Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma pneumoniae atypical pneumonia is frequently associated with erythema multiforme. Occasionally, a mycoplasma infection does not trigger any cutaneous but exclusively mucosal lesions. The term mucosal respiratory syndrome is employed to denote the latter condition. Available reviews do not address the possible association of mucosal respiratory syndrome with further atypical bacterial pathogens such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, or Legionella species. We therefore performed a systematic review of the literature addressing this issue in the National Library of Medicine, Excerpta Medica, and Web of Science databases.

Summary

We found 63 patients (≤18 years, n = 36; >18 years, n = 27; 54 males and 9 females) affected by a mucosal respiratory syndrome. Fifty-three cases were temporally associated with a M. pneumoniae and 5 with a C. pneumoniae infection. No cases temporally associated with C. psittaci, C. burnetii, F. tularensis, or Legionella species infection were found. Two cases were temporally associated with Epstein-Barr virus or influenzavirus B, respectively.

Keywords: Mucosal respiratory syndrome, Fuchs syndrome, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Epstein-Barr virus, Influenzavirus B, COVID-19, Respiratory infection, Child

Introduction

Erythema multiforme is an acute skin disease, which is characterized by the onset of symmetrical fixed red lesions, some of which evolve into distinctive papular “target” lesions. Mucosal lesions, which frequently develop a few days after the rash begins, divide this disease into 2 types: in erythema multiforme minus there is not more than 1 mucous membrane involvement, while in erythema multiforme majus 2 or more mucous membranes are involved [1, 2, 3]. Erythema multiforme predominantly occurs in pre-adolescents, adolescents, and young adults [1, 2, 3]. Several drugs are known to induce erythema multiforme. Approximately 90% of cases, however, occur in individuals affected by a Herpes simplex virus or Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection [4].

Occasionally, a mycoplasma infection does not trigger any cutaneous but exclusively mucosal lesions. To the best of our knowledge, this association was first reported in 1945 [5] as mucosal respiratory syndrome and is currently known as M. pneumoniae-associated isolated mucositis. The condition has also been termed “atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome,” “Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions,” “erythema multiforme majus without skin lesions,” and, in German-speaking regions, “Fuchs syndrome” [1, 2, 3].

We recently managed an adolescent presenting with atypical pneumonia and extensive mucositis precipitated by Chlamydophila pneumoniae, a further atypical bacterial pathogen [6]. Since textbooks and reviews exclusively refer to the association of mucosal respiratory syndrome with M. pneumoniae, we systematically analyzed the available literature.

Methods

Search Strategy

A search of the literature with no date and language [7] limits was performed on the National Library of Medicine, Excerpta Medica, and Web of Science databases following the Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [8]. The search terms included (“atypical pneumonia” OR “Chlamydia pneumoniae” OR “Chlamydia psittaci” OR “Chlamydophila pneumoniae” OR “Chlamydophila psittaci” OR “Coxiella burnetii” OR “Francisella tularensis” OR “Legionella” OR “Mycoplasma pneumoniae”) AND (“atypical Steven-Johnson syndrome” OR “Fuchs syndrome” OR “herpes oris conjunctivae” OR “mucosal respiratory syndrome” OR “Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated isolated mucositis” OR “Stevens-Johnson syndrome”). The search was conducted on January 31, 2020 and updated on June 30, 2020. References of selected publications and personal files were also reviewed for eligible reports. The literature search and the data extraction were carried out independently by 2 investigators (G.D.L. and M.M.). Conflicts were resolved by consensus or by an adjudicator (M.G.B.).

Selection Criteria: Data Extraction

Previously healthy subjects without any pre-existing chronic condition were included. We retained the diagnosis of mucosal respiratory syndrome in subjects presenting with the following 2 criteria: (a) a mucositis affecting at least 2 mucous membranes (including the oral region), which was isolated, that is without skin involvement (or with lesions affecting <0.5% of the skin surface and without any cutaneous target lesion); (b) temporally associated (≤7 days) with a symptomatic respiratory infection or with positive microbiological testing for M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, C. psittaci, C. burnetii, F. tularensis, or Legionella species. Cases of mucosal respiratory syndrome possibly precipitated by M. pneumoniae and by a further microorganism (or a pharmacological co-trigger) were considered to be due to Mycoplasma.

From each retained case, data were extracted using a piloted form and transcribed into a dedicated worksheet. The data sorted from each case meeting the study criteria included demographics and both clinical and laboratory data.

Completeness of Reporting

For each published case, reporting completeness was assessed using 3 items: (1) description of clinical features including imaging studies; (2) testing for infectious agents possibly associated with mucosal respiratory syndrome, and (3) management. Each component was rated as 0, 1, or 2 and the reporting quality was graded according to the sum of each item as high (score ≥4), satisfactory (score 3), or low (score ≤2).

Analysis

Results are presented either as median with interquartile range or frequency, as appropriate. The kappa coefficient was used to evaluate the agreement between investigators in the literature search. The Fisher test was used to compare dichotomous variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Search Results

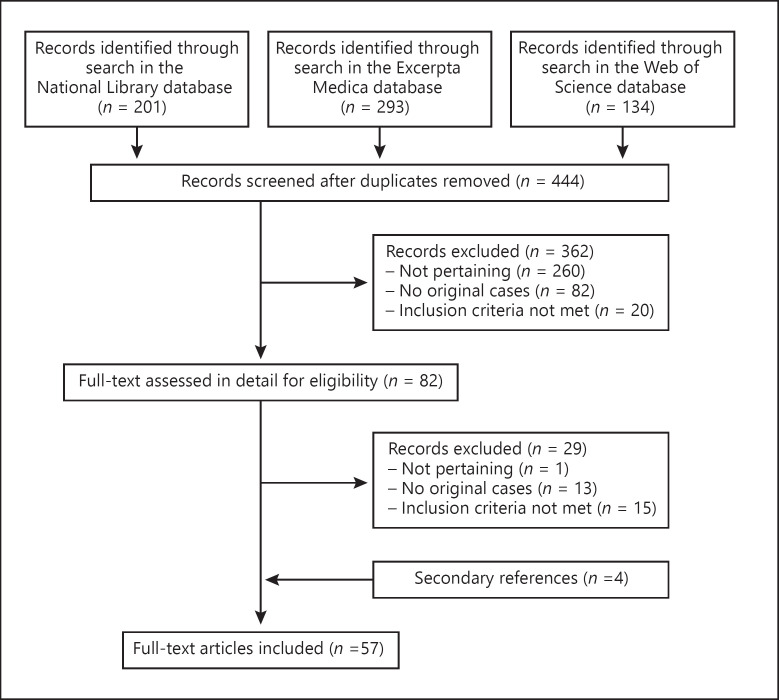

The literature search returned 444 potentially relevant records (Fig. 1). After the exclusion of 362 non-significant records, 82 potentially eligible reports were considered. The kappa coefficient between the 2 investigators on the application of exclusion and inclusion criteria was 0.91. Fifteen reports detailing 16 cases were excluded because mucositis was associated with skin lesions covering more than 1% of the skin surface or with target skin lesions. Ultimately, 57 articles were retained for analysis [5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63]. They had been published between 1945 and 2020 in English (n = 50), Spanish (n = 3), Danish (n = 2), French (n = 1), and Italian (n = 1). They had been reported from the following continents: 25 from Europe (Germany, n = 3; Spain, n = 3; Switzerland, n = 3; UK, n = 3; Denmark, n = 2; France, n = 2; the Netherlands, n = 2; Austria, n = 1; Belgium, n = 1; Czech Republic, n = 1; Ireland, n = 1; Italy, n = 1; Poland, n = 1; Portugal, n = 1), 23 from America (USA, n = 19; Canada, n = 1; Argentina, n = 1; Chile, n = 1; Mexico, n = 1), 6 from Asia (Japan, n = 3; Bahrain, n = 1; India, n = 1; South Korea, n = 1), and 3 from Oceania (all from New Zealand).

Fig. 1.

Mucosal respiratory syndrome − flowchart of the literature search process.

Findings

The aforementioned articles included 63 patients (54 males and 9 females, aged 3–46 years, median age 17 years), as shown in Table 1. Reporting completeness was high in 54 and satisfactory in the remaining 9 cases. In addition to oral mucositis in all cases, an ocular and a genital mucositis were reported in the vast majority of cases. Furthermore, a colorectal involvement was reported in 3 cases. Interestingly, 6 cases were not associated with respiratory symptoms or signs but uniquely with laboratory features consistent with either a M. pneumoniae (n = 5) or C. pneumoniae (n = 1) infection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 63 patients aged 3–46 years affected by an acute isolated mucositis involving at least 2 foci

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 54 (86) |

| Female | 9 (14) |

| Age | |

| <18 years | 36 (57) |

| >18 years | 27 (43) |

| Mucosal involvement | |

| Mouth | 63 (100) |

| Eyes | 60 (95) |

| Genital | 41 (65) |

| Nose | 10 (16) |

| Ear | 3 (4.7) |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (4.7) |

| Absent respiratory disease | 6 (9.5) |

| Presumed infectious trigger | |

| M. pneumoniae | 53 (84)1 |

| C. pneumoniae | 5 (7.9) |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 1 (1.6) |

| Influenzavirus B | 1 (1.6) |

| Microorganism unknown | 3 (4.8) |

| Possible pharmacological co-trigger | 2 (3.2)2 |

| Immunomodulatory drug treatment | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 27 (43) |

| Intravenous immunoglobulins | 3 (4.8) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Respiratory syncytial virus was also isolated in 1 of the 53 cases.

Duloxetine (n = 1), diclofenac (n = 1).

The laboratory diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection was made in 53 and that of C. pneumoniae infection in 5 cases [6, 41, 55, 62, 63]. The diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection (n = 53) was made by means of a relevant rise in immunoglobulin G titer in paired blood samples (n = 26), a positive mycoplasma testing in a respiratory tract sample (n = 15), or both a relevant rise in immunoglobulin G titer and a positive mycoplasma testing (n = 10). No detailed information was available for the 2 remaining mycoplasma cases. The diagnosis of C. pneumoniae (n = 5), respiratory syncytial virus (n = 1), or influenzavirus B (n = 1) infection was made by means of a positive testing for the microorganism in a respiratory tract sample. Immunoglobulin M antibodies directed against the Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen were detected in the case with the diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus infection. No case temporally associated with C. psittaci, C. burnetii, F. tularensis, or Legionella species infection was reported.

Two cases were temporally associated with Epstein-Barr virus [45] or influenzavirus B, respectively [46]. In 1 of the aforementioned 53 mycoplasma cases, laboratory testing was positive also for respiratory syncytial virus [22]. The microorganism underlying mucosal respiratory syndrome remained unclear in the 3 patients who presented with mucositis and pneumonia before 1953 [5, 9, 10]. In 2 cases, the authors ascribed the mucositis both to the associated infection and to medication with diclofenac or duloxetine, respectively [36, 50].

Apart from antimicrobials and local measures, systemic glucocorticoids or polyclonal intravenous immunoglobulins were prescribed in many cases.

The patient reported in 1945 died [5]. The time to recovery, which was not reported in 9 of the 63 cases, was ≥4 weeks in 16 cases.

Discussion

This careful literature review confirms that, in the vast majority of cases, mucosal respiratory syndrome is precipitated by a M. pneumoniae infection and demonstrates for the first time that approximately 10% of cases are associated with C. pneumoniae, a further atypical bacterial pathogen. However, the literature review did not disclose cases of mucosal respiratory syndrome possibly associated with C. psittaci, C. burnetii, F. tularensis, or Legionella species infection. Finally, a possible association with Epstein-Barr virus or respiratory syncytial virus infection was also noted.

In addition to the so far rather uncommon but descriptively appropriate and convenient term mucosal respiratory syndrome, further terms such as atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions, erythema multiforme majus without skin lesions, and M. pneumoniae-associated isolated mucositis have also been employed in the literature. It has also been stated that mucosal respiratory syndrome was first reported in Vienna [64] by the ophthalmologist Ernst Fuchs (1851–1930). Hence, the designation “herpes oris (et) conjunctivae Fuchs” is also sometimes used. However, we were not able to find any original communication in support of this assumption.

The mechanisms underlying the development of mucosal respiratory syndrome related to atypical bacterial pathogens such as M. pneumoniae are poorly understood. The clinical features and the histology of erythema multiforme precipitated by M. pneumoniae are more similar to drug-induced erythema multiforme than to herpes-associated erythema multiforme. Furthermore, studies investigating the presence of Mycoplasma pneumonia deoxyribonucleic acid were negative. Therefore, it is currently supposed that the pathogenesis of M. pneumoniae-associated erythema multiforme is mostly indirect and immune mediated [65, 66].

Interestingly, the diagnosis of isolated mucositis likely brought on by cotrimoxazole allergy was made in a 25-year-old Black American presenting with oral and conjunctival mucositis but without any respiratory symptom or laboratory evidence of Mycoplasma or Chlamydophila infection [67].

Two thirds of patients with M. pneumoniae-associated erythema multiforme are pre-adolescents, adolescents, or young adults of male sex [65, 66]. Similarly, the mucosal respiratory syndrome almost exclusively (87%) occurred in male subjects. Interestingly, however, 11 cases of isolated Mycoplasma species-associated vulvar mucositis have been reported in the literature, as recently reviewed [68].

It is widely held that antimicrobials, which speed recovery of atypical pneumonia, do not shorten the course of mucocutaneous manifestations [69]. The management is supportive and guided by clinical presentation and severity [70]. Mild cases can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Adequate fluid intake and pain control should also be considered in cases with extensive mucosal involvement. Severe cases are best managed by a multidisciplinary team coordinated by a dermatologist. It is currently impossible to issue recommendations for any systemic therapy. There is no clear-cut evidence that systemic corticosteroids provide any advantage. On the contrary, an older study found that patients treated with systemic corticosteroids took longer to heal than individuals who only received supportive management. On the other hand, these drugs might accelerate the disappearance of symptoms and signs in children [70]. Polyclonal intravenous immunoglobulins are another option, but their use is controversial. Based on a meta-analysis, early administration of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (2.0 g/kg body weight) may be considered in very severe cases. However, an increasing number of reports suggest that, at least in adulthood, intravenous immunoglobulins have hardly any effect on mortality [70].

Skin lesions resembling erythema multiforme have been noted in patients affected with coronavirus disease 2019 [71]. Hence, the latter condition deserves consideration in febrile subjects with mucosal respiratory syndrome. The results of this report must be seen with an understanding of the inherent limitations of the analysis process, which is based on the scanty literature available.

Conclusion

The results of the present analysis indicate that erythema multiforme precipitated by M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae may be characterized by a phenotype of mucous membrane involvement without cutaneous lesions. It has been proposed to reclassify the mucocutaneous diseases associated with M. pneumoniae by replacing the designation erythema multiforme with that of “mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis” [65]. The results of this analysis prompt us to consider the designation “rash and mucositis associated with atypical respiratory pathogens.”

Key Message

This literature review confirms that, in the vast majority of cases, mucosal respiratory syndrome is precipitated by a Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, and demonstrates for the first time that approximately 10% of cases are associated with Chlamydophila pneumoniae.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The research related to this study did not receive any funding or financial support.

Author Contributions

M.G.B., S.A.G.L., and G.P.M. were responsible for the conception and design of the study. M.G.B., G.D.L., and M.M. were responsible for the literature screening, article selection, and data extraction. G.D.L., L.K., G.D.S., I.T., and L.Z. were responsible for the interpretation of data. M.G.B., S.A.G.L., and G.P.M. were responsible for statistical analysis. M.G.B., G.D.L., and M.M. were responsible for manuscript preparation. M.G.B., S.A.G.L., and G.P.M. critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Huff JC. Erythema multiforme. Dermatol Clin. 1985 Jan;3((1)):141–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012 Aug;51((8)):889–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Harr T. Current perspectives on Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018 Feb;54((1)):147–76. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8654-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludlam GB, Bridges JB, Benn EC. Association of Stevens-Johnson syndrome with antibody for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Lancet. 1964 May;1((7340)):958–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91746-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanyon JH, Warner WP. Mucosal respiratory syndrome. Can Med Assoc J. 1945 Nov;53((5)):427–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Luigi G, Kottanattu L, Simonetti GD. Perla pediatrica: polmonite associata a lesioni delle mucose. Trib Med Tic. 2020;85((1)):22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google translate for abstracting data from non-english-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Nov;171((9)):677–9. doi: 10.7326/M19-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151((4)):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bragg F, Commission on Acute Respiratory Diseases ASSOCIATION of pneumonia with erythema multiforme exudativum. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1946 Dec;78((6)):687–710. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1946.00220060060004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugarman H, Baltzan DM. Mucosal respiratory syndrome. Can Med Assoc J. 1952 Jan;66((1)):68–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sieber OF, Jr, John TJ, Fulginiti VA, Overholt EC. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. JAMA. 1967 Apr;200((1)):79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannell H, Churcher GM, Milton-Thompson GJ. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Br J Dermatol. 1969 Mar;81((3)):196–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb16006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lods F, Gramet C, Ghenassia C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae et syndrome bulleux des muqueuses. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1983 Feb;83((2)):323–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch KJ, Burke WA, Irons TG. Recurrent erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Nov;17((5 Pt 1)):839–40. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alter SJ, Stringer B. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections associated with severe mucositis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990 Oct;29((10)):602–4. doi: 10.1177/000992289002901012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmon P, Rademaker M. Erythema multiforme associated with an outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae function. N Z Med J. 1993 Oct;106((966)):449–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barfod TS, Pedersen C. Svaer stomatit udløst af infektion med mycoplasma pneumoniae. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999 Nov;161((46)):6363–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirke S, Powell FC. Mucosal erosions and a cough. Ir Med J. 2003 Sep;96((8)):245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanfleteren I, Van Gysel D, De Brandt C. Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a diagnostic challenge in the absence of skin lesions. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003 Jan-Feb;20((1)):52–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.03012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schalock PC, Dinulos JG. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions: fact or fiction? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Feb;52((2)):312–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Ru MH, Sukhai RN. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2007 Dec;166((12)):1303–4. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0402-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fearon D, Hesketh EL, Mitchell AE, Grimwood K. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by pneumomediastinum and severe mucositis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007 May;43((5)):403–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latsch K, Girschick HJ, Abele-Horn M. Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions. J Med Microbiol. 2007 Dec;56((Pt 12)):1696–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravin KA, Rappaport LD, Zuckerbraun NS, Wadowsky RM, Wald ER, Michaels MM. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007 Apr;119((4)):e1002–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillebrand-Haverkort ME, Budding AE, bij de Vaate LA, van Agtmael MA. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection with incomplete Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 Oct;8((10)):586–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sendi P, Graber P, Lepère F, Schiller P, Zimmerli W. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008 Apr;8((4)):268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walicka M, Majsterek M, Rakowska A, Słowińska M, Sicińska J, Góralska B, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced pneumonia with Stevens-Johnson syndrome of acute atypical course. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2008 Jul-Aug;118((7-8)):449–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artés Figueres M, Oltra Benavent M, Fernández Calatayud A, Revert Gomar M. Mucositis grave inducida por Mycoplasma pneumoniae. An Pediatr (Barc) 2009 Dec;71((6)):573–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi SH, Lee YM, Rha YH. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin manifestations. Korean J Pediatr. 2009;52((2)):247–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Havliza K, Jakob A, Rompel R. Erythema multiforme majus (Fuchs syndrome) associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009 May;7((5)):445–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villarroel J, Bustamante MC, Denegri M, Pérez L. Manifestaciones muco-cutáneas de la infección por Mycoplasma pneumoniae: presentación de cuatro casos. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2009 Oct;26((5)):457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bressan S, Mion T, Andreola B, Bisogno G, Da Dalt L. Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis treated with immunoglobulins. Acta Paediatr. 2011 Nov;100((11)):e238–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGouran DC, Petterson T, McLaren JM, Wolbinski MP. Mucositis, conjunctivitis but no rash - the “Atypical Stevens - Johnson syndrome”. Acute Med. 2011;10((2)):81–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer Sauteur PM, Gansser-Kälin U, Lautenschlager S, Goetschel P. Fuchs syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions) Pediatr Dermatol. 2011 Jul-Aug;28((4)):474–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramasamy A, Patel C, Conlon C. Incomplete Stevens-Johnson syndrome secondary to atypical pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Oct;2011(oct03 1):0820114568. doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2011.4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strawn JR, Whitsel R, Nandagopal JJ, Delbello MP. Atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an adolescent treated with duloxetine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011 Feb;21((1)):91–2. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hochreiter D, Jackson JM, Shetty AK. Fever, severe mucositis, and conjunctivitis in a 15-year-old male. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012 Nov;51((11)):1103–5. doi: 10.1177/0009922812460915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li K, Haber RM. Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions (Fuchs syndrome): a literature review of adult cases with Mycoplasma cause. Arch Dermatol. 2012 Aug;148((8)):963–4. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schomburg J, Vogel M. A 12-year-old boy with severe mucositis: extrapulmonary manifestation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Klin Padiatr. 2012 Mar;224((2)):94–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trapp LW, Schrantz SJ, Joseph-Griffin MA, Hageman JR, Waskow SE. A 13-year-old boy with pharyngitis, oral ulcers, and dehydration. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis. Pediatr Ann. 2013 Apr;42((4)):148–50. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20130326-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milner TL, Gomez Mendez LM. Stevens-Johnson syndrome, mucositis, or something else? Hosp Pediatr. 2014 Jan;4((1)):54–7. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2013-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yachoui R, Kolasinski SL, Feinstein DE. Mycoplasma pneumoniae with atypical stevens-johnson syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2013;2013:457161. doi: 10.1155/2013/457161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Šternberský J, Tichý M. Fuchs' syndrome (Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin involvement) in an adult male—a case report and general characteristics of the sporadically diagnosed disease. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22((4)):284–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varghese C, Sharain K, Skalski J, Ramar K. Mycoplasma pneumonia-associated mucositis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Mar;2014(mar13 1):2014203795. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-203795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anders UM, Taylor EJ, Kravchuk V, Martel JR, Martel JB. Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions: a rare and clinically challenging disease in the urgent setting. Emerg Med Open J. 2015;1((2)):22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Majima Y, Ikeda Y, Yagi H, Enokida K, Miura T, Tokura Y. Colonic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome-like mucositis without skin lesions. Allergol Int. 2015 Jan;64((1)):106–8. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangal S, Narang T, Saikia UN, Kumaran MS. Fuchs syndrome or erythema multiforme major, uncommon or underdiagnosed? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015 Jul-Aug;81((4)):403–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.158640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vujic I, Shroff A, Grzelka M, Posch C, Monshi B, Sanlorenzo M, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis—case report and systematic review of literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Mar;29((3)):595–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alcántara-Reifs CM, García-Nieto AV. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis. CMAJ. 2016 Jul;188((10)):753. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurata M, Kano Y, Sato Y, Hirahara K, Shiohara T. Synergistic Effects of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and drug reaction on the development of atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome in adults. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016 Jan;96((1)):111–3. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Contestable JJ, Ward ML. A case of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis. Consultant. 2017;57((12)):698–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Andrés B, Tejeda V, Arrozpide L. Mucositis por Mycoplasma: un caso clínico que apoya su diferenciación del síndrome de Stevens Johnson. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 2017;45((3)):224–7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gossart R, Malthiery E, Aguilar F, Torres JH, Fauroux MA. Fuchs syndrome: medical treatment of 1 case and literature review. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017 Apr;9((1)):114–20. doi: 10.1159/000468978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kheiri B, Alhesan NA, Madala S, Assasa O, Shen M, Dawood T. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated Fuchs syndrome. Clin Case Rep. 2017 Dec;6((2)):434–5. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, Del Rosal-Rabes T, González-Sainz FJ, Sánchez-Orta A, et al. Mucositis secondary to Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017 Jul;34((4)):465–72. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shihadeh MD. Mycoplasma pneumonia-induced rash and mucositis. Bahrain Med Bull. 2017;39((2)):126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowling M, Schmutzler T, Glick S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced mucositis without rash in an 11-year-old boy. Clin Case Rep. 2018 Feb;6((3)):551–2. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Espinoza-Camacho D, Monge-Ortega OP, Sedó-Mejía G. Síndrome de Steven-Johnson atípico inducido por Mycoplasma pneumoniae: un reto diagnóstico. Rev Alerg Mex. 2018 Oct-Dec;65((4)):437–41. doi: 10.29262/ram.v65i4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zão I, Ribeiro F, Rocha V, Neto P, Matias C, Jesus G. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis: a recently described entity. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2018 Nov;5((11)):000977. doi: 10.12890/2018_000977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demitsu T, Kawase M, Nagashima K, Takazawa M, Yamada T, Kakurai M, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis with severe blistering stomatitis and pneumonia successfully treated with azithromycin and infusion therapy. J Dermatol. 2019 Jan;46((1)):e38–9. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hildebrandt ME, Agersted AB, Sejersen TS, Homøe P. [Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis in a 17-year-old girl] Ugeskr Laeger. 2019 Oct;181((43)):V07190377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umapathi KK, Tuli J, Menon S. Chlamydia pneumonia - induced mucositis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019 Dec;60((6)):697–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brazel D, Kulp B, Bautista G, Bonwit A. Rash and mucositis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae: a recurrence of MIRM? J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Müller A, McGhee CN. Professor Ernst Fuchs (1851-1930): a defining career in ophthalmology. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003 Jun;121((6)):888–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.6.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, Shinkai K. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Feb;72((2)):239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amode R, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Ortonne N, Bounfour T, Pereyre S, Schlemmer F, et al. Clinical and histologic features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-related erythema multiforme: A single-center series of 33 cases compared with 100 cases induced by other causes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jul;79((1)):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Canter NB, Smith LM. Incomplete Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Caused by Sulfonamide Antimicrobial Exposure. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019 May;3((3)):240–2. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.4.42551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vismara SA, Lava SA, Kottanattu L, Simonetti GD, Zgraggen L, Clericetti CM, et al. Lipschütz's acute vulvar ulcer: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr. 2020 Oct;179((10)):1559–67. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03647-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Luigi G, Zgraggen L, Kottanattu L, Simonetti GD, Terraneo L, Vanoni F, et al. Skin and Mucous Membrane Eruptions Associated with Chlamydophila Pneumoniae Respiratory Infections: literature Review. Dermatology. 2020 Mar;•••:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000506460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McPherson T, Exton LS, Biswas S, Creamer D, Dziewulski P, Newell L, et al. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in children and young people, 2018. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Jul;181((1)):37–54. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 May;34((5)):e212–3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]