Abstract

The number of patients with multiple primary lung cancers (MPLC) is rising. We studied the clinical features and factors related to outcomes of MPLC patients using the database of surgically resected lung cancer (LC) cases compiled by the Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry. From the 18 978 registered cases, 9689 patients with clinical stage I non‐small‐cell lung cancer who achieved complete resection were extracted. Tumors were defined as synchronous MPLC when multiple LC was simultaneously resected or treatment was carried out within 2 years after the initial surgery; metachronous MPLC was defined as second LC treated more than 2 years after the initial surgery. Of these cases, 579 (6.0%) were synchronous MPLC and 477 (5.0%) metachronous MPLC, with 51 overlapping cases. Female sex, nonsmoker, low consolidation‐tumor ratio (CTR), and adenocarcinoma were significantly more frequent in the synchronous MPLC group, whereas patients with metachronous MPLC had higher frequencies of male sex, smoker, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and nonadenocarcinoma. There was no significant difference in survival rate between patients with and without synchronous or metachronous MPLC. Age, gender, CTR for second LC, and histological combination of primary and second LC were prognostic indicators for both types of MPLC. Logistic regression analysis showed that female sex, history of malignant disease other than LC, and COPD were risk factors for MPLC incidence. The present findings could have major implications regarding MPLC diagnosis and identification of independent prognostic factors, and provide valuable information for postoperative management of patients with MPLC.

Keywords: metachronous multiple primary lung cancer, non‐small‐cell lung cancer, registry, surgery, synchronous multiple primary lung cancer

This study determined the clinical features and outcomes of synchronous and metachronous multiple primary lung cancer. This information could have major implications regarding diagnosis and identification of independent prognostic factors, and provide valuable information for postoperative management of patients with multiple primary lung cancer.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CT

computed tomography

- CTR

consolidation‐tumor ratio

- IP

interstitial pneumonia

- IPM

intrapulmonary metastasis

- JJCLCR

Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry

- LC

lung cancer

- MPLC

multiple primary lung cancer

- NSCLC

non‐small‐cell lung cancer

- PS

performance status

- SPLC

solitary primary lung cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide. 1 With the soaring incidence of LC, the number of patients diagnosed with MPLC is also rising. 2 , 3 There are two subsets of patients with MPLC, referred to as synchronous MPLC and metachronous MPLC according to the time of occurrence of foci. The rate of synchronous MPLC ranges from 0.2% to 8% and is increasing because of the widespread use of multislice spiral CT. 4 After or during treatment for LC, patients could develop a second primary LC, namely metachronous MPLC. 5 It is estimated that between 4% and 10% of patients with LC subsequently have metachronous MPLC. 6 , 7

Although surgical resection becomes necessary to prolong patients’ survival, controversies related to diagnosis, patient selection, treatment, and outcomes still exist. 8 Although surgery offers the best chance for potential cure of MPLC and provides the most sufficient samples for diagnosis, 9 the prognosis of MPLC after surgery has not been studied in detail. In this study, the aim was to identify factors related to MPLC treatment outcomes, as well as the clinical features of affected patients, using the database of cases of surgically resected NSCLC cases in the year 2010 compiled by the JJCLCR.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A nationwide retrospective registry study of patients with primary LC who underwent pulmonary resection in 2010 was carried out by the JJCLCR in 2016. 10 The registry followed the ethical guidelines for epidemiologic studies was approved by the review board of Osaka University Hospital (approval no. 15321). The registry and the retrospective study using the registered data were also approved by each institutional review board of all participating institutions. The committee registered 18 973 patients from 297 hospitals. The registry data included the basic background characteristics of patients, tumor size (total and consolidation sizes) and other clinical T, N, and M descriptors in the 8th edition, surgery and intraoperative information, pathological T, N, and M descriptors in the 7th edition, survival data, and information regarding recurrent disease, as well as regarding resected synchronous MPLC and treated metachronous MPLC. The patients with MPLC were classified and registered using the following criteria basically according to the previous reports 11 , 12 : (i) tumors with different histology or subtypes; (ii) tumors with the same histology without distant or mediastinal lymph node metastasis; and (iii) tumors with the same histology and different molecular genetic characteristics. In the registry database, MPLC patient data were registered as synchronous resection of MPLC or metachronous treatment of MPLC, thus we could not clarify whether metachronous treated MPLC was present when the primary LC was resected and defined MPLC according to the following criteria. Tumors were defined as synchronous MPLC when multiple LC was simultaneously resected or treated within 2 years after the initial surgery, or as metachronous MPLC when the second LC was separately treated more than 2 years after the initial surgery. The database of surgically resected LC cases was searched to obtain data for patients with c‐Stage IA1, IA2, IA3, and IB NSCLC in whom R0 resection was achieved. In our database, patients with pTx or Nx or Mx were classified into undetermined p‐Stage. Those who underwent preoperative induction therapy, those with an LC history, and those with small cell LC were excluded. Of the 18 978 registered LC cases, 9689 were extracted and analyzed. Of those, 579 (6.0%) were synchronous MPLC and 477 (5.0%) metachronous MPLC during the period of observation, with 51 overlapping cases (Figure S1). The median follow‐up period after surgery in censored patients was 66 months (25th‐75th percentile, 58‐72 months).

Clinicopathologic factors associated with NSCLC with synchronous MPLC and metachronous MPLC were evaluated to identify prognostic indicators related to outcome. Potential risk factors for MPLC, including gender, malignant disease other than LC, diabetes, COPD, IP, smoking history, CTR on chest CT, histology of primary LC, and carcinoembryonic antigen level, were noted and then compared between patients with and without MPLC. These variables were then subjected to logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors.

The descriptive statistics used included medians and ranges for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables, which were compared using Wilcoxon tests and χ2 tests, respectively. Unreported patient data were treated as missing values. Overall survival curves were estimated according to the Kaplan‐Meier method, and differences in survival were tested using the log‐rank method. Univariate and multivariate analyses for prognostic factors were carried out using Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios and 95% CIs. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% CIs and define significant factors associated with the presence of MPLC. A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Synchronous MPLC

The characteristics of patients with synchronous MPLC were compared to those with SPLC (Table 1). Female gender and nonsmoker status were significantly more frequent in the synchronous MPLC group, and lower frequencies of comorbidity, such as COPD or IP, were noted in that group. Primary LC tumor consolidation size and CTR shown by CT were also significantly lower in the MPLC group, thus c‐Stage in patients with synchronous MPLC was lower than in those with SPLC. Regarding the pathological diagnosis of primary LC, adenocarcinoma was the more predominant histological type in MPLC patients. Furthermore, patients with synchronous MPLC more often underwent metachronous treatment for LC. Of the 579 patients with synchronous MPLC, 555 underwent simultaneous resection of MPLC and 24 received treatment for MPLC within 2 years after the initial surgery. Detailed analysis of the characteristics of cases of MPLC resected simultaneously with primary LC showed adenocarcinoma along with the same histology of primary LC and second LC to be the predominant histological combination in that group (Table S1). Contralateral resection was simultaneously carried out in 52 (9.4%) patients. Wedge resection was frequently undertaken for second LC as an additional procedure. The mean CTR of second LC in chest CT findings was 0.42, and preinvasive LC or adenocarcinoma was the more predominant histological type in second LC; thus, the predominant histological combination for patients with synchronous MPLC was adenocarcinoma‐adenocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma‐preinvasive LC. The characteristics of metachronous MPLC cases treated within 2 years after primary LC surgery also showed adenocarcinoma along with the same histology of primary and second LC to be the predominant histological combination (Table S2). Contralateral resection was carried out in 22 (91.7%) patients and a lobectomy in 13 (54.2%).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with and without synchronous multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC)

| SPLC, n = 9110 | (%) | Synchronous MPLC, n = 579 | (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 5405 | 59.3 | 266 | 45.9 | <.001 |

| Female | 3702 | 40.6 | 313 | 54.1 | |

| Age (years) | 68.7 ± 9.4 | — | 69.2 ± 8.7 | — | .228 |

| Smoking history | |||||

| No | 3522 | 38.7 | 273 | 47.2 | |

| Yes | 5394 | 59.2 | 289 | 49.9 | <.001 |

| Unknown | 191 | 2.1 | 17 | 2.9 | |

| Brinkman index | 1002 ± 653 | — | 934 ± 684 | — | .086 |

| Body mass index | 22.6 ± 3.3 | — | 22.5 ± 3.1 | — | .651 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 7866 | 86.3 | 503 | 86.9 | .802 |

| Yes | 1241 | 13.6 | 76 | 13.1 | |

| COPD | |||||

| No | 7829 | 85.9 | 522 | 90.2 | .004 |

| Yes | 1278 | 14.0 | 57 | 9.8 | |

| Interstitial pneumonia | |||||

| No | 8710 | 95.6 | 569 | 98.3 | .001 |

| Yes | 397 | 4.4 | 10 | 1.7 | |

| Malignant disease other than LC | |||||

| No | 7354 | 80.7 | 449 | 77.5 | .065 |

| Yes | 1753 | 19.2 | 130 | 22.5 | |

| %VC | 107 ± 18 | — | 110 ± 17 | — | <.001 |

| FEV1% | 73.5 ± 10.5 | — | 74.6 ± 9.5 | — | .013 |

| CEA (mg/mL) | 5.1 ± 9.4 | — | 4.8 ± 7.6 | — | .413 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.3 ± 0.9 | — | 2.3 ± 0.9 | — | .564 |

| Consolidation size (cm) | 1.9 ± 0.9 | — | 1.8 ± 1.0 | — | <.001 |

| CTR | 0.84 ± 0.25 | — | 0.77 ± 0.28 | — | <.001 |

| CTR (category) | |||||

| ≤0.5 | 1402 | 15.4 | 134 | 23.1 | <.001 |

| >0.5 | 7705 | 84.6 | 445 | 76.9 | |

| c‐Stage | |||||

| IA1 | 1804 | 19.8 | 157 | 27.1 | <.001 |

| IA2 | 3172 | 34.8 | 198 | 34.2 | |

| IA3 | 2262 | 24.8 | 123 | 21.2 | |

| IB | 1869 | 20.5 | 101 | 17.4 | |

| Surgical procedure | |||||

| ≥Lobectomy | 7150 | 78.5 | 401 | 69.3 | |

| Sublobar resection | 1952 | 21.4 | 178 | 30.7 | <.001 |

| Others | 5 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| p‐Stage | |||||

| I | 6847 | 75.2 | 428 | 73.9 | .073 |

| II | 717 | 7.9 | 39 | 6.7 | |

| III | 587 | 6.4 | 32 | 5.5 | |

| Undetermined | 956 | 10.5 | 80 | 13.8 | |

| Histology of primary LC | |||||

| Squamous | 1589 | 17.4 | 45 | 7.8 | <.001 |

| Adeno | 7104 | 78.0 | 512 | 88.4 | |

| Large | 248 | 2.7 | 11 | 1.9 | |

| Adenosquamous | 166 | 1.8 | 11 | 1.9 | |

| Histology of primary LC (category) | |||||

| Adeno | 7104 | 78.0 | 512 | 88.4 | <.001 |

| Non‐adeno | 2006 | 22.0 | 67 | 11.6 | |

| Metachronous MPLC | |||||

| No | 8681 | 95.3 | 528 | 91.2 | <.001 |

| Yes | 426 | 4.7 | 51 | 8.8 | |

Abbreviations: Adeno, adenocarcinoma; Adenosquamous, adenosquamous carcinoma; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTR, consolidation‐tumor ratio; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; Large, large cell carcinoma; LC, lung cancer; MPLC, multiple primary lung cancer; SPLC, solitary primary lung cancer; Squamous, squamous cell carcinoma; VC, vital capacity.

The results of continuous variables represent the mean ± SD.

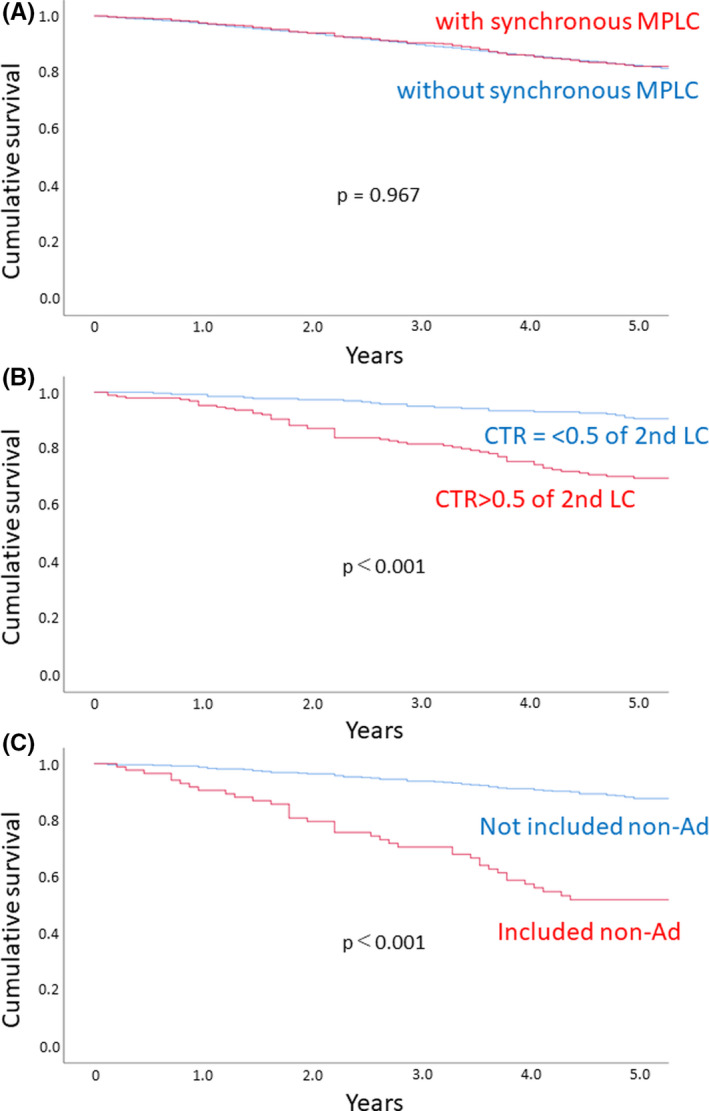

Although there was no significant difference in survival rates between patients with and without synchronous MPLC (Figure 1A), univariate analysis showed age, gender, c‐Stage, CTR for primary and second LC, histology of primary LC or second LC, p‐Stage, and the histological combination of primary LC and second LC as prognostic indicators for synchronous MPLC cases (Table 2). Multivariate analysis revealed that gender, CTR for second LC, and the histological combination of primary LC and second LC were independent prognostic indicators. When analyzing specific factors for MPLC, patients with higher CTR for second LC and histological type of primary LC or second LC including nonadenocarcinoma had a worse prognosis (Figure 1B,C).

FIGURE 1.

A, Survival curves for patients with (red) and without (blue) synchronous multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC). Overall survival curves were estimated according to the Kaplan‐Meier method, and differences in survival were tested using the log rank method. B, Survival curves for patients with synchronous MPLC according to the consolidation‐tumor ratio (CTR) of the second lung cancer (LC). Red, CTR > 0.5; blue, CTR ≤ 0.5. C, Survival curves for patients with synchronous MPLC according to histological combination of primary and second LC. Red, histological combination without nonadenocarcinoma (non‐Ad); blue, histological combination including non‐Ad

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of patients with synchronous multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HR | 95% CI | P value | N | HR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤70 | 313 | 1 | — | — | .009 | 265 | 1 | — | — | .024 |

| >70 | 266 | 1.647 | 1.130 | 2.400 | 204 | 1.630 | 1.067 | 2.489 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 266 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 209 | 1 | — | — | <.001 |

| Female | 313 | 0.252 | 0.164 | 0.387 | 260 | 0.336 | 0.206 | 0.548 | ||

| c‐Stage | ||||||||||

| IA1 | 157 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IA2 | 198 | 1.857 | 1.025 | 3.365 | .041 | — | — | — | — | — |

| IA3 | 123 | 3.170 | 1.749 | 5.743 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | — |

| IB | 101 | 3.023 | 1.621 | 5.636 | .001 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CTR of primary LC | ||||||||||

| ≤0.5 | 134 | 1 | — | — | .001 | 109 | 1 | — | — | .216 |

| >0.5 | 445 | 2.802 | 1.538 | 5.103 | 360 | 1.553 | 0.773 | 3.121 | ||

| Procedure for primary LC | ||||||||||

| Limited resection | 178 | 1 | — | — | .199 | — | — | — | — | — |

| ≥Lobectomy | 401 | 0.774 | 0.524 | 1.144 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Primary LC | ||||||||||

| Ad | 512 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Non‐Ad | 67 | 4.215 | 2.776 | 6.400 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| p‐Stage | ||||||||||

| I | 428 | 1 | — | — | — | 344 | 1 | — | — | — |

| II | 39 | 1.963 | 1.038 | 3.715 | .038 | 31 | 1.404 | 0.684 | 2.883 | .355 |

| III | 32 | 2.874 | 1.555 | 5.311 | .001 | 29 | 1.880 | 0.974 | 3.662 | .060 |

| Undetermined | 80 | 1.645 | 0.989 | 2.737 | .055 | 65 | 1.354 | 0.760 | 2.412 | .304 |

| Histology of 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| Pre | 93 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ad | 427 | 1.250 | 0.692 | 2.258 | .459 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Non‐Ad | 55 | 4.492 | 2.284 | 8.837 | <.001 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CTR of 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| ≤0.5 | 273 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 109 | 1 | — | — | .009 |

| >0.5 | 197 | 3.295 | 2.121 | 5.118 | 360 | 1.934 | 1.178 | 3.176 | ||

| Histology combination of primary LC and 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| Not included non‐Ad | 487 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 403 | 1 | — | — | .008 |

| Included non‐Ad | 88 | 4.444 | 2.995 | 6.595 | — | 66 | 1.933 | 1.186 | 3.152 | |

| Number of synchronous MPLCs | ||||||||||

| 1 | 456 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | 66 | 1.394 | 0.815 | 2.386 | .233 | — | — | — | — | — |

| ≥3 | 33 | 0.819 | 0.332 | 2.023 | .665 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Resected within 2 y | 24 | 2.611 | 1.310 | 5.205 | .006 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Metachronous LC | ||||||||||

| No | 528 | 1 | — | — | .547 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 51 | 0.811 | 0.410 | 1.604 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviations: Ad, adenocarcinoma; CI, confidence interval; CTR, consolidation‐tumor ratio; HR, hazard ratio; LC, lung cancer; Pre, preinvasive lesion.

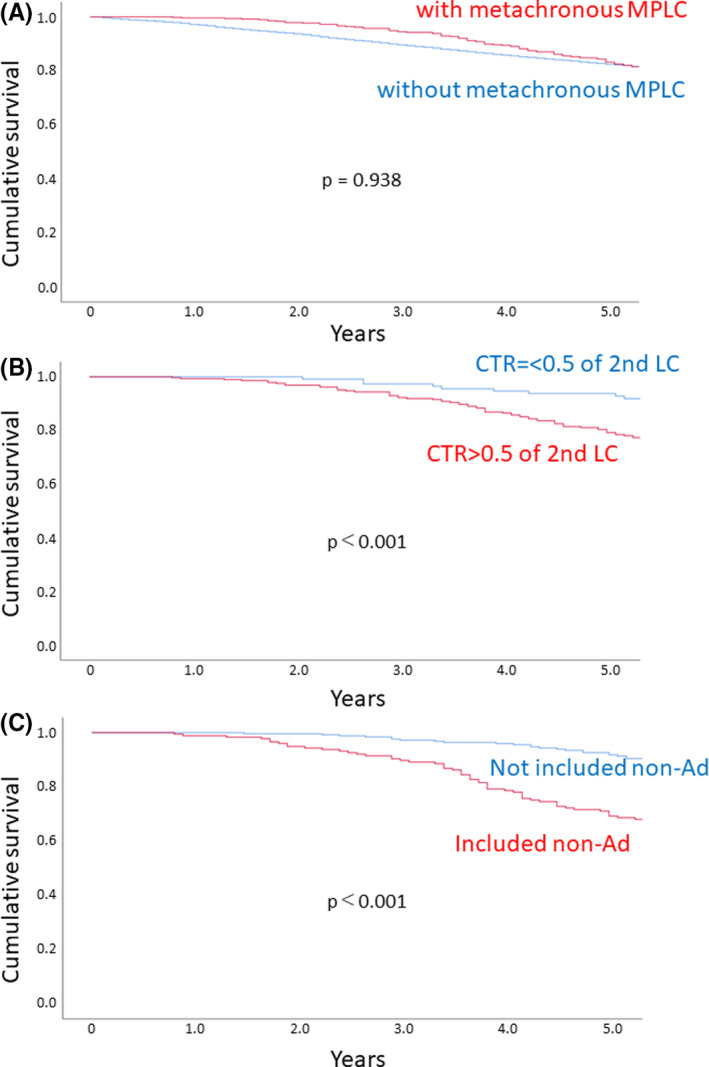

3.2. Metachronous MPLC

Characteristics were also compared between patients with and without metachronous treatment for MPLC (Table 3), which showed higher frequencies of male patients, smokers, comorbidities such as COPD, IP, nonadenocarcinoma, and resection for synchronous LC in the MPLC group. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second was lower and a sublobar resection was more frequently carried out for primary LC in metachronous MPLC patients compared to patients without MPLC. The predominant metachronous treatment for patients with MPLC was surgery, with a wedge resection or segmentectomy carried out frequently for second LC (Table S3). Although contralateral MPLC was more frequent, 76 of the 338 MPLC patients underwent surgery for ipsilateral metachronous treatment. The predominant histological combination for patients with metachronous MPLC was adenocarcinoma‐adenocarcinoma. There was no significant difference regarding survival rate between patients with and without metachronous MPLC (Figure 2A). Similar to the synchronous MPLC, the CTR value for second LC and their histological combination were prognostic indicators for patients with metachronous treatment for MPLC (Figure 2B,C). Multivariate analysis revealed that age, gender, and the histological combination of primary LC and second LC were independent prognostic indicators (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of patients with and without metachronous multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC)

| Non‐metachronous LC, n = 9209 | (%) | Metachronous MPLC, n = 477 | (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 5356 | 58.2 | 315 | 66.0 | .001 |

| Female | 3853 | 41.8 | 162 | 34.0 | |

| Age | 68.7 ± 9.4 | — | 69.6 ± 8.3 | — | .018 |

| Smoking history | |||||

| No | 3653 | 39.7 | 142 | 29.8 | |

| Yes | 5351 | 58.1 | 332 | 69.6 | <.001 |

| Unknown | 205 | 2.2 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Brinkman index | 994 ± 656 | — | 1067 ± 628 | — | .050 |

| Body mass index | 22.6 ± 3.3 | — | 22.4 ± 3.2 | — | .327 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 7972 | 86.6 | 397 | 83.2 | .040 |

| Yes | 1237 | 13.4 | 80 | 16.8 | |

| COPD | |||||

| No | 7974 | 86.6 | 377 | 79.0 | <.001 |

| Yes | 1235 | 13.4 | 100 | 21.0 | |

| Interstitial pneumonia | |||||

| No | 8833 | 95.9 | 446 | 93.5 | .014 |

| Yes | 376 | 4.1 | 31 | 6.5 | |

| Malignant disease other than LC | |||||

| No | 7436 | 80.7 | 367 | 76.9 | .044 |

| Yes | 1773 | 19.3 | 110 | 23.1 | |

| %VC | 107 ± 18 | — | 108 ± 18 | — | .155 |

| FEV1% | 73.7 ± 10.4 | — | 71.0 ± 10.9 | — | <.001 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 5.1 ± 9.4 | — | 5.1 ± 7.8 | — | .891 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.3 ± 0.91 | — | 2.4 ± 0.91 | — | .110 |

| Consolidation size (cm) | 1.9 ± 0.95 | — | 2.0 ± 0.91 | — | .052 |

| CTR | 0.83 ± 0.26 | — | 0.85 ± 0.24 | — | .058 |

| CTR (category) | |||||

| ≤ 0.5 | 1475 | 16.0 | 61 | 12.8 | .062 |

| > 0.5 | 7734 | 84.0 | 416 | 87.2 | |

| c‐Stage | |||||

| IA1 | 1884 | 20.5 | 77 | 16.1 | .007 |

| IA2 | 3210 | 34.9 | 160 | 33.5 | |

| IA3 | 2238 | 24.3 | 147 | 30.8 | |

| IB | 1877 | 20.4 | 93 | 19.5 | |

| Procedure for primary LC | |||||

| ≥Lobectomy | 7217 | 78.4 | 334 | 70.0 | — |

| Sublobar resection | 1987 | 21.6 | 143 | 30.0 | <.001 |

| Others | 5 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| p‐Stage | |||||

| I | 6925 | 75.2 | 350 | 73.4 | .001 |

| II | 719 | 7.8 | 37 | 7.8 | |

| III | 602 | 6.5 | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Undetermined | 963 | 10.5 | 73 | 15.3 | |

| Histology of primary LC | |||||

| Squamous | 1526 | 16.6 | 108 | 22.6 | .004 |

| Adeno | 7267 | 78.9 | 349 | 73.2 | |

| Large | 244 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.1 | |

| Adenosquamous | 172 | 1.9 | 5 | 1.0 | |

| Histology of primary LC (category) | |||||

| Adeno | 7267 | 78.9 | 349 | 73.2 | .003 |

| Non‐Adeno | 1942 | 21.1 | 128 | 26.8 | |

| Synchronous MPLC | |||||

| No | 8681 | 94.3 | 426 | 89.3 | <.001 |

| Yes | 528 | 5.7 | 51 | 10.7 | |

Abbreviations: Adeno, adenocarcinoma; Adenosquamous, adenosquamous carcinoma; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTR, consolidation‐tumor ratio; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; Large, large cell carcinoma; LC, lung cancer; Squamous, squamous cell carcinoma; VC, vital capacity.

The results of continuous variables represent the mean ± SD.

FIGURE 2.

A, Survival curves for patients with (red) and without (blue) metachronous multiple primary lung cancers (MPLC). B, Survival curves for patients with metachronous MPLC according to the consolidation‐tumor ratio (CTR) of the second lung cancer (LC). Red, CTR > 0.5; blue, CTR ≤ 0.5. C, Survival curves for patients with metachronous treatment for MPLC according to the histological combination of primary and second LC. Red, histological combination without nonadenocarcinoma (non‐Ad); blue, histological combination including non‐Ad

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of patients with metachronous multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HR | 95% CI | P value | N | HR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤70 | 242 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 190 | 1 | — | — | <.001 |

| >70 | 235 | 2.682 | 1.764 | 4.078 | 182 | 2.355 | 1.466 | 3.782 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 315 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 241 | 1 | — | — | .026 |

| Female | 162 | 0.284 | 0.156 | 0.482 | 131 | 0.465 | 0.237 | 0.912 | ||

| c‐Stage | ||||||||||

| IA1 | 77 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| IA2 | 160 | 1.431 | 0.762 | 2.687 | .264 | — | — | — | — | — |

| IA3 | 147 | 1.338 | 0.702 | 2.550 | .376 | — | — | — | — | — |

| IB | 93 | 1.222 | 0.603 | 2.474 | .578 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CTR of primary LC | ||||||||||

| ≤0.5 | 61 | 1 | — | — | .014 | 55 | 1 | — | — | .284 |

| >0.5 | 416 | 3.074 | 1.251 | 7.554 | 317 | 1.768 | 0.623 | 5.014 | ||

| Procedure for primary LC | ||||||||||

| Limited resection | 143 | 1 | — | — | .035 | — | — | — | — | — |

| ≥Lobectomy | 334 | 0.649 | 0.434 | 0.969 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Primary LC | ||||||||||

| Ad | 349 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Non‐Ad | 128 | 3.621 | 2.451 | 5.349 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| p‐Stage | ||||||||||

| I | 350 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| II | 37 | 1.963 | 0.489 | 0.179 | .163 | — | — | — | — | — |

| III | 17 | 2.874 | 0.269 | 2.703 | .786 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Undetermined | 73 | 1.645 | 0.884 | 2.372 | .142 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Treatment for metachronous LC | ||||||||||

| Surgery | 338 | 1 | — | — | .036 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Others | 139 | 1.533 | 1.028 | 2.287 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Histology of 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| Pre | 15 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ad | 273 | 0.911 | 0.219 | 3.787 | .459 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Non‐Ad | 143 | 3.229 | 0.788 | 13.233 | .103 | — | — | — | — | — |

| CTR of 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| ≤0.5 | 116 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 109 | 1 | — | — | .297 |

| >0.5 | 287 | 3.791 | 1.961 | 7.330 | 263 | 1.465 | 0.715 | 3.004 | ||

| Histology combination of primary LC and 2nd LC | ||||||||||

| Not included non‐Ad | 254 | 1 | — | — | <.001 | 225 | 1 | — | — | <.001 |

| Included non‐Ad | 177 | 4.528 | 2.879 | 7.121 | 147 | 2.707 | 1.611 | 4.547 | ||

| Synchronous MPLC | ||||||||||

| No | 426 | 1 | — | — | .532 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 51 | 0.804 | 0.406 | 1.594 | — | — | — | — | — | |

Abbreviations: Ad, adenocarcinoma; CI, confidence interval; CTR, consolidation‐tumor ratio; HR, hazard ratio; LC, lung cancer; Pre, preinvasive lesion.

3.3. Risk factors for MPLC

To determine significant factors associated with the presence of synchronous or metachronous MPLC, logistic regression analysis was carried out. Of the enrolled cohort, 579 had synchronous MPLC and 477 metachronous MPLC during the period of observation, with 51 overlapping cases, thus 1005 patients were defined as MPLC and compared to 8684 with SPLC. Independent risk factors for MPLC incidence in the present cohort were female gender, history of malignant disease other than LC, and COPD (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Logistic analysis for multiple primary lung cancer (MPLC) compared to solitary primary lung cancer (SPLC)

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | P value | N | OR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 5671 | 1 | — | — | .034 | 5671 | 1 | — | — | .047 |

| Female | 4015 | 1.153 | 1.011 | 1.315 | 4015 | 1.156 | 1.002 | 1.333 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤70 | 5174 | 1 | — | — | .469 | — | — | — | — | — |

| >70 | 4512 | 1.050 | 0.921 | 1.196 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| History of malignant disease other than LC | ||||||||||

| No | 7803 | 1 | — | — | .003 | 7803 | 1 | — | — | .002 |

| Yes | 1883 | 1.270 | 1.086 | 1.485 | 1883 | 1.284 | 1.097 | 1.502 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||||||

| No | 8369 | 1 | — | — | .270 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1317 | 1.110 | 0.992 | 1.335 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| COPD | ||||||||||

| No | 8351 | 1 | — | — | .228 | 8351 | 1 | — | — | .025 |

| Yes | 1335 | 1.120 | 0.932 | 1.345 | 1335 | 1.251 | 1.029 | 1.522 | ||

| Interstitial pneumonia | ||||||||||

| No | 9279 | 1 | — | — | .838 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 407 | 0.966 | 0.695 | 1.343 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Smoking history | ||||||||||

| No | 3795 | 1 | — | — | .956 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 5683 | 1.004 | 0.877 | 1.148 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Histology of primary LC | ||||||||||

| Ad | 7616 | 1 | — | — | .053 | 7616 | 1 | — | — | .133 |

| non‐Ad | 2070 | 0.849 | 0.72 | 1.002 | 2070 | 0.871 | 0.728 | 1.043 | ||

| CTR of primary LC | ||||||||||

| ≤0.5 | 1536 | 1 | — | — | .025 | 1536 | 1 | — | — | .079 |

| >0.5 | 8150 | 0.823 | 0.694 | 0.976 | 8150 | 0.855 | 0.717 | 1.018 | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | ||||||||||

| ≤5 | 6819 | 1 | — | — | .325 | — | — | — | — | — |

| >5 | 2576 | 1.076 | 0.930 | 1.246 | — | — | — | — | — | |

Abbreviations: Ad, adenocarcinoma; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTR, consolidation‐tumor ratio; LC, lung cancer; OR, odds ratio.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study identified the characteristics of patients with synchronous MPLC, as well as of those with metachronous MPLC. Although synchronous MPLC and metachronous MPLC affected the incidence rate of each other in this cohort, the characteristics of the present patients with synchronous MPLC and metachronous MPLC were different. It can be difficult to distinguish between a second primary and IPM in patients with NSCLC who have more than one pulmonary site of cancer 13 , 14 ; thus, it might be important to know the patient characteristics of MPLC, which are critical for developing a therapeutic strategy to treat multiple pulmonary sites of involvement. As pulmonary nodules with ground glass opacity could often be diagnosed as synchronous MPLC and would be indicated for surgical resection, this bias in the surgical indication might have affected the characteristics of patients with synchronous MPLC in the present study. However, the present data suggest that nonadenocarcinoma might more frequently develop metachronous MPLC after resection of primary LC; thus, it might be reasonable that male gender, smoker, COPD, and IP were significantly more frequent in the metachronous MPLC group.

The surgical outcome for node‐negative patients with synchronous MPLC is excellent and comparable to that for solitary primary LC. 15 We also showed that there was no significant difference in regard to survival rate between patients with and without synchronous MPLC. Zhang et al 16 reported that lymph node involvement and subtype other than lepidic predominant were independent prognostic predictors. As the present study included c‐Stage I NSCLC patients with MPLC, CTR was one of the independent prognostic predictors. In addition, although the main pathologic type of synchronous MPLC was adenocarcinoma‐adenocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma‐preinvasive LC, it was found that patients in whom the histological type of primary or second LC included nonadenocarcinoma had a worse prognosis. Tanvetyanon et al 17 reported that adenocarcinoma was independently associated with better outcomes, which is in agreement with the present results. The proportion of adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma in synchronous MPLC is high, which supports the trend of multiple cancers of lung adenocarcinoma, 18 which is associated with good prognosis of synchronous MPLC. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the largest series reporting surgical outcomes for stage I synchronous MPLC.

It has been reported that the most common histological combination of primary LC and metachronous second LC is adenocarcinoma‐adenocarcinoma, 19 similar to synchronous MPLC, which is in agreement with the present findings. Primary lung adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas most frequently had second lung adenocarcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas, respectively. 20 In the present study, although there was no significant difference between patients with and without metachronous occurrence, those with a nonadenocarcinoma as primary or second LC had poorer prognosis. Furthermore, approximately 37% of patients who underwent metachronous treatment had the histological combination of first or second LC including nonadenocarcinoma, which might affect the prognosis. Hattori et al also showed that the combination of the same lesion types with pure solid nodule plus pure solid nodule was associated with worse survival than other combinations in surgically resected stage I MPLC, probably because IPM was present in those tumors. 21 Although the present univariate analysis results showed that the CTR value for second LC was a prognostic indicator for patients with metachronous treatment for MPLC, multivariate analysis did not show that indication, likely because the histology of metachronous LC could be a confounding factor related to the CTR value for second LC.

According to the 8th TNM staging system, patients should be staged as T3 with additional tumor(s) within the same lobe, T4 with an ipsilateral lesion in a separate lobe, and M1a with a contralateral tumor in a separate lobe. 22 However, this staging system could probably cause inaccurate assessment and treatment of patients with actual MPLC, who are considered to have local disease and could benefit the most from surgical resection. 3 , 16 Detterbeck et al proposed tailoring the TNM classification of multiple pulmonary sites of LC according to clinical and pathological criteria. 23 Application of the algorithm based on comprehensive information on clinical and imaging variables can also allow differentiation between MPLCs and IPMs. When both of two suspected malignant lesions appear as solid predominant lesions without spiculation or air‐bronchograms on CT, IPM should be considered. 14 , 24 Goto et al 25 showed that LC mutation analysis by targeted deep sequencing is useful for distinction of the clonality of individual pulmonary tumors. Whereas a good or poor prognosis after resection of two pulmonary sites of cancer strongly suggests either stage I MPLC or IPM, clinical and pathologic criteria should be developed to identify two foci as separate primary lung cancers vs a metastasis. In the present cohort, female gender, history of malignant disease other than LC, and COPD were independent risk factors for incidence of MPLC. This information could have major implications regarding the diagnosis of MPLC, considering that current guidelines are geared towards concern about the recurrence of IPM rather than the development of MPLC. 20 It would be beneficial to establish a risk profile for the development of MPLC.

Whereas lobectomy remains the most effective treatment for patients with resectable primary LC, the optimal extent of resection for MPLC has not been established. 9 Generally, the extent of resection was based on the balance of the risks and benefits of surgery, mainly considering characteristics of the tumor and the patient’s PS, as well as pulmonary function. Surgical indications might also be different depending on individual surgeons. Sublobar resections are often selected when a patient’s lung function is too poor to allow the patient to tolerate lobectomy, suggesting that prior surgery might have impacted the lung function of patients with MPLC to the point that lobectomy could not be safely offered. 26 Although previous reports showed that sublobar resection is acceptable with a comparable prognosis to anatomic lobar resection for MPLC, some studies of patients with surgically treated metachronous MPLC reported somewhat worse outcomes. Compared to primary LC, metachronous MPLC underwent less frequent surgical resection but received treatment more often with radiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy, probably due to poor PS. 27 While 71% of patients who received metachronous MPLC treatment underwent surgery for second LC, a wedge resection or segmentectomy was frequently carried out for second LC, which might affect the prognosis after surgery for second LC. Sublobar resection was reported to offer sufficient local control and prognosis for peripheral low‐CTR LC on chest CT. 28 , 29 Thus, considering these findings, we could try to carry out a limited resection for primary LC in patients with a high risk of MPLC, especially with a lower‐CTR primary LC.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study using registry data. Second, individual surgeons diagnosed second LC as MPLC from clinical and pathological features. Third, patients with MPLC who did not undergo surgical intervention were not included, which caused selection and information biases. Finally, data were not completely registered for some categories, such as CTR for second LC and histology for metachronous LC.

In conclusion, this study determined the clinical features and outcomes of synchronous resected MPLC and metachronous treated MPLC. Although the characteristics of the present patients with synchronous MPLC and metachronous MPLC were different, surgical resection remains the primary treatment choice for MPLC, and the treatment results for those cases were acceptable and compatible with those for the SPLC patients. Age, gender, CTR of second LC, and histological combination of primary and second LC were shown to be prognostic indicators for both types of patients. In addition, gender, history of malignant disease other than LC, and COPD were independent risk factors for incidence of MPLC. These findings could have major implications regarding diagnosis of MPLC and identification of independent prognostic factors, and are considered to provide valuable clues for postoperative management of patients with MPLC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr Asamura reports lecture fees from Medtronic, Johnson and Johnson, and Taiho Pharmaceutical. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Fig S1

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all of the contributors at the participating institutions. This work was supported by The Japan Lung Cancer Society, The Japanese Association for Chest Surgery, The Japanese Respiratory Society, The Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy, and The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Shintani Y, Okami J, Ito H, et al; The Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry . Clinical features and outcomes of patients with stage I multiple primary lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:1924–1935. 10.1111/cas.14748

Funding information

The Japan Lung Cancer Society, The Japanese Association for Chest Surgery, The Japanese Respiratory Society, The Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy, and The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vazquez M, Carter D, Brambilla E, et al. Solitary and multiple resected adenocarcinomas after CT screening for lung cancer: histopathologic features and their prognostic implications. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:148‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asamura H. Multiple primary cancers or multiple metastases, that is the question. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:930‐931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warth A, Macher‐Goeppinger S, Muley T, et al. Clonality of multifocal nonsmall cell lung cancer: implications for staging and therapy. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1437‐1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tucker MA, Murray N, Shaw EG, et al. Second primary cancers related to smoking and treatment of small‐cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Working Cadre. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1782‐1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aziz TM, Saad RA, Glasser J, Jilaihawi AN, Prakash D. The management of second primary lung cancers. A single centre experience in 15 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:527‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Battafarano RJ, Force SD, Meyers BF, et al. Benefits of resection for metachronous lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:836‐842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu M, He W, Yang J, Jiang G. Surgical treatment of synchronous multiple primary lung cancers: a retrospective analysis of 122 patients. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:1197‐1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao H, Yang H, Han K, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with metachronous second primary lung adenocarcinomas. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:295‐302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okami J, Shintani Y, Okumura M, et al. Demographics, safety and quality, and prognostic information in both the seventh and eighth editions of the TNM Classification in 18,973 surgical cases of the Japanese Joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry Database in 2010. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:212‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70:606‐612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Antakli T, Schaefer RF, Rutherford JE, Read RC. Second primary lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:863‐866; discussion 867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsunaga T, Suzuki K, Takamochi K, Oh S. New simple radiological criteria proposed for multiple primary lung cancers. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:1073‐1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suh YJ, Lee H‐J, Sung P, et al. A novel algorithm to differentiate between multiple primary lung cancers and intrapulmonary metastasis in multiple lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(2):203‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu Y‐C, Hsu P‐K, Yeh Y‐C, et al. Surgical results of synchronous multiple primary lung cancers: similar to the stage‐matched solitary primary lung cancers? Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1966‐1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Z, Gao S, Mao Y, et al. Surgical outcomes of synchronous multiple primary non‐small cell lung cancers. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanvetyanon T, Finley DJ, Fabian T, et al. Prognostic nomogram to predict survival after surgery for synchronous multiple lung cancers in multiple lobes. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:338‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen D, Mei L, Zhou Y, et al. A novel differential diagnostic model for multiple primary lung cancer: differentially‐expressed gene analysis of multiple primary lung cancer and intrapulmonary metastasis. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1081‐1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamaji M, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Surgical treatment of metachronous second primary lung cancer after complete resection of non‐small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:683‐690; discussion 690–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thakur MK, Ruterbusch JJ, Schwartz AG, Gadgeel SM, Beebe‐Dimmer JL, Wozniak AJ. Risk of second lung cancer in patients with previously treated lung cancer: analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:46‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hattori A, Matsunaga T, Takamochi K, Oh S, Suzuki K. Importance of ground glass opacity component in clinical stage IA radiologic invasive lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:313‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rami‐Porta R, Bolejack V, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revisions of the T descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(7):990‐1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Franklin WA, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: summary of proposals for revisions of the classification of lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(5):639‐650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu DM, van Klaveren RJ, de Bock GH, et al. Role of baseline nodule density and changes in density and nodule features in the discrimination between benign and malignant solid indeterminate pulmonary nodules. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:492‐498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goto T, Hirotsu Y, Mochizuki H, et al. Mutational analysis of multiple lung cancers: discrimination between primary and metastatic lung cancers by genomic profile. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31133‐31143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ha D, Choi H, Chevalier C, Zell K, Wang XF, Mazzone PJ. Survival in patients with metachronous second primary lung cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:79‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reinmuth N, Stumpf A, Stumpf P, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with second primary lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1668‐1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sakurai H, Asamura H. Sublobar resection for early‐stage lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2014;3:164‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, et al. Appropriate sublobar resection choice for ground glass opacity‐dominant clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: wedge resection or segmentectomy. Chest. 2014;145:66‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3