Abstract

Although millions of people are diagnosed with cancer each year, survival has never been greater thanks to early diagnosis and treatments. Powerful chemotherapeutic agents are highly toxic to cancer cells, but because they typically do not target cancer cells selectively, they are often toxic to other cells and produce a variety of side effects. In particular, many common chemotherapies damage the peripheral nervous system and produce neuropathy that includes a progressive degeneration of peripheral nerve fibers. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) can affect all nerve fibers, but sensory neuropathies are the most common, initially affecting the distal extremities. Symptoms include impaired tactile sensitivity, tingling, numbness, paraesthesia, dysesthesia, and pain. Since neuropathic pain is difficult to manage, and because degenerated nerve fibers may not grow back and regain normal function, considerable research has focused on understanding how chemotherapy causes painful CIPN so it can be prevented. Due to the fact that both therapeutic and side effects of chemotherapy are primarily associated with the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress, this review focuses on the activation of endogenous antioxidant pathways, especially PPARγ, in order to prevent the development of CIPN and associated pain. The use of synthetic and natural PPAR а agonists to prevent CIPN is discussed.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, neuropathy, hyperalgesia, PPARγ, reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

Cancer continues to be a leading cause of death worldwide, second only to cardiovascular disease. Thankfully, sensitive tests for early diagnosis and powerful chemotherapeutic treatments have increased cancer survival significantly. However, chemotherapies are associated with serious side effects that cause additional suffering for patients and reduce their quality of life. Drug resistance and the side effects of chemotherapy, particularly painful peripheral neuropathy, represent major obstacles to the successful treatment of cancer. Here we review the roles of reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in the development of chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy, and the activation of endogenous antioxidant pathways, specifically peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) signaling, as a potential approach to protect peripheral nerves from the damage caused by chemotherapy.

Many chemotherapeutic agents cause damage to the peripheral nervous system [1]. There are six classes of chemotherapies that cause nerve damage. These are platinum-based drugs, vinca alkaloids, taxanes, epothilones, proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory therapies. The platinum-based agents, taxanes, epothilones, and proteasome inhibitors are the most toxic to the nervous system. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) represents a variety of neuropathies that involve large and small nerve fibers, and can include sensory, motor and autonomic fibers, often resulting in demyelination and axonal degeneration. Sensory neuropathy is the most common type of neuropathy from chemotherapy [2,3]. Sensory symptoms are most intense distally in the feet and hands with a “glove and stocking” distribution. Symptoms typically include impaired tactile sensation and numbness, tingling, paresthesia and dysesthesia [4]. Moreover, the neuropathy can be painful with sensations of burning, shooting or electric shock-like pains as well as mechanical or thermal hyperalgesia that result from activation and sensitization of nociceptors [5–9]. Motor symptoms occur less frequently than sensory symptoms and include muscle weakness, as well as disturbances in gait, balance and movement [10]. Collectively, these symptoms are the major dose-limiting side effect of chemotherapy [11] and can persist for years after chemotherapy treatment has ended [12].

The prevalence and severity of CIPN is dependent on many factors including the chemotherapeutic agent, combinations of chemotherapies, single and cumulative doses, duration of therapy, age, coexisting neuropathy (for example, diabetic neuropathy), genetic susceptibility, and alcohol abuse. The incidence and severity of CIPN vary considerably among agents when administered alone or in combination, but for vincristine, cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and paclitaxel, estimates for the occurrence of CIPN are as high as 90% or more [13–16]. Approximately 68% of patients receiving chemotherapy develop CIPN within the first month of treatment [2]. Since there is no generally accepted effective method to prevent the development of CIPN or reverse nerve damage once it occurs, a better understanding of the mechanisms that cause CIPN is needed so that therapeutic approaches can be developed.

Cellular targets of chemotherapeutic drugs differ among classes of agents and include DNA damage, disruption of microtubules and axonal transport, altered ion channel activity, damage to myelin, immunological changes and neuroinflammation [17]. For example, platinum-based therapies cause damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA [18–20] whereas taxanes cause microtubule disruption [21]. A common consequence of chemotherapeutic agents [e.g, paclitaxel [22,23]; vincristine [24]; cisplatin [25] is the increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress. Indeed, most chemotherapeutics elevate intracellular levels of ROS in cancer cells, and their effectiveness for reducing tumor growth is associated with ROS-mediated injury and apoptosis [26]. However, somatosensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system are particularly sensitive to chemotherapeutics because dorsal root ganglia (DRG) lack a blood brain barrier to restrict access of the drugs and they have lower capacity to manage ROS [27]. Elevated ROS can lead to apoptosis in peripheral sensory neurons by activating a mitochondrial-associated apoptotic pathway that includes activation of caspase and dysregulation of calcium homeostasis [28,29].

2. ROS signaling

In aerobic metabolism, the incomplete, partial, or monovalent reduction of molecular oxygen gives rise to ROS that have one or more unpaired electrons making them free radicals and powerful oxidants. ROS can be formed non-enzymatically by chemical, photochemical and electron transfer reactions, or as the byproducts of endogenous enzymatic reactions, phagocytosis, and inflammation [30]. Generation of ROS occurs in subcellular compartments such as the mitochondria [31], the endoplasmic reticulum [32], the plasma membrane [33], peroxisomes [34], cytoplasm and lysosomes [35]. A number of cellular metabolic enzymes, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, xanthine oxidase, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), flavoproteins, CYP enzymes, oxidases, and myeloperoxidase are directly involved in the production of ROS [36]. Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) also generates ROS, in particular, •O2− and H2O2. ROS can be produced during oxidation of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes by membrane associated enzymes such as cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase [37].

The occurrence of ROS in biological systems was first described in 1954 [38]. In the same year, the toxic effects of oxidizing free radicals under conditions of high oxygen tension was demonstrated as well [39]. ROS regulate a variety of cellular responses that range from prosurvival pathways (antimicrobial and tumor inhibition) to “antisurvival” pathways [40]. Under normal physiological conditions, the intracellular level of ROS is maintained at a steady and low level by the equilibrium between their production and elimination by an endogenous antioxidant system. Endogenous antioxidants include low-molecular-weight antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid, vitamin E, and glutathione) and antioxidant enzymes (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and thioredoxins). In the central nervous system, ROS are generated downstream to activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate and play a role as intracellular messengers through the activation of protein kinases and other intracellular enzymes [41].

The abundance of ROS causes irreversible changes in proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids that lead to cell damage with subsequent effects on cell activity and survival [42]. The specific effects of ROS occur in part through the covalent modification of specific cysteine residues found within redox-sensitive target proteins resulting in the modification of enzymatic activity [43]. For example, through the oxidation of redox-sensitive cysteine residues ROS activates p38a MAPK, promoting neuroinflammation and subsequently neurotoxicity [44]. A causal relationship between oxidative stress and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) a nuclear receptor involved in limiting ROS, was also shown. Following cisplatin treatment PPARγ protein was reduced in DRG and was associated with oxidative stress [25]. Thus ROS lead to aberrant cell dysfunction and cell death, and thereby contribute to disease development. Oxidative stress is implicated in the initiation and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease [45], Parkinson’s disease [46], and multiple sclerosis [47]. An excess of ROS also contributes to peripheral neuropathy in diabetes [48], acrylamide toxicity [49], and Charcot-Marie syndrome [50,27], as well as the pathophysiology of somatic [51,52] and visceral pain [53]. ROS mediate their effects in part via activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), protein-1 (AP-1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 and STAT3 transcription factors leading to up-regulation of proinflammatory genes and cytokines that include TNF-α, interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, IL-8, and transcription of other inflammatory genes [54–59]. These changes, as well as increased expression of COX-2 [60] and iNOS [61] which are both regulated in part by NF-kB [62], are relevant to pain.

Oxidative stress and ROS are also associated with chronic pain and hyperalgesia. Oxidative stress pathways parallel those that contribute to pain associated with central sensitization, leading to increased responses of nociceptive spinal neurons to innocuous and noxious stimuli (i.e., secondary hyperalgesia) [63–67]. Reducing ROS decreased secondary hyperalgesia and central sensitization produced by capsaicin [68] as well as long term potentiation in the spinal cord [69]. In the periphery, ROS contribute to hyperalgesia following acute inflammation [70,71]. ROS may also play a direct role in activation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels that underlie transduction of sensory stimuli (TRPV1 [72]; TRPA1 [73]) or enhance their activity [74]. Increasing the activity of these channels in DRG neurons can alter the excitation of neurons and the propagation of nociceptive sensory signals. In an animal model of neuropathic pain, spinal (i.e., intrathecal) administration of ROS scavengers phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) and 5,5-dimethylpyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) was more efficacious than systemic or intracerebroventricular administration [75,76] in attenuating mechanical hyperalgesia. Following nerve injury, ROS in the spinal cord might contribute to pain by decreasing GABAergic transmission [77] or by increasing excitatory synaptic strength (e.g. mitochondrial superoxide) [78].

In patients and in preclinical models, neuropathic pain produced by chemotherapy was dependent on oxidative stress and accumulation of ROS in the periphery and/or the spinal cord depending on the chemotherapeutic agent [3,22,27,67]. In some cases the accumulation of ROS was due to decreased activity of antioxidant enzymes [22,25]. Recent studies indicate that ROS are pivotal in CIPN by decreasing axonal outgrowth and promoting abnormal impulse transmission, hyperexcitability, spontaneous or ectopic discharge, and pain [5,7,25,79,80]. For example, oxidative stress contributed to cisplatin-induced hyperalgesia and a corresponding decrease in the electrical threshold of Aδ and C fibers [80]. Systemic administration of the ROS scavenger PBN blocked the accumulation of ROS and attenuated cisplatin-induced hyperalgesia [25,80]. In addition to a likely systemic effect, experiments in vitro demonstrated that ROS generated by cisplatin sensitized small DRG neurons directly and co-incubation with PBN reversed the effect of cisplatin [25]. Paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy is also associated with an increase in mitochondrial ROS in DRG [22,81], and ROS scavengers decreased ROS in DRG and attenuated hyperalgesia. However, clinical studies combining nutraceuticals with antioxidant properties and chemotherapy have been disappointing. Use of vitamin E, acetyl-L-carnitine, glutamine, glutathione, vitamin B6, omega-3 fatty acids, magnesium, calcium, α-lipoic acid and n-acetyl cysteine as adjuvants to cancer treatments showed controversial results [82–87]. For example, dietary beta carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, increased the incidence and mortality of lung cancer [88], and vitamin E supplements increased the risk of prostate cancer in healthy men [89]. Moreover, the adjunct use of antioxidants also reduced the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in some forms of cancer [90]. Thus, there is no clinical evidence to recommend ROS scavengers for the treatment or prophylaxis of CIPN.

3. Neuroprotective role of PPARγ and its ligands

A promising approach to potentially reduce chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress and CIPN is to enhance endogenous antioxidant responses in healthy cells, including neurons. Mammalian cells have evolved a unique metabolic strategy to protect themselves against oxidative damage induced by ROS: two transcription factors, PPARγ and nuclear factor erythroid 2p45-related factor 2 (Nrf2), play key roles in defending cells against oxidative stress [91].

PPARγ belongs to the family of PPAR nuclear receptors that also includes PPARα and PPARβ/δ. They share a common structure consisting of a DNA binding domain at the N-terminus and a ligand binding domain at the C-terminus. Of the three PPAR subtypes, PPARγ is the most studied and is further subdivided into the three isoforms: PPARγ1, PPARγ2, and PPARγ3. Each specific isoform is tissue- and function-specific. Although PPARγ1 is widely expressed among tissues, PPARγ2 occurs exclusively in adipose tissue [92] and PPARγ3 is expressed in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [93]. PPARγ is expressed throughout the central nervous system, in neurons and glia, as well as in DRG [94], but under physiological conditions expression is higher in neurons than in glia [95]. PPAR heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) inducing a conformational change in the receptor that allows the PPAR:RXR complex to bind to a PPAR response element (PPRE) in the promoter region of a target gene. Co-activators are important in defining the pattern of genes activated by PPAR ligands. PGC-1α, a co-activator of PPARγ, contributes to the expression of genes involved in glucose, lipid and energy metabolism, and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis [96]. In the absence of a ligand, PPARγ:RXR can recruit a corepressor to the complex to suppress transcription of a gene. This keeps the basal levels of PPARγ-mediated transcription minimal [97]. In the presence of ligand, the corepressor dissociates and a coactivator binds to the PPAR:RXR complex to initiate mRNA synthesis.

PPAR signaling is directly related to PPAR expression, its interactions with ligands and post-translational modification. Different ligands bind to PPARγ in different ways, inducing different conformations and different transcription patterns [98,99]. For example, synthetic ligands not only compete for a hydrophobic binding pocket for PPARγ activation by endogenous ligands, but also bind to an alternative site that promotes PPARγ hyperactivation in vivo. Thus, allosteric regulation may explain the adverse effects of some synthetic ligands [100]. Genes controlled by PPARγ are differentially regulated not only by agonist binding but also by post-translational modifications that include phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and ubiquitination of PPARγ [98,101,102]. For example, phosphorylation by MAPK decreases PPARγ activity [103]. CDK5-mediated phosphorylation of PPARγ leads to reduced insulin sensitivity [98,99], and SUMOylation at Lys395 is strongly associated with PPARγ transrepression of nuclear factor NF-κB [102]. Thus blocking the activity of other transcription factors by this non-genomic mechanism may underlie some of the anti-inflammatory effects mediated by PPARγ [104].

3a. PPARγ ligands

Natural and synthetic PPARγ ligands have been identified and are of considerable scientific and clinical interest because PPARγ controls the expression of hundreds of genes. A number of putative natural ligands for PPARγ-dependent gene transcription have been identified on the basis of their ability to stimulate receptor activity, although their endogenous roles in vivo remain uncertain. PPARγ is activated by a range of endogenous bioactive lipids including polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), their lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase and nitrated metabolites as well as lysophosphatidic acid, albeit at very high and possibly supraphysiological concentrations. Free polyunsaturated fatty acids activate PPARs with relatively low affinity, whereas fatty-acid derivatives show higher affinity and selectivity [105,106]. 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), an oxidized fatty acid, was recognized as the first natural ligand of PPARγ [107,108]. Subsequently, two oxidized fatty acids [9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (9-HODE) and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE)] and two nitrated fatty acids [nitrated linoleic (LNO2) and oleic acids (OA-NO2)] were shown to activate PPARγ-dependent gene transcription with potency rivaling that of rosiglitazone [109–111]. Recently, resolvin E1 was determined to bind to the ligand binding domain of PPARγ with affinity comparable to rosiglitazone [106], a synthetic PPARγ agonist, suggesting its potential as an endogenous agonist. Using reporter gene assays, binding studies with selective antagonists in vitro and in vivo, and small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown, endocannabinoids such as anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) have been identified as additional promising PPARγ ligands [112,113]. For example, AEA initiates transcriptional activation of PPARγ by binding to the PPARγ ligand binding domain in a concentration-dependent manner in multiple cell types [114]. In addition to AEA, 2-AG and 15-Deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2-glycerol ester, a putative metabolite of 2-AG, were shown to suppress expression of IL-2 in a reporter gene assay through binding to PPARγ [115,116]. Therefore, the interaction between endocannabinoids and PPARγ may include direct binding of endocannabinoids or their hydrolyzed or/and oxidized metabolites to PPARγ. The possible modulation of PPARγ-dependent gene expression down stream of intracellular signaling cascades initiated by activation of cannabinoid receptors cannot be excluded.

It is interesting to note that there is a feed forward loop in bioactive lipid signaling and PPARγ. Due to their hydrophobic nature, endogenous PPAR ligands are delivered to the receptors by fatty-acid-binding proteins (FABPs) [97]. Since the PPARγ response element is located in the promoters of fabp genes [117], it is not surprising that treatment with a PPARγ ligand increases PPARγ-dependent expression of FABP4 in monocyte-derived dendritic cells [118], and a large number of fatty acids transported by FABP5 stimulate PPARγ-dependent gene expression [119].

Synthetic PPARγ agonists consist of several subgroups: the thiazolidinediones (TZD, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone and troglitazone), the non-TZD agonists (ciglitazone, netoglitazone and rivoglitazone, the PPARα/γ dual and PPARα/γ/δ pan-agonists as well as the selective PPARγ modulators, [120]. Unexpectedly, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (flufenamic acid, ibuprofen, fenoprofen, and indomethacin A) are also weak PPARγ ligands. The TZDs were the first family of synthetic PPARγ ligands [121] and are the standard for full PPARγ agonist activity. Currently, TZDs are used clinically to improve glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. Thus they have benefits for patients with diabetes [122] and cardiovascular disease [123,124].

3b. PPARγ and neuroprotection

PPARγ agonists mitigate neuroinflammation in two ways: 1) by direct inhibition of NF-kB and 2) by increasing expression of enzymes that decrease ROS. In multiple tissues, activation of PPARγ leads to upregulation of key antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase [125–127]. In contrast to its role in ligand activation of gene expression by binding of the nuclear receptor to PPRE, PPARγ blocks expression of genes promoted by other classes of transcription factors [128]. PPARγ agonists reduce inflammation by promoting inhibition of pro-inflammatory transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB, STAT1, STAT3, AP-1 and NFAT) thereby decreasing synthesis of mRNA of enzymes and mediators that promote the formation of ROS, including COX-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and proinflammatory cytokines [129]. The anti-oxidant activity of PPARγ in combination with its inhibition of NF-κB underlies the function of PPARγ in neuroprotection. Neuroprotective effects of PPARγ agonists have been reported in animal models of peripheral neuropathies including nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain, trigeminal neuropathic pain and diabetic neuropathy [130–132]. Ghosh and colleagues [133] reported that pioglitazone reduced mitochondrial ROS in a neuron-like cell line by up-regulating mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant defense enzymes. In animal models, TZDs attenuated inflammation-associated chronic and acute neurological disorders such as stroke, spinal cord injury, and traumatic brain injury [134]. In diabetic neuropathy, pioglitazone reduced proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and 1L-1B in the sciatic nerve, normalized expression of Nav1.7 channels that underlie neuronal excitability, and increased expression of the PPARγ gene in the spinal cord [132]. Similarly, pretreatment with pioglitazone protected cortical neurons from H2O2-mediated damage by the increasing the expression of PPARγ mRNA and protein and a downstream increase in catalase [135]. It is noteworthy that rosiglitazone also protected hippocampal and DRG neurons from experimentally induced mitochondrial damage by increasing the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [136]. Similarly, in auditory hair cells, pioglitazone blocked gentamicin toxicity by upregulating genes that decrease ROS and prevent apoptosis [137].

PPARγ does not act alone to reduce oxidative stress. PPARγ regulates Nrf2, a master redox-sensing transcription factor that binds the antioxidant response element (ARE) to activate antioxidant systems and mute the destructive effects of oxidative stress [91,138]. In addition to PPARγ-mediated modulation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway, Nrf2 also regulates PPARγ/PPRE, suggestive of a bidirectional loop [139]. Thus, there is a direct relationship between PPARγ and Nrf2: in the absence of Nrf2 PPARγ expression decreases, and vice versa. For example, PPARγ expression was markedly reduced in Nrf2 null mice compared to wild-type mice [139]. Furthermore, TZDs simultaneously upregulated expression of PPARγ and Nrf2 in animal models of oxidative stress [140]. Importantly, some antioxidant genes such as catalase, glutathione S-transferase and superoxide dismutase contain both a PPRE and an ARE and are regulated by both PPARγ and Nrf2 to elicit anti-oxidative effects. In addition, PPARγ and Nrf2 synergistically inhibited the NF-κB pathway to produce anti-inflammatory effects [142]. Thus, clinical benefits of TZDs in CIPN arise from their ability to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation. Similarly, the analgesic properties of PPAR agonists have been demonstrated in a variety of preclinical pain models [94].

Interestingly, PPARγ agonists play an important role in overcoming neuronal insulin resistance in conditions of dysfunctional carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, although the contribution of insulin receptors to neuroprotection in CIPN is not known. Neurons are not dependent on insulin for glucose uptake as muscle or adipose tissue, but they are insulin-responsive [143]. Neuronal insulin receptors couple to two cellular signaling pathways, Akt and MAPK, that promote neuron survival and axonal growth [144]. Insulin receptors are especially high at the perikaryon of small-diameter sensory DRG neurons, suggesting the involvement of insulin signaling in nociceptive pathways [145]. Increased ROS levels are an important trigger for insulin resistance [146,147], but there is only one report of insulin resistance in C-fibers of cisplatin treated guinea pigs [148]. Because the occurrence of insulin resistance in CIPN has not been adequately addressed, we cannot exclude the possibility that a neuroprotective role of PPARγ agonists in CIPN is mediated by improved insulin receptor sensitivity.

Another important benefit of PPARγ is its potential use in cancer therapy and prevention. Activation of PPARγ by TZDs is tumor suppressive in human breast, prostate, colon, bladder and lung cancer, as well as in osteosarcoma and leukemia [149–152]. Since NF-KB signaling and insulin resistance are associated with an increased risk of several cancers, including breast, rectal, liver, and pancreatic cancers, PPARγ ligands can suppress tumors while reducing NF-KB and insulin resistance, resulting in cancer cell reprogramming, differentiation and survival [151,153].

4. Conclusion

Although the pharmacological agonists of PPARγ exhibit promising therapeutic properties in treatment of painful CIPN due to their profound ability to attenuate oxidative stress and inhibit ROS-related downstream pathways, recent interest in these nuclear receptors has faded. Several clinical trials have shown that it is difficult to develop a PPARγ ligand without concomitantly inducing unacceptable side-effects. Two TZDs (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) are currently available in the United States but were suspended by the European Medicines Agency owing to concerns that the overall risks of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone exceed their benefits. Moreover, PPARγ ligands have been neuroprotective in animal models [154–156], but not in clinical settings [157,158]. In this regard, a thorough study of the role and potential benefits of endogenous PPARγ ligands may reveal new therapeutic and safe approaches for preventing CIPN with minimal risks. Tissue specific targeting also could pave the way to renewed interest and clinical use of PPAR ligands.

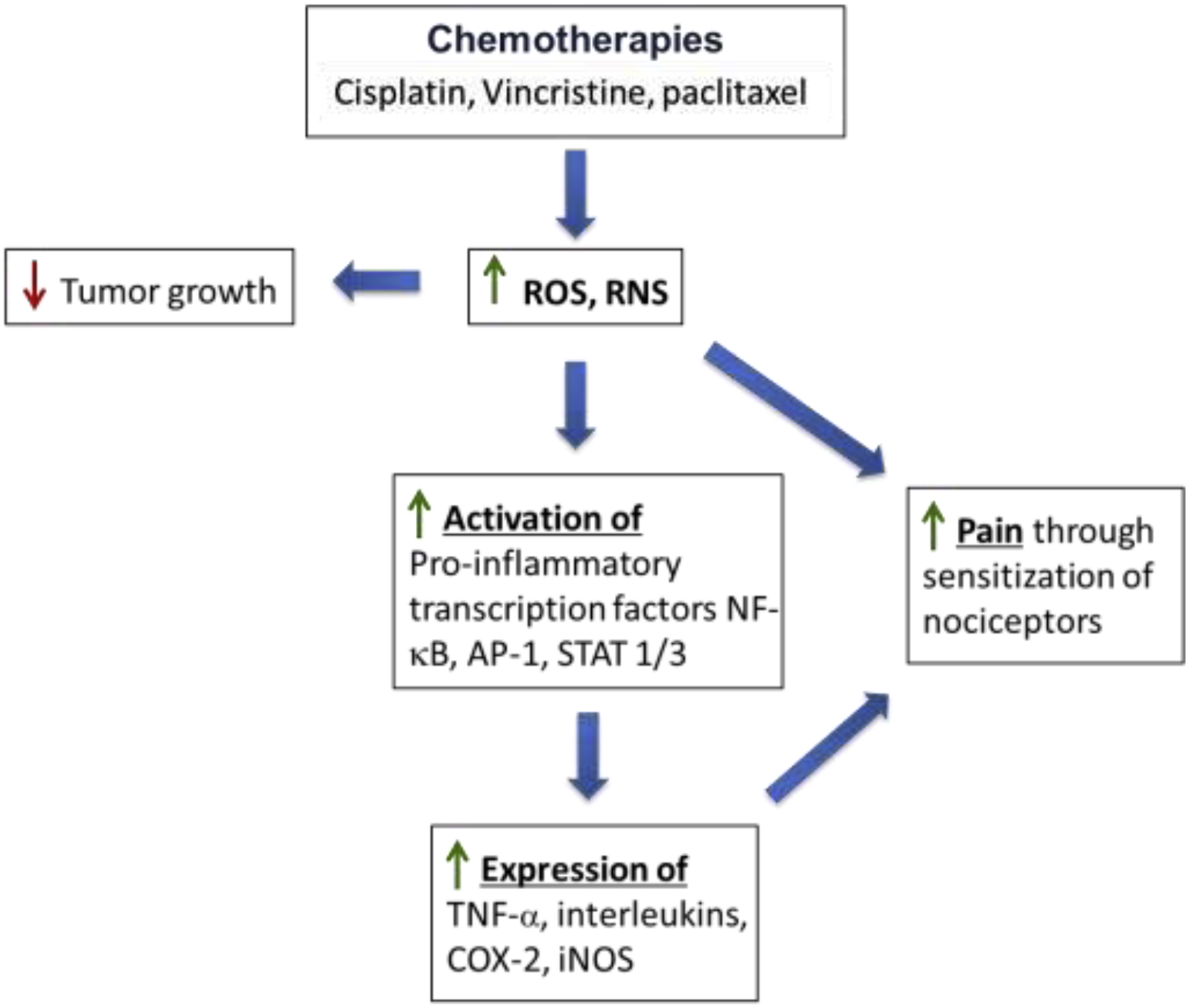

Figure 1.

Treatment with chemotherapeutic agents generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and promotes oxidative stress. Although this is an underlying mechanism for reducing tumor growth, ROS can sensitize nociceptors that mediate pain directly as well as indirectly through increased expression of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-α), interleukins and oxidized lipids (e.g., prostaglandins) generated by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). ROS activates pro-inflammatory transcription factors including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), protein-1 (AP-1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 and −3. See text for additional details.

Figure 2.

Pathways regulated by Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) reduce levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). PPARγ heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to activate the PPAR response element (PPRE) on target genes. Activation of gene transcription increases the expression of genes such as catalase and superoxide dismutase that catabolize ROS. PPARγ also mediates transrepression of pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), protein-1 (AP-1), and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 and −3. PPARγ-mediated gene repression reduces levels of enzymes that generate ROS: cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Endogenous agonists for PPARγ include15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), resolving E1 and endocannabinoids such as anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Synthetic agonists include pioglitazone, a thioglitazone. See text for additional details.

Highlights.

Peripheral neuropathy is a common side effect of many chemotherapeutic agents.

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) can be painful and long-lasting.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are contributing factors to CIPN.

Activating endogenous antioxidant pathways, particularly PPARγ, may prevent CIPN.

Funding sources

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA241627) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL135895).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest

None

References

- [1].Park SB, Goldstein D, Krishnan AV, S-Y Lin C, Friedlander ML, Cassidy J, Koltzenburg M, Kiernan MC, Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: a critical analysis, CA Cancer J Clin. 63 (2013) 419–437 doi: 10.3322/caac.21204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R, MacLeod MR, Colvin LA, Fallon M, Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Pain 155 (2014) 2461–2470 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Flatters SJL, Dougherty PM, Colvin LA, Clinical and preclinical perspectives on Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN): a narrative review, Br J Anaesth. 119 (2017) 737–749 doi: 10.1093/bja/aex229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Argyriou AA, Kyritsis AP, Makatsoris T, Kalofonos HP, Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in adults: a comprehensive update of the literature, Cancer Manag. Res 6 (2014)135–147 Published 2014 Mar 19. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S44261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Xiao WH, Bennett GJ, Chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain: Abnormal spontaneous discharge in A-fiber and C-fiber primary afferent neurons and its suppression by acetyl-L-carnitine, Pain 135 (2008) 262–270 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tanner KD, Reichling DB, Levine JD, Nociceptor hyper-responsiveness during vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat, J Neurosci. 18 (1998) 6480–6491 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06480.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Uhelski ML, Khasabova IA, Simone DA, Inhibition of anandamide hydrolysis attenuates nociceptor sensitization in a murine model of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, J Neurophysiol. 113 (2015) 1501–1510 doi: 10.1152/jn.00692.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marchettini P, Lacerenza M, Mauri E, Marangoni C, Painful peripheral neuropathies, Curr Neuropharmacol. 4 (2006) 175–181 doi: 10.2174/157015906778019536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, Freeman R, Truini A, Attal N, Finnerup NB, Eccleston C, Kalso E, Bennett DL, Dworkin RH, Raja SN, Neuropathic pain, Nat Rev Dis Primers. 3 (2017) 17002. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brown TJ, Sedhom R, Gupta A, Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy, JAMA Oncol. 5 (2019) 750 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miltenburg NC, Boogerd W, Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy: A comprehensive survey, Cancer Treat Rev. 40 (2014) 872–882 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kerckhove N, Collin A, Condé S, Chaleteix C, Pezet D, Balayssac D, Long-Term Effects, Pathophysiological Mechanisms, and Risk Factors of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathies: A Comprehensive Literature Review, Front Pharmacol. 8 (2017) 86 Published 2017 Feb 24 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Polomano RC, Bennett GJ, Chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy, Pain Med. 2 (2001) 8–14 doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2001.002001008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Armstrong T, Almadrones L, Gilbert MR, Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, Oncol Nurs Forum. 32 (2005) 305–311 doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.305-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hausheer FH, Schilsky RL, Bain S, Berghorn EJ, Lieberman F, Diagnosis, management, and evaluation of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, Semin Oncol. 33 (2006) 15–49 doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Miaskowski C, Mastick J, Paul SM, Topp K, Smoot B, Abrams G, Chen L-M, Kober KM, Conley YP, Chesney M, Bolla K, Mausisa G, Mazor M, Wong M, Schumacher M, Levine JD, Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathy in Cancer Survivors, J Pain Symptom Manage 54 (2017) 204–218.e2 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zajączkowska R, Kocot-Kępska M, Leppert W, Wrzosek A, Mika J, Wordliczek J, Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy,Int J Mol Sci. 20 (2019) 1451 Published 2019 Mar 22 doi: 10.3390/ijms20061451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jung Y, Lippard SJ, Direct cellular responses to platinum-induced DNA damage, Chem Rev. 107 (2007) 1387–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Podratz JL, Knight AM, Ta LE, Staff NP, Gass JM, Genelin K, Schlattau A, Lathroum L, Windebank AJ, Cisplatin induced mitochondrial DNA damage in dorsal root ganglion neurons, Neurobiol Dis. 41 (2011) 661–668 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wisnovsky SP, Wilson JJ, Radford RJ, Pereira MP, Chan MR, Laposa RR, Lippard SJ, Kelley SO, Targeting mitochondrial DNA with a platinum-based anticancer agent, Chem Biol. 20 (2013) 1323–1328 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jordan MA, Wilson L, Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs, Nat Rev Cancer. 4 (2004) 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Duggett NA, Griffiths LA, McKenna OE, de Santis V, Yongsanguanchai N, Mokori EB, Flatters SJL, Oxidative stress in the development, maintenance and resolution of paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy, Neuroscience 333 (2016) 13–26 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Duggett NA, Griffiths LA, Flatters SJL, Paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy is associated with changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics, glycolysis, and an energy deficit in dorsal root ganglia neurons, Pain 158 (2017) 1499–1508 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gong SS, Li YX, Zhang MT, Du J, Ma P-S, Yao W-X, Zhou R, Niu Y, Sun T, Yu J-Q, Neuroprotective Effect of Matrine in Mouse Model of Vincristine-Induced Neuropathic Pain, Neurochem Res. 41 (2016) 3147–3159 doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2040-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Khasabova IA, Khasabov SG, Olson JK, Uhelski ML, Kim AH, Albino-Ramírez AM, Wagner CL, Seybold VS, Simone DA, Pioglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, reduces cisplatin-evoked neuropathic pain by protecting against oxidative stress, Pain 160(2019) 688–701 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yang H, Villani RM, Wang H, Simpson MJ, Roberts MS, Tang M, Liang X, The role of cellular reactive oxygen species in cancer chemotherapy, J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 37 (2018) 266 doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0909-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Areti A, Yerra VG, Naidu V, Kumar A, Oxidative stress and nerve damage: role in chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy, Redox Biol. 2 (2014) 289–295 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Canta, Pozzi E, Carozzi VA, Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN), Toxics 3 (2015) 198–223 Published 2015 Jun 5 doi: 10.3390/toxics3020198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nita M, Grzybowski A, The Role of the Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of the Age-Related Ocular Diseases and Other Pathologies of the Anterior and Posterior Eye Segments in Adults, Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016. 3164734. doi: 10.1155/2016/3164734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Umeno A, Biju V, Yoshida Y, In vivo ROS production and use of oxidative stress-derived biomarkers to detect the onset of diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes, Free Radic Res. 51(2017) 413–427 doi: 10.1080/10715762.2017.1315114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Navarro A Boveris, The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process, Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 292 (2007) C670–C686 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cao SS, Kaufman RJ, Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cell fate decision and human disease, Antioxid Redox Signal. 21 (2014) 396–413 doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang Z, Blake DR, Stevens CR, Kanczler JM, Winyard PG, Symons MC, Benboubetra M, Harrison R, A reappraisal of xanthine dehydrogenase and oxidase in hypoxic reperfusion injury: the role of NADH as an electron donor, Free Radic Res. 28 (1998) 151–164 doi: 10.3109/10715769809065801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brown GC, Borutaite V, There is no evidence that mitochondria are the main source of reactive oxygen species in mammalian cells, Mitochondrion 12 (2012) 1–4 doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kurutas EB, The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: current state, Nutr J. 15 (2016) 71 doi: 10.1186/s12937-016-0186-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kvandová M, Majzúnová M, Dovinová I The role of PPARgamma in cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Res. 65 (2016) S343–S363 doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cho KJ, Seo JM, Kim JH Bioactive lipoxygenase metabolites stimulation of NADPH oxidases and reactive oxygen species, Mol Cells. 32(2011) 1–5 doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-1021-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Commoner, Townsend J, Pake GE, Free radicals in biological materials Nature 174 (1954) 689–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gerschman R, Gilbert DL, Nye SW, Dwyer P, Fenn WO, Oxygen poisoning and X-irradiation: a mechanism in common Science 119 (1954) 623–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dröge W, Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function, Physiol Rev. 82 (2002) 47–95 doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kishida KT, Klann E, Sources and targets of reactive oxygen species in synaptic plasticity and memory, Antioxid Redox Signal. 9 (2007) 233–244 doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.ft-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Munoz FM, Gao R, Tian Y, Henstenburg BA, Barrett JE, Hu H, Neuronal P2X7 receptor-induced reactive oxygen species production contributes to nociceptive behavior in mice, Sci Rep. 7 (2017) 3539 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03813-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Newsholme P, Cruzat VF, Keane KN, Carlessi R, de Bittencourt PI Jr, Molecular mechanisms of ROS production and oxidative stress in diabetes, Biochem J. 473 (2016) 4527–4550 doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160503C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bassi R, Burgoyne JR, DeNicola GF, Rudyk O, DeSantis V, Charles RL, Eaton P, Marber MS, Redox-dependent dimerization of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3, J Biol Chem. 292 (2017) 16161–16173 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.785410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang X, Wang W, Li L, Perry G, Lee HG, Zhu X, Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1842 (2014) 1240–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lu M, Su C, Qiao C, Bian Y, Ding J, Hu G, Metformin Prevents Dopaminergic Neuron Death in MPTP/P-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease via Autophagy and Mitochondrial ROS Clearance, Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 19 (2016) pyw047 doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Carlström KE, Ewing E, Granqvist M, Gyllenberg A, Aeinehband S, Enoksson SL, Checa A, Badam TVS, Huang J, Gomez-Cabrero D, Gustafsson M, Al Nimer F, Wheelock CE, Kockum I, Olsson T, Jagodic M, Piehl F, Therapeutic efficacy of dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis associates with ROS pathway in monocytes, Nat Commun. 10 (2019) 3081 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11139-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Figueroa-Romero, Sadidi M, Feldman EL, Mechanisms of disease: the oxidative stress theory of diabetic neuropathy, Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 9(2008) 301–314 doi: 10.1007/s11154-008-9104-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pennisi M, Malaguarnera G, Puglisi V, Vinciguerra L, Vacante M, Malaguarnera M, Neurotoxicity of acrylamide in exposed workers, Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(2013) 3843–3854 doi: 10.3390/ijerph10093843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chahbouni M, López MDS, Molina-Carballo A, de Haro T, Muñoz-Hoyos A, Fernández-Ortiz M, Guerra-Librero A, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Melatonin Treatment Reduces Oxidative Damage and Normalizes Plasma Pro-Inflammatory Cyts in Patients Suffering from Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathy: A Pilot Study in Three Children, Molecules 22 (2017) 1728 doi: 10.3390/molecules22101728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chung JM, The role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in persistent pain, Mol Interv. 4 (2004) 248–250 doi: 10.1124/mi.4.5.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Salvemini, Little JW, Doyle T, Neumann WL, Roles of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in pain, Free Radic Biol Med. 51 (2011) 951–966 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ji G, Li Z, Neugebauer V, Reactive oxygen species mediate visceral pain-related amygdala plasticity and behaviors, Pain 156 (2015) 825–836 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sun Y, Oberley LW, Redox regulation of transcriptional activators, Free Radic Biol Med. 21 (1996) 335–348 doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00109-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Janssen-Heininger YM, Poynter ME, Baeuerle PA, Recent advances towards understanding redox mechanisms in the activation of nuclear factor kappaB, Free Radic Biol Med. 28 (2000) 1317–1327 doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00218-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Flohé L, Brigelius-Flohé R, Saliou C, Traber MG, Packer L, Redox regulation of NF-kappa B activation, Free Radic Biol Med. 22 (1997) 1115–1126 doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00501-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schmidt KN, Amstad P, Cerutti P, Baeuerle PA, The roles of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide as messengers in the activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B, Chem Biol. 2 (1995) 13–22 doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90076-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Simon AR, Rai U, Fanburg BL, Cochran BH, Activation of the JAK-STAT pathway by reactive oxygen species, Am J Physiol. 275(1998) C1640–C1652 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang Y, Yu X, Song H, Feng D, Jiang Y, Wu S, Geng J, The STAT-ROS cycle extends IFN‑ induced cancer cell apoptosis, Int J Oncol. 52 (2018) 305–313 doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Li, Guo L, Ku T, Chen M, Li G, Sang N, PM2.5 exposure stimulates COX-2-mediated excitatory synaptic transmission via ROS-NF-κB pathway, Chemosphere 190 (2018) 124–134 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Park J, Min J-S, Kim B, Chae U-B, Yun JW, Choi M-S, Kong Il-K., Chang K-T, Lee D-S, Mitochondrial ROS govern the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory response in microglia cells by regulating MAPK and NF-κB pathways, Neurosci Lett. 584 (2015) 191–196 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ahn KS, Aggarwal BB, Transcription factor NF-kappaB: a sensor for smoke and stress signals, Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1056 (2005) 218–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].LaMotte RH, Shain CN, Simone DA, Tsai EP, Neurogenic hyperalgesia: Psychophysical studies of underlying mechanisms, Journal of Neurophysiology 66 (1991) 190–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Simone DA, Oh U, Sorkin LS, Chung JM, Owens C, LaMotte RH, Willis WD, Neurogenic hyperalgesia: Central neural correlates in responses of spinothalamic tract neurons, Journal of Neurophysiology 66 (1991) 228–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ, Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity, J Pain 10 (2009) 895–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain, Cell 139 (2009) 267–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shim HS, Bae C, Wang J, Lee K-H, Hankerd KM, Kim HK, Chung JM, La J-H, Peripheral and central oxidative stress in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain, Mol Pain 15 (2019) 1744806919840098 doi: 10.1177/1744806919840098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee, Kim HK, Kim JH, Chung K, Chung JM, The role of reactive oxygen species in capsaicin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and in the activities of dorsal horn neurons, Pain 133 (2007) 9–17 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lee KY, Chung K, Chung JM, Involvement of reactive oxygen species in long-term potentiation in the spinal cord dorsal horn, J Neurophysiol. 103 (2010) 382–391 doi: 10.1152/jn.90906.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Twining CM, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Chacur M, Martin D, Poole S, Marsh H, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Peri-sciatic proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and complement induce mirror-image neuropathic pain in rats, Pain 110 (2004) 299–309 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wang Z-Q, Porreca F, Cuzzocrea S, Galen K, Lightfoot R, Masini E, Muscoli C, Mollace V, Ndengele M, Ischiropoulos H, Salvemini D, A newly identified role for superoxide in inflammatory pain, J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 309 (2004) 869–878 doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Keeble JE, Bodkin JV, Liang L, Wodarski R, Davies M, Fernandes ES, de F. Coelho C, Russell F, Graepel R, Muscara MN, Malcangio M, Brain SD, Hydrogen peroxide is a novel mediator of inflammatory hyperalgesia, acting via transient receptor potential vanilloid 1-dependent and independent mechanisms, Pain 141 (2009) 135–142 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Dalenogare DP, Theisen MC, Peres DS, Fialho MFP, Lückemeyer DD, de D. Antoniazzi CT, Kudsi SQ, de A. Ferreira M, Ritter CDS, Ferreira J, Oliveira SM, Trevisan G, TRPA1 activation mediates nociception behaviors in a mouse model of relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, Exp Neurol. 328 (2020) 113241 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Kozai, Kabasawa Y, Ebert M, Kiyonaka S, Y. Otani Firman, Numata T, Takahashi N, Mori Y, Ohwada T, Transnitrosylation directs TRPA1 selectivity in N-nitrosamine activators, Mol Pharmacol. 85 (2014) 175–185 doi: 10.1124/mol.113.088864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kim HK, Park SK, Zhou J-L, Taglialatela G, Chung K, Coggeshall RE, Chung JM, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an important role in a rat model of neuropathic pain, Pain 111 (2004) 116–124 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Schwartz ES, Kim HY, Wang J, Lee I, Klann E, Chung JM, Chung K, Persistent pain is dependent on spinal mitochondrial antioxidant levels, J Neurosci. 29 (2009) 159–168 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3792-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Yowtak J, Lee KY, Kim HY, Wang J, Kim HK, Chung K, Chung JM, Reactive oxygen species contribute to neuropathic pain by reducing spinal GABA release, Pain 152 (2011) 844–852 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Bae, Wang J, Shim HS, Tang SJ, Chung JM, La JH, Mitochondrial superoxide increases excitatory synaptic strength in spinal dorsal horn neurons of neuropathic mice, Mol Pain 14 (2018) 1744806918797032 doi: 10.1177/1744806918797032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Dougherty PM, Cata JP, Burton AW, Vu K, Weng HR, Dysfunction in multiple primary afferent fiber subtypes revealed by quantitative sensory testing in patients with chronic vincristine-induced pain, J Pain Symptom Manage 33 (2007) 166–179 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Khasabova IA, Khasabov S, Paz J, Harding-Rose C, Simone DA, Seybold VS, Cannabinoid type-1 receptor reduces pain and neurotoxicity produced by chemotherapy, J Neurosci. 32 (2012) 7091–7101 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0403-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kim HK, Hwang SH, Abdi S, Tempol Ameliorates and Prevents Mechanical Hyperalgesia in a Rat Model of Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain, Front Pharmacol. 7 (2016) 532 Published 2017 Jan 16 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Maestri A, De Pasquale Ceratti A, Cundari S, Zanna C, Cortesi E, Crinò L, A pilot study on the effect of acetyl-L-carnitine in paclitaxel- and cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy, Tumori. 91 (2005) 135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Schloss JM, Colosimo M, Airey C, Masci PP, Linnane AW, Vitetta L, Nutraceuticals and chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a systematic review [published correction appears in Clin Nutr. 2015 Feb;34(1):167] Clin Nutr. 32(2013) 888–893 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Sisignano M, Baron R, Scholich K, Geisslinger G, Mechanism-based treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain, Nat Rev Neurol. 10 (2014) 694–707 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Callander N, Markovina S, Eickhoff J, Hutson P, Campbell T, Hematti P, Go R, Hegeman R, Longo W, Williams E, Asimakopoulos F, Miyamoto S, Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALCAR) for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with bortezomib, doxorubicin and low-dose dexamethasone: a study from the Wisconsin Oncology Network, Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 74 (2014) 875–882 doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2550-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Hershman DL, Unger JM, Crew KD, Minasian LM, Awad D, Moinpour CM, Hansen L, Lew DL, Greenlee H, Fehrenbacher L, Wade JL 3rd, Wong S-F, Hortobagyi GN, Meyskens FL, Albain KS, Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of acetyl-L-carnitine for the prevention of taxane-induced neuropathy in women undergoing adjuvant breast cancer therapy, J Clin Oncol. 31 (2013) 2627–2633 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Guo Y, Jones D, Palmer JL, Forman A, Dakhil SR, Velasco MR, Weiss M, Gilman P, Mills GM, Noga SJ, Eng C, Overman MJ, Fisch MJ, Oral alpha-lipoic acid to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Support Care Cancer 22 (2014) 1223–1231 doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2075-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cockfield JA, Schafer ZT, Antioxidant Defenses: A Context-Specific Vulnerability of Cancer Cells, Cancers (Basel) 11 (2019) 1208 Published 2019 Aug 20 doi: 10.3390/cancers11081208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, Minasian LM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Gaziano JM, Karp DD, Lieber MM, Walther PJ, Klotz L, Parsons JK, Chin JL, Darke AK, Lippman SM, Goodman GE, Meyskens FL Jr, Baker LH, Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT), JAMA 306 (2011) 1549–1556 doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Mut-Salud N, Álvarez PJ, Garrido JM, Carrasco E, Aránega A, Rodríguez-Serrano F, Antioxidant intake and antitumor ther-apy: toward nutritional recommendations for optimal results, Oxid Med CellLongev. 2016. 6719534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Polvani S, Tarocchi M, Galli A, PPARγ and Oxidative Stress: Con(β) Catenating NRF2 and FOXO, PPAR Res. 2012. 641087 doi: 10.1155/2012/641087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Li, Zhang F, Zhang X, Xue C, Namwanje M, Fan L, Reilly MP, Hu F, Qiang L, Distinct functions of PPARγ isoforms in regulating adipocyte plasticity,. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 481 (2016) 132–138 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Guo B, Huang X, Lee MR, Lee SA, Broxmeyer HE, Antagonism of PPAR-γ signaling expands human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by enhancing glycolysis, Nat Med. 24 (2018) 360–367 doi: 10.1038/nm.4477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Okine BN, Gaspar JC, Finn DP, PPARs and pain, Br J Pharmacol. 176(2019) 1421–1442 doi: 10.1111/bph.14339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Warden A, Truitt J, Merriman M, Ponomareva O, Jameson K, Ferguson LB, Mayfield RD, Harris RA, Localization of PPAR isotypes in the adult mouse and human brain, Sci Rep. 6 (2016) 27618 Published 2016 Jun 10 doi: 10.1038/srep27618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Rius-Pérez S, Torres-Cuevas I, Millán I, Ortega ÁL, Pérez S, PGC-1α, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress: An Integrative View in Metabolism, Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020. 1452696 Published 2020 Mar 9 doi: 10.1155/2020/1452696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Michalik L, Desvergne B, Wahli W, Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors and cancers: complex stories, Nat Rev Cancer 4 (2004) 61–70 doi: 10.1038/nrc1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL, Kajimura S, Boström P, Laznik D, Ruas JL, Chalmers MJ, Kamenecka TM, Blüher M, Griffin PR, Spiegelman BM, Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5, Nature 466 (2010) 451–456 doi: 10.1038/nature09291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Choi JH, Banks AS, Kamenecka TM, Busby SA, Chalmers MJ, Kumar N, Kuruvilla DS, Shin Y, He Y, Bruning JB, Marciano DP, Cameron MD, Laznik D, Jurczak MJ, Schürer SC, Vidović D, Shulman GI, Spiegelman BM, Griffin PR, Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARγ ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation, Nature 477 (2011) 477–481 doi: 10.1038/nature10383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Hughes TS, Giri PK, de Vera IMS, Marciano DP, Kuruvilla DS, Shin Y, Blayo A-L, Kamenecka TM, Burris TP, Griffin PR, Kojetin DJ, An alternate binding site for PPARγ ligands, Nat Commun. 5 (2014) 3571 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Banks AS, McAllister FE, Camporez JPG, Zushin P-JH, Jurczak MJ, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Shulman GI, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, An ERK/Cdk5 axis controls the diabetogenic actions of PPARγ, Nature 517 (2015) 391–395 doi: 10.1038/nature13887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Cai W, Yang T, Liu H, Han L, Zhang K, Hu X, Zhang X, Yin K-J, Gao Y, Bennett MVL, Leak RK, Chen J, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ): A master gatekeeper in CNS injury and repair, Progress in Neurobiology 163–164 (2018) 27–58 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Burns KA, Vanden Heuvel JP, Modulation of PPAR activity via phosphorylation, Biochim Biophys Acta 1771 (2007) 952–960 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Quintão NLM, Santin JR, Stoeberl LC, Corrêa TP, Melato J, Costa R, Pharmacological Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain: PPARγ Agonists as a Promising Tool, Front Neurosci. 13 (2019) 907 Published 2019 Aug 28. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Davies SS, Pontsler AV, Marathe GK, Harrison KA, Murphy RC, Hinshaw JC, Prestwich GD, Hilaire AS, Prescott SM, A Zimmerman G, McIntyre TM, Oxidized alkyl phospholipids are specific, high affinity peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands and agonists, J Biol Chem. 276 (2001) 16015–16023 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100878200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Muralikumar S, Vetrivel U, Narayanasamy A, Das NU, Probing the intermolecular interactions of PPARγ-LBD with polyunsaturated fatty acids and their anti-inflammatory metabolites to infer most potential binding moieties, Lipids Health Dis. 16 (2017) 17 doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0404-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM, 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma, Cell 83 (1995) 803–812 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, Patel I, Morris DC, Lehmann JM, A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and promotes adipocyte differentiation, Cell 83 (1995) 813–819 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM, Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma, Cell 93 (1998) 229–240 doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PRS, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, Chen K, Chen YE, Freeman BA, Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (2005) 2340–2345 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Baker PRS, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LMS, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, Freeman BA, Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands, J Biol Chem. 280 (2005) 42464–42475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].O’Sullivan SE, Cannabinoids go nuclear: evidence for activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, Br J Pharmacol. 152 (2007) 576–582 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].O’Sullivan SE, An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids,. Br J Pharmacol. 173 (2016) 1899–1910 doi: 10.1111/bph.13497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Bouaboula M, Hilairet S, Marchand J, Fajas L, Le Fur G, Casellas P, Anandamide induced PPARgamma transcriptional activation and 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation, Eur J Pharmacol. 517 (2005) 174–181 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Rockwell CE, Snider NT, Thompson JT, Vanden Heuvel JP, Kaminski NE Interleukin-2 suppression by 2-arachidonyl glycerol is mediated through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma independently of cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2, Mol Pharmacol. 70 (2006) 101–111 doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Raman P, Kaplan BL, Thompson JT, Vanden Heuvel JP, Kaminski NE, 15-Deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2-glycerol ester, a putative metabolite of 2-arachidonyl glycerol, activates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma, Mol Pharmacol. 80 (2011) 201–209 doi: 10.1124/mol.110.070441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Laprairie RB, Denovan-Wright EM, Wright JM, Subfunctionalization of peroxisome proliferator response elements accounts for retention of duplicated fabp1 genes in zebrafish, BMC Evol Biol. 147 (2016) 10.1186/s12862-016-0717-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Szatmari, Töröcsik D, Agostini M, Nagy T, Gurnell M, Barta E, Chatterjee K, Nagy L, PPARgamma regulates the function of human dendritic cells primarily by altering lipid metabolism, Blood 110 (2007) 3271–3280 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Bao Z, Malki MI, Forootan SS, Adamson J, Forootan FS, Chen D, Foster CS, Rudland PS, Ke Y, A novel cutaneous Fatty Acid-binding protein-related signaling pathway leading to malignant progression in prostate cancer cells, Genes Cancer 4 (2013) 297–314 doi: 10.1177/1947601913499155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Corona JC, Duchen MR, PPARγ as a therapeutic target to rescue mitochondrial function in neurological disease, Free Radic Biol Med. 100 (2016) 153–163 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma), J Biol Chem. 270 (1995) 12953–12956 doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Verma NK, Singh J, Dey CS, PPAR-gamma expression modulates insulin sensitivity in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells, Br J Pharmacol. 143 (2004) 1006–1013 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Parulkar AA, Pendergrass ML, Granda-Ayala R, Lee TR, Fonseca VA, Nonhypoglycemic effects of thiazolidinediones, Ann Intern Med. 135 (2001) 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Haffner SM, Greenberg AS, Weston WM, Chen H, Williams K, Freed MI, Effect of rosiglitazone treatment on nontraditional markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Circulation 106 (2002) 679–684 doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025403.20953.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Girnun GD, Domann FE, Moore SA, Robbins ME, Identification of a functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response element in the rat catalase promoter, Mol Endocrinol. 16 (2002) 2793–2801 doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Yu X, Shao X-G, Sun H, Li Y-N, Yang J, Deng Y-C, Huang Y-G, Activation of cerebral peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma exerts neuroprotection by inhibiting oxidative stress following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus, Brain Res. 1200 (2008) 146–158 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Chung SS, Kim M, Youn B-S, Lee NS, Park JW, Lee IK, Lee YS, Kim JB, Cho YM, Lee HK, Park KS, Glutathione peroxidase 3 mediates the antioxidant effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in human skeletal muscle cells, Mol Cell Biol. 29 (2009) 20–30 doi: 10.1128/MCB.00544-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Straus DS, Glass CK, Anti-inflammatory actions of PPAR ligands: new insights on cellular and molecular mechanisms, Trends Immunol. 28 (2007) 551–558 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Villapol S, Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma on brain and peripheral inflammation, Cell Mol. Neurobiol 38 (2018) 121–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Churi SB, Abdel-Aleem OS, Tumber KK, Scuderi-Porter H, Taylor BK, Intrathecal rosiglitazone acts at peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma to rapidly inhibit neuropathic pain in rats, J. Pain 9 (2008) 639–649 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Lyons DN, Zhang L, Danaher RJ, Miller CS, Westlund KN, PPARγ agonists attenuate trigeminal neuropathic pain, Clin. J. Pain 33 (2017) 1071–1080 doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Elkholy SE, Elaidy SM, El-Sherbeeny NA, Toraih EA, El-Gawly HW, Neuroprotective effects of ranolazine versus pioglitazone in experimental diabetic neuropathy: Targeting Nav1.7 channels and PPAR-γ, Life Sci. 250 (2020) 117557 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Ghosh S, Patel N, Rahn D, McAllister J, Sadeghi S, Horwitz G, Berry D, Wang KX, Swerdlow RH, The thiazolidinedione pioglitazone alters mitochondrial function in human neuron-like cells, Mol. Pharmacol 71 (2007) 1695–1702 doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Kapadia R, Yi JH, Vemuganti R, Mechanisms of anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of PPAR-gamma agonists, Front. Biosci 13 (2008) 1813–1826. Published 2008 Jan 1 doi: 10.2741/280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Gray, Ginty M, Kemp K, Scolding N, Wilkins A, The PPAR-gamma agonist pioglitazone protects cortical neurons from inflammatory mediators via improvement in peroxisomal function, J. Neuroinflammation 9 (2012) 10.1186/1742-2094-9-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Fuenzalida K, Quintanilla R, Ramos P, Piderit D, Fuentealba RA, Martinez G, Inestrosa NC, Bronfman M, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma up-regulates the Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic protein in neurons and induces mitochondrial stabilization and protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis, J. Biol. Chem 282 (2007) 37006–37015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700447200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Sekulic-Jablanovic M, Petkovic V, Wright MB, Kucharava K, Huerzeler N, Levano S, Brand Y, Leitmeyer K, Glutz A, Bausch A, Bodmer D, Effects of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR)-γ and -α agonists on cochlear protection from oxidative stress, PLoS One 12 (2017) e0188596. Published 2017 Nov 28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Lee C, Collaborative power of Nrf2 and PPARγ activators against metabolic and drug-induced oxidative injury, Oxid. Med. Cell Longev 2017 (2017) 1378175 doi: 10.1155/2017/1378175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Cho HY, Gladwell W, Wang X, Chorley B, Bell D, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR, Nrf2-regulated PPAR{gamma} expression is critical to protection against acute lung injury in mice, Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 182 (2010) 170–182 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1047OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Wang Y, Zhao W, Li G, Chen J, Guan X, Chen X, Guan Z, Neuroprotective effect and mechanism of thiazolidinedione on dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in vitro in Parkinson’s Disease, PPAR Res. 2017 (2017) 4089214 doi: 10.1155/2017/4089214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Xu L, Obaid U, Haixing L, Ali I, Li Z, Fang NZ, Pioglitazone mediated reduction in oxidative stress and alteration in level of PPARγ, NRF2 and antioxidant enzyme genes in mouse preimplantation embryo during maternal to zygotic transition, Pakistan J. Zool 51 (2019) 1085–1092. [Google Scholar]

- [142].Wardyn JD, Ponsford AH, Sanderson CM, Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways, Biochem. Soc. Trans 43 (2015) 621–626 doi: 10.1042/BST20150014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Kim B, Feldman EL, Insulin resistance in the nervous system, Trends Endocrinol. Metab 3 (2012) 133–141 doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Grote CW, Wright DE, A role for insulin in diabetic neuropathy, Front. Neurosci 10 (2016) 581. Published 2016 Dec 23 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Toth C, Brussee V, Martinez JA, McDonald D, Cunningham FA, Zochodne DW, Rescue and regeneration of injured peripheral nerve axons by intrathecal insulin, Neuroscience 139 (2006) 429–449 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES, Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance, Nature 7086 (2006) 944–948 doi: 10.1038/nature04634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Li J, Sipple J, Maynard S, Mehta PA, Rose SR, Davies SM, Pang Q, Fanconi anemia links reactive oxygen species to insulin resistance and obesity, Antioxid. Redox Signal 17 (2012) 1083–1098 doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Szilvássy J, Sziklai I, Sári R, Németh J, Peitl B, Porszasz R, Lonovics J, Szilvássy Z, Neurogenic insulin resistance in guinea-pigs with cisplatin-induced neuropathy, Eur. J. Pharmacol 531 (2006) 217–225 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Wang T, Xu J, Yu X, Yang R, Han ZC, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in malignant diseases, Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol 58 (2006) 1–14 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].He BC, Chen L, Zuo GW, Zhang W, Bi Y, Huang J, Wang Y, Jiang W, Luo Q, Shi Q, Zhang BQ, Liu B, Lei X, Luo J, Luo X, Wagner ER, Kim SH, He CJ, Hu Y, Shen J, Zhou Q, Rastegar F, Deng ZL, Luu HH, He TC, Haydon RC, Synergistic antitumor effect of the activated PPARgamma and retinoid receptors on human osteosarcoma, Clin. Cancer Res 16 (2010) 2235–2245 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Vella V, Nicolosi ML, Giuliano S, Bellomo M, Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R, PPAR-γ agonists as antineoplastic agents in cancers with dysregulated IGF axis, Front. Endocrinol 8 (2017) 31 Published 2017 Feb 22. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Lv S, Wang W, Wang H, Zhu Y, Lei C, PPARγ activation serves as therapeutic strategy against bladder cancer via inhibiting PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, BMC Cancer 19 (2019) 204 doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5426-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Lu Y, Sun Y, Zhu J, Yu L, Jiang X, Zhang J, Dong X, Ma B, Zhang Q, Oridonin exerts anticancer effect on osteosarcoma by activating PPAR-γ and inhibiting Nrf2 pathway, Cell Death Dis. 9 (2018) 15 doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0031-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Carta AR, PPAR-γ: therapeutic prospects in Parkinson’s disease, Curr. Drug. Targets 14 (2013) 743–751 doi: 10.2174/1389450111314070004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Randy LH, Guoying B, Agonism of Peroxisome Proliferator Receptor-Gamma may have Therapeutic Potential for Neuroinflammation and Parkinson’s Disease, Curr. Neuropharmacol 5 (2007) 35–46 doi: 10.2174/157015907780077123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Schintu N, Frau L, Ibba M, Caboni P, Garau A, Carboni E, Carta AR, PPAR-gamma-mediated neuroprotection in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease, Eur. J. Neurosci 29 (2009) 954–963 doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].NINDS Exploratory Trials in Parkinson Disease (NET-PD) FS-ZONE Investigators, Pioglitazone in early Parkinson’s disease: a phase 2, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trial [published correction appears in Lancet Neurol. 2015 Oct; 14(10):979]. Lancet Neurol. 14 (2015) 795–803 doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00144-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Brundin P, Wyse R, Parkinson disease: Laying the foundations for disease-modifying therapies in PD, Nat. Rev. Neurol 11 (2015) 553–555 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]