Abstract

Background

Preterm and low birth weight infants are born with low stores in zinc, which is a vital trace element for growth, cell differentiation and immune function. Preterm infants are at risk of zinc deficiency during the postnatal period of rapid growth. Systematic reviews in the older paediatric population have previously shown that zinc supplementation potentially improves growth and positively influences the course of infectious diseases. In paediatric reviews, the effect of zinc supplementation was most pronounced in those with low nutritional status, which is why the intervention could also benefit preterm infants typically born with low zinc stores and decreased immunity.

Objectives

To determine whether enteral zinc supplementation, compared with placebo or no supplementation, affects important outcomes in preterm infants, including death, neurodevelopment, common morbidities and growth.

Search methods

Our searches are up‐to‐date to 20 February 2020. For the first search, we used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 8), MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 29 September 2017), Embase (1980 to 29 September 2017), and CINAHL (1982 to 29 September 2017). We also searched clinical trials databases, conference proceedings, and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. We ran an updated search from 1 January 2017 to 20 February 2020 in the following databases: CENTRAL via CRS Web, MEDLINE via Ovid, and CINAHL via EBSCOhost.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs that compared enteral zinc supplementation versus placebo or no supplementation in preterm infants (gestational age < 37 weeks), and low birth weight babies (birth weight < 2500 grams), at any time during their hospital admission after birth. We included zinc supplementation in any formulation, regimen, or dose administered via the enteral route. We excluded infants who underwent gastrointestinal (GI) surgery during their initial hospital stay, or had a GI malformation or another condition accompanied by abnormal losses of GI juices, which contain high levels of zinc (including, but not limited to, stomas, fistulas, and malabsorptive diarrhoea).

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal. Two review authors separately screened abstracts, evaluated trial quality and extracted data. We synthesised effect estimates using risk ratios (RR), risk differences (RD), and standardised mean differences (SMD). Our primary outcomes of interest were all‐cause mortality and neurodevelopmental disability. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We included five trials with a total of 482 preterm infants; there was one ongoing trial. The five included trials were generally small, but of good methodological quality.

Enteral zinc supplementation compared to no zinc supplementation

Enteral zinc supplementation started in hospitalised preterm infants may decrease all‐cause mortality (between start of intervention and end of follow‐up period) (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.97; 3 studies, 345 infants; low‐certainty evidence). No data were available on long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 24 months of (post‐term) age. Enteral zinc supplementation may have little or no effect on common morbidities such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.40, 1 study, 193 infants; low‐certainty evidence), retinopathy of prematurity (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.70, 1 study, 193 infants; low‐certainty evidence), bacterial sepsis (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.04, 2 studies, 293 infants; moderate‐certainty evidence), or necrotising enterocolitis (RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.33, 1 study, 193 infants; low‐certainty evidence).

The intervention probably improves weight gain (SMD 0.46, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.64; 5 studies, 481 infants; moderate‐certainty evidence); and may slightly improve linear growth (SMD 0.75, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.14, 3 studies, 289 infants; low‐certainty evidence), but may have little or no effect on head growth (SMD 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.44, 3 studies, 289 infants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Enteral supplementation of zinc in preterm infants compared to no supplementation or placebo may moderately decrease mortality and probably improve short‐term weight gain and linear growth, but may have little or no effect on common morbidities of prematurity. There are no data to assess the effect of zinc supplementation on long‐term neurodevelopment.

Keywords: Humans; Infant; Infant, Newborn; Bacterial Infections; Bacterial Infections/prevention & control; Bias; Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia; Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia/prevention & control; Cause of Death; Enteral Nutrition; Enterocolitis, Necrotizing; Enterocolitis, Necrotizing/prevention & control; Infant Mortality; Infant, Low Birth Weight; Infant, Low Birth Weight/growth & development; Infant, Premature; Infant, Premature/growth & development; Morbidity; Retinopathy of Prematurity; Retinopathy of Prematurity/prevention & control; Trace Elements; Trace Elements/administration & dosage; Trace Elements/deficiency; Zinc; Zinc/administration & dosage; Zinc/deficiency

Plain language summary

Enteral zinc supplementation for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates

Review question: do preterm infants (babies born early) die less often and develop and grow better when they receive extra zinc by way of the stomach?

Background: zinc is an important trace element required by babies to grow well and to fight infections. When babies are born early, they miss out on the transfer of many important nutrients from the mother through the umbilical cord which would normally happen in the last weeks of pregnancy. Therefore, their zinc stores are low. Adding extra zinc to the milk of preterm babies might mean that they grow and develop better and get less sick from complications which often affect babies born too early, and therefore die less often.

Study characteristics: we included five small trials (482 preterm infants) which were all of reasonably strong design. There was one ongoing study. The search for trials is up‐to‐date as of 20 February 2020.

Key results: preterm babies who received extra zinc by way of the stomach (a maximum of 10 mg per day either by mouth or through a feeding tube) while they were still in hospital probably die less often, probably put on weight and grew slightly better in length than those preterm babies who did not receive extra zinc. Extra zinc probably makes little to no difference to common problems in preterm babies such as chronic lung or eye problems, infection with bacteria or bowel problems. The trials which we included in this review did not have any information on the effect of extra zinc on the development later in life of the babies such as their ability to walk, their hearing or vision, language or their intelligence. We did not find indications of adverse effects of the extra zinc given to the babies. New and larger trials are needed to learn more about the effect on long‐term development and growth when zinc is given by way of the stomach to babies born early.

Certainty of evidence: we assessed the evidence from the included trials on the effects of extra zinc in preterm babies as being of 'low‐ to moderate‐certainty', because the trials were small, some had a few methodological weaknesses and the reported findings were inconsistent with each other for some of the outcomes. This means that further research through larger trials will likely provide important contributions to the existing knowledge and increase our confidence in the results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Enteral zinc supplementation compared to no zinc supplementation for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates.

| Enteral zinc supplementation compared to no zinc supplementation for prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates | ||||||

| Patient or population: preterm infants Setting: healthcare setting in Spain, Canada, Bangladesh, India, Italy Intervention: enteral zinc supplementation Comparison: no zinc supplementation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | ||||||

| No zinc supplementation | Risk difference with enteral zinc supplementation | |||||

| All‐cause mortality (between start of intervention and end of follow‐up period) | 169 per 1,000 | 76 fewer per 1,000 (from 116 fewer to 3 fewer) | RR 0.55 (0.31 to 0.97) | 345 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | |

| Neurodevelopmental disability at 18 to 24 months | see comment | see comment | not estimable | 0 | ‐ | None of the included studies examined this outcome. |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 156 per 1000 | 53 fewer per 1000 (from 108 fewer to 62 more) | RR 0.66 (0.31 to 1.40) | 193 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | |

| Retinopathy of prematurity | 31 per 1000 | 27 fewer per 1000 (from 31 fewer to 53 more) | RR 0.14 (0.01 to 2.70) | 193 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | |

| Bacterial sepsis | 116 per 1000 | 13 more per 1000 (47 fewer to 121 more) | RR 1.11 (0.60 to 2.04) | 293 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 63 per 1000 | 58 fewer per 1000 (63 fewer to 21 more) | RR 0.08 (0.00 to 1.33) | 193 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | |

| Change in growth (between start and end of intervention, between 6 weeks to 6 months) | Weight gain | |||||

| SMDe 0.46 higher (0.28 higher to 0.64 higher) | ‐ | 481 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | |||

| Linear growth | ||||||

| SMDe 0.75 higher (0.36 higher to 1.14 higher) | ‐ | 289 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,d | |||

| Head growth | ||||||

| SMDe 0.21 higher (0.02 lower to 0.44 higher) | ‐ | 289 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% confidence interval). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardised mean difference | ||||||

|

a Downgraded one level for risk of bias (attrition bias) b Downgraded one level for imprecision of effect estimate (95% CI consistent with very small to very large effect) c Downgraded one level for imprecision due to small sample size and/or low event rate (only one study included in analysis) d Downgraded one level for inconsistencies in effect estimates (moderate heterogeneity, I2 > 50%) e According to Cohen's rule of thumb, effect sizes for SMD are interpreted as: 0.2 small effect, 0.5 moderate effect, 0.8 large effect (Cohen 1988) | ||||||

Background

Zinc is a trace element that acts as a co‐factor in more than 300 metalloenzymes, through which it is involved in growth, cell differentiation, gene transcription, major pathways of metabolism, and hormone and immune function. Therefore, zinc is important for normal growth, tissue maintenance, and wound healing (Livingstone 2015). Zinc is absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract into enterocytes and is entered into the plasma pool. The human organism has no dedicated zinc store. Rather, in states of excessive or decreased zinc intake, homeostasis is regulated through GI absorption, excretion via faeces or urine, and retention or release by selected tissues (King 2000).

Description of the condition

Overt zinc deficiency in children is associated with stunted growth, immunosuppression, and a phenotypical skin disorder with diarrhoea (similar to the autosomal recessive acrodermatitis enteropathica), which was first described in the 1960s (Hambidge 2000). In low‐income and middle‐income countries, where the prevalence of zinc deficiency is highest, zinc supplementation in children has been shown to be an effective intervention for improvement of growth and prevention of infectious disease (Bhutta 1999; Brown 1998; Wessells 2012). More subtle zinc deficiency is difficult to diagnose owing to lack of reliable laboratory markers and less specific signs and symptoms (Hambidge 2000; King 2000).

Preterm infants start out with a smaller zinc pool than term infants, because 60% of zinc accretion takes place during the last trimester of pregnancy through transplacental transfer (Giles 2007). Accordingly, plasma zinc levels in cord blood are proportionately lower with younger gestational age and lower birth weight (Gomez 2015). Breast milk usually is well equipped with all micronutrients required for optimal growth and development of the term baby, but may not provide enough zinc to match foetal accretion rates and very rapid postnatal growth rates. This leaves preterm and low birth weight babies at risk for symptomatic zinc deficiency. Symptoms of zinc deficiency include failure to thrive despite sufficient caloric intake, dermatitis, and increased susceptibility to infection (Obladen 1998). However, subclinical forms are likely to be more common and often go unrecognised. Some studies estimate the prevalence of subclinical zinc deficiency in preterm infants near term to be as high as 25% to over 50% (Itabashi 2003; Obladen 1998). Diagnosing relevant, yet asymptomatic, zinc deficiency is difficult because of the natural variation in zinc levels noted in preterm infants and the low sensitivity of plasma zinc levels for dietary deficiency (Altigani 1989; King 1990). Furthermore, no data indicate what plasma level of zinc and/or in the presence of which co‐factors, signs of zinc deficiency become clinically manifest in individual patients.

Description of the intervention

Both parenteral and enteral nutrition for preterm infants contain some zinc to prevent zinc deficiency. Recommendations for zinc intake in stable growing preterm infants range from 1 to 2.5 mg/kg/d and up to 3 mg/kg/d for extremely low birth weight infants (Agostoni 2010; Domellof 2014; Kleinman 2014). These recommendations are in line with those provided by various retention studies and generally are met by current preterm formula and breast milk supplements (Finch 2015; Griffin 2013), although there is some limited evidence that zinc might be better absorbed from human milk than from infant formula (Sandstörm 1983). However, in trials studying prevention of various diseases in different paediatric populations including preterm infants, zinc intake is often well above recommended nutrient intake (Bhutta 1999; Friel 1993; Mishra 2015; Terrin 2013b).

How the intervention might work

High growth rates and rapidly developing organs render preterm infants crucially dependent on adequate intake of macronutrients and micronutrients, especially after they have missed out on an important time of transplacental nutrient transfer during the last trimester of pregnancy. Zinc is involved in a large variety of cellular functions, which is why even mild subclinical zinc deficiency could impair global as well as organ‐specific development of the preterm infant, notably of the brain and GI tract (Berni Canani 2010; Levenson 2011). Additionally, preterm infants are less efficient in absorbing and retaining zinc from the GI tract (King 2000; Voyer 1982). Therefore, they may profit from higher intake than mature infants and children for the purpose of improving growth and reducing the risk of morbidities typical for preterm infants, such as sepsis, necrotising enterocolitis, chronic lung disease, abnormal neurodevelopment, and retinopathy of prematurity. Specifically, zinc supplementation could improve immune function and the integrity of skin and mucosal barriers, notably in the GI tract, thereby could decrease feed intolerance, while reducing the incidence of infection and necrotising enterocolitis (Berni Canani 2010; Prasad 2008). Improved growth and cell repair could reduce the severity of chronic lung disease of prematurity. Zinc is also a pivotal trace element in developmental neurogenesis; supplementation could positively affect neuronal differentiation and development during the vulnerable period of prematurity (Levenson 2011). Zinc, the most abundant trace element in the retina, could play a role in normal eye development and function and may provide important antioxidant capacity, even though its role in prevention of retinopathy of prematurity has not been studied so far (Falchuk 1998; Grahn 2001). All of the benefits discussed above show the positive potential of zinc as a single trace element intervention for important clinical outcomes in preterm infants. From the existing literature, it remains unclear whether presumed benefits could be achieved with zinc supplementation over a defined period of a few weeks, or whether positive effects could be increased proportionately with increasing length of the intervention over multiple weeks or months.

Even though zinc supplements are considered relatively safe, enteral administration has the potential to negatively influence copper and iron absorption in the GI tract (Fosmire 1990; Livingstone 2015Obladen 1998; Sugiura 2005). Therefore, zinc supplementation over and above the recommended daily intake requires careful monitoring and evaluation for patients who are dependent on a balanced micronutrient intake.

Why it is important to do this review

Several non‐Cochrane and Cochrane systematic reviews have addressed zinc supplementation in the paediatric population beyond the neonatal age, with some showing beneficial effects on the respiratory tract and on diarrhoeal illness, but others reporting only marginal benefit (Aggarwal 2007; Bhutta 1999; Patel 2011; Roth 2010; Yakoob 2011. A few systematic reviews have reported improved growth following zinc supplementation, but other systematic reviews did not find convincing evidence (Brown 1998; Brown 2002; Imdad 2011; Ramakrishnan 2009). None of these reviews addressed neonates or preterm infants. A single review of three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examined zinc supplementation in breastfed low birth weight infants from low‐income and middle‐income countries on an outpatient basis and found no beneficial effect on mortality, infectious disease, or growth (Gulani 2011). However, no systematic review (Cochrane or non‐Cochrane) to date has addressed the effects of zinc supplementation in preterm low birth weight or very low birth weight infants in the setting of their typically long stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and with regards to growth, mortality, morbidity specific for this population (such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intraventricular haemorrhage, necrotising enterocolitis), and developmental outcome. In reviews involving children beyond neonatal age, effects of zinc supplementation are most pronounced in those with low nutritional status before the intervention is received (Bhutta 1999; Gulani 2011; Yakoob 2011). Given these findings, it is reasonable to hypothesise that preterm babies, who are born with low zinc stores and with diminished capacity for zinc absorption and retention, could benefit from zinc supplements as an easily implemented intervention for growth, immune function, and decreased morbidity (Krebs 2014; Voyer 1982).

Objectives

To determine whether enteral zinc supplementation, compared with placebo or no supplementation, affects important outcomes in preterm infants, including death, neurodevelopment, common morbidities and growth.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised (individual and cluster‐randomised) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of zinc supplementation versus placebo or no intervention in preterm infants with low birth weight. We excluded observational and cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

We included studies that enrolled infants born preterm (gestational age < 37 weeks) and at low birth weight (birth weight < 2500 grams) and admitted to the NICU or the special care unit or a comparable setting after birth. We excluded infants who underwent GI surgery during their initial hospital stay, or had a GI malformation or another condition accompanied by abnormal losses of GI juices, which contain high levels of zinc (including, but not limited to, stomas, fistulas, and malabsorptive diarrhoea). If studies included participants with and without such presumed high GI zinc losses, we contacted study authors to request data on the former and to exclude the other participants from the analysis. If this information was not available, we excluded the respective study as a whole.

Types of interventions

We included zinc supplementation in any formulation, regimen, or dose administered via the enteral route, in addition to a standard nutrition regimen (partial or full enteral feeds, breast milk, or formula) versus placebo or no intervention, starting at any time from birth to hospital discharge. We included trials in which participants received additional macronutrient and micronutrient supplementation and/or multicomponent milk fortification, as long as supplementation was the same in both intervention and non‐intervention/placebo groups, and as long as the only difference between the groups were differences in zinc (and possibly copper) intake.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies even if they did not report all outcomes. If a study did not report all outcomes, we sought further information from trial authors.

Primary outcomes

-

All‐cause mortality

Before hospital discharge (latest time reported at or after 36 weeks' postmenstrual age)

Between hospital discharge and neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term)

-

Neurodevelopmental disability at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term), defined as a neurological abnormality including any of the following:

Cerebral palsy on clinical examination;

Developmental delay > 2 standard deviations (SD) below the population mean on a standardised test of development (Vohr 2004);

Blindness (visual acuity < 6/60);

Deafness (any hearing impairment requiring amplification).

Secondary outcomes

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD, according to Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) criteria, defined as oxygen requirement > 21% at 28 days of life) (Jobe 2001), and breathing room air (mild BPD); oxygen requirement from 22% to 29% (moderate BPD); oxygen requirement > 30% and/or positive pressure (severe BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (for infants born at < 32 weeks' gestation) or at 56 days of life or discharge, whichever is later (for infants born at ≥ 32 weeks' gestation);

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (any stage and stage III or IV);

Bacterial sepsis (proven episodes by means of positive blood culture);

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) (any stage and stage 2 or greater);

Change in growth: between start and end of intervention, from discharge to time of neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term) (absolute growth or change in z‐score for weight, length, and head circumference, where z‐score was defined as deviation of an observed value for an individual from the median value of the reference population, divided by the SD of the reference population) (WHO 1995).

Additional outcomes

Differences in blood zinc levels (in µg/dL or µmol/L) between any time before and during/at the end of the intervention (at the latest time reported before the end of the intervention);

Skin eruptions or dermatitis at any time before or during the intervention as a clinical sign of zinc deficiency.

Indicators of potential adverse effects of zinc supplementation included the following:

Differences in blood iron status (blood iron in µg/dL or µmol/L or ferritin in µg/L) between any time before and during/at the end of the intervention (at the latest time reported before the end of the intervention);

Differences in copper status (blood copper levels in µg/dL or µmol/L, serum ceruloplasmin in µg/dL or µmol/L) between any time before and during/at the end of the intervention (at the latest time reported before the end of the intervention)

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

Electronic searches

After the initial approval of the review protocol, we conducted a comprehensive search including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 8) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 29 September 2017); Embase (1980 to 29 September 2017); and CINAHL (1982 to 29 September 2017) using the following search terms: (zinc), plus database‐specific limiters for RCTs and neonates (see Appendix 1 for the full search strategies for each database). We did not apply language restrictions. We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization’s International Trials Registry and Platform www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/, and the ISRCTN Registry).

We conducted a comprehensive updated search in February 2020 including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2020, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) (1 January 2017 to 20 February 2020); and CINAHL (1 January 2017 to 20 February 2020). We have included the search strategies for each database in Appendix 2. We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched clinical trial registries for ongoing or recently completed trials. We searched The World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/) and the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov) via Cochrane CENTRAL. Additionally, we searched the http://www.isrctn.com/ for any unique trials not found through the Cochrane CENTRAL search.

Searching other resources

We also searched the reference lists of any articles selected for inclusion in this review in order to identify additional relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (Higgins 2020).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ES, KE) independently assessed the eligibility of trials against inclusion and exclusion criteria. We selected studies as potentially relevant by screening title and abstract and, if relevance could not be ascertained by the latter method, by retrieving the full text. For all articles identified as potentially relevant in this first step, we assessed their eligibility from their full‐text version independently in accordance with the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion and documented studies excluded from the review in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, along with the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (ES, KE) independently extracted data from full‐text articles using a specifically designed spreadsheet to manage the information. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, via consultation with a third review arbiter. We entered data into Review Manager 5 software and checked data for accuracy (Review Manager 2020). When information regarding any of the above was missing or unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to clarify and obtain additional details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (ES, KE) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011), for the following domains.

Sequence generation (selection bias);

Allocation concealment (selection bias);

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

Selective reporting (reporting bias);

Any other bias.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by a third assessor. See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We followed standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal for data synthesis, using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). We reported dichotomous data or categorical data using risk ratios (RRs), relative risk differences (RDs), and, for significant risk difference, number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH). We obtained means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous data and performed analysis using mean differences (MDs) and standardised mean differences (SMDs) to combine trials that measured the same outcome using different scales. For each measure of effect, we provided the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). For SMDs, we used Cohen's rule of thumb to interpret effect size: 0.2 small effect, 0.5 moderate effect, 0.8 large effect (Cohen 1988).

Unit of analysis issues

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible). We considered it reasonable to combine the results of individually randomised and cluster‐randomised trials if we noted little heterogeneity between study designs, and if the interaction between effect of the intervention and choice of randomisation unit was considered unlikely.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of all published trials if we required clarification or additional information. In the case of missing data, we described the number of participants with missing data in the Results section and in the Characteristics of included studies table. We presented results only for available participants and explored in the Discussion section implications of the missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity of treatment effects between trials by using the following statistical models (Higgins 2020).

I2 statistic, a quantity that indicates the proportion of variation of point estimates that is due to variability across studies rather than to sampling error (i.e. to ensure that pooling of data is valid). We graded the degree of heterogeneity as none (< 25%), low (25% to 49%), moderate (50% to 74%), or high (75% to 100%).

Chi2 test: a quantity that assesses whether observed variability in effect sizes between studies is greater than would be expected by chance.

When we found evidence of apparent or statistical heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 75%, p < 0.1 for Chi2), we assessed the source of the heterogeneity using sensitivity and subgroup analyses to look for evidence of bias or methodological differences between trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to explore publication bias by using funnel plots if we included at least 10 studies in the systematic review (Egger 1997; Higgins 2020). However, we only included five studies in the Cochrane Review, and so were unable to perform funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We performed statistical analyses according to recommendations of Cochrane Neonatal (http://neonatal.cochrane.org), using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). We analysed all infants randomised on an intention‐to‐treat basis (also when authors did not report intention to treat analysis) as well as treatment effects examined in the individual trials described above. We used a fixed‐effect model to combine data, unless we found moderate heterogeneity, in which case we used a random‐effects model. We used the generic inverse variance method to synthesise risk estimates. When we judged meta‐analysis to be inappropriate (i.e. if heterogeneity was judged high, > 75%), we synthesised and interpreted individual trials separately.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If sufficient data were available, we undertook the following a priori subgroup analysis to explore potential sources of clinical heterogeneity.

Gestational age (< 28 weeks, 28 to 32 weeks, > 32 weeks).

Birth weight (≤ 1500 grams, not limited to ≤ 1500 grams).

Type of enteral feeds (predominantly or exclusively human milk, predominantly or exclusively formula feeds).

Dose of zinc supplementation (≤ 3 mg/kg/d, > 3 mg/kg/d).

Duration of zinc supplementation (≤ four weeks, > four weeks).

Additional micronutrient supplementation (zinc preparation alone, zinc combined with other micronutrients or vitamins).

Sensitivity analysis

We explored methodological heterogeneity by performing sensitivity analyses (if sufficient data were available). We performed sensitivity analyses by excluding trials of lower quality when we judged them to be at high risk of bias, to assess effects of bias on the meta‐analysis. We defined low quality as lack of any of the following: allocation concealment, adequate randomisation, blinding of treatment, or > 20% loss to follow‐up.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes:

-

All‐cause mortality:

Before hospital discharge (latest time reported at or after 36 weeks' postmenstrual age);

Between hospital discharge and neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term).

-

Neurodevelopmental disability at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term), defined as a neurological abnormality including any of the following:

Cerebral palsy on clinical examination;

Developmental delay > 2 SDs below the population mean on a standardised test of development (Vohr 2004);

Blindness (visual acuity < 6/60);

Deafness (any hearing impairment requiring amplification).

-

BPD, according to NICHD criteria, defined as oxygen requirement > 21% at 28 days of life and:

breathing room air (mild BPD);

oxygen requirement from 22% to 29% (moderate BPD); or

oxygen requirement > 30% and/or positive pressure (severe BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (for infants born at < 32 weeks' gestation) or at 56 days of life or discharge, whichever was later (for infants born at ≥ 32 weeks' gestation) (Jobe 2001).

ROP (any stage and stage III or IV);

Bacterial sepsis (episodes proven by means of positive blood culture);

NEC (any stage and stage 2 or greater);

Change in growth between start and end of intervention, from discharge to time of neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months of age (post‐term) (absolute growth or change in z‐score for weight, length, and head circumference, where z‐score was defined as deviation of an observed value for an individual from the median value of the reference population, divided by the SD of the reference population) (WHO 1995).

Two authors (ES, KE) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty, but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create Table 1 to report the certainty of the evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence as one of four grades:

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect;

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate;

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Description of studies

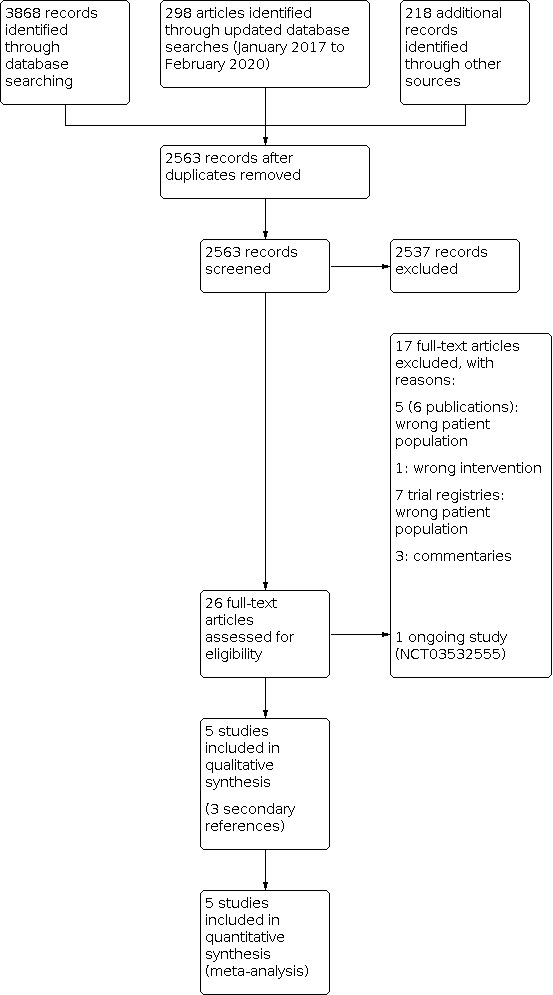

From the initial search of all databases and trial registries after the approval of the review protocol and an updated search three years later, we retrieved 4384 records. After de‐duplication, 2563 unique records remained. Of these, we excluded 2537 as irrelevant through screening of titles and abstracts. We assessed 26 studies as full texts and excluded a further 17 from eligibility. This left five trials to be included in the quantitative analysis. There was one ongoing study (NCT03532555; see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Results of the search

See Figure 1 for the study selection process and Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies for further details on the studies we considered for inclusion in this review.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included five trials (482 infants) in this review (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a). Samples sizes ranged between 37 and 193. All trials were single‐centre studies, four of which took place in tertiary NICUs (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), and one in a special care nursery (Islam 2010). Three trials were conducted in high‐income countries: Spain (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), Canada (Friel 1993), and Italy (Terrin 2013a), and two trials in middle‐income countries: Bangladesh (Islam 2010), and India (Mathur 2015). Publication dates ranged from 1993 to 2015.

Participants

All five trials included preterm infants during their initial hospital admission. One trial did not recruit participants if they had been in hospital for over seven days (Terrin 2013a). All but one trial restricted participation to a specified range of birth weight: 1000 to 2500 grams (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), < 1500 grams (Friel 1993), 1000 to 2499 grams (Islam 2010), and 401 to 1500 grams (Terrin 2013a). Two trials only enrolled participants if their birth weight was appropriate for gestational age (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010). Four trials excluded those infants with major congenital malformations (Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a). Outside of congenital malformations, four trials stated a variety of clinical conditions as exclusion criteria: conditions likely to influence growth or neurodevelopment (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, hydrocephalus, liver dysfunction, severe intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) (Friel 1993), unstable vital signs (not further specified) (Islam 2010), or congenital or maternal infection, immunodeficiency, infection or NEC before enrolment, critically ill condition (defined as pH < 6.8 or hypoxia with persistent bradycardia > 1 hour) (Terrin 2013a). Two trials enrolled participants only if they were formula‐fed (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993), while in another trial, study participants received breast milk exclusively during the study period and were excluded if they were kept nil by mouth for longer than seven days (Mathur 2015).

Interventions

The types and doses of zinc supplements varied between trials: two trials added zinc in the form of zinc sulfate to standard infant formula (10 mg/L in Díaz‐Goméz 2003, 11 mg/L in Friel 1993), while two trials administered the zinc in a multivitamin preparation (as zinc gluconate in a dose of 2 mg/kg/day in Islam 2010, 10 mg/day of zinc sulfate in Terrin 2013a). One trial administered zinc as separate supplements in the form of zinc gluconate (2 mg/kg/day in Mathur 2015). In two trials, copper sulfate was added in order to counteract potential inhibition of copper absorption through the zinc supplements (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993). Two trials specifically listed which other supplements the study participants were receiving (outside the zinc‐containing multivitamin preparations in Islam 2010 and Terrin 2013a): iron (Islam 2010; Mathur 2015), calcium, vitamin D, a multivitamin product, and vitamin E (Mathur 2015). Only one trial specified intravenous doses of zinc in case the study participants were receiving parenteral nutrition (10 mg/day in Terrin 2013a).

The intervention started at various time points and continued for different amounts of time: from 36 postconceptual weeks to six months corrected (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), from one month prior to hospital discharge to five months after discharge (Friel 1993), from between seven to 21 days of age for six weeks (Islam 2010), from the first week of life to the age of three months corrected (Mathur 2015), from day seven of life to hospital discharge or 42 weeks' postconceptual age (Terrin 2013a).

During the hospital admission, zinc supplements were administered by hospital staff in three trials (Friel 1993; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), and by parents or carers in one (Islam 2010). Where the intervention was continued after hospital discharge, zinc was administered by parents or carers in two trials (Friel 1993; Mathur 2015). One trial did not specify who was administering the zinc supplements either during hospital admission or after discharge, but stated that the supplements were added during the formula manufacturing process (Díaz‐Goméz 2003).

Comparators

Two trials added placebo to either standard formula (Friel 1993), or a multivitamin product (Terrin 2013a). The three other trials did not add zinc to the formula (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), multivitamin preparation (Islam 2010) or, where the intervention consisted of a separate zinc supplement, did not give the supplement (Mathur 2015). The two trials with added copper to the intervention, did not give the copper in the comparator groups (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993). Other supplements were given at the same dose and for the same length of time to the comparator group (Islam 2010; Mathur 2015).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Three trials reported in‐hospital mortality before discharge (Friel 1993; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), and one reported deaths after discharge (Mathur 2015). No trial reported neurodevelopmental disability of any kind at 18 to 24 months of age, however, two trials reported neurological development at three, six, nine and 12 months corrected age (Friel 1993), or 40 weeks' postmenstrual age and three months corrected (Mathur 2015). This study also included hearing outcomes at these latter time points.

Secondary outcomes

Only one trial reported the prematurity‐related morbidities of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, ROP and NEC (Terrin 2013a). Two trials reported bacterial sepsis (Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a). All five included trials reported on weight gain, four trials between the start and end of the intervention (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), and two at the last follow‐up (Friel 1993; Islam 2010). Four trials reported the full set of growth parameters (weight gain, linear growth, increase in head circumference) (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015). Four trials reported changes in anthropometry in absolute figures (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), while one trial reported changes in z‐scores for weight, length and head circumference (Friel 1993).

Additional outcomes

Three trials reported differences in blood zinc levels before and after the intervention (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010). No trial reported prevalence of skin eruptions or dermatitis and differences in blood iron levels. Two trials reported differences in copper blood level (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993). Two studies prespecified vomiting as adverse effects of the intervention and reported it in the results (Islam 2010; Mathur 2015), while Terrin 2013a only reported vomiting as a result without having prespecified it as an adverse outcome in the methods. Two studies reported that they did not observe adverse effects without having specified, either in the methods or results, which signs and symptoms would classify as such.

A variety of other outcomes were reported in the studies which are not part of this systematic review (for details see Characteristics of included studies).

Excluded studies

After full‐text review, we excluded 16 studies for the following reasons:

five studies (six publications) because they either enrolled term infants or the intervention was not started in the inpatient setting of a NICU or special care nursery or similar setting (Aminisani 2011; El‐Farghali 2015; Jimenez 2007; Lira 1998; Ram Kumar 2012);

one study because it was not an interventional trial (Shaikhkhalil 2013);

seven studies because they were trial registry entries and all of them enrolled the wrong patient population (CTRI/2010/091/001061; CTRI/2017/08/009544; ISRCTN35833344; ISRCTN85633178; NCT00272142; NCT00495690; NCT04050488);

three studies because they were commentaries rather than trials (Gibson 2000; Pittler 2001; Sazawal 2010).

See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 for a summary of risk of bias in included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All of the five included trials described adequate methods of random sequence generation, and none of them had significant baseline differences between the intervention and the control or placebo group (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a).

All included trials described adequate allocation concealment methods (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), using appropriate techniques to implement the sequence and preventing foreknowledge of the intervention assignment.

Blinding

We judged performance bias to be low, in three trials, as families of the patients and personnel administering the intervention or control/placebo were unaware of the allocation (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Terrin 2013a). We had some concerns over performance bias in two studies (Islam 2010; Mathur 2015), where the families of patients and personnel were aware of the study allocation; only one of the trials mentioned that the adherence to the intervention was monitored (Mathur 2015). In only one trial did we judge detection bias to be low risk, where outcome assessors were masked (Terrin 2013a). Three studies did not mention if outcome assessors were aware of study allocation (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010), and one trial was at high risk for detection bias because outcome assessors were aware of the intervention and assessment could likely have been influenced by this knowledge (Mathur 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged four trials as having low risk for attrition bias (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a). We judged one study to be at high risk, where the missingness of the outcome for participants lost to follow‐up was likely to be influenced by the true outcome value (Friel 1993).

Selective reporting

For all five included trials, we judged the reporting bias to be unclear. This was because none of the five included studies had published a trial protocol with prespecified analysis (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a).

Other potential sources of bias

One trial conducted a per protocol analysis (Mathur 2015), while another did not mention whether they performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis or per protocol analysis (Islam 2010).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Mortality (analysis 1.1)

Meta‐analysis of the data for three trials (345 infants) (Friel 1993; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a) showed that zinc supplementation may decrease mortality (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.97). We judged heterogeneity to be low (I2 = 44%; Analysis 1.1). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'low' using the GRADE method; we downgraded one level each for risk of bias and imprecision of the effect estimates. In the separate meta‐analysis of the data for in‐hospital (345 infants), and post‐discharge mortality (100 infants), the intervention probably made little or no difference (in‐hospital mortality: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.09, I2 = 60% demonstrating moderate heterogeneity; post‐discharge mortality: RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.16)

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 1: Mortality

Neurodevelopmental outcome

None of the included trials reported neurodevelopmental outcome at 18 to 24 months. Friel 1993 assessed development by Griffith Mental Developmental Scales at three, six, nine and 12 months corrected age. They found similar total scores for both the intervention and control groups at each assessment age, but significantly higher scores for motor development in the intervention group. Mathur 2015 examined neurodevelopment using the Amiel‐Tison method at 40 weeks' postmenstrual age and at three months corrected, and reported lower incidence of hyperexcitability and brisk tendon reflexes in the intervention group at both ages of assessment. This study reported no differences in a variety of other neurodevelopmental test items (visual and ocular signs, hearing abnormality, muscle tone, motor activity, involuntary movements, dystonia, cutaneous reflex, primitive reflex and asymmetric tonic neck reflex).

Secondary outcomes

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

One trial (Terrin 2013a, 193 infants), reported data where zinc supplementation may have little or no effect on bronchopulmonary dysplasia (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.40; Analysis 1.2). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'low' using the GRADE method; we downgraded two levels for imprecision of the effect estimates.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 2: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Retinopathy of prematurity

One trial (Terrin 2013a, 193 infants), reported data where zinc supplementation may have little or no effect on retinopathy of prematurity (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.70; Analysis 1.3). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'low' using the GRADE method, we downgraded two levels for the imprecision of the effect estimates.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 3: Retinopathy of prematurity

Bacterial sepsis

Zinc supplementation in two trials (293 infants) (Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a) probably makes little to no difference to bacterial sepsis (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.04; Analysis 1.4). We judged heterogeneity as low (I 2 = 1%). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'moderate' using the GRADE method; we downgraded for imprecision of the effect estimates.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 4: Bacterial sepsis

Necrotising enterocolitis

One trial (Terrin 2013a, 193 infants), reported data where zinc supplementation may have little or no effect on necrotizing enterocolitis (RR 0.08, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.33; Analysis 1.5). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'low' using the GRADE method; we downgraded two levels for imprecision of the effect estimates.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 5: Necrotising enterocolitis

Growth

Weight gain

Meta‐analysis of data from all five trials (481 infants) (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a), showed that zinc supplementation probably improves weight gain (SMD 0.46, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.64; Analysis 1.6). We judged heterogeneity to be low in this analysis (I2 = 0%). We assessed the certainty of evidences as 'moderate' using the GRADE method; we downgraded one level for risk of bias. No trial examined weight gain between hospital discharge and neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months post‐term.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 6: Weight gain

One of the five trials reported weight gain in z‐scores (Friel 1993), while the other four reported absolute weight differences in grams. To facilitate the assessment of the clinical relevance of the difference in weight gain, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding Friel 1993 and found the effect estimates only marginally different. Consequently, meta‐analysis of the four trials providing absolute metric measurements (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a) estimated the mean difference of weight gain as 287 grams (95% CI 176 to 399).

Linear growth

Meta‐analysis of data from four trials (289 infants) (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015), showed that zinc supplementation may slightly improve linear growth (SMD 0.75, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.14; Analysis 1.7). We judged heterogeneity to be moderate (I2 = 59%, p=0.06 for Chi2). We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding the trial with the lowest quality (Mathur 2015 for detection bias (Figure 2)), which reduced the heterogeneity to low, suggesting an effect of bias on the meta‐analysis. We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'low' using GRADE methods; we downgraded one level each for risk of bias and for inconsistencies in effect estimates. No trial examined the length gain between hospital discharge and neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months post‐term.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 7: Linear growth

One of the four trials reported linear growth in z‐scores (Friel 1993), while the other four reported absolute difference in length in centimetres. To facilitate the assessment of the clinical relevance of the difference in linear weight, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding Friel 1993 and found the effect estimates only marginally different. Consequently, meta‐analysis of the three trials providing absolute metric measurements (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015) estimated the mean difference of linear growth as 1.67 cm (95% CI 0.96 to 2.88).

Head growth

In the meta‐analysis of data from four trials (289 infants) (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015), zinc supplementation probably had little to no effect on head growth (SMD 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.44; Analysis 1.8). We judged heterogeneity to be low in this analysis (I2 = 0%). We assessed the certainty of evidence as 'moderate' using the GRADE methods; we downgraded one level for risk of bias. No trial examined head growth between hospital discharge and neurodevelopmental follow‐up at 18 to 24 months post‐term.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 8: Head growth

In analogy to the outcomes of weight gain and linear growth, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding Friel 1993 (the only trial reporting growth rates in changes of z‐scores) and found the effect estimates only marginally different. Consequently, meta‐analysis of the three trials providing absolute metric measurements (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015) estimated the mean difference of head circumference as 0.35 cm (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.71).

Additional outcomes

Three trials (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010), reported blood zinc levels in a total of 189 infants. Meta‐analysis found a significantly higher blood zinc level at the end of the intervention in the intervention group (mean difference (MD) 23.7 µg/dL higher, 95% CI 17.73 to 29.7; Analysis 1.9). Only one trial (Díaz‐Goméz 2003), reported numerical data on differences in blood copper status and found that the intervention group had significantly lower copper levels at the end of the intervention (MD ‐45.0 µg/dL, 95% CI ‐69.94 to ‐20.06; Analysis 1.10). One trial reported no significant difference in blood copper levels at any sampling time between the two groups, but did not provide numerical data (Friel 1993). None of the trials reported blood iron status.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 9: Difference in blood zinc level [µg/dL]

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Enteral zinc supplementation vs no zinc supplementation, Outcome 10: Difference in blood copper level [µg/dL]

None of the trials reported on skin eruptions or dermatitis as clinical signs of zinc deficiency at any time before or during the intervention. Three trials reported that no vomiting was observed as a potential adverse effect of enteral zinc supplementation (Islam 2010; Mathur 2015; Terrin 2013a); two trials reported that they did not observe adverse effects without specifying which signs and symptoms would classify as such (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Terrin 2013a).

Subgroup analysis

Very preterm infants (< 28 weeks' gestation)

None of the included trials provided data specifically per gestational age or data for only the group of infants born at < 28 weeks' gestation.

Very low birth weight (< 1500 grams birthweight)

Meta‐analysis of the two studies restricting the recruitment to very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (Friel 1993; Terrin 2013a), showed pooled effects consistent with the overall meta‐analysis for mortality, bacterial sepsis, weight gain, linear growth and head growth (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8). The data from the small number of studies and events as well as large confidence intervals may be insufficient to determine an effect in the subgroups. The only study reporting the secondary outcomes bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity and necrotising enterocolitis only recruited VLBW infants, therefore the main analysis and subgroup analysis were identical (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.5).

Types of enteral feeds (breast milk versus formula)

Participants in Mathur 2015 were fed only breast milk, while participants in Díaz‐Goméz 2003 and Friel 1993 were fed only infant formula, and no data on milk type was provided in the other included studies. The subgroup analysis for type of feeds lacked precision and was of limited informative value because it contained only one or two studies each. Type of enteral feeds appear to have little to no influence on mortality or bacterial sepsis in the intervention group compared to control group (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.4). The two studies which enrolled only infants on an exclusive diet of infant formula milk observed slightly improved weight gain and linear growth, but little to no effect on head growth in the intervention groups; whereas in the study with exclusively breast milk fed infants, zinc supplementation may have little to no effect on growth outcomes (Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8).

Dose of zinc supplementation

Only Terrin 2013a used zinc supplements at high doses (> 3 mg/kg/day), while the four remaining included studies used lower doses (< 3 mg/kg/day) (Díaz‐Goméz 2003; Friel 1993; Islam 2010; Mathur 2015). Since the subgroup analysis for mortality and the secondary outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, bacterial sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity and necrotizing enterocolitis contained only one or two studies, the data may be insufficient to determine an effect in the subgroups. Low‐dose zinc supplementation may have little to no effect on mortality; the single study assessing high‐dose zinc supplementation observed a slight improvement in mortality (Analysis 1.1). Subgroup analysis for high‐ and low‐dose zinc supplementation were consistent with the overall meta‐analysis for bacterial sepsis (Analysis 1.4), but only contained one study each. The only study reporting the secondary outcomes bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity and necrotising enterocolitis used a zinc dose of > 3 mg/kg/day in the intervention group, therefore, the main analysis and subgroup analysis were identical (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.5). Weight gain was consistent with the overall meta‐analysis for both high‐ and low‐dose supplementation (Analysis 1.6). All trials in the meta‐analysis for linear growth and head growth supplemented at the lower dose of < 3 mg/kg/day, therefore, results of this subgroup were consistent with the overall meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8).

Duration of treatment

All studies included in this review supplemented zinc for more than four weeks.

Other micronutrient and/or vitamin supplementation

All studies included in this review supplemented zinc in combination with other micronutrients and vitamins.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Evidence from three of the five included RCTs showed that zinc supplementation in preterm infants may result in a modest reduction in mortality (low‐certainty of evidence). The studies included into the meta‐analysis did not provide data for the other primary outcome of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18 to 24 months. For the secondary outcomes of major neonatal morbidities (bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, bacterial sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis), only few data were available and these showed that zinc supplementation may make little or no difference (moderate‐ to low‐certainty of evidence). Data from four trials indicated that zinc supplementation probably improves weight gain (moderate‐certainty of evidence) and linear growth (low‐certainty of evidence), but may make little to no difference to head growth (moderate‐certainty of evidence).

Only one or two studies could be analysed in each of the prespecified subgroup analyses. The data from the small number of studies and low event rates as well as large confidence intervals may be insufficient to determine a true effect in the subgroups. Subgroup analysis for very low (< 28 weeks) versus higher (> 28 weeks) gestational age, duration of zinc supplementation of less or more than four weeks, and zinc supplementation with or without other micronutrients and/or vitamins was not performed due to lack of data for these respective subgroups or because all included studies had enrolled the same subgroup. Zinc supplementation in VLBW infants showed that it may reduce mortality and probably improves weight gain slightly, consistent with the effect of the overall meta‐analysis. High‐dose zinc supplementation (> 3 mg/kg/day) may result in a slight reduction of mortality, while low dose (< 3 mg/kg/day) may cause little to no difference. The effect on weight gain, linear growth and head growth was similar in high‐ versus low‐dose zinc supplementation, where the intervention may slightly improve weight and length, but may have little to no effect on head circumference. Zinc supplementation in exclusively formula‐fed infants in a single study may improve weight gain and linear growth slightly, but may have little or no effect on all other primary or secondary outcomes, as did zinc supplementation for infants on an exclusive diet of breast milk.

This review found a robust increase in blood zinc level. There were no reports of harm from zinc supplementation.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Meta‐analysis indicated that zinc supplementation started during the initial hospital admission of preterm infants may result in lower mortality and improved weight gain and linear growth. However, caution should be applied in the interpretation of these findings, as the certainty of evidence is moderate to low. The typical effect size on growth rates was small, and the long‐term impact on growth was unclear because none of the included studies reported growth later than six months corrected age. Similarly, as a major limitation, there were no data available on long‐term neurological outcome between 18 to 24 months or later. Based on the growing evidence that improved growth positively affects neurodevelopment, the question remains unanswered whether zinc supplementation could influence neurodevelopment directly or possibly via improved growth (and, if the latter was the case, whether the effect of zinc supplementation on weight gain or linear growth was more important). Further, in this context, the significance that enteral zinc supplementation may have little or no effect on head growth remains unclear. The data on common prematurity‐related morbidities such as BPD, ROP, bacterial sepsis and NEC were very limited, for the majority were only assessed in a single trial and therefore were of moderate‐ to low‐certainty. Potential adverse effects were not looked for or reported consistently, with only two trials each prespecifying and documenting blood copper levels and vomiting.

The included trials were undertaken in a variety of healthcare settings, in high‐ and middle‐income countries, with one trial completing the intervention during the initial admission to the NICU versus other trials starting the intervention shortly prior to discharge and continued in the community thereafter. While this might be an explanation for the overall modest impact of the intervention, it could influence the clinical decision for zinc supplementation as a useful intervention in a resource‐limited setting (where most preterm and low birth weight infants are cared for globally).

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of evidence as low or moderate for all outcomes (Table 1), mostly on the basis of serious or very serious concerns over imprecision of the effect estimates (i.e. confidence intervals consistent with very small to very large effect and/or only one study included in the outcome analysis with small sample size and low event rate). Generally, the five included trials were small to very small, but of reasonably good methodological quality. One trial had major risk of bias in the blinding of the outcome assessment (Mathur 2015), which could be relevant for the neurological assessment performed in this particular study, but not likely a major source of bias in the assessment of growth and mortality. One study was assessed as having high attrition bias where only infants without physical disabilities were included in neurological outcome measures (Friel 1993). However, these results were not part of the primary and secondary outcomes of the meta‐analysis in this review. Removal of these two trials in sensitivity analysis decreased the statistical heterogeneity and increased the size of treatment effect in all the meta‐analyses where either of these two studies were included, indicating an influence of the quality of evidence on pooled effects.

Potential biases in the review process

We made every effort to minimise error in data collection. We contacted study authors to obtain additional relevant data for inclusion into the analysis. One of the concerns with the review process was the possibility of reporting or publication bias, despite the comprehensive search strategy. We attempted to minimise this by screening the reference lists of the included studies and related reviews. The meta‐analysis did not contain sufficient studies to explore symmetry of funnel plots. Not all predefined analysis could be reported as the included studies did not allow for all subgroup analyses.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to address the effect of zinc supplementation in hospitalised preterm infants. A non‐Cochrane systematic review of zinc supplementation in low birth weight breastfed infants in the community only included three small studies and did not find an effect of the intervention on growth, all‐case mortality or infectious diseases (Gulani 2011). Other Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews on zinc supplementation in children outside the neonatal age bracket agreed with the finding of reduced mortality (Mayo‐Wilson 2014a) and improved growth outcomes (Brown 1998; Brown 2002; Imdad 2011; Liu 2018; Ramakrishnan 2009), while others found no change in mortality (Patel 2011), or only in certain subgroups (Mayo‐Wilson 2014b) and no positive effect on growth (Gera 2019; Stammers 2015). Potential reasons for the disagreements with these previous reviews might be the variety of included age groups included (preterm versus term infants versus older children), differences in the socioeconomic setting (low‐ and middle‐income versus high‐income countries) and background risk of the study participants. Our review could not support the observations by Sandstörm 1983 that better reabsorption of zinc from human milk (compared to infant formula) potentially led to larger effects of the intervention when preterm infants were on an exclusive human milk diet, since our subgroup analysis had only one study with exclusive human milk use. Similar to our review, Mayo‐Wilson 2014b found limited evidence for adverse effects from zinc supplementation and concurred that the potential benefits outweighed the risk of harm.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The available data from RCTs suggest that enteral zinc supplementation in preterm infants may reduce mortality, slightly increases weight gain and linear growth, but may have little to no effect on head growth and common prematurity‐associated morbidities. There are a lack of data on any long‐term effects on growth or neurodevelopment. The findings should be interpreted with caution, as the total number of infants studied in the five included studies was small (482 infants), and the data that could be extracted from published studies were limited. The reported adverse effects did not appear clinically relevant, potentially making zinc supplementation a relatively safe intervention. However, only a minority of the included studies actively looked for side effects as a prespecified outcome.

Implications for research.

Zinc supplementation in preterm infants has the potential to affect important outcomes in preterm infants and merits further research, in particular, in the setting of the typically long and complicated admissions of extremely low gestational age infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. Larger scale trials could help to consolidate the positive findings on growth and mortality and further explore the effect of zinc on common morbidities in this patient group, such as BPD, bacterial sepsis, NEC and ROP. There is reason to speculate that a favourable effect of zinc on growth could positively impact long‐term neurodevelopment, since poor weight gain presents an important and possibly independent risk factor for worse neurodevelopment (Ehrenkranz 2006). One trial is currently recruiting ELBW infants at high risk of developing BPD and randomising to open‐label zinc supplements versus standard care (NCT03532555; see Characteristics of ongoing studies), with a primary outcome of growth rates and a secondary outcome of BPD. While important for a subset of particularly vulnerable preterm infants, this relatively small single‐centre trial is not mapped to contribute to the current body of evidence of zinc as a universal trace element supplement for all infants under a specific gestational age, nor add information on developmental outcomes. The ideal randomised controlled trial would attempt to recruit all infants below a certain gestational age, mask the intervention to caregivers and assessors and be powered sufficiently to detect clinically relevant short‐term outcomes as well as long‐term neurodevelopment and growth beyond the first year of life. A robust study design would allow an assessment of a possible association between enteral zinc supplementation and neurodevelopment, either as a direct effect or via improvement of growth. Safety concerns from adverse effects would need to be taken into account, particularly in view of a possible dose‐effect relationship.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 November 2021 | Amended | Labels were corrected for Figures 1.6 and 1.7 to show that Zinc was favored vs control |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 9, 2017 Review first published: Issue 3, 2021

Acknowledgements

The methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Neonatal.

We would like to thank Cochrane Neonatal: Colleen Ovelman, Managing Editor, Jane Cracknell, Assistant Managing Editor, Roger Soll, Co‐coordinating editor, and Bill McGuire, Co‐coordinating Editor, who provided editorial and administrative support. We would also like to thank Carol Friesen, Information Specialist, who designed and ran the literature searches, and Colleen Ovelman, Managing Editor with Cochrane Neonatal, who peer reviewed the Ovid MEDLINE search strategy.

Jacqueline Ho and Tanis Fenton have peer reviewed and offered feedback for this review.

We would like to thank all primary investigators who provided additional information about trial methods and outcomes.

Appendices

Appendix 1. 2017 Search methods

PubMed:(zinc AND (infant, newborn[MeSH] OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR premature OR low birth weight OR VLBW OR LBW or infan* or neonat*) AND (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]))

Embase: zinc AND (infant, newborn or newborn or neonate or neonatal or premature or very low birth weight or low birth weight or VLBW or LBW or Newborn or infan* or neonat*) AND (human not animal) AND (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial or randomized or placebo or clinical trials as topic or randomly or trial or clinical trial)

CINAHL: zinc AND (infant, newborn OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR premature OR low birth weight OR VLBW OR LBW or Newborn or infan* or neonat*) AND (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial)

Cochrane Library: zinc AND (infant or newborn or neonate or neonatal or premature or preterm or very low birth weight or low birth weight or VLBW or LBW)

Appendix 2. 2020 Search methods

The RCT filters have been created using Cochrane's highly sensitive search strategies for identifying randomised trials (Higgins 2020). The neonatal filters were created and tested by the Cochrane Neonatal Information Specialist.

CENTRAL via CRS Web

Date ranges: 01 January 2017 to 20 February 2020 Terms: 1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Zinc EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET 2 zinc AND CENTRAL:TARGET 3 #1 OR #2 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Infant, Newborn EXPLODE ALL AND CENTRAL:TARGET 5 infant or infants or infant's or "infant s" or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW or ELBW or NICU AND CENTRAL:TARGET 6 #5 OR #4 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 7 #3 AND #6 AND CENTRAL:TARGET 8 2017 TO 2020:YR AND CENTRAL:TARGET 9 #8 AND #7 AND CENTRAL:TARGET

MEDLINE via Ovid:

Date ranges: 01 January 2017 to 20 February 2020 Terms: 1. exp Zinc/ 2. zinc.mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. exp infant, newborn/ 5. (newborn* or new born or new borns or newly born or baby* or babies or premature or prematurity or preterm or pre term or low birth weight or low birthweight or VLBW or LBW or infant or infants or 'infant s' or infant's or infantile or infancy or neonat*).ti,ab. 6. 4 or 5 7. randomized controlled trial.pt. 8. controlled clinical trial.pt. 9. randomized.ab. 10. placebo.ab. 11. drug therapy.fs. 12. randomly.ab. 13. trial.ab. 14. groups.ab. 15. or/7‐14 16. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 17. 15 not 16 18. 6 and 17 19. randomi?ed.ti,ab. 20. randomly.ti,ab. 21. trial.ti,ab. 22. groups.ti,ab. 23. ((single or doubl* or tripl* or treb*) and (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab. 24. placebo*.ti,ab. 25. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 26. 5 and 25 27. limit 26 to yr="2018 ‐Current" 28. 18 or 27 29. 3 and 28 30. limit 29 to yr="2017 ‐Current"

CINAHL via EBSCOhost:

Date ranges: 01 January 2017 to 20 February 2020 Terms: (zinc) AND (infant or infants or infant’s or infantile or infancy or newborn* or "new born" or "new borns" or "newly born" or neonat* or baby* or babies or premature or prematures or prematurity or preterm or preterms or "pre term" or premies or "low birth weight" or "low birthweight" or VLBW or LBW) AND (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR randomised OR placebo OR clinical trials as topic OR randomly OR trial OR PT clinical trial) Limiters ‐ Published Date: 20170101‐20191231

ISRCTN:

Date ranges: 2017 to 2020 Terms: Interventions: Zinc AND Participant age range: Neonate Condition: Infant* OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR neonates OR preterm OR low birth weight OR low birthweight OR LBW AND Interventions: Zinc Text search: (infant* OR newborn OR neonate OR neonatal OR neonates OR preterm OR low birth weight OR low birthweight OR LBW) AND zinc

Appendix 3. Risk of bias tool

Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

For each included study, we categorised the method used to generate the allocation sequence as:

low risk (any truly random process e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk (any non‐random process e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). Was allocation adequately concealed?

For each included study, we categorised the method used to conceal the allocation sequence as:

low risk (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth); or

unclear risk.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?

For each included study, we categorised the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or class of outcomes. We categorised the methods as:

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for participants;

low risk, high risk or unclear risk for personnel; or