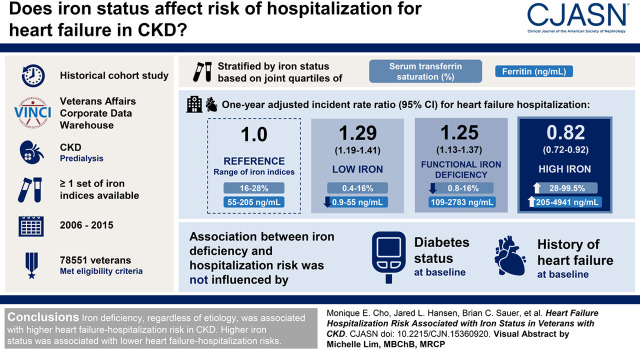

Visual Abstract

Keywords: iron, heart failure, veterans, hospitalization, chronic kidney disease, CKD

Abstract

Background and objectives

CKD is an independent risk factor for heart failure. Iron dysmetabolism potentially contributes to heart failure, but this relationship has not been well characterized in CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We performed a historical cohort study using data from the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse to evaluate the relationship between iron status and heart failure hospitalization. We identified a CKD cohort with at least one set of iron indices between 2006 and 2015. The first available date of serum iron indices was identified as the study index date. The cohort was divided into four iron groups on the basis of the joint quartiles of serum transferrin saturation (shown in percent) and ferritin (shown in nanograms per milliliter): reference (16%–28%, 55–205 ng/ml), low iron (0.4%–16%, 0.9–55 ng/ml), high iron (28%–99.5%, 205–4941 ng/ml), and function iron deficiency (0.8%–16%, 109–2783 ng/ml). We compared 1-year heart failure hospitalization risk between the iron groups using matching weights derived from multinomial propensity score models and Poisson rate-based regression.

Results

A total of 78,551 veterans met the eligibility criteria. The covariates were well balanced among the iron groups after applying the propensity score weights (n=31,819). One-year adjusted relative rate for heart failure hospitalization in the iron deficiency groups were higher compared with the reference group (low iron: 1.29 [95% confidence interval, 1.19 to 1.41]; functional iron deficiency: 1.25 [95% confidence interval, 1.13 to 1.37]). The high-iron group was associated with lower 1-year relative rate of heart failure hospitalization (0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.72 to 0.92). Furthermore, the association between iron deficiency and heart failure hospitalization risk remained consistent regardless of the diabetes status or heart failure history at baseline.

Conclusions

Iron deficiency, regardless of cause, was associated with higher heart failure hospitalization risk in CKD. Higher iron status was associated with lower heart failure hospitalization risks.

Introduction

CKD is an independent risk factor for heart failure (1). Recurrent heart failure hospitalization in the CKD population is associated with successive three-, four-, and six-fold higher likelihood of death before reaching kidney failure with each subsequent hospitalization, respectively (2). The mechanisms underlying the higher heart failure risk in CKD are incompletely understood. Abnormal iron metabolism, which is highly prevalent in CKD (3,4), is closely linked to development of heart failure (5–7). In particular, iron deficiency, an overlooked yet common comorbidity in chronic heart failure, has received much attention in recent years as an emerging therapeutic target in the general population (8). In CKD, hepcidin, a key hepatic iron regulator, is increased both by induction of inflammatory signaling and reduced clearance by the kidney. Hepcidin reduces intestinal iron absorption and mobilization of iron from reticuloendothelial stores (9). As a result, hepcidin mediates the development of functional iron deficiency, which can be seen when serum transferrin saturation is reduced when serum ferritin is normal or increased. Absolute iron deficiency, commonly defined by low transferrin saturation and ferritin levels, is thought to develop because of lower enteric iron absorption and more frequent bleeding and phlebotomy in CKD.

Although iron deficiency has recently become an important area of research for heart failure in the general population, there is a paucity of data describing the association between iron status and subsequent risk for heart failure in CKD. It is also unclear if the association between iron dysmetabolism and heart failure risk is different between patients with CKD with and without diabetes. Iron deficiency has been shown to impair glucose homeostasis in preclinical (10,11) and clinical studies (12,13), with a possible higher risk for diabetic complications (14). It is thus possible that abnormal iron metabolism is associated with greater cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD and diabetes.

To address the above knowledge gap, we have developed a historical cohort study using the Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), an informatics system that draws clinical and laboratory data from Veterans Health Administration facilities nationwide. The purpose of our study was to (1) assess heart failure hospitalization risk in abnormal iron groups with CKD, and (2) perform a secondary analysis to evaluate if the association between iron groups and heart failure differs between the diabetic and nondiabetic subgroups with kidney disease.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Design

We performed a historical cohort study using VINCI. The three major inclusion criteria were (1) CKD; (2) at least one set of available iron measurements of both ferritin and indices necessary for calculation of transferrin saturation (iron, transferrin, or total iron binding capacity [TIBC]) during the study period of 2006–2015; and (3) evidence of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care during the baseline period, defined for each patient as the year preceding the first available iron indices. The first available date of serum iron indices during the study period was identified as the study index date. Transferrin saturation (in percent) was calculated as serum iron concentration (in micrograms per liter)×100/TIBC (in micrograms per liter). If only iron and transferrin values were available, TIBC (in micrograms per liter) was calculated as transferrin (in milligrams per liter)×1.43. Transferrin saturation was then calculated as above. Diagnosis of CKD required two repeat values of estimated eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation (15), at least 90 days apart. The baseline eGFR for each included study participant was calculated by averaging two outpatient eGFR values most proximal to the index date.

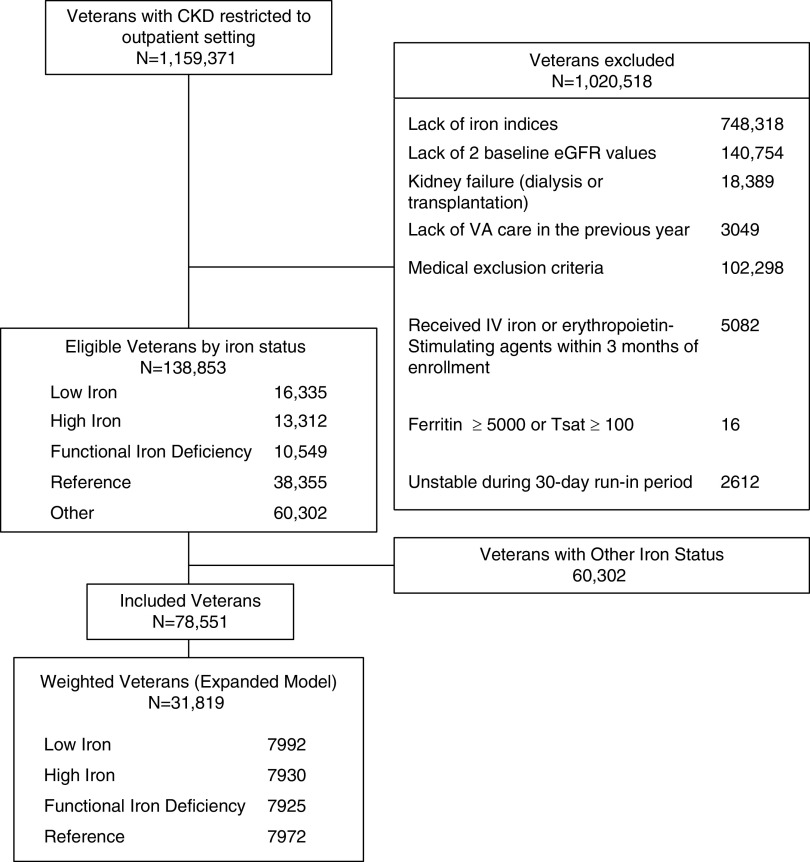

The exclusion criteria included (1) genetic hematologic disorders (thalassemia major and intermedia, sickle cell disease, and hemochromatosis); (2) disorders that affect iron metabolism or require chronic immunosuppressive therapy during the baseline period (active malignancy, gastrointestinal bleeding, organ transplantation, chronic viral hepatitis B or C, HIV, tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, and thyrotoxicosis); and (3) dialysis-dependent renal failure. To limit variability introduced by acute illnesses, we also excluded any laboratory values obtained in the inpatient setting. To account for errors in data collection, records with baseline transferrin saturation ≥100% or ferritin ≥5000 μg/L were excluded. In addition, we also excluded patients whose follow-up time ended during the first 30 days after the index date (the run-in period, n=2612), to account for acute medical events that may have precipitated assessment of iron status. Figure 1 describes the number of patients involved in each study phase, from eligibility to inclusion in the propensity model.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of study cohort inclusion and exclusion. IV, intravenous; Tsat, transferrin saturation; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Exposure Assessment

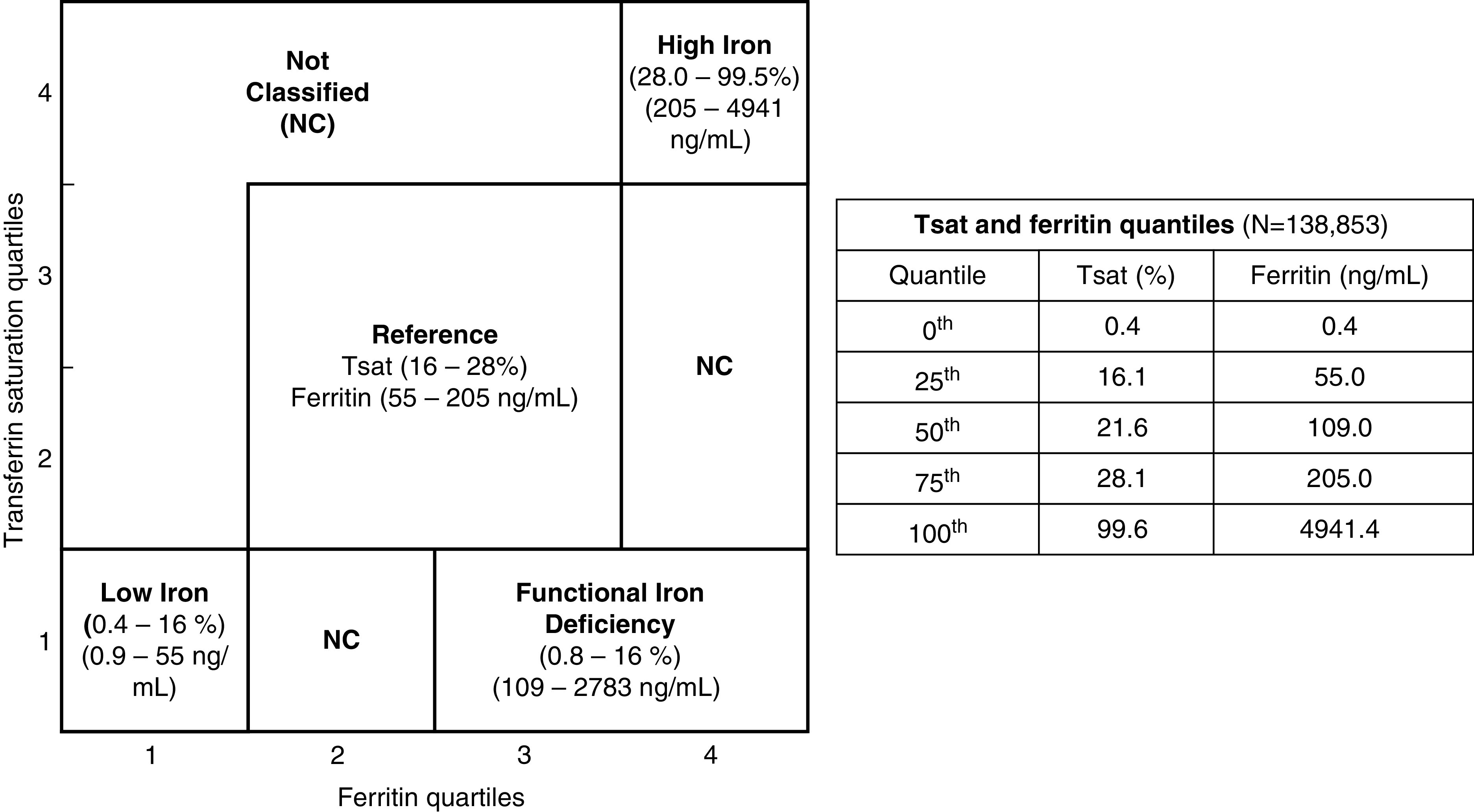

The exposure was serum iron status, assessed at a single time point of enrollment with serum transferrin saturation and ferritin levels. The final cohort was divided into four iron groups on the basis of the joint quartiles of transferrin saturation and ferritin (Figure 2). We decided not to use the conventional clinical thresholds to define iron groups because of (1) the need to use iron thresholds specific to our study cohort to establish four distinct, nonoverlapping iron groups; and (2) the lack of known iron thresholds to define iron overload in CKD.

Figure 2.

The definition of iron groups by joint transferrin saturation and ferritin quartiles (n=138,853). Four iron groups were established using quartiles of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin: reference, second and third quartiles of transferrin saturation and ferritin; low iron, first quartiles of transferrin saturation and ferritin; high iron, fourth quartiles of transferrin saturation and ferritin; and functional iron deficiency, first transferrin saturation quartile with third and fourth quartiles of ferritin. The ranges of transferrin saturation and ferritin values for each iron group are included. The table includes quartile thresholds of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin in the eligible cohort, including the excluded (not classified) subgroup.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was heart failure hospitalization during the first year after the index date. Other outcomes included heart failure hospitalization during the entire study period (2006–2015), and the composite of death or heart failure hospitalization during the first year after the index date and the entire study period. Hospitalizations at VA facilities or hospitalizations paid for by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services were considered for the primary outcome if they had a principal or primary diagnosis of heart failure, as identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). We identified heart failure ICD-9 codes according to the Clinical Classification Software Single Level Classifier 108 (congestive heart failure; nonhypertensive), except for ICD-9 code 398.91 (rheumatic heart failure). We used the following ICD-9 codes: 428.0, 428.1, 428.2[0–3], 428.3[0–3], 428.4[0–3], and 428.9. Only the first heart failure hospitalization after the index date was considered. The mortality outcome in VINCI was ascertained by reviewing four different sources: (1) VA Patient Transfer File, (2) Medicare Vital Status File, (3) Social Security Administration Death Master File, and (4) Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem.

Time at Risk

Time at risk included time to the end of the study period, first heart failure hospitalization, mortality date, or clinical loss to follow-up (the last date of care, or mortality date, preceding a 24-month gap in VA care).

Statistical Analyses

Missing clinical variables were considered missing at random and were imputed using multivariable imputation by chained equations via predictive mean matching (16,17).

Multinomial propensity models were developed as follows: using each imputed dataset, we fit a multinomial regression to estimate the probability of being classified according to a given iron status. Covariates included in this model were age, sex, race (Black/non-Black), and body mass index; and history of diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, arrhythmia (ICD-9 arrhythmia-related diagnosis codes), peripheral artery disease, and stroke; and relevant serum laboratory variables (eGFR, albumin, total cholesterol, total triglycerides, and HDL and LDL cholesterol). These covariates were chosen because they either affect iron status (demographics, baseline cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and eGFR, given that lower eGFR is associated with inflammation, as is low albumin) or the outcome (dyslipidemia).

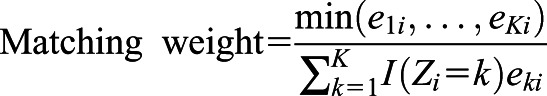

Using each imputed dataset’s propensity scores for each iron group, we calculated matching weight (18) for multiple groups by using the method described by Yoshida et al. (19). The matching weight was used to generate a population with common support (overlapping propensity scores) to evaluate the average effect of exposure on the outcome. For propensity scores  , representing the propensities for each of the k iron groups associated with the ith patient, the matching weight were calculated by dividing the minimum of the patient’s propensity scores by the propensity score of the patient’s observed iron group. The mean matching weight in the group that had the smallest unweighted sample size was used to assess the simultaneous common support. The equation for matching weight is presented below, where

, representing the propensities for each of the k iron groups associated with the ith patient, the matching weight were calculated by dividing the minimum of the patient’s propensity scores by the propensity score of the patient’s observed iron group. The mean matching weight in the group that had the smallest unweighted sample size was used to assess the simultaneous common support. The equation for matching weight is presented below, where  is the patient’s actual iron group and

is the patient’s actual iron group and  is 1 if the ith patient was in the kth iron group, and 0 otherwise.

is 1 if the ith patient was in the kth iron group, and 0 otherwise.

|

For each imputed dataset and covariate, we computed the standardized mean difference (SMD), a measure of distance between two group means. We calculated SMDs for each pair of iron groups, and the average of the absolute values of the SMDs across the six pairwise comparisons between iron groups (reference versus low iron, reference versus high iron, reference versus functional iron deficiency, low iron versus high iron, low iron versus functional iron deficiency, and high iron versus functional iron deficiency). SMDs of ≤0.10 are considered balanced (20). If continuous variables had an average SMD ≥0.10 across all imputed datasets after propensity score weighting, we transformed the variables, and the matching weight process was repeated until we achieved a reasonable balance. We also generated mirror histograms to ensure overlap of the propensity scores of the original and weighted samples (18).

After ensuring a region of common support, we fit a weighted Poisson rate-based regression for each imputed dataset, modeling the effect of iron group on heart failure hospitalization for the population with common support. This model included an offset of log time, which accounted for each patient’s study time at risk of heart failure, and was censored at death, loss to follow-up (defined as the date of a visit preceding a 2-year gap in care), or study end. We used robust SEM for confidence intervals, and hypothesis tests to provide conservative propensity score-based confidence intervals. To combine the imputed estimates into an overall effect estimate, we pooled the effect estimates to adjust SEM to account for variation between the imputed datasets. We assessed generalized linear model assumptions for the Poisson distribution by evaluating model dispersion (to determine if the model mean was equal to the variance), and if risk was homogeneous throughout the follow-up period (21). Our use of robust SEM assures our results are robust to slight violations of the dispersion assumption.

For the subgroup analysis, we examined differential associations of iron status with heart failure hospitalization between patients with and without diabetes by developing separate propensity-weighted Poisson models for patients with and without baseline diabetes. We assessed if the association between iron group and heart failure risk was modified by the diabetes status by using Wald tests of the homogeneity of effects. We applied the same steps to detect risk modification by baseline heart failure status.

Because competing events, such as death, may preclude the occurrence of the primary end point (heart failure hospitalization), we fit two additional models. The first model assessed the risk of death before heart failure hospitalization, and the second assessed the risk of the composite of heart failure and mortality. Cumulative incidence curves were generated to visualize these competing risks.

For the sensitivity analyses, we assessed the effects of possible confounding by clinical site by fitting a propensity score model that accounted for the effect of VA station (22). To assess the effects of excluding 2612 veterans during the first 30 days of follow-up, a sensitivity analysis including these veterans was performed. Additionally, we also repeated analyses using the commonly used conventional definitions of functional iron deficiency (transferrin saturation <20% and ferritin ≥100 ng/ml) and absolute iron deficiency (transferrin saturation <20% and ferritin <100 ng/ml) in CKD (23).

Three statistical programs were used for the analyses: R version 3.5.1, RStudio version 1.1.463, and SQL Server Management Studio version 17.4.

Results

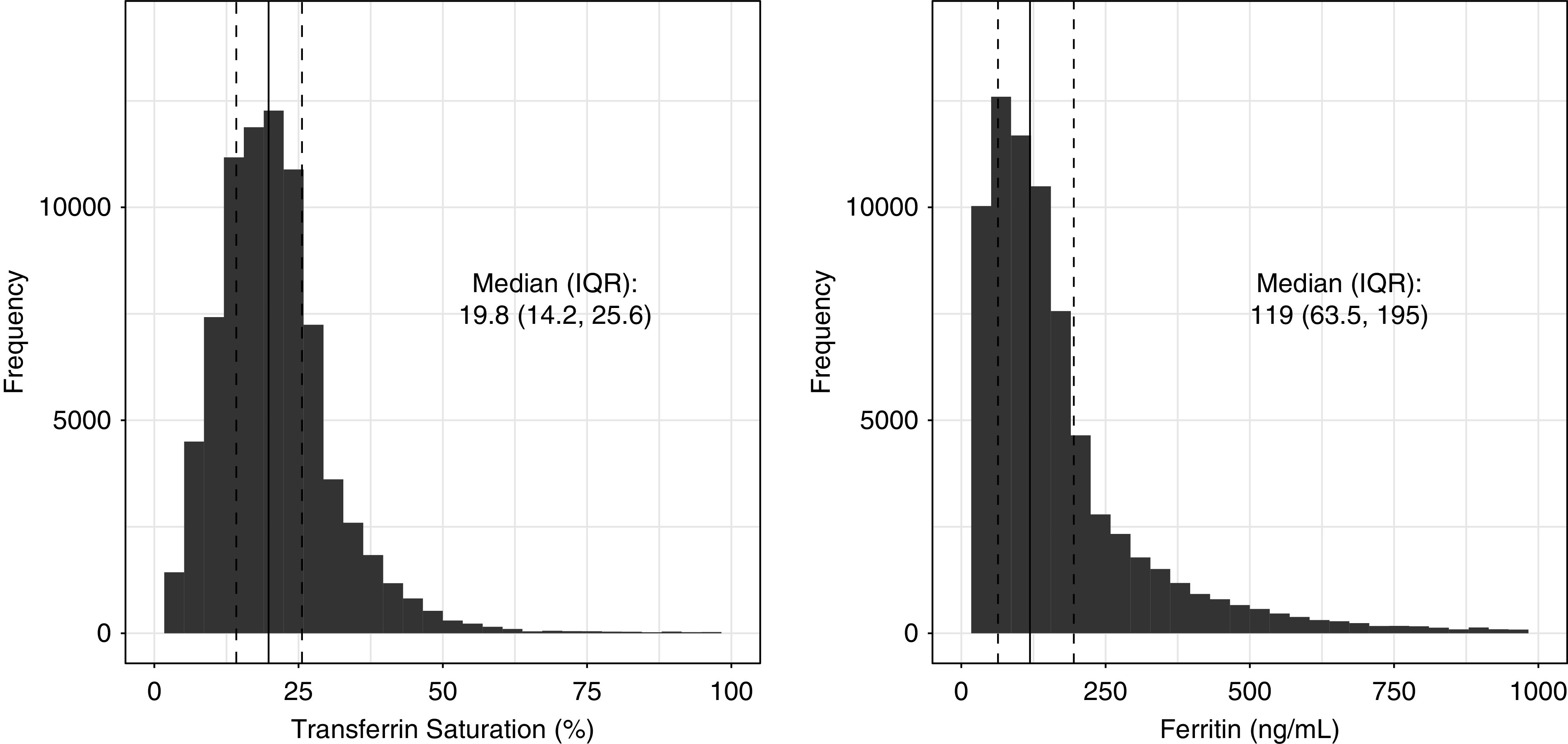

Of the total eligible veterans with CKD (n=138,853), 78,551 fell within reference (transferrin saturation range, 16%–28%; ferritin range, 55–205 ng/ml); low iron (transferrin saturation range, 0.4%–16%; ferritin range, 0.9–55 ng/ml); high iron (transferrin saturation range, 28%–99.5%; ferritin range, 205–4941 ng/ml); and functional iron deficiency (transferrin saturation range, 0.8%–16%; ferritin range, 109–2783 ng/ml) groups, using our cutoffs derived from joint quartiles of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin (Figure 2). The median transferrin saturation and ferritin values were 20% (interquartile range, 14%–26%) and 119 (interquartile range, 64–195) ng/ml, respectively (Figure 3). The remaining 60,302 veterans who did not fit into any of the iron categories were excluded from subsequent analyses. The excluded veterans had slightly lower burden of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, and mildly higher hemoglobin, eGFR, and serum albumin levels.

Figure 3.

The distribution of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin of the VINCI CKD cohort (n=78,551). The graphs depict distribution of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin values of the VINCI CKD cohort included for the analyses. IQR, interquartile range; VINCI, Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure.

The unadjusted baseline characteristics for the final study cohort of 78,551 veterans are described in Table 1. The mean±SD for age and eGFR were 72±11 years and 44±11 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. The prevalence for reference, low iron, high iron, and functional iron deficiency were 49%, 21%, 17%, and 13%, respectively. Low iron status had a lower proportion of Black race than the other iron groups. Iron deficiency groups had higher baseline prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. The mean±SD follow-up period of the cohort was 3.8±2.7 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the VINCI CKD cohort before propensity score weighting (n=78,551)

| Iron Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Reference, n=38,355 | Low, n=16,335 | High, n=13,312 | Functional Iron Deficiency, n=10,549 | Average SMDa |

| Transferrin Saturation Range, 16–28; Ferritin Range, 55–205 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 0.4–16; Ferritin Range, 0.9–55 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 28–99.5; Ferritin Range, 205–4941 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 0.8–16; Ferritin Range, 109–2783 | ||

| Follow-up, yr | 3.9 (2.7) | 3.6 (2.7) | 3.9 (2.7) | 3.5 (2.7) | b |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, yr | 72 (11) | 72 (10) | 72 (11) | 71 (11) | 0.084 |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 938 (2) | 833 (5) | 179 (1) | 273 (3) | 0.111 |

| Race, Black, n (%) | 3835 (10) | 1208 (7) | 1475 (11) | 1267 (12) | 0.084 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 (7) | 31 (7) | 29 (6) | 31 (7) | 0.155 |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 24,383 (64) | 10,491 (64) | 7296 (55) | 6906 (65) | 0.112 |

| CKD stage 3 | 33,470 (87) | 14,928 (91) | 11,486 (86) | 9018 (85) | 0.098 |

| CKD stage 4 | 4583 (12) | 1335 (8) | 1643 (12) | 1424 (13) | 0.088 |

| CKD stage 5 | 302 (0.8) | 72 (0.4) | 183 (1) | 107 (1) | 0.054 |

| Hypertension | 35,930 (94) | 15,105 (92) | 12,278 (92) | 9882 (94) | 0.036 |

| Heart failure | 8515 (22) | 4639 (28) | 2591 (19) | 3227 (31) | 0.153 |

| Coronary artery disease | 17,801 (46) | 8541 (52) | 5083 (38) | 5059 (48) | 0.148 |

| Arrhythmiac | 8259 (22) | 4189 (26) | 2527 (19) | 2574 (24) | 0.092 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5181 (14) | 3193 (20) | 1480 (11) | 1816 (17) | 0.135 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 6955 (18) | 3350 (21) | 1991 (15) | 2155 (20) | 0.083 |

| Stroke | 6553 (17) | 3041 (19) | 2019 (15) | 1809 (17) | 0.046 |

| Serum laboratory characteristics | |||||

| Transferrin saturation, % | 22 (19–25) | 11 (8–14) | 35 (31–41) | 13 (11–15) | b |

| Ferritin, ng/ml | 109 (80–147) | 24 (14–37) | 340 (259–494) | 186 (140–283) | b |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 43 (11) | 45 (10) | 43 (11) | 43 (11) | 0.124 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.6 (1.5) | 11.7 (1.7) | 12.6 (1.7) | 11.8 (1.6) | b |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 0.176 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 6.8 (1.4) | 6.8 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.3) | 6.8 (1.4) | b |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 159 (39) | 153 (38) | 163 (41) | 156 (41) | 0.146 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 158 (103) | 149 (94) | 159 (105) | 156 (104) | 0.057 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 41 (13) | 41 (13) | 43 (14) | 39 (12) | 0.136 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 88 (31) | 84 (30) | 90 (33) | 87 (32) | 0.096 |

Results expressed as mean (SD) or percent, except for transferrin saturation and ferritin, which are expressed as median (interquartile range). Missing proportions: body mass index, 18.4%; hemoglobin, 6.1%; serum albumin, 11.0%; hemoglobin A1c, 25.7%; serum total cholesterol, 8.1%; serum triglycerides, 9.3%; serum HDL cholesterol, 9.3%; and serum LDL cholesterol, 10.2%. VINCI, Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure; SMD, standardized mean difference.

A measure of distance between two group means in terms of one or more variables.

Not used in the model.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnoses pertaining to arrhythmia.

Average SMD after matching was <0.10 for all covariates, indicating adequate balance (Table 2). The unadjusted and weighted 1-year incidence rates of heart failure hospitalization for the iron groups, stratified by the diabetes status, are presented in Table 3. Regardless of the diabetes status, those with iron deficiency had higher incident rate per 100 patient-years. The excluded veterans (n=60,302) had a lower heart failure incidence rate at 4.6/100 patient-years compared with the overall rate for the study cohort (5.4/100 patient-years).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the VINCI CKD cohort after propensity score weighting

| Iron Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Reference | Low | High | Functional Iron Deficiency | Average SMDa |

| Transferrin Saturation Range, 16–28; Ferritin Range, 55–205 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 0.4–16; Ferritin Range, 0.9–55 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 28–99.5; Ferritin Range, 205–4941 | Transferrin Saturation Range, 0.8–16; Ferritin Range, 109–2783 | ||

| Follow-up, yr | 3.8 (2.7) | 3.7 (2.7) | 3.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.7) | b |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, yr | 71 (11) | 72 (11) | 72 (11) | 71 (11) | 0.016 |

| Sex, female, (%) | (2) | (2) | (2) | (2) | 0.002 |

| Race, Black, (%) | (10) | (10) | (11) | (11) | 0.008 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30 (6) | 30 (6) | 30 (6) | 30 (7) | 0.012 |

| Clinical characteristics, % | |||||

| Diabetes | 62 | 61 | 62 | 62 | 0.009 |

| CKD stage 3 | 87 | 88 | 87 | 87 | 0.009 |

| CKD stage 4 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 0.007 |

| CKD stage 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.023 |

| Hypertension | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 0.007 |

| Heart failure | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 0.006 |

| Coronary artery disease | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 0.006 |

| Arrhythmiac | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 0.003 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 0.006 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 18 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 0.007 |

| Stroke | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 0.004 |

| Serum laboratory characteristics, mean (SD) | |||||

| Transferrin saturation, % | 22 (19–25) | 11 (8–14) | 34 (31–40) | 13 (11–15) | b |

| Serum ferritin, ng/ml | 109 (80–147) | 24 (14–38) | 338 (259–491) | 187 (140–284) | b |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 43 (11) | 43 (11) | 43 (11) | 43 (11) | 0.006 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.6 (1.5) | 11.7 (1.7) | 12.5 (1.7) | 11.9 (1.6) | b |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 0.017 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 6.8 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.3) | 6.6 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.4) | b |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 157 (38) | 157 (39) | 157 (40) | 158 (40) | 0.004 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 156 (101) | 156 (100) | 156 (99) | 157 (106) | 0.007 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 40 (12) | 40 (12) | 40 (12) | 40 (12) | 0.004 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 87 (31) | 87 (31) | 87 (32) | 87 (32) | 0.003 |

Results expressed as mean (SD) or percent, except for transferrin saturation and ferritin, which are expressed as median (interquartile range). VINCI, Veterans Affairs Informatics and Computing Infrastructure; SMD, standardized mean difference.

A measure of distance between two group means in terms of one or more variables.

Not used in the model.

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnoses pertaining to arrhythmia.

Table 3.

Incidence rates for heart failure hospitalization during 1 year of follow-up, stratified by diabetes

| Iron Group | Patients, n | Time at Risk, Patient-Yr | Heart Failure Events, n | Incidence Ratea | Adjusted Incidence Rateb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire study cohort, n=78,551 | |||||

| Reference | 38,355 | 32,368 | 1518 | 4.7 | 5.1 |

| Low iron | 16,335 | 13,391 | 994 | 7.4 | 6.5 |

| High iron | 13,312 | 11,296 | 372 | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| Functional iron deficiency | 10,549 | 8530 | 661 | 7.7 | 6.3 |

| Diabetic cohort, n=45,968 | |||||

| Reference | 22,898 | 19,228 | 1072 | 5.6 | 5.9 |

| Low iron | 9950 | 8090 | 708 | 8.8 | 7.8 |

| High iron | 6623 | 5564 | 237 | 4.3 | 4.8 |

| Functional iron deficiency | 6497 | 5234 | 475 | 9.1 | 7.2 |

| Nondiabetic cohort, n=32,583 | |||||

| Reference | 15,457 | 13,140 | 446 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| Low iron | 6385 | 5301 | 286 | 5.4 | 5.0 |

| High iron | 6689 | 5733 | 135 | 2.4 | 3.1 |

| Functional iron deficiency | 4052 | 3296 | 186 | 5.6 | 5.0 |

Crude incidence rate refers to heart failure events per 100 patient-years, before adjustment with matching weight (crude heart failure/crude person-years×100).

Adjusted incidence rate reflects the heart failure incident rate per 100 patient-years, after applying the matching weights. Patients with diabetes have higher rates of subsequent heart failure hospitalization, but the association between iron deficiency and higher heart failure risk remains consistent in diabetic and nondiabetic subcohorts.

Iron deficiency groups were associated with higher heart failure hospitalization risk compared with the reference group at 1 year (low iron: incident rate ratio, 1.29; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.19 to 1.41; functional iron deficiency: incident rate ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.13 to 1.37; Table 4). The high-iron group, in contrast, exhibited significantly lower risk for heart failure hospitalization compared with the reference group (rate ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.92). The Wald tests of the homogeneity showed nonsignificant P values between diabetic and nondiabetic cohorts in all iron groups (P=0.89 for low iron; P=0.88 for high iron; and P=0.51 for functional iron deficiency), suggesting that diabetes status does not modify the association between iron groups and heart failure risk. In addition, the association between iron deficiency and heart failure risk also remained robust, regardless of the baseline heart failure history, although the heart failure incidence rate was higher in those with previous history of heart failure (Supplemental Table 1, A and B).

Table 4.

Incident rate ratios for heart failure

| Iron Group | 1-Year Relative Rate (95% CI) | Study Period (2006–2015) Relative Rate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Entire study cohort, n=78,551 | ||

| Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Low iron | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.41) | 1.16 (1.10 to 1.22) |

| High iron | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.91 (0.85, 0.97) |

| Function iron deficiency | 1.25 (1.13 to 1.37) | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) |

| Diabetic cohort, n=45,968 | ||

| Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Low iron | 1.31 (1.18 to 1.46) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) |

| High iron | 0.82 (0.71 to 0.94) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.02) |

| Function iron deficiency | 1.22 (1.08 to 1.37) | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.22) |

| Nondiabetic cohort, n=32,583 | ||

| Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Low iron | 1.29 (1.10 to 1.51) | 1.27 (1.16 to 1.39) |

| High iron | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.98) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) |

| Function iron deficiency | 1.31 (1.10 to 1.57) | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.35) |

Values presented pertain to the weighted population that results after applying the matching weights. The incidence rate ratios were calculated by dividing the incidence rates of each iron group by that of the reference group. To estimate adjusted incidence rate ratios, we used a propensity score-weighted Poisson regression. Wald tests of the homogeneity to assess effects of diabetes status on the association between iron groups and heart failure outcome at 1 year showed nonsignificant P values for all iron groups (P=0.89 for low iron; P=0.88 for high iron; and P=0.51 for functional iron deficiency between diabetic and nondiabetic cohorts). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

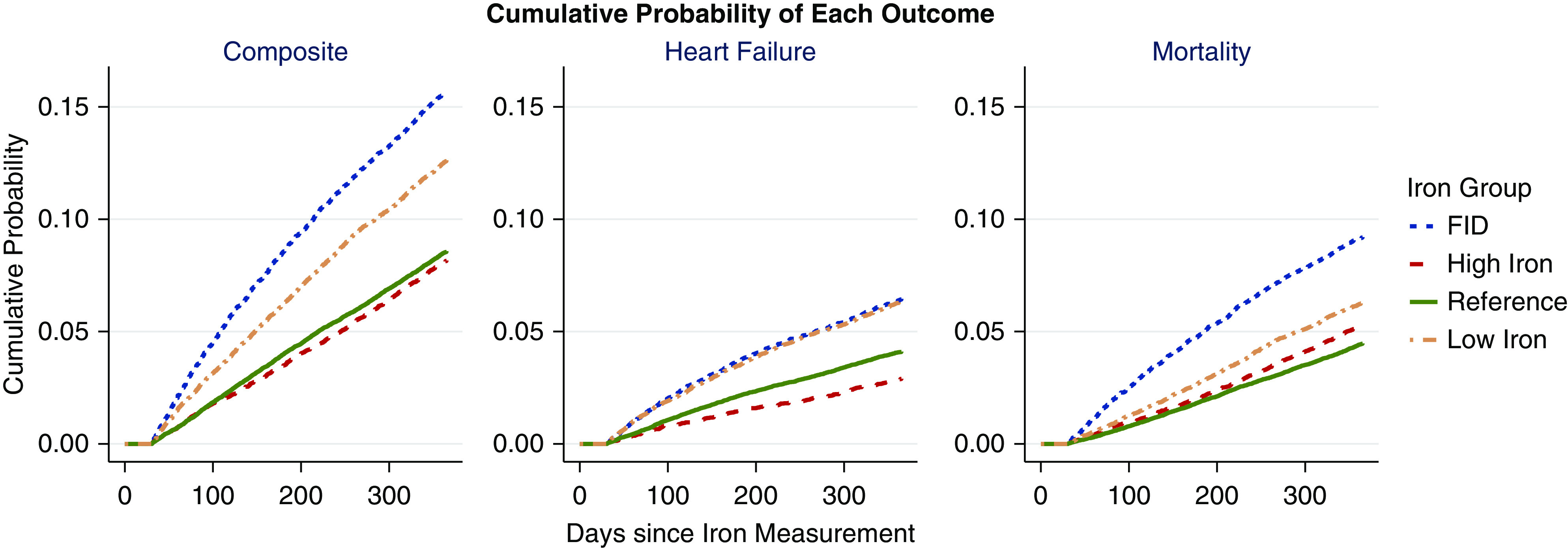

Because of the concern that mortality is a competing risk for the heart failure outcome, we also analyzed 1-year composite outcome of heart failure hospitalization or mortality before heart failure hospitalization (Figure 4). The estimated probability of having heart failure hospitalization was similar at >5% during the first year for both of the functional iron deficiency and low-iron groups, but the probability of death before heart failure hospitalization was higher for the functional iron deficiency group at any given follow-up time, compared with other iron groups. When the analyses were extended to include the entire study duration (2006–2015), the results were not qualitatively different from the 1-year analyses.

Figure 4.

The Kaplan–Meier curves comparing cumulative probability of heart failure hospitalization, mortality, and composite (heart failure or mortality) outcome: mortality and heart failure risk are higher with iron deficiency. Each panel depicts an outcome. The first panel depicts the composite of heart failure hospitalization and mortality, the second depicts heart failure hospitalization before mortality, and the third depicts mortality before heart failure hospitalization. The trend for each iron group is shown. Both functional iron deficiency (FID) and low-iron groups reach approximately 6% cumulative heart failure hospitalization during the first year of follow-up, but the probability of death is higher for functional iron deficiency at any given time compared with other iron groups.

To address the possibility that the variability in clinical practice across numerous VA clinical centers (n=129) could be a confounder, we also performed a matching weight analysis including clinical center as a covariate, to determine if the results were robust to potential center-level bias. The results remained qualitatively unchanged. Further, repeat analyses including the veterans excluded during the 30-day run-in period (n=2612) also did not change the results. Additionally, the analyses using the conventional definition of iron deficiency also yielded consistent results (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

This is the largest study to evaluate the association of serum iron indices with heart failure hospitalization in the CKD population. It is also the first study to assess and compare heart failure hospitalization risk associated with predefined, nonoverlapping iron groups derived from the joint measures of serum transferrin saturation and ferritin. An important observation from this study is that both types of iron deficiency are associated with higher risk for heart failure hospitalization, whereas higher iron indices are associated with lower subsequent heart failure risk. The results are consistent whether the quartile-based or conventional iron thresholds are used to define iron deficiency. Although the rate of heart failure hospitalization was higher in those with baseline history of diabetes or heart failure, our study suggests that neither modifies the association between iron status and subsequent heart failure risk in CKD. Given that hemoglobin was well-matched among the iron groups in our study, the differences in heart failure risk likely represent an effect of the iron group independent from anemia.

In recent years, there has been an increasing awareness of the prevalence of iron deficiency in patients with heart failure, involving about 50% of patients with heart failure (24). Iron deficiency is an independent predictor of symptom severity, exercise tolerance, and quality of life, irrespective of hemoglobin status in heart failure (24–26). In a prospective observational study of 546 patients with systolic heart failure, iron deficiency (defined as ferritin <100 μg/L, or 100–300 μg/L with transferrin saturation <20%), but not anemia, was associated with 58% higher risk for death or heart transplantation (26). Several small clinical studies have reported that intravenous iron was associated with improved exercise capacity, quality of life, New York Heart Association functional class, and left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency (27–29). A recent meta-analysis by Jankowska et al. (30), evaluating the results from five randomized controlled trials involving a total of 851 patients with heart failure (28,29,31–33), reported that intravenous iron therapy improves quality of life, exercise capacity, and clinical outcomes, independent of concomitant anemia. Furthermore, intravenous iron significantly ameliorated the risk of cardiovascular hospitalization, heart failure hospitalization, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality. Our study corroborates these findings and suggests a potential target to mitigate heart failure risk in the CKD population.

Our study has several important limitations. Because we enrolled only those who were categorized into four iron groups, 43% of the veterans with CKD were removed from the dataset. Our results are thus applicable only to those whose iron indices fall within the study cutoff values. In addition, we realize that the use of transferrin saturation and ferritin to determine iron groups is arbitrary and may not accurately depict the true iron status, given that serum indices of iron may have limited utility identifying bone marrow (34) or other tissue iron levels. Importantly, the observational nature of the study does not allow for causal interpretation between iron status and the heart failure outcome. Given the use of iron indices only at baseline, we are also unable to determine the effect of exposure duration. Further, the use of medications that affect iron status (such as iron replacement therapy or erythropoietin) during the study has not been incorporated into the analyses.

In conclusion, both functional and absolute iron deficiency are independent predictors of heart failure hospitalization in the CKD population. Our results have important implications for the current iron management in CKD, which focuses primarily on achieving target hemoglobin levels without giving much attention to the effects of iron on other organs. Early detection of iron status may improve cardiovascular risk assessment and potentially allow optimization of modifiable risk factors in CKD. Future randomized trials are needed to establish efficacy and safety of iron repletion on hard end points, including heart failure hospitalization and mortality, especially in the CKD population.

Disclosures

A. Agarwal reports employment with University of Utah and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salt Lake City; and membership with the American Society of Nephrology. A.K. Cheung reports employment with University of Utah and Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Healthcare System; consultancy agreements with Boehringer-Ingelheim, Calliditas, and UpToDate; ownership interest with Merck; honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Calliditas, and UpToDate; serving as a scientific advisor or member of JASN, Hong Kong Journal of Nephrology, and Kidney Diseases; and other interests/relationships with Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. M.E. Cho reports employment with University of Utah and honoraria from UpToDate. T. Greene reports employment with University of Utah; consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Invokana, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc; and research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, and Vertex. J.L. Hansen reports employment with University of Utah and Veterans Health Administration. B.C. Sauer reports employment with Salt Lake City VA Medical Center and University of Utah; consulting with 3Dcommunication (<$10,000); and past research funded by Amgen and Collaborative Healthcare Research & Data Analytics.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Services and the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services & Research Center of Innovation in Salt Lake City, Utah (VA Merit Review Award CX001566-01A1, awarded to M.E. Cho).

Data Sharing Statement

Data are not publicly available. All data are available by request from the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government. The funders of this study had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “A New View of Iron Management in Heart Failure: What Nephrologists Need to Know,” on pages 502–504.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.15360920/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. (A) Incidence rates for heart failure hospitalization during 1-year of follow-up, stratified by the baseline heart failure history. (B) Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) for heart failure hospitalization during 1-year follow-up period, stratified by the baseline heart failure history.

Supplemental Table 2. Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) for heart failure hospitalization during 1-year follow-up period, using two definitions of iron deficiency.

References

- 1.Kottgen A, Russell SD, Loehr LR, Crainiceanu CM, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Chambless LE, Coresh J: Reduced kidney function as a risk factor for incident heart failure: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1307–1315, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sud M, Tangri N, Pintilie M, Levey AS, Naimark DM: ESRD and death after heart failure in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 715–722, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishbane S, Pollack S, Feldman HI, Joffe MM: Iron indices in chronic kidney disease in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey 1988-2004. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 57–61, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovesdy CP, Estrada W, Ahmadzadeh S, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of markers of iron stores with outcomes in patients with nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 435–441, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anand IS, Gupta P: Anemia and iron deficiency in heart failure: Current concepts and emerging therapies. Circulation 138: 80–98, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gujja P, Rosing DR, Tripodi DJ, Shizukuda Y: Iron overload cardiomyopathy: Better understanding of an increasing disorder. J Am Coll Cardiol 56: 1001–1012, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Zhabyeyev P, Wang S, Oudit GY: Role of iron metabolism in heart failure: From iron deficiency to iron overload. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1865: 1925–1937, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Solal A, Leclercq C, Deray G, Lasocki S, Zambrowski JJ, Mebazaa A, de Groote P, Damy T, Galinier M: Iron deficiency: An emerging therapeutic target in heart failure. Heart 100: 1414–1420, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganz T, Nemeth E: Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 1434–1443, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borel MJ, Smith SH, Brigham DE, Beard JL: The impact of varying degrees of iron nutriture on several functional consequences of iron deficiency in rats. J Nutr 121: 729–736, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies KJ, Donovan CM, Refino CJ, Brooks GA, Packer L, Dallman PR: Distinguishing effects of anemia and muscle iron deficiency on exercise bioenergetics in the rat. Am J Physiol 246: E535–E543, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks AP, Metcalfe J, Day JL, Edwards MS: Iron deficiency and glycosylated haemoglobin A. Lancet 2: 141, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim C, Bullard KM, Herman WH, Beckles GL: Association between iron deficiency and A1C levels among adults without diabetes in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2006. Diabetes Care 33: 780–785, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soliman AT, De Sanctis V, Yassin M, Soliman N: Iron deficiency anemia and glucose metabolism. Acta Biomed 88: 112–118, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D; Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K: MICE: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 45: 1–67, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leyrat C, Seaman SR, White IR, Douglas I, Smeeth L, Kim J, Resche-Rigon M, Carpenter JR, Williamson EJ: Propensity score analysis with partially observed covariates: How should multiple imputation be used? Stat Methods Med Res 28: 3–19, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Greene T: A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis. Int J Biostat 9: 215–234, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida K, Hernández-Díaz S, Solomon DH, Jackson JW, Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Franklin JM: Matching weights to simultaneously compare three treatment groups: Comparison to three-way matching. Epidemiology 28: 387–395, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC: Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 38: 1228–1234, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luque-Fernandez MA, Belot A, Quaresma M, Maringe C, Coleman MP, Rachet B: Adjusting for overdispersion in piecewise exponential regression models to estimate excess mortality rate in population-based research. BMC Med Res Methodol 16: 129, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li F, Zaslavsky AM, Landrum MB: Propensity score weighting with multilevel data. Stat Med 32: 3373–3387, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas DW, Hinchliffe RF, Briggs C, Macdougall IC, Littlewood T, Cavill I; British Committee for Standards in Haematology: Guideline for the laboratory diagnosis of functional iron deficiency. Br J Haematol 161: 639–648, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klip IT, Comin-Colet J, Voors AA, Ponikowski P, Enjuanes C, Banasiak W, Lok DJ, Rosentryt P, Torrens A, Polonski L, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Jankowska EA: Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: An international pooled analysis. Am Heart J 165: 575–582.e3, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comín-Colet J, Enjuanes C, González G, Torrens A, Cladellas M, Meroño O, Ribas N, Ruiz S, Gómez M, Verdú JM, Bruguera J: Iron deficiency is a key determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure regardless of anaemia status. Eur J Heart Fail 15: 1164–1172, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jankowska EA, Rozentryt P, Witkowska A, Nowak J, Hartmann O, Ponikowska B, Borodulin-Nadzieja L, Banasiak W, Polonski L, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Anker SD, Ponikowski P: Iron deficiency: An ominous sign in patients with systolic chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 31: 1872–1880, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolger AP, Bartlett FR, Penston HS, O’Leary J, Pollock N, Kaprielian R, Chapman CM: Intravenous iron alone for the treatment of anemia in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 1225–1227, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okonko DO, Grzeslo A, Witkowski T, Mandal AK, Slater RM, Roughton M, Foldes G, Thum T, Majda J, Banasiak W, Missouris CG, Poole-Wilson PA, Anker SD, Ponikowski P: Effect of intravenous iron sucrose on exercise tolerance in anemic and nonanemic patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure and iron deficiency FERRIC-HF: A randomized, controlled, observer-blinded trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 103–112, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toblli JE, Lombraña A, Duarte P, Di Gennaro F: Intravenous iron reduces NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide in anemic patients with chronic heart failure and renal insufficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 1657–1665, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jankowska EA, Tkaczyszyn M, Suchocki T, Drozd M, von Haehling S, Doehner W, Banasiak W, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Ponikowski P: Effects of intravenous iron therapy in iron-deficient patients with systolic heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Heart Fail 18: 786–795, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anker SD, Comin Colet J, Filippatos G, Willenheimer R, Dickstein K, Drexler H, Lüscher TF, Bart B, Banasiak W, Niegowska J, Kirwan BA, Mori C, von Eisenhart Rothe B, Pocock SJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Ponikowski P; FAIR-HF Trial Investigators: Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. N Engl J Med 361: 2436–2448, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck-da-Silva L, Piardi D, Soder S, Rohde LE, Pereira-Barretto AC, de Albuquerque D, Bocchi E, Vilas-Boas F, Moura LZ, Montera MW, Rassi S, Clausell N: IRON-HF study: A randomized trial to assess the effects of iron in heart failure patients with anemia. Int J Cardiol 168: 3439–3442, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponikowski P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Comin-Colet J, Ertl G, Komajda M, Mareev V, McDonagh T, Parkhomenko A, Tavazzi L, Levesque V, Mori C, Roubert B, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, Anker SD; CONFIRM-HF Investigators: Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency. Eur Heart J 36: 657–658, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stancu S, Stanciu A, Zugravu A, Bârsan L, Dumitru D, Lipan M, Mircescu G: Bone marrow iron, iron indices, and the response to intravenous iron in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 55: 639–647, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.