Cell wall-associated polysaccharides of bacteria are involved in various physiological characteristics. Recent studies demonstrated that the cell wall-associated polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis is required for susceptibility to bactericidal antibiotic agents.

KEYWORDS: Enterococcus, polysaccharide, galactose, antibiotic resistance, bacteriocin, morphogenesis, UDP-glucose phosphorylase, imaging, beta-lactam, cell death, Enterococcus faecalis, beta-lactams, cell morphology

ABSTRACT

Enterococcal plasmid-encoded bacteriolysin Bac41 is a selective antimicrobial system that is considered to provide a competitive advantage to Enterococcus faecalis cells that carry the Bac41-coding plasmid. The Bac41 effector consists of the secreted proteins BacL1 and BacA, which attack the cell wall of the target E. faecalis cell to induce bacteriolysis. Here, we demonstrated that galU, which encodes UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase, is involved in susceptibility to the Bac41 system in E. faecalis. Spontaneous mutants that developed resistance to the antimicrobial effects of BacL1 and BacA were revealed to carry a truncation deletion of the C-terminal amino acid (aa) region 288 to 298 of the translated GalU protein. This truncation resulted in the depletion of UDP-glucose, leading to a failure to utilize galactose and produce the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen (EPA), which is expressed abundantly on the cell surface of E. faecalis. This cell surface composition defect that resulted from galU or EPA-specific genes caused an abnormal cell morphology, with impaired polarity during cell division and alterations of the limited localization of BacL1. Interestingly, these mutants had reduced susceptibility to beta-lactams besides Bac41, despite their increased susceptibility to other bacteriostatic antimicrobial agents and chemical detergents. These data suggest that a complex mechanism of action underlies lytic killing, as exogenous bacteriolysis induced by lytic bacteriocins or beta-lactams requires an intact cell physiology in E. faecalis.

IMPORTANCE Cell wall-associated polysaccharides of bacteria are involved in various physiological characteristics. Recent studies demonstrated that the cell wall-associated polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis is required for susceptibility to bactericidal antibiotic agents. Here, we demonstrated that a galU mutation resulted in resistance to the enterococcal lytic bacteriocin Bac41. The galU homologue is reported to be essential for the biosynthesis of species-specific cell wall-associated polysaccharides in other Firmicutes. In E. faecalis, the galU mutant lost the E. faecalis-specific cell wall-associated polysaccharide EPA (enterococcal polysaccharide antigen). The mutant also displayed reduced susceptibility to antibacterial agents and an abnormal cell morphology. We demonstrated here that galU was essential for EPA biosynthesis in E. faecalis, and EPA production might underlie susceptibility to lytic bacteriocin and antibiotic agents by undefined mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive opportunistic pathogen that is a causative agent of several infectious diseases, such as urinary infections, bacteremia, endocarditis, and others (1). This organism belongs to the lactic acid bacteria and is a microbial resource that produces various bacteriocins (2). Bacteriocins are antimicrobial proteins or peptides that are produced by bacteria and are considered to play a role in bacterial competition within the microbial ecological environment (3). Gram-positive bacterial bacteriocins are classified according to their structures or synthetic pathways (4). Class I bacteriocins, which are referred to as lantibiotics, are heat-stable peptides that contain nonproteinogenic amino acids modified by posttranslational modifications (5). Class II bacteriocins are also heat-stable peptides, but they are synthesized without any posttranslational modification (6). In E. faecalis, beta-hemolysin/bacteriocin (cytolysin), which is the major virulence factor, and enterocin W belong to the class I bacteriocins (7–9). On the other hand, most enterococcal bacteriocins, including Bac21, Bac31, Bac32, Bac43, Bac51, and others, belong to the class II peptides (6, 8, 10–15). Class III bacteriocins are proteinaceous heat-liable bacteriocins that differ from the class I or II peptides. Therefore, bacteriocins of this class are often referred to as bacteriolysins. Two enterococcal bacteriolysins, enterolysin A and Bac41, have been identified to date (16, 17).

The bacteriolysin Bac41 was originally found in the conjugative plasmid pYI14 of E. faecalis clinical strain YI14 and is widely distributed among clinical isolates, including vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) (17–19). The activity of this bacteriocin is specific toward E. faecalis and not other Enterococcus or bacterial species (20). The genetic element of Bac41 consists of bacL1, bacL2, bacA, and bacI. BacL1 and BacA are the effectors responsible for the antimicrobial activity of this bacteriocin against E. faecalis. BacL2 is involved in the expression of antimicrobial activity as a transcriptional positive regulator (17, 21). BacI is required for the self-protection of Bac41-producing E. faecalis cells from the antimicrobial activity of BacL1 and BacA. Both the BacL1 and BacA molecules contain conserved peptidoglycan hydrolase domains, suggesting that these molecules attack the target’s cell wall (17). Endopeptidase activity against the E. faecalis cell wall has been detected experimentally in BacL1 (22). However, the peptidoglycan-degrading activity of BacA has not been detected, and the enzymatic function of this molecule remains unknown. BacL1 binds specifically to the nascent cell wall or to cell division loci via its C-terminal SH3 repeat domain (20). The resulting cell growth inhibition protects against the binding of BacL1 and markedly reduces susceptibility to bacterial killing by Bac41 effectors. It is important to note that the BacL1 cell wall degradation process is essential but not sufficient to kill the bacteria; bacteriolysis requires the additional action of the undefined BacA.

In this paper, we isolated a spontaneous mutant of E. faecalis that exhibited resistance to the toxicity of BacL1 and BacA to further understand the bacteriolytic mechanism of the Bac41 system. Genomic variant analysis showed that an intact galU gene was essential for susceptibility to BacL1 and BacA. Furthermore, we demonstrated that galU is also essential for galactose fermentation and for the synthesis of the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen, which is required for maintaining normal cell morphology and for susceptibility to antimicrobial agents.

RESULTS

Inactivation of galU results in decreased susceptibility to Bac41.

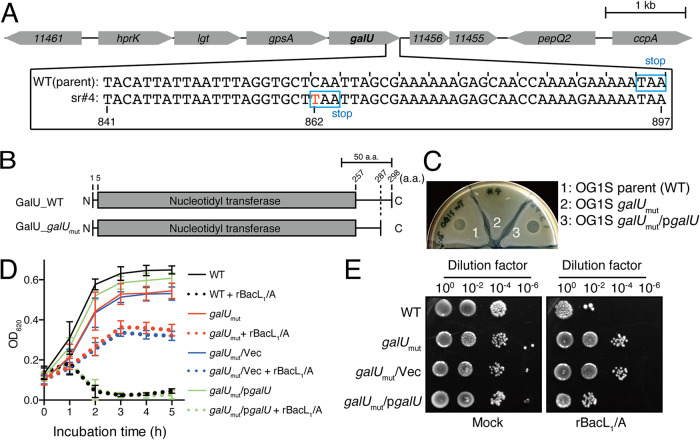

To identify the target E. faecalis cell factor(s) involved in Bac41-mediated bacterial killing, spontaneous mutants that are resistant to the Bac41 effectors BacL1 and BacA were obtained. We carried out a soft-agar bacteriocin experiment in which the susceptible bacterial strain E. faecalis OG1S was inoculated into and grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) agar (0.75%), and a mixture of recombinant BacL1 and BacA proteins (25 ng of each protein) was spotted onto the E. faecalis-containing THB agar. After incubation at 37°C overnight, a clear growth inhibition zone was formed in the area where the recombinant proteins had been spotted (22). Notably, additional incubation resulted in the occurrence of small colonies within the growth-inhibitory zone. These colonies were considered spontaneously resistant mutants, so we isolated these colonies as candidates that may carry a genetic mutation related to bacterial killing by Bac41. To identify the genetic mutation that caused this spontaneous Bac41 resistance, we performed whole-genome sequencing and a variant analysis of the mutant strains. The contigs from the genome sequence of the parent strain E. faecalis OG1S and the isogenic mutant were obtained by next-generation sequencing and were mapped onto the reference strain E. faecalis OG1RF (accession no. NC_017316). One of these spontaneous mutants, sr#4, carried the point mutation C862T within the galU (annotated as cap4C in the OG1RF genomic information) coding sequence (Fig. 1A). The wild-type (WT) galU gene consists of 897 bp, and its translated product GalU is 298 amino acids (aa) in length. The mutation found in sr#4 was a nonsense mutation and resulted in the truncation of the GalU protein by a C-terminal deletion of aa 288 to 298 (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Genetic mutation found in the strain spontaneously resistant to the antimicrobial activity of Bac41. (A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the galU (OG1RF_11457; Gene ID 12287400) genes of the E. faecalis OG1S parent strain (upper) and the OG1S isogenic mutant strain (sr#4) that spontaneously acquired resistance to the antimicrobial activity of Bac41 (lower). Scale bar, 1 kb. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the translation products of the galU genes of the E. faecalis OG1S parent strain (upper) and the OG1S isogenic mutant strain (lower). Scale bar, 50 aa. (C) A mixture of recombinant BacL1-His and BacA-His proteins (25 ng each) was spotted onto THB soft agar (0.75%) containing the indicator strain E. faecalis OG1S (parent, 1), the spontaneously resistant strain with the galU mutation (galUmut, 2), and the galUmut complemented strain via the transexpression of wild-type GalU from the pgalU plasmid (galUmut/pgalU, 3). The plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the formation of halos was evaluated. (D) Overnight cultures of E. faecalis strains, including OG1S (WT), the galU mutant (galUmut), the vector control strain of galUmut (galUmut/Vec), and the complemented galUmut strain (galUmut/pgalU), were inoculated into fresh THB broth at a 5-fold dilution. A mixture of recombinant BacL1-His (5 μg/ml) and BacA-His (5 μg/ml) was added to the bacterial suspension and incubated at 37°C. The turbidity was monitored during the incubation period. The data for each case are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD) (error bars) from three independent experiments. (E) The E. faecalis strains were treated with rBacL1 and rBacA (5 μg/ml each) at 37°C for 4 h, as described for panel D. The bacterial suspensions were serially diluted 100-fold with fresh THB and then spotted onto a THB agar plate, followed by incubation overnight. Colony formation was evaluated as a measure of bacterial viability.

Complementation via the introduction of the intact galU gene carried by the expression vector pgalU restored the mutant strain’s susceptibility to Bac41 activity to the level of the parent strain (Fig. 1C). In addition, a liquid-phase bacteriolytic assay also demonstrated that the spontaneous mutant (referred to as galUmut here) could still grow in the presence of recombinant BacL1 (rBacL1) and BacA (rBacA), while the wild-type strain underwent considerable lysis (Fig. 1D). The complementation of the galU mutation via the expression of intact galU in trans (galUmut/pgalU) but not the control vector (galUmut/Vec) restored the strain’s susceptibility to bacteriolysis to the same degree as the wild-type strain. The viability of the galUmut and galUmut/Vec strains exhibited a >100-fold increase in compared to the wild-type and galUmut/pgalU strains after treatment with rBacL1 and rBacA (5 μg/ml each) for 4 h (Fig. 1E). Therefore, these results strongly demonstrated that the truncated mutation of the galU gene resulted in resistance to the antimicrobial activity of Bac41.

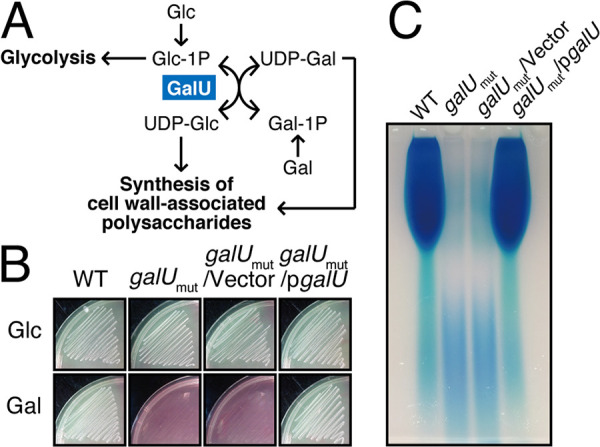

The enterococcal galU is essential for the fermentation of galactose and the production of cell wall-associated polysaccharides.

The galU gene encodes UDP-glucose phosphorylase (UDPG::PP; EC 2.7.7.9), which generates UDP-glucose from a UTP molecule and glucose-1-phosphate (23). The homologues of this gene are universally conserved not only in prokaryotes but also in eukaryotes (24). It has been reported extensively that among both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, this enzymatic activity of GalU is essential for the carbohydrate metabolism that is involved in multiple bacterial physiological pathways; however, the precise role of GalU in E. faecalis remains undefined. UDP-glucose, which is the product of GalU, is utilized for galactose fermentation via the Leloir pathway in lactic acid bacteria (Fig. 2A) (25). We tested whether the strain that possesses an inactivated galU has the ability to undergo galactose fermentation (Fig. 2B). The wild-type strain and the complemented strain had the ability to ferment both glucose and galactose. In contrast, the galU mutant strain and the galUmut/Vec strain could utilize glucose but not galactose. In addition, the in-frame deletion mutants of galU that were constructed via site-directed mutagenesis also failed to utilize galactose in the two different lineages OG1RF and FA2-2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These data clearly indicated that GalU produces UDP-glucose in E. faecalis and in other species and suggested that the C-terminal truncation of GalU in the galUmut strain resulted in the complete loss of its UDPG::PP activity.

FIG 2.

galU is essential for galactose fermentation and cell surface polysaccharide production. (A) The Leloir pathway of galactose metabolism is illustrated. GalU generates UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc) from glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1P) and ATP. (B) The E. faecalis wild-type, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains were grown in HI agar medium supplemented with phenol red as a pH indicator and glucose (Glc) or galactose (Gal) as the fermentation source. (C) The E. faecalis wild-type, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains were grown in THB broth supplemented with glucose, and the cell wall-associated polysaccharides were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting polysaccharides were separated via 10% acrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by staining with the Stains-All reagent.

In addition to its role in galactose fermentation, GalU and its product, UDP-glucose, are essential for the biosynthesis of bacterial glycopolymers, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), teichoic acid, and capsular polysaccharide, which are important structural components that determine the properties of the bacterial cell surface (26). For example, in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which has more than 90 capsular variants, GalU is essential for the biosynthesis of various types of capsular polysaccharide (27). The cell surface polysaccharide profiles of E. faecalis strains were previously demonstrated (28, 29). To investigate the effect of the galU mutation on capsular polysaccharide synthesis in enterococci, cell wall-associated polysaccharides were prepared from the E. faecalis WT, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis, followed by visualization with cationic staining (Fig. 2C). The most abundant band, which corresponds to the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen (EPA), was observed in the wild-type OG1S and galUmut/pgalU strains. In contrast, the EPA had completely disappeared from the galUmut and galUmut/vector strains. This result strongly suggested that the galU gene is essential for EPA production in E. faecalis.

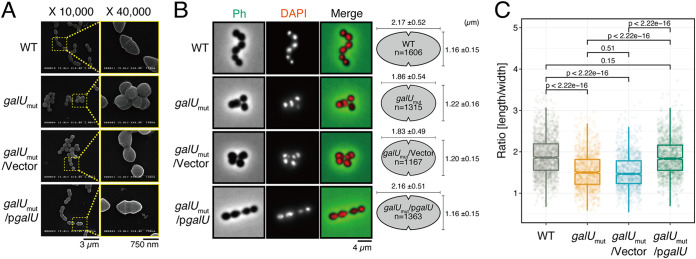

Previous studies identified the specific EPA biosynthesis gene cluster epaA-R (28, 30, 31). Several epa gene mutants with altered EPA composition, such as mutants of epaA, -B, -E, -M, -N, -I, -X, or -O, displayed a pleiotropic phenotype that included abnormal cell morphology, defective biofilm formation, and increased susceptibility to antimicrobial agents and phages as well as other phenotypes (31, 32). We investigated the effect of galU inactivation on cell morphology. E. faecalis is an ovococcal bacterium with an ellipsoid cell shape, and its size is approximately 2 μm by 1 μm. Observation under a scanning electron microscope revealed that the galUmut strain showed an abnormal cell morphology with a rounded cell shape and a slightly larger size (Fig. 3A). Fluorescent imaging using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), which is a fluorescence probe for DNA, revealed that abnormal multinucleated cells were present in the galUmut population (Fig. 3B). The galUmut/pgalU complemented strain but not the galUmut/Vec control vector strain showed the same morphological phenotype as the wild-type strain. To characterize the cell shape in detail, we measured the cell length and width for individual cells on the phase-contrast images by microbial image analysis using the software Oufti (33) (Fig. 3B, right). The cell lengths of galUmut (1.86 ± 0.54 μm) and galUmut/Vec (1.83 ± 0.49 μm) strains were shorter than those of wild-type (2.17 ± 0.52 μm) and galUmut/pgalU (2.16 ± 0.51 μm) strains. On the other hand, the cell width of galUmut (1.22 ± 0.16 μm) and galUmut/Vec (1.20 ± 0.15 μm) strains were even longer than those of wild-type (1.16 ± 0.15 μm) and galUmut/pgalU (1.16 ± 0.15 μm) strains. To statistically analyze the alteration of cell shape, we calculated and compared the ratio of cell length against width among the strains (Fig. 3C). The length/width ratio of galUmut and galUmut/Vec strains were significantly changed from those of wild-type and galUmut/pgalU strains. These observations suggested that the truncation of the galU gene leads to a marked morphological defect.

FIG 3.

galU is essential for maintaining cell morphology. (A) The E. faecalis wild-type, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains were grown on cover glasses, followed by chemical fixation. The samples were subjected to osmium coating and analyzed under the scanning electron microscope. Scale bars, 3 μm (left) and 750 nm (right). (B) Overnight cultures of the E. faecalis wild-type, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains were diluted 5-fold with fresh THB broth and incubated, chemically fixed, and mounted with DAPI for DNA visualization (red), followed by analysis via fluorescence microscopy. Phase contrast (Ph) is pseudocolored (green) in the merged image. Scale bar, 4 μm. The panel on the right represents mean ± SD individual cell length and width; at least >1,000 cells were counted for each strain. (C) Cellular length/width ratio of single cells, calculated based on phase-contrast images in panel B, were plotted. t test was used for statistical analysis.

The loss of cell wall-associated EPA does not block targeting and cell wall degradation of BacL1 to the cell wall.

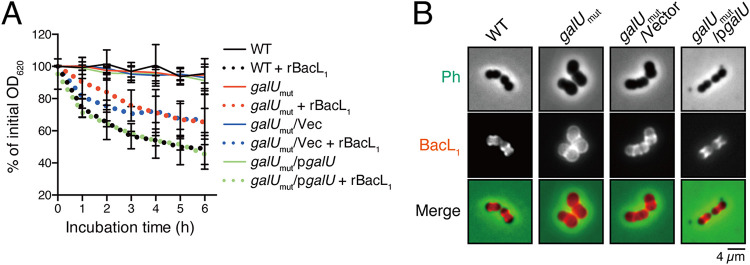

We previously reported that the peptidoglycan degradation activity of BacL1 is not sufficient but still essential for Bac41-mediated bacterial killing (22). Note that although BacA is an essential effector in bacteriolysis activity of the Bac41 system, its function has not been detectable in our previous experiment settings, such as cell wall degradation (22) or cell surface binding assay (20). Therefore, here we used BacL1 for further investigation. We examined whether the observed resistance to Bac41 activity in the galUmut mutant results from decreased susceptibility of the cell wall to BacL1. Cell wall fractions prepared from the wild-type OG1S strain and the galUmut, galUmut/Vec, or galUmut/pgalU strain were treated with recombinant BacL1, followed by incubation at 37°C (Fig. 4A). The cell walls from the parent strain and the complemented strain were degraded to 52.8% and 51.9% of the initial amount after 6 h of incubation, respectively. In contrast, the galUmut and galUmut/Vec-derived cell walls were also degraded to 70.6% and 68.5%, respectively, by BacL1, although degradation rates were slightly attenuated compared to those of the parent strain and the complemented strain. In addition, the cell walls of galUmut and galUmut/Vec also displayed reduced susceptibility to mutanolysin, which is a peptidoglycan hydrolase but has no capacity to induce definite bacteriolysis (Fig. S2) (22). These observations suggested that the cell wall of the galU mutant is still susceptible to the peptidoglycan hydrolase activity of BacL1. The binding of BacL1 via its C-terminal SH3 repeat domain, which is located in aa 329 to 380, is limited to the cell division loci of the target cell wall and is essential for the peptidase activity of BacL1 (22). To investigate whether the binding affinity of BacL1 for the galUmut cell wall was involved in attenuated susceptibility to degradation by BacL1, fluorescence-labeled recombinant BacL1 was incubated with E. faecalis cells and its localization analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. In the parent strain and the complemented strain, BacL1 binding was limited to division loci, as reported previously (Fig. 4B, Fig. S3A) (20). In the galUmut mutant, BacL1 strongly bound to the cell surface even more diffusely and was less limited to specific target loci, showing that the affinity of BacL1 for the cell wall of the galUmut strain appeared to be even more increased than that of the wild type. These observations suggested that attenuated susceptibility to BacL1 degradation likely is not the cause of the development of Bac41 resistance in the galU mutant, even though the overall cell surface affinity for BacL1 was altered in the galUmut mutant.

FIG 4.

galU inactivation alters the interaction of BacL1 with the cell wall of E. faecalis. (A) Cell wall fractions prepared from E. faecalis wild-type (black), galUmut (red), galUmut/Vec (blue), and galUmut/pgalU (green) strains in exponential phase were diluted with PBS. Recombinant BacL1 (rBacL1; 5 μg/ml, dotted lines) was added to the cell wall suspension, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C. The turbidity at 600 nm was quantified at the indicated times during incubation. The presented values are the percentages of the initial turbidity for the respective samples. The PBS-treated sample (mock) is presented as a negative control (straight lines). The data are presented as the means ± SD (error bars) from four independent experiments. (B) Overnight cultures of the E. faecalis wild-type, galUmut, galUmut/Vec, and galUmut/pgalU strains were diluted 5-fold with fresh THB broth and incubated with HiLyte Fluor 555 fluorescent dye-labeled (red) BacL1 (5 μg/ml), followed by analysis via fluorescence microscopy. Phase contrast (Ph) is pseudocolored (green) in the merged images. Scale bar, 4 μm.

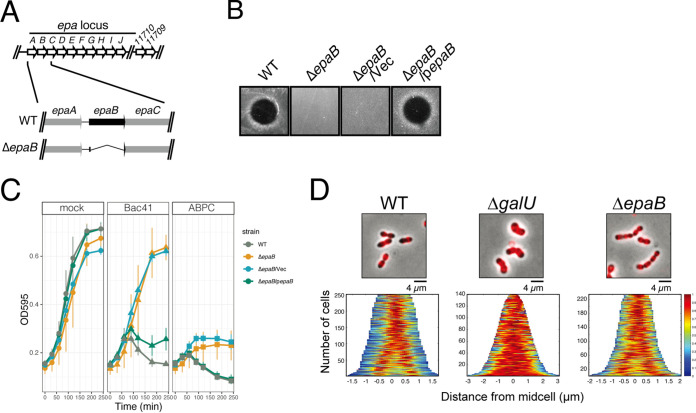

To investigate whether the phenotypes of the galUmut mutant resulted specifically from the loss of cell wall-associated polysaccharides, we constructed a deletion mutant of epaB, which is involved in the major EPA biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 5A) (32). The inactivation of epaB is suggested to result in an altered EPA structure and composition and reduced cell envelope integrity. The epaB mutant (ΔepaB) no longer produces EPA (31, 34), meanwhile it displayed normal galactose fermentation, like the wild type (Fig. S4). Notably, the ΔepaB mutant clearly represented resistance to Bac41, like the galUmut mutant (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting that Bac41 resistance in the galUmut mutant is mostly due to the inability to produce EPA.

FIG 5.

Effect of epaB deletion on the binding affinity of BacL1 and susceptibility to Bac41 activity. (A) Genomic organization of the epa locus in E. faecalis OG1RF and construction of an epaB deletion mutant. (B) A mixture of the recombinant BacL1-His and BacA-His proteins (25 ng each) was spotted onto THB soft agar (0.75%) containing the E. faecalis wild-type indicator strain and ΔepaB, ΔepaB/Vec, and ΔepaB/pepaB strains. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the formation of halos was evaluated. (C) The overnight cultures of the E. faecalis OG1RF (WT), ΔepaB, ΔepaB/Vec, and ΔepaB/pepaB strains were inoculated into fresh THB broth at a 10-fold dilution in the presence or absence of ABPC (4 mg/liter) or Bac41 (BacL1 and BacA, 2.5 μg/ml each), followed by incubation at 37°C. The turbidity (OD595) was monitored during the incubation period. The data for each case are presented as the percentage of the initial turbidity. The data are presented as the means ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments. (D) Overnight cultures of the E. faecalis wild-type, ΔgalU, and ΔepaB strains were diluted 5-fold with fresh THB broth and incubated with HiLyte Fluor 555 fluorescent dye-labeled (red) BacL1_SH3-His (5 μg/ml), followed by analysis via fluorescence microscopy.

To test the BacL1 degradation susceptibility of cell wall lacking EPA, cell wall purified from the ΔepaB mutant was subjected to cell wall degradation assay (Fig. S5). BacL1 was able to degrade the cell wall of all tested strains, including the ΔepaB and ΔgalU (galU in-frame deletion) strains and their derivatives with plasmids for complementation. In addition, BacL1 could bind to the cell surface of the ΔepaB mutant like the wild type (Fig. S3B). To characterize localization of BacL1 binding on each strain in detail, we observed relative subcellular localization of the fluorescein-labeled SH3 repeat of BacL1 (BacL1_SH3), which expresses strong and stable fluorescence signal compared to full-length BacL1 protein (20) on the wild type and the ΔgalU and ΔepaB mutants (Fig. 5D). Based on microscope images, BacL1_SH3 bound around the division site of ΔgalU and ΔepaB strains equally to the wild type, as previously reported (20). It is noted that BacL1_SH3 localization in the ΔgalU mutant was even stronger and more dispersed on the cell surface than that of the wild type. These observations are in line with our previously mentioned hypothesis that alteration of cell wall integrity does not affect BacL1 targeting for endopeptidase activity and does not underlie the resistant phenotype of these mutants against Bac41-induced cell lysis.

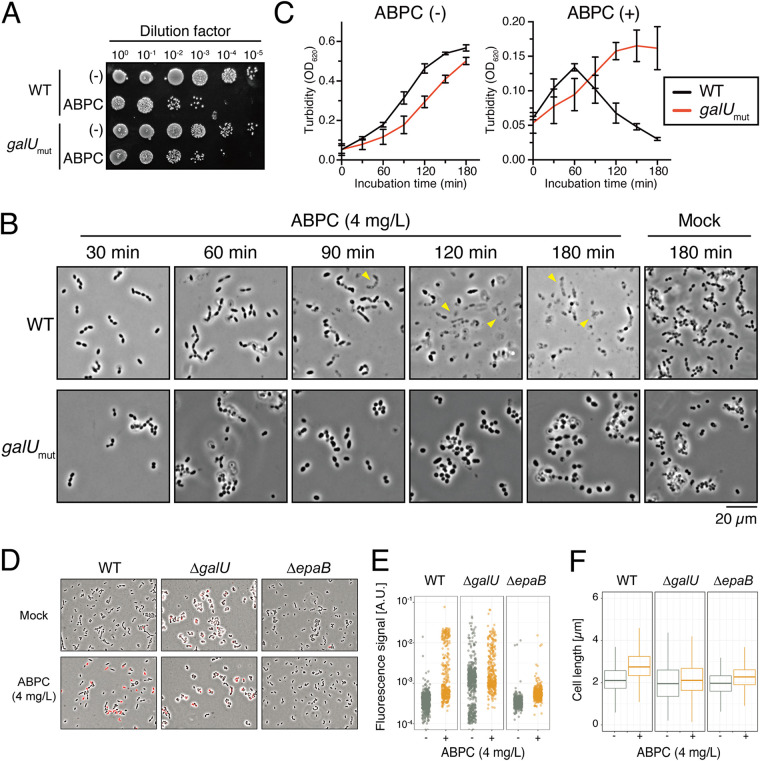

The galU inactivation and loss of EPA reduce susceptibility to beta-lactams.

It has been suggested that EPA deficiency results in reduced cell surface integrity and consequently leads to increased susceptibility to antimicrobial agents or several environmental stresses (32, 35, 36). To test this phenotype in the galUmut strain, we evaluated susceptibility to antibiotics in the OG1S derivatives (Table 1). Consistent with previous reports, bacteriostatic antibiotics (vancomycin and gentamicin) and detergent (sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) were more effective against the galUmut and galUmut/Vec strains than the wild-type and complemented strains. In contrast, the MICs of beta-lactams (ampicillin and penicillin G) for the galUmut strain were 4 mg/liter and 2 mg/liter, respectively, indicating reduced susceptibility compared to the parent strain. As already shown by Singh and Murray (37), the ΔepaB strain also displayed higher MICs and reduced susceptibility for beta-lactams than its parent (Table 1, Fig. 5C). The viability of the galUmut mutant after treatment with ampicillin (ABPC; 4 mg/liter) for 4 h was increased approximately 10-fold compared to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 6A). In microscopic experiments, the wild-type strain displayed morphological changes, with an elongated or rhomboid shape after 60 min of treatment with ABPC (4 mg/liter), and most cells exhibited drastic cell disruption between 90 and 180 min after the treatment (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, the galUmut strain displayed a milder phenotype, with a swollen shape, showing a response distinct from that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B). In addition, only a few disrupted galUmut cells were observed, even 180 min after treatment with AMP. To distinguish between a bacteriolytic effect and a growth inhibition (bacteriostatic) effect of AMP, the turbidity of bacterial broth cultures was monitored in the presence and absence of ABPC (4 mg/liter) (Fig. 6C). In the wild-type strain, the turbidity was increased after 60 min of incubation in the presence of ABPC and in the mock control. However, after 90 min, a drastic reduction of turbidity was detected, and the turbidity was eventually lower than the initial turbidity. In contrast, after exposure to AMP, the galUmut strain continued to grow constantly without reduced turbidity, although its growth rate was lower than that of the untreated culture. These results were consistent with the microscopic observations, in that the galUmut mutant could be susceptible to the bacteriostatic effect of ABPC but not to the bacteriolytic effect. Furthermore, fluorescent detection assay for cell lysis by ethidium homodimer (EthD) clearly showed that ABPC treatment increased dead cell populations in the wild type (Fig. 6D and E). On the other hand, the ΔgalU and ΔepaB mutants did not show significant increases of dead cell populations compared to the untreated control. The cell elongation effect of ABPC also is relatively lower in the ΔgalU and the ΔepaB mutants, while ABPC treatment resulted in the significant elongation of cell length in the wild type (Fig. 6F). Altogether, these data suggested that unlike other drugs and detergents, the bacteriolytic action of beta-lactams requires an intact cell surface composition constructed by the galU or epa genes.

TABLE 1.

MICs of antimicrobial drugs for E. faecalis strains

| Strain | MIC (mg/liter) ofa: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABPC | PEN | VAN | GEN | DAP | SDS | |

| OG1S WT | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 250 |

| OG1S galUmut | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | <0.125 | 125 |

| OG1S galUmut/Vec | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | <0.125 | 125 |

| OG1S galUmut/pgalU | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 250 |

| OG1RF WT | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 250 |

| OG1RF ΔgalU | 4 | 4 | 2 | 8 | <0.125 | 125 |

| OG1RF ΔepaB | 4 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 1 | 125 |

ABPC, ampicillin; PEN, penicillin; VAN, vancomycin; GEN, gentamicin; DAP, daptomycin; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate.

FIG 6.

Different bacteriolysis phenotypes induced by ampicillin treatment (ABPC) in the E. faecalis wild-type strain or the galUmut mutant. (A) The E. faecalis strains OG1S (WT) and the galUmut mutant were treated with ABPC (4 mg/liter) at 37°C for 3 h. The bacterial suspensions were serially diluted 10-fold with fresh THB and then spotted onto a THB agar plate, followed by incubation overnight. Colony formation was evaluated as a measure of bacterial viability. (B) Confluent cultures of the E. faecalis OG1S (WT) and galUmut strains were diluted 10-fold with fresh THB containing ABPC (4 mg/liter), followed by incubation at 37°C. The bacterial suspension was mounted on a slide and analyzed via microscopy (phase contrast) at the indicated time points: 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after treatment. The yellow arrowheads indicate the cell debris generated by ABPC-induced bacteriolysis. Cells incubated under identical conditions except for the absence of ABPC (Mock) are represented in the right panel as a reference. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) The overnight cultures of the E. faecalis OG1S (WT) and galUmut strains were inoculated into fresh THB broth at a 10-fold dilution in the presence or absence of ABPC (4 mg/liter), followed by incubation at 37°C. The turbidity was monitored during the incubation period. The data for each case are presented as the percentage of the initial turbidity. The data are presented as the means ± SD (error bars) from three independent experiments. (D) The overnight cultures of the E. faecalis OG1RF (WT), ΔgalU, and ΔepaB strains were inoculated into fresh THB broth at a 10-fold dilution in the presence or absence of ABPC (4 mg/liter), followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h with EthD (2 mg/liter). The bacterial suspension was mounted onto a slide and analyzed via fluorescence microscopy. Images are shown as merges of phase contrast and red fluorescence signals (EthD). (E and F) Quantification of population with red fluorescence intensity (E) and cell length (F) on each cell was generated based on data from panel D. A.U., arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

The function of the E. faecalis GalU C terminus.

Here, we demonstrated that a spontaneous Bac41-resistant isolate carried a truncation mutation in the galU gene, with the deletion of 11 C-terminal residues (Fig. 1). Like that of related species, the GalU of E. faecalis contains a conserved nucleotide transferase domain at aa 5 to 257 (see Fig. S6 and S7 in the supplemental material). However, the resistant mutant has a truncation deletion of aa 288 to 298, which does not correspond to the conserved domain. Despite this anomaly, this partial truncation leads to the inactivation of the protein’s UDP-glucose phosphorylase activity (Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). Structural studies of GalU homologues from several bacterial species revealed that their C-terminal domains entangled each other to form homodimers (38, 39). Thus, it is possible that the deletion of just 11 amino acids from the C-terminal moiety impairs this dimerization, resulting in a conformational defect that affects GalU enzymatic activity.

The role of galU in cell wall polysaccharide production in E. faecalis strains.

The gpsA-galU locus is conserved among Enterococcus and Streptococcus species, although its chromosomal location and flanking genetic context are unrelated (Fig. S7). This locus has been best studied in Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is a bacterial pathogen that causes pneumonia in humans (40). The surface capsular polysaccharide (CPS) of S. pneumoniae is a major virulence factor and the target for vaccination. More than 90 CPS types that have been defined in S. pneumoniae are synthesized from the corresponding specific cps locus, which is located between pbp2X and pbp1A (41). Although the cps genes are variable and specific for each of the 90 capsule types, gpsA-galU is highly conserved in a location that is distant from cps and is essential for the biosynthesis of every capsule type (27). Thus, gpsA-galU is suggested to play a critical role in the highly conserved universal pathway for cell surface-associated polysaccharides in various lactic acid bacterial species (42, 43). For E. faecalis, four serotypes (A, B, C, and D) have been identified (44). These serotypes are defined by variants of two cell surface components, CPS and EPA (45). The CPS is serotype-specific and is represented only in serotypes C and D but not in serotypes A and B (29). Conversely, EPA is represented in every E. faecalis strain with any serotype. OG1 strains belong to the serotype B lineage that possesses only EPA. Meanwhile, the serotype C strains, such as FA2-2 and V583, produce both EPA and CPS (44, 45). Teng et al. identified the EPA-synthesizing epa gene cluster (locus tags 11715 to 11738), which is distant from the gpsA-galU locus (locus tags 11457 and 11458), on the OG1RF chromosome (30, 32). Recent study by Guerardel et al. defined the structure of EPA, and it consists of several sugars, including glucose, galactose, rhamnose, and ribitol (28). According to previous studies of capsular polysaccharide synthesis, those sugars are utilized to construct the cell wall glycopolymer through uridyl-nucleotide intermediates, such as UDP-glucose, which is produced by GalU. The data showing that the inactivation of the galU gene caused the abolishment of EPA (Fig. 2C) demonstrated the involvement of the gpsA-galU locus in the universal biosynthetic pathway for cell surface polysaccharide species in E. faecalis, which is similar to available reports for S. pneumoniae. The deletion of galU resulted in the complete loss of cell wall-associated polysaccharides in the serotype C E. faecalis FA2-2 (Fig. S8), suggesting that GalU also plays a role in CPS production. This study describes the function of galU in the biosynthesis of cell wall-associated polysaccharides in E. faecalis.

Deduced model of galU-dependent susceptibility to lytic agents.

A previous study revealed that the inactivation of galU decreases cellular robustness against several stresses, such as antibiotics and H2O2 (46). Here, we confirmed that the galUmut strain displayed lower MICs for gentamicin, daptomycin, and SDS than the parent strain (Table 1). However, we focused on the opposite phenotype, that the inactivation of galU conferred resistance to the lytic bacteriocin Bac41 (BacL1 and BacA) and beta-lactams (Fig. 1 and 6 and Table 1). Compared with the wild-type strain, the galUmut strain produced a cell wall with slightly reduced susceptibility to BacL1 degradation (Fig. 4A). The contribution of this phenotype to resistance should be partial, and this process did not appear to be the fundamental mechanism by which the bacteriolytic activity of Bac41 is triggered by the undefined action of BacA (undetectable action in our previous experiments) following peptidoglycan degradation by BacL1 (20, 22). UDP-glucose is essential for the biosynthesis of not only cell surface polysaccharides but also other cell wall-associated components, such as teichoic acid. The ΔepaB mutant that displayed a specific EPA defect conferred Bac41 resistance, as observed for the galUmut mutant (Fig. 5C). However, we cannot conclude that EPA contributed exclusively or directly to susceptibility to Bac41, because both mutants displayed the characteristic phenotype of abnormal cell morphology (Fig. 3 and 5) (31), suggesting that this drastic phenotype is caused by the loss of envelope integrity that results from the depletion of cell wall-associated polysaccharides (32). It is worth noting that the morphological defects observed in the galU and epaB mutants were not identical, which implies that other UDP-glucose-derived components affect the phenotype of the galU mutant. In Bacillus subtilis, which is a model organism for Firmicutes, GtaB (a GalU homologue) is indispensable for cell morphology. The GtaB-deficient mutant exhibits a dislocation of FtsZ, which is a conserved protein that determines the contracting (separating) site during binary cell division, and the mutant consequently exhibits impaired cell division with an abnormal cell shape (47). As shown in Fig. 4, the galUmut mutant gave rise to a dispersed localization of BacL1, which binds specifically to the nascent cell wall and displays a limited localization at the mid-cell in the wild-type strain (20).Since the cell division machinery complex performs dual functions (synthesize and degrade peptidoglycan), the failure to properly control this machinery, especially the inhibition of penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), leads to lethal effects on bacterial cells. The potential intrinsic lethality of the cell division machinery has been suggested to underlie beta-lactam-induced bacteriolysis (48). Therefore, it is possible that the deactivated cell division machinery in the galUmut and ΔepaB mutants reduces the intrinsic lethality of the cell division machinery, resulting in resistance to Bac41 or beta-lactams. Collectively, this study provides insights into the intrinsic factors involved in the extrinsic bacteriolysis mechanism in E. faecalis, but further investigation is required to understand the precise mechanism that underlies these effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and antimicrobial agents.

The bacterial strains and the plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 2. Enterococcal strains were routinely grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) (Difco, Detroit, MI) at 37°C (49), unless stated otherwise. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (Difco) medium at 37°C. The antibiotic concentrations used to select E. coli were 100 mg/liter ampicillin (AMP), 30 mg/liter chloramphenicol, and 500 mg/liter erythromycin. The concentrations used for the routine selection of E. faecalis harboring pMGS100 or pMSP3535 derivatives were 20 mg/liter chloramphenicol or 10 mg/liter erythromycin, respectively. Nisin was added at a concentration of 25 mg/liter for the cultivation of the E. faecalis strain harboring pMSP3535. All antibiotics were obtained from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO).

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. faecalis | ||

| OG1S | strr, derivative of OG1 | 49 |

| OG1S::galUmut (sr#4) | Isogenic mutant of OG1S carrying the point mutation in galU | This study |

| CK111 | Donor for conjugation of pCJK47 derivatives | 52 |

| OG1RF | rifr, fusr, derivative of OG1 | 49 |

| OG1RFΔgalU | Isogenic mutant of OG1RF carrying the in-frame deletion of galU | This study |

| OG1RFΔepaB | Isogenic mutant of OG1RF carrying the in-frame deletion of epaB | This study |

| FA2-2 | rifr, fusr, derivative of JH2 | 49 |

| FA2-2ΔgalU | Isogenic mutant of FA2-2 carrying the in-frame deletion of galU | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host for DNA cloning | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| BL21 Rosetta | Host for protein expression | Novagen |

| EC1000 | Host for cloning of pCJK47 derivatives | 52 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMGS100 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle expression plasmid; cat | 50 |

| pgalU | pMGS100 containing galU gene | This study |

| pCF10-101 | Helper plasmid for conjugation of pCJK47 derivatives | 52 |

| pCJK47 | Suicide vector for construction of deletion mutants | 52 |

| pCJK47::ΔgalU | pCJK47 containing in-frame deletion of galU and its flanking region | This study |

| pCJK47::ΔepaB | pCJK47 containing in-frame deletion of epaB and its flanking region | This study |

| pMSP3535 | E. coli-E. faecalis shuttle nisin-inducible expression plasmid; erm | 51 |

| pepaB | pMSP3535 containing epaB gene | This study |

| pET22(+) | Expression vector of His-tagged protein in E. coli | Novagen |

| pET22::bacL1 | pET22b(+) containing bacL1 gene derived from pYI14 | 22 |

| pET22::bacA | pET22b(+) containing bacA gene derived from pYI14 | 22 |

| Oligonucleotidesa | ||

| F-galU_del_up | ccggaattcCCTGGGGGACAGCTTTAGCT | This study |

| R-galU-del_up | ctcttttttcgcTGCTGGAATAACTGCCTTTT | This study |

| F-galU_del_dwn | gttattccagcaGCGAAAAAAGAGCAACCAAA | This study |

| R-galU-del_dwn | ccggaattcCTTGAGCATCGTCAGCTGCT | This study |

| F-galU-pMGS | ttttgaggaggcggcATGAAAGTTAAAAAGGCAGT | This study |

| R-galU-pMGS | gcgtcgatcttatcgTTATTTTTCTTTTGGTTGCT | This study |

| F-epaB_del_up | ccatacggaattcGGATAGATTTTGTG | This study |

| R-epaB-del_up | atttgttaaaCGAGATTGTTACCATTTCTT | This study |

| F-epaB_del_dwn | aacaatctcgTTTAACAAATGGGGCTGGAG | This study |

| R-epaB-del_dwn | ccatacggaattcGAATACTATCTAATTGTTCC | This study |

| F-epaB-pMSP3535 | gactctgcatggatcATGAGCATGCAAGAAATGGT | This study |

| R-epaB-pMSP3535 | tagtggtaccggatcTTAAAAGAACCTCCAGCCCC | This study |

Lowercase letters indicate additional nucleotides for enzyme digestion, overlap PCR, or seamless cloning.

Soft-agar bacteriocin experiment.

The soft-agar assay for bacteriocin activity was performed as described previously (7). Briefly, 1 μl of recombinant protein solution (25 ng/μl) was inoculated into THB soft agar (0.75%) containing the indicator strain and was then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The formation of an inhibitory zone was evaluated as a sign of bacteriocinogenic activity of the test strain. The histidine-tagged recombinant proteins of BacL1 and BacA were prepared by the Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as previously described (22).

Next-generation sequencing and variant analysis.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from E. faecalis OG1S and its isogenic spontaneous mutant using an Isoplant DNA isolation kit (Nippon gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was submitted to Otogenetics Corporation (Norcross, GA USA) for exome capture and sequencing. Briefly, gDNA was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and optical density (OD) ratio tests to confirm the purity and concentration of the DNA prior to Bioruptor (Diagenode, Inc., Denville, NJ) fragmentation. Fragmented gDNAs were tested for size distribution and concentration using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 or Tapestation 2200 and NanoDrop. Illumina libraries were made from qualified fragmented gDNA using the SPRIworks HT reagent kit (catalog no. B06938; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) or NEBNext reagents (catalog no. E6040; New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), and the resulting libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000/2500, which generated paired-end reads of 100 nucleotides (nt). Data were analyzed for data quality using FASTQC (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK).

Construction of expression plasmids.

To complement the galU defect in the galUmut strain, a galU expression plasmid designated pgalU was constructed as described below. A 927-bp fragment containing the full-length galU gene (897 bp) and an additional sequence at both ends (15 bp each) was amplified by PCR with the primers F-galU-pMGS and R-galU-pMGS, using E. faecalis OG1S genomic DNA as the template. Using In-fusion HD cloning (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), the resulting fragment was cloned into pMGS100 (50), which was linearized by digestion with NdeI and XhoI. The resulting plasmid was designated pgalU. To complement the epaB defect, an epaB expression plasmid designated pepaB was constructed as described below. An 819-bp fragment containing the full-length epaB gene (OG1RF_11737, 789 bp) and an additional sequence at both ends (15 bp each) was amplified by PCR with the primers F-epaB-pMSP3535 and R-epaB-pMSP3535, using E. faecalis OG1RF genomic DNA as the template. Using In-fusion HD cloning (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), the resulting fragment was cloned into pMSP3535 (51), which was linearized by digestion with BamHI. The resulting plasmid was designated pepaB.

Site-directed in-frame deletion of galU.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out as described previously by Kristich et al. (52). The 1-kbp flanking DNA fragments of the upstream or downstream regions of galU (OG1RF; previously annotated cap4C) were amplified by PCR with the primers F-galU-del-up and R-galU-del-up or F-galU-del-dwn and R-galU-del-dwn, respectively, using Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF genomic DNA as the template. The resulting fragments were fused via overlapping PCR with the primers F-galU-del-up and R-galU-del-dwn, and the resulting 2-kb fragment was digested with EcoRI and cloned into pCJK47 at its EcoRI site to obtain pCJK47::ΔgalU. The pCJK47::ΔgalU plasmid was introduced into E. faecalis CK111 and then was transferred into E. faecalis OG1RF and FA2-2. The integrants of OG1RF and FA2-2 in which pCJK47::ΔgalU was integrated into the chromosome via primary crossing over were isolated through erythromycin selection. Cultivation without the drug allowed crossing over to facilitate the dropout of pCJK47 derivatives. The isolated candidates were screened by PCR with primers that were set outside the region used for cloning into pCJK47. The site-directed deletion of the epaB gene was also carried out as described above, except pCJK47::ΔepaB was constructed using specific primer pairs (F-epaB-del-up and R-epaB-del-up or F-epaB-del-dwn and R-epaB-del-dwn) for the upstream region or downstream region, respectively. Both the ΔgalU and ΔepaB mutants carry the initial 30 nt from the start codon and the terminal 30 nt, including the stop codon, without a frameshift (N-terminal 10 aa and C-terminal 9 aa). The mutant genes encode the 19-aa fusion proteins with N-terminal 10-aa and C-terminal 9-aa regions.

Scanning electron microscopy.

A 200-μl overnight culture of bacteria was diluted 5-fold with 800 μl of fresh THB and transferred onto a coverslip grass (Iwanami) in a 24-well plate following incubation at 37°C for 2 h (Iwanami). The coverslip was rinsed with 1 ml of 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The bacteria on the coverslip were fixed with 1 ml of 1st fixation buffer (2% glutaraldehyde, 4% sucrose, 0.15% Alcian blue, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer [pH 7.4]) for 2 h at room temperature (RT). After primary fixation, the coverslip was washed three times with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). An additional fixation was carried out with 1 ml of 2nd fixation buffer (0.5% OsO4, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer [pH 7.4]) for 2 h at RT. The coverslip was washed with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The sample was dehydrated using an ascending ethanol series (50% [1 min], 70% [2 min], 80% [3 min], and 100% [5 min 2×]) and was air dried. Osmium coating was carried out at 5 to 6 mA for 20 s using an Osmium coater (Neoc-ST; Meiwafosis Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The sample was observed by the scanning electron microscopy (S-410; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Fluorescent microscopy.

The red fluorescent dye-labeled recombinant protein of BacL1 was prepared with NH2-reactive HiLyte Fluor 555 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) as previously described (20). Bacteria diluted with fresh medium were mixed with fluorescent recombinant protein and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 5,800 × g for 3 min and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 15 min. The bacteria were rinsed and resuspended with distilled water and mounted with Prolong gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen) on a glass slide. The sample was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Axiovert 200; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and images were obtained with a DP71 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For detection of dead cells, ethidium homodimer (EthD; molecular probe) was added in bacterial culture at a final concentration of 2 μM and prepared for the microscopic analysis as described above. Raw image data were processed using FIJI (53). Cell segmentation and generation of fluorescence signal demographs were performed by Oufti (33). Statistical analysis and graphical representation on imaging data acquired by Oufti was performed by using R packages BactMAP (54) and ggplot2 (55).

Preparation and degradation analysis of the cell wall fraction.

The bacterial culture was collected by centrifugation and rinsed with 1 M NaCl. The bacterial pellet was suspended in 4% SDS and heated at 95°C for 30 min. After rinsing with distilled water (DW) four times, unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 1 min, and the cell wall fraction in the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min and then treated with 0.5 mg/ml trypsin (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 20 mM CaCl2) at 37°C for 16 h. The sample was further washed with DW four times and was resuspended in 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), followed by incubation at 4°C for 5 h, and then given four additional washes with DW. Finally, the cell wall fraction was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell wall degradation rate was quantified by measuring the optical density at 620 nm (OD620) using a microplate reader (Thermo).

Preparation of cell surface polysaccharides.

Cell surface polysaccharides were prepared as described by Hancock and Gilmore (45). An overnight bacterial culture was inoculated with a 1:100 dilution in 25 ml of THB containing 1% glucose, grown at 37°C for 5 h, and then centrifuged to collect the cells (3,000 rpm, 10 min). The cells were washed with 2 ml of Tris-sucrose solution (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 25% sucrose). The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in the Tris-sucrose solution containing lysozyme (1 mg/ml) and mutanolysin (10 U/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. The suspension was then centrifuged (8,000 rpm, 3 min). The supernatant was collected into a new tube and was treated with RNase I (100 μg/ml) and DNase I (10 U/ml) at 37°C for 4 h. Pronase E was added (20 μg/ml) and the sample further incubated at 37°C for 16 h, and then 500 μl of chloroform was added to the sample, which was centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 10 min). The aqueous phase (∼300 μl) was transferred into a new tube and 920 μl of ethanol added (final concentration, 75%) to precipitate the contents at −80°C for 30 min. The precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation (15,000 rpm, 10 min), air dried, and resuspended with 100 μl of DW into one tube. Approximately 2.5 μl of the resulting sample was subjected to 10% acrylamide gel electrophoresis buffered by TBE (10 mM Tris, 10 mM borate, 2 mM EDTA). The separated carbohydrates were visualized with Stains-All (Sigma).

Fermentation test.

Fermentation of the respective sugar was examined as described before (27). Briefly, the E. faecalis strains were streaked on heart infusion (HI; Difco) agar supplemented with 1% glucose or 1% galactose. Phenol red was added as a pH indicator at a final concentration of 25 ppm. After incubation overnight at 37°C, fermentation was evaluated by the appearance of bacterial colonies and acidification of the agar medium.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs of the antibiotics were determined by the agar dilution method according to CLSI recommendations (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [http://clsi.org/]). An overnight culture of each strain grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) was diluted 100-fold with fresh broth. An inoculum of approximately 5 × 105 cells was spotted onto a series of Mueller-Hinton agar (Eiken, Tokyo, Japan) plates containing a range of concentrations of the test drug. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the number of colonies that had grown on the plates was determined.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gary Dunny for providing the bacterial strains and the plasmids used to construct the mutants, Mari Arai and Satomi Tsuchihashi for providing technical assistance in this study, and Elizabeth Kamei for providing English proofreading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology (Kiban [C] 18K07101, Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists [B] 25870116, Gunma University Operation Grants) and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (H27-Shokuhin-Ippan-008), as well as the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (Research Program on Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases; 20fk0108061h0503 and 20wm0225008h0201).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2012. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nes IF, Diep DB, Holo H. 2007. Bacteriocin diversity in Streptococcus and Enterococcus. J Bacteriol 189:1189–1198. doi: 10.1128/JB.01254-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nes IF, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N, Diep DB. 2014. Enterococcal bacteriocins and antimicrobial proteins that contribute to niche control. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, et al. (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack RW, Tagg JR, Ray B. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev 59:171–200. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field D, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross RP. 2010. The dawning of a “golden era” in lantibiotic bioengineering. Mol Microbiol 78:1077–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aymerich T, Holo H, Håvarstein LS, Hugas M, Garriga M, Nes IF. 1996. Biochemical and genetic characterization of enterocin A from Enterococcus faecium, a new antilisterial bacteriocin in the pediocin family of bacteriocins. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1676–1682. doi: 10.1128/AEM.62.5.1676-1682.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ike Y, Clewell DB, Segarra RA, Gilmore MS. 1990. Genetic analysis of the pAD1 hemolysin/bacteriocin determinant in Enterococcus faecalis: tn917 insertional mutagenesis and cloning. J Bacteriol 172:155–163. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.155-163.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawa N, Wilaipun P, Kinoshita S, Zendo T, Leelawatcharamas V, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2012. Isolation and characterization of enterocin W, a novel two-peptide lantibiotic produced by Enterococcus faecalis NKR-4–1. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:900–903. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06497-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas W, Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. 2002. Two-component regulator of Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin responds to quorum-sensing autoinduction. Nature 415:84–87. doi: 10.1038/415084a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue T, Tomita H, Ike Y. 2006. Bac 32, a novel bacteriocin widely disseminated among clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1202–1212. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1202-1212.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M, Galvez A, Samyn B, Beeumen JV, Coyette J, Valdivia E. 1994. Determination of the gene sequence and the molecular structure of the enterococcal peptide antibiotic AS-48. J Bacteriol 176:6334–6339. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6334-6339.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todokoro D, Tomita H, Inoue T, Ike Y. 2006. Genetic analysis of bacteriocin 43 of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:6955–6964. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00934-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomita H, Fujimoto S, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. 1997. Cloning and genetic and sequence analyses of the bacteriocin 21 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pPD1. J Bacteriol 179:7843–7855. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7843-7855.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomita H, Fujimoto S, Tanimoto K, Ike Y. 1996. Cloning and genetic organization of the bacteriocin 31 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pYI17. J Bacteriol 178:3585–3593. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3585-3593.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita H, Tomita H, Inoue T, Ike Y. 2011. Genetic organization and mode of action of a novel bacteriocin, bacteriocin 51: determinant of VanA-type vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4352–4360. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01274-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsen T, Nes IF, Holo H. 2003. Enterolysin A, a cell wall-degrading bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecalis LMG 2333. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:2975–2984. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.5.2975-2984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomita H, Kamei E, Ike Y. 2008. Cloning and genetic analyses of the bacteriocin 41 determinant encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pYI14: a novel bacteriocin complemented by two extracellular components (lysin and activator). J Bacteriol 190:2075–2085. doi: 10.1128/JB.01056-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurushima J, Ike Y, Tomita H. 2016. Partial diversity generates effector-immunity specificity of the Bac41-like bacteriocins of Enterococcus faecalis clinical strains. J Bacteriol 198:2379–2390. doi: 10.1128/JB.00348-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng B, Tomita H, Inoue T, Ike Y. 2009. Isolation of VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis strains from nosocomial infections: first report of the isolation and identification of the pheromone-responsive plasmids pMG2200, encoding VanB-type vancomycin resistance and a Bac41-type bacteriocin, and pMG2201, encoding erythromycin resistance and cytolysin (Hly/Bac). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:735–747. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00754-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurushima J, Nakane D, Nishizaka T, Tomita H. 2015. Bacteriocin protein BacL1 of Enterococcus faecalis targets cell division loci and specifically recognizes l-Ala2-cross-bridged peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol 197:286–295. doi: 10.1128/JB.02203-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomita H, Todokoro D, Ike Y. 2010. Genetic analysis of the bacteriocin 41 encoded on the Enterococcus faecalis pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmid pYI14. Abstr 3rd Int ASM Conf Enterococci, abstr 30B. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurushima J, Hayashi I, Sugai M, Tomita H. 2013. Bacteriocin protein BacL1 of Enterococcus faecalis is a peptidoglycan D-isoglutamyl-L-lysine endopeptidase. J Biol Chem 288:36915–36925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.506618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonofiglio L, García E, Mollerach M. 2005. Biochemical characterization of the pneumococcal glucose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalU) essential for capsule biosynthesis. Curr Microbiol 51:217–221. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-4466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendicino J. 1960. Sucrose phosphate synthesis in wheat germ and green leaves. J Biol Chem 235:3347–3352. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neves AR, Pool WA, Solopova A, Kok J, Santos H, Kuipers OP. 2010. Towards enhanced galactose utilization by Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7048–7060. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01195-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berbis M, Sanchez-Puelles J, Canada F, Jimenez-Barbero J. 2015. Structure and function of prokaryotic UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, a drug target candidate. Curr Med Chem 22:1687–1697. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150114151248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mollerach M, López R, García E. 1998. Characterization of the galU gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding a uridine diphosphoglucose pyrophosphorylase: a gene essential for capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis. J Exp Med 188:2047–2056. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerardel Y, Sadovskaya I, Maes E, Furlan S, Chapot-Chartier M-P, Mesnage S, Rigottier-Gois L, Serror P. 2020. Complete structure of the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen (EPA) of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis V583 reveals that EPA decorations are teichoic acids covalently linked to a rhamnopolysaccharide backbone. mBio 11:e00277-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00277-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thurlow LR, Thomas VC, Hancock LE. 2009. Capsular polysaccharide production in Enterococcus faecalis and contribution of CpsF to capsule serospecificity. J Bacteriol 191:6203–6210. doi: 10.1128/JB.00592-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teng F, Jacques-Palaz KD, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2002. Evidence that the enterococcal polysaccharide antigen gene (epa) cluster is widespread in Enterococcus faecalis and influences resistance to phagocytic killing of E. faecalis. Infect Immun 70:2010–2015. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2010-2015.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng F, Singh KV, Bourgogne A, Zeng J, Murray BE. 2009. Further characterization of the epa gene cluster and Epa polysaccharides of Enterococcus faecalis. Infect Immun 77:3759–3767. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00149-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dale JL, Cagnazzo J, Phan CQ, Barnes AMT, Dunny GM. 2015. Multiple roles for Enterococcus faecalis glycosyltransferases in biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance, cell envelope integrity, and conjugative transfer. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4094–4105. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00344-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paintdakhi A, Parry B, Campos M, Irnov I, Elf J, Surovtsev I, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2016. Oufti: an integrated software package for high-accuracy, high-throughput quantitative microscopy analysis. Mol Microbiol 99:767–777. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Y, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. 1998. A cluster of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis from Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Infect Immun 66:4313–4323. doi: 10.1128/IAI.66.9.4313-4323.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korir ML, Dale JL, Dunny GM. 2019. Role of epaQ, a previously uncharacterized enterococcus faecalis gene, in biofilm development and antimicrobial resistance. J Bacteriol 201:e00078-19. doi: 10.1128/JB.00078-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatterjee A, Johnson CN, Luong P, Hullahalli K, McBride SW, Schubert AM, Palmer KL, Carlson PE, Duerkop BA. 2019. Bacteriophage resistance alters antibiotic-mediated intestinal expansion of enterococci. Infect Immun 87:e00085-19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00085-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh KV, Murray BE. 2019. Loss of a major enterococcal polysaccharide antigen (Epa) by Enterococcus faecalis is associated with increased resistance to ceftriaxone and carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00481-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00481-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoden JB, Holden HM. 2007. The molecular architecture of glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase. Protein Sci 16:432–440. doi: 10.1110/ps.062626007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aragão D, Fialho AM, Marques AR, Mitchell EP, Sá-Correia I, Frazão C. 2007. The complex of Sphingomonas elodea ATCC 31461 glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase with glucose-1-phosphate reveals a novel quaternary structure, unique among nucleoside diphosphate-sugar pyrophosphorylase members. J Bacteriol 189:4520–4528. doi: 10.1128/JB.00277-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentley SD, Aanensen DM, Mavroidi A, Saunders D, Rabbinowitsch E, Collins M, Donohoe K, Harris D, Murphy L, Quail MA, Samuel G, Skovsted IC, Kaltoft MS, Barrell B, Reeves PR, Parkhill J, Spratt BG. 2006. Genetic analysis of the capsular biosynthetic locus from all 90 pneumococcal serotypes. PLoS Genet 2:e31–e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad SB, Jayaraman G, Ramachandran KB. 2010. Hyaluronic acid production is enhanced by the additional co-expression of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardy GG, Caimano MJ, Yother J. 2000. Capsule biosynthesis and basic metabolism in Streptococcus pneumoniae are linked through the cellular phosphoglucomutase. J Bacteriol 182:1854–1863. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1854-1863.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maekawa S, Yoshioka M, Kumamoto Y. 1992. Proposal of a new scheme for the serological typing of Enterococcus faecalis strains. Microbiol Immunol 36:671–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hufnagel M, Hancock LE, Koch S, Theilacker C, Gilmore MS, Huebner J. 2004. Serological and genetic diversity of capsular polysaccharides in Enterococcus faecalis. J Clin Microbiol 42:2548–2557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2548-2557.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hancock LE, Gilmore MS. 2002. The capsular polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis and its relationship to other polysaccharides in the cell wall. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:1574–1579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032448299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rigottier-Gois L, Alberti A, Houel A, Taly J-F, Palcy P, Manson J, Pinto D, Matos RC, Carrilero L, Montero N, Tariq M, Karsens H, Repp C, Kropec A, Budin-Verneuil A, Benachour A, Sauvageot N, Bizzini A, Gilmore MS, Bessières P, Kok J, Huebner J, Lopes F, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Hartke A, Serror P. 2011. Large-scale screening of a targeted Enterococcus faecalis mutant library identifies envelope fitness factors. PLoS One 6:e29023-10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weart RB, Lee AH, Chien A-C, Haeusser DP, Hill NS, Levin PA. 2007. A metabolic sensor governing cell size in bacteria. Cell 130:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho H, Uehara T, Bernhardt TG. 2014. Beta-lactam antibiotics induce a lethal malfunctioning of the bacterial cell wall synthesis machinery. Cell 159:1300–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunny GM, Craig RAR, Carron RLR, Clewell DB. 1979. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid 2:454–465. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(79)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujimoto S, Ike Y. 2001. pAM401-based shuttle vectors that enable overexpression of promoterless genes and one-step purification of tag fusion proteins directly from Enterococcus faecalis. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1262–1267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1262-1267.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in Gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190. doi: 10.1006/plas.2000.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2007. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 57:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez J-Y, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raaphorst R van, Kjos M, Veening J-W. 2020. BactMAP: an R package for integrating, analyzing and visualizing bacterial microscopy data. Mol Microbiol 11:2699. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villanueva RAM, Chen ZJ. 2019. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (2nd ed). Meas Interdiscip Res Perspectives 17:160–167. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2019.1565254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.