Poultry litter compost, commonly used as a biological soil amendment, is subjected to a physical heat treatment in the industry setting to reduce pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella and produce a dry product. According to the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) produce safety rule, the thermal process for poultry litter compost should be scientifically validated to satisfy the microbial standard requirement.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella surrogate, indicator microorganism, plant validation, poultry litter compost, physical heat treatment

ABSTRACT

This study selected and used indicator and surrogate microorganisms for Salmonella to validate the processes for physically heat-treated poultry litter compost in litter processing plants. Initially, laboratory validation studies indicated that reductions of 1.2 to 2.7 log or more of desiccation-adapted Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 were equivalent to >5-log reductions of desiccation-adapted Salmonella enterica serovar Senftenberg 775/W in poultry litter compost, depending on treatment conditions and compost types. Plant validation studies were performed in one turkey litter compost processor and one laying hen litter compost processor. E. faecium was inoculated at ca. 7 log CFU g−1 into the turkey litter compost and at ca. 5 log CFU g−1 into laying hen litter compost with respectively targeted moisture contents. The thermal processes in the two plants yielded 2.8 to >6.4 log CFU g−1 (>99.86%) reductions in E. faecium. Similarly, for the processing control samples, reductions of presumptive indigenous enterococci were on the order of 1.8 to 3.7 log CFU g−1 (98.22% to 99.98%) of the total naturally present. In contrast, there were fewer reductions of indigenous mesophiles (1.7 to 2.9 log CFU) and thermophiles (0.4 to 3.2 log CFU g−1). More indigenous enterococci were inactivated in the presence of higher moisture in the poultry litter compost. Based on the data collected under the laboratory conditions, the processing conditions in both plants were adequate to reduce any potential Salmonella contamination of processed poultry litter compost by at least 5 logs, even though the processing conditions varied among trials and plants.

IMPORTANCE Poultry litter compost, commonly used as a biological soil amendment, is subjected to a physical heat treatment in the industry setting to reduce pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella and produce a dry product. According to the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) produce safety rule, the thermal process for poultry litter compost should be scientifically validated to satisfy the microbial standard requirement. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first validation study in commercial poultry litter compost processing plants, and our results indicated that Salmonella levels, if present, could be reduced by at least 5 logs based on the reductions of surrogate and indicator microorganisms, even though the processing conditions in these commercial plants varied greatly. Furthermore, both indicator and surrogate microorganisms along with the custom-designed sampler can serve as practical tools for poultry litter compost processors to routinely monitor or validate their thermal processes without introducing pathogens into the industrial environments.

INTRODUCTION

Poultry litter contains essential nutrients for crop growth (1) and is often used in organic farming as biological soil amendments of animal origin (BSAAO). Based on the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI)/USDA National Organic Program (NOP) and California Leafy Green Marketing Agreement rules, the use of raw manure on fresh produce for human consumption is discouraged due to the possible presence of human pathogens such as Salmonella spp. (2, 3). Either composting or physical heat is recommended to reduce pathogens in poultry litter used as organic fertilizer for growing fresh produce (4). According to the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) produce safety rule (5), the thermal process for animal manure or other biological soil amendments should be scientifically validated to satisfy the microbial standard requirement for Salmonella species, i.e., <3 most probable number per 4 g. Unfortunately, there is very limited research on the microbiological safety of physically heat-treated poultry litter or poultry litter compost. Therefore, scientific data and practical validation methods for thermal inactivation of Salmonella are urgently needed for the industry.

The introduction of pathogenic strains of microorganisms into the industrial environment is not allowed for plant validation studies. Hence, indigenous or nonpathogenic bacteria with growth/survival characteristics similar to those of pathogens should be used as an indicator or surrogate microorganism to understand the growth/survival behaviors of pathogens in industrial environments (6). Côté et al. (7) reported that a reduction of 1.6 to 4.2 log CFU ml−1 total coliforms and a reduction of 2.5 to 4.2 log CFU ml−1 indigenous Escherichia coli resulted in undetectable levels of indigenous Salmonella in swine slurries during anaerobic digestion. Qi et al. (8) also reported that a reduction of 91.1% enterococci and a reduction of 99.7% indigenous E. coli resulted in 99.3% of indigenous Salmonella in dairy manure during anaerobic digestion. During composting or stockpiling, the counts of presumptive indigenous enterococci and mesophiles in poultry litter ranged from 3.0 to 7.5 log CFU g−1 and 6.6 to 8.9 log CFU g−1, respectively, which can provide sufficient populations for evaluating the survival behaviors of Salmonella in poultry litter during subsequent thermal treatment (9–11). Likewise, our previous study (11) reported a correlation (R2 > 0.88) between the mean log reductions of Salmonella enterica serovar Senftenberg 775/W with those of presumptive indigenous enterococci in turkey litter compost samples with 20 to 50% moisture contents at 75°C compared to total aerobic bacteria. This previous work suggested that presumptive indigenous enterococci are an indicator for validating the effectiveness of thermal processing. Several bacterial species have been recommended as Salmonella surrogates in different matrices, such as Pediococcus acidilactici ATCC 8042 and Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 in dry pet food (12), E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and Pantoea agglomerans SPS2F1 in almonds (13), and Pediococcus spp. in beef or turkey jerky (14, 15). Among those surrogates, E. faecium NRRL B-2354 has been widely used as a surrogate for S. enterica for validating the thermal processing of nuts and carbohydrate-protein meal (16, 17). The safety of E. faecium NRRL B-2354 as a surrogate has been thoroughly studied by Kopit et al. (18) by sequencing, confirming that this strain lacks genomic and phenotypic characteristics linked to nosocomial infections.

Our previous laboratory-based studies on the thermal inactivation of Salmonella in poultry litter compost have revealed that Salmonella cells were killed at 70 to 150°C within 30 min to 6 h, depending on the bacterial physiological status (desiccation adapted or not), moisture level, and experimental design (19, 20). Although these laboratory-based studies indicated that the thermal treatment conditions completely inactivated Salmonella, the conclusions could differ from those in the industrial settings, in which the processing capacity is scaled up and heterogeneity of poultry litter compost or treatments may exist. During a processing plant validation study, the effects of other operational factors, such as dryer construction and temperature (Table 1), residence time, and characteristics of processing products, on microbial inactivation also should be evaluated (21). To date, there is no published study on validating the thermal processing of BSAAO in thermal processing plant settings.

TABLE 1.

Summary for plant trials

| Planta | Dryer specification |

Target moisture content of compost (%) | Date performed (mo/day/yr) | Total no. of samples analyzed after heat treatment | No. of processing controls collected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (m) | Temp (°C) | Process capacity (kg/h) | |||||

| A | 3.7 diam/15.2 length | Inlet, 593 | 4,082.3 | 44 | 11/16/2016 | 22 | 4 |

| Outlet, 65–82 | 7/19/2017, 8/8/2017 | 24 | 4 | ||||

| 36 | 4/28/2017 | 30 | 4 | ||||

| 6/29/2017 | 24 | 4 | |||||

| B | 0.9 diam/ca. 2.3 length | 65–104 | 604.8–642.6 | 15 | 12/13/2017 | 24 | 2 |

Plant A, processes turkey litter compost with 6 months of aerobic thermophilic stabilization. Plant B, processes composted chicken manure mixed with bone meal (laying hen litter compost).

The objectives of this study were to (i) compare the thermal resistance of S. Senftenberg 775/W and its surrogate, E. faecium NRRL B-2354, in poultry litter compost under laboratory conditions; (ii) validate the thermal processing conditions for poultry litter compost in two litter compost processing plants using Salmonella surrogate and indicator microorganisms; and (iii) determine the factors affecting the thermal inactivation of Salmonella surrogate and indicator microorganisms in industry settings.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparing heat resistance between desiccation-adapted E. faecium and S. Senftenberg 775/W under laboratory conditions.

To accurately enumerate heat-injured E. faecium and presumptive indigenous enterococci from turkey litter compost, six culturing methods were compared for recovering heat-injured cells of enterococci. Due to the interference from background microorganisms with the similar morphology shown on plates (data not shown), overlay methods (modified two-step overlay/Enterococcosel agar [OV/EA], OV/bile esculin azide agar [OV/BEA], thin agar layer/EA [TAL/EA], and TAL/BEA) were not selected for enumeration of presumptive indigenous enterococci from heat-treated turkey litter compost. As shown in Table 2, EA and OV/EA-R were selected to enumerate the heat-injured presumptive indigenous enterococci and E. faecium, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Comparing media for recovering heat-injured E. faecium NRRL B-2354 in turkey litter compost under laboratory conditions

| Recovery medium |

E. faecium population (log CFU g−1) after exposure to 75°C for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | |

| EA-R | 8.2 ± 0.1Aa | 4.0 ± 0.3C | <2b |

| BEA-R | 7.3 ± 0.8B | 3.3 ± 0.2D | <2 |

| OV/EA-R | —c | 5.1 ± 0.3A | <2 |

| OV/BEA-R | — | 4.7 ± 0.5B | <2 |

| TAL/EA-R | — | 4.8 ± 0.2B | <2 |

| TAL/BEA-R | — | 4.2 ± 0.8C | <2 |

Data are expressed as means ± SD from three trials. Means with different letters in the same column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Detection limit is <2 log CFU g−1.

—, not tested.

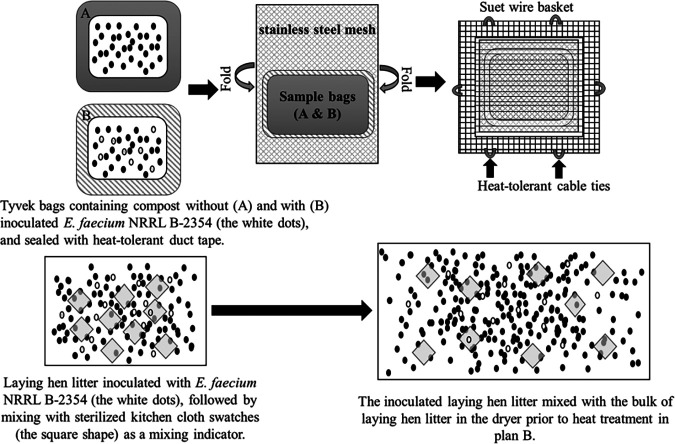

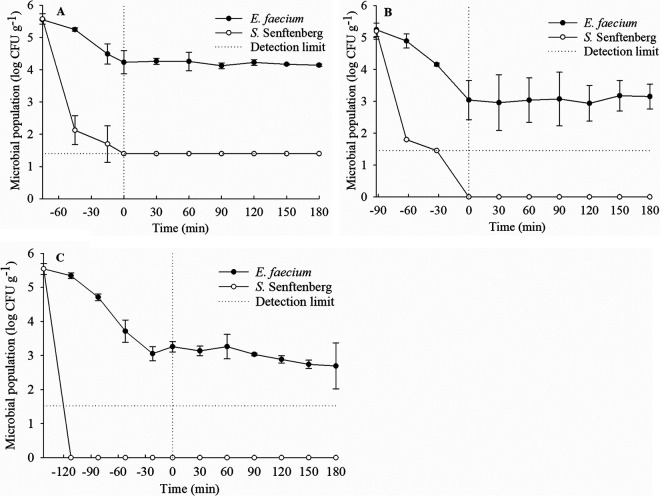

To reduce the uncertainty during processing plant-scale studies, laboratory-based studies were performed first to compare the thermal resistance of desiccation-adapted E. faecium and desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W in both turkey litter and laying hen litter composts. No Salmonella was detected from the received compost samples. For the laboratory-based study, the come-up times for heating turkey litter compost with 20, 30, and 40% moisture content and laying hen litter compost with 15% moisture content at 75°C were 75, 92, 142, and 60 min, respectively. The population reductions of desiccation-adapted E. faecium were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than those of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W under all the tested conditions (Fig. 1). At 75°C, the log reductions of desiccation-adapted E. faecium in the turkey litter compost with 20, 30, and 40% moisture content were 1.4, 2.1, and 2.9 log CFU g−1, respectively, after come-up times and holding for 180 min, whereas desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W was detected by enrichment only (with a 4.2-log reduction) in the turkey litter compost with 20% moisture content during holding times (Fig. 1A). More than a 5-log reduction of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W was achieved during come-up times of 90 and 120 min in the samples with 30 and 40% moisture contents, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). At 150°C, desiccation-adapted E. faecium survived for up to 15 min in the turkey litter compost with 20% moisture content, whereas it was not detectable for other moisture contents (data not shown). However, desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W could not be detected in the turkey litter compost with all moisture contents exposed to 150°C within 15 min (data not shown). In the laying hen litter compost with ca. 15% moisture content (Fig. 2), a 1.5-log reduction of desiccation-adapted E. faecium was detected after a come-up time of 60 min at 75°C, compared with a >5-log reduction of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W. During the holding time, cell counts of desiccation-adapted E. faecium were still more than 4 log CFU g−1 in the laying hen litter compost after exposure to 75°C for 180 min, whereas Salmonella cells were not detected by enrichment after 90 min.

FIG 1.

Survival of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium NRRL B-2354 in turkey litter compost with 20% (A), 30% (B), and 40% (C) moisture contents at 75°C. Inactivation curves during come-up times (to the left of the vertical dotted line) and during holding times (to the right of the vertical dotted line) are shown. The horizontal dotted line indicates that Salmonella was detectable only by enrichment (detection limit by direct plating, 1.3 log CFU g−1). Data are averages of values from two trials.

FIG 2.

Survival of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium NRRL B-2354 in laying hen litter compost with 15% moisture content at 75°C. Inactivation curves during come-up times (to the left of the vertical dotted line) and during holding times (to the right of the vertical dotted line) are shown. The horizontal dotted line indicates that Salmonella was detectable only by enrichment (detection limit by direct plating, 1.3 log CFU g−1). Data were expressed from the average of two trials.

Taken together, the thermal inactivation effect on both desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium was found to be enhanced with the increase in moisture content of poultry litter compost in the laboratory validation study. This finding was in line with our previously published laboratory-scale studies on the physical heat treatment of Salmonella spp. and its surrogate microorganism in broiler chicken litter compost (19, 22). Based on the laboratory validation studies, reductions of 1.2 to 2.7 logs or more of E. faecium can predict >5-log reductions of S. Senftenberg 775/W in poultry litter compost, depending on heating temperature, moisture content, and types of poultry litter compost. In short, findings from laboratory studies indicated that E. faecium can be used as a surrogate for Salmonella to provide a sufficient safety margin when validating the thermal processing in industrial settings.

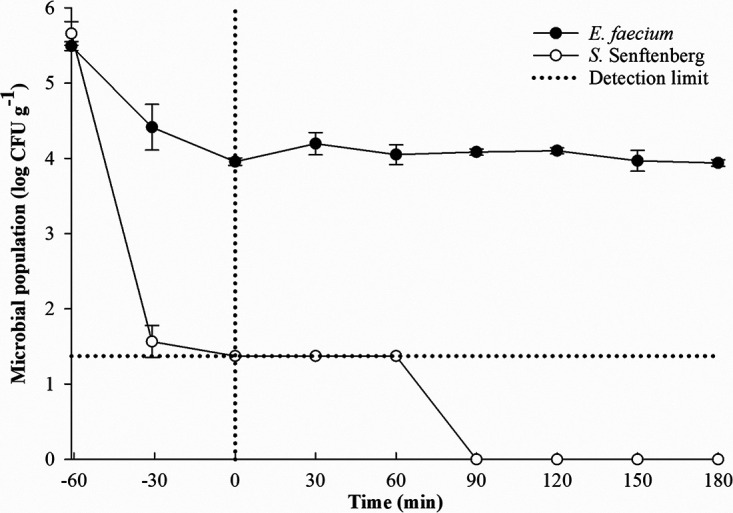

Sampler design and residence time determination.

To ensure the inoculated compost samples could be processed through the industrial dryer in plant A and subsequently collected postdrying, a sampler was designed to hold the turkey litter compost. To secure the sampler, the suet-wire basket was held tightly with heat-tolerant cable ties (Fig. 3). The sampler is easy to assemble on site and, thus, can be used as a suitable validation tool in industrial settings. For plant A, the residence times for the winter trial (44% moisture content), spring trial (36% moisture content), and summer trial (36 and 44% moisture contents) were 28 to 198, 23 to 72, 26 to 60, and 25 to 59 min, with the median resident time being 51, 45, 43, and 35 min, respectively, as measured by running the sampler through the dryer.

FIG 3.

Custom-designed sampler (top) and the inoculation procedure for plant B (bottom).

To our knowledge, only pilot-scale models have been reported so far for animal waste process validation (23, 24), and for all previous pilot-scale studies on physical heat treatment of animal wastes, only pig slurry with a maximum capacity of 220 liters/h was studied using indigenous microorganisms (25). Compared to those pilot-scale studies, both heat transfer and compost flow are difficult to control in an industrial processing line. As such, the custom-designed samplers were used as a validation tool by holding compost samples intact during thermal processing in the industrial dryer for the subsequent plant validation studies.

Plant-scale validation of physical heat treatment of poultry litter compost using indicator microorganisms.

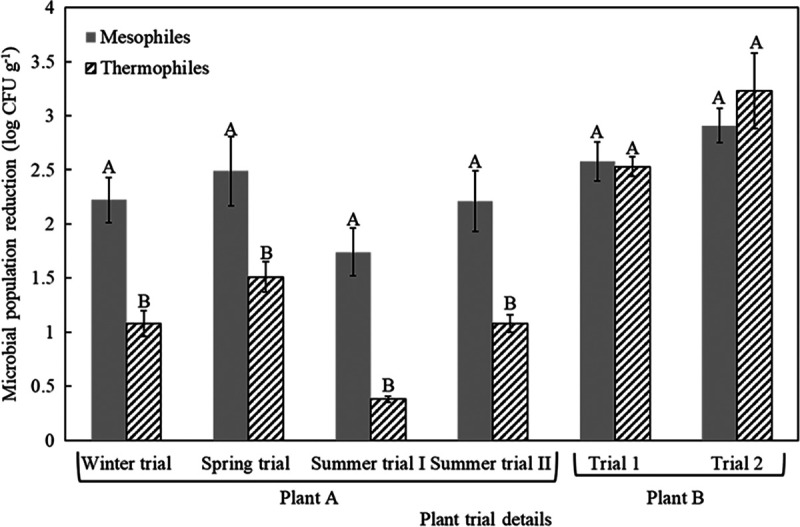

The thermal inactivation rate of presumptive indigenous enterococci was found to have a correlation with that of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W in broiler litter with different moisture contents when subjected to heat treatment under laboratory conditions (11). Therefore, our intent in this study was to use enterococci, mesophiles, and thermophiles as potential indicator microorganisms to determine the thermal inactivation rates of indigenous microorganisms in industrial settings. Reductions of indicator microorganisms in plant A are presented in Table 3. An average of a >3-log reduction of presumptive indigenous enterococci from four trials was found in both uninoculated samples in Tyvek bags and the turkey litter compost collected from the processing line. Average population reductions of indigenous mesophiles and thermophiles in processing control samples were 2.2 and 1.1, 2.5 and 1.5, 1.7 and 0.4, and 2.2 and 1.1 log CFU g−1 for the winter trial (44% moisture content), the spring trial (36% moisture content), the summer trial 1 (36% moisture content), and the summer trial 2 (44% moisture content), respectively (Fig. 4).

TABLE 3.

Inactivation of desiccation-adapted E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and presumptive indigenous enterococci in turkey litter compost after processing through industrial dryer in plant Aa

| Season (date, mo/yr) | Target moisture content (%) | nb | Before dryer |

After dryer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture content (%) | E. faecium (log CFU g−1) | Presumptive indigenous enterococcid (log CFU g−1) | Moisture content (%) | E. faecium (log CFU g−1) | Presumptive indigenous enterococci (log CFU g−1) | |||

| Winter (11/2016) | 44 | 11 | 43.8 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 32.3 ± 12.1 | +e/− (1/11) | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| Process control | 51.2 ± 2.3 | NAc | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | NA | 2.3 ± 0.1 | ||

| Spring (4/2017) | 36 | 10 | 36.4 ± 1.0 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.0 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | —f | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| Process control | 28.7 ± 4.0 | NA | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | NA | 1.8 ± 0.2 | ||

| Summer 1 (6/2017) | 36 | 12 | 35.2 ± 1.1 | 7.7 ± 0.0 | 5.7 ± 0.0 | 20.5 ± 0.6 | +/− (1/12) | 1.8 ± 0.0 |

| Process control | 29.9 ± 6.2 | NA | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | NA | 1.8 ± 0.0 | ||

| Summer 2 (7/2017, 8/2017) | 44 | 12 | 41.8 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 21.9 ± 0.4 | — | 1.7 ± 0.0 |

| Process control | 36.1 ± 3.6 | NA | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | NA | 1.6 ± 0.0 | ||

Two runs were conducted for each plant trial, and the data are expressed as means ± SD.

Number of samples collected from the dryer.

NA, not applicable.

Enterococcal counts were enumerated on EA plates.

+, detected by enrichment. The detection limit of directly plating was 1.3 log CFU/g by dry weight.

—, not detected by enrichment.

FIG 4.

Average log reduction of mesophiles and thermophiles in the processing control samples during heat treatment in plants A and B.

For plant B, the initial population level of presumptive indigenous enterococci in the laying hen litter compost was lower than that in the turkey litter compost of plant A. After physical heat treatment of laying hen litter compost in plant B, the population of presumptive indigenous enterococci was reduced >1.8 log CFU g−1 in the processing control samples (Table 4), whereas mesophiles and thermophiles were reduced by 2.6 and 2.5, 2.9 and 3.2 log CFU g−1 for trials 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 4). Variations in the initial populations of indigenous microorganisms in incoming poultry litter compost were observed among trials in both plants.

TABLE 4.

Inactivation of desiccation-adapted E. faecium NRRL B-2354 and presumptive indigenous enterococci in laying hen litter compost after processing through industrial dryer in plant B

| Plant run | Before dryer |

After dryer |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture content (%) | na | E. faeciumb (log CFU g−1) | Presumptive indigenous enterococcid (log CFU g−1) | Moisture content (%) | nf | E. faeciumg (log CFU g−1) | Presumptive indigenous enterococcih (log CFU g−1) | |

| Trial 1 | 6.4 ± 0.0 | 2 | 4.5 ± 0.0 | NCe | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 10 | <1.4 ± 0.3 | NC |

| Process control | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 2 | NAc | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | 2 | NA | <1.3 |

| Trial 2 | 6.2 ± 0.0 | 2 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | NC | 4.8 ± 0.0 | 10 | <1.7 ± 0.3 | NC |

| Process control | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 2 | NA | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | 2 | NA | <1.3 |

The number of samples shipped/collected before each plant trial run.

Expected initial surrogate population prior to dryer, calculated based on mixing ratio before dryer in plant B.

NA, not applicable.

Enterococcal counts were enumerated on EA plates.

NC, no data collected.

Number of samplers collected from the dryer.

From two trials, 3 out of 20 samples were positive for E. faecium by direct plating, whereas the other samples were detected only by enrichment.

Presumptive indigenous enterococci were not detected by directly plating after heat treatment, and the detection limit of direct plating was 1.3 log CFU g−1 by dry weight.

Due to the variable populations of indigenous microflora and heterogeneous compost ingredient in poultry litter compost, multiple microbial indicators, such as enterococci, mesophiles, or thermophiles, could be used to represent a wide spectrum of pathogens existing in compost that have different levels of heat resistance. In agreement with this assumption, Cunault et al. (23) used a set of indigenous microorganisms, including naturally occurring E. coli, enterococci, spore-forming sulfite-reducing Clostridia (SRC), and indigenous mesophiles (MCB), as indicators to assess the effectiveness of the thermal treatment of pig slurry. They reported that a continuous heat treatment at 55 or 60°C for 10 min can reduce indigenous E. coli by 4 or 5 logs, whereas a longer heat treatment at these temperatures was needed to kill enterococci, and indigenous SRC was more heat resistant than enterococci in pig slurry treated at 96°C for 10 min. Although there is no study on industrial plant-scale validation, many laboratory-based studies have also reported the use of different indigenous microflora, including fecal Streptococcus, Enterococcus spp., and E. coli, as indicator microorganisms to determine the survival behaviors of bacterial pathogens during animal waste composting or wastewater treatment (26–28). In the present study, thermal inactivation of indigenous microorganisms depended on the time-temperature combinations and types of poultry litter compost. In consideration of the low cost to enumerate presumptive indigenous enterococci, the processors could do routine monitoring of their thermal process by using indigenous microorganisms as indicators for Salmonella.

Plant-scale validation of physical heat treatment of poultry litter compost using surrogate microorganisms.

In addition to indicator microorganisms, surrogates could also be an alternative for predicting the survival characteristics of pathogens in plant-scale studies. Due to the fluctuation of presumptive indigenous enterococcal populations in animal wastes, the use of spiked E. faecium should be considered for validation purpose. As shown in Table 3, only two samples were positive for E. faecium after enrichment, which were obtained from the samplers exiting from the dryer with the shortest residence times (36 and 28 min, respectively) for the winter trial with 44% moisture content and the summer trial with 36% moisture content, respectively. During the second summer trial with 36% moisture content, there was an 8-min shutdown of the drying process due to a power outage, which might have interfered with the normal movement of samplers inside the dryer and heat treatment.

In plant B, the initial moisture content of the laying hen litter compost was ca. 17%, and the initial inoculum level of E. faecium was 8.9 log CFU g−1. The E. faecium population decreased by ca. 2 log CFU g−1 during the 48-h desiccation adaptation at room temperature. For plant B validation, ca. 2.46 kg compost spiked with desiccation-adapted E. faecium was mixed with one batch of compost (ca. 680 kg), resulting in a ratio of approximately 1:280 (Fig. 3). Two separate trials were performed with 4.5 log CFU g−1 as the average target population of desiccation-adapted E. faecium in laying hen litter compost before heat treatment. After heat processing (ca. 99.4°C for 7 min), the cloth swatches (mixing indicators) were found to be well distributed, indicating a homogeneous mixing of laying hen litter compost mixing during the drying process. E. faecium was detected by direct plating in 3 out of 20 samples and by enrichment in 14 out of 20 samples. In summary, our data showed that an average >2.8- to 3.1-log reduction in surrogate microorganism was achieved after heat treatment in plant B in both trials (Table 4).

Based on the results from the plant validation studies, we confirmed the suitability of using desiccation-adapted E. faecium as a surrogate for desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W when validating physical heat treatment of poultry litter compost. After a slight decrease in the populations of E. faecium in poultry litter compost during shipping, the desiccation-adapted E. faecium populations were found to be maintained at a stable level before heat treatment, which met the requirements that the ideal surrogate should be easy to yield at a high-density level with constant population until utilized (21, 29). After physical heat treatment in the plants, the log reduction of desiccation-adapted E. faecium can predict a >5-log reduction of desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W in poultry litter compost sources from two plants based on the results produced from laboratory validation studies.

Correlation between physicochemical changes and microbial reductions after industrial heat treatments.

In our previous laboratory-based study, E. faecium was more sensitive to high temperature in a relatively wet environment, as indicated by its declining heat resistance with increased moisture content of broiler litter during thermal processing (22). Heat transfer could be more efficient in the poultry litter compost with lower moisture content (20), suggesting that other physicochemical characteristics of poultry litter compost also affect the heat resistance of bacteria during heat treatment. For example, during chicken manure composting, the inactivation rates of Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes in the compost with 20:1 C:N formulations were higher than those in 30:1 and 40:1 formulations (30). As mentioned above, in addition to moisture level in compost and processing temperature, the physicochemical characteristics of poultry litter compost could be another important factor affecting the population reductions of indicator and surrogate microorganisms during heat treatments.

In this study, the physicochemical characteristics of turkey litter compost from plant A were significantly different (P < 0.05) from those of plant B, except for the carbon value (Table 5). Based on the correlation analysis for the compost samples collected from two plants, there were no noticeable correlations between most of the nutrient contents (total nitrogen, carbon, C:N, and organic matter) of poultry litter compost and microbial population reduction due to heat exposure in two industrial dryers. The changes in pH of poultry litter compost were strongly correlated with the reductions in indigenous mesophiles, thermophiles, and enterococci, with correlation coefficient values (ρ) greater than 0.7 (data not shown). Most importantly, pH changes were significantly (P = 0.049) negatively correlated with thermophile reduction but positively correlated with enterococcus reduction (P = 0.017), indicating thermophiles were inactivated more at lower pH and enterococci were inactivated more at higher pH.

TABLE 5.

Chemical-physical characteristics of poultry litter compost of two plants

| Sample (season, mo/yr) | Total nitrogen (%) | Carbon (%) | C/N ratio (%) | Organic matter (%) | ECb (mmho cm−1) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before heat treatment | ||||||

| Plant A (winter, 11/16) | 3.2 ± 0.1a | 30.4 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.2 | 58.0 ± 0.3 | 29.7 ± 1.0 | 8.5 ± 0.0 |

| Plant A (spring, 4/2017) | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 34.0 ± 0.0 | 8.4 ± 0.0 | 63.5 ± 0.4 | 21.4 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 0.0 |

| Plant A (summer 1, 6/2017) | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 25.8 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 48.6 ± 5.3 | 12.4 ± 1.7 | 8.8 ± 0.3 |

| Plant A (summer 2, 7/2017 and 8/2017) | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 26.8 ± 1.8 | 9.2 ± 0.0 | 54.5 ± 4.6 | 12.5 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 0.0 |

| Avg for plant A | 3.2 ± 0.6A | 29.2 ± 3.7A | 9.1 ± 0.5A | 55.4 ± 6.7A | 19.0 ± 8.3A | 8.4 ± 0.5A |

| Plant B (Dec/2017) | 6.0 ± 0.9B | 28.9 ± 0.7A | 5.2 ± 0.1B | 50.4 ± 1.2B | 11.9 ± 0.4B | 6.1 ± 0.0B |

| After heat treatment | ||||||

| Plant A (winter, 11/2016) | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 37.4 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.0 | 61.9 ± 2.4 | 35.3 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.0 |

| Plant A (spring, 4/2017) | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 34.8 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.1 | 64.6 ± 0.6 | 20.7 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 0.0 |

| Plant A (summer 1, 6/2017) | 2.8 ± 0.0 | 25.3 ± 1.4 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 47.8 ± 0.5 | 13.6 ± 0.9 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| Plant A (summer 2, 7/2017 and 8/2017) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 23.6 ± 1.8 | 8.4 ± 0.0 | 44.4 ± 1.7 | 11.6 ± 1.0 | 8.2 ± 0.5 |

| Avg for plant A | 3.6 ± 1.0A | 30.3 ± 6.8A | 8.5 ± 0.7A | 54.7 ± 10.0A | 20.3 ± 10.7A | 7.3 ± 0.6A |

| Plant B (Dec/2017) | 5.7 ± 0.1B | 28.5 ± 5.0A | 5.000.1A | 47.8 ± 1.4B | 11.8 ± 0.4B | 6.1 ± 0.0B |

Data are expressed as means ± SD from two samples. Means with different letters in the same column are significantly different (P < 0.05). The values of nutrients and metals are all calculated based on dry weight.

EC, electrical conductivity.

Unexpectedly, in plant A, the moisture content of turkey litter compost had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on the reductions of the surrogate microorganism. It should be noted that processing plants only process poultry litter compost with a narrow range of moisture content. According to the information provided by plant A, the moisture content of turkey litter compost averaged at 36% with a range of 30 to 50%. For plant B, the E. faecium population in the laying hen litter compost with 15% moisture content was less reduced after heat treatment compared to the higher moisture turkey litter compost with 36 and 44% moisture contents from plant A. This can be explained by the increased heat resistance of microorganisms in the dry matrix (31). As such, the slight difference between the two moisture contents used in plant A trials would not allow the surrogate microorganism to produce a significant change in heat resistance. Further, although the design of the Tyvek bags allowed the free movement of moisture during heat processing, there was less moisture reduction when compost samples were contained inside the sealed Tyvek bags. Nonetheless, in the processing control samples, the reductions of indicator microorganisms were significantly (P < 0.05) affected by the moisture content, as the highest enterococcal cell reduction (3.7 log CFU g−1) was achieved in the processing control compost samples with the highest moisture content (51.2%). Therefore, the use of indicator microorganisms may have the added advantage of reflecting changes in the properties of litter compost during heat processing compared to surrogate microorganisms.

As discussed above, although a laboratory-based study on the same source compost samples was performed before the plant validation studies, the environment in a plant certainly cannot be controlled as ideally as that under laboratory conditions. Therefore, it is important to apply the laboratory findings to real-world use by thoroughly assessing the effectiveness of physical heat treatment processes in an industry setting. When scaling up a physical heat treatment to a processing plant, the homogeneity and the flow of poultry litter compost in the larger industry dryer should be controlled to ensure uniform heating of litter compost (4). Thus, the custom-designed sampler was able to hold compost samples and surrogate microorganisms intact during the heating processing in the rotary dryer. Moreover, when designing the plant validation studies, it is important to take into consideration the industrial settings, such as dryer specifications, type of heat treatment, the handling of incoming poultry litter, and the preparation of surrogate microorganisms.

Implementation of validation study.

Moving from laboratory to plant validation studies, physical heat treatments in both processing plants have been scientifically validated as an effective way to reduce potential Salmonella contamination in poultry litter compost, which is in line of the FSMA’s recommendation of using alternative treatments for reducing or eliminating human pathogens in untreated BSAAO before land application (5). As indicated in the biosolids technology fact sheet published by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), the dryers used in the participating plants were the most important and common types used for drying biosolid waste in the United States (32). The validation methods optimized in our research can be applied to other animal waste-processing plants and provide scientific evidence for complying with FSMA requirements to produce biological soil amendments safely.

Limitations of this study.

There are some limitations to our plant validation studies. Due to the dryer structures of the plants, only endpoint samples could be collected. Although many specifications of the dryers were known, some real-time processing data, including come-up times, internal temperature profiles, and movement of samples, were not available. Therefore, future studies on the validation of thermal processing using poultry litter compost with various physicochemical properties under industrial settings are necessary.

Conclusions.

In summary, the thermal processes of two poultry litter compost processing plants under different processing conditions were successfully validated using E. faecium and presumptive indigenous enterococci. Even though the processing conditions in these processing plants varied greatly, the validation results indicated that Salmonella levels, if present, could be reduced by at least 5 logs based on the reductions of surrogate and indicator microorganisms. The designed sampler could withstand the harsh environments created by high temperatures and strong tumbling movement inside the industrial dryers and served as a carrier for the inoculated poultry litter or poultry litter compost samples exposed to the thermal process in the industry setting. Therefore, both indicator and surrogate microorganisms along with the sampler can serve as practical tools for poultry litter compost processors to routinely monitor and validate their thermal processes without introducing pathogens into the industrial environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Salmonella enterica Senftenberg 775/W (ATCC 43845) was used as a reference strain in the laboratory validation study, as it was identified as the most heat resistant among four Salmonella strains tested during thermal processing of aged broiler litter in our previous laboratory-scale study (19). E. faecium NRRL B-2354 (ATCC 8459) was evaluated as a potential Salmonella surrogate for both laboratory and plant validation studies. Both strains were induced to rifampin resistance (100 μg ml−1) using the gradient plate method (33). Each strain was grown overnight at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) containing 100 μg rifampin ml−1 (TSB-R). The overnight cultures were then washed three times and resuspended with sterile 0.85% saline to the desired cell concentrations by measuring the optical density at 600 nm. S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium were enumerated using xylose-lysine-tergitol-4 agar (XLT-4; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) and Enterococcosel agar (EA; Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD), respectively, supplemented with 100 μg rifampin ml−1 (XLT-4-R and EA-R).

Selection of the recovery media for heat-injured E. faecium and presumptive indigenous enterococci using turkey litter compost.

The turkey litter compost adjusted to 30% moisture content (water activity [aw] = 0.925) with sterilized tap water was inoculated with overnight-grown E. faecium cells at a ratio of 1:100. The temperature of a controlled convection oven (Binder, Inc., Bohemia, NY) was initially set at 80°C. When the oven temperature reached 80°C, sealed Tyvek pouches (12.7 by 12.7 cm) containing 50 g turkey litter compost samples with or without E. faecium were placed on the oven shelf at the middle location and then exposed to the heat treatment for 60 min. The temperature was monitored constantly using T-type thermocouples (DCC Corporation, Pennsauken, NJ), with one cord kept inside the oven chamber and other cords kept in the compost samples. When the interior of the compost reached the desired temperature (75°C), the temperature setting of the oven was readjusted to maintain this designated temperature. Samples were taken out at 30 and 60 min of heat exposure and were transferred into a sterile Whirl-Pak bag (700 ml; Nasco, Inc., Madison, WI) and placed immediately in an ice water bath to stop further cell death. Samples were then serially diluted with 0.85% saline and plated in duplicate as described below to evaluate the recovery efficiency with these media.

Tryptic soy agar (TSA; Becton, Dickinson and Company) was used as a nonselective medium, whereas EA and bile esculin azide agar (BEA; Becton, Dickinson and Company) were used as selective media for enterococci. EA and BEA supplemented with rifampin (100 µg ml−1) were used for E. faecium. Using EA or BEA alone, a modified two-step overlay (OV) method with heat-injured cells plated directly onto TSA and a modified thin agar-layer (TAL) method were compared for the recovery of heat-injured presumptive indigenous enterococcal cells and E. faecium. For OV methods, after incubation at 37°C for 2 h to allow the recovery of injured cells, 7 ml of BEA or EA was overlaid onto TSA (OV/BEA and OV/EA). Plates were incubated at 37°C for another 22 h, whereas for TAL methods, 14 ml of melted TSA (48°C) was overlaid (TAL/BEA and TAL/EA). Heat-injured cells were plated onto TAL medium and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Thermal inactivation study under laboratory conditions.

The turkey litter compost with 6 months of aerobic thermophilic stabilization (plant A) and laying hen litter compost (plant B) were used to evaluate E. faecium as a surrogate for validating thermal processes under laboratory conditions. All composts were dried under the fume hood until moisture content was reduced to less than 20% and then screened to a particle size of less than 3 mm using a sieve. Sufficient compost samples were collected for all laboratory experiments and stored in a sealed container at 4°C until use.

The moisture contents of different poultry litter composts were adjusted with sterilized tap water based on the moisture range of incoming poultry litter compost processed in both plants, i.e., 30 to 50% for the turkey litter compost received from plant A and 15% for the laying hen litter compost from plant B. Desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium cultures were prepared as described previously by Wang et al. (22). Following the 24-h desiccation adaptation, the compost with desiccation-adapted cells was further mixed with compost with the same moisture content at a ratio of 1:100 using a sterile blender (KitchenAid, Inc., St. Joseph, MI) to the target final concentration of desiccation-adapted cells. In brief, both desiccation-adapted S. Senftenberg 775/W and E. faecium were inoculated into the turkey litter compost, adjusted to 20, 30, or 40% moisture content, and into the laying hen litter compost with 15% moisture content, respectively, at a final concentration of ca. 5 log CFU g−1. Twenty-gram samples of compost in duplicate were distributed evenly inside a sterile aluminum pan (inner diameter, 10 cm). When the oven temperature reached the set temperature (5°C higher than the target temperature), the aluminum pans with inoculated samples were placed on the oven shelf at two different locations. According to treatment temperatures in each plant, temperatures used were 75 and 150°C for turkey litter compost and 75°C for laying hen litter compost. Thermal inactivation experiments were performed as described above. For heat treatments at 75°C, compost samples were withdrawn from the oven at 0 min and every 30 min during the come-up time and holding time (up to 180 min) for determining microbial populations. For heat treatment at 150°C, duplicate samples were withdrawn every 15 min up to 60 min.

Specifications of industrial dryers.

Two poultry litter compost processors were involved in the plant validation studies: one turkey litter compost processor (plant A) in the midwestern United States and one laying hen litter compost processor (plant B) in the southwestern United States. Specifically, plant A processes turkey litter compost with 6 months of aerobic thermophilic stabilization, whereas plant B processes composted chicken manure mixed with the bone meal (laying hen litter compost). Although the dryers in both plants can bring the treatment temperature to >65°C and can be operated at a 13- to 22-rpm rotation rate, the dryer in plant A was operated continuously and the dryer in plant B was batch operated. The detailed specifications of industrial dryers are listed in Table 1.

Sampler design.

Based on our previous composting-related studies and heat tolerance tests, a Tyvek bag was used to hold the poultry litter compost, which allowed moisture transfer but no sample leakage. To protect the Tyvek bag from being broken up by stones and other sharp objects mixed in compost during drying inside the dryer, sampler systems were designed and tested in plant A (Fig. 3). 3Initially, three sampler prototypes (tea infuser, mesh cylinder, and suet wire basket) were tested in plant A. All prototypes were retrieved immediately from the knockout unit (for trapping the stones) after the dryer. Both the tea infuser and mesh cylinder were torn apart, whereas the suet wire basket (14.22 by 12.19 by 4.57 cm; C&S Products, Co., Inc., Fort Dodge, IA) remained intact. By adding stainless steel mesh (2-mm hole; 13.97 by 15.24 by 2.54 cm) as the liner inside the basket, the Tyvek bag remained intact after passing through the dryer at least twice.

Sample preparation for plant validation.

One week before each plant trial, poultry litter compost samples were obtained from each processor. The rifampin-resistant E. faecium was used as the surrogate microorganism for the plant validation study. The overnight culture was washed and then added to the turkey litter compost (plant A) or laying hen litter compost (plants B) at a rate of 1:100, vol wt−1, to a final concentration of ca. 7 log or ca. 9 log CFU g−1, respectively, and both were adjusted to the desired moisture content (within the moisture range of compost from each plant). For plant A, about 50 g of inoculated turkey litter compost was packed into each Tyvek pouch (12.7 by 12.7 cm) with all sides reinforced with heat-tolerant tape. Two Tyvek pouches, one inoculated and one uninoculated, were placed into one customized sampler as described above. For plant trials conducted at plant B, instead of using a sampler, sterilized polyester kitchen cloth swatches (2.54 by 2.54 cm, ca. 80 pieces for each trial, with ca. 20% moisture content) were mixed with ca. 2.46 kg of inoculated laying hen litter compost (ca. 15% moisture content, each trial) to serve as indicators for the mixing and progression through the cooker (residence time) in plant B (Fig. 3). Afterward, all prepared samplers for plant A and the inoculated laying hen litter compost for plant B were shipped overnight at room temperature to plants A and B, respectively, allowing bacterial cells to be desiccation adapted in the compost during shipping. Tyvek bags containing poultry litter compost with or without being inoculated with E. faecium, in duplicate, served as shipment controls for each trial.

Sample collection and analysis.

For trials in plant A, samplers were retrieved at the exit end of the dryer after being dropped into the entry of the dryer. The residence time for each sampler was recorded. Compost samples before and after heat treatment were also collected from the processing line to serve as process controls. For each trial performed in plant B, process control samples were taken from the dryer before the addition of inoculated samples. About 2.46 kg of laying hen litter compost (ca. 15% moisture content) with desiccation-adapted E. faecium were mixed with the bulk of compost (ca. 680 kg per run) in the dryer before heat treatment. After each test run, the distribution of the kitchen cloth swatches from the catch bin was observed to determine if the inoculated sample was sufficiently mixed. Meanwhile, 12 samples from different representative locations of the catch bin were collected for sample analysis. Two separate test runs were conducted sequentially for each trial. All collected samples, including the shipment controls, were shipped overnight with cold packs back to Clemson University, SC, and analyzed immediately.

Bacterial enumeration.

The surviving S. Senftenberg 775/W cells were enumerated using a modified two-step overlay method (OV/XLT-4-R) to allow heat-injured cells to resuscitate (19). The surviving E. faecium cells were enumerated using the recovery media (EA-R). The samples that were presumptively negative for S. Senftenberg 775/W by the direct plating method (detection limit, 1.3 log CFU g−1) were screened for Salmonella by following the microbiological detection method described by the U.S. FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual (34). The samples that were presumptively negative for E. faecium by the direct plating method were preenriched in brain heart infusion broth (BHI) supplemented with 100 μg rifampin ml−1 at 37°C for 24 h, followed by plating onto EA-R. Both the turkey litter compost and laying hen litter compost samples were analyzed for indigenous microorganisms, including presumptive enterococci, mesophiles, and thermophiles, and screened for Salmonella based on the methods described in the U.S. FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual (34). For plant A, the indigenous microorganisms were enumerated from both the compost sample without inoculation of E. faecium in the sampler and the compost sample collected from the processing line. For plant B, the inoculated compost was added onsite before the thermal process; therefore, to exclude the interference from the inoculated E. faecium, the indigenous microorganisms were enumerated from the sample collected from the processing line only (prior to the inoculation of E. faecium).

Chemical and physical characteristic analysis.

Moisture content was measured with a moisture analyzer (model IR-35; Denver Instruments, Denver, CO). Water activity (aw) was measured with a dew-point aw meter (Aqualab Series 3TE; Decagon Devices, Pullman, WA). The pH and electrical conductivity values of poultry litter compost were measured by a multiparameter benchtop meter (Orion VERSA Star meter; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Fort Collins, CO, USA) according to the test methods described by the U.S. Composting Council (35). Duplicate samples were analyzed by the Clemson University Agricultural Service Laboratory for chemical characteristics, including nutrients and heavy metals (total concentrations, including water-soluble and water-insoluble concentrations).

Statistical analysis.

Plate counts were converted to log number of CFU per gram in dry weight. SigmaPlot 12.3 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) was used for data analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test, was carried out to determine whether significant differences (P < 0.05) existed among different treatments. In this study, a P value of <0.05 was used to indicate strong evidence against the null hypothesis or a statistically significant result. The Spearman’s rank-order correlation was calculated using RStudio 1.1.463 (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) to determine the strength of association between changes in chemical-physical properties and microbial reductions in poultry litter compost during plant validation studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our industrial collaborators for providing the poultry litter compost samples and supporting the plant validation studies and Mengzhe Li at the Ocean University of China for assisting us on sample analysis.

This research was financially supported by the Center for Produce Safety, CA, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service through grant 15SCBGP-CA-0046. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USDA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ritz CW, Merka WC. 2009. Maximizing poultry manure use through nutrient management planning. https://athenaeum.libs.uga.edu/handle/10724/12463. Accessed December 2019.

- 2.United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service National Organic Program. 2011. Processed animal manures in organic crop production. https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/5006.pdf. Accessed December 2019.

- 3.Leafy Green Marketing Agreement Advisory Board. 2016. Commodity specific food safety guidelines for the production and harvest of lettuce and leafy greens. https://www.wga.com/sites/default/files/resource/files/California%20LGMA%20metrics%2001%2029%2016%20Final.pdf. Accessed November 2019.

- 4.Chen Z, Jiang X. 2017. Microbiological safety of animal wastes processed by physical heat treatment: an alternative to eliminate human pathogens in biological soil amendments as recommended by the Food Safety Modernization Act. J Food Prot 80:392–405. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clements D, Acuña-Maldonado L, Fisk C, Stoeckel D, Wall G, Woods K, Bihn E. 2019. FSMA Produce Safety Rule: documentation requirements for commercial soil amendment suppliers. https://ucanr.edu/sites/Small_Farms_/files/315707.pdf. Accessed February 2020.

- 6.Harris LJ, Berry ED, Blessington T, Erickson M, Jay-Russell M, Jiang X, Killinger K, Michel FC, Millner P, Schneider K, Sharma M, Suslow TV, Wang L, Worobo RW. 2013. A framework for developing research protocols for evaluation of microbial hazards and controls during production that pertain to the application of untreated soil amendments of animal origin on land used to grow produce that may be consumed raw. J Food Prot 76:1062–1084. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Côté C, Massé DI, Quessy S. 2006. Reduction of indicator and pathogenic microorganisms by psychrophilic anaerobic digestion in swine slurries. Bioresour Technol 97:686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi G, Pan Z, Sugawa Y, Andriamanohiarisoamanana FJ, Yamashiro T, Iwasaki M, Kawamoto K, Ihara I, Umetsu K. 2018. Comparative fertilizer properties of digestates from mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion of dairy manure: focusing on plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) and environmental risk. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 20:1448–1457. doi: 10.1007/s10163-018-0708-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham JP, Price LB, Evans SL, Graczyk TK, Silbergeld EK. 2009. Antibiotic resistant enterococci and staphylococci isolated from flies collected near confined poultry feeding operations. Sci Total Environ 407:2701–2710. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal S, Dhull SK, Kapoor KK. 2005. Chemical and biological changes during composting of different organic wastes and assessment of compost maturity. Bioresour Technol 96:1584–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z, Jiang X. 2017. Selection of indigenous indicator microorganisms for validating desiccation-adapted Salmonella reduction in physically heat-treated poultry litter. J Appl Microbiol 122:1558–1569. doi: 10.1111/jam.13464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceylan E, Bautista DA. 2015. Evaluating Pediococcus acidilactici and Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 as thermal surrogate microorganisms for Salmonella for in-plant validation studies of low-moisture pet food products. J Food Prot 78:934–939. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkitasamy C, Zhu C, Brandl MT, Niederholzer FJ, Zhang R, McHugh TH, Pan Z. 2018. Feasibility of using sequential infrared and hot air for almond drying and inactivation of Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354. LWT Food Sci Technol 95:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.04.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borowski AG, Ingham SC, Ingham BH. 2009. Validation of ground-and-formed beef jerky processes using commercial lactic acid bacteria starter cultures as pathogen surrogates. J Food Prot 72:1234–1247. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.6.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams P, Leong WM, Ingham BH, Ingham SC. 2010. Lethality of small-scale commercial dehydrator and smokehouse/oven drying processes against Escherichia coli O157:H7-, Salmonella spp.-, Listeria monocytogenes-, and Staphylococcus aureus-inoculated turkey jerky and the ability of a lactic acid bacterium to serve as a pathogen surrogate. Annu Meet Inst Food Technologists, Chicago, IL, 17 to 20 July 2010.

- 16.Jeong S, Marks BP, Ryser ET. 2011. Quantifying the performance of Pediococcus sp. (NRRL B-2354: Enterococcus faecium) as a nonpathogenic surrogate for Salmonella Enteritidis PT30 during moist-air convection heating of almonds. J Food Prot 74:603–609. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchini A, Stratton J, Weier S, Hartter T, Plattner B, Rokey G, Hertzel G, Gompa L, Martinez B, Eskridge KM. 2014. Use of Enterococcus faecium as a surrogate for Salmonella enterica during extrusion of a balanced carbohydrate-protein meal. J Food Prot 77:75–82. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopit LM, Kim EB, Siezen RJ, Harris LJ, Marco ML. 2014. Safety of the surrogate microorganism Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 for use in thermal process validation. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1899–1909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03859-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Diao J, Dharmasena M, Ionita C, Jiang X, Rieck J. 2013. Thermal inactivation of desiccation-adapted Salmonella spp. in aged chicken litter. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:7013–7020. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01969-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z, Wang H, Ionita C, Luo F, Jiang X. 2015. Effects of chicken litter storage time and ammonia content on thermal resistance of desiccation-adapted Salmonella spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:6883–6889. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01876-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson DG, Lucore LA. 2012. Validating the reduction of Salmonella and other pathogens in heat processed low-moisture foods Alliance for Innovation & Operational Excellence, Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Chen Z, Li M, Greene AK, Jiang X, Wang J. 2018. Testing a nonpathogenic surrogate microorganism for validating desiccation-adapted Salmonella inactivation in physically heat-treated broiler litter. J Food Prot 81:1418–1424. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunault C, Pourcher A, Burton C. 2011. Using temperature and time criteria to control the effectiveness of continuous thermal sanitation of piggery effluent in terms of set microbial indicators. J Appl Microbiol 111:1492–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunault C, Burton C, Pourcher A. 2013. The impact of fouling on the process performance of the thermal treatment of pig slurry using tubular heat exchangers. J Environ Manage 117:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner C, Williams SM, Burton CH, Cumby TR, Wilkinson PJ, Farrent JW. 1999. Pilot scale thermal treatment of pig slurry for the inactivation of animal virus pathogens. J Environ Sci Health B 34:989–1007. doi: 10.1080/03601239909373241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson MC, Liao J, Boyhan G, Smith C, Ma L, Jiang X, Doyle MP. 2010. Fate of manure-borne pathogen surrogates in static composting piles of chicken litter and peanut hulls. Bioresour Technol 101:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein M, Brown L, Ashbolt NJ, Stuetz RM, Roser DJ. 2011. Inactivation of indicators and pathogens in cattle feedlot manures and compost as determined by molecular and culture assays. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 77:200–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wéry N, Lhoutellier C, Ducray F, Delgenès JP, Godon JJ. 2008. Behaviour of pathogenic and indicator bacteria during urban wastewater treatment and sludge composting, as revealed by quantitative PCR. Water Res 42:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busta F, Suslow T, Parish M, Beuchat L, Farber J, Garrett E, Harris L. 2003. The use of indicators and surrogate microorganisms for the evaluation of pathogens in fresh and fresh‐cut produce. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safety 2:179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00035.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erickson MC, Liao J, Ma L, Jiang X, Doyle MP. 2014. Thermal and nonthermal factors affecting survival of Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes in animal manure–based compost mixtures. J Food Prot 77:1512–1518. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leuenberger P, Ganscha S, Kahraman A, Cappelletti V, Boersema PJ, von Mering C, Claassen M, Picotti P. 2017. Cell-wide analysis of protein thermal unfolding reveals determinants of thermostability. Science 355:eaai7825. doi: 10.1126/science.aai7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2018. Biosolids technology fact sheet: heat drying. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2018-11/documents/heat-drying-factsheet.pdf. Accessed November 2020.

- 33.Smith J, Benedict R, Palumbo S. 1982. Protection against heat-injury in Staphylococcus aureus by solutes. J Food Prot 45:54–58. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-45.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews W, Jacobson A, Hammack T. 2011. Chapter 5: Salmonella. In Bacteriological analytical manual. U.S. FDA, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Composting Council. 2002. The test method for the examination of composting and compost (TMECC). https://www.compostingcouncil.org/page/tmecc. Accessed June 2020.