Abstract

Purpose:

The accuracy of existing PET/MR attenuation correction (AC) has been limited by a lack of association between MR signal and tissue electron density. Based upon our finding that longitudinal relaxation rate, or R1, is associated with CT Hounsfield unit in bone and soft tissues in brain, we propose a Deep Learning T1-Enhanced Selection of Linear Attenuation Coefficients (DL-TESLA) method, to incorporate quantitative R1 for PET/MR AC and evaluate its accuracy and longitudinal test-retest repeatability in brain PET/MR imaging.

Methods:

DL-TESLA uses a 3D residual UNet (ResUNet) for pseudo CT (pCT) estimation. With a total of 174 subjects, we compared PET AC accuracy of DL-TESLA to three other methods adopting similar 3D ResUNet structures but using UTE R2*, or DIXON, or T1MPRAGE as input. With images from 23 additional subjects repeatedly scanned, the test-retest differences and within-subject coefficient of variation of standardized uptake value ratios (SUVR) were compared between PET images reconstructed using either DL-TESLA or CT for AC.

Results:

DL-TESLA had 1) significantly lower mean absolute error in pCT; 2) the highest Dice coefficients in both bone and air; 3) significantly lower PET relative absolute error in whole brain and various brain regions; 4) the highest percentage of voxels with a PET relative error within both ±3% and ±5%; 5) similar to CT test-retest differences in SUVRs from cerebrum and mean cortical (MC) region; and 6) similar to CT within-subject coefficient of variation in cerebrum and MC.

Conclusion:

DL-TESLA demonstrates excellent PET/MR AC accuracy and test-retest repeatability.

Keywords: Attenuation Correction, PET/MR, UTE, DIXON, deep learning, MR/CT conversion

1. Introduction

Accurate and precise attenuation correction (AC) is critical for including integrated positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance (PET/MR) imaging in clinical trials. Photon attenuation is the primary factor that determines the quantitative accuracy of PET. Patient AC requires knowledge of the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) map (i.e., μ-map). In PET/CT, the CT Hounsfield unit (HU) is directly associated with tissue electron density; therefore, converting CT HU to LAC at 511 KeV for PET AC is straightforward through a piecewise linear scaling (1). However, as MR signal is not related to electron density, deriving an μ-map using MRI poses a challenge.

Numerous approaches have been proposed to develop attenuation correction for PET/MR imaging. Based on PET emission data with time-of-flight information, iterative joint maximum likelihood reconstruction of attenuation and activity (MLAA) (2) has been used to perform attenuation correction and PET reconstruction jointly (3–6). MRI-based AC methods can be categorized into three classes: 1) atlas, 2) direct imaging/segmentation, and 3) machine learning methods. A detailed review of these AC methods before the introduction of the deep learning technique can be found in (7). Atlas-based methods estimated pseudo-CT images (pCT) with continuous HU for the target subject from population CT images (8–14). Direct imaging methods used DIXON, ultra-short echo (UTE), or zero echo time (ZTE) MRI without population data (15–25). Earlier segmentation-only methods used a single constant LAC for each of the 4 or 5 tissue classes, including air, lung, fat, tissue, and bone (15–18). Wollenweber et al. utilized continuous fat and water LAC values in whole-body PET/MR AC but without bone (26). Since bone has a wide range of CT HU, a single LAC for the entire bone class resulted in significant PET quantification errors. R2* was used for continuous LAC in bone (20–22). Leynes et al. used a two-segment piecewise linear model to convert ZTE MRI intensity to continuous CT HU in bone (27).

Early machine learning methods employed a Gaussian mixture model, support vector regression, or random forest methods (28–32). More recently, deep learning methods, a sub-class of machine learning, have been introduced to estimate pCT with improved performance compared to previous methods (33–40). Thus far, most deep learning-based AC methods have used MR signal intensities from T1-weighted, DIXON, UTE, or ZTE images as inputs (34–40). However, these MR signal intensities are in arbitrary units, have no direct association with electron density, and display considerable inter-subject and across-center variations. In contrast, quantitative MRI relaxation rates are related to tissue properties and may circumvent these limitations. Transverse relaxation rates, or R2*, display a non-linear relationship with CT Hounsfield unit (HU) in bone (21,22). More recently, we observed that longitudinal relaxation rates, or R1, derived from UTE imaging are associated with CT HU in bone and soft tissue (41). Given the advantages of deep learning and quantitative MRI, we hypothesized that inclusion of R1 maps as inputs to a deep learning model will produce highly accurate MR-derived pCT.

In addition to accuracy, a quantitative imaging method’s precision is also crucial for its translation to clinical trials and ultimately to clinical practice. To correctly interpret the longitudinal changes observed in PET/MR, test-retest repeatability of MR-based AC must be first established to distinguish true pathophysiological changes from measurement error due to methodology variability. The Radiological Society of North America has made extensive efforts to address this need through the formation of the Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) with a mission to “improve the value and practicality of quantitative imaging biomarkers by reducing variability across devices, sites, patients, and time” (42). However, studies assessing the direct contribution of variability in AC to PET/MR test-retest repeatability are scarce (43).

In this study, we proposed a 3D residual UNet (ResUNet) deep learning approach to derive pCT from MR. We assessed whether the use of R1 maps improved the PET AC accuracy. We evaluated the performance of four models with similar ResUNet structures but differing inputs: 1) Deep Learning T1-Enhanced Selection of Linear Attenuation coefficients (DL-TESLA) that included quantitative R1 maps as inputs; 2) Deep Learning UTE R2* (DL-UTER2*) that included quantitative R2* maps as inputs; 3) Deep Learning DIXON (DL-DIXON) that used vendor product DIXON in- and opp-phase images as inputs; and 4) Deep Learning T1-MPRAGE (DL-T1MPR) that used T1-MPRAGE images as the inputs. We further measured the test-retest repeatability of the DL-TESLA in a longitudinal study over three years.

2. Methods

2.1. Image acquisition

Imaging data were acquired from subjects (n=197) enrolled in an ongoing neuroimaging study of memory and aging with an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol and written informed consent. These subjects were separated into two sub-groups: Group A (n=174, median age [Interquartile range (IQR)]: 70 [64.25 75] years, 103 females) underwent single-time-point tri-modality imaging (PET/MR/CT), and Group B (n=23, median age [IQR]: 71 [68.5 76.5] years; 11 females) underwent tri-modality imaging at two time points (PET1/MR1/CT1 and PET2/MR2/CT2). In Group A, the median time [IQR] between CT and PET/MRI acquisition was 6 [−0.75 29.75] days. In Group B, the median time [IQR] between the same subject’s first and second PET/MR (PET1/MR1 vs. PET2/MR2) and first and second CT scans (CT1 vs. CT2) were 35 [31.5 39] and 37 [31.5 39] months, respectively.

PET and MR images were acquired using an integrated Biograph mMR PET/MRI system (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany), and CT images were acquired using a Biograph 40 PET/CT system (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). 18F-Florbetapir (Amyvid [Avid], Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) list mode PET data were acquired from all subjects using an injection dose (median [IQR]) of 373.7 [362.6 385.7] MBq. MR T1w images were acquired using a 3D magnetization–prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence with the following imaging parameters: TE/TR=2.95/2300 ms, TI=900 ms, number of partitions=176, matrix size =240×256×176, voxel size =1.05×1.05×1.2 mm3, acquisition time=5 min 11s. In- and opp-phase DIXON images were acquired using vendor-provided standard DIXON AC scan with the following imaging parameters: TR=3.6 ms, TE=1.23/2.46 ms, FA=10°, voxel size = 2.6×2.6×3.1 mm3, acquisition time=19sec, matrix size = 192×126×128. Dual flip angle and dual echo UTE (DUFA-DUTE) images were acquired using the following imaging parameters: TR=6.26 ms, TE1=0.07, TE2=2.46 ms, FA1=3°, FA2=15°, number of radial lines=18,000, matrix size = 192×192×192, voxel size=1.56×1.56×1.56 mm3, acquisition time=1 min 55s per flip angle. In the longitudinal cohort of Group B, 23 PET1/MR1 scans were acquired using different imaging parameters with a TR of 9 ms, a TE2 of 3.69 ms, and an FA2 of 25°. Images were acquired from August 2014 to September 2018. During the study period, the Siemens mMR underwent an upgrade from VB20P to VE11P. This VE11P includes software and scanner computer upgrades. 15 of 24 PET2/MR2 scans of Group B subjects were performed using a Syngo VE11P; all other PET/MR scans were acquired on a Syngo VB20P. The vendor provided product UTE sequence was modified to allow custom scan parameter selections. CT images were acquired at 120 kVp with voxel size=0.59×0.59×3.0 mm3 or 0.59×0.59×2.0 mm3.

Investigators can access the data by following the steps outlined at the Knight ADRC website at our institution (https://knightadrc.wustl.edu/Research/ResourceRequest.htm). Investigators will need to submit a research description. Upon the request’s approval by the Knight ADRC leadership committee, data access will be available. The authors are willing to share the code used in this study through research collaborations.

2.2. Image processing

All images were de-identified before transferred off-line for post-processing. The level-set segmentation tool in the Computational Morphometry Toolkit (CMTK) was employed to segment the head region from the background in MR and CT images (44). The FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool (FAST) tool (45) in the FSL Toolbox (FMRIB, Oxford, UK) was employed for bias field correction.

The DUFA-DUTE signal can be described by Equation 1 (46,47)

| (1) |

where FA is the flip angle, and M0 is the magnitude of the equilibrium magnetization. Quantitative R1 was computed using Equation 2 (47)

| (2) |

where S(FA1E1) and S(FA2E1) are the first echo of the first and second FA signal, respectively. Moreover, quantitative R2* can be computed using the dual echo UTE images. To avoid erroneous negative R2* due to ADC and gradient delays in the first echo UTE images, an empirical factor of 3 was used to scale the first echo followed by an exponential fitting to estimate R2* (21) (Equation 3).

| (3) |

where S(FA2E1) and S(FA2E2) are the first and second echo UTE images with the second FA.

For each subject in Group A, CT, DIXON and T1-MPRAGE images were co-registered to the UTE images using a 12 parameter affine registration with the FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT) in the FSL toolbox (48). Similarly, visit 2 MR and CT images were also aligned to visit 1 UTE images with the same registration toolkit. In CT images, bone and air were segmented with HU greater than 200 and less than −500, respectively (21,22,36). T1-MPRAGE images were segmented into gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and various brain regions using FreeSurfer 5.3 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) for regional analysis.

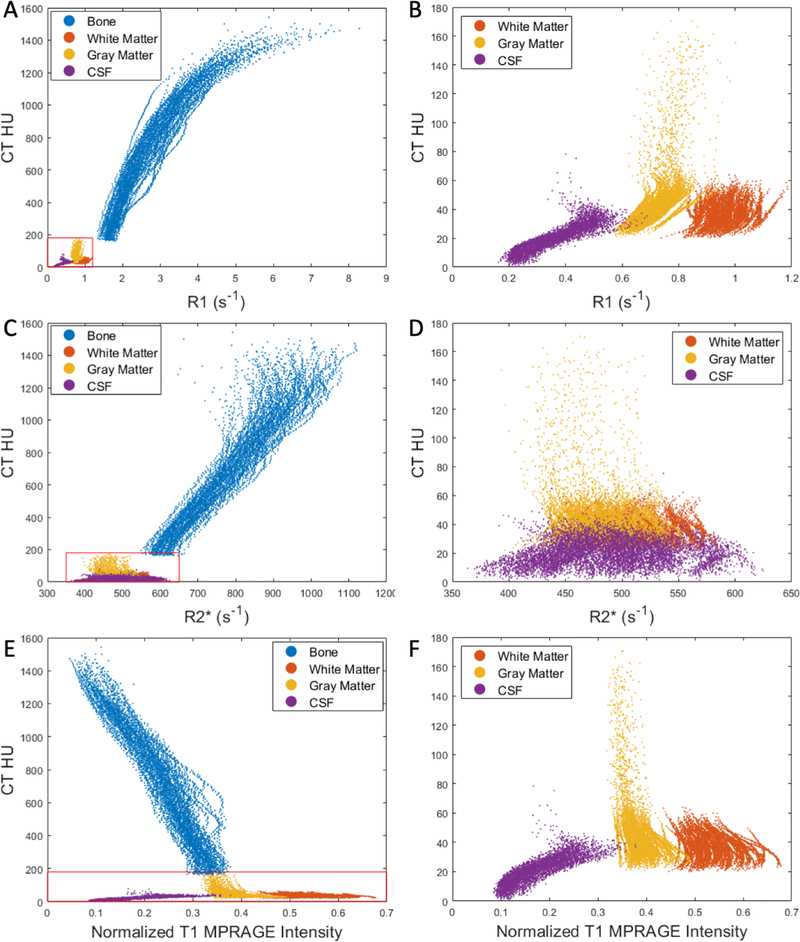

For each subject’s CT images, voxels within each tissue type (bone, gray matter, white matter, and CSF) were sorted into 100 bins based on their CT HU percentile. The mean HU of each bin was then plotted against the mean R1, R2* values or normalized T1-MPRAGE signal from the same voxels to evaluate the associations between R1, R2*, and T1-MPRAGE images with CT HU (Figure 1). In Figure 1, the T1-MPRAGE signal was normalized to a range of 0 – 1 using the 0.5th and 99.5th percentiles signal as the minimum and maximum, respectively.

Figure 1.

The relationship between UTE R1 (A), UTE R2* (C), or normalized T1 MPRAGE signal (E) and CT HU in bone and soft tissues. The magnified insets in the right panels (B, D, and F) provided an improved visualization of these relationships in soft tissues.

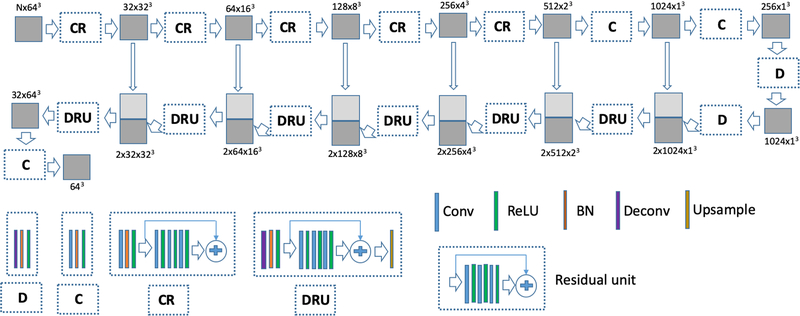

2.3. Deep learning networks for pCT estimation

Combining the advantages of the residual network (ResNet) (49) and UNet, the ResUNet structure has been used by Zhang et al. for 2D image processing (50). In this work, a 3D ResUNet was developed for pCT estimation (Figure 2). The 174 subjects in Group A were randomly divided into a training set (n = 72), validation set (n = 18), and testing set (n = 84). Before deep learning training, intensity normalizations were performed as normalized parameter = (parameter – mean)/(2×SD). A normalized parameter is half of the standard score. The means and standard deviations of CT HU or R1 and R2* were computed from all participants. The mean and standard deviation of T1-MPRAGE were computed for each participant. UTE FA1E1 and FA2E1, FA2E1 and FA2E2, and Dixon in- and opp-phase image pairs, the means and standard deviations were computed from both images for each participant.

Figure 2.

A 3D ResUNet consists of four main unit: the convolutional (C) and the convolutional residual (CR) units in the contraction path; the deconvolutional (D) and the deconvolutional/residual/upsampling (DRU) units in the expansion path. The C unit consists of convolution, batch normalization (BN), and the rectified linear unit (ReLU), while the CR unit consists of convolution, BN, ReLU, and the residual units. The D unit consists of deconvolution, BN, and ReLU, while DRU consists of deconvolution, BN, ReLU, the residual unit, and upsampling.

3D image patches of size 64×64×64 were used for training the ResUNet. The placement of a patch is determined by its center voxel. Patches were extracted without enforcing non-overlapping in the training. The 3D ResUNet consisting of seven layers in both the contraction and expansion paths was trained using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 10 (Figure 2). The objective function is the absolute difference (L1 difference) between the pCTs and ground-truth CTs. The learning rate was initialized at 10−3 and empirically decreased by half after every 50,000 batches. The convolution kernel sizes were 7,5,5,5,5,3 (stride=2 for down-sampling) and 1 in the contraction path from top to bottom, while the convolutional kernels used in the expansion path were 1, 3, 3, 7, 7, 9, 9 from the bottom to top. The activation function used in the contraction path was leaky ReLU (0.2), and the expansion path used regular ReLU. The total training parameters were 123,984,256 for DL-TESLA and DL-UTER2*, 123,973,280, and 123,962,304 for the DL-DIXON and DL-T1MPR, respectively. The parameters for all the convolutional elements were initialized as random values generated from a Gaussian distribution N(0, sqrt(2/n)) (n: number of parameters in the kernel), and the bias element was initialized as 0. The batch normalization element was initialized as the random value with Gaussian distribution N(1.0, 0.02) with bias initialized as 0.

The training and validation processes take approximately 12 days on a GeForce GTX 1080 Ti GPU card. The validation set (n = 18) was used to choose the model. The final network was then deployed to generate pCT in the remaining subjects in Group A (n = 84) for independent testing. Four networks with almost identical network structures but different inputs were tested: 1) DL-TESLA model with three channels of input: FA1E1, FA2E1 UTE images, and R1 maps; 2) DL-UTER2* model with three channels of input: FA2E1, FA2E2 UTE images, and R2* maps (22); 3) DL-DIXON model with two channel of inputs: in- and opp-phase DIXON images; and 4) DL-T1MPR model with one channel of input: T1-MPRAGE images. In Group B subjects with longitudinal data (n=23), DL-TESLA was applied to estimate pCTs in both visits. The trained networks were applied to 64×64×64 patches in moving windows with a step size of 16 pixels in each direction. Only the center 32×32×32 voxels of these patches were used to generate pCT. The pCT value at a given voxel was computed as the average value of the overlapped patches at this particular voxel. It takes ~40 seconds to apply and combine all the individual patches.

2.4. μ−Map formation and PET reconstruction

CTs and pCTs were converted to PET LAC values by piecewise linear scaling (1). The vendor-provided e7tools program (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN) was employed to reconstruct PET list mode data acquired from 50–70 minutes post-tracer injection using an ordinary Poisson ordered subset expectations maximization (OP-OSEM) algorithm with 3 iterations, 21 subsets, and a 5 mm Gaussian filter. In the test-retest repeatability analysis, AC maps computed using acquired CTs and DL-TESLA pCTs from visit 1 and visit 2 were used to reconstruct visit 1 PET data. A comparison between PET data from visit 1 and visit 2 was avoided due to potential PET signal changes resulting from pathophysiological progression over 3 years.

2.5. Accuracy analysis

The accuracy of the proposed models was evaluated using the acquired CT images as the gold-standard reference.

The whole brain mean absolute error (MAE) of pCT was computed as

| (4) |

The accuracies of the pCT in identifying bone and air were evaluated using the Dice coefficient as

| (5) |

PET images reconstructed using either the CT or the pCT-based μ-map were registered to the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) atlas using FLIRT and Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) (51,52).

Voxel based PET relative error was computed as

| (6) |

The percentages of the voxels in the brain with a relative PET error between ± 3% and ± 5% were calculated for each subject. Voxel based PET relative absolute error was computed as

| (7) |

PET AC accuracies were evaluated using mean relative error (MRE) and mean relative absolute error (MRAE) in whole brain and 10 FreeSurfer defined ROIs with high relevance to AD pathology (53).

2.6. Test-retest repeatability of PET AC

Test-retest repeatability analysis was performed on the standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) in the cerebrum (cerebral gray matter and cerebral white matter) and mean cortical (MC) region. SUVR in MC was calculated as the mean SUVR from four ROIs: the prefrontal cortex, precuneus, temporal cortex, and gyrus rectus regions (54). The test-retest repeatability of the proposed DL-TESLA and CT methods were assessed using the Bland and Altman method (55). The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the PET SUVR percent differences across subjects were calculated for PET images reconstructed using CT or MR AC. The within-subject coefficient of variation (wCV) was defined as . The 95% limits of repeatability (LOR) were defined as [mean–1.96×SD, mean+1.96×SD].

2.7. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB 2019a (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) and R 3.6.1 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Comparisons were performed using a paired t-test with the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control for false discovery rate (FDR) in multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Association between R1, R2*, and T1 with the CT Hounsfield unit

Figure 1 shows the R1, R2*, and normalized T1-MPRAGE signal and their corresponding CT HU in bone and soft tissues from all subjects. R1 values were much higher in bone than in soft tissues, and they were also distinct between gray matter, white matter, and CSF. Furthermore, R1 values were associated with CT HU in the bone and soft tissues (Figure 1A and B). R2* values were also higher in bone than in soft tissues. However, the separation between bone and soft tissue in R2* was not as distinct as in R1. R2* demonstrated substantial overlap among soft tissues (Figure 1C and D). Similar to our previous findings (21), R2* was associated with CT HU only in bone, but not in soft tissues. Finally, the T1-MPRAGE signal exhibited complete overlapping between bone and CSF as well as bone and gray matter (Figure 1E), while it could separate soft tissues (Figure 1F).

3.2. Training convergence

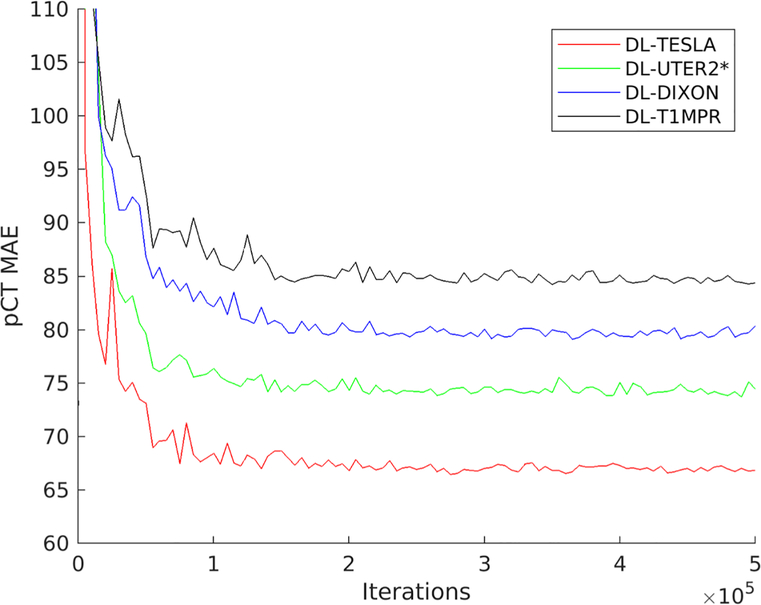

All four networks were trained using 500,000 iterations with 10 randomly extracted patches as one batch in each iteration. pCT MAEs for the validation subjects were plotted as a function of iterations in Figure 3. All networks reached a steady state after about 150,000 – 200,000 iterations with 1.5 – 2 million patches. DL-TESLA pCT had the smallest MAE, followed by DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR in the validation data sets.

Figure 3.

Mean absolute error (MAE) of pCT as a function of iterations using validation data sets

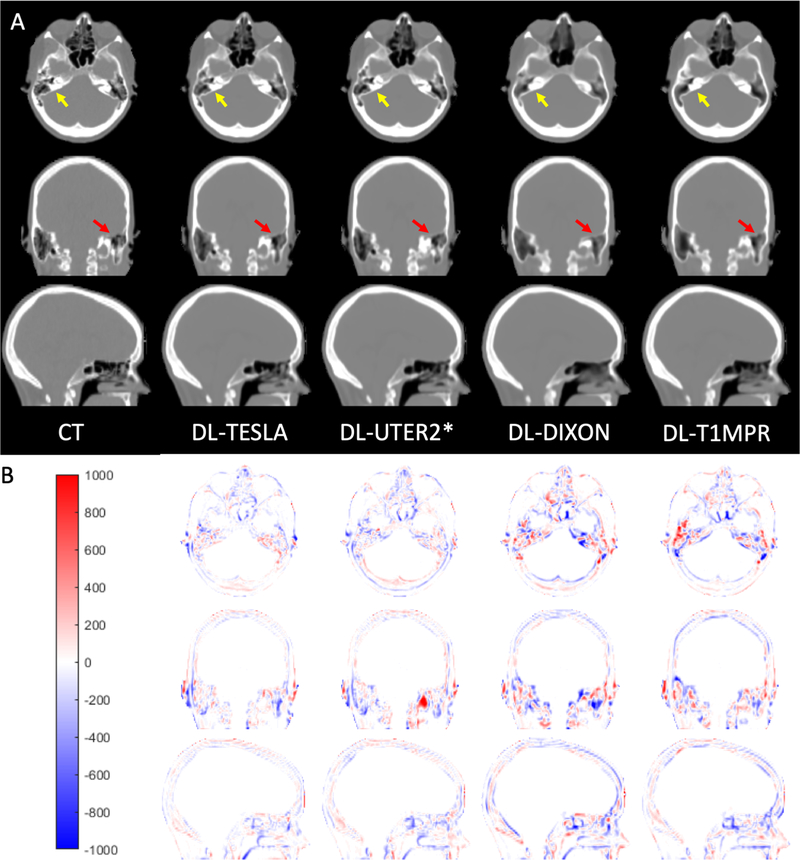

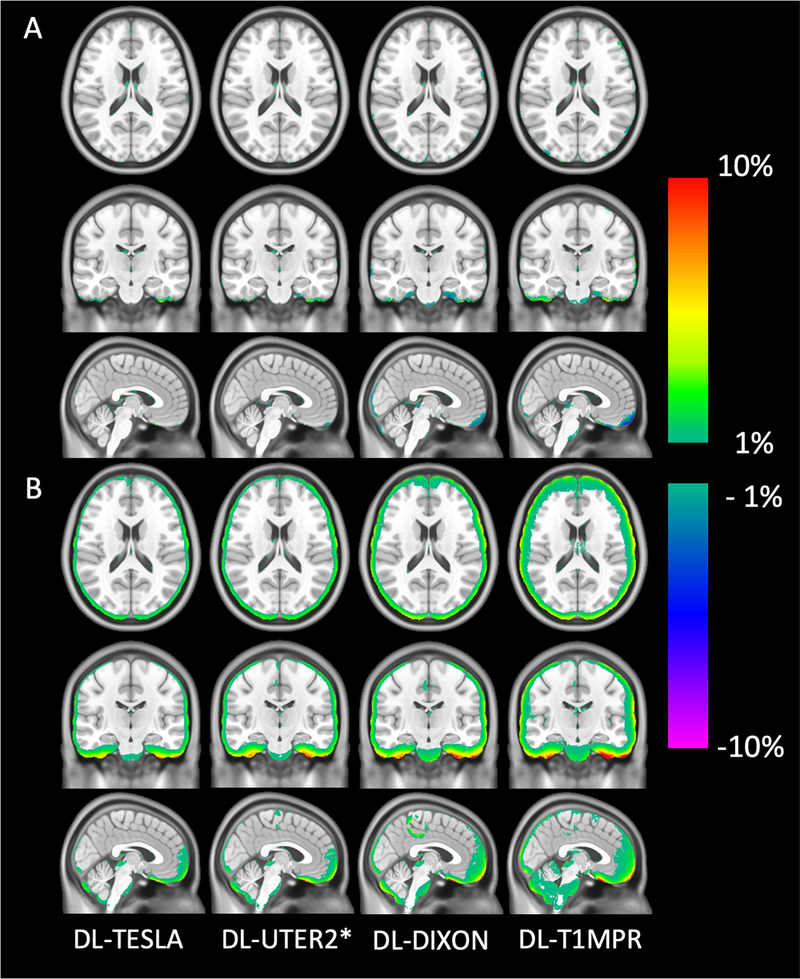

3.3. pCT accuracy

All networks (DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR) provided pCT maps closely resembling the gold standard reference CT (Figure 4). Upon close examination, we found that DL-TESLA exhibited the best performance in identifying fine details of bone and separating air and bone, followed by DL-UTER2*, and then DL-DIXON and DL-T1MPR. Furthermore, DL-TESLA displayed the smallest difference in CT HU between pCT and CT, followed by DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR.

Figure 4.

Representative CT (gold standard reference) and pCT maps (A) and CT HU difference maps between pCT and CT (B).

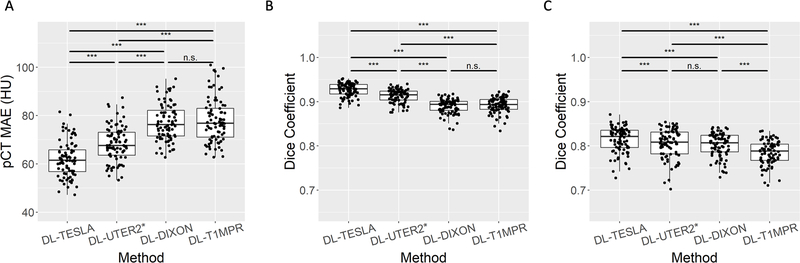

The pCT MAE in the testing data in Group A for DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR were summarized in Figure 5A and Table 1. DL-TESLA had a significantly lower MAE compared to DL-UTER2* (P<0.001), DL-DIXON (P<0.001), and DL-T1MPR (P<0.001), while DL-UTER2* had a significantly lower MAE than both DL-DIXON (P<0.001) and DL-T1MPR (P<0.001). The Dice coefficients between pCT and CT in bone and air (within head only) for DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR were given in Figure 5B and 5C, and Table 1. DL-TESLA had significantly higher Dice coefficients than all other networks in both bone and air.

Figure 5.

Mean absolute error (MAE) between pCT and CT (A). Dice coefficients between pCT and CT in bone (B) and air (C). The boxplots show the 25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles. (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, n.s.: not significant)

Table 1.

pCT and PET accuracy using pCT MAE, Dice coefficients in bone and air, PET MRE, and PET MRAE.

| pCT accuracy | PET accuracy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCT MAE (HU) | Dice (bone) | Dice (air) | PET MRE (%) | PET MRAE (%) | |

| DL-TESLA | 62.07±7.36 | 0.927±0.015 | 0.814±0.029 | 0.10±0.56 | 0.67±0.27 |

| DL-UTER2* | 68.26±7.30 | 0.913±0.015 | 0.805±0.033 | −0.06±0.61 | 0.78±0.26 |

| DL-DIXON | 77.18±7.52 | 0.890±0.016 | 0.802±0.027 | −0.15±0.63 | 0.89±0.29 |

| DL-MPRAGE | 78.00±9.05 | 0.892±0.018 | 0.785±0.026 | −0.20±0.82 | 1.09±0.41 |

3.4. Accuracy in PET AC

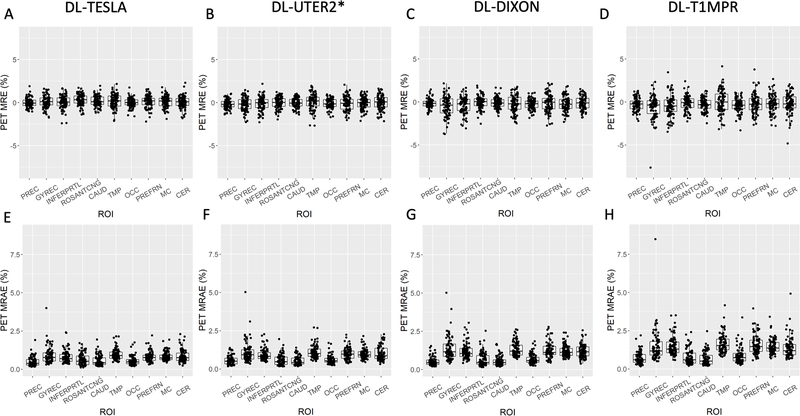

The accuracy of PET AC was evaluated using the testing subjects in Group A. The mean and standard deviation of the PET MRE across subjects was between −1% and 1% in most brain regions for all four models (Figure 6). The DL-TESLA model exhibited both the lowest PET relative error and standard deviation, followed by DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and then DL-T1MPR.

Figure 6.

Mean and standard deviation of PET relative error on the voxel basis across testing subjects in Group A (n = 84). The continuous CT AC method is used as the gold standard reference.

The whole-brain PET MREs were within ±0.20%, and the whole-brain PET MRAEs were <1.1% for all networks with less than 1% standard deviation (Table 1). DL-TESLA had the lowest whole brain PET MRAE (P<0.001), followed by DL-UTER2* (P<0.001) and DL-DIXON (P<0.001).

In the regional analysis (Figure 7), except in the ROSANTCNG and CAUD ROIs, DL-TESLA displayed a significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-UTER2* (P<0.05). Except in the PREC, ROSANTCNG, and CAUD ROIs, DL-TESLA exhibited a significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-DIXON (P<0.001). DL-TESLA exhibited a significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-T1MPR in all regions (P<0.001). Except in the PREC, ROSANTCNG, and CAUD ROIs, DL-UTER2* had significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-DIXON (P<0.05). DL-UTER2* had significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-T1MPR (P<0.01) in all ROIs. Except in the ROSANTCNG ROI, DL-DIXON had a significantly smaller PET MRAE than DL-T1MPR (P<0.05).

Figure 7.

PET MRE (upper row) and PET MRAE (lower row) in 10 ROIs. The boxplots show the 25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles. The ROIs included are Precuneus (PREC), Gyrusrectus (GYREC), Parietal cortex (INFERPRTL), Rostral anterior cingulate (ROSANTCNG), Caudate (CAUD), Temporal cortex (TMP), Occipital cortex (OCC), Prefrontal cortex (PREFRN), Cerebellum cortex (CER), “Mean cortical” region (MC).

The percentages of voxels with a PET MRE within ±3% were 98.0%±1.7%, 96.8%±2.0%, 95.0%±2.3%, and 93.6%±3.5% (Figure 8A) and percentage of voxels within ± 5% MRE were 99.5%±0.6%, 99.0%±1.0%, 98.1%±1.2%, and 97.3%±1.7% for DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, and DL-DIXON, DL-T1MPR, respectively (Figure 8B). Figure 8 showed that all four networks are robust across all testing participants. 98.8%, 98.8%, 96.2% and 92.9% of all testing participants had >90% brain voxels with a PET MRE within ±3% (Figure 8A and C), and 100%, 100%, 100% and 98.8% of all testing participants had >90% brain voxels with a PET MRE within ±5% using DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR networks, respectively (Figure 8B and D).

Figure 8.

Percentages of voxels with a PET relative error within ± 3% (A) and ± 5% (B). The boxplots show the 25th, 50th (median), and 75th percentiles. *** P<0.001. The number of patients as a function of various percentages of brain voxels within ± 3% (C) and ± 5% (D) MRE.

3.5. Test-retest repeatability of PET AC

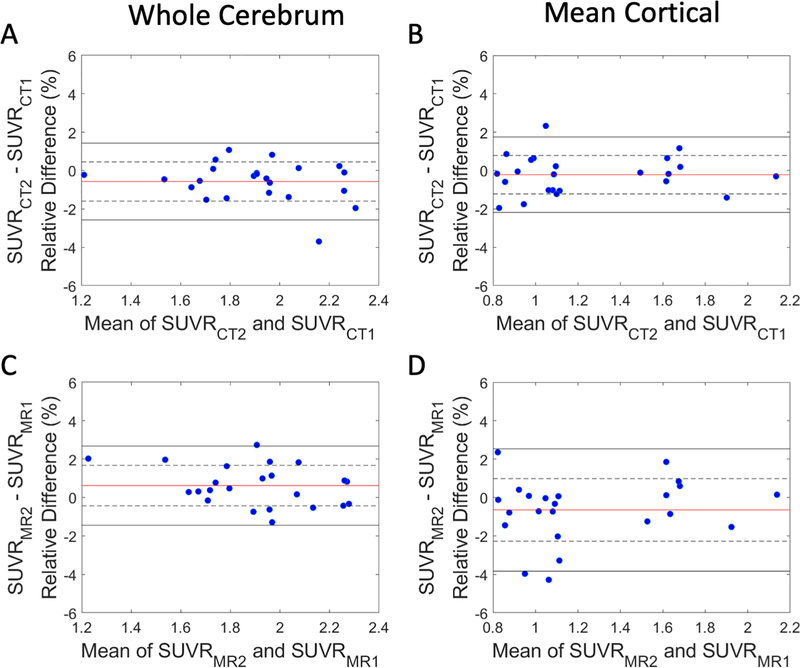

The test-retest repeatability between visits 1 and 2 PET SUVR difference using CT (upper row) and visit 1 and 2 DL-TESLA (lower row) estimated CT in the cerebrum and MC ROI were shown in the Bland-Altman plots in Figure 9. Mean SUVR differences, LOR, and wCV were summarized in Table 2. DL-TESLA had similar test-retest SUVR differences as CT in the cerebrum (DL-TESLA: 0.62%±1.05% vs. CT: −0.57%±1.02%) and MC (DL-TESLA: −0.65%±1.62% vs. CT: −0.22%±1.00%), respectively. In addition, DL-TESLA also had comparable wCV as CT in both cerebrum (DL-TESLA: 0.74% vs. CT: 0.72%) and MC (DL-TESLA: 1.15% vs. CT: 0.71%).

Figure 9.

Test-retest repeatability of PET using CT and DL-TESLA AC. Bland-Altman plots of the PET SUVR difference between two CT (A and B) and two DL-TESLA ACs (C and D) in cerebrum and MC. The red horizontal line, dotted black horizontal lines, and solid black horizontal lines represent the mean, ± SD, and ± 1.96×SD, respectively, of the test-retest SUVR differences.

Table 2.

Test-retest repeatability in cerebrum and MC. SUVR difference, limit of repeatability (LOR), and wCV are included.

| Region | Metrics | CT | DL-TESLA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrum | SUVR Difference (Mean ± SD) | −0.57% ± 1.02% | 0.62% ± 1.05% |

| LOR | [−2.58%, 1.43%] | [−1.45%, 2.68%] | |

| wCV | 0.72% | 0.74% | |

| Mean cortical region (MC) | SUVR Difference (Mean ± SD) | −0.22% ± 1.00% | −0.65% ± 1.62% |

| LOR | [−2.18%, 1.74%] | [−3.83%, 2.54%] | |

| wCV | 0.71% | 1.15% | |

4. Discussion

This study has developed 3D ResUNet approaches to derive pCT using MR parameters R1, R2* maps, DIXON, and T1 MPRAGE, respectively. The proposed networks achieved high pCT and PET accuracy. Since published deep learning based MR AC methods in literature were different from our approach in data, network structures, implementation, and accuracy metrics, we could only compare our methods with those using similar evaluation parameters. Dice coefficients of 0.88±0.01 (34), 0.8±0.04 (35), 0.80±0.07 (39), and 0.81±0.03 (36), and a Jaccard index of 0.53 (37) were previously reported in bone using other deep learning methods. In contrast, DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR produced Dice coefficients of 0.927±0.015, 0.913±0.015, 0.890±0.016, and 0.892±0.018 in bone, respectively. Arabi et al. observed a pCT MAE of 101±40 HU (39), while DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR had MAEs of 62.07±7.36 HU, 68.26±7.30 HU, 77.18±7.52 HU, and 78.0±9.05 HU, respectively. PET MREs of 3% (35) and 3.2±13.6% (39), and −0.2±5.6% (36) were previously reported, while DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR had PET MREs of 0.10±0.56%, 0.06±0.61%, −0.14±0.63%, and −0.20±0.82%, respectively. All four networks are robust across all participants (Figure 8). For example, 98.8%, 98.8%, 96.2%, and 92.9% of all testing participants had >90% brain voxels with a PET MRE within ±3% using DL-TESLA, DL-UTER2*, DL-DIXON, and DL-T1MPR, respectively (Figure 8A and C). Recently, Ladefoged et al. reported that 40% to 60% of their participants had >90% brain voxels with a PET MRE within ±3% (56).

The improved performance of the proposed method may be attributed to the following strengths of the study. First, a large number of patches were used in the training. Due to challenges in acquiring tri-modality PET, MRI, and CT images from the same participants, many published deep learning based methods used a small training sample size (<30) in end-to-end network training. Ladefoged et al. examined the impact of training data size by using 10, 50, 100, and 403 patients in end-to-end network training (56). They found that an increasing number of training data improved network performance. This study used multiple channel 3D volume images (16 slices x 192 voxels x 192 voxels) as network inputs in 100 epochs. It is not clear whether data augmentation was performed. In our study, a total of 5 million patches with a size of 64 × 64 × 64 were randomly sampled from 72 participants, and a large number of patches provided a benefit of data augmentation. The pCT MAE in Figure 3 converged after including 1.5–2 million patches, demonstrating the necessity of using a large number of patches in the training. Second, a lack of association between MR signal and CT HU leads to difficulties in accounting for CT HU variations in existing methods (35,36,39,56). Ladefoged et al. include UTE R2* in their UNet method (37), which has similar inputs as DL-UTER2*. However, R2* displayed a substantial overlap among soft tissues, while R1 is related to HU across all tissues (Figure 1). To further examine whether quantitative R1 in DL-TESLA may have any impacts on the network performance, we trained other networks using 1) only FA1E1, FA2E1 without quantitative R1 (DL-FA1E1- FA2E1), and 2) using quantitative R1 as the single input (DL-R1). The pCT MAE for DL-TESLA, DL-FA1E1-FA2E1, and DL-R1 were 62.06±7.36 HU, 87.46±11.81 HU, and 75.20±7.89, respectively. The inclusion of quantitative R1 maps in the DL-TESLA network significantly improved its performance. Quantitative R1 maps were computed based on a non-linear relationship of flip angle and signal (Equation 2) and needed to be included as a network input. DL-TESLA also outperformed DL-R1, suggesting that FA1E1, FA2E1 provided additional information to R1 maps in the DL-TESLA method. Finally, we tested another network by using all images, including FA1E1, FA1E2, FA2E1, FA2E2, R1, R2*, and T1MPRage, as network inputs. pCT MAE for these inputs network was 60.84±8.17 HU, slightly lower than that of the DL-TESLA (pCT MAE: 62.06±7.36 HU, P=0.017). However, this network is less practical because it requires a long acquisition time to obtain UTE and T1MPRage images. The inputs to the four networks were selected based on practical considerations. DL-TESLA does not need echo 2, which might allow a short TR in the future. DL-UTER2* only needs a dual echo UTE with one FA, which can be acquired using half of the time. DL-DIXON only needs the vendor-provided product MR AC scan, while DL-T1MPR uses a widely acquired T1MPRage.

Test-retest repeatability analysis is a critical prerequisite for longitudinal studies on disease progression or response to treatment. The QIBA profile for 18F-labeled amyloid PET tracers has a consensus claim: “Brain amyloid burden as reflected by the SUVR is measurable from 18F amyloid tracer PET with a within-subject coefficient of variation (wCV) of <=1.94%.” (57). Chen et al. found an SUVR test-retest difference of 0.65%±0.95% over 10 days in 9 subjects but did not compare the wCV with CT (43). To the best of our knowledge, our study may be the first one reporting similar to CT AC test-retest SUVR difference and wCV in a longitudinal clinical setting. Despite potential MR variations over three years, excellent repeatability was achieved by DL-TESLA well within the QIBA guideline. Thus, our findings support the use of DL-TESLA for PET/MR AC in longitudinal amyloid imaging.

This study has a few limitations. First, despite the large sample size (n = 197), all images were acquired from a single center in elderly subjects as part of an Alzheimer’s disease study at our institution. It is yet to be proved whether DL-TESLA may produce high PET/MR accuracy in younger subjects. DL-TESLA may likely account for potential age-dependent bone or tissue density differences by the inclusion of quantitative R1. Moreover, we only evaluated our methods using 18F-Florbetapir PET images. Its performance in 18F-FDG PET for oncological patients needs to be evaluated. A recent multi-center study (58) reported comparable performance of PET/MR AC methods across 18F-FDG, 11C-PiB, and 18F-Florbetapir (Supplementary Table 1 in (58)), suggesting PET tracers may not have a significant influence on PET/MR AC performance. Future studies using various PET tracers data from multi-center with a wide age range are needed for further evaluation. Second, the DUFA-DUTE is a dedicated PET AC scan, while DIXON is the vendor-provided product MR AC scan, and T1-MPRAGE is usually acquired for brain anatomical information. The acquisition time for the DUFA-DUTE data was 3 minutes 50 seconds. Strategies, including decreasing TR and the number of radial lines and, can be used to reduce acquisition time. The acquisition times are 19 seconds and 5 minutes 11 seconds for DIXON and T1MPRAGE, respectively. Though DL-DIXON is less accurate than both DL-TESLA and DL-UTER2*, it outperforms DL-T1MPR and many reported methods (58). We found the MRAE of the whole brain was 9.75±3.41% using the vendor DIXON AC method, which is a segmentation only approach without accounting for bone. In contrast, DL-DIXON had a whole-brain PET MRAEs of 0.89±0.28% using the same data. DL-DIXON is an excellent alternative option in the absence of a UTE scan. It may be adopted for whole-body PET/MR AC and applied to existing data across institutions. DL-T1MPR may be used as an option if both UTE and DIXON are not available. Third, we did not observe apparent motion or susceptibility artifacts in our data; therefore, the proposed networks’ robustness to these artifacts remained unknown. Since DL-TESLA uses 3D radial UTE with minimal echo time (TE1=0.07 second), it is robust to both motion and susceptibility artifacts. In contrast, DL-UTER2* may be subject to susceptibility artifacts. Due to background magnetic susceptibility, DIXON water/fat flipping may occur (58). Unlike the vendor product DIXON AC method, DL-DIXON did not use water/fat images but in- and opp-phase images as inputs. Since DIXON was acquired within 19 seconds, DL-DIXON is expected to be less sensitive to motion, while T1-MPRAGE is sensitive to motion artifacts due to its long acquisition time and Cartesian k-space sampling. Figure 8 demonstrated that all the proposed networks are robust across patients.

Most of our data were acquired using the Syngo VB20P software version. To apply our trained networks to data acquired using different software versions or different imaging parameters or from different vendors, a transfer learning using a small number of additional data may be needed (56). Moreover, similar to many published PET/MR AC methods, our study derived pCT images as the intermediate results before the LAC computation using a piece-wise bilinear conversion. LAC maps can be used as the training target. We chose pCT as the network output for 1) direct comparisons with published results; 2) potential use of this approach for electron density computation for radiation therapy planning. Recently, Liu et al. and Armanious et al. proposed deep learning methods to estimate pCT in brain and whole-body, respectively, from 18F-FDG PET images (59). Liu et al. reported a CT MAE of 111±16 HU and the overall PET MRAE of 1.74±0.94% in the brain (59). Armanious et al. found a PET MRE of − 0.8 ± 8.6% across all organs (range [− 30.7%, + 27.1%]) in whole-body (60). The PET based pCT estimation is likely to be tracer dependent, and it may provide options in PET alone scans.

In conclusion, DL-TESLA combines the patient specificity of quantitative R1 maps with the excellent learning capability of a state-of-the-art 3D ResUNet. It achieves highly accurate and repeatable PET/MR AC at both regional and voxel level while taking short processing time (~40 seconds) without the need for image registration. DL-TESLA is well-suited for longitudinal PET/MR clinical studies.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following funding sources: NIH 1R01NS082561; 1P30NS098577; 5R01CA212148; P50AG05681; P01AG026276; P01AG003991; UL1TR000448; 1P30NS098577 and Siemens Healthineers. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) provided the doses of 18F-Florbetapir and partially funded the cost of the PET scans. We thank Wilnellys Moore and Shirin Hatami for their technical assistance. This manuscript was edited by the Scientific Editing Service supported by the Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences at Washington University (NIH CTSA grant UL1TR002345).

Footnotes

Disclosure

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Carney JP, Townsend DW, Rappoport V, Bendriem B. Method for transforming CT images for attenuation correction in PET/CT imaging. Med Phys 2006;33(4):976–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuyts J, Dupont P, Stroobants S, Benninck R, Mortelmans L, Suetens P. Simultaneous maximum a posteriori reconstruction of attenuation and activity distributions from emission sinograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1999;18(5):393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boellaard R, Hofman MB, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA. Accurate PET/MR quantification using time of flight MLAA image reconstruction. Mol Imaging Biol 2014;16(4):469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezaei A, Defrise M, Nuyts J. ML-reconstruction for TOF-PET with simultaneous estimation of the attenuation factors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2014;33(7):1563–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit D, Ladefoged C, Rezaei A, Keller S, Andersen F, Hojgaard L, Hansen AE, Holm S, Nuyts J. PET/MR: improvement of the UTE mu-maps using modified MLAA. EJNMMI Phys 2015;2(Suppl 1):A58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezaei A, Deroose CM, Vahle T, Boada F, Nuyts J. Joint Reconstruction of Activity and Attenuation in Time-of-Flight PET: A Quantitative Analysis. J Nucl Med 2018;59(10):1630–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, An H. Attenuation Correction of PET/MR Imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2017;25(2):245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreibmann E, Nye JA, Schuster DM, Martin DR, Votaw J, Fox T. MR-based attenuation correction for hybrid PET-MR brain imaging systems using deformable image registration. Med Phys 2010;37(5):2101–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Juttukonda M, Su Y, Benzinger T, Rubin BG, Lee YZ, Lin W, Shen D, Lalush D, An H. Probabilistic Air Segmentation and Sparse Regression Estimated Pseudo CT for PET/MR Attenuation Correction. Radiology 2015;275(2):562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgos N, Cardoso MJ, Thielemans K, Modat M, Pedemonte S, Dickson J, Barnes A, Ahmed R, Mahoney CJ, Schott JM, Duncan JS, Atkinson D, Arridge SR, Hutton BF, Ourselin S. Attenuation correction synthesis for hybrid PET-MR scanners: application to brain studies. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2014;33(12):2332–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izquierdo-Garcia D, Hansen AE, Forster S, Benoit D, Schachoff S, Furst S, Chen KT, Chonde DB, Catana C. An SPM8-based approach for attenuation correction combining segmentation and nonrigid template formation: application to simultaneous PET/MR brain imaging. J Nucl Med 2014;55(11):1825–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreasen D, Van Leemput K, Hansen RH, Andersen JA, Edmund JM. Patch-based generation of a pseudo CT from conventional MRI sequences for MRI-only radiotherapy of the brain. Med Phys 2015;42(4):1596–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy S, Wang WT, Carass A, Prince JL, Butman JA, Pham DL. PET attenuation correction using synthetic CT from ultrashort echo-time MR imaging. J Nucl Med 2014;55(12):2071–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torrado-Carvajal A, Herraiz JL, Alcain E, Montemayor AS, Garcia-Canamaque L, Hernandez-Tamames JA, Rozenholc Y, Malpica N. Fast Patch-Based Pseudo-CT Synthesis from T1-Weighted MR Images for PET/MR Attenuation Correction in Brain Studies. J Nucl Med 2016;57(1):136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Moller A, Souvatzoglou M, Delso G, Bundschuh RA, Chefd’hotel C, Ziegler SI, Navab N, Schwaiger M, Nekolla SG. Tissue Classification as a Potential Approach for Attenuation Correction in Whole-Body PET/MRI: Evaluation with PET/CT Data. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2009;50(4):520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiber M, Martinez-Moller A, Souvatzoglou M, Holzapfel K, Pickhard A, Loffelbein D, Santi I, Rummeny EJ, Ziegler S, Schwaiger M, Nekolla SG, Beer AJ. Value of a Dixon-based MR/PET attenuation correction sequence for the localization and evaluation of PET-positive lesions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38(9):1691–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz V, Torres-Espallardo I, Renisch S, Hu Z, Ojha N, Bornert P, Perkuhn M, Niendorf T, Schafer WM, Brockmann H, Krohn T, Buhl A, Gunther RW, Mottaghy FM, Krombach GA. Automatic, three-segment, MR-based attenuation correction for whole-body PET/MR data. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38(1):138–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catana C, van der Kouwe A, Benner T, Michel CJ, Hamm M, Fenchel M, Fischl B, Rosen B, Schmand M, Sorensen AG. Toward implementing an MRI-based PET attenuation-correction method for neurologic studies on the MR-PET brain prototype. J Nucl Med 2010;51(9):1431–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berker Y, Franke J, Salomon A, Palmowski M, Donker HC, Temur Y, Mottaghy FM, Kuhl C, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Fayad ZA, Kiessling F, Schulz V. MRI-based attenuation correction for hybrid PET/MRI systems: a 4-class tissue segmentation technique using a combined ultrashort-echo-time/Dixon MRI sequence. J Nucl Med 2012;53(5):796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabello J, Lukas M, Forster S, Pyka T, Nekolla SG, Ziegler SI. MR-based attenuation correction using ultrashort-echo-time pulse sequences in dementia patients. J Nucl Med 2015;56(3):423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juttukonda MR, Mersereau BG, Chen Y, Su Y, Rubin BG, Benzinger TLS, Lalush DS, An H. MR-based attenuation correction for PET/MRI neurological studies with continuous-valued attenuation coefficients for bone through a conversion from R2* to CT-Hounsfield units. Neuroimage 2015;112:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladefoged C, Benoit D, Law I, Holm S, Hojgaard L, Hansen AE, Andersen FL. PET/MR attenuation correction in brain imaging using a continuous bone signal derived from UTE. EJNMMI Phys 2015;2(Suppl 1):A39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keereman V, Fierens Y, Broux T, De Deene Y, Lonneux M, Vandenberghe S. MRI-based attenuation correction for PET/MRI using ultrashort echo time sequences. J Nucl Med 2010;51(5):812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiesinger F, Sacolick LI, Menini A, Kaushik SS, Ahn S, Veit-Haibach P, Delso G, Shanbhag DD. Zero TE MR bone imaging in the head. Magn Reson Med 2016;75(1):107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekine T, Ter Voert EE, Warnock G, Buck A, Huellner MW, Veit-Haibach P, Delso G. Clinical evaluation of ZTE attenuation correction for brain FDG-PET/MR imaging-comparison with atlas attenuation correction. J Nucl Med 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wollenweber SD, Ambwani S, Lonn AHR, Shanbhag DD, Thiruvenkadam S, Kaushik S, Mullick R, Qian H, Delso G, Wiesinger F. Comparison of 4-Class and Continuous Fat/Water Methods for Whole-Body, MR-Based PET Attenuation Correction. Ieee T Nucl Sci 2013;60(5):3391–3398. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leynes AP, Yang J, Shanbhag DD, Kaushik SS, Seo Y, Hope TA, Wiesinger F, Larson PE. Hybrid ZTE/Dixon MR-based attenuation correction for quantitative uptake estimation of pelvic lesions in PET/MRI. Med Phys 2017;44(3):902–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofmann M, Steinke F, Scheel V, Charpiat G, Farquhar J, Aschoff P, Brady M, Scholkopf B, Pichler BJ. MRI-based attenuation correction for PET/MRI: a novel approach combining pattern recognition and atlas registration. J Nucl Med 2008;49(11):1875–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson A, Garpebring A, Asklund T, Nyholm T. CT substitutes derived from MR images reconstructed with parallel imaging. Med Phys 2014;41(8):082302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson A, Johansson A, Axelsson J, Nyholm T, Asklund T, Riklund K, Karlsson M. Evaluation of an attenuation correction method for PET/MR imaging of the head based on substitute CT images. Magn Reson Mater Phy 2013;26(1):127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navalpakkam BK, Braun H, Kuwert T, Quick HH. Magnetic resonance-based attenuation correction for PET/MR hybrid imaging using continuous valued attenuation maps. Invest Radiol 2013;48(5):323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huynh T, Gao Y, Kang J, Wang L, Zhang P, Lian J, Shen D, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Estimating CT Image From MRI Data Using Structured Random Forest and Auto-Context Model. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2016;35(1):174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu F, Jang H, Kijowski R, Bradshaw T, McMillan AB. Deep Learning MR Imaging-based Attenuation Correction for PET/MR Imaging. Radiology 2018;286(2):676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang H, Liu F, Zhao G, Bradshaw T, McMillan AB. Technical Note: Deep learning based MRAC using rapid ultrashort echo time imaging. Med Phys 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong K, Yang J, Kim K, El Fakhri G, Seo Y, Li Q. Attenuation correction for brain PET imaging using deep neural network based on Dixon and ZTE MR images. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2018;63(12):125011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanc-Durand P, Khalife M, Sgard B, Kaushik S, Soret M, Tiss A, El Fakhri G, Habert MO, Wiesinger F, Kas A. Attenuation correction using 3D deep convolutional neural network for brain 18F-FDG PET/MR: Comparison with Atlas, ZTE and CT based attenuation correction. PLoS One 2019;14(10):e0223141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladefoged CN, Marner L, Hindsholm A, Law I, Højgaard L, Andersen FL. Deep learning based attenuation correction of PET/MRI in pediatric brain tumor patients: evaluation in a clinical setting. Frontiers in neuroscience 2019;12:1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nie D, Trullo R, Lian J, Wang L, Petitjean C, Ruan S, Wang Q, Shen D. Medical Image Synthesis with Deep Convolutional Adversarial Networks. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2018;65(12):2720–2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arabi H, Zeng G, Zheng G, Zaidi H. Novel adversarial semantic structure deep learning for MRI-guided attenuation correction in brain PET/MRI. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2019;46(13):2746–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han X. MR-based synthetic CT generation using a deep convolutional neural network method. Med Phys 2017;44(4):1408–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juttukonda MR, Mersereau BG, Su Y, Benzinger TLS, Lalush DS, An H. T1-Enhanced Segmentation and Selection of Linear Attenuation Coefficients for PET/MRI Attenuation Correction in Head/neck Applications. 2016; Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson EF. Quantitative Imaging: The Translation from Research Tool to Clinical Practice. Radiology 2018;286(2):499–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen KT, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Poynton CB, Chonde DB, Catana C. On the accuracy and reproducibility of a novel probabilistic atlas-based generation for calculation of head attenuation maps on integrated PET/MR scanners. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017;44(3):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otsu M. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Man Cybern 1979(9):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2001;20(1):45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buxton RB, Edelman RR, Rosen BR, Wismer GL, Brady TJ. Contrast in Rapid MR Imaging: T1− and T2-Weighted Imaging. Journal of computer assisted tomography 1987;11(1):7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fram EK, Herfkens RJ, Johnson GA, Glover GH, Karis JP, Shimakawa A, Perkins TG, Pelc NJ. Rapid calculation of T1 using variable flip angle gradient refocused imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging 1987;5(3):201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Medical image analysis 2001;5(2):143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He K, Zhang X, Ren S. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2016:770–778. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang ZX, Liu QJ, Wang YH. Road Extraction by Deep Residual U-Net. Ieee Geosci Remote S 2018;15(5):749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage 2011;54(3):2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fonov VS, Evans AC, McKinstry RC, Almli C, Collins D. Unbiased nonlinear average age-appropriate brain templates from birth to adulthood. NeuroImage 2009(47):S102. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, Zhou G, Snyder AZ, Marcus DS, Blazey TM, Christensen JJ, Vora S, Morris JC. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with freesurfer ROIs. PloS one 2013;8(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mintun M, Larossa G, Sheline Y, Dence C, Lee SY, Mach R, Klunk W, Mathis C, DeKosky S, Morris J. [11C] PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2006;67(3):446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bland JM, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The lancet 1986;327(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ladefoged CN, Hansen AE, Henriksen OM, Bruun FJ, Eikenes L, Oen SK, Karlberg A, Hojgaard L, Law I, Andersen FL. AI-driven attenuation correction for brain PET/MRI: Clinical evaluation of a dementia cohort and importance of the training group size. Neuroimage 2020;222:117221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.PET-Amyloid Biomarker Committee. 18F-labeled PET tracers targeting Amyloid as an Imaging Biomarker. Consensus version. Volume 20202018. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ladefoged CN, Law I, Anazodo U, St Lawrence K, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Catana C, Burgos N, Cardoso MJ, Ourselin S, Hutton B, Merida I, Costes N, Hammers A, Benoit D, Holm S, Juttukonda M, An H, Cabello J, Lukas M, Nekolla S, Ziegler S, Fenchel M, Jakoby B, Casey ME, Benzinger T, Hojgaard L, Hansen AE, Andersen FL. A multi-centre evaluation of eleven clinically feasible brain PET/MRI attenuation correction techniques using a large cohort of patients. Neuroimage 2017;147:346–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu F, Jang H, Kijowski R, Zhao G, Bradshaw T, McMillan AB. A deep learning approach for (18)F-FDG PET attenuation correction. EJNMMI Phys 2018;5(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armanious K, Hepp T, Kustner T, Dittmann H, Nikolaou K, La Fougere C, Yang B, Gatidis S. Independent attenuation correction of whole body [(18)F]FDG-PET using a deep learning approach with Generative Adversarial Networks. EJNMMI Res 2020;10(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]