Due to the increase of antifungal drug resistance and difficulties associated with drug administration, new antifungal agents for invasive fungal infections are needed. SCY-247 is a second-generation fungerp antifungal compound that interferes with the synthesis of the fungal cell wall polymer β-(1,3)-d-glucan.

KEYWORDS: Ibrexafungerp; candidiasis; β-(1,3)-d-glucan; fungerps; triterpenoid class

ABSTRACT

Due to the increase of antifungal drug resistance and difficulties associated with drug administration, new antifungal agents for invasive fungal infections are needed. SCY-247 is a second-generation fungerp antifungal compound that interferes with the synthesis of the fungal cell wall polymer β-(1,3)-d-glucan. We conducted an extensive antifungal screen of SCY-247 against yeast and mold strains compared with the parent compound ibrexafungerp (IBX; formerly SCY-078) to evaluate the in vitro antifungal properties of SCY-247. SCY-247 demonstrated similar activity to IBX against all of the organisms tested. Moreover, SCY-247 showed a higher percentage of fungicidal activity against the panel of yeast and mold isolates than IBX. Notably, SCY-247 showed considerable antifungal properties against numerous strains of Candida auris. Additionally, SCY-247 retained its antifungal activity when evaluated in the presence of synthetic urine, indicating that SCY-247 maintains activity and structural stability under environments with decreased pH levels. Finally, a time-kill study showed SCY-247 has potent anti-Candida, -Aspergillus, and -Scedosporium activity. In summary, SCY-247 has potent antifungal activity against various fungal species, indicating that further studies on this fungerp analog are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Echinocandins are effective against Candida and Aspergillus species and are commonly the front-line antifungal agents used (1). Species of Scedosporium are also susceptible to echinocandins, especially when combined with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (2, 3). However, there has been an increasing amount of fungal species developing resistance to echinocandins, particularly in Candida glabrata and more recently Candida auris (4–6). Additionally, echinocandins are available only as intravenous formulations, which may be a disadvantage with regard to availability and ease of access (7).

Species of Candida and Aspergillus are the most common causes of invasive fungal infections (IFIs), and Candida species are the fourth leading cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections in the United States (8, 9). Invasive candidiasis and invasive aspergillosis have been reported to make up to 53% and 19% of IFIs, respectively (10). However, Scedosporium and Fusarium species are among the fungi increasingly reported to cause infections, especially in immunocompromised patients (11–13). Additionally, Candida species, especially Candida albicans, are the most common organisms causing fungal urinary tract infections (UTIs) (14, 15).

Due to the increasing resistance to echinocandins and their limitation regarding method of drug administration (intravenous [i.v.]), development of novel antifungals with oral bioavailability and broad spectrum of activity are needed to target potential resistant fungi. One new antifungal, SCY-078, was assigned the name “ibrexafungerp” (IBX) by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Nonproprietary Name (INN) group. The name ibrexafungerp included a new stem root, "-fungerp," which indicated that SCY-078 was unique and a first-in-class compound. Fungerps are β-1,3-glucan synthase inhibitors that interfere with the synthesis of the fungal cell wall polymer β-(1,3)-d-glucan. The mechanism of action is similar to that of echinocandins, but fungerps are structurally distinct and suitable for both oral and intravenous formulations. IBX has demonstrated in vitro and in vivo antifungal efficacy against Candida infections and has completed phase III testing for the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). Additionally, IBX is currently in phase II and III clinical testing in patients with recurrent VVC (CANDLE; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04029116), refractory IFIs (FURI; NCT02244606), infections caused by Candida auris (CARES; NCT03363841), and invasive aspergillosis (SCYNERGIA; NCT03672292) (14–17). Although both oral and intravenous formulations of IBX are under development, IBX as an oral formulation has been the focus. Accordingly, progress on preclinical screening of additional members of the fungerp family is ongoing.

In this study, we conducted a primary antifungal screen of SCY-247 against yeast and mold strains by determining MIC for yeasts, minimum effective concentrations (MECs) for mold, and minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs). This primary screen showed that SCY-247 was active against different fungal isolates. We further examined the antifungal activity of SCY-247 against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. auris strains. We also explored the efficacy of this compound in combination with decreased pH conditions in the presence of synthetic urine (SU). Additionally, we explored the time-kill kinetics of SCY-247 against Candida, Aspergillus, and Scedosporium species.

RESULTS

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against Candida isolates.

Table 1 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of SCY-078 (IBX) against different Candida species tested. IBX demonstrated an MIC range of 0.031 to 4 µg/ml against all Candida species. When available, strains that previously showed high MIC values to commercially available antifungals were used. This represents 27 of the 47 Candida isolates tested. SCY-247 showed a similar MIC range compared with that of IBX, with a range of 0.031 to 8 µg/ml for all Candida species tested. MIC50 and MIC90 values were the same for SCY-247 and IBX (0.5 and 1 µg/ml, respectively). Overall, IBX and SCY-247 demonstrated similar MFC ranges and the same MFC50 and MFC90 values. Interestingly, SCY-247 demonstrated cidal activity against a greater number of isolates than IBX (41 and 35 isolates, respectively).

TABLE 1.

MIC/MFC ranges for the Candida isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activityc against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | |

| C. albicans (5) | 0.25–1 | 0.125–1 | 8 | 0.5–8 | 4/5 | 3/5 |

| C. auris (5) | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25–0.5 | 4 | 8–16 | 5/5 | 3/5 |

| C. glabrata (5) | 0.5 | 0.5–1 | 0.5–1 | 1–2 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| C. kefyr (5) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.125–1 | 0.25–4 | 0.5–2 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| C. krusei (6) | 0.5–8 | 0.5–4 | 2–8 | 1–8 | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| C. metapsilosis (5) | 0.031–4 | 0.031–2 | 0.125–8 | 0.25–16 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| C. orthopsilosis (5) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25–8 | 0.5–8 | 3/5 | 3/5 |

| C. parapsilosis (6) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | 4–8 | 0.5–16 | 3/6 | 2/6 |

| C. tropicalis (5) | 0.25–8 | 0.125–1 | 0.5–8 | 0.25–8 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| Total Candida sp. (47) | 0.031–8a | 0.031–4a | 0.125–8b | 0.25–16b | 41/47 | 35/47 |

MIC50 of 0.5, MIC90 of 1.

MFC50 of 4, MFC90 of 8.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against non-Candida yeast isolates.

Table 2 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against the remaining yeast isolates tested. Overall, SCY-247 demonstrated similar MIC and MFC ranges for all isolates tested as those of IBX. SCY-247 demonstrated cidal activity against a greater number of yeast isolates than IBX (68 and 59 isolates, respectively).

TABLE 2.

MIC/MFC ranges for various non-Candida yeast isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activityb against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | |

| Coccidioides immitis (5) | <0.125–0.25 | <0.125–0.25 | N/Aa | N/A | ||

| Cryptococcus neoformans (5) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2–4 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Geotrichum capitatum (5) | 0.5–2 | 1–2 | 8–16 | 8–16 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| Histoplasma sp. (5) | <0.125–0.25 | <0.125–0.25 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Kodamaea ohmeri (5) | 0.125–0.5 | 0.125–0.5 | 4–8 | 8–16 | 4/5 | 1/5 |

| Rhodotorula sp. (5) | 1–4 | 1–8 | 8–16 | 16 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5) | 0.125–0.25 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25–4 | 0.5–8 | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Trichosporon asahii (5) | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8–16 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| All yeasts total | 68/77 | 59/77 | ||||

N/A, not tested.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against Aspergillus isolates.

Table 3 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against Aspergillus isolates. Nineteen of the 20 Aspergillus isolates tested previously showed high MIC values to commercially available antifungals. SCY-247 demonstrated similar MIC ranges and MIC50 and MIC90 values for all isolates tested as those of IBX; neither SCY-247 nor IBX demonstrated cidal activity against the Aspergillus isolates.

TABLE 3.

MIC/MFC ranges for the Aspergillus isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activitye against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | |

| A. flavus (5) | 0.063 | <0.016 to 0.063 | 8 to >8 | >8 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| A. fumigatus (5) | 0.063 to 0.25 | 0.063 to 0.125 | 8 to >8 | 8 to >8 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| A. nidulans (5) | 0.063 to 0.125 | 0.031 to 0.063 | 8 to >8 | >8 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| A. terreus (5) | 0.031 to 0.63 | <0.016 to 0.031 | 8 to >8 | >8 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Aspergillus total (20) | 0.031 to 0.25a | <0.016 to 0.125b | 8 to >8c | 8 to >8d | 0/20 | 0/20 |

MIC50, 0.063; MIC90, 0.125.

MIC50 and MIC90, 0.063.

MFC50, 8; MFC90, >8.

MFC50 and MFC90, >8.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against Fusarium isolates.

Table 4 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against Fusarium isolates. All of the Fusarium isolates tested previously showed high MIC values to commercially available antifungals (n = 10). SCY-247 demonstrated similar MIC ranges and MIC50 and MIC90 values, as well as MFC ranges and MFC50 and MFC90 values, for all isolates tested as those of IBX. IBX and SCY-247 demonstrated cidal activity against all Fusarium isolates, for which an endpoint was determined.

TABLE 4.

MIC/MFC ranges for the Fusarium isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activityf against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | |

| F. oxysporum (5) | 8 to 16 | 8 to 16 | 8 to 32 | 16 to 32 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| F. solani (5) | 1 to 8 | 16 | 8 to 32 | 32 to >64 | 5/5 | 4/4e |

| Fusarium sp. total (10) | 1 to 16a | 8 to 6b | 8 to 32c | 16 to >64d | 10/10 | 9/9e |

MIC50 and MIC90, 8.

MIC50 and MIC90, 16.

MFC50, 16; MFC90, 32.

MFC50, 32; MFC90, 64.

Cidality indeterminable due to growth above the highest drug concentration.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against Scedosporium isolates.

Table 5 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against Scedosporium isolates. SCY-247 demonstrated slightly lower MIC ranges and MIC50 and MIC90 values, as well as MFC ranges and MFC50 and MFC90 values, for all isolates tested than those of IBX. However, these values were all within 2 dilutions. SCY-247 demonstrated cidal activity against a greater number of Scedosporium isolates tested than IBX (7 and 4 isolates, respectively).

TABLE 5.

MIC/MEC ranges for the Scedosporium isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activityf against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | SCY-078 | SCY-247 | SCY-078 | SCY-247 | SCY-078 | |

| S. apiospermum (5) | 2 to 4 | 8 | 16 to >64 | >64 | 3/5 | 0/0a |

| S. prolificans (5) | 2 to 4 | 8 | 8 to >64 | 8 to >64 | 4/5 | 4/4a |

| Scedosporium sp. total (10) | 2 to 4b | 8c | 8 to >64d | 8 to >64e | 7/10 | 4/4 |

Cidality indeterminable due to growth above the highest drug concentration.

MIC50, 2; MIC90, 4.

MIC50 and MIC90, 8.

MFC50, 16; MFC90, >64.

MFC50 and MFC90, >64.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC activity of SCY-247 against remaining mold species.

Table 6 shows the MIC and MFC data for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against the remaining mold species. SCY-247 demonstrated similar MIC ranges, MIC50 and MIC90 values, MFC ranges, and MFC50 and MFC90 values for all isolates tested as those of IBX.

TABLE 6.

MIC/MFC ranges for the remaining mold isolates tested against SCY-247 and IBX

| Organism (n) | MIC (µg/ml) range against: |

MFC (µg/ml) range against: |

Cidal activityb against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | SCY-247 | IBX | |

| Acremonium sp. (5) | 2 to 4 | 2 to 8 | 8 to 16 | 32 to 64 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| Fonsecaea pedrosoi (5) | 4 | 8 to 16 | 8 to >64 | 16 to >64 | 4/5 | 3/3a |

| Paecilomyces sp. (5) | <0.125 to 4 | <0.125 to 8 | 4 to >64 | 32 to >64 | 0/5 | 0/4a |

| Pseudallescheria boydii (5) | 2 to 4 | 4 to 8 | >64 | >64 | 0/5 | 0/1a |

| Rhizopus oryzae (5) | 8 to 16 | 32 | 16 to >64 | >64 | 1/1a | 0/0a |

| Trichoderma sp. (5) | 1 to 4 | 2 to 8 | 64 to >64 | >64 | 0/5 | 0/4a |

| All molds | 27/61 | 20/45 | ||||

Cidality indeterminable due to growth above the highest drug concentration.

No. of strains killed/no. of strains tested.

MIC and MFC determinations against Candida auris.

Table 7 shows the MIC/MFC ranges (µg/ml) of SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against an expanded panel of C. auris isolates. SCY-247 demonstrated a MIC range and MIC50 and MIC90 of 0.06 to 1 µg/ml, 0.5 µg/ml, and 0.5 µg/ml, respectively. IBX showed similar results with a MIC range, MIC50, and MIC90 of 0.06 to 2 µg/ml, 0.5 µg/ml, and 0.5 µg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 7.

MIC/MFC ranges for SCY-247 and IBX against the C. auris isolates testeda

| Compound | MIC (µg/ml) |

MFC (µg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | Range | 50% | 90% | |

| SCY-247 | 0.06–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5–8 | 4 | 4 |

| IBX | 0.06–2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25–8 | 4 | 8 |

an = 44.

SCY-247 demonstrated an MFC range, MFC50, and MFC90 of 0.5 to 8 µg/ml, 4 µg/ml, and 4 µg/ml, respectively. IBX again showed similar results, with an MFC range, MFC50, and MFC90 of 0.25 to 8 µg/ml, 4 µg/ml, and 8 µg/ml, respectively.

Table 8 shows the MIC and MFC values for SCY-247 compared with those of IBX against the individual C. auris isolates tested (µg/ml). For each strain tested, SCY-247 and IBX showed MIC and MFC values within 2 dilutions of each other. However, SCY-247 demonstrated cidal activity against 14 strains, while IBX demonstrated cidal activity against 7 of the C. auris isolates tested.

TABLE 8.

MIC and MFC values with fungicidal or fungistatic activity indicated for SCY-247 and IBX against the individual C. auris isolatesa tested

| Isolate identifierb | SCY-247 |

IBX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICc | MFCc | Antifungal | MICc | MFCc | Antifungal | |

| Activity | Activity | |||||

| 35364Am,M | 0.125 | 1 | Static | 0.125 | 1 | Static |

| 35366Am,M | 0.25 | 1 | Cidal | 0.5 | 1 | Cidal |

| 35367Am,F,M | 0.5 | 1 | Cidal | 0.25 | 2 | Static |

| 35368Am,C,F,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 8 | Static |

| 35370Am, F,M | 0.5 | 8 | Static | 0.5 | 8 | Static |

| 35371Am,F,M | 0.5 | 8 | Static | 0.5 | 8 | Static |

| 35372Am,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 2 | Static |

| 35373Am,C,F,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35374Am,C,F,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35375Am,F,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35376Am,M | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal |

| 35377Am,C,M | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 2 | Static |

| 35378C,M | 1 | 4 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 35379Am | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal |

| 35645 | 0.125 | 0.5 | Cidal | 0.125 | 2 | Static |

| 35646C,F | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35647F,V | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 35648Am,F,V | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 35649Am,F,V | 0.25 | 2 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35650Am,F,V | 0.25 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 35651C,F | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 35652Am,C,F,V | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 1 | Cidal |

| 35653An,C,F,V | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 8 | Static |

| 35654An,F,V | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 37101Am | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 37102Am | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 37103Am | 0.25 | 2 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 37104Am | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 37432 | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 37433 | 0.25 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 37434 | 0.25 | 2 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 38684 | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 38883Am | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39307Am | 1 | 4 | Cidal | 2 | 8 | Cidal |

| 39308 | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39309 | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 39414Am | 0.25 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39415F | 0.125 | 2 | Static | 0.25 | 1 | Cidal |

| 39416Am,C,M,F,V | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39417AmF | 0.5 | 2 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39418AmF | 1 | 4 | Cidal | 0.5 | 4 | Static |

| 39419Am,C,F,V | 0.5 | 4 | Static | 0.25 | 4 | Static |

| 39420Am,F,V | 0.25 | 4 | Static | 0.5 | 8 | Static |

| 41527 | 0.06 | 0.5 | Static | 0.06 | 0.25 | Cidal |

n = 44.

Am, amphotericin B; An, anidulafungin; C, caspofungin; F, fluconazole; M, micafungin; V, voriconazole.

µg/ml.

Effect of synthetic urine on the antifungal activity of SCY-247 on C. albicans and C. glabrata.

The MIC values for SCY-247 against C. albicans and C. glabrata isolates at 50% growth inhibition showed no significant change in the presence of SU (Tables 9 and 10). Compared with the MIC values for SCY-247 in the presence of SU, the MIC values for SCY-247 against both C. albicans and C. glabrata isolates tested in RPMI media were within 2 dilutions, which is considered within the normal variation of MIC testing. Therefore, we did not observe a pH effect on MIC activity for SCY-247.

TABLE 9.

MIC values for SCY-247 against the C. albicans isolates tested at 50% growth inhibition at neutral pH

| Organism | Isolate identifier | SCY-247 50% endpoint (µg/ml) in presence of: |

Δ in MIC (dilution) | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | SUa | ||||

| C. albicans | 38382 | 0.125 | 0.06 | −1 | NVb |

| C. albicans | 38397 | 0.125 | 0.125 | No change | NV |

| C. albicans | 38404 | 0.125 | 0.06 | −1 | NV |

| C. albicans | 38405 | 0.125 | 0.06 | −1 | NV |

| C. albicans | 38406 | 0.25 | 0.06 | −1 | NV |

SU, synthetic urine.

NV, within the normal day to day variation of MIC testing.

TABLE 10.

MIC values for SCY-247 against the C. glabrata isolates tested at 50% growth inhibition

| Organism | Isolate identifier | SCY-247 50% endpoint (µg/ml) in presence of: |

Δ in MIC (dilution) | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI | SUa | ||||

| C. glabrata | 32075 | 0.125 | 0.03 | −2 | NVb |

| C. glabrata | 32232 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −1 | NV |

| C. glabrata | 34870 | 0.125 | 0.03 | −2 | NV |

| C. glabrata | 34901 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −1 | NV |

| C. glabrata | 35164 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −1 | NV |

SU, synthetic urine.

NV, within the normal day to day variation of MIC testing.

Time-kill kinetic study.

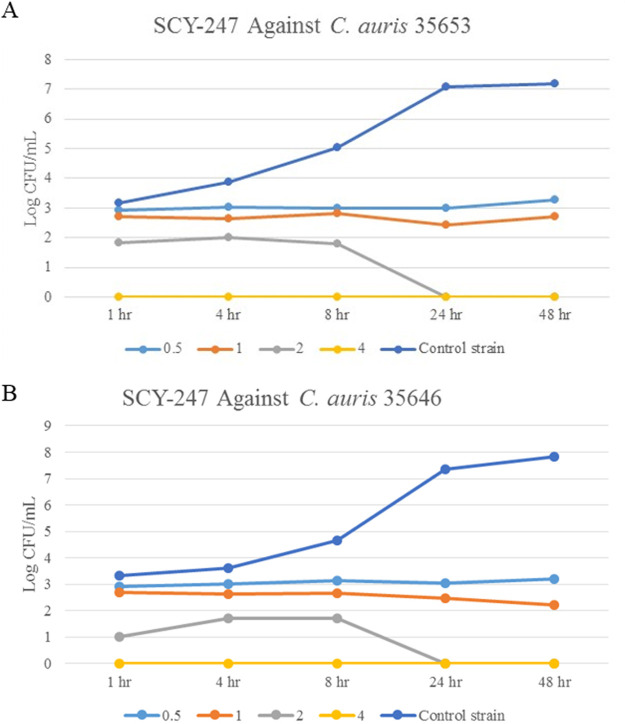

SCY-247 showed a reduction in the log CFU/ml of C. albicans strains 11036 and 27884 at all concentrations and time points compared with the growth control (Fig. 1A and B). After 1 h of exposure to SCY-247, the growth of C. albicans 11036 was reduced to zero at SCY-247 concentrations of 2, 4, and 8 µg/ml, respectively. SCY-247 demonstrated fungicidal properties against C. albicans 27884 at all concentrations. Additionally, the growth of C. albicans 27884 in the presence of SCY-247 at all concentrations continued to decrease over time. An untreated growth control was included as a comparator to SCY-247 for all fungal species.

FIG 1.

Growth of over 48 hours of C. albicans 11036 when exposed to SCY-247 at 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/ml (A) and C. albicans 27884 when exposed to SCY-247 at 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/ml (B).

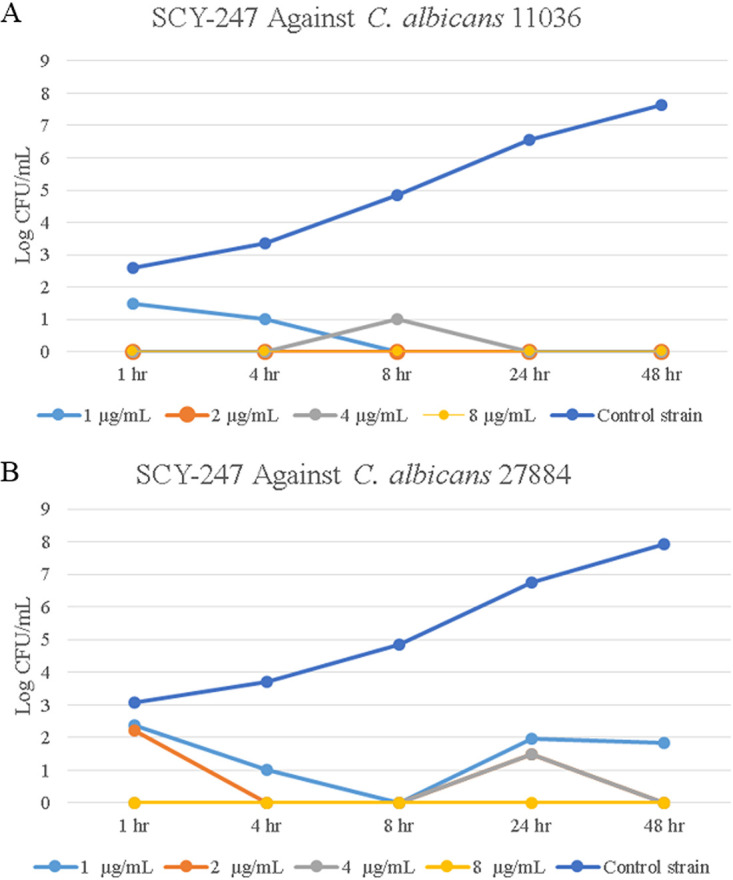

SCY-247 reduced the log CFU/ml of both C. auris 35653 and 35646 strains at all concentrations and time periods compared with the untreated growth control (Fig. 2A and B). After 1 h of exposure to SCY-247, both C. auris species showed no growth, demonstrating fungicidal activity.

FIG 2.

Growth of over 48 hours of C. auris 35653 when exposed to SCY-247 at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 µg/ml (A) and C. auris 35646 when exposed to SCY-247 at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 µg/ml (B).

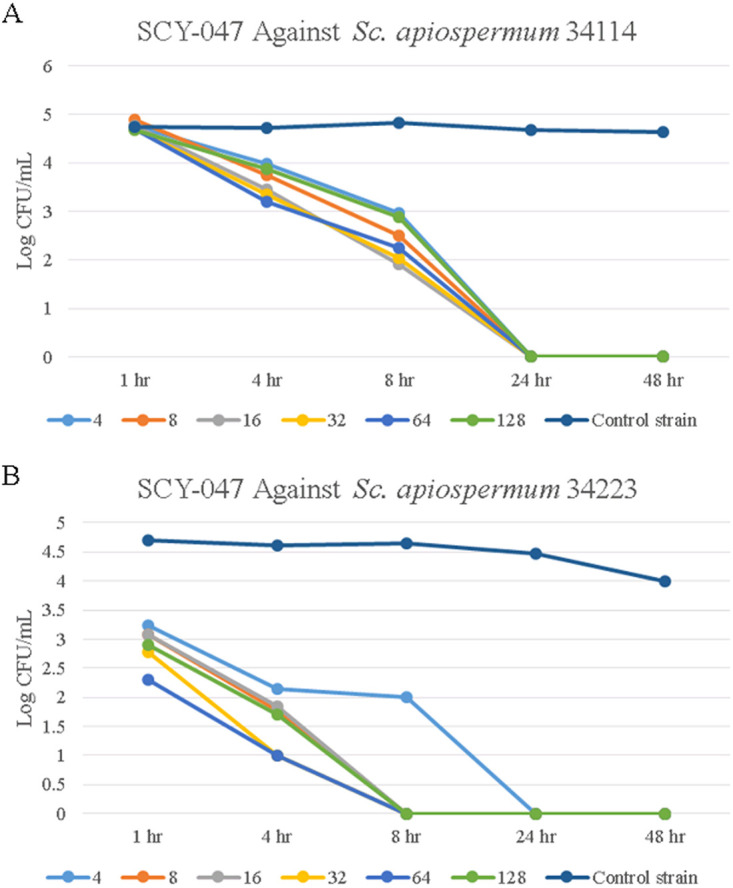

Against the Scedosporium apiospermum 34114 strain, SCY-247 reduced the log CFU/ml at all concentrations and time points tested compared with the control and showed fungicidal activity after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 3A). SCY-247 treatment of S. apiospermum 34223 reduced the log CFU/ml of isolates and was fungicidal after 8 hours at concentrations of 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 µg/ml (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Growth of over 48 hours of S. apiospermum 34114 when exposed to SCY-247 at 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 µg/ml (A) and S. apiospermum 34223 when exposed to SCY-247 at 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 µg/ml (B).

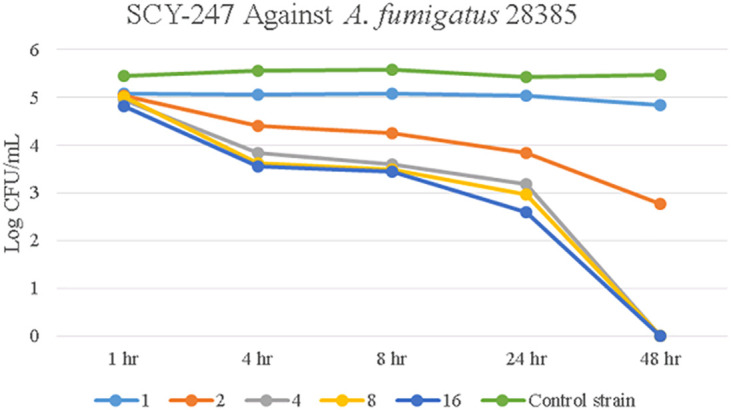

Time-kill data for A. fumigatus 28385 treated with SCY-247 is shown in Fig. 4. Treatment of this strain showed larger reductions in CFU/ml at every SCY-247 concentration tested than those of the control strain. After 48 hours of incubation, SCY-247 showed fungicidal activity at concentrations of 4, 8, and 16 µg/ml.

FIG 4.

Growth of over 48 hours of A. fumigatus 28385 when exposed to SCY-247 at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 µg/ml.

DISCUSSION

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among transplant and other immunocompromised patients, as well as those with extensive stays in intensive care units or undergoing extensive intra-abdominal surgeries. Despite a wide availability of newer classes of antifungals, IFIs are still common and mostly caused by Candida and Aspergillus species (10). Furthermore, IFI mortality rate is high (30% to 50%), especially in non-Aspergillus mold infections (18, 19). To address the need for novel effective antifungal agents to prevent IFIs, new analogs of IBX are currently being developed and tested against a broad spectrum of fungal species.

Our results show that the analog of ibrexafungerp SCY-247 has potent and broad-spectrum antifungal activity, as demonstrated by similar MIC and MFC values compared with those of IBX against a panel of clinically relevant yeast and molds. SCY-247 showed fungicidal activity against a large percentage of the yeast isolates tested (88%). However, both SCY-247 and IBX demonstrated mostly fungistatic activity against mold isolates, with MIC values lower against Aspergillus strains than those of the Fusarium, Scedosporium, Acremonium, Fonsecaea, Paecilomyces, Pseudallescheria, Rhizopus, and Trichoderma strains tested. Interestingly, SCY-247 demonstrated a higher percentage of cidality than IBX against this panel of yeast and mold isolates (88% and 44%, respectively).

Our findings further demonstrated that the 50% MIC endpoint for SCY-247 against C. albicans and C. glabrata had no significant change in the presence of SU. This result suggests that SCY-247 is able to retain activity and structural stability against Candida species in the presence of SU that mimics the composition of urine and an environment with decreased pH levels, highlighting its potential effectiveness in fungal UTIs.

We further studied the in vitro activity of SCY-247 against strains of C. albicans, C. auris, S. apiospermum, and A. fumigatus. The time-kill curve study demonstrated that SCY-247 killed all fungi isolates tested (two C. albicans, two C. auris, two S. apiospermum, and one A. fumigatus) at various concentrations. High drug concentrations typically led to quicker fungicidal effects, except in S. apiospermum 34114. In S. apiospermum 34114 isolates, IBX showed a concentration-independent reduction in CFU/ml, as all concentrations tested showed an equivalent ability to inhibit growth. Our data suggest that SCY-247 has concentration- and time-dependent effects against different fungal species. Furthermore, SCY-247 shows broad-spectrum activity against yeasts and molds, as evidenced by its fungicidal activity against various strains of Candida, Scedosporium, and Aspergillus.

Given the numerous reports demonstrating the high resistance of C. auris to several antifungal agents, we chose to expand our cohort of C. auris isolates to include numerous clinical isolates previously demonstrated to be highly resistant to antifungals. SCY-247 showed elevated cidal activity against more C. auris strains than IBX, wherein cidal activity was observed against 14 versus 7 tested strains, respectively.

Echinocandins have been shown to be fungicidal in vitro and in vivo against most isolates of Candida species, especially of C. albicans (20, 21). In contrast, echinocandins show largely fungistatic properties against filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus, being unable to completely inhibit growth (22, 23). IBX, a first-in-class glucan synthase inhibitor, was developed in order to target both echinocandin-susceptible and echinocandin-resistant fungal species, as unlike echinocandins, IBX antifungals are not inhibited by most common mutations occurring within the protein target Fks (24). IBX has shown in vitro and in vivo effectiveness against Candida and Aspergillus species, including azole-resistant and echinocandin-resistant strains (24–28). SCY-247 has a lower molecular weight than IBX, which may contribute to an improved profile with central nervous system penetration and suitability for effective and simple IV formulation.

In summary, our study demonstrates promising fungicidal properties of SCY-247. We showed that SCY-247 is a potent antifungal drug that could be an important addition to the repertoire of therapies to combat drug-resistant fungal infections. This is especially true for C. auris strains wherein high levels of resistance exhibited by this species of Candida have been a very problematic occurrence in health care facilities. The parent drug IBX has shown additive effects in combination with azoles, echinocandins, and amphotericin B versus Candida species and synergy in combination with azoles versus Aspergillus species (26, 29). Thus, larger in vitro and combination studies with this second-generation fungerp seem warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Minimum inhibitory concentration.

MIC testing was performed according to the CLSI M27-A3 and M38-A2 standards for the susceptibility testing of yeasts and filamentous fungi, respectively (17, 30). For yeast isolates, incubation temperature and time were 35°C and 24 hours, respectively, and the inoculum size was 0.5 to 2.5 × 103 CFU/ml. For filamentous fungi, incubation times at 35°C were 24, 48, or 72 hours, and the inoculum size was 0.4 to 5 × 104 conidia/ml. RPMI was used throughout as the growth medium with the exception of Cryptococcus species, for which yeast nitrogen base (YNB) was used as described previously by Ghannoum et al., and the CLSI M27-A3 document (17, 31). The MIC endpoints were 50% and 100% inhibition compared with the growth control for yeasts, and MEC endpoints were used for molds, when available. The initial MIC range tested was 0.016 to 8 μg/ml; the range was increased to 0.125 to 64 μg/ml where needed to capture the MIC and MFC endpoints.

Antifungal susceptibility tests against Coccidioides sp. and Histoplasma capsulatum were performed using a broth macrodilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M38-A2 standard. Isolates were adjusted by a spectrophotometer (80% to 82% transmittance) to a starting inoculum of 1 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells/ml and then added to tubes containing serial 2-fold dilutions of the antifungal agents (0.125 to 64 μg/ml). The assay was conducted in RPMI medium. The cultures were incubated at 35°C for 48 hours for Coccidioides sp. and at 30°C for 168 hours for Histoplasma capsulatum. MEC endpoints were used for evaluation.

Minimum Fungicidal Concentration.

The MFC of SCY-247 was determined against the selected isolates tested above. Briefly, MFC determinations were performed according to the method previously described by Ghannoum and Isham (32). Specifically, the total contents of each clear well from the MIC assay were subcultured onto potato dextrose agar. To avoid antifungal carryover, aliquots were allowed to soak into the agar and then streaked for isolation once dry, thus removing the cells from the drug source. Petri dishes were incubated at 35°C for 48 hours, and the number of CFUs was determined. Fungicidal activity was defined as a ≥99.9% reduction in the number of CFUs from the starting inoculum count occurring within 4 dilutions of the MIC endpoint.

Effects of urine on SCY-247 antifungal activity.

Five strains each of C. albicans and C. glabrata isolates were used to evaluate the effect of the addition of synthetic urine (SU) on the antifungal activity of SCY-247. Antifungal activity was assessed by determining the MIC according to the CLSI M27-A4 standard for Candida susceptibility testing. Incubation temperature and time were 35°C and 24 h, respectively, and the inoculum was 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 CFUs/ml. MIC determination was performed using SU medium, which consisted of CaCl2 (0.65 g/liter), MgCl2 (0.65 g/liter), NaCl (4.6 g/liter), Na2SO4 (2.3 g/liter), Na3-citrate (0.65 g/liter), Na2-oxalate (0.02 g/liter), KH2PO4 (2.8 g/liter), KCl (1.6 g/liter), NH4Cl (1.0 g/liter), urea (25.0 g/liter), creatinine (1.1 g/liter), 5% yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium (vol/vol), and 2% glucose (wt/vol). The pH was adjusted to 6.0, and the medium was filter sterilized by passing it through a 0.22-μm-pore filter. MIC determination was also performed in RPMI 1640 medium (pH of 7.0) for comparison. The MIC endpoints were 50% and 100% inhibition compared with the growth control.

Time-kill kinetics of SCY-247.

Two strains of C. albicans and C. auris, four strains of S. apiospermum, and three strains of A. fumigatus were utilized to analyze the time-kill kinetics of SCY-247. Fungal cells were inoculated overnight in Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB) at 37°C. Cells were harvested the following day, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), adjusted to 1 × 105 cells/ml, and suspended in 10 ml of SDB media containing 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, or 128 µg/ml of SCY-247. Tubes with the cells and SCY-247 were incubated for 1, 4, 8, 24, or 48 hours at 37°C. A sample tube with no drug served as a control. At each time point, 100-µl aliquots from each tube were removed, diluted serially with PBS, and spread onto Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) plates. CFUs were determined following 48 hours (yeast) or 2 to 4 days (molds) of incubation at 35°C. Results were calculated as log CFU/ml for each isolate and plotted against drug concentrations for predetermined time points to obtain the time-kill curve. To test the Candida strains, four concentrations for SCY-247 were chosen based on minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) (0.0625×, 0.25×, 0.5×, and 1× MFC), resulting in different concentrations of SCY-247 being compared. Testing for the Scedosporium and Aspergillus isolates was conducted using equivalent concentrations that included the MFC values for both agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Scynexis, Inc., and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH grant no. R21 AI143305-01).

In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, we declare the following financial relationships: K.B.-E. and S.B. are employees of Scynexis, Inc. who manufactures and commercializes ibrexafungerp; and M.A.G. a consultation role for Scynexis, Inc. All other authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Denning DW. 2003. Echinocandin antifungal drugs. Lancet 362:1142–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman C, Akiyama MJ, Torres J, Louie E, Meehan SA. 2016. Scedosporium apiospermum infections and the role of combination antifungal therapy and GM-CSF: a case report and review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep 11:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyn K, Tredup A, Salvenmoser S, Müller FM. 2005. Effect of voriconazole combined with micafungin against Candida, Aspergillus, and Scedosporium spp. and Fusarium solani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:5157–5159. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5157-5159.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Lockhart SR, Ahlquist AM, Messer SA, Jones RN. 2012. Frequency of decreased susceptibility and resistance to echinocandins among fluconazole-resistant bloodstream isolates of Candida glabrata. J Clin Microbiol 50:1199–1203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06112-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiménez-Ortigosa C, Paderu P, Motyl MR, Perlin DS. 2014. Enfumafungin derivative MK-3118 shows increased in vitro potency against clinical echinocandin-resistant Candida Species and Aspergillus species isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:1248–1251. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02145-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kordalewska M, Lee A, Park S, Berrio I, Chowdhary A, Zhao Y, Perlin DS. 2018. Understanding echinocandin resistance in the emerging pathogen Candida auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00238-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00238-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukherjee PK, Sheehan D, Puzniak L, Schlamm H, Ghannoum MA. 2011. Echinocandins: are they all the same? J Chemother 23:319–325. doi: 10.1179/joc.2011.23.6.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. 2007. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson M, Lass-Flörl C. 2008. Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 14:5–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, Hadley S, Kauffman CA, Freifeld A, Anaissie EJ, Brumble LM, Herwaldt L, Ito J, Kontoyiannis DP, Lyon GM, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Park BJ, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Oster RA, Schuster MG, Walker R, Walsh TJ, Wannemuehler KA, Chiller TM. 2010. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin Infect Dis 50:1101–1111. doi: 10.1086/651262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain S, Alexander BD, Munoz P, Avery RK, Houston S, Pruett T, Jacobs R, Dominguez EA, Tollemar JG, Baumgarten K, Yu CM, Wagener MM, Linden P, Kusne S, Singh N. 2003. Opportunistic mycelial fungal infections in organ transplant recipients: emerging importance of non-Aspergillus mycelial fungi. Clin Infect Dis 37:221–229. doi: 10.1086/375822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uenotsuchi T, Moroi Y, Urabe K, Tsuji G, Koga T, Matsuda T, Furue M. 2005. Cutaneous Scedosporium apiospermum infection in an immunocompromised patient and a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol 85:156–159. doi: 10.1080/00015550410024553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enoch DA, Ludlam HA, Brown NM. 2006. Invasive fungal infections: a review of epidemiology and management options. J Med Microbiol 55:809–818. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. 1999. Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Crit Care Med 27:887–892. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199905000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behzadi P, Behzadi E, Ranjbar R. 2015. Urinary tract infections and Candida albicans. Cent European J Urol 68:96–101. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2015.01.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scynexis Inc. 2020. Phase 3 study of oral ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) vs. placebo in subjects with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) (CANDLE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04029116?term=scynexis&draw=2.

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard—third edition. CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, Pfaller M, Chang C, Webster K, Marr K. 2009. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance registry. Clin Infect Dis 48:265–273. doi: 10.1086/595846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. 2007. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis 44:531–540. doi: 10.1086/510592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, Diekema DJ. 2006. In vitro susceptibilities of Candida spp. to caspofungin: four years of global surveillance. J Clin Microbiol 44:760–763. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.760-763.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barchiesi F, Spreghini E, Tomassetti S, Della Vittoria A, Arzeni D, Manso E, Scalise G. 2006. Effects of caspofungin against Candida guilliermondii and Candida parapsilosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2719–2727. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00111-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman JC, Abruzzo GK, Flattery AM, Gill CJ, Hickey EJ, Hsu MJ, Kahn N, Liberator PA, Misura AS, Pelak BA, Wang TC, Douglas CM. 2006. Efficacy of caspofungin against Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus nidulans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:4202–4205. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00485-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowman JC, Hicks PS, Kurtz MB, Rosen H, Schmatz DM, Liberator PA, Douglas CM. 2002. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3001–3012. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.9.3001-3012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Motyl MR, Jones RN, Castanheira M. 2013. In vitro activity of a new oral glucan synthase inhibitor (MK-3118) tested against Aspergillus spp. by CLSI and EUCAST broth microdilution methods. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1065–1068. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01588-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Rhomberg PR, Borroto-Esoda K, Castanheira M. 2017. Differential activity of the oral glucan synthase inhibitor SCY-078 against wild-type and echinocandin-resistant strains of Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00161-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00161-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghannoum M, Long L, Larkin EL, Isham N, Sherif R, Borroto-Esoda K, Barat S, Angulo D. 2018. Evaluation of the antifungal activity of the novel oral glucan synthase inhibitor SCY-078, singly and in combination, for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00244-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00244-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larkin E, Hager C, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Retuerto M, Salem I, Long L, Isham N, Kovanda L, Borroto-Esoda K, Wring S, Angulo D, Ghannoum M. 2017. The emerging pathogen Candida auris: growth phenotype, virulence factors, activity of antifungals, and effect of SCY-078, a novel glucan synthesis inhibitor, on growth morphology and biofilm formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02396-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02396-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scorneaux B, Angulo D, Borroto-Esoda K, Ghannoum M, Peel M, Wring S. 2017. SCY-078 is fungicidal against Candida species in time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01961-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01961-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borroto-Esoda K, Scorneaux B, Helou F, Angulo D. 2017. In vitro interaction between SCY-078, echinocandins and azoles against susceptible & resistant Candida spp. determined by the checkerboard method. ASM Microbe 2017, New Orleans, LA.

- 30.Rex J, Alexander B, Andes D, Arthington-Skaggs B, Brown S, Chaturveil V. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard—second edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne PA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jessup CJ, Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Zhang J, Tumberland M, Mbidde EK, Ghannoum MA. 1998. Fluconazole susceptibility testing of Cryptococcus neoformans: comparison of two broth microdilution methods and clinical correlates among isolates from Ugandan AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol 36:2874–2876. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.10.2874-2876.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghannoum M, Isham N. 2007. Voriconazole and caspofungin cidality against non-albicans Candida species. Infect Dis Clin Pract 15:250–253. [Google Scholar]