Pseudomonas sp. strain XWY-1 is a carbaryl-degrading strain that utilizes carbaryl as the sole carbon and energy source for growth. The functional genes involved in the degradation of carbaryl have already been reported.

KEYWORDS: 1-naphthol, McbG, Pseudomonas sp. XWY-1

ABSTRACT

Although enzyme-encoding genes involved in the degradation of carbaryl have been reported in Pseudomonas sp. strain XWY-1, no regulator has been identified yet. In the mcbABCDEF cluster responsible for the upstream pathway of carbaryl degradation (from carbaryl to salicylate), the mcbA gene is constitutively expressed, while mcbBCDEF is induced by 1-naphthol, the hydrolysis product of carbaryl by McbA. In this study, we identified McbG, a transcriptional activator of the mcbBCDEF cluster. McbG is a 315-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 35.7 kDa. It belongs to the LysR family of transcriptional regulators and shows 28.48% identity to the pentachlorophenol (PCP) degradation transcriptional activation protein PcpR from Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723. Gene disruption and complementation studies reveal that mcbG is essential for transcription of the mcbBCDEF cluster in response to 1-naphthol in strain XWY-1. The results of the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNase I footprinting show that McbG binds to the 25-bp motif in the mcbBCDEF promoter area. The palindromic sequence TATCGATA within the motif is essential for McbG binding. The binding site is located between the –10 box and the transcription start site. In addition, McbG can repress its own transcription. The EMSA results show that a 25-bp motif in the mcbG promoter area plays an important role in McbG binding to the promoter of mcbG. This study reveals the regulatory mechanism for the upstream pathway of carbaryl degradation in strain XWY-1. The identification of McbG increases the variety of regulatory models within the LysR family of transcriptional regulators.

IMPORTANCE Pseudomonas sp. strain XWY-1 is a carbaryl-degrading strain that utilizes carbaryl as the sole carbon and energy source for growth. The functional genes involved in the degradation of carbaryl have already been reported. However, the regulatory mechanism has not been investigated yet. Previous studies demonstrated that the mcbA gene, responsible for hydrolysis of carbaryl to 1-naphthol, is constitutively expressed in strain XWY-1. In this study, we identified a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, McbG, which activates the mcbBCDEF gene cluster responsible for the degradation of 1-naphthol to salicylate and represses its own transcription. The DNA binding site of McbG in the mcbBCDEF promoter area contains a palindromic sequence, which affects the binding of McbG to DNA. These findings enhance our understanding of the mechanism of microbial degradation of carbaryl.

INTRODUCTION

Carbaryl (1-naphthyl-N-methylcarbamate) is a carbamate insecticide widely used in agricultural and forestry pest control (1). However, carbaryl residues are considered an environmental pollutant because carbaryl inhibits the activity of acetylcholinesterase and poses a potential threat to humans and other nontarget organisms; therefore, it has attracted increasing attention (2). Bioremediation has received increasing attention as a reliable and environmentally friendly approach to clean up polluted environments (3), and research on the mechanism of microbial degradation of carbaryl will help in the bioremediation of carbaryl polluted environments. To date, several carbaryl-degrading strains have been reported from the genera Pseudomonas (4–7), Sphingobium (8), Novosphingobium (9, 10), Rhizobium (11, 12), Pseudaminobacter (13), Rhodococcus (14), Achromobacter (15), and Arthrobacter (16). Among these, the mechanisms of carbaryl degradation in Pseudomonas sp. strain C5pp and Pseudomonas sp. strain XWY-1 have been extensively investigated (17, 18).

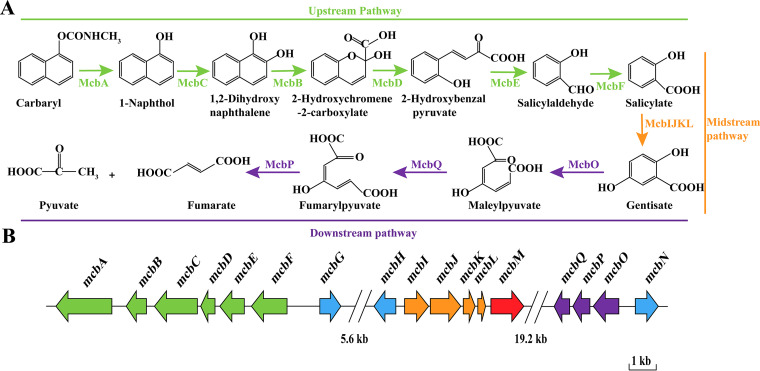

The complete degradation pathway of carbaryl has been elucidated in strain C5pp, including the upstream pathway from carbaryl to salicylate, the midstream pathway from salicylate to gentisate, and the downstream pathway from gentisate to pyruvate and fumarate (18). The genome of this strain has been sequenced, and the enzyme-encoding genes involved in the degradation have also been identified (18, 19). However, no regulator of this pathway has yet been identified. Strain XWY-1 was isolated in our lab and utilized carbaryl and its metabolite 1-naphthol as sole carbon sources for growth. Moreover, strain XWY-1 degraded carbaryl through the same pathway as strain C5pp. Comparison of the genomes of strains XWY-1 and C5pp showed that it also harbors the same mcbABCDEFG, mcbHIJKLM, and mcbNOPQ clusters as strain C5pp, which encodes the entire degradation pathway of carbaryl. Like strain C5pp, no regulatory genes have yet been identified for the carbaryl degradation pathway in strain XWY-1 (Fig. 1) (17).

FIG 1.

The carbaryl metabolism pathway and the involved genes in strain XWY-1. (A) The carbaryl degradation pathway. The green line indicates the upstream pathway, the orange line indicates the midstream pathway, and the purple line indicates the downstream pathway. (B) The involved carbaryl-degrading gene clusters. The green arrow indicates the gene cluster for upstream pathway, the orange arrow indicates the gene cluster for midstream pathway, the purple arrow indicates the gene cluster for downstream metabolism, the blue arrow indicates the putative regulatory protein, and the red arrow indicates the putative transporter. McbG shared the highest similarity (28.48%) with the LysR family transcriptional regulator PcpR (GenBank accession number P52679.2), McbH shared the highest similarity (68.67%) with the HTH-type transcriptional activator NahR (P10183.2), McbN shared the highest similarity (36.01%) with the HTH-type transcriptional regulator GbpR (P52661.1), and McbM shared the highest similarity (42.39%) with the 3-hydroxybenzoate transporter MhbT (Q5EXK5.1).

In the mcbABCDEF cluster responsible for the upstream pathway of carbaryl degradation, the mcbA gene responsible for hydrolysis of carbaryl to 1-naphthol is constitutively expressed in strain XWY-1, while the mcbBCDEF cluster, responsible for the degradation of 1-naphthol to salicylate, is induced by 1-naphthol (20). In the present study, a LysR family transcriptional regulator, McbG, was identified as the transcriptional activator of the mcbBCDEF cluster in response to 1-naphthol in strain XWY-1 by using DNA alignment. The regulatory mechanism, including the transcription start site (TSS), the binding site, the core binding sequence, and the effect of substrate on its binding were investigated. In addition, the regulatory mechanism of mcbG itself by 1-naphthol was also investigated. The identification of McbG deepens our understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of carbaryl degradation.

RESULTS

Determination of the TSS of the mcbBCDEF cluster.

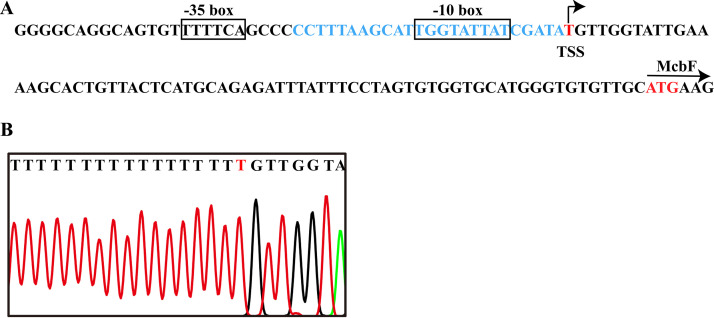

The promoter of the mcbBCDEF cluster was predicted by the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) Neural Network Promoter Prediction online program (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) with a score of >0.8 in the region upstream of the mcbF gene. The T was the 69th base upstream of the translational start codon of mcbF. The –10 box TGGTATTAT and the –35 box TTTTCA were predicted based on the identified TSS (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

(A) DNA elements in the promoter of mcbBCDEF cluster. The –35 and –10 boxes are shown in boxes, and the TSS is shown by an arrow. The McbG-binding site is indicated by the blue sequence. (B) Chromatograms display the partial sequences of the 5′ RACE products. The red letter T indicates the TSS.

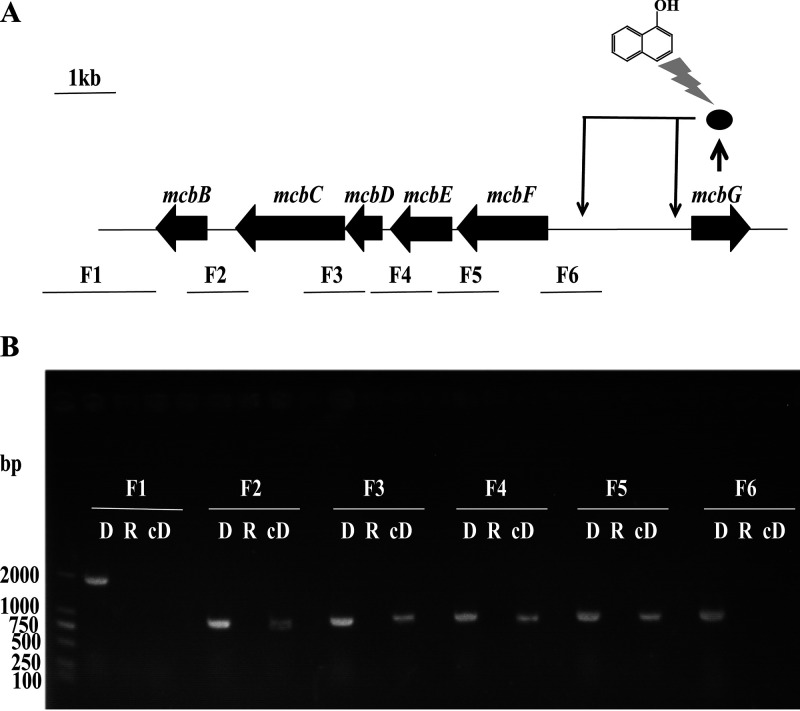

All of the six fragments (F1 to F6) within the mcbBCDEF cluster were amplified using cDNA derived from strain XWY-1 induced by 1-naphthol as the template (Fig. 3A and B), indicating that the mcbB, mcbC, mcbD, mcbE, and mcbF genes were in one operon and transcribed in a single unit.

FIG 3.

(A) Schematic diagram of the transcriptional regulation of McbG. The DNA fragments that are located at same positions in the genome are shown. The ellipse represents the protein McbG, which activates the transcription of the mcbBCDEF cluster and releases the self-repression of McbG in the presence of 1-naphthol (displayed as a solid line). The scale bar represents 1 kb. The amplification fragments for transcriptional unit evaluation are shown under the mcbBCDEF cluster as lines. (B) PCR amplification of the mcbBCDEF cluster using DNA (D), total RNA (R), and cDNA (cD) as the templates. The amplified products were detected by electrophoresis.

McbG is a transcriptional activator of the mcbBCDEF cluster.

McbG was discovered upon alignment of the genomes of strain XWY-1 and strain C5pp. There was 100% identity between McbG of strains XWY-1 and C5pp. However, among the previously identified regulatory proteins (the UniProt Knowledge Base/Swiss-Prot databases), McbG shared the highest similarity (28.48%) only with the LysR family transcriptional regulator PcpR (GenBank accession number P52679.2) from the pentachlorophenol (PCP)-degrading strain Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). McbG contains 315 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 35.7 kDa. The N-terminal amino acids 18 to 77 form a helix-turn-helix (HTH_XRE superfamily) domain, which is characteristic of transcriptional regulators.

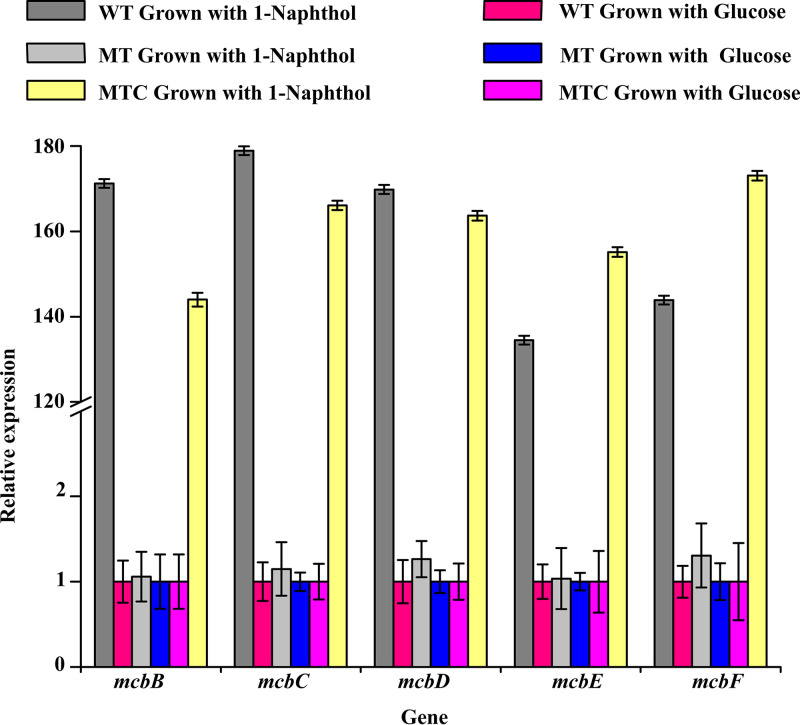

The mcbG gene of strain XWY-1 was deleted to generate a knockout strain, MT. A complementation strain, MTC, was generated by transforming MT with plasmid pBmcbG. Cells of strains XWY-1, MT, and MTC were incubated with or without 1-naphthol. The transcription levels of the mcbB, mcbC, mcbD, mcbE, and mcbF genes were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4, when supplemented with 1-naphthol, the transcription levels of mcbB, mcbC, mcbD, mcbE, and mcbF in strain XWY-1 were 171-, 178-, 169-, 134-, and 143-fold higher, respectively, than in the absence of 1-naphthol. In the knockout strain MT, the transcription levels of these genes were similar in the presence or absence of 1-naphthol. In the mcbG-complemented strain MTC, the transcription levels were similar to the wild-type strain XWY-1 (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Transcriptional analysis of mcbB, mcbC, mcbD, mcbE, and mcbF in strains XWY-1 (WT), the mcbG knockout mutant (MT), and the mcbG-complemented strain (MTC) in the presence of 0.1 mM glucose or 0.1 mM 1-naphthol. The transcriptional level of the 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal standard, and the data in each column were calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method using three replicates.

Cells of the strains XWY-1, MT, and MTC were incubated in mineral salts medium (MSM) supplemented with 0.1 mM 1-naphthol as the sole carbon source. As shown in Fig. S2, strain MT lost its ability to degrade 1-naphthol, which was regained in strain MTC carrying plasmid pBmcbG to levels similar to that of strain XWY-1. These results demonstrate that mcbG is essential for degradation of 1-naphthol in strain XWY-1.

McbG binds to mcbBCDEF promoter DNA.

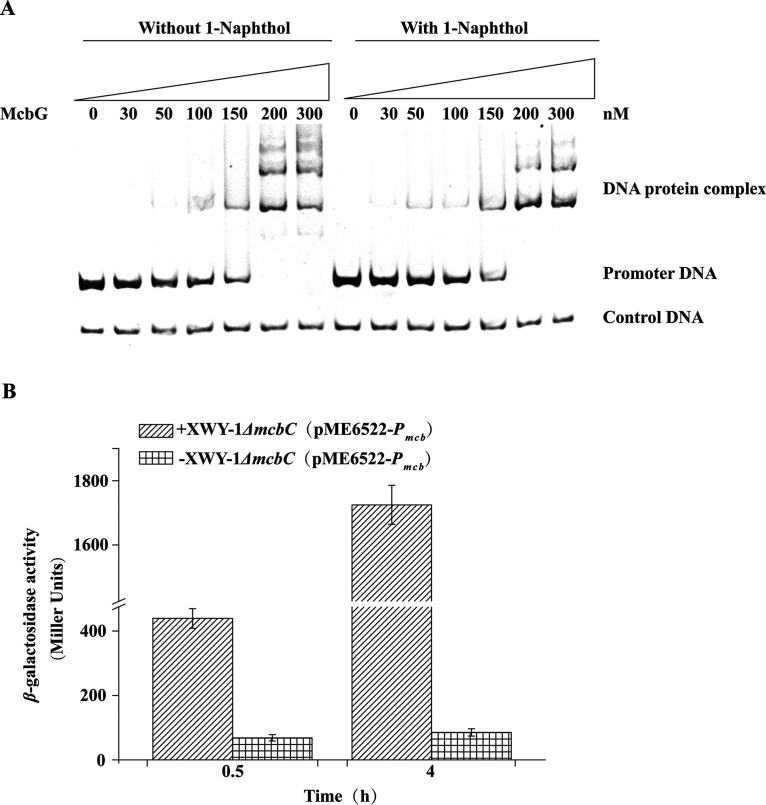

The mcbG was overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3), and McbG was purified. Purified McbG appeared as a single band on SDS-PAGE, with a molecular mass of 35.7 kDa, which is in agreement with its theoretical molecular mass (Fig. S3). McbG was subjected to an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to test its binding capacity toward mcbBCDEF promoter DNA. When 50 nM McbG was added, a DNA-protein complex was observed (Fig. 5A). No DNA-protein complex was detected for the nonspecific control DNA (partial sequence of mcbC). When 1-naphthol was incubated with the promoter of mcbBCDEF and McbG, the binding capacity of McbG to the promoter was improved, especially at a lower concentration of 30 nM (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that McbG can bind to the mcbBCDEF promoter DNA, and 1-naphthol can enhance this binding.

FIG 5.

(A) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays on the binding of McbG to the mcbBCDEF cluster promoter. Each lane contains 20 ng of DNA probe. The first 7 lanes show samples incubated without 1-naphthol, and the next 7 lanes show samples incubated with 0.05 mM 1-naphthol. The concentrations of McbG, increasing from left to right, are shown above the lanes. The control DNA was a 200-bp fragment that was amplified from the mcbC gene. (B) In vivo inducer identification. A β-galactosidase assay was performed with XWY-1 ΔmcbC (pME6522-Pmcb) carrying the Pmcb-lacZ transcriptional fusion, grown in the presence (+XWY-1 ΔmcbC [pME6522-Pmcb]) or absence (−XWY-1 ΔmcbC [pME6522-Pmcb]) of 0.1 mM 1-naphthol. β-Galactosidase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each value is the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three cultures.

1-Naphthol as effector to activate mcbBCDEF cluster transcription.

To determine the effector of McbG, the mcbC gene, responsible for converting 1-naphthol to 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene (Fig. 1), was knocked out to generate strain XWY-1 ΔmcbC. A reporter plasmid, pME6522-Pmcb (the fragment upstream of TSS of mcbBCDEF was fused with lacZ in the promoter probe plasmid pME6522 [21] to generate to pME6522-Pmcb), was then introduced into strain XWY-1 ΔmcbC. The strain was then cultured in GM (MSM with glucose as the sole carbon source) with or without 1-naphthol. Very low β-galactosidase activity (<65 Miller units) was detected in strain XWY-1 ΔmcbC grown in the absence 1-naphthol, while approximately 1,700 Miller units of activity was observed in XWY-1 ΔmcbC grown in the presence of 1-naphthol (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that 1-naphthol is an effector of the mcbBCDEF cluster and not its subsequent metabolites.

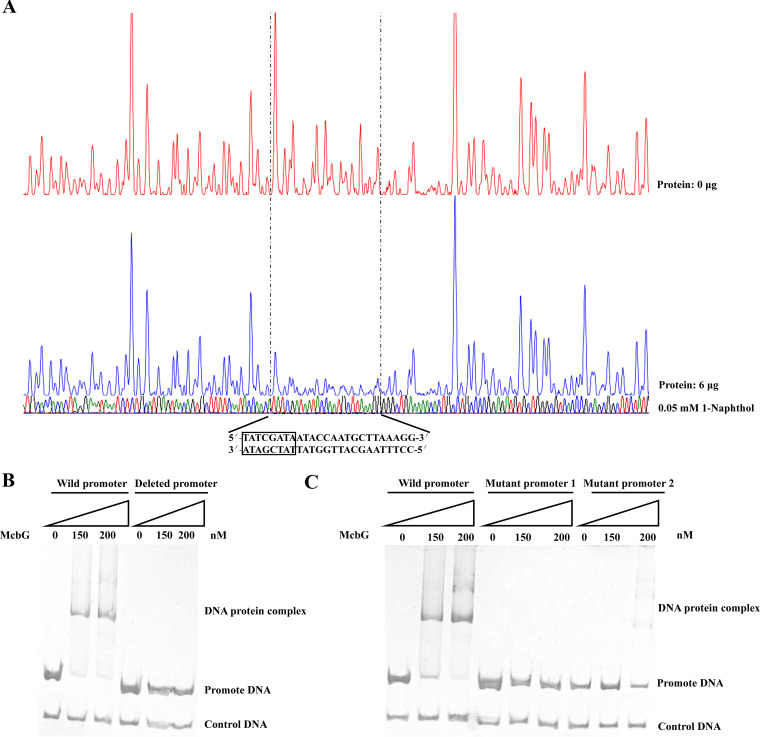

Binding site of McbG to the mcbBCDEF promoter.

A DNase I footprinting assay was performed to identify the McbG-binding site in the promoter region of mcbBCDEF. It was found that McbG protected the 25-bp motif CCTTTAAGCATTGGTATTATCGATA (Fig. 6A), spanning base pairs −1 to −25 in the mcbBCDEF promoter (Fig. 2A), and was located between the −10 box and the transcription start site (Fig. 2A). Upon deletion of the 25-bp motif, EMSA results revealed that McbG could no longer bind to the DNA probe (Fig. 6B). The 25-bp motif harbors a palindromic sequence, 5′-TATCGATA-3′. To determine whether this palindromic sequence is essential for McbG binding, it was mutated to 5′-TTTAACCC-3′. EMSA analysis showed that the mutated DNA probe no longer bound to McbG (Fig. 6C). Additionally, to determine the role of other 17-bp sequences in binding, the 25-bp motif was mutated to AGGTAAGGTAAGGTAATTATCGATA (mutated sequences underlined). When this was used as a probe, a weakening of cohesion was observed (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that the palindromic sequence plays an important role in McbG sequence recognition.

FIG 6.

(A) DNase I footprinting analysis of the McbG-binding site in the mcbBCDEF promoter. A total of 400 ng of 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled DNA probe was incubated without McbG (red line) or with 6 μg McbG (blue line) in the presence of 0.05 mM 1-naphthol. The McbG-protected region is shown in the dashed box, and the protected sequence is shown at the bottom. The palindromic sequence in the protected region is shown in black box. (B) McbG binding to the promoter DNA with the 25-bp motif deleted. The first three lanes are wild-type mcbBCDEF promoter DNA, which was used as the control, and the next three lanes are 25-bp motif-deleted DNA probes. The sample in each lane was incubated with 0.05 mM 1-naphthol. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of McbG binding to the mutant mcbBCDEF cluster promoter DNA. The nucleotide sequence 5′-TATCGATA-3′ in the McbG-binding site was mutated to 5′-TTTAACCC-3′ (mutant promoter 1), and the nucleotide sequence 5′-CCTTTAAGCATTGGTAT-3′ in the McbG-binding site was mutated to 5′-AGGTAAGGTAAGGTAAT-3′ (mutant promoter 2). The first 3 lanes show wild-type mcbBCDEF promoter DNA, which was used as the positive control, the middle 3 lanes contain mutant promoter 1 DNA, and the last 3 lanes contain mutant promoter 2 DNA. The sample in each lane was incubated with 0.05 mM 1-naphthol.

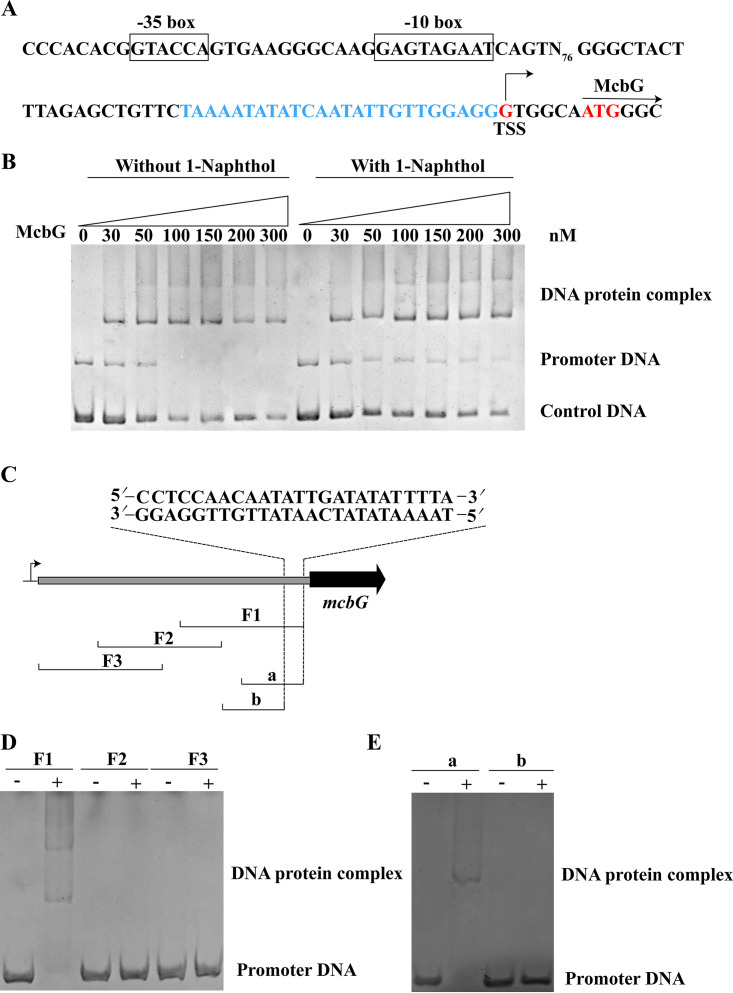

1-Naphthol relieves the self-repression of McbG.

To explore whether McbG regulated the transcription of mcbG itself, the promoter of the mcbG was analyzed (Fig. 7A). The cells of strain XWY-1 were incubated with or without 1-naphthol. The transcription levels of mcbG genes were evaluated. The reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) results showed that the transcription level of mcbG increased significantly (4 times) at 1.5 h and then dropped to an extremely low level (Fig. S4). The results of the EMSA revealed that McbG bound to its own promoter. When 1-naphthol was added as the effector, the binding ability of McbG with the promoter was weakened, indicating that McbG might repress its own expression, while 1-naphthol relieved the repression (Fig. 7B). To determine the McbG binding site, the different, partially overlapping subfragments F1, F2, and F3, were used for the EMSA (Fig. 7C). The F1 subfragment was completely shifted after incubation with McbG (200 nM), whereas subfragments F2 and F3 were not (Fig. 7D). To precisely define the binding region, the subfragments of a and b from F1 were used for the EMSA (Fig. 7E). Only subfragment a, which contained a 25-bp motif (5′-CCTCCAACAATATTGATATATTTTA-3′) was shifted in the presence of McbG (Fig. 7E). These results indicate that this motif plays a key role in promoter binding of McbG.

FIG 7.

(A) DNA elements in the promoter of mcbG. The −35 and −10 boxes are shown in boxes, and the TSS is shown by an arrow. The McbG-binding site is indicated by blue sequence. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays on the binding of McbG to the mcbG promoter. Each lane contains 20 ng of DNA probe. The first 7 lanes show samples incubated without 1-naphthol, and the next 7 lanes show samples incubated with 0.05 mM 1-naphthol. The concentrations of McbG, increasing from left to right, are shown above the lanes. The control DNA was a 200-bp fragment that was amplified from the mcbC gene. (C) Schematic diagram of the mcbG promoter-mcbG intergenic region and the DNA subfragments used to determine the McbG binding site. The locations of fragments used in the EMSAs are shown below. The sequence at the top shows the McbG binding site. (D and E) EMSAs of subfragments F1, F2, and F3 (D) and a and b (E) with purified McbG. The lanes contain the following: the DNA fragment (20 ng) alone (−) and the DNA fragment (20 ng) with McbG (200 nM) (+).

DISCUSSION

McbG, a LysR family transcriptional activator, was identified in this study. The knockout of mcbG caused a loss of 1-naphthol degradation ability in strain XWY-1 (Fig. S2). The qRT-PCR results also revealed no significant differences in the transcription of each gene in the mcbBCDEF cluster in the cells of the knockout strain MT in cultures with and without induction of 1-naphthol (Fig. 4). These results indicate that McbG is a regulatory protein that is involved in the degradation of 1-naphthol and activates the transcription of mcbBCDEF. The results of the EMSA showed that McbG binds to the promoter of mcbBCDEF. Furthermore, upon addition of 1-naphthol, McbG binds to the promoter DNA even at low concentrations down to 30 nM (Fig. 5A). Effector assays using plasmid pME6522-Pmcb in the mutant strain XWY-1 ΔmcbC also showed that the activity of β-galactosidase in the presence of 1-naphthol was significantly higher than in its absence (Fig. 5B), indicating that the effector of McbG is 1-naphthol and not any of its follow-up products.

McbG was found to share similarity with LysR transcription regulators (Fig. S1). Interestingly, LysR-type regulators, including McbG, are involved in the degradation of pollutants in bacteria (22). Examples of this family include CatR, involved in the degradation of catechol in Pseudomonas putida (23), PnpR and PnpM of Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3, involved in the degradation of para-nitrophenol (24, 25), PcpR, involved in the degradation of pentachlorophenol in Sphingobium chlorophenolicum ATCC 39723 (26), and NagR, involved in the degradation of gentisate in Ralstonia sp. strain U2 (27). In addition, the binding of McbG to mcbBCDEF promoter DNA was effector independent (Fig. 5A). This phenomenon is characteristic of LysR-type transcriptional regulators (28).

The binding sites of LysR family transcriptional regulators were initially reported in Rhizobium spp., and a specific palindromic sequence, ATC-N9-GAT, was identified. This sequence is located upstream of the nod gene between 75 and 20 bp and is known as Nod-box (29). The LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) box containing T-N11-A at the ribosome binding site was originally discovered in Pseudomonas putida PRS3026 (30). This structure is present in LysR family regulators, including DbdR, involved in the anaerobic degradation of 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate in Thauera aromatica AR-1 (31), BenM, which catalyzes degradation of benzoate in Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1 (32), and DntR of Burkholderia sp. strain DNT, which is involved in the degradation of 2,4-dinitrotoluene (33). An LTTR box (T-N11-A) was also found in the McbG binding site, concurrent with a specific palindrome sequence, 5′-TATCGATA-3′, inside the box. This short palindromic sequence of T-N6-A at the McbG binding site has been proven to be important for binding of the protein to DNA (Fig. 6C). In addition, the amino acid sequences of McbG in strains XWY-1 and C5pp shared 100% identity, and the binding site of McbG in the mcbBCDEF promoter sequence area of strain XWY-1 is also present in the mcbBCDEF promoter sequence area of strain C5pp (Fig. S5). Therefore, we speculate that the regulation mechanism of McbG is the same in these two strains.

In this study, it was also found that McbG regulated itself. This self-regulation phenomenon is common in the LysR-type regulator family. IlvY activated the expression of acetohydroxy-acid isomeroreductase gene ilvC in E. coli and Salmonella spp. and negatively regulated it by itself (34, 35). The CidR involved in regulating the transcription of the cidABC gene cluster responsible for cell death in Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus anthracis also has its own negative regulation (36, 37). The GltC that regulates the expression of the glutamate synthase gene gltAB in B. subtilis can also repress its own expression (38). In strain XWY-1, the transcription level of mcbG was significantly upregulated in the presence of 1-naphthol (Fig. S4), indicating that 1-naphthol induced the transcription of mcbG. The EMSA results showed that McbG can bind to its own promoter, while the addition of 1-naphthol weakens this binding (Fig. 7B). This result suggested the McbG may mediate the transcription of mcbG.

In strain XWY-1, mcbABCDEF is responsible for the upstream pathway of the degradation of carbaryl (from carbaryl to salicylate), with the mcbA gene being constitutively expressed (20). The present study proved that mcbBCDEF is a transcriptional unit and that McbG is its activator. To test whether McbG is involved in the regulation of mcbIJKL and mcbOPQ, which are responsible for midstream and downstream pathways of carbaryl metabolism, the transcription of mcbBCDEF, mcbIJKL, and mcbOPQ was analyzed in strains XWY-1, MT, and MTC. The results showed that the transcription of the genes in the mcbBCDEF, mcbIJKL, and mcbOPQ clusters was not significantly different in strain MT with or without the induction of 1-naphthol (Fig. 4, Fig. S6A). When salicylate was used as an inducer, the transcription of the genes in the mcbBCDEF cluster was not significantly altered in strain MT. However, transcription of the mcbIJKL and mcbOPQ gene clusters was similar to that of strain XWY-1 and the complemented strain MTC (Fig. S6B), indicating that salicylate can be further degraded as a substrate in the midstream and downstream pathways, thus triggering transcription of the mcbIJKL and mcbOPQ gene clusters. These results indicate that mcbG is a transcriptional activator of the mcbBCDEF cluster but is not responsible for the regulation of the mcbIJKL and mcbOPQ gene clusters of carbaryl metabolism. Therefore, further studies are needed to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of the midstream and downstream pathways of the carbaryl metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and media.

1-Naphthol (98% purity), purchased from Shenzhen Sendi Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shenzhen, China), was prepared as a 0.4 g liter−1 stock solution in water and was sterilized by membrane filtration (pore size, 0.22 μm). MSM consisted of the following components (g liter−1): 1.0 NH4NO3, 1.0 NaCl, 1.5 K2HPO4, 0.5 KH2PO4, and 0.2 MgSO4·7H2O, pH 7.0; the carbon source was added as required. Glucose medium (GM) was MSM supplemented with 1% glucose (wt/vol) as the sole carbon source. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth consisted of the following components (g liter−1): 10.0 tryptone, 5.0 yeast extract, and 10.0 NaCl at pH 7.0.

Bacterial strains, oligonucleotides, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the oligonucleotide primer sequences are listed in Table 2. Strain XWY-1 (deposited in the China Center for Type Culture Collection [CCTCC]; accession number AB2020137) is a carbaryl-degrading strain that was previously isolated in our lab. E. coli strains were used for recombinant DNA procedures and were grown at 37°C in LB medium or LB medium supplemented with antibiotics as described. Other bacterial strains were grown aerobically at 30°C in LB broth or LB agar. Expression of 1-naphthol metabolic genes was induced in MSM supplemented with 0.1 mM 1-naphthol. Chloramphenicol (Cm) and tetracycline (Tc) were used at 30 μg ml−1, kanamycin (Km) and gentamicin (Gm) were used at 50 μg ml−1, and ampicillin (Amp) was used at 100 μg ml−1. Growth of cells was evaluated by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F−recA1 endA1 thi-1 supE44 relA1 deoRΔ(lacZYA-argF)U169 80dlacZΔM15 | TaKaRa |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) gal dcm lacY1 (DE3) | TaKaRa |

| Pseudomonas sp. strains | ||

| XWY-1 | Carbaryl degradation strain, Ampr; Cmr | Lab stock |

| MT | mcbG-disrupted mutant from strain XWY-1; Ampr; Kmr | This study |

| MTC | MT harboring pBmcbG; Gmr; Ampr; Kmr | This study |

| XWY-1 ΔmcbC | mcbC-disrupted mutant from strain XWY-1; Ampr; Gmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD19-T | TA cloning vector, Ampr | TaKaRa |

| F1-19T | 300-bp fragment, upstream of TSS of mcbBCDEF, directionally cloned into pMD19-T, Ampr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Broad-host-range cloning vector, Kmr | 39 |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Broad-host-range cloning vector, Gmr | 39 |

| pEX18Gm | Gene knockout vector, oriT, sacB, Gmr | 40 |

| pEXmcbG | mcbG gene knockout vector containing upstream and downstream homologous regions of mcbG, Gmr | This study |

| pBmcbG | pBBR1MCS-5 harboring mcbG, Kmr | This study |

| pET-29a(+) | Expression vector, Kmr | Novagen |

| pET-mcbG | pET-29a(+) harboring mcbG, Kmr | This study |

| pME6522 | pVS1-p15A E. coli-Pseudomonas shuttle vector for transcriptional lacZ fusion and promoter probing, Tcr | 21 |

| pME6522-Pmcb | 300-bp fragment, upstream of TSS of mcbBCDEF, directionally cloned into pME6522, Tcr | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Gmr, gentamicin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Function and oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′→3′) a |

|---|---|

| Gene disruption | |

| McbGupF | TTCCCGTTGAATATGGCTCATCAGATCATCTTTAAAAATACCCCTCAGTTG |

| McbGupR | TATGACCATGATTACGAATTCCAGTTCAGCCTGCTGTTCATT |

| McbGdownF | CAGGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCGCGCGACATGCTTGAACT |

| McbGdownR | ATGCTCGATGAGTTTTTCTAAGAGGGCACGGACCTTATATCG |

| McbGkF | CGATATAAGGTCCGTGCCCTCCGATATAAGGTCCGTGCCCTC |

| McbGkR | GGTATTTTTAAAGATGATCTGGGTATTTTTAAAGATGATCTG |

| McbGhbF | CGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCGACGACGCAGGCAGCAC |

| McbGhbR | GATAAGCTTGATATCGAATTCTCAGACCTTCCTTAAGGTATCTCTTAACC |

| McbCDQ-F | CAGGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCCGGGAAAAAATCCCAGC |

| McbCDQ-R | TATGACCATGATTACGAATTCGAGTTCGAAGGAAAAATGGGAG |

| Transcriptional unit analysis | |

| McbAB-F | TAACTATTTTGTGAGTTGGTTGG |

| McbAB-R | CCTGCATTACCTTCACATC |

| McbBC-F | GTGCGTCCAGATCGTTTTGTG |

| McbBC-R | GACACAGCCCAATCAACCCCA |

| McbCD-F | CCAGCAATCGAGAGCTTCCTG |

| McbCD-R | GACTGCTCGATTTCCAGAACTTC |

| McbDE-F | GAGAGGTGATGAGGTTGGGTG |

| McbDE-R | GGATGAACCTCAAGTCAATTCGAT |

| McbEF-F | CTTCCTGTGTCATCGGTCCTA |

| McbEF-R | GCAACATCGCGATAAAACTGG |

| McbFR-F | CGTCGACACAGCAGTGCTATG |

| McbFR-R | GCGTGAGTCTTCGGACTAGTC |

| qRT-PCR analysis | |

| 16Srt-F | GTAGATATAGGAAGGAACACCAGTGG |

| 16Srt-R | TTAACCTTGCGGCCGTACTC |

| mcbBrt-F | GGCTTGGGATCAAAAGGGATG |

| mcbBrt-R | GCCGAATATTGCAACCCGTTC |

| mcbCrt-F | GCCGATATTGCTGGATGTTGC |

| mcbCrt-R | ACCAAGCTACGAGCACCAT |

| mcbDrt-F | CCAGCAATCGAGAGCTTCCTG |

| mcbDrt-R | CGCCCCTTAGGAGACTCAATG |

| mcbErt-F | GAGAGGTGATGAGGTTGGGTG |

| mcbErt-R | GCTCGAAGCCAAACGCAAATC |

| mcbFrt-F | GGCGAATGAAGTTGGTTCCTC |

| mcbFrt-R | GCGTGAGTCTTCGGACTAGTC |

| mcbGrt-F | TATCTGGATGTGCTGTTTCAGCC |

| mcbGrt-R | AGGAACCTCTGCCAAAGAGCTA |

| mcbIrt-F | TTCAAAGCCTCGACCATGGC |

| mcbIrt-R | TGTTGTCGATTGTGCGAGGTG |

| mcbJrt-F | ATTGACCTTGCCGTCCTGC |

| mcbJrt-R | CTTGAGCGCCTGTTTTACTCAG |

| mcbKrt-F | AAGCTTAAGCCCTTCCGGAG |

| mcbKrt-R | AGAACTATGAGCGCGGGT |

| mcbLrt-F | TCACCGGGTAGGTCCGGA |

| mcbLrt-R | ATGGGTCGATGTTGCACC |

| mcbOrt-F | CCCGATGGTGCGCTTCTT |

| mcbOrt-R | GTCTTGGCACAGCAGGGTTT |

| mcbPrt-F | GACTACCCGGTGGAGACCAG |

| mcbPrt-R | GTCGAAGGCCTTGCCCAG |

| mcbQrt-F | CGCCCAGCTCCCGTTGTA |

| mcbQrt-R | GTAGTCTTCAAGCTCGCAGCC |

| Gene expression | |

| mcbGbdF | TCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGGACCTTCCTTAAGGTATCTCT |

| mcbGbdR | TAAGAAGGAGATATACATATGATGGGCTATAAAAACAGATCC |

| DNA affinity and EMSA | |

| mcb-F | CTGTAGGGCAGCCCAGCG |

| mcb-R | GCAACACACCCATGCACCAC |

| mcbC-F | GCCGATATTGCTGGATGTTGC |

| mcbC-R | CCTTCGAACTCAAACCCGAGG |

| JHQ1-F | ACCAGCCGAAGCATCAACTTG |

| JHQ1-R | GCAGGCAGTGTTTTTCAGCCCTGTTGGTATTGAAAAGCACTGTTACTCA |

| JHQ2-F | CAGTGCTTTTCAATACCAACAGGGCTGAAAAACACTGCCTG |

| JHQ2-R | TCGAGACACAGGCATGGTGT |

| DTB-1R | GTGTTTTTCAGCCCCCTTTAAGCATTGGTATTTTAACCCTGTTGGTATT |

| DTB-2R | AATACCAACAGGGTTAAAATACCAATGCTTA |

| AAGGGGGCTGAAAAACACT | |

| DTB-3R | GGGGCAGGCAGTGTTTTTCAGCCCAGGTAAGGTAAGGTAATTATCGATA |

| DTB-4R | ACATATCGATAATTACCTTACCTTACCTGGGCTGAAAAACACTGCCTGCCC |

| mcbG-F | TGCCACCTCCAACAATATTGATATATT |

| mcbG-R | CGAAACCGTGTTTGAATACATCG |

| GF1-F | CCTCCAACAATATTGATATATTTTAG |

| GF1-R | CACGGTACCAGTGAAGGGC |

| GF2-F | GGCTATTTCCGCGCTACTG |

| GF2-R | AGAGGTCTCCGGGGCCCG |

| GF3-F | TGGGCTGCTGTCCGCATTA |

| GF3-R | AATCGACTACAACCGCCAG |

| Ga-R | GCTTATTGGACGAAACGAAGGAAA |

| Gb-F | GAACAGCTCTAAAGTAGCCCCG |

| Gb-R | TGACGCAGGGGACCTTCG |

| Reporter plasmid construction | |

| mcb-bF | CGGAATTCCTGTAGGGCAGCCCAGCG |

| mcb-bR | AACTGCAGGCAACACACCCATGCACCAC |

| 5′ RACE | |

| SP1 | CCGGTAAAATTAACCCTCCGC |

| SP2 | CGATTAGCGCGTGAGTCTTC |

| SP3 | GGCTTGTCGGTCGGAATAGTC |

Restriction sites are in boldface, and nucleotide sequences that are different from the template are underlined.

Determination of the transcription start sites.

The transcription start sites of the mcbBCDEF cluster were determined using a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system (TIANDZ; Beijing Tianenze Gene Technology Co. Ltd.). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the primer SP1 (Table 2), and tailing of the cDNA was performed using terminal transferase and dTTP. The deoxyribosylthymine (dT)-tailed cDNA was amplified using the abridged anchor primer (APP) and SP2 (Table 2). This PCR product was then used as a template for a nested PCR with an abridged universal amplification primer (AAP) and primer SP3 (Table 2) and cloned into a pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa, Japan) for sequencing.

Genetic disruption and complementation.

Two DNA fragments corresponding to 1,000-bp upstream and downstream flanking regions of the mcbG gene were amplified using primer pairs McbGupF/McbGupR and McbGdownF/McbGdownR, respectively. They were linked to a kanamycin resistance gene that was amplified from plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 (39) with the primer pair McbGkF/McbGkR by overlap extension PCR, and the resulting fragment was cloned into pEX18-Gm (40), yielding pEXmcbG. pEXmcbG was then electroporated into strain XWY-1. Single-crossover mutants were screened on LB agar containing 50 μg ml−1 of kanamycin and 50 μg ml−1 of gentamicin. After verification, a single-crossover mutant was cultured until the OD600 reached approximately 0.2, and double-crossover mutants were selected on LB agar containing 50 μg ml−1 of kanamycin and 20% sucrose. Both single- and double-crossover mutants were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing. The double-crossover mutant was designated MT. The mcbC knockout mutant XWY-1 ΔmcbC was obtained similarly.

The mcbG gene was amplified with the primer pair McbGhbF/McbGhbR inserted into pBBR1MCS-5 (39) to generate pBmcbG, which was electroporated into MT to obtain the mcbG-complemented strain MTC.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Strains XWY-1, MT, and MTC were cultured in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics to an OD600 of 0.6. The cells were then harvested and washed twice with MSM. Expression of 1-naphthol degradation genes in washed cells was induced in MSM (the final cell density corresponded to an OD600 of 2.0) at 30°C for 3 h in the presence of 0.1 mM 1-naphthol. A culture grown in MSM with 0.1 mM glucose was used as the control. Total RNA was extracted using total a RNA extraction kit (TaKaRa, China), and genomic DNA (gDNA) in the preparation was digested with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, China) at 42°C for 2 min. Reverse transcription was then performed with 1 μg of gDNA-free RNA using random primers. The cDNA was synthesized by incubation at 37°C for 15 min using PrimeScript reverse transcriptase (RTase, TaKaRa), and the reaction was stopped by heating the mixture at 85°C for 5 s. Samples were diluted 100-fold to serve as templates for quantitative PCR (qPCR). qPCR was performed in an Applied Biosystems 6 real-time PCR system using a SYBR premix Ex Taq RT-PCR kit (TliRNaseH Plus; TaKaRa, China) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The 16S rRNA gene was used as an internal standard, and relative expression was quantified using the 2–ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method.

Reporter plasmid construction and β-galactosidase activity assay.

The PMcb, a 300-bp fragment upstream of the TSS of mcbBCDEF, was amplified by PCR from strain XWY-1 using the oligonucleotide pair mcb-bF/mcb-bR (Table 2). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and PstI, followed by ligation into pME6522 to generate pME6522-PMcb carrying the PMcb-lacZ transcriptional fusion (Table 1).

β-Galactosidase activity assays were performed with strain XWY-1 grown in GM or in GM supplemented with 0.1 mM 1-naphthol. β-Galactosidase activity was determined using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as the substrate. The observed activity was normalized to the optical density of the culture at 600 nm and expressed in Miller units (41). One Miller unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze ONPG to produce 1 μmol o-nitrophenol (ONP) per minute. At least three independent cultures from each strain were assayed in each experiment.

Purification of McbG and EMSA.

To determine the function of McbG, the mcbG gene was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), and the protein was purified as described by Ni et al. (42). The mcbG DNA fragment was amplified with the primers mcbGbdF/mcbGbdR, digested with XhoI and NdeI, and inserted into similarly cut pET-29a(+) to produce pET-mcbG. The clones were sequenced to ensure that no mutations were introduced. E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET-mcbG was grown in LB at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.8 and then induced for 12 h by the addition of 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) at 16°C. Cells were then collected, washed, and disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was precipitated using 40% ammonium sulfate, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min. The precipitate was dissolved in Tris-HCl and loaded onto a His-Bind resin. His8-tagged McbG was eluted using 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer with various concentrations of imidazole (0 mM, 25 mM, 50 mM, 300 mM, and 500 mM). Fractions containing McbG were pooled and filtered using a 10-kDa Amicon ultrafiltration tube. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method. The molecular mass of the purified enzymes was estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

For the EMSA, a nonradioactive strategy was implemented according to the method described by De la Cruz et al. (43). The wild-type 300-bp promoter DNA probe of the mcbBCDEF cluster was amplified using mcb-F/mcb-R; the 300-bp sequence containing the promoter area of mcbG was amplified using mcbG-F/mcbG-R; a 200-bp region of mcbC used as the negative control was amplified using the primer mcbC-F/mcbC-R. Nucleotides in the mutated promoter DNA were introduced by primers (listed in Table 2) and were amplified using overlapping extension PCR. The mcbBCDEF fragment with the deleted 25-bp motif sequence (CCTTTAAGCATTGGTATTATCGATA) was amplified with overlap extension PCR using primers JHQ1-F/JHQ1-R and JHQ2-F/JHQ2-R. The mcbG promoter subfragments F1, F2, F3, a, and b were amplified using primers GF1-F/GF1-R, GF2-F/GF2-R, GF3-F/GF3-R, GF1-F/Ga-R, and Gb-F/Gb-R (listed in Table 2). Approximately 20 ng of a promoter probe was mixed with increasing concentrations of purified McbG in a binding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM KCl, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 250 μg ml−1 EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). A nonspecific DNA sequence (a sequence in mcbC) was used as the negative control. The effects of 1-naphthol on the binding of McbG to the promoter probes were evaluated by adding 0.05 mM 1-naphthol to the reaction system. The mixture was incubated at 25°C for 30 min and then separated on a 5% (vol/vol) native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-glycine-EDTA. The DNA and DNA-protein complexes were visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

DNase I footprinting assay.

For preparation of fluorescent 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled probes, the promoter region was amplified by PCR using 2× TOLO HIFI DNA polymerase premix (TOLO Biotech, Shanghai, China) from the plasmid F1-19T using the primers M13F(FAM) and M13R. The FAM-labeled probes were purified using the Wizard SV gel and PCR clean-up system (Promega, USA) and were quantified using NanoDrop 2000C (Thermo, USA).

DNase I footprinting assays were performed similarly to the description by Wang et al. (44). For each assay, 350-ng probes were incubated with different concentrations of McbG in a total volume of 40 μl. After incubation for 30 min at 25°C, a 10-μl solution containing about 0.015 units DNase I (Promega) and 100 nmol freshly prepared CaCl2 was added and incubated at 37°C for 1 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 140 μl DNase I stop solution (200 mM unbuffered sodium acetate, 30 mM EDTA, and 0.15% SDS). Samples were first extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) and then precipitated with absolute ethanol. The pellets obtained were dissolved in 30 μl Milli-Q water. Preparation of the DNA ladder, electrophoresis, and data analysis were as described earlier (44), except that the GeneScan-LIZ600 size standard (Applied Biosystems) was used.

Analytical techniques.

To analyze 1-naphthol, the culture samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were filtered through 0.22-μm-pore-size filters before being subjected to analysis with a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (UltiMate 3000; Dionex, USA) equipped with a C18 reverse-phase column (4.6 by 250 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of methanol-water-acetic acid (75:25:0.5, vol/vol/vol) at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1 at 40ºC for 10 min. Column elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 230 nm.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970102, 31670112), and the Opening Fund of Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Food Quality and Safety-State Key Laboratory Cultivation Base (028074911709).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klaassen CD. 2008. Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Division, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan RE, Duggan MB. 1973. Pesticide residues in food, p 334–364. In Edwards C (ed), Environmental pollution by pesticides. Springer, Boston, MA. 10.1007/978-1-4615-8942-6_10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guzik U, Hupert-Kocurek K, Marchlewicz A, Wojcieszyńska D. 2014. Enhancement of biodegradation potential of catechol 1,2-dioxygenase through its immobilization in calcium alginate gel. Electron J Biotechnol 17:83–88. 10.1016/j.ejbt.2014.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rousidou K, Chanika E, Georgiadou D, Soueref E, Katsarou D, Kolovos P, Ntougias S, Tourna M, Tzortzakakis EA, Karpouzas DG. 2016. Isolation of oxamyl-degrading bacteria and identification of cehA as a novel oxamyl hydrolase gene. Front Microbiol 7:616. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karishma M, Trivedi VD, Choudhary A, Mhatre A, Kambli P, Desai J, Phale PS. 2005. Analysis of preference for carbon source utilization among three strains of aromatic compounds degrading Pseudomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett 362:fnv139. 10.1093/femsle/fnv139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Öztürk B, Ghequire M, Nguyen TP, De MR, Wattiez R, Springael D. 2016. Expanded insecticide catabolic activity gained by a single nucleotide substitution in a bacterial carbamate hydrolase gene. Environ Microbiol 18:4878–4887. 10.1111/1462-2920.13409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swetha VP, Phale PS. 2005. Metabolism of carbaryl via 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene by soil isolates Pseudomonas sp. strains C4, C5, and C6. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5951–5956. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.5951-5956.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan QX, Wang YX, Li SP, Li WJ, Hong Q. 2010. Sphingobium qiguonii sp. nov., a carbaryl-degrading bacterium isolated from a wastewater treatment system. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:2724–2728. 10.1099/ijs.0.020362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan QX, Hong Q, Han P, Dong XJ, Shen YJ, Li SP. 2007. Isolation and characterization of a carbofuran-degrading strain Novosphingobium sp. FND-3. FEMS Microbiol Lett 271:207–213. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen TPO, Helbling DE, Bers K, Fida TT, Wattiez R, Kohler HP, Springael D, De Mot R. 2014. Genetic and metabolic analysis of the carbofuran catabolic pathway in Novosphingobium sp. KN65.2. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:8235–8252. 10.1007/s00253-014-5858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto M, Fukui M, Hayano K, Hayatsu M. 2002. Nucleotide sequence and genetic structure of a novel carbaryl hydrolase gene (cehA) from Rhizobium sp. strain AC100. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:1220–1227. 10.1128/aem.68.3.1220-1227.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia YL. 2012. Isolation, characterization of carbaryl-degrading strains and cloning of the cehA gene. Master’s thesis. Nanjing Agricultural University, Jiangsu, China. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H, Kim DU, Lee H, Yun J, Ka JO. 2017. Syntrophic biodegradation of propoxur by Pseudaminobacter sp. SP1a and Nocardioides sp. SP1b isolated from agricultural soil. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 118:1–9. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkin M, Day M. 1986. The metabolism of carbaryl by three bacterial isolates, Pseudomonas spp. (NCIB 12042 & 12043) and Rhodococcus sp. (NCIB 12038) from garden soil. J Appl Bacteriol 60:233–242. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomasek PH, Karns JS. 1989. Cloning of a carbofuran hydrolase gene from Achromobacter sp. strain WM111 and its expression in Gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 171:4038–4044. 10.1128/jb.171.7.4038-4044.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayatsu M, Mizutani A, Hashimoto M, Sato K, Hayano K. 2001. Purification and characterization of carbaryl hydrolase from Arthrobacter sp. RC100. FEMS Microbiol Lett 201:99–103. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu SJ, Wang H, Jiang WK, Yang ZG, Zhou YD, He J, Qiu JG, Hong Q. 2019. Genome analysis of carbaryl-degrading strain Pseudomonas putida XWY-1. Curr Microbiol 76:927–929. 10.1007/s00284-019-01637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivedi VD, Jangir PK, Sharma R, Phale PS. 2016. Insights into functional and evolutionary analysis of carbaryl metabolic pathway from Pseudomonas sp. strain C5pp. Sci Rep 6:38430. 10.1038/srep38430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shetty D, Trivedi VD, Varunjikar M, Phale PS. 2017. Compartmentalization of the carbaryl degradation pathway: molecular characterization of inducible periplasmic carbaryl hydrolase from pseudomonas spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02115-17. 10.1128/AEM.02115-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu SJ. 2018. Molecular mechanism of carbaryl degradation by Pseudomonas sp. XWY-1. PhD thesis. Nanjing Agricultural University, Jiangsu, China. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang LJ, Tang HZ, Yu H, Yao YX, Xu P. 2014. An unusual repressor controls the expression of a crucial nicotine-degrading gene cluster in Pseudomonas putida S16. Mol Microbiol 91:1252–1269. 10.1111/mmi.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maddocks SE, Oyston PCF. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology (Reading) 154:3609–3623. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chugani SA, Parsek MR, Chakrabarty AM. 1998. Transcriptional repression mediated by LysR-type regulator CatR bound at multiple binding sites. J Bacteriol 180:2367–2372. 10.1128/JB.180.9.2367-2372.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang WM, Zhang JJ, Jiang X, Chao H, Zhou NY. 2015. Transcriptional activation of multiple operons involved in para-nitrophenol degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:220–230. 10.1128/AEM.02720-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JP, Zhang WM, Chao HJ, Zhou NY. 2017. PnpM, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator activates the hydroquinone pathway in para-nitrophenol degradation in Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. Front Microbiol 8:1714. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orser CS, Lange CC. 1994. Molecular analysis of pentachlorophenol degradation. Biodegradation 5:277–288. 10.1007/BF00696465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou NY, Fuenmayor SL, Williams PA. 2001. nag genes of Ralstonia (Formerly Pseudomonas) sp. strain U2 encoding enzymes for gentisate catabolism. J Bacteriol 183:700–708. 10.1128/JB.183.2.700-708.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tropel D, van der Meer JR. 2004. Bacterial transcriptional regulators for degradation pathways of aromatic compounds. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68:474–500. 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.474-500.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goethals K, Van Montagu M, Hoslters M. 1992. Conserved motifs in a divergent nod box of Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 reveal a common structure in promoters regulated by LysR-type proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:1646–1650. 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsek MR, McFall SM, Shinabarger DL, Chakrabarty AM. 1994. Interaction of two LysR-type regulatory proteins CatR and ClcR with heterologous promoters: functional and evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:12393–12397. 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pacheco-Sánchez D, Molina-Fuentes A, Marín P, Díaz-Romero A, Marqués S. 2019. DbdR, a new member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, coordinately controls four promoters in the Thauera aromatica AR-1 3,5-dihydroxybenzoate anaerobic degradation pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e02295-18. 10.1128/AEM.02295-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alanazi AM, Neidle EL, Momany C. 2013. The DNA-binding domain of BenM reveals the structural basis for the recognition of a T-N11-A sequence motif by LysR-type transcriptional regulators. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:1995–2007. 10.1107/S0907444913017320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devesse L, Smirnova I, Lönneborg R, Kapp U, Brzezinski P, Leonard GA, Dian C. 2011. Crystal structures of DntR inducer binding domains in complex with salicylate offer insights into the activation of LysR-type transcriptional regulators. Mol Microbiol 81:354–367. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazey DL, Burns RO. 1980. Gene ilvY of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 142:1015–1018. 10.1128/JB.142.3.1015-1018.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee KY, Opel M, Ito E, Hung S, Arfin SM, Hatfield GW. 1999. Transcriptional coupling between the divergent promoters of a prototypic LysR-type regulatory system, the ilvYC operon of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:14294–14299. 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang SJ, Rice KC, Brown RJ, Patton TG, Liou LE, Park YH, Bayles KW. 2005. A LysR-type regulator, CidR, is required for induction of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC operon. J Bacteriol 187:5893–5900. 10.1128/JB.187.17.5893-5900.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn JS, Chandramohan L, Liou LE, Bayles KW. 2006. Characterization of CidR-mediated regulation in Bacillus anthracis reveals a previously undetected role of S-layer proteins as murein hydrolases. Mol Microbiol 62:1158–1169. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picossi S, Belitsky BR, Sonenshein AL. 2007. Molecular mechanism of the regulation of Bacillus subtilis gltAB expression by GltC. J Mol Biol 365:1298–1313. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoang TT, Karkhoff SRR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni HY, Wang F, Li N, Yao L, Dai C, He Q, He J, Hong Q. 2016. Pendimethalin nitroreductase is responsible for the initial pendimethalin degradation step in Bacillus subtilis Y3. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:7052–7062. 10.1128/AEM.01771-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De la Cruz MA, Fernandez MM, Guadarrama C, Flores VM, Bustamante VH, Vazquez A, Calva E. 2007. LeuO antagonizes H-NS and StpA-dependent repression in Salmonella enterica ompS1. Mol Microbiol 66:727–743. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Cen X, Zhao G, Wang J. 2012. Characterization of a new GlnR binding box in the promoter of amtB in Streptomyces coelicolor inferred a PhoP/GlnR competitive binding mechanism for transcriptional regulation of amtB. J Bacteriol 194:5237–5244. 10.1128/JB.00989-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.