how everything worked; there was only one person who had started working from the beginning with everything in the COVID unit, and she was telling us how to place PPE…” P19

They highlight the importance of experience and vocational training in order to face the high complexity of care in the context of COVID-19:

“It is a profession that slowly molds you and provides you with experience and diverse knowledge to be able to respond to anything… I see the nurses as warriors, they are prepared and have sufficient weapons to face whatever, despite the complexity of the situation.” P18

Students described the expansion of psychological knowledge in terms of people’s mental and behavioural processes and their interactions with the physical and social environment as necessary education for facing this situation. Also mentioned are areas such as emotional management and stress, resilience, the therapeutic relationship and bad news communication:

“But,. emotional management, psychological management should have much more importance. Not just for the patient, but yours? As a professional? At the end, managing that moment of stress, managing anxiety, managing the uncertainty that is stirred up every day…” P12.

They highlighted the need to go deeper into subjects such as physiopathology and specifically infectious and respiratory diseases, as well as clinical courses on nursing care and in palliative care areas, especially grief and pain management:

“I think it is important to talk about the topic of the end-of-life situation… I had luckily taken an elective course about palliative care.” P11

3.3. Theme 3. The nurse in front of COVID-19: nursing skills, therapeutic context changes, professional values and situational impact

From the perspective of the students, the role of care nurses in COVID-19 units is distributed between the recognition of competencies that determine their role and a series of values that are intensified given the specific characteristics of the context. Among all the perceived nursing competencies, teamwork stands out:

“… within the misfortune and the situation, I find that we are having the benefit of working much more as a team… more solidarity, more team among professionals…” P18

Furthermore, the clinical evolution of the patients, which in some cases presented itself in a changeable and unexpected way, required the activation of leadership, adaptability and prioritisation skills:

“… in the management of work and tasks, now everything is emerging, and… to know how to prioritise which is more important, to know which task is more important and in which patient…” P2

According to the students, the acquisition of nurse autonomy within the healthcare team in relation to security issues and resource management and especially in the control, monitoring and care of COVID-19 patients, is emerging at this time. Another highlighted value is the rigorous and systematic attitude in the execution of nursing interventions:

“We actually see that nurses have an important role, and the nurses I have worked with, understand, and know how to manage, after all they are nurses with their own different specialities but now all part of a COVID team.” P3

Interpersonal skills that enhance close treatment, empathy and sensitivity are also emphasised:

“And sometimes a patient calls. (she says “I'm worried”), so they get dressed again and come back in, and they just stay there to talk to the patient.” P5

"It is true that nurses we have empathy towards patients. Well, I’ve always seen it, but now clearer.” P13

Therefore, students warn that keeping the patient company and active listening are essential:

“… when the patient smiles at you, when the patient is ill and by spending five more minutes with him. you calm him down, and take away the anxiety and fear of dying that he had.” P12

Changes were detected in the therapeutic context, specifically in the operation of the healthcare teams. Teams become more horizontal organisational structures:

“… the health team works better than I have ever seen, with people who treat each other really well and there is mutual respect and it is not vertical, the relationship is horizontal.” P11

Additionally, the healthcare context incorporated new figures with different roles: students as professionals and doctors outside their speciality. These healthcare teams, not being experts in the COVID-19 situation, were sometimes tense:

“… We are seeing surgeons; we are seeing other specialists, right? Who do not know how to manage these situations and it is normal. They get nervous, and the nursing team too…” P3

The professional values most appreciated in nurses was vocation, along with responsibility and respect. Vocation is the way in which values are expressed; it is the construction of a personal and social history:

“because the profession goes further and then it is like something innate in people that we like and that. is totally vocational, you get an inside strength to continue fighting and it is that. it does not matter that they are throwing stones at you or your heart is breaking inside you.” P21.

Other personal values identified were solidarity, human quality, empathy and sacrifice, and companionship had increased:

“…because the feeling that there is now in the hospital is different, it is companionship, it is even friendship, it is to work with someone you trust.” P22.

Negative implications are also reported due to the complex management and death of many patients. Sometimes the nurses were overwhelmed, worn out, and burned out, and they experienced psychological and physical implications caused by high levels of stress sustained in the work environment over a long time:

“They are very exhausted, because it is true that I know nurses who have come to work 12 days in a row, one day off and then another 7. And there are, there are many health workers on leave.” P20

Feelings of fear, worry, and tense situations of nervousness were often displayed. Some students worried about future disruptive effects:

“This is complicated… now we are all stressed… as long as there is stress, you work… when the peak goes down, it is when the problems really arise at the level of post-traumatic stress.” P1

3.4. Theme 4. Patient admitted with COVID-19: emotional control, family isolation and lack of communication

The main characteristics of patients in COVID-19 units have been their high dependence on and demand for nursing care:

“They are very demanding,… Now, in this situation they are alone, maybe they call to ask for a juice, but what they really want is the nurse to be with them.” P5

The patients’ perceived loss of security and mistrust, the need to feel protected, and feelings of vulnerability were so high that they generated a lot of fear and uncertainty about their own evolution. Their interaction with nursing staff showed the need to go beyond the physical part; it changed towards a more emotional interaction and more humanised assistance:

“The hospital ward where I am, I saw bad patients. they are isolated patients, who are obviously alone. So here is more emotional management.” P16

“Attempts are now being made to make room entries with minimal contact, if possible, for staff protection. But the humanitarian treatment, the positive caresses, the contact with the resident is the same, and it is very important, because they are old people, who are alone in the room, in isolation…” P8

Further aspects that hindered nurse-patient contact were the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), the difficulty of recognising nurses due to PPE, and the need to maintain an interpersonal distance:

“Well, I think the patient has a lot of anxiety, and a lot of worries because even if his condition is mild, when he sees the nurse come in with all the PPE, he is scared, and he thinks, and many have asked, am I going to die? Is my condition very serious?” P4

“Well, above all that you only see the patient when wearing the suit, the glasses, the screen, two times in one shift and the thing is that the patient doesn't know who you are, how you are, or what… I think everything is very cold and there's a lot of distance.” P4.

Family isolation was a trait also remarked on during the hospital stay. The patients lacked communication with the outside and inside world (within the centre where they were admitted). They verbalised the need to be informed. At first, the patients were always alone and died alone. Technology (mobiles, tablets) offered a real possibility of family communication and companionship, especially for the elderly because of their vulnerability, but also for all the people who suffered isolation from loved ones. Video calls were the only connection to the outside world:

“…especially with the elderly who we tried to help with the help of technology, we were able to bring them closer to the family through social networks or video calls.” P9

Lastly, it should be noted that the patients were very grateful to, and understanding with, the health personnel:

“Many patients have cried with joy, with gratitude to the staff. It's shocking, shocking, to see a patient who is infinitely grateful for everything we've done for him.” P11.

4. Discussion

In general, the students feel prepared for healthcare practice, but not in relation to the demands of COVID-19. In agreement with other studies, the need to carry out a formative approach to the management of infectious diseases is revealed, based not only on theoretical knowledge but also on personal resources, in the specific professional and situational context (Lam et al., 2018). Some nursing programmes based on self-directed learning in cases of epidemics such as Ebola, emphasise their effectiveness not only in increasing knowledge, but also in reducing fear and increasing confidence in the care of patients with infectious pathologies (Ferranti et al., 2016, McNiel and Elertson, 2017). Alternatively, knowledge that really allows a holistic approach to care is demanded, with knowledge patterns that generate a more personalised and intimate patient relationship (Vega and Rivera, 2009). Additionally, the students detailed that they sometimes did not receive training about protection measures or the management of patients with Covid-19 in the healthcare centres, which caused a feeling of insecurity. The elaboration, dissemination and preparation of training through protocols and care procedures are essential to develop a safe and effective clinical practice against COVID-19 (de Andrés-Gimeno et al., 2020). In line with other investigations in the context of outbreaks (Oh et al., 2017, Kam et al., 2020), experience and education are two relevant elements.

Beginning a nursing career in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis is an exceptional event. The students’ advanced beginner stage (being in the final year of their course), according to Benner's (2004) model, involves showing acceptable performance and being able to intuit significant elements of clinical practice. The COVID-19 situation has allowed the students and the healthcare team to introduce new care options and build them together. Sharing experiences with other professionals has allowed them to put new knowledge into practice and achieve a higher level of mastery and autonomy of their actions (Carrillo et al., 2018). Teamwork and values such as companionship have been a stimulus to understand and develop the practice more easily (Escobar-Castellanos and Jara Concha, 2019). The development of personal and interpersonal skills such as adaptability, leadership and ethical commitment has been promoted. The academic curriculum includes education in these aspects, but for true competence development, this knowledge must be mobilised in practice. The health crisis experienced by students fosters this professional development (Swift et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 crisis has precipitated a poorly organised transition of students to the professional world. However, for a good transition, a resource or model that promotes their emotional and social well-being is essential (Mellor and Gregoric, 2016). Kinghorn et al. (2017) show the need for a smooth transition and the need to receive formal and informal support for nurses in the process to avoid a negative emotional and physical impact.

It is important to note the differences between students during clinical practice placement and as auxiliary health staff. When students are on placements, they are fully supervised by a tutor and must demonstrate their knowledge, skills and attitudes (Swift et al., 2020). In Spain during the first outbreak of COVID-19, the students became entirely dependent on their employers, and the majority of the hours worked were not recognised as clinical practice placement. Our findings are consistent with other studies (Swift et al., 2020, Townsend, 2020), in which students faced an acute health reality that was totally different from the usual one. The situation offered benefits (a sense of usefulness, the development of skills such as working in a team and interpersonal relationships), but also involved risks (lack of education and training) and personal and professional drawbacks (complex emotional and professional management).

Thus, the relevant role of care in COVID-19-affected patients and the leadership exercised by nurses in healthcare have been recognised. As in other pandemic situations, nurses began to show rapid response capacity and provide reliable resources (Tsay et al., 2020). The students determined that despite the context of COVID-19, the nurses ensured quality and individualised care regardless of the patient's condition (Choi et al., 2020) and the risk of infection.

Students detail the high physical and emotional dependence of patients hospitalised with COVID-19, especially of those isolated. The lack of contact due to family isolation and the use of PPE must be compensated with the development of communication skills, and a focus on more personalised attention (Ulenaers et al., 2021). The best care for patients is based on maintaining the patient-nurse relationship and the values of nursing care (Casafont et al., 2021). Literature shows us that the experience of the students is ambivalent, with negative emotions such as fear and stress, but also positive experiences in terms of learning or feeling useful (Roca et al., 2021).

In this study and coinciding with other investigations (Pitt et al., 2014, Markey et al., 2021), nursing vocational values such as solidarity, resilience, human quality, empathy and sacrifice are recognised. The forced isolation to which patients were subjected is also addressed, as for security reasons they could not be accompanied by their families and friends. Nursing staff sought ways to make up for this phenomenon with technological devices such as phones and tablets. The use of these support elements was increased in end-of-life situations (Araujo Hernández et al., 2020). The psychological state of the patients, along with the emergency situation and the unknown conditions of the COVID-19 pathology, were the nurses’ main concerns (Sun et al., 2020).

Along the same lines as other studies (de Andrés-Gimeno et al., 2020, Luo et al., 2020), nurses felt anxiety, fear and other emotions due to the psychological impact; therefore, it is essential to have psychological support systems (World Health Organization, 2020). At the same time they not only received the support of the team and their colleagues, but also of the patients and other social support networks (Sun et al., 2020).

Finally, two essential elements are revealed in this study. First, the health system is under pressure and there is a need for resources and education, but it is evident that professionals are without a doubt the most valuable resource in healthcare (González-Castro et al., 2020). The work of professionals is irreplaceable in the fight against COVID-19 (Agazzi, 2020). Second, the responsibility for taking advantage of the opportunity to improve preparedness and response to international public health emergencies was already recognised in a previous PHEIC (Simón Soria, 2016).

5. Conclusions

Final year students assess their level of competence as positive and they feel prepared for care practice, although they demand more specific COVID-19 training. They recognise a high level of competence and autonomy of care nurses (within the care team and in direct care with patients). In addition, students highlight the importance of professional nursing values.

This situation was a learning opportunity, but it is essential to study this transition from beginners to the professional environment and its possible impact in more detail. Furthermore, the students were able to build knowledge in practice with the professionals themselves. These elements give value to the work carried out by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic, and help to rethink the nursing curriculum.

Finally, the isolation of patients limits their care. Thus, the clinical situation of a person admitted with COVID-19 is a determining factor in itself in the specific context of healthcare, in the uncertain and changing clinical evolution of some patients, and in the need to prioritise according to action criteria established in this state of pandemic.

6. Limitations

This study has some limitations. One is that it is only transferable to similar healthcare and university education contexts. A larger sample of participants from different educational backgrounds who have experienced the investigated phenomenon would reinforce the consistency of the present study. In relation to the context, the hospital centres were urban centres of large and medium populations, and rural healthcare aspects or community care were not addressed.

7. Implications for practice

This study can serve as a guide for curricular adaptations of nursing education and training in relation to aspects such as:

-

1.

Students demand more education and training on the subject of COVID-19: knowledge related to infectious disease; aspects of personal and professional safety, above all, elements that help to offer holistic care and more psychological and emotional training that allows for more humanised attention. Additionally, the development of personal resources that allow them to better cope with critical situations.

-

2.

The students were able to appreciate the great importance of skills such as adaptability, nursing leadership, teamwork and ethical commitment. Given their relevance, an effort should be made to enhance their development, both at an academic and a practical level.

-

3.

Based on the findings and the importance that the students give the development of professional values, they are essential for the personalised and quality care of patients during the pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Olga Canet: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. Teresa Botigué: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Ana Lavedán Santamaría: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Olga Masot: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Resources. Tània Cemeli Sánchez: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Translation. Judith Roca: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft.

Funding

This study was not financed.

Ethics

The Faculty of Nursing and Physiotherapy of the University of Lleida authorized this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have not manifested any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give special thanks to the nursing students who took part in the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103072.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- Agazzi E. A systemic approach to bioethics. Bioeth. Update. 2020;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bioet.2020.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Andrés-Gimeno B. Nursing care for hospitalized patients in COVID-19 units. Enferm. Clín. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo Hernández M., García-Navarro S., García-Navarro B. Approaching grief and death in family members of patients with COVID-19: narrative review. Enferm. Clín. 2020;31:s112–s116. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbeláez M., Onrubia J. Bibliometric and content analysis. Two complementary methodologies for the analysis of the colombian magazine ‘education and culture’. Rev. Investig. UCM. 2014;14(23):14–31. doi: 10.22383/ri.v14i1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benner P. Using the Dreyfus Model of skill acquisition to describe and interpret skill acquisition and clinical judgment in nursing practice and education. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2004;24(3):188–199. doi: 10.1177/0270467604265061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berenguera, A. et al., 2014. Escuchar, observar y comprender. Recuperando la narrativa en las Ciencias de la Salud. Aportaciones de la investigación cualitativa. 1st ed., Barcelona: Institut Universitari d′Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol (IDIAP J. Gol).

- Carrillo A., Matínez P., Taborda S. Application of Patricia Benner’s philosophy in nursing training. Rev. Cuba. Enferm. 2018;34(2) http://revenfermeria.sld.cu/index.php/enf/article/view/1522/358 [Google Scholar]

- Casafont C., Fabrellas N., Rivera P., Olivé-Ferrer M.C., Querol E., Venturas M., Prats J., Cuzco C., Frías C.E., Pérez-Ortega S., Zabalegui A. Experiences of nursing students as healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a phemonenological research study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;97 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Gasch A., González-Chordá V., Mena-Tudela D. COVID-19: are Spanish medicine and nursing students prepared? Nurse Educ. Today. 2020;92 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charette M., Goudreau J., Bourbonnais A. Nurse education today how do new graduated nurses from a competency-based program demonstrate their competencies ? A focused ethnography of acute care settings. Nurse Educ. Today. 2019;79:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.R., Jeffers K.S., Logsdon M.C. Nursing and the novel coronavirus: Risks and responsibilities in a global outbreak. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020;76(7):1486–1487. doi: 10.1111/jan.14369. Available at: https://10.1111/jan.14369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Boira E.J., Ruiz-Palomino E., Salas-Media P., Folch-Ayora A., Muriach M., Baliño P. “The COVID-19 outbreak”-an empirical phenomenological study on perceptions and psychosocial considerations surrounding the immediate incorporation of final-year Spanish nursing and medical students into the health system. Nurse Educ. Today. 2020;92 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corless I.B., Nardi D., Milstead J.A., Larson E., Nokes K.M., Orsega S., Kurth A.E., Kirksey K.M., Woith W. Expanding nursing’s role in responding to global pandemics 5/14/2018. Nurs. Outlook. 2018;66(4):412–415. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran M. Marco epistemológico de la enfermería. Aquichan. 2002;2(1):07–18. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Castellanos B., Jara Concha P. Philosophy of Patricia Benner, application in nursing training: proposals of learning strategies. Educación. 2019;28(54):182–202. doi: 10.18800/educacion.201901.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union Directiva 2013/39/CE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 20 de noviembre de 2013. D. Of. Comunidades Eur. 2013;L354:132–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ferranti E.P., Wands L., Yeager K.A., Baker B., Higgins M.K., Wold J.L., Dunbar S.B. Implementation of an educational program for nursing students amidst the Ebola virus disease epidemic. Nurs. Outlook. 2016;64(6):597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Castro A., Escudero-Acha P., Peñasco Y. Healthcare workers from COVID-19 matters too much. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2020;35(5):331–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jhqr.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U., Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U., Lindgren B., Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaihlanen A.-M., Haavisto E., Strandell-Laine C., Salminen L. Facilitating the transition from a nursing student to a registered nurse in the final clinical practicum: a scoping literature review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018;32(2):466–477. doi: 10.1111/scs.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam J.K., Chan E., Lee A., Wei V.W., Kwok K.O., Lui D., Yuen R.K. Student nurses’ ethical views on responses to the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Nurs. Ethics. 2020;27(4):924–934. doi: 10.1177/0969733019895804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn G.R., Halcomb E.J., Froggatt T., Thomas S.D. Transitioning into new clinical areas of practice: An integrative review of the literature. J. Clinical Nurs. 2017;26(23–24):4223–4233. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S., Kwong E., Hung M., Pang S., Chiang V. Nurses’ preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks: a literature review and narrative synthesis of qualitative evidence. J. Clinical Nurs. 2018;27(7–8):e1244–e1255. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y., Guba E. SAGE Publications; Newbury Park, London; New Delhi: 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- Luciani M., et al. How to design a qualitative health research study. Part 1: design and purposeful sampling considerations Come Disegnare uno Studio di Ricerca Sanitaria Qualitativa. Prof. Inferm. 2019;72(2):152–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey K., Ventura C., Donnell C.O., Doody O. Cultivating ethical leadership in the recovery of COVID-19. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021;29(2):351–355. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiel P.L., Elertson K.M. Reality check: preparing nursing students to respond to ebola and other infectious diseases. Innov. Cent. 2017;38(1):42–43. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor P., Gregoric C. Ways of being: preparing nursing students for transition to professional practice. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2016;47(7):330–340. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20160616-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de la Presidencia Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria democrática, 2020. Real Decreto 463/2020 de 14 de marzo por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19, Spain. https://boe.es/boe/dias/2020/03/14/.

- Ministerio de Sanidad & Gobierno de España, 2020b. Valoración de la declaración del brote de nuevo coronavirus 2019 (n-CoV) una Emergencia de Salud Pública de Importancia Internacional (ESPII).

- Ministerio de Sanidad & Gobierno de España, 2020a. Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE) 4/2015. Orden SND/232/2020, de 15 de marzo, por la que se adoptan medidas en materia de recursos humanos y medios para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 68(sec. I), pp. 61561–61567.

- Modi P.D., Nair G., Uppe A., Modi J., Tuppekar B., Gharpure A.S., Langade D. COVID-19 awareness among healthcare students and professionals in Mumbai metropolitan region: a questionnaire-based survey. Cureus. 2020;12(4):7514. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogashoa T. Applicability of constructivist theory in qualitative educational research. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2014;4(7):51–59. (Available at: https://doi.org/) [Google Scholar]

- Oh N., Hong N., Ryu D.H., Bae S.G., Kam S., Kim K.Y. Exploring nursing intention, stress, and professionalism in response to infectious disease emergencies: the experience of local public hospital nurses during the 2015 MERS outbreak in South Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. 2017;11(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt V., Powis D., Levett-Jones T., Hunter S. Nursing students’ personal qualities: a descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2014;34(9):1196–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca J., Canet-Vélez O., Cemeli T., Lavedán A., Masot O., Botigué T. Experiences, emotional responses, and coping skills of nursing students as auxiliary health workers during the peak COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1111/inm.12858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Decree 1125/2003, de 5 de septiembre, por el que se establece el sistema europeo de créditos y el sistema de calificaciones en las titulaciones universitarias de carácter oficial y validez en todo el territorio nacional. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 224, pp. 34355–34356. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2003/09/05/1125.

- Ruiz Olabuénaga J.I. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. fifth ed. Universidad de Deusto; Bilbao: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simón Soria F. Public Health Emergencies of International Concern. An opportunity to improve global health security. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2016;34(4):219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N., Wei L., Shi S., Jiao D., Song R., Ma L., Wang H., Wang C., Wang Z., You Y., Liu S., Wang H. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020;48(6):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift A., Banks L., Baleswaran A., Cooke N., Little C., McGrath L., Meechan-Rogers R., Neve A., Rees H., Tomlinson A., Williams G. COVID-19 and student nurses: a view from England. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020;29(17–18):3111–3114. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend M.J. Learning to nurse during the pandemic: a student’s reflections. Br. J. Nurs. 2020;29(16):972–973. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.16.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay S.-F., Kao C.C., Wang H.H., Lin C.C. Nursing’s response to COVID-19: Lessons learned from SARS in Taiwan. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulenaers D., Grosemans J., Schrooten W., Bergs J. Clinical placement experience of nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;99 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega P., Rivera M. Holistic care, myth or reality? Horiz. Enferm. 2009;20:81–86. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Weis P., Li S.-T.T. Leading change to address the needs and well-being of trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad. Pediatr. 2020;20(6):735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf?sfvrsn=6d3578af_2.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material