Abstract

PURPOSE:

Although the use of steroids in the management of COVID-19 has been addressed by a few systematic review and meta-analysis, however, they also used data from “SARS-CoV” and “MERS-CoV.” Again, most of these studies addressed only one severity category of patients or addressed only one efficacy endpoint (mortality). In this context, we conducted this meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of steroid therapy among all severity categories of patients with COVID-19 (mild to moderate and severe to critical category) in terms of “mortality,” “requirement of mechanical ventilation,” “requirement of ICU” and clinical cure parameters.

METHODS:

11 databases were screened. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or high quality (on the basis of risk of bias analysis) comparative-observational studies were included in the analysis. RevMan5.3 was used for the meta-analysis.

RESULTS:

A total of 15 studies (3 RCT and 12 comparative-observational studies) were included. In the mechanically-ventilated COVID-19 population, treatment with dexamethasone showed significant protection against mortality (single study). Among severe and critically ill combined population, steroid administration was significantly associated with lowered mortality (risk ratio [RR] 0.83 [0.76–0.910]), lowered requirement of mechanical ventilation (RR 0.59 [0.51–0.69]), decreased requirement of intensive care unit (ICU) (RR 0.62 [0.45–0.86]), lowered length of ICU stay (single-study) and decreased duration of mechanical ventilation (two-studies). In mild to moderate population, steroid treatment was associated with a higher “duration of hospital stay,” while no difference was seen in other domains. In patients at risk of progression to “acute respiratory distress syndrome,” steroid administration was associated with “reduced requirement of mechanical ventilation” (single-study).

CONCLUSION:

This study guides the use of steroid across patients with different severity categories of COVID-19. Among mechanically ventilated patients, steroid therapy may be beneficial in terms of reduced mortality. Among “severe and critical” patients; steroid therapy was associated with lowered mortality, decreased requirement of mechanical ventilation, and ICU. However, no benefit was observed in “mild to moderate” population. To conclude, among properly selected patient populations (based-upon clinical severity and biomarker status), steroid administration may prove beneficial in patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, meta-analysis, steroid

Introduction

Coronavirus are RNA viruses containing one of the largest RNA genome.[1] Spike protein and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor[2] interaction is the first event, which initiates membrane fusion and subsequent internalization of the RNA genome of the virus, and is a key event in the initiation of the infection.[3] The human infection by “SARS-CoV-2” is named coronavirus disease (COVID)-19. The disease is commonly classified into five severity categories: asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, and critical.[4] COVID-19 is proposed to be a triphasic disease: initial viral replication phase, immune-pathological damage phase, and pulmonary and/or other organ damage phase.[5]

Pattern recognition receptors (PRR e.g., toll-like receptors retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors, nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptors) play a major part in the initiation of the hyper-inflammatory response by recognizing virus-specific molecular signatures known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP).[6] Activation of PRRs owing to PAMP binding leads to activation of several signaling pathways, for example, NFkB, mitogen-activated protein kinase, interferon response factors, etc., NFkB axis activation[7] plays a major role in immune activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine release.[6] The cytokine storm is a result of activation of these various axis resulting in the sudden acute increase of pro-inflammatory cytokine release which includes etc interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha which contribute to organ damage and dysfunction.[6,8] Hyperactive host immune system response to SARS-CoV-2 results in excessive inflammatory discharge and the cytokine profiles correlates well with tissue damage, for example, lung failure, development of multi-organ failure status.[9]

Although many therapeutic interventions are proposed, for example, hydroxychloroquine,[10] remdesivir,[11] Fevipiravir,[12] lopinavir/ritonavir, etc.,[12] however, we need more evidence of efficacy for the same. The role of other agents in infection prevention (e.g., povidone-iodine) also needs to be evaluated in big-sized studies.[13,14]

As “cytokine storm” plays a major role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, more so in case of severe COVID-19 and critical COVID-19, immune-modulators, especially steroids started gaining importance in the management of COVID-19.[15] Steroids aim at suppressing the second phase of the disease and controlling the cytokine storm phase.[5] The idea of the use of steroids in COVID-19 dates back to the “SARS-CoV outbreak” in 2003[16] and “MERS-CoV outbreak” in 2012.[17] However many authors have questioned on the “safety and efficacy of corticosteroids” in SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2.[18] Again delayed viral clearance is also reported.[19] Many are of the opinion that a self-limiting course is observed for SARS even in patients with significant radiological changes and the use of steroids only increases the susceptibility to infection.[5] Hence, a detailed evaluation of the “safety and efficacy” of steroids is required in the settings of COVID-19. Again, SARS-CoV-2 is only 40%–94% genetically homologous to different structural components of SARS-CoV (ORF1ab, S, ORF3a, E. M, ORF6, N protein) and 35%–50% to MERS-CoV.[20] Again, many therapeutic agents found to be useful in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV failed to show their efficacy in COVID-19. Hence, data from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV cannot be directly attributed to SARS-CoV-2.

Although there are few systematic review,[21] and meta-analysis which evaluated the “safety and efficacy” of corticosteroids in COVID-19, most of them pooled data from “SARS-CoV” and “MERS-CoV.”[18,22,23,24] Again most of the earlier meta-analysis included poor-quality observational studies in their analysis. Another important factor is that in most of the studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of steroids, the severe patients were preferentially allocated to the steroid arm, which causes a baseline imbalance, especially in terms of severity. This hampers the proper interpretation of data, as the severe population is more at risk of disease progression and mortality. Hence, mortality in this more severe group cannot be attributed to the comparative failure of steroids. One recent meta-analysis published in JAMA[25] included few ongoing studies (data gathered from recruiting clinical trials through personal communication with study investigator by the WHO group and collected data from studies registered in “Chinese Clinical Trial Registry,” “ClinicalTrials.gov,” and the “EU Clinical Trials Register” and data collected up to April 6, 2020, data gathered through personal communications with individual study investigators) and included only critically ill patients, again many studies declined to participate for the participation in the metaanalysis as the studies were ongoing. Again, in the same meta-analysis, they have evaluated the safety and efficacy of steroids only in terms of “mortality”, not on other efficacy parameters. With this background, we conducted this current meta-analysis, where we included published high-quality studies (randomized controlled trials [RCT] and observational studies up to August, 2020) with special emphasis upon the “comparability” domain of Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) and included data only from COVID-19 population. Another factor is that we have evaluated the efficacy and safety of steroids across different severity groups separately (e.g., patients on mechanical ventilation, severe and critical patients combined, and mild and moderate patients combined). Compared to earlier metaanalysis, we have evaluated the efficacy and safety of steroids against a diverse range of clinically important endpoints, for example, mortality, the requirement of mechanical ventilation, requirement of intensive care unit (ICU), time to virological cure, duration of hospital stay, etc.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PROSPERO registration i.d. CRD42020203640).

Objectives

To evaluate the outcome of steroid therapy in terms of:

All-cause mortality

Requirement of mechanical ventilation

Requirement of ICU

Time to polymerase chain reaction negativity (virological cure)

Duration of hospital stay

Evaluation of the association between mortality and level of C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients receiving steroids.

Subgroup analysis

Mild-to-moderate patients

Severe and critical patients

Patients on mechanical ventilation

Efficacy of different steroids.

Comparisons

Steroid + standard of care (SOC) vs. SOC alone

Early steroid + SOC vs. SOC

High dose vs. standard dose of steroid.

Inclusion criteria

Observational studies, comparative clinical studies, or RCTs evaluating the comparative efficacy of steroid

Comparative evaluation of safety as well as the efficacy of steroids with respect to “SOC” or other pharmacotherapeutic options

Patient population: COVID-19.

Exclusion criteria

Poor quality studies with high risk of bias (on the basis of risk of bias evaluation, with special reference to comparability domain of NOS) were excluded. Only good and fair quality studies (on the basis of NOS) were included

Case series, case reports

Single group studies with no comparator.

Definitions

Pulse steroid therapy

Discontinuous high-dose intravenous corticosteroid therapy with prednisone ≥250 mg/day or its equivalent dose of another steroid for ≥1 day.[26]

Presymptomatic or asymptomatic patients

We adopted the severity definitions from NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines.[4] Patients with molecular diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 without any symptoms[4] were considered presymptomatic or asymptomatic category.

Mild disease

Patients with “molecular diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2” with mild clinical symptoms without “dyspnea,” “shortness of breath” or “abnormal chest imaging.”[4]

Moderate disease

Patients with SpO2 ≥94% on room air; however, there is evidence of lower respiratory disease (clinical or radiologic).[4]

Severe illness

Respiratory rate >30/min, SpO2 <94% (at room air), PaO2/FiO2 <300 mmHg or lung infiltrates >50%.[4] As per the NIH guideline, the severe patients are to be given supplemental oxygen.[4] So, for the purpose of our study, the population requiring supplemental oxygen was considered as “severe” category. Again, the patient not requiring supplemental oxygen was considered under mild-to-moderate category.

Critical illness

Patients with organ failure or septic shock.[4]

For our study purpose, we have combined the mild to moderate category together and the severe to critical category together.

Database search

A comprehensive search of 11 medical literature databases were done (PubMed, Cinahl Plus, Scopus, Embase, Ovid, Web of Science, Science Direct, Wiley Online Library, MedRxiv, BioRxiv, CNKI, and Cochrane CENTRAL) was performed from inception to August 8, 2020, without any language restriction. Unpublished studies from the preprint servers (MedRxiv, BioRxiv, and SSRN) and clinical trial registries (clinicaltrials.gov and WHO ICTRP) were also reviewed. Apart from these the references of the included studies were also screened for possible inclusion. The search was conducted using the keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV2, steroid, corticosteroids, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, betamethasone, and dexamethasone.

Screening of articles

After searching the databases with appropriate keywords, duplicates were removed and two reviewers (PS and HK) screened the studies using the title and abstract as predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full texts of relevant studies were further evaluated for possible inclusion in the metaanalysis using the same inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any discrepancy among investigators was resolved by consulting with BM and RK.

Data extraction

Two reviewers PS and AB independently extracted the data from the included articles using a pretested data-extraction form. For articles published in non-English language, translation was done using Google Scholar and relevant data was extracted. If the translation was not understandable, the study was excluded from the study.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality assessment of the clinical studies was performed using the “NOS.”[27] The quality was graded as good, fair, or poor based on the evaluation criteria. The RCTs were evaluated as per “Cochrane's risk of bias tool.”[28] As per the risk of bias analysis, articles were categorized to good, fair, and poor quality.[27,29] based on risk of bias analysis, only “high-quality studies” (good and fair quality) were included in the metaanalysis as per predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Statistical analysis

While estimating the point estimate, we used risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for dichotomous data, and mean difference with 95% CI was calculated in case of continuous data. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 and Chi-square statistics.[30] In case of presence of substantial heterogeneity (>50%) “random effect model” for analysis, otherwise, “fixed effect model” was used.[30] RevMan5.3 software was used for meta-analysis.[31] Data conversion to different formats were done as per Wan et al., 2014.[31]

Quality of evidence

GRADEpro[33] was used for generating the summary of findings (SOF) table with certainty of evidence for each outcome. “Certainty of evidence” was downgraded or upgraded as per the recommendations.[33] “Certainty of evidence” was represented as “high,” “moderate,” “low” or “very low.”

Result and Discussion

Included study details

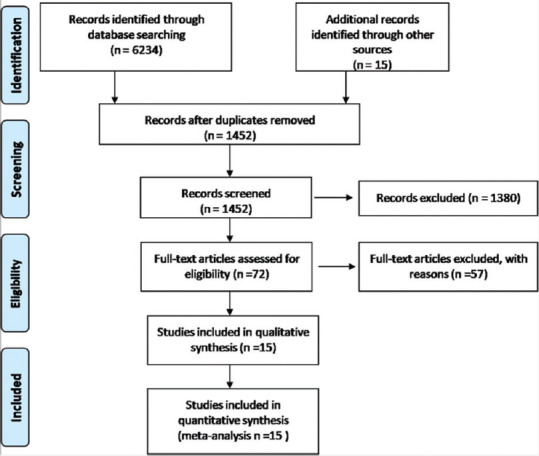

We searched 11 literature databases (PubMed, Cinahl Plus, Scopus, Embase, Ovid, Web of Science, Science Direct, Wiley Online Library, MedRxiv, BioRxiv, CNKI, and Cochrane CENTRAL) databases with appropriate keywords and finally, 1452 nonduplicate articles were screened with the help of title and abstract using predefined inclusion-exclusion criteria, among which 69 articles were further, screened using full text. A total of 15 studies (12 observational studies and 3 RCT) satisfied predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. Among these studies, 2 were preprint (Monreal E et al., 2020, Francesco Salton et al., 2020) [Table 1 and Figure 1]. A total of 57 studies were excluded after full-text screen.

Table 1.

Details of included studies

| Author, year/Country | Study design | Study population | Intervention | Control | Outcome | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al., 2020[34]/USA | Cohort study | Inclusion: RT-PCR + for COVID-19, requiring MV Exclusion: Patient expired <5 days after admission, patient receiving steroid other than MP |

MP was initiated within 14 days of admission, patients received >24 h MP, Dose: 1 mg/kg/day, ceiling dose 80 mg/day MP: n=48 (overall) MP: n=42 (in propensity matched cohort) Median time from hospitalization to MP initiation: 4 (2-6) days, Median dose: 80 (78.8-80) mg |

Propensity matched control, without steroid therapy C: n=69 (overall) C: n=42 (in propensity matched cohort) |

Ventilator-free days at day 28th, extubation, death, discharge from hospital day 28th and day 60th | To ensure baseline comparability in terms of severity, data from propensity score matched cohort was used in the analysis (there were 42 well matched pairs) |

| Keller et al., 2020[35]/USA | Observational study | All COVID-19 positive admitted patients, patients who died or discharged during 11th March to 13th April During the study period, some clinicians started prescribing steroids and some did not |

Patients prescribed steroid within 48 h of admission were considered as early CS group and analyzed n=140 | Patient never treated with CS n=1666 | Mortality, requirement of MV | Both the groups were comparable in terms of ferritin level, Charlson index, intubation rate, procalcitonin level |

| Horby et al., 2020[36]/UK | RCT | Clinically suspected or lab confirmed hospitalized COVID-19 patients | IV Dexamethasone (6 mg OD) for ten day or till discharge from hospital whichever earlier CS: n=2104 |

SOC: n=4321 | Mortality within 28 days, time until discharge from hospital, need of MV | Patients who required either IMV or supplemental oxygen at baseline were considered severe disease |

| Chopra et al., 2020[37] | Retrospective analysis | “Mechanically ventilated COVID-19” related ARDS patients admitted between 20th March to 17th April Decision of administering CS was at discretion of clinician, however, many prescribed routinely, many after excluding other infections and many didn’t use CS at all |

Patients who were administered steroid n=38 (Dexamethasone=36, MP=2) Dexamethasone Average Cumulative Dose=143 mg MP=120 mg Mean duration=9.2 days |

SOC n=23 |

“Ventilator free days” at day 28, “ICU free days” at day 30, “hospital free days” at day 30 | Both the groups were comparable in terms of Charlson score, ferritin level, CRP, pro-calcitonin and lactate level |

| Monreal et al., 2020[38]/Spain/preprint | Controlled observational comparative study | Adult, “lab confirmed COVID-19 patients” with ARDS, who are treated with CS Minimum equivalent dose of CS to be considered as CS treatment was ≥0.5 mg/kg MP equivalent dose for ≥2 days Patients treated with remdesivir were excluded |

High dose CS (≥250 mg/day of MP) n=177 |

Standard doses (≤1.5 mg/kg/day of MP n=396) | Mortality, need of MV | Both the groups were comparable at baseline in terms of “co-morbidities,” “time from symptom onset to hospitalization,” and “pattern of pneumonia at presentation,” “bacterial co-infection” |

| Salton et al., 2020[39]/Italy/pre-print | Multicentre observational study | COVID-19 positive, 18-80 years, PaO2/FiO2 <250 mm Hg, B/L infiltrate, CRP >100 ARDS as per Berlin criteria. n=173 (CS=83, NCS=90) | MP Loading dose=80 mg IV, maintenance dose=80 mg/day until achieving either a PaO2:FiO2 >350 mmHg or a CRP <20 mg/L |

CS unexposed concurrent patients | “ICU admission,” “need of IMV” or “all-cause death by day 28,” “MV free days by day 28” and “change in the level of CRP” | Both the groups were comparable in terms of baseline occurrence of co-morbidities, PaO2/FiO2, respiratory rate, CRP, LDH level |

| Jeronimo et al., 2020[40]/Brazil | Double blind RCT | Clinical AND/OR radiological suspicion of COVID-19 hospitalized patients AND/ OR ground glass opacity OR pulmonary consolidation on CT scan), age ≥18 years, with SpO2 ≤94% at room air OR in use of supplementary oxygen OR under IMV | IV sodium succinct MP (0.5 mg/kg), twice daily for 5 days n=194 |

Placebo (IV normal saline) n=199 |

28 days mortality, early mortality, IMV, oxygen index <100 by day 7 | As SpO2 ≤94% at room air OR in use of supplementary oxygen OR under IMV comes under severe disease in NIH, the study was considered under the “severe disease” population |

| Ooi et al., 2020[41]/Singapore/Preprint | Retrospective cohort study | Adult, RT-PCR+, admitted, COVID-19 patients Patients requiring only supportive care or MV at baseline were excluded |

CS + SOC CS: Prednesolone 30 mg OD to 40 mg BD CS >3 days use considered in analysis n=35 |

SOC n=57 |

Death, clinical progression, mechanical ventilation | Stage 1 and 2 did not require supplemental oxygen were considered under mild to moderate category and stage 3 patients requiring supplemental oxygen were considered under severe category while analysis |

| Fadel et al., 2020[42]/USA/observational study | Multicentered Quasi experimental study | RT-PCR+, COVID-19 patient with B/L infiltrate (radiology), requiring supplemental oxygen in the form of nasal cannula, or MV | IV MP 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses for 3-7 days Total n in MP=81 |

Standard of care n=132 |

Survival, MV need, ARDS, shock, AKD, hospital stay | Both the groups were comparable in terms of baseline severity as measured by qSOFA, NEWS score, number of patients requiring ICU and mechanical ventilation at baseline |

| Awasthi et al., 2020[43]/USA/Cohort study | Observational study | Critically ill COVID-19 patients | Dexamethasone, prednisone, triamcinolone, MP, prednesolone betamethasone, hydrocortisone n=17 | Standard of care n=41 | ICU duration, plasma IL6 level pre- and post-CS treatment, survival | As all patients were critically ill, we can assume baseline comparability in terms of severity between the two groups |

| Li et al., 2020[44]/China | Observational study | Patient with marked radiological progression However they did not enrol patients on mechanical ventilation at baseline |

Early steroid group: 40-80 mg/day (0.75-1.5 mg/kg/day) of MP for 3 days tapered to 20 mg/d for <7 days duration n=47 |

Control group: Patient with no CS treatment or Cs given at late phase (rescue treatment) n=21 |

Requirement of IMV, safety, complications of CS therapy, viral clearance and blood glucose level | Considered severe category as population included are having extensive radiological Progression which falls into severe category of COVID-19 according to NIH guideline[4] |

| Wang et al., 2020[45]/China/Cohort study | Retrospective cohort | Severe COVID-19 patients Case definition meeting any one criteria according to NIH definition of severe COVID-19[4] n=46 CS=26 NCS=20 |

Received MP 1-2 mg/kg/day for a period of 5-7 days via IV injection in addition to SOC | SOC | Requirement of MV, death, length of ICU stay and length of hospital stay | Comparison: Steroid versus Standard of care Considered under severe category |

| Zha et al., 2020[46]/China/Observational study | Observational study | Severe COVID-19 patients as defined by occurrence of respiratory distress, O2 saturation ≤93%, artery O2 partial pressure/O2 concentration ≤300, rate of respiration ≥30 | 40 mg MP OD or BD per day n=11 |

SOC n=20 |

Recovered, death, viral clearance, duration of symptom, length of hospital stay, kidney injury, liver injury | No difference was observed between the two treatment groups in terms of age, sex, co-morbidity, cytokine levels, and ferritin level |

| Yuan et al., 2020[47]/China | Retrospective cohort study | RT-PCR+, nonsevere COVID-19 pneumonia patients | CS group MP maximum dose 52.2mg/day n=74 |

None CS n=58 |

Progression to severe disease, secondary infection, time for fever, hospital stay, duration of viral shredding after illness onset | Analysis was done on propensity score matched group data, which ensures baseline comparability among the groups |

| Corral et al., 2020[29]/Spain/RCT | Partially randomized, preference, open-lebel trial | Moderate to severe COVID-19 patients Three arm Preference arm, intervention or control arm If preference than preferred arm, otherwise randomized into intervention or control arm |

MP 40 mg IV every 12 h for 3 days than 20 mg every 12 h for 3 days n=34 |

Standard of care n=29 |

Death, ICU admission, requirement of noninvasive ventilation | Data collected only from the randomized two arms |

Severe COVID-19: For our study, case definition of severe case of COVID-19 is: meeting any criteria i.e., “(1) respiratory distress, respiratory rate per min ≥30; (2) oxygen saturation ≤93% in resting phase; (3) arterial blood oxygen partial pressure/oxygen concentration ≤300 mmHg.”[45] However, the NIH guideline considers SpO2 cutoff of<94%.[4] So, for our study, we have considered this SpO2 cut off as <94%. CS= Corticosteroid, MP=Methyl prednesolone, MV=Mechanical ventilation, IMV=Invasive MV, SOC=Standard of care, RCT=Randomized control trial, OR=Odd ratio, ARDS=Acute respiratory distress syndrome, AKD=Acute kidney disease, CRP=C-reactive protein, HFNC=High-flow nasal cannula, RT-PCR=Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, IV=Intravenous, ICU=Intensive care unit, CT=Computed tomography, B/L=Bilateral, NCS=No Corticosteroid, LDH=Lactate dehydrogenase, NIH=National institute of health

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart of included studies

Risk of bias of the included studies

Risks of bias among the included RCTs are showed in Supplementary Figure 1 (155.7KB, tif) . Risks of bias among the included comparative observational studies are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Supplement Table 1.

Risk of bias table of included cohort studies

| Author, year | Comparison | S | C | O | SQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelson et al., 2020[34] | CS versus propensity matched control | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Keller et al., 2020[35] | Comparison: Early CS versus no CS | **** | ** | *** | G |

| Chopra et al., 2020[37] | Compared CS versus standard of care | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Monreal et al., 2020[38] Preprint | High dose CS versus standard care | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Salton et al., 2020[39] Pre-print | CS versus no CS | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Ooi et al., 2020[41] Priprint | Standard care without CS versus standard + adjunctive CS) | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Fadel et al., 2020[42] | Early CS versus standard of care | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Awasthi et al., 2020[43] | CS versus standard of care | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Li et al., 2020[44] | Early CS versus control | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Wang et al., 2020[45] | CS versus Standard of care | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Zha et al., 2020[46] | CS versus no CS | *** | ** | *** | G |

| Yuan et al., 2020[47] | CS versus no CS group | *** | ** | *** | G |

Studies were categorized to good, fair and poor quality as previously described.[29] Is the studies were found to have selection domain: 3/4 stars, 1/2 stars in comparability and 2/3 stars in outcome domain, they were categorized as good quality. If 2 star in selection domain, 1/2 stars in comparability and 2/3 stars in outcome domain, the studies were categorized of fair quality and if 0/1 star in either selection and outcome domain or 0 stars in comparability domain, than the studies were categorized as poor quality study. Risk of bias analysis of three included RCTs namely Horby et al., 2020,[36] Corral et al., 2020[48] and Jeronimo et al., 2020[40] has been given in Supplementary Figure 1. C=Comparability, S=Selection, O=Outcome, SQ=Study quality, G=Good

Details of included study populations across different severity categories

Details of the population included in the generation of data in the mechanically ventilated population

Among all the included studies, only three studies[34,37] provided data regarding the comparative efficacy of steroid + SOC vs. SOC in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. Horby et al., 2020[36] provided separate mortality data in the population requiring invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization.

Details of the population included in the generation of data in the severe to critical population

A total of 10 studies reported findings in severe to critical patients. Li et al., 2020 included patients which are at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) as indicated by “marked radiographic progression” as defined by “rapid progression of pneumonia” with “size increasing by >50% with the involvement of 1/3rd of lung fields within 48 h” or the “presence of ground-glass opacities involving more than half of the lung fields.”[44] As there was marked radiographic progression, this population included in the study was considered under the severe category. The study by Jeronimo et al. included a patient population with SpO2 ≤94%, or requiring supplementary oxygen or IMV. These patient population were considered under severe category.[40] Few studies used a pre and well-defined severe to critical population.[34,37,39,43,45] In the study by Horby et al., 2020, patients requiring supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation were considered under the severe to critical category.[36] In the study by Ooi et al., 2020, stage 3 patients requiring supplemental oxygen were considered under severe category.[41] In the study by Fadel et al's., 2020 included a population which either required supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation, so the study population were considered under severe to critical category.[42] Monreal et al., 2020 recruited COVID-19 patients who developed ARDS. So the population was considered under severe to critical category.[38] Nelson et al., 2020[34] and Chopra et al., 2020[37] included the COVID-19 population under mechanical ventilation. So, the population was considered under severe to critical category.

Details of the population included in the generation of data in mild to moderate population

In the study by Ooi Say Tat et al., 2020[41] patients were divided into 3 categories on the basis of severity: stage 1, stage 2, and stage 3. Stage 3 patients requiring supplemental oxygen were considered under severe disease, while stage 1 and 2 not requiring supplemental oxygen were considered under mild to moderate category. In the study by Horby et al., 2020,[36] patients not requiring supplemental oxygen at randomization were considered under mild to moderate category. Zha et al., 2020 included the patient population which comprised typically of mild disease at enrolment.[46] Yuan et al., 2020 included a nonsevere COVID-19 population.[47]

The study population in the GLUCOCOVID trial[49] comprised of both moderate and severe disease population. However, we could not find specific separate data regarding moderate group and severe group. Hence, data from this trial is not included in the analysis while dealing with the generation of data in the mild to moderate population.

Patients on mechanical ventilation

Efficacy of steroid on mortality in patients on mechanical ventilation

Two studies have reported comparative “mortality” data in patients on steroid + SOC versus SOC alone in patients on mechanical ventilation. Although a single study by Horby et al., 2020[36] reported the benefit of dexamethasone among patients who were on “invasive mechanical ventilation” at randomization, however, in mechanically ventilated patients, the use of methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day was not associated with significant improvement.[34] As the I2 value for subgroup difference was 88.9%, the results of both the studies were not combined. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 2 (782.2KB, tif) .

Severe to critical patients combined

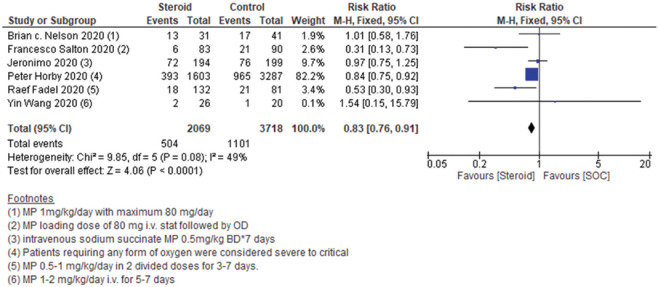

Severe to critical patients: Mortality

Among the included studies, six studies reported comparative mortality among patients on steroid + SOC versus SOC alone among severe to critical COVID-19 patients. A significant beneficial effect was seen while combining the results of all the six studies (RR0.83, 95% CI 0.76–0.91). As the heterogeneity was of moderate grade (I2 = 49%), we used a fixed-effect model to analyze the results. Data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Severe to critical: Steroid + standard of care vs. standard of care: Mortality

Among the included studies, the study by Francesco Shelton 2020 was a preprint. Hence, we did a sensitivity analysis by eliminating this study from the final analysis. Eliminating the preprint from final data analysis also did not change the final conclusion on mortality. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 3 (737.8KB, tif) .

However, while observing the results closely, we found that the beneficial effect was seen owing to a single study by Horby et al., 2020 (used dexamethasone, weight = 82.2%), and the other studies using methylprednisolone contributed only 17.8% to the final result. Hence, we did a sensitivity analysis based upon the steroid used. Although single study on dexamethasone showed significant benefit [Supplementary Figure 4a (899.9KB, tif) ], methylprednisolone use failed to show any significant benefit [Supplementary Figure 4b (899.9KB, tif) ]. As heterogeneity among the studies included in the methylprednisolone subgroup was higher (I2 = 60%), a “random effects model” was used for the analysis. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 4 (899.9KB, tif) .

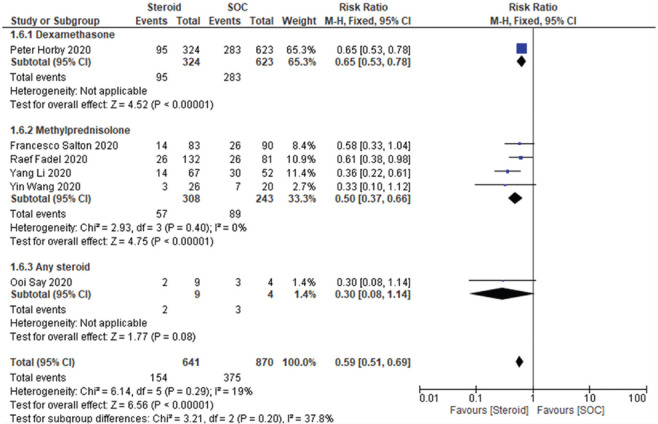

Severe to critical patients: Requirement of mechanical ventilation

Steroid + SOC arm showed significant benefit in terms of reducing the “requirement of mechanical ventilation” compared to the SOC arm (RR 0.59, [95% CI 0.51–0.69], I2 = 19%, fixed effect model used). At individual steroid level, both dexamethasone and methylprednisolone use was associated with a significant reduction in the requirement of mechanical ventilation among severe COVID-19 patients. Data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Severe to critical patients: Requirement of mechanical ventilation

However, among the included studies, the study by Francesco Shelton 2020 was a preprint. So, we did a sensitivity analysis by eliminating this study from the final analysis. However, eliminating the preprint from the final data analysis also did not change the final conclusion on the requirement of mechanical ventilation among severe to critical patients. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 5 (1.1MB, tif) .

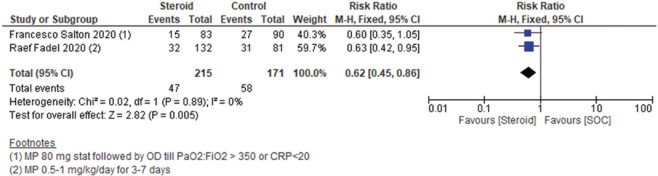

Severe to critical patients: Requirement of intensive care unit

Among severe COVID-19 patients, steroid treatment was associated with a significant decrease in the requirement of ICU (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.45–0.86, I2 = 0%, fixed effect model) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Severe to critical patients: Requirement of intensive care unit (ICU)

However, among the included studies, the study by Francesco Shelton 2020 was a preprint. So, we did a sensitivity analysis by eliminating this study from the final analysis. However, eliminating the preprint from the final data analysis also did not change the final conclusion on the requirement of ICU among severe to critical patients. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 6 (461.7KB, tif) .

Severe patients: Duration of hospital stay

Among the included studies, a total of three studies reported “duration of hospital stay”. Among the three studies, two studies (Raef Fadel, 2020 and Yin Wang et al., 2020) reported a shorter duration of hospital stay among steroid + SOC patients compared to the S. O. C. alone. However, the study by Jeronimo et al., 2020 did not find any benefit in terms of hospital stay among patients with severe to critical COVID-19. As the heterogeneity among the studies were quite high, we did not combine the results of the studies.

Time to virologic cure

A single study by Francesco Salton 2020 reported time to virologic cure among patients treated with steroid + SOC vs. SOC alone in severe to critical COVID-19 patients. However, “no difference” was found between the two arms in terms of time to virologic cure. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 7 (338.1KB, tif) .

Severe patients: Length of intensive care unit stay

Among the included studies, a single study by Wang et al., 2020 reported significantly lower length of ICU stay in severe COVID-19 patients in the steroid + SOC arm compared to the SOC arm alone.[45]

Severe patients: Duration of mechanical ventilation

Among the included studies, two studies evaluated the duration of mechanical ventilation in severe to critical COVID-19 patients. Although both the studies[39,42] showed a decreased “duration of mechanical ventilation” in the steroid + SOC arm, however, while combining the results, although the direction of effect was in the same side, however, heterogeneity was very high (I2 = 93%). So, we did not combine the results of the two studies.

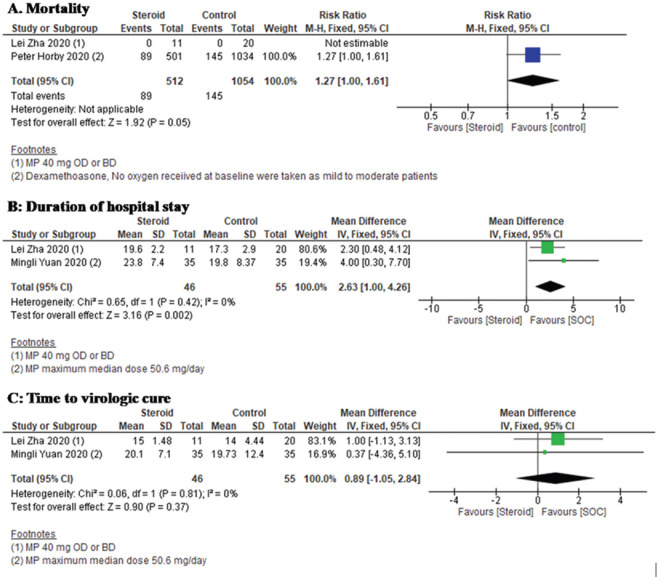

Mild to moderate patients (mild to moderate disease at initiation of study)

Mortality

Two studies[36,46] reported mortality among patients treated with steroid + SOC compared to SOC alone. However, in mild to moderate patients, no significant difference in mortality was seen between the two arms. Data showed in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

Efficacy and safety of steroid therapy in mild to moderate COVID-19, a: Forest plot showing comparative mortality among patients treated with steroid + SOC compared to SOC alone. b: Forest plot showing comparative duration of hospital stay among patients on steroid + SOC vs. SOC in mild to moderate patients. c: Forest plot showing comparative time to virological cure among patients on steroid + SOC vs. SOC in mild to moderate patients

Requirement of mechanical ventilation

A single study by Ooi Say Tat et al., 2020[41] reported the requirement of mechanical ventilation among patients who were treated with steroids + SOC and were suffering from mild to moderate disease at the initiation of the study. However, “no significant difference” was seen between the two arms with regards to the requirement of mechanical ventilation [Supplementary Figure 8 (398KB, tif) ].

Duration of hospital stay

Among the included studies, two studies[46,47] have reported the duration of hospital stay among patients on steroid + SOC vs. SOC in mild to moderate patients. Compared to SOC alone, the SOC + steroid arm showed significantly higher duration of hospital stay (MD 2.63, [95% CI 1.00–4.26], I2 = 0%, fixed effect model). Data are shown in Figure 5b.

Mild to moderate: Time to virologic cure

Among the included studies, two studies[46,47] have reported time to virologic cure among patients on steroid + SOC vs. SOC in mild to moderate patients. “No difference” was seen between the SOC alone arm and the SOC + steroid arm in “time to virological cure” (MD 0.89, [95% CI − 1.05–2.84], I2 = 0%, fixed effect model). Data showed in Figure 5c.

Duration of fever

A single study by Yuan et al., 2020[47] reported steroid + SOC versus SOC alone. However, no difference was found between both arms. Data are shown in Supplementary Figure 9 (355.5KB, tif) .

Efficacy of steroids in patients at risk of progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome

A single study by Li et al., 2020[44] evaluated the “safety and efficacy” of COVID-19 in patients with risk of progression to ARDS (as evaluated by radiologic criteria). Compared to the control group, there was a “significantly lower “requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation in the early steroid group (33.3% in the control group vs. 10.6% in the early corticosteroid group. The authors typically identified a window period for optimal use of corticosteroid administration that is patients showing marked radiographic progression and LDH < 2*ULN.

High dose versus low dose steroids in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with COVID-19

In a controlled observational study, Monreal et al., 2020 evaluated high dose of methyl-prednisolone (250 mg/day) versus standard dose of methylprednisolone (≤1.5 mg/kg/day) in patients with COVID-19 associated ARDS.[38] Hospitalized COVID-19 patients with confirmed diagnosis developing ARDS were included. After adjusting for baseline characteristics, high dose of steroid use was associated with higher mortality and composite requirement of MV or death.[38]

Evaluation of the association between mortality and level of C-reactive protein in patients receiving steroid

A single study reported that treatment with glucocorticoids was associated with “higher risk of mortality” or mechanical ventilation in patients with CRP level <10 mg/dl (odds ratio 0.23, 0.08–0.7). No difference in was seen in patients with CRP levels between 10 to <20 mg/dl. However, a protective effect was seen in terms of mortality when patients with CRP level of ≥20 mg/dl were treated with steroids.[50]

Sensitivity analysis

As in some of the cases of continuous data, we had to convert the median (interquartile range [IQR]) to mean ± standard deviation (SD), which was used in the meta-analysis. To overcome the possible effect of this conversion on treatment effect, we did a sensitivity analysis by removing these studies (severe to critical: time to virologic cure, mild to moderate: “duration of hospital stay,” “time to virological cure,” “duration of fever”). A sensitivity analysis was planned in case there were two or more than two studies on that endpoint.

Severe to critical

Time to virological cure: Single study: Data provided in mean ± SD.[39]

Mild to moderate

Duration of hospital stay: Two studies,[46,47] both studies represented data as median (IQR). So data converted to mean ± SD as previously described.[32]

Time to virological cure: Two studies,[46,47] both studies represented data as median (IQR). So data converted to mean ± SD as previously described.[32]

Duration of fever: Single study,[47] data provided in median (IQR). So data converted to mean ± SD as previously described.[32]

However, sensitivity analysis on the basis of the above was not possible as none of the endpoints had data which is a combination of mean ± SD and derived mean ± SD.

Grade: Summary of findings table

SOF table is shown in Table 2. Overall certainty of evidence ranged from moderate (in case of severe to critical: mortality) to low certainty for the other outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of findings

| Steroid compared to no steroid: All patients for COVID-19 Date August 3, 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or population: COVID-19 Date August 3, 2020 | ||||||

| Setting: | ||||||

| Intervention: Steroid | ||||||

| Comparison: No steroid: All patients | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (grade) | Comments | |

| Risk with no steroid: All patients | Risk with steroid | |||||

| Severe and critical: Mortality | 296 per 1000 | 246 per 1000 (225-269) | RR 0.83 (0.76-0.91) | 5787 (6 observational studies) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderatea,b | |

| Severe and critical: Requirement of MV | 431 per 1000 | 254 per 1000 (220-297) | RR 0.59 (0.51-0.69) | 1511 (6 observational studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa | |

| Severe and critical: Requirement of ICU | 339 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (153292) | RR 0.62 (0.450.86) | 386 (2 observational studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | |

| Mild and moderate: Mortality | 138 per 1000 | 175 per 1000 (138-221) | RR 1.27 (1.00-1.61) | 1566 (2 observational studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | |

| Mild and moderate: Duration of hospital stay | The mean mild and moderat: Duration of hospital stay was 0 | MD 2.63 higher (1 higher to 4.26 higher) | - | 101 (2 observational studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | |

| Mild and moderate: Time to virological cure | The mean mild and moderate: time to virological cure was 0 | MD 0.89 higher (1.05 lower to 2.84 higher) | - | 101 (2 observational studies) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | |

aRisk of Bias: As the studies included is mix of randomized and nonrandomized studies. RCT with high risk of bias at the level of allocation a concealment and blinding and low risk of bias with nonrandomized studies with certain limitations. We have downgraded at serious level considering these factors, bImprecision: The upper limit of the 95% CI is 0.76-0.91. The minimum expected risk reduction in mortality is 9%. We have not downgraded considering the fast spread of this condition. Grade working group grades of evidence. High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect, Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different, Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect, Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI=Confidence interval, RR=Risk ratio, MD=Mean difference, RCT=Randomized controlled trial

Discussion

Patients on mechanical ventilation

In this study, in patients with invasive mechanical ventilation, treatment with dexamethasone resulted in significant protection from mortality (single study). However, treatment with low to moderate dose methylprednisolone was associated with a significant increase in mortality (single study). However, as the number of studies is pretty less, a definite conclusion is not possible in this category of patients at this point. We need more well-conducted clinical trials to address this issue in this population.

Severe and critical patients

In our study, among severe to critical category patients, overall steroid use was associated with a decrease in mortality. However, a single study (Horby P et al., 2020) contributed the maximum to these results (weight 82.2%). On further sub-group analysis, dexamethasone was found to be useful (single study, Horby P et al., 2020), however, low to moderate dose prednisolone failed to prove its protective effect in terms of mortality. As almost all the studies included both severe and critical category patients in their analysis, a separate sub-group analysis of severe and critical category patients separately were not possible.

In a recent prospective metaanalysis by Jonathan A et al., 2020[25] similar lower 28 day mortality was seen among critically ill COVID-19 patients treated with steroids, highlighting the validity of the finding of our study. Again, similar to our study, no benefit was seen with hydrocortisone (3 studies) and methylprednisolone (1 study). Another important point to be observed in the meta-analysis is that for the 28-day mortality endpoint, the recovery group study had a weight of 57%, highlighting the contribution of that single study to the overall result, which is similar to our study.[25]

Regarding other endpoints, in our study, steroid administration was also associated with significant protection against the requirement of mechanical ventilation. In subgroup analysis, the benefit was observed both in the case of dexamethasone and methylprednisolone. Steroid administration was also associated with “less requirement of ICU” (2 studies), “lower length of ICU stay” (1 study), “lower duration of mechanical ventilation” (2 studies). However conflicting result was observed in the case of the duration of hospital stay and no difference was observed in terms of “time to virological cure” (1 study).

Mild to moderate patients

In mild to moderate patients with COVID-19, “no benefit was observed” with steroid administration in terms of mortality (2 studies), the requirement of mechanical ventilation (1 study), time to virologic cure (2 studies), and duration of fever (1 study), however, steroid administration was associated with a significant increase in the duration of hospital stay (2 studies).

Patients at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome

A single study[44] reported the possible benefit of steroid administration in patients with at risk of ARDS. The authors typically chosen a window period where radiological progression was there, but the LDH level was <2 times of upper limit of normal. Steroid administration lowered the risk of mechanical ventilation compared to SOC alone.

C-reactive protein level and efficacy of steroids

To determine the optimal patient category, who can be the optimal beneficiary of steroid treatment,[50] COVID-19 patients were categorized into three different categories on the basis of CRP level (CRP <10, 10–20 and >20 mg/dl. In patients with CRP <10 mg/dl, steroid treatment was associated with a higher requirement of mechanical ventilation or mortality, on the other hand, the protective effect of steroids became evident in the CRP >20 mg/dl group. However, these are findings from a single study. We need more studies to validate these findings.

Methyl prednesolone dose and efficacy

In the meta-analysis, most of the included studies used methylprednisolone dose up to 2 mg/kg/day. Although some of the observational studies claim[38] that there is more mortality with pulse steroid therapy, compared to control, however, there was preferential allocation of severe patients to the pulse steroid arm.

Efficacy of corticosteroids is reported in “COVID-119 patients with ARDS,”[51] where all the cases (n = 7) improved with high dose corticosteroid therapy (Methyl Prednesolone [MP] 500–1000 mg/day*3 days followed by 1 mg/kg then tapered off). Another study reported three cases of tocilizumab-resistant COVID-19 pneumonia which responded to pulse methylprednisolone therapy and i.v. immunoglobulin.[52] Mareev Yu U et al. also reported that a rapid anti-inflammatory effect was seen with pulse corticosteroid, however as the article was in another language and the translate was not understandable, it was not included in the analysis.[53]

Effect of steroid treatment on duration of viral shredding

Few studies have evaluated the effect of steroids on the duration of viral shredding. Li et al., 2020[54] found that the use of high dose (MP 80 mg/day or equivalent) steroid was associated with prolonged viral clearance compared to the lower dose (40 mg/day). However, they did not give the details of the patients on steroids and those without steroids, comparability of severity, and other comorbid details are not given in detail, so a detailed evaluation was not possible for possible confounders and how they were taken care of. In another study by Hu et al.,[55] in addition to other factors, corticosteroid use (equivalent dose ≥20 mg of MP/day) was associated with a prolongation of viral clearance, however, in univariate analysis, severity of illness is also associated with prolongation of viral clearance highlighting the importance of adjusting the severity of disease while commenting on this important parameter. Similarly, Li et al.,[56] also found the occurrence of fever >38.5°C, treatment with corticosteroids and a longer gap between disease onset and time to hospitalization were found to be associated with prolonged viral shedding in COVID-19 patients. Xu et al., 2020[57] found that a longer gap between disease onset and time to hospitalization, male gender, and requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation was associated with prolongation of viral shredding. Ni et al., 2020[58] did not find any significant effect of low dose glucocorticoid on virus clearance. In our study, among the included studies, no significant difference was observed in terms of viral clearance in both severe to critical patients and mild to moderate patients. However, another point to be noted is that the maximum dose of steroids used among the included studies ranged from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/day MP or equivalent.

Other safety considerations

It is to be noted that steroid use has its own safety considerations and complications, for example, hyperglycemia, infection. However, the trials provided limited information on the safety profile of corticosteroids and most of the trials did not report the safety considerations.[59] Hence, similar to its use in other conditions, standard safety considerations should always be considered while using corticosteroids, especially among patients with other co-morbidities, for example, diabetes.[60] Control of diabetes and sepsis screen may serve as an essential prerequisite for corticosteroid therapy, but the recommendations vary in case by case basis. Prescreening and control of blood sugar control in case of diabetes, pro-calcitonin level for sepsis, etc., and other standard recommendations may help in this regard.

Limitation

Most of the studies included a mixed population at the initiation of the study. Hence, we have less studies which specifically addressed special category of patients e.g., mild to moderate, severe, and critical category

Again, in most of the studies, more severe patients were allocated into the steroid arm, causing a baseline imbalance. To tackle this issue, we kept the inclusion-exclusion criteria tight to avoid baseline imbalance, especially in terms of severity. We included only those studies where both the arms were comparable in terms of baseline characteristics especially severity

Although few studies are there evaluating the safety of pulse steroids, more severe patients were in the steroid group and thus did not fulfil our predefined inclusion-exclusion criteria.

Summary and Conclusion

Among mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients, dexamethasone may provide mortality benefits; however, we need more studies to address the same. Among severe to critical patients, corticosteroid administration was associated with “reduced mortality,” “reduced requirement of mechanical ventilation,” “reduced requirement of ICU” and “reduced duration of mechanical ventilation.” Among mild to moderate patients, higher duration of hospitalization was observed in the steroid arm, while in other domains like mortality, the requirement of MV, the requirement of ICU, duration of fever, no difference was seen between the steroid treatment arm and SOC arm. In a single study, steroid treatment reduced the requirement of mechanical ventilation in patients at risk of progression to ARDS. However, these findings need to be validated in bigger sized studies.

Highlight

In this metaanalysis, we evaluated the “safety” and “efficacy” of steroid-therapy in COVID-19 population and across different categories of severity

Among mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients, dexamethasone may provide mortality benefit; however, we need more studies to address the same

Among severe to critical patients, corticosteroid administration was associated with “reduced mortality,” reduced “requirement of mechanical ventilation,” reduced “requirement of ICU” and reduced “duration of mechanical ventilation”

Among mild to moderate patients, only a significant higher duration of hospitalization was observed in the steroid arm, while in other areas like mortality, requirement of MV, requirement of intensive care unit, duration of fever, “no difference” was seen between the steroid treatment arm and standard of care (SOC) arm

In properly selected patient population (based-upon clinical severity and biomarker status), steroid administration may prove beneficial in patients with COVID-19.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias among the included RCTs

Effect of steroid treatment on mortality in patients on mechanical ventilation

Sensitivity analysis: severe and critical: Mortality

Subgroup analysis on the basis of type of steroid use: Steroid + SOC vs. SOC in severe to critical patients: Mortality

Sensitivity analysis (preprint): requirement of mechanical ventilation

Sensitivity analysis (preprint) Severe to critical patients: Requirement of ICU

Severe to critical patients: Time to virologic cure

Mild to moderate disease: Steroid vs. SOC: requirement of mechanical ventilation

Mild to moderate disease: Steroid vs. SOC: duration of fever

References

- 1.Prajapat M, Sarma P, Shekhar N, Avti P, Sinha S, Kaur H, et al. Drug targets for corona virus: A systematic review. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52:56–65. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_115_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prajapat M, Shekhar N, Sarma P, Avti P, Singh S, Kaur H, et al. Virtual screening and molecular dynamics study of approved drugs as inhibitors of spike protein S1 domain and ACE2 interaction in SARS-CoV-2. J Mol Graph Model. 2020;101:107716. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2020.107716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prajapat M, Sarma P, Shekhar N, Prakash A, Avti P, Bhattacharyya A, et al. Update on the target structures of SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52:142–9. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_338_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 21]. Available from: https://files.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/guidelines/covid19treatmentguidelines.pdf .

- 5.Yam LY, Lau AC, Lai FY, Shung E, Chan J, Wong V, et al. Corticosteroid treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2007;54:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson MR, Kaminski JJ, Kurt-Jones EA, Fitzgerald KA. Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection. Viruses. 2011;3:920–40. doi: 10.3390/v3060920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varthya SB, Sarma P, Bhatia A, Shekhar N, Prajapat M, Kaur H, et al. Efficacy of green tea, its polyphenols and nanoformulation in experimental colitis and the role of non-canonical and canonical nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-kB) pathway: a preclinical in-vivo and in-silico exploratory study? J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1785946. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1785946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha P, Matthay MA, Calfee CS. Is a “Cytokine Storm” Relevant to COVID-19? JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1152–4. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma P, Kaur H, Kumar H, Mahendru D, Avti P, Bhattacharyya A, et al. Virological and clinical cure in COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:776–85. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahalmani VM, Mahendru D, Semwal A, Kaur S, Kaur H, Sarma P, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: A review based on current evidence. Indian J Pharmacol. 2020;52:117–29. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_310_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarma P, Kaur H, Medhi B, Bhattacharyya A. Possible prophylactic or preventive role of topical povidone iodine during accidental ocular exposure to 2019-nCoV. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarma P, Kaur H, Medhi B, Bhattacharyya A. Letter to the editor: Possible role of topical povidone iodine in case of accidental ocular exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258:2575–8. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alijotas-Reig J, Esteve-Valverde E, Belizna C, Selva-O'Callaghan A, Pardos-Gea J, Quintana A, et al. Immunomodulatory therapy for the management of severe COVID-19. Beyond the anti-viral therapy: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102569. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. SARS: Systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui DS. Systemic corticosteroid therapy may delay viral clearance in patients with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:700–1. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2371ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Chen C, Hu F, Wang J, Zhao Q, Gale RP, et al. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on outcomes of persons with SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, or MERS-CoV infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2020;34:1503–11. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grifoni A, Sidney J, Zhang Y, Scheuermann RH, Peters B, Sette A. A sequence homology and bioinformatic approach can predict candidate targets for immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:671–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veronese N, Demurtas J, Yang L, Tonelli R, Barbagallo M, Lopalco P, et al. Use of corticosteroids in coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia: A systematic review of the literature. Front Med. 2020;7:170. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gangopadhyay KK, Mukherjee JJ, Sinha B, Ghosal S. The role of corticosteroids in the management of critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020 2020.04.17.20069773. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhao Q, Liu J. The effect of corticosteroid treatment on patients with coronavirus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu S, Zhou Q, Huang L, Shi Q, Zhao S, Wang Z, et al. Effectiveness and safety of glucocorticoids to treat COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:627. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Group TWREA for C-19 T (REACT) W. Sterne JA, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically Ill patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suran. Pulse Therapy – A Newer Approach. [Last accessed on 2020 Sep 04]. Available from: http://www.ijmdent.com/article.asp?issn=2229-6360;year=2017;volume=7;issue=1;spage=41;epage=44;aulast=Suran .

- 27.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

- 28.Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. [Last assessed on 2021 Feb 16]. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- 29.Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies [Internet] [Assessed on 11 Feb 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115843/bin/appe-fm3.pdf .

- 30.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 07]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/cochranehandbook-systematic-reviews-interventions .

- 31.RevMan 5 Download. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 29]. Available from : http://online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/revman-5-download .

- 32.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.GRADEpro. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://gradepro.org/

- 34.Nelson BC, Laracy J, Shoucri S, Dietz D, Zucker J, Patel N, et al. Clinical Outcomes Associated with Methylprednisolone in Mechanically Ventilated Patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1163. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1163. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1163. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keller MJ, Kitsis EA, Arora S, Chen JT, Agarwal S, Ross MJ, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on mortality or mechanical ventilation in patients with COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:489–93. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report? N Engl J Med. 2020:NEJMoa2021436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chopra A, Chieng HC, Austin A, Tiwari A, Mehta S, Nautiyal A, et al. Corticosteroid administration is associated with improved outcome in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0143. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monreal E, Sainz de la Maza S, Natera-Villalba E, Beltrán-Corbellini Á, Rodríguez-Jorge F, Fernández-Velasco JI, et al. High versus standard doses of corticosteroids in severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-020-04078-1 . cited 2021 Feb 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Salton F, Confalonieri P, Santus P, Harari S, Scala R, Lanini S, et al. Prolonged low-dose methylprednisolone in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa421. 2020.06.17.20134031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeronimo CMP, Farias MEL, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, Alexandre MAA, Melo GC, et al. Methylprednisolone as Adjunctive Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 (Metcovid): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase IIb, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug;12:ciaa1177. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ooi ST, Parthasarathy P, Lin Y, Nallakaruppan V, Ng S, Tan TC, et al. Adjunctive Corticosteroids for COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa486. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadel R, Morrison AR, Vahia A, Smith ZR, Chaudhry Z, Bhargava P, et al. Early short-course corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awasthi S, Wagner T, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Puranik A, Hurchik M, Agarwal V, et al. Plasma IL-6 Levels following Corticosteroid Therapy as an Indicator of ICU Length of Stay in Critically ill COVID-19 Patients. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00429-9. 2020.07.02.20144733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y, Zhou X, Li T, Chan S, Yu Y, Ai JW, et al. Corticosteroid prevents COVID-19 progression within its therapeutic window: A multicentre, proof-of-concept, observational study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1869–77. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1807885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, Wang C, Wang B, Zhou P, et al. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:57. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zha L, Li S, Pan L, Tefsen B, Li Y, French N, et al. Corticosteroid treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Med J Aust. 2020;212:416–20. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan M, Xu X, Xia D, Tao Z, Yin W, Tan W, et al. Effects of corticosteroid treatment for non-severe COVID-19 pneumonia: A propensity score-based analysis. Shock. 2020;54:638–43. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corral L, Bahamonde A, Revillas FA delas, Gomez-Barquero J, Abadia-Otero J, Garcia-Ibarbia C, et al. GLUCOCOVID: A controlled trial of methylprednisolone in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. medRxiv. 2020 2020.06.17.20133579. [Google Scholar]

- 49.GLUCOCOVID: A Controlled Trial of Methylprednisolone in Adults Hospitalized with COVID-19 Pneumonia-Abstract-Europe PMC. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 24]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr177192 .

- 50.Keller MJ, Kitsis EA, Arora S, Chen JT, Agarwal S, Ross MJ, Tomer Y, Southern W. Effect of Systemic Glucocorticoids on Mortality or Mechanical Ventilation in Patients With COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:489–93. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.So C, Ro S, Murakami M, Imai R, Jinta T. High-dose, short-term corticosteroids for ARDS caused by COVID-19: A case series. Respirol Case Rep. 2020;8:e00596. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheianov MV, Udalov YD, Ochkin SS, Bashkov AN, Samoilov AS. Pulse therapy with corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin in the management of severe tocilizumab-resistant COVID-19: A report of three clinical cases. Cureus. 2020;12:e9038. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steroid Pulse -Therapy in Patients with Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19), sYstemic inFlammation and Risk of vEnous thRombosis and Thromboembolism (WAYFARER Study) | Request PDF. ResearchGate. [Last accessed on 2020 Sep 04]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343261137_Steroid_pulse_-therapy_in_patients_With_coronAvirus_Pneumonia_COVID-19_sYstemic_inFlammation_And_Risk_of_vEnous_thRombosis_and_thromboembolism_WAYFARER_Study . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Li S, Hu Z, Song X. High-dose but not low-dose corticosteroids potentially delay viral shedding of patients with COVID-19? Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa829. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa829. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu F, Yin G, Chen Y, Song J, Ye M, Liu J, et al. Corticosteroid, oseltamivir and delayed admission are independent risk factors for prolonged viral shedding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Respir J. 2020;14:1067–75. doi: 10.1111/crj.13243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li TZ, Cao ZH, Chen Y, Cai MT, Zhang LY, Xu H, et al. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding and factors associated with prolonged viral shedding in patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26280. 10.1002/jmv.26280. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26280. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu K, Chen Y, Yuan J, Yi P, Ding C, Wu W, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:799–806. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yi Ping, Ni Qin. Retrospective analysis of low dose glaucocorticoids on virus clearance in patients with new coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese journal of clinical infectious diseases. 2020:13. [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO. Corticosteroids for COVID-19. WHO; [Last accessed on 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-Corticosteroids-2020.1 . [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamez-Pérez HE, Quintanilla-Flores DL, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, González-González JG, Tamez-Peña AL. Steroid hyperglycemia: Prevalence, early detection and therapeutic recommendations: A narrative review. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1073–81. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i8.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Risk of bias among the included RCTs

Effect of steroid treatment on mortality in patients on mechanical ventilation

Sensitivity analysis: severe and critical: Mortality

Subgroup analysis on the basis of type of steroid use: Steroid + SOC vs. SOC in severe to critical patients: Mortality

Sensitivity analysis (preprint): requirement of mechanical ventilation

Sensitivity analysis (preprint) Severe to critical patients: Requirement of ICU

Severe to critical patients: Time to virologic cure

Mild to moderate disease: Steroid vs. SOC: requirement of mechanical ventilation

Mild to moderate disease: Steroid vs. SOC: duration of fever