This study reveals carbohydrate-binding module family 88 (CBM88) as a new family of galactose-binding protein modules, which are found in series with diverse microbial glycoside hydrolases, polysaccharide lyases, and carbohydrate esterases. The definition of CBM88 in the carbohydrate-active enzymes classification (http://www.cazy.org/CBM88.html) will significantly enable future microbial (meta)genome analysis and functional studies.

KEYWORDS: carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs), glycoside hydrolase, xyloglucan, plant biomass, Bacteroidetes, Cellvibrio, Gammaproteobacteria, carbohydrate-active enzyme, mannan, polysaccharide, xyloglucanase

ABSTRACT

Carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) are usually appended to carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) and serve to potentiate catalytic activity, for example, by increasing substrate affinity. The Gram-negative soil saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus is a valuable source for CAZyme and CBM discovery and characterization due to its innate ability to degrade a wide array of plant polysaccharides. Bioinformatic analysis of the CJA_2959 gene product from C. japonicus revealed a modular architecture consisting of a fibronectin type III (Fn3) module, a cryptic module of unknown function (X181), and a glycoside hydrolase family 5 subfamily 4 (GH5_4) catalytic module. We previously demonstrated that the last of these, CjGH5F, is an efficient and specific endo-xyloglucanase (M. A. Attia, C. E. Nelson, W. A. Offen, N. Jain, et al., Biotechnol Biofuels 11:45, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-018-1039-6). In the present study, C-terminal fusion of superfolder green fluorescent protein in tandem with the Fn3-X181 modules enabled recombinant production and purification from Escherichia coli. Native affinity gel electrophoresis revealed binding specificity for the terminal galactose-containing plant polysaccharides galactoxyloglucan and galactomannan. Isothermal titration calorimetry further evidenced a preference for galactoxyloglucan polysaccharide over short oligosaccharides comprising the limit-digest products of CjGH5F. Thus, our results identify the X181 module as the defining member of a new CBM family, CBM88. In addition to directly revealing the function of this CBM in the context of xyloglucan metabolism by C. japonicus, this study will guide future bioinformatic and functional analyses across microbial (meta)genomes.

IMPORTANCE This study reveals carbohydrate-binding module family 88 (CBM88) as a new family of galactose-binding protein modules, which are found in series with diverse microbial glycoside hydrolases, polysaccharide lyases, and carbohydrate esterases. The definition of CBM88 in the carbohydrate-active enzymes classification (http://www.cazy.org/CBM88.html) will significantly enable future microbial (meta)genome analysis and functional studies.

INTRODUCTION

Plant biomass is regarded as a valuable source of renewable energy and biomaterials in light of global climate change and the continuous depletion of petroleum reserves (1–3). Nevertheless, plant biomass utilization is hindered by the intrinsic complexity of the plant cell wall, which arises from the sophisticated assembly of complex polysaccharides and other components. As part of the natural carbon cycle, bacteria and fungi have evolved efficient machineries to break down the tremendous diversity of polysaccharide structures via broad repertoires of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) (4, 5). CAZymes, including glycoside hydrolases (GHs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs), and lytic polysaccharide mono-oxygenases (LPMOs), are often appended to noncatalytic carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) (reviewed in references 6 to 14), which potentiate activity by substrate targeting and proximity effects (15, 16).

Like CAZymes, CBMs are classified into families based on amino acid sequence identity (4; http://www.cazy.org/Carbohydrate-Binding-Modules.html). As of October 2020, 87 families of CBMs have been defined, comprising more than 233,000 sequences from GenBank. The majority of these families contain members that selectively bind plant cell wall polysaccharides (7). CBMs are further classified based on the mode of carbohydrate binding (7). Type A CBMs bind to the crystalline surfaces of insoluble polysaccharide substrates and typically possess flat binding faces. Type B CBMs bind single-glycan chains of soluble polysaccharides internally (i.e., endo-binding), often with cleft-shaped protein surfaces. Type C CBMs bind the termini of glycan chains or short oligosaccharides (i.e., exo-binding) via pocket-shaped binding sites. The number of CBM families is continuously expanding, with 15 new families having been discovered in the past 5 years alone (4, 5, 17–26). The identification and characterization of new CBMs remain a significant challenge (9), and like CAZymes (27), there are likely many potential CBM families lurking in microbial genomes.

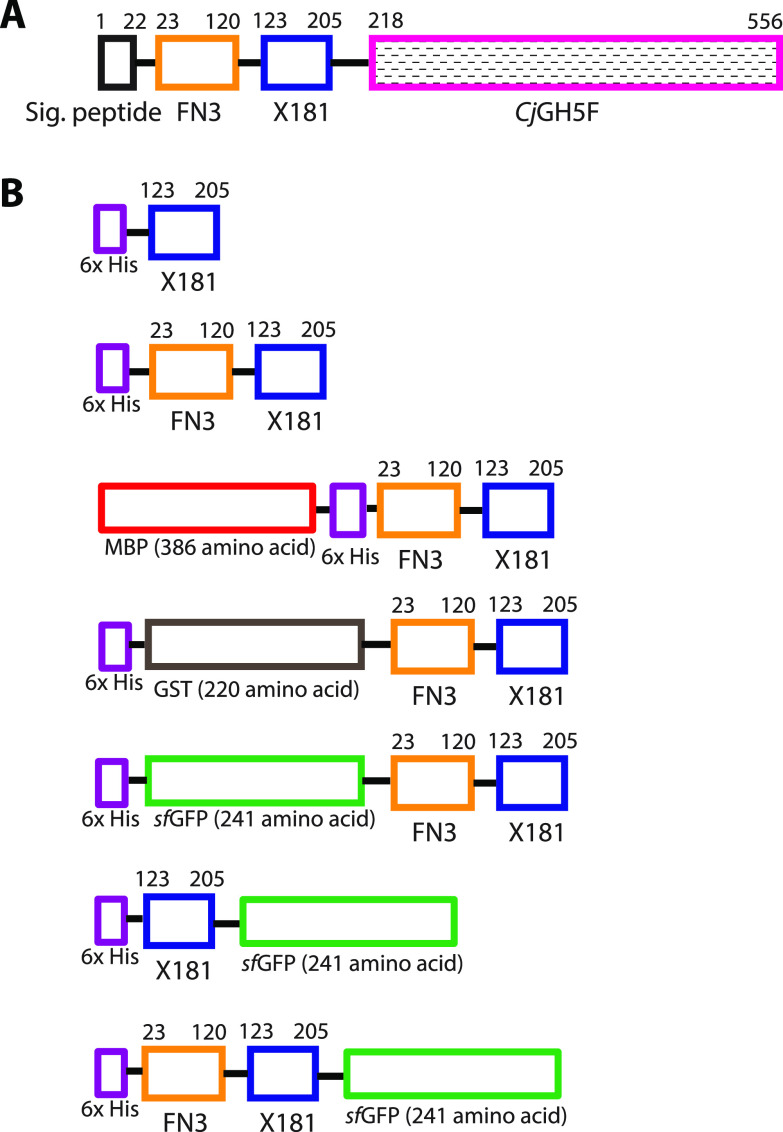

The soil-dwelling saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus is a Gram-negative bacterium that is able to utilize nearly all plant cell wall polysaccharides and, as such, has been a historically important source for CAZyme discovery (28, 29). We recently characterized the ensemble of GHs constituting the xyloglucan utilization system of C. japonicus (30–35). During the course of these studies, we identified a protein module of unknown function in tandem with the endo-xyloglucanase CjGH5F encoded by gene locus CJA_2959 (Fig. 1A) (32). This module had been observed in diverse bacterial genomes and was denoted “X181” in the CAZy database (36; B. Henrissat, personal communication). In light of its size and association with CjGH5F and other CAZymes, we anticipated that X181 may comprise a noncatalytic CBM. To test this hypothesis, we produced the module as a recombinant fusion protein and examined its binding to cellulose and a range of amorphous plant cell wall polysaccharides. Our results indicate that X181 binds terminal galactosyl residues on polysaccharides and constitutes the first representative of the new family CBM88.

FIG 1.

Modular architecture of the native C. japonicus CJA_2959 gene product and different constructs used in the study. (A) The full-length gene product is composed of a signal peptide, an Fn3 domain, an X181 module, and a catalytic GH5_4 (CjGH5F) domain. (B) Recombinant proteins produced for characterization using the E. coli expression vector pET28a and the ligation-independent cloning (LIC) vectors pMCSG53, pMCSG69, and pMCSG-GST-TEV (67). MBP, GST, and sfGFP are connected to X181 or Fn3-X181 by a TEV cleavage site.

(This research was conducted by Mohamed A. Attia in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada [73].)

RESULTS

Bioinformatic analysis.

Gene locus CJA_2959 (GenBank accession no. ACE86198.1) encodes a multimodular protein comprising, in order, a secretion signal peptide (Met1 to Ala22, predicted signal peptidase I cleavage site) (37), a fibronectin type III (Fn3) domain (Gln23 to Cys120), an X181 module (Thr123 to Val205), and the CjGH5F catalytic module (Ser218 to Gln556) (Fig. 1A). A short Gly-Ser-Thr-rich sequence was also observed between the X181 and GH5 modules, which may constitute a flexible linker (38). CjGH5F was previously established as a strict endo-xyloglucanase following module dissection and independent recombinant production; however, the functions of the other modules were not previously characterized (32). Fn3 domains (PFAM PF00041) possess a small beta-sandwich structure and are frequently found in large animal cell and matrix adhesion proteins (e.g., fibronectin) (39) as well as in microbial GHs (40). Although little is known regarding specific functions of Fn3 domains, they generally appear to play structural roles as spacers between binding, catalytic, and/or membrane-anchoring motifs (39–41).

Recombinant protein production and purification.

To characterize the potential biochemical function of the X181 module independent of the CjGH5F catalytic module, we explored several truncated constructs containing a hexahistidine tag to facilitate purification following recombinant expression in Escherichia coli (Fig. 1B). Initial attempts to produce His6-X181, as well as His6-Fn3-X181, independently and in fusion with glutathione S-transferase (GST) (42) were unsuccessful in both E. coli BL21 and E. coli Rosetta strains (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We observed an enhancement of the production of soluble Fn3-X181 in the Rosetta strain when fused to an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP) (42) (Fig. S1). Unfortunately, this protein was proteolytically unstable during the purification process, making it impossible to obtain intact (data not shown).

To overcome this hurdle, we explored protein fusions with “superfolder” green fluorescent protein (SfGFP) (43) (Fig. 1B), which recently enabled us to produce and characterize two cellulose-specific CBMs from C. japonicus (31). Particular advantages of GFP as a fusion partner are the lack of nonspecific carbohydrate binding and the facile photometric detection (31, 44–48). As observed with the N-terminal MBP fusion described above, His6-sfGFP-Fn3-X181 was highly prone to proteolysis during the purification process (Fig. S2). All efforts to minimize this proteolysis by decreasing expression and purification temperatures and by using protease inhibitors were fruitless (data not shown).

C-terminal sfGFP fusions were explored in parallel (Fig. 1B). Recombinant production of the simpler His6-X181-GFP fusion was unsuccessful, with extremely low yields in the soluble fractions, in contrast to His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP. Although most of the His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP fusion protein was produced as insoluble inclusion bodies, we were nonetheless able to obtain modest yields of intact protein from the bacterial lysate (typically ca. 6 mg per liter of culture medium after purification [Fig. S2]; calculated mass, 48,674 Da, observed by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry [ESI-MS], 48,672 Da [Fig. S3]). Hence, His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was used for subsequent characterization. It is notable that this construct is the most homologous to the native protein, with the sfGFP directly replacing the GH5_4 module in series (Fig. 1).

Carbohydrate-binding specificity.

To explore the potential carbohydrate-binding ability of the X181 module in the context of its natural fusion to the endo-xyloglucanase CjGH5F, we employed a panel of common plant cell wall polysaccharides, including cellulose and several amorphous matrix glycans (hemicelluloses). We have previously observed that C. japonicus produces a GH74 endo-xyloglucanase in tandem with a cellulose-specific CBM2 member (31). In an analogous pulldown assay, recombinant His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was incubated with an aqueous suspension of Avicel (microcrystalline cellulose). SDS-PAGE of the supernatant and pellet fractions versus sfGFP and sfGFP-CjCBM2 (31), as negative and positive controls, respectively, revealed no significant cellulose-binding affinity of the X181 module (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Binding capacity of sfGFP, Fn3-X181-sfGFP, and sfGFP-CjCBM2 for Avicel. Recombinant sfGFP (27.7 kDa; lanes 1 and 2), His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP (48.7 kDa; lanes 3 and 4), and sfGFP-CjCBM2 (40.7 kDa; lanes 5 and 6) were incubated with Avicel, and unbound proteins were removed by centrifugation (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). Bound proteins were released from Avicel by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading dye (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). sfGFP was used as a negative control, while sfGFP-CjCBM2 (31) was used as a positive control.

Binding to the soluble plant cell wall polysaccharides barley β-glucan, tamarind galactoxyloglucan, konjac glucomannan, carob (locust bean) galactomannan, guar galactomannan, and beechwood xylan, as well as the artificial hydroxyethyl cellulose, was screened by native affinity gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). Strikingly, retardation of migration was observed in gels containing tamarind galactoxyloglucan, carob galactomannan, and guar galactomannan, which share terminal galactosyl (t-Gal) residues on branches as a commonality. To exclude the possibility that X181 is catalytically active, His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was incubated with tamarind galactoxyloglucan and subjected to the sensitive bicinchoninic acid (BCA)-reducing sugar assay, which was negative.

FIG 3.

Affinity gel electrophoresis for Fn3-X181-sfGFP against different polysaccharide substrates. Recombinant protein bands were visualized by fluorescence (A) and Coomassie blue staining (B) following electrophoresis at 90 V for 10 h. The negative-control sfGFP completely migrated through under these conditions. (C) Gel following 5.5 h of electrophoresis, which demonstrates no binding of the negative-control sfGFP toward tamarind galactoxyloglucan (fluorescence visualization). BBG, barley β-glucan; HEC, hydroxyethyl cellulose; KGM, konjac glucomannan; XyG, tamarind galactoxyloglucan; GalMan, galactomannan.

To further elucidate the specificity of the X181 module in the context of the full-length CJA_2959 gene product, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to measure the binding affinity of Fn3-X181-sfGFP for tamarind galactoxyloglucan and for the corresponding limit-digest products of CjGH5F (Fig. 4 and Table 1). The latter comprises a mixture of oligosaccharides based on a Glc4 backbone, namely, XXXG (Glc4Xyl3), XLXG (Glc4Xyl3Gal), XXLG (Glc4Xyl3Gal), and XLLG (Glc4Xyl3Gal2) in the approximate ratio of 2:1:3:3 (32; see reference 49 for xyloglucan oligosaccharide nomenclature). Commensurate with the affinity gel electrophoresis results, ITC revealed a high association constant for the galactoxyloglucan polysaccharide (Ka = 7.17 × 103 M−1, based on a molar equivalent concentration of the Glc4-based oligosaccharide units). The affinity for the limit-digest products was correspondingly lower (Ka = 1.11 × 103 M−1), as might be expected to facilitate product release. The combined thermodynamic data indicate that substrate binding is enthalpically driven, as has been observed for the majority of CBMs studied to date (50–52).

FIG 4.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of Fn3-X181-sfGFP against different ligands. (A) Tamarind seed xyloglucan. (B) Glc4-based tamarind seed xyloglucan oligosaccharides. The top graph in each pair shows the raw heat during titration, while the bottom graph shows the integrated heat after correction.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the thermodynamic parameters for Fn3-X181-sfGFP obtained by isothermal titration calorimetry

| Carbohydrate | Ka (M−1) | ΔG° (kcal mol−1) | ΔH° (kcal mol−1) | TΔS° (kcal mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XyGa | (7.17 ± 0.52) × 103 | −5.3 | −10 ± 0.4 | −4.7 |

| XyGO | (1.11 ± 0.04) × 103 | −4.2 | −6.5 ± 0.1 | −2.3 |

Binding thermodynamics of tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan (XyG) is based on the equivalent molar concentration of Glc4-based xyloglucan oligosaccharide (XyGO) units.

DISCUSSION

CBMs are commonly found appended via flexible linkers to glycoside hydrolases in unique multimodular architectures (6–14, 38). Here, we identified and functionally characterized a unique protein module from the CJA_2959 gene product in the saprophyte C. japonicus, which establishes the new family CBM88 in the CAZy classification (4). This CBM exclusively binds the t-Gal-containing plant cell wall polysaccharides galactoxyloglucan and galactomannan. The recognition of t-Galβ-(1,2)-Xylα-(1,6) branches on galactoxyloglucan by the CBM is congruent with its partnership with the specific endo-xyloglucanase CjGH5F (32) (Fig. 1A).

More broadly, CBM88 members are primarily found in predicted multimodular CAZymes from Bacteroidetes and Gammaproteobacteria, comprising diverse GH5 (predicted endo-xyloglucanases or endo-mannanases) (53), GH16 (predicted endo-glucanases or endo-galactanases) (54), GH26 (predicted endo-mannanases) (55), GH53 (predicted endo-galactanases) (56), GH74 (predicted endo-xyloglucanases) (57), PL11 (predicted rhamnogalacturonan lyases) (58), and carbohydrate esterase catalytic modules (see http://www.cazy.org/CBM88.html for an actively updated list of sequences and source organisms) (4). These families are united by a specificity for galactans or galactosyl-branched polysaccharides, which further rationalizes the observed t-Gal specificity of CBM88. In particular, GH74 is a family of specific endo-(galacto)xyloglucanases (4, 5, 57), whereas GH26 is primarily comprised of endo-(galacto)mannanases (4, 5, 55). Interestingly, CBM88 modules are also found in sequence with GH8, GH10, GH30 (59), and GH43 (60) modules, which are classically associated with xylan hydrolysis (5), suggesting potential alternative binding specificities within the family.

We note here that our inability to produce the CBM88 module independently of the Fn3 domain formally precludes us from ruling out a role of the latter in carbohydrate binding. On the other hand, Fn3 domains are generally not known to have this function (39–41). Furthermore, CBM88 is otherwise not preceded by an Fn3 domain in the vast majority of other multimodular protein sequences currently known, with the CJA_2959 gene product studied here being a rare exception (http://www.cazy.org/CBM88.html) (4).

Our attempts to crystallize the sfGFP fusion (61) and the Fn3-X181 protein following tobacco etch virus (TEV) cleavage have currently been unsuccessful, thus precluding definitive structure-function analysis. Yet, we anticipate that CjCBM88 may be a type C CBM that directs the endo-xyloglucanase to the polysaccharide through the recognition of side chain termini. Such an end-on binding mode is reminiscent of the interaction of a Hungateiclostridium thermocellum CBM62 with t-Gal residues on both galactoxyloglucan oligosaccharides (PDB ID 2YFZ) and galactomannan oligosaccharides (PDB IDs 2YB7 and 2YG0) (52). This binding mode is notably distinct from that observed in interactions of an exemplar type B CBM65 with xyloglucan, which involve binding to the β-(1,4)-glucan backbone and α-(1,6)-xylosyl side chains (PDB ID 2YPJ) (51). Indeed, backbone recognition is common among other type B CBMs (e.g., CBM44) (62), type A CBMs (e.g., CBM2 and CBM3) (63), and cell surface glycan-binding proteins (64, 65), which demonstrate various degrees of preference for the branched xyloglucan chains versus the homologous β-(1,4)-glucan, cellulose.

To conclude, we anticipate that the definition of CBM88 in the CAZy classification will aid bioinformatic analysis of (meta)genomic sequences through refined modular dissection of complex CAZymes (4, 36). We also look forward to future structural biology studies to provide molecular insight into the details of carbohydrate recognition by this nascent CBM family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatic analysis.

The modular architecture of the full-length protein Fn3-X181-CjGH5F, encoded by C. japonicus gene locus CJA_2959 (GenBank accession no. ACE86198.1) (29), was obtained from BLASTP analysis and alignment with representative GH modules from the CAZy database (4) using ClustalW (66). The boundaries of the X181 module were generously provided by Bernard Henrissat (head of the CAZy Database, AFMB-CNRS, Marseille, France) (36).

Plasmid construction.

All PCR primers are listed in Table 2. The open reading frames (ORFs) for X181 and Fn3-X181 were PCR amplified from C. japonicus Ueda107 genomic DNA. Amplified products were double digested with NheI and XhoI, gel purified, and then ligated to the respective site of pET28a so that they were fused to an N-terminal hexahistidine (His6) tag. For GFP fusion, overlapping extension PCR was used to fuse the sfGFP sequence to either the N or C terminus of the Fn3-X181 and X181 domain cDNA, with a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site in between. TEV-Fn3-X181, Fn3-X181-TEV, and X181-TEV were PCR amplified from C. japonicus genomic DNA, while sfGFP was amplified from a pBAD vector harboring the sfGFP gene (GenBank accession no. AGT98536.1) (generously provided by Lawrence McIntosh, University of British Columbia). Purified sfGFP was mixed individually with the purified TEV-Fn3-X181, Fn3-X181-TEV, and X181-TEV, and the respective fusion products sfGFP-TEV-Fn3-X181, Fn3-X181-TEV-sfGFP, and X181-TEV-sfGFP were obtained by PCR amplification. The purified sfGFP-TEV-Fn3-X181, Fn3-X18-TEV-sfGFP, and X18-TEV-sfGFP DNA fragments were cloned in pET28a as previously described for Fn3-X181 after double digesting with NheI and XhoI and ligating the digested products in the respective sites of the pET28a vector. The amplified Fn3-X181 product was also individually ligated in SspI-linearized pMCSG53, pMCSG69, and pMCSG-GST-TEV (a vector derived from pMCSG52) using ligation-independent cloning (LIC) strategy (67) so that the ORF Fn3-X181 was fused to N-terminal His6, MBP-His6, and His6-GST, respectively. Successful cloning was confirmed by PCR and plasmid DNA sequencing. Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase was used for all the PCR amplifications.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence | Recombinant protein(s) |

|---|---|---|

| X181-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGACTGCGGTGACGCCCTATATCAAC-3′ | X181 |

| X181-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGACCGTTACGCTGAAAACCTGGC-3′ | X181 |

| FN3-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGCAGAATTGCGGCAGCGGTGGCG-3′ | FN3-X181 |

| X181-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGACCGTTACGCTGAAAACCTGGC-3′ | FN3-X181 |

| GFP-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGGTTAGCAAAGGTGAAGAAC-3′ | GFP-TEVoh |

| GFP-TEVoh-R | 5′-GAAAATAAAGATTCTCGCTGCCTTTATACAGTTC-3′ | GFP-TEVoh |

| GFPoh-TEV-FN3-F | 5′-CTGTATAAAGGCAGCGAGAATCTTTATTTTCAGGGCCAGAATTGCGGCAGCGGTGGCG-3′ | GFPoh-TEV-FN3-X181 |

| X181-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGACCGTTACGCTGAAAACCTGGC-3′ | GFPoh-TEV-FN3-X181 |

| GFP-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGGTTAGCAAAGGTGAAGAAC-3′ | GFP-FN3-X181 |

| X181-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGACCGTTACGCTGAAAACCTGGC-3′ | GFP-FN3-X181 |

| FN3-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGCAGAATTGCGGCAGCGGTGGCG-3′ | FN3-X181-TEV-GFPoh |

| X181-TEV-GFPoh-R | 5′-CTTCACCTTTGCTAACGCCCTGAAAATAAAGATTCTCGACCGTTACGCTGAAAACCTGG-3′ | FN3-X181-TEV-GFPoh |

| TEVoh-GFP-F | 5′-CTTTATTTTCAGGGCGTTAGCAAAGGTGAAGAAC-3′ | TEVoh-GFP |

| GFP-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGCTGCCTTTATACAGTTCATC-3′ | TEVoh-GFP |

| FN3-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGCAGAATTGCGGCAGCGGTGGCG-3′ | FN3-X181-GFP |

| GFP-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGCTGCCTTTATACAGTTCATC-3′ | FN3-X181-GFP |

| X181-NheI-F | 5′-GACCGCTAGCATGACTGCGGTGACGCCCTATATCAAC-3′ | X181-GFP |

| GFP-XhoI-R | 5′-GGTCCTCGAGTTAGCTGCCTTTATACAGTTCATC-3′ | X181-GFP |

| FN3-X181-LIC-F | 5′-TACTTCCAATCCAATGCCATGCAGAATTGCGGCAGCGGTGGC-3′ | FN3-X181, GST-FN3-X181, MBP-FN3-X181 |

| FN3-X181-LIC-R | 5′-TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTATCAGACCGTTACGCTGAAAAC-CTGGC-3′ | FN3-X181, GST-FN3-X181, MBP-FN3-X181 |

Gene expression and protein purification.

To produce the recombinant proteins His6-X181, His6-Fn3-X181, His6-sfGFP-Fn3-X181, His6-X181-sfGFP, and His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP in E. coli, constructs were individually transformed into chemically competent Rosetta (DE3) cells. Colonies were grown on LB solid media containing kanamycin (50 µg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (33 µg ml−1). One colony of the transformed E. coli cells was inoculated in 10 ml of LB medium containing the same antibiotics and grown overnight at 37°C (200 rpm). The whole overnight culture was used to inoculate 1 liter of terrific broth medium containing the proper antibiotics. Cultures were grown at 37°C (200 rpm) until A600 was equal to 0.6. Gene expression was induced by adding isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. After induction, cultures were grown at 16°C (200 rpm) for 20 to 22 h. Cultures were then centrifuged, and pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of E. coli lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Cells were then lysed by sonication, and the clear supernatant was separated by centrifuging the sonicated cultures at 4°C (12,400 × g for 60 min). Recombinant proteins were purified from the clear soluble lysates using a Ni2+ affinity column and gradient elution in a fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system utilizing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, and 5% glycerol. The purity of the recombinant proteins was determined by SDS-PAGE. Pure fractions were pooled, concentrated, and buffer exchanged with 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl. Protein concentrations were determined using an Epoch microvolume spectrophotometer system (BioTek, USA) at 280 nm. The fidelity of protein translation was confirmed using intact protein mass spectrometry essentially as previously described (68).

When LIC vectors were used, individual constructs were transformed into the chemically competent BL21 and Rosetta (DE3) cells. An expression trial was conducted in 10 ml LB medium containing ampicillin (50 µg ml−1) (BL21) or ampicillin (50 µg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (33 µg ml−1) (Rosetta) to identify constructs with successful soluble expression of the recombinant proteins. Briefly, cultures were grown at 37°C (200 rpm) until A600 was equal to 0.6 before they were induced by IPTG at a final concentration of 0.2 mM. Cultures were then grown overnight at 16°C (200 rpm) before aliquots of 1 ml were taken out and centrifuged at 4°C in a bench-top centrifuge for 5 min (15,000 × g). Supernatants were discarded, and cell pellets were resuspended in 700 µl lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 500 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, and 5% glycerol. Cells were sonicated, and the clear supernatants were separated from pellets by centrifugation in a bench-top cooling centrifuge for 15 min (15,000 × g). Clear supernatants were mixed with 4× SDS-PAGE loading dye and boiled for 10 min before 10 to 15 µl were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Pellets were resuspended in 150 to 300 µl of the same lysis buffer and mixed with 4× SDS-PAGE loading dye before 10 µl was analyzed on SDS-PAGE.

For the large-scale production of MBP-Fn3-X181 in the Rosetta strain, the same protocol described for the production of X181, Fn3-X181, sfGFP-Fn3-X181, Fn3-X181-sfGFP, and X181-sfGFP was employed with the exception of the antibiotic ampicillin (50 µg ml−1), which was used instead of kanamycin.

Carbohydrate sources.

Tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan, konjac glucomannan, barley β-glucan, beechwood xylan, and carob galactomannan were purchased from Megazyme (Bray, Ireland). Hydroxyethylcellulose was purchased from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). Guar galactomannan was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Glc4-based xyloglucan oligosaccharides were prepared from tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan using the endo-xyloglucanase CjGH5E (32), essentially as previously described (69).

Cellulose-binding capacity.

Qualitative analysis of cellulose-binding capacity was performed as previously described (31). Briefly, 100 µg of the recombinant protein His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was mixed with 10 mg Avicel type PH-101 in a 200-µl reaction volume containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The mixture was gently agitated while sitting on ice for 1 h. The supernatant was removed by centrifugation for 5 min (12,000 × g) and mixed with SDS-PAGE loading dye, and 6 µl was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Avicel pellets were washed twice with 250 µl of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and then resuspended in 200 µl of the same buffer. Forty microliters of 6× SDS-PAGE loading dye was added, and then bound proteins were released by boiling for 10 min before 6 µl was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Affinity gel electrophoresis.

The methodology for the native affinity gel electrophoresis was adapted from a previously described protocol (70). Briefly, 7 µg of the native recombinant His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was loaded on native 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels containing 0.1% final concentration of the tested polysaccharides barley β-glucan, hydroxyethylcellulose, beechwood xylan, konjac glucomannan, tamarind seed galactoxyloglucan, carob galactomannan, and guar galactomannan. Electrophoresis was conducted at room temperature for approximately 10 h at 90 V due to the slow migration of the recombinant protein. Protein bands were visualized by both fluorescence (Bio-Rad gel documentation system with an excitation filter of 450 nm and an emission filter of 510 nm) and Coomassie blue staining.

Activity assays.

One microgram of His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was added to 2 mg ml−1 tamarind galacto-xyloglucan (XyG) in a 200-µl reaction volume containing 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and 2 mM CaCl2. The reaction mixture was incubated at 40°C for 30 min before the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (71) was used to detect the possible formation of new reducing ends.

Isothermal titration calorimetry.

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed using a MicroCal VP-ITC calorimeter essentially as previously described (64, 65, 72). Purified His6-Fn3-X181-sfGFP was dialyzed against 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl and 2 mM CaCl2. Tamarind galactoxyloglucan (2.5 mg ml−1) and the corresponding xyloglucan oligosaccharides (10 mM) were dissolved independently in the same buffer. The recombinant protein (35 to 40 µM) was placed in the sample cell, while the substrate was loaded in the injecting syringe. After the sample cell temperature equilibrated to 25°C, a first injection of 2 µl of the ligand, followed by 25 subsequent injections of 10 µl each, was performed while stirring at 280 rpm. The resulting heat of the reaction was recorded, and the data were analyzed using the Origin software program.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bernard Henrissat and Nicolas Terrapon (AFMB-CNRS, Marseille, France) for discussions on the taxonomic distribution of CBM88 members and advice regarding CBM family creation.

Work at the University of British Columbia was generously supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grants RGPIN 435223-13 and RGPIN-2018-03892 and Strategic Network Grant NETGP 45131-13 for the NSERC Industrial Biocatalysis Network), the Michael Smith Laboratories (faculty startup and postgraduate funding), the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund.

This research was conducted by M.A.A. in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a PhD degree from the University of British Columbia (73).

M.A.A. performed bioinformatic analysis, recombinant protein production, and biochemical characterization. H.B. supervised research and cowrote the manuscript.

We declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ragauskas AJ, Beckham GT, Biddy MJ, Chandra R, Chen F, Davis MF, Davison BH, Dixon RA, Gilna P, Keller M, Langan P, Naskar AK, Saddler JN, Tschaplinski TJ, Tuskan GA, Wyman CE. 2014. Lignin valorization: improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 344:1246843. doi: 10.1126/science.1246843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himmel ME, Ding SY, Johnson DK, Adney WS, Nimlos MR, Brady JW, Foust TD. 2007. Biomass recalcitrance: engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science 315:804–807. doi: 10.1126/science.1137016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li LL, McCorkle SR, Monchy S, Taghavi S, van der Lelie D. 2009. Bioprospecting metagenomes: glycosyl hydrolases for converting biomass. Biotechnol Biofuels 2:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombard V, Ramulu HG, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. 2014. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CAZypedia Consortium. 2018. Ten years of CAZypedia: a living encyclopedia of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Glycobiology 28:3–8. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. 2004. Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem J 382:769–781. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert HJ, Knox JP, Boraston AB. 2013. Advances in understanding the molecular basis of plant cell wall polysaccharide recognition by carbohydrate-binding modules. Curr Opin Struct Biol 23:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies GJ, Williams SJ. 2016. Carbohydrate-active enzymes: sequences, shapes, contortions and cells. Biochem Soc Trans 44:79–87. doi: 10.1042/BST20150186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott DW, van Bueren AL. 2014. Using structure to inform carbohydrate binding module function. Curr Opin Struct Biol 28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoseyov O, Shani Z, Levy I. 2006. Carbohydrate binding modules: biochemical properties and novel applications. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70:283–295. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00028-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto H. 2006. Recent structural studies of carbohydrate-binding modules. Cell Mol Life Sci 63:2954–2967. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillen D, Sanchez S, Rodriguez-Sanoja R. 2010. Carbohydrate-binding domains: multiplicity of biological roles. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:1241–1249. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ficko-Blean E, Boraston AB. 2012. Insights into the recognition of the human glycome by microbial carbohydrate-binding modules. Curr Opin Struct Biol 22:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armenta S, Moreno-Mendieta S, Sanchez-Cuapio Z, Sanchez S, Rodriguez-Sanoja R. 2017. Advances in molecular engineering of carbohydrate-binding modules. Proteins 85:1602–1617. doi: 10.1002/prot.25327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herve C, Rogowski A, Blake AW, Marcus SE, Gilbert HJ, Knox JP. 2010. Carbohydrate-binding modules promote the enzymatic deconstruction of intact plant cell walls by targeting and proximity effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005732107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolam DN, Ciruela A, McQueen-Mason S, Simpson P, Williamson MP, Rixon JE, Boraston A, Hazlewood GP, Gilbert HJ. 1998. Pseudomonas cellulose-binding domains mediate their effects by increasing enzyme substrate proximity. Biochemical J 331:775–781. doi: 10.1042/bj3310775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan CJ, Feng YL, Cao QL, Huang MY, Feng JX. 2016. Identification of a novel family of carbohydrate-binding modules with broad ligand specificity. Sci Rep 6:19392. doi: 10.1038/srep19392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsberg Z, Nelson CE, Dalhus B, Mekasha S, Loose JS, Crouch LI, Rohr AK, Gardner JG, Eijsink VG, Vaaje-Kolstad G. 2016. Structural and functional analysis of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase important for efficient utilization of chitin in Cellvibrio japonicus. J Biol Chem 291:7300–7312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.700161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valk V, Lammerts van Bueren A, van der Kaaij RM, Dijkhuizen L. 2016. Carbohydrate-binding module 74 is a novel starch-binding domain associated with large and multidomain alpha-amylase enzymes. FEBS J 283:2354–2368. doi: 10.1111/febs.13745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venditto I, Luis AS, Rydahl M, Schuckel J, Fernandes VO, Vidal-Melgosa S, Bule P, Goyal A, Pires VM, Dourado CG, Ferreira LM, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Knox JP, Basle A, Najmudin S, Gilbert HJ, Willats WG, Fontes CM. 2016. Complexity of the Ruminococcus flavefaciens cellulosome reflects an expansion in glycan recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:7136–7141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601558113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campos BM, Liberato MV, Alvarez TM, Zanphorlin LM, Ematsu GC, Barud H, Polikarpov I, Ruller R, Gilbert HJ, Zeri AC, Squina FM. 2016. A novel carbohydrate-binding module from sugar cane soil metagenome featuring unique structural and carbohydrate affinity properties. J Biol Chem 291:23734–23743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cockburn DW, Suh C, Medina KP, Duvall RM, Wawrzak Z, Henrissat B, Koropatkin NM. 2018. Novel carbohydrate binding modules in the surface anchored alpha-amylase of Eubacterium rectale provide a molecular rationale for the range of starches used by this organism in the human gut. Mol Microbiol 107:249–264. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moroz OV, Jensen PF, McDonald SP, McGregor N, Blagova E, Comamala G, Segura DR, Anderson L, Vasu SM, Rao VP, Giger L, Sørensen TH, Monrad RN, Svendsen A, Nielsen JE, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Brumer H, Rand KD, Wilson KS. 2018. Structural dynamics and catalytic properties of a multimodular xanthanase. ACS Catal 8:6021–6034. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fredriksen L, Stokke R, Jensen MS, Westereng B, Jameson JK, Steen IH, Eijsink VGH. 2019. Discovery of a thermostable GH10 xylanase with broad substrate specificity from the Arctic mid-ocean ridge vent system. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e02970-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02970-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leth ML, Ejby M, Workman C, Ewald DA, Pedersen SS, Sternberg C, Bahl MI, Licht TR, Aachmann FL, Westereng B, Abou Hachem M. 2018. Differential bacterial capture and transport preferences facilitate co-growth on dietary xylan in the human gut. Nat Microbiol 3:570–580. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamford NC, Le Mauff F, Van Loon JC, Ostapska H, Snarr BD, Zhang Y, Kitova EN, Klassen JS, Codee JDC, Sheppard DC, Howell PL. 2020. Structural and biochemical characterization of the exopolysaccharide deacetylase Agd3 required for Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation. Nat Commun 11:2450. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helbert W, Poulet L, Drouillard S, Mathieu S, Loiodice M, Couturier M, Lombard V, Terrapon N, Turchetto J, Vincentelli R, Henrissat B. 2019. Discovery of novel carbohydrate-active enzymes through the rational exploration of the protein sequences space. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:6063–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815791116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner JG. 2016. Polysaccharide degradation systems of the saprophytic bacterium Cellvibrio japonicus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:121. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deboy RT, Mongodin EF, Fouts DE, Tailford LE, Khouri H, Emerson JB, Mohamoud Y, Watkins K, Henrissat B, Gilbert HJ, Nelson KE. 2008. Insights into plant cell wall degradation from the genome sequence of the soil bacterium Cellvibrio japonicus. J Bacteriol 190:5455–5463. doi: 10.1128/JB.01701-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsbrink J, Izumi A, Ibatullin FM, Nakhai A, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ, Brumer H. 2011. Structural and enzymatic characterization of a glycoside hydrolase family 31 alpha-xylosidase from Cellvibrio japonicus involved in xyloglucan saccharification. Biochem J 436:567–580. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attia M, Stepper J, Davies GJ, Brumer H. 2016. Functional and structural characterization of a potent GH74 endo-xyloglucanase from the soil saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus unravels the first step of xyloglucan degradation. FEBS J 283:1701–1719. doi: 10.1111/febs.13696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attia MA, Nelson CE, Offen WA, Jain N, Davies GJ, Gardner JG, Brumer H. 2018. In vitro and in vivo characterization of three Cellvibrio japonicus glycoside hydrolase family 5 members reveals potent xyloglucan backbone-cleaving functions. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:45. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson CE, Attia MA, Rogowski A, Morland C, Brumer H, Gardner JG. 2017. Comprehensive functional characterization of the glycoside hydrolase family 3 enzymes from Cellvibrio japonicus reveals unique metabolic roles in biomass saccharification. Environ Microbiol 19:5025–5039. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsbrink J, Thompson AJ, Lundqvist M, Gardner JG, Davies GJ, Brumer H. 2014. A complex gene locus enables xyloglucan utilization in the model saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus. Mol Microbiol 94:418–433. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silipo A, Larsbrink J, Marchetti R, Lanzetta R, Brumer H, Molinaro A. 2012. NMR spectroscopic analysis reveals extensive binding interactions of complex xyloglucan oligosaccharides with the Cellvibrio japonicus glycoside hydrolase family 31 α-xylosidase. Chemistry 18:13395–13404. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies GJ, Sinnott ML. 2008. Sorting the diverse: the sequence-based classifications of carbohydrate-active enzymes. Biochemist 30:26–32. doi: 10.1042/BIO03004026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2011. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilkes NR, Henrissat B, Kilburn DG, Miller RC, Jr, Warren RA. 1991. Domains in microbial beta-1, 4-glycanases: sequence conservation, function, and enzyme families. Microbiol Rev 55:303–315. doi: 10.1128/MR.55.2.303-315.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson H. 1990. Adhesion molecules and animal development. Experientia 46:2–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01955407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Little E, Bork P, Doolittle RF. 1994. Tracing the spread of fibronectin type III domains in bacterial glycohydrolases. J Mol Evol 39:631–643. doi: 10.1007/BF00160409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbott DW, Boraston AB. 2007. The structural basis for exopolygalacturonase activity in a family 28 glycoside hydrolase. J Mol Biol 368:1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa S, Almeida A, Castro A, Domingues L. 2014. Fusion tags for protein solubility, purification, and immunogenicity in Escherichia coli: the novel Fh8 system. Front Microbiol 5:63. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedelacq JD, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. 2006. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 24:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nbt1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavoosi M, Lam D, Bryan J, Kilburn DG, Haynes CA. 2007. Mechanically stable porous cellulose media for affinity purification of family 9 cellulose-binding module-tagged fusion proteins. J Chromatogr A 1175:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kavoosi M, Meijer J, Kwan E, Creagh AL, Kilburn DG, Haynes CA. 2004. Inexpensive one-step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with the family 9 carbohydrate-binding module of xylanase 10A from T. maritima. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 807:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavoosi M, Sanaie N, Dismer F, Hubbuch J, Kilburn DG, Haynes CA. 2007. A novel two-zone protein uptake model for affinity chromatography and its application to the description of elution band profiles of proteins fused to a family 9 cellulose binding module affinity tag. J Chromatogr A 1160:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong J, Ye X, Wang Y, Zhang YHP. 2008. Bioseparation of recombinant cellulose-binding module-proteins by affinity adsorption on an ultra-high-capacity cellulosic adsorbent. Anal Chim Acta 621:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim S, Chundawat SPS, Fox BG. 2014. Expression, purification and characterization of a functional carbohydrate-binding module from Streptomyces sp. SirexAA-E. Protein Expr Purif 98:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuomivaara ST, Yaoi K, O'Neill MA, York WS. 2015. Generation and structural validation of a library of diverse xyloglucan-derived oligosaccharides, including an update on xyloglucan nomenclature. Carbohydr Res 402:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charnock SJ, Bolam DN, Nurizzo D, Szabo L, McKie VA, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. 2002. Promiscuity in ligand-binding: the three-dimensional structure of a Piromyces carbohydrate-binding module, CBM29-2, in complex with cello-and mannohexaose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:14077–14082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212516199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luis AS, Venditto I, Temple MJ, Rogowski A, Basle A, Xue J, Knox JP, Prates JAM, Ferreira LMA, Fontes CMGA, Najmudin S, Gilbert HJ. 2013. Understanding how noncatalytic carbohydrate binding modules can display specificity for xyloglucan. J Biol Chem 288:4799–4809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.432781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montanier CY, Correia MAS, Flint JE, Zhu YP, Basle A, McKee LS, Prates JAM, Polizzi SJ, Coutinho PM, Lewis RJ, Henrissat B, Fontes C, Gilbert HJ. 2011. A novel, noncatalytic carbohydrate-binding module displays specificity for galactose-containing polysaccharides through calcium-mediated oligomerization. J Biol Chem 286:22499–22509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.217372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aspeborg H, Coutinho PM, Wang Y, Brumer H, Henrissat B. 2012. Evolution, substrate specificity and subfamily classification of glycoside hydrolase family 5 (GH5). BMC Evol Biol 12:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viborg AH, Terrapon N, Lombard V, Michel G, Czjzek M, Henrissat B, Brumer H. 2019. A subfamily roadmap of the evolutionarily diverse glycoside hydrolase family 16 (GH16). J Biol Chem 294:15973–15986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilbert HJ, Stalbrand H, Brumer H. 2008. How the walls come crumbling down: recent structural biochemistry of plant polysaccharide degradation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 11:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ryttersgaard C, Lo Leggio L, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Larsen S. 2002. Aspergillus aculeatus beta-1,4-galactanase: substrate recognition and relations to other glycoside hydrolases in clan GH-A. Biochemistry 41:15135–15143. doi: 10.1021/bi026238c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arnal G, Stogios PJ, Asohan J, Attia MA, Skarina T, Viborg AH, Henrissat B, Savchenko A, Brumer H. 2019. Substrate specificity, regiospecificity, and processivity in glycoside hydrolase family 74. J Biol Chem 294:13233–13247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lombard V, Bernard T, Rancurel C, Brumer H, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B. 2010. A hierarchical classification of polysaccharide lyases for glycogenomics. Biochem J 432:437–444. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.St John FJ, Gonzalez JM, Pozharski E. 2010. Consolidation of glycosyl hydrolase family 30: a dual domain 4/7 hydrolase family consisting of two structurally distinct groups. FEBS Lett 584:4435–4441. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mewis K, Lenfant N, Lombard V, Henrissat B. 2016. Dividing the large glycoside hydrolase family 43 into subfamilies: a motivation for detailed enzyme characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:1686–1692. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03453-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suzuki N, Hiraki M, Yamada Y, Matsugaki N, Igarashi N, Kato R, Dikic I, Drew D, Iwata S, Wakatsuki S, Kawasaki M. 2010. Crystallization of small proteins assisted by green fluorescent protein. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:1059–1066. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910032944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Najmudin S, Guerreiro C, Carvalho AL, Prates JAM, Correia MAS, Alves VD, Ferreira LMA, Romao MJ, Gilbert HJ, Bolam DN, Fontes C. 2006. Xyloglucan is recognized by carbohydrate-binding modules that interact with beta-glucan chains. J Biol Chem 281:8815–8828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hernandez-Gomez MC, Rydahl MG, Rogowski A, Morland C, Cartmell A, Crouch L, Labourel A, Fontes CMGA, Willats WGT, Gilbert HJ, Knox JP. 2015. Recognition of xyloglucan by the crystalline cellulose-binding site of a family 3a carbohydrate-binding module. FEBS Lett 589:2297–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tauzin AS, Kwiatkowski KJ, Orlovsky NI, Smith CJ, Creagh AL, Haynes CA, Wawrzak Z, Brumer H, Koropatkin NM. 2016. Molecular dissection of xyloglucan recognition in a prominent human gut symbiont. mBio 7:e02134-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02134-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamura K, Foley MH, Gardill BR, Dejean G, Schnizlein M, Bahr CME, Louise Creagh A, van Petegem F, Koropatkin NM, Brumer H. 2019. Surface glycan-binding proteins are essential for cereal beta-glucan utilization by the human gut symbiont Bacteroides ovatus. Cell Mol Life Sci 76:4319–4340. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03115-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eschenfeldt WH, Lucy S, Millard CS, Joachimiak A, Mark ID. 2009. A family of LIC vectors for high-throughput cloning and purification of proteins. Methods Mol Biol 498:105–115. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sundqvist G, Stenvall M, Berglund H, Ottosson J, Brumer H. 2007. A general, robust method for the quality control of intact proteins using LC-ESI-MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 852:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eklof JM, Ruda MC, Brumer H. 2012. Distinguishing xyloglucanase activity in endo-beta(1 → 4)glucanases. Methods Enzymol 510:97–120. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415931-0.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abbott DW, Boraston AB. 2012. Quantitative approaches to the analysis of carbohydrate-binding module function. Methods Enzymol 510:211–231. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415931-0.00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnal G, Attia MA, Asohan J, Brumer H. 2017. A low-volume, parallel copper-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay for glycoside hydrolases. Methods Mol Biol 1588:3–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6899-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larsbrink J, Rogers TE, Hemsworth GR, McKee LS, Tauzin AS, Spadiut O, Klinter S, Pudlo NA, Urs K, Koropatkin NM, Creagh AL, Haynes CA, Kelly AG, Cederholm SN, Davies GJ, Martens EC, Brumer H. 2014. A discrete genetic locus confers xyloglucan metabolism in select human gut Bacteroidetes. Nature 506:498–502. doi: 10.1038/nature12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Attia MA. 2018. Enzymology of the xyloglucan utilization system in the soil saprophyte Cellvibrio japonicus. PhD thesis. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. doi: 10.14288/1.0364095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.