The thermophilic bacillus Geobacillus stearothermophilus is a predominant spoilage bacterium in milk powder manufacturing plants. If its numbers exceed the accepted levels, this may incur financial loses by lowering the price of the end product.

KEYWORDS: thermophilic bacteria, Geobacillus stearothermophilus, spore formation, temperature, total dissolved solid concentration

ABSTRACT

Geobacillus species are important contaminants in the dairy industry, and their presence is often considered an indicator of poor plant hygiene with the potential to cause spoilage. They can form heat-resistant spores that adhere to surfaces of processing equipment and germinate to form biofilms. Therefore, strategies aimed toward preventing or controlling biofilm formation in the dairy industry are desirable. In this study, we demonstrated that the preferred temperature for biofilm and spore formation among Geobacillus stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was 65°C. Increasing the total dissolved milk solid concentration to 20% (wt/vol) caused an apparent delay in the onset of biofilm and spore formation to detectable concentrations among all the strains at 55°C. Compared to the onset time of the biofilm formation of A1 in 10% (wt/vol) reconstituted skim milk, addition of milk protein (whey protein and sodium caseinate) caused an apparent delay in the onset of biofilm formation to detectable concentrations by an average of 10 h at 55°C. This study proposes that temperature and total dissolved solid concentration have a cumulative effect on biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980. In addition, the findings from this study may indicate that preconditioning of stainless steel surfaces with adsorbed milk proteins may delay the onset of biofilm and spore formation by thermophilic bacteria during milk powder manufacture.

IMPORTANCE The thermophilic bacillus Geobacillus stearothermophilus is a predominant spoilage bacterium in milk powder manufacturing plants. If its numbers exceed the accepted levels, financial losses may be incurred because of the need to lower the price of the end product. Furthermore, G. stearothermophilus bacilli can form heat-resistant spores which adhere to processing surfaces and can germinate to form biofilms. Previously conducted research had highlighted the variation in the spore and biofilm formation among three specific strains of G. stearothermophilus isolated from a milk powder manufacturing plant in New Zealand. The significance of our research is in demonstrating the effects of two abiotic factors, namely, temperature and total dissolved solid concentration, on biofilm and spore formation by these three dairy isolates, leading to modifications in the thermal processing steps aimed toward controlling biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus in the dairy industry.

INTRODUCTION

Geobacillus stearothermophilus (formerly known as Bacillus stearothermophilus) is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium that is capable of growing at temperatures of 55 to 65°C (1). G. stearothermophilus is a common contaminant in the food industry, particularly in milk powder plants, where temperatures (40 to 65°C) suitable for their growth prevail (2). Although G. stearothermophilus is not pathogenic, the presence of its spores in the dairy industry is an indicator of poor plant hygiene, with the potential for spoilage through acid and enzyme production (3). The major thermophilic spore contaminants in whole milk power manufacture are Anoxybacillus flavithermus and G. stearothermophilus (2). The sporulation of G. stearothermophilus is confined to the evaporator during the production of whole milk powder (2). The growth of G. stearothermophilus during milk powder manufacturing is believed to occur as biofilms within the sections of the evaporator (4).The microorganism is capable of forming vegetative cells and heat-resistant spores within the biofilm (4). Upon maturation of the biofilm, the spores are released into the milk and contaminate the end product (5).

In milk powder manufacture, fresh milk flows through a plate heat exchanger which is maintained at a temperature between 50 and 65°C before passing through an evaporator (2). As preheated milk passes through the stages of the evaporator, physical parameters, i.e., temperature and total dissolved solid concentration, vary. Biofilm and spore formation is affected by several factors (6–9). The temperature gradient within the evaporator can vary between 40 and 70°C (10). Fresh milk during milk powder manufacture is usually concentrated from an initial solid content of 9 to 13% to a final concentration of 40 to 50% during evaporation before being pumped into the drier (11). A previous study discussing the effect of incubation temperature on the formation of spores in A. flavithermus biofilms indicated that spores were formed at 55 and 60°C but not at 48°C (9). The lack of thermophilic growth in passes 3, 4, and 5 of the evaporator is related to the increase in the total dissolved solids (2). The development of G. stearothermophilus biofilm on a stainless steel surface in the presence of milk was studied previously (12); however, the role of temperature and the total dissolved solid concentration in spore formation has not been studied.

The objective of this study was to determine the effects of two key variables, incubation temperature and the total dissolved solid concentration, on biofilm and spore formation by dairy isolates of G. stearothermophilus. The outcome of this study will be useful in the design of thermal processing steps in milk powder manufacturing plants aimed toward controlling biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus in the dairy industry.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of temperature on biofilm and spore formation.

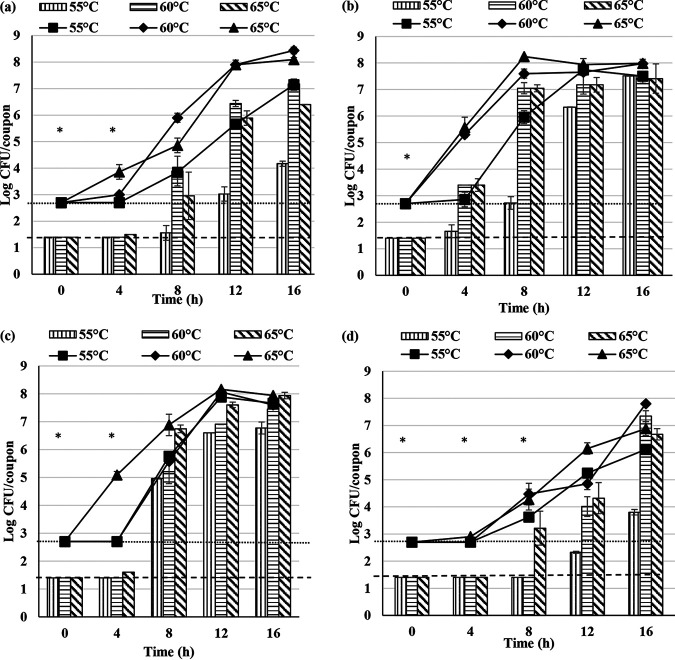

To determine the spore forming capacity of G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980, a continuous-flow CDC reactor was operated over a period of 16 h at three different temperatures, 55, 60, and 65°C. These temperatures were specifically chosen since they lie within the optimum growth temperature range of these bacteria. Biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 on stainless steel coupons is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Total viable cells and spores obtained from the biofilms of G. stearothermophilus A1 (a), D1 (b), P3 (c), and ATCC 12980 (d) in 10% (wt/vol) RSM. The bar graph represents the total spores and line graph represents total viable cells attached to the stainless steel coupon. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates. Dotted lines represent minimum detection limits of 1.4 and 2.7 log CFU/coupon for total spores and total viable cells, respectively. “*” represents one or more observations below the detection limit.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentration of total viable cells and spores per coupon, an apparent delay in the onset of biofilm formation of A1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was observed at 55°C. At 60°C, an apparent delay in the onset of biofilm formation for P3 and ATCC 12980 was observed, whereas such a delay was not observed for A1 and D1. All strains showed delay in the onset of biofilm formation at 65°C. Spore formation among A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was influenced by the incubation temperature. An apparent delay in the spore formation among A1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was observed at 55°C, whereas no delay was observed in D1. At 60°C, an apparent delay in the spore formation among A1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was observed. At 65°C, no delay in the spore formation among the three dairy strains was observed; however, spore formation by ATCC 12980 exhibited an apparent delay of 0 to 4 h.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentrations of total viable cells and spores released into the milk, release of spores among A1, P3, and ATCC 12980 exhibited an apparent delay at 55 and 60°C. At 65°C, the release of spores of P3 and ATCC 12980 exhibited an apparent delay; however, no such delay was observed for A1. D1 showed no delay in the release of spores at 55, 60, and 65°C.

There was a wide variation in the biofilm and spore forming capabilities of G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 at 55, 60, and 65°C in 10% (wt/vol) reconstituted skim milk (RSM). It was previously shown that incubation temperature affects biofilm and spore formation in various bacterial species (13–15). Biofilms of A. flavithermus develop at 48, 55, and 60°C; however, spores develop only at 55 and 60°C and not at 48°C (9). The effect of temperature on the sporulation of Bacillus spp. has been studied, and it has been shown that lower temperatures delay sporulation compared with that at higher temperatures (13). In the present study, the delay in the biofilm and spore formation of the three dairy isolates was unobservable at 65°C in comparison with that at 55 and 60°C, indicating that 65°C is the preferred temperature for biofilm and spore formation among A1, D1, and P3 in 10% RSM. G. stearothermophilus D1 showed no delay in biofilm and spore formation at 55 and 60°C in comparison with that at 65°C in 10% RSM, indicating strain variation among A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 in biofilm and spore formation, and this aligns with the known diversity reported for this species (16).

Spore formation can occur within 11 h in a milk powder manufacturing facility (2); however, in the present study, spore formation among the dairy isolates occurred within 4 h at 65°C in 10% RSM. It is difficult to compare a laboratory biofilm system with a commercial milk powder manufacturing facility. In a milk powder manufacturing industry, the initial contamination arises due to the colonization of processing surfaces by spores present in raw milk that survive pasteurization. Upon attachment, spores undergo germination and biofilm formation before endospores are formed within the biofilm. In this study, vegetative cells in their stationary phase of growth were used as the inoculum, which may shorten the time required for biofilm and spore formation. Freshwater bacteria have shown higher coaggregation during the starved physiological state in the stationary phase (17).

In the present study, on average, spores comprised more than 90% of a 16-h biofilm of A1, D1, and P3 at 65°C in 10% RSM. This is an important observation, given that the average length of a manufacturing cycle in a milk powder manufacturing plant is 16 h (16). In a previous study, it was observed that G. stearothermophilus A1 does not produce spores within the 16-h period (16). In the present study, A1 produced spores as early as 0 to 8 and 0 to 4 h at 60 and 65°C, respectively. This difference in the results may be due to the different biofilm system used.

Effect of total dissolved solid concentration on biofilm and spore formation.

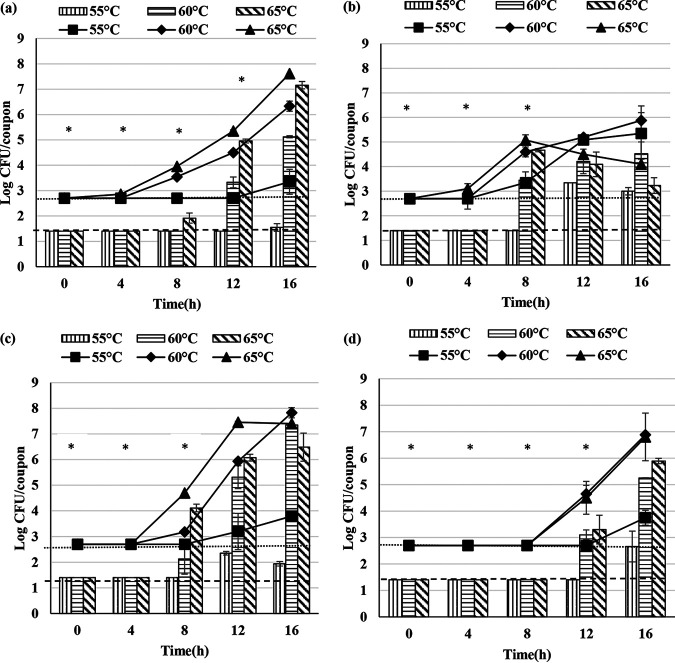

To study the effect of total dissolved solid concentration on biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980, the total viable cells and spores within/released from the biofilm in the presence of 20% (wt/vol) RSM milk were determined and compared with the results obtained with 10% (wt/vol) RSM milk. Biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 on stainless steel coupons is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG 2.

Total viable cells and spores obtained from the biofilms of G. stearothermophilus A1 (a), D1 (b), P3 (c), and ATCC 12980 (d) in 20% (wt/vol) RSM. The bar graph represents the total spores and line graph represents total viable cells attached to the stainless steel coupon. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates. Dotted lines represent minimum detection limits of 1.4 and 2.7 log CFU/coupon for total spore and total viable cells, respectively. “*” represents one or more observations below the detection limit.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentration of total viable cells and spores per coupon, the onset of biofilm formation among A1, D1, and P3 was apparently delayed at 55°C. At 60°C, biofilm formation was apparently delayed for A1 and P3, whereas at 65°C, biofilm formation by P3 was delayed and no such delay was observed for A1 and D1. The onset of biofilm formation in ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 55, 60, and 65°C. Spore formation for A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was influenced by the incubation temperature. The onset of spore formation among A1, D1, and P3 was apparently delayed at 55 and 60°C. At 65°C, spore formation for A1, D1, and P3 was delayed until 0 to 4 h. Spore formation in ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 55, 60, and 65°C.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentrations of total viable cells and spores released into the milk, the release of spores into the milk among A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 55, 60, and 65°C.

Regression analysis of the effects of incubation temperature, incubation time, and total solid concentration on biofilm and spore formation yielded a regression equation and coefficient of regression (R2), which are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Based on the regression analysis, a Pareto chart indicating the standardized effect of individual parameters on the biofilm formation was constructed. It was observed that incubation time is the most influential parameter impacting biofilm formation by A1, P3, and ATCC 12980, whereas the total dissolved solid concentration is the most influential parameter impacting biofilm formation by D1. Spore formation by A1 and ATCC 12980 is most influenced by incubation time, whereas the total dissolved solid concentration is the most influential parameter impacting spore formation by D1 and P3. We predict that the observed difference in the influential parameter impacting biofilm and spore formation might arise due to the strain variation that has been reported previously for this species (16).

TABLE 1.

Regression analysis of the effect of incubation temperature, total dissolved solid concentration, and incubation time on biofilm formation by G. stearothermophilusa

| Strain | Regression equation of the best-fitting model | Adjusted R2 value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Total viable cells/coupon = −8.13 + 0.3809 incubation time – 201.14 total dissolved solid concn + 0.2015 incubation temp | 82.4 |

| D1 | Total viable cells/coupon = −1.16 + 0.932 incubation time − 27.01 total solid concn + 0.0926 incubation temp − 0.0345 incubation time × incubation time | 80.38 |

| P3 | Total viable cells/coupon = −85.2 + 3.665 incubation time − 2.314 total dissolved solid concn + 2.858 incubation temp | 63.77 |

| ATCC 12980 | Total viable cells/coupon = 4.97 + 0.3707 incubation time – 11.60 total dissolved solid concn + 0.1192 incubation temp | 74.01 |

Incubation temperature is in degrees Celsius, total dissolved solid concentration is percent (weight/volume), and incubation time is in hours for biofilm formation by the indicated G. stearothermophilus strains. The reported parameters are significant at a P value of <0.05.

TABLE 2.

Regression analysis of the effect of incubation temperature, total dissolved solid concentration, and incubation time on spore formation by G. stearothermophilusa

| Strain | Regression equation of the best-fitting model | Adjusted R2 value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Total spores/coupon = −16.84 + 0.426 incubation time − 16.52 total dissolved solid concn + 0.2995 incubation temp | 58.81 |

| D1 | Total spores/coupon = −5.66 + 1.162 incubation time − 27.30 total solid concn + 0.1270 incubation temp − 0.0432 incubation time × incubation time | 70.24 |

| P3 | Total spores/coupon = −16.41 + 1.844 incubation time − 24 total dissolved solid concn + 0.2223 incubation temp – 0.0647 incubation time × incubation time | 75.76 |

| ATCC 12980 | Total spores/coupon = −172.6 − 1.924 incubation time − 12.45 total dissolved solid concn + 6.05 incubation temp + 0.0893 incubation time × incubation time − 0.0485 incubation temp × incubation temp | 86.92 |

Incubation temperature is in degrees Celsius, total dissolved solid concentration is percent (weight/volume), and incubation time is in hours for biofilm formation by the indicated G. stearothermophilus strains. The reported parameters are significant at a P value of <0.05.

At 55°C, biofilm formation by A1 and D1and P3 was delayed in 20% (wt/vol) RSM compared with that in 10% (wt/vol) RSM. Preliminary studies conducted in our laboratory (data not shown) indicated that the addition of lactose in excess to 10% (wt/vol) RSM did not affect biofilm formation, whereas the addition of milk protein in excess to 10% (wt/vol) RSM negatively affected biofilm and spore formation by A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 at 55°C.

Effect of milk proteins on biofilm and spore formation.

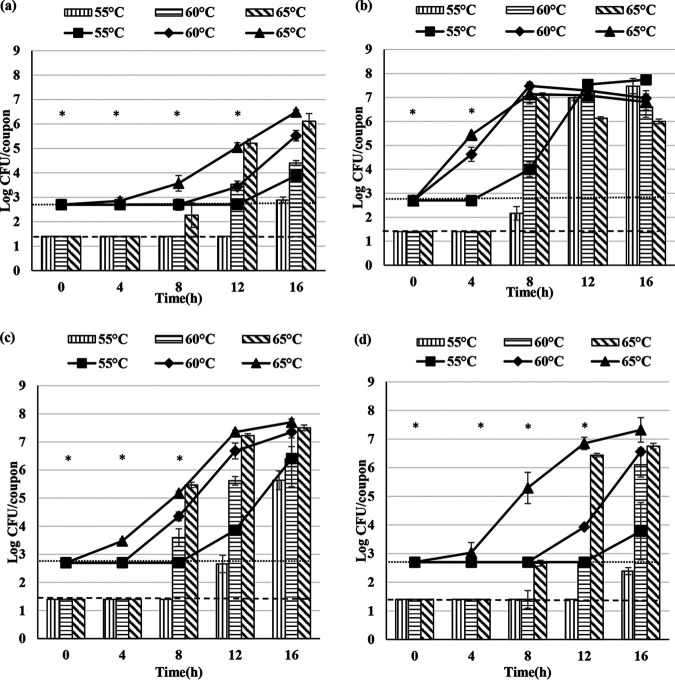

Biofilm and spore formation in the presence of 10% (wt/vol) RSM with 4% (wt/vol) milk protein concentrate (MPC) was studied (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Total viable cells and spores obtained from biofilms of G. stearothermophilus A1 (a), D1 (b), P3 (c), and ATCC 12980 (d) in 10% (wt/vol) RSM with 4% (wt/vol) MPC added in excess. The bar graph represents the total spores and the line graph represents total viable cells attached to the stainless steel coupon. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates. Dotted lines represent minimum detection limits of 1.4 and 2.7 log CFU/coupon for total spore numbers and total viable cells, respectively. “*” represents one or more observations below the detection limit.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentrations of total viable cells and spores per coupon, the onset of biofilm formation for A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 50°C. At 60°C, the onset of biofilm formation for A1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed; however, there was no such delay in biofilm formation by D1 at 60°C. At 65°C, there was no delay in the biofilm formation observed for A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980. The onset of spore formation for A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 55, 60, and 65°C.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentrations of total viable cells and spores released into the milk, the release of spores from G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 was apparently delayed at 55, 60, and 65°C.

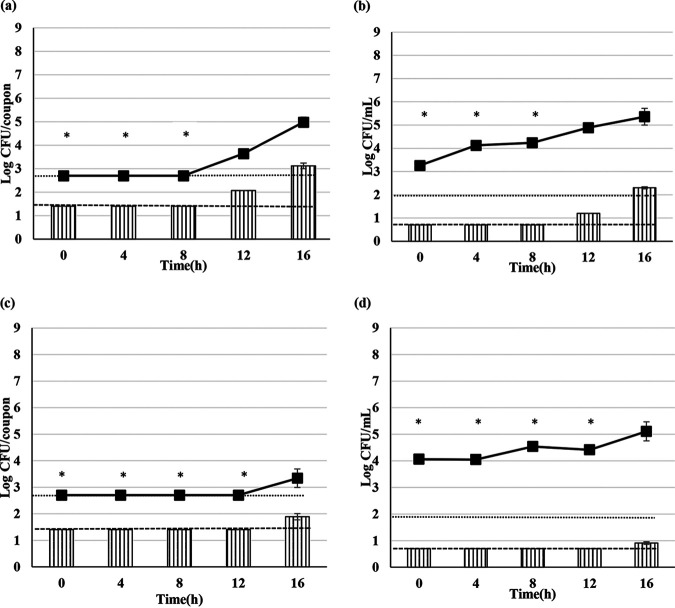

The addition of 4% (wt/vol) MPC to 10% (wt/vol) RSM delayed the biofilm formation for A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 at 55°C in comparison with the results obtained in the presence of 10% (wt/vol) RSM (Fig. 1). In order to determine the effect of individual milk protein (casein and whey) on biofilm formation, strain A1 was selected, as this showed the longest apparent delay in biofilm formation (0 to 12 h) in the presence of 4% MPC in 10% RSM at 55°C. Biofilm and spore formation of A1 was determined in the presence of 3.2% (wt/vol) sodium caseinate and 0.8% (wt/vol) whey protein concentrate (WPC) added in 10% (wt/vol) RSM at 55°C (Fig. 4). The concentrations of casein and whey protein were chosen in accordance with their ratio in milk.

FIG 4.

Total viable cells and spores of G. stearothermophilus A1 in 10% (wt/vol) RSM with 0.8% (wt/vol) WPC (a and b) and 4.2% (wt/vol) sodium caseinate (c and d) added at 55°C obtained from the biofilms (a and c) and released into the milk (b and d). The bar graph represents the total spores and line graph represents total viable cells, respectively. Error bars represent standard deviations of triplicates. Dotted lines represent minimum detection limits of 1.4 and 2.7 log CFU/coupon (a and c) and 0.7 and 2.0 log CFU/ml (b and d) for total spore numbers and total viable cells, respectively. “*” represents one or more observations below the detection limit.

In comparison with the minimum detectable concentrations of total viable cells and spores per coupon, the addition of 0.8% (wt/vol) WPC and 3.2% (wt/vol) sodium caseinate to 10% (wt/vol) RSM delayed biofilm formation at 55°C. Spore formation by A1 was also apparently delayed in the presence of WPC and sodium caseinate. The results obtained for the addition of 3.2% (wt/vol) sodium caseinate to 10% (wt/vol) RSM were similar to the results previously obtained with the addition of 4% (wt/vol) MPC (Fig. 3).

In 1993, Helke et al. (18) concluded that casein, α-lactalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin inhibited the attachment of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium to stainless steel and Buna-N surfaces when present in the attachment menstruum or when the surfaces were pretreated with these proteins. Conditioning films made of whey protein isolate (WPI), β-lactoglobulin, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) have been shown to have a transient effect by slowing down the adhesion of Listeria innocua to polystyrene surfaces (19). Individual milk proteins α-casein, β-casein, κ-casein, and α-lactalbumin have been known to reduce the attachment of Staphylococcus aureus and L. monocytogenes to stainless steel surfaces (20). However, the extent of bacterial attachment depends on the type of surface and the bacterial species involved (21). Competition between various components present in milk might be the reason behind the reduced bacterial attachment (21, 22). The conditioning film-like layer can be formed in <5 h on clean surfaces (23). This layer can affect surface properties, i.e., free surface energy, hydrophobicity, and electrostatic charge used in food processing environments (24). Reversible attachment starts between the electrically charged surface of the bacteria and the conditioning film. Following reversible attachment, irreversible attachment occurs by aid of fimbria, pili, and secreted extracellular components (25). One of the major factors affecting the tight binding of the bacteria to the preconditioned surface is incubation temperature. Elevated temperatures, 30 and 47°C, have been shown to increase the surface hydrophobicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, thereby aiding their attachment to polystyrene surfaces (26). We propose that the preconditioning layers of adsorbed milk protein can play a vital role in the attachment of dairy isolates of Geobacillus spp. to stainless steel surfaces, and this needs further investigation. This is the first study in which the effect of milk proteins on biofilm and spore formation by G. stearothermophilus, a thermophilic bacterium, has been identified.

In this study, planktonic cells underwent transition to a sessile state upon attachment to the stainless steel surface. Primary biofilm cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 have been known to exhibit a lag phase contributing toward their adaptation to a sessile environment (27). Nutrient concentration of the growth medium and the phenotypic origin of the inoculum have been known to influence the lag phase of biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and Pseudomonas fluorescens CT07 grown using a continuous-flow system (28). We predict that an in-depth study focusing on the phenotypic and genotypic changes in the cells from a planktonic to a sessile state of growth may help further our understanding on the effects of different abiotic factors on the lag phase during biofilm formation by G. stearothermophilus.

Conclusion.

In this study, the preferred temperature for biofilm and spore formation of G. stearothermophilus A1, D1, and P3 was 65°C. Increasing the total dissolved solid concentration extended the apparent delay in the onset of biofilm and spore formation to detectable concentrations of all the strains at 55°C. Similarly, the addition of milk proteins exhibited an apparent delay in the onset of biofilm and spore formation to detectable concentrations by G. stearothermophilus A1 at 55°C, with sodium caseinate having the greatest effect. Pareto analysis revealed that strain variation is the most influential factor impacting biofilm and spore formation among A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980. These findings indicate that preconditioning of stainless steel surfaces using adsorbed milk proteins may play a vital role in delaying biofilm and spore formation by thermophilic bacteria during the manufacture of dairy products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture preparation.

G. stearothermophilus strains A1, D1, and P3, isolated from the evaporator section of a New Zealand milk powder manufacturing plant, were specifically chosen due to the variation in their abilities to form biofilms and spores in the milk environment (16). In this study, G. stearothermophilus ATCC 12980 was used as a reference strain. Cultures of A1, D1, P3, and ATCC 12980 were prepared by batch culturing in Trypticase soy broth (TSB; BD Biosciences, USA) for 12 h at 55°C, washed twice, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Oxoid, UK).

Design and assembly of the CDC biofilm reactor.

CDC biofilm reactors (CBR 90; Biosurface Technologies, USA) were used for these experiments. Stainless steel coupons (10-mm diameter, 3 mm thick, 304 grade with a 2B finish) were used. The coupons were prepared by soaking in 99.5% acetone (Merck, USA) for 12 h, rinsed with distilled water, suspended in 5% (wt/vol) Pyroneg solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and cleaned using an ultrasonic cleaner (Agar Scientific, UK) for 60 min. Following the cleaning steps, coupons were rinsed in distilled water and sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 min. This treatment was repeated after every experiment. The reactor was then assembled and all components were autoclaved before use.

Inoculation of the CDC biofilm reactor.

Sterile reconstituted skim milk (RSM) was prepared by dissolving 10 or 20% (wt/vol) instant skim milk powder (Fonterra Ltd., New Zealand) in water and then ultrahigh-temperature (UHT) treated at 142°C for 8 s. Twenty liters of sterile RSM was inoculated with 200 ml of the 12-h culture at the start of the reactor run. The milk container was kept at 4°C throughout the experiment. The inoculated RSM was delivered at a constant flow rate of 25 ml/min, which was selected to achieve a residence time of 14 min, lower than the doubling time of all the strains to ensure that the washing out of suspended cells represented only those released from the biofilm.

CDC reactor runs.

The incubation temperature was maintained at either 55, 60, or 65°C during an entire reactor run of 16 h. The temperature within the reactor was continuously monitored using a thermometer connected to a digital stir hot plate (Biosurface Technologies, USA). The baffle speed in the reactor was maintained at 100 rpm throughout the experiment. Two coupon rods holding three coupons each were carefully removed at 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16 h. The first samples were taken as soon as the desired heating temperature was reached were referred to as 0 h.

Enumeration of bacterial cells and spores.

The number of culturable cells in the biofilm was determined using a bead vortex mixing method as described previously (29). In short, the coupons were washed by being dipped in PBS and placed in 25-ml sterile containers filled with 5 ml of PBS and 5 g of glass beads (diameter = 100 μm; Sigma-Aldrich). The containers were mixed by vortexing at maximum speed for 1 min to dislodge the cells from the coupon and to obtain individual cells in the sample. Serial 10-fold dilutions were made using PBS and spread plated onto tryptic soy agar (TSA), and CFU were counted after 18 h of incubation at 55°C. To determine the spore count, the 25-ml containers were heat treated at 90°C for 30 min prior to the CFU enumeration (30). CFU enumeration of total viable cells and total spores per coupon was performed through drop and spread plate methods, respectively (31).

Statistical analysis.

Regression analysis was performed using Minitab 19. Based on the regression analysis, the Pareto chart was constructed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the financial support provided by The School of Food and Advanced Technology, Massey University, New Zealand.

We also acknowledge the assistance of J. Gilliland (Massey University, New Zealand) with the pilot plant work. We give special thanks to Nihal Jayamaha (SF&AT, Massey University, New Zealand) for assistance with the statistical analyses.

Murali Kumar is a Ph.D. student who performed the experimental work and drafted the manuscript. Steve Flint and Jon Palmer are the Ph.D. supervisors for this work, providing guidance for the study, and edited the drafts of the manuscript. Sawatdeenaruenat Chanapha and Chris Hall provided technical support for this work. The order of the author names in the byline was based on the level of contribution to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nazina TN, Tourova TP, Poltaraus AB, Novikova EV, Grigoryan AA, Ivanova AE, Lysenko AM, Petrunyaka VV, Osipov GA, Belyaev SS, Ivanov MV. 2001. Taxonomic study of aerobic thermophilic bacilli: descriptions of Geobacillus subterraneus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Geobacillus uzenensis sp. nov. from petroleum reservoirs and transfer of Bacillus stearothermophilus, Bacillus thermocatenulatus, Bacillus thermoleovorans, Bacillus kaustophilus, Bacillus thermodenitrificans to Geobacillus as the new combinations G. stearothermophilus, G. thermocatenulatus, G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus, G. thermoglucosidasius and G. thermodenitrificans. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51:433–446. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-2-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott SA, Brooks JD, Rakonjac J, Walker KMR, Flint SH. 2007. The formation of thermophilic spores during the manufacture of whole milk powder. Int J Dairy Technol 60:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0307.2007.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay D, Flint S. 2009. Biofilm formation by spore-forming bacteria in food processing environments, p 270–299. In Fratamico PM, Annous BA, Gunther NW, IV (ed), Biofilms in the food and beverage industries. Woodhead Publishing Limited, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess SA, Lindsay D, Flint SH. 2010. Thermophilic bacilli and their importance in dairy processing. Int J Food Microbiol 144:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchand S, De Block J, De Jonghe V, Coorevits A, Heyndrickx M, Herman L. 2012. Biofilm formation in milk production and processing environments; influence on milk quality and safety. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 11:133–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00183.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giaouris E, Chorianopoulos N, Nychas G-JE. 2005. Effect of temperature, pH, and water activity on biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica Enteritidis PT4 on stainless steel surfaces as indicated by the bead vortexing method and conductance measurements. J Food Prot 68:2149–2154. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.10.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tango CN, Akkermans S, Hussain MS, Khan I, Van Impe J, Jin YG, Oh DH. 2018. Modeling the effect of pH, water activity, and ethanol concentration on biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus. Food Microbiol 76:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn SJ, Burne RA. 2007. Effects of oxygen on biofilm formation and the AtlA autolysin of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 189:6293–6302. doi: 10.1128/JB.00546-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgess SA, Brooks JD, Rakonjac J, Walker KM, Flint SH. 2009. The formation of spores in biofilms of Anoxybacillus flavithermus. J Appl Microbiol 107:1012–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Munir MT, Udugama I, Yu W, Young BR. 2018. Modelling of a milk powder falling film evaporator for predicting process trends and comparison of energy consumption. J Food Eng 225:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfa Laval/Tetra Pak. 1995. Dairy processing handbook. Tetra Pak Processing Systems AB, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flint S, Palmer J, Bloemen K, Brooks J, Crawford R. 2001. The growth of Bacillus stearothermophillus on stainless steel. J Appl Microbiol 90:151–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baril E, Coroller L, Couvert O, El Jabri M, Leguerinel I, Postollec F, Boulais C, Carlin F, Mafart P. 2012. Sporulation boundaries and spore formation kinetics of Bacillus spp. as a function of temperature, pH and aw. Food Microbiol 32:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoštacká A, Čižnár I, Štefkovičová M. 2010. Temperature and pH affect the production of bacterial biofilm. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 55:75–78. doi: 10.1007/s12223-010-0012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson RE, Ross T, Bowman JP. 2011. Variability in biofilm production by Listeria monocytogenes correlated to strain origin and growth conditions. Int J Food Microbiol 150:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess SA, Flint SH, Lindsay D. 2014. Characterization of thermophilic bacilli from a milk powder processing plant. J Appl Microbiol 116:350–359. doi: 10.1111/jam.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saravanan N, Limnamol VP, Kumar S. 2014. Role of microbial aggregation in biofilm formation by bacterial strains isolated from offshore finfish culture environment. Indian J Geo-Marine Sci 43:2118–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helke DM, Somers EB, Wong ACL. 1993. Attachment of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella typhimurium to stainless steel and Buna-N in the presence of milk and individual milk components. J Food Prot 56:479–484. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robitaille G, Choinière S, Ells T, Deschènes L, Mafu AA. 2014. Attachment of Listeria innocua to polystyrene: effects of ionic strength and conditioning films from culture media and milk proteins. J Food Prot 77:427–434. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes LM, Lo MF, Adams MR, Chamberlain AHL. 1999. Effect of milk proteins on adhesion of bacteria to stainless steel surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:4543–4548. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.10.4543-4548.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher M. 1976. The effects of proteins on bacterial attachment to polystyrene. J Gen Microbiol 94:400–404. doi: 10.1099/00221287-94-2-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speers JGS, Gilmour A. 1985. The influence of milk and milk components on the attachment of bacteria to farm dairy equipment surfaces. J Appl Bacteriol 59:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1985.tb03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittelman MW. 1998. Structure and functional characteristics of bacterial biofilms in fluid processing operations. J Dairy Sci 81:2760–2764. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson JS, Koohmaraie M. 1989. Cell surface charge characteristics and their relationship to bacterial attachment to meat surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:832–836. doi: 10.1128/AEM.55.4.832-836.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokare CR, Chakraborty S, Khopade AN, Mahadik KR. 2009. Biofilm: importance and applications. Indian J Biotechnol 8:159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cappello S, Guglielmino SPP. 2006. Effects of growth temperature on the adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 to polystyrene. Ann Microbiol 56:383–385. doi: 10.1007/BF03175037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rice AR, Hamilton MA, Camper AK. 2000. Apparent surface associated lag time in growth of primary biofilm cells. Microb Ecol 40:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s002480000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroukamp O, Dumitrache RG, Wolfaardt GM. 2010. Pronounced effect of the nature of the inoculum on biofilm development in flow systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6025–6031. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00070-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayrapetyan H, Muller L, Tempelaars M, Abee T, Nierop Groot M. 2015. Comparative analysis of biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus reference strains and undomesticated food isolates and the effect of free iron. Int J Food Microbiol 200:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar M, Flint SH, Palmer J, Plieger PG, Waterland M. 2019. The effect of phosphate on the heat resistance of spores of dairy isolates of Geobacillus stearothermophilus. Int J Food Microbiol 309:108334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naghili H, Tajik H, Mardani K, Razavi Rouhani SM, Ehsani A, Zare P. 2013. Validation of drop plate technique for bacterial enumeration by parametric and nonparametric tests. Vet Res Forum 4:179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]