Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations are causing ocean acidification with significant consequences for marine organisms. Chain-forming centric diatoms of Skeletonema is one of the most successful groups of eukaryotic primary producers with widespread geographic distribution.

KEYWORDS: metabolism, ocean acidification, proteomics, RNA-seq, Skeletonema marinoi

ABSTRACT

Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations are causing ocean acidification (OA) with significant consequences for marine organisms. Because CO2 is essential for photosynthesis, the effect of elevated CO2 on phytoplankton is more complex, and the mechanism is poorly understood. Here, we applied transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) and iTRAQ proteomics to investigate the impacts of CO2 increase (from ca. 400 to 1,000 ppm) on the temperate coastal marine diatom Skeletonema marinoi. We identified 32,389 differentially expressed genes and 1,826 differentially expressed proteins from conditions where the CO2 is elevated, accounting for 48.5% of the total genes and 25.9% of the total proteins we detected, respectively. Elevated partial CO2 pressure (pCO2) significantly inhibited the growth of S. marinoi, and the “omic” data suggested that this might be due to compromised photosynthesis in the chloroplast and raised mitochondrial energy metabolism. Furthermore, many genes/proteins associated with nitrogen metabolism, transcriptional regulation, and translational regulation were markedly upregulated, suggesting enhanced protein synthesis. In addition, S. marinoi exhibited higher capacity of reactive oxygen species production and resistance to oxidative stress. Overall, elevated pCO2 seems to repress photosynthesis and growth of S. marinoi and, through massive gene expression reconfiguration, induce cells to increase investment in protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and antioxidative stress defense, likely to maintain pH homeostasis and population survival. This survival strategy may deprive this usually dominant diatom in temperate coastal waters of its competitive advantages in acidified environments.

IMPORTANCE Rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations are causing ocean acidification with significant consequences for marine organisms. Chain-forming centric diatoms of Skeletonema is one of the most successful groups of eukaryotic primary producers with widespread geographic distribution. Among the recognized 28 species, Skeletonema marinoi can be a useful model for investigating the ecological, genetic, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of diatoms in temperate coastal regions. In this study, we found that the elevated pCO2 level seems to repress photosynthesis and growth of S. marinoi and, through massive gene expression reconfiguration, induce cells to increase investment in protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and antioxidative stress defense, likely to maintain pH homeostasis and population survival. This survival strategy may deprive this usually dominant diatom in temperate coastal waters of its competitive advantages in acidified environments.

INTRODUCTION

Since industrialization, anthropogenic CO2 has been quickly accumulating in the atmosphere, resulting in global warming and ocean acidification. It is estimated that atmospheric CO2 will rise from the current level of 400 to 1,000 ppm by the end of this century (1). As the surface seawater absorbs additional atmospheric CO2, perturbing ocean carbonate buffering system, the consequent decreased pH can have profound effects on primary producers, as well as other organisms in the ocean (2). However, it is still a controversial issue how ocean acidification will change marine phytoplankton community structure and productivity because the combined effect of elevated CO2 and decreased pH can vary between species. Diatoms are a major group of primary producers in the ocean, which contribute ∼40% of the annual marine primary productivity (3) and exhibit higher carbon sequestration into the deep sea because their silica frustules improve their sinking rates (4). The effects of ocean acidification on diatoms can have significant biogeochemical impacts. Diatoms’ responses to rising partial CO2 pressure (pCO2) and dropping pH are species specific, with potential winners, neutrals, and losers among the species (5–8). For instance, elevated pCO2 had insignificant effects on the growth, photosynthesis, dark respiration, particulate organic carbon, and particulate organic nitrogen of diatom Skeletonema pseudocostatum (9). Under higher pCO2, CO2-driven acidification decreased the productivity of Thalassiosira pseudonana by increasing dark respiration (10). In contrast, rising temperature and CO2 (25°C, 1,000 ppm) caused increases in the growth rate, pigment composition, and biochemical productivity of Skeletonema dohrnii (11).

The effects of elevated CO2 on phytoplankton are more complex than on animals, because higher CO2 without considering acidification are favorable to photosynthesis. Normally, diatom species rely on CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) to obtain sufficient CO2 for Rubisco, the enzyme that fixes CO2 (12, 13). Generally, diatoms downregulate their CCMs under enhanced pCO2 (14), potentially saving energy required by CCMs. Decreased pH, in contrast, could disturb cell surface and intracellular pH stability, so that diatom cells (as well as animals) require additional energy to maintain pH homeostasis (5, 15). Moreover, rising CO2 can have broader metabolic effects, leading to changes in biochemical composition of diatom cells, for instance, the levels of pigments, fatty acids, lipids, amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, particulate organic carbon, and particulate organic nitrogen (9, 11, 16). These changes will occur through transcriptional and translational regulation.

Chain-forming centric diatoms of Skeletonema is one of the most successful groups of eukaryotic primary producers with widespread geographic distribution (9, 17, 18). Among the recognized 28 species, S. marinoi can be a useful model for investigating the ecological, genetic, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of diatoms in temperate coastal regions (19). It is not only an important primary producer for the higher trophic levels but also contributes significantly to harmful algal blooms in spring (17). In addition, S. marinoi plays an important role in the sequestration and mineralization of carbon, silicon, phosphorus, and nitrogen in the marine biogeochemical cycle (20). To gain understanding on how this species will respond to increasing CO2, we performed transcriptome and proteome analyses on S. marinoi growing under an elevated CO2 condition. Our results provide insights into potential ecological consequences to this and other related diatoms of increasing CO2 in future oceans.

RESULTS

Skeletonema marinoi growth and pH trends.

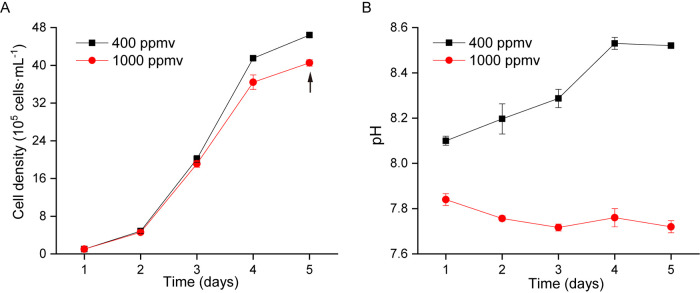

During the 5-day experimental period, the similar growth trends were observed for ambient CO2 and elevated CO2 treatment groups with maximum cell density at (4.64 ± 0.03) × 106 and (4.05 ± 0.07) × 106 cells ml−1 (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 1A). Under bubbling with ambient CO2, S. marinoi achieved an intrinsic growth rate (µ) of 0.96 ± 0.002 day−1, while bubbling with elevated CO2 significantly inhibited the cell growth and decreased growth rate to 0.92 ± 0.004 day−1 (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.01). The highest growth rate in both groups occurred on the first day, at 1.57 ± 0.02 day−1 (ambient pCO2) and 1.52 ± 0.08 day−1 (elevated pCO2), respectively (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). We noticed that the pH fluctuations in the treatment of ambient CO2 and elevated CO2 were different. As the cell density increased, pH values under ambient CO2 gradually rose from day 1 to day 5, while the pH under elevated CO2 showed a slight decrease during this period (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Time courses for S. marinoi cell density (105 cells ml−1) and pH values. An arrow indicates when samples were collected for “omic” analyses.

Transcriptome assembly, annotation, and protein identification.

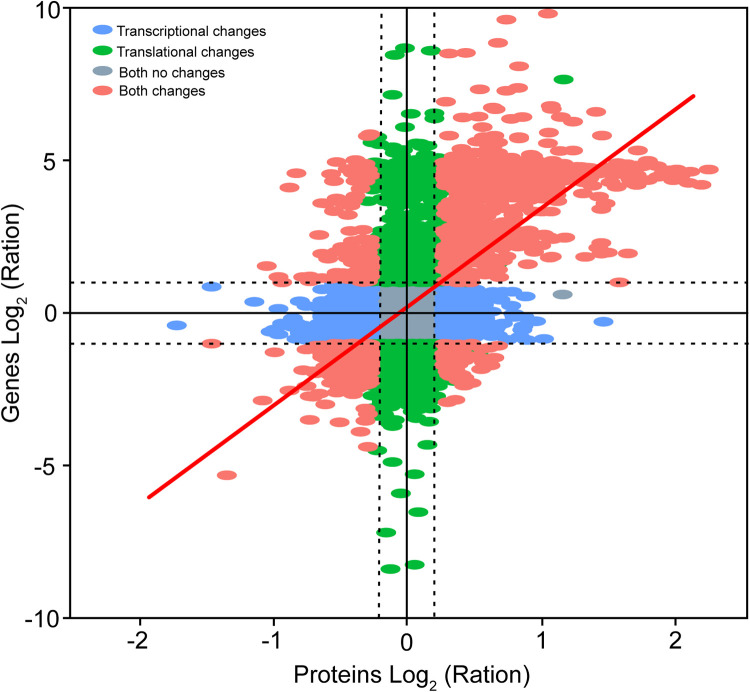

After quality filtering for raw reads, more than 44.5 M clean transcript reads were obtained from each sample. Approximately 84% of clean transcript reads found matches in the reference databases. On average, 38.5 and 46.5% uniquely mapping reads were generated in the ambient CO2 group and elevated CO2 group, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In the transcriptome analysis, we achieved 66,873 unigenes with 25,441 upregulated genes and 6,948 downregulated genes. Simultaneously, iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics yielded 32,965 peptides and 7,055 proteins with 1,246 upregulated proteins and 580 downregulated proteins. In total, 6,831 gene transcripts were correlated with their corresponding proteins. Among them, 1,107 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs; upregulated, n = 938; downregulated, n = 169) exhibited the same differential expression trends between normal and elevated CO2 conditions (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Overview of transcriptomic and proteomic profilesa

| Elevated vs ambient | Total no. | No. upregulated | No. downregulated | Total no. regulated (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unigenes | 66,783 | 25,441 | 6,948 | 32,389 (48.5) |

| Proteins | 7,055 | 1,246 | 580 | 1,826 (25.9) |

| No. of correlations | 6,831 | 938 | 169 | 1,107 (16.2) |

That is, the number of correlations is the number of proteins mapped to unigenes.

FIG 2.

Correlation of differential transcriptional and translational expression of genes between normal and elevated CO2 treatments.

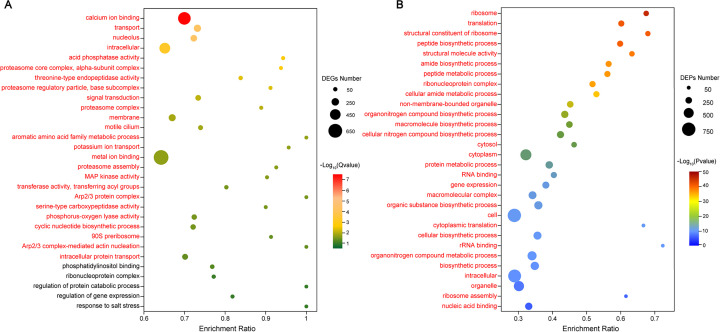

The number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and DEPs assigned to Gene Ontology (GO) terms were 13,739 and 1,326, which accounted for 20.6% of total detected genes and 18.8% of total detected proteins, respectively. The DEGs were defined and described by GO functional enrichment analysis, and 25 significantly enriched GO terms (Q value < 0.05) were identified in our transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) data. For instance, calcium ion binding, potassium ion transport, metal ion binding, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activity, Arp2/3 protein complex, and phosphorus-oxygen lyase activity were strongly regulated at the mRNA level (Fig. 3A). According to our iTRAQ data, 207 enriched GO terms (P < 0.05) were identified, showing that the elevated CO2 group exhibited enrichment of ribosome, translation, cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process, protein metabolic process, gene expression, nucleic acid binding, among others (Fig. 3B; see Table S2). Interestingly, only three significantly enriched GO terms were found in both our RNA-seq and iTRAQ data, including intracellular, motile cilium, and MAP kinase activity (Fig. 3A and B; see Table S2).

FIG 3.

Top 30 ranking GO terms found in the transcriptome in the proteomic analysis. (A) Top 30 ranking GO terms found in the transcriptome. Red text indicates significantly enriched GO terms (Q value < 0.05), and the color strength represents the Q value. (B) Top 30 ranking GO terms found in the proteome. Red text indicates significantly enriched GO terms (P < 0.05), and the color strength represents the P value.

To determine the overall functional distribution of DEGs/DEPs in the two CO2 treatment groups, reads were subjected to KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers, and a total of 9,057 DEGs and 788 DEPs were identified. We also performed a functional enrichment analysis for DEGs and DEPs through the KEGG pathway, finding that only RNA transport was enriched in both RNA-seq and iTRAQ data. Besides, 13 pathways (Q value < 0.05) were also enriched by annotated DEGs, including proteasome, nucleotide excision repair, sphingolipid metabolism, tryptophan metabolism, galactose metabolism, carbon metabolism, etc. (Fig. 4). A total of 11 significantly enriched KEGG pathways (P < 0.05) were identified in our iTRAQ data, and these pathways were ribosome, citrate cycle (tricarboxylic acid [TCA] cycle), aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, phagosome, N-glycan biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism, among others (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Significant KEGG enrichment pathways either in the transcriptomic (Q value < 0.05) or in the proteomic analysis (P < 0.05). Circle color strength represents the Q or P value, whereas the circle size indicates the enrichment magnitude. The font color of the process names on the left shows that either the transcriptional level, the translational level, or both levels are significant.

Nitrogen metabolism and transporter of nutrients.

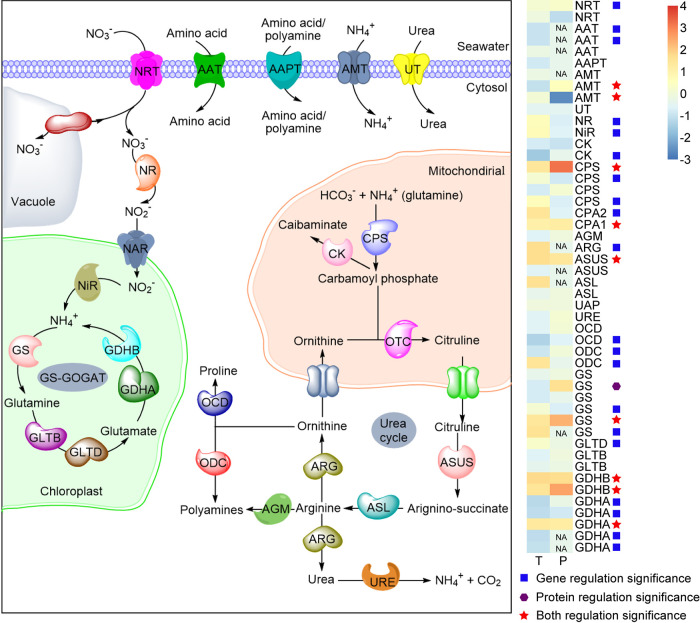

In total, 48 nitrogen metabolism associated genes were identified from our transcriptomic data, among which 30 showed differential expression. Most of DEGs were upregulated, including genes involved in N transport and assimilation, with the exception of a few genes involved in amino acid transport, urea cycle (OUC), and glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase (GS-GOGAT) that were downregulated under elevated pCO2 (Fig. 5; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Form our proteomic data, 36 proteins were associated with nitrogen metabolism, and 11 of them showed strong regulation. Except for one ammonium transporter (AMT), the remaining 10 DEPs, which functioned in N transport, OUC, and GS-GOGAT, were all upregulated under elevated pCO2 (Fig. 5; see also Table S3).

FIG 5.

Transcript and protein levels of genes encoding components of the nitrogen metabolism pathway in S. marinoi. The heatmap on the right shows changes in the expression levels of genes or proteins involved in nitrogen metabolism. The color strength represents homogenized gene or protein expression values (log2-fold change) on a column z-score, increasing from blue (lowest) to red (highest). T, transcript; P, protein; NRT, nitrate transporter; AAPT, amino acid/polyamine transporter; AAT, amino acid transporter; AMT, ammonium transporter; UT, urea transporter; NR, nitrate reductase; NiR, nitrite reductase (ferredoxin); CK, carbamate kinase; CPS, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase; CPA2, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large subunit; CPA1, carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small subunit; AGM, agmatinase; ARG, arginase; ASUS, argininosuccinate synthase; ASL, argininosuccinate lyase; UAP, urease accessory protein; URE, urease; OCD, ornithine cyclodeaminase; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; GS, glutamine synthetase; GLTD, glutamate synthase (ferredoxin); GLTB, glutamate synthase (NADPH/NADH); GDHB, glutamate dehydrogenase [NAD(P)+]; GDHA, glutamate dehydrogenase (NADP+); GS-GOGAT, glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase; NA, not available.

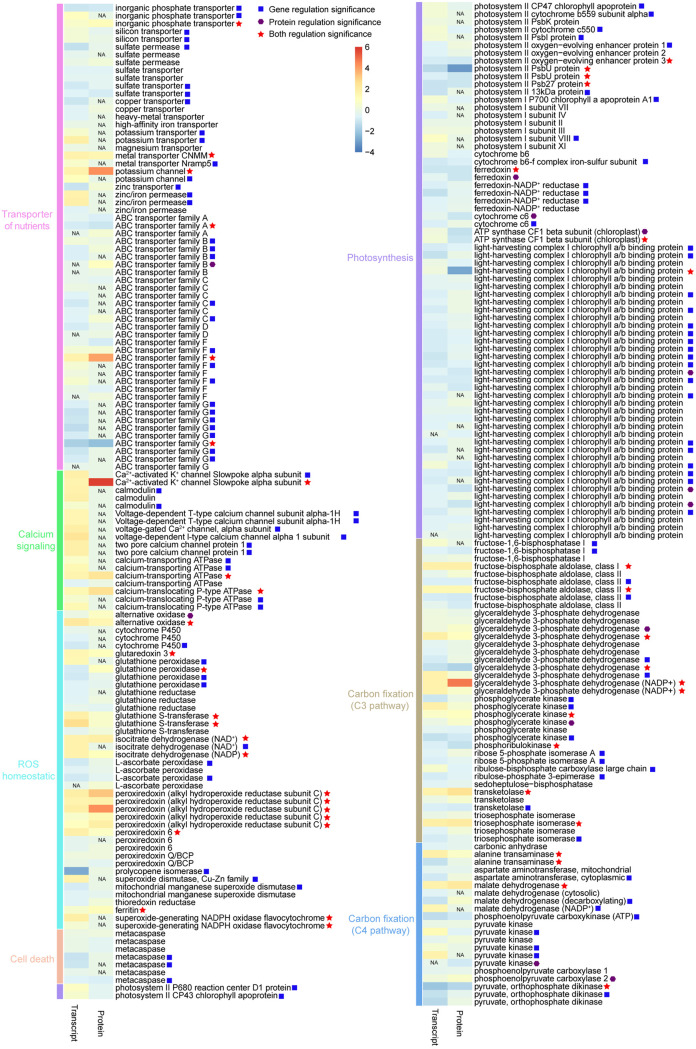

In addition to N-related transport genes, we also identified other 65 transport-related genes from our transcriptomic data, among which 47 were differentially expressed, including 27 upregulated and 20 downregulated (Fig. 6; see also Table S3). For example, two inorganic phosphate transporter (PiT), Ca2+-activated K+ channel slowpoke alpha subunit (KV,Ca), metal transporter CNMM (CNMM), potassium channel (K channel), and ABC transporter F family were upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition. In contrast, one PiT, copper transporter (COT), sulfate permease (SUP), sulfate transporter (SUT), zinc transporter (ZiT), and ABC transporter A/C/D/G families were downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition. In our proteomic data set, we detected 36 proteins associated with nutrient transport (except nitrogen), among which 6 were upregulated and 2 were downregulated (Fig. 6; see also Table S3). The abundance of KV,Ca, PiT, CNMM, K channel, and ABC transporter B/F family proteins significantly increased under the elevated CO2 condition, while the abundance of ABC transporter A/G family proteins significantly decreased under the elevated CO2 condition.

FIG 6.

Heatmap showing changes in expression levels of genes or proteins involved in the transport of nutrients, calcium signaling, ROS homeostasis, cell death, photosynthesis, and carbon fixation. The color scale represents normalized gene or protein expression values (log2-fold change) on a column z-score, increasing from blue (lowest) to red (highest). NA, not available.

Photosynthesis, electron transport chain, and carbon fixation.

In search of DEGs/DEPs involved in photosynthesis, we found that 19 light-harvesting complex II chlorophyll a/b binding (Lhca) genes (2 upregulated, 17 downregulated) and 3 Lhca proteins (downregulated) showed strong regulation under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S4). All the photosystem II reaction center (PSII RC) genes (PsbA, PsbB, PsbC, and PsbE) identified in our RNA-seq data were upregulated, but this was not reflected in our iTRAQ data (Fig. 6; see Table S4). However, both transcriptome and proteome data indicated that the oxygen evolving complex (OEC) was downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S4). This would strongly suggest accumulation of unassembled PSII repair cycle intermediates, because it is not possible to assemble a complete PSII without the oxygen-evolving complex. Form the core of the photosystem I (PSI) complex, PsaA genes were upregulated transcriptionally but not so from the proteomic data set (Fig. 3; see also Table S4).

In search of DEGs associated with photosynthesis electron transport, we observed significantly increased expression of PSI RC, PSII RC, and ATP synthase (chloroplast) and decreased expression of cytochrome b6-f complex iron-sulfur subunit (petC), cytochrome c6 (Cytc6), ferredoxin (Fd), and ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR) (Fig. 6; see Table S4). All DEPs involved in photosynthesis electron transport showed significant downregulation, including Fd, Cytc6, and ATP synthase (chloroplast) proteins (Fig. 6; see Table S4). In addition, genes/proteins associated with C3 and C4 photosynthesis were also identified in our study, and some of them were statistically significant. Notably, proteins encoding ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase large chain (RBCL), carbonic anhydrase (CA), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 1 (PEPC1), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) all displayed weak downregulation (not significant) (Fig. 6; see Table S4).

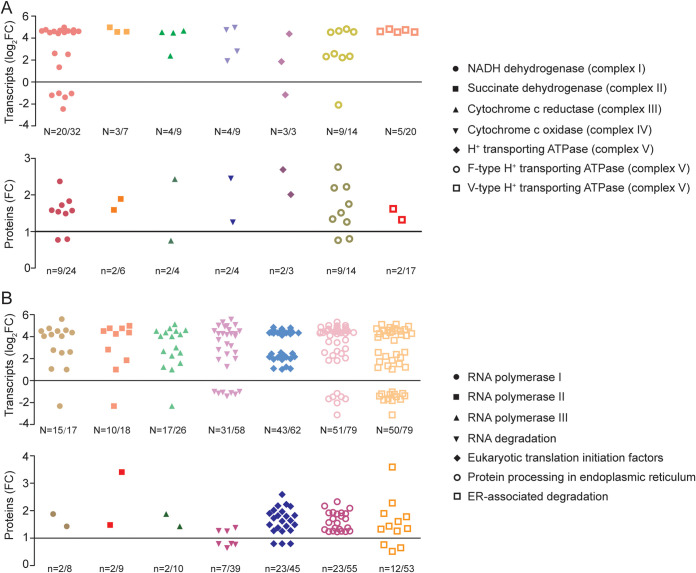

In both our RNA-seq and proteomic data sets, many genes/proteins involved in mitochondrial electron transport chain were upregulated (Fig. 7A; see Table S5), indicating that the electron transfer in the mitochondria was enhanced under the elevated CO2 condition. Notably, complex V (ATP synthase) couples the transfers of electron back into the matrix to produce ATP by oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). We observed that OA-driven upregulation of the ATP synthase associated with OXPHOS, including H+-transporting ATPase, F-type H+-transporting ATPase, V-type H+-transporting ATPase (Fig. 7A; see Table S5). These results suggested that ATP synthesis in mitochondria was promoted under the elevated CO2 condition.

FIG 7.

Significant expression changes of genes or proteins under the elevated CO2 condition. (A) Summary of differentially expressed genes or proteins (DEGs/DEPs) involved in oxidative phosphorylation. (B) Summary of DEGs/DEPs involved in RNA polymerases I, II, and III, RNA degradation, eukaryotic translation initiation factors, protein processing in the ER, and ER-associated degradation. N, total DEGs number/total gene number; n, total DEPs number/total protein number. Detailed information is available in Tables S5 and S6.

RNA and protein syntheses and processing.

RNA-seq analysis indicated that 15 genes encoding RNA polymerase I (Pol I), 10 genes associated with Pol II, and 17 genes related to Pol III were differentially expressed under the elevated CO2 condition. except for one RPABC5 gene, all the DEGs were all significantly upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). This upregulation trend was reflected in the proteomic data set, specifically for RPB1, RPB3, RPAC1, and RPAC2 proteins (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). These results suggested that RNA synthesis was enhanced under the elevated CO2 condition.

In this study, 31 genes [e.g., 5′-3′ exoribonuclease, poly(A)-specific RNase mRNA-decapping enzyme, mRNA-decapping enzyme 1B] associated with RNA degradation were found to significantly change expression under the elevated CO2 condition. Most of them were upregulated, indicating upregulation of the cellular RNA degradation (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). Differential expression analysis indicated that seven DEPs involved in RNA degradation. Of these, three DEPs were upregulated, while other four DEPs were down-regulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 7B; see Table S6).

In the protein synthesis machinery, we identified 62 genes associated with eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIFs). Among them, 43 eIF genes were found to significantly change expression under the elevated CO2 condition, and all these DEGs were upregulated (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). Besides, our iTRAQ data revealed a set of 23 DEPs associated with eIFs, 20 of which were remarkably upregulated, such as translation initiation factor 1 (eIF1) and two translation initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). In addition, from our transcriptomic data set, we found 51 DEGs (44 upregulated, 7 downregulated) associated with protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). From our proteomic data set, we found 23 ER-related proteins that were regulated under the elevated CO2 condition, and All of these DEPs were upregulated (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). These results suggested the protein synthesis and processing machinery may be promoted under the elevated CO2 condition.

In addition, we found 79 genes involved in ER-associated protein degradation, of which 37 were upregulated, while 13 were found to downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 7B; see Table S6). Meanwhile, our proteomic analysis indicated 53 proteins related to ER-associated protein degradation. Of these, three HSP20 proteins were downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, while the other 9 proteins were upregulated, such as DnaJ homolog subfamily A member 2 (DNAJA2), S-phase kinase-associated protein 1, and so on (Fig. 7B; see Table S6).

Basic carbon metabolism activities.

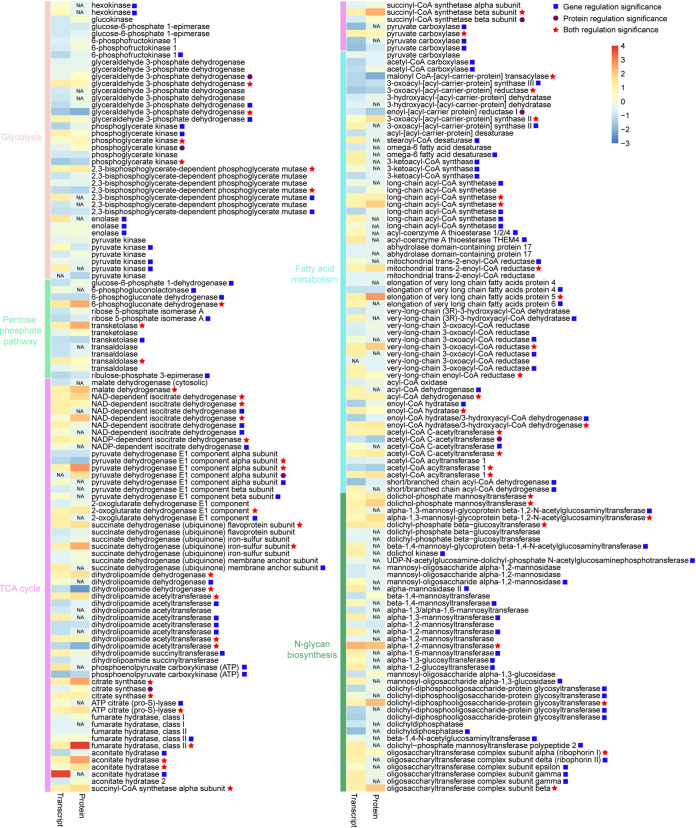

We found 38 glycolysis-associated genes, of which 22 genes (15 upregulated, 7 downregulated) displayed differential expression under the elevated CO2 condition. Interestingly, genes encoding rate-limiting enzymes of the glycolysis pathway, such as hexokinase (HK) and pyruvate kinase (PK), were significantly upregulated when S. marinoi was cultivated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7). This result indicated that glycolysis seemed to be facilitated by transcriptional upregulation of HK and PK. Meanwhile, our proteomic analysis identified 30 glycolysis-associated proteins, among which the expression of 8 proteins changed significantly, but HK and PK proteins displayed no differential expression under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Therefore, from the proteomic level, we concluded that the glycolysis pathway did not change significantly under the elevated CO2 condition.

FIG 8.

Heatmap showing changes in expression levels of genes/proteins involved in glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, the TCA cycle, fatty acid metabolism, and N-glycan biosynthesis. The heatmap color scale represents homogenized gene or protein expression values (log2-fold change) on a column z-score, increasing from blue (lowest) to red (highest). NA, not available.

Furthermore, we identified 65 TCA cycle-associated genes. Of these, 36 genes, such as citrate synthase (CS) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH), were upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, while 11 genes, annotated as pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit (PDHA), dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD), dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (DLAT), etc., were downregulated (Fig. 8; see Table S7), suggesting that the TCA cycle was enhanced under the elevated CO2 condition. Similar results were also found in our proteomic database that the TCA cycle was accelerated. Expression profiling showed that 24 proteins involved in the TCA cycle (in a total of 47 proteins) displayed upregulation in response to ocean acidification, but 3 proteins showed opposite expression patterns (see Table S7).

In addition, we searched genes involved in the pentose phosphate pathway and found that the transcript expression of 9 genes (4 upregulated, 5 downregulated) were significantly changed under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Meanwhile, iTRAQ analysis indicated that 3 proteins annotated as 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD), transketolase (TKT), and transaldolase (TALA) displayed significantly differential expression under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase (G6PDH) has been generally considered the rate-limiting enzyme for the pentose phosphate pathway. In this study, we detected that the G6PDH gene was downregulated transcriptionally but no change was detected at the protein level under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Taken together, our data sets indicated no upregulation and possibly slight downregulation of the pentose phosphate pathway under the elevated CO2 condition.

Fatty acid metabolism in eukaryotic microalgae mainly includes de novo synthesis of fatty acid in chloroplasts, elongation of fatty acids in mitochondria or the endoplasmic reticulum, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in chloroplasts or the endoplasmic reticulum, and oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria. In this study, seven genes associated with de novo synthesis of fatty acid showed significantly higher expression under the elevated CO2 condition. Of these, five genes encoding two acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylases (ACCase), malonyl CoA-(acyl-carrier protein) transacylase (MCAT), 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III (KASIII), and 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase (KAR) were downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, while two genes encoding 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase II (KASII) were upregulated (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Proteomic analysis indicated that three proteins encoding MCAT, enoyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase I (EARI), and KASII were differentially expressed between the control group and the experimental group. Among them, MCAT and EARI proteins exhibited downregulation expression profiles under the elevated CO2 condition, while KASII protein showed the opposite expression pattern (Fig. 8; see Table S7). We also searched genes involved in the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acid and found that stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and omega-6 fatty acid desaturase (FAD2) showed strong upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition. However, in our proteomic database, we only detected acyl-(acyl carrier protein) desaturase (ADD) protein, which displayed no significant differential expression under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 8; see Table S7).

For fatty acid elongation, we found 30 related genes from our transcriptomes, among which 19 genes displayed upregulation whereas three downregulation (Fig. 8; see Table S7). At protein level, 6 of 17 related proteins detected were strongly upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, such as long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (ACSL) (Fig. 8; see Table S7). For fatty acid oxidation, we obtained 16 associated genes. Among these, 9 genes were upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, while the other 4 genes were downregulated (Fig. 8; see Table S7). Totally, 13 proteins related to fatty acid oxidation were identified from our proteomic database. Among these proteins, six proteins showed significantly upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition, while two proteins annotated as ACAT and acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 (ACAA1) exhibited opposite expression pattern (Fig. 8; see Table S7).

N-glycosylation is a major co- and posttranslational modification in the synthesis of proteins in eukaryotes. N-glycan processing occurs in the secretory pathway and is essential for glycoproteins destined to be secreted or integrated into the membranes (21). Here, we identified 42 genes associated with N-glycan biosynthesis, among which 32 genes (28, upregulation; 4, downregulation) showed significant regulation under the elevated CO2 condition, such as dolichol-phosphate mannosyltransferase (DPM), dolichol kinase (DOLK), and so on (Fig. 8; see Table S7). iTRAQ analysis showed that 8 proteins (a total of 15 proteins) involved in N-glycan biosynthesis were differentially expressed between the control group and experiment group. Of note, all these DEPs exhibited upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition (see Table S7). These analyses showed that N-glycan biosynthesis was enhanced under the elevated CO2 condition, at both the transcriptional and the translational levels.

ROS homeostatic pathway, calcium signaling, and programmed cell death.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are typical by-products mainly due to the activation of NADPH oxidase, which is a respiratory-burst oxidase, catalyzing the NADPH-dependent reduction of O2 into the superoxide anion (O2•−) in cells (22). We searched for ROS homeostatic genes and found 26 were significantly regulated under the elevated CO2 condition. Of these, 18 genes, were upregulated, while 8 genes were downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S8). Moreover, we identified 15 DEPs associated with ROS homeostasis, and all of these showed upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S8). Besides, we also found 18 genes and 4 proteins associated with calcium signaling. With the exception of those for calcium-transporting ATPase, all of these DEGs were upregulated (Fig. 6; see Table S8). Meanwhile, two proteins annotated as calcium-transporting ATPase and calcium-translocating P-type ATPase were found to be upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S8).

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a form of autocatalyzed cell death mediated by expression of caspase-like and often leads to apoptosis (23). Comparative genome and EST analysis have characterized two distinct families of caspase-like proteins: paracaspase (PCA) and metacaspase (MCA) (24). Thus far, experiments to link PCD to caspase-like proteins have shown that only MCAs corresponded to autolysis in some species of marine diatoms (25, 26). In this study, three genes encoding MCA were found significantly downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, but all MCA proteins identified showed no changes in expression level under an elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S8).

DISCUSSION

At present (i.e., in 2020), the content of CO2 in the atmosphere exceeds 410 ppm, which is nearly 50% higher than that in the preindustrial period. These high growth rates are unprecedented in the past 55 million years of the geological record (27). About 25% CO2 is absorbed by the ocean, where it reacts with seawater to form a weak acid environment, causing surface ocean pH to drop by ∼0.004 U each year (1). The rate of this change is cause for serious concern, since many marine organisms may not be able to evolve quickly enough to adapt to these changes (28). There have been a few studies that examined the difference between short-term and long-term responses of diatoms communities to climate change variables. Tatters et al. (29) found that “artificial” communities comprising clonal isolates of diatoms conditioned to elevated-pCO2 conditions for 1 year yielded the same general competitive responses observed in the short-term (2 weeks) experiment with the natural marine diatom community. In another long-term experiment with freshwater diatoms community, there was no evidence for evolutionary change after over 750 generations at an elevated pCO2 (30). Similarly, 100 generations of selection by elevated pCO2 resulted in little adaptation or clade selection in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana (31). These results suggest that evolutionary adaptation to elevated CO2 after long-term exposure may be conserved in natural diatoms communities, without substantial evolutionary change. In the case of elevated pCO2, although some small phenotypic changes have been observed in the long-term incubations of the diatom species Nitzschia lecointei and Phaeodactylum tricornutum, since no evolutionary response has been detected, we cannot confirm whether it is a plastic or an adaptive response (32, 33). Therefore, it is important to study the effects of elevated pCO2 on diatoms in both the short and the long term, as well as evolutionary response.

Overall response under the elevated CO2 condition.

In this study, 32,389 unigenes and 1,826 proteins were significantly regulated under the elevated CO2 condition, which accounted for 48.5% of total genes and 25.9% of total proteins, respectively (Table 1). The lower growth rates of S. marinoi and remarkable changes in gene and protein expression under the elevated CO2 condition found in this study together clearly indicated that the physiological and biochemical characteristics of S. marinoi cells were affected by elevated pCO2. Therefore, the seawater inorganic carbon system that approximates conditions expected for the end of this century probably has a negative and significant impact on the growth of S. marinoi. An earlier investigation focusing on a unialgal fouling diatom Navicula distans found that warming (caused by the increase atmospheric pCO2 at the end of this century) and acidification synergistically significantly inhibited its growth (34). In contrast, another survey using model diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana found that elevated pCO2 had a positive effect on its growth under subsaturating growth light (35). For S. costatum, a congenic to our study species, growth was found to be enhanced at an enriched pCO2 of 750 μatm (36) but not at 800 μatm (37). These conflicting results are clear evidence that all species are not the same in responding to elevated CO2, which has significant implications in impacting phytoplankton community structure and hence the biogeochemistry cycle of the entire marine ecosystem. Through elaborate transcriptomic and proteomic analyses, a wide range of metabolic impacts was found for elevated CO2 on S. marinoi, but the results overall indicated that elevated pCO2 and the consequent decreased pH caused negative effects on growth and various physiological processes.

Consistent with the findings in previous investigations, our study showed that transcriptome analyses yield more data than iTRAQ quantification proteomics analyses. Furthermore, gene regulation can occur at transcriptional or translational or posttranslational level and, as such, transcriptomic profiles may not track proteomic profiles (38, 39). In the present study, the majority of proteins detected (60.8%, a total of 6,831 proteins) were correlated with transcripts (Table 1 and Fig. 2), whereas the other nearly 40% were not correlated, and more transcripts had no protein support. Therefore, the transcriptomic data provided a more comprehensive insight into cell metabolism, while the coherent part of the proteomic data provides verification. Combining proteomic and transcriptomic data sets allows us to yield a comprehensive insight into cell physiology and data robustness in many cases.

Enhancement of transcription and translation activities under the elevated CO2 condition.

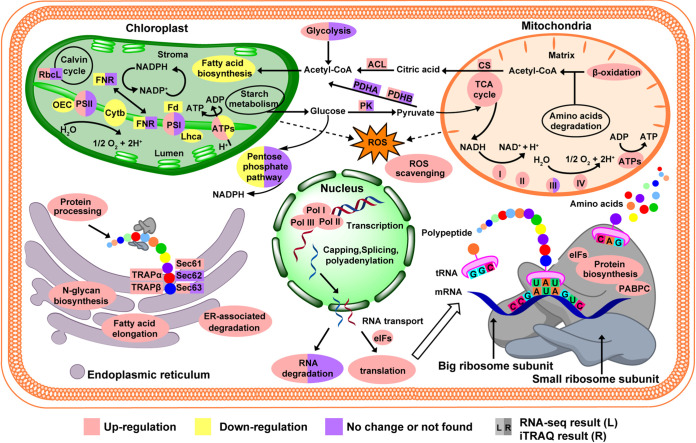

Three RNA polymerase (Pol) complexes—Pol I, II, and III—transcribe the genetic information (40). Pol I, II, and III are essential for the synthesis of ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs; ∼75%), messenger RNAs (mRNAs; 5 to 10%), and short structured RNAs (mainly 5S rRNA [5S rRNA] and transfer RNAs [tRNAs], ∼15%), respectively (41). In S. marinoi, both our transcriptome and proteome showed that Pol I, II, and III transcript or protein abundances were increased under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 9), indicating that RNA synthesis was promoted. Interestingly, the increased RNA synthesis seems to be offset by the increased degradation potential, as suggested by the upregulation of the RNA degradation pathway genes. This might be due to the need to accelerate reshuffling of the cellular metabolic pathways under the elevated CO2 conditions. In support of this possibility are the remarkable dynamics of different metabolic pathways revealed by the “omic” data sets.

FIG 9.

Schematic representation of basic biological pathways in S. marinoi under the elevated CO2 condition. RBCL, ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large chain; PSII, photosystem II reaction center; PSI, photosystem I reaction center; OEC, oxygen-evolving complex; Lhca, light-harvesting complex I chlorophyll a/b binding proteins; Cytb, cytochrome b6-f complex; Fd, ferredoxin; FNR, ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase; ACL, ATP citrate (pro-S)-lyase; CS, citrate synthase; PK, pyruvate kinase; PDHA, pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit; PDHB, pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit; I, NADH dehydrogenase; II, succinate dehydrogenase; III, cytochrome c reductase; IV, cytochrome c oxidase; ATPs, ATP synthase; Pol I, RNA polymerase I; Pol II, RNA polymerase II; Pol III, RNA polymerase III; eIFs, eukaryotic translation initiation factors; PABPC, polyadenylate-binding protein; TRAPα, translocon-associated protein subunit alpha; TRAPβ, translocon-associated protein subunit beta; Sec61, protein transport protein Sec61; Sec62, translocation protein Sec62; Sec63, translocation protein Sec63.

One of the metabolic pathways strongly influenced by OA was protein synthesis. In eukaryotic cells, the initiation of protein synthesis can be subdivided into three steps: first, assembling the 40S ribosomal subunit with an initiator methionyl-tRNA (Met-tRNAi); second, binding the resulting large macromolecular complex to the start codon of mRNA; and third, the 60S ribosomal subunit participating in generating a translation-competent ribosome (42). The previous publication has proved that all these three steps are facilitated by eukaryotic translation initiation factors (eIFs) (43). Our data showed that most genes or proteins associated with eIFs in S. marinoi were upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 7B), indicating increased translation initiation activity and hence increased protein synthesis. Translation initiation of most mRNAs in eukaryotic cells is accomplished by ribosome. After this, newly synthesized polypeptides are transported across or integrated into the ER membrane for protein folding, secretion, and glycosylation and facilitate the degradation of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen (44, 45). There is evidence that Sec61/SecY complex, which surrounds the polypeptide chain during its passage across the ER membrane, is the essential element for protein translocation (46, 47). Our transcriptomic and proteomic data showed that Sec61complex was upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 9). Furthermore, in both RNA-seq and iTRAQ analyses, we found that protein processing in the ER was also strongly accelerated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 9).

In eukaryotes, more than 50% of proteins are glycoproteins (48). The N-glycan biosynthesis that takes place in the ER is tightly implicated in the folding and retention, stability and turnover, intracellular trafficking, recognition and degradation, and physiological function of glycoproteins (49). In addition, N-glycan can also act as recognition tags to allow glycoproteins to interact with glycosyltransferases, glycosidases, and lectins (50). Interestingly, under elevated pCO2, both transcriptomic and proteomic analyses indicated that N-glycan biosynthesis was upregulated, indicating elevation of N-glycan formation (Fig. 9), which may promote the modification of glycoproteins. Together, these results suggest that elevated CO2 induced an increase in protein synthesis and processing. ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway is crucial for maintaining proteostasis by identifying and degrading normal and misfolded proteins (51–53). Our results suggest the molecular machinery for ERAD was activated under the elevated CO2 condition. This is consistent with our postulation of the need to accelerate metabolic reconfiguration and in addition the need to maintain proteostasis in the cells. More incorrect folding or assembly of proteins might happen under elevated CO2, imposing the need to degrade these misfolded proteins in the ERAD system and simultaneously synthesize new proteins.

The elevated protein synthesis and degradation, although likely a useful strategy for the cells to cope with elevated CO2, would divert cellular resources from other cell functions such as proliferation. In Escherichia coli, studies have suggested that increased protein production leads to reduced cell growth and stalled cell cycle (54, 55). This resource reallocation, or trade-off between stress coping and proliferation, seems to occur in S. marinoi. After acclimation for 10 generations, Thangaraj and Sun (56) found that OA did cause activated protein processing machinery because of increased amino acid synthesis and nitrogen assimilation in Skeletonema dohrnii. This result is consistent with our study, so we speculate that activated protein processing machinery may be an adaptation of Skeletonema species to OA. Population growth of S. marinoi declined under the elevated CO2 condition, while the capacity of protein production was expanded. Whether a similar regulatory mechanism exists in other diatoms warrants further investigation.

Downregulation of CCM and photosynthesis.

Photosynthetic carbon fixation depends on ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), the enzyme that catalyzes the first and critical step of both photosynthetic CO2 assimilation (57). Because Rubisco is very inefficient, CO2 concentration in the natural seawater (ca. 10 to 15 µM) is inadequate (half-saturation concentration, >25 µM) (58). Usually, diatoms and many other lineages of phytoplankton use carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM) to acquire carbon against the environment-cell uphill gradient. This includes C4 photosynthesis, carbonic anhydrase (CA), and bicarbonate transporters. C4 pathway has been proven to exist and operate in diatoms (12, 59, 60). Since CCM requires energy, it has been a topic of debate whether OA would reduce CCM capacity and hence save energy (10, 61). In this study, we found that S. marinoi indeed possesses C4 pathway and that it was indeed downregulated under the elevated CO2 condition. The C4 pathway involves phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) which fixes bicarbonate into the oxaloacetate (OAA, C4 acids) in the cytoplasm for subsequent transport into the chloroplast (62). In general, diatoms have two PEPC proteins, which may have different functions due to different subcellular localization (63). Consistent with previous studies, our study revealed the presence of two genes encoding PEPC (named PEPC1 and PEPC2) in S. marinoi. Analysis using CELLO (64) predicts that PEPC1 protein occurs in the cytoplasm, whereas PEPC2 protein occurs in mitochondria. Therefore, it is likely PEPC1, not PEPC2, that functions in the C4 pathway associated with photosynthetic carbon fixation. The downturn of CCM is also evident in the decreased protein expression of CA. However, if there was energy saved from lowered CCM machinery, it was not reinvested in photosynthesis, because the large subunit of Rubisco (RBCL) also displayed weak downregulation (albeit not significant) (Fig. 9). Combining proteomics and transcriptomic data has yielded the insight that CCMs is probably weakly downregulated by the elevated pCO2, and the weak downregulation of RBCL indicated a slight decrease in carbon fixation capacity.

Consistent with the above assessment, both proteomic and transcriptomic analysis showed that oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), light-harvesting complex I chlorophyll a/b binding proteins (Lhca), cytochrome c6 (Cytc6), and ferredoxin (Fd) were downregulated under elevated pCO2 (Fig. 9), indicating reduction of linear electron flow (LEF) and cyclic electron flow (CEF), resulting in the decrease of ATP synthesis. In accordance with this, elevated pCO2 caused the downregulation of chloroplastic ATP synthase.

Accelerated energy metabolism.

Energy metabolism via glycolysis, the TCA cycle, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), mitochondrial electron transport, and oxidative phosphorylation through which ATP, NAD(P)H, and various intermediate carbon compounds are generated is necessary for cell maintenance and growth (65). Increased acidity of seawater associated with elevated pCO2 can disturb intracellular pH stability, so that diatom may have a greater need for energy in order to maintain cellular homeostasis (5). A previous report, focusing on diatoms and coccolithophores, indicated that elevated pCO2 could increase the activity of glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and β-oxidation of the fatty acid pathway (66). Transcriptomic analysis of 2% against 0.4% CO2-cultured Coccomyxa subellipsoidea C-169 has unveiled that the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and oxidative phosphorylation were predominantly upregulated under increased pCO2, and this pattern could provide more energy and intermediate carbon compounds to respond to environmental stress (67). In this study, most DEGs or DEPs identified in the mitochondrial respiration were upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, indicative of enhanced energy metabolic capacity.

Lipid synthesis and consumption are also important energy pathway. The effect of CO2 variation on fatty acid content and composition has been previously reported for Skeletonema, but there seem to be differences among different species. For instance, in S. pseudocostatum, the total fatty acid concentration remarkably decreased under elevated pCO2 (9). In contrast, high temperature and pCO2 (25°C, 1,000 ppm) increased the productivity of fatty acid in S. dohrnii (11). In our iTRAQ study, we found that fatty acid metabolism was significantly enriched under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 4). Most DEGs/DEPs identified in de novo fatty acid biosynthesis were downregulated under elevated CO2, a finding indicative of reduced fatty acid synthesis capacity (Fig. 8 and 9). However, synthesis of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) seems to be promoted by elevated CO2 in our study. It has been characterized that KASII mediates the elongation of C16:0-ACP to C18:0-ACP through the condensation of two-carbon units in the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis pathway (68). Subsequently, the C18 acyl may serve as precursors for the elongation of LCFAs. Interestingly, both the KASII transcript and protein were upregulated, as were genes/proteins associated with LCFA syntheses, such as ACSL, ELOVL5, VLKAR, and VLECR (Fig. 8), which could potentially promote LCFA production. Besides, from the transcriptomic, we found that 2 genes encoding stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) and omega-6 fatty acid desaturase (FAD2) were upregulated, which, if verified to be so at proteins and activity levels, indicates promotion of PUFA production. Consistent with the finding in the present study, Liang et al. (16) document that elevated pCO2 favored synthesis of PUFAs in Dunaliella salina. To use storage lipids efficiently, fatty acids need to be completely converted from acyl-CoA to acetyl-CoA by fatty acid β-oxidation (69). Interestingly, many genes/proteins associated with β-oxidation were upregulated, which could potentially generate more energy for the survival and growth of S. marinoi cells. As previously reported, β-oxidation is a potential site for ROS formation, because the intermediates and by-products of β-oxidation can interfere with antioxidant mechanisms (70). Therefore, we speculated that β-oxidation, such as complexes I, II, III, and IV, could also promote ROS production. Taken together, the reduction in total fatty acids and increases in LCFAs, PUFAs, and β-oxidation under acidification may affect cell growth and survival, the turnover of membrane lipids, and the rapid mobilization of storage lipids.

Nitrogen uptake and metabolism.

In our study, nitrate was the only N source of S. marinoi. From the transcriptomic data set, we found that nitrate transporter (NRT), nitrate reductase (NR), and nitrite reductase-ferredoxin (NiR) were all upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition, but there was no significant change in protein levels (Fig. 5; see Table S3), raising uncertainty about increasing N uptake. However, carbamoyl phosphate synthase (CPS) and glutamine synthetase (GS) were all upregulated under elevated CO2 in both transcriptional and translational levels (Fig. 5; see Table S3), a finding indicative of the acceleration of N assimilation and urea cycle.

It is interesting to note that the inorganic phosphate transporter protein was also upregulated under elevated pCO2. This is consistent with the intensification of energy metabolism discussed earlier, which may require more phosphorus. We also found that the ABC transporter families displayed significant regulation. The ABC transporters bind ATP and use energy to shuttle a great variety of molecules across different cellular membranes (71). Metals are indispensable for microalga cells to perform their cellular functions, since they not only serve as components for photosynthetic system and constituents of vitamins but also act as cofactors for enzymes involving in CO2 fixation, nitrate reduction, phosphorus acquisition, and DNA transcription (72). Combining our transcriptomic and proteomic data, we found that metal uptake, such as calcium, potassium, zinc, and iron, showed significantly upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition. This suggests that S. marinoi might require more metal ions to cope with decreased pH. Alternatively, the upregulation of the uptake genes might indicate compromised bioavailability of metals under acidification, as demonstrated in the case of iron (73).

Cross talk among ROS, calcium signaling, and programmed cell death.

In plants, ROS-coupled calcium signaling is largely recognized to be important signal mediators, which is involved in many cellular processes, including growth, development, differentiation, programmed cell death (PCD), and so on (74–76). In this study, we particularly focused on the cross-relationship among ROS, calcium signaling, and PCD. An abundance of publications indicates that Ca2+ or calmodulin causes activation of NADPH oxidase and, in consequence, augmentation of ROS production (77–79). Previous studies have shown that diatoms use a novel and highly sensitive Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway to sense and respond to abiotic environmental signals (80, 81). For example, aequorin-transformed P. tricornutum cells exhibit rapid cytosolic Ca2+ elevations in response to mechanical stimuli (81). After a period of phosphorus (P)-limited growth, phosphate resupply results in rapid, transient elevations in the cytosolic Ca2+ of P. tricornutum (80). In our S. marinoi transcriptomic study, we found that the calcium-translocating P-type ATPase and Ca2+-permeable channels were all upregulated under the elevated CO2 condition (Fig. 6; see Table S8), which could potentially promote a rapid influx of Ca2+ into the cytosol. Interestingly, some Ca2+ efflux genes, such as two-pore calcium channel protein 1 and calcium-transporting ATPase, also exhibited upregulation under the elevated CO2 condition. The potential increase of Ca2+ traffic might indicate accelerated calcium signaling under the elevated CO2 condition. The previous study also showed that OA can affect environmental sensing of microalgae and thus enhance cellular Ca2+ fluxes (82). Therefore, we speculate that the activated Ca2+ transport and calcium signaling may be responses to elevated pCO2.

ROS can react very rapidly with proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, thereby resulting in severe cell damage and cell death (83). Potentially toxic free radicals can be removed by ROS scavenging systems composing of diverse enzymatic antioxidants such as glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and some small molecules of nonenzymatic antioxidants such as ascorbic acid (84). That is, scavenging mechanisms hold the cellular steady-state level of ROS under tight control. RNA-seq analysis suggested that the upregulation of NADPH oxidase triggered the augmentation of ROS production. Correspondingly, under the elevated pCO2, most DEGs and all DEPs annotated as enzymatic antioxidants were upregulated, indicating enhanced ROS scavenging capacity. It has been proposed that PCD can be triggered by higher doses of ROS (85, 86). In marine diatom, metacaspase (MCA) is considered the most common molecular marker for PCD (25, 26). However, while MCA genes showed significant downregulation under the elevated CO2 condition, MCA proteins displayed no significant change in expression. Despite the discrepancy, both transcriptomic and proteomic data sets agreed that elevated pCO2 did not induce PCD. This might have been made possible because S. marinoi was able to maintain stable ROS levels due to its upregulated ROS scavenging capacity.

Conclusions.

Our study showed that elevated CO2 repress photosynthesis and growth of S. marinoi, and the “omic” data suggested that this might be due to compromised photosynthesis and fatty acid biosynthesis in the chloroplast and raised mitochondrial energy metabolism. Meanwhile, our data revealed the upregulation of nitrogen metabolism, transcriptional activity, and translational activity, implying a heightened potential of protein synthesis. The increased protein synthesis and energy metabolism might be required for cells to maintain intracellular homeostasis in face of decreasing pH. In addition, elevated pCO2 seemed to promote ROS production and anti-oxidative stress capacity in S. marinoi, and apparently due to balance of ROS and antioxidant, no PCD induction was observed. Overall, elevated pCO2 seems to cause massive gene expression reconfiguration to increase investment in protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and antioxidative stress defense, likely to maintain pH homeostasis and population survival. Although the evolutionary adaptation of diatoms to OA after long-term exposure may be conserved, it is noteworthy that some phenotypic changes were observed between short-term and long-term incubations. Therefore, further research should be focused on long-term physiological responses of S. marinoi to OA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Algal culture and CO2 manipulation.

The strain of S. marinoi was obtained from the Algae Culture Center of Key Laboratory of the Marine Environment and Ecology, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China. Batch cultures of S. marinoi were maintained in 1-liter sterilized Erlenmeyer flasks with 500 ml of f/2 medium using the 0.22-μm pore-size Millipore filtered and autoclaved natural seawater (from Jiaozhou Bay, a shallow semiclosed bay near Qingdao city on the Yellow Sea coast in the north of China) at 20°C under a 12-h/12-h light and dark cycle, with a light intensity of ∼80 μmol of photons m−2 s−1.

To set up CO2 treatment, S. marinoi cells in the midexponential phase were collected by centrifuge (4,000 × g at 20°C for 10 min), and the cell pellet was suspended and inoculated into six Erlenmeyer flasks with an initial cell density of 1 × 105 cells ml−1. Prior to inoculation, the cultures were aerated for 24 h at two different CO2 levels (ca. 400 and 1,000 ppm) at an aeration rate of 300 ml min−1, corresponding to the current approximate CO2 level in the atmosphere and the predicted level in 2,100, respectively. The outdoor air was used for the ambient CO2 treatment (control), whereas 1,000-ppm CO2 treatment (with <5% variation) was achieved by mixing 99.99% CO2 with zero-CO2 air using plant CO2 chambers (HP400G-D; Ruihua Instrument & Equipment, Ltd., Wuhan, China). The two different CO2 mixtures were pumped into the culture flasks through 0.22-µm Millex-GP sterile syringe filters (SLGP033RS; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, VT) using air compression pumps. Each treatment was made in triplicate. The cell density was determined daily by using a phytoplankton counting chamber (Sangon, Shanghai, China). pH values were monitored daily at the same time as sampling using an Orion VersaStar Pro multiparameter benchtop meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA) performed with three points of pH calibration. The following formula was used to calculate intrinsic growth rates: µ = ln(N2/N1)/(t2/t1), where N2 and N1 are the cell densities at times t2 and t1, respectively (87).

Sample collection, RNA extraction, and RNA-seq.

When the cultures entered the late exponential phase (day 5), S. marinoi cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C for RNA and protein extraction. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and then stored at –80°C until subsequent extraction. Total RNA was extracted using l ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of extracted RNA was assessed on NanoDrop (ND-2000 spectrophotometer; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE), while the integrity was measured on an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

Samples with an RNA integrity number of ≥7.8 were used for transcriptomic sequencing. Briefly, 1 µg of total RNA from each sample was used for enriching poly(A) mRNA to construct a paired-end RNA-seq library and subsequently processed for transcriptomic sequencing. Paired-end sequencing of 2 × 100-bp was performed on the BGISEQ-500 platform (BGI Genomics Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) to obtain >50 million read pairs per sample. To obtain the clean data, low-quality reads, reads containing adapters, and reads with ambiguous “N” nucleotides were identified and removed. After the quality control procedure, the filtered reads were assembled de novo using Trinity software (v2.0.6) (88).

Gene functional annotation and DEG analysis.

For functional annotation, all unigenes were mapped to seven public databases with a threshold E value of 10−5. These databases included NCBI nonredundant nucleotide (Nt), NCBI nonredundant protein (Nr), Swiss-Prot, Pfam, Eukaryotic Ortholog Groups (KOG), Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). For DEG analysis, RSEM (v1.2.8) with default parameters was used to estimate gene expression for each sample (89). The fold change values were calculated by the DEGseq (an R package) (90), and the P values were adjusted for multiple testing (91) and statistical significance analysis (92). Genes with fold changes of ≥2 and adjusted P values (Q values) of ≤0.001 were selected as DEGs for subsequent analysis. GO annotation or KEGG functional enrichment analysis was performed using the phyper function of the R package to identify significantly enriched GO terms or KEGG pathway (false discovery rate [FDR] values of ≤0.01) associated with DEGs.

Protein extraction.

Before protein extraction, frozen samples of S. marinoi were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times. Each pellet was subsequently homogenized in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM protease inhibitor, and 2 mM EDTA). After being placed on ice for 5 min, the lysate with 10 mM dithiothreitol was sonicated at 4°C for 2 min and centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C; the supernatant was then collected. The supernatant was mixed with a 4× volume of acetone. The mixture was vortexed, precipitated at −20°C overnight, and centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove the supernatants. Precipitated proteins were dried at 4°C, redissolved in lysis buffer, sonicated (50 Hz) at 4°C for 2 min, and centrifuged at 25,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. We then collected the supernatants and incubated the protein solutions at 56°C for 1 h to reduce the disulfide bonds. After cooling to room temperature, the protein solution was incubated with a final concentration of 55 mM iodoacetamide for 45 min in the dark for alkylation. Cooling acetone was added again, and the samples were precipitated at −20°C overnight and centrifuged to obtain the precipitation. After being air dried at 4°C, the lysis buffer was used to solubilize protein pellets. The protein concentration and integrity were determined by a Bradford assay and SDS-PAGE.

Protein digestion, iTRAQ labeling, and peptide fractionation.

The protein solutions (100 μg) were diluted four times with 100 mM tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the protein was digested by Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI) with a protein/trypsin ratio of 40:1 at 37°C overnight. After trypsin digestion, the peptides were desalted and purified by using a Strata X C18 column (Phenomenex, Tianjin, China) and vacuum-dried. The peptides (100 μg) were dissolved in 30 µl of TEAB (0.5 M) with vortexing. After the iTRAQ reagents were thawed to room temperature, 50 µl of isopropyl alcohol was added to each reagent vial. The six peptide samples were labeled with 6 of 8 iTRAQ 8-Plex Reagents (reagents 113, 116, 117, 118, 119, an 121) and then fractionated on a high-pH reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) pump system (Shimadzu LC-20AB; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) coupled with Gemini C18 (4.6 × 250 mm; particle size, 5 μm) columns (Phenomenex, Tianjin, China).

LC-MS/MS analysis.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis was performed on an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) coupled to a Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode by nano-electrospray ionization. Briefly, peptides in buffer A (2% acetonitrile, 1% formic acid) were injected to a homemade nanocapillary C18 column (75 μm × 25 cm; particle size, 3 μm) with a 50-min linear gradient from 5 to 80% buffer B (98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 300 nl min−1. The gradient began at 5% buffer B; increased to 25% in 40 min, 25 to 35% in 5 min, and 35 to 80% in 2 min; was maintained at 80% for 2 min; and finally returned to 5% in 1 min and equilibrated for 6 min.

For MS analysis, the Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometry was operated in DDA mode with an electrospray voltage of 2.0 kV. MS data were acquired in full scan mode (350 to 1500 m/z) with a resolution of 60,000 and an automatic gain control (AGC) threshold of 3 × 106. From the full MS scan, the 20 most abundant precursor ions above a threshold ion count of 10,000 were selected as MS/MS data for higher-energy collisional dissociation fragmentation at a resolution of 15,000 (at 100 m/z), a normalized collision energy of 30%, a dynamic exclusion time of 30 s, and an AGC target value of 1 × 105.

Protein identification and bioinformatics analysis.

For protein identification, the raw MS/MS data were submitted to a Mascot (v2.3.02) search against the aforementioned transcriptome database of S. marinoi. The final selected protein must contain at least one unique peptide. The IQuant software was used for protein quantification (93). The IQuant settings were set according to the “picked protein FDR strategy” with an FDR value of a peptide or protein of ≤0.01 (94). A protein with a fold change of >1.2 and a P value of <0.05 was accepted as the differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). To deeply analyze the DEPs and explore the potential mechanism of ocean acidification on S. marinoi, DEPs were used to perform GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment.

Statistical analysis.

To evaluate the statistical significance of the differences observed between the ambient CO2 group and the elevated CO2 group, variance analysis was carried out by using SPSS 17.0 with one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc tests. A probability (P) value of <0.05 was considered the threshold of statistical significance.

Data availability.

The transcriptomic sequencing data in this study have been submitted to GenBank’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under accession number PRJNA661548. The mass spectrometry-based proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange consortium via PRIDE under the data set identifier PXD021416.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tangcheng Li and Hongfei Li of Marine EcoGenomics Laboratory of Xiamen University, China, for assistance with the bioinformatics of the RNA-seq data and the iTRAQ proteomics data.

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 41976133), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC1404402 and 2017YFC1404404), and the Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of the Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (2016ASKJ02).

M.Z. and T.M. designed and performed experiments. M.Z., Y.Z., and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

We declare that there are no conflicts of interests regarding this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM. 2013. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Working Group Contribution I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1535. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torstensson A, Chierici M, Wulff A. 2012. The influence of increased temperature and carbon dioxide levels on the benthic/sea ice diatom Naviculadirecta. Polar Biol 35:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s00300-011-1056-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P. 1998. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarthou G, Timmermans KR, Blain S, Tréguer P. 2005. Growth physiology and fate of diatoms in the ocean: a review. J Sea Res 53:25–42. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2004.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao K, Campbell DA. 2014. Photophysiological responses of marine diatoms to elevated CO2 and decreased pH: a review. Funct Plant Biol 41:449–459. doi: 10.1071/FP13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riebesell U, Schulz KG, Bellerby RGJ, Botros M, Fritsche P, Meyerhöfer M, Neill C, Nondal G, Oschlies A, Wohlers J, Zöllner E. 2007. Enhanced biological carbon consumption in a high CO2 ocean. Nature 450:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature06267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bach LT, Alvarez-Fernandez S, Hornick T, Stuhr A, Riebesell U. 2017. Simulated ocean acidification reveals winners and losers in coastal phytoplankton. PLoS One 12:e0188198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennon GM, Hernández Limón MD, Haley ST, Juhl AR, Dyhrman ST. 2017. Diverse CO2-induced responses in physiology and gene expression among eukaryotic phytoplankton. Front Microbiol 8:2547. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob BG, Von Dassow P, Salisbury JE, Navarro JM, Vargas CA. 2017. Impact of low pH/high pCO2 on the physiological response and fatty acid content in diatom Skeletonema pseudocostatum. J Mar Biol Ass 97:225–233. doi: 10.1017/S0025315416001570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang G, Gao K. 2012. Physiological responses of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana to increased pCO2 and seawater acidity. Mar Environ Res 79:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thangaraj S, Sun J. 2020. The biotechnological potential of the marine diatom Skeletonema dohrnii to the elevated temperature and pCO2 concentration. Marine Drugs 18:259. doi: 10.3390/md18050259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young JN, Hopkinson BM. 2017. The potential for co-evolution of CO2-concentrating mechanisms and Rubisco in diatoms. J Exp Bot 68:3751–3762. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinfelder JR. 2011. Carbon concentrating mechanisms in eukaryotic marine phytoplankton. Annu Rev Mar Sci 3:291–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkinson BM, Dupont CL, Allen AE, Morel FM. 2011. Efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of diatoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:3830–3837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018062108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flynn KJ, Blackford JC, Baird ME, Raven JA, Clark DR, Beardall J, Brownlee C, Fabian H, Wheeler GL. 2012. Changes in pH at the exterior surface of plankton with ocean acidification. Nat Clim Chang 2:510–513. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang C, Wang L, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang X, Ye N. 2020. The effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on changes in fatty acids and amino acids of three species of microalgae. Phycologia 59:208–210. doi: 10.1080/00318884.2020.1732714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooistra WH, Sarno D, Balzano S, Gu H, Andersen RA, Zingone A. 2008. Global diversity and biogeography of Skeletonema species (Bacillariophyta). Protist 159:177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godhe A, McQuoid MR, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I, Rehnstam-Holm AS. 2006. Comparison of three common molecular tools for distinguishing among geographically separated clones of the diatom Skeletonema marinoi Sarno et Zingone (Bacillariophyceae) 1. J Phycol 42:280–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00197.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson ON, Töpel M, Pinder MI, Kourtchenko O, Blomberg A, Godhe A, Clarke AK. 2019. Skeletonema marinoi as a new genetic model for marine chain-forming diatoms. Sci Rep 9:10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41085-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Härnström K, Ellegaard M, Andersen TJ, Godhe A. 2011. Hundred years of genetic structure in a sediment revived diatom population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:4252–4257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013528108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baïet B, Burel C, Saint-Jean B, Louvet R, Menu-Bouaouiche L, Kiefer-Meyer M-C, Mathieu-Rivet E, Lefebvre T, Castel H, Carlier A, Cadoret J-P, Lerouge P, Bardor M. 2011. N-glycans of Phaeodactylum tricornutum diatom and functional characterization of its N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I enzyme. J Biol Chem 286:6152–6164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vignais P. 2002. The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase: structural aspects and activation mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci 59:1428–1459. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8520-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker MS, Mock T, Armbrust EV. 2008. Genomic insights into marine microalgae. Annu Rev Genet 42:619–645. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uren AG, O’Rourke K, Aravind LA, Pisabarro MT, Seshagiri S, Koonin EV, Dixit VM. 2000. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Molecular Cell 6:961–967. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bidle KD, Bender SJ. 2008. Iron starvation and culture age activate metacaspases and programmed cell death in the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Eukaryot Cell 7:223–236. doi: 10.1128/EC.00296-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi C, Berges J. 2013. New types of metacaspases in phytoplankton reveal diverse origins of cell death proteases. Cell Death Dis 4:e490. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gingerich PD. 2019. Temporal scaling of carbon emission and accumulation rates: modern anthropogenic emissions compared to estimates of PETM onset accumulation. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 34:329–335. doi: 10.1029/2018PA003379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guinotte JM, Fabry VJ. 2008. Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1134:320–342. doi: 10.1196/annals.1439.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatters AO, Roleda MY, Schnetzer A, Fu F, Hurd CL, Boyd PW, Caron DA, Lie AA, Hoffmann LJ, Hutchins DA. 2013. Short-and long-term conditioning of a temperate marine diatom community to acidification and warming. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20120437. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low-Décarie E, Jewell MD, Fussmann GF, Bell G. 2013. Long-term culture at elevated atmospheric CO2 fails to evoke specific adaptation in seven freshwater phytoplankton species. Proc Biol Sci 280:20122598. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawfurd KJ, Raven JA, Wheeler GL, Baxter EJ, Joint I. 2011. The response of Thalassiosira pseudonana to long-term exposure to increased CO2 and decreased pH. PLoS One 6:e26695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F, Beardall J, Collins S, Gao K. 2017. Decreased photosynthesis and growth with reduced respiration in the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum grown under elevated CO2 over 1800 generations. Glob Chang Biol 23:127–137. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torstensson A, Hedblom M, Mattsdotter Björk M, Chierici M, Wulff A. 2015. Long-term acclimation to elevated pCO2 alters carbon metabolism and reduces growth in the Antarctic diatom Nitzschia lecointei. Proc R Soc B 282:20151513. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baragi LV, Khandeparker L, Anil AC. 2015. Influence of elevated temperature and pCO2 on the marine periphytic diatom Navicula distans and its associated organisms in culture. Hydrobiologia 762:127–142. doi: 10.1007/s10750-015-2343-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li G, Campbell DA. 2013. Rising CO2 interacts with growth light and growth rate to alter photosystem II photoinactivation of the coastal diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. PLoS One 8:e55562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JM, Lee K, Shin K, Kang JH, Lee HW, Kim M, Jang PG, Jang MC. 2006. The effect of seawater CO2 concentration on growth of a natural phytoplankton assemblage in a controlled mesocosm experiment. Limnol Oceanogr 51:1629–1636. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.4.1629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X, Gao K. 2003. Effect of CO2 concentrations on the activity of photosynthetic CO2 fixation and extracellular carbonic anhydrase in the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum. Chinese Sci Bull 48:2616–2620. doi: 10.1360/03wc0084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mata J, Marguerat S, Bähler J. 2005. Posttranscriptional control of gene expression: a genome-wide perspective. Trends Biochem Sci 30:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McManus J, Cheng Z, Vogel C. 2015. Next-generation analysis of gene expression regulation-comparing the roles of synthesis and degradation. Mol Biosyst 11:2680–2689. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00310e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vannini A, Cramer P. 2012. Conservation between the RNA polymerase I, II, and III transcription initiation machineries. Mol Cell 45:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warner JR. 1999. The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci 24:437–440. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sonenberg N, Dever TE. 2003. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors and regulators. Curr Opin Struct Biol 13:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merrick WC, Pavitt GD. 2018. Protein synthesis initiation in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10:a033092. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park E, Rapoport TA. 2012. Mechanisms of Sec61/SecY-mediated protein translocation across membranes. Annu Rev Biophys 41:21–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Araki K, Nagata K. 2011. Protein folding and quality control in the ER. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3:a007526. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mothes W, Prehn S, Rapoport TA. 1994. Systematic probing of the environment of a translocating secretory protein during translocation through the ER membrane. EMBO J 13:3973–3982. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Görlich D, Rapoport TA. 1993. Protein translocation into proteoliposomes reconstituted from purified components of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Cell 75:615–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomord V, Fitchette AC, Menu-Bouaouiche L, Saint-Jore-Dupas C, Plasson C, Michaud D, Faye L. 2010. Plant-specific glycosylation patterns in the context of therapeutic protein production. Plant Biotechnol J 8:564–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helenius A, Aebi M. 2004. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lannoo N, Van Damme EJ. 2015. Review/N-glycans: the making of a varied toolbox. Plant Sci 239:67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knopf JD, Landscheidt N, Pegg CL, Schulz BL, Kühnle N, Chao CW, Huck S, Lemberg MK. 2020. Intramembrane protease RHBDL4 cleaves oligosaccharyltransferase subunits to target them for ER-associated degradation. J Cell Sci 133:jcs243790. doi: 10.1242/jcs.243790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hampton RY. 2002. ER-associated degradation in protein quality control and cellular regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14:476–482. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips BP, Gomez-Navarro N, Miller EA. 2020. Protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr Opin Cell Biol 65:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott M, Gunderson CW, Mateescu EM, Zhang Z, Hwa T. 2010. Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: origins and consequences. Science 330:1099–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1192588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klumpp S, Scott M, Pedersen S, Hwa T. 2013. Molecular crowding limits translation and cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:16754–16759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310377110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]