Proteobacterial methanotrophs—groups of microorganisms that utilize methane as a source of energy and carbon—have been known to utilize unique mechanisms to scavenge copper, namely, utilization of methanobactin, a polypeptide that binds copper with high affinity and specificity. Previously the possibility that copper sequestration by methanotrophs may lead to alteration of cuproenzyme-mediated reactions in denitrifiers and consequently increase emission of potent greenhouse gas N2O has been suggested in axenic and coculture experiments.

KEYWORDS: copper, denitrification, methanobactin, methanotrophs, nitrous oxide

ABSTRACT

Unique means of copper scavenging have been identified in proteobacterial methanotrophs, particularly the use of methanobactin, a novel ribosomally synthesized, post-translationally modified polypeptide that binds copper with very high affinity. The possibility that copper sequestration strategies of methanotrophs may interfere with copper uptake of denitrifiers in situ and thereby enhance N2O emissions was examined using a suite of laboratory experiments performed with rice paddy microbial consortia. Addition of purified methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b to denitrifying rice paddy soil microbial consortia resulted in substantially increased N2O production, with more pronounced responses observed for soils with lower copper content. The N2O emission-enhancing effect of the soil’s native mbnA-expressing Methylocystaceae methanotrophs on the native denitrifiers was then experimentally verified with a Methylocystaceae-dominant chemostat culture prepared from a rice paddy microbial consortium as the inoculum. Finally, with microcosms amended with various cell numbers of methanobactin-producing Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b before CH4 enrichment, microbiomes with different ratios of methanobactin-producing Methylocystaceae to gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs incapable of methanobactin production were simulated. Significant enhancement of N2O production from denitrification was evident in both Methylocystaceae-dominant and Methylococcaceae-dominant enrichments, albeit to a greater extent in the former, signifying the comparative potency of methanobactin-mediated copper sequestration, while implying the presence of alternative copper abstraction mechanisms for Methylococcaceae. These observations support that copper-mediated methanotrophic enhancement of N2O production from denitrification is plausible where methanotrophs and denitrifiers cohabit.

IMPORTANCE Proteobacterial methanotrophs—groups of microorganisms that utilize methane as a source of energy and carbon—have been known to employ unique mechanisms to scavenge copper, namely, utilization of methanobactin, a polypeptide that binds copper with high affinity and specificity. Previously the possibility that copper sequestration by methanotrophs may lead to alteration of cuproenzyme-mediated reactions in denitrifiers and consequently increase emission of potent greenhouse gas N2O has been suggested in axenic and coculture experiments. Here, a suite of experiments with rice paddy soil slurry cultures with complex microbial compositions were performed to corroborate that such copper-mediated interplay may actually take place in environments cohabited by diverse methanotrophs and denitrifiers. As spatial and temporal heterogeneity allows for spatial coexistence of methanotrophy (aerobic) and denitrification (anaerobic) in soils, the results from this study suggest that this previously unidentified mechanism of N2O production may account for a significant proportion of N2O efflux from agricultural soils.

INTRODUCTION

Methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the most influential greenhouse gases apart from CO2, with estimated contributions of 16% and 6.2%, respectively, to global greenhouse gas emissions over a 100-year time frame (1). Biological sources and sinks significantly impact both atmospheric CH4 and N2O pools. That is, methanotrophs consume much (up to 100%) of CH4 originating from methanogenesis, balancing the global CH4 budget (2). Similarly, N2O produced via microbially mediated nitrification and denitrification is offset by N2O reduction mediated by microbes capable of expressing and utilizing nitrous oxide reductases (NosZ) (3–5). Collectively, the relative abundance and activity of different microbial groups are critical in determining if any particular environment is a net source or sink of these potent greenhouse gases.

Methanotrophy has become a rather comprehensive term following recent discovery of extremophilic verrucomicrobial methanotrophs, nitrite-reducing anaerobic NC-10 methanotrophs, and archaeal anaerobic methanotrophs (6–9); however, except for certain specialized extreme habitats, “conventional” aerobic proteobacterial methanotrophs often dominate methane oxidation in situ, especially in terrestrial systems (e.g., oxic-anoxic interfaces of rice paddy soils and landfill cover soils), as observed in recent metagenomic analyses (10, 11). Proteobacterial methanotrophs are phylogenetically subdivided into gammaproteobacterial and alphaproteobacterial subgroups (12). Both of these organismal groups utilize particulate and/or soluble methane monooxygenases (MMOs) encoded by pmo and mmo operons, respectively, and these MMOs are currently known as the only enzymes capable of preferentially catalyzing the oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH (13). Of the two forms of MMOs, the particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) has been regarded as the prevalent form in most terrestrial environments, and the majority of proteobacterial methanotroph genomes sequenced to date contain only the pmo operon(s) (14). The expression and activity of pMMO are strongly dependent on copper, although the exact role of copper in pMMO remains unanswered (12, 15, 16).

Due to the dependency of pMMO activity on copper, pMMO-expressing methanotrophs have high demands for copper (17). Not surprisingly, methanotrophs have developed effective copper uptake mechanisms, presumably to cope with limited copper availability in situ. Some alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs of the Methylocystaceae family produce and excrete methanobactin, a modified peptide ∼800 to 1,300 Da in size that chelates copper with the highest affinity among known metal chelators (empirical copper-binding constants range between 1018 and 1058 M−1, depending on the experimental protocol used) (18). Copper-bound methanobactin is transported into the cell via a TonB-dependent transporter and presumably utilized for synthesis of a functional pMMO complex (19, 20). The genes encoding the methanobactin polypeptide precursor (mbnA) and the enzymes involved in its post-translational modifications have been identified in many alphaproteobacterial methanotroph genomes (roughly half of >40 genomes currently available in the NCBI database), and methanobactins isolated from seven distinct strains of Methylocystaceae methanotrophs have been chemically characterized, suggesting that the capability to synthesize and utilize methanobactin is a widespread, but not universal, trait for Methylocystaceae methanotrophs (18, 21–24).

In CH4-rich, copper-depleted environments, these copper acquisition mechanisms of methanotrophs may interfere with other biogeochemical reactions catalyzed by cuproenzymes. Several key enzymes involved in the biological nitrogen cycle, including bacterial and archaeal ammonia monooxygenases (AMOs), copper-dependent NO2− reductases (NirK), and N2O reductases (NosZ), require copper ions for their activity (25–27). The impact on NosZ expression and activity would be particularly consequential from an environmental perspective, as NosZ-catalyzed N2O reduction is the only identified biological or chemical N2O sink in the environment, and no copper-independent alternative pathway for N2O reduction to N2 has been identified to date (3, 28). In fact, methanobactin-mediated inhibition of NosZ activity was recently experimentally verified in vitro using simple, well-defined cocultures of M. trichosporium OB3b and several denitrifier strains possessing nosZ, suggesting the possibility of increased N2O emissions in situ where methanotrophs and denitrifiers coexist (29). Oxic-anoxic interfaces and the vadose zones with fluctuating water content would provide settings in organic- and nitrogen-rich soils, where co-occurrence of obligately aerobic methanotrophy and obligately anaerobic denitrification is possible (30, 31). Whether such an N2O production mechanism is truly relevant in the field, however, is not yet known, as neither methanobactin production nor its influence on denitrifiers has been observed in complex microbiomes such as agriculture soils.

As a follow-up to our previous study documenting the impact of methanobactin-producing methanotroph on denitrification and N2O production in simple cocultures, the current study investigated further the potential ecological relevance of this methanotroph-denitrifier interaction by introducing microbial complexity and competition into the picture. The susceptibility of soil’s complex denitrifying consortia to methanobactin-mediated alteration was examined with (i) denitrifying enrichments amended with exogenous addition of methanobactin and (ii) stimulation of native alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs of the Methylocystaceae family. Furthermore, the consequence of competition of alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs versus gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs on denitrification and associated N2O production was examined with soil slurry microcosms augmented with various amounts of M. trichosporium OB3b before CH4 enrichment.

RESULTS

The effect of methanobactin from M. trichosporium OB3b on N2O production in denitrifying soil enrichments.

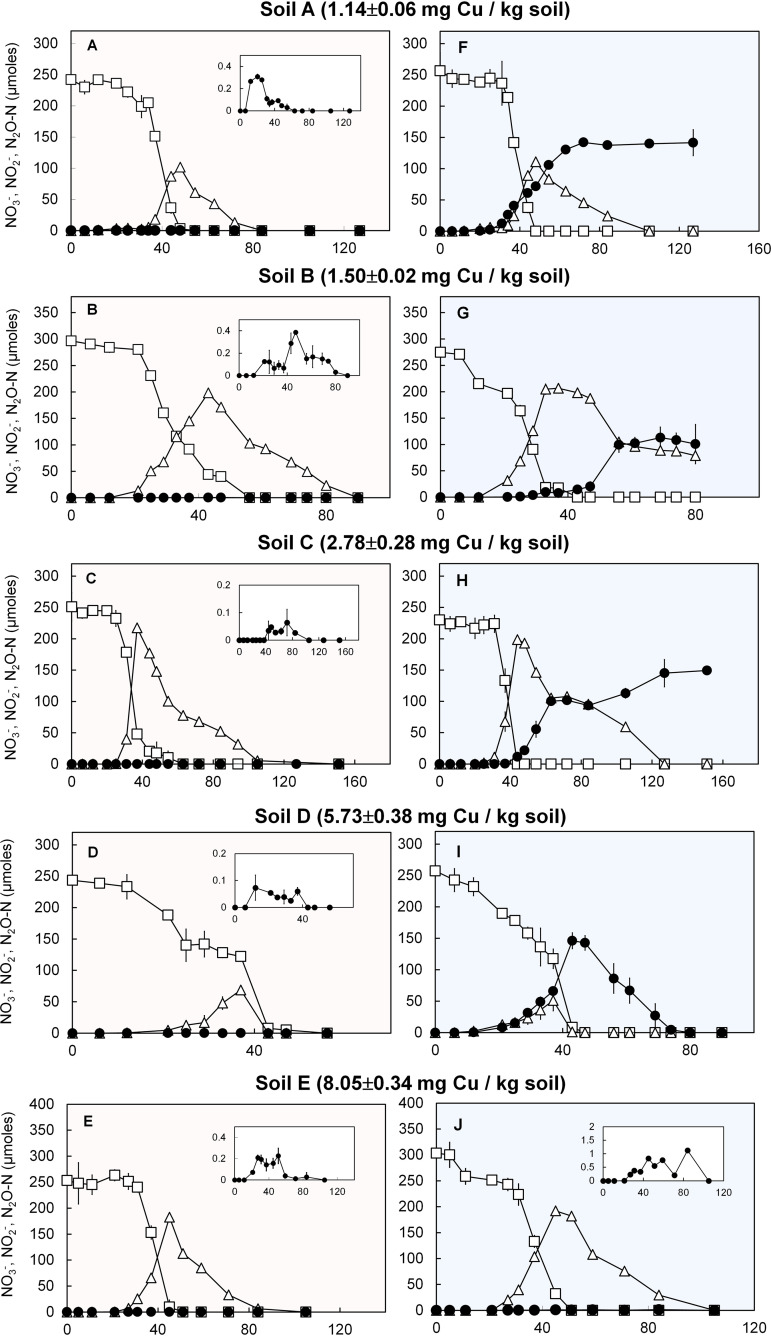

The effect of the methanobactin isolated from M. trichosporium OB3b (MB-OB3b) on N2O production was examined with NO3−-reducing enrichments of five rice paddy soils with various physicochemical properties (Fig. 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Without added MB-OB3b, the amount of accumulated N2O-N did not exceed 0.2% of ∼250 µmol NO3− initially added to the reaction vessels at any time in any of the enrichment cultures, despite four out of five soil samples being slightly acidic at 5.8 < pH < 6.3 (Fig. 1A to E). In contrast, substantial N2O accumulation was observed in soil slurry cultures amended with 10 µM MB-OB3b, with the exception of the soil with the highest copper content (Fig. 1F to J). Persistent N2O accumulation was observed in the enrichments prepared with the soils with the lowest copper content (soil A, 1.14 ± 0.06 mg Cu/kg dry weight; soil B, 1.50 ± 0.02 mg Cu/kg dry weight), with 138 ± 2 and 102 ± 11 µmol N2O-N produced from denitrification of 257 ± 29 and 275 ± 5 µmol NO3−, respectively. Although the nonstoichiometric N2O production suggested partial N2O reduction activity, no further N2O reduction was observed for at least 24 h after completion of denitrification in either enrichment. Inhibition of NO2− reduction was also evident in the soil B enrichment (Fig. 1G). Persistent N2O accumulation and delayed NO2− reduction were observed also with the enrichment prepared with soil C, which had a higher copper content (2.78 ± 0.28 mg Cu/kg dry weight) (Fig. 1H). The enrichments prepared with soils with the highest copper contents (soil D, 5.73 ± 0.38 mg Cu/kg dry weight; soil E, 8.05 ± 0.34 mg Cu/kg dry weight) did not persistently accumulate N2O, even with 10 µM methanobactin added; however, the maximum amount of transiently accumulated N2O was significantly higher (P < 0.05) with methanobactin than without. No significant NO3− or NO2− reduction was observed in any of the sterilized controls, and N2O production over 120 h of abiotic incubation yielded <1.0 µmol N2O-N, precluding the possibility that abiotic N2O production contributed significantly to N2O produced in the NO3−-reducing soil enrichments (data not shown). These results demonstrated that methanobactin can inhibit N2O and/or NO2− reduction in complex microbial consortia, but the effect may vary, depending on soil properties.

FIG 1.

Denitrification of 250 µmol (5 mM) NO3− added to 50-ml rice paddy soil suspensions in 160-ml serum bottles amended without (A to E; shaded light red) and with (F to J; shaded blue) 10 μM OB3b-MB. The copper contents of the rice paddy soils used for preparation of the suspensions were 1.14 (A and F), 1.50 (B and G), 2.78 (C and H), 5.73 (D and I), and 8.05 (E and J) mg Cu/kg dry weight. The time series of the average amounts (μmol per vessel) of NO3− (□), NO2− (△), and N2O (●) are presented with the error bars representing the standard deviations from triplicate samples. The inserts are magnifications of the N2O monitoring data.

Denitrification and N2O accumulation in a soil microbial consortium enriched with indigenous Methylocystaceae methanotrophs.

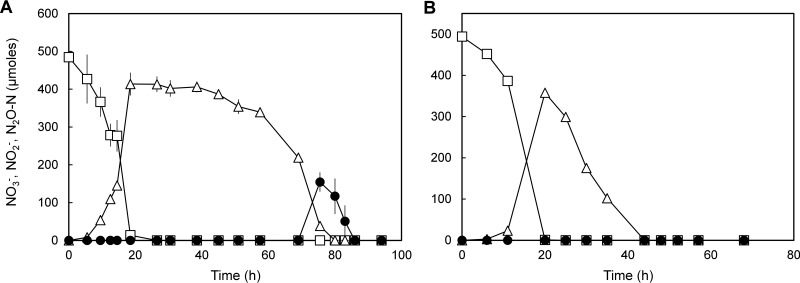

To observe whether indigenous soil methanotrophs are capable of altering soil denitrification and enhancing N2O production with methanobactin as the mediator, denitrification was observed with a Methylocystaceae-dominant quasi-steady-state culture extracted from a chemostat (Fig. 2; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The copy number of eubacterial 16S rRNA genes in the quasi-steady-state reactor culture was (1.52 ± 0.02) × 106 copies ml−1. Alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs of the Methylocystaceae family were the dominant bacterial population, with 78% of the 16S rRNA reads assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) affiliated with this taxon, while the OTUs assigned to the gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs (the Methylococcaceae family) constituted a minority group, with 1.5% relative abundance. Nonmethanotrophic taxa identified in the reactor culture included Chitinophagaceae (7.3%), Pseudomonadaceae (1.4%), and Mycobacteriaceae (1.3%). The most abundant nirK and nosZ genes recovered from the metagenome of the chemostat culture were most closely affiliated in terms of translated amino acid sequences to Methylocystis sp. strain Rockwell (69% of recovered nirK genes) and Methylocystis sp. strain SC2 (93% of recovered nosZ genes), both of which are the only nirK and nosZ genes found in sequenced alphaproteobacterial methanotroph genomes (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The other nirK genes recovered with >1% relative abundance (among the recovered nirK sequences) included those most closely affiliated with the genera Mesorhizobium (16%), Bauldia (3.5%), Panacibacter (3.1%), Pseudomonas (1.8%), and Hypomicrobium (1.4%). The most abundant non-methanotrophic nosZ genes included those affiliated with the genera Flavobacterium (3.4%; clade II) and Pseudomonadas (2.5%; clade I). The coverage of nirS genes was substantially lower than that of nirK genes (2.1 × 10−3 nirS/recA compared to 0.133 total nirK/recA and 4.2 × 10−2 non-Methylocystis nirK/recA). The recovered nirS genes included those affiliated with the genera Bradyrhizobium (29.0% of recovered nirS genes), Zoogloea (41.0%), and Acidovorax (31.9%).

FIG 2.

(A) Progression of denitrification in the 50-ml enrichment cultures (in 160-ml serum bottles with N2 headspace) extracted from the Methylocystaceae-dominant chemostat. One milliliter of separately prepared denitrifier enrichment culture was added to the enrichment cultures at t = 0. To a set of controls (B), CuCl2 was added to a concentration of 2 μM before incubation. The changes to the amounts of NO3− (□), NO2− (△), and N2O (●) in the culture vessels were monitored. The error bars represent the standard deviations from triplicate samples.

The sole unique mbnA sequence assembled from the shotgun metagenome reads exhibited high similarity to mbnA sequences of organisms affiliated with the Methylocystis genus (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The quantitative PCR (qPCR) quantification targeting the Methylocystaceae mbnA genes estimated 8.1 ± 1.8 × 104 copies ml−1, which translated to an mbnA/16S rRNA ratio of 0.054. Furthermore, the mbnA transcript/gene ratio was 19.5 ± 4.9, as determined using reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR), indicating that the mbnA gene was actively transcribed during quasi-steady-state operation of the reactor.

Reduction of NO3− was observed immediately after addition of the denitrifying inoculum to the degassed CH4-enriched culture extracted from the chemostat and was unaffected by Cu2+ amendment (Fig. 2B). Repression of NO2− reduction was apparent in the culture without Cu2+ amendment, as no significant decrease in NO2− concentration was observed for ∼20 h after maximum NO2− accumulation was observed (414 ± 29 μmol NO2 at t = 18.5 h). Eventual reduction of NO2− led to transient accumulation of N2O, and the maximum amount of N2O observed before it was presumably reduced to N2 was 155 ± 25 μmol N2O-N (∼32% of added NO3−-N). Such apparent partial repression of NO2− and N2O reduction was absent in the samples amended with 2 μM Cu2+. NO2− reduction progressed without any apparent lag, and the amount of N2O in the vessel did not increase higher than 0.09 ± 0.01 μmol N2O-N before it was consumed. These observations suggest that alteration of copper availability by methanobactin-producing Methylocystaceae methanotrophs had a substantial effect on denitrification and N2O reduction in the broader microbial community.

Effects of altered community compositions of methanotrophic enrichments on denitrification and N2O production upon transition to anoxia.

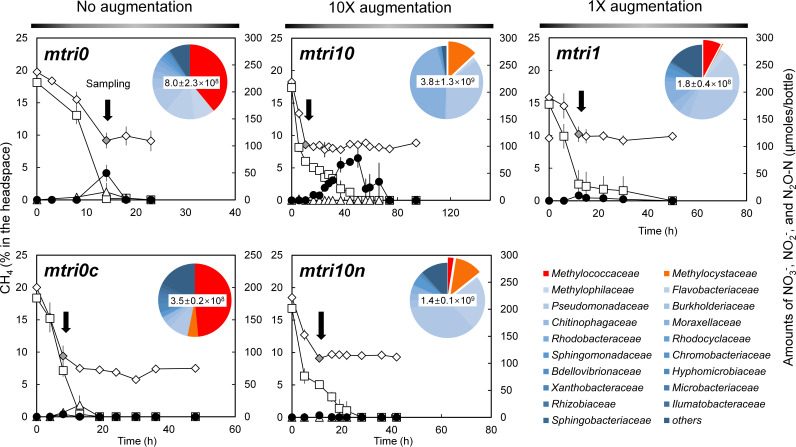

Methanotroph-enriched microbiomes with different ratios of methanobactin-producing Methylocystaceae to gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs were mimicked in soil slurry microcosms by adding various amounts of M. trichosporium OB3b precultures to rice paddy soil slurries before batch enrichment with 20% (vol/vol) CH4 (Fig. 3). The 16S rRNA gene copy number of Methylococcaceae methanotrophs in the soil sample was estimated to be (6.5 ± 1.2) × 106 copies g wet weight soil−1 from their relative abundance (0.41%) and the total bacterial 16S rRNA copy number [(1.6 ± 0.3) × 109 bacterial 16S rRNA copies g wet weight soil−1]. Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b pmoA copy numbers in the CH4-enriched slurries were 0, (1.2 ± 0.2) × 106, and (3.3 ± 0.7) × 108 per ml in the cultures that had been augmented with M. trichosporium OB3b pmoA copy numbers in quantities matching 0, 1, and 10 times the estimated 16S rRNA gene copy numbers affiliated with Methylococcaceae methanotrophs (referred to as mtri0, mtri1, and mtri10, respectively). The 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing of the same samples estimated the relative abundances of Methylocystaceae methanotrophs to be 0.15, 0.35 and 13.0%, respectively (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). The relative abundances of Methylococcaceae methanotrophs were 39, 7.7, and 0%, respectively, in the same samples.

FIG 3.

Monitoring of CH4 oxidation and subsequent denitrificationand N2O production in rice paddy soil suspensions augmented with M. trichosporium OB3b (or ΔmbnAN mutant) cells prior to incubation to quantities with their pmoA copy numbers matching 0 (mtri0 and mtri0c), 1 (mtri1), and 10 (mtri10 and mtri10n) times the estimated Methylococcaceae 16S rRNA gene copy numbers in the suspensions. The Cu-replete control, to which 2 μM CuCl2 was added (mtri1c), and the control augmented with ΔmbnAN mutant of M. trichosporium (mtri10n) were included. The time series of the amounts (μmol per vessel) of NO3− (□), NO2− (△), and N2O (●) and the headspace concentrations (%) of CH4 (◇) are presented with the error bars representing the standard deviations of triplicate samples. The pie charts embedded in the panels illustrate the microbial community compositions of the enrichment cultures at the time points indicated by the black arrows. The numbers in the center of the pie charts are the estimates of bacterial 16S rRNA copy numbers per ml of culture at the indicated time points. The detailed microbial community compositions are presented in Table S4.

In the mtri0 culture, the maximum amount of accumulated N2O was 49.6 ± 14.5 μmol N2O-N and the duration of N2O accumulation was shorter than 10 h (Fig. 3). The maximum observed N2O accumulation (78.2 ± 16.4 μmol N2O-N at t = 50 h) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) and the duration of N2O accumulation substantially longer (68.5 h) in the mtri10 cultures, in which Methylocystaceae methanotrophs outnumbered Methylococcaceae methanotrophs. The decrease in the amount of NO3− observed during active CH4 oxidation (t < 10.5 h) was presumably due to assimilation, as denitrification was unlikely to occur before O2 depletion. Thus, N2O accumulation resulting from dissimilatory reduction of NO3− between 10.5 and 94 h was near stoichiometric, albeit transient, in the mtri10 cultures. In the mtri1 cultures, the maximum amounts of accumulated N2O were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those in either the mtri0 or mtri10 cultures, in line with the substantially lower methanotroph population.

In the negative-control experiment performed with the ΔmbnAN mutant strain added to the soil suspension in place of the wild-type M. trichosporium OB3b (referred to as mtri10n), the maximum amount of N2O accumulated in the vessel was limited to 0.27 ± 0.09 μmol N2O-N, despite the Methylocystaceae dominance of the methanotrophic population, as indicated by the high M. trichosporium OB3b pmoA copy numbers [(1.2 ± 0.7) × 108 per ml] and the low Methylococcaceae/Methylocystaceae population ratio (0.21) in the mtri10n culture (Fig. 3). The results of this control experiment confirmed that the enhanced N2O accumulation of the Methylocysteceae-dominant enrichment was due to copper sequestration by methanobactin produced by M. trichosporium OB3b. Also notable was the obvious dissimilarity observed in the microbial community compositions between the enrichments with the OB3b wild-type strain and the ΔmbnAN mutant strain (Fig. 3; Table S4). The additional set of control experiments performed with 2.0 μM CuCl2 added to the soil-only, and thus Methylococcaceae-dominant, samples (referred to as mtri0c), suggested that the instantaneous N2O accumulation observed in the Methylococcaceae-dominant culture could also be explained as the effect of Cu2+ sequestration by the methanotrophic population. The maximum N2O production (3.75 ± 1.25 μmol N2O-N at t = 106 h) was ∼13 times lower with Cu2+ added than without, despite the abundance of Methylococcaceae family of methanotrophs [48.5% of (3.5 ± 0.2) × 108 eubacterial 16S rRNA copies ml−1].

DISCUSSION

Copper deficiency has been suggested as a potential cause for N2O emission from denitrification taking place in terrestrial and aquatic environments (32–34). In a previous study, Chang et al. demonstrated, using simplified pure-culture and coculture experiments, that MB-OB3b lowered the copper availability of the medium such that N2O reduction was substantially repressed in denitrifiers (29). Whether methanobactin-mediated N2O emission enhancement is relevant to actual soil environments with much more intricate microbiome complexity remained to be resolved, however. The results of the experiments in this study, although performed under well-controlled laboratory conditions, showed that methanobactin-enhanced N2O emissions may actually occur in soil environments with complex microbiomes. Methanobactin addition exerted significant influence on denitrification carried out by the soils’ indigenous microbial consortia, demonstrating that the diverse denitrifying community was still susceptible to methanobactin-mediated copper deprivation. Furthermore, the N2O emission enhancement observed with the Methylocystaceae methanotroph-enriched reactor culture provided unprecedented experimental evidence of indigenous alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs influencing N2O emission from denitrifiers. Observation of substantial mbnA transcription and the absence of this N2O emission enhancement effect in the copper-amended sample supported that methanobactin produced by the indigenous Methylocystaceae methanotrophs was likely the cause of the increased N2O production from denitrification. Additionally, the increased N2O production observed in soil enrichments with broadly varied Methylocystaceae/Methlycoccaceae ratios suggested that methanotrophic population composition in situ may be a major determinant of the copper-mediated N2O emission enhancement, while also suggesting the existence of an additional mechanism via which methanotrophs affect N2O reduction in denitrifiers.

Evidence of the effect of methanobactin on the soil microbial consortia apart from N2O emission enhancement could also be discerned. Delays in NO2− reduction during the progression of denitrification were observed in some, but not all, of the denitrifying enrichments incubated in the presence of OB3b-MB capable of producing methanobactin. At least two distinct forms of nitrite reductases are known to mediate NO2− to NO reduction in denitrifiers: the copper-dependent nitrite reductase NirK and copper-independent cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase NirS (35). In the previous investigation by Chang et al., indeed, NO2− reduction by NirK-utilizing Shewanella loihica, but not NirS-utilizing denitrifiers, was affected by methanobactin-mediated Cu deprivation (29). The environmental conditions that select for enrichment of either NirK- or NirS-utilizing organisms remain unclear, and abundances of nirS- or nirK-possessing organisms vary in rice paddy soils (36). Possibly, the relative abundances and activities of the NirK- and NirS-utilizing denitrifiers may have varied in the denitrifying consortia prepared with soils A to E, explaining the nonuniform responses of the denitrifiers in the consortia to copper deprivation.

The shotgun metagenome analyses of the methanotrophic chemostat culture identified organisms affiliated with the Methylocystaceae family as the dominant nirK-possessing organisms. Furthermore, the nosZ gene affiliated with Methylocystis sp. strain SC2 was the dominant nosZ gene in the chemostat culture (37). These observations are certainly interesting, as the only Methylocystaceae nirK and nosZ sequences available in the database are of the nirK gene found in the genome of Methylocystis sp. strain Rockwell and the nosZ gene found in a plasmid of Methylocystis sp. strain SC2 (37, 38). Both genes were unique, in the sense that they both shared <75% translated amino acid sequence identity with any other NirK or NosZ sequences in the NCBI database, and no previous study has reported recovery of these Methylocystaceae nirK and nosZ sequences in metagenome/metatranscriptome analyses. Despite the potential significance of the discovery, the possibility that the Methylocystaceae methanotrophs harboring these genes might have significantly affected NO2− reduction and N2O production in the anoxic batch incubations was highly unlikely. Both Methylocystis sp. strain Rockwell and Methylocystis sp. strain SC2 have been confirmed to have the inability to grow anaerobically, and neither strain has been confirmed to be capable of reducing NO2− or N2O utilizing NirK or NosZ, respectively (37, 38). Therefore, although the collected data are insufficient to completely rule out the possibility that these Methylocystaceae populations significantly contributed to denitrification and N2O production and consumption, it is more plausible that the N2O dynamics in the anoxic cultures were largely determined by nonmethanotrophic facultatively anaerobic organisms carrying nirK, nirS, and/or nosZ genes.

In this metagenome analysis, many of the nonmethanotrophic organisms putatively harboring nirK or nirS and those putatively harboring nosZ belonged to different taxa, suggesting that N2O production and N2O consumption may have been carried out by distinct organismal groups in the anoxic batch experiments performed with this chemostat culture. That is, the dominant non-Methylocystaceae nirK and nosZ genes recovered from the chemostat metagenome were those affiliated with Rhizobiales and Bacteriodetes, respectively, and only nirK and nosZ affiliated with Pseudomonaceae were recovered with similar coverage. This metagenomic observation may imply that the alteration of copper availability brought about by methanobactin-producing methanotrophs influence N2O emissions from denitrification occurring in modular manner, which may be the more likely case in complex environmental microbiomes (39, 40).

The distinctive contrast between the microbial compositions of the mtri10 and mtri10n enrichments implied that methanobactin had a pronounced impact on the overall microbial community. The microbial community formed from enrichment on CH4 and acetate after augmentation with the wild-type strain OB3b (mtri10) carried a distinctively large proportion of Moraxellaceae (44.7%). Such abundance of Moraxellaceae was not observed in the enrichment with augmented ΔmbnAN mutant cells (mtri10n), suggesting that this enrichment of Moraxellaceae was due to the presence of methanobactin produced by M. trichosporium OB3b. The most probable explanations are a selective bactericidal property and/or reduced copper bioavailability to competing organisms with high demands for copper (18, 22). The relative abundance of other phylogenetic groups, including Methylophilaceae and Flavobactericeae, also varied substantially across the treatments. Unlike the case for Moraxellaceae, however, the experimental evidence was not sufficient to attribute these alterations to the effect of methanobactin.

The observed N2O emission enhancement in methanotroph-enriched cultures dominated by the Methylococcaceae family (i.e., the mtri0 enrichment, albeit to a level lower than that observed in the mtri10 enrichment), was unanticipated, as none of the sequenced genomes of the methanotrophs belonging to this phylogenetic group has been reported to produce methanobactin encoded by mbnA (18). What is evident from the experimental results, however, is that copper competition was central to N2O production in these enrichments, as copper amendment removed the N2O-accumulating phenotype, as observed in the mtri0c enrichment. Indications that Methylomicrobium album BG8 and Methylococcus capsulatus Bath may utilize methanobactin-like copper chelators had been previously reported (41, 42). These Methylococcaceae strains tested positive on the Cu-CAS (chromo azurol S) plate assays, and the putative methanobactin-like compound of ∼1,000 Da in size isolated from the spent medium of M. capsulatus Bath bound Cu with 1:1 stoichiometry; however, the genomic basis for synthesis of these compounds in Methylococcaceae methanotrophs has not yet been elucidated. Another copper uptake mechanism involving copper-binding periplasmic membrane proteins MopE and CorA has been identified in M. capsulatus Bath and M. album BG8, respectively (43, 44). The estimated binding constants of these putative copper chelators are tens of orders of magnitudes lower than those reported for methanobactin from Methylocystaceae methanotrophs; however, if present at large concentrations, the copper chelators may still exert a significant impact on the Cu availability. Which, if any, of these mechanisms was responsible for copper withholding from denitrifiers and N2O reducers in the Methylococcaceae-dominant enrichments cannot be determined with the current data and warrants future investigation.

One of the most prominent characteristics of soil environments is their spatial and temporal heterogeneity, in terms of both physicochemical makeup and microbial composition (45, 46). In CH4-enriched soil environments such as rice paddy and landfill soils, proteobacterial methanotrophs are often reported to be abundant, with pmoA copy numbers ranging between 107 and 1010 gene copies g dry soil−1 (47–49). These numbers are of the same magnitude as the methanotrophic populations in the enrichment cultures observed to induce N2O production from the cohabiting denitrifying population in the laboratory experiments performed here. Methanotroph population density at local microsites may even be higher, especially at the oxic-anoxic interfaces, where CH4 and O2, the essential substrates of proteobacterial methanotrophs, are both available (48). Thus, it would not be surprising to find local concentrations of methanobactin-producing Methylocystaceae methanotroph communities in microniches within the soil sufficiently dense as to cause copper deficiency to cohabiting NosZ-utilizing N2O reducers. At a microscopic scale, temporal oxic-to-anoxic shifts or vice versa would constantly occur at the oxic-anoxic interfaces, allowing for spatial coexistence of O2-dependent CH4 oxidation and O2-inhibited denitrification (31). The substrates of denitrification, NO3− and NO2−, may be transported from oxic surface soils or supplied via oxidation of organic N or NH4+ in situ at the oxic-anoxic interface with intermittently available O2 (30). Periodic oxic-anoxic transitions may also take place in the vicinity of the water table in upland soils, as precipitation and drying cause fluctuations in the elevation of the water table (50). In such settings, aerobic microbial processes of nitrification and methanotrophy and anaerobic microbial processes of denitrification and methanogenesis may alternate at a larger scale. Snapshot views of physicochemical and biological states of soils may cast doubt on the likelihood of the methanotroph-enhanced N2O emissions occurring in actual soil environments; however, with these spatial and temporal shifts in consideration, the suggested mechanism is plausible in any terrestrial environment with high organic and nitrogen content. Thus, in approximating greenhouse gas budgets from environments such as rice paddy soils, landfill cover soils, wetland soils, and upland agricultural soils, N2O arising from the copper-mediated interaction between methanotrophs and N2O reducers needs to be considered for development of a more accurate prediction model for N2O emissions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil sampling and characterization.

Soil samples were collected from an experimental rice paddy located at Gyeonggido Agricultural Research & Extension Services in Hwaseong, South Korea (37°13′21″N, 127°02′35″E), in August 2017 and four rice paddies near Daejeon, South Korea (36°22′41″N, 127°19′50″E), in December 2018 (Table S1). Samples were collected from the top layer of soil (0 to 20 cm below the overlying water). After removal of plant material, soil samples were stored in sterilized jars, which were then filled to the brim with rice paddy water. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory in a cooler filled with ice and stored at 4°C until use. A small portion (∼50 g) of each collected soil was stored at −80°C for DNA analyses.

The physicochemical characteristics of these soil samples were analyzed directly after sampling. The soil pH was measured by suspending 1 g wet weight soil in 5 ml Milli-Q water. Total nitrogen and carbon content of air-dried soil samples were analyzed with a Flash EA 1112 elemental analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For measurements of NH4+, NO3−, and NO2− content in soil samples, 1 g air-dried soil was suspended in 5 ml 2 M KCl solution and shaken at 200 rpm for an hour. After settling the suspension for 10 min, the supernatant was passed through a 0.2-μm-pore membrane filter (Advantec MFS, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The filtrate was analyzed using colorimetric quantification methods. The total copper content of soil samples was measured with an Agilent ICP-MS 7700S inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA) after pretreatment with boiling aqua regia (51).

Media and culture conditions.

Unless otherwise mentioned, modified nitrate mineral salts (NMS) medium was used for enrichment of methanotrophs in soil microbial consortia and incubation of axenic cultures of the wild-type and ΔmbnAN mutant strains of M. trichosporium OB3b (52). The medium contained per liter, 1 g MgSO4·7H2O (4.06 mM), 0.5 g KNO3 (4.95 mM), 0.2 g CaCl2·2H2O (1.36 mM), 0.1 ml of 3.8% (wt/vol) Fe-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.5 ml of 0.02% (wt/vol) Na2MoO4·2H2O solution, and 0.1 ml of the 10,000× trace element stock solution prepared with 5 g liter−1 FeSO4·7H2O, 4 g liter−1 ZnSO4·7H2O, 200 mg liter−1 MnCl2·7H2O, 500 mg liter−1 CoCl2·6H2O, 100 mg liter−1 NiCl2·6H2O, 150 mg liter−1 H3BO3, and 2.5 g liter−1 EDTA. All glassware used in this study was equilibrated in a 5 N HNO3 acid bath overnight before use to reduce background contamination of copper to <0.01 μM in media. Forty-milliliter aliquots of the medium were distributed into 250-ml serum bottles, and the bottles were sealed with butyl rubber stoppers (Geo-Microbial Technologies, Inc., Ochelata, OK) and aluminum caps. After autoclaving, the media were amended with 0.2 ml of 200× Wolin vitamin stock solution, and 500 mM pH 7.0 KH2PO4–Na2HPO4 solution was added to a final concentration of 5 mM (53). High-purity CH4 (>99.95%; Deokyang Co., Ulsan, South Korea) replaced 20% of the headspace air. After inoculation, culture bottles were incubated in dark at 30°C with shaking at 140 rpm.

Analytical procedures.

Headspace CH4 concentrations were measured using a GCMS-QP2020 gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (Shimadzu Cooperation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an SH-Rt-Q-BOND column (30 m in length by 0.32-mm inner diameter with 10-μm film thickness). The injector and oven temperatures were set to 150 and 100°C, respectively, and helium was used as the carrier gas. Headspace N2O concentrations were measured with an HP 6890 series gas chromatograph equipped with a HP-PLOT/Q column and an electron capture detector (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). The injector, oven, and detector temperatures were set to 200, 85, and 250°C, respectively. For each CH4 or N2O measurement, 50 or 100 μl of gas sampled using a Hamilton 1700-series gas-tight syringe (Reno, NV) was manually injected into the gas chromatographs. The dissolved N2O concentrations were calculated from the headspace concentrations using the dimensionless Henry’s law constant of 1.92 at 30°C (54, 55). The dissolved concentrations of NO3− and NO2− were determined colorimetrically using the Griess reaction (56). As the assay measures NO2−, vanadium chloride (VCl3) was used to reduce NO3− to NO2−. The concentration of NH4+ was measured using the salicylate method (57).

The total bacterial population was quantified using TaqMan-based quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCRs) targeting the eubacterial 16S rRNA gene (1055f, 5′-ATGGCTGTCGTCAGCT-3′; 1392r, 5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTAC-3′; and Bac1115_probe, 5′-CAACGAGCGCAACCC-3′) (58). The primers and probe set exclusively targeting the pmoA gene (encoding the β subunit of particulate methane monooxygenase) of M. trichosporium OB3b (OB3b_pmoAf, 5′-CGCTCGACATGCGGATAT-3′; OB3b_pmoAr, 5′-TTTCCCGATCAGCCTGGT-3′; and OB3b_ pmoA_probe, 5′-AGCCACAGCGCCGGAACCA-3′) were designed de novo using Geneious v9.1.7 software (Biomatters, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) and used for quantification of M. trichosporium OB3b cells. qPCR assays were performed with a QuantStudio 3 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The calibration curves for the targeted genes were constructed using serial dilutions of PCR2.1 vectors (Thermo Fisher Scientific) carrying the target fragments. For each qPCR quantification, three biological replicates were processed separately. The complete list of the primers and probes used in this study is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primer/probe sets used for qPCR and RT-qPCR analyses

| Primer/probe set | Sequence | Target gene | Amplicon length (bp) | Slope | y intercept | Amplification efficiency | R2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA 1055f | 5′-ATGGCTGTCGTCAGCT-3′ | Bacterial 16S rRNA | 338 | −3.30 | 37.7 | 101.1 | 0.996 | 59 |

| 16S rRNA 1392r | 5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTAC-3′ | |||||||

| Bac1115_probe | 5′-CAACGAGCGCAACCC-3′ | |||||||

| OB3b_pmoAf | 5′-CGCTCGACATGCGGATAT-3′ | pmoA | 266 | −3.38 | 36.4 | 97.8 | 0.998 | This study |

| OB3b_pmoAr | 5′-TTTCCCGATCAGCCTGGT-3′ | |||||||

| OB3b_ pmoA_probe | 5′-AGCCACAGCGCCGGAACCA-3′ | |||||||

| mbnAf672 | 5′-GCTCGTCATACCATTCGGG-3′ | mbnA | 100 | −3.32 | 37.7 | 100.1 | 0.999 | This study |

| mbnAr771 | 5′-GCTTGGCGATACGGATGGTC-3′ | |||||||

| lucf | 5′-TACAACACCCCAACATCTTCGA-3′ | Luciferase control mRNA | 67 | −3.37 | 37.1 | 98.0 | 0.999 | 71 |

| lucr | 5′-GGAAGTTCACCGGCGTCAT-3′ | |||||||

Monitoring of denitrification and N2O production in rice paddy soil suspensions amended with methanobactin from M. trichosporium OB3b.

Methanobactin was isolated from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b cultures and purified as previously described (59). The effects of MB-OB3b on N2O emissions were examined with suspensions of five rice paddy soils (soils A to E) with various physicochemical properties. Each soil suspension was prepared by suspending 1 g of air-dried rice paddy soil in 50 ml Milli-Q water in 160-ml serum bottles, and the headspace was replaced with N2 gas after sealing. Methanobactin stock solution was prepared by dissolving 10 μmol (11.5 mg) freeze-dried methanobactin in 10 ml Milli-Q water. The stock solution was equilibrated in an anaerobic chamber filled with 95% N2 and 5% H2 (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI) for 1 h to remove dissolved O2, and 0.5 ml of the solution was added to the soil suspensions. Potassium nitrate and sodium acetate were then added to final concentrations of 5 and 10 mM, respectively. Soil suspensions were incubated with shaking at 140 rpm at 30°C. The headspace N2O concentration and the dissolved concentrations of NO3− and NO2− were monitored until depletion of NO3− and NO2−. The dissolved concentrations of NH4+ were also monitored to ensure the absence of significant dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) activity. Negative controls were prepared identically, but without methanobactin amendment. Abiotic control experiments with sterilized soils with and without methanobactin amendment were performed with 5 mM NO3− or NO2− added, to confirm that the abiotic contribution to N2O production was minimal.

Monitoring of denitrification and N2O production in subcultures extracted from a quasi-steady-state chemostat culture of Methylocystaceae-dominated soil methanotrophs.

A continuous methanotrophic enrichment culture was prepared with soil E. The inoculum was generated by suspending 1 g (wet weight) soil in 50 ml NMS medium in a sealed 160-ml serum vial with air headspace. The vials were fed twice with 41 μmol CH4, yielding a headspace concentration of ∼0.5% (vol/vol) upon each injection. After the initial batch cultivation, 20 ml of the enrichment was transferred to 5 liters NMS medium in a 6-liter fermentor controlled with a BioFlo 120 Bioprocess Control Station (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The gas stream carrying a relatively low CH4 concentration (0.5% [vol/vol] in air) was fed continuously at a rate of 145 ml min−1 through a gas diffuser to stimulate growth of Methylocystaceae methanotrophs, as previous fed-batch and chemostat incubation of rice paddy soils with a continuous supply of 20% (vol/vol) CH4 resulted in domination by gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs (60). The reactor culture was maintained in the dark at pH 6.8 and 30°C with agitation at 500 rpm. After the initial fed-batch operation, the reactor culture was transitioned to continuous operation with the dilution rate set to 0.014 h−1. After the quasi-steady state was attained, as indicated by constant effluent cell density and CH4 concentration, 1.0-ml aliquots were collected, and the pellets were stored at −20°C for analyses of the microbial community composition and denitrification functional genes and qPCR quantification of mbnA and 16S rRNA genes. Additionally, 0.4-ml aliquots were treated with RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and stored at −80°C for reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR) analyses of mbnA expression.

Triplicate anoxic batch cultures were prepared by distributing 50 ml culture harvested from the running quasi-steady-state reactor to 160-ml serum bottles and flushing the headspace with N2 gas. A denitrifying enrichment was prepared separately by incubating 1 g (wet weight) of soil E in 100 ml anoxic NMS medium amended with 10 mM sodium acetate. One milliliter of this denitrifier inoculum was added to the methanotroph enrichments, to which 20 mM sodium acetate was added as the electron donor for denitrification. The cultures were amended with or without 2 μM CuCl2, the culture vessels were incubated in the dark with shaking at 140 rpm at 30°C, and the changes to the amounts of NO3−, NO2−, and N2O-N in the vessels were monitored until no further change was observed.

Denitrification and N2O production in soil enrichments with altered methanotrophic population composition.

Various amounts of preincubated M. trichosporium OB3b cells were added to rice paddy soil slurry microcosms before enrichment with CH4, to artificially vary the proportion of the methanobactin-producing subgroup among the total methanotroph population. The total indigenous gammaproteobacterial methanotroph population in the soil suspension was approximated by multiplying the total eubacterial 16S rRNA copy number per ml suspension (as determined with qPCR) by the proportion of the 16S rRNA gene sequences affiliated with gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs (all affiliated with the Methylococcaceae family) in soil B (as computed from the MiSeq amplicon sequencing data [see Table S5 in the supplemental material]). The numbers of M. trichosporium OB3b cells in the precultures were estimated with the TaqMan qPCR targeting the duplicate pmoA genes of the strain. The M. trichosporium OB3b preculture was used to prepare soil suspensions with the augmented Methylocystaceae population. The ratios of M. trichosporium OB3b pmoA copy numbers to the estimated 16S rRNA gene copy numbers of the Methylococcaceae methanotrophs were set to 1 and 10 in the 40-ml suspensions. It should be stressed that these ratios cannot be directly translated to cell number ratios, as the numbers of 16S rRNA genes in the completed genomes of gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs deposited in the NCBI GenBank database vary between 1 and 4. Soil suspensions without M. trichosporium OB3b augmentation were also prepared. As a negative control, the ΔmbnAN mutant strain of M. trichosporium OB3b was added in place of the wild-type strain OB3b (61). A copper-replete control was also prepared for the experimental condition with no M. trichosporium OB3b augmentation by amending a subset of cultures with 2 μM CuCl2.

The soil suspensions were prepared by adding 0.1 g wet weight of the soil to the autoclaved modified NMS medium bottles prepared as described above (40 ml NMS medium in 250-ml serum bottles). After sealing of the bottles and addition of M. trichosporium OB3b or ΔmbnAN mutant preculture or CuCl2 to the calculated target concentrations, 20% of the headspace was replaced with CH4 and sodium acetate was added to a final concentration of 5.0 mM. When the headspace CH4 concentration decreased to 10%, the headspace was replenished with an 80:20 mixture of air and CH4 and the cultures were amended with 200 μmol NO3− and 400 μmol sodium acetate. At each sampling time point, the headspace N2O concentration was measured and 0.5 ml of the culture was collected from each bottle for determination of NO3−, NO2−, and NH4+ concentrations. The cell pellets collected immediately after the CH4 concentration dropped to ∼10% were subjected to qPCR targeting strain OB3b pmoA genes and eubacterial 16S rRNA genes. The 16S rRNA amplicon sequences of the pellets were also analyzed.

Microbial community composition analyses and prediction of genomic potentials for denitrification reactions from 16S rRNA amplicon sequences.

Genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The V6 to V8 region of the 16S rRNA gene amplified with the universal primers 926F (5′-AAACTYAAAKGAATTGRCGG-3′)/1392R (5′-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3′) was sequenced at Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea), using a MiSeq sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) (62). The raw sequence data were processed using the QIIME pipeline v1.9.1 with the parameters set to default values (63). After demultiplexing and quality trimming, the filtered sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the USEARCH algorithm, and the OTUs were assigned a taxonomic classification using the RDP classifier against the Silva SSU database release 132. The raw sequences were deposited into the NCBI SRA database (BioProject accession number PRJNA685001).

Metagenomic analysis of the chemostat enrichment and RT-qPCR targeting mbnA.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing of the reactor culture was performed at Macrogen, Inc., using a HiSeq X sequencing platform (Illumina) generating ∼5 Gb of paired-end reads with 150-bp read length (BioProject accession number PRJNA684997). The raw short reads were quality screened using Trimmomatic v0.36 with default parameters (64). The processed reads were assembled into contigs using metaSPAdes v3.12.0, and coding sequences were identified using Prodigal v2.6.3 (65, 66). The Hidden Markov model (HMM) algorithms for nirS, nirK, clade I and clade II nosZ, and recA were downloaded from the FunGene database (http://fungene.cme.msu.edu/). A previously constructed HMM algorithm for mbnA was used for screening of mbnA genes (67). The predicted contigs were screened for these targeted genes using hmmsearch in HMMER 3.1b2, with the E value set to 10−5. The identified gene sequences were further validated by running blastx against the RefSeq database, with the E value cutoff set to 10−3. For taxonomy assignment, the translated amino acid sequences of the screened functional genes were searched against NCBI’s nonredundant protein database (nr) using blastp, with an E value cutoff of 10−10. The quality-trimmed reads were mapped onto the screened functional gene sequences using the bowtie2 v2.3.4.1 software, with the parameters set to default values (68). The coverage of each target gene was calculated using the genomecov command of the BEDtools v2.17.0 software and normalized by its length (69).

A degenerate primer set was designed with the sole unique mbnA sequence recovered from the shotgun metagenome data and publicly available Methylocystis mbnA sequences with >85% translated amino acid sequence identity with this metagenome-derived mbnA sequence (Fig. S1), using Geneious v9.1.7 software (Biomatters, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). This primer set (672f, 5′-GCTCGTCATACCATTCGGG-3′; and 771r, 5′-GCTTGGCGATACGGATGGTC-3′) was used for quantification of mbnA genes and transcripts in the chemostat culture (Fig. S1). Extraction and purification of RNA were performed using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and RNA MinElute kit (Qiagen), respectively, and reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the established protocols (70). As previously described, a known quantity of luciferase control mRNA (Promega, Madison, WI) was used as the internal standard to correct for RNA loss during the extraction and purification procedure. The mbnA transcript copy numbers were normalized to mbnA copy numbers in the genomic DNA.

Statistical analyses.

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the average values are presented with the error bars representing the standard deviations from triplicate samples. The statistical significance of the data from two different experimental conditions was tested with two-sample t tests, and statistical comparisons between two different time points were tested with one-sample t tests. The SPSS Statistics 24 software (IBM Corp., NY) was used for statistical analyses.

Data availability.

The raw short reads from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenome sequencing were deposited in the NCBI BioProject database under accession numbers PRJNA684997 and PRJNA685001.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (grants 2017R1D1A1B03028161 and 2015M3D3A1A01064881), in part by “R&D Center for Reduction of Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases (201700242002)” funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment, and by the United States Department of Energy (DE-SC0020174). The authors were also financially supported by the Brain Korea 21 Plus Project (grant 21A20132000003).

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Edenhofer O, Pichs-Madruga R, Sokona Y, Farahani E, Kadner S, Seyboth K, Adler A, Baum I, Brunner S, Eickemeier P. 2014. Climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bridgham SD, Cadillo-Quiroz H, Keller JK, Zhuang Q. 2013. Methane emissions from wetlands: biogeochemical, microbial, and modeling perspectives from local to global scales. Glob Chang Biol 19:1325–1346. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon S, Song B, Phillips RL, Chang J, Song MJ. 2019. Ecological and physiological implications of nitrogen oxide reduction pathways on greenhouse gas emissions in agroecosystems. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 95:fiz066. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiz066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CM, Spor A, Brennan FP, Breuil M-C, Bru D, Lemanceau P, Griffiths B, Hallin S, Philippot L. 2014. Recently identified microbial guild mediates soil N2O sink capacity. Nat Clim Chang 4:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domeignoz-Horta LA, Spor A, Bru D, Breuil M-C, Bizouard F, Leonard J, Philippot L. 2015. The diversity of the N2O reducers matters for the N2O:N2 denitrification end-product ratio across an annual and a perennial cropping system. Front Microbiol 6:971. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ettwig KF, Zhu B, Speth D, Keltjens JT, Jetten MSM, Kartal B. 2016. Archaea catalyze iron-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:12792–12796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609534113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettwig KF, Butler MK, Le Paslier D, Pelletier E, Mangenot S, Kuypers MMM, Schreiber F, Dutilh BE, Zedelius J, de Beer D, Gloerich J, Wessels HJCT, van Alen T, Luesken F, Wu ML, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Op den Camp HJM, Janssen-Megens EM, Francoijs K-J, Stunnenberg H, Weissenbach J, Jetten MSM, Strous M. 2010. Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria. Nature 464:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nature08883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Teeseling MCF, Pol A, Harhangi HR, van der Zwart S, Jetten MSM, Op den Camp HJM, van Niftrik L. 2014. Expanding the verrucomicrobial methanotrophic world: description of three novel species of Methylacidimicrobium gen. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:6782–6791. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01838-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunfield PF, Yuryev A, Senin P, Smirnova AV, Stott MB, Hou S, Ly B, Saw JH, Zhou Z, Ren Y, Wang J, Mountain BW, Crowe MA, Weatherby TM, Bodelier PLE, Liesack W, Feng L, Wang L, Alam M. 2007. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450:879–882. doi: 10.1038/nature06411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HJ, Jeong SE, Kim PJ, Madsen EL, Jeon CO. 2015. High resolution depth distribution of Bacteria, Archaea, methanotrophs, and methanogens in the bulk and rhizosphere soils of a flooded rice paddy. Front Microbiol 6:639. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebert J, Perner M. 2015. Impact of preferential methane flow through soil on microbial community composition. Eur J Soil Biol 69:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2015.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semrau JD, DiSpirito AA, Yoon S. 2010. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:496–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawton TJ, Rosenzweig AC. 2016. Biocatalysts for methane conversion: big progress on breaking a small substrate. Curr Opin Chem Biol 35:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knief C. 2015. Diversity and habitat preferences of cultivated and uncultivated aerobic methanotrophic bacteria evaluated based on pmoA as molecular marker. Front Microbiol 6:1346. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi DW, Kunz RC, Boyd ES, Semrau JD, Antholine WE, Han JI, Zahn JA, Boyd JM, Mora AM, DiSpirito AA. 2003. The membrane-associated methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and pMMO-NADH:quinone oxidoreductase complex from Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. J Bacteriol 185:5755–5764. doi: 10.1128/jb.185.19.5755-5764.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semrau JD, DiSpirito AA, Gu W, Yoon S. 2018. Metals and methanotrophy. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02289-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02289-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasubramanian R, Smith SM, Rawat S, Yatsunyk LA, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. 2010. Oxidation of methane by a biological dicopper centre. Nature 465:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD, Murrell JC, Gallagher WH, Dennison C, Vuilleumier S. 2016. Methanobactin and the link between copper and bacterial methane oxidation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:387–409. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00058-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu W, Ul Haque MF, Baral BS, Turpin EA, Bandow NL, Kremmer E, Latley A, Zischka H, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. 2016. A TonB-dependent transporter is responsible for methanobactin uptake by Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:1917–1923. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03884-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dassama LMK, Kenney GE, Ro SY, Zielazinski EL, Rosenzweig AC. 2016. Methanobactin transport machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:13027–13032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603578113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandow N, Gilles VS, Freesmeier B, Semrau JD, Krentz B, Gallagher W, McEllistrem MT, Hartsel SC, Choi DW, Hargrove MS, Heard TM, Chesner LN, Braunreiter KM, Cao BV, Gavitt MM, Hoopes JZ, Johnson JM, Polster EM, Schoenick BD, Umlauf AM, DiSpirito AA. 2012. Spectral and copper binding properties of methanobactin from the facultative methanotroph Methylocystis strain SB2. J Inorg Biochem 110:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Graham DW, DiSpirito AA, Alterman MA, Galeva N, Larive CK, Asunskis D, Sherwood PMA. 2004. Methanobactin, a copper-acquisition compound from methane-oxidizing bacteria. Science 305:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1098322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Ghazouani A, Baslé A, Gray J, Graham DW, Firbank SJ, Dennison C. 2012. Variations in methanobactin structure influences copper utilization by methane-oxidizing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:8400–8404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112921109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenney GE, Goering AW, Ross MO, DeHart CJ, Thomas PM, Hoffman BM, Kelleher NL, Rosenzweig AC. 2016. Characterization of methanobactin from Methylosinus sp. LW4. J Am Chem Soc 138:11124–11127. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godden JW, Turley S, Teller DC, Adman ET, Liu MY, Payne WJ, LeGall J. 1991. The 2.3 angstrom X-ray structure of nitrite reductase from Achromobacter cycloclastes. Science 253:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1862344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown K, Tegoni M, Prudêncio M, Pereira AS, Besson S, Moura JJ, Moura I, Cambillau C. 2000. A novel type of catalytic copper cluster in nitrous oxide reductase. Nat Struct Biol 7:191–195. doi: 10.1038/73288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawton TJ, Ham J, Sun T, Rosenzweig AC. 2014. Structural conservation of the B subunit in the ammonia monooxygenase/particulate methane monooxygenase superfamily. Proteins 82:2263–2267. doi: 10.1002/prot.24535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson AJ, Giannopoulos G, Pretty J, Baggs EM, Richardson DJ. 2012. Biological sources and sinks of nitrous oxide and strategies to mitigate emissions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:1157–1168. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang J, Gu W, Park D, Semrau JD, DiSpirito AA, Yoon S. 2018. Methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b inhibits N2O reduction in denitrifiers. ISME J 12:2086–2089. doi: 10.1038/s41396-017-0022-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, Winther M, Priemé A, Blunier T, Christensen S. 2017. Hot spots of N2O emission move with the seasonally mobile oxic-anoxic interface in drained organic soils. Soil Biol Biochem 115:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.08.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush T, Diao M, Allen RJ, Sinnige R, Muyzer G, Huisman J. 2017. Oxic-anoxic regime shifts mediated by feedbacks between biogeochemical processes and microbial community dynamics. Nat Commun 8:789. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00912-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan MJ, Gates AJ, Appia-Ayme C, Rowley G, Richardson DJ. 2013. Copper control of bacterial nitrous oxide emission and its impact on vitamin B12-dependent metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:19926–19931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314529110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Twining BS, Mylon SE, Benoit G. 2007. Potential role of copper availability in nitrous oxide accumulation in a temperate lake. Limnol Oceanogr 52:1354–1366. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.4.1354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granger J, Ward BB. 2003. Accumulation of nitrogen oxides in copper‐limited cultures of denitrifying bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr 48:313–318. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.1.0313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zumft WG. 1997. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:533–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bannert A, Kleineidam K, Wissing L, Mueller-Niggemann C, Vogelsang V, Welzl G, Cao Z, Schloter M. 2011. Changes in diversity and functional gene abundances of microbial communities involved in nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification in a tidal wetland versus paddy soils cultivated for different time periods. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:6109–6116. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01751-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dam B, Dam S, Blom J, Liesack W. 2013. Genome analysis coupled with physiological studies reveals a diverse nitrogen metabolism in Methylocystis sp. strain SC2. PLoS One 8:e74767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein LY, Bringel F, DiSpirito AA, Han S, Jetten MSM, Kalyuzhnaya MG, Kits KD, Klotz MG, Op den Camp HJM, Semrau JD, Vuilleumier S, Bruce DC, Cheng J-F, Davenport KW, Goodwin L, Han S, Hauser L, Lajus A, Land ML, Lapidus A, Lucas S, Médigue C, Pitluck S, Woyke T. 2011. Genome sequence of the methanotrophic alphaproteobacterium Methylocystis sp. strain Rockwell (ATCC 49242). J Bacteriol 193:2668–2669. doi: 10.1128/JB.00278-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roco CA, Bergaust LL, Bakken LR, Yavitt JB, Shapleigh JP. 2017. Modularity of nitrogen-oxide reducing soil bacteria: linking phenotype to genotype. Environ Microbiol 19:2507–2519. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lycus P, Bøthun KL, Bergaust L, Shapleigh JP, Bakken LR, Frostegård Å. 2017. Phenotypic and genotypic richness of denitrifiers revealed by a novel isolation strategy. ISME J 11:2219–2232. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi DW, Do YS, Zea CJ, McEllistrem MT, Lee SW, Semrau JD, Pohl NL, Kisting CJ, Scardino LL, Hartsel SC, Boyd ES, Geesey GG, Riedel TP, Shafe PH, Kranski KA, Tritsch JR, Antholine WE, DiSpirito AA. 2006. Spectral and thermodynamic properties of Ag(I), Au(III), Cd(II), Co(II), Fe(III), Hg(II), Mn(II), Ni(II), Pb(II), U(IV), and Zn(II) binding by methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. J Inorg Biochem 100:2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon S, Kraemer SM, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. 2010. An assay for screening microbial cultures for chalkophore production. Environ Microbiol Rep 2:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karlsen OA, Berven FS, Stafford GP, Larsen Ø, Murrell JC, Jensen HB, Fjellbirkeland A. 2003. The surface-associated and secreted MopE protein of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) responds to changes in the concentration of copper in the growth medium. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:2386–2388. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.4.2386-2388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson KA, Ve T, Larsen Ø, Pedersen RB, Lillehaug JR, Jensen HB, Helland R, Karlsen OA. 2014. CorA is a copper repressible surface-associated copper(I)-binding protein produced in Methylomicrobium album BG8. PLoS One 9:e87750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prosser JI. 2015. Dispersing misconceptions and identifying opportunities for the use of 'omics' in soil microbial ecology. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:439–446. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baveye PC, Otten W, Kravchenko A, Balseiro-Romero M, Beckers É, Chalhoub M, Darnault C, Eickhorst T, Garnier P, Hapca S, Kiranyaz S, Monga O, Mueller CW, Nunan N, Pot V, Schlüter S, Schmidt H, Vogel H-J. 2018. Emergent properties of microbial activity in heterogeneous soil microenvironments: different research approaches are slowly converging, yet major challenges remain. Front Microbiol 9:1929. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alam MS, Jia Z. 2012. Inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrogenous fertilizers in a paddy soil. Front Microbiol 3:246. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reim A, Lüke C, Krause S, Pratscher J, Frenzel P. 2012. One millimetre makes the difference: high-resolution analysis of methane-oxidizing bacteria and their specific activity at the oxic-anoxic interface in a flooded paddy soil. ISME J 6:2128–2139. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma K, Conrad R, Lu Y. 2013. Dry/wet cycles change the activity and population dynamics of methanotrophs in rice field soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4932–4939. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00850-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davidson EA, Verchot LV, Cattânio JH, Ackerman IL, Carvalho JEM. 2000. Effects of soil water content on soil respiration in forests and cattle pastures of eastern Amazonia. Biogeochemistry 48:53–69. doi: 10.1023/A:1006204113917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sastre J, Sahuquillo A, Vidal M, Rauret G. 2002. Determination of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn in environmental samples: microwave-assisted total digestion versus aqua regia and nitric acid extraction. Anal Chim Acta 462:59–72. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(02)00307-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whittenbury R, Phillips KC, Wilkinson JF. 1970. Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. Microbiology 61:205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolin EA, Wolfe RS, Wolin MJ. 1964. Viologen dye inhibition of methane formation by Methanobacillus omelianskii. J Bacteriol 87:993–998. doi: 10.1128/JB.87.5.993-998.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon S, Sanford RA, Löffler FE. 2015. Nitrite control over dissimilatory nitrate/nitrite reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3510–3517. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00688-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sander R. 2015. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos Chem Phys 15:4399–4981. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-4399-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. 2001. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baethgen WE, Alley MM. 1989. A manual colorimetric procedure for measuring ammonium nitrogen in soil and plant Kjeldahl digests. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 20:961–969. doi: 10.1080/00103628909368129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ritalahti KM, Amos BK, Sung Y, Wu Q, Koenigsberg SS, Löffler FE. 2006. Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2765–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2765-2774.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bandow NL, Gallagher WH, Behling L, Choi DW, Semrau JD, Hartsel SC, Gilles VS, DiSpirito AA. 2011. Isolation of methanobactin from the spent media of methane-oxidizing bacteria. Methods Enzymol 495:259–269. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386905-0.00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, Kim DD, Yoon S. 2018. Rapid isolation of fast-growing methanotrophs from environmental samples using continuous cultivation with gradually increased dilution rates. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:5707–5715. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8978-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gu W, Baral BS, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. 2017. An aminotransferase is responsible for the deamination of the N-terminal leucine and required for formation of oxazolone ring A in methanobactin of Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02619-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02619-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Miyamoto Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, Oyaizu H, Tanaka R. 2002. Development of 16S rRNA-gene-targeted group-specific primers for the detection and identification of predominant bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5445–5451. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.11.5445-5451.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hyatt D, Chen GL, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform 11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA. 2017. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res 27:824–834. doi: 10.1101/gr.213959.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenney GE, Rosenzweig AC. 2013. Genome mining for methanobactins. BMC Biol 11:17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quinlan AR. 2014. BEDTools: the Swiss-army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinform 47:11.12.1–11.12.34. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoon S, Cruz-García C, Sanford R, Ritalahti KM, Löffler FE. 2015. Denitrification versus respiratory ammonification: environmental controls of two competing dissimilatory NO3−/NO2− reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. ISME J 9:1093–1104. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson DR, Lee PKH, Holmes VF, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2005. An internal reference technique for accurately quantifying specific mRNAs by real-time PCR with application to the tceA reductive dehalogenase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3866–3871. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3866-3871.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw short reads from 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenome sequencing were deposited in the NCBI BioProject database under accession numbers PRJNA684997 and PRJNA685001.