Abstract

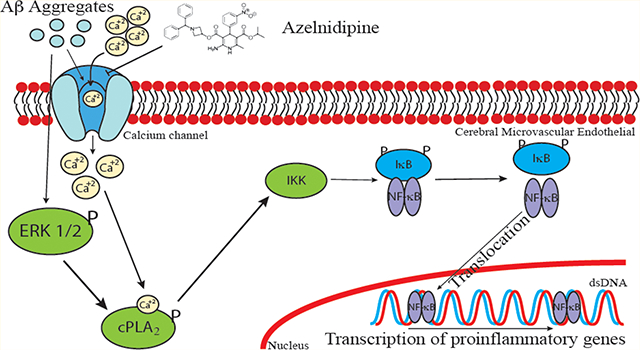

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a condition depicting cerebrovascular accumulation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ), is a common pathological manifestation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In this study, we investigated the effects of Azelnidipine (ALP), a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker known for its treatment of hypertension, on oligomeric Aβ (oAβ)-induced calcium influx and its downstream pathway in immortalized mouse cerebral endothelial cells (bEND3). We found that ALP attenuated oAβ-induced calcium influx, superoxide anion production, and phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and calcium-dependent cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2). Both ALP and cPLA2 inhibitor, methylarachidonyl fluorophosphate (MAFP), suppressed oAβ-induced translocation of NFκB p65 subunit to nuclei, suggesting that cPLA2 activation and calcium influx are essential for oAβ-induced NFκB activation. In sum, our results suggest that calcium channel blocker could be a potential therapeutic strategy for suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in Aβ-stimulated microvasculature in AD.

Keywords: Amyloid-β peptide, Azelnidipine, cytosolic phospholipase A2, Alzheimer’s, endothelial cells, NFκB

Graphical Abstract

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is marked by deposition of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in cerebral vessels,1,2 and is associated with allocortical/hippocampal microinfarcts and cognitive decline.3 Such deposition of Aβ in the cerebrovasculature can result in alterations of cerebral endothelial cell (CEC) and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) function.

Over these years, there is accumulating evidence showing the ability for Aβ to alter CEC function including cell integrity,4 calcium, and redox homeostasis.5 For example, Aβ upregulates receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE),4 and induce RAGE-dependent endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.6 Aβ also triggers the oxidant pathway by increasing assembly of NADPH oxidase subunits leading to a subsequent increase in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activations of ERK1/2 and cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2).7 In terms of the role of Aβ-stimulated CECs in neuroinflammation, Aβ was found to promote monocyte adhesion to CECs,8 upregulate p-selectin at the CEC surface, induce cytoskeleton reorganization, and decrease the force for membrane tether formation via sialyl-Lewisx (sLex)-selectin bonding.9 Therefore, there is increasing interest to research strategies to attenuate Aβ-induced toxicity and alterations of cell function in cerebrovascular cells.10–12

Aβ is known to affect Ca2+ homeostasis in CECs through the disruption of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) function,5 but it is also possible that it affects Ca2+ homeostasis through its action on the Ca2+-permeable channels.13,14 Calcium channel blockers have been reported to improve Aβ-impaired mouse cognitive function.15 However, the mechanism(s) underlying the beneficial effects of calcium channel blocker have yet to be fully understood. Dihydropyridine (DHP) drugs, such as Nimodipine and verapamil, are L-type calcium channel blockers commonly used to suppress blood pressure.16 Azelnidipine (ALP) belongs to the DHP family and is known for its slow delivery and long-lasting effects.17,18 There is evidence for ALP along with other DHP drugs to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects and even facilitate clearance of Aβ across the BBB.19–24 However, its action on endothelial cells and its ability to mitigate cytotoxic effects of Aβ have not been investigated in detail. In this study, we demonstrated that ALP was able to attenuate superoxide-mediated cPLA2 and NFκB pathways in oAβ-stimulated mouse cerebral endothelial cells (bEND3). Our results further suggest that calcium channel blocker could be a potential therapeutic strategy for treating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in Aβ-stimulated microvasculature in AD.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

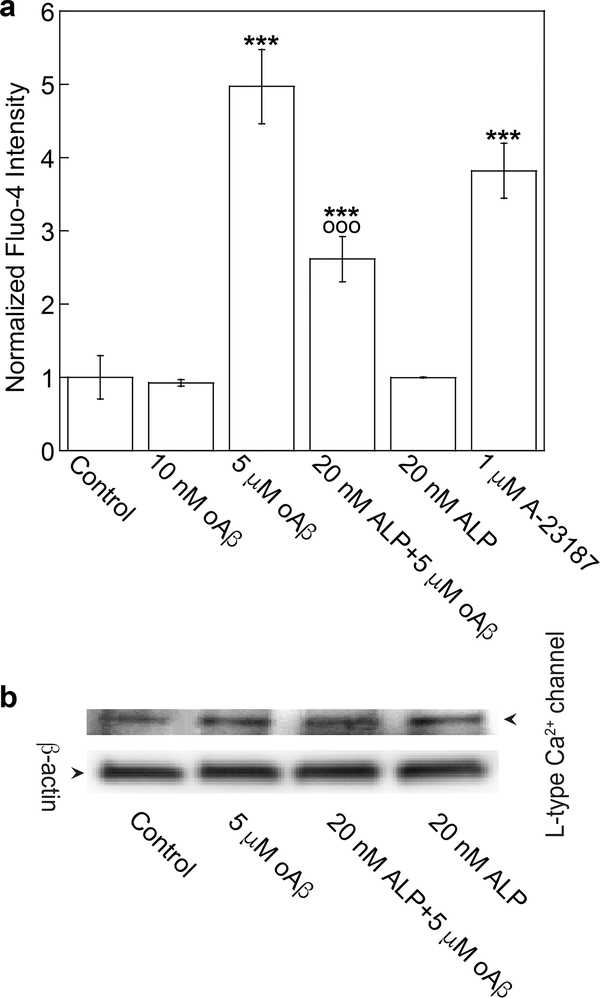

Since neurovascular dysfunction is implicated in AD, our goal here is to investigate whether ALP, a calcium ion channel blocker, can mitigate the cytotoxic effects of oligomeric Aβ (oAβ) on immortalized cerebral endothelial cells (bEND3). To examine the effect of oAβ on Ca2+ content in CECs, Fluo-4 was applied to quantify the relative Ca2+ content in bEND3 cells. Exposing cells to 5 μM oAβ for 15 min increased intracellular Ca2+, and the increase was partially suppressed by pretreatment of cells with 20 nM ALP for 4h (Figure 1a). Neither ALP alone nor 10 nM oAβ imposed any effect on intracellular Ca2+. For a positive control, calcium ionophore A-23187 (1 μM) also increased intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 1a). These results suggest that oAβ activated L-type calcium ion channel to induce Ca2+ influx in CECs, which was attenuated by ALP, a specific L-type calcium ion channel blocker.25 Since ALP and oAβ treatments did not impose any effect on the expression of L-type Ca2+ channel (Figure 1b), these results were unlikely driven by the expression level change of the L-type Ca2+ channel. The partial suppression of increased Ca2+ induced by oAβ by ALP is consistent with the notion that this form of Aβ can elevate Ca2+ content through other mechanisms, such as the formation of calcium-permeable amyloid pore channels as described previously,26–29 as well as disruption of ER function.5

Figure 1.

ALP attenuated oAβ-induced calcium influx. (a) bEND3 cells were incubated with the calcium indicator (2 μM Fluo-4, AM), pretreated with or without 20 nM ALP for 4 h, and then incubated with 5 μM oAβ or 1 μM A-23187 (a positive control) for 15 min. Normalized data are expressed as mean ± SE (***p < 0.001, comparing with control group; ○○○p < 0.001, comparing with 5 μM oAβ treatment only group) from four independent experiments (N = 4). (b) Representative Western blot images of L-type Ca2+ channel and β-actin in cells with different treatments.

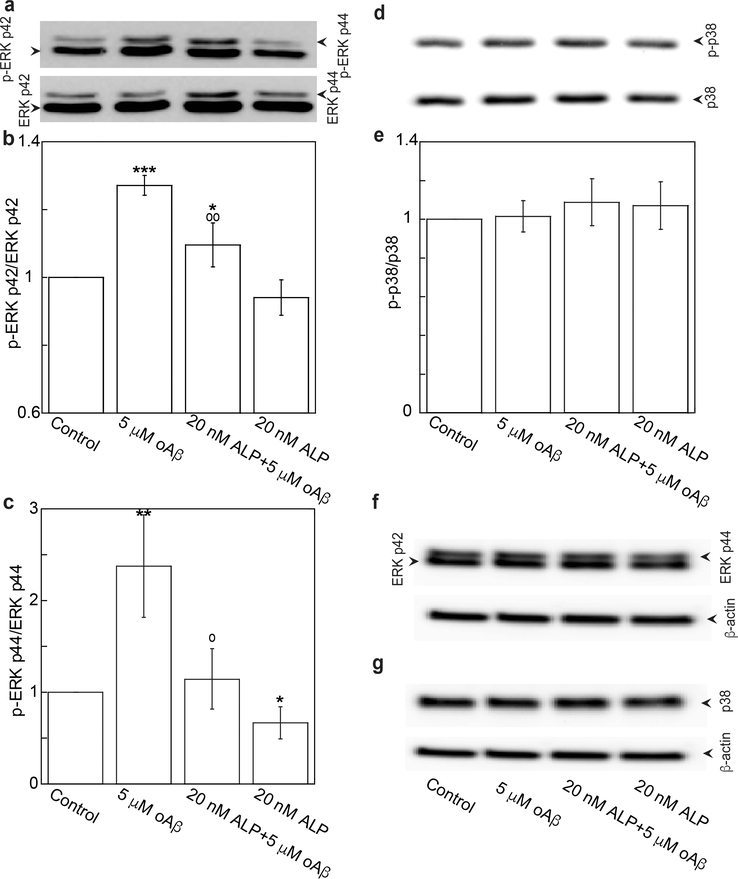

oAβ has been shown to trigger many signaling cascades. In this study, we demonstrate that oAβ triggered phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 pathway (Figure 2a, b, and c), but not the p38 pathway (Figure 2d and e) in bEND3 cells. Pretreatment of cells with 20 nM of ALP for 4 h significantly suppressed the oAβ-triggered ERK1/2 pathway (Figure 2a, b, and c). These treatments did not alter the expressions of total ERK 1/2 and p38 (Figure 2f and g). These results suggest that the activation of L-type calcium channel to produce Ca2+ influx is necessary for oAβ to trigger stimulation of the ERK1/2 pathway. In fact, similar observations have been demonstrated in other cell types. For example, in HEK cells, calcium influx was shown to induce ERK1/2 activation by pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP).30

Figure 2.

ALP attenuated oAβ-induced phosphorylation of ERK p42 and p44. bEND3 cells were treated with 20 nM ALP for 4 h, and followed by treatment with or without 5 μM oAβ for 15 min. (a–c) Phospho- and total ERK p42/p44 and (d, e) phospho- and total p38 were quantified with Western blot analysis and expressed as ratio of phospho to total and as fraction percentages of the control group with the mean ± SD from four independent experiments (N = 4) (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 comparing with control group; ○○p < 0.01, ○p < 0.05 comparing with 5 μM oAβ treatment only group). (f, g) Representative Western blot images of total ERK p44/p42, p38, and β-actin.

Aβ-triggered activations of MAP kinase pathways in endothelial cells are likely dependent on the types of endothelial cell lines and other factors, such as the concentration and treatment time of Aβ. Extracellular Aβ was found to decrease phosphorylations of ERK1/2 and p38 in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs), and human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs).31 However, it also increased phosphorylations of JNK and p38 in immortalized human brain endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3), leading to a downregulation of the tight junction protein, occludin, and an increase in paracellular permeability.32 In fact, increased phosphorylations of p38, JNK, c-Jun, and ERK have been found in human microvessels isolated from AD brains.33 However, in the oxidative stress and neuroinflammation environment of AD brains, increased phosphorylations of MAPKs in CECs are likely triggered not only by Aβ, but also by other stressors and proinflammatory molecules. For example, we have reported that TNFα increased phosphorylations of p38 and occludin, leading to an increase in paracellular permeability in hCMEC/D3 cells.34

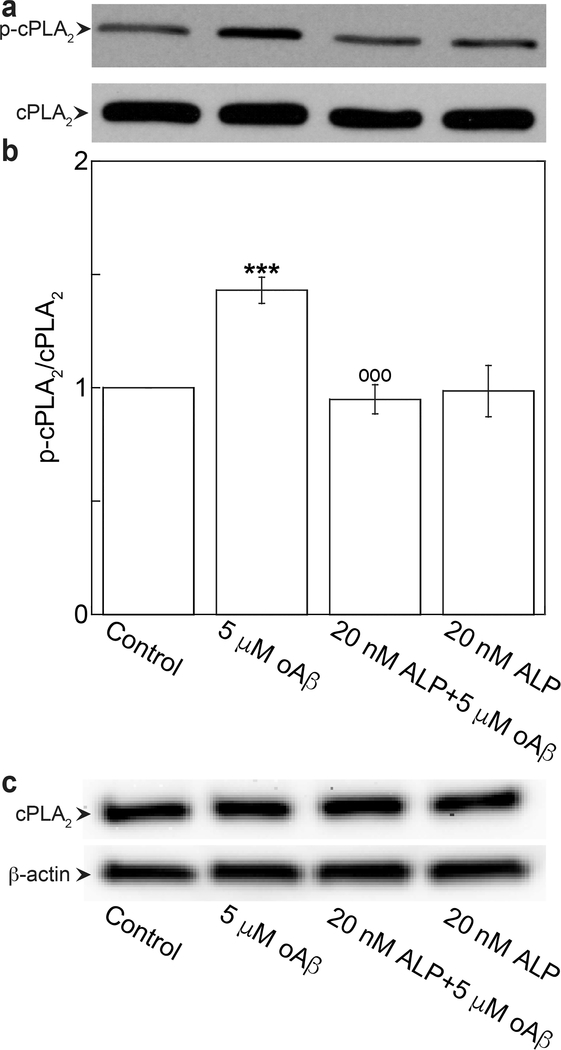

We have previous demonstrated that ERK1/2 is the upstream pathway of oAβ-triggered calcium-dependent cPLA2 activation in bEND3 cells.7 Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that ALP suppressed oAβ-induced cPLA2 activation through the ERK1/2 pathway. As shown in Figure 3a and b, exposing cells to 5 μM oAβ for 30 min resulted in increased phosphorylation of cPLA2, and the increase was suppressed by the pretreatment of cells with 20 nM ALP for 4 h (Figure 3a and b). These treatments did not alter the expressions of total cPLA2 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Azelnidipine attenuated oAβ-induced phosphorylation of cPLA2. bEND3 cells were treated with 20 nM ALP for 4 h, followed by treatment with or without 5 μM oAβ for 30 min. (a, b) Phospho- and total cPLA2 were quantified by Western blot analysis. Data are expressed as a ratio of phospho- to total protein and normalized by the control group with the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (N = 3) (***p < 0.001, comparing with control group; ○○○p < 0.001, comparing with 5 μM oAβ treatment only group). (c) Representative Western blot images of total cPLA2 and β-actin.

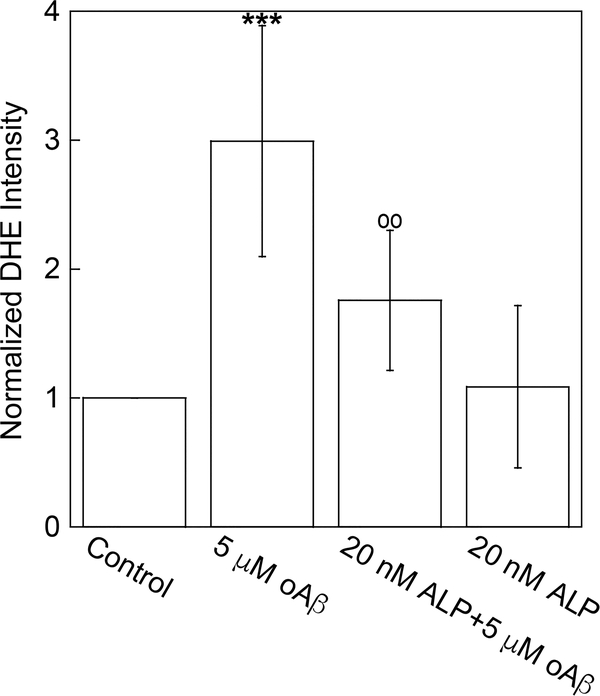

cPLA2 activity or its enzymatic product, arachidonic acid (AA) has been found to be required for translocation of NADPH oxidase cytosolic subunits, p67phox and p47phox, a crucial step of NADPH oxidase assembling, resulting in superoxide anion production.35 Since ALP suppressed oAβ-induced cPLA2 activation (Figure 3a and b), it should also suppress oAβ-induced superoxide anion production. To quantify superoxide anion production, we measured the fluorescent intensity of dihydroethidium (DHE) in cells. Results in Figure 4 show that oAβ significantly increased superoxide anion production, and the increase was suppressed by the pretreatment of cells with 20 nM ALP.

Figure 4.

Azelnidipine attenuated oAβ-induced superoxide anion production. bEND3 cells were treated with 20 nM ALP for 4 h, followed by treatment with or without 5 μM oAβ for 30 min. Superoxide anion production was quantified by measuring the DHE intensity within each sample. Data are normalized by the control group with the mean ± SD from three independent experiments (N = 3) (***p < 0.001, comparing with control group; ○○p < 0.01 comparing with 5 μM oAβ treatment only group).

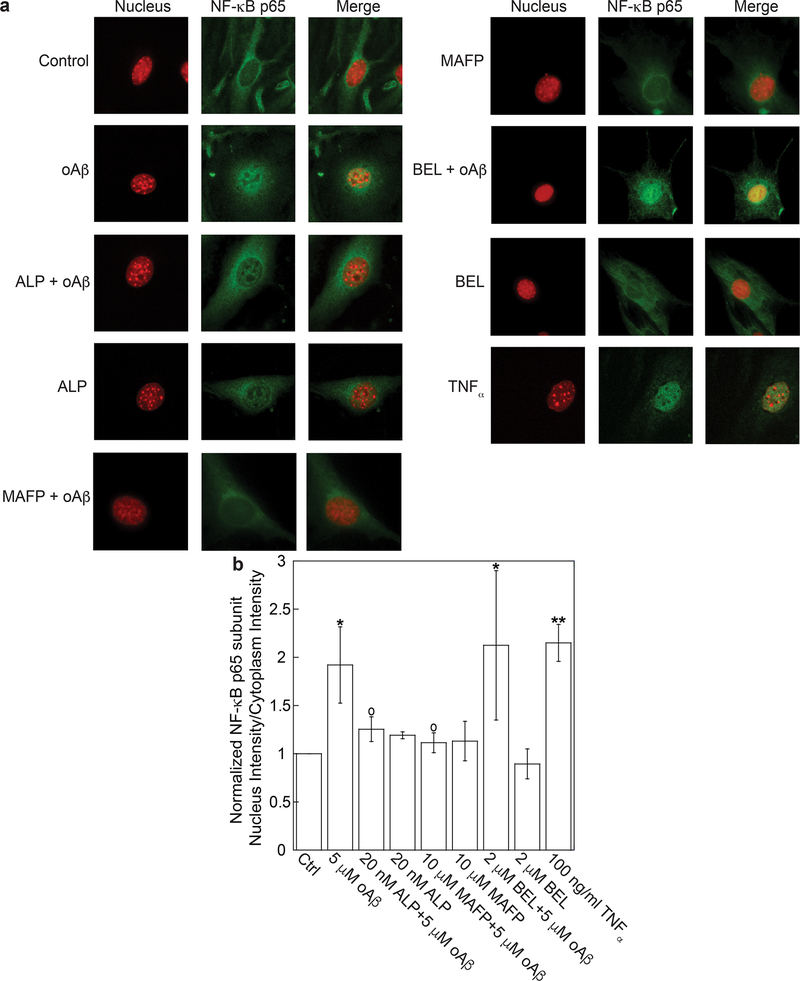

To characterize the effects of ALP on oAβ-induced NFκB activation, we employed immunofluorescence microscopy to measure the relative intensity of NFκB p65 subunit in nuclei (i.e., the ratio of p65 intensity in nuclei to that in cytoplasm). We found that oAβ increased p65 intensity in nuclei, and the increase was suppressed by pretreatment of cells with ALP and methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP), a cPLA2 inhibitor, but not with bromoenol lactone (BEL), a specific inhibitor for calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) (Figure 5). For a positive control, we demonstrated that TNFα, a proinflammatory cytokine known to stimulate NFκB pathway, also increased p65 intensity in nuclei (Figure 5).36 These results suggest that both calcium influx through calcium channels and cPLA2 activation were essential for NFκB activation in oAβ-stimulted bEND3 cells. Our results are also consistent with prior studies reporting that ERK,37 cPLA2,38 and AA release39 was essential for NFκB activation.

Figure 5.

Azelnidipine attenuated oAβ-induced NFκB activation. bEND3 cells were treated with 20 nM ALP, 5 μM Aβ, both ALP and Aβ, 10 μM MAFP, both MAFP and Aβ, 2 μM BEL, and both BEL and Aβ or 100 ng/mL TNFα (positive control) to yield a total of nine datasets. (a) Nucleus staining is represented in red, and NFκB p65 subunit in green immunofluorescence. The merged images were obtained by superposing the nucleus staining and NFκB p65 subunit in the same field acquired using different filter sets. (b) NFκB activation was quantified by the ratio of NFκB p65 subunit intensity in nuclei to that in cytoplasm. Data are expressed with the mean ± SD from four independent experiments reported (N = 4) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, comparing with control group; ○p < 0.05, comparing with 5 μM oAβ treatment only group).

In sum, this study demonstrated that oAβ activated NFκB through an oxidative pathway involving calcium influx, ERK, and cPLA2, and these events were suppressed by the L-type calcium channel blocker, ALP. These results provide new information for developing therapeutic strategies for AD that calcium channel blockers can be a remedy to counteract microvasculature dysfunction induced by oAβ.

METHODS

bEND3Mouse Cerebral Endothelial Cells.

Passage 21 (P.21) bEND3 mouse cerebral endothelial cell line was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in T25 flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) with 10 mL of cell culture medium (10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA, v/v), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S, v/v), and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with phenol red and high glucose (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Cells at passages 22–29 were used for experiments. For experiments, cells were subcultured into dishes or 6-, 12-, or 96-well-plates (Corning, Corning, NY). All experiments including the control group received the same concentration of DMSO and Ham’s F12 (DMSO and Ham’s F12 was used to dissolve Aβ).

Preparation of Aβ42 Oligomers.

Human Aβ42 was obtained from Anaspec (Fremont, CA), and the oligomeric form was prepared according to the protocol described by Dahlgren et al.40

Preparation of Azelnidipine.

Azelnidipine (ALP) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was weighted and sealed in Eppendorf tubes and stored at −20 °C in the dark. For cell treatments, ALP was dissolved in DMSO and further diluted with treating medium to reach the final concentration of 20 nM.

Measurement of Ca2+ in Cells.

bEND3 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After reaching 70–80% confluence, cells were serum starved for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 20 nM ALP for 4 h, followed by loading with 2 μM Fluo-4, AM (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in DMEM for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed with DPBS twice and stabilized in DMEM without the fluorescent probe for 30 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, cells were treated with 10 nM or 5 μM oAβ for 15 min or 1 μM A-23187 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).41 Fluorescent signals were acquired using a Synergy H1Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analysis was employed to measure ERK1/2, p38, or cPLA2 in both phosphorylated and total forms. Cells were subcultured into 6-well plates, and the experiment was carried out when cells reached 90% confluence. For treatments, cells were serum starved for 24 h before pretreatment with 20 nM ALP for 4 h and followed by 5 μM oAβ treatment for 15, 15, 15, and 30 min for respective L-type Ca2+ channel, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and cPLA2 measurements. After treatments, cells were washed with ice-cold DPBS twice and lysed with blue loading buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) mixed with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Cells were scraped off and collected from the 6-well plates into Eppendorf tubes and immediately placed on ice. Samples were then sonicated for 10 s three times, microcentrifuged for 10 s, and boiled for 5 min at 95 °C. After cooling down, samples were stored at −20 °C for further experiments. Equivalent amounts of 40 μL samples together with protein standards were used for electrophoresis in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins in the gel were transferred to 0.45 μM nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in Tris-buffer saline (TBS) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA; TBST) for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in 5% (w/v) BSA or 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in TBS-T with dilution ratio L-type Ca2+ channel (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), p-ERK1/2 (1:1000 dilution), or ERK 1/2 (1:2000 dilution), p-p38 or p38 (1:500 dilution), p-cPLA2 or cPLA2 (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, 1:50 000 dilution). Membranes were washed for 5 min (3×) with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (H&L) antibody (1:3000 dilution) or HRP conjugated anti-mouse IgG (H&L) antibody (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. After washing for 5 min three times with TBST, the membrane was subjected to Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent detection reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) to visualize bands. Bands were detected by using blue autoradiography film (BioExpress, Kaysville, UT), myECL imager (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) or Fuji LAS-3000 image reader (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Band intensity was quantified using a computer running Quantity One software v4.6.6 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For reincubation with antibodies, membranes were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer for 20 min and washed for 5 min (6×) with TBST. After washing, membranes were reincubated with antibodies; each membrane was stripped no more than twice.

Measurement of Superoxide Anions.

Superoxide anion production in cells was measured using a fluorescent probe, dihydroethidium (DHE, Life Technology, Grand Island, NY). To quantify superoxide anion production induced by oAβ in bEND3 cells, cells were serum starved in DMEM, followed by pretreatment with 20 nM Azelnidipine for 4 h. After pretreatment, cells were treated with 5 μM oAβ and 20 μM DHE for 30 min. DHE was first dissolved in DMSO and further diluted in phenol-red free DMEM to achieve the desired final concentration. Fluorescent intensity of DHE was measured at room temperature using a Synergy H1Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Measurement of NFκB p65 in Nuclei.

For quantification of p65 subunit of NFκB in nuclei, cells were subcultured onto precoated coverslips (Neuvitro, Vancouver, WA) in 12-well plates. After reaching 50–60% confluence, cells were serum starved for 24 h and pretreated with 20 nM ALP for 4 h or 10 μM methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP), 2 μM bromoenol lactone (BEL, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) for 30 min. Cells were then treated with 5 μM oAβ for 30 min or 100 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 2 h which was used as a positive control. After treatment, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (w/v) for 15 min, and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were blocked with 5% BSA (w/v) in DPBS for 1 h and incubated with NFκB p65 (C22B4) rabbit monoclonal primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, 1:100 dilution, diluted in 1% BSA in DPBS) overnight at 4 °C. After 16 h, cells were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), F(ab′)2 fragment (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate) secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, 1:1000 dilution, diluted in 1% BSA in DPBS) for 1 h at room temperature. Between each step, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS for 5 min each time. After staining, coverslips were allowed to dry in the dark. Then each coverslip was mounted onto a glass slide with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and allowed to cure for 24 h at room temperature. Images were taken with a Nikon TE-2000U fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) or Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a 60× objective lens. To quantify p65 intensity in nuclei (Inuclei) and cytoplasm (Icytoplasm), fluorescent images were taken using CellProfiler V2.1.1 with a pipeline designed by our lab.42 Inuclei/Icytoplasm was used as a measure for NFκB activation.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests in GraphPad Prism (version 6.01). P-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work received financial support from the National Institute on Aging, Grant 5 R01 AG044404 (to J.C.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van der Vies SM, Rozemuller AJ, van Horssen J, and de Vries HE (2011) Amyloid Beta induces oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 15, 1167–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Burwinkel M, Lutzenberger M, Heppner FL, Schulz-Schaeffer W, and Baier M (2018) Intravenous injection of beta-amyloid seeds promotes cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Acta Neuropathol Commun. 6, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hecht M, Kramer LM, von Arnim CAF, Otto M, and Thal DR (2018) Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer’s disease: association with allocortical/hippocampal microinfarcts and cognitive decline. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Qosa H, LeVine H 3rd, Keller JN, and Kaddoumi A (2014) Mixed oligomers and monomeric amyloid-beta disrupts endothelial cells integrity and reduces monomeric amyloid-beta transport across hCMEC/D3 cell line as an in vitro blood-brain barrier model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 1842, 1806–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fonseca ACRG, Moreira PI, Oliveira CR, Cardoso SM, Pinton P, and Pereira CF (2015) Amyloid-Beta Disrupts Calcium and Redox Homeostasis in Brain Endothelial Cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 51, 610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chen W, Chan Y, Wan W, Li Y, and Zhang C (2018) Abeta1–42 induces cell damage via RAGE-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress in bEnd.3 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 362, 83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Askarova S, Yang X, Sheng W, Sun GY, and Lee JC (2011) Role of Abeta-receptor for advanced glycation endproducts interaction in oxidative stress and cytosolic phospholipase A(2) activation in astrocytes and cerebral endothelial cells. Neuroscience 199, 375–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Robert J, Button EB, Stukas S, Boyce GK, Gibbs E, Cowan CM, Gilmour M, Cheng WH, Soo SK, Yuen B, Bahrabadi A, Kang K, Kulic I, Francis G, Cashman N, and Wellington CL (2017) High-density lipoproteins suppress Abeta-induced PBMC adhesion to human endothelial cells in bioengineered vessels and in monoculture. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Askarova S, Sun Z, Sun GY, Meininger GA, and Lee JC (2013) Amyloid-beta peptide on sialyl-Lewis(X)-selectin-mediated membrane tether mechanics at the cerebral endothelial cell surface. PLoS One 8, e60972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hur J, Mateo V, Amalric N, Babiak M, Bereziat G, Kanony-Truc C, Clerc T, Blaise R, and Limon I (2018) Cerebrovascular beta-amyloid deposition and associated micro-hemorrhages in a Tg2576 Alzheimer mouse model are reduced with a DHA-enriched diet. FASEB J. 32, 4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Liu C, Chen K, Lu Y, Fang Z, and Yu G (2018) Catalpol provides a protective effect on fibrillary Abeta1–42 -induced barrier disruption in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Phytother. Res. 32, 1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zandl-Lang M, Fanaee-Danesh E, Sun Y, Albrecher NM, Gali CC, Cancar I, Kober A, Tam-Amersdorfer C, Stracke A, Storck SM, Saeed A, Stefulj J, Pietrzik CU, Wilson MR, Bjorkhem I, and Panzenboeck U (2018) Regulatory effects of simvastatin and apoJ. on APP processing and amyloid-beta clearance in blood-brain barrier endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1863, 40–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kagan BL, Hirakura Y, Azimov R, Azimova R, and Lin MC (2002) The channel hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: current status. Peptides 23, 1311–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ye C, Ho-Pao CL, Kanazirska M, Quinn S, Rogers K, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Brown EM, and Vassilev PM (1997) Amyloid-beta proteins activate Ca(2+)-permeable channels through calcium-sensing receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 47, 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhang Z, Chen R, An W, Wang C, Liao G, Dong X, Bi A, Yin Z, and Luo L (2016) A novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and calcium channel blocker SCR-1693 improves Abeta25–35-impaired mouse cognitive function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233, 599–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hess P, Lansman JB, and Tsien RW (1984) Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature 311, 538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kuramoto K, Ichikawa S, Hirai A, Kanada S, Nakachi T, and Ogihara T (2003) Azelnidipine and amlodipine: a comparison of their pharmacokinetics and effects on ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertens. Res. 26, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Nakamura K, and Imaizumi T (2004) Azelnidipine, a newly developed long-acting calcium antagonist, inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced interleukin-8 expression in endothelial cells through its anti-oxidative properties. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 43, 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bachmeier C, Beaulieu-Abdelahad D, Mullan M, and Paris D (2011) Selective dihydropyiridine compounds facilitate the clearance of beta-amyloid across the blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 659, 124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kurobe H, Matsuoka Y, Hirata Y, Sugasawa N, Maxfield MW, Sata M, and Kitagawa T (2013) Azelnidipine suppresses the progression of aortic aneurysm in wild mice model through anti-inflammatory effects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 146, 1501–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Omote Y, Deguchi K, Kono S, Liu W, Kurata T, Hishikawa N, Yamashita T, Ikeda Y, and Abe K (2014) Synergistic neuroprotective effects of combined treatment with olmesartan plus azelnidipine in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 92, 1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tollefson GD (1990) Short-term effects of the calcium channel blocker nimodipine (Bay-e-9736) in the management of primary degenerative dementia. Biol. Psychiatry 27, 1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Morich FJ, Bieber F, Lewis JM, Kaiser L, Cutler NR, Escobar JI, Willmer J, Petersen RC, and Reisberg B (1996) Nimodipine in the treatment of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Drug Invest. 11, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Anekonda TS, Quinn JF, Harris C, Frahler K, Wadsworth TL, and Woltjer RL (2011) L-type voltage-gated calcium channel blockade with isradipine as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 41, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wellington K, and Scott LJ (2003) Azelnidipine. Drugs 63, 2613–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Di Scala C, Yahi N, Flores A, Boutemeur S, Kourdougli N, Chahinian H, and Fantini J (2016) Broad neutralization of calcium-permeable amyloid pore channels with a chimeric Alzheimer/Parkinson peptide targeting brain gangliosides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 1862, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Di Scala C, Chahinian H, Yahi N, Garmy N, and Fantini J (2014) Interaction of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptides with cholesterol: mechanistic insights into amyloid pore formation. Biochemistry 53, 4489–4502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Arispe N, Rojas E, and Pollard HB (1993) Alzheimer disease amyloid beta protein forms calcium channels in bilayer membranes: blockade by tromethamine and aluminum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 567–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rhee SK, Quist AP, and Lal R (1998) Amyloid beta protein-(1–42) forms calcium-permeable, Zn2+-sensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13379–13382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).May V, Clason TA, Buttolph TR, Girard BM, and Parsons RL (2014) Calcium influx, but not intracellular calcium release, supports PACAP-mediated ERK activation in HEK PAC1 receptor cells. J. Mol. Neurosci. 54, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Magrane J, Christensen RA, Rosen KM, Veereshwarayya V, and Querfurth HW (2006) Dissociation of ERK and Akt signaling in endothelial cell angiogenic responses to beta-amyloid. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 996–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Tai LM, Holloway KA, Male DK, Loughlin AJ, and Romero IA (2010) Amyloid-beta-induced occludin downregulation and increased permeability in human brain endothelial cells is mediated by MAPK activation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 1101–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Grammas P, Sanchez A, Tripathy D, Luo E, and Martinez J (2011) Vascular signaling abnormalities in Alzheimer disease. Cleveland Clin. J. Med. 78 (Suppl1), S50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ni Y, Teng T, Li R, Simonyi A, Sun GY, and Lee JC (2017) TNFalpha alters occludin and cerebral endothelial permeability: Role of p38MAPK. PLoS One 12, e0170346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhao X, Bey EA, Wientjes FB, and Cathcart MK (2002) Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) regulation of human monocyte NADPH oxidase activity. cPLA2 affects translocation but not phosphorylation of p67(phox) and p47(phox). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25385–25392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Karin M, and Ben-Neriah Y (2000) Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Zhang H, Wang Z-W, Wu H-B, Li Z, Li L-C, Hu X-P, Ren Z-L, Li B-J, and Hu Z-P (2013) Transforming growth factor-β1 induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in rat vascular smooth muscle cells via ROS-dependent ERK–NF-κB pathways. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 375, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Thommesen L, Sjursen W, Gåsvik K, Hanssen W, Brekke O-L, Skattebøl L, Holmeide AK, Espevik T, Johansen B, and Lægreid A (1998) Selective Inhibitors of Cytosolic or Secretory Phospholipase A2 Block TNF-Induced Activation of Transcription Factor Nuclear Factor-κB and Expression of ICAM-1. J. Immunol. 161, 3421–3430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).van Puijenbroek AA, Wissink S, van der Saag PT, and Peppelenbosch MP (1999) Phospholipase A2 inhibitors and leukotriene synthesis inhibitors block TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation. Cytokine+ 11, 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WB Jr., Baker LK, Krafft GA, and LaDu MJ (2002) Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-beta peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32046–32053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Abbott BJ, Fukuda DS, Dorman DE, Occolowitz JL, Debono M, and Farhner L (1979) Microbial transformation of A23187, a divalent cation ionophore antibiotic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16, 808–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Jones TR, Kang IH, Wheeler DB, Lindquist RA, Papallo A, Sabatini DM, Golland P, and Carpenter AE (2008) CellProfiler Analyst: data exploration and analysis software for complex image-based screens. BMC Bioinf. 9, 482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]