Highlights

-

•

Lipomas often require delicate surgical intervention due to their potential risk of malignant transformation.

-

•

Suspicious features such as large size, heterogeneity, irregular septa, high degree of vascularity, warrant initial biopsy.

-

•

Radiological guidance should provide enough evidence for a biopsy, hence saving the patient an extra invasive procedure.

-

•

We recommend taking at least 1 cm of border margin while removing these tumors to avoid local recurrence.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Keywords: Lipoma, Lipocytes, Lipoblasts, Tumors

Abstract

Introduction

Lipomas are the most common soft tissue tumor. Giant lipomas are defined by measuring at least 10 cm in diameter in one dimension or by a minimum of 1000 g. They often are asymptomatic; however, they can cause compression syndromes due to nerve damage and difficulties in walking.

Presentation of case

We described the case of a 25-year-old female with no significant medical history who began her condition two years before her consultation. The patient referred to the appearance of a non-painful mass on her right thigh with progressive growth that hinders daily activities. A simple CT scan reported a 10.3 × 8.1 × 19.6 cm adipose mass with infiltration towards the semitendinosus muscle and the biceps femoris muscle. A free margin resection of the tumor was performed, and the involved muscles were preserved. The patient had a satisfactory postoperative outcome.

Discussion

Lipomas are common benign soft tissue tumors that arise from fatty tissue and may challenge surgical management due to their extension and dimensions; they often require delicate surgical intervention due to their potential risk of malignant transformation. We believe surgical pathologists and radiologists must draw attention to muscle involvement and the infiltrative pattern.

Conclusion

Giant lipomas should always raise awareness of malignant transformation. Radiological guidance should provide enough evidence to decide whether to do a biopsy or not; hence, saving the patient an extra invasive procedure. We recommend taking at least 1 cm of border margin while removing these tumors to avoid local recurrence.

1. Introduction

Lipomas are the most common soft tissue tumor and constitute 16 % of all mesenchymal neoplasms [1]. They can be classified as subcutaneous or subfascial and further subclassified according to their depth in two types: Intermuscular or intramuscular. Intermuscular lipomas grow between the large bundles and often form a large central tumor that secondarily infiltrates adjacent muscles. On the other hand, an intramuscular lipoma is considered to originate between the muscle fibers within the muscle bundles themselves and penetrates adjacent muscle passing through the intermuscular septa [2,3]. Lipomas can grow on any part of the body but frequently appear in the trunk and upper extremities. They are usually small in size with a soft consistency, but in some cases, they can be relatively firm and impressive in size [4]. Adipose tissue accumulation is higher in females than in males; therefore, lipomas are more frequently encountered in women and more common in the 40–60 years age group [5,6].

Giant lipomas are defined by measuring at least 10 cm in diameter in one dimension or by a minimum weight of 1000 g [7]. They often are asymptomatic; however, in rare cases, they can cause compression syndromes due to nerve damage and difficulties in walking [8,9]. Few cases of giant lipomas have been reported (Table 1). The work has been reported in line with the SCARE guidelines [10].

Table 1.

Large giant lipomas in French/English-language literature (>10 cm and >1000 g).

| Reference | Year | Localization | Pathology | Size (cm)/weight (kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Current case | 2020 | Lower limb | Lipoma | 10.8 × 9.1 × 4.4/1.392 |

| 2 | Litchinko et al [15] | 2017 | Gluteal | Unknown | 30 × 60/20 |

| 3 | Emegoakor et al [16] | 2017 | Lower limb | Unknown | 22 × 17/?? |

| 4 | Mascarenhas et al [17] | 2017 | Gluteal | Liposarcoma | 17/?? |

| 5 | Guler et al [18] | 2016 | Back | Unknown | 38 × 22 × 21/3.575 |

| 6 | Grimaldi et al [19] | 2015 | Back | Unknown | 36 × 40 × 24/5.75 |

| 7 | Dabloun et al [20] | 2015 | Back | Unknown | 25 × 25 × 18/?? |

| 8 | Silistreli et al [21] | 2004 | Back | Unknown | ??/12.350 |

| 9 | Brandler et al [22] | 1994 | Back | Unknown | ??/22.7 |

| 10 | Martin et al [23] | 1928 | Neck | Unknown | ??/12.5 |

2. Presentation of case

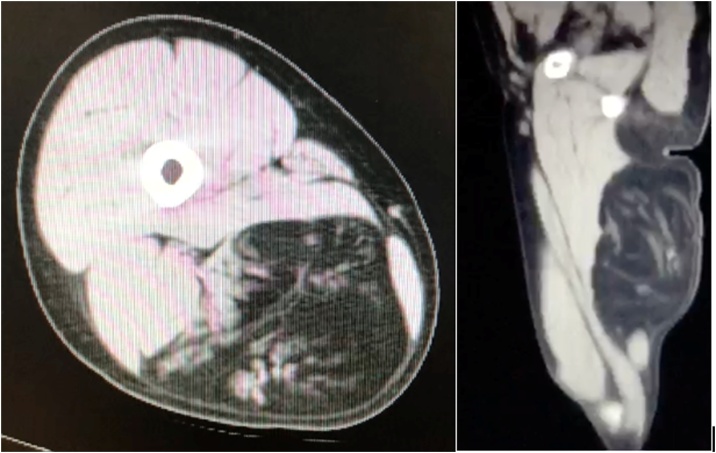

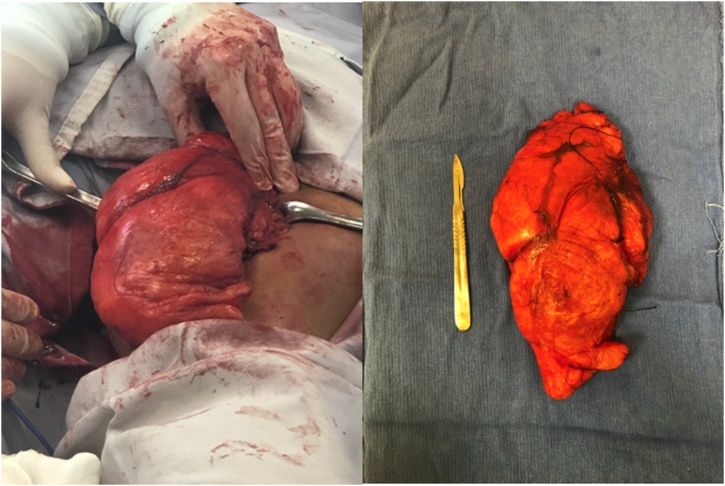

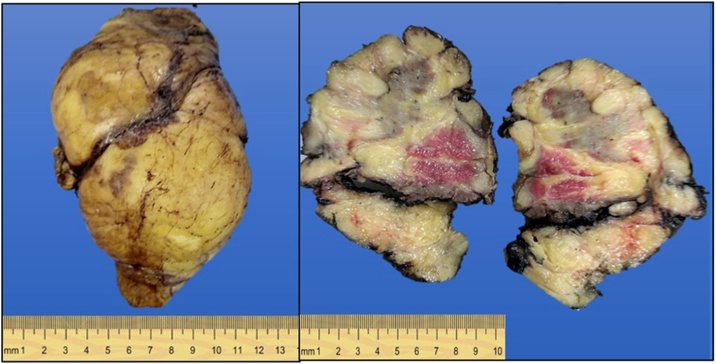

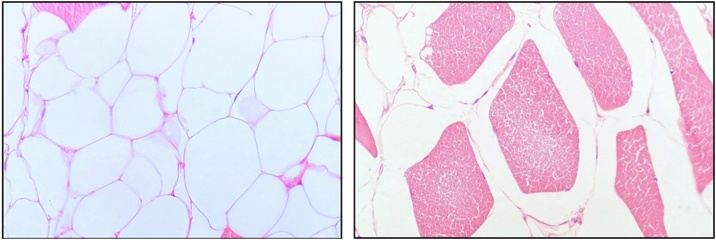

We present the case of a 25-year-old female with no significant medical history who began her condition two years before her consultation. The patient referred to a non-painful mass on her right thigh with progressive growth that hinders daily activities. The patient attends for aesthetic and functional evaluation of the tumor. On physical examination, a mass was observed along the entire length of the posterior aspect of the right thigh. On palpation, we found a well-defined, solid, mobile, and non-tender mass. An ultrasound was performed, and a well-circumscribed ovoid mass measuring 10.8 × 9.1 × 4.4 cm with heterogeneous echogenicity suggestive of lipoma was reported. The examination was completed with a simple CT scan of the right thigh (Fig. 1), reporting an encapsulated, hypodense, and oval image (106 HU) measuring 10.3 × 8.1 × 19.6 cm the posterior compartment of the thigh, with infiltration towards the semitendinosus muscle and the biceps femoris muscle. Due to the mass's clinical and radiological aspects, the tumor was removed without performing a percutaneous biopsy. A resection of the tumor was performed with free margins while preserving the involved muscles (Fig. 2). We decided to use a longitudinal approach to enable cutaneous flap closure. Surgical loupes were used to performed a delicate and meticulous dissection to avoid neurovascular injuries. An 18 Fr Blake drain was placed. The patient had a good evolution and was discharged on the third day after surgery. The pathology report described an intramuscular lipoma (Fig. 3) composed of mature lipocytes without lipoblasts, atypical nuclear cells, nor vascular involvement, characteristic of a benign lipoma (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

CT scan showing intramuscular lipoma.

Fig. 2.

Gross appearance of giant lipoma during surgery and mass excised with 1 cm margin.

Fig. 3.

Giant lipoma divided in half by pathology department.

Fig. 4.

Histological fine cuts showing adipose cells.

3. Discussion

Lipomas are common benign soft tissue tumors that arise from fatty tissue, which may challenge surgical management due to their extension and dimensions. Lipomas often require delicate surgical intervention due to their potential risk of malignant transformation.

Lipomas can be managed conservatively or excised. Lipomas are removed for the following reasons; cosmetic motives, evaluation of histology, mainly when liposarcomas must be ruled out, when they cause symptoms or when they grow and become larger than 5 cm. Indications for biopsy include a firm, rapidly enlarging mass [6]. Other treatments include liposuction in non-giant lipomas [11]. In this case, we decided to excise the tumor with wide margins since benignity cannot be assured, due to the large size of the mass, despite benign findings in the CT scan. We concluded that primary excision in giant lipomas with benign ultrasound and CT scan findings such as thin septa, homogenous echogenicity, and well-defined capsule limits are sufficient to plan a resection without prior core biopsy. This is also stated by Kransdorf et al. [12], who remarks that although there are CT or MRI features that distinguish between lipomas and liposarcomas, suspicious characteristics such as large size, heterogeneity, irregularly thickened septa, high degree of vascularity, and low-fat content all warrant an initial biopsy. However, if local recurrence, positive margins, or final pathology reports malignancy, immediate referral to oncology should be made to start radiotherapy as soon as possible.

Liposarcomas are reported to comprise 7 %–27 % of soft tissue sarcomas, and they may occur wherever fat is present; however, it now seems that their true incidence is much lower, mainly because of the recognition of the myxoid variant of malignant fibrous histiocytoma as a separate entity [13,14].

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, soft tissue tumors larger than 10 cm or heavier than 1000 g should always raise awareness of malignant transformation. Radiological guidance should provide enough evidence to decide whether to do a biopsy or not; hence, saving the patient an extra invasive procedure. We recommend taking at least 1 cm of border margin while removing these tumors to avoid local recurrence. Due to the extension of dissection of these giant lipomas, we also recommend always leave a drain to prevent complications such as hematoma or seroma. We also believe surgical pathologists and radiologists must draw attention to muscle involvement and infiltrative patterns.

It is important to note that not all patients with giant lipomas seek medical attention with typical symptoms and may instead attend physicians due to cosmetic reasons.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

No sources of funding were required.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval is required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this Journal on request.

Author contribution

CAMM-conception of the work, drafting of manuscript, final approval and agreement for the accountability of work.

MG-U-data interpretation, revising the manuscript, final approval and agreement for the accountability of work.

LFM-F- data interpretation, drafting of manuscript, final approval and agreement for the accountability of work.

MNSG- data interpretation, final approval and agreement for the accountability of work.

MRS- data interpretation, revising the manuscript, final approval and agreement for the accountability of work.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Carlos Antonio Morales Morales.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgment

None.

Contributor Information

Carlos Antonio Morales Morales, Email: cmorales91@gmail.com.

Mauricio González Urquijo, Email: mauriciogzzu@gmail.com.

Luis Fernando Morales Flores, Email: luisfmorales93@gmail.com.

Max Net Sánchez Gallegos, Email: netgallegos@hotmail.com.

Mario Rodarte Shade, Email: mario.rodarte@tec.mx.

References

- 1.Zografos Gc, Kouerinis I., Kalliopi P., Karmen K., Evangelos M., Androulakis G. Vol. 109. 2002. Giant lipoma of the thigh in a patient with morbid obesity; pp. 1467–1468. (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery). United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjerregaard P., Hagen K., Daugaard S., Kofoed H. Intramuscular lipoma of the lower limb. Long-term follow-up after local resection. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1989;71(November (5)):812–815. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2584252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis C., Gruhn J. Giant lipoma of the thigh. Arch Surg. 1967;95(July (case 1)):1–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330130153030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdulsalam T., Osuafor C.N., Barrett M., Daly T. A giant lipoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phalen G.S., Kendrick J.I., Rodriguez J.M. Lipomas of the upper extremity. Am. J. Surg. 1971;121(3):298–306. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(71)90208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salam G.A. Lipoma excision. Am. Fam. Phys. 2002;65(5):901–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez M.R., Golomb F.M., Moy J.A., Potozkin J.R. Giant lipoma: case report and review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993;28(2):266–268. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(08)81151-6. [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Benedetto G., Aquinati A., Astolfi M., Bertani A. Vol. 114. 2004. Giant compressing lipoma of the thigh; pp. 1983–1985. (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery). United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrissi J., Klersfeld D., Sampietro G., Valdivieso J. Vol. 94. 1994. Limitation of thigh function by a giant lipoma; pp. 410–411. (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery). United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;(84):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilhelmi B.J., Blackwell S.J., Mancoll J.S., Phillips L.G. Another indication for liposuction: small facial lipomas. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;103(June (7)):1864–1867. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kransdorf M.J., Bancroft L.W., Peterson J.J., Murphey M.D., Foster W.C., Temple H.T. Imaging of fatty tumors: distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma. Radiology. 2002;224(1):99–104. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celik C., Karakousis C.P., Moore R., Holyoke E.D. Liposarcomas: prognosis and management. J. Surg. Oncol. 1980;14(3):245–249. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930140309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orson G.G., Sim F.H., Reiman H.M., Taylor W.F. Liposarcoma of the musculoskeletal system. Cancer. 1987;60(6):1362–1370. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870915)60:6<1362::aid-cncr2820600634>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litchinko A., Cherbanyk F., Menth M., Egger B. Giant gluteal lipoma surgical management. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(8):10–12. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-229842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emegoakor C., Echezona C., Onwukamuche M., Nzeakor H. Giant lipomas. A report of two cases. Niger J. Gen. Pract. 2017;15(July (2)):46–49. https://www.njgp.org/article.asp?issn=1118-4647 [Internet]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mascarenhas M.R.M., Mutti L de A., de Paiva J.M.G., Enokihara M.M.S.e.S., Rosa I.P., Enokihara M.Y. Giant atypical lipoma. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017;92(4):546–549. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guler O., Mutlu S., Mahirogullari M. Giant lipoma of the back-affecting quality of life. Ann. Med. Surg. 2015;4(3):279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panse N., Sahasrabudhe P., Khade S. The levels of evidence of articles published by Indian authors in Indian journal of plastic surgery. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2015;48(2):218–220. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.163072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabloun S., Khechimi M., Jenzeri A., Maalla R. Lipome géant du dos: à propos d’un cas. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015;142(6–7):S353. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2015.04.133. [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silistreli ÖK., Durmuş E.Ü, Ulusal B.G., Öztan Y., Görgü M. What should be the treatment modality in giant cutaneous lipomas? Review of the literature and report of 4 cases. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005;58(3):394–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin H.S. Massive lipoma of the subcutaneous tissue of the back: report of case. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1928;90(June (25)):2013–2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.1928.02690520025008. [Internet]. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandler T.I. Large fibrolipoma. Br. Med. J. 1894;1:574. [Google Scholar]