Abstract

Molecular agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)‐, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)‐ or c‐ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) alterations have revolutionized the treatment of oncogene‐driven non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, the emergence of acquired resistance remains a significant challenge, limiting the wider clinical success of these molecular targeted therapies. In this study, we investigated the efficacy of various molecular targeted agents, including erlotinib, alectinib, and crizotinib, combined with anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) 2 therapy. The combination of VEGFR2 blockade with molecular targeted agents enhanced the anti‐tumor effects of these agents in xenograft mouse models of EGFR‐, ALK‐, or ROS1‐altered NSCLC. The numbers of CD31‐positive blood vessels were significantly lower in the tumors of mice treated with an anti‐VEGFR2 antibody combined with molecular targeted agents compared with in those of mice treated with molecular targeted agents alone, implying the antiangiogenic effects of VEGFR2 blockade. Additionally, the combination therapies exerted more potent antiproliferative effects in vitro in EGFR‐, ALK‐, or ROS1‐altered NSCLC cells, implying that VEGFR2 inhibition also has direct anti‐tumor effects on cancer cells. Furthermore, VEGFR2 expression was induced following exposure to molecular targeted agents, implying the importance of VEGFR2 signaling in NSCLC patients undergoing molecular targeted therapy. In conclusion, VEGFR2 inhibition enhanced the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents in various oncogene‐driven NSCLC models, not only by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis but also by exerting direct antiproliferative effects on cancer cells. Hence, combination therapy with anti‐VEGFR2 antibodies and molecular targeted agents could serve as a promising treatment strategy for oncogene‐driven NSCLC.

We found that VEGFR2 blockade augmented the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents in oncogene‐driven NSCLC, particularly in EGFR/ALK/ROS1‐driven NSCLC. We also identified 2 mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy with molecular targeted agents. VEGFR2 blockade not only inhibited tumor angiogenesis but also exerted direct antiproliferative effects on cancer cells.

1. INTRODUCTION

The identification of oncogenic gene alterations has revolutionized the treatment of advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), 1 anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), 2 and c‐ros oncogene 1 (ROS1) genes 3 are among the most common oncogenic alterations in NSCLC, 4 and agents targeting these mutated proteins have been shown to exert strong anti‐tumor effects. 5 , 6 , 7 However, a significant percentage of patients develop acquired resistance to these agents, hence the development of combination therapies is of high clinical importance.

Antiangiogenic agents suppress tumor growth by inhibiting the formation of new blood vessels. 8 The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)‐targeting antibody bevacizumab has been proven effective in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. 9 Moreover, the combination of bevacizumab with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) exerted strong anti‐tumor effects in EGFR‐mutant NSCLC. 10 Notably, patients treated with the EGFR‐TKI erlotinib plus bevacizumab had a median progression‐free survival of 16.9 mo, compared with 13.3 mo in patients treated with erlotinib alone. 10 Similarly, combination of the anti‐VEGFR2 antibody ramucirumab with erlotinib significantly prolonged the progression‐free survival of patients with EGFR‐mutant NSCLC compared with erlotinib alone (19.4 vs. 12.4 mo, P < .0001). 11 Although these data imply that targeting the VEGF pathway augments the anti‐tumor effects of EGFR TKIs, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Furthermore, whether the combination of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy with other targeted molecular therapies provides a clinical benefit in patients with oncogene‐driven NSCLC remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we investigated the therapeutic effects of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy in combination with different molecular targeted agents in oncogene‐driven NSCLC, as well as explored the mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of these therapies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell lines and reagents

PC‐9 cells (EGFR Ex19 del E746_A750) were purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures and A549 cells from the American Type Culture Collection. H3255 cells were kindly gifted by N Fujimoto and JM Kurie (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA). H3122 (EML4‐ALK fusion) and HCC78 (SLC34A2‐ROS1 fusion) cells were kindly provided by William Pao (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA). ABC‐11 (EML4‐ALK fusion) and ABC‐20 (CD74‐ROS1 fusion) cells were established from NSCLC patients in our laboratory. 12 , 13 All cell lines were cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin; cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humified atmosphere.

Ramucirumab and the anti‐mouse VEGFR2 antibody DC101 were obtained from Eli Lilly. Erlotinib, osimertinib, alectinib, and crizotinib were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. All compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide for in vitro studies.

Growth inhibition was measured using the modified 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, cells were seeded into 96‐well plates at densities of 1000‐8000 cells/well (PC‐9:1000 cells/well; H3255/ABC‐11/H3122: 3000 cells/well; HCC78: 2000 cells/well; ABC‐20:8000 cells/well) and treated with each drug for 96 h.

2.2. Antibodies, immunoblotting, and receptor tyrosine kinase array

The following antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology: phospho‐EGFR (Tyr1068), EGFR, phospho‐ALK (Tyr1282/1283), ALK, phospho‐ROS1 (Tyr2274), ROS1, phospho‐ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK1/2, phospho‐AKT (Ser473), AKT, GAPDH, and horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG antibody.

For immunoblotting, cells were harvested, washed in phosphate‐buffered saline, and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% Triton X‐100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mmol/L Tris‐HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 10 mmol/L β‐glycerol‐phosphate, 10 mmol/L NaF, and 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Sciences). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto membranes, which were then incubated with the indicated primary and secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence plus reagent (GE Healthcare Biosciences).

Phospho‐receptor tyrosine kinase arrays were performed using a phospho‐receptor tyrosine kinase array kit (R&D Systems) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Bands and dots were detected using the ImageQuant LAS‐4000 imager (GE Healthcare Biosciences).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue blocks were cut into 5‐μm‐thick sections, placed on glass slides, and deparaffinized with d‐limonene and graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min at 95°C. Subsequently, the sections were incubated for 10 min in methanol containing 3% hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing with Tris‐buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, tissues were incubated with normal goat serum for 60 min. Sections were probed with an anti‐CD31 antibody (#77699; Cell Signaling Technology) and anti‐VEGFR2 antibody(#2479S; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Thereafter, the sections were incubated for 30 min with biotinylated anti‐rabbit antibodies and avidin‐biotinylated horseradish peroxidase conjugate (SignalStain Boost IHC Detection Reagent #8114; Cell Signaling Technology). Finally, sections were incubated with 3,3‐diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. The antibody dilutions were performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.4. Quantitative reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR)

RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. VEGFR2 copy number gain was assessed by qRT‐PCR using the TaqMan probes and primers detailed in Table S1. PCR was run on the LightCycler Real‐Time PCR System (Roche Applied Science), and gene dosage was calculated using a standard curve. The VEGFR2/GAPDH copy number ratio was also calculated.

2.5. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

Transfection conditions for siRNA‐mediated gene knockdown were optimized using VEGFR2 siRNAs (Dharmacon Inc) and Lipofectamine Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 96‐well plate format (PC‐9:1500 cells/well; H3122: 3000 cells/well; ABC‐20:8000 cells/well). Two predesigned gene‐specific siRNAs were tested for each candidate gene, along with negative and positive controls (Dharmacon VEGFR2 siRNA). Gene silencing efficiency was evaluated 48 h post‐transfection by qRT‐PCR.

2.6. ELISA

Cells were seeded into 3.5 cm cell culture dishes (3.0 × 105 cells/dish), and the cell supernatant was collected after 24 h. The levels of VEGF‐A were determined by Human VEGF Quantikine ELISA (R&D Systems) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Xenograft mouse models

Female BALB/c nu/nu mice (6 wk old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories). All mice were provided sterilized food and water and housed in a barrier facility under a 12‐h light/dark cycle. Cancer cells (2‐5 × 106) were injected subcutaneously into the back on both sides of the mice. When the average tumor volume reached ~200 mm3, the mice were randomly allocated into 4 treatment groups (4 mice/group): vehicle, DC101 (10 mg/kg/d), molecular targeted agent (erlotinib [30 mg/kg/d], osimertinib [5 mg/kg/d], alectinib [10 mg/kg/d], or crizotinib [50 mg/kg/d]), and DC101 combined with the molecular targeted agents. Vehicle and molecular targeted agents were administered by gavage once daily, 5 times weekly. DC101 was administered by intraperitoneal administration once daily, twice weekly.

Tumor volume (width2 × length/2) was determined periodically. Statistical analyses were conducted using the tumor volumes measured on day 28. All experiments involving animals were performed under the auspices of the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee at the Department of Animal Resources, Okayama University Advanced Science Research. The experiments were performed under the Policy on the Care and Use of the Laboratory Animals, Okayama University, and Fundamental Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiment and Related Activities in Academic Research Institutions, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Okayama University, Okayama, Japan (OKU‐2018455).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software (version 15; StataCorp). Differences between groups were compared using two‐tailed paired Student t tests. P‐values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Anti‐VEGFR2 therapy augments the efficacy of molecular targeted therapy in oncogene‐driven cancer

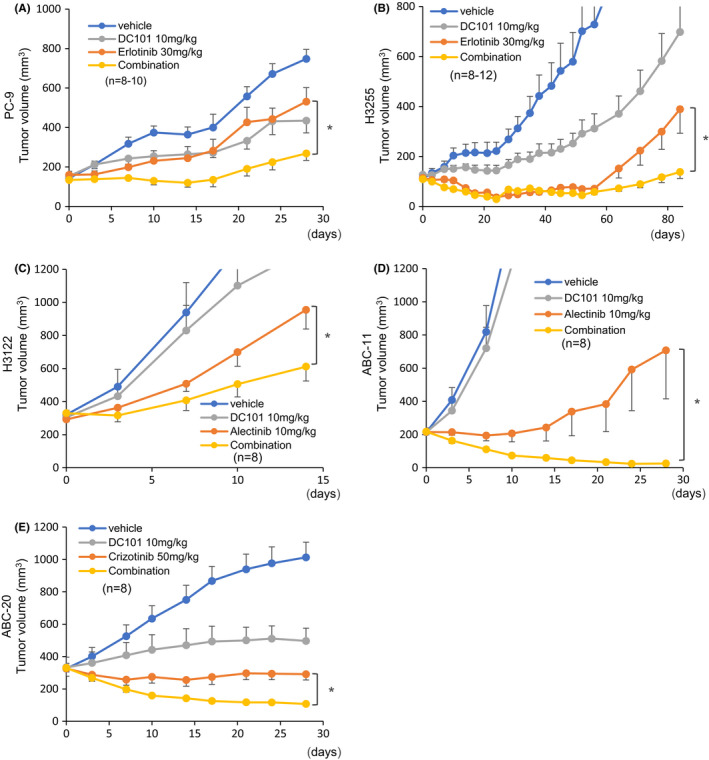

Here, we investigated the effects of the anti‐mouse VEGFR2 antibody DC101 on the efficacy of molecular targeted therapies in NSCLC harboring EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 alterations. To this end, we used the EGFR‐mutant PC‐9 and H3255 cells, the ALK‐rearranged H3122 and ABC‐11 cells, and the ROS1‐rearranged ABC‐20 cells. We first assessed the efficacy of DC101 on erlotinib in PC‐9 xenograft tumors, which harbor an EGFR exon 19 deletion. DC101 and erlotinib combination therapy exerted more potent anti‐tumor effects compared with erlotinib monotherapy (Figure 1A). We also assessed the combination therapy in H3255 xenograft tumors harboring the EGFR exon 21 L858R point mutation. Both erlotinib monotherapy and the combination of DC101 with erlotinib almost completely inhibited tumor growth up to 60 d of treatment. Tumor regrowth was observed in the erlotinib monotherapy group after cessation of the treatment, whereas more durable tumor inhibition was observed in the combination therapy group (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Combination of molecular targeted agents and VEGFR2 blockade in xenograft mouse models. Mice were transplanted with PC‐9, H3255, H3122, ABC‐11, or ABC‐20 cells. Molecular targeted agents were orally administered 5 times weekly. DC101 was administered intraperitoneally (10 mg/kg/d) twice weekly. A, B, Mice bearing PC‐9 or H3255 tumors were treated with vehicle, erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d), DC101, or erlotinib plus DC101 combination. In H3255‐transplanted mice, the erlotinib dose was reduced to 15 mg/kg/d from day 21, and the treatment was discontinued from day 53. C, D, Mice bearing H3122 and ABC‐11 tumors were treated with vehicle, alectinib (10 mg/kg/d), DC101, or alectinib plus DC101 combination. E, Mice bearing ABC‐20 tumors were treated with vehicle, crizotinib (50 mg/kg/d), DC101, or crizotinib plus DC101 combination. Error bars represent standard errors; *P < .05

The efficacy of the combination of DC101 with EGFR TKIs was also investigated using osimertinib, a third‐generation EGFR‐TKI. The combination therapy provided significantly stronger anti‐tumor effects in PC‐9 xenograft tumors compared with osimertinib alone (Figure S1A). Similarly, the combination of DC101 with the ALK‐TKI alectinib exerted stronger anti‐tumor effects in ALK‐rearranged H3122 tumors compared with alectinib monotherapy (Figure 1C). Similar results were obtained with ALK‐rearranged ABC‐11 xenograft models, in which treatment with DC101 augmented the therapeutic effects of alectinib (Figure 1D). We also investigated the therapeutic effects of DC101 in ROS1‐rearranged NSCLC using ABC‐20 cells (CD74‐ROS1 fusion). DC101 significantly enhanced the anti‐tumor effects of the ROS1‐TKI crizotinib in ABC‐20 tumors (Figure 1E). Notably, no significant toxicities were observed in mice treated with any of the combination therapies (Figures S1B and S2). ROS1‐rearranged HCC78 cells failed to engraft even in highly immunosuppressed NOG mice (data not shown).

3.2. Combination of anti‐VEGFR2 antibody with molecular targeted therapy inhibits tumor angiogenesis

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the enhanced anti‐tumor effects of the combination of DC101 with molecular targeted therapy, we analyzed the extent of tumor angiogenesis in xenograft tumors. Anti‐mouse CD‐31 antibody stained the vessels, but anti‐human CD‐31 antibody did not (data not shown), suggesting that the tumor vessels were derived from mouse tissues. Anti‐mouse CD31 immunostaining revealed that DC101 monotherapy or the combination of DC101 with erlotinib, alectinib, or crizotinib impaired angiogenesis in PC‐9 (EGFR‐mutant), H3122 (ALK‐rearranged), and ABC‐20 (ROS1‐rearranged) xenograft tumors, respectively (Figures 2A and S1C). The combination treatments provided more profound antiangiogenic effects compared with the molecular targeted agents alone (Figures 2B,C and S1D), although quantification could not be performed in PC‐9 tumors due to their small size. These data imply that DC101 enhanced the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents by inhibiting tumor angiogenesis.

FIGURE 2.

VEGFR2 blockade suppresses angiogenesis in xenograft mouse models. A, Immunohistochemical staining of CD31 in PC‐9, H3122, and ABC‐20 xenograft tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. B, C, Number of CD31‐positive blood vessels in tumors treated with the indicated drugs. Each bar indicates the average number of CD31‐positive blood vessels in 5 fields. Error bars represent standard errors; *P < .005

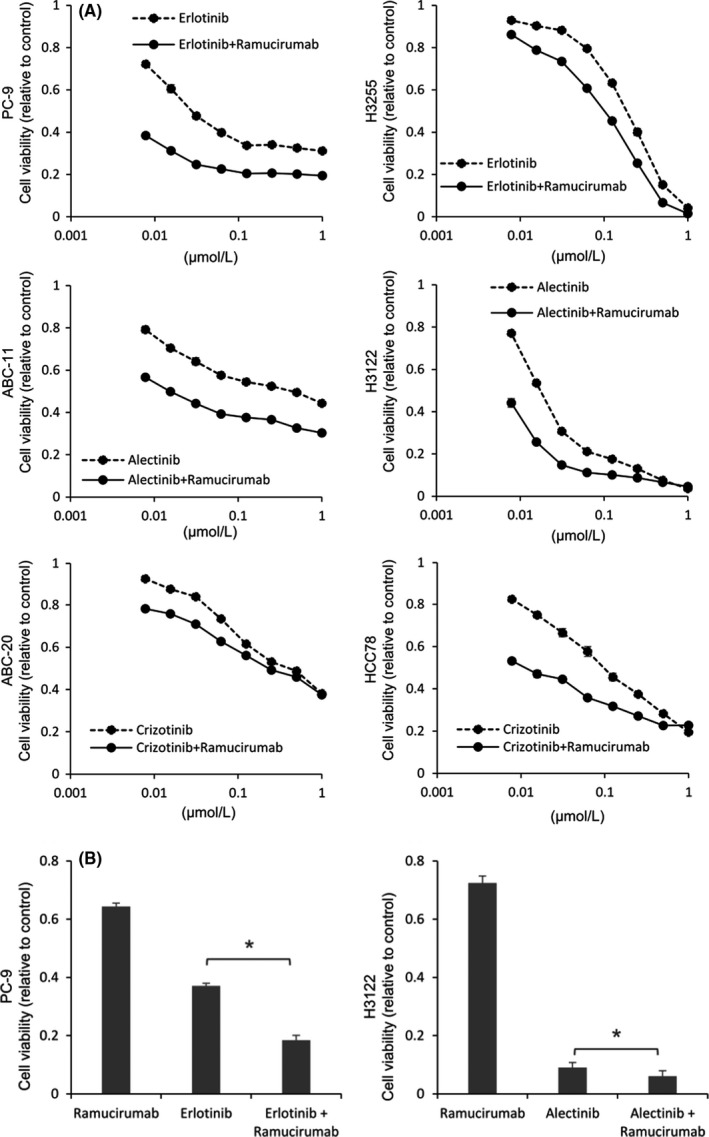

3.3. VEGFR2 blockade enhances the antiproliferative effects of molecular targeted therapies in vitro

To determine whether VEGFR2 inhibition has any impact on oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells themselves in addition to inhibiting tumor angiogenesis, we investigated the effects of VEGFR2 blockade in different NSCLC cell lines in vitro. As all of the cell lines used were derived from human NSCLC, we used the human anti‐VEGFR2 antibody ramucirumab. We performed cell proliferation assays in EGFR‐mutant (PC‐9, H3255), ALK‐rearranged (ABC‐11, H3122), and ROS‐1‐rearranged (ABC‐20, HCC78) NSCLC cells treated with erlotinib, alectinib, and crizotinib, respectively (Figure 3A,B). Although the difference was moderate, combination with ramucirumab significantly enhanced their antiproliferative effects in vitro, implying a potential role of VEGFR2 signaling in NSCLC cell proliferation. We also assessed the effects of siRNA‐mediated VEGFR2 silencing combined with molecular targeted agents (Figure 4). Consistently, VEGFR2 silencing significantly enhanced the antiproliferative effects of molecular targeted agents in PC‐9, H3122, and ABC‐20 cells (Figure 4A‐C). Decreased VEGFR2 expression by siVEGFR2 was confirmed in all of these cells (Figure 4D‐F).

FIGURE 3.

VEGFR2 blockade enhances the antiproliferative effects of molecular targeted therapies in vitro. A, Cell proliferation assays in cells treated with the indicated concentrations of each molecular targeted agent. Ramucirumab was used at 150 μg/mL. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and representative data are shown. B, Antiproliferative effects of the combination therapy with erlotinib (100 nmol/L), alectinib (100 nmol/L), and ramucirumab (150 μg/mL) in PC‐9 and H3122 cells over 96 h, as determined by MTT assay. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < .001

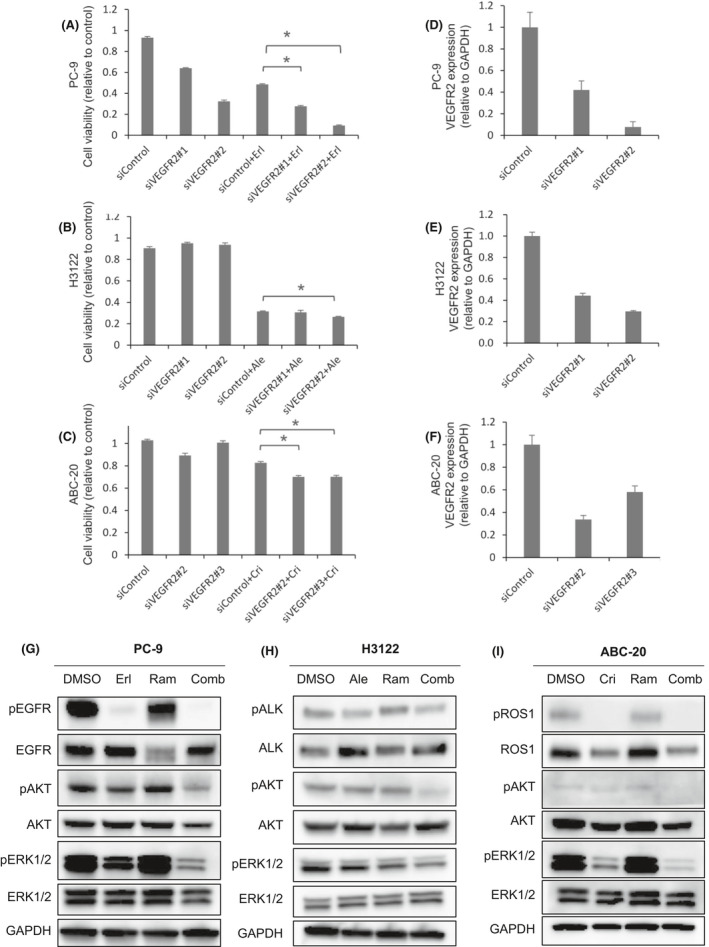

FIGURE 4.

Effects of VEGFR2 silencing combined with molecular targeted agents on oncogenic signaling pathways and cell growth. A‐C, Two different VEGFR2‐targeting siRNAs were used. The effects of VEGFR2 silencing on cell growth in PC‐9, H3122, and ABC‐20 cells. PC‐9 cells were treated with erlotinib (100 nmol/L) for 96 h, H3122 cells with alectinib (100 nmol/L) for 96 h, and ABC‐20 cells with crizotinib (1 μmol/L) for 96 h. All cell lines were treated with ramucirumab (150 μg/mL) for 96 h. *P < .005. D‐F, qRT‐PCR analysis showing efficient siRNA‐mediated VEGFR2 knockdown in different cell lines. GAPDH was used as the reference gene. Data are presented as means ± SE. G‐I, Phospho‐ERK1/2 (PC‐9 and ABC‐20 cells) and phospho‐AKT levels (H3122 cells) were lower in cells treated with the combination therapy compared with in cells treated with the molecular targeted agents alone. PC‐9, H3122, and ABC‐20 cells were treated with erlotinib (100 nmol/L), alectinib (100 nmol/L), and crizotinib (1 μmol/L), respectively. All cell lines were also exposed to ramucirumab (150 μg/mL); all treatments were performed for 96 h

We then investigated the effects of VEGFR2 inhibition on downstream signaling pathways. We found that cells treated with the combination therapies had lower phospho‐ERK1/2 and phospho‐AKT levels than did cells treated with molecular targeted agents alone in PC‐9, H3122, and ABC‐20 cells (Figure 4G‐I). These findings imply that VEGFR2 signaling is involved in upstream AKT and ERK pathways in oncogene‐driven NSCLC, and that anti‐VEGFR2 therapy, in addition to exerting antiangiogenic effects, could provide strong cell‐intrinsic anti‐tumor effects by interfering with various oncogenic pathways.

3.4. VEGF‐A and VEGFR2 are highly expressed in oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells

To investigate the relationship between oncogenic pathways and VEGFR2 activation, we assessed the level of VEGF‐A, a VEGFR2 ligand, in the cell culture supernatant of oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells. A549 and H2009 cells, both of which are wild‐type for EGFR, ALK, and ROS‐1, were used as controls. The majority of cell lines harboring EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 alteration exhibited higher VEGF‐A protein levels compared with control A549 cells (Figure 5A). We also found that HEK293T cells expressing mutant EGFR (L858R or exon 19 deletion) had significantly higher VEGF‐A protein levels in the cell supernatant compared with control cells (Figure 5B), implying that VEGF‐A secretion was driven by oncogenic signaling. Notably, treatment with erlotinib, alectinib, or crizotinib significantly decreased VEGF‐A secretion (Figure 5C), confirming that VEGF‐A production was driven by oncogenic signaling. Of note, long‐term exposure to molecular targeted agents further increased VEGF‐A secretion, indicating that VEGF‐A would be more important under long‐term inhibition of oncogene signal inhibition. A cell proliferation assay at the time of VEGF‐A recovery (after 6 wk of treatment) revealed early emergence of cellular acquired resistance, suggesting that VEGF‐A recovery occurred after such resistance developed (Figure S3).

FIGURE 5.

VEGF‐A is highly expressed in oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells. Cells were seeded into 3.5 cm dishes at 3.0 × 105 cells/2.0 mL, and the cell culture supernatant was collected after 24 h. A, The cell supernatant of EGFR‐, ALK‐, or ROS1‐altered cell lines (H3255, ABC‐11, H3122, HCC78, and ABC‐20) contained higher VEGF‐A levels compared with that of A549 control cells. B, HEK293T cells transfected with mutant EGFR (L858R or exon 19 deletion) exhibited higher levels of VEGF‐A secretion compared with control cells. C, VEGF‐A secretion after treatment with molecular targeted agents. PC‐9, ABC‐11, and ABC‐20 cells were treated with erlotinib (100 nmol/L), alectinib (100 nmol/L), or crizotinib (100 nmol/L), respectively. Data are presented as means ± SE

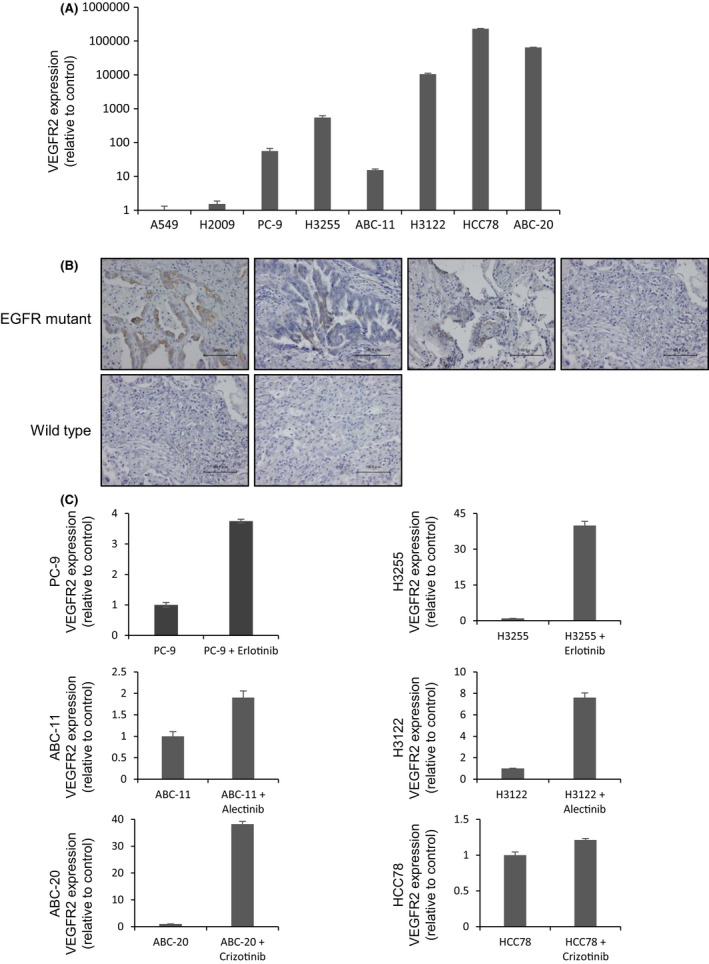

We also assessed VEGFR2 expression at the mRNA level using qRT‐PCR VEGFR2 mRNA levels were significantly higher in EGFR‐, ALK‐, or ROS1‐altered cells (PC‐9, H3255, ABC‐11, H3122, HCC78, and ABC‐20) compared with control cells (A549 and H2009; Figure 6A). We next investigated the VEGFR2 expression levels in clinical samples of EGFR‐mutant NSCLCs. VEGFR2 was expressed in 3 out of 4 lung cancers with EGFR mutations, although no expression was found in the 2 EGFR/ALK/ROS1 wild‐type NSCLCs (Figure 6B). Those data imply a potential role for VEGFR2 signaling in EGFR/ALK/ROS1‐driven NSCLC. Of note, treatment with erlotinib, alectinib, or crizotinib significantly increased the VEGFR2 mRNA level in EGFR‐ (PC‐9, H3255), ALK‐ (ABC‐11, H3122), or ROS1‐altered (ABC‐20, HCC78) NSCLC cells, respectively (Figure 6C). These findings imply that VEGF‐A/VEGFR2 signaling in oncogene‐driven NSCLC might be more critical under oncogene signal inhibition. Finally, we determined the VEGFR2 expression levels of the HEK293T model with or without mutant EGFR transfection (Figure S4). Unexpectedly, 19del or L858R transfection decreased VEGFR2 expression in HEK293T cells. Although the precise reason for this discrepancy from the data shown in Figure 6A,B remains unclear, forced expression may not simulate accurately the condition of EGFR‐mutant lung cancer cells.

FIGURE 6.

VEGFR2 is highly expressed in oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells. A, qRT‐PCR of VEGFR2 in PC‐9, H3255, ABC‐11, H3122, HCC78, and ABC‐20 cells. GAPDH was used as the reference gene. Data are presented as means ± standard error. B, Clinical specimens of tumors bearing EGFR mutations exhibited higher levels of VEGFR2 expression than did EGFR‐wild‐type tissues, as revealed by immunostaining. C, Increased VEGFR2 expression induced by treatment with erlotinib, alectinib, or crizotinib in accordance with qRT‐PCR. PC‐9, ABC‐11, and ABC‐20 cells were treated with erlotinib (100 nmol/L), alectinib (100 nmol/L), or crizotinib (1 μmol/L), respectively, for 24 h. Data are presented as means ± SE

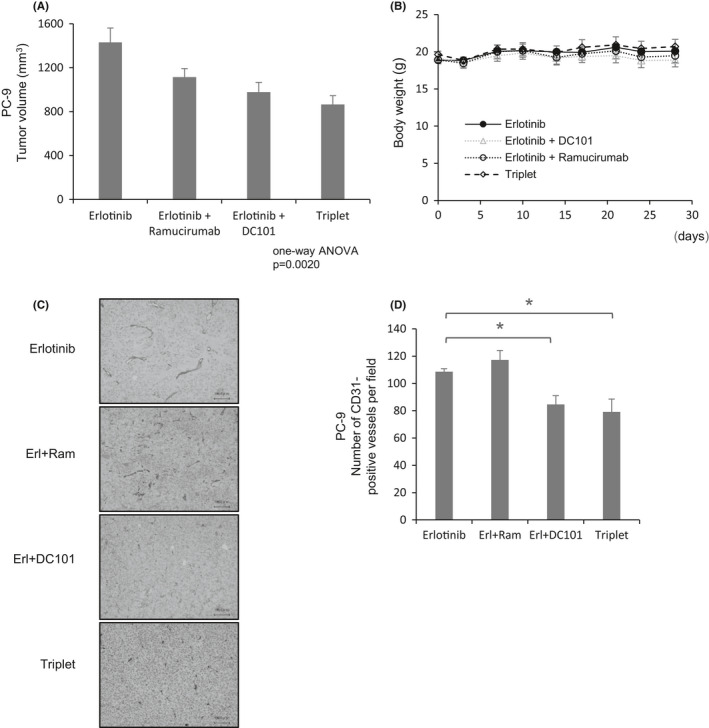

3.5. VEGFR2 blockade augments the anti‐tumor effects of TKIs by acting on both tumor cells and tumor vessels

In the human body, anti‐human VEGFR2 therapy works on both cancer cells and micro‐environmental tumor vessels. However, in our xenograft mouse model, the anti‐human VEGFR2 antibody ramucirumab acted only on xenograft tumors, while the anti‐mouse VEGFR2 antibody DC101 acted only on the vessels. Hence, to target VEGFR2 on both cancer cells and tumor vessels, we treated PC‐9 xenograft tumors with both ramucirumab and DC101. We found that the combination of erlotinib, DC101, and ramucirumab provided the most potent anti‐tumor effects in the xenograft mouse model (Figure 7A), with no significant toxicity (Figure 7B). Importantly, CD31 immunostaining revealed that the combination of DC101 and erlotinib or the triplet combination of DC101, ramucirumab, and erlotinib strongly inhibited vessels in the tumors treated (Figure 7C,D).

FIGURE 7.

VEGFR2 blockade augments the anti‐tumor effects of TKIs in mice bearing PC‐9 tumors. A, Mice bearing PC‐9 tumors were treated with erlotinib, erlotinib plus DC101, erlotinib plus ramucirumab, or triplet therapy. Erlotinib (30 mg/kg/d) was administered intraperitoneally 5 times weekly. DC101 and ramucirumab (10 mg/kg/d) were administered intraperitoneally twice weekly. B, Body weight of mice bearing PC‐9 tumors. C, Immunohistochemical staining of CD31 in mice bearing PC‐9 tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. D, Number of CD31‐positive blood vessels in tumors treated with the indicated drugs. Each bar indicates the average number of CD31‐positive blood vessels in 5 fields. Error bars represent standard errors; *P < .05

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that VEGFR2 blockade augmented the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents in various oncogene‐driven NSCLCs harboring EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 alterations. The enhanced anti‐tumor effects of the combination therapy were mediated via direct inhibition of cancer cell growth, as well as antiangiogenic effects. We previously showed that bevacizumab, an anti‐VEGF‐A antibody, enhanced the effects of EGFR TKIs in EGFR‐mutant NSCLC. 14 , 15 , 16 However, the effects of VEGFR2 blockade on the efficacy of EGFR TKIs or other molecular targeted agents in NSCLC were unclear. Therefore, in this study, we expanded our findings on the combination of anti‐VEGF‐A therapy with EGFR TKIs to VEGFR2 blockade combined with various molecular targeted agents in oncogene‐driven NSCLC. We demonstrated that the anti‐mouse VEGFR2 antibody DC101 enhanced the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents in mice bearing ALK‐, ROS1‐, or EGFR‐altered NSCLC.

Although the synergistic effects of anti‐VEGF‐A or anti‐VEGFR2 antibodies with EGFR TKIs have been demonstrated in multiple clinical and preclinical studies, 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 the precise underlying mechanisms are unclear. In this study, we performed CD31 immunostaining and showed that the combination of molecular targeted agents and VEGFR2 blockade with DC101 profoundly inhibited tumor angiogenesis. As DC101 can act on mouse vessels but not on implanted human cancer cells, the enhanced anti‐tumor effects of the combination therapy in the xenograft mouse models were attributed to the antiangiogenic effects of VEGFR2 blockade.

In contrast with the well established roles of VEGFR2 signaling in angiogenesis, the cell‐intrinsic effects of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy on cancer cells are less clear. Cancer cells express VEGFRs, and autocrine VEGF/VEGFR signaling promotes cancer cell growth, survival, migration, and invasion. 17 However, the relevance of VEGFR signaling in oncogene‐driven NSCLC was unknown. To determine the cell‐intrinsic effects of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy on oncogene‐driven NSCLC cells, we treated different human NSCLC cell lines with an anti‐human VEGFR2 antibody, ramucirumab, in vitro. The combination of ramucirumab with molecular targeted agents potentiated the antiproliferative effects of these agents, implying a cell‐intrinsic role of VEGFR2 signaling in oncogene‐driven NSCLC.

VEGF‐A expression is induced by various factors, including EGFR 18 , however a possible association between VEGFR signaling and ALK, or ROS‐1 signaling, in lung cancer remains elusive. In this study, we demonstrated that oncogenic signaling pathways influenced the expression of VEGF‐A and VEGFR2; VEGF‐A was highly expressed in EGFR/ALK/ROS1‐driven NSCLC cells (Figure 5A) and was induced by forced overexpression of mutant EGFR (Figure 5B). These data highlighted the fact that oncogenic signaling pathways can induce VEGFR2 pathway activation. Of note, the VEGFR2 mRNA levels were also elevated in EGFR/ALK/ROS1‐driven NSCLC cells (Figure 6A) and were further increased after treatment with molecular targeted agents (Figure 6C), whereas the VEGF‐A levels decreased transiently after treatment (Figure 5C). These data implied that the VEGFR2 signaling axis plays an important role in oncogene‐driven lung cancers; VEGFR2 levels would increase as a complemental response to the transient decrease in VEGF‐A levels induced by inhibition of oncogene signaling.

Another research group has investigated the therapeutic effects of a similar treatment strategy on oncogene‐driven cancer. In their study, they inhibited oncogenic drivers in combination with targeting the VEGF co‐receptor neuropilin‐1. 19 , 20 This combination therapy exerted potent anti‐tumor effects in vitro in oncogene‐driven melanoma and breast cancer cells, 21 further supporting our findings regarding the importance of VEGFR2 as a therapeutic target in combination with molecular targeted agents.

In conclusion, we found that VEGFR2 blockade augmented the anti‐tumor effects of molecular targeted agents in oncogene‐driven NSCLC, particularly in EGFR/ALK/ROS1‐driven NSCLC. We also identified two mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of anti‐VEGFR2 therapy with molecular targeted agents. VEGFR2 blockade not only inhibited tumor angiogenesis but also exerted direct antiproliferative effects on cancer cells. Thus, combination therapy with ramucirumab and molecular targeted agents could serve as a promising treatment strategy for ALK‐ or ROS1‐rearranged NSCLC, in addition to EGFR‐mutant NSCLC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

EI received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical. EI received additional research funding from Eli Lilly Japan. KO received a research grant from Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Japan. KH received honoraria and research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical. TM received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical. KK received honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceuticals. All other authors declare no conflict of interest regarding this study.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Nakashima and K. Maeda for their technical support.

Watanabe H, Ichihara E, Kayatani H, et al. VEGFR2 blockade augments the effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors by inhibiting angiogenesis and oncogenic signaling in oncogene‐driven non‐small‐cell lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:1853–1864. 10.1111/cas.14801

REFERENCES

- 1. Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497‐1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4‐ALK fusion gene in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561‐566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeuchi K, Soda M, Togashi Y, et al. RET, ROS1 and ALK fusions in lung cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18:378‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, et al. Global Survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190‐1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non‐small‐cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380‐2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First‐line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK‐positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167‐2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaw AT, Ou SH, Bang YJ, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1‐rearranged non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1963‐1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viallard C, Larrivée B. Tumor angiogenesis and vascular normalization: alternative therapeutic targets. Angiogenesis. 2017;20:409‐426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel‐carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542‐2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saito H, Fukuhara T, Furuya N, et al. Erlotinib plus bevacizumab versus erlotinib alone in patients with EGFR‐positive advanced non‐squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NEJ026): interim analysis of an open‐label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:625‐635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakagawa K, Garon EB, Seto T, et al. Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated, EGFR‐mutated, advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (RELAY): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;2045:1‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Isozaki H, Yasugi M, Takigawa N, et al. A new human lung adenocarcinoma cell line harboring the EML4‐ALK fusion gene. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:963‐968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kato Y, Ninomiya K, Ohashi K, et al. Combined effect of cabozantinib and gefitinib in crizotinib – resistant lung tumors harboring ROS1 fusions. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(10):3149‐3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ichihara E, Ohashi K, Takigawa N, et al. Effects of vandetanib on lung adenocarcinoma cells harboring epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5091‐5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ninomiya T, Takigawa N, Ichihara E, et al. Afatinib prolongs survival compared with gefitinib in an epidermal growth factor receptor‐driven lung cancer model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:589‐597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ichihara E, Hotta K, Nogami N, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib in combination with bevacizumab as first‐line therapy for advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer with activating EGFR gene mutations: The Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group trial 1001. J Thorac Oncol. International Association for the Study of. Lung Cancer. 2015;10:486‐491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:871‐882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tabernero J. The role of VEGF and EGFR inhibition: Implications for combining anti‐VEGF and anti‐EGFR agents. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:203‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amadio M, Govoni S, Pascale A. Targeting VEGF in eye neovascularization: What’s new?: A comprehensive review on current therapies and oligonucleotide‐based interventions under development. Pharmacol Res. 2016;103:253‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jarvis A, Allerston CK, Jia H, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of the neuropilin‐1 vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF‐A) interaction. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2215‐2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rizzolio S, Cagnoni G, Battistini C, et al. Neuropilin‐1 upregulation elicits adaptive resistance to oncogene‐targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3976‐3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material