Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of viral disease has been demonstrated for infections caused by flaviviruses and influenza viruses; however, antibodies that enhance bacterial disease are relatively unknown. In recent years, a few studies have directly linked antibodies with exacerbation of bacterial disease.

KEYWORDS: antibody, capsular polysaccharide, enhancement, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, lipopolysaccharide, proteases

ABSTRACT

Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of viral disease has been demonstrated for infections caused by flaviviruses and influenza viruses; however, antibodies that enhance bacterial disease are relatively unknown. In recent years, a few studies have directly linked antibodies with exacerbation of bacterial disease. This ADE of bacterial disease has been observed in mouse models and human patients with bacterial infections. This antibody-mediated enhancement of bacterial infection is driven by various mechanisms that are disparate from those found in viral ADE. This review aims to highlight and discuss historic evidence, potential molecular mechanisms, and current therapies for ADE of bacterial infection. Based on specific case studies, we report how plasmapheresis has been successfully used in patients to ameliorate infection-related symptomatology associated with bacterial ADE. A greater understanding and appreciation of bacterial ADE of infection and disease could lead to better management of infections and inform current vaccine development efforts.

INTRODUCTION

Antibodies are a critical part of the human humoral immune response that aid in the elimination of pathogenic microorganisms via a range of mechanisms (1). This depth in function can be attributed to their fragment antigen-binding (Fab) and fully crystallizable (Fc) structural domains joined by a flexible amino acid stretch termed the hinge region (2, 3). To neutralize pathogens, the Fab region binds to antigenic structures, typically localized at the cell surface, preventing direct interactions with host cells. The Fab region can also bind bacterial toxins, preventing their interaction with host cellular receptors and neutralizing their activity. In addition to this, antibodies can recruit potent effector molecules through interactions with their Fc regions, initiating a variety of clearance mechanisms precluding pathogenic infection. The specific effector molecules recruited are dependent on class and subclass of antibody involved (4). Despite these well-characterized protective aspects, antibodies that instead amplify disease have also been described, through phenomena such as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) and vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (VAERD).

ADE is best known for its role in viral infections; such observations have been reported for flaviviruses (5–7) and influenza viruses (8–10). Recently, viral ADE of infection has been of increased interest for its possible role in exacerbating coronavirus infections (11, 12). ADE of viral infection occurs when suboptimal antibodies (i.e., low affinity, concentration, and/or specificity) cannot completely neutralize the etiologic pathogen, thereby resulting in increased binding, uptake, and replication, leading to inflammation (11). Additionally, binding of these antibodies naturally activates cytokine release or complement cascade for host protection but, when unchecked, may result in a fatal chain of events due to persistent tissue damage coupled with chronic inflammation.

VAERD is a unique clinical syndrome first observed in the 1960s when whole-inactivated viral vaccines for measles and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were administered in children (13). Along with aberrant T cell responses (14), the use of a limiting dose or conformationally incorrect antigen in vaccines can result in the production of nonneutralizing antibodies (15). As mentioned previously, this generation of nonneutralizing antibodies runs the potential risk of binding pathogenic microorganisms—but not blocking or clearing them—allowing them to replicate or permit formation of immune complexes activating complement pathways associated with several inflammatory disorders (15).

In a few cases, antibodies that enhance bacterial infection and disease have been described, although the mechanisms underpinning this phenomenon are distinct from those for viral ADE. In this review, we first cover research highlights of ADE of bacterial infection in animal studies and human cohorts. We then discuss the proposed molecular mechanisms and review other instances where these mechanisms have been reported. Finally, we examine current therapies for ADE of bacterial disease.

ANTIBODY-DEPENDENT ENHANCEMENT OF BACTERIAL INFECTION

The first hints of a specifically induced serum factor that may enhance bacterial infection dates back to 1894. Pfeiffer and Issaeff found that naive guinea pigs given serum from guinea pigs previously infected with Vibrio cholerae were more susceptible to intraperitoneal infection by the Vibrio species (16). However, it was not until later that a specific antibody was confirmed to enhance some bacterial infections (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Antibody dependent enhancement of bacterial infections

| Bacterial species | Disease model | Virulence enhancement | Proposed antibody virulence properties | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro models | ||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Human respiratory epithelial cells | Enhanced bacterial attachment | Virulence enhancement by antibody proteolysis | 17 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Human respiratory epithelial cells | Enhanced bacterial attachment | Antibody-mediated increase in adhesion | 18 |

| Mouse models | ||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Pneumonia | Increased mortality and bacterial burden | Antibody-mediated increase in adhesion | 18, 135 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Gonorrhea | Increased bacterial burden and duration of infection | Antibody-mediated serum resistance | 19, 20 |

| Enteric bacteria | Sepsis | Increased mortality | Antibody-mediated protection from bactericidal killing | 21 |

| Human cohorts | ||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Gonorrheal infection | Increased susceptibility | Antibody-mediated serum resistance | 22 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Bronchiectasis lung infections | Worse lung function | Antibody-mediated serum resistance | 23 |

Antibodies that enhances bacterial infection have been demonstrated within a few in vitro and mouse model studies (Table 1). For Streptococcus pneumoniae, bacterium-specific antibody responses enhance bacterial attachment to respiratory cells (17). In a mouse model of Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia, the passive immunization of a monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for the capsule increased mortality and bacterial burdens in the blood, lung, and spleen (18). The presence of these antibodies was found to increase adhesion of the bacteria to respiratory epithelial cells (18). In a mouse model of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection, passive immunization with a MAb toward the reduction modifiable protein (Rmp) abrogated the protective effects of the 2c7 MAb (19), causing both increased bacterial burden and duration of infection (20). Finally, preexisting serum IgG specific for enteric bacteria correlated with worse survival in a mouse model of sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (21).

Evidence of antibodies that enhance bacterial infection in humans has been more difficult to discern. The anti-Rmp antibody responsible for enhancing mouse infection of N. gonorrhoeae was also found to increase susceptibility to N. gonorrhoeae in a study of 243 adult women (22). Based on findings from our work, the presence of high titers of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-specific IgG2 in serum is associated with worse lung function in patients with bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (23).

Although there are only a few cases with direct evidence of bacterial ADE, the mechanisms underlying these antibody-mediated pathologies have been described in a wide array of bacterial infections. Here, we will discuss the prevalence and potential mechanisms of bacterial ADE of infection, including antibody-mediated serum resistance, virulence enhancement by antibody proteolysis, antibody enhancement of adhesion, and antibody-mediated protection from phagocytosis.

ANTIBODY-MEDIATED SERUM RESISTANCE

The complement system is a vital part of the immune response against bacterial pathogens, consisting of multiple soluble factors acting in a cascade to either promote opsonophagocytosis or directly kill bacteria through pore formation and cell lysis (24). The complement system can be activated though three distinct pathways, (i) the classical, (ii) alternate, and (iii) lectin; however, all three converge to form the membrane attack complex (MAC) which can insert into the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, leading to cell death. The classical pathway of complement-mediated killing requires the binding of a specific antibody to an antigen on the cell surface of pathogens. Bound antibodies recruit the C1q component, leading to the complement cascade and formation of the MAC (24).

Resistance to complement-mediated lysis, commonly known as serum resistance, is an essential virulence trait of many pathogenic bacteria as it allows survival in the bloodstream (25, 26). Bacteria have developed numerous virulence factors to assist them in resisting the bactericidal effects of serum (27). Briefly, Gram-positive bacteria are innately resistant to MAC insertion due to the thick layer of peptidoglycan on their cell surface (28). For Gram-negative bacteria, the production of polysaccharide capsule, O-antigen-positive lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or lipooligosaccharide (LOS) has been shown to be important for serum resistance by providing a steric barrier protecting the outer membrane from insertion of the MAC (29–31). In spite of this defined role, many O-antigen- or capsule-expressing strains still remain sensitive to serum killing (23, 32, 33). Recently, the roles of other proteins such as Lpp in Escherichia coli have been shown to be vital for resistance (34). Some species also reduce complement activation via recruitment of complement regulatory proteins within the host to their cell surface (35). Antigenic variation and the shedding of surface-bound complement factors also provide resistance by circumventing pathogen recognition mechanisms (27). Finally, some species are capable of offensive maneuvers in the form of enzyme secretion which bring about degradation/inactivation of complement components or inhibit the formation of MAC (36).

Antibody-mediated serum resistance seems paradoxical due to its accepted role in classically activated complement-mediated killing. However, in both N. gonorrhoeae and P. aeruginosa infection, the antibody associated with enhanced infection or disease has been shown to block or inhibit the complement killing of bactericidal sera. These “blocking antibodies” have now been described for many different species, including Neisseria spp., Brucella spp., Salmonella spp., Proteus spp., and Klebsiella spp. (Table 2). Descriptions of inhibitory sera date back to 1901, when the “Neisser-Wechsberg” phenomenon was described wherein deactivated serum taken from a rabbit repeatedly infected with Vibrio metschnikovii increased the bactericidal effect of normal serum of this strain in moderate amounts but inhibited the bactericidal effect when mixed in large amounts (37). This inhibiting factor was shown to be specific, as it was able to be adsorbed out of the sera using the homologous strain (38). Below, we detail the bacterial diseases for which these antibodies have been described.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of antibody-mediated serum resistance in bacterial infection

| Species | Disease | Organism(s) reported | Antigen | Antibody subtype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae | Respiratory disease | Pigs, guinea pigs | LPS | IgG | 90 |

| Brucella spp. | Brucellosis | Cattle, pigs, rabbits | LPS | IgA/IgG2 | 70, 75, 76 |

| Burkholderia cepacia | Cystic fibrosis | Humans | Unknown | Unknown | 136 |

| Escherichia coli | Pyelonephritis, urosepsis | Humans | LPS | IgG, IgG2 | 78, 82 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | NTHI | Humans | Unknown | IgA | 92 |

| Klebsiella spp. | Pyelonephritis | Humans | Unknown | Unknown | 77, 78 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Gonorrheal disease | Humans | LOS | IgA | 60 |

| Rmp | IgG | 65, 66 | |||

| Neisseria meningitidis | Meningitidis | Humans, rabbit, guineapig, horse | Capsule | IgA, IgG | 39, 40, 137 |

| Lip H.8/Laz | IgA | 46 | |||

| Pili | IgA | 48 | |||

| Proteus mirabilis and P. morganii | Pyelonephritis | Humans | LPS | IgG | 80, 81 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pyelonephritis, lung infections | Humans | LPS | IgG2 | 83–85 |

| Salmonella enterica | Various | Humans | LPS | IgG, IgA, IgM | 86–89 |

| Serratia marcescens | Bacteremia | Humans | LPS | IgG | 50 |

Meningitis: Neisseria meningitidis.

In the 1940s, the first specific description of a factor in humans that blocked serum killing of a bacterial strain was reported. Serum samples taken from patients two weeks after their initially reported infection with Neisseria meningitidis was unable to kill a serum-sensitive strain, in direct contrast to sera taken during the acute phase of infection (39). These convalescent-phase sera were also able to block the killing of otherwise bactericidal normal human sera (NHS). A similar blocking factor was found in multiple patient cohorts (40, 41) and eventually identified as IgA1 binding to capsular polysaccharide of group C meningococcus (42). Adsorbing out all IgA restored bactericidal killing (41), whereas adsorption of all antibody specific for the capsule (42) removed both the inhibition and bactericidal activity, suggesting anti-capsule IgG promoted cell lysis (42). Blocking IgA specific for capsule of various serotypes of N. meningitidis has since been reported in multiple human cohorts (43, 44). Finally, evidence for an anti-capsule IgG antibody that inhibits alternative pathway complement-mediated killing was found in two C2-deficient sisters. One of these sisters when vaccinated with tetravalent meningococcal vaccine (containing capsular polysaccharides from serogroups A, C, W-135, and Y) developed an antibody response that blocked alternative pathway-mediated killing of serogroup W-135. IgG was identified as the blocking antibody and was found to inhibit killing of the W-135 serogroup strain but not a serogroup C strain (45). In contrast to the studies above, IgA was not shown to be involved in the inhibition (45).

Antibodies that inhibit complement-mediated killing also target other outer membrane structures of N. meningitidis. The serogroup B meningococcal capsule is not immunogenic; however, blocking antibodies have been identified against lipoproteins expressed by these strains. The serum samples from 17 healthy individuals were tested for their ability to kill a serogroup B N. meningitidis strain, finding variable killing throughout. Three of the four serum samples with low bactericidal activity were able to block bactericidal killing; however, they were not able not inhibit the killing of the strain by all bactericidal sera. The inhibition was found to be IgG3 specific for two lipoproteins: Lip/H.8 and Laz (46). The aforementioned lipoproteins contain almost identical pentapeptide repeats (×15 and ×8, respectively), and expression of both was required for maximal blocking. Bactericidal activity was able to be restored in sera by adsorbing out these blocking antibodies with synthetic peptide containing the pentapeptide repeats (46).

In humans, α1,3-galactosyl antibodies (anti-Gal) are ubiquitously expressed, making up approximately 1% of total circulating IgG (47). Anti-Gal IgM, IgG, and IgA were found not to bind the LOS of N. meningitidis but bound to the pili of some strains (48). Total serum anti-Gal Ig was found to inhibit complement-mediated killing of pilus-producing N. meningitidis strains. When purified, serum IgA1 and secretory IgA inhibited killing, whereas purified anti-Gal IgG did not (48). Notably, anti-Gal has also been found to bind to LPS of enteric bacterial species such as Klebsiella, Escherichia, Salmonella (49), and Serratia (50).

Disseminated gonococcal infection: Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Antibody has long been shown to be necessary for complement-mediated killing of N. gonorrhoeae. NHS contain bactericidal IgM antibody that can target and kill serum-sensitive isolates of N. gonorrhoeae (51, 52). Strains that cause disseminated gonococcal infection are overwhelmingly serum resistant to NHS (53) but have been shown to be killed by the induction of specific antibodies in serum from convalescent patients (54, 55). In some cases, NHS were found to contain specific IgG antibodies that were able to block the bactericidal effects of both rabbit complement and convalescent-phase sera (56–58). These inhibitory antibodies have been found to be specific for either LOS or outer membrane proteins of N. gonorrhoeae. Antibody to LOS, primarily IgM (51, 59), has been shown to be responsible for a major proportion of bactericidal activity against N. gonorrhoeae (60, 61). In contrast, IgA specific for N. gonorrhoeae LOS isolated from pooled NHS was shown to block the bactericidal killing of IgG-mediated killing of the bacterium (60).

The best-characterized gonococcal antibody that inhibits complement killing is specific for an outer membrane protein: the reduction modifiable protein (Rmp, protein III). Antibody to Rmp has been shown to increase bacterial burden in a mouse model as well as act as a biomarker for susceptibility to N. gonorrhoeae in humans (20, 22). Rmp is a 236-amino-acid (aa) protein that is physically associated with the porin Por and is highly conserved within the genus Neisseria (62–64). Rmp is ubiquitously expressed in N. gonorrhoeae and demonstrates robust immunogenicity (65). IgG specific for Rmp was shown to inhibit bactericidal killing by protective antibodies, whether purified from human sera (65) or as a monoclonal antibody (66), although only one of two monoclonal antibodies directed against Rmp promoted the inhibitory effect (66). Bactericidal activity was able to be restored in nonkilling serum from convalescing patients by selectively adsorbing out the inhibitory anti-Rmp antibody. Recently, antibodies with higher bactericidal activity against N. gonorrhoeae have been induced by using a Rmp deletion strain (67). Rmp does exist in N. meningitidis (class 4 outer membrane protein), but the role of anti-Rmp antibodies in bactericidal killing of that species is unclear. One study identified anti-class 4 antibodies that blocked killing of the strain in one individual (68); however, antibodies specific for class 4 induced by a meningococcal outer membrane vesicle vaccine did not inhibit complement-mediated killing (69).

Brucellosis: Brucella melitensis, B. suis, and B. abortus.

Brucellosis is the leading cause of zoonotic infection in humans worldwide and is caused by multiple bacterial species in the genus Brucella. Brucella spp. are small Gram-negative facultative intracellular coccobacilli, with four species known to have moderate to significant pathogenicity in humans: Brucella melitensis (sheep), Brucella suis (pigs), Brucella abortus (cattle), and Brucella canis (dogs). High titers of specific antibodies to Brucella species, likely serum IgA, are known to inhibit agglutination reactions (53, 64, 70, 71); however, a blocking factor of complement-mediated killing was simultaneously being described. In 1945, Huddleson and colleagues (72) showed that fresh plasma from cattle infected with B. abortus was not able to kill the bacteria when given a source of complement. In addition, this plasma inhibited the action of bactericidal plasma when mixed and was suggested to be antibody (72). Similarly, guinea pigs infected with Brucella had serum that was bactericidal seven days postinfection but unable to kill the strain 30 days postinfection (73). The bactericidal activity of fresh rabbit blood was also found to be inhibited when rabbits were immunized extensively with B. abortus (74). Analysis of rabbit hyperimmune serum indicated that IgA was primarily responsible for the bactericidal inhibition, with addition of IgA blocking the bactericidal effect of IgM or IgG isolated from the sera (75); however, the role of other antibody isotypes could not be ruled out.

The process behind serum bactericidal inhibition in cattle was comprehensively studied by Corbeil et al. (70), where the authors investigated the differences in killing of smooth (O-antigen expressing) and rough (O-antigen negative) strains of B. abortus after infection or immunization with either strain. When specific antibodies were present, killing of the rough strain by serum was increased. In contrast, as specific antibodies increased for the smooth B. abortus, killing of that strain in serum significantly decreased (70). Antibodies involved in the killing inhibition were identified as IgG1 and IgG2, with IgG2 driving significantly more inhibition (70). Other studies have confirmed the blocking factor in bovine serum as IgG and suggested that antibody, under certain conditions, may actually promote establishment of bovine brucellosis (76).

Pyelonephritis: Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Proteus morganii, and Klebsiella aerogenes.

Antibodies that block complement-mediated killing have also been described in pyelonephritis for a range of bacterial species, including Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella spp. (77). In each case, patient sera blocked the ability of NHS to kill the cognate strain in a serum- and strain-specific manner.

In 1972, nine of 48 female patients with urinary tract infections were found to have a serum factor that inhibited NHS killing of their cognate strain (78, 79). Of the nine patients, eight were afflicted with pyelonephritis. Strains isolated from patients with this defect included E. coli serotypes O2, O4, O7, and O75, Proteus morganii, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella spp. (78). This inhibitory factor was investigated in detail for the two patients infected with Proteus spp. and confirmed to be due to IgG specific for LPS (80). Adsorbing out all IgG, or antibody specific for LPS, was sufficient to restore bactericidal activity of the serum (81). Finally, we recently found that 24% of 45 patients with E. coli urosepsis infection had antibodies that inhibited serum killing. These antibodies were IgG2 specific for LPS of the E. coli strain. Isolates taken from patients with these serum-killing inhibitory antibodies were more sensitive to NHS, suggesting the presence of these antibodies was required for these strains to survive in the bloodstream (82).

Bacterial lung infections: Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Recurrent and chronic bacterial lung infections commonly affect those with bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis (CF), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. P. aeruginosa is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these diseases and, once infection is established, is exceedingly difficult to eradicate. The first reported case of a blocking serum factor toward Pseudomonas was Waisbren and Brown’s work (77). By investigating the sera of two patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection, the blocking factor was identified as IgG and was able to be specifically adsorbed from the serum by using the cognate strain isolated from the patient (83). In a study investigating 42 patients with CF and P. aeruginosa infection, six patients of the cohort had serum that was unable to kill their autologous strain, even though it was sensitive to NHS killing (84). Additionally, these sera were able to kill heterologous strains of P. aeruginosa from other patients, suggesting the presence of patient-specific blocking antibodies in these sera (84).

The nature of blocking antibodies to P. aeruginosa was investigated in our study looking at 29 patients with bronchiectasis and chronic P. aeruginosa infection (85). Six of these patients had serum that was unable to kill their cognate strain, despite the isolates being sensitive to NHS killing. As little as 6% of patient serum added to NHS was able to completely inhibit complement-mediated killing. “Inhibitory sera” had significantly higher binding of IgG2 to their autologous strain, and specifically removing these IgG2 antibodies from the sera restored bactericidal activity. Conversely, reintroducing these purified IgG2 antibodies to NHS inhibited complement-dependent killing. Furthermore, antibody specific for the O-antigen component of LPS, but not lipid A, inhibited complement-mediated killing. Thus, IgG2 specific for the O-antigen was responsible for inhibiting complement-mediated killing. Importantly, patients with “inhibitory antibodies” had significantly worse lung function than patients with normal killing serum (23).

Salmonella infection: Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi B and S. Typhimurium.

The first reported case of serum killing inhibitory antibodies against Salmonella spp. was in 1953, when the presence of excess antibodies to Salmonella R antigen (LPS core) was shown to block serum bactericidal activity (86). The study by Waisbren and Brown also reported two patients with inhibitory antibodies to their infecting Salmonella strain; an S. Paratyphi B strain from a patient suffering peritonitis and a rectus abdominus muscle abscess, and an S. Typhimurium strain from a patient suffering septicemia and a splenic abscess (77).

The first detailed study of an inhibitory antibody toward Salmonella was in 2010 when MacLennan and colleagues investigated a cohort of HIV-infected African adults for their serum’s ability to kill two S. Typhimurium strains, one resistant to NHS and one sensitive (87). Within this cohort, 58% of serum samples were not able to kill the sensitive strain, while 28% had lower bactericidal activity than the NHS of the resistant strain. A high titer of anti-S. Typhimurium IgG correlated with less bactericidal killing by the patient sera. The nonkilling sera were able to inhibit the action of NHS. The blocking factor was identified as IgG specific for S. Typhimurium LPS (87). Bactericidal activity was restored in patient sera by either adsorbing out the LPS-specific IgG or deleting O-antigen expression on the surface of the Salmonella strain. In contrast, antibodies targeting outer membrane proteins were found to be bactericidal (87).

In an analysis of 49 healthy adult serum samples, it was found that 48 had robust killing of an S. Typhimurium strain, with antibodies specific for LPS identified as important for the bactericidal activity (88). The single serum unable to kill the strain was found to contain inhibitory antibodies, correlating with anti-LPS IgM. The serum also led to less complement deposition on the bacterial strain. Thus, anti-LPS antibody was found to both promote and inhibit complement-mediated killing (88). This result was supported when it was later shown that any antibody specific for the LPS was able to inhibit complement-mediated killing, although IgA and IgG2 had the strongest association (89). The anti-LPS IgG, when sufficiently diluted, was found to be bactericidal; however, when concentrated from NHS, it resulted in the blocking of complement-mediated killing (89).

Individual cases: Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is a Gram-negative encapsulated coccobacillus that causes acute to chronic respiratory diseases in swine worldwide. An antibody that inhibited complement-mediated killing of the strain was identified in normal swine serum and hyperimmune swine and guinea pig serum. The antibody was IgG specific for A. pleuropneumoniae LPS (90).

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) is a nonencapsulated Gram-negative commensal of the human nasopharynx. However, when present in the lower respiratory tract, it can become an important pathogen associated with conditions such as bronchitis, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (91). IgA, when purified from four of five patients with NTHI infection, inhibited the bactericidal activity of NHS or their own serum to kill their cognate strain (92). Although the IgA is specific for the NTHI strains, the precise target of the inhibitory IgA remains unknown.

Mechanisms underlying antibody-mediated serum resistance.

Antibodies that inhibit the complement-mediated killing of bacteria can belong to various isotypes: IgA, IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 (23, 42, 46, 70, 89). Additionally, these antibodies are specific for a variety of outer membrane structures such as LOS, LPS (core and O-antigen), capsule, lipoproteins, and outer membrane proteins (Table 2). Thus, there are likely multiple mechanisms underpinning the antibody-mediated inhibition. However, there are many similarities between the descriptions of antibody-mediated serum resistance that may be informative.

In many of the cases reviewed here, the antibodies required for complement resistance bind either LPS or LOS. In the case of P. aeruginosa, the antibodies specific for the O-antigen but not the lipid A/core of the LPS were found to be responsible (23). This is reinforced by studies where the inhibition is only found against smooth strains expressing O-antigen (70, 87). We and other groups have previously proposed two possible mechanisms of complement inhibition (23, 87). In both, high titers of antibody bind to the O-antigen of LPS and then exert their inhibitory effect either by (i) activating and depositing complement away from the bacterial membrane or (ii) creating a physical antibody blockade that prevents access of protective antibody and MAC to the cell surface. Evidence currently favors the latter explanation, where multiple studies have found the inhibition of complement-mediated killing to be dependent on high titers of the antibody. In N. meningitidis, if enough IgA was present to form a “blockade,” no amount of IgM could restore bactericidal activity (93). This antibody has been shown to bind and activate MAC formation (23, 87); however, MAC activation is likely not required for complement resistance, as one study determined that removal of the Fc portion from IgA1 did not affect the inhibition (42). Finally, many isotypes of antibody with disparate complement activation have been found to inhibit serum killing.

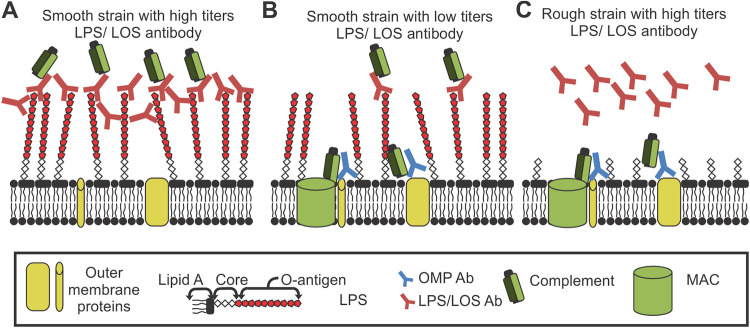

Only one study has found IgM to inhibit serum killing (89), with the majority of evidence indicating that IgM toward LPS is bactericidal in serum (51, 54, 75, 93, 94). We hypothesize that this may be due to the pentameric structure of IgM, which may interfere with the close packing of the antibody required to form the protective barrier. IgM typically has a lower affinity for antigens than other isotypes of antibody. As inhibitory antibodies need to block access of MAC to the membrane, we hypothesize that lower-affinity antibodies may be unable to block this insertion. Thus, we propose a mechanism of action where antibodies at a high titer bind to an abundant antigen that is distal from the cell surface. These antibodies completely cloak the bacteria, creating a physical barrier that prevents MAC insertion into the membrane (Fig. 1A). Antibodies at a low titer in serum cannot cover the entire surface of the bacterium, leading to bactericidal activity (Fig. 1B). Additionally, removal of the target epitope restores complement killing (Fig. 1C). This mechanism could apply to capsule, LPS, LOS, or any antigen that is numerous distal from the cell surface. Differences in the antibody titer or abundance of an antibody target may also explain differences in bactericidal effect.

FIG 1.

Mechanism of cloaking antibody. (A) High-titers antibodies specific for the O-antigen of LOS/LPS form a steric barrier, preventing MAC insertion into the bacterial membrane. (B) Low titers of O-antigen specific antibody do not prevent access to the membrane for both protective antibody and MAC. (C) Lack of O-antigen target allows protective antibody and complement to access bacterial membrane.

Antibodies that protect bacteria from complement-mediated killing using this method have previously been termed inhibitory, blocking, or paradoxical antibodies; however, all these terms are broad or already have multiple uses in the field. We propose that these be termed “cloaking antibodies,” which describes the mechanism of action: complete coverage that gives protection and is distinct from these other aforementioned terms.

Finally, proteins have also been identified as targets for antibodies that inhibit complement-mediated killing: mainly Rmp from N. gonorrhoeae and Lip/H.8 from N. meningitidis. The mechanisms underlying the antibody inhibition are disparate. For Rmp, antibody binds and promotes complement deposition but does not lead to killing. It also can block the bactericidal action of protective antibodies. It is thought that the presence of the anti-Rmp antibody recruits complement proteins away from bactericidal sites of the N. gonorrhoeae to nonbactericidal sites (58). Whether this is due to steric hindrance, as with cloaking antibodies, has yet to be determined. Anti-Lip/H.8 antibodies differ in that their presence reduces complement activation (specifically C4), and although the antibodies are able to block the action of some protective MAbs, they are not able to inhibit the bactericidal action of a MAb to anti-PorA, possibly because PorA is a major and abundant porin of the N. meningitidis membrane (46). Thus, blocking by anti-Lip/H.8 antibodies is due to an overall reduction of complement activation and can be overcome by protective antibodies.

Antibody-mediated serum resistance and disease enhancement.

The causal link between antibody-mediated serum resistance and enhancement of infection is clear in diseases that require serum resistance, such as bacteremia, urosepsis, and meningitis. The presence of the antibody allows otherwise serum-sensitive strains to survive in blood, leading to a higher burden of disease. Indeed, in E. coli urosepsis, the isolates taken from patients with high titers of cloaking antibodies were more sensitive to NHS killing, suggesting that the presence of these antibodies was required for the infection to survive in blood (82). In the case of facultative intracellular Brucella, some authors have speculated that protection from complement killing, while still promoting opsonophagocytosis, may facilitate higher infection of phagocytic cells between lysis/infection cycles (76).

The link between cloaking antibody and disease severity in lung infections, such as those shown in P. aeruginosa, is less obvious, where complement killing is not a main defense against infection in the lung. Lung damage in chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections is usually due to increased inflammation (95, 96). There are many ways antibodies may increase inflammation, including increased C5a generation as MAC is activated (97), the glycosylation state of the antibody (98), or differential Fc receptor activation (99). Antibody to LPS has also been shown to inhibit alveolar phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa (see below). Any one of these mechanisms may be responsible for the association with worse lung function.

Finally, although cloaking antibodies are associated with worse disease in many bacterial infections, it is important to note that antibodies to LPS, LOS, or capsule are protective in many of the diseases discussed above and are core components of current vaccines or vaccines under development (100–104). These antibodies are protective through various mechanisms such as by preventing adhesion of the bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract (105). Despite this, vaccine development efforts should also include consideration of the possibility of these antibodies enhancing bacterial infections, as it may also explain previous cases where LPS-based vaccinations have led to worse clinical status in some patients (106, 107). Finally, it is worth remembering that the serum of many mouse strains is unable to kill various Gram-negative bacteria by complement-mediated lysis (108, 109); thus, the role of serum resistance may not be accounted for in many models.

VIRULENCE ENHANCEMENT BY ANTIBODY PROTEOLYSIS

To counteract host immune pathways, bacterial pathogens have evolved to express and secrete proteases that target antibodies, preventing normal immunoglobulin effector function (110–112). Conceivably, this targeted cleavage of antibodies by bacterial proteases may represent a distinct mechanism for exacerbating bacterial disease. In several examples, pathogenic bacteria that produce IgA proteases are predominately associated with colonization of mucosal surfaces (113, 114). The capability to evade these IgA-dominant mucosal sites provides a fitness advantage for these pathogens. As an example, in a study by Weiser et al. (17), the authors found specific antibody responses to the bacterium S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus) can enhance infection. This study found that a secreted bacterial protease cleaves IgA1 that has specificity to capsular polysaccharide (CPS). Rather than the widely accepted function of IgA1 inhibiting adherence to pharyngeal epithelial cells, the presence of the antibody instead significantly augmented adherence in vitro. The authors found that the IgA1 protease specifically cleaved antigen-bound CPS-specific IgA1. This specific cleavage resulted in localized “unmasking” of the capsule, allowing the not normally readily accessible ChoP surface ligand, a choline-containing molecule (phosphorylcholine), to interact with the receptor for platelet-activating factor (rPAF) on cells in the infected host, consequently allowing bacterial cell adherence. The authors considered that such an antibody-mediated mechanism would result in the ability of pneumococcus to persist on mucosal surfaces of the host respiratory tract.

A mechanism instead exploiting the hinge region for proteolysis has also been observed for immunoglobulin IgG. The extracellular secreted proteases glutamyl endopeptidase V8 (GluV8) of Staphylococcus aureus and immunoglobulin-degrading enzyme (IdeS) of Streptococcus pyogenes (115, 116) have been shown to cleave within the hinge region of IgG molecules (of the CH2 linker), disabling binding to host Fc receptors. Several other groups have reported that even a single cleavage in this region is able to abolish binding to Fc receptors (117). Interestingly, cystatin C, a host cysteine protease inhibitor, is “hijacked” and instead acts as cofactor for bacterial IdeS and accelerates IgG cleavage (118, 119). Mechanistically, the literature is not clear, but perhaps cleavage of the IgG immunoglobulin serves two functions in precluding bacterial clearance by not only impeding the regulation of a conducive immune response by Fc receptors binding but also masking epitopes to other components of the host immune system. A similar tactic to evade host immune responses by many pathogenic bacterial species is to express cell surface proteins (e.g., protein A of S. aureus and Eib proteins of E. coli) that bind antibodies outside the Fab region of IgG so that these antibodies are incorrectly orientated and therefore functionally impaired from eliciting an immune response (120, 121). Altogether, the presence of antibody in these scenarios would instead actively enhance protection of the bacteria.

From these discussed studies, it becomes clearer that the exploitation by proteolysis of immunoglobulin is a common strategy of pathogenic bacteria (Table 3). The evolution of such different protease family classes (serine-, cysteine-, and metalloproteases) shows the viability of such a strategy and how this may contribute in such distinct ways for a mechanism of bacterial ADE infection. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that some proteases have a broad substrate range (i.e., LasB of P. aeruginosa) (122, 123) or are only expressed in specific disease states (IgA1 protease of H. influenzae) (124, 125). Thus, further research that uses a combination of mutational and in vivo infection studies would be required to dissect the precise role these proteases play in contributing to antibody-mediated enhancement of bacterial infection.

TABLE 3.

Bacterial proteases specific for immunoglobulins

| Protease name | Pathogen | Immunoglobulin protease target | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IgA protease | Haemophilus influenzae type B | IgA1 | 124, 125 |

| IgA protease | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | IgA1 | 135, 138 |

| IgA protease | Neisseria meningitidis | IgA1 | 139, 140 |

| IgA protease | Streptococcus pneumoniae | IgA1 | 17, 114 |

| LasB (elastase, pseudolysin) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | IgG1 | 122, 123 |

| ZapA (mirabilysin) | Proteus mirabilis | IgG1/IgG2/IgA1 | 141–143 |

| Gluv8 (glutamyl endopeptidase I, SspA) | Staphylococcus aureus | IgG1 | 115, 144, 145 |

| IdeS (immunoglobulin-degrading enzyme of Streptococcus) | Streptococcus pneumoniae | IgG1 | 116, 119 |

| Dentilisin (PrtP, trepolisin) | Treponema denticola | IgG1 | 146 |

ANTIBODY-MEDIATED INCREASE IN ADHESION

A reported feature of some clinically relevant pathogens is the ability to shed or modulate their capsular polysaccharide (CPS) layer (126–128). The function of this dynamic process of capsule shedding or restructuring has been described for the evasion of host immune defenses, potentially providing insight to explain antibody-mediated enhancement of bacterial infection. Wang-Lin et al. (18) reported that a mechanism of ADE exists for A. baumannii infection in a mouse pneumonia model. The authors reported the development of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody and assessed its ability to induce protective immunity against clinical strain A. baumannii AB99. The designed IgG3 monoclonal antibody—8E3—was developed for specificity toward serotype K2 CPS of A. baumannii AB99. However, in vivo immunization resulted in AB99-infected mice with increased mortality accompanied by significant increases in bacterial loads in blood, lung, and spleen samples. The authors then identified that shed capsule components of AB99 bound with 8E3 formed soluble immune complexes and demonstrated in vitro adherence to human lung epithelial cells, thereby positing (i) these immune complexes at high concentrations acts as a “binding sink” for immune molecules, overall depressing the activity of phagocytic cells, or (ii) 8E3-A. baumannii complexes enhance infection through increased adherence to and invasion of host cells by interacting with Fc receptors. The authors of this study do acknowledge that intrinsic properties of the capsule and virulence factors could also contribute to the observed ADE of infection in mice. Thus, future studies could also investigate if and to what degree any specific chemistries of cell surface structures (i.e., CPS, LPS, or LOS) or virulence factors play a role in the overall context of antibody-mediated enhancement of bacterial infection.

ANTIBODY-MEDIATED INHIBITION OF PHAGOCYTOSIS

One of the functions of antibodies is to opsonize bacteria, allowing recognition by Fc receptors and leading to increased phagocytosis. Paradoxically, specific antibodies that inhibit phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa have been described. Serum from patients with CF were found to inhibit phagocytosis by both normal and CF alveolar macrophages, in contrast to NHS, which promoted phagocytosis (129, 130). IgG specific for P. aeruginosa LPS was found to correlate with phagocytic inhibition (131) and, when purified, was found to inhibit both the rate and absolute bacterial uptake by alveolar macrophages (132). Cats infected with O-antigen-expressing P. aeruginosa also developed strain-specific phagocytic-inhibitory serum over time (85). If these LPS antibodies are primarily IgG2 as previously found (23), it may be that as IgG2 has no or low affinity for many of the Fc receptors expressed by macrophages (133), the antibody-coated bacteria are masked from targeted killing. As Ig proteases have also been shown to prevent opsonophagocytosis, it may be that P. aeruginosa proteases such as LasB are also required for this mechanism to occur.

TREATMENT OF BACTERIAL ADE

In only a few reported cases of bacterial ADE has any targeted treatment of the specific antibody been attempted. “Cloaking antibodies” in P. aeruginosa infection have been shown to correlate with worse lung function (23). Two patients identified in the initial study with cloaking antibodies had severely impaired lung function, multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, and had exhausted all standard treatment options (71). Removal of the IgG antibody had been shown in vitro to restore bactericidal activity of the serum against these strains (23). Thus, the use of plasmapheresis as a novel treatment to remove cloaking antibody, restore normal immune killing, and ameliorate infection was proposed. Each patient was given plasmapheresis followed by intravenous pooled immunoglobulin (IVIg). After treatment, both patients were able to return home; their sputum was P. aeruginosa negative and a sustained decrease in the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein was observed. Cloaking antibody titers dropped significantly with plasmapheresis but increased over 90 days, such that these sera were unable to kill their cognate P. aeruginosa. Reemergence of inhibition correlated with the reappearance of P. aeruginosa in sputa, increased symptomatology, and poorer responses to subsequent antibiotic courses. This prompted a second round of plasmapheresis for one of the patients, resulting in a similar improvement in patient health.

In a more recent case, a similar treatment was again used where a patient with CF had developed P. aeruginosa infection post-lung transplant, which continued to spread despite aggressive incision and drainage and treatment with two different antibiotic cocktails (134). Posttreatment, the patient recovered, with no further infective complications and vastly improved allograft function. As all patient isolates displayed resistance to antibiotics used routinely for respiratory infections, this treatment offers an exciting and novel method to treat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.

CONCLUSION

Despite a focus on viral ADE in recent years, ADE has been shown for multiple bacterial infections in both animal models and human cohorts. The mechanisms underlying this enhancement are distinct from those found in viral diseases, ranging from mediating serum resistance, protecting against phagocytosis, and increasing bacterial virulence functions. These antibody-mediated mechanisms are found in a wide array of diseases and bacterial species, indicating that ADE of bacterial infection may be more prevalent than expected. As in viral ADE, whether the specific antibody is protective or deleterious depends on many elements, including the expression of various virulence factors of the bacteria, site of infection, and titer of the antibody. Continuing efforts to develop safe and effective vaccines for various bacterial infections should include awareness of the possibility of bacterial ADE in certain cases, which may even explain some vaccination failures in the past. Finally, treatment of bacterial ADE by removal of the cloaking antibody has been successfully demonstrated and may be a viable alternative treatment option for otherwise drug-resistant bacteria.

Biography

Timothy J. Wells

REFERENCES

- 1.Forthal DN. 2014. Functions of antibodies. Microbiol Spectr 2:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroeder HW, Jr, Cavacini L. 2010. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125:S41–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiu ML, Goulet DR, Teplyakov A, Gilliland GL. 2019. Antibody structure and function: the basis for engineering therapeutics. Antibodies (Basel) 8:55. doi: 10.3390/antib8040055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd D. 2005. Immunoglobulin. subclasses and functions, p 328–331. In Vohr H-W (ed), Encyclopedic reference of immunotoxicology. Springer, Berlin, Germany. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27806-0_766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowd KA, Pierson TC. 2011. Antibody-mediated neutralization of flaviviruses: a reductionist view. Virology 411:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halstead SB. 2014. Dengue antibody-dependent enhancement: knowns and unknowns. Microbiol Spectr 2:AID-0022-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0022-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haslwanter D, Blaas D, Heinz FX, Stiasny K. 2017. A novel mechanism of antibody-mediated enhancement of flavivirus infection. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006643. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochiai H, Kurokawa M, Kuroki Y, Niwayama S. 1990. Infection enhancement of influenza A H1 subtype viruses in macrophage-like P388D1 cells by cross-reactive antibodies. J Med Virol 30:258–265. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotoff R, Tamura M, Janus J, Thompson J, Wright P, Ennis FA. 1994. Primary influenza A virus infection induces cross-reactive antibodies that enhance uptake of virus into Fc receptor-bearing cells. J Infect Dis 169:200–203. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winarski KL, Tang J, Klenow L, Lee J, Coyle EM, Manischewitz J, Turner HL, Takeda K, Ward AB, Golding H, Khurana S. 2019. Antibody-dependent enhancement of influenza disease promoted by increase in hemagglutinin stem flexibility and virus fusion kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:15194–15199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821317116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvin AM, Fink K, Schmid MA, Cathcart A, Spreafico R, Havenar-Daughton C, Lanzavecchia A, Corti D, Virgin HW. 2020. A perspective on potential antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 584:353–363. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen J, Cheng Y, Ling R, Dai Y, Huang B, Huang W, Zhang S, Jiang Y. 2020. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus. Int J Infect Dis 100:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polack FP. 2007. Atypical measles and enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease (ERD) made simple. Pediatr Res 62:111–115. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3180686ce0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flanagan KL, Best E, Crawford NW, Giles M, Koirala A, Macartney K, Russell F, Teh BW, Wen SC. 2020. Progress and pitfalls in the quest for effective SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) vaccines. Front Immunol 11:579250. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.579250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham BS. 2020. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science 368:945–946. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeiffer R, Issaeff R. 1894. Uber die Specifishche der Bedeutung der Choleraimmunitat. Z Hyg Infektionskr 17:355–400. doi: 10.1007/BF02284479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiser JN, Bae D, Fasching C, Scamurra RW, Ratner AJ, Janoff EN. 2003. Antibody-enhanced pneumococcal adherence requires IgA1 protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:4215–4220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637469100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang-Lin SX, Olson R, Beanan JM, MacDonald U, Russo TA, Balthasar JP. 2019. Antibody dependent enhancement of Acinetobacter baumannii infection in a mouse pneumonia model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 368:475–489. doi: 10.1124/jpet.118.253617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulati S, Zheng B, Reed GW, Su X, Cox AD, St Michael F, Stupak J, Lewis LA, Ram S, Rice PA. 2013. Immunization against a saccharide epitope accelerates clearance of experimental gonococcal infection. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003559. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulati S, Mu X, Zheng B, Reed GW, Ram S, Rice PA. 2015. Antibody to reduction modifiable protein increases the bacterial burden and the duration of gonococcal infection in a mouse model. J Infect Dis 212:311–315. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moitra R, Beal DR, Belikoff BG, Remick DG. 2012. Presence of preexisting antibodies mediates survival in sepsis. Shock 37:56–62. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182356f3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plummer FA, Chubb H, Simonsen JN, Bosire M, Slaney L, Maclean I, Ndinya-Achola JO, Waiyaki P, Brunham RC. 1993. Antibody to Rmp (outer membrane protein 3) increases susceptibility to gonococcal infection. J Clin Invest 91:339–343. doi: 10.1172/JCI116190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells TJ, Whitters D, Sevastsyanovich YR, Heath JN, Pravin J, Goodall M, Browning DF, O'Shea MK, Cranston A, De Soyza A, Cunningham AF, MacLennan CA, Henderson IR, Stockley RA. 2014. Increased severity of respiratory infections associated with elevated anti-LPS IgG2 which inhibits serum bactericidal killing. J Exp Med 211:1893–1904. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunkelberger JR, Song WC. 2010. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res 20:34–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson SH, Ostenson CG, Tullus K, Brauner A. 1992. Serum resistance in Escherichia coli strains causing acute pyelonephritis and bacteraemia. APMIS 100:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1992.tb00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kugelberg E, Gollan B, Tang CM. 2008. Mechanisms in Neisseria meningitidis for resistance against complement-mediated killing. Vaccine 26 Suppl 8:I34–I39. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. 2008. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:132–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joiner K, Brown E, Hammer C, Warren K, Frank M. 1983. Studies on the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. III. C5b-9 deposits stably on rough and type 7 S. pneumoniae without causing bacterial killing. J Immunol 130:845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geoffroy MC, Floquet S, Metais A, Nassif X, Pelicic V. 2003. Large-scale analysis of the meningococcus genome by gene disruption: resistance to complement-mediated lysis. Genome Res 13:391–398. doi: 10.1101/gr.664303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buckles EL, Wang X, Lane MC, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Rasko DA, Mobley HL, Donnenberg MS. 2009. Role of the K2 capsule in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection and serum resistance. J Infect Dis 199:1689–1697. doi: 10.1086/598524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miajlovic H, Smith SG. 2014. Bacterial self-defence: how Escherichia coli evades serum killing. FEMS Microbiol Lett 354:1–9. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjorksten B, Bortolussi R, Gothefors L, Quie PG. 1976. Interaction of E. coli strains with human serum: lack of relationship to K1 antigen. J Pediatr 89:892–897. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stawski G, Nielsen L, Orskov F, Orskov I. 1990. Serum sensitivity of a diversity of Escherichia coli antigenic reference strains. Correlation with an LPS variation phenomenon. APMIS 98:828–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1990.tb05003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phan MD, Peters KM, Sarkar S, Lukowski SW, Allsopp LP, Gomes Moriel D, Achard ME, Totsika M, Marshall VM, Upton M, Beatson SA, Schembri MA. 2013. The serum resistome of a globally disseminated multidrug resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli clone. PLoS Genet 9:e1003834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hovingh ES, van den Broek B, Jongerius I. 2016. Hijacking complement regulatory proteins for bacterial immune evasion. Front Microbiol 7:2004. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chmouryguina I, Suvorov A, Ferrieri P, Cleary PP. 1996. Conservation of the C5a peptidase genes in group A and B streptococci. Infect Immun 64:2387–2390. doi: 10.1128/IAI.64.7.2387-2390.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neisser M, Wechsberg F. 1901. Ueber die wirkungsart bactericider sera. Munch Med Wochensch 48:697. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipstein. 1902. Die komplementablenkung bei baktericiden reagenzglasversuchen und ihre ursache. Centralb f Bakt Orig 31:460–468. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas L, Smith HW, Dingle JH. 1943. Investigations of meningococcal infection. II. Immunological aspects. J Clin Invest 22:361–373. doi: 10.1172/JCI101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffiss JM. 1975. Bactericidal activity of meningococcal antisera. Blocking by IgA of lytic antibody in human convalescent sera. J Immunol 114:1779–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiss JM, Bertram MA. 1977. Immunoepidemiology of meningococcal disease in military recruits. II. Blocking of serum bactericidal activity by circulating IgA early in the course of invasive disease. J Infect Dis 136:733–739. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvis GA, Griffiss JM. 1991. Human IgA1 blockade of IgG-initiated lysis of Neisseria meningitidis is a function of antigen-binding fragment binding to the polysaccharide capsule. J Immunol 147:1962–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayhty H. 1980. Comparison of passive hemagglutination, bactericidal activity, and radioimmunological methods in measuring antibody responses to Neisseria meningitidis group A capsular polysaccharide vaccine. J Clin Microbiol 12:256–263. doi: 10.1128/JCM.12.2.256-263.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amir J, Louie L, Granoff DM. 2005. Naturally-acquired immunity to Neisseria meningitidis group A. Vaccine 23:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selander B, Kayhty H, Wedege E, Holmstrom E, Truedsson L, Soderstrom C, Sjoholm AG. 2000. Vaccination responses to capsular polysaccharides of Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae type b in two C2-deficient sisters: alternative pathway-mediated bacterial killing and evidence for a novel type of blocking IgG. J Clin Immunol 20:138–149. doi: 10.1023/a:1006638631581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray TD, Lewis LA, Gulati S, Rice PA, Ram S. 2011. Novel blocking human IgG directed against the pentapeptide repeat motifs of Neisseria meningitidis Lip/H.8 and Laz lipoproteins. J Immunol 186:4881–4894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galili U, Rachmilewitz EA, Peleg A, Flechner I. 1984. A unique natural human IgG antibody with anti-alpha-galactosyl specificity. J Exp Med 160:1519–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.5.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamadeh RM, Estabrook MM, Zhou P, Jarvis GA, Griffiss JM. 1995. Anti-Gal binds to pili of Neisseria meningitidis: the immunoglobulin A isotype blocks complement-mediated killing. Infect Immun 63:4900–4906. doi: 10.1128/IAI.63.12.4900-4906.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galili U, Mandrell RE, Hamadeh RM, Shohet SB, Griffiss JM. 1988. Interaction between human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobulin G and bacteria of the human flora. Infect Immun 56:1730–1737. doi: 10.1128/IAI.56.7.1730-1737.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamadeh RM, Jarvis GA, Galili U, Mandrell RE, Zhou P, Griffiss JM. 1992. Human natural anti-Gal IgG regulates alternative complement pathway activation on bacterial surfaces. J Clin Invest 89:1223–1235. doi: 10.1172/JCI115706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schoolnik GK, Ochs HD, Buchanan TM. 1979. Immunoglobulin class responsible for gonococcal bactericidal activity of normal human sera. J Immunol 122:1771–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tramont EC, Sadoff JC, Wilson C. 1977. Variability of the lytic susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to human sera. J Immunol 118:1843–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rice PA, Goldenberg DL. 1981. Clinical manifestations of disseminated infection caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae are linked to differences in bactericidal reactivity of infecting strains. Ann Intern Med 95:175–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-2-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rice PA, Kasper DL. 1977. Characterization of gonococcal antigens responsible for induction of bactericidal antibody in disseminated infection. J Clin Invest 60:1149–1158. doi: 10.1172/JCI108867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooks GF, Israel KS, Petersen BH. 1976. Bactericidal and opsonic activity against Neisseria gonorrhoeae in sera from patients with disseminated gonococcal infection. J Infect Dis 134:450–462. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCutchan JA, Katzenstein D, Norquist D, Chikami G, Wunderlich A, Braude AI. 1978. Role of blocking antibody in disseminated gonococcal infection. J Immunol 121:1884–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rice PA, Kasper DL. 1982. Characterization of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae that disseminate. Roles of blocking antibody and gonococcal outer membrane proteins. J Clin Invest 70:157–167. doi: 10.1172/jci110589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joiner KA, Scales R, Warren KA, Frank MM, Rice PA. 1985. Mechanism of action of blocking immunoglobulin G for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Invest 76:1765–1772. doi: 10.1172/JCI112167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice PA, McCormack WM, Kasper DL. 1980. Natural serum bactericidal activity against Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from disseminated, locally invasive, and uncomplicated disease. J Immunol 124:2105–2109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Apicella MA, Westerink MA, Morse SA, Schneider H, Rice PA, Griffiss JM. 1986. Bactericidal antibody response of normal human serum to the lipooligosaccharide of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Infect Dis 153:520–526. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glynn AA, Ward ME. 1970. Nature and heterogeneity of the antigens of Neisseria gonorrhoeae involved in the serum bactericidal reaction. Infect Immun 2:162–168. doi: 10.1128/IAI.2.2.162-168.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blake MS, Wetzler LM, Gotschlich EC, Rice PA. 1989. Protein III: structure, function, and genetics. Clin Microbiol Rev 2 Suppl:S60–S63. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.suppl.s60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rice PA. 1989. Molecular basis for serum resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2 Suppl:S112–S117. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.suppl.s112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lytton EJ, Blake MS. 1986. Isolation and partial characterization of the reduction-modifiable protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Exp Med 164:1749–1759. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.5.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rice PA, Vayo HE, Tam MR, Blake MS. 1986. Immunoglobulin G antibodies directed against protein III block killing of serum-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae by immune serum. J Exp Med 164:1735–1748. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.5.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Virji M, Heckels JE. 1988. Nonbactericidal antibodies against Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evaluation of their blocking effect on bactericidal antibodies directed against outer membrane antigens. J Gen Microbiol 134:2703–2711. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-10-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li G, Xie R, Zhu X, Mao Y, Liu S, Jiao H, Yan H, Xiong K, Ji M. 2014. Antibodies with higher bactericidal activity induced by a Neisseria gonorrhoeae Rmp deletion mutant strain. PLoS One 9:e90525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Munkley A, Tinsley CR, Virji M, Heckels JE. 1991. Blocking of bactericidal killing of Neisseria meningitidis by antibodies directed against class 4 outer membrane protein. Microb Pathog 11:447–452. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosenqvist E, Musacchio A, Aase A, Hoiby EA, Namork E, Kolberg J, Wedege E, Delvig A, Dalseg R, Michaelsen TE, Tommassen J. 1999. Functional activities and epitope specificity of human and murine antibodies against the class 4 outer membrane protein (Rmp) of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun 67:1267–1276. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.3.1267-1276.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Corbeil LB, Blau K, Inzana TJ, Nielsen KH, Jacobson RH, Corbeil RR, Winter AJ. 1988. Killing of Brucella abortus by bovine serum. Infect Immun 56:3251–3261. doi: 10.1128/IAI.56.12.3251-3261.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wells TJ, Davison J, Sheehan E, Kanagasundaram S, Spickett G, MacLennan CA, Stockley RA, Cunningham AF, Henderson IR, De Soyza A. 2017. The use of plasmapheresis in patients with bronchiectasis with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and inhibitory antibodies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195:955–958. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0599LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huddleson IF, Wood EE, Cressman AR, Bennett GR. 1945. The bactericidal action of bovine blood for Brucella and its possible significance. J Bacteriol 50:261–277. doi: 10.1128/JB.50.3.261-277.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huddleson IF. 1947. The immunization of guinea pigs with mucoid phases Brucella. Am J Vet Res 8:374–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Joos RW, Hall WH. 1968. Bactericidal action of fresh rabbit blood against Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol 96:881–885. doi: 10.1128/JB.96.4.881-885.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hall WH, Manion RE, Zinneman HH. 1971. Blocking serum lysis of Brucella abortus by hyperimmune rabbit immunoglobulin A. J Immunol 107:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoffmann EM, Houle JJ. 1995. Contradictory roles for antibody and complement in the interaction of Brucella abortus with its host. Crit Rev Microbiol 21:153–163. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waisbren BA, Brown I. 1966. A factor in the serum of patients with persisting infection that inhibits the bactericidal activity of normal serum against the organism that is causing the infection. J Immunol 97:431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gower PE, Taylor PW, Koutsaimanis KG, Roberts AP. 1972. Serum bactericidal activity in patients with upper and lower urinary tract infections. Clin Sci 43:13–22. doi: 10.1042/cs0430013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taylor PW. 1971. An antibactericidal factor in the serum of some patients with infections of the upper urinary tract. Clin Sci 41:5P. doi: 10.1042/cs041005p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taylor PW. 1972. An antibactericidal factor in the serum of two patients with infections of the upper urinary tract. Clin Sci 43:23–30. doi: 10.1042/cs0430023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor PW. 1972. Isolation and characterization of a serum antibactericidal factor. Clin Sci 43:705–708. doi: 10.1042/cs0430705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coggon CF, Jiang A, Goh KGK, Henderson IR, Schembri MA, Wells TJ. 2018. A novel method of serum resistance by Escherichia coli that causes urosepsis. mBio 9:e00920-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00920-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guttman RM, Waisbren BA. 1975. Bacterial blocking activity of specific IgG in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Clin Exp Immunol 19:121–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thomassen MJ, Demko CA. 1981. Serum bactericidal effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun 33:512–518. doi: 10.1128/IAI.33.2.512-518.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Winnie GB, Klinger JD, Sherman JM, Thomassen MJ. 1982. Induction of phagocytic inhibitory activity in cats with chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection. Infect Immun 38:1088–1093. doi: 10.1128/IAI.38.3.1088-1093.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adler FL. 1953. Studies on the bactericidal reaction. II. Inhibition by antibody, and antibody requirements of the reaction. J Immunol 70:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.MacLennan CA, Gilchrist JJ, Gordon MA, Cunningham AF, Cobbold M, Goodall M, Kingsley RA, van Oosterhout JJ, Msefula CL, Mandala WL, Leyton DL, Marshall JL, Gondwe EN, Bobat S, Lopez-Macias C, Doffinger R, Henderson IR, Zijlstra EE, Dougan G, Drayson MT, MacLennan IC, Molyneux ME. 2010. Dysregulated humoral immunity to nontyphoidal Salmonella in HIV-infected African adults. Science 328:508–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1180346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trebicka E, Jacob S, Pirzai W, Hurley BP, Cherayil BJ. 2013. Role of antilipopolysaccharide antibodies in serum bactericidal activity against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in healthy adults and children in the United States. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20:1491–1498. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00289-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goh YS, Necchi F, O’Shaughnessy CM, Micoli F, Gavini M, Young SP, Msefula CL, Gondwe EN, Mandala WL, Gordon MA, Saul AJ, MacLennan CA. 2016. Bactericidal immunity to Salmonella in Africans and mechanisms causing its failure in HIV infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ward CK, Inzana TJ. 1994. Resistance of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae to bactericidal antibody and complement is mediated by capsular polysaccharide and blocking antibody specific for lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 153:2110–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.King PT, Sharma R. 2015. The lung immune response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (lung immunity to NTHi). J Immunol Res 2015:706376. doi: 10.1155/2015/706376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Musher DM, Goree A, Baughn RE, Birdsall HH. 1984. Immunoglobulin A from bronchopulmonary secretions blocks bactericidal and opsonizing effects of antibody to nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun 45:36–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.45.1.36-40.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Griffiss JM, Goroff DK. 1983. IgA blocks IgM and IgG-initiated immune lysis by separate molecular mechanisms. J Immunol 130:2882–2885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang JS, An SJ, Jang MS, Song M, Han SH. 2019. IgM specific to lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae is a surrogate antibody isotype responsible for serum vibriocidal activity. PLoS One 14:e0213507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Whitters D, Stockley R. 2012. Immunity and bacterial colonisation in bronchiectasis. Thorax 67:1006–1013. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chmiel JF, Berger M, Konstan MW. 2002. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of CF lung disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 23:5–27. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:23:1:005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hair PS, Sass LA, Vazifedan T, Shah TA, Krishna NK, Cunnion KM. 2017. Complement effectors, C5a and C3a, in cystic fibrosis lung fluid correlate with disease severity. PLoS One 12:e0173257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Alter G, Ottenhoff THM, Joosten SA. 2018. Antibody glycosylation in inflammation, disease and vaccination. Semin Immunol 39:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bournazos S, Gupta A, Ravetch JV. 2020. The role of IgG Fc receptors in antibody-dependent enhancement. Nat Rev Immunol 20:633–643. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00410-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dorneles EM, Sriranganathan N, Lage AP. 2015. Recent advances in Brucella abortus vaccines. Vet Res 46:76. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Provenzano D, Kovac P, Wade WF. 2006. The ABCs (antibody, B cells, and carbohydrate epitopes) of cholera immunity: considerations for an improved vaccine. Microbiol Immunol 50:899–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gulati S, Shaughnessy J, Ram S, Rice PA. 2019. Targeting lipooligosaccharide (LOS) for a gonococcal vaccine. Front Immunol 10:321. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pier GB. 2003. Promises and pitfalls of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide as a vaccine antigen. Carbohydr Res 338:2549–2556. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(03)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Priebe GP, Goldberg JB. 2014. Vaccines for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a long and winding road. Expert Rev Vaccines 13:507–519. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.890053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mukhopadhyay S, Nandi B, Ghose AC. 2000. Antibodies (IgG) to lipopolysaccharide of Vibrio cholerae O1 mediate protection through inhibition of intestinal adherence and colonisation in a mouse model. FEMS Microbiol Lett 185:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Doring G, Pier GB. 2008. Vaccines and immunotherapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Vaccine 26:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cryz SJ, Jr, Sadoff JC, Cross AS, Furer E. 1989. Safety and immunogenicity of a polyvalent Pseudomonas aeruginosa O-polysaccharide-toxin A vaccine in humans. Antibiot Chemother (1971) 42:177–183. doi: 10.1159/000417618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Muschel LH, Muto T. 1956. Bactericidal reaction of mouse serum. Science 123:62–64. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3185.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Siggins MK, Cunningham AF, Marshall JL, Chamberlain JL, Henderson IR, MacLennan CA. 2011. Absent bactericidal activity of mouse serum against invasive African nontyphoidal Salmonella results from impaired complement function but not a lack of antibody. J Immunol 186:2365–2371. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Potempa J, Pike RN. 2009. Corruption of innate immunity by bacterial proteases. J Innate Immun 1:70–87. doi: 10.1159/000181144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brezski RJ, Jordan RE. 2010. Cleavage of IgGs by proteases associated with invasive diseases: an evasion tactic against host immunity? MAbs 2:212–220. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Woof JM. 2016. Immunoglobulins and their receptors, and subversion of their protective roles by bacterial pathogens. Biochem Soc Trans 44:1651–1658. doi: 10.1042/BST20160246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kilian M, Reinholdt J, Lomholt H, Poulsen K, Frandsen EV. 1996. Biological significance of IgA1 proteases in bacterial colonization and pathogenesis: critical evaluation of experimental evidence. APMIS 104:321–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1996.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Roche AM, Richard AL, Rahkola JT, Janoff EN, Weiser JN. 2015. Antibody blocks acquisition of bacterial colonization through agglutination. Mucosal Immunol 8:176–185. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dubin G. 2002. Extracellular proteases of Staphylococcus spp. Biol Chem 383:1075–1086. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.von Pawel-Rammingen U, Johansson BP, Björck L. 2002. IdeS, a novel streptococcal cysteine proteinase with unique specificity for immunoglobulin G. EMBO J 21:1607–1615. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Brezski RJ, Vafa O, Petrone D, Tam SH, Powers G, Ryan MH, Luongo JL, Oberholtzer A, Knight DM, Jordan RE. 2009. Tumor-associated and microbial proteases compromise host IgG effector functions by a single cleavage proximal to the hinge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17864–17869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904174106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Vincents B, Vindebro R, Abrahamson M, von Pawel-Rammingen U. 2008. The human protease inhibitor cystatin C is an activating cofactor for the streptococcal cysteine protease IdeS. Chem Biol 15:960–968. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.von Pawel-Rammingen U. 2012. Streptococcal IdeS and its impact on immune response and inflammation. J Innate Immun 4:132–140. doi: 10.1159/000332940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Forsgren M. 1966. The antigen composition of ECHO type 6 virus studied by immunodiffusion and immunoelectrophoresis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 66:262–263. doi: 10.1111/apm.1966.66.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Leo JC, Goldman A. 2009. The immunoglobulin-binding Eib proteins from Escherichia coli are receptors for IgG Fc. Mol Immunol 46:1860–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bainbridge T, Fick RB, Jr. 1989. Functional importance of cystic fibrosis immunoglobulin G fragments generated by Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase. J Lab Clin Med 114:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Döring G, Goldstein W, Röll A, Schiøtz PO, Høiby N, Botzenhart K. 1985. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzymes in lung infections of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 49:557–562. doi: 10.1128/IAI.49.3.557-562.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Murphy TF, Kirkham C, Jones MM, Sethi S, Kong Y, Pettigrew MM. 2015. Expression of IgA proteases by Haemophilus influenzae in the respiratory tract of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis 212:1798–1805. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]