Abstract

Introduction:

Despite the health benefits of physical activity for cancer survivors, nearly 60% of young adult cancer survivors (YACS) are physically inactive. Few physical activity interventions have been designed specifically for YACS.

Purpose:

To describe the rationale and design of the IMPACT (IMproving Physical Activity after Cancer Treatment) trial, which tests the efficacy of a theory-based, mobile physical activity intervention for YACS.

Methods:

A total of 280 physically inactive YACS (diagnosed at ages 18–39) will be randomized to a self-help control or intervention condition. All participants will receive an activity tracker and companion mobile app, cellular-enabled scale, individual videochat session, and access to a Facebook group. Intervention participants will also receive a 6-month mobile intervention based on social cognitive theory, which targets improvements in behavioral capability, self-regulation, self-efficacy, and social support, and incorporates self-regulation strategies and behavior change techniques. The program includes: behavioral lessons; adaptive goal-setting in response to individuals’ changing activity patterns; tailored feedback based on objective data and self-report measures; tailored text messages; and Facebook prompts encouraging peer support. Assessments occur at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months. The primary outcome is total physical activity minutes/week at 6 months (assessed via accelerometry); secondary outcomes include total physical activity at 12 months, sedentary behavior, weight, and psychosocial measures.

Conclusions:

IMPACT uniquely focuses on physical activity in YACS using an automated tailored mHealth program. Study findings could result in a high-reach, physical activity intervention for YACS that has potential to be adopted on a larger scale and reduce cancer-related morbidity.

Keywords: young adult cancer survivors, physical activity, technology, social media, tailored feedback, adaptive interventions

1. Introduction

There are over 630,000 young adult cancer survivors (YACS) in the United States [1,2]. YACS, diagnosed between ages 18–39, are a vulnerable subgroup of survivors who experience increased risk over time for obesity [3] and other chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease [3–5]. Increased physical activity (PA) offers myriad benefits, including positive effects on physical function [6], body composition [7], cardiovascular fitness [8], health-related quality of life [6,9,10], and depression [11], and may prevent cancer recurrence and improve survival [12,13]. Yet, about 60% of young adults diagnosed with cancer before or during young adulthood do not adhere to the recommended PA guidelines of 150 minutes/week of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) for cancer survivors [10,14,15]; and most are less physically active than siblings or peers without a cancer history [3,16]. Insufficient PA may be particularly problematic for YACS who have increased risks for morbidity and the potential to spend the majority of their lives dealing with long-term and late effects of cancer. Despite a high demand for PA programs [14,17–23], few interventions have been designed specifically to promote PA in YACS, nor have they used novel technologies or social media for delivery [24–27]. Previous studies have been limited by the use of self-reported PA outcomes, small sample sizes, short duration, and lack of effects on MVPA [24–29]. Furthermore, none have been successful in promoting long-term PA adherence [24–27].

The purpose of the IMproving Physical Activity after Cancer Treatment (IMPACT) trial is to test the efficacy of a theory-based, mobile intervention with adaptive goal-setting and tailored feedback aimed at increasing PA among YACS. YACS (n=280) will be recruited to a 12-month trial and randomized into a self-help or intervention condition. In this manuscript, we describe the rationale and design of the IMPACT trial.

1.2. Specific Aims

The primary aim is to determine the effects of the intervention compared with a self-help control group on total PA at 6 months. We hypothesize that YACS in the intervention group will demonstrate greater increases in total PA minutes/week at 6 months (post-intervention) relative to those in the self-help group. Secondary aims compare the two groups on maintenance of changes in total PA minutes/week at 12 months, light PA, and moderate-to-vigorous PA minutes/week at 6 and 12 months, and steps per day at 6 and 12 months. The two groups are also compared on change in sedentary behavior, weight, and psychosocial measures (e.g., quality of life).

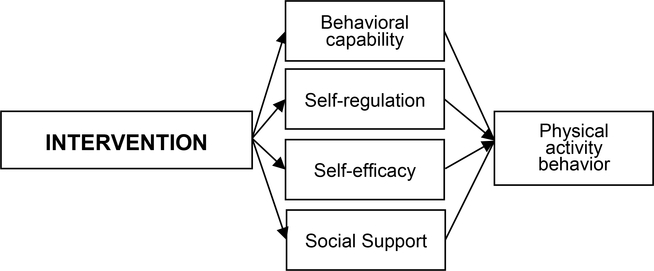

Additional study objectives are to examine whether changes in targeted social cognitive factors (behavioral capability, self-regulation, self-efficacy, perceived social support) mediate intervention effects on PA outcomes and to explore potential moderators of intervention effects, including both demographic (e.g., age, gender) and health-related variables (e.g., cancer type, time since diagnosis, quality of life). The IMPACT trial seeks to promote PA among a vulnerable and underserved population of cancer survivors using a high-reach, technology-based strategy that does not require in-person visits, and thus has potential to be adopted on a larger scale to reduce cancer-related morbidity and disparities.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and overview

The IMPACT study is a 2-arm parallel groups, randomized controlled trial that will enroll and randomly assign 280 YACS to one of two groups: self-help (Digital Tools) or intervention (Digital Tools Plus). Assessments of device-measured PA and other secondary outcomes will be conducted at baseline, 3 (psychosocial and medical events only), 6, and 12 months. Enrollment will occur in multiple cohorts starting every two or four weeks. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Protocol Review Committee of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer and the Institutional Review Board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Study #: 16–3409).

2.2. Study sample

A total of 280 YACS will be recruited and enrolled from around the United States using various recruitment approaches, including direct mailings and advertisements through social media, community-based organizations and clinics. To be eligible, YACS must meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for IMPACT study

| Inclusion criteria |

| • Currently age 18–39 |

| • Diagnosed with invasive malignancy between the ages of 18–39 years |

| • Diagnosed with invasive malignancy in the last 10 years with no evidence of progressive disease or second primary cancers |

| • Completed active cancer directed therapy (cytotoxic chemotherapy, radiation therapy and/or definitive surgical intervention), except may be receiving “maintenance” therapy to prevent recurrences |

| • No pre-existing medical condition(s) that preclude adherence to an unsupervised exercise program |

| • Not adhering to recommendation of at least 150 moderate-to-vigorous physical activity minutes/week (based on self-report and accelerometer-assessed activity) |

| • Have access to the Internet on at least a weekly basis |

| • Have e-mail address or willing to sign up for a free email account (e.g., Gmail) |

| • Have mobile phone with text messaging plan |

| • Ability to read, write and speak English |

| • Willing to be randomized to either arm |

| • Complete baseline accelerometer-assessed activity (i.e., wear 10+ hours on 4 of 7 days) and return of the accelerometer in a pre-paid envelope at baseline |

| Exclusion criteria |

| • History of heart attack or stroke within past 6 months |

| • Untreated hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, unless permission is provided by their health care provider |

| • Health problems which preclude ability to walk for physical activity |

| • Report a diagnosis of psychiatric diseases (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression leading to hospitalization in the past year), drug or alcohol dependency |

| • Report a past diagnosis of or treatment for a DSM-IV-TR eating disorder (anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa) |

| • Plans for major surgery (e.g., breast reconstruction) during the study time frame |

| • Current participation in another physical activity or weight control program |

| • Currently using prescription weight loss medications |

| • Currently pregnant, pregnant within the past 6 months, or planning to become pregnant within the next 6 months |

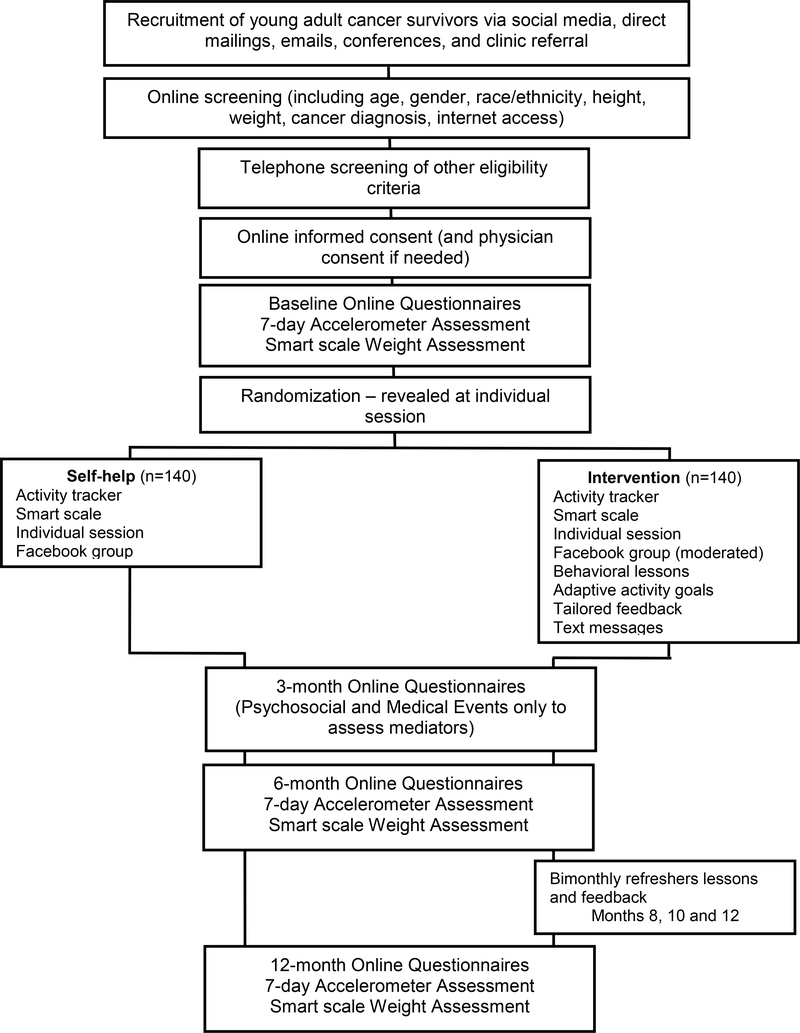

Potential participants will be encouraged to visit a website with study information (purpose, eligibility criteria, time commitment, incentives). Individuals interested in participating follow a link to an online screening survey of basic eligibility. Study staff will contact initially eligible individuals by phone to provide details about study procedures and complete screening. Once an individual is deemed potentially eligible to participate in the study, staff will send interested individuals an email with a unique link to a video that presents details about the research process, an online accelerometer return agreement form, and an online informed consent using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based software platform [30,31]. Individuals who report during the phone screening any medical conditions on the Physical Activity Readiness-Questionnaire (PAR-Q) [32] that could limit exercise (e.g., high blood pressure, bone or joint problems, prescription medication use, and other medical reasons) will be required to obtain written physician’s consent to participate. After consent is obtained, study staff will email individuals a unique link to the baseline questionnaires and instructions for completing a 7-day assessment of their PA using a tri-axial accelerometer (ActiGraph GT3X+, Pensacola, FL) delivered via mail. To be eligible to participate, individuals are required to wear the accelerometer at least 10 hours/day on at least 4 days and return it by mail in a pre-paid envelope. Individuals not meeting the wear criteria will be given a second chance to wear the accelerometer to meet the requirement. Next, participants will be mailed a cellular-enabled smart scale (Body Trace, Inc., New York, NY) to complete their baseline weight measurement, which they retain for future assessments, and an activity tracker (Fitbit Alta or Inspire, San Francisco, CA) for use during the study. After completion of baseline assessments and a cohort of at least 4 participants has accrued, study staff will schedule the participant for a one-on-one telephone/videochat session during which s/he will be informed of group assignment. Figure 1 shows the stages of recruitment and an overview of the study.

Figure 1.

Overview of IMPACT study flow

2.3. Randomization

After completing informed consent, 7-day PA assessment, weight measurement, and baseline questionnaires, participants (N=280) will be randomly assigned with equal probability to 1 of 2 treatment groups: 1) self-help (Digital Tools; N=140) or 2) intervention (Digital Tools Plus; N=140). Randomization will follow a simple schedule using a random numbers list generated in REDCap tools [30,31]. Individuals will be randomized and cohorts initiated every 2 or 4 weeks.

2.4. Conceptual Framework and Intervention Overview

The intervention was designed to enhance our previously tested Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)-based [33,34] Facebook-delivered PA intervention for YACS [24], by incorporating additional self-regulation strategies and behavior change techniques (Figure 2). Previous theory-based PA interventions that targeted SCT constructs have resulted in significant increases in PA among cancer survivors [35–40], and PA interventions addressing self-efficacy (e.g., encouraging attainable goal-setting, reinforcing successes) [38,41,42] and self-regulation (e.g., using PA logs and/or pedometers for self-monitoring) [35,43] have been effective in cancer survivors. Further, several studies have shown an association between social support and PA engagement in cancer survivors [44–46], including our prior intervention for YACS [24,44,47]. Thus, the IMPACT intervention builds on our prior intervention and incorporates a self-regulation framework that targeted PA in a successful weight gain prevention intervention for young adults [48–50]. It will focus on strategies to promote behavioral capability, self-monitoring, self-efficacy, and social support [24,44,47], with an increased emphasis on self-regulation (i.e., monitoring progress through self-monitoring, goal-setting, receiving feedback, self-reward, self-instruction, and enlisting social support) [51]. Intervention participants will be taught to use trackers to: a) self-monitor their activity daily; b) evaluate their progress toward individualized goals; c) implement problem solving strategies if not meeting their goals; d) evaluate the success of these strategies; and e) provide self-reinforcement for successfully meeting activity goals, or make additional changes in their behavior if not meeting goals. In addition, the intervention will seek to promote social support for PA as YACS desire interventions that provide social support [52]. Given the feasibility demonstrated in our prior work [24], we will replicate our previous approach to using Facebook as a program platform.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework

Additionally, intervention components were systematically designed using evidence-based behavior change techniques that were relevant to theoretical determinants and have been commonly targeted by PA interventions and/or shown to have potential for driving PA behavior change [53–58]. Two research team members trained in the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (BCT, v1) used the 93-item taxonomy to code the proposed self-help and intervention components for the presence of BCTs [53]. Following initial coding of the activity tracker and companion app, we used BCTs to guide the development of lesson content, tailored feedback, and Facebook posts, which are described below. Appendix 1 provides an overview of the BCTs used in IMPACT intervention components.

2.5. Self-help (control condition)

Because activity trackers are commercially available and YACS are highly active on social media, the self-help group will receive digital tools that YACS interested in PA might currently access. Studies have shown that providing Fitbit trackers alone have not improved PA outcomes relative to a control group [59,60], and reviews of methodological issues in eHealth research have recommended the use of digital-based comparison conditions instead of usual care or no-treatment controls to move public health research forward [61,62]. Therefore, participants will be provided with a tracker and access to a Facebook group to promote retention. Giving trackers to all participants mimics the comparison group used in our prior study [24] and allows us to examine whether the effects of our theory-based intervention strategies (goal-setting, feedback messages) exceed any potential effects related to the novelty and use of the tracker and companion mobile app [63,64].

2.5.1. Activity tracker with companion mobile app

After completing baseline assessments, all participants will receive an activity tracker (Fitbit Alta or Inspire, San Francisco, CA) through the mail, with instructions on how to use the tracker and companion website or app. These trackers have demonstrated strong validity for measurement of steps and good agreement with energy expenditure (metabolic equivalents; METs) and MVPA from the ActiGraph GT3X+ [65]. Participants will receive an email with instructions on setting up their Fitbit and a unique URL for Fitbit Authentication. This process will prompt participants to login to their Fitbit account and authorize the IMPACT study to access their data. Fitbit data will be collected from the Fitbit application programming interface (API) and transmitted to the study website on secure servers.

2.5.2. Cellular-enabled smart scale

Because young adults have the greatest risk of weight gain over time relative to other age groups [66,67], and a history of cancer can increase risk of weight gain, participants will receive a cellular-enabled smart scale (Body Trace, Inc., New York, NY) through the mail for weight assessments. We will provide these scales to all participants to control for the potential novelty effects of the scale [63,64]. The scales will send weights directly to a website (www.bodytrace.com), and data are transmitted to the study website on secure servers.

2.5.3. Initial individual telephone or videochat session

After receiving the tracker and scale, individuals will participate in an introductory telephone or videochat session, based on participant preference, to discuss current PA recommendations for cancer survivors and review study procedures. Sessions are scripted and will be delivered by one of four study interventionists, who have PhD or master’s level backgrounds in exercise physiology, nursing, health behavior, or nutrition, and previous experience with behavioral weight control trials or exercise with cancer survivors. Prior to the individual session, each participant will receive feedback on their baseline total PA levels, broken down by MVPA, light, and total activity (as measured by daily step count), and sedentary time. The study interventionist will highlight the current PA guidelines for cancer survivors (i.e., at least 150 minutes per week of MVPA minutes/week) and the benefits of light PA (e.g., every 60-minute increase in light PA is associated with a 16% reduction in mortality) [68]. Self-help participants will be told that the study is testing a self-directed approach to increasing PA. They will be informed that the study team will be able to view their PA and weight data and advised to maintain their current self-weighing frequency.

2.5.4. Facebook group

On the program start date, self-help participants will be added to a secret Facebook group with access to usual features (e.g., ability to post comments, links, and videos to the group wall) (one group for all participants enrolled in the Self-help group). The Facebook group will be created with “secret” access, an existing functionality of Facebook groups with the following restrictions: 1) membership is by invitation only; 2) the group does not appear in search results or in the profiles of its members; and 3) any written comments, activity, or posts by participants are visible only to other group members, but not to other Facebook friends. To ensure that all participants are aware of Facebook’s privacy policies and settings, each participant will receive instructions on how to set their privacy preferences on Facebook during the initial session and in a separate emailed document. A study interventionist will announce when a new cohort of participants is added to the group and will monitor participant activity, but will not encourage interaction, so any participant posting or interaction is self-directed.

2.6. IMPACT intervention

2.6.1. Intervention overview

Similar to the self-help group, intervention participants will receive a Fitbit tracker, smart scale, individual telephone or videochat session, and access to an intervention group-only Facebook group. In addition, intervention participants will receive several key components to target our hypothesized intervention mediators and PA determinants—behavioral capability, self-regulation, self-efficacy, and perceived social support—which in turn are theorized to lead to increased PA. The intervention is designed to address the preferences of YACS for programs that offer convenience, flexibility, choice, and social support [22,52]. Table 2 outlines intervention components and the theoretical determinants they are designed to target.

Table 2.

Key IMPACT intervention components targeting theoretical determinants

| Behavioral lessons | Adaptive PA goals based on tracker data | Tailored feedback based on individual data | Text messages (2 standard, 3 adaptive) | Facebook group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Schedule | |||||

| Months 1–3 | Weekly | Weekly | Weekly | 5 texts/week | ≤5 prompts/week |

| Months 4–6 | Biweekly | Weekly | Weekly | 5 texts/week | ≤5 prompts/week |

| Months 7–12 | Bimonthly | Weekly | Bimonthly | 1 text/week | ≤5 prompts/week |

| Theoretical Concept Targeted | |||||

| Behavioral capability | Lessons on PA topics and behavioral strategies | Informational texts about PA and cancer survivorship | Links to behavioral resources | ||

| Self-regulation | Lesson content encourages daily self-monitoring | Weekly goals tailored to abilities and adapted based on previous week’s activity | Gives feedback on self-monitoring frequency Asks participant to evaluate goal appropriateness |

Adaptive texts prompt daily tracking and activity based on changing PA levels | Prompts to share activity goal and achievements Enlisting social support from peers |

| Self-efficacy | Lessons addressing barriers specific to YA cancer survivors (e.g., reputable resources on PA for cancer survivors, overcoming negative thoughts about PA) | Weekly goals tailored to abilities and adapted based on previous week’s activity User has option to change weekly goal |

Gives numeric and graphic visualizations of performance Asks participant to identify barriers Asks about weekly goal and action plan Reinforces goal progress and skill development |

Motivational interviewing-type texts encourage self-reflection and elicit motivation for change Adaptive prompt or reinforcement texts Adaptive texts with behavioral strategies |

Links to stories/videos of cancer survivors in Facebook group that demonstrate successful adoption of PA and overcoming barriers to PA |

| Social support | Lessons on identifying and asking for different types of social support for cancer and PA, navigating changes in family/friend dynamics related to cancer | Link to post on Facebook | Prompts to encourage support Prompts to share activity goal and achievements |

||

2.6.2. Mobile responsive website

Intervention participants will receive access to a mobile responsive website which has separate sections on lessons, resources, feedback, and progress. Resources will include links to publicly available websites with information on PA for cancer survivors from credible sources (e.g., National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Cancer Society, American Society of Clinical Oncology), tips related to exercise safety, and guidance on overcoming barriers. Additional resources will provide links to community organizations focused on young adults with cancer. The other main components of the website, including behavioral lessons, adaptive PA goals, and tailored feedback, are described below.

2.6.2.1. Behavior modification skills and lessons

Links to lessons on the website will be emailed to participants and sent in text message notifications delivered weekly in months 1–3, biweekly in months 4–6, and bimonthly in months 8, 10 and 12. These lessons were developed specifically for YACS, adapted from our prior trial [24] (see Appendix 2 for lesson topics). They will cover behavioral skills, including self-monitoring, problem solving, enlisting social support, goal setting, and cognitive restructuring. The lessons will address specific barriers and concerns identified by YACS, including insufficient information about PA, navigating changes in social relationships, body image, negative thoughts, and restructuring environments to support change [22,69]. Lessons will also include information on prolonged sedentary behaviors, weight management, and daily weighing.

2.6.2.2. Weekly adaptive physical activity goals

Participants will receive a recommendation to gradually increase their total PA each week during the 6-month intervention using activities that they find enjoyable. YACS have indicated preferences for programs that offer flexibility and choice [22,52]; therefore, participants will be given the option to select a personal goal for active minutes/week and steps per day. Given the individual variation in PA abilities and health issues among YACS (e.g., fatigue), adaptive goals support a personalized, gradual, and safe progression. Continuous Fitbit activity data informs dynamic tailoring of PA goals that may vary from week to week based on individuals’ changing PA levels. Suggested weekly active minutes goals will increase by 10% if a participant meets their prior week’s goal, and suggested daily step goals will be individually tailored based on the 60th percentile of steps/day recorded in the prior week, a rank-order percentile algorithm used in previous research [70]. After reading their weekly tailored feedback summary on the website, participants will be given the option to accept the suggested active minutes and steps goals or change them. To reinforce PA goal attainment, we will mail small token rewards (worth $1-$2) to intervention participants who achieve at least 75% of their PA goals on a preset schedule (monthly in months 1–6, bimonthly in months 7–12).

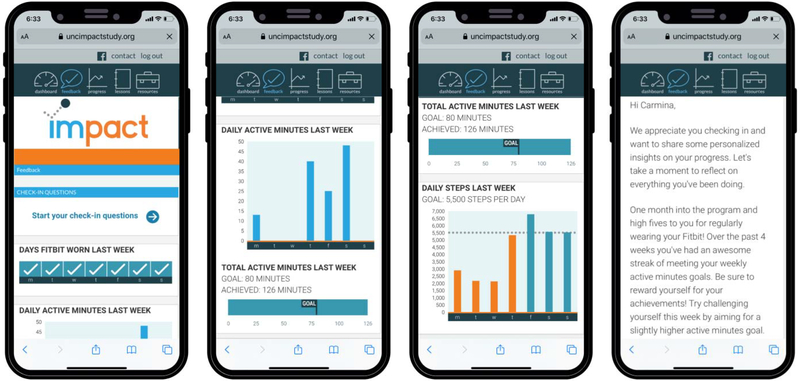

2.6.2.3. Weekly tailored feedback

We will send participants an email and text prompt with a link to access weekly tailored feedback. Participants will receive various types of feedback, including: 1) graphs of individuals’ PA data from the prior week (total “active” minutes (Fitbit equivalent of MVPA), daily active minutes, daily steps, days Fitbit was worn), and 2) a written feedback summary (see Figure 3 for example feedback). Written feedback summaries will be tailored based on individual data derived from the Fitbit, smart scale, and weekly check-in questions posed to participants. Check-in questions will vary by week but consider: 1) expected or experienced benefits); 2) PA enjoyment and exertion; 3) mood and fatigue; and 4) barriers, if activity levels are less than 75% of their weekly active minutes goals for the majority of the previous 3 weeks. Individual activity, weight, and check-in data will be transmitted through the study website and stored on secure servers. Backend programming on the study website will apply computer-tailored algorithms to prepare the feedback summaries.

Figure 3.

Screenshots of IMPACT mobile responsive website with example feedback

Feedback content will be determined by tailoring algorithms that include: participant’s progress toward personal weekly goals; progress toward national guidelines of 150 MVPA minutes/week; changes in mood and fatigue in relation to active minutes achieved; frequency of daily self-weighing; weight compared to baseline; change in sedentary minutes; and suggestions for overcoming barriers or reinforcement. The algorithms use combinations of over 240 tailoring variables to define varying participant conditions and corresponding feedback for a given week. During the first six months, participants will receive a monthly feedback review at four-week intervals.

2.6.3. Text messages

Participants will receive five texts each week as follows: 1) prompt to access the weekly lesson and feedback (Monday); 2) cancer-related motivational or educational information (Wednesday or Thursday); 3) additional adaptive tailored texts based on individual-level PA data from the activity tracker. These texts are sent on a pre-specified day, delivered randomly within one of three timeframes (9am-1pm, 1–5pm, 5–9pm). Text messages provide: 1) motivational messages; 2) behavioral strategies (e.g., problem solving, eliciting support); 3) prompts to engage in PA (frequently performed or new activities, encourage self-reflection in the spirit of motivational interviewing approaches); 4) reinforcement or praise; 5) questions about PA (e.g., enjoyment of last session) (see Appendix 3 for examples). Starting in week 25, intervention participants continue to receive one text per week to prompt engagement with the program.

2.6.4. Facebook group for peer support

To promote interaction and support, participants will be added to a secret Facebook group and advised to post comments that offer encouragement, feedback to peers, their activity goals, and to describe how they achieved their activity goals. Previous studies have used these engagement strategies within Facebook to encourage social support for PA [71]. Each cohort of participants will be added to a single Facebook group for intervention participants. Throughout the program, interventionists will respond to participant-initiated questions and post a variety of prompts up to five times per week (Appendix 4). The posts will include educational or motivational information/videos about PA, stories about peers or role models overcoming PA barriers, and discussion questions about adopting PA behaviors. Over the first 26 weeks of the study, interventionist prompts and comments will be posted on a set schedule and will target specific BCTs commonly used in PA intervention studies [53–58]. The same 26-week schedule, targeting the same BCTs but using slightly modified content, will be repeated over the course of study until the final cohort of participants completes the trial.

One week per month, all intervention participants will be invited to engage in “challenges.” The challenges will involve posting a comment, picture, or video to the Facebook group in response to a question or prompt that is relevant to PA and/or cancer-related experiences. The challenges will reinforce intervention content, encourage peer support and interaction, promote adherence to Facebook intervention activities, and enhance engagement during the year-long study. To encourage participation, individuals who post at least one response to a challenge will receive an entry into a chance drawing of $20, which occurs at the end of each challenge week. Participants will be limited to one entry per month and will have the opportunity to engage in up to twelve challenges.

2.6.5. Maintenance

After completion of the initial 6-month intervention, participants will receive lessons and tailored feedback summaries every other month (weeks 34, 43, 52; Appendix 2). Lessons will encourage participants to evaluate their exercise identity and to develop their personal narrative as it relates to their experiences in IMPACT and with PA. The final lesson will be about reflecting on progress made during IMPACT, key skills taught during the program, and applying those skills to other parts of life. Text messages will be sent every Monday and will include a motivational message and a reminder to sync the activity tracker or log into the study website.

2.7. Outcome Measures

Study measures will be assessed online by self-report questionnaires, objectively through devices mailed to participants, or over the telephone by trained staff members. Participants will be asked to complete assessments at 4 time points: baseline, 3 months, 6 months (post-intervention), and 12 months (follow-up) (see Appendix 5). At each assessment, participants will receive an email with a unique link to online surveys. They will take 30–45 minutes to complete and can be done in multiple sessions if necessary. Seven-day accelerometer assessments, objective weight measurement, and online surveys will occur at baseline, 6 (post-intervention), and 12 months (follow-up). At 3 months, only psychosocial measures and medical events will be collected via online survey. Participants will receive $25 (baseline), $10 (3 months), $50 (6 months), and $75 (12 months) for completing assessments.

2.7.1. Behavioral measures

Device-measured physical activity.

The primary outcome—accelerometer-measured bouts of total PA minutes/week (sum of light, moderate, and vigorous PA)—is assessed using the ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometer (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL) [72]. Total PA was selected based on findings from our prior work [24] (see 2.10 Sample Size Calculation), and given the challenges of meeting MVPA guidelines, and emerging health benefits of light PA for cancer survivors [73–75]. Accelerometers will be mailed with instructions on proper wear and a pre-paid envelope for returning the monitor. Participants will be instructed to wear the device on their non-dominant wrist at all times for 7 days. Within a week of return, data from the device will be downloaded and reviewed for adequate wear. Participants will be asked to re-wear the accelerometer if they do not have 4+ days, at least one weekend day and two weekdays, with 10+ hours of waking wear [76]. Waking wear will be identified using standard wear/non-wear and sleep/wake detection algorithms, logs, and visual inspection [77,78]. Physical activity outcomes will be computed by applying standard cut-points and bout counting algorithms to data files containing time stamped vector magnitude estimates for each minute participants wore the device [79–81]. Total and bout minutes of sedentary, light, moderate, and vigorous activity will be aggregated to the day- and participant-level for analysis. Bouts of total and MVPA activity will be defined as sustained vector magnitude at or above cut-off for at least 10+ minutes with allowance for 20% below threshold (i.e., 2 of 10 minutes) and less than 5 consecutive minutes below cut-off [78,82]. Outcome variables will be adjusted for accelerometer wear-time in analyses. Activity data (active minutes, steps per day, sedentary minutes) will be collected throughout the study from the participant’s Fitbit, using the Fitbit API (Application Program Interface), and are stored in encrypted files on servers that adhere to the University policy on storage of sensitive data.

Self-reported physical activity will be assessed using a modified version of the leisure score index of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire, which has demonstrated reliability and validity when compared to several other self-report exercise measures and objective measures in different populations [83–85]. Participants report frequency of light, moderate and vigorous exercise, and average duration (minutes) during a typical week [83,86]. Given the increasing recognition of the association between sedentary behavior and health outcomes in cancer survivors [87], sedentary activity will be assessed with the Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire [88], which asks participants to indicate the number of hours they spend on a typical weekday and weekend day doing 8 different sedentary activities (e.g., sitting while watching television, sitting and talking on the phone). Responses range from “None” to “6 hours or more.” Test-retest reliability coefficients have ranged from 0.51 to 0.93 [88].

2.7.2. Anthropometric measures

Weight will be objectively measured by the participants using the smart scale that is mailed to them during the baseline assessment [48]. Participants will be instructed to weigh themselves in light clothing, without shoes, three times in a row, upon waking and before eating, at each assessment time point. The three weights will be averaged at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Percent weight change will be computed as a secondary outcome. Height will be self-reported at baseline using a single item from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey [89], adapted for use in the NCI’s Health Information and National Trends Survey [90]. Self-reported height has shown to be highly correlated with measured height in young adults [91]. Height and weight will be used to calculate body mass index (kg/m2).

2.7.3. Cognitive/psychosocial measures

Cognitive/psychosocial measures will assess hypothesized intervention mediators: 1) behavioral capability using six items [92] about PA knowledge and skills; 2) self-efficacy for exercise using the 12-item Self Efficacy and Exercise Habits Survey [93]; 3) self-regulation with the 10-item Exercise Goal-Setting Scale and the 10-item Exercise Planning and Scheduling Scale developed for young adults [94] and total number of days of PA tracked and goals set collected from the activity tracker and study website; 4) social support for exercise using the 13-item Social Support for Exercise Survey [95], with three subscales related to friend support, family support, and family rewards and punishment, and one subscale we adapted to ask friends on social networking sites [44]. Additional psychosocial outcomes that have shown improvements related to PA engagement among cancer survivors in previous studies [10] will be measured: 5) health-related quality of life using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) [96]; 6) well-being with the validated Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G, version 4, 2007) scale survey [97–99]; 7) mood states using the 30-item Profile of Mood States-Brief Form (POMS-BF) [100]; 8) depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [101]; and 9) cognitive function using the 20-item perceived cognitive impairment (PCI) subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT- Cog, Version 3) survey [102].

2.7.4. Supporting measures

Several supporting measures will be assessed, including sociodemographics and health history, with questions about cancer type, stage, time since diagnosis, treatment type, and medications. Facebook connectedness will be measured using the 20-item Facebook Connectedness Scale [103], adapted to measure social connectedness derived from using the IMPACT Facebook group. At 12 months, financial stressors will be assessed with 6 items regarding behaviors related to finances in the past year (e.g., “borrow money to help pay bills,” “miss payments on bills”) [104], and life events will be assessed with the Life Events questionnaire from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, which asks about 67 common events for young adults that may have occurred in the past year [105].

2.7.5. Process and adherence measures

Adherence to meeting the PA guidelines of 150 min/week of MVPA for cancer survivors [106] will be computed using accelerometer-measured weekly duration of MVPA. PA monitoring will be assessed via Fitbit tracker data. Frequency and number of activity tracking days will be tabulated to derive a measure of percent of days in which activity was tracked (i.e., defined as ≥1000 steps [107,108]) and average activity tracking days per week. Self-weighing habits will be objectively measured via cellular-enabled smart scales. Time-stamped weight data are tabulated to derive a measure of percent of days in which weight was recorded and average self-weighing days per week. Data on website logins, lessons accessed, goals set or modified, and engagement with text messages will also be available. Facebook engagement will be measured using the 8-item Facebook Intensity Scale [109], which asks participants about their attitudes and use of Facebook, and we will collect objective measures of interactions within the Facebook group over the course of the study. Study staff will monitor and record all individual posts (e.g., comments, videos, pictures) and interactions (e.g., likes, views, shares) within the Facebook groups. All participant-generated content will be logged in a password-protected database that includes date, time, topic, modality, and a unique participant ID. Additional measures regarding Facebook and Fitbit use will include questions about becoming friends with other IMPACT participants, frequency of Fitbit website/mobile app use, and participation in Fitbit groups and challenges with other IMPACT participants.

To characterize recruitment and participation, we will examine completion of the screening questionnaires and enrollment in the study. Data will be collected on engagement with social media advertisements (e.g., impressions, likes, shares, comments, link clicks) and the recruitment website landing pages (e.g., page views, screening questionnaire link clicks) through Facebook and Google analytics. To assess program acceptability and satisfaction, participants will complete a post-treatment program evaluation asking about perceptions and experiences with the intervention and program components. Measures are adapted from our previous studies [24,48,110] and will assess intervention exposure and attention, perceived personal relevance, recall, credibility, how applicable the intervention was for making healthy changes, and satisfaction with intervention components.

2.8. Safety and medical events monitoring

Medical events will be collected using a medical events questionnaire administered at each assessment after baseline and during any participant-initiated contact between assessments. Reported events will be reviewed by study personnel to determine whether the issue may affect participant safety or outcomes (e.g., pregnancy), appears to be related to the intervention, and/or is a serious adverse event. We will also monitor any musculoskeletal problems that develop during the intervention (e.g., broken bones), and determine whether these appear related to the intervention. Participants who develop musculoskeletal or other health problems that may affect their safety will be instructed to stop exercising and not resume until cleared by their health care provider.

To minimize the risk of potentially inappropriate or harmful comments within the Facebook group, the informed consent will provide guidelines for communication in the group. Participants will be reminded of these guidelines and the Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities [111] during the individual session at the beginning of the study and in the Facebook groups. Participants will be encouraged to contact the Principal Investigator if they feel they have experienced any emotional distress as a result of study participation.

Individuals scoring >16 on the CES-D [101] during assessments (indicating levels of depressive symptoms that might benefit from follow up with a health care provider) will be given a letter explaining the survey that will include referrals to survivor-specific support resources (e.g., UNC Comprehensive Cancer Support Program for psychological counseling, LIVESTRONG Navigation, CancerCare Counseling). Though PA is encouraged during most pregnancies, participants who become pregnant during the study will be withdrawn and intervention will be stopped since consultation with a health care provider and more tailored recommendations for pregnant women regarding PA and weight management may be needed.

2.9. Procedures for minimizing dropouts and improving retention

Participants will be sent an email reminder before each assessment, and at baseline we will collect names and addresses of several friends and family members who can be contacted if we lose touch with the participant. We will prompt non-responders to complete surveys via email and make follow-up phone calls if necessary. Because activity tracker data drive message algorithms and determine tailored feedback and text message content, a high priority will be placed on encouraging participants to wear their tracker and regularly sync it with their Fitbit app. In the first two weeks of the study, text messages focused on ensuring tracker wear adherence will be deployed at least three times a week and then taper to up to once per week over the course of the study. To alert study staff to participant lapses in adherence to activity tracking and weighing and the possible need for additional intervention regarding technical issues, the study website will be programmed to send alert emails to the study team and generate a report of participant lapses. If any lapses occur in the first two months of study participation, study staff will send an email inquiring about any technical problems and reminding participants about the importance of logging into the website.

2.10. Sample size calculation

The study is powered to detect differences between the intervention and self-help groups on the primary outcome of total PA min/week at 6 months. Sample size was estimated based on the increase in total PA and effect size observed in our prior study (161 min/week, d=0.39, 23% attrition), which was driven by a clinically meaningful increase of 135 min/week in light PA [24], as evidence demonstrates a 16% decreased risk in all-cause mortality associated with every 60-minute increase in light PA [68]. We anticipate that PA min/week will decline by 12 months, but expect to be powered to detect smaller changes at 12 months. With 280 total participants (140 per group), we conservatively estimated that 25% of participants will be lost to follow-up at 6 months, with approximately 210 participants remaining at 6 months. With 105 participants per group, we will have 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.39 (α= 0.05, two-tailed test). This effect size may be seen if the difference in means is 160 minutes/week (common SD of 410).

2.11. Analysis plan

Data analyses will be performed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.4, Cary, NC). For baseline survey data, analyses will explore associations between demographic, psychosocial, health-related, and PA outcomes of participants to identify important covariates to include in multivariable analyses. Chi-square tests for categorical outcome variables and t-tests/ANOVA for continuous variables will be used to assess differential attrition by comparing dropouts to completers on demographic characteristics and baseline dependent variables. If the combined rate of missingness on predictor variables is <5%, missing data will not be replaced. For higher levels (≥5%) we will compare missingness across other observed variables to determine if data can be assumed missing at random. If so, multiple imputation will be used.

2.11.1. Analysis of primary outcome

We will evaluate the efficacy of the intervention by comparing differences between the intervention and self-help group in total PA min/week at 6 (primary outcome) and 12 months (secondary outcome). Using maximum likelihood methods, linear and logistic mixed model analyses with repeated measures will be utilized to test for statistical differences between groups in changes over time. Models will be adjusted for education, time since diagnosis, and age. We will employ an intention-to-treat analysis approach including data from all participants. Modeling will also account for effects of shared components between groups, and interactions will be investigated to evaluate these relationships.

2.11.2. Analysis of whether changes in social cognitive factors mediate intervention effects on PA outcomes

We hypothesize that changes in SCT constructs from 0 to 3 months will mediate intervention effects at 6 and 12 months. We will conduct mediation analyses using bootstrapping methods [112] and the product-of-coefficient test (α×β) [113] to evaluate the significance of the mediated (indirect) effect. Using a SAS macro by Preacher and Hayes [114], we will compute a series of multiple regression models: 1) PA change at 6 (or 12) months on the intervention variable (total effect of intervention on PA); 2) change scores of potential mediators from 0 to 3 months on the intervention condition (α); and 3) PA change at 6 (or 12) months on the intervention condition while controlling for potential mediators (β, direct effect of intervention on PA). The indirect effects will estimate the effect of the treatment condition while controlling for the effect of potential mediators (behavioral capability, self-regulation, self-efficacy, perceived social support) on PA. If there is no intervention effect on changes in a potential mediator, we will conduct linear regression analyses with the total sample to examine whether changes in SCT constructs were associated with changes in PA.

2.11.3. Exploratory analysis of potential moderators

Analyses will examine whether intervention effects differ across potential moderators, including demographic (e.g., age, gender) and health-related (e.g., quality of life) characteristics. We will use the same modeling approaches outlined above and examine the statistical significance of an interaction term (potential moderator × intervention) in mixed model analyses.

2.12. Data and safety monitoring committee

This study will be reviewed annually by the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) to ensure appropriate safety oversight as per the National Cancer Institute-approved Lineberger Data and Safety Monitoring Plan. The DSMC meets monthly, with ad hoc review and additional meetings called when necessary and includes a chair, vice chair, and representation from biostatisticians and clinical researchers. Any protocol modifications will be submitted and reviewed by the UNC Lineberger Protocol Review Committee and UNC Institutional Review Board, and documented in trial registries.

3. Discussion

The IMPACT randomized controlled trial is testing an innovative, 6-month, theory-based mobile approach to promoting PA in YACS followed by an additional 6 months of tapered contacts. Intervention approaches and delivery channels enable study participation from across the United States. In this study, we compare a self-help group that receives commonly used digital tools (activity tracker, wireless scale, Facebook group) with an intervention group that receives additional theory- and evidence-based behavioral content, driven by ongoing data collected through these tools, and delivered through a mobile responsive website, text messages, and BCT-specific prompts in the Facebook group. We hypothesize that the intervention group will be more effective than the self-guided group in promoting total PA at 6 months.

To date, there have been few PA interventions designed specifically for YACS. Furthermore, existing studies have been limited by the use of self-reported PA outcomes, small sample sizes, short duration, and lack of effects on MVPA. The IMPACT trial will be the longest large-scale PA trial to date among YACS, a vulnerable and underserved subgroup of survivors who are at risk for chronic conditions, desire PA programs, and prefer remotely-delivered health interventions. Innovative features of the study mean that findings will provide critical information about: the effect of a theory-based, mobile PA intervention for YACS that makes use of widely available commercial technologies (activity trackers, wireless scales, Facebook); use of continuous activity tracker data and participant input to support adaptive goal-setting and deploy real-time tailored text messages and feedback; adoption and maintenance of PA in YACS; and reaching YACS around the United States using a program with potential for scalability.

Although we previously used Facebook as the primary channel to deliver a PA intervention for YACS [24], and systematic reviews indicate the potential of social media interventions to promote behavior change [115–117], there is limited evidence to guide the use of this medium for improving outcomes in YACS. With the rolling addition of participant cohorts to the same Facebook group, large sample, and systematic BCT-specific approach to providing content, IMPACT will contribute significantly to the literature about the use of Facebook among YACS. Additionally, the characterization of unprompted interactions in the self-guided group will shed light on a potential low-intensity approach to using Facebook to promote peer support among YACS. This study also tests a popular social networking site in combination with other delivery platforms, addressing a current research gap related to successful approaches for incorporating social networking sites with other mobile media [117].

The use of widely available activity trackers and smart scales is another strength and innovation of IMPACT that enables continuous data collection to drive adaptive tailored content based on objective measures, facilitates reach of YACS nationwide, and improves potential for scalability. Although early interventions using wearable trackers have shown potential for promoting increased PA [118–120], there is limited evidence on how to effectively use wearable trackers to increase PA [121,122]. Commercially-available trackers use BCTs to varying degrees [123], and use of a wearable tracker alone may not be sufficient to promote regular PA over time. The IMPACT intervention capitalizes on continuously-monitored tracker data and participant input to support adaptive goal-setting and deploy adaptive tailored feedback. Adaptive goals that dynamically change in response to individual’s activity levels to support more achievable goals and a gradual progression over time have been previously tested in the context of PA interventions [124,125], but have yet to be examined among YACS. Together with tailored texts that provide real-time, actionable support, and suggest evidence-based behavioral strategies when needed, these data-driven intervention components take into account unique needs, variability in activity levels, and individual preferences of YACS.

There are potential limitations to the IMPACT study. Since YACS may be connected to their peers via social media and learn about the study from common sources in the young adult cancer community, there is potential for contamination. This is mitigated by the fact that intervention enhancements of interest, such adaptive goal-setting and feedback, will be uniquely tailored to individuals. Additionally, our sample may not be representative of all YACS in the United States given our recruitment approaches. Although participants will be limited to those with mobile phones and internet access, prevalence of mobile phone use, text messages, and Internet use are highest among young adults [126], thereby extending generalizability of our findings. While previous PA trials among cancer survivors have traditionally used waist-worn accelerometers for measurement, we have opted to use wrist-worn accelerometers, which may not accurately record some activities (e.g., cycling, weightlifting). However, wrist wear is becoming the standard placement for assessing 24-hour movement patterns and may improve compliance [127], and wrist placement is consistent with Fitbit wear. Finally, since both groups are receiving digital tools, the implementation of multiple behavioral strategies in the IMPACT intervention and lack of a true control group limit our ability to isolate the effects of the enhanced intervention components. Thus, any effects of the IMPACT intervention will need to be considered in the context of being conditioned on the shared components between groups and their interactions with the non-shared components. Further research will need to dismantle or test the main effects of each component.

By using a systematic approach to coding and targeting BCTs through digital tools (Fitbit, companion app) and intervention content (e.g., lessons, Facebook posts), the IMPACT study is well-poised to contribute to the literature regarding how to build theory and evidence-based enhancements around the existing features of wearable trackers in ways that promote increased PA. The technology-based IMPACT intervention was designed for scalability and to extend reach around the United States. Thus, if this intervention approach is successful in promoting PA in YACS, this high-reach, technology-based intervention has potential for dissemination beyond research settings and to reduce cancer-related morbidity.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the students of the UNC Weight Research Program for their valuable support, including Lex Hurley, Susanna Choi, Miriam Chisholm, Kayla Warechowsi, and Juhi Chinthapatla, who provided excellent research assistance. We wish to acknowledge Dr. Eliza Park, Dr. Andrew Smitherman, Lauren Lux, and community-based organizations, that graciously assisted with study recruitment. We are most grateful to the young adult cancer survivors who participated in the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA204965) awarded to Carmina Valle and the UNC Connected Health for Applications and Interventions Core (funded by the Gillings School of Global Public Health Nutrition Obesity Research Center (National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded; P30DK056350), the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute funded; P30CA016086), and the University Cancer Research Fund). Lindsey Horrell was supported by the UNC Cancer Health Disparities Training Program (National Institutes of Health/ National Cancer Institute funded; T32CA128582), and Erin Coffman was supported by the UNC Nutrition Training (National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease funded; 5T32DK007686).

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Behavior Change Techniques and Domains Used in IMPACT Trial

| Domain | BCTs in Self-help Control Componentsa | BCTs in IMPACT Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.1 Goal setting (behavior) 1.3 Goal setting (outcome) 1.4 Action planning 1.6 Discrepancy between current behavior and goal* |

1.1 Goal setting (behavior) 1.2 Problem solving 1.3 Goal setting (outcome) 1.4 Action planning 1.5 Review behavior goal(s) 1.6 Discrepancy between current behavior and goal 1.7 Review outcome goal(s) |

| 2 | 2.2 Feedback on behavior 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behavior 2.7 Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior |

2.2 Feedback on behavior 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome(s) of behavior 2.7 Feedback on outcome(s) of behavior |

| 3 | 3.1 Social support (unspecified) 3.2 Social support (practical)* 3.3 Social support (emotional)* |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) 3.2 Social support (practical) 3.3 Social support (emotional) |

| 4 | 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behavior | 4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behavior |

| 5 | 5.1 Information about health consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences* |

5.1 Information about health consequences 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.4 Monitoring of emotional consequences 5.6 Information about emotional consequences |

| 6 | 6.1 Demonstration of the behavior* 6.2 Social comparison* |

6.1 Demonstration of the behavior 6.2 Social comparison |

| 7 | 7.1 Prompts/cues* | 7.1 Prompts/cues |

| 8 | 8.1 Behavioral practice/rehearsal* 8.2 Behavior substitution* 8.4 Habit reversal* |

8.1 Behavioral practice/rehearsal 8.2 Behavior substitution 8.3 Habit formation 8.4 Habit reversal |

| 9 | 9.1 Credible source | 9.1 Credible source 9.2 Pros and Cons |

| 10 | 10.3 Non-specific reward* 10.4 Social reward* 10.10 Reward (outcome)* |

10.1 Material incentive (behavior) 10.2 Material reward (behavior) 10.4 Social reward 10.7 Self-incentive 10.9 Self-reward 10.10 Reward (outcome) |

| 11 | 11.2 Reduce negative emotions* | 11.2 Reduce negative emotions |

| 12 | 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment* 12.5 Adding objects to the environment |

12.1 Restructuring the physical environment 12.2 Restructuring the social environment |

| 13 | 13.1 Identification of self as role model 13.2 Framing/reframing 13.4 Valued self-identity 13.5 Identity associated with changed behavior |

|

| 15 | 15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability 15.2 Mental rehearsal of successful performance 15.3 Focus on past success 15.4 Self-talk |

|

| 16 | 16.2 Imaginary Reward |

Self-help control components include Fitbit activity tracker with companion mobile app, individual session, Facebook group without prompts.

IMPACT intervention components include Fitbit activity tracker with companion mobile app, individual session, Facebook group with prompts, behavioral lessons, adaptive physical activity goals, tailored feedback, text messages.

Coders separately coded the Fitbit device, companion app, and website. Participants in the Self-help control group are not directly exposed to these BCTs through the intervention, however, exposure is possible if they choose to use these features of Fitbit.

Appendix 2.

Lesson topics for IMPACT intervention

| Week | Lesson Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | Establish your WHAT and WHY |

| 2 | Structure your activity routine |

| 3 | Adapt your activity |

| 4 | Self-regulate your physical activity and weight |

| 5 | Set S.M.A.R.T. Goals |

| 6 | Overcome barriers |

| 7 | Strengthen your support network |

| 8 | Build a brighter body image |

| 9 | Transform negative thoughts |

| 10 | Decrease sedentary behavior |

| 11 | Manage slips in your activity routine |

| 12 | Prevent and manage stress |

| 14 | Manage your time |

| 16 | Maintain your motivation |

| 18 | Balance your energy intake and physical activity for healthy body weight |

| 20 | Explore resistance training |

| 22 | Practice positive reinforcement |

| 24 | Explore a mindful perspective on how you move your body |

| 25 | Refocus, renew, and refresh your active journey |

| 34 | Evaluate your exercise identity |

| 43 | Your IMPACT story and the next chapter |

| 52 | My life-long IMPACT |

Appendix 3.

Example text messages in IMPACT intervention

| Possible Day of Week | Behavioral Focus | Message Type | Example Message |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Lesson | Standard | Good morning! Check out your week 3 feedback [HYPERLINK]. Want to know how to adapt your activity based on how you are feeling? Read this week’s lesson and learn about what may be shaping your view of physical activity. |

| Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, Sun | Tracker | Prompt | Hey there! It looks like you have not synced your Fitbit yet today. Did you leave it at home? Try to wear it and sync up regularly to stay on track with your progress. |

| Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, Sun | Daily active minutes | Reinforcement | Way to get some active minutes in today! Commit to meeting your weekly goal and celebrate your success! |

| Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat, Sun | Daily steps | Behavioral strategy | Good morning! You nearly hit your step goal yesterday. Make it happen today by connecting with a frequent cue like checking your email or going to the bathroom to prompt you to take some extra steps. |

Appendix 4.

Example Facebook posts in IMPACT intervention

| Type | Example Post | Behavior Change Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Discussion Question and Photo | Physical activity has been shown to have an impact on self-esteem and body image. What are some ways being more physically active has positively affected your life? What successes have encouraged you? (Photo) | • 5.3 Information about emotional consequences |

| Poll | When we strive to make healthy changes, sometimes we direct our focus on what’s not working. If you didn’t perfect your goal you may feel left out of the success huddle. Even if you are at 50% of your goal, you are on your way! Let’s embrace a growth mindset and focus on what strategies are helping you move towards your goal. | • 1.2 Problem solving • 3.2 Social support (practical) • 13.2 Framing/reframing |

| Pick one or more strategies that are helping you move more and move forward: • Wearing my Fitbit every day • Receiving feedback from IMPACT • Scheduling my exercise for the week • Breaking up my exercise into 10–15 minute bouts • Exercising with a partner • Listening to music or podcasts while I exercise |

||

| Discussion Question | As a cancer survivor, what strengths do you have now that you didn’t before that will help you on your fitness journey? | • 13.4 Valued self-identity • 15.4 Self talk |

Appendix 5.

Data collection schedule for IMPACT trial

| Month | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 0 (Baseline) | 3 | 6 (Post-intervention) | 12 (Follow-up) | |

| Behavioral | |||||

| Physical activity (accelerometer, primary outcome) | X | X | X | ||

| Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire | X | X | X | ||

| Steps per day (Fitbit) | X | X | X | X | |

| Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire | X | X | X | ||

| Anthropometric | |||||

| Weight (Body Trace scale) | X | X | X | ||

| Height (self-report) | X | ||||

| Cognitive/psychosocial | |||||

| Behavioral capability | X | X | X | X | |

| Self-efficacy for exercise | X | X | X | X | |

| Self-regulation | X | X | X | X | |

| Social support for exercise | X | X | X | X | |

| Health-related quality of life (SF-36) | X | X | X | X | |

| Well-being (FACT-General) | X | X | X | X | |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D) | X | X | X | X | |

| Mood (Profile of Mood States-SF) | X | X | X | X | |

| FACT-Cognitive | X | X | X | X | |

| Other questionnaires | |||||

| Demographics, health history | X | ||||

| Medication use, smoking, alcohol use | X | X | X | X | |

| Medical events | X | X | X | ||

| Facebook connectedness | X | X | X | ||

| Financial stressors | X | ||||

| Life events | X | ||||

| Process and adherence | Throughout Months 1–12 | ||||

| Physical activity monitoring (Fitbit) | |||||

| Self-weighing (Body Trace scale) | |||||

| Website use | |||||

| Facebook use | X | ||||

| Text message use | |||||

| Program acceptability and satisfaction | X | X | |||

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03569605

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66: 271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. | American Cancer Society [Internet]. [cited 5 Dec 2019]. Available: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2019.html

- 3.Tai E, Buchanan N, Townsend J, Fairley T, Moore A, Richardson LC. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118: 4884–4891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Fasciano K, Ganz PA, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015;20: 186–195. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health US, Human Services (US HHS) NI of H National Cancer Institute &LIVESTRONG™ Young Adult Alliance. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication 06–6067; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4: 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong DYT, Ho JWC, Hui BPH, Lee AM, Macfarlane DJ, Leung SSK, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344: e70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones LW, Liang Y, Pituskin EN, Battaglini CL, Scott JM, Hornsby WE, et al. Effect of exercise training on peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2011;16: 112–120. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14: 1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51: 2375–2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craft LL, Vaniterson EH, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW, Courneya KS. Exercise effects on depressive symptoms in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21: 3–19. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rogers LQ, Alfano CM, Thomson CA, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Practical clinical interventions for diet, physical activity, and weight control in cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65: 167–189. doi: 10.3322/caac.21265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballard-Barbash R, Hunsberger S, Alciati MH, Blair SN, Goodwin PJ, McTiernan A, et al. Physical activity, weight control, and breast cancer risk and survival: clinical trial rationale and design considerations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101: 630–643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabin C, Politi M. Need for health behavior interventions for young adult cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34: 70–76. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2010.34.1.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med. 2005;40: 702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips-Salimi CR, Andrykowski MA. Physical and mental health status of female adolescent/young adult survivors of breast and gynecological cancer: a national, population-based, case-control study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21: 1597–1604. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1701-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zebrack B Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17: 349–357. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0469-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zebrack B, Hamilton R, Wilder Smith A. Psychosocial outcomes and service use among young adults with cancer. Seminars in oncology. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, Embry L, Aguilar C, Meeske KA, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119: 201–214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keegan THM, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, Kent EE, Wu X-C, West MM, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6: 239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murnane A, Gough K, Thompson K, Holland L, Conyers R. Adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: exercise habits, quality of life and physical activity preferences. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23: 501–510. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2446-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabin C, Simpson N, Morrow K, Pinto B. Behavioral and Psychosocial Program Needs of Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Qualitative health research. 2011;21: 796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bélanger LJ, Plotnikoff RC, Clark A, Courneya KS. A Survey of Physical Activity Programming and Counseling Preferences in Young-Adult Cancer Survivors. Cancer nursing. 2012;35: 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, Allicock M, Cai J. A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7: 355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabin C, Dunsiger S, Ness KK, Marcus BH. Internet-Based Physical Activity Intervention Targeting Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1: 188–194. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.0040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin C, Pinto B, Fava J. Randomized trial of a physical activity and meditation intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016;5: 41–47. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bélanger LJ, Kerry Mummery W, Clark AM, Courneya KS. Effects of Targeted Print Materials on Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Young Adult Cancer Survivors During and After Treatment: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2014;3: 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugh G, Hough R, Gravestock H, Davies C, Horder R, Fisher A. The development and user evaluation of health behaviour change resources for teenage and young adult Cancer survivors. Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5: 9. doi: 10.1186/s40900-019-0142-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devine KA, Viola AS, Coups EJ, Wu YP. Digital health interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018;2: 1–15. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42: 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95: 103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q). Canadian Journal of Sport Sciences. 1992;17: 338–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandura A Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52: 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinto BM, Ciccolo JT. Physical activity motivation and cancer survivorship. Physical Activity and Cancer. 2011; 367–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto BM, Floyd A. Methodologic issues in exercise intervention research in oncology. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23: 297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, Courneya KS, Lubans DR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9: 305–338. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0413-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, Trunzo JJ, Marcus BH. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23: 3577–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, Markwell S, et al. A randomized trial to increase physical activity in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41: 935–946. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818e0e1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25: 2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosher CE, Fuemmeler BF, Sloane R, Kraus WE, Lobach DF, Snyder DC, et al. Change in self-efficacy partially mediates the effects of the FRESH START intervention on cancer survivors’ dietary outcomes. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17: 1014–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosher CE, Lipkus I, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Lobach DF, Demark-Wahnefried W. Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START trial: exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors’ maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psycho-Oncology. 22 (4) (2013) 876–885, doi: 10.1002/pon.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabin C, Pinto BM, Frierson GM. Mediators of a Randomized Controlled Physical Activity Intervention for Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2006;28: 269. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, Allicock M, Cai J. Exploring Mediators of Physical Activity in Young Adult Cancer Survivors: Evidence from a Randomized Trial of a Facebook-Based Physical Activity Intervention. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;4: 26–33. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barber FD. Social Support and Physical Activity Engagement by Cancer Survivors. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2012;16: 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonough MH, Beselt LJ, Daun JT, Shank J, Culos-Reed SN, Kronlund LJ, et al. The role of social support in physical activity for cancer survivors: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2019; doi: 10.1002/pon.5171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]