Abstract

Respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms are the predominant clinical manifestations of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Infecting intestinal epithelial cells, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 may impact on host's microbiota and gut inflammation. It is well established that an imbalanced intestinal microbiome can affect pulmonary function, modulating the host immune response (“gut-lung axis”). While effective vaccines and targeted drugs are being tested, alternative pathophysiology-based options to prevent and treat COVID-19 infection must be considered on top of the limited evidence-based therapy currently available. Addressing intestinal dysbiosis with a probiotic supplement may, therefore, be a sensible option to be evaluated, in addition to current best available medical treatments. Herein, we summed up pathophysiologic assumptions and current evidence regarding bacteriotherapy administration in preventing and treating COVID-19 pneumonia.

Keywords: Dysbiosis, COVID-19, Gut-lung axis, Probiotics, Systemic cytokine storm

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), has been more than a disease outbreak. Aside from putting an unprecedented strain on health-care systems, the global economy, and society, it boosted the research community worldwide toward new therapeutic options as never before. Surprisingly, among all treatment strategies tested in Randomized Controlled Studies (RCTs) so far, the most effective resulted in being the simplest and mostly available at times [1 ]. While over the first hit of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, multiple drugs that had already been tested in other conditions with similar infection patterns (i.e., Ebola virus, MERS-CoV) were deployed at this stage of the pandemic specific methods based on physiopathology to prevent and treat COVID-19 are expected to emerge.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) acts as a functional receptor for SARS-CoV-2 [2 ]. As the alveolar epithelial cells, enterocytes equally express ACE2 receptors in the brush border membrane [3 ], representing, therefore, an entry point and reservoir for the virus [4 ].

A growing body of evidence suggests that alteration of intestinal flora composition, the so-called dysbiosis, which was observed in COVID-19 patients, may play a relevant role in determining the course of the disease by increasing systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine production [5 , 6 ]. Since oral bacteriotherapy is able to restore the composition of intestinal flora and therefore modulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production [7 ], its potential clinical impact in COVID-19 patients should be thoroughly evaluated.

SARS-CoV-2 and GUT: An Undervalued Relationship

In addition to fever and typical pulmonary infection manifestations, an increasing number of patients with COVID-19 reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, stomach discomfort, and gastrointestinal bleeding [4 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Interestingly, the COVID-19 patients experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms had a more severe respiratory disease to the extent that these symptoms could be used to predict ventilatory support requirement and ICU admission.

It is now well-recognized that ACE2 receptor is equally expressed in the lung and the intestinal epithelium. In particular, studies involving immunofluorescence techniques showed that this protein is largely expressed in gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelial glandular cells, representing a possible gateway for SARS-CoV-2 [11 ]. In this context, SARS-CoV-2 could be responsible for gastrointestinal inflammation [12 ] leading to malabsorption, intestinal disorders, activation of the enteric nervous system, and, ultimately, diarrhea.

Indeed, the interaction of specific SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins with ACE2 receptor could induce pro-inflammatory chemokine and cytokine excessive release. This massive release, a hallmark of COVID-19 patients, leads to an acute intestinal inflammatory response, confirmed by raised levels of fecal calprotectin and serum IL-6, and to multi-organ damage consequent to systemic cytokine storm [5 , 6 ].

In addition to that, gut ACE2 is also a relevant regulator of amino acid transport, being a chaperone for the membrane trafficking of neutral amino acid transporter (B0AT1), which is expressed both in the proximal kidney tubule and the small intestine [13 , 14 ]. Considering that ACE2 deficient mice were found to have low plasma levels of tryptophan, increased susceptibility to ulcerative colitis, and severe diarrhea [15 ], it was postulated that SARS-CoV-2 might alter intestinal microbiome and inflammatory response affecting local amino acid metabolism [13 , 15 , 16 ].

Moreover, this alternative mechanism could also promote an excessive gut permeability through epithelial tight junctions' alterations affecting the intestinal barrier function in COVID-19 patients. This was associated with a profound increase of Zonulin, a well-known physiological regulator of tight junction complex in the digestive tract, which was also found to be correlated with higher mortality in COVID-19 patients [17 ].

These pieces of evidence point out that the gut may represent a route of infection and a SARS-CoV-2 reservoir [4 , 18 ]. Indeed, up to 50% of patients released SARS-CoV-2 and its nucleic acid in the stool samples during the disease's acute phase. The infection itself generally lasted longer in COVID-19 patients who had previously experienced gastrointestinal symptoms.

Microbiome and Gut-Lung Axis

Nobel et al. [19 ] reported that SARS-CoV-2 infection generally lasted longer in COVID-19 patients who had previously experienced gastrointestinal problems. Besides, subjects with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease experience a more severe course of COVID-19 disease. All these co-morbidities have a common denominator: gut dysbiosis.

Not surprisingly, compared to healthy controls, some COVID-19 patients showed microbial dysbiosis with decreased levels of beneficial bacteria as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, lower bacterial diversity, and higher relative abundance of opportunistic pathogens including Streptococcus spp., Rothia spp., Veillonella spp., and Actinomyces spp [18 ]. It is becoming increasingly clear that the loss of certain intestinal bacterial strains might be responsible for a dysregulated immune response to SARS-CoV-2 [20 ]. Far away from being considered just part of the digestive tract, the gut is crucially involved in the immune system, hosting a large microbial population that can affect the body's respiratory tract through immune regulation [21 , 22 ].

The “gut-lung axis” refers to the bidirectional cross-talk between the intestinal tract and the lungs, whose ultimate scope is to modulate the immune response in both compartments as a result of their respective microbial composition and related patterns [23 ]. This gut-lung interplay embraces multiple anatomical communications and complex pathways [24 ]. The mesenteric lymphatic system is one of those. Using this route, intact bacteria, their fragments, or metabolites can cross the intestinal barrier and reach the circulatory system influencing other organs' immune response, among these the lung [25 , 26 , 27 ]. However, although the gut's impact on respiratory function is well reckoned, the available evidence of the other way round is still sparse. Nevertheless, postulated apoptosis dysfunction in the intestine tract related to concurrent respiratory infections [28 ] may account for COVID-19-associated gastrointestinal symptoms.

On the contrary, some COVID-19 patients who resolved SARS-CoV-2 infection in their respiratory tract exhibited the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in their fecal samples, suggesting that the virus replication in the gastrointestinal tract may be independent of the respiratory compartment [11 , 29 , 30 ]. This hypothesis is endorsed by recent studies suggesting that gut involvement in COVID-19 is even more severe and prolonged compared with the respiratory tract [31 ].

Gut microbiome components have significant microbial inhibitory properties toward lung tissues, accomplished through alveolar macrophage, neutrophils, and natural killer cell activity [32 , 33 ]. To a greater extent, bacterial metabolites, as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), are proved to act in the lungs attenuating inflammatory responses. Moreover, some bacterial strains could enhance the release of molecules with antiviral activity like the nuclear factor erythroid 2p45-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and its target Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ].

Although the evidence in COVID-19 is still sparse, bacteriotherapy could represent a potential strategy to counteract SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given the microbiome's crucial role in modulating host immune and inflammatory response, bacteriotherapy may minimize gastrointestinal symptoms and shield the respiratory tract.

Targeting Microbiome to Prevent SARS-CoV-2

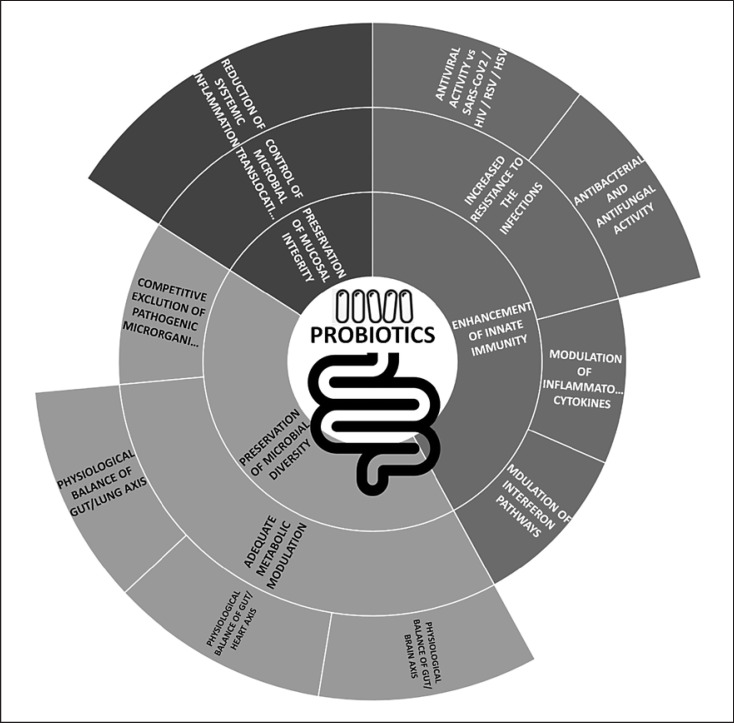

As stated by the WHO, probiotics are “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [39 ]. Historically, the concept of probiotics began around 1,900 by the Nobel laureate Elie Metchnikoff, who discovered that the consumption of live bacteria (Lactobacillus bulgaricus) in yogurt or fermented milk improved some biological features of the gastrointestinal tract [40 ]. Probiotics are now widely available, generally in dairy products, such as yogurt, dessert, ice cream, juices, and capsules, drops, sachets, etc. The most common strains commercially available belong to the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, which proved some beneficial effects to the human body when administered in adequate amounts. These mentioned bacterial species are known to be involved in some essential physiological functions such as stimulation of immune response, prevention of pathogenic and opportunistic microbial colonization, production of SCFA, catabolism of carcinogenic substances, and synthesis of vitamins such as B and K [41 , 42 , 43 ]. In this regard, medical data showed that particular strains of probiotics facilitate the prevention of viral and bacterial infections (such as sepsis, gastroenteritis, and respiratory tract syndrome [4 ]), improve the intestinal epithelial barrier function, and compete with disease-causing agents for nutrients. Similar to other SARS coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 interacts with ACE2 receptor for gut and lung intracellular invasion [2 , 24 ] (Fig. 1 ). For these reasons, some researchers suggested that ACE inhibitors might benefit patients with COVID-19 by reducing pulmonary inflammation [44 ] although others argued that ACE inhibitors might enhance viral entry regulating ACE2 levels.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of action of probiotic supplementation. Legend: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

The potential interaction between probiotics and ACE enzymes was suggested in the previous studies addressing the probiotics' potential antihypertensive effect [45 ]. Indeed, during food fermentation, probiotics release bioactive peptides able to inhibit the ACE enzymes by blocking the active sites [46 , 47 ]. The debris of the dead probiotic cells also acted as ACE inhibitors [48 ].

In this respect, Anwar et al. [49 ] demonstrated in a computational docking study that 3 metabolites of Lactobacillus plantarum (Plantaricin W, Plantaricin JLA-9, and Plantaricin D) prevent the binding of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 receptors suggesting therefore antiviral property of L. plantarum against SARS-CoV-2. Taken all together, these findings stress the assumption that probiotics could compete with ACE2 receptors paving the way for their potential use to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Bacteriotherapy was found to reduce both upper and lower respiratory tract infections [50 ]. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria were administered directly in the respiratory tract or as oral supplements to improve the immune response and ht viral infections [51 ]. As an alternative mechanism of action, probiotics were also found to inhibit viruses by interacting directly with them with a mechanism similar to phagocytosis.

More recently, lactobacilli isolated from healthy human noses showed probiotic effects in the form of nasal spray [52 ], by avoiding the attack of viral particles to mucosal cells. These findings also open the chance to deploy probiotics in a nasal spray to boost the immune system and avoid respiratory tract infections .

To the best of our knowledge, no clinical trial has formally investigated the role of probiotics in preventing COVID-19 so far. However, a multicentric RCT is currently evaluating the effects of a 2-month probiotic supplement on the incidence and severity of COVID-19 among health-care workers exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1 ) [53 ]. The trial was completed in October 2020, and results are expected soon.

Table 1.

Summary of studies and trials addressing the role of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 [54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]

| Reference | Methodology | Primary outcome | Probiotic strains | Probiotic supplementation strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanque [57 ] (NCT04366180) |

RCT, multicenter | Prevention Incidence and severity of SARS- CoV-2 infection in health-care workers | Lactobacillus coryniformis K8 | 3×109 UFC/day Duration: 2 months | Ongoing |

| d'Ettorre et al. [54 ] | Open-label, parallel-group trial, single center | Treatment Comparing respiratory failure incidence and symptoms control | Streptococcus thermophilus DSM 32345, L. acidophilus DSM 32241, L. helveticus DSM 32242, L.paracasei DSM 32243, L. plantarum DSM 32244, L. brevisDSM27961, B. lactis DSM 32246, B. lactis DSM 32247 (Sivomixx®, SivoBiome®) | 2.4×106 UFC/day in 3 equal doses Duration: 14 days |

Probiotic administration is associated with a lower risk of respiratory failure and a faster control of COVID-19-related symptoms (in particular diarrhea) |

| Ceccarelli et al. [55 ] | Retrospective, observational, single center | Treatment Comparing mortality, length of hospitalization, need of intensive care treatment |

Streptococcus thermophilus DSM 32245, Bifidobacterium lactis DSM 32246, Bifidobacterium lactis DSM 32247, L. acidophilus DSM 32241, L. helveticus DSM 32242, L. paracasei DSM 32243, L. plantarum DSM 32244, and L. brevis DSM 27961 (Sivomixx°) |

2.4×106 UFC/day in 3 equal doses Duration: not available |

Oral bacteriotherapy is associated with a lower mortality but a longer length of hospitalization |

| Sung et al. [58 ] (NCT04399252) |

RCT | Basic Science Impact on microbiome in patients that develop COVID-19 |

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 2 caps/day Duration: 28 days | Ongoing |

| Pugliese [56 , 59 ] (NCT04366089) | RCT | Treatment Delta in the number of patients requiring orotracheal intubation despite treatment (ozone therapy- based intervention accompanied by supplementation with probiotics vs. standard of care) |

Streptococcus thermophilus DSM 32245, Bifidobacterium lactis DSM 32246, Bifidobacterium lactis DSM 32247, L. acidophilus DSM 32241, L. helveticus DSM 32242, L. paracasei DSM 32243, L. plantarum DSM 32244, and L. brevis DSM 27961 (Sivomixx°) |

200 billion − 6 sachets twice a day Duration: 7 days | Ongoing |

| Pasquier [60 ] (NCT04621071) | RCT | Treatment Duration of COVID-19 symptoms | Not available | 2 strains 10×109 CFU Duration: 25 days | Ongoing |

| Desrosiers [61 ] (NCT04458519) | RCT | Treatment Change in severity of COVID-19 infection | Nasal irrigations with Lactococcus Lactis W136 (probiorinse) | 2.4 billion CFU Nasal irrigation twice a day Duration: 14 days |

Ongoing |

| Navarro [62 ] (NCT04390477) | RCT | Treatment Percentage of patients with discharge in ICU | Not available | 1×109 CFU/day Duration: 30 days | Ongoing |

| Gea Gonzalez [63 ] (NCT04517422) | RCT | Treatment Severity progression of COVID-19, length of stay at ICU, mortality ratio | L. plantarum CECT7481, L. plantarum CECT7484, L.plantarum CECT7485, and Pediococcus acidilactici CECT7483 | Once a day Duration: 30 days | Ongoing |

| Stadlbauer [64 ] (NCT04420676) |

RCT | Treatment Duration of diarrhea in COVID-19 patients | Bifidobacterium bifdum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Enterococcus faecium W54, L. acidophilus W37, L. acidophilus W55, L. paracasei W20, L.plantarum W1, L. plantarum W62, L. rhamnosus W71, andL. salivarius W24 (Omni-Biotic° 10 AAD) | Twice a day Duration: 30 days | Ongoing |

RCT, randomized controlled study; ICU, intensive care unit; COVID-19; coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

In summary, probiotics may act as antiviral agents interfering with viral entry into cells and/or inhibiting virus replication. This may lead to a limitation in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the gut and respiratory tract, as a result of the restoration of the gut and respiratory microbiota.

Targeting Microbiome to ht SARS-CoV2

Since the gut microbiome is altered in COVID-19 patients [18 ], probiotics supplementation may help restore the gut microbiota and, therefore, maintain a healthy gut-lung axis and minimize translocation of pathogenic bacteria across the gut barrier as well as the chances of secondary bacterial infections. As cytokines storm occurs in patients with severe COVID-19, immune-modulatory effects of probiotics might be relevant to prevent acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ failure, which are life-threatening complications of COVID-19 [54 ].

Boosting immune responses during the incubation and nonsevere stages of COVID-19 infection are perceived as crucial to eliminate the virus and prevent disease progression to severe stages. Administration of certain Bifidobacteria or Lactobacilli has a beneficial impact on influenza virus clearance from the respiratory tract [65 ]. Besides, probiotic strains increase the levels of type I interferons, the number and activity of antigen-presenting cells, NK cells, T cells, and the levels of systemic and mucosal-specific antibodies in the lungs [65 ].

Another relevant effect of probiotics is to enforce and maintain the integrity of tight junctions between enterocytes: Hummel et al. [66 ] showed that gram-positive probiotic lactobacilli modulate epithelial barrier function via their effect on adherence junction protein expression and complex formation [66 ]. Also, incubation with lactobacilli differentially influences the phosphorylation of adherence junction proteins and the abundance of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms such as PKCδ that positively modulates epithelial barrier function.

To this extent, in our previous work, HIV-1-infected patients receiving oral bacteriotherapy exhibited histomorphological and ultrastructural changes in their gut mucosa, characterized by an improvement of epithelial integrity, a reduction of inflammatory infiltrate and enterocyte apoptosis in the terminal ileum, cecum, ascending, transverse, and descending colon [67 ].

Consistent with previous findings, these immunomodulatory benefits seem to be equally crucial in COVID-19 patients. Based on these shreds of evidence, our group addressed the topic over the past year, carrying out 2 retrospective observational studies including adults with severe COVID-19 pneumonia to investigate the role of oral bacteriotherapy on the top of best available therapy [54 , 55 ].

In the first piece of work, we compared respiratory failure incidence and symptoms control in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia receiving a probiotic multistrain formulation (Sivomixx®, SivoBiome®) in adjunction to standard medical therapy [54 ]. Out of 70 patients enrolled in the study, 28 received oral bacteriotherapy for 14 days. According to our results, 92.9% of the intervention group achieved diarrhea and other symptoms control within 72 h from study inclusion (vs. less than half in 7 days in the not supplemented group). Moreover, the risk of developing respiratory failure was 8-fold lower in patients receiving oral bacteriotherapy. Both the prevalence of ICU admission and mortality were lower in the intervention group [54 ].

In the second study, we extended our sample size. We focused our observation on mortality, ICU admission, and length of hospital staying of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia receiving probiotics as complementary therapy [55 ]. Out of 200 patients enrolled, 88 received oral bacteriotherapy (Sivomixx®). Results concerning mortality were quite encouraging: we found a significant reduction in the intervention group (11 vs. 30%; p < 0.001). In addition to that, by multivariate analysis, bacteriotherapy emerged as an independent variable associated with a reduced risk for death. In terms of ICU admission, no significant difference among the 2 groups was found. By contrast, we found a longer length of hospitalization in patients receiving bacteriotherapy. We interpreted this data in line with the lower mortality rate of this group [55 ].

Interestingly, no adverse reactions in patients treated with oral bacteriotherapy were recorded in both studies. In conclusion, for the first time, we determined the role of probiotics in treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, providing positive evidence in favor of their implementation in addition to the best available therapy. To the best of our knowledge, 7 RCTs that may soon replicate this insight are currently ongoing (Table 1 ).

The New Frontier: Are Distinct Microbiome Patterns Associated with Different Risks of COVID-19 Progression?

Several studies showed that dietary habits and the amount of food consumed could shape human microbiome [68 ]. Diet in developing countries usually consists of food containing more fiber than a modern Western diet consisting of food often processed and kept in cold storage [69 ]. It is now well reckoned that different populations with different diets could have distinct microbiome patterns. Generally, Firmicutes are dominant in people with animal-based diets, whereas Bacteroidetes are dominant in people with a vegetarian diet [70 ]. Similarly, molecules involved in the digestion of fiber and concentration of SCFAs are differently represented in the microbiome of populations with different diets [71 , 72 ]. Interestingly, a plant food-based diet maintains a more stable microbiota diversity and eubiosis and promotes the microbes that ensue anti-inflammatory response [73 ]. Preliminary reports suggested that different progression rates to severe disease and fatality rates observed for SARS-CoV-2 in diverse populations could be related to distinct microbiome patterns. For example, it was observed that India reported a fatality rate caused by SARS-CoV-2 lower if compared to other regions consuming meat-rich diet and saturated fatty acids, such as the USA, Brazil, and European countries [74 ]. Currently, it is not possible to strongly support this hypothesis, but nevertheless, it could be a clue to understand the variations observed in the impact of COVID-19 in populations residing in different geographical areas.

Expert Opinion

Probiotics may play a beneficial role even though there is much to be discovered on their specific mechanisms of action against SARS-CoV-2. The damage of the gut barrier integrity associated with microbial translocation along with the dysregulated inflammatory response explains why probiotics could represent a valuable therapeutic tool in COVID-19 patients [56 , 69 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 ].

However, clinicians should be mindful that probiotics' clinical benefit depends upon several factors, such as the bacterial composition of different commercial products, manufacturing processes, dose regimen, etc. Several studies had addressed the impact of probiotics in treating many gastrointestinal disorders, such as Clostridium difficile colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, etc. [70 , 71 ]. Moreover, in recent studies, probiotics were found to restore gut barrier integrity and, therefore, the gut-brain axis in HIV patients [72 ]. In conclusion, further understanding of gut microbiome modulation on host health is expected to expand probiotic clinical applications soon.

Conclusion

The “gut-lung axis” pathophysiology suggests that the intestinal microbiota may play a role in counteracting the “cytokine storm,” which is now clearly being the cornerstone of COVID-19 disease [80 ]. Even though evidence coming from clinical trials is still on the way, we showed for the first time a consistent reduction in mortality and more successful symptoms control in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia receiving oral bacteriotherapy as a complementary therapy.

Therefore, we suggest physicians consider the early administration of oral bacteriotherapy on the top of best available treatment while dealing with patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, especially in those experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms. This alternative option has multiple advantages, indeed: it is mostly freely available, cheap, and with limited/no adverse effects.

Statement of Ethics

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

All the authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any financial support (funding, grants, and sponsorship) to be acknowledged.

Author Contributions

All the authors equally contributed to the literature search and manuscript drafting.

References

- 1.The WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically Ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324((13)):1330–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181((2)):271–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhar D, Mohanty A. Gut microbiota and Covid-19- possible link and implications. Virus Res. 2020;285:198018. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin L, Jiang X, Zhang Z, Huang S, Zhang Z, Fang Z, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69((6)):997–1001. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effenberger M, Grabherr F, Mayr L, Schwaerzler J, Nairz M, Seifert M, et al. Faecal calprotectin indicates intestinal inflammation in COVID-19. Gut. 2020 Aug;69((8)):1543–4. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Kang Z, Gong H, Xu D, Wang J, Li Z, et al. Digestive system is a potential route of COVID-19: an analysis of single-cell co-expression pattern of key proteins in viral entry process. Gut. 2020;69:1010–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad MAK, Sarker M, Wan D. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics on cytokine profiles. Biomed Res Int. 2018;23:8063647. doi: 10.1155/2018/8063647. PMID: 30426014; PMCID: PMC6218795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cholankeril G, Podboy A, Aivaliotis VI, Tarlow B, Pham EA, Spencer S, et al. High prevalence of concurrent gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with SARS-CoV-2: early experience from California. Gastroenterology. 2020 Aug;159((2)):775–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.008. S0016–5085(20)30471-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York city. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 11;382((24)):2372–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158((6)):1831–e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanz Segura P, Arguedas Lázaro Y, Mostacero Tapia S, Cabrera Chaves T, Sebastián Domingo JJ. Involvement of the digestive system in covid-19. A review. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43((8)):464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perlot T, Penninger JM. ACE2: from the renin-angiotensin system to gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microbes Infect. 2013;15((13)):866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camargo SM, Singer D, Makrides V, Huggel K, Pos KM, Wagner CA, et al. Tissue-specific amino acid transporter partners ACE2 and collectrin differentially interact with hartnup mutations. Gastroenterology. 2009;136((3)):872–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto T, Perlot T, Rehman A, Trichereau J, Ishiguro H, Paolino M, et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487((7408)):477–81. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceccarelli G, Scagnolari C, Pugliese F, Mastroianni CM, d'Ettorre G. Probiotics and COVID-19. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Aug;5((8)):721–2. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30196-5. Published online 2020 Jul 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giron LB, Dweep H, Yin X, Wang H, Damra M, Goldman AR, et al. Severe COVID-19 is fueled by disrupted gut barrier integrity. medRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baud D, Dimopoulou Agri V, Gibson GR, Reid G, Giannoni E. Using probiotics to flatten the curve of coronavirus disease COVID-2019 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:186. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobel YR, Phipps M, Zucker J, Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Sobieszczyk ME, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and COVID-19: case-control study from the United States. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159((1)):373–5.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pouya F, Imani Saber Z, Kerachian MA. Molecular aspects of co-morbidities in COVID-19 infection. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020 Apr;8((Suppl 1)):226–30. doi: 10.22038/abjs.2020.47828.2361. PMID: 32607393; PMCID: PMC7296607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y, Wen Q, Yao F, Xu D, Huang Y, Wang J. Gut-lung axis: the microbial contributions and clinical implications. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2017;43((1)):81–95. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1176988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shukla SD, Budden KF, Neal R, Hansbro PM. Microbiome effects on immunity, health and disease in the lung. Clin Transl Immunol. 2017;6((3)):e133. doi: 10.1038/cti.2017.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tulic MK, Piche T, Verhasselt V. Lunggut cross-talk: evidence, mechanisms and implications for the mucosal inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:519–28. doi: 10.1111/cea.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li N, Ma WT, Pang M, Fan QL, Hua JL. The commensal microbiota and viral infection: a comprehensive review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1551. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingula R, Filaire M, Radosevic-Robin N, Bey M, Berthon JY, Bernalier-Donadille A, et al. Desired turbulence? Gut-lung axis, immunity, and lung cancer. J Oncol. 2017;2017:5035371. doi: 10.1155/2017/5035371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAleer JP, Kolls JK. Contributions of the intestinal microbiome in lung immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48((1)):39–49. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, Ngom-Bru C, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2014;20((2)):159–66. doi: 10.1038/nm.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrone EE, Jung E, Breed E, Dominguez JA, Liang Z, Clark AT, et al. Mechanisms of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus pneumonia-induced intestinal epithelial apoptosis. Shock. 2012 Jul;38((1)):68–75. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318259abdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopel J, Perisetti A, Gajendran M, Boregowda U, Goyal H. Clinical insights into the gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65((7)):1932–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, Hong Z, Zhou J, Dong X, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5((5)):434–5. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8((4)):420–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. HTTPS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vieira AT, Rocha VM, Tavares L, Garcia CC, Teixeira MM, Oliveira SC, et al. Control of Klebsiella pneumoniae pulmonar y infection and immunomodulation by oral treatment with the commensal probiotic Bifidobacterium longum 5(1A) Microbes Infect. 2016;18:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belkacem N, Serafini N, Wheeler R, Derrien M, Boucinha L, Couesnon A, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei feeding improves immune control of influenza infection in mice. PLoS One. 2017;12((9)):e0184976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devadas K, Dhawan S. Hemin activation ameliorates HIV-1 infection via heme oxygenase-1 induction. J Immunol. 2006;176((7)):4252–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashiba T, Suzuki M, Nagashima Y, Suzuki S, Inoue S, Tsuburai T, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of heme oxygenase-1 cDNA attenuates severe lung injury induced by the influenza virus in mice. Gene Ther. 2001;8((19)):1499–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espinoza JA, León MA, Céspedes PF, Gómez RS, Canedo-Marroquín G, Riquelme SA, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 modulates human respiratory syncytial virus replication and lung pathogenesis during infection. J Immunol. 2017;199((1)):212–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tseng CK, Lin CK, Wu YH, Chen YH, Chen WC, Young KC, et al. Human heme oxygenase 1 is a potential host cell factor against dengue virus replication. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32176. doi: 10.1038/srep32176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hill-Batorski L, Halfmann P, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. The cytoprotective enzyme heme oxygenase-1 suppresses Ebola virus replication. J Virol. 2013;87((24)):13795–802. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02422-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines . Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. London, ON: 2002. p. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benton D, Williams C, Brown A. Impact of consuming a milk drink containing a probiotic on mood and cognition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007 Mar;61((3)):355–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602546. Epub 2006 Dec 6. PMID: 17151594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logan AC, Venket Rao A, Irani D. Chronic fatigue syndrome: lactic acid bacteria may be of therapeutic value. Med Hypotheses. 2003;60((6)):915–23. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams B, Landay A, Presti RM. Microbiome alterations in HIV infection a review. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18((5)):645–51. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceccarelli G, Statzu M, Santinelli L, Pinacchio C, Bitossi C, Cavallari EN, et al. Challenges in the management of HIV infection: update on the role of probiotic supplementation as a possible complementary therapeutic strategy for cART treated people living with HIV/AIDS. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019 Sep;19((9)):949–65. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1638907. Epub 2019 Jul 10. PMID: 31260331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J, He X, Ou M, Bi J, et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9((1)):757–60. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1746200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robles-Vera I, Toral M, Romero M, Jiménez R, Sánchez M, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, et al. Antihypertensive effects of probiotics. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017 Apr;19((4)):26. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayyash MM, Sherkat F, Shah NP. The effect of NaCl substitution with KCl on Akawi cheese: chemical composition, proteolysis, angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitory activity, probiotic survival, texture profile, and sensory properties. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95((9)):4747–59. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayyash M, Olaimat A, Al-Nabulsi A, Liu SQ. Bioactive properties of novel probiotic lactococcus lactis fermented camel sausages: cytotoxicity, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition, antioxidant capacity, and antidiabetic activity. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2020;40:155–71. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2020.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miremadi F, Ayyash M, Sherkat F, Stojanovska L. Cholesterol reduction mechanisms and fatty acid composition of cellular membranes of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. J Funct Foods. 2014;9:295–305. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anwar F, Altayb HN, Al-Abbasi FA, Al-Malki AL, Kamal MA, Kumar V. Antiviral effects of probiotic metabolites on COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1775123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell K. How some probiotic scientists are working to address COVID-19. 2020. Available from: https://isappscience.org/tag/covid-19/ Accessed 2020 May 04.

- 51.Barbieri N, Herrera M, Salva S, Villena J, Alvarez S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus CRL1505 nasal administration improves recovery of T-cell mediated immunity against pneumococcal infection. 2017 doi: 10.3920/BM2016.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Boeck I, van den Broek MFL, Allonsius CN, Martens K, Wuyts S, Wittouck S, et al. Lactobacilli have a niche in the human nose. SSRN Electron J. 2019;31:107674. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evaluation of the probiotic lactobacillus coryniformis K8 on COVID-19 prevention in healthcare workers. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04366180 [last access 4 Jan 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04366180.

- 54.d'Ettorre G, Ceccarelli G, Marazzato M, Campagna G, Pinacchio C, Alessandri F, et al. Challenges in the management of SARS-CoV2 infection: the role of oral bacteriotherapy as complementary therapeutic strategy to avoid the progression of COVID-19. Front Med. 2020;7:389. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ceccarelli G, Borrazzo C, Pinacchio C, Santinelli L, Innocenti GP, Cavallari EN, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy in patients with COVID-19: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Nutr. 2020;7:613928. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.613928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araimo F, Imperiale C, Tordiglione P, Ceccarelli G, Borrazzo C, Alessandri F, et al. Ozone as adjuvant support in the treatment of COVID-19: a preliminary report of probiozovid trial. J Med Virol. 2020 Oct 28; doi: 10.1002/jmv.26636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanque RR. Evaluation of the Probiotic Lactobacillus Coryniformis K8 on COVID-19 Prevention in Healthcare Workers. [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04366180.

- 58.Sung A, Wischmeyer P. Effect of Lactobacillus on the Microbiome of Household Contacts Exposed to COVID-19. [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04399252.

- 59.Pugliese F. Oxygen-Ozone as Adjuvant Treatment in Early Control of COVID-19 Progression and Modulation of the Gut Microbial Flora (PROBIOZOVID) [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04366089.

- 60.Pasquier JC. Efficacy of Probiotics in Reducing Duration and Symptoms of COVID-19 (PROVID-19) [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04621071.

- 61.Desrosiers MY. Efficacy of Intranasal Probiotic Treatment to Reduce Severity of Symptoms in COVID19 Infection. [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04458519.

- 62.Navarro L. Study to Evaluate the Effect of a Probiotic in COVID-19. [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04390477.

- 63.Gea Gonzalez M. Efficacy of L. Plantarum and P. Acidilactici in Adults With SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04517422.

- 64.Stadlbauer V. Synbiotic Therapy of Gastrointestinal Symptoms During Covid-19 Infection (SynCov) [last access 18 March 2021]. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04420676.

- 65.Zelaya H, Alvarez S, Kitazawa H, Villena J. Respiratory antiviral immunity and immunobiotics: beneficial effects on inflammation-coagulation interaction during influenza virus infection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:633. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hummel S, Veltman K, Cichon C, Sonnenborn U, Schmidt MA. Differential targeting of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex by gram-positive probiotic lactobacilli improves epithelial barrier function. Appl Environ Microbiol. Jan 2012;78((4)):1140–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06983-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.d'Ettorre G, Rossi G, Scagnolari C, Andreotti M, Giustini N, Serafino S, et al. Probiotic supplementation promotes a reduction in T-cell activation, an increase in Th17 frequencies, and a recovery of intestinal epithelium integrity and mitochondrial morphology in ART-treated HIV-1-positive patients. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2017;5((3)):244–60. doi: 10.1002/iid3.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rishi P, Thakur K, Vij S, Rishi L, Singh A, Kaur IP, et al. Diet, gut microbiota and COVID-19. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60((4)):420–9. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00908-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Narayanan S, Pitchumoni CS. Dietary fiber. In: Pitchumoni C, Dharmarajan T, editors. Geriatric gastroenterology. Cham: Springer; 2020. pp. p. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Senghor B, Sokhna C, Ruimy R, Lagier JC. Gut microbiota diversity according to dietary habits and geographical provenance. Hum Microbiome J. 2018;7–8:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Filippo C, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Albanese D, Pieraccini G, Banci E, et al. Diet, environments, and gut microbiota. A preliminary investigation in children living in rural and urban Burkina Faso and Italy. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1979. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maslowski KM, Mackay CR. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12((1)):5–9. doi: 10.1038/ni0111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tomova A, Bukovsky I, Rembert E, Yonas W, Alwarith J, Barnard ND, et al. The effects of vegetarian and vegan diets on gut microbiota. Front Nutr. 2019;6:47. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report-132. 2020:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marazzato M, Ceccarelli G, d'Ettorre G. Dysbiosis in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Gastroenterology. 2020 Dec 30;S0016–5085((20)):35618–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kukla M, Adrych K, Dobrowolska A, Mach T, Reguła J, Rydzewska G. Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults. Prz Gastroenterol. 2020;15((1)):1–21. doi: 10.5114/pg.2020.93629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, et al. British Society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019 Dec;68((Suppl 3)):s1–s106. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landi C, Santinelli L, Bianchi L, Shaba E, Ceccarelli G, Cavallari EN, et al. Cognitive impairment and CSF proteome modification after oral bacteriotherapy in HIV patients. J Neurovirol. 2020 Feb;26((1)):95–106. doi: 10.1007/s13365-019-00801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Infusino F, Marazzato M, Mancone M, Fedele F, Mastroianni CM, Severino P, et al. Diet supplementation, probiotics, and nutraceuticals in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 8;12((6)):1718. doi: 10.3390/nu12061718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vangay P, Johnson AJ, Ward TL, Al-Ghalith GA, Shields-Cutler RR, Hillmann BM, et al. US immigration westernizes the human gut microbiome. Cell. 2018;175((4)):962–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]