Abstract

Small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) are key players in bacterial regulatory networks. Monitoring their expression inside living colonized or infected organisms is essential for identifying sRNA functions, but few studies have looked at sRNA expression during host infection with bacterial pathogens. Insufficient in vivo studies monitoring sRNA expression attest to the difficulties in collecting such data, we therefore developed a non-mammalian infection model using larval Galleria mellonella to analyze the roles of Staphylococcus aureus sRNAs during larval infection and to quickly determine possible sRNA involvement in staphylococcal virulence before proceeding to more complicated animal testing. We began by using the model to test infected larvae for immunohistochemical evidence of infection as well as host inflammatory responses over time. To monitor sRNA expression during infection, total RNAs were extracted from the larvae and invading bacteria at different time points. The expression profiles of the tested sRNAs were distinct and they fluctuated over time, with expression of both sprD and sprC increased during infection and associated with mortality, while rnaIII expression remained barely detectable over time. A strong correlation was observed between sprD expression and the mortality. To confirm these results, we used sRNA-knockout mutants to investigate sRNA involvement in Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis, finding that the decrease in death rates is delayed when either sprD or sprC was lacking. These results demonstrate the relevance of this G. mellonella model for investigating the role of sRNAs as transcriptional regulators involved in staphylococcal virulence. This insect model provides a fast and easy method for monitoring sRNA (and mRNA) participation in S. aureus pathogenesis, and can also be used for other human bacterial pathogens.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, sRNA, Galleria mellonella, virulence, regulation

Introduction

The Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus bacterium is a major human and animal pathogen associated with mortality and morbidity worldwide. In humans, S. aureus is responsible for both community-acquired and healthcare-related infections ranging from superficial to very serious or fatal diseases, including osteomyelitis, bacteremia, and endocarditis (Tong et al., 2015). S. aureus is also a mucosal and skin mucous commensal bacterium, colonizing about 30% of healthy individuals (van Belkum et al., 2009). The nose is the main ecological niche, and nasal carriage is a key determinant for colonization at other sites (Wertheim et al., 2005), with asymptomatic nasal carriage a major risk factor for subsequent infection (von Eiff et al., 2001).

As both a commensal and a pathogen, S. aureus possesses a large number of factors involved in immunomodulation and/or virulence, including adhesins, toxins, and immunomodulatory proteins that it expresses only when necessary and in a coordinated manner. The bacteria quickly adapt to various environments that change due to stresses from host immune systems or nutrient deprivation, therefore S. aureus survives and grows through selective modulation of its metabolism and fitness. This implies a reprogramming of its intricate network of gene regulation, triggering the expression of genes that are essential for survival in the immediate environment, and extinguishing unnecessary ones. In addition to sRNAs, two-component systems (TCS) and DNA-binding proteins regulate metabolism and virulence factor expression (Jenul and Horswill, 2018), and the agr quorum-sensing system is the most significant TCS in S. aureus (Novick, 2003). RNAIII is the effector of this agr system (Bronesky et al., 2016) and was also one of the first sRNAs reported in S. aureus (Novick et al., 1993). RNAIII is a multifunctional RNA that codes for δ-hemolysin, and it directly regulates the expression of at least 12 mRNA targets (Raina et al., 2018).

In the SRD Staphylococcal regulatory RNAs database, Sassi et al. listed all sRNAs identified as being expressed by various strains of S. aureus and other Staphylococcaceae (Sassi et al., 2015). The S. aureus sRNA targets have only been identified for a few sRNAs, mostly by MS2 tagging (Lalaouna and Massé, 2015). Among these, at least seven are involved in virulence regulation: RNAIII (Srn_3910), SprC (Srn_3610), SprD (Srn_3800), SprX (Srn_3820), RsaA (Srn_1510), Teg49 (Srn_1550), and SSR42 (Srn_4470) (Novick, 2003; Chabelskaya et al., 2010; Morrison et al., 2012; Romilly et al., 2014; Le Pabic et al., 2015; Kathirvel et al., 2016; Manna et al., 2018). Most of these pioneering studies have compared sRNA-deleted and isogenic strains with respect to animal mortality, bacterial load in infected organs, or biofilm formation. Only a few studies have monitored in situ expression of sRNAs (Song et al., 2012; Szafranska et al., 2014), which differ from the levels encountered in growth media. Recent publications on S. aureus transcriptional adaptation in vitro and during infection or colonization (Chaffin et al., 2012; Szafranska et al., 2014; Jenkins et al., 2015; Chaves-Moreno et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2019; Ibberson and Whiteley, 2019) have highlighted major differences between in vitro and in vivo transcriptional gene regulation. This suggests that in situ exploration of the regulatory networks involving sRNAs in human pathogens is essential for understanding their roles.

The purpose of this study was to gain further insights into S. aureus sRNA functions during infection by assessing their expression levels in situ in infected organisms. To do this, we used a non-mammalian Galleria mellonella model to investigate riboregulations at the transcriptomic level. We provide evidence that the sRNA expression patterns in infected animals differs sharply from the levels in vitro, with a progressive accumulation of the sRNAs SprC and SprD in the larvae up to 4 days after infection. Moreover, SprC and SprD probably act as virulence factors during larval infection, since their presence and expression lead to fewer survivors. This G. mellonella infection model is thus shown to be a reliable tool for investigating the riboregulations involved in bacterial virulence.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Media, and Genetics

All strains used are listed in Supplementary Table 1 . For the development of the G. mellonella infection model, we used the S. aureus S75 strain obtained from a bacteremia patient. This strain is a multilocus sequence type 8 (ST8) and has a t190 spa type. The S75 genome was sequenced and deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GeneBank (accession number PRJNA273632). It has 2,728,924 base pairs, and is close to the NCTC 8325 reference strain, with 2,327 orthologous genes in common. For knock-out experiments, we used strains HG003-∆sprC, HG001-ΔsprX, HG001-∆sprD, and HG003-ΔrnaIII. These were constructed in our lab in HG001 and HG003 backgrounds, and both are derivatives of NCTC 8325 (Herbert et al., 2010). For rnaIII overexpression, we used a QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Quiagen) on the S. aureus Newman strain to extract the vector and transfer it to HG003 to create pRMC3-rnaIII. All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) at 150 rpm at 37°C, and in the presence of 10 µg/ml chloramphenicol for HG003-pRMC3-rnaIII. For larval infection, overnight cultures were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes then washed twice with sterile PBS. The inocula were prepared in sterile PBS by OD adjustment, verified by plating on tryptic soy agar after serial dilutions, then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C.

Galleria mellonella Infection Model

The G. mellonella larvae were purchased from Sud-Est Appats (Queige, France). They were stored in the dark at 4°C, and used within 7 days of delivery. To standardize the experiments, we selected larvae weighting about 250-300 mg and without color alteration. They were incubated at room temperature for 2 hours before injection, then disinfected externally with 70% ethanol. The infection was carried out using a KDS 100 automated syringe pump (KD Scientific) and a 300 µl Hamilton syringe. Haemocoel was injected with 10 μl of the S75 strain at 106, 107, 108, or 109 CFU/ml. The infected larvae were placed on Petri dishes and incubated at 37°C. Mortality was monitored daily for 6 days, and larvae were considered dead when they were immobile, no longer responding to stimuli, and melanized. For each condition, 3 independent experiments were performed using 10 infected larvae. The controls were uninjected larvae and larvae injected with 10 µl of sterile PBS. For the experiments using sRNA-deleted isogenic strains, either HG003 or HG001 was used as the control. For rnaIII overexpression experiments, pRMC3-rnaIII stability was assessed by randomly plating selected colonies grown from fat-body homogenates on agar containing 10 µg/ml of chloramphenicol at different time points after infection.

Bacterial Growth in the Larvae

One hundred larvae were infected with 106 CFU S. aureus S75. At different times post-infection, 3 living larvae were randomly selected, disinfected with 70% ethanol, dried, and ice-chilled for 10 minutes. The hemolymph and fat bodies were separated from each larva and pooled. Briefly, after an incision with a scalpel, the larvae were squeezed to collect hemolymph, and pooled into a microcentrifuge tube collection. On average, 15 to 40 µl of hemolymph per larva were collected. The remaining fat bodies were mechanically homogenized with sterile distilled water at 4°C. These collections were diluted with sterile distilled water, plated on Baird-Parker agar, and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. The bacterial loads were estimated by counting the colony-forming units in each larva at each time point. The in vivo growth curve was monitored every day for 6 days. To investigate early growth, the same experiment was performed but this time just observing the fat bodies over 24 hours, plating every 4 hours. For each condition, 3 independent experiments were performed.

Immunohistochemistry

We challenged 50 larvae with 106 CFU S75, and 2 living larvae were randomly selected at various times post-infection. Infected and uninfected larvae were fixed for 2 weeks in 4% neutral buffered formalin. For efficient embedding, the larvae were sectioned longitudinally before being placed into paraffin and processed in a Shandon Excelsior ES (Thermo Scientific). The paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4-µm sections using a Microm HM340E microtome with section transfer system (Thermo Fisher). These sections were mounted on positively charged SuperFrost Plus slides (VWR) then dried for 60 minutes at 58°C. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a Ventana purple-detection kit and their DISCOVERY ULTRA automated stainer. Following dewaxing with EZ prep solution (Ventana) at 75°C for 8 minutes, endogenous peroxidase was blocked for 12 minutes at 37°C with DISCOVERY Inhibitor (Ventana). After rinsing, the slides were incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C with Bio-Rad rabbit polyclonal anti-S. aureus antibodies (0300-0084). Signal enhancement and detection were performed using the DISCOVERY purple kit. Slides were counterstained for 16 minutes with Ventana hematoxylin II (790-2208) and for 4 minutes with Ventana bluing reagent (760-2037). They were then rinsed, manually dehydrated, and cover-slipped. Image acquisition was done with NanoZoomer (Hamamastu Photonics) and analyzed using the accompanying NDP.view2 software.

Bacterial Isolation and RNA Extraction

The protocol for differential lysis was adapted from Robbe-Saule et al. (2017), Two living larvae were randomly selected, externally disinfected with 70% ethanol, dried, then placed into Petri dishes. Using sterile forceps holding the head of the larvae, the larval contents were extracted by applying pressure using a 10 ml syringe plunger. This step allowed the cuticle and the larval contents to be correctly separated. After removing their cuticles, larval contents were mechanically homogenized in 5 ml of sterile PBS and centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatant was recovered then combined with 50 mM calcium chloride and 1 ml Proteinase K solution (12 mg/ml) supplemented with 1 M tris(hydroxylmethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (pH 8). This mix was incubated for 30 minutes at 50°C, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C. For total bacteria RNA extractions, pellets were suspended in 500 µl of lysis buffer (20 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS pH 5.5) and transferred into 1.5 ml RNase-free centrifuge tubes containing 500 µl of zirconium beads and 500 µl of phenol (pH 4). Cells were broken up in a FastPrep FP120 cell disruptor (MP Biomedicals). RNA was extracted by the phenol-chloroform method. The top clear layer was removed and RNA was precipitated overnight at -80°C in isopropanol supplemented with 0.3 M sodium acetate and glycogen. Finally, RNAs were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The pellets were then cleaned with 70% ethanol, dried, and dissolved in RNase-free water. To eliminate DNA contamination, samples were processed with the TURBO DNA-free kit (Thermo Fisher) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. A second precipitation was performed to remove putative contamination, with RNAs treated with 100% ethanol supplemented with 0.3 M sodium acetate and glycogen. RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher) and agarose gel electrophoresis.

We used proteinase K to create a differential lysis method that would preferentially degrade larval tissue, and we verified its efficiency through method development. Briefly, we first controlled that proteinase K did not significantly damage bacterial cells by comparing numbers of CFU of S. aureus before and after incubation with proteinase K in vitro. Then, we applied this method to RNA extraction, and we assessed the integrity of RNAs. Finally, we tested increasing concentrations of proteinase K on infected larvae.

Bacterial RNA extraction was also performed from in vitro cultures with a Proteinase K solution at both the mid-exponential and stationary phases in LB broth. At designated time in vitro bacteria cultures were incubated for 30 minutes at 50°C with a proteinase K solution, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. From the pellet, total RNA was extracted according to the protocol described above.

Monitoring RNA Expression Levels

We challenged 100 larvae with 106 CFU S75, and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to monitor sRNA expression during larval infection. We analyzed RNAIII, SprC, SprD, SprX, and RsaA, sRNAs present and expressed in the S75 strain (Bordeau et al., 2016), as well as the mRNA controls GyrB and SigA. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2 . RNA samples were reverse-transcribed and amplified using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit and the PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Thermo Fisher) as recommended by the manufacturer. Reverse transcription was performed using 0.3 µg of RNA in 10 µl of nuclease free water, and 10 µl of the 2X RT master mix. The reverse transcription run followed the manufacturer’s recommendations. Resulting cDNA were stored at -20° C until qPCR. For qPCR, the reaction volume was 20 µl comprising 10 µl SYBR Green 10X master mix, 5 µl cDNA diluted 1/100, forward and reverse primers at a final concentration of 500 nM, completed with nuclease free water. The reaction was performed on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System using the standard mode.

Two different methods were used for data interpretation: comparison against the in vitro RNA expression levels of S75 at the exponential and stationary growth phases; and comparison of sRNA transcript levels in the larvae at an early (12-hour) post-infection step against the levels at various post-infection times. sRNA expression was normalized against housekeeping mRNA transcripts, and their relative expression levels were inferred using the ΔΔCt method. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

G. mellonella survival profiles were determined using the log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival plots. For daily mortality comparisons, a Student’s t-test was used to compare the expressions in sRNA-deleted and isogenic strains. Sample t-tests were used for comparing the sRNA profiles between experiments, for instance in vivo versus in vitro expression during the exponential or stationary growth phases. To monitor the trend in larval sRNA expressions at each selected post-infection time point, we analyzed the variance and did multiple comparisons of means using Tukey contrasts. A two-sample test was used to analyze sRNA expression in the larvae during the first 24 hours after infection, then up to 96 hours later. Larval sRNA expression and risk-adjusted mortality rates were compared using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The risk-adjusted mortality corresponded to the ratio of the number of dead larvae to the number of larvae still alive at the time of the experiment. Results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Setting up a G. mellonella Infection Model

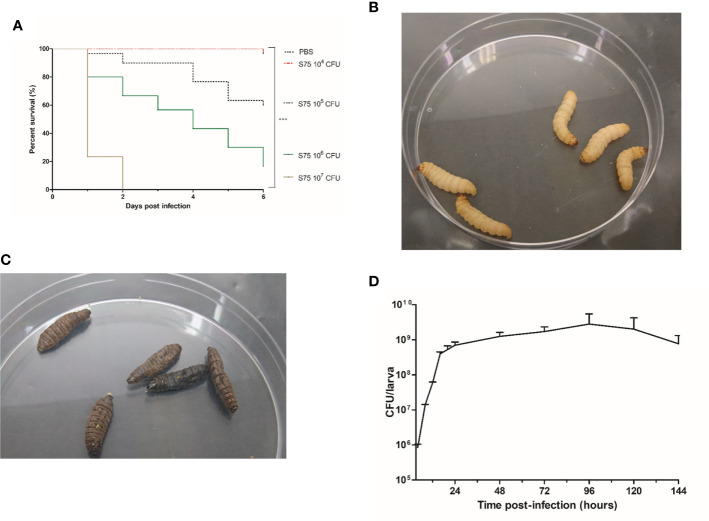

To determine larval susceptibility to infection with S. aureus S75, we injected them with different inocula and monitored mortality daily. We observed that survival rates in G. mellonella were dependent on the S75 dosage ( Figure 1A ). No deaths or melanization were detected either in the control group or after injecting 104 CFU of S75 ( Figure 1B ). However, all larvae died within 48 hours after injection with 107 CFU. At day 6, mortality was 40% and 80% after injection with 105 or 106 CFU, respectively. Dead larvae were immobile as well as black due to melanization ( Figure 1C ). For our model, we selected a dose of 106 CFU, as a gradual reduction in larval survival rates occurred over the 6-day experiments with that amount.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots and bacterial levels in infected Galleria mellonella larvae infected with Staphylococcus aureus. (A) Survival of G. mellonella larvae after inoculation with 104 to 107 CFU of the S. aureus S75 strain. Plots show an average of 3 independent experiments with 10 larvae per group (N= 150), with mortality monitored daily for 6 days. PBS-injected larvae were the negative control. Significant differences were defined as ***p < 0.001. (B) G. mellonella larvae on day 6 after being challenged with 10 µl of PBS. (C) Dead G. mellonella larvae at day 6 after infection with 106 CFU of S. aureus S75. (D) Time evolution of bacterial burden in homogenized cuticle-free larvae infected by 106 CFU of S. aureus S75. Data are the sum of 3 independent experiments, with 100 larvae per experiment (N = 300). Error bars represent the standard deviations (SD).

To determine S75 growth within the larvae, they were infected by 106 CFU, then 3 were sacrificed at different times post-infection to count the S. aureus bacteria present in the hemolymph and fat bodies. In the fat body, bacterial growth was biphasic, with a fast increase from 106 to 109 CFU/larva up to 24 hours post-infection, and a steady load of about 109 CFU/larva from day 1 to day 6 post-infection ( Figure 1D ). Growth was different in the hemolymph, with bacterial loads increasing up to 72 hours but not exceeding 6.106 CFU/larva ( Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Monitoring S. aureus Infection of Larvae With Immunohistochemical Staining

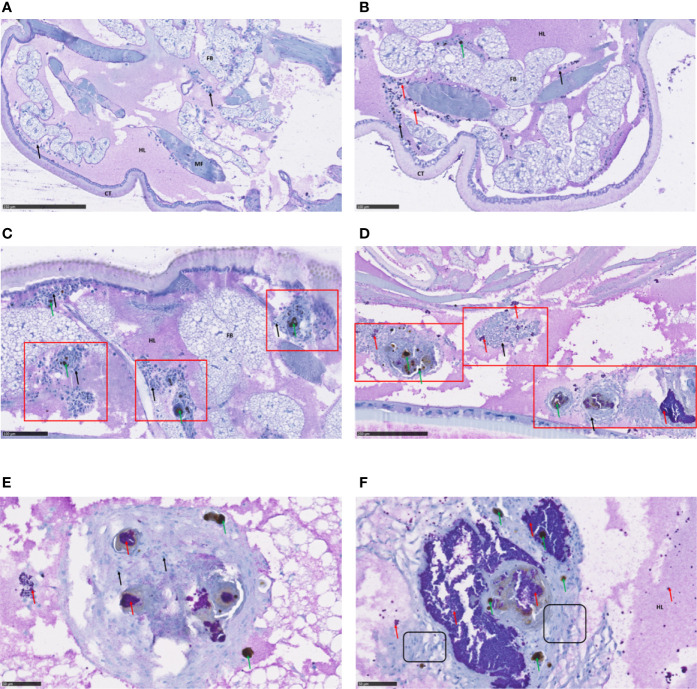

We used immunohistochemical staining and analysis to monitor infection with S. aureus S75 as well as its impact on various larval tissues up to 4 days after infection ( Figure 2 ). In the control larvae, the hemocyte immune cells were subcuticular, scattered in the fat body and around the digestive tract ( Figure 2A ). We observed an immune response in the infected larvae as early as 1 day post-infection, with hemocyte recruitment around the bacteria, which are clustered into ‘grape-like’ shapes ( Figure 2B ). Bacteria often co-localize with host immune-cells and form nodules with each other ( Figure 2C ). Infection foci spread progressively, affecting the entire larval body, including its nervous system ( Supplementary Figure 2 ). During infection, the immune response increased, with a predominance of pigmented nodules reflecting melanization ( Figure 2D ). Nodules were composed of bacteria, melanin, as well as numerous hemocytes, and we could visualize morphologically distinct immune cells ( Figures 2E, F ).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Galleria mellonella larva sections. Immunohistochemical analysis and hematoxylin staining were performed to visualize bacteria within the infected host and to examine histological sections. G. mellonella larvae were challenged with 106 CFU S. aureus S75, then collected at fixed times and examined. Shown are: (A) non-infected larvae; (B, C) infected larvae 24 hours after infection, showing evidence of immune activation; (D) infected larvae at 72 hours, with numerous nodules in the presence of hemocytes and bacteria; and (E, F) higher-magnification views of pigmented nodules at 96 hours after infection. S. aureus bacteria appeared in purple and are indicated with red arrows, hemocytes were stained in blue, with a deep blue nucleus and are indicated by black arrows, melanization (black spots) by green arrows, nodule clusters are outlined in red squares, and hemocytes of different morphology framed in black boxes. Scale bars are indicated on each picture. Key: CT, cuticle; HL, hemolymph; FB, fat body; MF, muscle fibers.

Monitoring S. aureus sRNA Expression During Infection

The challenge was to extract enough intact bacterial RNA for qRT-PCR assays of their expression levels. To create a differential lysis method which would only degrade larval tissues, we used Proteinase K. We began by showing that this serine protease does not damage bacterial cells, since the S. aureus CFU counts were not statistically different with or without Proteinase K ( Supplementary Figure 3A ). We also saw that Proteinase K did not influence the quality of the bacterial RNA ( Supplementary Figure 3B ). We were thus able to extract intact bacterial RNA from the mixture of eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells, and as expected, we observed an increased ratio of bacterial to larval RNA ( Supplementary Figure 3C ). Therefore, increasing concentrations of Proteinase K improved detection of S. aureus targets, and this was shown by the lowered cycle thresholds for the housekeeping genes gyrB and sigA ( Supplementary Table 3 ). Finally, we extracted bacterial RNA from the whole infected larvae, at time points between 12 and 96 hours after infection.

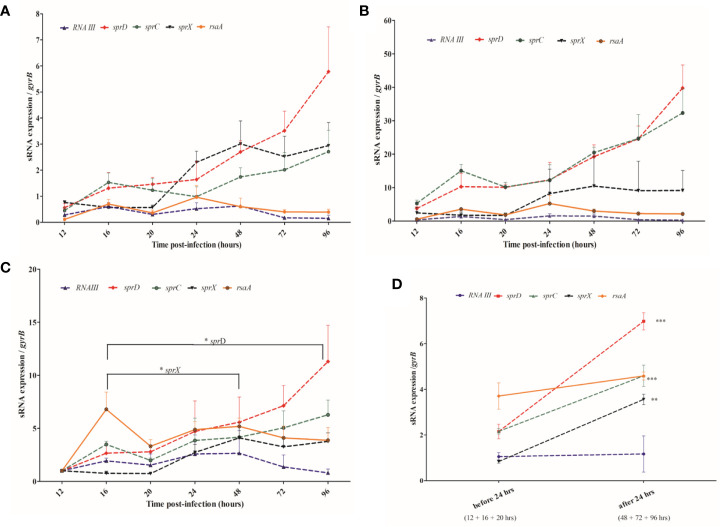

We assessed S. aureus sRNA transcript levels in situ at various times post-infection and compared these to those seen at the exponential and stationary levels in culture media ( Figures 3A, B ). We found that rnaIII and rsaA expression levels were relatively stable across the 4-day infection of the larvae. Interestingly, those of sprC, sprD, and sprX progressively increased during infection, but the expression levels of these sRNAs in the larvae were dependent upon the in vitro ‘comparator’ set and the phase examined. Indeed, ratios ranged from 2-6 when stationary phase cultures were used as a control, and from 10-40 when selecting the exponential phase cultures. In addition, whereas the in vivo gene expressions of sprD, sprC, and sprX were higher than both control conditions (respectively p < 0.0001, 0.0001, and 0.001 when compared with the in vitro exponential phase, and p = 0.0005, 0.003 and 0.001 when compared with the stationary phase), rsaA was more expressed in vivo than in the in vitro exponential phase (p = 0.001), but less expressed in vivo than the in vitro stationary phase (p = 0.0001). Such differences highlight the difficulty of choosing a good in vitro comparator. It is noteworthy that no significant difference was observed with rnaIII.

Figure 3.

Monitoring sRNA expression from 12 to 96 hours after Staphylococcus aureus infection of larva (A, B) sRNA expression levels in the Galleria mellonella larvae compared with the levels found at the stationary (A) and exponential (B) growth phases in liquid media. (C) sRNA expression levels in the larvae at various time points are compared to their values 12 hours after infection. (D) Comparison of pooled sRNA expression in the larvae before and after the 24-hour post-infection point. sRNA expression monitored by qRT-PCR was normalized against GyrB mRNA, and 3 independent experiments were realized for each condition, with 100 larvae per experiment (N= 300). Error bars represent the SDs. Significant differences were defined as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001.

Since it was difficult to compare the in vitro and in vivo sRNA expression levels, we compared in vivo sRNA expression to the first qRT-PCR value obtained at the beginning of infection, 12 hours after injection ( Figure 3C ). We saw a trend for sprC and sprD, which were both upregulated and had peaks 96 hour after injection. While sprD was significantly upregulated 16-96 hours post-infection (p = 0.043), the increase observed for sprC was not statistically significant. sprX was increased early, with a peak 48 hours after infection, and its expression was significantly higher at that point than at 16 hours (p = 0.029). rnaIII was weakly expressed at all-time points, and none of the observed variations were significant. No significant variations were observed for rsaA.

sRNA expression levels were examined in the periods before (16-20 hours) and after (48-96 hours) the 24-hour post-infection point ( Figure 3D ). Higher levels of sprC, sprD, and sprX were found after the first day of infection (p = 0.0001, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.0007, respectively), while rnaIII and rsaA expression levels stayed relatively even.

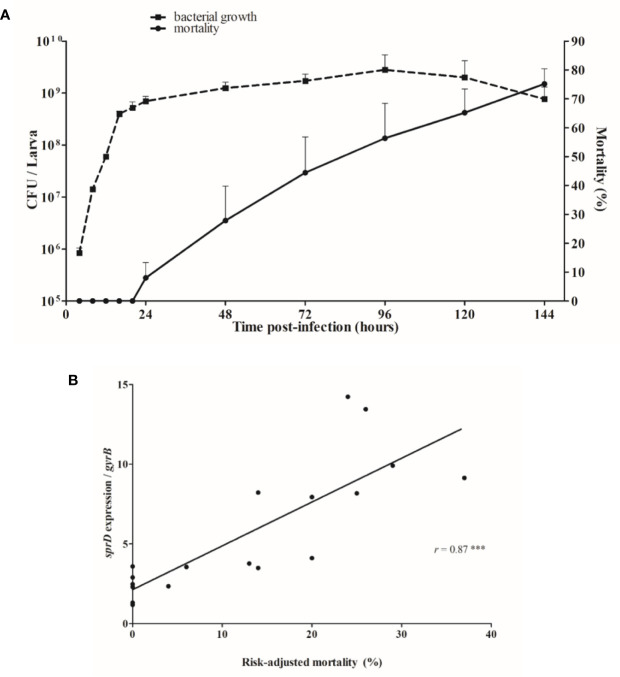

sRNAs Are Involved in G. mellonella Virulence

Larvae mortality started 1 day after infection, when the bacterial load had reached about 109 bacteria per larva, and death increased continuously thereafter ( Figure 4A ). Since time post-infection and mortality are linked, to minimize interpretation bias, we looked at how sRNA levels corresponded to the risk-adjusted mortality. In fact, sprD expression levels are strongly correlated to the risk-adjusted mortality (r = 0.87, p < 0.0001), implying that the more SprD is expressed, the more virulent the strain ( Figure 4B ).

Figure 4.

Relationship between mortality and sRNA expression levels. (A) Correlation between growth of Staphylococcus aureus (CFU/larva) and the mortality of infected Galleria mellonella larvae. (B) Correlation between sprD expression and risk-adjusted mortality. The in vivo transcript levels of sprD were calculated to those for gyrB mRNA and compared to the expression obtained 12 hours after infection. Each point represents relative sprD expression during infection associated with the risk-adjusted mortality at the same time point, and corresponds to the sum of 3 independent experiments, with 100 larvae per experiment (N= 300). Key: r, Sperman’s coefficient; ***p < 0.001.

To look for connections between sRNA expression and virulence, we compared the mortality induced by sRNA-deletion strains to that of isogenic controls. We examined S75 and two another strains, HG001 or HG003, both of which are derived from the NCTC 8325 reference strain that is phylogenetically related to S75. We did not observe any differences in larval mortality in these three ST8 strains ( Supplementary Figure 4 ).

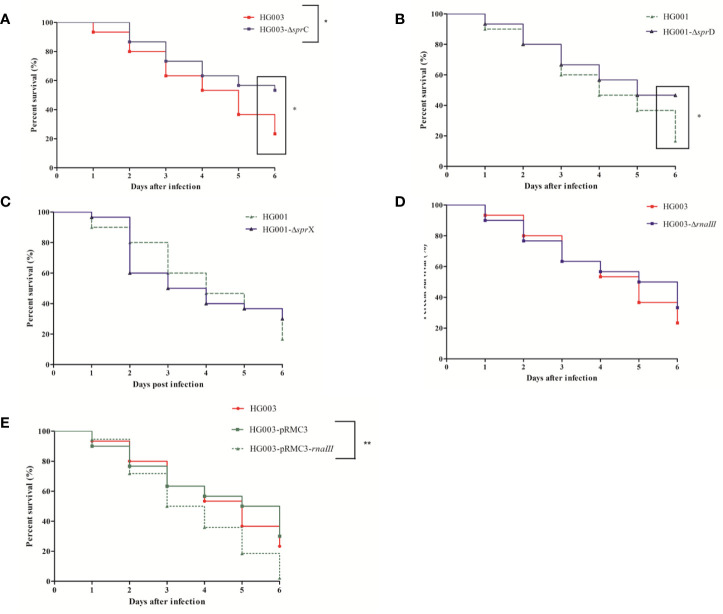

At all tested times, larval mortality was significantly reduced (p = 0.03) in comparison with the control after infection with HG003-∆sprC ( Figure 5A ). However, only late mortality (at day 6), was significantly reduced (p = 0.01) in HG001-ΔsprD infection as compared to the isogenic strain ( Figure 5B ). In contrast, no significant differences (p = 0.70 and p = 0.64, respectively) were seen after infection with HG001-ΔsprX or HG003-ΔrnaIII ( Figures 5C, D ).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots of Galleria mellonella larvae infected with various forms of Staphyllococcus aureus. Larvae were injected with 106 CFU of wild-type HG001 or HG003, three types of isogenic sRNA mutants, or with a strain overexpressing rnaIII. PBS-injected larvae were used as negative controls. Shown are the survival rates over 6 days for the following: (A) HG003 and its HG003-ΔsprC isogenic mutant; (B) HG001 and HG001-ΔsprD; (C) HG001 and HG001-ΔsprX; (D) HG003 and HG003-ΔrnaIII; and (E) HG003 compared to both HG003-pRMC3 and HG003-pRMC3-rnaIII. Significant differences were defined as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Data are shown from 3 independent experiments using 10 larvae per group for each condition.

Since rnaIII expression in the larvae was very low, we wondered whether overexpressing rnaIII would affect virulence. We found that rnaIII overexpression significantly increased mortality (p = 0.007) ( Figure 5E ), with enhanced larval necrosis and a complete destruction of larval tissue ( Supplementary Figure 5 ). High rnaIII expression thus seems to be detrimental during larval infection.

Discussion

Here, we present a G. mellonella model set up to study the impacts of S. aureus riboregulations during infection. Indeed, accumulating evidence has shown the importance of numerous sRNAs in bacterial pathogenicity (Novick, 2003; Chabelskaya et al., 2010; Morrison et al., 2012; Romilly et al., 2014; Le Pabic et al., 2015; Kathirvel et al., 2016; Manna et al., 2018). The larvae of this greater wax moth have been extensively used to study the virulence of many microorganisms (Tsai et al., 2016) and for testing the efficacy of antimicrobial compounds (Cutuli et al., 2019) for several reasons: costs are low; no specific training or equipment is required; and many larvae can be infected simultaneously. In addition, invertebrates do not possess nociceptors and are thus not sensitive to pain, so there are no restrictive ethical rules as exist for vertebrate use (Bismuth et al., 2019). G. mellonella lacks adaptive immunity, but the organism develops an innate immune response that is similar to that of vertebrates, including cellular and humoral responses which are responsible for nodulation and phagocytosis (Pereira et al., 2018). Unlike Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, infections can be performed at 37°C in G. mellonella, which is an advantage for studying the bacterial virulence of S. aureus or other human pathogens. G. mellonella infections can be caused either via ingestion or by intrahemocoelic injection, and the latter method allows for close control of the inoculum (Ramarao et al., 2012). In most studies, the model has been used to examine the antimicrobial activity of drugs or to screen for S. aureus virulence factors (Quiblier et al., 2013; Ferro et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2017). A previous work showed that G. mellonella could also be used for other purposes, especially for examining S. aureus interaction with the larval immune response and for how the bacteria induces the expression of immune-related peptides (Sheehan et al., 2019). We therefore used this model to investigate riboregulations in staphylococcal virulence. As proof of concept, we applied it to examine sRNAs already established as having major impacts on virulence.

Consistent with a recent study (Sheehan et al., 2019), we saw an early bacterial multiplication that triggered an immune response in the form of hemocyte recruitment. Majority of hemocytes are phagocytic cells similar to vertebrate neutrophils which are involved in abscess formation (Kobayashi et al., 2015). During S. aureus infection, we visualized nodules which could correspond to abscesses in vertebrate tissues. The number of nodules increased during infection as well as being spread throughout the entire larva, implying systemic infection. During human infection, circulating bacteria are scarce (Opota et al., 2015), as they are rapidly killed by phagocytes. The surviving bacteria migrate, accumulating in host organs and causing tissue damages and/or abscesses. Similarly, in infected larvae, the bacterial load is higher than in the fat body compared to the hemolymph which is the larval equivalent to the bloodstream.

We investigated how staphylococcal sRNAs were expressed during infection. The ‘proof of concept’ was achieved after we examined a subset of five sRNAs: RsaA and RNAIII which are both expressed from the core genome; and SprC, SprD, and SprX from pathogenicity islands. Indeed, with the exception of RNAIII, the expression levels of each of these sRNAs in the larvae differed from what can be observed in liquid cultures during the exponential or stationary growth phases. Therefore, in vitro sRNA expression does not mimic that of in vivo conditions, a difference already observed for other staphylococcal sRNAs isolated from nasal carriers, abscesses, cystic fibrosis patients, and mouse-model bone infections (Song et al., 2012; Szafranska et al., 2014). Frequently, the in vivo expression of these sRNAs has been arbitrarily compared to in vitro exponential or stationary growth phases, and it is therefore difficult to determine the precise evolution of staphylococcal sRNAs during disease (Song et al., 2012; Szafranska et al., 2014). Our observations agree with this, proving the importance of the calibrator used for analyzing the results. To compare bacterial colonization at different stages of infection, the in vivo gene expression of S. aureus was previously monitored (without an in vitro calibrator) in mice and cotton rats presenting with nasal colonization, bacteremia, or heart lesions (Jenkins et al., 2015). We therefore decided to apply this method to the examination of in vivo sRNA expression. In our model, we measured sRNA expression 12 to 96 hours after infection, setting the initial 12-hour value as our reference. We found that the infection stage influences sRNA expression. Variations in the expression levels of sprD and sprX, as well as their accumulation in bacterial cells throughout the infection, suggest that these sRNAs both contribute to infection. It also indicates that sRNAs are not expressed continuously, and that they are tightly regulated at the different stages of infection.

Larval mortality began at 24 hours after infection, and increased progressively. There is no link between bacterial growth and mortality, as the bacterial load remained stable between days 1 and 6. In vitro, the agr quorum-sensing (QS) system senses population density, promoting the expression of secreted proteins and inhibiting adhesins via RNAIII regulation (Novick, 2003). This system does not seem to be activated during larval infection, since the post-infection expression of rnaIII remains low. These results were further supported by the lack of significant differences we observed in larval mortality between HG003 and the HG003-∆rnaIII mutant. RNAIII does not affect S. aureus survival on fruit flies (Garcia-Lara et al., 2005), suggesting that RNAIII might not play a key role in virulence in invertebrates. However, we showed that increasing rnaIII expression actually promotes mortality, with efficient larval necrosis. Furthermore, we found low rnaIII expression levels in the infected larvae, just as low amounts were detected in a mouse model of osteomyelitis, in human abscesses, during murine vaginal colonization, and in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients (Song et al., 2012; Szafranska et al., 2014; Deng et al., 2019; Ibberson et al., 2019). Nevertheless, this sRNA is still involved in virulence since disruption of the agr QS system inhibits the upregulation of many toxins and proteases and a ΔagrB strain protects mice from mortality (Date et al., 2014). A ΔrnaIII strain was also shown to attenuate virulence in a murine intracranial abscess model (Gong et al., 2014). Numerous studies have reported agr downregulation in multiple human host niches responding to different environmental cues (Dastgheyb and Otto, 2015). Indeed, environmental cues modify the behavior of S. aureus and counter its agr system, which is sensitive to many stresses or host-derived factors such as the reactive oxygen species that are produced in infected larvae by activated hemocytes (Tsai et al., 2016; Jenul and Horswill, 2018). This could prevent agr activation, explaining the low expression of rnaIII, and thereby counterbalance S. aureus virulence. In contrast, rnaIII overexpression probably overwhelms the host immune response, which would explain the resulting virulence enhancement. Further studies are needed to clarify the central role of RNAIII in virulence regulation.

Staphylococcal virulence is also affected by others sRNAs: SprC (Le Pabic et al., 2015), SprD (Chabelskaya et al., 2010), and SprX (Kathirvel et al., 2016). The expression levels of sprC and sprD are increased when the bacteria are in contact with human serum (Carroll et al., 2016). However, little monitoring of their expression levels during animal infection has been done, so this was one objective of our study. For both SprC and SprD, expression increased progressively in infected larvae, and we observed decreased larval mortality with the ΔsprC strain. Since SprC was previously shown to attenuate staphylococcal virulence in a mouse infection model (Le Pabic et al., 2015), our data are somewhat surprising, indicating that results might vary depending on the animal model and strains used. Results of Le Pabic et al. were obtained using a Newman strain which among other changes differs with a mutation in saeS (Herbert et al., 2010). This mutation induces a particular exoprotein profile by comparison with HG003. Similarly, the survival profile in a sepsis mouse model was not strictly superposable between these two strains (Herbert et al., 2010). These differences may explain these inconsistent results. A strong positive correlation between sprD expression and risk-adjusted mortality was also observed. These preliminary results need to be confirmed in a mammalian model and in humans. S. aureus bacteremia is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality (Yilmaz et al., 2016), yet not enough relevant biomarkers have been identified for reliable prediction of clinical outcomes. The monitoring of sprD expression alone could be a potential biomarker of severity, and our observations have confirmed that SprD plays a major role in bacterial virulence in two different animal models of infection (Chabelskaya et al., 2010). SprD has one identified target, Sbi, which is an immune-evasion molecule acting at the interface between the innate and adaptive immune systems (Smith et al., 2011), and which is downregulated by SprD (Chabelskaya et al., 2010). There is no specific adaptive system in the greater wax moth, nevertheless, the staphylococcal Sbi was shown to be important in the Galleria model since the mortality was attenuated with a Δsbi USA300 strain (Zhao et al., 2020). So it is likely that SprD acts on other molecular targets to influence staphylococcal virulence.

Our study confirms the importance of sRNAs in S. aureus infection in animals, and the handy Galleria mellonella infection model can easily be extended to the investigation of all 50 bona fide sRNAs known to be expressed by S. aureus (Liu et al., 2018). sRNAs belong to complex gene regulatory networks (Fechter et al., 2014), and testing their involvement in virulence requires an understanding of their connections and interactions within the entire regulon. Our next step will be to perform a transcriptomic analysis to compare sRNA-deletion and isogenic strains in order to obtain a more comprehensive view of their participation in virulence.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: GM and P-YD. Experiments: GM and AR. Microscopy: GG and GM. Statistics: ME and GM. Writing – original draft: GM. Writing – review and editing: GM, AR, BF, and P-YD. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Yoann Augagneur and Svetlana Chabelskaya for providing S. aureus mutant strains and to Marc Hallier for the pRMC3 vector. We also thank Mohamed Sassi for phylogenetic data and annotation of the S75 strain genome. Thanks to Alain Fautrel for his help in exploring microscopy techniques and Juliana Berland for critical reading of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2021.631710/full#supplementary-material

Post-infection bacterial burden in G. mellonella. Graph showing S. aureus S75 bacterial burden over time in the hemolymph of larvae infected by 106 CFU. Data are the result of 3 independent experiments, each using 100 larvae per group. Error bars represent the SDs.

Cross-sectional analysis for monitoring infection in the larvae. (A) PBS-injected larvae, the negative controls. (B) Larvae were injected with 106 CFU of S. aureus S75, and are shown here 96 hours later. Each black ellipse represents a nodule showing melanization, and the nodules are scattered around the entire larvae, including within the nervous system (NS).

Effect of Proteinase K on total RNA extractions. (A) Bacteria in the stationary phase were treated with 3 mg/ml Proteinase K (proK) or PBS for 30 minutes at 50°C. Results are the means of 3 independent experiments and are expressed in CFU/ml. (B) Total bacterial RNA counts after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide exposure with (+) or without (-) a 3mg/ml Proteinase K solution. Bacterial RNA was extracted during the stationary phase after overnight culture. (C) Total RNA extraction of G. mellonella infected with 108 CFU of S. aureus S75. For each condition, 5 larvae were infected, and 2 were randomly chosen for RNA extraction (N= 6). RNA extraction was performed 30 minutes after injection, and several concentrations of Proteinase K were applied. For each condition, after DNAse process, total RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and 0.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival plots of larvae infected with ST8 strains. Survival of G. mellonella larvae infected with 106 CFU of the S. aureus strains S75, HG003, and HG001. Mortality was monitored for 6 days. The plot is the result of 3 independent experiments using 10 larvae per group, and PBS-injected larvae were used as a negative control.

RNAIII overexpression and macroscopic effects on infected G. mellonella larvae. Larvae were inoculated with 106 CFU and mortality monitored for 6 days, at which point dead larvae were observed. (A) Dead and melanized larvae after HG003-pRMC3 infection. (B) Larval necrosis was increased after infection with HG003-pRMC3-rnaIII.

Strains and vectors used for G. mellonella infection.

Primers used for qRTPCR.

Proteinase K Effects on the cycle thresholds of S. aureus housekeeping genes observed in qRTPCR.

References

- Bismuth H., Aussel L., Ezraty B. (2019). La teigne Galleria mellonella pour les études hôte-pathogène. Med. Sci. (Paris) 35, 346–351. 10.1051/medsci/2019071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordeau V., Cady A., Revest M., Rostan O., Sassi M., Tattevin P., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus Regulatory RNAs as Potential Biomarkers for Bloodstream Infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22, 1570–1578. 10.3201/eid2209.151801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronesky D., Wu Z., Marzi S., Walter P., Geissmann T., Moreau K., et al. (2016). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and Its Regulon Link Quorum Sensing, Stress Responses, Metabolic Adaptation, and Regulation of Virulence Gene Expression. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 70, 299–316. 10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll R. K., Weiss A., Broach W. H., Wiemels R. E., Mogen A. B., Rice K. C., et al. (2016). Genome-wide Annotation, Identification, and Global Transcriptomic Analysis of Regulatory or Small RNA Gene Expression in Staphylococcus aureus . mBio 7, e01990-15. 10.1128/mBio.01990-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabelskaya S., Gaillot O., Felden B. (2010). A Staphylococcus aureus small RNA is required for bacterial virulence and regulates the expression of an immune-evasion molecule. PloS Pathog. 6, e1000927. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin D. O., Taylor D., Skerrett S. J., Rubens C. E. (2012). Changes in the Staphylococcus aureus transcriptome during early adaptation to the lung. PloS One 7, e41329. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Moreno D., Wos-Oxley M. L., Jáuregui R., Medina E., Oxley A. P., Pieper D. H. (2016). Exploring the transcriptome of Staphylococcus aureus in its natural niche. Sci. Rep. 6, 33174. 10.1038/srep33174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutuli M. A., Petronio Petronio G., Vergalito F., Magnifico I., Pietrangelo L., Venditti N., et al. (2019). Galleria mellonella as a consolidated in vivo model hosts: New developments in antibacterial strategies and novel drug testing. Virulence 10, 527–541. 10.1080/21505594.2019.1621649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastgheyb S. S., Otto M. (2015). Staphylococcal adaptation to diverse physiologic niches: an overview of transcriptomic and phenotypic changes in different biological environments. Future Microbiol. 10, 1981–1995. 10.2217/fmb.15.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date S. V., Modrusan Z., Lawrence M., Morisaki J. H., Toy K., Shah I. M., et al. (2014). Global gene expression of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 during human and mouse infection. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1542–1550. 10.1093/infdis/jit668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Schilcher K., Burcham L. R., Kwiecinski J. M., Johnson P. M., Head S. R., et al. (2019). Identification of Key Determinants of Staphylococcus aureus Vaginal Colonization. mBio 10, e02321-19. 10.1128/mBio.02321-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechter P., Caldelari I., Lioliou E., Romby P. (2014). Novel aspects of RNA regulation in Staphylococcus aureus . FEBS Lett. 588, 2523–2529. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro T. A. F., Araújo J. M. M., dos Santos Pinto B. L., dos Santos J. S., Souza E. B., da Silva B. L. R., et al. (2016). Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits Staphylococcus aureus Virulence Factors and Protects against Infection in a Galleria mellonella Model. Front. Microbiol. 7, 2052. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Lara J., Needham A. J., Foster S. J. (2005). Invertebrates as animal models for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis: a window into host–pathogen interaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43, 311–323. 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J., Li D., Yan J., Liu Y., Li D., Dong J., et al. (2014). The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine intracranial abscesses model. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 18, 501–506. 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert S., Ziebandt A.-K., Ohlsen K., Schäfer T., Hecker M., Albrecht D., et al. (2010). Repair of Global Regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and Comparative Analysis with Other Clinical Isolates. Infect. Immun. 78, 2877. 10.1128/IAI.00088-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibberson C. B., Whiteley M. (2019). The Staphylococcus aureus Transcriptome during Cystic Fibrosis Lung Infection. mBio 10, de02774–19. 10.1128/mBio.02774-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins A., Diep B. A., Mai T. T., Vo N. H., Warrener P., Suzich J., et al. (2015). Differential Expression and Roles of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence Determinants during Colonization and Disease. mBio 6, e02272–14. 10.1128/mBio.02272-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenul C., Horswill A. R. (2018). Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 669–686. 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0031-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathirvel M., Buchad H., Nair M. (2016). Enhancement of the pathogenicity of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman by a small noncoding RNA SprX1. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 205, 563–574. 10.1007/s00430-016-0467-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S. D., Malachowa N., DeLeo F. R. (2015). Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus Abscesses. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1518–1527. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalaouna D., Massé E. (2015). Identification of sRNA interacting with a transcript of interest using MS2-affinity purification coupled with RNA sequencing (MAPS) technology. Genom. Data 5, 136–138. 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pabic H., Germain-Amiot N., Bordeau V., Felden B. (2015). A bacterial regulatory RNA attenuates virulence, spread and human host cell phagocytosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 9232–9248. 10.1093/nar/gkv783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Rochat T., Toffano-Nioche C., Le Lam T. N., Bouloc P., Morvan C. (2018). Assessment of Bona Fide sRNAs in Staphylococcus aureus . Front. Microbiol. 9, 228. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna A. C., Kim S., Cengher L., Corvaglia A., Leo S., Francois P., et al. (2018). Small RNA teg49 Is Derived from a sarA Transcript and Regulates Virulence Genes Independent of SarA in Staphylococcus aureus . Infect. Immun. 86, e00635-17. 10.1128/IAI.00635-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison J. M., Miller E. W., Benson M. A., Alonzo F., Yoong P., Torres V. J., et al. (2012). Characterization of SSR42, a Novel Virulence Factor Regulatory RNA That Contributes to the Pathogenesis of a Staphylococcus aureus USA300 Representative. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2924–2938. 10.1128/JB.06708-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick R. P., Ross H. F., Projan S. J., Kornblum J., Kreiswirth B., Moghazeh S. (1993). Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12, 3967–3975. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick R. P. (2003). Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1429–1449. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira T. C., de Barros P. P., Fugisaki L. R. de O., Rossoni R. D., Ribeiro F. de. C., de Menezes R. T., et al. (2018). Recent Advances in the Use of Galleria mellonella Model to Study Immune Responses against Human Pathogens. J. Fungi 4, 128. 10.3390/jof4040128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opota O., Jaton K., Greub G. (2015). Microbial diagnosis of bloodstream infection: toward molecular diagnosis directly from blood. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 21, 323–331. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiblier C., Seidl K., Roschitzki B., Zinkernagel A. S., Berger-Bächi B., Senn M. M. (2013). Secretome Analysis Defines the Major Role of SecDF in Staphylococcus aureus Virulence. PloS One 8, e63513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina M., King A., Bianco C., Vanderpool C. K. (2018). Dual-function RNAs. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 5. 10.1128/microbiolspec.RWR-0032-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramarao N., Nielsen-Leroux C., Lereclus D. (2012). The Insect Galleria mellonella as a Powerful Infection Model to Investigate Bacterial Pathogenesis. J. Vis. Exp. e4392. 10.3791/4392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbe-Saule M., Babonneau J., Sismeiro O., Marsollier L., Marion E. (2017). An Optimized Method for Extracting Bacterial RNA from Mouse Skin Tissue Colonized by Mycobacterium ulcerans . Front. Microbiol. 8, 512. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romilly C., Lays C., Tomasini A., Caldelari I., Benito Y., Hammann P., et al. (2014). A Non-Coding RNA Promotes Bacterial Persistence and Decreases Virulence by Regulating a Regulator in Staphylococcus aureus . PloS Pathog. 10, e1003979. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi M., Augagneur Y., Mauro T., Ivain L., Chabelskaya S., Hallier M., et al. (2015). SRD: a Staphylococcus regulatory RNA database. RNA 21, 1005–1017. 10.1261/rna.049346.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan G., Dixon A., Kavanagh K. (2019). Utilization of Galleria mellonella larvae to characterize the development of Staphylococcus aureus infection. Microbiology 165, 863–875. 10.1099/mic.0.000813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva L. N., Da Hora G. C. A., Soares T. A., Bojer M. S., Ingmer H., Macedo A. J., et al. (2017). Myricetin protects Galleria mellonella against Staphylococcus aureus infection and inhibits multiple virulence factors. Sci. Rep. 7, 2823. 10.1038/s41598-017-02712-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. J., Visai L., Kerrigan S. W., Speziale P., Foster T. J. (2011). The Sbi Protein Is a Multifunctional Immune Evasion Factor of Staphylococcus aureus . Infect. Immun. 79, 3801–3809. 10.1128/IAI.05075-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Lays C., Vandenesch F., Benito Y., Bes M., Chu Y., et al. (2012). The Expression of Small Regulatory RNAs in Clinical Samples Reflects the Different Life Styles of Staphylococcus aureus in Colonization vs. Infection. PloS One 7, e37294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafranska A. K., Oxley A. P. A., Chaves-Moreno D., Horst S. A., Roßlenbroich S., Peters G., et al. (2014). High-resolution transcriptomic analysis of the adaptive response of Staphylococcus aureus during acute and chronic phases of osteomyelitis. mBio 5, e01775–14. 10.1128/mBio.01775-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S. Y. C., Davis J. S., Eichenberger E., Holland T. L., Fowler V. G. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661. 10.1128/CMR.00134-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. J.-Y., Loh J. M. S., Proft T. (2016). Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence 7, 214–229. 10.1080/21505594.2015.1135289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belkum A., Verkaik N. J., de Vogel C. P., Boelens H. A., Verveer J., Nouwen J. L., et al. (2009). Reclassification of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage types. J. Infect. Dis. 199, 1820–1826. 10.1086/599119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Eiff C., Becker K., Machka K., Stammer H., Peters G. (2001). Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 11–16. 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim H. F. L., Melles D. C., Vos M. C., van Leeuwen W., van Belkum A., Verbrugh H. A., et al. (2005). The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 751–762. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M., Elaldi N., Balkan İ. İ, Arslan F., Batirel A. A., Bakici M. Z., et al. (2016). Mortality predictors of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a prospective multicenter study. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 15, 7. 10.1186/s12941-016-0122-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Chlebowicz-Flissikowska M. A., Wang M., Murguia E. V., Jong A., Becher D., et al. (2020). Exoproteomic profiling uncovers critical determinants for virulence of livestock-associated and human-originated Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strains. Virulence 11, 947–963. 10.1080/21505594.2020.1793525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Post-infection bacterial burden in G. mellonella. Graph showing S. aureus S75 bacterial burden over time in the hemolymph of larvae infected by 106 CFU. Data are the result of 3 independent experiments, each using 100 larvae per group. Error bars represent the SDs.

Cross-sectional analysis for monitoring infection in the larvae. (A) PBS-injected larvae, the negative controls. (B) Larvae were injected with 106 CFU of S. aureus S75, and are shown here 96 hours later. Each black ellipse represents a nodule showing melanization, and the nodules are scattered around the entire larvae, including within the nervous system (NS).

Effect of Proteinase K on total RNA extractions. (A) Bacteria in the stationary phase were treated with 3 mg/ml Proteinase K (proK) or PBS for 30 minutes at 50°C. Results are the means of 3 independent experiments and are expressed in CFU/ml. (B) Total bacterial RNA counts after agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide exposure with (+) or without (-) a 3mg/ml Proteinase K solution. Bacterial RNA was extracted during the stationary phase after overnight culture. (C) Total RNA extraction of G. mellonella infected with 108 CFU of S. aureus S75. For each condition, 5 larvae were infected, and 2 were randomly chosen for RNA extraction (N= 6). RNA extraction was performed 30 minutes after injection, and several concentrations of Proteinase K were applied. For each condition, after DNAse process, total RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and 0.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival plots of larvae infected with ST8 strains. Survival of G. mellonella larvae infected with 106 CFU of the S. aureus strains S75, HG003, and HG001. Mortality was monitored for 6 days. The plot is the result of 3 independent experiments using 10 larvae per group, and PBS-injected larvae were used as a negative control.

RNAIII overexpression and macroscopic effects on infected G. mellonella larvae. Larvae were inoculated with 106 CFU and mortality monitored for 6 days, at which point dead larvae were observed. (A) Dead and melanized larvae after HG003-pRMC3 infection. (B) Larval necrosis was increased after infection with HG003-pRMC3-rnaIII.

Strains and vectors used for G. mellonella infection.

Primers used for qRTPCR.

Proteinase K Effects on the cycle thresholds of S. aureus housekeeping genes observed in qRTPCR.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/ Supplementary Material .