Abstract

Background

Migration has impacted the spread of thalassaemia which is gradually becoming a global health problem. Italy, with an approximate estimation of 7,000 patients, does not have an accurate national record for haemoglobinopathies. This cross-sectional evaluation includes data for approximately 50% of beta-thalassaemia patients in Italy to provide an overview of the burden of thalassaemia syndromes.

Materials and methods

The analysis included data on epidemiology, transfusions and clinical parameters from 3,986 thalassaemia patients treated at 36 centres in Italy who were alive on 31st December 2017. The study used WebThal, a computerised clinical record that is completely free-of-charge and that does not have any mandatory fields to be filled.

Results

For patients with thalassaemia major, 68% were aged ≥35 years and 11% were aged ≤18 years. Patients with thalassaemia intermedia were slightly older. Transfusion data, reported in a subgroup of 1,162 patients, showed 9% had pre-transfusion haemoglobin <9 g/dL, 63% had levels between ≥9 and <10 g/dL, and 28% had levels ≥10 g/dL. These 1,162 patients underwent 22,272 transfusion days during 2017, with a mean of 19 transfusion days/year/patient (range 1–54 days). Severity of iron overload was reported in 756 patients; many had moderate or mild liver iron load (74% had liver iron <7.5 mg/g dry weight). In the same cohort, 85% of patients had no signs of cardiac iron load (MRT2* >20 ms), and only 3% showed signs of high-risk heart condition (T2* <10 ms). Most patients had normal alanine amino transferase levels due to treatment with the new anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) drugs.

Discussion

This study provides an overview of the current health status of patients with thalassaemia in Italy. Moreover, these data support the need for a national comprehensive thalassaemia registry.

Keywords: thalassaemia, epidemiology, transfusion, iron overload, medical records

INTRODUCTION

The thalassaemias are a group of genetic blood disorders characterised by abnormal haemoglobin production1. They are most prevalent in populations in the Southern Mediterranean, Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Africa. However, the advent of global migration has greatly expanded the spread of the disease beyond these geographical confines and thalassaemia is gradually becoming a more globalised health problem with important social implications2. Several countries have national registries, although their quality varies3. There are robust registries in countries with a relatively low number of patients, such as the United Kingdom (n=1,000)4 and France (n=400)5, whereas Italy, with an estimated 7,000 patients2, does not have an accurate national record for haemoglobinopathies. The recently published international comparison of thalassaemia registries3 included details of two independent regional Italian registries: the Italian Multiregional Thalassaemia Registry (HTA-Thal) recording some information about the tools and services available, and patient populations, and the Sicilian Registry for Thalassaemia and Haemoglobinopathies (ReSTE). The Italian Society for Thalassaemia and Haemoglobinopathies (SITE) started a survey with the scope of setting up an Italian network connecting regional reference centres, according to the provisions set out in Italian law (DPCM, 3 March 2017; www.site-italia.org).

The aim of the current project was to examine clinical information from a representative sample of Italian patients with thalassaemia. These data were collected using WebThal, a computerised clinical record created by a collaboration between clinicians and specialists in healthcare informatics. This tool has been specifically designed to support the clinical and scientific needs of thalassaemia centres, promoting proper and patient-tailored follow-up. WebThal software is available in Italy and has also been adopted by three thalassaemia centres in Brazil.

Several previous studies used data extracted from WebThal to report on prevalence and risk factors of the most common clinical complications and clinical management of patients with thalassaemia. One study6 investigated management of cardiovascular complications in 524 patients with thalassaemia major. It showed that approximately 19% of regularly transfused and chelated patients required cardiovascular medications, even if a part of this prescription was for preventive reasons, such as severe iron overload or lowering of left ventricular ejection fraction even within the normal range (an example of the importance of echocardiography in the monitoring of thalassaemia7). Another study8 evaluated the application of management standards and assessment of iron-overload in 924 thalassaemia major patients of all ages, and concluded that, in general, patients were receiving treatment in accordance with the guidelines available at that time. A large study conducted on 872 patients focusing on splenectomy9 showed a clinically significant reduction in the prevalence of this procedure with advances in transfusion management. Another recent paper10 presented a global review of transfusion-related complications, with some comparison between countries, including Italy.

A study11 using right heart catheterisation to evaluate the prevalence of pulmonary artery hypertension in a cohort of 1,309 thalassaemia patients identified via WebThal confirmed the presence of pulmonary artery hypertension in 2.1% of patients, and identified splenectomy and ageing as major risk factors for developing pulmonary hypertension. More recently, a study12 using WebThal data from 379 transfusion-dependent thalassaemia patients confirmed the association between iron overload and heart disease, identifying high ferritin levels as a main risk factor.

The aim of this current evaluation was to provide a contribution or a propaedeutic approach towards initiating a national registry for haemoglobinopathies in Italy. Specifically, by including data from the 36 thalassaemia centres in Italy currently using the WebThal computerised clinical record system, we aimed to create a snapshot of the current landscape of thalassaemia in Italy (since more than 50% of the estimated thalassaemia patients in Italy are included in WebThal), capturing epidemiological and clinical data, and offering an up-to-date overview of the burden of thalassaemia syndromes in Italy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All data are taken from the computerised clinical record WebThal 2.0 (see Online Supplementary Content for further details). This project, promoted by the Turin Centre, has expanded in recent years and there are now 36 Italian centres using WebThal completely free-of-charge and without minimum required data entering.

The current study was a cross-sectional evaluation of basic data entered into WebThal for all registered patients who were alive on 31st December 2017. Information on epidemiology, transfusions and clinical parameters were retrieved. Epidemiological data including age, diagnosis and centre of care were available for all patients from the 36 centres using WebThal. Thalassaemia intermedia was diagnosed in patients who did not require transfusions or who received them sporadically. Transfusion data included available data for the number of transfusion days per patient per year, number of red blood cell units transfused per patient per year, iron intake, and pre-transfusion haemoglobin levels. Transfusion data were available for patients receiving care in 11 centres currently using the WebThal software to record details about chronic transfusion therapy: Turin, Cagliari, Genova, Catania, Brindisi, Bari, Sassari, Iglesias, Nuoro, Siracusa, and Pisa. For serum alanine amino transferase (ALT) and total bilirubin, the median value of 2,017 was considered for each patient. For liver iron (liver iron concentration expressed as mg/g d.w.) and cardiac iron (MRI T2* in ms), the most recent result was reported.

In the evaluation of transfusion therapy, iron intake was calculated using the following formula:

Statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA for Windows (version 10, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Descriptive statistics are presented as means±standard deviation (SD), median (interquartile range) or percentages, as appropriate.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Epidemiology

A total of 3,986 patients with thalassaemia syndromes from 36 Italian centres were included in the analysis. The primary diagnosis was thalassaemia major in 3,149 patients (79%), thalassaemia intermedia in 696 patients (17%), and 141 patients (4%) had unspecified thalassaemia as the primary diagnosis. Overall 1,162 of 3,986 patients (29%) had clinical and transfusion therapy information entered in WebThal at December 2017 by centres using the tool routinely for transfusion therapy. Diagnostic characteristics of the sample are summarised in Table I. The geographical distribution of thalassaemia syndromes showed a strong prevalence in Northern Italy (39%) and the islands (41%), compared with the Southern regions (16%) and central Italy (4%). This analysis was based on the geographic location of the centre where the patient was treated.

Table I.

Characteristics of thalassaemia patients included in WebThal

| Age distribution according to primary diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of patients | Mean age (years) | Minimum age (years) | Maximum age (years) | Standard deviation | |

| Thalassaemia patients (all) | 3,986 | 38.1 | 0.26 | 94.7 | 13.9 |

| Thalassaemia major | 3,149 | 37.0 | 0.41 | 78.9 | 12.5 |

| Thalassaemia intermedia | 696 | 43.8 | 1.65 | 94.7 | 17.3 |

| Thalassaemia (unspecified) | 141 | 33.2 | 0.26 | 76.6 | 15.5 |

| Clinical and transfusion data | |||||

| N. of patients with recorded data | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation | |

| Transfusion days/year | 1,162 | 19.17 | 1.00 | 54.00 | 7.91 |

| PRBC units | 1,162 | 38.44 | 1.00 | 98.00 | 16.99 |

| Median pre-transfusional haemoglobin (g/dL) | 1,162 | 9.77 | 4.60 | 12.65 | 0.62 |

| Iron intake (mg/kg/day) | 1,057 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 1.70 | 0.14 |

| Median total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 971 | 2.00 | 0.22 | 11.87 | 1.41 |

| Principal complications reported in 1,167 patients | |||||

| Condition | N. of patients (%) | ||||

| Heart disease (unspecified) | 352 (30.2%) | ||||

| Hepatitis | 160 (13.7%) | ||||

| Cholelithiasis | 139 (11.9%) | ||||

| Hypothyroidism* | 111 (9.5%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 97 (8.3%) | ||||

| Nephrolithiasis | 57 (4.9%) | ||||

Hypothyroidism is not considered a major complication in thalassaemia. PRBC: packed red blood cells; N: number.

The age distribution of patients in the overall population (as of 31st December 2017) is shown in Figure 1. A similar age distribution was found in patients from different geographic areas.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age of patients with thalassaemia syndromes at 36 treatment centres in Italy

Including in the analysis only patients with thalassaemia major (n=3,149), the most severe form of the disease, a similar age distribution was observed, with the majority of patients (60%) in the 35–50 years age group. Only 8% of patients with thalassaemia major were aged over 50 years. The mean age of patients with thalassaemia major was 37.0 years (range 0.41–78.9 years).

The age distribution of patients with thalassaemia intermedia (n=696) indicated a similar pattern shifted to the right, as expected due to differences in natural history (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of age of patients with thalassaemia intermedia at 36 treatment centres in Italy

Transfusion therapy

Chronic transfusion therapy has a major impact on quality of life and public health costs in thalassaemia13–16. All thalassaemia syndromes and all data reported during 2017 were included.

Eleven of the 36 thalassaemia treatment centres recorded information about transfusion therapy in WebThal; data are reported for this subgroup of patients from the overall population. The number of patients who had data reported about transfusion therapy and a summary of the data are presented in Table I.

Information on transfusion days was reported for 1,162 patients; the total number of transfusion days during 2017 was 22,272. The mean (SD) number of transfusion days reported during 2017 was 19.17 (7.9) days per patient (range 1–54 transfusion days).

The total number of units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) transfused during 2017 in the 1,162 patients with data reported was 44,665 units. The mean (SD) number of units transfused during 2017 per patient was 38.44 (16.9) (range 1–98 units of PRBC per year).

Information on iron intake was available in WebThal for 1,057 patients. For 5 patients, information about the quantity of blood transfused was missing, therefore it was not possible to calculate iron intake for all patients. Mean (SD) iron intake measured during 2017 was 0.42 (0.14) mg/kg/day (range 0.1–1.7 mg/kg/day).

Information on pre-transfusion haemoglobin levels was reported for 1,162 patients. The mean (SD) pre-transfusion haemoglobin level was 9.7 (0.6) g/dL (range 4.6–12.6 g/dL). The majority of patients (63%) had a median pre-transfusion haemoglobin level in the range of ≥9 to <10 g/dL.

Clinical features

Eleven out of 36 thalassaemia treatment centres recorded information about clinical features in WebThal; therefore, data are only reported for this subgroup of patients.

Median serum levels of total bilirubin during 2017 were available for 971 of 1,162 patients, of whom 682 had thalassaemia major. Mean (SD) total bilirubin was 2.0 (1.41) mg/dL (range 0.22–11.87 mg/dL; normal range 0.10–1.5 mg/dL). Overall, 808 patients (83%) had median total bilirubin levels >1 mg/dL.

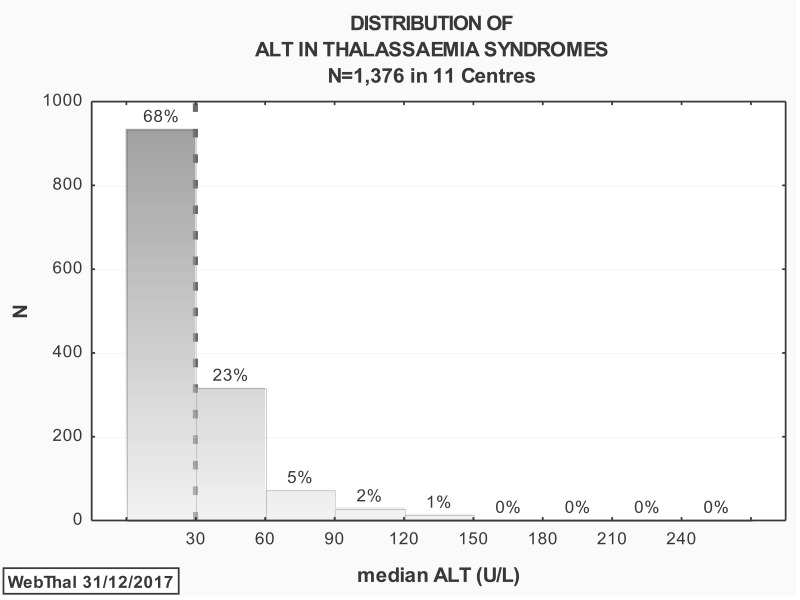

Median serum ALT levels during 2017 were available for 1,376 patients (Figure 3). The mean (SD) serum ALT was 30.3 (26.8) U/L (range 6.0–32 U/L; normal range 10–30 U/L). Overall, 441 (32%) of patients had a median serum ALT level >30 U/L during 2017.

Figure 3.

Distribution of median serum ALT levels during 2017 as reported in 1376 patients with thalassaemia syndromes treated at 11 centres in Italy

Dotted line shows upper limit of normal range (10–30 U/L).

Liver iron concentrations measured by Superconducting Quantum Interference Device or magnetic resonance imaging were reported for 756 patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of most recent liver iron concentration as reported in 756 patients with thalassaemia syndromes treated at 11 centres in Italy

Last values were recorded up to 31 December 2017. Dotted line shows upper limit of normal range (<2.1 mg/g dry weight).

The mean (SD) liver iron concentration was 6.1 (7.3) mg/g dry weight (range 0.8–44.0 mg/g dry weight; normal range <2.1 mg/g dry weight). For over half the patients (55%), the most recent liver iron concentration was ≥3.0 mg/g dry weight. Overall, 249 of 756 patients (33%) had liver iron concentration values within the normal range.

Cardiac T2* values are shown for the same cohort of 756 patients for whom liver iron concentrations were reported (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distribution of most recent heart T2* measurement as reported in the 756 patients for whom liver iron concentrations were also reported

Last values were recorded up to 31 December 2017. Dotted line shows lower limit of normal range (>20 ms).

Values for the most recent measurement of cardiac T2* were used; the cut-off date for the last measurement was 31st December 2017. The mean (SD) heart T2* value was 34.1 (12.6) ms (range 2.4–90 ms; normal range >20 ms). Overall, 15% of patients had a cardiac T2* value below the normal range.

The incidence of clinical complications was reported for 1,167 patients (Table I). Iron-related heart disease was the most frequent clinical complication, reported by just over 30% of patients with thalassaemia syndromes. Other major complications included hepatitis (13.7%), cholelithiasis (11.9%), diabetes (8.3%), and nephrolithiasis (4.9%).

Regarding the completeness of data considered in the study, the mean compilation rate achieved by the 11 centres was 93.0±4.8 % (range 82.9–98.4%).

DISCUSSION

This was a cross-sectional study using information from 36 thalassaemia treatment centres in Italy who used the WebThal computerised clinical record for thalassaemia in the absence of a national registry or centralised database. Only patients who were alive on 31st December 2017 were included. These 3,986 patients represent a significant proportion (>50%) of the total population of approximately 7,000 thalassaemia patients living in Italy at the time2.

There was an interesting age distribution among the WebThal population, with 68% of the thalassaemia major patients aged 35 years or more, while only 11% were in the paediatric age range. A negative selection bias for paediatric patients can be excluded since most of our centres deal with paediatric patients and co-ordinate regional programmes for the prevention of haemoglobinopathies. We believe that this age distribution is the result of the combination of at least two powerful long-standing drifts: (i) the improvement in survival with the wide application of iron chelation therapy and quality follow-up17,18; and (ii) the prevention programmes applied extensively in most Italian regions from the 1980s19, including those involved in this paper that cover north-western Italy and the islands. The age distribution in thalassaemia intermedia was similar but more advanced in comparison with recent reviews20,21. We suggest that this difference may be due to the fact that there is a great awareness of thalassaemia intermedia throughout Italy, allowing prompt diagnosis and appropriate management, including detection and treatment of iron overload.

Chronic haemolysis, liver iron overload, and impairment of cardiac function are some of the most important clinical consequences of thalassaemia in the long term, and are the principal causes of morbidity and mortality in this population18. Data on transfusion therapy and clinical complications were only reported at 11 of the 36 centres using WebThal. In addition, due to the flexible data reporting requirements, information was not reported for all patients for all parameters. The compilation rate was much higher for some parameters. For example, ALT data were reported for 1,376 patients whereas liver iron concentrations were only available for 756 patients. Despite these variations in patient numbers, WebThal is a useful source of information about thalassaemia patients. Chronic transfusion therapy has a huge impact on quality of life and public health cost in thalassaemia (approx. €400 per blood unit transfused)15,16,22,23. Pre-transfusion haemoglobin levels were in line with international guidelines24. Data reported for 1,162 patients showed that only 9% had pre-transfusion haemoglobin levels <9 g/dL, 63% had levels between 9 and 10 g/dL, and 28% had levels ≥10 g/dL. In contrast to countries where blood demand is still higher than blood availability, in Italy, the lower pre-transfusion haemoglobin level in a minority of patients is due to less severe genotype/phenotype as per guidelines. WebThal also enabled quantification of transfusion burden in terms of time spent by the patient undergoing transfusion therapy. Although transfusion data were only reported from 11 centres, it was estimated that the data for transfusion days was likely to be similar in the overall population due to implementation of a standardised transfusion protocol24. The transfusional iron intake results were in line with published data from large international series in clinical trials25.

In terms of iron overload severity, many of the 756 patients with reported data had acceptable hepatic iron levels (74% had a liver iron concentration <7.5 mg/g dry weight). Similarly, at the end of 2017, 85% of patients had no sign of cardiac iron load (MRT2* >20 ms), and only 3% of patients showed signs of a high-risk heart condition (T2* measurement <10 ms). These optimal results were supported by the introduction of freely available iron chelators by the Italian public health system in the 1970s.

It was also interesting to note that, in 2017, the majority of patients had normal ALT levels. This was mainly due to the fact that successful interferon-free hepatitis C antiviral therapy was rapidly introduced to Italian thalassaemia patients, following approval in 2016, due to age- and disease-related considerations26, 27.

The main limitation of the current study is that WebThal is not a centralised registry designed to provide epidemiological insight, but a comprehensive and free tool offered to thalassaemia centres to facilitate patient management in routine daily practice, without any stringent commitment to entering data. Consequently, the results of this study are a reflection of the degree of spontaneous application of a disease-specific clinical record by thalassaemia centres rather than an epidemiological survey. Nevertheless, we believe this study provides important insights into the thalassaemias by virtue of the number and distribution of patients and centres.

Indeed, considering the lack of formal registries for the disease in most countries, including Italy, we utilised data from a comprehensive, cost-free tool, and we evaluated the level of use and utility of this tool. The hypothesis that bigger centres would make more intensive use of the tool was not confirmed, mainly because the larger centres already had computerised recording systems in their hospitals. Small centres with less resources were highly motivated to use the tool. Moreover, the difference in compilation rate between the centres is not related to geographic area, dedicated staff or to the age of the patients followed.

CONCLUSIONS

This is a cross-sectional evaluation of epidemiological, transfusional and clinical data entered into WebThal on Italian thalassaemia patients who were alive on 31st December 2017. Despite its limitations, this report provides an overview of the current health status of patients with thalassaemia in Italy, which may be beneficial for public health assessment in terms of tailored treatment, avoidance of unnecessary procedures, and costs for the health care system. Moreover, while the WebThal dataset has been demonstrated to have an enormous potential, effort should be made to involve more centres and to support a more intensive use of this tool.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Authors would like to thank Alison Coletta, Principal Medical Writer, CROS NT, Verona, Italy for editorial support during the preparation of this manuscript.

The Authors would also like to thank: Gamberini M.R. (Ferrara), Peluso A. (Taranto), Sorrentino F. (Sant’Eugenio), Grimaldi S. (Crotone), Marinaro A.M. (Sassari), Murgia M. (Oristano), Perrotta S. (Napoli), Serra M. (Lecce), Massa A. (Olbia), Renni R.A. (Casarano), Dello Iacono N. (San Giovanni Rotondo), Palazzi G. (Modena)., Bonetti F. (Pavia), Manca E. (Alghero), D’Agostino G. (Gallipoli), Roccamo G. (Sant’Agata Militello), Putti M.C. (Padova), De Franceschi L. (Verona), Atzeni M. I. (San Gavino Monreale), Sau A. (Pescara), Mattei R. (Adria), Casini T. (Firenze), Toia M. (Legnano), Fidone C. (Ragusa)., for sharing data from their Centres.

Footnotes

FUNDING AND RESOURCES

Funding for medical writing support was provided by bluebird bio (Milan, Italy).

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept and design: FL, AP. Data acquisition: all Authors. Data analysis, or interpretation of data: FL, PC, AP. Drafting of the manuscript: FL, AP. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: FL, AP, MDC, GLF. Statistical analysis: AP. Administrative, technical, or material support: PC. Study supervision: AP.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

FL, GLF, MDC and AP received honoraria from bluebird bio. GLF MDC and AP received honoraria from Celgene and Novartis. GLF as ForAnemia foundation president, received research funds from bluebird bio.

The other Authors declare no conflicts of interest and have no disclosures for the content of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. The Thalassaemia Syndromes. 4th ed. Blackwell Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angastiniotis M, Vives Corrons JL, Soteriades ES, Eleftheriou A. The impact of migrations on the health services for rare diseases in Europe: the example of haemoglobin disorders. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:727905. doi: 10.1155/2013/727905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noori T, Ghazisaeedi M, Aliabad GM, et al. International Comparison of Thalassemia Registries: Challenges and Opportunities. Acta Inform Med. 2019;27:58–63. doi: 10.5455/aim.2019.27.58-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in beta-thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet. 2000;355:2051–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuret I, Pondarré C, Loundou A, et al. Complications and treatment of patients with β-thalassemia in France: results of the National Registry. Haematologica. 2010;95:724–29. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.018051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derchi G, Formisano F, Balocco M, et al. Clinical management of cardiovascular complications in patients with thalassaemia major: a large observational multicenter study. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12:242–46. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennell DJ, Udelson JE, Arai AE, et al. Cardiovascular function and treatment in β-thalassemia major: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:281–308. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b2be6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piga A, Longo F, Musallam KM, et al. Assessment and management of iron overload in beta-thalassaemia major patients during the 21st century: a real-life experience from the Italian WebThal project. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:872–83. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piga A, Serra M, Longo F, et al. Changing patterns of splenectomy in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:808–10. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah FT, Sayani F, Trompeter S, Drasar E, et al. Challenges of blood transfusions in β-thalassemia. Blood Rev. 2019;37:100588. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derchi G, Galanello R, Bina P, et al. on behalf of the WebThal Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Group. Prevalence and risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension in a large group of beta-thalassemia patients using right heart catheterization. A WebThal study. Circulation. 2014;129:338–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derchi G, Dessì C, Bina P, et al. Risk factors for heart disease in transfusion-dependent thalassemia: serum ferritin revisited. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:365–70. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1890-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabutti V. Current therapy for thalassemia in Italy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;612:268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb24314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonifazi F, Conte R, Baiardi P, et al. HTA-THAL Multiregional Registry. Pattern of complications and burden of disease in patients affected by beta thalassemia major. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1525–33. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1326890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepe A, Rossi G, Bentley A, et al. Cost-Utility Analysis of Three Iron Chelators Used in Monotherapy for the Treatment of Chronic Iron Overload in β-Thalassaemia Major Patients: An Italian Perspective. Clin Drug Investig. 2017;37:453–64. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scalone L, Mantovani LG, Krol M, et al. Costs, quality of life, treatment satisfaction and compliance in patients with beta-thalassemia major undergoing iron chelation therapy: the ITHACA study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1905–17. doi: 10.1185/03007990802160834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabutti V, Piga A. Results of long-term iron-chelating therapy. Acta Haematol. 1996;95:26–36. doi: 10.1159/000203853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgna-Pignatti C, Cappellini MD, De Stefano P, et al. Cardiac morbidity and mortality in deferoxamine-or deferiprone-treated patients with thalassemia major. Blood. 2006;107:3733–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monni G, Peddes C, Iuculano A, Ibba RM. From prenatal to preimplantation genetic diagnosis of β-thalassemia. Prevention model in 8748 Cases: 40 years of single center experience. J Clin Med. 2018;7:E35. doi: 10.3390/jcm7020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vichinsky E. Non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia and thalassemia intermedia: epidemiology, complications, and management. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:191–204. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1110128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben Salah N, Bou-Fakhredin R, Mellouli F, Taher AT. Revisiting beta thalassemia intermedia: past, present, and future prospects. Hematology. 2017;22:607–16. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2017.1333246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerra R, Velati C, Liumbruno GM, Grazzini G. Patient Blood Management in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2016;14:1–2. doi: 10.2450/2015.0171-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns KE, Haysom HE, Higgins AM, et al. A time-driven, activity-based costing methodology for determining the costs of red blood cell transfusion in patients with beta thalassaemia major. Transfus Med. 2019;29:33–40. doi: 10.1111/tme.12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Porter J, et al. Guidelines for the management of transfusion dependent thalassaemia. 3rd Edition. Nicosia (CY): Thalassaemia International Federation; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen AR, Glimm E, Porter JB. Effect of transfusional iron intake on response to chelation therapy in beta-thalassemia major. Blood. 2008;111:583–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Origa R, Ponti ML, Filosa A, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection with direct-acting antiviral drugs is safe and effective in patients with hemoglobinopathies. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1349–55. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangia A, Sarli R, Gamberini R, et al. Randomised clinical trial: sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassaemia and HCV genotype 1 or 4 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:424–31. doi: 10.1111/apt.14197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.