Abstract

Following standard treatments, the traditional model for enhancing anti-tumor immunity involves performing immune reconstitution (e.g., adoptive immune cell therapies or immunoenhancing drugs) to prevent recurrence. For patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, we report here on two objectives, the immunosenescence for advanced non-small cell lung cancer and hydrogen gas inhalation for immune reconstitution. From July 1st to September 25th, 2019, 20 non-small cell lung cancer patients were enrolled to evaluate the immunosenescence of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, including T cell, natural killer/natural killer T cell and gamma delta T cell. Two weeks of hydrogen inhalation was performed during the waiting period for treatment-related examination. All patients inhaled a mixture of hydrogen (66.7%) and oxygen (33.3%) with a gas flow rate of 3 L/min for 4 hours each day. None of the patients received any standard treatment during the hydrogen inhalation period. After pretreatment testing, major indexes of immunosenescence were observed. The abnormally higher indexes included exhausted cytotoxic T cells, senescent cytotoxic T cells, and killer Vδ1 cells. After 2 weeks of hydrogen therapy, the number of exhausted and senescent cytotoxic T cells decreased to within the normal range, and there was an increase in killer Vδ1 cells. The abnormally lower indexes included functional helper and cytotoxic T cells, Th1, total natural killer T cells, natural killer, and Vδ2 cells. After 2 weeks of hydrogen therapy, all six cell subsets increased to within the normal range. The current data indicate that the immunosenescence of advanced non-small cell lung cancer involves nearly all lymphocyte subsets, and 2 weeks of hydrogen treatment can significantly improve most of these indexes. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuda Cancer Hospital, Jinan University in China (approval No. Fuda20181207) on December 7th, 2018, and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT03818347) on January 24th, 2019.

Keywords: adaptive and innate immune system, gamma delta T cell, hydrogen inhalation, immunosenescence, natural killer cell, natural killer T cell, non-small cell lung cancer, T cell

INTRODUCTION

The recurrence and metastasis of malignant tumors are difficult to control, which can be attributed to three main reasons: 1) immunosenescence; 2) tumor-associated factors; and 3) cancer therapy itself.1 Immunosenescence is characterized by the gradual deterioration of the immune system during the natural ageing process. A long-term tumor-bearing state will also lead to the exhaustion and senescence of cytotoxic lymphocytes, including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and gamma delta (γδ) T cells.2,3 Tumor factors are associated with an excessive tumor burden and severely inhibited immune function, including increased CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells.4 Currently, a variety of conventional treatments have been shown to accelerate the recurrence and metastasis of residual tumors, including surgery,5 radiation,6 chemotherapy,7 and even general anesthesia.8

Of all cancers, lung cancer is associated with the highest incidence throughout the world, of which non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of cases.9 Due to the lack of early symptoms for lung cancer, many patients are in an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis, and survival time is typically with 1 year.10 Studies have shown that nearly 27% of patients who underwent surgery and chemotherapy died from recurrence and metastasis.11 Thus, immune reconstruction, both before or after standard therapies, is a necessary method for prolonging the survival of cancer patients who are in an advanced stage.12 The current strategies of immune reconstruction primarily include adoptive immune cell supplementation, specific or non-specific immune activators, cancer vaccines, and exercise.13 As an antioxidant gas, hydrogen can diffuse into the mitochondria of lymphocytes and selectively neutralize oxygen free radicals.14,15 Moreover, hydrogen inhalation has been verified to reduce PD-1 expression, a marker of cell exhaustion,16 on the surface of cytotoxic T cells in patients with advanced colorectal cancer, which prolongs progression-free survival and overall survival.17 In this study, immunosenescence in advanced NSCLC patients was tested, and hydrogen inhalation was used to reverse the immunosenescence while patients were awaiting treatment.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

Between July and September 2019, 20 advanced NSCLC patients who hospitalized at Fuda Cancer Hospital and needed to wait 2 weeks for treatment were enrolled in this self-controlled study. According to the registered clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, ID: NCT03818347; Registration Date: January 24, 2019), the inclusion criteria consisted of: stage III or IV NSCLC diagnosed by imaging and pathology18; tumor number 1–6; maximum tumor length < 2 cm; Karnofsky performance status (KPS) score ≥ 7019; expected survival time > 6 months; platelet count ≥ 80 × 109/L; white blood cell count ≥ 3 × 109/L; neutrophil count ≥ 2 × 109/L; and hemoglobin ≥ 80 g/L. The exclusion criteria consisted of patients with a cardiac pacemaker, brain metastasis, grade 3 hypertension or diabetic complication, severe cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction. None of the patients received any standard treatment during the hydrogen inhalation period.

Ethical statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Fuda Cancer Hospital, Jinan University in China (approval No. Fuda20181207) on December 7, 2018. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Hydrogen inhalation method

Hydrogen was produced by a hydrogen-oxygen nebulizer (AMS-H-03, Shanghai Asclepius Meditec Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The patients remained seated or recumbent, and inhaled a mixture of hydrogen (66.7%) and oxygen (33.3%) via a nasal tube or mask with a gas flow rate of 3 L/min. The hydrogen inhalation was continued for 4 hours per day for 2 weeks in a specialized treatment facility.

Pulmonary symptoms and KPS score

Before and after hydrogen therapy, the respiratory function was assessed by very experienced respiratory physicians using a pulmonary function tester (Autospiro AS-507; Minato Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan), pulmonary tumor-related symptoms and the KPS score were evaluated by resident doctors in charge.

Immunophenotype evaluation

Approximately 5 mL of peripheral blood was extracted from elbow of all enrolled patients before hydrogen inhalation, as well as at one and two weeks after hydrogen inhalation. Peripheral blood monocyte cells were isolated using a Ficoll solution and labeled with fluorescent antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). T lymphocytes, NK, NKT, and γδ T cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (FACSanto II; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) by a professional third-party inspection center (Shuangzhi Purui Medical Laboratory Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei Province, China).

Statistical analysis

The calculation method of sample size is based on MedSci Sample Size tools (MSST) software (MedSci, Shanghai, China). Pulmonary symptoms before and after hydrogen inhalation were compared using paired t-test. Respiratory function, KPS score, and immunoassays were compared by repeated measures analysis of variance and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Statistical differences were indicated by P < 0.05. All analyses and figures were produced using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical data of NSCLC patients

A total of 20 consecutive patients admitted to the hospital participated in this study. The clinicopathological data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics information

| Parameters | Data |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 12(60) |

| Male | 8(40) |

| Age (yr) | |

| 41–60 | 5(25) |

| 61–70 | 6(30) |

| 71–80 | 9(45) |

| Pathological type of non-small cell lung cancer | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 9(45) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 8(40) |

| Large cell lung cancer | 3(15) |

| Cancer stage | |

| III | 7(35) |

| IV | 13(65) |

| Metastasis site | |

| Lung, mediastinum and pleura | 14(70) |

| Liver | 7(35) |

| Bone | 9(45) |

| Others | 5(25) |

Note: Data are expressed as number (percentage).

Changes in the KPS score and pulmonary symptoms of NSCLC patients

All patients underwent hydrogen inhalation for 2 weeks, with no treatment-related discomfort or side effects. The results regarding respiratory function, KPS score, and pulmonary symptoms before and 2 weeks after hydrogen therapy are presented in Table 2. At the end of hydrogen treatment, fewer people with different lung symptoms, with a statistical reduction in those with moderate cough and mild dyspnea.

Table 2.

Clinical findings in 20 non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing hydrogen therapy

| Before treatment | 2 wk after treatment | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced expiratory volume in one second (L) | 1.56±0.59 | 2.13±0.48 | < 0.05 |

| Forced vital capacity (L) | 1.93±0.57 | 2.38±0.53 | < 0.05 |

| Karnofsky performance status score | 75±6 | 88±7 | < 0.05 |

| Lung symptoms | |||

| Moderate cough | 13 | 5 | 0.0248 |

| Mild dyspnea | 11 | 4 | 0.0484 |

| Mild haemoptysis | 9 | 5 | 0.3203 |

| Chest pain | 8 | 4 | 0.3008 |

| Mild pleural effusion | 6 | 4 | 0.7164 |

| Lung bubble | 4 | 2 | 0.6614 |

Note: Data in the forced expiratory volume in one second, forced vital capacity and Karnofsky performance status score are expressed as the mean ± SD, and were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. Data in the lung symptoms are expressed as number and analyzed by paired t-test.

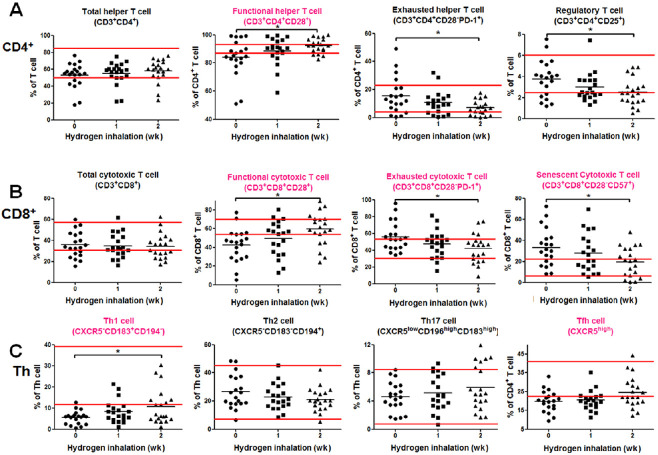

Changes in T cell subsets of NSCLC patients undergoing hydrogen therapy

This portion of the test consisted of three parts: CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and cytokine-secreting helper T (Th) cells. Before the initiation of hydrogen therapy, six primary immunosenescence indexes were identified. Among these indexes, the abnormally lower indexes included a percentage of functional helper and cytotoxic T cells, Th1, and follicular Th cells; the abnormally higher indexes were associated with the percentage of exhausted and senescent cytotoxic T cells (Figure 1). For the CD4+ subsets, functional Th cells increased to within the normal range after one week of hydrogen inhalation and increased significantly after 2 weeks (P < 0.05). Both exhausted Th cell and regulatory T cells decreased gradually (both P < 0.05) after 2 weeks of hydrogen therapy (Figure 1A). For the CD8+ subsets, functional cytotoxic T cells increased to within the normal range after 2 weeks of hydrogen inhalation (P < 0.05); both exhausted and senescent cytotoxic T cells decreased gradually to within the normal range (both P < 0.05) after 2 weeks of therapy (Figure 1B). For the cytokine-secreting Th subsets, only Th1 cells increased gradually near normal range after 2 weeks of hydrogen inhalation therapy (P < 0.05; Figure 1C). No other cells changed significantly within 2 weeks of hydrogen inhalation.

Figure 1.

An immunoassay of the T cell subsets before and after hydrogen inhalation in non-small cell lung cancer patients.

Note: (A) Test results of the CD4+ subsets. (B) Test results of the CD8+ subsets. (C) Test results of the cytokine-secreting CD4+ subsets. The parallel red long lines in the figure represent the normal range, the black short lines represent the average value at each time point, and the pink cell names represent the abnormal indicators before hydrogen treatment. Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05. CXCR5: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5; Th: helper T; Tfh: follicular helper T.

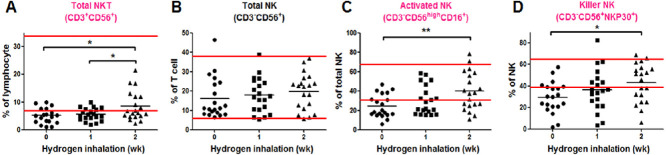

Changes in NKT and NK cells of NSCLC patients undergoing hydrogen therapy

Before the start of hydrogen therapy, the percentage of total NKT cell, activated NK and killer NK subsets was all below the normal range (Figure 2). One week after hydrogen inhalation, the activated NK cell subset increased to within the normal range (Figure 2C). Two weeks later, both the total NKT and killer NK subsets were higher than the percentage before treatment (both P < 0.05; Figure 2A and D), and activated NK cells were significantly elevated (P < 0.01; Figure 2C). Total NK cells did not change significantly within 2 weeks of hydrogen inhalation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Immunoassay of natural killer (NK)T and NK cells before and after hydrogen inhalation in non-small cell lung cancer patients.

Note: (A) Changes in the number of NKT cells. (B–D) Test results of the NK subsets. The parallel red long lines in the figure represent the normal range, the black short lines represent the average value at each time point, and the pink cell names represent the abnormal indicators before hydrogen treatment. Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

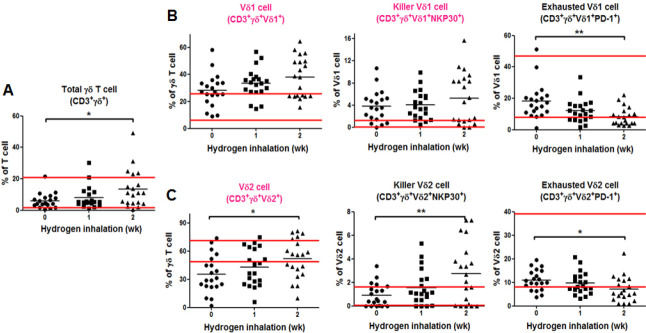

Changes in γδ T cell subsets of NSCLC patients undergoing hydrogen therapy

TBefore the start of hydrogen therapy, the percentage of both Vδ1 cell and killer Vδ1 cell was higher than the normal range, and the percentage of Vδ2 cell was below the normal range (Figure 3). One week after hydrogen inhalation, the percentage of Vδ2 cell in γδ T cells rose to within the normal range (Figure 3C). Two weeks later, the total γδ T cells and Vδ2 cells was higher than the percentage before treatment (both P < 0.05; Figure 3A and C), exhausted Vδ2 cell was lower than that before treatment (P < 0.05; Figure 3C); exhausted Vδ1 cell decreased significantly (P < 0.001; Figure 3B), and killer Vδ2 cell increased significantly (P < 0.01; Figure 3C). No other cells changed significantly within 2 weeks of hydrogen inhalation.

Figure 3.

Immunoassay of the gamma delta (γδ) T cell subsets before and after hydrogen inhalation in non-small cell lung cancer patients.

Note: (A) Change in the number of γδ T cells. (B) Test results of the Vδ1 subsets. (C) Test results of the Vδ2 subsets. The parallel red long lines in the figure represent the normal range, the black short lines represent the average value at each time point, and the pink cell names represent the abnormal indicators before hydrogen treatment. Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. NK: Natural killer ; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1.

DISCUSSION

Although a connection between immunodeficiency and oncogenesis has been proposed, a detailed immune profile in cancer has not yet been described in sufficient detail. It is well-known that the immune system deteriorates with cancer progression as a consequence of decreasing levels of functional T cells, downregulation of costimulatory molecules, and expansion of memory T cells.20,21 Chen et al.22 showed that there were differences in the immune profiles between cancer patients and normal subjects; in particular, a decreased proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets was observed in cancer patients, especially in patients who were associated with a more advanced disease stage and those who had received conventional chemotherapy treatment. In addition, Saavedra et al.23 reported that cancer and chemotherapy influenced the various lymphocyte subsets in NSCLC patients, in which B cells decreased with cancer disease progression, and CD28– subpopulations (exhausted or senescent T cells) increased following chemotherapy. Our study found similar results in the adaptive immune system, which was found to be primarily due to an increase in the proportion of exhausted and senescent T cell subsets, as well as a decreased proportion of functional subsets. Moreover, we also found evidence for the weak ability of Th1 and follicular Th cells on cytokine secretion. In the detection of the innate immune response (NK, NKT, and γδ T cells), we discovered that there was a decreased proportion of NKT, activated NK and killer NK cells, and an insufficient content of Vδ2 subsets among γδ T cells. Thus, it is highly likely that the adaptive and innate immune systems jointly contribute to the progression of NSCLC.

Advanced NSCLC has many characteristics that are distinct from other cancers, including that over 65% of patients are often over 70 years old24 and in most cases, the disease has progressed from early stage cancer and they have been exposed to long-term chronic antigenic stimulation.25 Therefore, the immunosenescence characteristics obtained in advanced NSCLC can only be used as a reference for other cancer types. Moreover, there may be huge differences among different cancer types, which require further investigation.

Immune cell senescence focuses on the phenotypic characteristics of individual lymphocytes; however, the function does not necessarily decrease during aging.26,27,28 In contrast, immune cell exhaustion is due to the presence of excessive free radicals in the mitochondria, which results in a loss of function and induces programmed apoptosis.29 Senescence and exhaustion are not simply the result of an inevitable and progressive decline of all immune functions, but rather represent a highly dynamic process of remodeling and adaptation.30 Thus, we attempted to rescue the function of exhausted and senescent lymphocytes with hydrogen gas, which was reported to protect the mitochondrial function of human lymphocytes.17,31,32 By comparing the immune function before and after hydrogen inhalation, we found that a period of two weeks was sufficient to reverse the multiple senescent or exhausted cell subsets into functional subsets, which had no effect on the percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. In addition to adaptive immune cells,17 both tumor killing-associated Th1 cytokines33 and innate immune cells (i.e., NK,34 NKT,35 total γδ T cell,36 Vδ1 cell,37 and Vδ238 cell) have been found to be significantly activated following hydrogen inhalation. Surprisingly, after hydrogen therapy, the proportion of regulatory T cells in the blood decreased significantly, demonstrating that hydrogen can control tumor progress with different mechanisms.39 Although the improvement in both the number and function of these cells does not necessarily reduce the size of the tumor, it may alter the systemic immunosuppressive state and the tumor microenvironment, as well as reduce tumor invasiveness. Improvements in the systemic signs and pulmonary symptoms after hydrogen inhalation in some patients are likely to validate this hypothesis.

Since most cancer patients need time to complete the admission check and wait for a specific treatment program, we should try to turn this “wasted time” into a “prime time,” in an effort to restore the immune system prior to hospital treatment. This study reports primary evidence that two weeks of hydrogen inhalation can significantly reverse the senescence of both the adaptive and innate immune system. The limitations of this paper are the small number of participants and the short time of hydrogen treatment, so the following issues remain unknown: 1) whether the duration of prolonged hydrogen inhalation can continue to improve immune function; 2) the optimal level of immune improvement; 3) whether the therapeutic effects rebound after the cessation of hydrogen inhalation; and 4) whether improving immune function before treatment will reduce tumor recurrence and metastasis. Such questions should be further investigated in future research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Financial support

None.

Institutional review board statement

This study protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Fuda Cancer Hospital of Jinan University on December 7, 2018 (approval No. Fuda20181207) and conformed to the specifications of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent statement

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patients or their legal guardians have given their consent for patients’ images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients or their legal guardians understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity.

Biostatistics statement

The statistical methods of this study were conducted and reviewed by the epidemiologist of Fuda Cancer Hospital of Jinan University.

Copyright transfer agreement

The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification (text, tables, figures, and appendices). Study protocol and informed consent form will be available immediately following publication, without end date. Results will be disseminated through presentations at scientific meetings and/or by publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Anonymized trial data will be available indefinitely at www.figshare.com.

Plagiarism check

Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review

Externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manjili MH. Tumor dormancy and relapse: from a natural byproduct of evolution to a disease state. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2564–2569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawelec G. Immunosenescence and cancer. Biogerontology. 2017;18:717–721. doi: 10.1007/s10522-017-9682-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarazona R, Sanchez-Correa B, Casas-Avilés I, et al. Immunosenescence: limitations of natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66:233–245. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1882-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer K, Cheng WC, Kreutz M, Ho PC, Siska PJ. Immunometabolism in cancer at a glance. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11:dmm034272. doi: 10.1242/dmm.034272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tohme S, Simmons RL, Tsung A. Surgery for cancer: a trigger for metastases. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1548–1552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Zhang L, Jiang Y, et al. Radiotherapy-induced cell death activates paracrine HMGB1-TLR2 signaling and accelerates pancreatic carcinoma metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:77. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0726-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramani VC, Vlodavsky I, Ng M, et al. Chemotherapy induces expression and release of heparanase leading to changes associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype. Matrix Biol. 2016;55:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekandarzad MW, van Zundert AAJ, Lirk PB, Doornebal CW, Hollmann MW. Perioperative Anesthesia Care and Tumor Progression. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:1697–1708. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Expert Panel on Thoracic Imaging. de Groot PM, Chung JH, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® noninvasive clinical staging of primary lung cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:S184–S195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan X, Jiao SC, Zhang GQ, Guan Y, Wang JL. Tumor-associated immune factors are associated with recurrence and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2017;24:57–63. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn OJ. Immuno-oncology: understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 8):viii6–viii9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, et al. Association of leisuretime physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:816–825. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelso GF, Porteous CM, Coulter CV, et al. Selective targeting of a redox-active ubiquinone to mitochondria within cells: antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4588–4596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrer MD, Sureda A, Tauler P, Palacín C, Tur JA, Pons A. Impaired lymphocyte mitochondrial antioxidant defences in variegate porphyria are accompanied by more inducible reactive oxygen species production and DNA damage. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:759–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamphorst AO, Wieland A, Nasti T, et al. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1-targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science. 2017;355:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akagi J, Baba H. Hydrogen gas restores exhausted CD8+ T cells in patients with advanced colorectal cancer to improve prognosis. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:301–311. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osmani L, Askin F, Gabrielson E, Li QK. Current WHO guidelines and the critical role of immunohistochemical markers in the subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): Moving from targeted therapy to immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thuluvath PJ, Thuluvath AJ, Savva Y. Karnofsky performance status before and after liver transplantation predicts graft and patient survival. J Hepatol. 2018;69:818–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9571–9576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503726102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen IH, Lai YL, Wu CL, et al. Immune impairment in patients with terminal cancers: influence of cancer treatments and cytomegalovirus infection. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:323–334. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0753-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saavedra D, García B, Lorenzo-Luaces P, et al. Biomarkers related to immunosenescence: relationships with therapy and survival in lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1773-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owonikoko TK, Ragin CC, Belani CP, et al. Lung cancer in elderly patients: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5570–5577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franceschi C, Valensin S, Fagnoni F, Barbi C, Bonafè M. Biomarkers of immunosenescence within an evolutionary perspective: the challenge of heterogeneity and the role of antigenic load. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:911–921. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanna A, Henson SM, Escors D, Akbar AN. The kinase p38 activated by the metabolic regulator AMPK and scaffold TAB1 drives the senescence of human T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:965–972. doi: 10.1038/ni.2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henson SM, Lanna A, Riddell NE, et al. p38 signaling inhibits mTORC1-independent autophagy in senescent human CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4004–4016. doi: 10.1172/JCI75051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbar AN, Henson SM, Lanna A. Senescence of T lymphocytes: implications for enhancing human immunity. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg AD, Agostinis P. Cell death and immunity in cancer: From danger signals to mimicry of pathogen defense responses. Immunol Rev. 2017;280:126–148. doi: 10.1111/imr.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulop T, Kotb R, Fortin CF, Pawelec G, de Angelis F, Larbi A. Potential role of immunosenescence in cancer development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1197:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Li B, Liu C, et al. Hydrogen-rich saline protects immunocytes from radiation-induced apoptosis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:Br144–148. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Gao F, Zhang H, et al. Molecular hydrogen protects human lymphocyte AHH-1 cells against 12C6+ heavy ion radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2013;89:1003–1008. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2013.817704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De La Cruz LM, Nocera NF, Czerniecki BJ. Restoring anti-oncodriver Th1 responses with dendritic cell vaccines in HER2/neu-positive breast cancer: progress and potential. Immunotherapy. 2016;8:1219–1232. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun C, Sun HY, Xiao WH, Zhang C, Tian ZG. Natural killer cell dysfunction in hepatocellular carcinoma and NK cell-based immunotherapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taniguchi M, Harada M, Dashtsoodol N, Kojo S. Discovery of NKT cells and development of NKT cell-targeted anti-tumor immunotherapy. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2015;91:292–304. doi: 10.2183/pjab.91.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao TL, Miao CH, Liao YJ, Chen YJ, Yeh CY, Liu CL. Ex Vivo Expanded Human Vγ9Vδ2 T-Cells Can Suppress Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1139. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davey MS, Willcox CR, Joyce SP, et al. Clonal selection in the human Vδ1 T cell repertoire indicates γδ TCR-dependent adaptive immune surveillance. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14760. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher JPH, Yan M, Heuijerjans J, et al. Neuroblastoma killing properties of Vδ2 and Vδ2-negative γδT cells following expansion by artificial antigen-presenting cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5720–5732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohue Y, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:2080–2089. doi: 10.1111/cas.14069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]