Abstract

Background

Patient blood management (PBM) is an evidence-based care bundle with proven ability to improve patients’ outcomes by managing and preserving the patient’s own blood. Since 2010, the World Health Organisation has urged member states to implement PBM. However, there has been limited progress in developing PBM programmes in hospitals due to the implicit challenges of implementing them. To address these challenges, we developed a Maturity Assessment Model (MAPBM) to assist healthcare organisations to measure, benchmark, assess in PBM, and communicate the results of their PBM programmes. We describe the MAPBM model, its benchmarking programme, and the feasibility of implementing it nationwide in Spain.

Materials and methods

The MAPBM considers the three dimensions of a transformation effort (structure, process and outcomes) and grades these within a maturity scale matrix. Each dimension includes the various drivers of a PBM programme, and their corresponding measures and key performance indicators. The structure measures are qualitative, and obtained using a survey and structured self-assessment checklist. The key performance indicators for process and outcomes are quantitative, and based on clinical data from the hospitals’ electronic medical records. Key performance indicators for process address major clinical recommendations in each PBM pillar, and are applied to six common procedures characterised by significant blood loss.

Results

In its first 5 years, the MAPBM was deployed in 59 hospitals and used to analyse 181,826 hospital episodes, which proves the feasibility of implementing a sustainable model to measure and compare PBM clinical practice and outcomes across hospitals in Spain.

Conclusion

The MAPBM initiative aims to become a useful tool for healthcare organisations to implement PBM programmes and improve patients’ safety and outcomes.

Keywords: Patient Blood Management, patient safety, transfusion, maturity assessment, benchmarking

INTRODUCTION

Reducing inappropriate clinical interventions and incorporating high-value practices are major goals for any health organisation. These objectives can be connected via patient blood management (PBM), an evidence-based bundle of care to improve a patient’s outcomes by managing and preserving the patient’s own blood1.

Several studies have reported that blood transfusion is overused in clinical practice2–5, and is an independent, dose-dependent risk factor for longer hospital stays, and higher risks of death and infection6. Similarly, pre-operative anaemia is an important and highly prevalent independent risk factor for peri-operative mortality and morbidity, and is thought to be present in approximately one-third of individuals undergoing major surgery7–9. Pre-operative anaemia is also the main risk factor for red blood cell (RBC) transfusion7,10. Overuse of blood transfusions and performing elective surgery normally associated with substantial bleeding in patients with uncorrected anaemia are listed by several professional societies and “Right Care” associations as practices that should be avoided5,11,12.

The PBM concept is based on three pillars: (i) optimising erythropoiesis (treatment of anaemia), (ii) minimising bleeding and blood loss, and (iii) improving the patient’s condition to allow the use of a more restrictive transfusion threshold13–15 and has demonstrated its ability to address overuse and to improve patients’ safety, outcomes and quality of care across many different populations1,16–18.

Since 2010, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has officially been urging member states to implement PBM (WHA63.12)19, and the European Commission also recently published PBM implementation guidelines for health authorities and hospitals20, 21. With the current shortage of donors and impediments to blood supply due to the Covid-19 pandemic, a “call for action” to implement PBM has been released by a group of experts22.

In Spain, since 2006 we have had a comprehensive set of clinical guidelines on blood transfusion alternatives, known as the Seville Document (currently in its 3rd edition, with a more PBM-centred perspective), which is endorsed by seven important national scientific societies23.

Despite the known benefits of PBM, and the existence of clinical guidelines and institutional recommendations, it remains challenging to implement PBM effectively across healthcare organisations24,25. The main challenges are: (i) the broad scope of PBM programmes (multidisciplinary, multimodal, and applicable to many clinical procedures), requiring a transversal strategy throughout the organisation and a concerted change-management effort by clinicians, managers, and regulators20,21,26; (ii) the need to implement long-lasting attitudinal changes among healthcare professionals in dealing with blood transfusions during a hospitalisation27; and (iii) the lack of a widely accepted practical framework to implement, target, and monitor a PBM programme in a given hospital or healthcare organisation, although some general recommendations have been published28.

To address these challenges and improve patients’ safety, we developed a maturity assessment model to allow healthcare organisations to measure, benchmark, assess, and communicate the results of their PBM programmes. The model is implemented in Spain as the “Maturity Assessment Model in Patient Blood Management (MAPBM), www.mapbm.org”.

In this paper we describe the MAPBM, its benchmarking programme, and the feasibility of implementing it nationwide in 59 hospitals in Spain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MAPBM Assessment Model

In 2014, the MAPBM concept was developed by a multi-profession PBM group with experts from different fields (anaesthesiology, haematology, health economics, outcomes research, clinical management, and healthcare information systems). The concept included an assessment model and a strategy for deployment in hospitals.

The assessment model consists of a scorecard that allows a hospital to map its PBM organisation, PBM care delivery pathway, and PBM-related patient outcomes, according to a set of key performance indicators (KPI). Thus, the hospital can baseline its PBM performance, assess it over time, and benchmark itself against other hospitals.

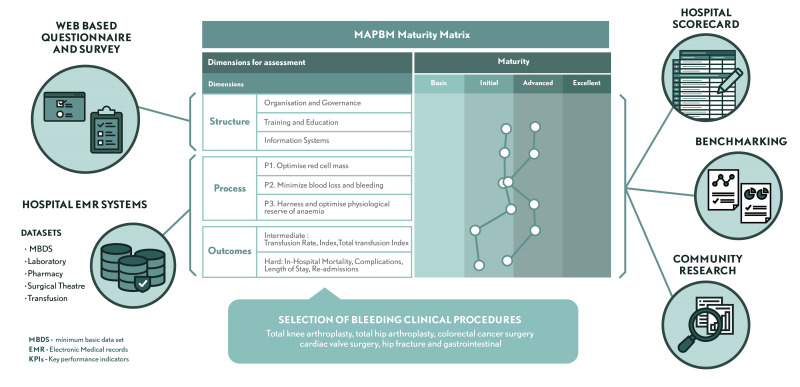

In line with the Donabedian framework, the model considers structure, process and outcomes as the three relevant dimensions of a transformation effort towards fully establishing PBM as the new standard of care20,29, and grades these within a maturity scale matrix. Each dimension consists of the various drivers of a PBM programme, and their corresponding measures and KPI (Figure 1). KPI were selected for: (i) their adequacy in measuring the structure, process or outcomes of PBM; (ii) the feasibility of having them supported/measured by information systems; and (iii) sensitivity and relevance.

Figure 1.

Maturity Assessment for Patient Blood Management programme framework and maturity matrix

The MAPBM model includes 70 measures for structure, 14 KPI for process, and 7 KPI for outcomes. Structure measures are qualitative and are obtained using a survey and a structured self-assessment checklist. The KPI for process and outcomes are quantitative and based on real-life clinical practice data gathered from the hospitals’ electronic medical records (EMR).

Structure dimension

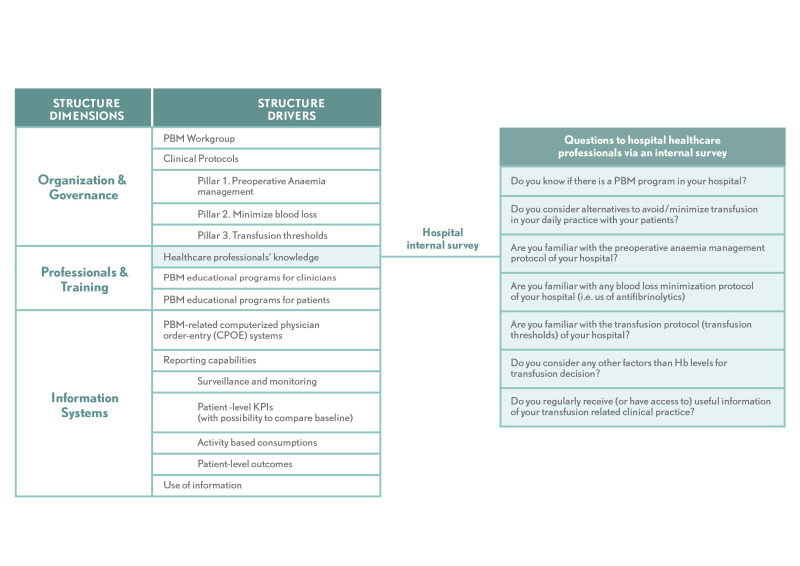

The structure dimension is rated by surveying the hospital’s clinicians and having selected members of the hospital staff assess their PBM programme’s governance and organisation, training and education, and information systems using a questionnaire. It considers eight major drivers: (i) PBM workgroup; (ii) clinical protocols; (iii) healthcare professionals’ knowledge; (iv and v) PBM educational programmes for (iv) clinicians and (v) patients; (vi) availability of PBM-related computerised physician order-entry (CPOE) systems for prescribers; (vii) hospital data-reporting capabilities; and (viii) feedback to hospital staff on their PBM practices (Figure 2). The full questionnaire is shown in Online Supplementary, Table SI.

Figure 2.

Structure dimensions and drivers

Process dimension

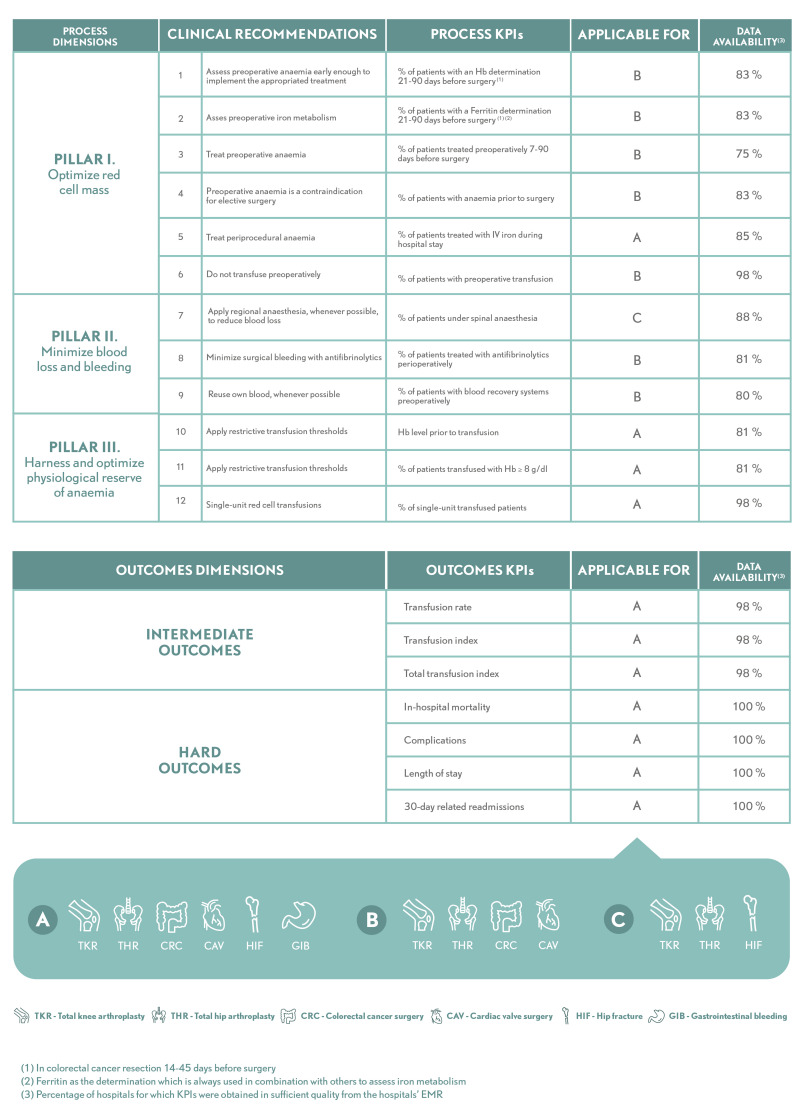

The process dimension is structured in line with standard PBM principles, known as the three pillars: (i) optimising red cell mass; (ii) minimising blood loss and bleeding; and (iii) optimising the physiological reserve of anaemia. Hence, this dimension includes KPI that measure and account for different aspects of optimisation of the patient’s condition prior to surgery, consisting mainly on the detection of pre-operative anaemia and correction of its expected progression; strategies for minimising blood loss during an intervention, such as using different types of anaesthesia or antifibrinolytic agents; and single-unit and restrictive transfusion strategies. Process KPI are listed in Figure 3 (see Online Supplementary Table SII for details).

Figure 3.

Process and Outcome dimensions, drivers and key performance indicators

Outcomes dimension

The outcomes dimension consists of: (i) intermediate outcomes, namely RBC transfusion rate, transfusion index, and total transfusion index; and (ii) hard outcomes, namely in-hospital mortality, complications, length of stay, and 30-day related readmissions (Figure 3). Outcomes are adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity. (see Online Supplementary Table SII for details).

Clinical procedures assessed by the MAPBM

The process and outcomes performance measures are applied to six common procedures in which significant blood loss is anticipated: total knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty, colorectal cancer surgery, cardiac valve surgery, hip fracture, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Within each hospital, all episodes of care with these diagnoses/procedures are captured (ICD-10 codes in Online Supplementary Table SIII).

MAPBM benchmarking programme

Along with the MAPBM Assessment Model, we established a MAPBM programme to support the enrolment of hospitals into a benchmarking and PBM improvement network, and to simultaneously and continuously improve the model.

The programme has been running annually since 2015 and uses a standard data processing and measuring approach. Hospitals voluntarily participate in the programme, which is sponsored by senior management and usually led by a hospital core team, including a PBM clinician, an information systems specialist, and a quality and safety expert.

The implementation plan for the annual hospital benchmarking programme is structured in ten steps (Table I).

Table I.

Hospital annual benchmarking programme steps

| Period (in quarters) | n. | Hospital annual benchmarking programme steps | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 1 | Enrolment of new hospitals | New hospitals joining the network are provided with information about the project, research protocol, technical data specifications and sign-off a participation agreement |

| Q2 | 2 | Start of the annual benchmarking programme | Hospital representatives gather together in an all-hands meeting to kick-off the annual edition |

| Q3 | 3 | Assessment of the hospital PBM structure | Hospital runs the internal survey to HCP and hospital project team members complete the self-assessment questionnaire about the structural elements of their PBM program |

| Q3 | 4 | MBDS data extracts for selected procedures in-scope | Selection of all in-patient episodes for the given year |

| Q3 | 5 | PBM clinical data extracts | Cross-extracts of laboratory, transfusions, surgery theatre and pharmacy data related to in-patient episodes |

| Q4 | 6 | Benchmarking results | Hospital representatives gather together to analyse and discuss benchmarking results. Results are presented aggregated and anonymised |

| Q4 | 7 | Hospital scorecard report | Hospital receives a detailed report with their scores for all MAPBM measures, in comparison with the median of the group, and evolution vs prior year |

| Q1 year2 | 8 | Hospital internal communication and analysis of results | Hospital project team analyses and disseminates the year’s results throughout hospital departments |

| Q1 year2 | 9 | Development of PBM improvement plans | Hospital PBM teams define improvement action plans with support from hospital management |

| Feedback loop | 10 | Plan – do – check –act cycles | Deployment of PBM improvement plans and continuous re-assessment with subsequent year’s results |

(*) MBDS (minimum basic data set) contains patient-level data on patients’ diagnostics, procedures, admissions, discharge status, and basic demographics such as age and sex

To assist enrolled hospitals with data files and questionnaires, we developed an online platform with user management features, approval workflows, and data validation algorithms. All data are anonymised and centrally aggregated, and risk-adjustment techniques are applied for benchmarking.

MAPBM data processing validations and risk-adjustments

Participating hospitals are provided with a specifications guideline for preparing their datasets, describing the required variables for the different database domains covered by the MAPBM. Data are reported at the patient level and time stamped, which allows the building of a consistent care pathway across all domains. This longitudinal, episode-level pathway is the backbone of the various process and outcomes metrics.

The domains covered are: (i) patients’ diagnostics, procedures, admissions, discharge status, and basic demographics such as age and sex; (ii) laboratory tests and results related to anaemia and iron deficiency; (iii) RBC transfused (iv) surgical theatre activity, use of cell salvage, antifibrinolytics and type of anaesthesia; and (v) hospital treatments for anaemia and iron deficiency. These domains are provided for inpatient episodes classified under one of the six clinical procedures assessed by the MAPBM, except for domain (i), which is provided for every inpatient captured to allow for analysis of readmissions. All variables are sourced from each hospital’s EMR. Where a hospital’s EMR structure does not allow convenient data capture for a specific domain, the hospital may opt for manual data sampling. This is somewhat common in the domain of surgical theatre activity, in which case information is recovered manually from a random sample of surgical charts.

The MAPBM Analytical Platform has two sequential parts: the Validation and Uploading Platform (VP), and the Integrated Analytics Platform (IAP). All information processed by the MAPBM is first de-identified, and patients’ data privacy is secured by encryption within the bounds of the contributing hospital, before being uploaded to the VP. Every domain database is manually uploaded by the hospital to the VP, and undergoes a validation process that flags specific warnings to the corresponding hospital team. Once the information is accepted by the IAP, all KPI are calculated in the same way for every hospital, and feed the annual scorecard, which is then returned to the hospital.

While process KPI are calculated irrespective of the population characteristics, outcomes KPI are adjusted to account for differences in risk due to various patients’ characteristics, such as age, sex and comorbidities, which are known30 to strongly influence transfusion utilisation, mortality risk, and length of hospital stay. Thus, outcomes are reported to the hospital as the observed standardised ratio vs expected. The expected outcomes are calculated using indirect standardisation in which the main classes are procedure group, age range, sex, and comorbidity groups, based on the Elixhauser index31.

MAPBM hospital scorecard

Each participating hospital receives an annual scorecard (see Online Supplementary, Figure S1 for an example) and a reporting package with its performance for each MAPBM metric, comparison to its score against that of the previous year, and the distribution of anonymised results from all other MAPBM hospitals.

The MAPBM benchmarking programme also conducts an annual hospital ranking to recognise and publicise the results of the best performing hospitals. This ranking is based on a summary index of each hospital’s results for the most relevant MAPBM metrics.

RESULTS

MAPBM implementation. Quantitative and qualitative results

In its first 5 years, MAPBM analysed 181,826 episodes in Spanish hospitals, proving the feasibility of sustainably implementing a model to measure and compare clinical PBM practice and outcomes in a network of hospitals. This demonstrates how to (i) define meaningful quantitative process KPI to comprehensively describe PBM clinical practice according to established guidelines; (ii) measure these KPI and outcomes using available information from the hospitals’ EMR; (iii) do this in a common way that facilitates benchmarking and ranking; (iv) summarise this information in a hospital scorecard, and (v) scale this model nationwide.

Translating PBM clinical guidelines into Process KPI to measure clinical practice

To measure processes across each of the three PBM pillars, we used KPI for (i) optimisation of patients’ condition before surgery, such as the percentage of patients screened for pre-operative anaemia; (ii) strategies to minimise blood loss during interventions, such as the percentage of patients with an indication for and use of antifibrinolytics; and (iii) adequacy of transfusion approaches, such as the percentage of patients transfused with single-unit ordering (Figure 3). The definition of these process KPI has proven useful and they have shown the expected statistical correlation with the corresponding intermediate outcomes (Transfusion Index).

Populating KPI with data from the hospitals’ EMR

Most MAPBM process and outcomes KPI were obtained in sufficient quality from the hospitals’ EMR. Where the required data were not routinely available for each in-patient episode, hospitals performed manual retrospective searches of randomly selected medical records. This strategy was only necessary for two KPI, namely “Patients treated with perioperative antifibrinolytics” and “Use of blood recovery systems”.

Facilitating benchmarking results between hospitals

One critical aspect of benchmarking is to work with measures that are generated in the same way for every hospital, allowing direct comparison between hospitals. This is possible in MAPBM because all data were processed centrally, with the same KPI definitions, inclusion criteria and risk-adjustment techniques to adjust for major confounders.

Providing a scorecard of hospital PBM performance

Each hospital’s scorecard allows for monitoring of the hospital’s annual performance for outcomes, process KPI and structure drivers, and for comparing its observed results against both expected and historic results. The scorecard provides numbers and graphs to facilitate the analysis, and to identify performance gaps and potential for improvement for each clinical procedure. Moreover, the Maturity Matrix adds valuable traceability that allows the hospital to link any improvement in outcomes (e.g. transfusion rate) to specific process KPI, which then can feed into their Plan-Do-Check-Act management paradigm, which otherwise is very challenging in multidimensional environments such as healthcare.

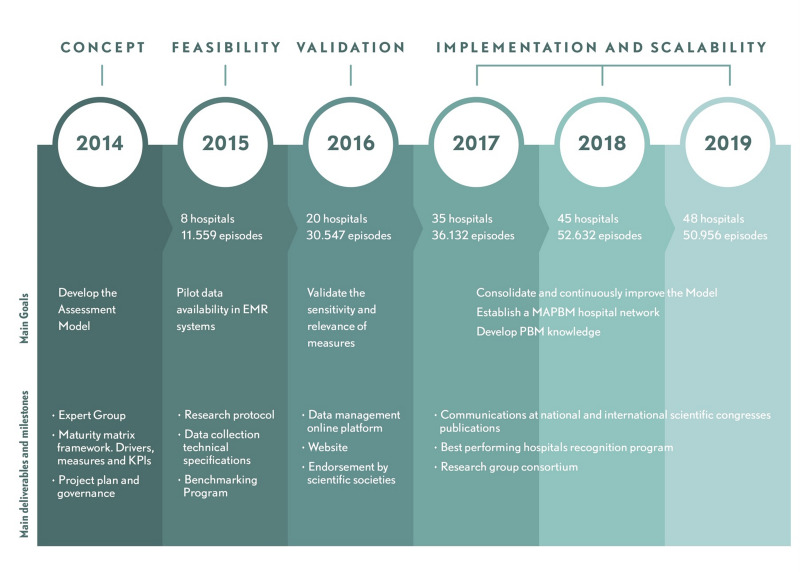

Scaling MAPBM nationwide

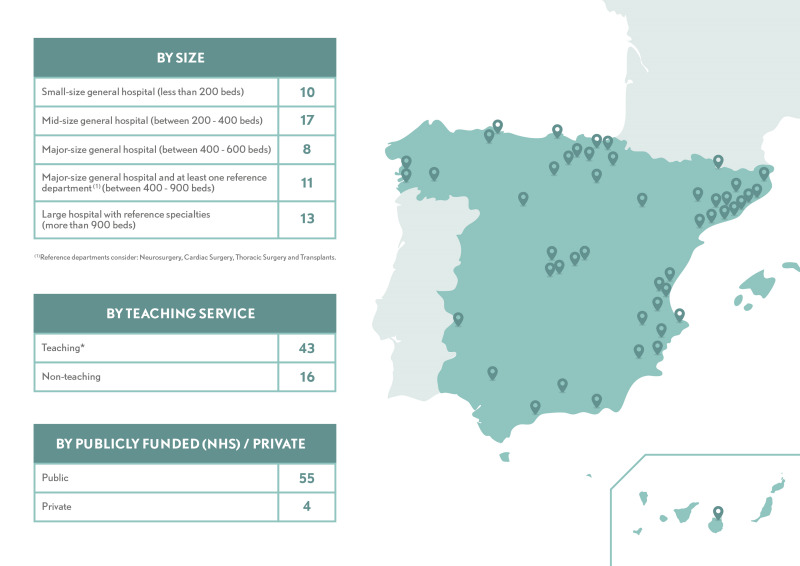

MAPBM implementation started in 2015 with the enrolment of eight hospitals, and by the end of 2019 it had reached a total of 59 hospitals. It has also had high recurrence, with 90% of enrolling hospitals continuing to participate during the following year (Figure 4). Participation in MAPBM is voluntary, so we did not select specific hospitals to create a nationally representative sample. Nonetheless, the current network covers diverse geographical regions, has a broad distribution of hospital size, and includes public, private, teaching, and non-teaching hospitals, all of which provides a solid picture of the hospital landscape in Spain (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Maturity Assessment for Patient Blood Management implementation roadmap

Figure 5.

Hospitals’ characteristics

DISCUSSION

Since its piloting in 2015, MAPBM has evolved as the standard framework for measuring PBM delivery in Spain, with a growing network of hospitals benchmarking their PBM performance annually. Over the past 5 years, it has helped a large number of hospitals in Spain to map the level of implementation of their PBM programmes and assess the results. As a tool for continuous improvement, it has allowed multi-professional PBM teams to identify gaps in terms of structure and processes in order to optimise outcomes across various populations of patients within hospitals. Benchmarking their performance against that of other hospitals also incentivises improvement throughout the hospital community. A further benefit is improved communication about PBM issues within and between hospitals, clinical teams and senior management. The growing number and continuous participation of hospitals highlights the increasing commitment of healthcare professionals and organisations in Spain to establishing PBM as a standard of care, and shows that they value the role of MAPBM in achieving this aim. This suggests that the number of participating hospitals that benefit from MAPBM will likely continue to grow, and even some hospitals from outside Spain have shown interest in using the MAPBM to start their own PBM network. In addition to the advantages of MAPBM for hospitals, it also provides information about the national status of Spain’s healthcare system in terms of current PBM standards and variability in clinical practice, information that is not readily available from healthcare authorities or institutions.

Previous work in this area

Assessment models and standards are common in health care, and some have even led to accreditation requirements for healthcare organisations. They generally measure the capacity of a given resource (structure) or the use of a best-practice clinical pathway (process), and focus to a lesser extent on clinical measuring and benchmarking. Another increasingly accepted type of standard focuses on measuring outcomes, but does not address the structural and process-related aspects. MAPBM considers all three perspectives –health outcomes, clinical processes and structure– and benchmarks clinical real-life data. We consider this approach an advantage, as it allows one to explain variations in outcomes in relation to changes in the processes and activities that affect them. In the field of PBM, between-hospital variability is generally assessed using transfusion rate. Few studies have also benchmarked other measures related to the use of PBM techniques10, 32. In 2017, the European Community published recommendations for health authorities and hospitals on how to implement a PBM programme, including a list of surveillance measures and KPI20 However, to our knowledge, there is no established set of KPI to assess PBM performance to date. Despite its limitations, the MAPBM is the first to provide a standard set of PBM KPI that have been effectively implemented and used as a reference by a large network of hospitals.

Limitations of the MAPBM

First, the model and its KPI were initially defined by a small group of experts. To obtain wider consensus, we did not follow a specific methodology (Delphi or similar), but rather held an annual working meeting during which the clinical leaders of participating hospitals discuss and adapt KPI, where appropriate. Second, while the model could have included many more process-related KPI, we chose those that can be feasibly measured from current EMR and structured health data in Spain. Third, we initially validated the link between the process KPI and the transfusion index using only the χ2 test, although recent rounds of analysis use multivariate regression; we will use this more powerful analysis strategy in future reports from the MAPBM. Fourth, the health outcomes in our model only consider clinical and economic outcomes, but not patient-reported outcomes (PRO) or experience (PRE). However, there is no current PBM evidence that recommends the use of PRO/PRE. Fifth, while our benchmarking methodology includes all risk-adjustments required for proper comparison, it does not account for mixed effects, which would be necessary to distinguish inter-hospital variability due to clinical practice from that due to chance. However, this is becoming less problematic as the volume of hospitals and episodes grows33.

Challenges we have faced

The main challenge in implementing the MAPBM has been to source patient-level data in the few hospitals without comprehensive EMR systems, even though the selected KPI for the model passed an initial test of data availability for an average hospital in Spain. The data gaps mainly affect outpatient treatments; laboratory values at certain points in the clinical pathway, especially during the interval between pre-operative treatment and admission; laboratory values immediately before a transfusion decision; and where point-of-care devices were not connected to the hospital EMR.

What this will allow us to do in the future

While the MAPBM’s main purpose is to assist hospitals in adopting and improving PBM and patients’ outcomes, it also creates other opportunities, some of which have already become apparent in these first 5 years. First, MAPBM scores are becoming a reference in Spain for identifying the best PBM-performing hospitals. Second, MAPBM data on current PBM clinical practice is helping healthcare authorities to oversee and audit. Third, the MAPBM’s large volume of homogenous PBM measures and outcomes for nearly 60 hospitals and >180,000 episodes to date creates opportunities for research on PBM and patients’ safety.

CONCLUSIONS

The MAPBM initiative translates PBM clinical recommendations and best practices, into a set of quantifiable KPI to facilitate hospitals with measuring and benchmarking their PBM clinical pathways and outcomes. Its implementation has proven to be feasible in a large and growing number of hospitals in Spain, providing them with an ongoing scorecard to assess their PBM performance. It is hoped that the MAPBM becomes a useful tool for healthcare organisations to implement PBM programmes and improve patients’ safety and outcomes.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors are extremely grateful to the following collaborators for their generous contributions: Arturo Pereira PhD, in the initial design of the assessment model; Mrs Marta Albacar in the definition of KPI; Gavin Lucas PhD who helped us to plan and polish the article and provided his critique; Ms. Eulalia Obrador, the programme assistant; and many other hospital doctors and information systems staff, who assisted in the implementation of the MAPBM in their hospitals during these past 5 years.

APPENDIX 1

*MAPBM Working Group (key hospital leaders’ affiliations in order of years of participation and alphabetically)

Luís Enrique Fernández Rodríguez, Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. Ana Abad Gosálbez, Hospital de Dénia Marina Salud. Ana Peral/Ino Fornet, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro. Xavier Soler, Centro Médico Teknon. Teresa Planella, Consorci Hospitalari de Vic. Paloma Ricos, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme. Rosa Goterris, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia. Luis Olmedilla, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón. Carles Jericó, Hospital de Sant Joan Despí Moisès Broggi. Ana Morales, Hospital de Torrejón. José María García Gala, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias. Virginia Dueñas, Hospital Universitario de Burgos. Carmen Fernández, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes. Raquel Tolos, Hospital Universitari Germans Trías i Pujol. Maria Angeles Villanueva, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. Concha Cassinello, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Ignacio Fuente Graciani, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid. Sonsoles Aragon, Hospital de la Ribera. Maricel Subira, Hospital El Pilar. Violeta Turcu, Hospital POVISA, S.A. Dolores Vilariño, Hospital Universitario de Santiago. Elena Zavala, Hospital Universitario Donostia. Luz María González, Hospital Universitario Gran Canaria Dr Negrín. Gemma Moreno, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Silvia Ruiz de Gracia, Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor. Almudena García, Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves. Antonio Pérez Gallofre, Hospital Verge de Meritxell. Paula Duque, Clínica Universitaria de Navarra. Luis López Sánchez, Complexo Hospitalario de Ourense. José Manuel Vagace, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Badajoz. Ángeles Medina, Hospital Costa del Sol. Mar Orts Rodríguez, Hospital de La Princesa. Ana Faura, Hospital de Viladecans. Lola Rosello, Hospital Doctor Peset. Eric Johansson, Hospital General de Catalunya. Pere Poch, Hospital General de Granollers. María A. Santamaría, Hospital Mas Magro. Montserrat López Rubio, Hospital Príncipe de Asturias. Irene Jara, Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe. Cristina Carmona, Hospital Universitario de Álava. Cristina Ramió Lluch, Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta. Martínez Almirante, Hospital Universitari de Tarragona Joan XXIII. Ángel Fernández López, Hospital Universitario de Torrevieja Vinalopo. Mila Caldes, Hospital Virgen de los Lirios Alcoy. Elvira Loureiro, Complexo Hospitalario de Pontevedra. Miguel Quintana, Hospital Comarcal del Alto Deba. Gonzalo Azparren, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. Jorge Puerta, Hospital de Poniente. Eva María Romero, Hospital de Manises. Ana Arroyo Rubio, Hospital de Tolosa (Clínica Asunción). Juan Santaella, Hospital de Zumárraga. Gabriel Cerdan, Hospital García Orcoyen. Rosalía Arbones, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova. Ángela Palacios, Hospital Universitario San Cecilio. Pilar Llamas, Hospital Universitario Jiménez Díaz.

Footnotes

FUNDING AND RESOURCES

The MAPBM project is currently funded by an unrestricted grant to IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute) from Vifor Pharma España S.L. The funder had no role in the definition of the assessment model, programme, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

EB and AGC conceived the presented idea. EB, AGC, JV and CI developed the assessment concept model and the implementation programme for hospitals. CI and LG defined and ran the analytical method. EB, McB, MJC and MB clinically validated the model. AH assessed and challenged the concept and findings of this project. All Authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

EB reports honoraria for lectures and/or travel support from Vifor Pharma, Sysmex, Takeda, OM Pharma and Zambon outside the submitted work. AGC was a Vifor Pharma employee at the time of starting to draft this manuscript. CI and LG are IQVIA employees. IQVIA was contracted by IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute) to support MAPBM project management, data processing and analytics. JV has nothing to disclose. McB reports having received travel support from Vifor Pharma España S.L. outside the submitted work. MB reports honoraria for lectures and travel support from Vifor Pharma outside the submitted work. MJC reports honoraria for lectures from Baxter, travel support and assistance to meetings from Vifor Pharma and CSL Bhering outside the submitted work. AH reports personal fees and travel support outside the submitted work from Instrumentation Laboratories Werfen (USA), Vifor Pharma International AG (Switzerland), Swiss Medical Network (Switzerland) and Celgene (Belgium); personal fees outside the submitted work from Vygon SA (France) and G1 Therapeutics (USA); and travel support outside the submitted work from South African National Blood Service (South Africa).

REFERENCES

- 1.Althoff FC, Neb H, Herrmann E, et al. Multimodal patient blood management program based on a three-pillar strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269:794–804. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthes E. Evidence-based medicine: save blood, save lives. Nature. 2015;520:24–6. doi: 10.1038/520024a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, et al. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on transfusion outcomes. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:232–46.e53. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet] Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. Oct, 2006. Most frequent procedures performed in U.S. hospitals, 2011: statistical brief #165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shander A, editor. Appropriate Blood Management. Procedings from the National Summit on Overuse; [Accessed on 20/03/2020.]. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/National_Summit_Overuse.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morton J, Anastassopoulos KP, Patel ST, et al. Frequency and outcomes of blood products transfusion across procedures and clinical conditions warranting inpatient care: an analysis of the 2004 healthcare cost and utilization project nationwide inpatient sample database. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:289–96. doi: 10.1177/1062860610366159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, et al. Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1396–407. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beattie WS, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Tait G. Risk associated with preoperative anemia in noncardiac surgery: a single-center cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:574–81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819878d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler AJ, Ahmad T, Phull MK, Allard S, Gillies MA, Pearse RM. Meta-analysis of the association between preoperative anaemia and mortality after surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1314–24. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Linden P, Hardy JF. Implementation of patient blood management remains extremely variable in Europe and Canada: the NATA benchmark project: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33:913–21. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller MM, Van Remoortel H, Meybohm P, et al. Patient blood management: recommendations from the 2018 Frankfurt Consensus Conference. JAMA. 2019;321:983–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Society for the Advancement of Blood Management. Five things physicians and patients should question. [Accessed on 22/05/2020.]. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/society-for-the-advancement-of-blood-management/

- 13.Hofmann A, Farmer S, Shander A. Five drivers shifting the paradigm from product-focused transfusion practice to patient blood management. Oncologist. 2011;16(Suppl 3):3–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S3-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shander A, Hofmann A, Isbister J, Van Aken H. Patient blood management-the new frontier. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2013;27:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franchini M, Marano G, Veropalumbo E, et al. Patient blood management: a revolutionary approach to transfusion medicine. Blood Transfus. 2019;17:191–5. doi: 10.2450/2019.0109-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leahy MF, Hofmann A, Towler S, et al. Improved outcomes and reduced costs associated with a health-system-wide patient blood management program: a retrospective observational study in four major adult tertiary-care hospitals. Transfusion. 2017;57:1347–58. doi: 10.1111/trf.14006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadana D, Pratzer A, Scher LJ, et al. Promoting high-value practice by reducing unnecessary transfusions with a patient blood management program. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:116–22. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farmer SLTK, Hofmann A, Semmens JB, et al. A programmatic approach to patient blood management – reducing transfusions and improving patient outcomes. Open Anesthesiol J. 2015;9:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHA. 6312 - Sixty-Third World Health Assembly. 2010. [Accessed on 20/3/2020.]. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/wha63/a63_r12-en.pdf.

- 20.Hofmann A, Nørgaard A, Kurz J, et al. Building national programmes of patient blood management (PBM) in the EU - a guide for health authorities. 2017. [Accessed on 20/03/2020.]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/blood_tissues_organs/docs/2017_eupbm_authorities_en.pdf.

- 21.Gombotz HH, Nørgaard AA, Kurt J. European Commission Supporting patient blood management (PBM) in the EU - a practical implementation guide for hospitals. 2017. [Accessed on 20/3/2020.]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/blood_tissues_organs/docs/2017_eupbm_hospitals_en.pdf.

- 22.Shander A, Goobie SM, Warner MA, et al. The essential role of patient blood management in a pandemic: a call for action [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 31] Anesth Analg. 2020 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004844.. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leal-Noval SR, Munoz M, Asuero M, et al. Spanish Consensus Statement on alternatives to allogeneic blood transfusion: the 2013 update of the “Seville Document”. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:585–610. doi: 10.2450/2013.0029-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shander A, Van Aken H, Colomina MJ, et al. Patient blood management in Europe. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:55–68. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colomina MJ, Basora Macaya M, Bisbe Vives E. [Implementation of blood sparing programs in Spain: results of a survey of departments of anesthesiology and resuscitation]. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2015;62(Suppl 1):3–18. doi: 10.1016/S0034-9356(15)30002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz M, Gomez-Ramirez S, Kozek-Langeneker S, et al. ‘Fit to fly’: overcoming barriers to preoperative haemoglobin optimization in surgical patients. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:15–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer DP, Zacharowski KD, Muller MM, et al. Patient blood management implementation strategies and their effect on physicians’ risk perception, clinical knowledge and perioperative practice - the frankfurt experience. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42:91–7. doi: 10.1159/000380868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meybohm P, Richards T, Isbister J, et al. Patient blood management bundles to facilitate implementation. Transfus Med Rev. 2017;31:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voorn VMA, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, van der Hout A, et al. Hospital variation in allogeneic transfusion and extended length of stay in primary elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014143. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gombotz H, Rehak PH, Shander A, Hofmann A. Blood use in elective surgery: the Austrian benchmark study. Transfusion. 2007;47:150–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abel G, Elliott MN. Identifying and quantifying variation between healthcare organisations and geographical regions: using mixed-effects models. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:1032–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-009165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.