The Gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes survives in environments ranging from the soil to the cytosol of infected host cells. Key to L. monocytogenes intracellular survival is the activation of PrfA, a transcriptional regulator that is required for the expression of multiple bacterial virulence factors.

KEYWORDS: CbpA, Listeria monocytogenes, PrfA, YgbB, oxidative stress, peroxide

ABSTRACT

The Gram-positive bacterium Listeria monocytogenes survives in environments ranging from the soil to the cytosol of infected host cells. Key to L. monocytogenes intracellular survival is the activation of PrfA, a transcriptional regulator that is required for the expression of multiple bacterial virulence factors. Mutations that constitutively activate prfA (prfA* mutations) result in high-level expression of multiple bacterial virulence factors as well as the physiological adaptation of L. monocytogenes for optimal replication within host cells. Here, we demonstrate that L. monocytogenes prfA* mutants exhibit significantly enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in comparison to that of wild-type strains. Transposon mutagenesis of L. monocytogenes prfA* strains resulted in the identification of three novel gene targets required for full oxidative stress resistance only in the context of PrfA activation. One gene, lmo0779, predicted to encode an uncharacterized protein, and two additional genes known as cbpA and ygbB, encoding a cyclic di-AMP binding protein and a 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase, respectively, contribute to the enhanced oxidative stress resistance of prfA* strains while exhibiting no significant contribution in wild-type L. monocytogenes. Transposon inactivation of cbpA and lmo0779 in a prfA* background led to reduced virulence in the liver of infected mice. These results indicate that L. monocytogenes calls upon specific bacterial factors for stress resistance in the context of PrfA activation and thus under conditions favorable for bacterial replication within infected mammalian cells.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium that is widespread in the outside environment as well as in habitats where survival depends on the organism’s ability to mitigate a variety of stresses, including fluctuations in temperature, salinity, and pH (1, 2). One important and medically relevant habitat occupied by L. monocytogenes is the cytosol of infected mammalian cells, where intracellular replication of bacteria occurs within susceptible hosts and can result in devastating disease (3). L. monocytogenes is primarily a foodborne pathogen, and to reach its intracellular replication niche the bacterium must survive passage through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and translocation across the intestinal barrier before reaching additional tissues for replication (4, 5). As a result, L. monocytogenes encounters numerous stress conditions that span large variations in pH and osmolarity as well as bacterial exposure to degradative enzymes (such as lysozyme) and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Importantly, a number of bacterial gene products associated with stress resistance in L. monocytogenes have been identified and linked to successful survival in the environment and to intragastric survival; however, less is known regarding how the bacterium manages stresses encountered during systemic infection (2, 6).

Oxidative stress is often considered to represent a significant host defense against pathogen invasion of host cells and tissues (7, 8). Professional phagocytes such as macrophages limit pathogen viability via the oxidative burst delivered following the assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex on the phagosome; however, L. monocytogenes has been reported to be capable of antagonizing complex assembly (9). In addition to oxidative stress encountered during host infection, Listeria, like all aerobes, generates its own sources of oxidative stress via aerobic metabolism and has evolved mechanisms to protect itself. Superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are generated during oxidative respiration and L. monocytogenes employs superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase, respectively, to neutralize these reactive species. Both O2− and H2O2 can react further with free heavy metals to form the highly potent hydroxyl (OH−) radical, capable of reacting with most macromolecules (10). Other gene products reported to contribute to L. monocytogenes oxidative stress resistance include the metalloregulatory protein PerR and 2-Cys peroxiredoxin (Prx) (11–13).

Recent evidence suggests that L. monocytogenes uses redox-responsive transcription factors to coordinate virulence factor expression within the host and that the redox environment of bacteria within host cells differs significantly from the environment for bacteria grown in broth culture (14, 15). The transition of L. monocytogenes from life as a saprophyte to life within host cells is primarily mediated by the virulence regulator PrfA, which activates the expression of core virulence factors required for growth in response to increased glutathione levels within the host cell (14). PrfA coordinates virulence factor gene expression while also modulating L. monocytogenes physiology to adapt bacteria to conditions favorable for intracellular replication (16–19). PrfA activity is maintained at a low basal level in the outside environment, but the protein becomes highly activated upon cytosol access (14, 16–22). Ripio et al. (23) identified a mutation within prfA (prfA*) that resulted in the constitutive activation of PrfA and high-level expression of PrfA-regulated genes in broth-grown cultures; since this original description, a number of other amino acid substitutions have been identified that confer differing levels of PrfA activation (21, 24–28). The isolation of these various prfA* mutant strains has enabled detailed characterization of the effects of PrfA activation on both patterns of L. monocytogenes gene expression and bacterial physiology (16, 17, 29, 30). The constitutive activation of PrfA increases the susceptibility of L. monocytogenes to selected forms of stress, such as high salinity and low pH, while simultaneously optimizing growth on host-relevant carbon sources (16, 31). As a result of these physiological changes, prfA* strains exhibit reduced fitness in comparison to that of wild-type bacteria in broth culture but are hypervirulent and have a competitive advantage over wild-type bacteria in mouse models of infection (16, 32).

Here, we demonstrate that L. monocytogenes prfA* strains are significantly more resistant to oxidative stress than wild-type strains, a phenotype that may contribute to their competitive advantage within the infected host. The increased resistance to oxidative stress appears to be due at least in part to gene products that uniquely contribute to resistance during PrfA activation, with little to no contribution detected in the absence of PrfA activation. Our results suggest that L. monocytogenes relies on multiple mechanisms for stress resistance in a manner dependent on environmental status, with subsets of gene products contributing to aspects of stress resistance specific to conditions of PrfA activation.

RESULTS

Activation of PrfA via prfA* confers increased resistance of L. monocytogenes to oxidative stress.

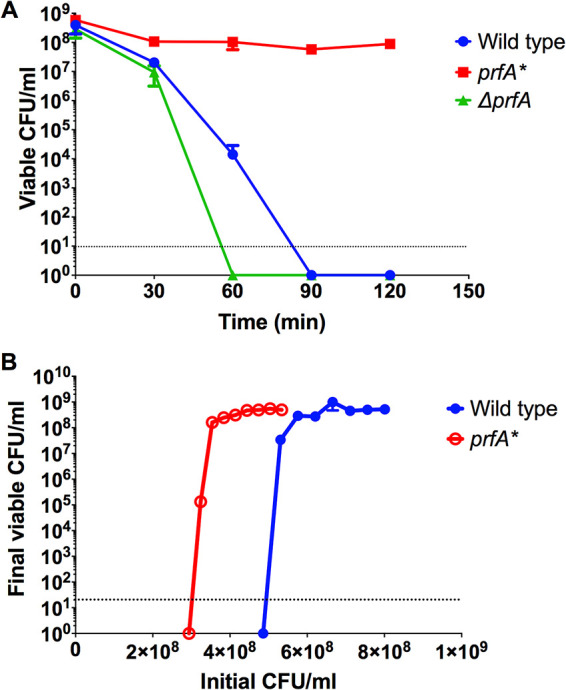

During the course of host infection, L. monocytogenes is anticipated to encounter multiple exposures to oxidative stress (11, 15, 33). Given that activation of the central virulence regulator PrfA has been shown to increase bacterial fitness during host infection (16), we sought to determine whether constitutively activated prfA* strains exhibited any changes in resistance to oxidative stress in comparison to wild-type bacteria. An assay designed to assess killing by peroxide exposure in vitro was used to compare the oxidative stress resistance of wild-type, prfA*, and ΔprfA strains. Strains were incubated in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium containing 110 mM H2O2, and aliquots were removed at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min to determine bacterial viability by plating for CFU on LB agar. L. monocytogenes prfA* strains were significantly more resistant to H2O2 exposure than wild-type or ΔprfA strains, with up to 90% of bacteria remaining viable after 2 h of exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no viable CFU were observed following 90 min of peroxide exposure for wild-type cells, and the ΔprfA mutant was even more susceptible, with no viable colonies recovered after 1 h. Resistance to peroxide exposure was influenced by culture density, such that wild-type 10403S required a nearly 2-fold-greater cell density in the initial inoculum to withstand peroxide exposure than did the prfA* mutant (Fig. 1B). Culture density is relevant given that molecules and/or enzymes that scavenge or neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) (such as secreted catalase) would be anticipated to confer increased resistance to a population of cells at a high cell density. It is therefore of interest that prfA* strains remain resistant to ROS at cell densities that are approximately half of those observed for wild-type strains. Despite differential susceptibilities to peroxide exposure, wild-type and prfA* strains exhibited no difference in catalase activity (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). These data indicate that activation of PrfA results in an enhancement of the ability of L. monocytogenes to survive exposure to oxidative stress.

FIG 1.

A prfA* strain is more resistant to H2O2-mediated killing in vitro. Strains were grown to mid-log phase and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2. A total of 890 μl of culture was transferred to a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and combined with 110 μl of freshly diluted 1 M H2O2 solution in BHI. Tubes were incubated statically for 2 h at room temperature and plated on LB agar for viable bacteria at 30-min intervals (A) or after 2 h (endpoint assays) (B). Data are representative of those from four independent experiments.

Identification of transposon insertion mutations that reduce the resistance of L. monocytogenes prfA* strains to oxidative stress in vitro.

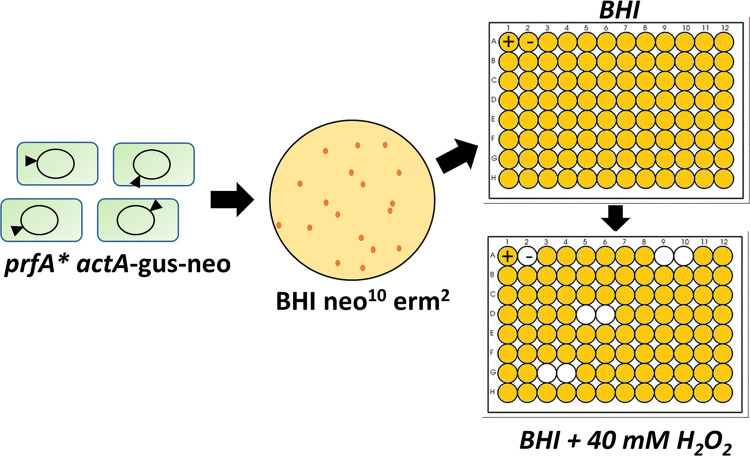

The ability of prfA* strains to better withstand exposure to H2O2 suggested that PrfA activation influenced the expression of gene products contributing to oxidative stress resistance. We therefore sought to identify gene products that contribute to bacterial survival following H2O2 exposure by screening for transposon insertions mutants with reduced oxidative stress resistance in the prfA* background (Fig. 2). Mariner transposon random insertion libraries were constructed in L. monocytogenes prfA* strains containing transcriptional fusions of gus and neo to the PrfA-dependent actA gene (actA-gus-neo) (24). The actA-gus-neo fusion allows selection of PrfA* activity based on increased expression of gus-encoded β-glucuronidase activity and neo-encoded neomycin resistance. Individual transposon insertion mutants were isolated on BHI plates containing 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin to select for the transposon insertion and 10 μg ml−1 of neomycin to select for the retention of PrfA* activity. Isolated mutants were then inoculated into BHI medium with 10 μg ml−1 of neomycin in 96-well plates and grown statically at 37°C overnight, then subcultured into BHI and neomycin and 40 mM H2O2, and grown at 37°C for 48 h (the reduced concentration of H2O2 for the screen permitted growth of the prfA* mutants but not the wild-type L. monocytogenes strains). Transposon insertion mutants that failed to replicate in the presence of H2O2 were selected and retested to confirm increased sensitivity to H2O2 while maintaining PrfA* activity as assessed by neomycin resistance and blue colony color on beta-glucuronidase indicator plates.

FIG 2.

Screening of L. monocytogenes prfA* transposon insertion mutant libraries for increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide. Two independently generated prfA* transposon libraries were generated and randomly screened for increased sensitivity to 40 mM H2O2 in BHI medium. Individual mutants were picked into 200 μl of BHI medium in 96-well plates and grown at 37°C statically overnight. The following day, cell OD600s were recorded and 10 μl of each culture was transferred in duplicate to new 96-well plates containing 190 μl of 40 mM H2O2 in BHI. These plates were grown statically at 37°C for 48 h, and mutants that failed to grow were rescreened for susceptibility. Transposon insertion sites were determined with inverse PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Twenty-five mutants with increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide in vitro were identified after screening of more than 7,500 transposon insertion mutant colonies. After the elimination of candidate mutants that exhibited growth defects in BHI broth with no H2O2 selection, three mutants were identified for further characterization and transposon mapping.

Identification of three genes associated with prfA*-dependent resistance to oxidative stress.

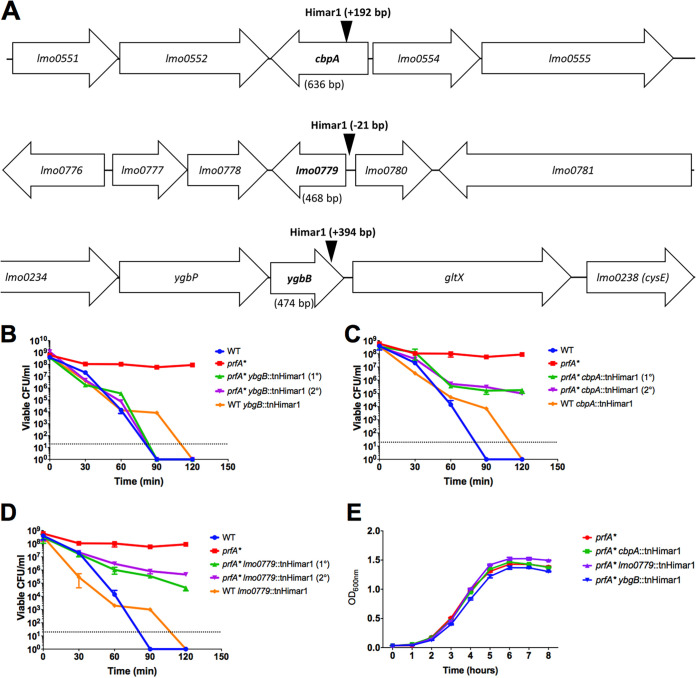

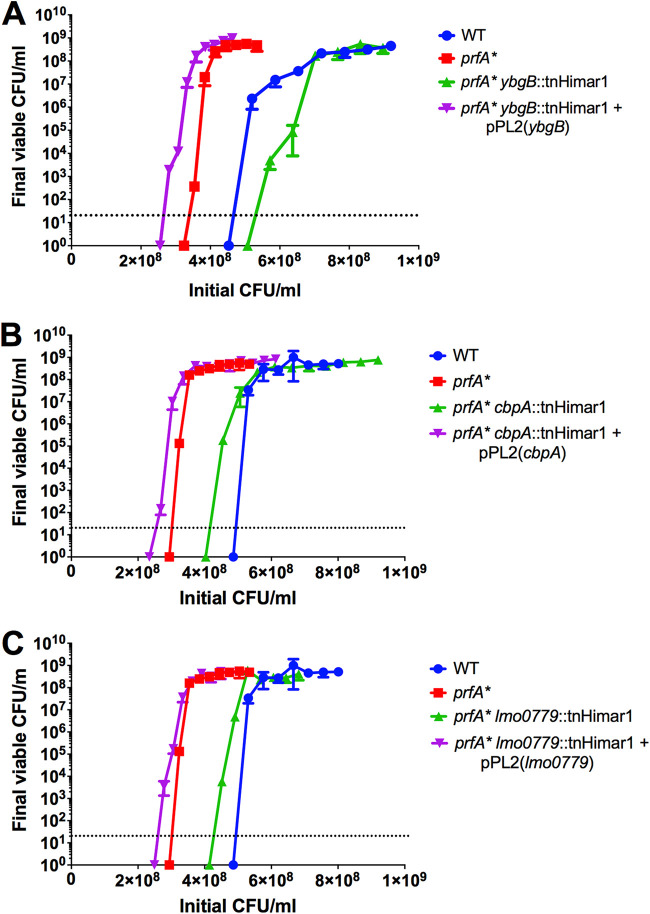

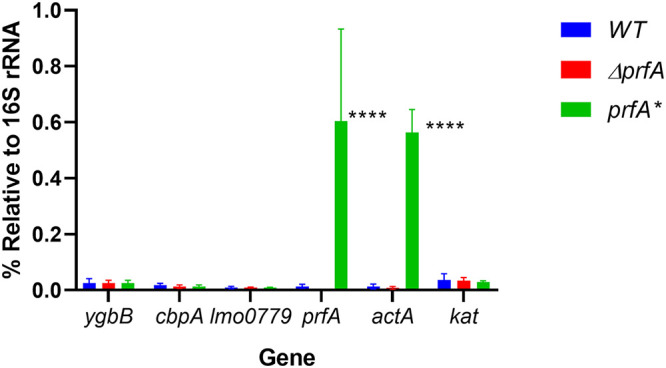

Transposon insertion sites were identified within the three individual mutants (Fig. 3A). Two mutants contained insertions within predicted open reading frames: LMRG_00235 (or lmo0553, using EGDe notation) and LMRG_02671 (lmo0236), and one in the immediate upstream region and predicted promoter region shared by LMRG_00467 (lmo0779) and LMRG_00468 (lmo0780) (Fig. 3A). lmo0236, also known as ygbB or ispF, encodes the enzyme 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclopyrophosphate (MEC or MEcPP) synthase, part of the alternative 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway for isoprenoid synthesis in bacteria (34). The MEP pathway has been associated with L. monocytogenes bile resistance (35), and loss of some pathway enzymes has been reported to reduce bacterial virulence in a mouse model of systemic infection (34, 36). The functions of the lmo0779/lmo0780 predicted gene products are not known; however, the lmo0553 gene product, also known as CbpA, has been identified as a binding receptor for the signaling molecule cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP), associated with L. monocytogenes metabolism and cell wall synthesis (37, 38). CbpA contains a cystathionine-β-synthase domain which binds c-di-AMP and an ACT small-molecule binding domain of unknown specificity (37). The function of this protein in vivo remains unclear. Structural predictions using the Phyre2 protein fold prediction server (39) predicted that the lmo0779 gene product is membrane bound, with potential nitrite/sulfite reductase activity in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain, and that the lmo0780 gene product may have DNA binding activity. All three transposon insertion mutants demonstrated a marked increase in sensitivity to H2O2 in the context of prfA* (Fig. 3B to D) while exhibiting similar patterns of growth in BHI medium (Fig. 3E) and no significant change in catalase activity (Fig. S1B). The phenotype of each individual transposon insertion was confirmed following transduction into a clean prfA* actA-gus-neo genetic background. In addition, to assess the insertion mutant phenotypes in the absence of PrfA activation, each mutant was also transduced into the 10403S parent strain. All of the transposon insertions were found to recapitulate the original H2O2-sensitive phenotype when introduced back into prfA* (Fig. 4). Interestingly, none of the transposon insertions increased wild-type sensitivity to H2O2, indicating that the enhanced sensitivity to oxidative stress was observable only in the context of PrfA activation. Complementation of mutant phenotypes was achieved via the introduction of the wild-type copy of each gene (lmo0779 for the promoter insertion), confirming the role of each in enhancing prfA* sensitivity to oxidative stress (Fig. 4). Interestingly, an assessment of cbpA, lmo0779, and ygbB transcript levels indicates that the gene products are not subject to PrfA regulation, nor is the gene encoding catalase (kat) (Fig. 5).

FIG 3.

Phage transduction to introduce transposon insertions into clean genetic backgrounds and confirm mutant phenotypes. (A) Location of each transposon insertion. Transposon insertions in cbpA (B), lmo0779 (C), and ygbB (D) were introduced into both 10403S and prfA* background strains as described in Materials and Methods. Strains were tested for peroxide sensitivity by incubation in BHI containing 110 mM H2O2 over 2 h. Viable CFU were enumerated at the indicated time points by plating on BHI agar. Standard growth curves in BHI at 37°C with shaking were performed (E). The data are representative of those from three independent experiments.

FIG 4.

Gene complementation restores oxidative stress resistance to transposon insertion mutants in vitro. Transduced transposon mutants were complemented in single copy as described in Materials and Methods. The transposon insertion mutants and the complemented strains were incubated statically at room temperature for 2 h and viable CFU were enumerated via plating on LB agar. Data are representative of those from three independent experiments.

FIG 5.

PrfA activation does not alter expression of candidate peroxide resistance genes or catalase. prfA*, ΔprfA, and wild-type strains were grown to mid-log phase and RNA was extracted. qRT-PCR was performed using primers listed in Table 1 to determine the transcript levels of cbpA, lmo0779, ygbB, kat, prfA, and PrfA-regulated gene actA relative to the 16S rRNA. ****, P < 0.0001 (two-factor ANOVA with the Tukey MCT). Data are representative of those from three independent experiments.

Loss of peroxide resistance reduces L. monocytogenes prfA* virulence in mice.

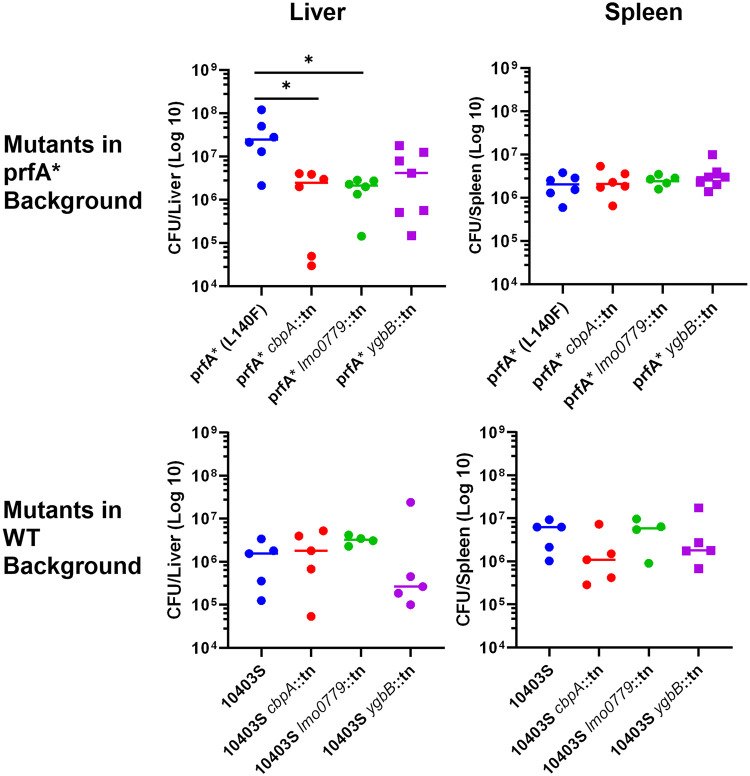

Resistance of L. monocytogenes to oxidative stress is predicted to contribute to bacterial viability during host infection (11, 15, 33, 40, 41). We have previously demonstrated that prfA* strains are hypervirulent in mouse models of infection (16); therefore, we sought to determine how the transposon insertions that increase the sensitivity of prfA* strains to oxidative stress might potentially influence bacterial virulence. Female 6- to 8-week-old Swiss Webster mice were infected via tail vein injection with either prfA* or the transposon insertion mutants in the prfA* background. Virulence in vivo was assessed by the measurement of bacterial burdens in target organs at 72 h postinfection (Fig. 6, top row). All strains exhibited comparable splenic burdens at this time point. In contrast, strains containing the transposon insertion within cbpA or lmo0779 exhibited significantly lower bacterial burdens within the liver than did the prfA* strain, with an approximately 10-fold drop in median CFU per organ. The strain containing an insertion in ygbB showed a similar trend, but the reduction in bacterial numbers was not statistically significant.

FIG 6.

Loss of peroxide resistance impacts virulence in PrfA* strains but not wild-type strains. (A) Six- to-8-week-old female Swiss Webster mice were infected via tail vein injection with 1 × 104 CFU of either prfA* or each prfA* transposon insertion mutant as indicated. Burdens were assessed 72 h postinfection. *, P < 0.05 Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s MCT. (B) Six- to-8-week-old female Swiss Webster mice were infected via tail vein injection with 1 × 104 CFU of either 10403S or each 10403S transposon insertion mutant as indicated. Burdens were assessed 72 h postinfection. Kruskal-Wallis test identified no significant differences. Data are representative of those from two independent experiments.

The defects in virulence observed for strains containing transposon insertions within cbpA and lmo0779 could be linked to the reduced resistance of prfA* strains containing these mutations to oxidative stress or could play an independent role in L. monocytogenes virulence regardless of the prfA mutation. We therefore examined the virulence of strains containing transposon insertions in cbpA, lmo0779, or ygbB in the context of the wild-type prfA allele (Fig. 6, bottom row). In contrast to findings in the prfA* strains, the disruption of these genes in a wild-type background had no significant effect on bacterial burdens in either the spleen or the liver in comparison to wild-type L. monocytogenes. The loss of cbpA and lmo0779 therefore appeared to reduce the virulence of prfA* strains in the context of liver infection while having little to no impact of bacterial colonization of prfA* mutants within the spleen or within either organ in the context of the wild-type prfA allele. The loss of cbpA, lmo0779, and/or ygbB can therefore dramatically reduce the enhanced oxidative resistance of prfA* strains without a substantial impact on the virulence of wild-type strains during mouse infection.

DISCUSSION

The activation of the L. monocytogenes virulence regulator PrfA is central to the ability of this bacterium to transition from a saprophyte into an intracellular pathogen within mammalian hosts (1, 21). PrfA is required for the expression of multiple gene products that promote bacterial invasion of host cells, replication within the cytosol, and spread to adjacent cells during infection (19). The characterization of constitutively activated prfA* mutants has revealed the scope and breadth of this regulator’s influence on virulence factor expression, bacterial metabolism, and adaptation to periods of nutrient starvation (16, 17, 23–25, 27, 28, 30, 32, 42). Here, we demonstrate that PrfA activation adds an additional facet to L. monocytogenes survival by conferring enhanced resistance to oxidative stress. This enhanced resistance relies on gene products whose activity was most notable under conditions of PrfA activation, as loss of these products in wild-type strains resulted in no significant changes in peroxide resistance. It thus appears that specific gene products may uniquely contribute to L. monocytogenes stress resistance under conditions of PrfA activation without themselves being PrfA regulated.

L. monocytogenes resistance to oxidative stress was influenced by bacterial density for both wild-type and prfA* strains (Fig. 1B). Approximately 40% fewer prfA* bacteria than wild-type bacteria were required to survive peroxide challenge, suggesting that prfA* strains are better able to tolerate exposure to specific concentrations of reactive oxygen species. The basis for this resistance is not known, but prfA* strains have been shown to exhibit altered surface properties leading to bacterial aggregation, a situation that may increase local concentrations of bacteria and perhaps limit the exposure of certain members of the population to oxygen radicals.

We identified the sites of transposon insertion for three selected mutants that demonstrated increased sensitivity to peroxide exposure, implicating the gene products of lmo0779, cbpA, and ygbB in oxidative stress resistance under conditions of PrfA activation. None of these three gene products have been previously implicated in oxidative stress resistance, most likely because none of the gene products appear to contribute to the oxidative stress resistance of wild-type strains. The insertion of the transposon in the 5′ upstream region of lmo0779 has the potential to also influence the expression of the divergently transcribed gene lmo0780; however, complementation studies indicated that the introduction of a wild-type copy of lmo0779 was sufficient to restore resistance to prfA* levels. The predicted lmo0779 gene product has no known homologues; however, structural predictions using Phyre2 (39) suggest that Lmo0779 is a putative membrane protein that may feature a cytosolic C-terminal nitrite or sulfite reductase domain, making it likely to be a metal binding enzyme important for nitrogen or sulfur assimilation, respectively. Lmo0779 has a single cysteine residue, and it is possible that this membrane protein may be part of a signal relay that coordinates oxidative stress resistance. While highly conserved among Listeria species with >80% identity among sequenced isolates, lmo0779 gene product homologues are not found among other bacteria.

The cbpA gene product was recently identified as a L. monocytogenes high-affinity cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) receptor protein (43). The protein contains a CBS domain, which binds c-di-AMP, and an ACT domain, which can bind a variety of small molecules (37, 44). The function of CbpA and the ligand of its ACT domain remain unstudied, but CbpA may be involved the sensing or regulation of c-di-AMP. It has been suggested that PrfA activation leads to elevated c-di-AMP levels through inhibition of c-di-AMP phosphodiesterases, though this relationship has not been directly demonstrated (45). c-di-AMP has been shown to regulate L. monocytogenes metabolism, resistance to cell wall-targeting antibiotics, and osmoregulation. Intriguingly, one of the principal functions of c-di-AMP signaling is to control the flux of pyruvate into the citric acid cycle through allosteric inhibition of pyruvate carboxylase (37). Since pyruvate is also the starting substrate for MEP isoprenoid synthesis, increased c-di-AMP might favor increased activity of that pathway, which includes another identified gene, ygbB (34).

The ygbB gene product has also been associated with bacterial metabolism, as it encodes the fifth of seven enzymes in the nonmevalonate (MEP) pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis (34). L. monocytogenes is exceptional among pathogens in possessing both the classical and nonmevalonate pathways for the end product isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), which is essential for growth and survival (46). Isoprenoids and their biosynthetic pathways have only recently begun to be appreciated in bacteria (47, 48) and their derivatives have been implicated in oxidative stress resistance (49). Ostrovsky et al. (49) reported the accumulation of a MEP pathway intermediate, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclopyrophosphate (MEC or MEcPP), in response to benzyl viologen-induced oxidative stress, and stress-resistant mutants accumulated more MEC than sensitive strains. YgbB is the enzyme that generates MEC (34); thus, it is possible that the reduction in L. monocytogenes resistance to peroxide is due to a lack of MEC accumulation resulting from the loss of YgbB. The MEP pathway has been previously shown to be required for L. monocytogenes virulence in mice (34), and the current study confirms an association of the MEP pathway with oxidative stress and with virulence; whether these phenotypes are linked or distinct from one another remains to be determined.

Perhaps notable is the absence of insertions detected within the gene encoding catalase (kat), an enzyme associated with detoxifying peroxide (8). Our finding that PrfA activation does not alter catalase activity further supports the notion that it is not involved in PrfA-mediated peroxide resistance. We also note a recent report that other redox enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase, but not kat are upregulated in wild-type L. monocytogenes subjected to peroxide stress (50). In addition, the loss of catalase does not appear to affect L. monocytogenes virulence in mouse models of infection, and catalase-negative strains have been isolated from human infections (51). These findings suggest a model in which catalase detoxifies peroxide produced by normal respiration but during other periods of peroxide stress, such as potentially found during infection, other mechanisms promote bacterial survival.

The in vivo observation that the transposon insertion mutants exhibited reduced virulence in the liver in the presence of the prfA* allele (Fig. 6) may provide some insight into the role of peroxide resistance during infection. Neutrophils, which produce large amounts of ROS and RNS, have been found to be particularly important for defense against L. monocytogenes in the liver (52–54, 63), a finding that may explain why PrfA-mediated peroxide resistance is more important for bacterial infection within the liver than within the spleen. Mice infected with prfA* strains have previously been shown to have increased bacterial burdens in the liver in comparison to those of mice infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes (16); thus, the contributions of cbpA, lmo0779, and ybgB to oxidative stress resistance may be visible only in this context. The enhanced resistance of prfA* strains to oxidative stress may thus explain the increased fitness of these mutants within the liver, given that mutations that reduce peroxide resistance of prfA* strains to wild-type levels resulted in bacterial numbers of prfA* strains in the liver that were comparable to those of wild-type strains.

Taken together, our results reveal yet another facet of L. monocytogenes physiology that is influenced by the central virulence regulator PrfA, that being enhanced bacterial resistance to oxidative stress under conditions of PrfA activation. Given the recent evidence suggesting that L. monocytogenes uses redox-responsive transcription factors to coordinate virulence factor expression within the host, and that PrfA itself binds a reducing agent (14, 15), it would appear that this bacterium is well positioned for both redox sensing and survival during the course of host infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (55). Female outbred Swiss Webster mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age (Charles River Labs, Boston, MA), were subjected to a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Animals were carefully monitored twice daily for signs of distress (unkempt appearance, hunched posture, and lethargy), and humane endpoints were used in all experiments such that any animal exhibiting severe discomfort, an inability to move around or attain food, water, etc., was euthanized immediately. Euthanasia was carried out via CO2 inhalation from a bottled source followed by cervical dislocation. Animal suffering and distress were minimized by monitoring the animals as described above and in that tail vein injections were carried out with only brief periods (<5 min) of physical restraint.

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

L. monocytogenes 10403S (NF-100) (56), 10403S prfA L140F (prfA* actA-gus-neo, NF-L1166) (24), and 10403S ΔprfA (NF-L890) (57) were used in this study. All bacterial strains were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). Antibiotic concentrations were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 5 μg ml−1; erythromycin, 2 μg ml−1; lincomycin, 25 μg ml−1; neomycin, 10 μg ml−1; and streptomycin, 200 μg ml−1.

Oxidative stress assay.

Strains were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in BHI broth, then subcultured by diluting cultures 1:20 into fresh BHI broth the following day, and grown to mid-log phase. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) for each strain was adjusted to 0.2. Hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted in fresh BHI broth to create a 1 M working solution. In a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, 890 μl of culture was mixed with 110 μl of BHI plus 1 M H2O2 and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Viable bacteria were enumerated by serial dilution in 1× sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), plated on LB agar, and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Quantitative catalase assay.

Quantitative catalase assay was adapted from the procedure described by Iwase et al. (58). Strains were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking in BHI broth, then subcultured by diluting cultures 1:20 into fresh BHI broth the following day, and grown to mid log phase. The OD600 for each stain was adjusted to 1 by centrifugation of an appropriate volume of culture and resuspension of the pellet in PBS. To measure enzyme activity, 10 μl of bacterial suspension was mixed with 10 μl of 1% Triton X-100 and 10 μl of 30% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in a 13-mm by 100-mm borosilicate test tube. After 5 min, the height of the column of bubbles produced in the tube by the generation of O2 from H2O2 was measured. To enable relative comparison of enzyme activity, a standard curve was generated using 2 to 20 μl of the wild-type suspension.

Construction of a random Mariner transposon insertion library.

The L. monocytogenes prfA* strain (NF-L1166) was made electrocompetent as previously described (59). Escherichia coli (NF-E1130) containing the Mariner transposase driven by the Bacillus subtilis mrgA promoter on pMC38 (60) was grown on BHI agar containing 5 μg ml−1 of chloramphenicol overnight and then grown in LB broth. Plasmid pMC38 was purified using the Qiagen (Frederick, MD) plasmid midi-kit. Plasmid pMC38 was introduced into electrocompetent L. monocytogenes 10403S prfA* using a chilled 1-mm electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and pulsed at 10 kV/cm, 400 Ω, and 25 μF. Cells were immediately resuspended in 1 ml of fresh BHI broth containing 500 mM sucrose and incubated statically at 30°C for 1.5 h. Transformants were selected on BHI agar containing 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin. Two independent transformations were carried out to generate two separate independent libraries. Transformants were then grown in fresh BHI broth overnight at 30°C while shaking. Cultures were diluted 1:200 in fresh BHI broth, grown with shaking at 30°C for 1 h, and then shifted to 40°C with shaking for an additional 6 h until the OD600 registered between 0.3 and 0.5. Cultures were then plated on BHI agar plus 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin, with the remainder frozen in 1-ml aliquots with 20% sterile glycerol.

Screening of transposon libraries.

Frozen library aliquots were thawed and plated on BHI agar containing 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin and 10 μg ml−1 of neomycin (to select for PrfA activation as measured by actA-gus-neo expression) and grown overnight at 37°C. Individual colonies were picked into 96-well plates containing 200 μl of BHI broth and grown overnight at 37°C without shaking. The following day, optical densities were measured and 10 μl of each isolate culture was transferred in duplicate to a new 96-well plate containing 190 μl of BHI broth with 40 mM H2O2. Cultures were grown for 48 h at 37°C statically and assessed for growth. Isolates failing to grow were retested under the same conditions before being verified individually. For GUS indicator media plates, a filtered solution of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (XG; Inalco) was added just before pouring to a final concentration of 50 mg ml−1.

Phage transduction.

Bacteriophage U153 was used for phage transduction experiments. Susceptible mutants were grown overnight at 37°C without shaking in 2 ml of BHI plus 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin and 10 μg ml−1 of neomycin and then subcultured 1:10 in 2 ml of fresh BHI broth. Cultures were grown for 3 h at 30°C with shaking. In sterile 12- by 75-mm culture tubes, Listeria mutant cultures were mixed with phage in several ratios from 1:1 to 100:1 and incubated at room temperature statically for 40 min. Three milliliters of liquid LB soft agar (0.75% agar, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgSO4) was added to each tube, mixed, and then poured over a prewarmed LB plate. Plates were grown overnight at room temperature. Two milliliters of TM buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgSO4) was added to the plate with confluent plaques for each mutant. After 20 min, the soft agar with TM buffer was scraped into a 15-ml centrifuge tube (Denville Scientific, South Plainfield, NJ) with a flame-sterilized scoop and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected into a sterile microcentrifuge tube and 1/5 volume of chloroform was added. The solution was incubated at room temperature with rocking for 30 min. The recovered phage suspensions were incubated with either the 10403S or NF-L1166 (prfA*) strain for the recovery of transductants containing the selected transposon insertion as follows. Listeria strains for phage transduction were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking, subcultured 1:40 in fresh BHI the following day, and grown at 30°C shaking to an OD of ∼0.19. In separate tubes, 200 μl of Listeria was mixed with 100 μl of the phage library, plus 10 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgSO4, and incubated at room temperature for 40 min with gentle shaking every 10 min. Each tube was then supplemented with 200 μl of fresh BHI and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 2 h. The cultures were plated on BHI plus 2 μg ml−1 of erythromycin and grown overnight at 37°C. Finally, each transductant was confirmed for the transposon-encoded erythromycin resistance by streaking each colony on plates with BHI plus 25 μg ml−1 of lincomycin.

Inverse PCR to identify transposon insertion sites.

Genomic DNA of sensitive mutants was isolated with the GenElute bacterial DNA genomic DNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Genomic DNA was restriction digested with DpnI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Digests were ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs) overnight at 16°C. Ligated loops were PCR amplified with primers p255-1 and Marq255, gel purified on a 0.8% Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) agarose gel with the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and then Sanger sequenced with primer TnSeq (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Feature(s)a | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| NF-100 | 10403S parent strain | 56 |

| NF-1166 | 10403S prfA L140F actA-gus-neo-plcB (prfA* strain) | 18 |

| NF-890 | 10403S ΔprfA | 27 |

| NF-4239 | prfA* ygbB::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4238 | 10403S ygbB::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4241 | prfA* cbpA::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4240 | 10403S cbpA::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4242 | prfA* lmo0779::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4241 | 10403S lmo0779::tnHimar1 | This study |

| NF-4245 | prfA* ygbB::tnHimar1 + pPL2-ygbB | This study |

| NF-4247 | prfA* cbpA::tnHimar1 + pPL2-cbpA | This study |

| NF-4249 | prfA* lmo0779::tnHimar1 + pPL2-lmo0779 | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pPL2 | Single-copy integration vector | 61 |

| pPL2-ygbB | ygbB complementation vector | This study |

| pPL2-cbpA | cbpA complementation vector | This study |

| pPL2-lmo0779 | lmo0779 complementation vector | This study |

| Primer | ||

| p255-1 | 5′-TCT TTT AGC AAA CCC GTA TTC CAC G-3′ | This study |

| Marq255 | 5′-CAG TAC AAT CTG CTC TGA TGC CGC ATA GTT-3′ | 60 |

| TnSeq | 5′-ACA ATA AGG ATA AAT TTG AAT ACT AGT CTC GAG TGG GG-3′ | This study |

| ygbB_BamHI_F2 | 5′-CAC GGG ATC CTT GAG CGA ATT CCT TGT CCT-3′ | This study |

| ygbB_BamHI_R3 | 5′-CAG CGG ATC CGT ACA CGC ACT CGT TTT GT-3′ | This study |

| cbpA_BamHI_F1 | 5′-CGG GAT CCT CATTTT CAA GCT GTT TCA-3′ | This study |

| cbpA_BamHI_R2 | 5′-GCG GAT CCC GTT CTA CAC TTC CAC CAC CA-3′ | This study |

| lmo0779_BamHI_F2 | 5′-CGG GAT CCG GAA GTA AGC GTG GCG TTT-3′ | This study |

| lmo0779_BamHI_R2 | 5′-GCG GAT CCT TTT GTT AAC CAA CCG TGT C-3′ | This study |

| RT-PCR primer | ||

| ybgB_F | 5′-CAT AGG CGC AAT TGG TGC TG-3′ | This study |

| ygbB_R | 5′-ACC ATC CGC CTC TAC CTT CT-3′ | This study |

| cbpA_F | 5′-ACA CGA AGT CCT TTG CGT TC-3′ | This study |

| cbpA_R | 5′-CAT TCG CCG CGT ACT TGT TT-3′ | This study |

| lmo0779_F | 5′-CGA ACT GCG GAA GAA GCA GA-3′ | This study |

| lmo0779_R | 5′-GTG GTC GTT GGG ACG GTT AT-3′ | This study |

| prfA_F | 5′-GCT TGG CTC TAT TTG CGG TC-3′ | This study |

| prfA_R | 5′-AAC AGC TGA GCT ATG TGC GA-3′ | This study |

| actA_F | 5′-GCG AAG GAA GAA CCA GGG AA-3′ | This study |

| actA_R | 5′-ACG CCC CTA AAG AGA ACA CG-3′ | This study |

| kat_F | 5′-AGA AGC TTG CTC CGT CGA AA-3′ | This study |

| kat_R | 5′-GGG CTC TAG TGT TCA TGC GT-3′ | This study |

| 16S_F | 5′-GAG TAC GAC CGC AAG GTT GA-3′ | This study |

| 16S_R | 5′-CCT GGT AAG GTT CTT CGC GT-3′ | This study |

Underlined nucleotides indicate inserted restriction sites used for cloning.

Complementation of LMRG_00235 (lmo0553 or cbpB), LMRG_00467 (lmo0779), and LMRG_02671 (lmo0236 or ygbB).

Each gene was PCR amplified from the 10403S genome using primers listed in Table 1, restriction digested with BamHI overnight at 16°C, and then treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) for 1 h at 37°C. The digested fragment was ligated into plasmid pPL2 (61) and sequence verified. The constructs were electroporated into E. coli SM10 cells and subsequently mated into L. monocytogenes prfA* to generate prfA* cbpB::tnHimar1, prfA* lmo0779::tnHimar1, or prfA* ygbB::tnHimar1 mutants and selected for on BHI agar containing 200 μg ml−1 of streptomycin and 5 μg ml−1 of chloramphenicol.

RNA extraction and cDNA preparation.

Isolated colonies for each strain were picked from BHI agar plates into 5 ml of BHI broth and incubated with shaking at 37°C overnight. The following day, each culture was diluted 1:10 into fresh BHI broth and incubated with shaking at 37°C for 1.5 h. Two milliliters of each culture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and supernatant was discarded. Each pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was isolated per the manufacturer’s protocol and dissolved in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0; Millipore-Sigma). RNA was treated with the Turbo DNase kit (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) and quantified on a NanoDrop OneC spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). cDNA was synthesized with a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and diluted in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water.

qRT-PCR.

Primers for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) were designed using PrimerBLAST (NCBI) and synthesized by Millipore-Sigma and are listed in Table 1. Samples were prepared using Fast SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) with 200 nM final primer concentrations in 10-μl reaction volumes and run in 96-well plates on a ViiA 7 quantitative PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was assessed in triplicate for each sample and normalized to 16S rRNA.

Animal infections.

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Animal Care Committee and were conducted in the Biological Resources Laboratory. A total of 1 × 104 CFU of each strain were injected via tail vein into 6- to 8-week-old Swiss Webster mice (Charles River) as previously described (62). After 72 h, mice were sacrificed and livers and spleens isolated, homogenized, and plated on LB agar for enumeration of bacterial burdens in each organ.

Statistical analyses.

Gene expression data were analyzed using two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey multiple-comparison test (MCT). In vivo infection assays were tested for significance using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test as appropriate. All statistical tests were performed using Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lavanya Visvabharathy for initial observations leading to this study and Grischa Chen and John-Demian Sauer for assistance and advice with inverse PCR protocols. Members of the Freitag lab and the UIC Positive Thinking group provided valuable feedback and discussion.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI041816-18A1 to N.E.F.

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding source. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes—from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NicAogáin K, O’Byrne CP. 2016. The role of stress and stress adaptations in determining the fate of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes in the food chain. Front Microbiol 7:1865. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes Infect 9:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czuprynski CJ. 2005. Listeria monocytogenes: silage, sandwiches and science. Anim Health Res Rev 6:211–217. doi: 10.1079/ahr2005111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lecuit M. 2005. Understanding how Listeria monocytogenes targets and crosses host barriers. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:430–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2005. Gastrointestinal phase of Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Appl Microbiol 98:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slauch JM. 2011. How does the oxidative burst of macrophages kill bacteria? Still an open question. Mol Microbiol 80:580–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staerck C, Gastebois A, Vandeputte P, Calenda A, Larcher G, Gillmann L, Papon N, Bouchara JP, Fleury MJJ. 2017. Microbial antioxidant defense enzymes. Microb Pathog 110:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam GY, Fattouh R, Muise AM, Grinstein S, Higgins DE, Brumell JH. 2011. Listeriolysin O suppresses phospholipase C-mediated activation of the microbicidal NADPH oxidase to promote Listeria monocytogenes infection. Cell Host Microbe 10:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu H, Yuan J, Gao H. 2015. Microbial oxidative stress response: novel insights from environmental facultative anaerobic bacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys 584:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dons LE, Mosa A, Rottenberg ME, Rosenkrantz JT, Kristensson K, Olsen JE. 2014. Role of the Listeria monocytogenes 2-Cys peroxiredoxin homologue in protection against oxidative and nitrosative stress and in virulence. Pathog Dis 70:70–74. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim K-P, Hahm B-K, Bhunia AK. 2007. The 2-cys peroxiredoxin-deficient Listeria monocytogenes displays impaired growth and survival in the presence of hydrogen peroxide in vitro but not in mouse organs. Curr Microbiol 54:382–387. doi: 10.1007/s00284-006-0487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rea R, Hill C, Gahan CGM. 2005. Listeria monocytogenes PerR mutants display a small-colony phenotype, increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide, and significantly reduced murine virulence. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8314–8322. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8314-8322.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reniere ML, Whiteley AT, Hamilton KL, John SM, Lauer P, Brennan RG, Portnoy DA. 2015. Glutathione activates virulence gene expression of an intracellular pathogen. Nature 517:170–173. doi: 10.1038/nature14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiteley AT, Ruhland BR, Edrozo MB, Reniere ML. 2017. A redox-responsive transcription factor is critical for pathogenesis and aerobic growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 85:e00978-16. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00978-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruno JC, Freitag NE. 2010. Constitutive activation of PrfA tilts the balance of Listeria monocytogenes fitness towards life within the host versus environmental survival. PLoS One 5:e15138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruno JC, Freitag NE. 2011. Listeria monocytogenes adapts to long-term stationary phase survival without compromising bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol Lett 323:171–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Port GC, Freitag NE. 2007. Identification of novel Listeria monocytogenes secreted virulence factors following mutational activation of the central virulence regulator, PrfA. Infect Immun 75:5886–5897. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scortti M, Monzó HJ, Lacharme-Lora L, Lewis DA, Vázquez-Boland JA. 2007. The PrfA virulence regulon. Microbes Infect 9:1196–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shetron-Rama LM, Marquis H, Bouwer HGA, Freitag NE. 2002. Intracellular induction of Listeria monocytogenes actA expression. Infect Immun 70:1087–1096. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.3.1087-1096.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xayarath B, Freitag NE. 2012. Optimizing the balance between host and environmental survival skills: lessons learned from Listeria monocytogenes. Future Microbiol 7:839–852. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xayarath B, Volz KW, Smart JI, Freitag NE. 2011. Probing the role of protein surface charge in the activation of PrfA, the central regulator of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. PLoS One 6:e23502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ripio MT, Domínguez-Bernal G, Lara M, Suárez M, Vazquez-Boland JA. 1997. A Gly145Ser substitution in the transcriptional activator PrfA causes constitutive overexpression of virulence factors in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 179:1533–1540. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1533-1540.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miner MD, Port GC, Freitag NE. 2008. Functional impact of mutational activation on the Listeria monocytogenes central virulence regulator PrfA. Microbiology (Reading) 154:3579–3589. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/021063-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shetron-Rama LM, Mueller K, Bravo JM, Bouwer HGA, Way SS, Freitag NE. 2003. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes mutants with high-level in vitro expression of host cytosol-induced gene products. Mol Microbiol 48:1537–1551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vega Y, Rauch M, Banfield MJ, Ermolaeva S, Scortti M, Goebel W, Vázquez-Boland JA. 2004. New Listeria monocytogenes prfA* mutants, transcriptional properties of PrfA* proteins and structure-function of the virulence regulator PrfA. Mol Microbiol 52:1553–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong KKY, Freitag NE. 2004. A novel mutation within the central Listeria monocytogenes regulator PrfA that results in constitutive expression of virulence gene products. J Bacteriol 186:6265–6276. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6265-6276.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xayarath B, Smart JI, Mueller KJ, Freitag NE. 2011. A novel C-terminal mutation resulting in constitutive activation of the Listeria monocytogenes central virulence regulatory factor PrfA. Microbiology (Reading) 157:3138–3149. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deshayes C, Bielecka MK, Cain RJ, Scortti M, de las Heras A, Pietras Z, Luisi BF, Núñez Miguel R, Vázquez-Boland JA. 2012. Allosteric mutants show that PrfA activation is dispensable for vacuole escape but required for efficient spread and Listeria survival in vivo. Mol Microbiol 85:461–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasanthakrishnan RB, de Las Heras A, Scortti M, Deshayes C, Colegrave N, Vázquez-Boland JA. 2015. PrfA regulation offsets the cost of Listeria virulence outside the host. Environ Microbiol 17:4566–4579. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chico-Calero I, Suárez M, González-Zorn B, Scortti M, Slaghuis J, Goebel W, Vázquez-Boland JA, European Listeria Genome Consortium. 2002. Hpt, a bacterial homolog of the microsomal glucose-6-phosphate translocase, mediates rapid intracellular proliferation in Listeria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:431–436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012363899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller KJ, Freitag NE. 2005. Pleiotropic enhancement of bacterial pathogenesis resulting from the constitutive activation of the Listeria monocytogenes regulatory factor PrfA. Infect Immun 73:1917–1926. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1917-1926.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers JT, Tsang AW, Swanson JA. 2003. Localized reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates inhibit escape of Listeria monocytogenes from vacuoles in activated macrophages. J Immunol 171:5447–5453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Begley M, Bron PA, Heuston S, Casey PG, Englert N, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Gahan CGMM, Hill C. 2008. Analysis of the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways in Listeria monocytogenes reveals a role for the alternative 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway in murine infection. Infect Immun 76:5392–5401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01376-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2002. Bile stress response in Listeria monocytogenes LO28: adaptation, cross-protection, and identification of genetic loci involved in bile resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:6005–6012. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.12.6005-6012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee ED, Navas KI, Portnoy DA. 2020. The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis supports anaerobic growth of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun 88:e00788-19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00788-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteley AT, Garelis NE, Peterson BN, Choi PH, Tong L, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA. 2017. c-di-AMP modulates Listeria monocytogenes central metabolism to regulate growth, antibiotic resistance and osmoregulation. Mol Microbiol 104:212–233. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. 2010. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camejo A, Buchrieser C, Couvé E, Carvalho F, Reis O, Ferreira P, Sousa S, Cossart P, Cabanes D. 2009. In vivo transcriptional profiling of Listeria monocytogenes and mutagenesis identify new virulence factors involved in infection. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000449. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen KN, Larsen MH, Gahan CGM, Kallipolitis B, Wolf XA, Rea R, Hill C, Ingmer H. 2005. The Dps-like protein Fri of Listeria monocytogenes promotes stress tolerance and intracellular multiplication in macrophage-like cells. Microbiology (Reading) 151:925–933. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scortti M, Lacharme-Lora L, Wagner M, Chico-Calero I, Losito P, Vázquez-Boland JA. 2006. Coexpression of virulence and fosfomycin susceptibility in Listeria: molecular basis of an antimicrobial in vitro-in vivo paradox. Nat Med 12:515–517. doi: 10.1038/nm1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sureka K, Choi PH, Precit M, Delince M, Pensinger DA, Huynh TN, Jurado AR, Goo YA, Sadilek M, Iavarone AT, Sauer J-D, Tong L, Woodward JJ. 2014. The cyclic dinucleotide c-di-AMP is an allosteric regulator of metabolic enzyme function. Cell 158:1389–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant GA. 2006. The ACT domain: a small molecule binding domain and its role as a common regulatory element. J Biol Chem 281:33825–33829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Portman JL, Dubensky SB, Peterson BN, Whiteley AT, Portnoy DA. 2017. Activation of the Listeria monocytogenes virulence program by a reducing environment. mBio 8:e01595-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01595-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Begley M, Gahan CGMM, Kollas A-KK, Hintz M, Hill C, Jomaa H, Eberl M. 2004. The interplay between classical and alternative isoprenoid biosynthesis controls γδ T cell bioactivity of Listeria monocytogenes. FEBS Lett 561:99–104. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cane DE, Ikeda H. 2012. Exploration and mining of the bacterial terpenome. Acc Chem Res 45:463–472. doi: 10.1021/ar200198d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heuston S, Begley M, Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2012. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacterial pathogens. Microbiology (Reading) 158(Part 6):1389–1401. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.051599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ostrovsky D, Diomina G, Lysak E, Matveeva E, Ogrel O, Trutko S. 1998. Effect of oxidative stress on the biosynthesis of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclopyrophosphate and isoprenoids by several bacterial strains. Arch Microbiol 171:69–72. doi: 10.1007/s002030050680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cortes BW, Naditz AL, Anast JM, Schmitz-Esser S. 2019. Transcriptome sequencing of Listeria monocytogenes reveals major gene expression changes in response to lactic acid stress exposure but a less pronounced response to oxidative stress. Front Microbiol 10:3110. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leblond-Francillard M, Gaillard JL, Berche P. 1989. Loss of catalase activity in Tn1545-induced mutants does not reduce growth of Listeria monocytogenes in vivo. Infect Immun 57:2569–2573. doi: 10.1128/IAI.57.8.2569-2573.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carr KD, Sieve AN, Indramohan M, Break TJ, Lee S, Berg RE. 2011. Specific depletion reveals a novel role for neutrophil-mediated protection in the liver during Listeria monocytogenes infection. Eur J Immunol 41:2666–2676. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conlan JW, Dunn PL, North RJ. 1993. Leukocyte-mediated lysis of infected hepatocytes during listeriosis occurs in mice depleted of NK cells or CD4+ CD8+ Thy1.2+ T cells. Infect Immun 61:2703–2707. doi: 10.1128/IAI.61.6.2703-2707.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conlan JW, North RJ. 1991. Neutrophil-mediated dissolution of infected host cells as a defense strategy against a facultative intracellular bacterium. J Exp Med 174:741–744. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bishop DK, Hinrichs DJ. 1987. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. The influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J Immunol 139:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miner MD, Port GC, Bouwer HGA, Chang JC, Freitag NE. 2008. A novel prfA mutation that promotes Listeria monocytogenes cytosol entry but reduces bacterial spread and cytotoxicity. Microb Pathog 45:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iwase T, Tajima A, Sugimoto S, Okuda KI, Hironaka I, Kamata Y, Takada K, Mizunoe Y. 2013. A simple assay for measuring catalase activity: a visual approach. Sci Rep 3:3081–3084. doi: 10.1038/srep03081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monk IR, Gahan CGMM, Hill C. 2008. Tools for functional postgenomic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3921–3934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00314-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao M, Bitar AP, Marquis H. 2007. A mariner-based transposition system for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2758–2761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lauer P, Chow MYN, Loessner MJ, Portnoy DA, Calendar R. 2002. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J Bacteriol 184:4177–4186. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alonzo F, Port GC, Cao M, Freitag NE. 2009. The posttranslocation chaperone PrsA2 contributes to multiple facets of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun 77:2612–2623. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00280-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang J. 2018. Neutrophils in tissue injury and repair. Cell Tissue Res 371:531–539. doi: 10.1007/s00441-017-2785-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.