Abstract

Background

Many people with chronic disease have more than one chronic condition, which is referred to as multimorbidity. The term comorbidity is also used but this is now taken to mean that there is a defined index condition with other linked conditions, for example diabetes and cardiovascular disease. It is also used when there are combinations of defined conditions that commonly co‐exist, for example diabetes and depression. While this is not a new phenomenon, there is greater recognition of its impact and the importance of improving outcomes for individuals affected. Research in the area to date has focused mainly on descriptive epidemiology and impact assessment. There has been limited exploration of the effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of health‐service or patient‐oriented interventions designed to improve outcomes in people with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Multimorbidity was defined as two or more chronic conditions in the same individual.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and seven other databases to 28 September 2015. We also searched grey literature and consulted experts in the field for completed or ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

Two review authors independently screened and selected studies for inclusion. We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised clinical trials (NRCTs), controlled before‐after studies (CBAs), and interrupted time series analyses (ITS) evaluating interventions to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Multimorbidity was defined as two or more chronic conditions in the same individual. This includes studies where participants can have combinations of any condition or have combinations of pre‐specified common conditions (comorbidity), for example, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. The comparison was usual care as delivered in that setting.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies, evaluated study quality, and judged the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We conducted a meta‐analysis of the results where possible and carried out a narrative synthesis for the remainder of the results. We present the results in a 'Summary of findings' table and tabular format to show effect sizes across all outcome types.

Main results

We identified 17 RCTs examining a range of complex interventions for people with multimorbidity. Nine studies focused on defined comorbid conditions with an emphasis on depression, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The remaining studies focused on multimorbidity, generally in older people. In 11 studies, the predominant intervention element was a change to the organisation of care delivery, usually through case management or enhanced multidisciplinary team work. In six studies, the interventions were predominantly patient‐oriented, for example, educational or self‐management support‐type interventions delivered directly to participants. Overall our confidence in the results regarding the effectiveness of interventions ranged from low to high certainty. There was little or no difference in clinical outcomes (based on moderate certainty evidence). Mental health outcomes improved (based on high certainty evidence) and there were modest reductions in mean depression scores for the comorbidity studies that targeted participants with depression (standardized mean difference (SMD) −0.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.63 to −0.2). There was probably a small improvement in patient‐reported outcomes (moderate certainty evidence). The intervention may make little or no difference to health service use (low certainty evidence), may slightly improve medication adherence (low certainty evidence), probably slightly improves patient‐related health behaviours (moderate certainty evidence), and probably improves provider behaviour in terms of prescribing behaviour and quality of care (moderate certainty evidence). Cost data were limited.

Authors' conclusions

This review identifies the emerging evidence to support policy for the management of people with multimorbidity and common comorbidities in primary care and community settings. There are remaining uncertainties about the effectiveness of interventions for people with multimorbidity in general due to the relatively small number of RCTs conducted in this area to date, with mixed findings overall. It is possible that the findings may change with the inclusion of large ongoing well‐organised trials in future updates. The results suggest an improvement in health outcomes if interventions can be targeted at risk factors such as depression in people with co‐morbidity.

Plain language summary

Improving outcomes for people with multiple chronic conditions

Background

The World Health Organization defines chronic conditions as "health problems that require ongoing management over a period of years or decades". Many people with a chronic health problem or condition, have more than one chronic health condition, which is referred to as multimorbidity. This generally means that people could have any possible combination of health conditions but in some studies the combinations of conditions are pre‐specified to target common combinations such as diabetes and heart disease. We refer to these types of studies as comorbidity studies. Little is known about the effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity. This is an update of a previously published review.

Review question

This review aimed to identify and summarise the existing evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to improve clinical and mental health outcomes and patient‐reported outcomes including health‐related quality of life for people with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings.

Description of study characteristics

We searched the literature up to September 2015 and identified 17 generally well‐designed randomised controlled trials meeting the eligibility criteria. Nine of these studies focused on specific combinations of health conditions (comorbidity studies), for example diabetes and heart disease. The other eight studies included people with a broad range of conditions (multimorbidity studies) although they tended to focus on elderly people. The majority of studies examined interventions that involved changes to the organisation of care delivery although some studies had more patient‐focused interventions. All studies had governmental or charitable sources of funding.

Key results

Overall the results regarding the effectiveness of interventions were mixed. There were no clear positive improvements in clinical outcomes, health service use, medication adherence, patient‐related health behaviours, health professional behaviours or costs. There were modest improvements in mental health outcomes from seven studies that targeted people with depression. Results indicated that interventions may possibly improve functional outcomes in the studies that reported these outcomes. . Overall the results indicate that it is difficult to improve outcomes for people with multiple conditions. The review suggests that interventions that are designed to target specific risk factors (for example treatment for depression) may be more effective. There is a need for further studies on this topic, particularly involving people with multimorbidity in general across the age ranges.

Quality/certainty of the evidence

All of the included studies were randomised controlled trials. The overall quality of these studies was good though many studies did not fully report on all potential sources of bias. As definitions of multimorbidity vary among studies, the potential to reasonably combine study results and draw overall conclusions is limited. Overall, we judged that the certainty or confidence we can have in the results from this review is moderate but due to small numbers of studies and mixed results we acknowledge the uncertainty remaining and the potential that future studies could change our conclusions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Interventions aimed at improving outcomes for people with multimorbidity compared with usual care | |||

|

Participant or population: Adults with multimorbidity (two or more chronic conditions) Settings: Primary care and community settings Intervention: Any intervention designed to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity including professional‐, organisational‐ and patient‐oriented interventions Comparison: Usual care | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | Number of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Clinical outcomes | There is no clear effect on clinical outcomes with a range of standardised effect sizes from 0.01 to 0.78 with a minority having effect sizes > 0.5; interventions aimed at improving management of risk factors in comorbid conditions were more likely to have higher effect sizes. | 10 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate |

| Mental health outcomes | There are improved depression‐related outcomes in studies targeting comorbid conditions that include depression with a range of standardised effect sizes from 0.09 to 1.18 with 3 of 7 studies having moderate to large effect sizes (> 0.5) . Standardised mean difference of −0.41 (95% CI, −0.63 to −0.20) was calculated from combining data from 6 studies. | 9 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

| Patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) | There are mixed effects on PROMs with only half of studies that reported these outcomes showing any benefit with a range of standardised effect sizes from 0.03 to 0.84. Only 1 of 5 studies with data available data on self‐efficacy had a moderate effect size (>0.5), 1 of 6 had a moderate effect size for HRQoL, and effect sizes for other psychosocial outcomes were generally low. | 13 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate |

| Health Service Utilisation | There were no effects on health service utilisation and changes in visits were difficult to interpret as some interventions could lead to higher numbers of visits if previous unmet need was being addressed. There was no difference in admission‐related outcomes, though numbers of admissions in most of these studies were very small. | 5 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low |

| Medication use and adherence | There are mixed effects on medication use and adherence with half the studies reporting this outcome showing benefit. Proportions adherent to medication were higher in intervention participants with ranges in absolute difference of 10% to 40% but all studies with available data had small effect sizes. | 4 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low |

| Health‐related patient behaviours | Studies measuring this outcome reported a range of effects varying from an additional 18 minutes spent walking per week to an absolute difference in kcals expenditure per week of 2516 (no studies presented data that could be used to calculate effect sizes). | 7 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate |

| Provider behaviour | The majority of studies reporting provider behaviour indicated improved provider behaviour relating to care delivery; three studies reported a range of 15% to 40% in proportions of intervention providers improving behaviours such as appropriate referral. | 5 | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

We downgraded the evidence for effects on clinical and psychosocial outcomes to moderate due to lack of consistency of effect across studies and small effect sizes. We downgraded the evidence for effects on provider behaviour to moderate due to limited available data for calculation of standardised effect sizes (SES) and lack of clarity regarding the clinical importance of the results. We downgraded the evidence for effects on health service utilisation and medication use and adherence to low due to variation across studies and small effect sizes.

Background

Many people with chronic disease have more than one chronic condition, which is referred to as multimorbidity. While this is not a new phenomenon, there is greater recognition of its impact and the importance of improving outcomes for individuals affected. Research in the area to date has focused mainly on descriptive epidemiology and impact assessment (Fortin 2007). There has been limited exploration of the effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity.

Description of the condition

There has been increasing focus on the enormous personal and societal burden of ill‐health caused by chronic disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasised the importance of organising healthcare delivery systems to improve health outcomes and has stressed the importance of building integrated healthcare systems that can address chronic disease management (WHO 2002). This can be done by focusing on generic chronic care models, as has happened mainly in the United States of America (USA), or by developing national systems focusing on single chronic conditions as has happened with the National Service Frameworks in the UK (Lewis 2004; Satariano 2013). However, many people with chronic disease have more than one chronic condition, which is referred to as multimorbidity and formally defined as the co‐existence of two or more chronic conditions (Fortin 2005). While this is not a new phenomenon, there is greater recognition of its impact and the importance of improving outcomes for individuals affected (Fortin 2007; Smith 2007).

While the accepted term for people with multiple chronic conditions is now multimorbidity, the term comorbidity has been used interchangeably in the past. It is now accepted that comorbidity should be used when there is a specified index condition or where there are defined combinations of conditions (for example hypertension and cardiovascular disease) as opposed to multimorbidity where any condition could be included (Valderas 2011). Multimorbidity is the more general term and individuals with comorbidity also have multimorbidity but the reverse does not necessarily apply. For the purposes of this review when analysing the included studies, we looked at studies based on the intervention elements but we also considered differences between studies that specifically target comorbid conditions as opposed to those targeting general multimorbidity. This is because interventions in the comorbidity studies are designed to target the specific included conditions. These distinctions are important in the context of developing and evaluating effective interventions and considering their generalisability (Fortin 2013; Smith 2013).

Individuals with multimorbidity are more likely to die prematurely (Deeg 2002; Menotti 2001; Rochon 1996), be admitted to hospital (Bähler 2015; Condelius 2008; Payne 2013), and have longer hospital stays (Bähler 2015; Librero 1999). They have poorer quality of life (Brettschneider 2013), loss of physical functioning (Bayliss 2004; Fortin 2004; Fortin 2006b), and are more likely to suffer from psychological stress (Fortin 2006a; Gunn 2012). Medicines management is often complex, resulting in polypharmacy with its attendant risks of drug interactions and adverse drug events (Duerden 2013; Gandhi 2003; Guthrie 2011). For patients, in addition to understanding and managing their conditions and drug regimes, they must also attend multiple appointments with different healthcare providers and adhere to lifestyle recommendations (Gallacher 2011; Townsend 2006).

Prevalence studies of multimorbidity have been carried out in different countries indicating that, particularly in those over 60 years, the majority of people attending family primary care services had more than one chronic condition (Fortin 2005; Fortin 2006c; van den Akker 1998; Wolff 2002). A subgroup of these service users have a debilitating combination of conditions that have a high impact on their own lives but also on their utilisation of health services and related costs (Hoffman 1996; Marengoni 2011; Parmelee 1995; Smith 2008). This emerging concept may be referred to as 'complex multimorbidity' and has been defined as people with three or more chronic conditions involving three or more body systems (Harrison 2014). These individuals can pose management difficulties, resulting in frequent health care visits, frequent emergency hospital admissions, and repeated investigations with enormous cost both for the individuals and the healthcare system involved. A UK report has examined the costs associated with this group of people who are described as 'high impact users' on the basis of their frequent emergency admissions (Rowell 2006). Fragmentation of care is a significant problem for this group, resulting from the involvement of both primary care and multiple specialists who may not be communicating with each other effectively (Wallace 2015). Starfield found that people with a greater morbidity burden have a higher use of specialists even for conditions that are normally managed in primary care, and concludes that there is a need for a better understanding of the roles of generalists and specialists in managing these individuals (Starfield 2005)

Description of the intervention

Given the complexity of managing people with multiple chronic conditions, potential interventions are likely to be complex and multifaceted if they are to address the varied needs of these individuals. We anticipated that a variety of intervention types could work to improve outcomes for people with multimorbidity and could be included within the scope of this review. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) has developed a taxonomy that defines intervention types (EPOC 2002). We have used this taxonomy to define health service and patient‐oriented interventions that have been designed to improve outcomes of people or populations with more than one chronic condition.

1. Professional interventions: for example, education designed to change the behaviour of clinicians. Such interventions may work by altering professionals' awareness of multimorbidity or providing training or education designed to equip clinicians with skills in managing these individuals, thus improving their healthcare delivery.

2. Financial interventions: for example, financial incentives to providers to reach treatment targets. These interventions might work by incentivising health service delivery and providing resources to extend consultation length for people with multimorbidity.

3. Organisational interventions: these can be further divided into organisational changes delivered through practitioners or directly to patients. For example, any changes to care delivery such as case management or the addition of different healthcare workers such as a pharmacist to the healthcare team. These interventions may work by changing care delivery to match the needs of people with multimorbidity across a range of areas such as coordination of care, medicines management, or use of other health professionals such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists to address needs relating to physical and social functioning.

4. Patient‐oriented interventions: this would include any intervention directed primarily at individuals, for example, education or support for self management. These interventions might work by improving self management, thus enabling people to manage their conditions more effectively and to seek appropriate health care.

5. Regulatory interventions: for example, changes to local or national regulations designed to alter care delivery in order to improve outcomes. Such interventions might work by introducing regulatory changes that facilitate and enable the funding of care that is directed towards those with complex health needs. An example could be the introduction of free primary care for people with multimorbidity on the basis that preventive care might prevent subsequent more costly hospital admissions. While we did not find these types of interventions, we believe they could exist and would fall within the scope of this review for future updates.

How the intervention might work

We anticipated that organisational‐type interventions might predominate. We were aware that there has been a focus on case management, based mainly in health maintenance organisations in the USA (Zwarenstein 2000). Case management is defined as the explicit allocation of co‐ordination of tasks to an appointed individual or group and it is postulated that the function of co‐ordination is so important and specialised that responsibility for carrying it out needs to be explicitly allocated (Zwarenstein 2000). Our review included studies where case management was employed but only if it was specifically directed towards individuals identified as having multimorbidity.

The implementation of the Family Medicine Groups in the province of Québec, Canada, is another example of an organisational intervention as it involved new forms of shared responsibilities between physicians and nurses (MSSS 2001). Another example in the United Kingdom (UK) is the community matrons programme, which is being delivered through primary care trusts and is based on nurse‐provided case management for people with complex care needs including those with multimorbidity (London DOH 2005). It is similar to previous programmes delivered through social services in the 1990s and there have been concerns expressed as to the feasibility of achieving the programme targets without real integration of primary and specialist services (Murphy 2004).

The differences outlined earlier between multimorbidity in general and comorbidity where there are defined combinations of conditions also influences how interventions are designed. Interventions targeting specified comorbid conditions can be designed to address the specific challenges for people with those conditions. For example, an intervention that targets people with diabetes and depression will combine elements of diabetes‐focused care with psychotherapy or escalation of antidepressant medication, or both interventions, so as to address both conditions. Interventions for people with multimorbidity in general cannot have a disease focus as there are no pre‐specified conditions so the interventions might address improved coordination of care, improved medicines management or specific functional difficulties experienced by patients.

Since this review was originally planned in 2007, there has been widespread recognition of the need to address the challenge of multimorbidity across health systems with a series of articles in international medical journals highlighting the challenges involved. Two very useful resources highlighting the challenges of multimorbidity and collating research in the area are: i) the BMJ multimorbidity special collections (BMJ Multimorbidity collection) and ii) the International Research Community on Multimorbidity archive IRCMO at the University of Sherbrooke, Quèbec, Canada (IRCMO). The BMJ series includes a series of editorials, original research studies and a clinical review with a multimorbidity focus. IRCMO provides a platform for any researcher interested in multimorbidity to contribute to a regularly updated blog and also compiles a list of multimorbidity related publications.

Why it is important to do this review

This review was originally undertaken based on the clear recognition of the need for integrated care for people with multiple conditions who have complex care needs (Stange 2005). The evidence base for managing chronic conditions is based largely on trials of interventions for single conditions and individuals with multimorbidity are often excluded from such studies (Fortin 2006c; Starfield 2001; Wyatt 2014Zulman 2011). The inadequacy of existing clinical guidelines to support clinicians in managing people with multimorbidity has been highlighted as a significant issue in delivering care (Dumbreck 2015; Wyatt 2014). Clinical guideline developers have attempted to address this issue with the consideration of certain combinations of commonly co‐occurring conditions, for example, diabetes and depression (NICE 2009). However good quality evidence is essential to inform this clinical area and in recent years focus has shifted to intervention development and the need to reorientate clinical practice and healthcare systems for the people who use them most (Satariano 2013).

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of health‐service or patient‐oriented interventions designed to improve outcomes in people with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Multimorbidity was defined as two or more chronic conditions in the same individual.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised clinical trials (NRCTs), controlled before‐after studies (CBAs), and interrupted time series analyses (ITS), meeting EPOC quality criteria (EPOC 2013). We included NRCTs in the original protocol (Smith 2007b) as we anticipated that, given the challenges in undertaking multimorbidity research (Fortin 2007) and the likelihood that complex interventions would be tested, there would be relatively few RCTs and that non‐randomised designs might be used instead.

Types of participants

We included any people or populations with multimorbidity receiving care in a primary or community care setting. We adopted the most widely used definition of multimorbidity, that is, the co‐existence of multiple chronic diseases and medical conditions in the same individual, usually defined as two or more conditions (Fortin 2004; van den Akker 1998). We used the WHO definition of chronic disease, which is "health problems that require ongoing management over a period of years or decades" (WHO 2002). We included all studies that identified participants or sub‐groups of participants on the basis of multimorbidity, as defined by the study authors. In some studies, additional eligibility criteria were applied (for example, history of high service utilisation) in an effort to identify more vulnerable people who might benefit more from the intervention being studied.

We excluded studies where multimorbidity was assumed to be the norm on the basis of individuals' age as the interventions were not being targeted specifically at multimorbidity and its recognised challenges. This included studies where interventions were directed at communities of people based on location or age of participants in which participants could be presumed to have multimorbidity on the basis of their age or residence in a nursing home but interventions were not designed to specifically target multimorbidity.

Types of interventions

We included any type of intervention that was specifically directed towards a group of people defined as having multimorbidity. Only interventions based in primary care and community settings were included. Interventions included care delivered by family doctors, nurses, or other primary care professionals. Primary health care was defined as providing "integrated, easy to access, health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained and continuous relationship with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community" (Vaneslow 1995). However, not all countries have clearly‐defined primary care systems (Starfield 1998), so we included care delivered in community settings by individuals fulfilling the basic criteria for primary care, i.e. if they are available to treat all common conditions in all age groups and have an ongoing relationship with their patients. While some specialists may deliver components of primary care to their patients, practitioners were not included unless they fulfilled the definition of being available to treat all conditions and have an ongoing relationship with their patients.

Interventions were classified as 'simple' if they used one identifiable component or 'multifaceted' if they incorporated more than one feature.

We categorised interventions using the EPOC taxonomy presented in the Background section. Where interventions had multiple elements, we defined each element within the taxonomy and highlighted the predominant element of the intervention (see Table 2).

1. Multimorbidity intervention components.

| Author Year | Professional | Participant | Organisational | Effect of intervention on primary outcome | ||

| Case management or coordination of care | Reorganisation of care/team working | New team member | ||||

| Predominantly organisational | ||||||

| Barley 2014 | Nurse training | Participant information Prioritisation to create goals and health plan |

Case manager provided personalised care | Regular planned participant visits Weekly team meetings |

Nurse case manager | Pilot study and primary outcome was feasibility and deemed successful |

| Bogner 2008 | Individualised programme | Case manager | Regular planned participant visits | Improved blood pressure control and depression scores | ||

| Boult 2011 | Nurse training | Individual management plans Support for self‐management |

Guided care nurses coordinated care |

Guided care 'pods' consisting of nurse and PCP Monthly monitoring of participants |

No impact on healthcare utilisation | |

| Coventry 2015 | Practice team training | Personalised goals and participant workbooks |

Collaborative care using stepped care protocols Joint consultation between participant, psychologist and practice nurse |

Psychologist Supervision and input from team psychiatrist |

Modest reduction in depression scores | |

| Hogg 2009 | Individualised care plans |

Multidisciplinary team‐based management with home based assessment Medication review |

Pharmacist | Modest improvements in quality of chronic care delivery | ||

| Katon 2010 | Individualised management plans and targets Support for self‐management |

Team‐based care Stepped care treatment protocols Weekly team meeting |

Psychologist and psychiatrist supported depression care | Improvements in composite outcome of glycaemic control, blood pressure, lipids and depression scores | ||

| Kennedy 2013 | Practice training | Support for self‐management Participant guidebooks |

Systems‐based approach to self‐management support with practice supports and links made with related local services | No intervention effect noted | ||

| Krska 2001 | Individualised pharmaceutical care plans | Practice team‐implemented care plans | Pharmacist undertook medication review and devised pharmaceutical care plans | Reduction in pharmaceutical care issues | ||

| Martin 2013 | Training for community psychologists | Cognitive behavioural therapy sessions | Psychological care programme designed for headache and depression | Community psychologists | Reduced headaches and improved depression scores | |

| Morgan 2013 | Practice nurse training | Support for self‐management Goal setting Individualised care plans |

Nurse case manager | Quarterly reviews with practice nurse with GP stepping up care as needed | Improved depression scores | |

| Sommers 2000 | Risk reduction plan | Team based care with home assessment followed by team discussion, treatment plan and targets | Social worker | Reduced hospitalisation | ||

| Wakefield 2012 | Participation in home telehealth monitoring | Nurse case manager using telehealth monitoring and treatment algorithms | Improved blood pressure, no effect on glycaemic control | |||

| Predominantly Patient‐oriented interventions | ||||||

| Eakin 2007 | Support for self‐management with focus on diet and physical activity | Regular visits and follow‐up telephone calls | Health educator | Improvements in diet but not in physical activity | ||

| Garvey 2015 | Occupational therapist (OT) training |

OT‐led, group‐based support for self‐management programme (6 weeks) Goal setting and peer support |

GP and primary care team referral | OT with input from physiotherapist and pharmacist | Improvements in activity participation | |

| Hochhalter 2010 | Training for coaches running intervention | Patient Engagement workshop (x1) | Two follow‐up phone calls | Coach who delivered workshop | No effect on outcomes | |

| Lorig 1999 | Training for volunteer lay group leaders |

Chronic Disease Self Management Support Programme (six sessions) Peer support |

Volunteer lay group leaders supported by study team | No primary outcome specified. Multiple outcomes reported with mixed effects | ||

| Lynch 2014 |

Diabetes self management support groups (18 sessions) Peer support Goal setting and behaviour skills training |

Dietician led groups | No effect on primary outcome of weight reduction | |||

The predominant intervention component is highlighted in bold text for each study

No study contained a financial‐type intervention element

We excluded the following interventions:

Professional educational interventions or research initiatives where there was no specified structured clinical care delivered to an identified group of people with multimorbidity.

Interventions including people with comorbid conditions where the intervention was targeted solely at one condition and did not address the full extent of the multimorbidity. This commonly arises in relation to chronic disease and comorbid depression, so called 'depression plus one studies'. These are increasingly common as the link between depression and most chronic conditions has now been well established (Simon 2001). They include interventions designed to address depression in participants rather than targeting all conditions identified. We therefore excluded such studies if the intervention was only targeted at the depression and did not address the full extent of the multimorbidity.

The comparison was usual care.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies if they reported any objective, validated measure of:

Patient clinical or mental health outcomes (e.g. blood pressure, symptom scores, depression scores).

Patient‐reported outcome measures (e.g. quality of life, well‐being, measures of disability or functional status).

Utilisation of health services (e.g. hospital admissions).

Patient behaviour (e.g. measures of medication use and adherence, and other objective measures such as goal attainment (Cox 2002; Gordon 1999; Kiresuk 1968), if measured with a validated scale.

Provider behaviour (e.g. chronic disease management scores).

Acceptability of the service to recipients and providers, and treatment satisfaction were included if it was reported in a study that reported objective outcome measures behaviour.

Economic outcomes (e.g. full economic analyses incorporating measures of efficiency or effectiveness in relation to costs or direct costs depending on what was reported in included studies). Where direct costs were reported alone, we indicated whether these costs related to society, the health service, or the recipients. We also reported, where possible, costs in relation to the specific year and currency presented; whether costs related to total costs or simple fees charged; what was included in the cost calculations; and over what time period costs were calculated.

We excluded attitude and knowledge outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases without language restrictions up to 28 September 2015:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Library, 2015, Issue 10, Wiley

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), The Cochrane Library, 2015, Issue 3, Wiley

MEDLINE, 1990 to September 2015, In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations, OvidSP

EMBASE, 1980 to September 2015, OvidSP

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register, Reference Manager

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), 1980 to September 2015, EBSCOHost

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), 1985 to September 2015, OvidSP

CAB Abstracts, 1973 to September 2015, EBSCOHost

HealthSTAR, 1999 to September 2015, OvidSP

We also searched the following trials registries:

We searched the IRCMO repository for unpublished/grey literature (IRCMO), and invited experts to inform us of other completed or ongoing studies

The search strategy was particularly challenging given the lack of a MeSH terms for multimorbidity. In addition, we were aware from existing epidemiological literature that the recognition of multimorbidity as a concept is relatively recent. Multimorbidity is sometimes used synonymously with the term comorbidity, though this tends to be used in relation to diseases that coexist with an index disease under study (de Groot 2004). However, comorbidity is a MeSH term, whereas multimorbidity is not, so we included both terms in our search. For pragmatic reasons we limited the MEDLINE search to articles indexed from 1990 onwards.

The search strategy published in the protocol (Smith 2007b) was not used; and the search strategy recorded for the 2007 search of MEDLINE was revised in 2009 to better capture the concept of multimorbidity. Results of the search were limited by filters for study design and an extensive list of intervention terms. Search strategies are provided in Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5. The MEDLINE search strategy was used in HealthSTAR and AMED; the Cochrane search strategy was used in DARE.

Searching other resources

We also:

(a) Searched the reference lists of included papers (b) Contacted authors of relevant papers regarding any further published or unpublished work where indicated

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All citations identified by the electronic searches were downloaded to reference manager software (EndNote 2013) and duplicates were removed. Potentially relevant studies were identified by review of the titles and abstracts of search results by the lead author (SS). We retrieved full text copies of all articles identified as potentially relevant. Two review authors (SS, HS, or EW) ) independently screened all citations found by the electronic searches and assessed each retrieved article for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement by discussion and consensus.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SS, HS or EW ) undertook data abstraction and cross checked data abstraction forms using a modified version of the EPOC data collection checklist (EPOC 2013a). Disagreements about data abstraction and quality were resolved by consensus between the review authors or through adjudication by the Cochrane contact editor.

We extracted the following information from the included studies: (1) Details of the intervention: a full description of the intervention was extracted as were details regarding aims; clinical protocols; use of case workers; remuneration/payment systems; providers involved; and theoretical framework on which the intervention was based; (2) Participants: patients, the nature of multimorbidity and how it was determined; providers, i.e. specialist and primary care providers, family members; (3) Clinical setting; (4) Study design; (5) Outcomes; (6) Results. Results were organised into: (i) Clinical outcomes; (ii) Mental health outcomes; (iii) Patient‐reported outcomes; (iv) Health service use (v) Recipient and provider behaviours; and (vi) Recipient and provider acceptability/satisfaction.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in all included studies using standard EPOC criteria (EPOC 2015) and included the following domains: allocation (sequence generation and concealment); baseline characteristics; incomplete outcome data; contamination; blinding; selective outcome reporting; and other potential sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported data in natural units for each study. For RCTs, we reported results as (1) Absolute difference (mean or proportion of outcome in intervention group minus control at study completion); (2) Relative percentage difference (absolute difference divided by post‐intervention score in the control group). We undertook meta‐analysis where appropriate in terms of participants, interventions and outcomes using random‐effects models. Analyses were undertaken for clinical outcomes (glycaemic control and blood pressure) and depression scores in the comorbidity studies. We also undertook meta‐analyses for HRQoL and self‐efficacy in all studies in which these were reported. All meta‐analyses apart from self efficacy had significant statistical heterogeneity so we present the figures for these analyses without the pooled estimates of effect.

Standardised effect sizes (SES) are presented in tables where possible, i.e. where studies reported relevant data for their calculation. We have reported the range of effects using SES in the text of the results and used the generally accepted convention that an SES of more than 0.2 indicates a small intervention effect, an SES of more than 0.5 indicates a moderate intervention effect and an SES of more than 0.8 is a large effect size (Cohen 1988).

For ITS we had planned to report two effect sizes: (1) The change in the outcome immediately after the introduction of the intervention. (2) The change in the slope of the regression lines.

However, no ITS studies were identified.

Unit of analysis issues

None of the included studies had unit of analysis errors.

Dealing with missing data

If data on multimorbidity sub‐groups were missing from potentially eligible studies, we contacted authors to obtain the information. Two studies provided additional data on sub‐groups with multimorbidity (Coventry 2015; Eakin 2007). We did not include any studies with more than 20% missing data in meta‐analyses and did not make any assumptions regarding missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed included studies in terms of clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by examining forest plots and considering the I² statistic (Cochrane Handbook). We planned to prepare tables and funnel plots comparing effect sizes of studies grouped according to potential effect modifiers (for example, simple versus multifaceted interventions) if sufficient studies had been identified but this was not possible.

If there had been enough studies, we had planned to use meta‐regression to see whether the effect sizes could be predicted by study characteristics. These could, for example, include duration of the intervention, age groups, and simple versus multifaceted interventions (Cooper 1994). We also considered formal tests of homogeneity (Petitti 1994). None of these quantitative methods were possible for this version of the review but will be considered for future review updates.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed incomplete reporting of outcomes, where possible, within the 'Risk of bias' tables. This was only possible for studies that had published protocols or specifically reported different results than the outcomes mentioned in the methods sections of included papers.

Data synthesis

We expected that included studies would measure similar outcomes using different methods. These included either continuous variables (such as different depression scales) or dichotomous process measures (such as proportion of people with recovery from depression). For continuous outcomes, we reported means and standard deviations at study completion with the absolute difference and relative percentage difference. We calculated standardised effect sizes for continuous measures by dividing the difference in mean scores between the intervention and comparison group in each study, by an estimate of the pooled standard deviation. For categorical outcomes, we reported the proportions in the intervention and control groups with the absolute difference and relative percentage difference.

We undertook meta‐analysis of studies that were similar in terms of settings, participants, interventions, outcome assessment and study methods. If there was a high I² indicating statistical heterogeneity, we used graphs to illustrate the results but did not present the combined effects as the heterogeneity indicates that combining the studies in a meta‐analysis is inappropriate. Where meta‐analysis was not possible we carried out a narrative synthesis of the results and presented the results based on outcome groupings. See Additional tables.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for the main outcomes using the following GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria (Guyatt 2008); and present the main findings with our judgments in a 'Summary of findings' table

1. Study limitations (i.e. risk of bias). 2. Consistency of effect. 3. Imprecision. 4. Indirectness. 5. Publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to consider subgroup analyses based on the degree of multimorbidity of participants estimated by the number of conditions per person. These analyses were not possible due to the variation in definitions of multimorbidity and characteristics of participants across studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to undertake sensitivity analyses based on intervention type or clear distinctions in studies with different risk of bias but this was not possible due to the limited number of meta‐analyses undertaken with each containing relatively few studies.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for the main outcomes using the following GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria (Guyatt 2008) including risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and other potential criteria such as publication bias. We presented the main findings with our judgments in a 'Summary of findings' table. We used the EPOC guidance for preparing a Summary of Findings (SoF) table using GRADE (EPOC 2017a). We included the following outcomes in the Summary of Findings Table: HRQoL, mental health outcomes, clinical outcomes, other patient reported outcomes, health behaviours, healthcare utilisation, medicines outcomes and provider behaviour.

We have included worksheet that outline the decision making process when applying GRADE for the three comparisons (Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

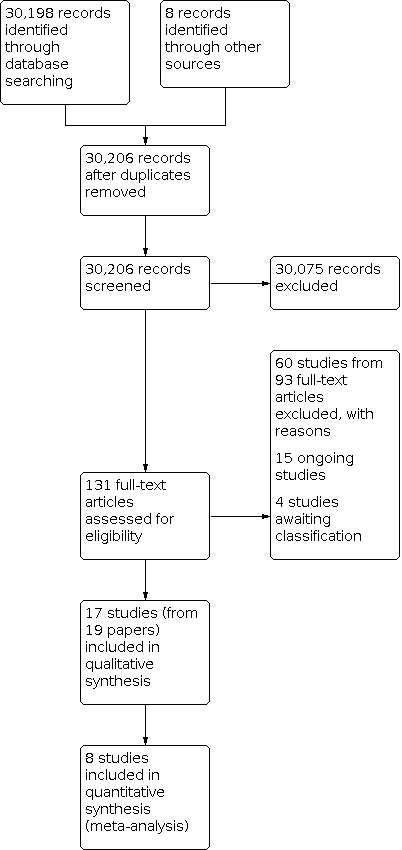

The electronic searches yielded 30,206 original citations after duplicates were removed (Figure 1). Of these, 30,075 citations were irrelevant and directly excluded. Full texts were retrieved for 131 studies. Of these, 60 studies from 93 papers were excluded with reasons Characteristics of excluded studies. Fifteen studies are on‐going (Characteristics of ongoing studies) ,. Seventeen studies from 19 papers were eligible for inclusion in this review and four other studies are awaiting classification.(Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

1.

Flow Diagram

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table

Study design

We identified 17 RCTs eligible for inclusion in the review, 9 from the original review (Bogner 2008; Boult 2011; Eakin 2007; Hochhalter 2010; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Krska 2001; Lorig 1999; Sommers 2000;) and 8 identified in this update (Barley 2014; Coventry 2015; Garvey 2015; Kennedy 2013; Lynch 2014; Martin 2013; Morgan 2013; Wakefield 2012). No other study designs with eligible interventions were identified.

Population/participants

There were a total of 8408 participants across all studies. The interventions varied in duration from eight weeks to two years, with the majority lasting 6 to 12 months. There was also variation in post intervention follow‐up, varying from immediate follow‐up to follow‐up 12 months post intervention cessation.

Eight of the 17 studies recruited participants with a broad range of conditions (Boult 2011; Eakin 2007; Garvey 2015; Hochhalter 2010; Hogg 2009; Krska 2001; Lorig 1999; Sommers 2000), whereas the remaining nine focused on the following comorbidities: depression and hypertension (Bogner 2008); depression and diabetes and/or heart disease (Barley 2014; Coventry 2015; Morgan 2013; Katon 2010); depression and headache (Martin 2013); diabetes and hypertension (Lynch 2014; Wakefield 2012); and a sub‐group of people with at least two of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and irritable bowel syndrome (Kennedy 2013).

Settings

All studies were set in primary care or community settings in the USA, apart from Krska 2001 which was set in the UK National Health Service and Hogg 2009 which was set in Canada. Seven were funded by a government or university grant (Coventry 2015; Garvey 2015; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Kennedy 2013; Krska 2001; Lorig 1999); and the remaining studies were funded by charitable foundations. None were funded directly by the pharmaceutical industry.

Comparison intervention

In the majority of included studies, the comparator was usual medical care which in some studies was supplemented by a newsletter or leaflet (Eakin 2007;), or involved a baseline assessment but no follow‐on intervention (Bogner 2008; Garvey 2015; Katon 2010; Krska 2001). These minimal additions to usual care could be considered as being within the variation of usual care provided in different settings. One study invited those allocated to a control group to attend a group session based on an unrelated topic (Hochhalter 2010). This was an attempt to ensure that the intervention effect did not relate to the group setting but related to the intervention content.

Description of interventions

The interventions were all multifaceted and brief descriptions for each study are provided in the Characteristics of included studies. No study specifically reported consumer involvement in the intervention design.

As outlined in the methods, we used the EPOC taxonomy of interventions to describe and categorise the interventions tested in these studies (EPOC 2002). While the interventions identified all involved multiple components they could be divided broadly into two main groups. In 12 of 17 studies, the interventions were primarily organisational, for example case management or addition of a pharmacist to the clinical care team (Barley 2014; Bogner 2008; Boult 2011; Coventry 2015; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Kennedy 2013; Krska 2001; Martin 2013; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000; Wakefield 2012). In the remaining five studies, the interventions were primarily patient‐oriented, for example self‐management support groups (Eakin 2007; Garvey 2015; Hochhalter 2010; Lorig 1999; Lynch 2014). However, there were overlapping elements with some organisational‐type studies including patient‐oriented elements such as education provided by a case manager and vice versa. No study involving financial or regulatory type interventions were identified. We have included an additional table which outlines intervention elements and indicates which elements featured in each of the included studies (Table 2)

Excluded studies

We excluded 75 studies in total, see Characteristics of excluded studies. Thirty‐five studies were excluded on the basis of ineligible participants. In some of these studies there was a potential multimorbidity sub‐group but these data were not reported or not available from authors when requested. Twenty‐six studies were excluded on the basis of an ineligible intervention. This was usually because it was conducted in a specialist setting or had a single‐condition focus despite participants having multiple conditions. The remaining studies were excluded on the basis of study design, largely due to absence of control groups.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table, Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies. Overall three of the 17 studies reported all elements for the risk of bias domains. Two studies reported domains with a high risk of bias and in 13 studies there were domains classified as unclear due to lack of reporting.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation concealment was assessed as adequate in eight of the 17 studies (Barley 2014; Boult 2011; Coventry 2015; Garvey 2015; ; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Krska 2001; Sommers 2000), but was assessed as unclear in the remainder. Baseline measurement of outcomes was carried out in all studies. All reported adequate follow‐up of participants except Lorig 1999 and Wakefield 2012 where the risk of bias was assessed as unclear. Lorig 1999 did not provide specific details pertaining to follow‐up for the multimorbidity subgroup, although follow‐up for the overall study was assessed as adequate. There was high risk of bias in Martin 2013 with poorer follow‐up in the intervention group (57%) compared to the control group (80%) at study completion. Objective outcomes were used in all but two studies, Krska 2001 and Hogg 2009, where this dimension was assessed as unclear. Krska 2001 used a measure detailing pharmaceutical care issues (PCIs) which was a previously developed classification system modified for the study. Hogg 2009 collected data on chronic and preventive care delivery from individuals' records but the accuracy of this process was not described. Blinding of outcome assessment was assessed as done in six studies (Boult 2011; Coventry 2015;; Hochhalter 2010; Katon 2010; Lorig 1999; Sommers 2000). It was assessed as unclear in nine studies (Barley 2014; Bogner 2008; Eakin 2007; Hogg 2009; Lynch 2014; Martin 2013; Morgan 2013; Wakefield 2012); and assessed as not done in Garvey 2015 and Krska 2001.

Five of the 17 studies had a cluster design that ensured no contamination of control participants (Boult 2011; Coventry 2015; Kennedy 2013; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000). Contamination of participants allocated to the control group was unlikely in a further seven studies where the intervention was directed at recipients rather than providers (Barley 2014; Bogner 2008; Garvey 2015; Eakin 2007; Lorig 1999; Lynch 2014; Hochhalter 2010), but was possible in the remaining studies four studies (Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Martin 2013; Wakefield 2012). However, Katon 2010 provided an appendix outlining potential contamination and indicated that it was minimal and, if it had occurred, it would have diluted rather than increased the significant effect size of their intervention. Krska 2001 stated that contamination of control participants who attended the same general practitioners (GPs) as the intervention participants could have occurred but that a cluster design would have been more problematic due to differential prescribing patterns between practices. All studies had low risk of selective outcome reporting and had no apparent other biases.

The five cluster randomised controlled trials accounted for clustering effects in their analysis so there were no unit of analysis errors (Boult 2011; Coventry 2015; Kennedy 2013; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000).

Certainty of the evidence

See Table 1. In general, while all the included studies were RCTs the main limitation related to a lack of consistency of effect for most outcomes. Only the mental health outcomes, largely relating to depression in the comorbidity studies, were regarded as having a high GRADE ranking. We downgraded the evidence for effects on clinical and patient‐reported outcomes to moderate due to lack of consistency of effect across studies and small effect sizes. We downgraded the evidence for effects on provider behaviour to moderate, due to limited available data for calculation of standardised effect sizes (SES) and lack of clarity regarding the clinical importance of the results. We downgraded the evidence for effects on health service utilisation and medication use and adherence to low, due to variation across studies and small effect sizes. We did not include economic outcomes in the Table 1 due to the lack of robust economic analyses, rather we summarised this outcome in Table 3.

2. Costs.

| Study | Study type | Outcome | Result | Notes |

| Barley | RCT | Cost‐effectiveness | The intervention demonstrated marginal cost effectiveness up to a QALY threshold of GBP 3035 | |

| Boult | RCT | Total healthcare cost | Saving of USD 75,000 per GCN and USD 1364 per participant | USD in 2007 Initial result only ns |

| Katon | RCT | Cost‐effectiveness | Mean reduction of 114 days in depression free days and an estimated difference of 0.335 QALYs (95% CI −0.18 to 0.85). The intervention was associated with lower OPD costs with a reduction of USD 594 per participant (95% CI USD −3241 to USD 2053). | Non‐significant but 99.7% probability that the intervention met the threshold of < USD 20,000 per QALY |

| Krska | RCT | Mean cost of medicines | Int: 38.83 Con: 42.61 Absol diff 3.78 Rel %diff 9% |

GBP in 2000 ns SES = 0.13 |

| Lorig | RCT | Intervention cost per completed participant | USD 70 | USD in 1998 See text for assumptions made |

| Lorig | RCT | Cost savings per individual | USD 750 | USD in 1998 See text for assumptions made |

| Sommers | RCT | Savings per individual | USD 90 | USD in 1994 See text for assumptions made |

* refers to whether original study reported statistically significant improvement in this outcome

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Effects by type of interventions

We have presented an overview of intervention components for each study, highlighting the main intervention component in bold text and have included a brief summary of the intervention effect on the study primary outcomes in Table 2. The description of intervention components is based on reporting of intervention components in each paper and this is not consistent across studies. For example, most studies were likely to have included training of practitioners involved in interventions but not all studies reported this as an intervention component. We have also presented an overview of results based on whether the studies addressed general multimorbidity or comorbidity in Table 4.

3. Overview of outcomes.

| Outcome category | Outcome | No. studies with this outcome | No. studies with p< 0.05 for this outcome | |

| Physical Health | Hb1Ac | 5 | 2 | |

| BP | 6 | 2 | ||

| Cholesterol | 2 | 1 | ||

| Other symptom score | 4 | 1 | ||

| Mental Health | Depression scores | 8 | 6 | |

| % improved depression | 1 | 1 | ||

| Anxiety scores | 4 | 3 | ||

| Cognitive symptom management | 1 | 0 | ||

| Psychosocial | QoL/general health | 10 | 4 | |

| Functional impairment & disability | 5 | 2 | ||

| Social (activity/support) | 4 | 1 | ||

| Self efficacy | 7 | 3 | ||

| Home hazards | 1 | 0 | ||

| Health service use | Visits/use service | 5 | 0 | |

| Hospital admission related | 6 | 2 | ||

| Patient health related behaviours | Exercise/diet | 6 | 2 | |

| Medication adherence | 5 | 2 | ||

| Provider behaviour | Prescribing | 3 | 2 | |

| Disease management | 3 | 3 | ||

| Costs | Direct costs or cost effectiveness | 6 | Not applicable |

* Multimorbidity is defined as two or more independent conditions within the same individual whereas comorbidity refers to linked conditions. In this review comorbidity studies included depression and diabetes or depression and hypertension

** The scales or measurements used in each study for the outcomes are described in the Table of included studies

Organisational interventions

Twelve of the 17 included studies had organisational‐type interventions (Barley 2014; Bogner 2008; Boult 2011; Coventry 2015; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Kennedy 2013; Krska 2001; Martin 2013; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000; Wakefield 2012). These predominantly involved case management and coordination of care or the enhancement of skill mix in multidisciplinary teams in addition to delivery of patient care.

1. Clinical outcomes

Eight of the 12 organisational type studies reported clinical outcomes. These studies had a range of standardised effect sizes (SES) varying from 0.01 to 1.6. Interventions aimed at improving management of risk factors in comorbid conditions were more likely to have larger effect sizes (e.g. Bogner 2008; Katon 2010; Morgan 2013).

Five studies reported six measures of glycaemic control (five mean HbA1c and one study reported percentage achieving at least 0.5% reduction in HbA1c). Katon 2010 and Morgan 2013 reported improvements in mean HBA1c; however, Morgan 2013 had a substantial proportion of missing HbA1c data at study completion so these data were not included in the meta‐analysis of HbA1c. Hogg 2009, Lynch 2014 and Wakefield 2012 found little or no difference in HbA1c.Lynch 2014 The SES ranged from 0.05 to 0.38 and none of these studies had an SES greater than 0.5. The mean difference (MD) was ‐0.193 (95% CI −0.47 to 0.10) as outlined in Figure 4.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycaemic control (HbA1c) Diabetes outcome: 1.1 HbA1c at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

Five studies reported on systolic blood pressure (SBP). Bogner 2008 and Katon 2010 reported improvements in blood pressure, although this was of minimal clinical significance in Katon 2010. Morgan 2013 and Wakefield 2012 reported little difference. The standardised effect sizes (SES) ranged from 0.01 to 0.78 but only one of these four studies had an SES greater than 0.5. The MD was −3.10 (95% CI −7.26 to 1.06) as illustrated in Figure 5.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Systolic Blood Pressure: outcome: 2.1 Systolic blood pressure at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

Two studies reported on cholesterol. Katon 2010 found a reduction in LDL cholesterol, whereas Morgan 2013 found no meaningful difference (SES ranges 0.22 to 0.26). Katon 2010 reported a composite primary outcome that combined three risk factors, which showed an improvement in intervention participants compared to control (see Table 5).

4. Clinical Outcomes.

| Study | Study type | Outcomes | Results | Notes |

| Barley | RCT | % with angina (Rose Angina score) | Int 22/31 Con 30/37 Absol diff 8, Rel % diff 27% |

ns |

| Bognor | RCT | Systolic BP | Int 127.3 (SD 17.7) Con 141.3 (SD 18.8) Absol diff 14, Rel % diff 10% |

* SES = 0.78 |

| Bognor | RCT | Diastolic BP | Int 83 (SD 10.7) Con 81.4 (SD 11.1) Absol diff 9.2, Rel % diff 11% |

* SES = 0.15 |

| Hogg | RCT | Systolic BP | Int 124.3 Con 124.2 Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff < 0.1% |

ns (No SDs reported) |

| Hogg | RCT | HbA1c | Int 7.01 Con 6.78 Absol diff 0.23, Rel % diff 3% |

ns |

| Katon | RCT | Systolic BP | Int 131 (SD 18.4) Con 132.3 (SD 17.2) Absol diff 1.3, Rel % diff 1% |

* SES = 0.07 |

| Katon | RCT | HbA1c | Int 7.33 (SD 1.21) Con 7.81 (SD 1.9) Absol diff 0.48, Rel % diff 6% |

* SES = 0.32 |

| Katon | RCT | Cholesterol | Int 91.9 (SD 36.7) Con 101.4 (SD 36.6) Absol diff 9.5, Rel % diff 9% |

* SES = 0.26 |

| Katon | RCT | Composite: all three risk factors (BP, HbA1c and cholesterol) below guidelines |

Int 36/97 (0.37) Con: 19/87 (0.22) Absol diff 15, Rel % diff 68% |

* |

| Lorig | RCT | Pain/ physical discomfort | Int 59.8 (SD 20.1) Con 60.6 (SD 17.1) Absol diff 0.8, Rel % diff 1% |

SES = 0.04 ns |

| Lorig | RCT | Energy/fatigue | Int 2.18 (SD 0.73) Con 2.02 (SD 0.75) Absol diff 0.16, Rel % diff 8% |

ns |

| Lorig | RCT | Shortness of breath | Int 1.34 (SD 0.91) Con 1.58 (SD 0.83) Absol diff 0.24, Rel % diff 15% |

ns |

| Lynch | RCT | HbA1C | Int 7.4 (SD 1.6) Con 7.5 (SD 1.6) Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff 6.7% |

ns SES = 0.06 |

| Lynch | RCT | % with at least 0.5 absolute reduction in HbA1c | Int 15/30 (0.05) 7/31 Con (0.21) Absol diff 29, Rel % diff 138% |

* |

| Lynch | RCT | Mean SBP | Int 135.8 (SD 21.4) Con 136.7 (SD 23) Absol diff 0.9, Rel % diff 0.6% |

ns SES = 0.04 |

| Morgan | RCT | HbA1C | Int 6.9 (SD 1.21) Con 7.4 (SD 1.42) Absol diff 0.5, Rel % diff 6.7% |

* SES = 0.38 |

| Morgan | RCT | Systolic BP | Int 132.4 (SD 19) Con 131.2(SD 19.6) Absol diff 1.2, Rel % diff 0.9% |

ns SES = 0.02 |

| Morgan | RCT | Cholesterol | Int 4.22 (SD 0.94) Con 4.44 (SD 1.06) Absol diff 0.22, Rel % diff 5% |

ns SES = 0.22 |

| Morgan | RCT | Mean BMI | Int 31.2 (SD 6) Con 31.0 (SD 6) Absol diff 0.2, Rel % diff 0.6% |

ns SES = 0.03 |

| Sommers | RCT | Symptom scores | Int 17.2 Con 18.9 Absol diff 1.7, Rel % diff 9% |

ns |

| Wakefield | RCT | HbA1c | Int 6.9 (1.1) Con 6.95 (1.1) Absol diff 0.05, Rel % diff 0.7% |

ns SES = 0.05 |

| Wakefield | RCT | Systolic BP | Int 133 (16.6) Con 137 (17.3) Absol diff 4, Rel % diff 3% |

ns SES = 0.24 |

| Martin | RCT | Mean headache rating | Int 0.63 (SD 0.5) Con 1.01 (SD 0.83) Absol diff 0.38, Rel % diff 38% |

* SES = 0.58 |

* refers to whether original study reported statistically significant improvement in this outcome

** Total number with final data collected was 384. No final numbers of intervention and control participants presented.

Four studies reported symptom scores relating to clinical outcomes. Barley 2014, Lorig 1999 and Sommers 2000 found little or no difference whereas Martin 2013 reported improvements in mean headache rating (see Table 5).

2. Mental health outcomes

Seven studies presented data on mental health outcomes (Barley 2014; Bogner 2008; Coventry 2015; Katon 2010; Martin 2013; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000). Five of the seven studies reported improvements in a range of depression measures whereas two showed no improvements in depression outcomes (Barley 2014; Sommers 2000). We undertook two meta‐analyses: a meta‐analysis of Patient Health Questionnaire, version 9 (HQ9) depression scores; and a meta‐analysis of standardised mean difference (SMD) in depression scores for the studies with available data where depression was a targeted condition. This suggests a modest intervention effect. The meta‐analysis for PHQ9 scores had high heterogeneity so we do not report the pooled effect (Figure 6). The SMD for other depression scores was −0.41 (95% CI −0.63 to −0.20) (Figure 7). The range in SESs for depression outcomes across these studies was from 0.09 to 1.18 with four of the nine outcomes indicating moderate to large effect sizes (i.e. SES > 0.5). These higher effect sizes were all reported in the studies in which depression was a focus of the intervention.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Depression scores: 3.1 PHQ9 Depression scores at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Depression scores: 4.1 Depression scores at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

Three studies reported on anxiety measures, two showed improvements (Coventry 2015 and Martin 2013) whereas Barley 2014 reported little difference (see Table 6). There were small effect sizes in all studies (SES range 0.08 to 0.26).

5. Mental Health Outcomes.

| Study | Study type | Outcome | Result | Notes |

| Barley | RCT | PHQ9 depression score | Int 12.6 (SD 7.1) Con 12 (SD 6.9) Absol diff 0.6, Rel % diff 8% |

ns SES = 0.09 |

| Barley | RCT | HADS depression score | Int 9.5 (SD 4.6) Con 8.8 (SD 4.8) Absol diff 0.7, Rel % diff 8% |

ns SES = 0.15 |

| Barley | RCT | HADS anxiety score | Int 9.9 (SD 7.1) Con 9.5 (SD 5.4) Absol diff 0.4, Rel % diff 4% |

ns SES = 0.08 |

| Bognor | RCT | CES depression score | Int 9.9 (SD 10.7) Con 19.3 (SD 15.2) Absol diff 9.4, Rel % diff 49% |

* SES = 0.75 |

| Coventry | RCT | SCL‐D13 depression score | Int 1.76 (SD 0.9) Con 2.02 (SD 0.9) Absol diff 2.6, Rel % diff 13% |

* SES = 0.28 |

| Coventry | RCT | PHQ9 depression score | Int 11.3 (SD 6.5) Con 13.1 (SD 6.5) Absol diff 1.8, Rel % diff 14% |

* SES = 0.28 |

| Coventry | RCT | GAD‐7 anxiety score | Int 8.2 (SD 5.8) Con 9.7 (SD 5.9) Absol diff 1.5, Rel % diff 15% |

* SES = 0.26 |

| Garvey | RCT | HADS total score | Int 15.6 (SD 8.3) Con 16.7 (SD 8.2) Absol diff 1.1, Rel % diff 6.5% |

ns SES = 0.13 |

| Katon | RCT | SCL 20 depression score | Int 0.83 (SD 0.66) Con 1.14 (SD 0.68) Absol diff 0.31, Rel % diff 27% |

* SES = 0.46 |

| Katon | RCT | Patient global improvement in depression | Int 41/92 Con 16/91 Absol diff 27, Rel % diff 150% |

* |

| Lorig | RCT | Cognitive symptom management score | Int 1.75 Con 0.98 Absol diff 0.77, Rel % diff 79% |

ns |

| Martin | RCT | PHQ9 depression score | Int 6.7 (SD 4.6) Con 12.6 (SD 5.3) Absol diff 5.9, Rel % diff 47% |

* SES = 1.18 |

| Martin | RCT | BDI ‐Depression score | Int 13.1 (SD 8.6) Con 28.7 (SD 9.5) Absol diff 15.6, Rel % diff 54% |

* SES = 1.73 |

| Martin | RCT | BAI Anxiety score | Int 10.5 (SD 10.8) Con 16.4 (SD 9.3) Absol diff 5.9, Rel % diff 36% |

* SES = 0.1 |

| Morgan | RCT | PHQ9 depression score | Int 7.1 (SD 4.7) Con 9.0 (SD 5.5) Absol diff 1.9, Rel % diff 21% |

* SES = 0.37 |

| Sommers | RCT | GDS score (depression) | Int 4.1 Con 4.1 Absol diff 0, Rel % diff 0% |

ns |

* refers to whether original study reported statistically significant improvement in this outcome

3. Patient‐reported outcome measures

Nine of the organisational‐type studies presented patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Nine of these reported a variety of HRQoL measures with a range of effects from SES of 0.03 to 0.84. Coventry 2015 Three studies reported small effect sizes (Coventry 2015;Katon 2010; Martin 2013). The remaining six studies reported little or no effect (Barley 2014; Hogg 2009; Kennedy 2013; Krska 2001; Morgan 2013; Sommers 2000). Krska 2001 and Morgan 2013 reported that SF36 scores had been analysed across eight domains at study completion and reported little or no difference between groups, but did not present actual data. The mixed evidence regarding HRQoL is illustrated in Figure 8 which includes studies with available data but the pooled effect is not reported due to high statistical heterogeneity (I² = 73%).

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Health related quality of life, outcome: 5.1 HRQoL at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

Five organisational studies reported on self‐efficacy with a range in SES of 0.03 to 0.11, suggesting minimal effect. (Barley 2014; Hochhalter 2010; Kennedy 2013; Wakefield 2012; Coventry 2015). We undertook a meta‐analysis of standardised mean self‐efficacy scores in comorbidity studies and found no effect, SMD −0.05 (95% CI −0.12 to 0.22) (Figure 9).

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Self‐Efficacy, outcome: 6.1 Self‐efficacy score at immediate to 6 months post‐intervention follow up.

Two of the organisational studies reported measures relating to disability or impaired activities of daily living (IADL). Hogg 2009 reported no effect of interventions on IADL, whereas Coventry 2015 reported an improvement in the Sheehan Disability score in intervention participants.

Two of the organisational studies reported measures relating to Illness perceptions and both reported no effect (Barley 2014; Coventry 2015).

A range of other PROMs were also reported with mixed effects and none had an SES greater than 0.3. These are presented in Table 7.

6. Patient‐reported outcome measures.

| Study | Study type | Outcome | Result | Notes |

| Health Related Quality of Life | ||||

| Barley | RCT | SF12 PCS | Int 32.4 (SD 10.7) Con 33.3 (SD 9.2) Absol diff 0.7, Rel % diff 2% |

ns SES = 0.07 |

| Barley | RCT | SF12 MCS | Int 34.5 (SD 11.6 ) Con 33.6 (SD 12.5 ) Absol diff 0.9, Rel % diff 3% |

ns SES = 0.08 |

| Barley | RCT | HRQoL (WEMWBS) | Int 40.6 (SD 11.2) Con 39.6(SD 12.3) Absol diff 1, Rel % diff 2.5% |

ns SES = 0.08 |

| Coventry | RCT | HRQoL (WHOQOL) | Int 2.99 (SD 0.6) Con 2.91 (SD 0.6) Absol diff 0.08, Rel % diff 3% |

* SES = 0.13 |

| Garvey | RCT | HRQoL (EQ5D VAS) | Int 65.7 (SD 20.2) Con 50.5 (SD 16.3) Absol diff 15.2, Rel % diff 30% |

* SES = 0.84 |

| Hogg | RCT | SF 36 Mental Health | Int 52.4 Con 52.2 Absol diff 0.2, Rel % diff 0.3% |

ns |

| Hogg | RCT | SF 36 Physical Health | Int 44.3 Con 41.5 Absol diff 2.8, Rel % diff 6.7% |

ns |

| Katon | RCT | QoL score | Int 6.0 (SD 2.2) Con 5.2 (SD 1.9) Absol diff 0.8, Rel % diff 15% |

* SES = 0.44 |

| Kennedy | RCT | HRQoL (EQ5D) | Int 0.56 (SD 0.34) Con 0.57 (SD 0.32) Absol diff 0.01, Rel % diff 1% |

ns SES = 0.03 |

| Lorig | RCT | Psychological well‐being | Int 3.47 Con 3.33 Absol diff 0.04, Rel % diff 4% |

ns SES = 0.21 |

| Martin | RCT | HRQol (AQOL) | Int 26.3 (SD 4.76) Con 28.4 (SD 4.97) Absol diff 2.1, Rel % diff 7 % |

* SES = 0.4 |

| Sommers | RCT | SF36 score | Int 2.2 Con 3.3 Absol diff 1.1, Rel % diff 33% |

ns |

| Self‐efficacy | ||||

| Barley | RCT | Self‐efficacy score | Int 28.6 (SD 6.7) Con 27.9 (SD 8.1) Absol diff 0.11, Rel % diff 2.5% |

ns SES = 0.09 |

| Coventry | RCT | Self‐efficacy score | Int 5.72 (SD 1.9) Con 5.53 (SD 1.9) Absol diff 0.18, Rel % diff 3.2% |

ns * SES = 0.09 |

| Garvey | RCT | Self efficacy score | Int 6.8 (SD 1.5) Con 5.3 (SD 1.9) Absol diff 1.47, Rel % diff 28% |

* SES = 0.86 |

| Hochhalter | RCT | Self‐efficacy | Int 7.4 Con 8.0 Absol diff 0.6, Rel % diff 7.5% |

ns |

| Kennedy | RCT | Self‐efficacy | Int 68 (SD 23.4) Con 68.7 (SD 23.1) Absol diff 0.7, Rel % diff 1% |

ns SES = 0.03 |

| Wakefield | RCT | Self‐efficacy | Int 8.1 (SD 1.9) Con 8.3 (SD 1.9) Absol diff 0.2, Rel % diff 2.4% |

ns SES = 0.11 |

| Daily function and disability | ||||

| Coventry | RCT | Sheehan Disability Score | Int 5.73 (SD 2.8) Con 5.83 (SD 2.8) Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff 2% |

* SES = 0.04 |

| Garvey | RCT | Frenchay Activities Index | Int 21.3 (SD 7.9) Con 18.9 (SD 7.2) Absol diff 2.4, Rel % diff 13% |

* SES = 0.32 |

| Garvey | RCT | Activities daily living: NEADL (total) | Int 47.2 (SD 11.9) Con 40.7 (SD 10.7) Absol diff 6.5, Rel % diff 16% |

* SES = 0.58 |

| Hogg | RCT | IADL | Int 10.6 Con 10.9 Absol diff 0.3, Rel % diff 2.7% |

ns |

| Lorig | RCT | Disability | Int 0.86 Con 0.96 Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff 10% |

ns |

| Lorig | RCT | Social role/activity limitation | Int 1.91, Con 1.98 Absol diff 0.07, Rel % diff 4% |

ns |

| Illness perceptions | ||||

| Coventry | RCT | Multimorbidity illness perception scale | Int 2.1 (SD 0.9) Con 2.28 (SD 0.9) Absol diff 0.18, Rel % diff 8% |

ns SES = 0.2 |

| Barley | RCT | Illness perceptions (BIPQ) | Int 40 (SD 14.8) Con 43(SD 31.1) Absol diff 3, Rel % diff 7% |

ns SES = 0.22 |

| Social support | ||||

| Coventry | RCT | Social support (ESSI) | Int 3.29 (SD 1.1) Con 3.4 (SD 1.0) Absol diff 0.11, Rel % diff 3% |

ns SES = 0.11 |

| Eakin | RCT | Multilevel support for healthy lifestyle | Int 2.7 Con 2.59 Absol diff 0.11, Rel % diff 4% |

ns |

| Other PROMs | ||||

| Barley | RCT | Patient‐reported needs (PSYCHLOPS) | Int 13.6 (SD 5.1) Con 13.4 (SD 5.4) Absol diff 0.2, Rel % diff 1.5% |

ns SES = 0.04 |

| Hochhalter | RCT | Total unhealthy days | Int 15.3 Con 14.1 Absol diff 1.2, Rel % diff 9% |

ns |

| Hogg | RCT | Total unhealthy days | Int 7.6 Con 9.9 Absol diff 2.3, Rel % diff 23% |

ns |

| Kennedy | RCT | Shared decision making (HCCQ) | Int 67.7 (SD 28) Con 69.3 (SD 26.1) Absol diff 1.6, Rel % diff 2% |

ns SES = 0.06 |

| Lorig | RCT | Self‐rated health | Int 3.42 Con 3.44 Absol diff 0.02, Rel % diff 0.6% |

ns |

| Lorig | RCT | Health distress | Int 1.97 Con: 2.13 Absol diff 0.16, Rel % diff 7.5% |

ns SES = 0.16 |

| Sommers | RCT | Social activities count | Int 8.7 Con:8.6 Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff 1% |

* (when adjusted for baseline diff) |

| Sommers | RCT | HAQ score | Int 0.44 Con 0.5 Absol diff 0.06, Rel % diff 12% |

ns |

* refers to whether original study reported statistically significant improvement in this outcome

4. Utilisation of health services

Five organisational studies reported outcomes on health services utilisation (Boult 2011; Hogg 2009; Katon 2010; Krska 2001; Sommers 2000). Sommers 2000 reported improvements for intervention group participants across a variety of measures relating to hospital admissions, whereas Boult 2011, Hogg 2009, Katon 2010 and Krska 2001 found no difference in admission‐related outcomes, although numbers of admissions in most of these studies were very small.

Three studies reported data in relation to health service visits with a range of providers none of which showed clear improvements in appropriate health service use (Boult 2011; Hogg 2009; Sommers 2000) (see Table 8). No studies that included health service utilisation reported data that could be used to calculate SESs.

7. Health service use.

| Study | Study type | Outcome | Result | Notes |

| Boult | RCT | No. hospital admissions | Int 0.7 Con 0.72 Absol diff 0.02, Rel % diff 3% |

ns |

| Boult | RCT | No. days in hospital | Int 4.26 Con 4.49 Absol diff 0.23, Rel % diff 5% |

ns |

| Boult | RCT | No. ED visits | Int 0.44 Con 0.44 Absol diff 0, Rel % diff 0 |

ns |

| Boult | RCT | No. PC visits | Int 9.98 Con 9.88 Absol diff 0.1, Rel % diff 1% |

ns |