Abstract

Molecular rotor-based fluorophores (RBFs) have been widely used in many fields. However, it remained enigmatic how to rationally control their viscosity sensitivity, thus limiting their application. Herein, we resolve this problem by chemically installing extended π-rich alternating carbon-carbon linkage between the rotational electron donor and acceptor of RBFs. Our data reveal that the length of π-rich linkage strongly influences the viscosity sensitivity, likely resulted from varying height of the energy barriers between the fluorescent planar and the dark twisted configurations. This mechanism allows for the design of three scaffolds of RBF derivatives that span a wide range of viscosity sensitivities. Application of these RBFs is demonstrated by a dual-color imaging strategy that can differentiate misfolded protein oligomers and insoluble aggregates both in test tubes and live cells. Beyond RBFs, we envision that this chemical mechanism might be generally applicable to a wide range of photoisomerizable and aggregation-induced emission fluorophores.

Keywords: molecular rotor-based fluorophores, viscosity sensitivity, protein aggregation, fluorescence microscopy

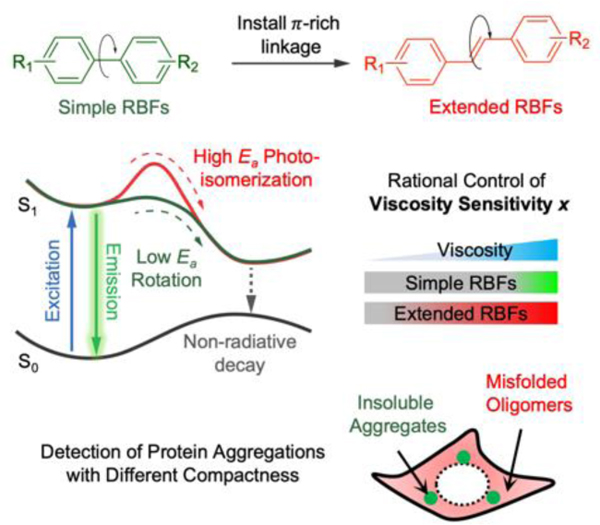

Graphical Abstract

In this work, we reported a novel method to rationally control the viscosity sensitivity of molecular rotor-based fluorophores (RBFs) by installing π-rich linkage between the electron donor and acceptor of RBFs. The outcome of this work generates RBFs that span a wide range of viscosity sensitivity and allow detection of protein aggregation with different compactness both in vitro and in live cells.

Introduction

Photoisomerizable fluorophores, molecular rotor-based fluorophores and aggregation-induced emission fluorophores are emerging classes of molecules that rotate along specific bonds at excited state[1]. This feature has enabled their broad applications in biological systems, membrane chemistry and material science[2]. In solvents wherein rotation between electron donor and acceptor is allowed, fluorophores undergo twisted conformations wherein intramolecular charge-transfer rapidly occurs at excited state to effectively quench fluorescent emission. When rotation is restricted, non-radiative decay is voided, resulting in significant fluorescence emission. As one major family of these fluorophores, molecular rotor-based fluorophores (RBFs) have been appreciably used as fluorogenic molecules in different fields, particularly as biosensors because of their ability to exhibit enhanced fluorescence signal in viscous environments[3]. Structurally, most RBFs possess an electron donor, electron acceptor and linkages to allow charge transfer. When RBFs are buried in viscous environments, inhibition of the low energy twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) state leads to enhanced fluorescence[4]. One of the most featuring properties of RBF is viscosity sensitivity, which defines RBF’s transition from bright to dark state that is linked to the viscosity-dependent conformational change of RBF. Despite extensive efforts to chemically regulate spectra and fluorescence quantum yields of these fluorophores[5], it remains a challenge how the viscosity sensitivity can be rationally controlled via chemical modifications on the wide range of fluorophores.

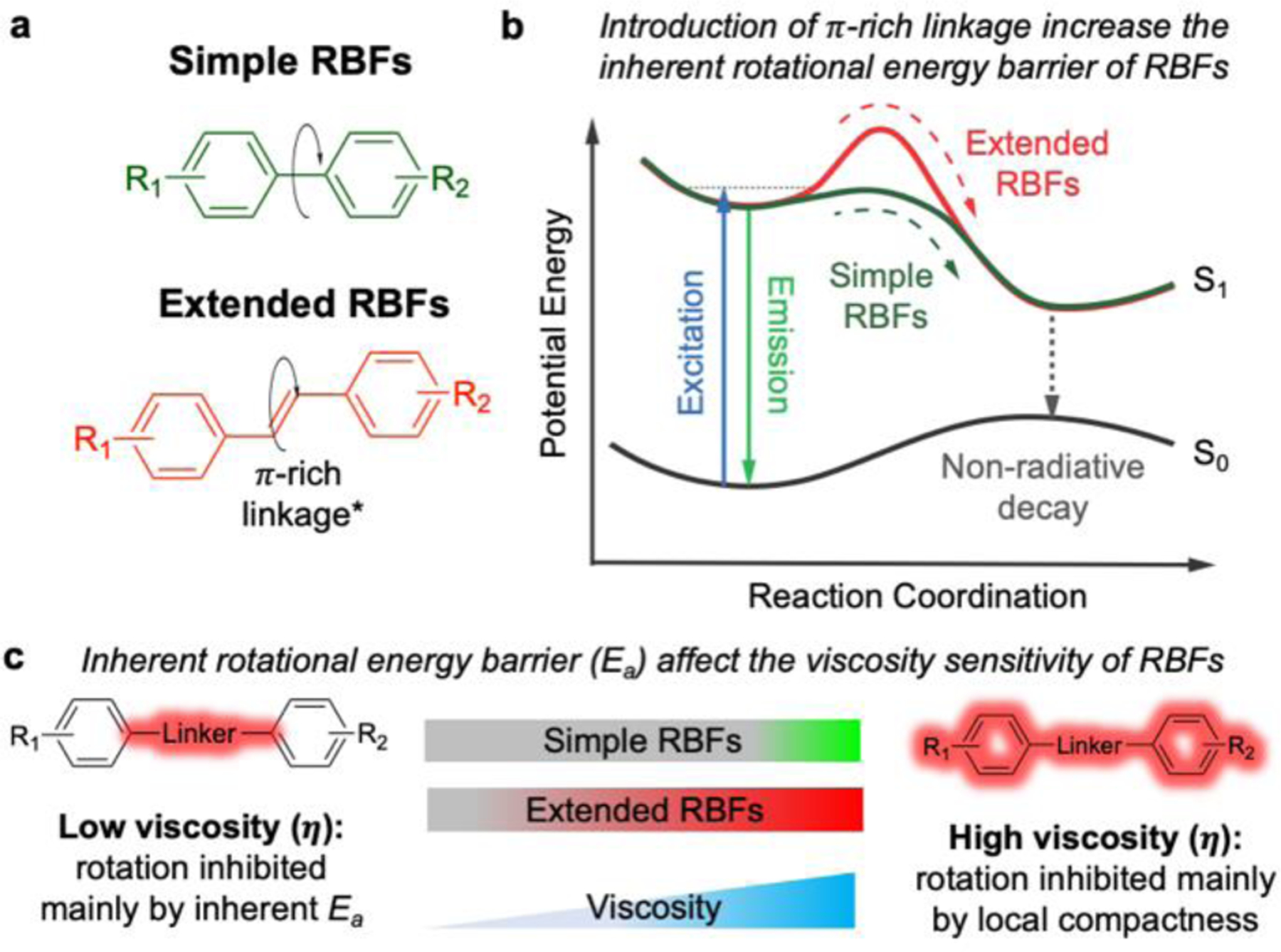

In this work, we demonstrate a new mechanism to control the excited state rotational barrier leading to the twisted conformation, thus controlling RBF’s emission in response to environmental viscosity as a rotational restriction. As an attempt to control the fluorogenic behavior of RBFs, we chose to modify the simplest fragment—linkage, by installing π-rich alternating bridges between the two rotational moieties (Figure 1a). As described by the Jablonski diagram[6] (Figure 1b), excited RBFs could either return to the ground state through fluorescence or through internal rotation which leads to a twisted, non-radiative configuration[7]. We hypothesize that the chemical modification of linkages could change the rotational energy barrier leading to the twisted dark state, therefore control the population of each energy dissipation pathway, hence tuning the fluorogenic behavior of RBFs.

Figure 1.

Installation of π-rich alternating linkages enhances the rotational energy barrier and changes the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs. (a) Comparison between commonly used simple RBFs with single bond rotational axis and extended RBFs possess π-rich alternating linkages. The π-rich linkages include both polyene and polymethine type. (b) The proposed Jablonski diagram showing the role of π-rich linkages to enhance the inherent rotational energy barrier (Ea) of RBFs. (c) Fluorescence of extended RBFs can be activated in lower a viscosity environment compared to simple RBF analogs, likely because the increased Ea restricts the rotation-induced non-radiative decay.

Traditionally, many RBFs often incorporate a single bond between electron donor and acceptor. In a non-viscous environment, rotations around this single bond will experience minimal resistance because of the low inherent rotational barrier. As a result, they are poorly fluorescent as the excited state energy is constantly dissipated through non-radiative TICT process. Only in a rigid environment (polymer films[8], protein aggregates[9], etc.), the internal rotation of simple RBFs would be restricted, leading to an enhanced fluorescence. Installing π-rich alternating bridge, on the other hand, forces excited RBFs to undergo trans-cis (E-Z) isomerization in order to adopt a twisted conformation[10]. Unlike single bond rotation, such E-Z isomerization was previously suggested to have a high energy barrier because the π-electrons along the alternating carbon-carbon bonds are largely equalized, making rotations along these bonds to be difficult[11]. As a result, compared to simple RBF analogs, extended RBFs could fluoresce in less viscous environments, in which the inherent rotational energy barrier plays the dominant role to restrict internal rotation. Through photophysical characterization, we demonstrated that the installation of short alternating π-rich bridges may act as a general modification to control the fluorogenic behavior of RBFs via enhanced energy barrier. Enabled by this method, RBFs with finely tuned fluorogenic properties were further used to detect protein aggregations with different compactness both in vitro and in live cells.

Results and Discussion

Introduction of extended π-rich alternating linkages reduces the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs

We started by incorporating varying linkers in three representative RBFs: benzothiazolium, 4-hydroxybenzylidene-imidazolinone (HBI) and 2-dicyanomethylene-3-cyano-2,5-dihydrofuran (DCDHF) (Figures 2a–2c; Figure S1–S4; Table 1). These linkers contain polymethine structures, thus enabling multiple modes of rotation and isomerization. Thioflavin-T (ThT), a benzothiazole-based fluorophore, has been extensively used as a fluorogenic probe to detect amyloid fibers[12]. Modification on the ThT was achieved by introducing a methine group between the electron-donating aminobenzene group and electron-withdrawing benzothiazolium ring, affording 1a, a stilbene type analog of ThT. Further extension of the methine bridge led to 1b. For HBI-based fluorophores, 2a and 2b were synthesized mimicking the chromophore core structure of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)[9a, 13], wherein the aminobenzene electron donor and imidazolinone electron acceptor were connected by one methine group for 2a and two methine groups for 2b. For the DCDHF-based fluorophores 3a, a single methine-based linker was used to connect the aminobenzene electron donor and DCDHF electron acceptor, resulting 3b. As shown by fluorescence spectroscopic measurements, all of these fluorophores emit stronger fluorescence in the viscous glycerol compared to non-viscous water and non-polar 1,4-dioxane (Figures S3–S5, Table S2), suggesting that the restriction of internal rotation accompanied by enhanced viscosity is the major cause for the fluorogenic response of these newly resolved fluorophores. Furthermore, we carried out the fluorescence lifetime measurement was carried out using a time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) experiment (Figure S6 and Table S3). Except for ThT and 2a, other fluorophores exhibited modestly elongated lifetime when viscosity of solvent increased from 30 to 1078 mPa•s, suggesting the inhibition of TICT in high viscosity.

Figure 2.

Viscosity sensitivity of RBFs is significantly and systematically affected by introduction of extended linkages. (a-c) Structure of a library of 7 RBFs from 3 scaffolds. (d-f) Fluorescence intensity of RBFs in a series of ethylene glycol/glycerol mixture with defined viscosities as shown in Table S1. (g-i) Viscosity sensitivity calculated based on the fluorescence intensity in ethylene glycol and glycerol mixture. (See Experimental Procedures in SI regarding the measures and calculations)

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of fluorophores measured in 100% glycerol.

| RBFs | λAbs (nm) | λEm (nm) | Stokes shift (nm) | ε (M−1cm−1) |

QY (ϕ) | Brightness (B = ε x ϕ) |

Viscosity sensitivity (x) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThT | 423 | 492 | 69 | 30,000 | 0.16 | 4,800 | 0.79 |

| 1a | 531 | 600 | 69 | 49,000 | 0.75 | 36,750 | 0.51 |

| 1b | 595 | 714 | 119 | 17,000 | 0.51 | 8,670 | 0.32 |

| 2a | 450 | 518 | 68 | 24,000 | 0.03 | 720 | 0.68 |

| 2b | 485 | 630 | 145 | 30,000 | 0.08 | 2,400 | 0.26 |

| 3a | 500 | 540 | 40 | 87,000 | 0.19 | 16,530 | 0.72 |

| 3b | 600 | 650 | 50 | 86,000 | 0.65 | 55,900 | 0.52 |

Next, we sought to evaluate the viscosity sensitivity of the newly synthesized RBFs. Viscosity sensitivity (x) is a quantitative measure for RBFs to describe the relationship between fluorescence intensity and viscosity[14]. Based on the Föster-Hoffmann equation (Eq 1),

| (1) |

the fluorescence intensity maxima (proportional to quantum yield Φ) were measured and plotted against the solvent viscosities in a double logarithmic scale to give a linear correlation, whose slope defines the value of x. The larger the x value is, the steeper fluorescence intensity changes as a function of viscosity. In this regard, we measured the fluorescence intensity of these RBFs in a series of binary mixtures of ethylene glycol and glycerol (EG/G) with known viscosities (Figures 2d–2e)[5b], and derived x values for each RBFs (Figures 2h–2i). Given that ethylene glycol and glycerol have similar polarity, the fluorescence intensity measured in EG/G mixtures should depend solely on solvent viscosity. For the benzothiazole scaffold, ThT exhibited a 4.7-fold increase of fluorescence intensity when viscosity changes from 81 to 621 mPa·s, followed by a 2.8-fold change for 1a and a 1.8-fold change for 1b. In agreement with the fluorescence intensity measures, ThT showed the highest x value, reaching 0.79. For 1a and 1b that incorporate extended linkages, their x values decreased with increasing number of double bonds in the linkages: 0.50 for 1a and 0.32 for 1b. The x values were also measured for the HBI and DCDHF scaffolds. In both cases, RBFs that bear extended linkages exhibited smaller x values (x = 0.68 for 2a, x = 0.26 for 2b; x = 0.72 for 3a, x = 0.52 for 3b). Additionally, we measured fluorescence quantum yields (Φ) in a series of methanol and glycerol mixture (Figure S7). As the viscosity decreased, the Φ values of RBFs with extended linkages declined less significantly than RBFs with a single bond linkage, further confirming the smaller x values for RBFs bearing extended linkages. Taken together, these results suggest the installation of π-rich alternating linkages could reduce the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs, therefore change their fluorogenic behaviors.

Extended linkages increase the excited state energy barrier for RBFs

Here, we attempted to understand the underlying mechanism that governs the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs with varying π-rich linkages. Most RBFs quench fluorescent emission through a rapid non-radiative TICT process[4b]. Consequently, restriction of internal rotation between a high-energy planar (or near planar) configuration and a low-energy twisted configuration in the excited state could determine the viscosity sensitivity for RBFs. Herein, we hypothesized that the introduction of π-rich linkage altered the rate of internal rotation (krot) between the planar and the twisted configuration of RBFs. According to the Arrhenius equation (Eq 2), krot can be quantified as a function of the rotational energy barrier Ea in comparison with thermal fluctuation kBT,

| (2) |

where A is a pre-exponential factor that is solely viscosity dependent. Given that all factors in the Arrhenius equation are identical except Ea when comparing simple and extended RBFs in the same solvent, the difference of their viscosity sensitivity is ultimately coming from Ea.

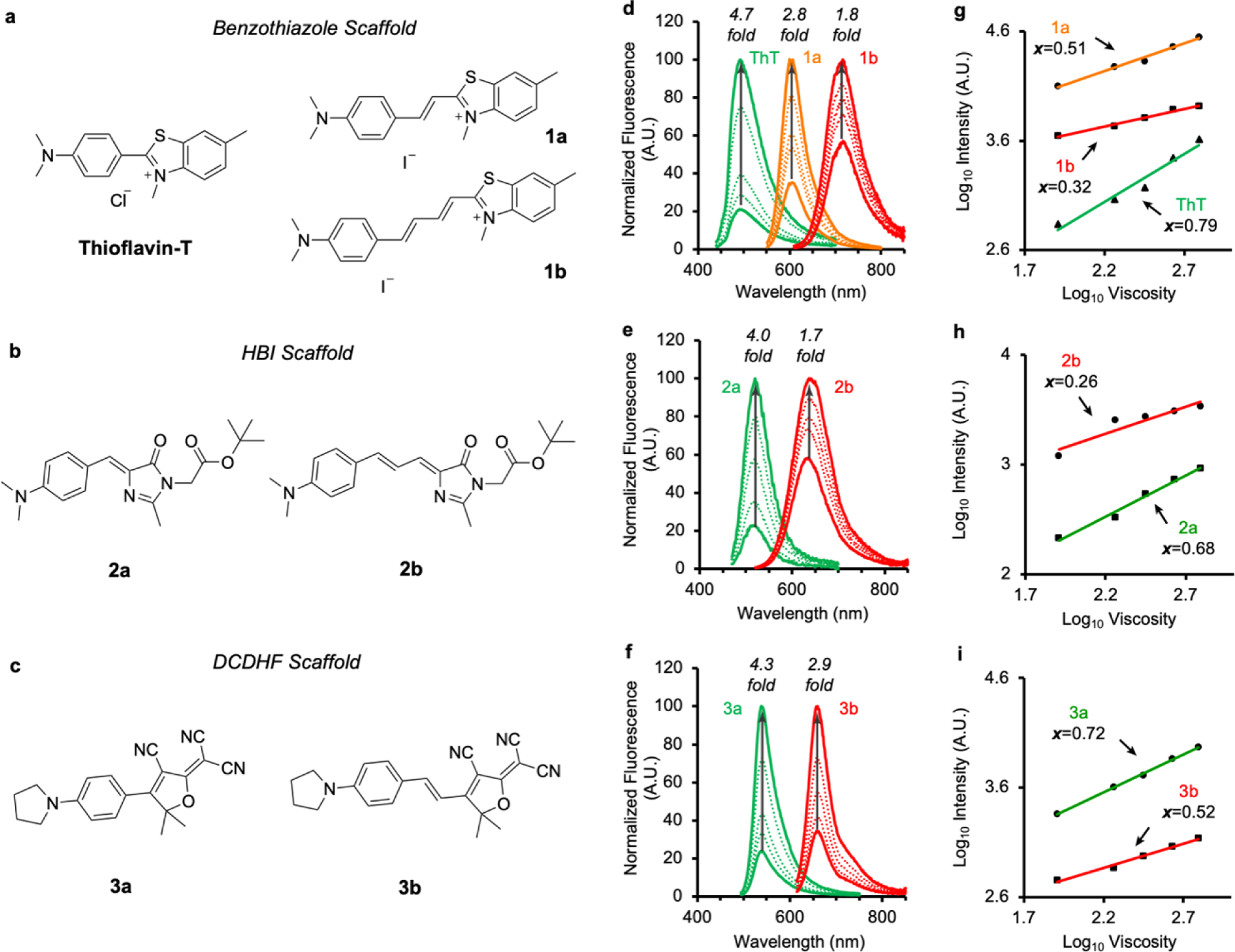

The Arrhenius equation allows us to predict how fluorescence intensity of RBFs is dependent on temperature and viscosity. In this regard, two models are envisioned for RBFs with low and high Ea values. In the first model, where Ea is minimal (<kBT) (Figure 3a, top panel), the above Arrhenius equation could be simplified to , suggesting that the kinetics of internal rotation is a temperature-independent process. Therefore, when we measure the fluorescence intensity in methanol and glycerol mixtures at different temperatures, we expect to observe that the fluorescence intensity is dependent solely on viscosity but not temperature. In other words, an overlap of fluorescence intensity on different temperatures is expected[15]. In the second model, where a high Ea (>>kBT) is expected (Figure 3a, bottom panel), both solvent viscosity and temperature could affect krot, and therefore expected results are dependent on viscosity of the experiments. When solvent viscosity is low, the pre-exponential factor was small that only marginal krot differences are expected at different temperatures. As a result, we predicted a good overlapping for fluorescence intensity in the low viscosity region at different temperatures. As the solvent viscosity increases, the pre-exponential factor becomes more dominant. In this scenario, a temperature dependence phenomenon is projected for RBFs with high Ea at high viscosity.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence reflects the magnitude of the rotational energy barrier (Ea) of RBFs. (a) Proposed models suggest that heights of rotational energy barriers determine the fluorescence intensity pattern in the solvents with different viscosity at different temperatures. While two ideal cases are listed as a low energy barrier and a high energy barrier, the real RBFs usually are in between these two ideal cases. (b) Fluorescence pattern of ThT and 1a.

We measured fluorescence emission intensity of RBFs at varying temperatures and viscosities. ThT and 1a were chosen as an initial set of RBFs, with the expectation that their linkages could generate either low or high Ea values. For ThT with a single bond as linkage, we observed that the fluorescence measure at different temperatures overlaps well (Figure 3b, left panel), despite minor deviations. This result showed that the internal rotation of ThT at excited state operates in a temperature-independent manner, indicating a minimal Ea as the model I suggested. A previous study calculated Ea of ThT to be close to thermal fluctuation (kBT)[12a], which further corroborate our finding. When the same experiments were carried out using 1a with an extended linkage (Figure 3b, right panel), results were more consistent with the model II. The fluorescence intensity difference of 1a at various temperatures became greater as we increased solvent viscosity, suggesting a high Ea for 1a. Besides benzothiazole scaffold, similar trend was observed in both HBI scaffold and DCDHF scaffold (Figure S8). This Ea change, accompanied by incorporating π-rich alternating linkages, would significantly alter the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs, through rerouting the energy dissipation pathway at excited state. When buried in high viscosity environment, RBFs dissipate most absorbed photon energy through fluorescence since internal rotations are inhibited by local compactness. Even when the environmental viscosity is reduced, RBFs with high Ea would maintain a higher fraction of fluorescence compared to their low Ea analogs, because high Ea would hinder the rotation process leading to non-radiative internal conversion. Consequently, RBFs with high Ea exhibit a low viscosity sensitivity x. Collectively, these results suggested that the introduction of π-rich linkage will increase the Ea for RBFs, therefore reduce their viscosity sensitivity.

Previously, the incorporations of extended π conjugation were reported on other fluorophores with different turn-on mechanism. Ashoka et al. reported an enhanced polarity sensitivity of dioxaborine probe with extended π conjugation, indicating the extended π conjugation might increase the charge transfer character for solvatochromic dye[16]. Vu et al. revealed the extended conjugation in phenyl-BODIPY fluorophore—a class of RBF operates with photoinduced electron transfer (PET) mechanism—exhibited reduced viscosity sensitivity and enhanced temperature sensitivity[17]. These works, along with our investigation for RBFs with extended π linkages, should provide a comprehensive understanding as how extended π conjugation modification would alter the photophysical properties of different fluorophores, and facilitate future design of fluorophores with controlled fluorogenicity.

RBFs with extended linkers enable an early detection of low-viscosity misfolded protein oligomers in-vitro

RBFs have been widely applied as powerful fluorogenic probes that can report on biological events that involve viscosity changes. For instance, RBFs have been extensively used to study protein aggregation—a process that starts from the formation of soluble protein oligomers with low-viscosity and gradually evolves into insoluble protein aggregates with high-viscosity[9]. Given that the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs was tunable by varying linkages, we asked whether this structural change could affect the detection of protein aggregation. Because RBFs with extended linkers exhibit lower x values, therefore we expect them to maintain a strong fluorescence in misfolded protein oligomers that have low viscosity. By contrast, RBFs with higher x values are envisioned to only emit strong fluorescence in a high viscous environment such as insoluble aggregates, as their high x values — a steeper fluorescence intensity change as a function of viscosity — would result in low fluorescence quantum yield in the less viscous environment, losing their resolution to resolve protein oligomers. (See Table S4, Figure S9 and Note S1 regarding the resolution of fluorophore in different viscosity regions).

During protein aggregation, a reduced local polarity is accompanied with enhanced viscosity because of the exposed hydrophobic protein cores. Without careful characterization, this would complicate the analysis since most fluorophores with electron “push-pull” nature often exhibit solvatochromic behavior[18]. Here, benzothiazolium class fluorophores are chosen as model compounds to detect protein aggregations as their fluorogenic response are predominantly coming from enhanced viscosity, not from reduced polarity (Figures S3 and S5, Table S2).

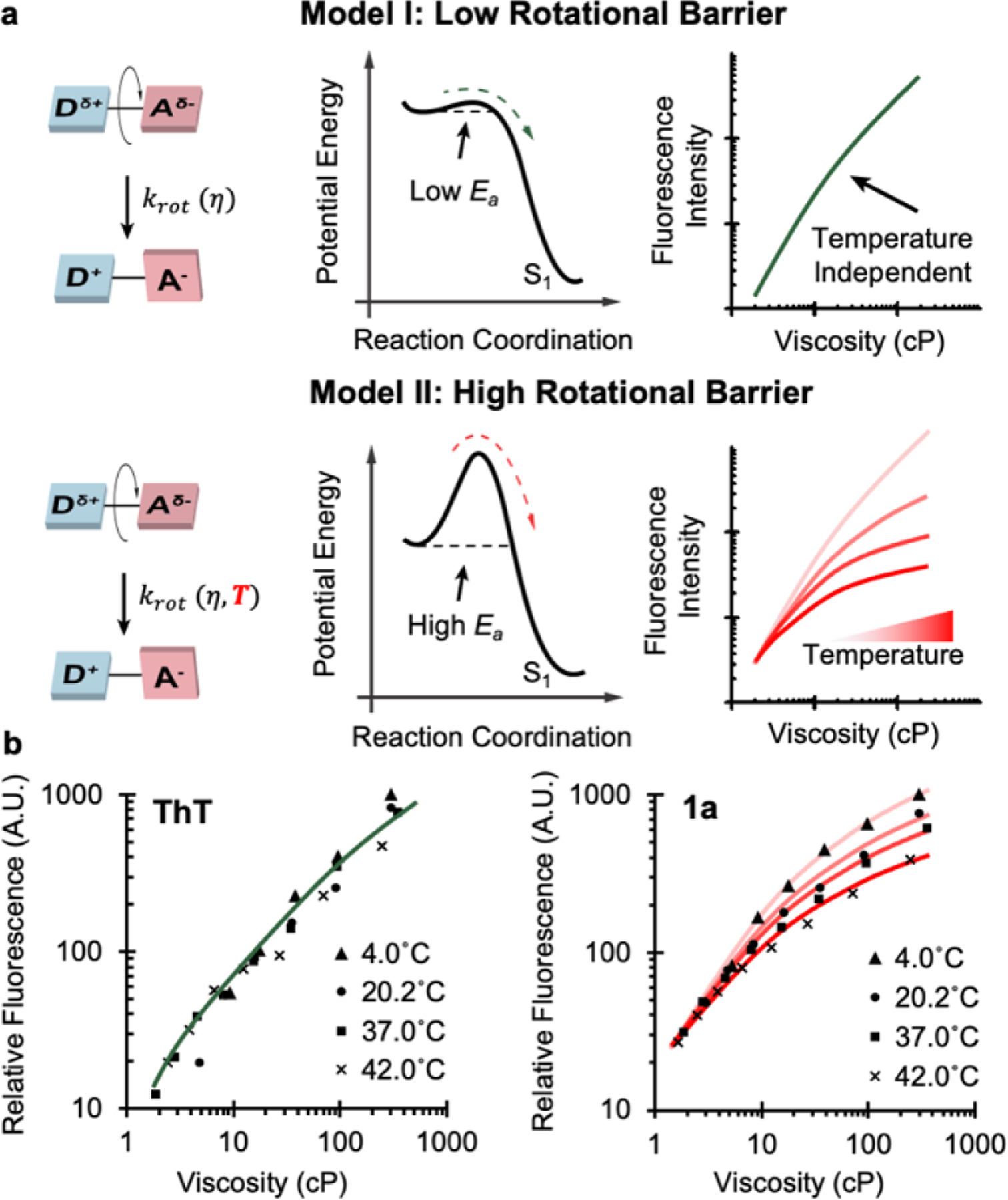

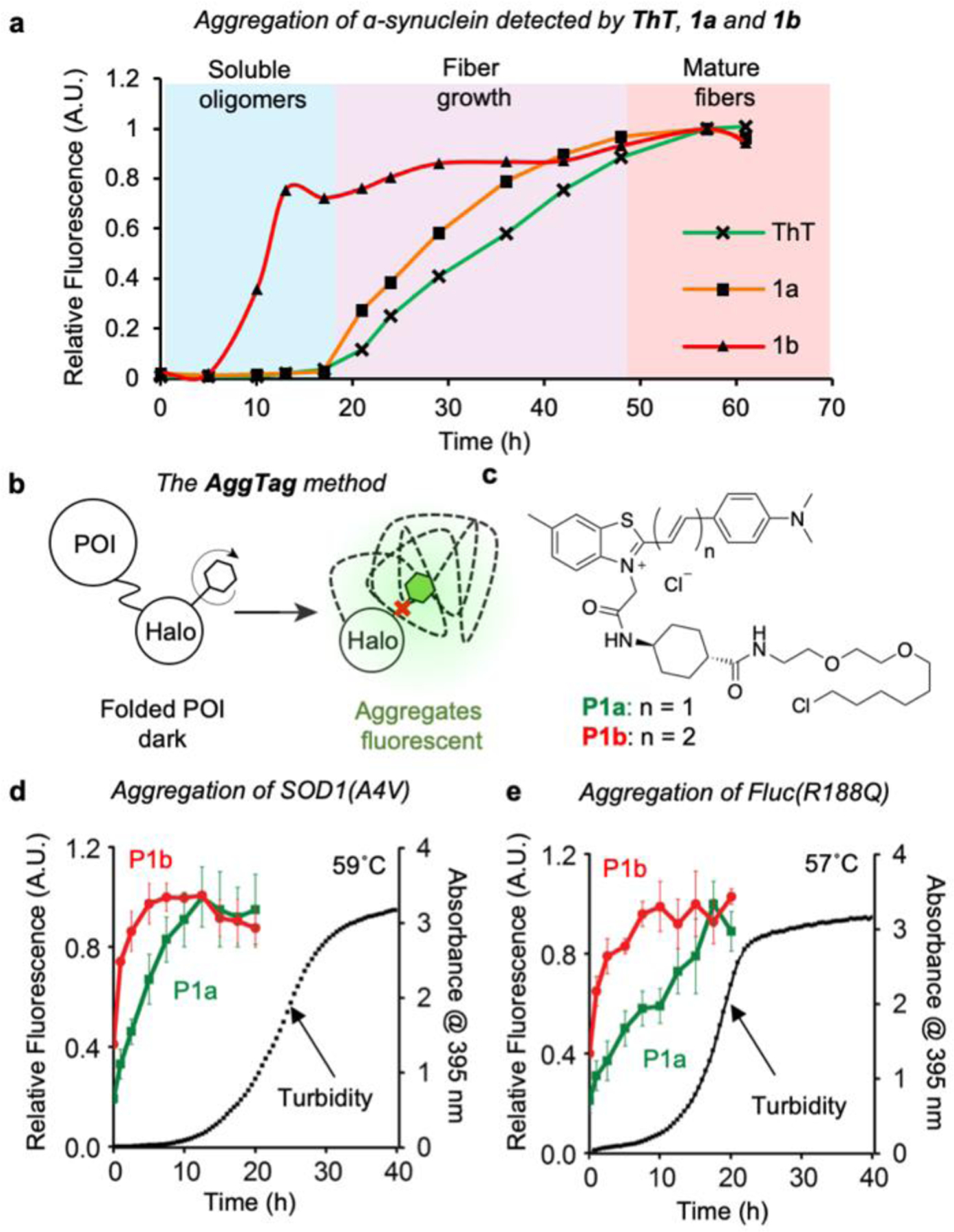

Previously, benzothiazolium class fluorophore has been reported to detect amyloid fibers which are associate with neurodegenerative diseases, including α-synuclein[19], Tau protein[20], amyloid ß[21], etc. To this end, we monitored the aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn) with ThT, 1a and 1b under prolonged agitation (Figure 4a). Aggregation of α-syn turned folded monomers into amyloid fibers via the formation of misfolded oligomers, termed protofibrils[22]. Despite that ThT was able to monitor the fibrilization of α-syn[23], it showed minimal fluorescent signal from 0–18 h (Figure S10a), largely because ThT cannot detect protofibrils that have been shown to be the primary species accumulated between 4–18 h under identical experimental conditions[9a]. Although 1a failed to detect α-syn protofibrils (Figure S10b), its fluorescent intensity increased faster than that of ThT, suggesting a better resolution to detect early stages of fibrilization compared to ThT. By contrast, 1b exhibited enhanced fluorescence as early as 5 h when protofibrils start to appear. A 29-fold fluorescence intensity increase was further observed at 13 h (Figure S10c). This observation indicates that the fluorescence signal for 1b is predominantly coming from low viscosity oligomeric protofibrils. Given that the x values decrease in the sequence of ThT, 1a and 1b, these results collectively support the notion that RBFs with higher Ea values (corresponding to lower x values) are more suited to detect low-viscosity protein oligomers and early-stage fibrilization species. Whereas, RBFs with lower Ea values (corresponding to higher x values) only detect high-viscosity insoluble aggregates and late-stage fibrils.

Figure 4.

Extended RBFs enable the detection of misfolded protein oligomers in vitro. (a) Detection of α-synuclein aggregation by ThT, 1a and 1b. (b) Scheme of the AggTag method to monitor protein aggregation. (c) Structure of P1a and P1b. (d-e) Aggregation of (d) SOD1(A4V) at 59 ºC and (e) Fluc(R188Q) at 57 ºC are monitored by the fluorescence intensity of P1a and P1b, as well as the increased turbidity. In both experiments, 42 µM proteins were incubated with 5 µM probes prior to heat-induced aggregation.

Beyond proteins that form amyloid fibrils, we also examined whether a similar trend would be observed for proteins that form amorphous aggregates. Following an established AggTag method that can report POI aggregation through enhanced fluorescence[9], we genetically fused HaloTag onto protein-of-interest (POI) whose aggregation is known to form amorphous aggregates (Figure 4b). Subsequently, we installed HaloTag reactive warhead to 1a and 1b (Figure 4c), resulting in P1a and P1b as HaloTag substrates that can covalently react with the POI-HaloTag fusion protein (Figure 4b). Both P1a and P1b incorporate a rigid cyclohexane linker to avoid undesired fluorescence response as a result of interacting with HaloTag surfaces (Figures S11 and S12). When P1a or P1b is covalently conjugated to the POI-Halo protein, fluorescence of probes is quenched. Formation of misfolded oligomers and/or insoluble aggregates of the POI, however, inhibits quenching and yields turn-on fluorescence via intra-molecular interactions with probes (Figure 4c).

We first chose superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), mutations of which lead to protein aggregation that have been reported to damage motor neurons and associate with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (fALS)[24]. In particular, SOD1 (A4V) mutation is commonly found in North America and cause rapid disease progression[25]. Upon incubating P1b conjugated SOD1(A4V)-Halo at 59˚C, the fluorescence of P1b reached a maximum at 5 min, surpass the kinetics of P1a, whose fluorescence plateaued at 12.5 min. Notably, both probes showed faster kinetics than turbidity, a signal that is predominantly coming from insoluble protein aggregates. In addition to SOD1(A4V), a destabilized mutant of firefly luciferase Fluc(R188Q) was tested with the identical method[26]. Similarly, fluorescence of P1b was activated earlier than P1a, indicating that RBFs with lower x values are suitable to detect early events, in particular the intermediate misfolded oligomers during protein aggregation. Collectively, these data suggest that tuning down x values through attaching extended linkers may serve as a novel approach to modify RBFs to enable enhanced sensitivity towards biological events with low viscosity.

RBFs with extended linkers enable an enhanced sensitivity towards low-viscosity misfolded protein oligomers during live-cell imaging

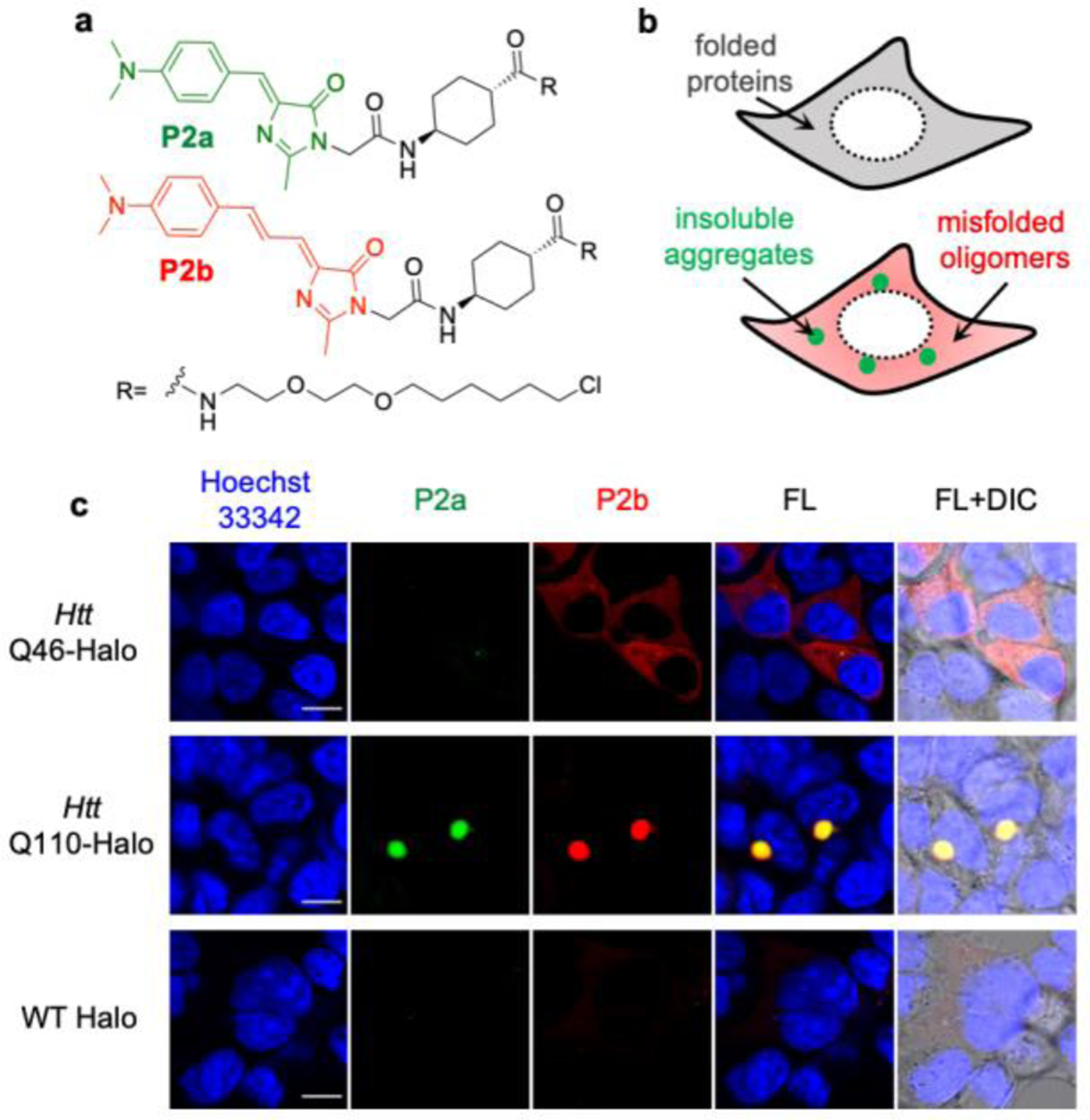

Finally, we applied RBFs with distinct x values in live-cell imaging to differentiate biological events that bear varying viscosities. As a demonstration, we elected to develop an imaging strategy to differentiate misfolded oligomers (low viscosity) from insoluble aggregates (high viscosity) in live cells[27]. To this end, we synthesized HBI-based HaloTag substrates P2a (x = 0.68) and P2b (x = 0.26) (Figure 5a). The zero net charge has enabled a good cell membrane permeability for HBI derivatives (P2a and P2b) compared to the positively charged benzothiazolium derivatives (P1a and P1b), whose fluorescent signal was mostly found when binding with extracellular cell debris in live cell imaging applications (Figure S13). Similar to P1a and P1b, the x values of P2a and P2b determine how they can differently activate fluorescence in response to local viscosity. Because P2a has a higher x value than P2b, we expect that the viscosity to activate fluorescence of P2a would be much higher than that of P2b. More importantly, the fluorescence responses for HBI class fluorophores are predominantly resulted from enhanced viscosity during protein aggregation, as their fluorescence showed minimal response in solvents with different polarities (Figures S4 and S5, Table S2). Given that P2a and P2b exhibit non-overlapping fluorescence spectra (Figure S2), we envision a dual-probe imaging strategy wherein P2b emits fluorescence as soon as misfolded oligomers form and P2a only is activated by the much more tightly packed insoluble aggregates.

Figure 5.

Live cell imaging to demonstrate that extended (P2b) and simple (P2a) RBFs detect the misfolded protein oligomers and insoluble aggregates, respectively. (a) Structure of P2a and P2b. (b) Scheme of how P2b and P2a detect the less viscous misfolded protein oligomers (as the diffusive signal) and highly compact insoluble protein aggregates (as the punctate signal), respectively. (c) Images of Htt-46Q (top panel), Htt-110Q (middle panel) and WT Halo (bottom panel) using P2a and P2b. HEK293T cells were treated with 0.5 µM of P2a and P2b during transfection of desired proteins. Proteins were expressed for 48 h and excess probes were washed away prior to confocal fluorescence imaging. Scale bar: 10 µm.

To demonstrate this two-color imaging strategy, we chose Htt-polyQ, which code for the Huntingtin exon 1 protein with expansion of a polyglutamine tract within its N-terminal domain[28]. The aggregation of Htt-polyQ that contains long-repeats of polyQ (> 36Q) is well known for its association with Huntington’s disease. To test how P2a and P2b activate their fluorescence emission in misfolded oligomers and/or insoluble aggregates, we expressed HaloTag-fused Htt-46Q and Htt-110Q in HEK293T cells and treated cells with equal concentration (0.5 µM) of P2a and P2b during protein translation. Overexpression of Htt-46Q has been found to form soluble oligomers in the cytosol in mammalian cells, while Htt-110Q coalesce into dense insoluble aggresomes[29]. While P2a showed notable fluorescence signal in Htt-110Q-Halo (middle panel in Figure 5c), no significant fluorescence was detected in cells expressed Htt-46Q (top panel in Figure 5c). This quenched P2a fluorescence was not caused by the low expression level of Htt-46Q-Halo, whose expression level was confirmed by the fluorescence signal from P2b (top panel in Figure 5c). Thus, these data suggest that fluorescence of P2a is unable to be activated by misfolded oligomers as these oligomers tend to be loosely packed. P2b, on the other hand, not only showed punctuated fluorescence in cells expressed Htt-110Q-Halo (middle panel in Figure 5c) but also exhibited a strong diffusive fluorescent structure for Htt-46Q-Halo (top panel in Figure 5c). Such turn-on fluorescence of P2b was not observed in cells expressing HaloTag (known not to misfold or aggregate, bottom panel in Figure 5c). Compared to the HaloTag, Htt-46Q-Halo induced a 4-fold fluorescence increase (Figure S14), suggesting that the diffusive P2b fluorescence of Htt-46Q-Halo arises from misfolded oligomers. In summary, these results indicated that controlling viscosity sensitivity of RBFs could enable a two-color imaging strategy to distinguish misfolded oligomers from insoluble aggregates in live cells, thus potentiate an unprecedented imaging capacity to examine how small molecule proteostasis regulators can intervene the process of protein aggregation. Going beyond the AggTag method, a similar two-color imaging strategy with non-covalent recognition of aggregates of different proteins can be achieved by combining RBFs with varying π-rich linkages with established recognition motif towards aggregates of specific proteins.

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrated that the installation of extended π-rich linkage between electron donor and acceptor is a general method to control the viscosity sensitivity of RBFs. Compared to RBFs with a simple single bond linkage, RBFs with extended π-rich linkages harbor higher rotational energy barriers (Ea) between the planar fluorescent configuration and the dark twisted configuration. As a result, RBFs with extended linkers exhibit lower x values as a measure of their viscosity sensitivity and could activate their fluorescence emission at much lower viscosities. This mechanism allows for the design of three scaffolds of RBF derivatives that span a wide range of viscosity sensitivities (x = 0.26 to 0.79). Using RBFs with desired viscosity sensitivities and distinct emission spectra, we were able to present a dual-color imaging strategy that can differentiate misfolded protein oligomers and insoluble aggregates both in test tubes and live cells. Because this control is exerted via the linkage between electron donor and acceptor of fluorophores, we envision that this chemical mechanism and design might also be generally applicable to a wide range of RBFs, photoisomerizable fluorophores and molecules with aggregation-induced emission properties. The capacity to produce fluorophores with rationally tunable rotational barriers could potentiate novel applications in biological systems, membrane chemistry and material science.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank support from the Burroughs Welcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface 1013904 (X.Z.), Paul Berg Early Career Professorship (X.Z.), Lloyd and Dottie Huck Early Career Award (X.Z.), Sloan Research Fellowship FG-2018–10958 (X.Z.), PEW Biomedical Scholars Program 00033066 (X.Z.), and National Institute of Health R35 GM133484 (X.Z.). We thank Dr. Gang Ning and Ms. Missy Hazen of the Penn State Microscopy Core Facility and Dr. Tatiana Laremore of the Penn State Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Core Facility for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].a) Haidekker MA, Theodorakis EA, Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 1669–1678; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Haidekker MA, Theodorakis EA, J. Biol. Eng 2010, 4, 11; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hong Y, Lam JW, Tang BZ, Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 5361–5388; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mei J, Leung NLC, Kwok RTK, Lam JWY, Tang BZ, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 11718–11940; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Gozem S, Luk HL, Schapiro I, Olivucci M, Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 13502–13565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Kuimova MK, Yahioglu G, Levitt JA, Suhling K, J. Am. Chem. So.c 2008, 130, 6672–6673; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goh WL, Lee MY, Joseph TL, Quah ST, Brown CJ, Verma C, Brenner S, Ghadessy FJ, Teo YN, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 6159–6162; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yu WT, Wu TW, Huang CL, Chen IC, Tan KT, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 301–307; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kuimova MK, Botchway SW, Parker AW, Balaz M, Collins HA, Anderson HL, Suhling K, Ogilby PR, Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 69–73; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Liu X, Chi WJ, Qiao QL, Kokate SV, Cabrera EP, Xu ZC, Liu XG, Chang YT, ACS Sensors 2020, 5, 731–739; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) You MX, Jaffrey SR, Annu. Rev. Biophys 2015, 44, 187–206; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Qian J, Tang BZ, Chem 2017, 3, 56–91; [Google Scholar]; h) Liang J, Tang B, Liu B, Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 2798–2811; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Nienhaus K, Nienhaus GU, Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 1088–1106; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Chan J, Dodani SC, Chang CJ, Nat. Chem 2012, 4, 973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Levitt JA, Kuimova MK, Yahioglu G, Chung PH, Suhling K, Phillips D, J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 11634–11642; [Google Scholar]; b) Kuimova MK, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2012, 14, 12671–12686; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yu WT, Wu TW, Huang CL, Chen IC, Tan KT, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 301–307; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jung KH, Fares M, Grainger LS, Wolstenholme CH, Hou A, Liu Y, Zhang X, Org. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 1906–1915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Fares M, Li Y, Liu Y, Miao K, Gao Z, Zhai Y, Zhang X, Bioconjug. Chem 2018, 29, 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chen MZ, Chen MZ, Moily NS, Bridgford JL, Wood RJ, Radwan M, Smith TA, Song Z, Tang BZ, Tilley L, Xu X, Reid GE, Pouladi MA, Hong Y, Hatters DM, Nat. Commun, 2017, 8, 474–481; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zhang S, Liu M, Tan LYF, Hong Q, Pow ZL, Owyong TC, Ding S, Wong WWH, Hong Y, Chem. Asian J, 2019, 6, 904–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Grabowski ZR, Rotkiewicz K, Rettig W, Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 3899–4032; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sasaki S, Drummen GP, Konishi G.-i., J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 2731–2743. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Sasaki S, Drummen GPC, Konishi G, J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 2731–2743; [Google Scholar]; b) Qian H, Cousins ME, Horak EH, Wakefield A, Liptak MD, Aprahamian I, Nat. Chem 2017, 9, 83–87; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Grimm JB, English BP, Chen JJ, Slaughter JP, Zhang ZJ, Revyakin A, Patel R, Macklin JJ, Normanno D, Singer RH, Lionnet T, Lavis LD, Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 244–250; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Grimm JB, Muthusamy AK, Liang YJ, Brown TA, Lemon WC, Patel R, Lu RW, Macklin JJ, Keller PJ, Ji N, Lavis LD, Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 987–994; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Romei MG, Lin CY, Mathews II, Boxer SG, Science 2020, 367, 76–79; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Park JW, Rhee YM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13619–13629; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Wang L, Tran M, D’Este E, Roberti J, Koch B, Xue L, Johnsson K, Nat. Chem 2020, 12, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jablonski A, Nature 1933, 131, 839–840. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Valeur B, Dig.l Encycl. Appl. Phys 2003, 477–531. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Loutfy RO, Macromolecules 1983, 16, 678–680. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Liu Y, Wolstenholme CH, Carter GC, Liu H, Hu H, Grainger LS, Miao K, Fares M, Hoelzel CA, Yennawar HP, Ning G, Du M, Bai L, Li X, Zhang X, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 7381–7384; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jung KH, Kim SF, Liu Y, Zhang X, ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 1078–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dugave C, Demange L, Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2475–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Pronkin P, Tatikolov A, Sci 2019, 1, 19; [Google Scholar]; b) Baraldi I, Carnevali A, Caselli M, Momicchioli F, Ponterini G, Berthier G, J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1995, 330, 403–410; [Google Scholar]; c) Schöffel K, Dietz F, Krossner T, Chem. Phys. Lett 1990, 172, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Stsiapura VI, Maskevich AA, Kuzmitsky VA, Uversky VN, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 15893–15902; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Biancalana M, Koide S, Bioch. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1405–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Tsien RY, Ann. Rev. Biochem 1998, 67, 509–544; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang F, Moss LG, Phillips GN, Nat. Biotech 1996, 14, 1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Förster T, Hoffmann G, Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 1971, 75, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vyšniauskas A, Qurashi M, Gallop N, Balaz M, Anderson HL, Kuimova MK, Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 5773–5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ashoka AH, Ashokkumar P, Kovtun YP, Klymchenko AS, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 2414–2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vu TT, Meallet-Renault R, Clavier G, Trofimov BA, Kuimova MK, J Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 2828–2833. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Klymchenko AS, Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT, Biochem 2000, 39, 2552–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maruyama M, Shimada H, Suhara T, Shinotoh H, Ji B, Maeda J, Zhang MR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Ono M, Masamoto K, Takano H, Sahara N, Iwata N, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Kudo Y, Chang Q, Saido TC, Takashima A, Lewis J, Jang MK, Aoki I, Ito H, Higuchi M, Neuron 2013, 79, 1094–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Klunk WE, Wang YM, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Mathis CA, Life Sci 2001, 69, 1471–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Goedert M, Nat. Rev. Neur 2001, 2, 492–501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lashuel HA, Petre BM, Wall J, Simon M, Nowak RJ, Walz T, Lansbury PT, J. Mol. Biol 2002, 322, 1089–1102; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M, Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Giehm L, Lorenzen N, Otzen DE, Methods 2011, 53, 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Rosen DR, Nature 1993, 364, 362–362; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Slunt HS, Guarnieri M, Xu ZS, Wong PC, Brown RH, Price DL, Sisodia SS, Cleveland DW, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8292–8296; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Bruijn LI, Houseweart MK, Kato S, Anderson KL, Anderson SD, Ohama E, Reaume AG, Scott RW, Cleveland DW, Science 1998, 281, 1851–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cudkowicz M, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp P, Chin W, Geller B, Hayden D, Schoenfeld D, Hosler B, Horvitz H, Brown R, Ann. Neur 1997, 41, 210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gupta R, Kasturi P, Bracher A, Loew C, Zheng M, Villella A, Garza D, Hartl FU, Raychaudhuri S, Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Matsumoto G, Kim S, Morimoto RI, J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 4477–4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel J, Aronin N, Science 1997, 277, 1990–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Krobitsch S, Lindquist S, P. Natl. Acad. Sci 2000, 97, 1589–1594; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Johnston JA, Ward CL, Kopito RR, J. Cell Biol 1998, 143, 1883–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.