Lenacapavir (LEN; GS-6207) is a potent first-in-class inhibitor of HIV-1 capsid with long-acting properties and the potential for subcutaneous dosing every 3 months or longer. In the clinic, a single subcutaneous LEN injection (20 mg to 750 mg) in people with HIV (PWH) induced a strong antiviral response, with a >2.3 mean log10 decrease in HIV-1 RNA at day 10.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, capsid inhibitor, GS-6207, antiretroviral resistance, cross-resistance

ABSTRACT

Lenacapavir (LEN; GS-6207) is a potent first-in-class inhibitor of HIV-1 capsid with long-acting properties and the potential for subcutaneous dosing every 3 months or longer. In the clinic, a single subcutaneous LEN injection (20 mg to 750 mg) in people with HIV (PWH) induced a strong antiviral response, with a >2.3 mean log10 decrease in HIV-1 RNA at day 10. HIV-1 Gag mutations near protease (PR) cleavage sites have emerged with the use of protease inhibitors (PIs). Here, we have characterized the activity of LEN in mutants with Gag cleavage site mutations (GCSMs) and mutants resistant to other drug classes. HIV mutations were inserted into the pXXLAI clone, and the resulting mutants (n = 70) were evaluated using a 5-day antiviral assay. LEN EC50 fold change versus the wild type ranged from 0.4 to 1.9 in these mutants, similar to that for the control drug. In contrast, reduced susceptibility to PIs and maturation inhibitors (MIs) was observed. Testing of isolates with resistance against the 4 main classes of drugs (n = 40) indicated wild-type susceptibility to LEN (fold change ranging from 0.3 to 1.1), while reduced susceptibility was observed for control drugs. HIV GCSMs did not impact the activity of LEN, while some conferred resistance to MIs and PIs. Similarly, LEN activity was not affected by naturally occurring variations in HIV Gag, in contrast to the reduced susceptibility observed for MIs. Finally, the activity of LEN was not affected by the presence of resistance mutations to the 4 main antiretroviral (ARV) drug classes. These data support the evaluation of LEN in PWH with multiclass resistance.

INTRODUCTION

The HIV capsid protein (CA; p24) is a component of the HIV group-specific antigen (Gag) polyprotein, which plays a key role in the HIV life cycle. Upon cleavage of Gag or Gag-Pol polyprotein by HIV protease within the immature virion, HIV structural proteins such as matrix (MA), capsid (CA), and nucleocapsid (NC) are released and participate in the maturation of virions (reviewed in reference 1). Proper multimerization of the HIV capsid protein into 250 hexamers and 12 pentamers is a key step in the formation of the cone-shaped capsid core associated with viral infectivity. HIV capsid also plays an important role in the early stages of the viral cycle, where upon infection of a target cell, the controlled disassembly of the capsid, which is tightly regulated by interactions with host factors, must take place (2). Disruption of any of these steps can potentially lead to an antiviral effect. As a result, HIV capsid has been considered an attractive target for the development of novel antiretrovirals (3). Such a new class of antiviral compounds targeting HIV-1 capsid was recently described (4), showing that a small molecule binding directly to HIV-1 capsid and interfering with capsid-mediated nuclear import, particle production, and capsid assembly could be developed.

More recently, proof-of-concept inhibition of HIV capsid function by the novel small molecule GS-6207 was demonstrated, both in vitro and in vivo (5). Lenacapavir (LEN; GS-6207) exhibited a multistage mode of action with picomolar potency, with a mean reduction in HIV-1 RNA viral load of 2.3 log10 9 days after subcutaneous injection of 450 mg of LEN (5). The physicochemical properties of LEN (picomolar antiviral potency, low predicted clearance, and low aqueous solubility) make the compound suitable as a long-acting agent with infrequent dosing.

The potential for resistance emergence using LEN was characterized through in vitro resistance selection experiments, which identified several variants in the CA portion of Gag (L56I, M66I, Q67H, K70N, N74D/S, and T107N) associated with reduced susceptibility to LEN coupled with reduced viral fitness (5). In a recent study, none of these mutations were found in samples from 1,500 people with HIV (PWH) spanning multiple HIV-1 subtypes, whether these samples were from treatment-naive or treatment-experienced PWH with or without prior use of protease inhibitors (PI) (6).

Other mutations in HIV Gag have been shown to be associated with various levels of resistance against protease inhibitors (PIs) (reviewed in reference 7) as well as against maturation inhibitors (MIs) (8–10). For PIs, antiretroviral treatment (ART) and/or in vitro resistance selections have been associated with the emergence of mutations in the vicinity of Gag cleavage sites within the Gag or Gag-Pol polyprotein protease substrate, particularly at the SP1/NC and NC/SP2 Gag cleavage sites (11–13). Altogether, these authors and others identified HIV Gag mutations that played a role in PI resistance with or without resistance mutations in HIV protease and compensated for the reduced fitness of PI-resistant mutants; these substitutions in Gag included Q430R, A431V, K436E, I437V/T, L449F, and P453L (7, 14–16). Other Gag mutations at non-cleavage sites have also been reported in the course of resistance selection experiments with PIs (L75R, H219Q, V390D/A, R409K, and E468K) (17). For MIs, the presence of naturally occurring Gag polymorphisms has also been reported to confer resistance to betulinic acid derivatives, such as bevirimat (BVM), which inhibit the last cleavage of Gag (CA/SP1 cleavage site) (8–10). Some of these naturally occurring BVM-associated resistance substitutions include the V362I mutation as well as polymorphisms at residues 369 to 371 within SP1 (8, 18). Resistance selection against BVM has led to the emergence of resistance mutations at the CA/SP1 cleavage site (L363F/M, A364V, and A366T/V) (10), which is also the location of the naturally occurring V362I substitution.

As LEN targets the capsid component of the Gag polyprotein, we aimed to characterize the susceptibility to LEN in HIV isolates harboring Gag mutations, including Gag cleavage site mutations (GCSM) and naturally occurring substitutions in Gag. Additionally, we characterized the resistance profile of LEN in mutants with resistance mutations to the four main drug classes (protease inhibitors [PIs], nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTIs], non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs], and integrated strand transfer inhibitors [INSTIs]).

(Presented in part at the European AIDS Clinical Society [EACS] conference, 6 to 9 November 2019, Basel, Switzerland, and at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections [CROI], 8 to 11 March 2020, Boston, MA.)

RESULTS

Characterization of the antiviral activity of the capsid inhibitor LEN was conducted in a series of in vitro phenotypic assays using viruses with treatment-induced or naturally occurring resistance mutations, including mutations in HIV Gag.

Antiviral activity of LEN against viruses with resistance to the 4 main drug classes.

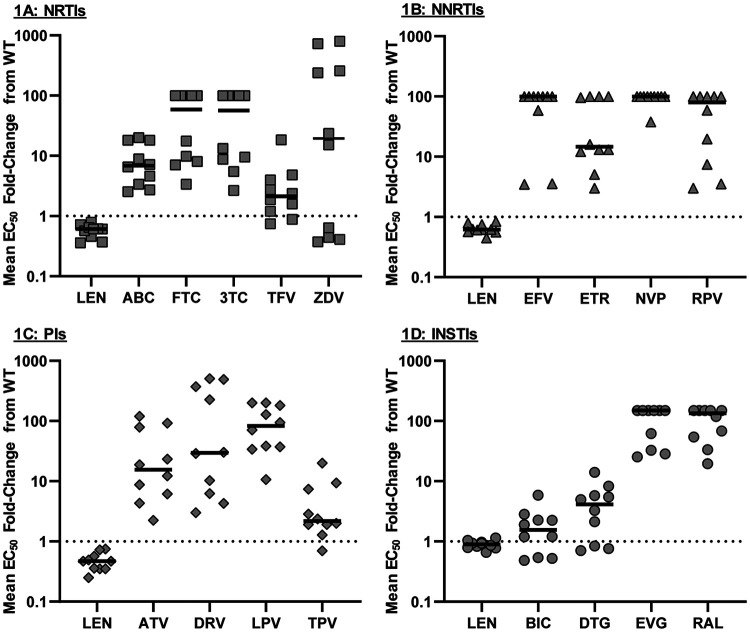

The antiviral activity of LEN was tested in 40 viral isolates with resistance to at least one of the 4 main antiretroviral (ARV) drug classes (NRTIs, NNRTIs, PIs, INSTIs) using the publicly available PhenoSense single-cycle assay. In that assay, the HIV-1 protease and reverse transcriptase (RT) (up to RT amino acid 305) or integrase fragment from patient samples is inserted in the otherwise wild-type HIV test vector. No change in phenotypic susceptibility to LEN was observed in this panel of mutants (Fig. 1), with an average fold change of 0.65 across all 40 mutants (ranging from 0.25 to 1.1) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) in comparison to that of the wild type. In contrast, the activity of control compounds within each class was markedly diminished in most isolates, reflecting the presence of resistance mutations in these isolates (Table S1). These data indicate that the antiviral activity of LEN was not affected by the presence of resistance mutations in HIV-1 protease, RT, and integrase in this standard commercial assay, further indicating the absence of cross-resistance to LEN in these highly resistant isolates.

FIG 1.

Drug susceptibilities in HIV-1 isolates with resistance mutations to the 4 main ARV drug classes. Ten mutants with resistance to each of the 4 main drug classes were analyzed: NRTIs (A), NNRTIs (B), PIs (C), and INSTIs (D). Resistance-associated mutations found in each mutant are indicated in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Each point represents a single isolate tested singly (PhenoSense GT or PhenoSense IN CLIA-validated assays). The black lines indicate the median EC50 fold change for each drug. NRTI, nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor.

Phenotypic susceptibility to LEN in HIV isolates from treatment-naive and treatment-experienced PWH.

As LEN targets the capsid protein within HIV-1 Gag, which is itself the substrate for HIV-1 PR, we sought to analyze the antiviral activity of LEN in its natural context using isolates containing the whole HIV-1 gag-pro segment from PWH (either treatment naive [TN] or treatment experienced [TE]). We generated 51 patient-derived isolates (15 from TN people and 36 from TE people) that we analyzed in a 5-day multicycle antiviral assay in MT-2 cells.

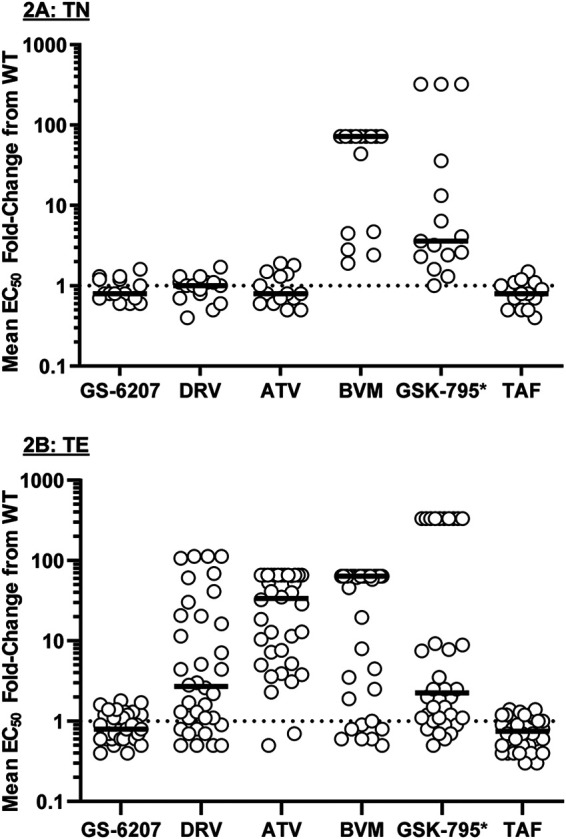

Across the 15 TN isolates, susceptibility to LEN was unchanged compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 2A), with a median fold change of 0.8 in comparison to that of the wild type and limited variability (fold change [FC] ranging from 0.6 to 1.6) (Table 1). Similarly, susceptibility to the PIs darunavir (DRV) and atazanavir (ATV) for these TN isolates was unchanged compared to that of the wild type, with median FCs of 1.0 and 0.8, respectively, compared to the wild type and limited variability across isolates (Table 1). These data reflect the absence of resistance-associated mutations to LEN, DRV, and ATV in these HIV isolates from TN PWH, which is on par with the lack of resistance observed for the NRTI control compound (tenofovir alafenamide [TAF], with median FC of 0.9 in comparison to the wild type) in the context of the wild-type RT sequence in these isolates (HIV-1LAI background). In contrast, susceptibility to the maturation inhibitors (MI) BVM and GSK-795 was reduced in these TN isolates (median FCs of >64 and 3.7, respectively) (Table 1), reflecting the presence of naturally existing Gag polymorphisms known to affect the MI class of compounds. Overall, these data indicate that the antiviral activity of LEN is not altered in the presence of naturally existing Gag polymorphisms.

FIG 2.

Drug susceptibilities in treatment-naive (TN) HIV-1 isolates (n = 15) (A) and treatment-experienced (TE) HIV-1 isolates (n = 36) (B). Each symbol represents a single isolate. The black lines indicate the median EC50 fold change for each drug. *, GSK-3532795/BMS-955176; CAI, capsid inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; MI, maturation inhibitor; NRTI, nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Data are from n ≥ 3, conducted in triplicates.

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibility summary of treatment-naive and treatment-experienced HIV isolates

| Isolate typea | Drug susceptibility (median EC50 fold change from wild type and range)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-6207 (CAI) | DRV (PI) | ATV (PI) | BVM (MI) | GSK-795c (MI) | TAF (NRTI) | |

| TN (n = 15) | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | >64 | 3.7 | 0.9 |

| 0.6 to 1.6 | 0.5 to 1.8 | 0.5 to 1.9 | 1.7 to >64 | 1.1 to >333 | 0.5 to 1.5 | |

| TE (n = 36) | 0.8 | 2.7 | 34 | >64 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| 0.4 to 1.8 | 0.5 to >112 | 0.5 to >66 | 0.5 to >64 | 0.5 to >333 | 0.3 to 14 | |

TE, treatment experienced; TN, treatment naive.

CAI, capsid inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; MI, maturation inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Average EC50s for the wild-type control were 0.095, 4.5, 6.1, 63, 6.0, and 12.3 nM for GS-6207, DRV, ATV, BVM, GSK-795, and TAF, respectively. Data are from n ≥ 3, performed in triplicates.

GSK-3532795/BMS-955176.

Similarly, as with TN isolates, susceptibility to LEN in TE isolates was essentially unchanged in comparison to that of the wild type, with a median FC of 0.8 and low variability across the 36 isolates (Fig. 2B; Table 1). However, reduced susceptibility to the PIs DRV and ATV was observed in the TE isolates (median FCs of 2.7 and 33.8, respectively, in comparison to the wild type) (Table 1), which was consistent with the presence of PI resistance mutations in these TE isolates. Susceptibility to the MI control compounds was similarly reduced as with TN isolates (median FCs of >64 and 2.3 for BVM and GSK-795, respectively) (Table 1), again reflecting the presence of naturally occurring amino acid substitutions in Gag known to affect MI compounds. Susceptibility to the NRTI control compound TAF remained at the wild-type level in TE isolates as expected, reflecting the wild-type RT sequence present in these TE isolates (HIV-1LAI background). Overall, these TN and TE data indicate that the antiviral activity of LEN was unchanged in comparison to that for the wild type, regardless of the presence of PI resistance mutations and/or natural amino acid variations in Gag.

Phenotypic susceptibility of LEN in the presence of GCSMs.

The use of PIs for the treatment of HIV has led to the emergence of PI-associated resistance mutations near the cleavage sites of the Gag substrate (7, 15, 16). As LEN is a direct inhibitor of the capsid protein, which is itself a product of Gag polyprotein processing by HIV protease, we investigated whether the presence of Gag cleavage site mutations (GCSMs) in HIV mutants influenced the phenotypic susceptibility to LEN.

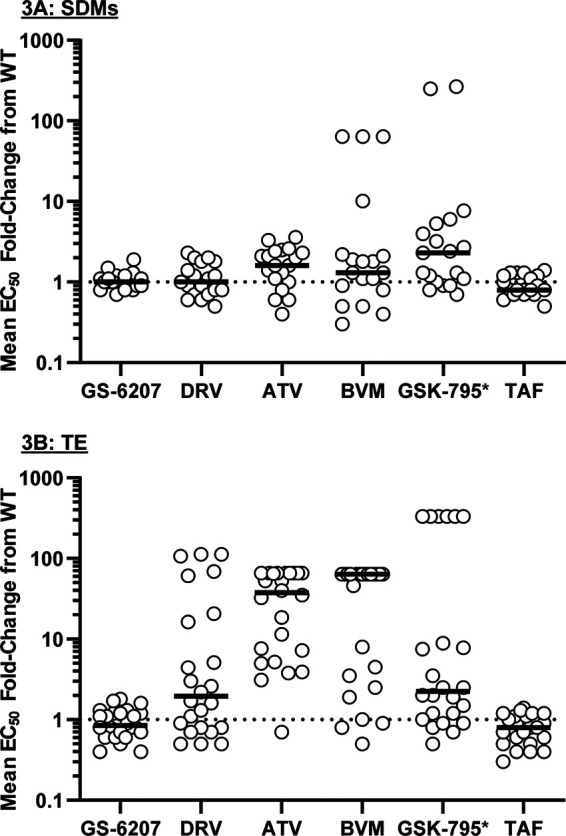

We generated site-directed mutants (SDMs; n = 19) containing either common PI-associated GCSMs (Q430R, A431V, K436E/S, I437T/V, L449H/V/F, and P453L) (7, 15, 16) with or without the PI resistance mutations V82A or I84V (n = 16) or MI-associated GCSMs (n = 3) (L363F/M and A364V) (10) (see Materials and Methods, Table 2, and Table S2) and analyzed their drug susceptibility. LEN showed near wild-type (WT) potency (average EC50 of 102 pM compared to WT EC50 of 95 pM) (data not shown), with limited variability across all 19 mutants, with FCs from WT ranging from 0.7 to 1.9 (Fig. 3A; Table 3). Statistically significant fold changes (FCs) from WT were noted in 2 mutants (FCs of 1.5 [number 104, PI-associated GCSM] and 1.9 [number 107, MI-associated GCSM]; P < 0.05, unpaired t test) (Table S2). Addition of either the V82A or I84V PI resistance mutations to GCSM SDMs did not have a significant impact on LEN susceptibility (Table S2). Reduced susceptibility (FC > 5-fold) to the maturation inhibitors BVM and GSK-3532795 was seen in 4 and 6 of 19 SDM viruses tested, respectively (Fig. 3A; Tables 3; Table S3). Susceptibility was most reduced in mutants with MI-associated GCSMs at positions 363 and 364 (CA/SP1 cleavage site mutations), as previously observed (10, 19), while reduced susceptibility to both MI compounds was also observed for the double mutant K436E plus I437T. Low-level reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitors ATV and DRV was noted in a few viruses with GCSMs, the highest observed with the K436E plus I437T mutant at 2.3- and 3.6-fold above that of the WT for DRV and ATV, respectively (Fig. 3A; Table 3; Table S2). Of note, ATV susceptibility was mildly reduced (2.4- to 3.3-fold) in mutants with MI-associated GCSMs. While many PI-associated GCSMs retained similar resistance patterns with the addition of either the V82A or the I84V protease mutation, the effect of these mutations varied (Table S2). Reduced susceptibility to GSK-3532795 was seen with A431V alone (FC = 7.7), and the addition of V82A or I84V reverted the potency to WT levels. None of the mutants displayed reduced susceptibility to the control NRTI (TAF), reflective of the WT RT sequence in the SDMs. Overall, these data indicate that LEN susceptibility is not affected by the presence of GCSMs in the SDM viruses tested here.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Gag cleavage site mutations in HIV-1 isolates

| Isolate typea | No. of isolates with Gag cleavage site mutation:b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L363F/M | A364V | Q430R | A431V | K436E/S | I437T/V | L449H/V/F | P453L | |

| SDM (n = 19) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| TN (n = 15) | —c | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| TE (n = 36)d | — | — | — | 13 | — | 5 | 5 | 11 |

SDM, site-directed mutants; TE, treatment experienced (same isolates as is in Fig. 2A); TN, treatment naive (same isolates as is in Fig. 2B).

Mutations L363F/M and A364V are CA/SP1 cleavage site mutations, mutations Q430R, A431V, K436E/S, and I437T/V are NC/SP2 cleavage site mutations, and mutations L449H/V/F, and P453L are SP2/P6 cleavage site mutations.

—, none.

The 36 TE isolates comprised 24 isolates with gag cleavage site mutations (GCSM) and 12 isolates without GCSM. EC50 summary for the 24 isolates is presented in Table 3 (detailed list provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 3.

Drug susceptibilities in site-directed mutant HIV-1 isolates (n = 19) (A) and treatment-experienced HIV-1 isolates (n = 24) (B) with Gag cleavage site mutations. Each symbol represents a single isolate. The black lines indicate the median EC50 fold change for each drug. *, GSK-3532795/BMS-955176; CAI, capsid inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; MI, maturation inhibitor; NRTI, nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Data are from n ≥ 3, conducted in triplicates.

TABLE 3.

Drug susceptibility summary in isolates with GCSMs

| Isolate typea | Drug susceptibility (median EC50 fold change from wild type and range)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-6207 (CAI) | DRV (PI) | ATV (PI) | BVM (MI) | GSK-795c (MI) | TAF (NRTI) | |

| SDM (n = 19) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.8 |

| 0.7 to 1.9 | 0.5 to 2.3 | 0.4 to 3.6 | 0.3 to >64 | 0.7 to 267 | 0.5 to 1.4 | |

| TE (n = 24) | 0.8 | 1.9 | 38 | >64 | 2.3 | 0.8 |

| 0.4 to 1.8 | 0.5 to >112 | 0.7 to >66 | 0.5 to >64 | 0.5 to >333 | 0.3 to 1.4 | |

SDM, site-directed mutant; TE, treatment experienced.

CAI, capsid inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; MI, maturation inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Average EC50s for the wild-type control were 0.095, 4.5, 6.1, 63, 6.0, and 12.3 nM for GS-6207, DRV, ATV, BVM, GSK-795, and TAF, respectively. Data are from n ≥ 3, performed in triplicates.

GSK-3532795/BMS-955176.

In addition, the analysis of the Gag sequence from the TE and TN patient isolates (Table 2) indicated that 24 of the 36 TE isolates contained GCSMs, while none of the TN isolates harbored GCSMs (Table 2). The most prevalent GCSMs in the TE isolates were A431V (NC/SP2 cleavage site; present in 13 of 24) and P453L (SP2/P6 cleavage site; present in 11 of 24) alone or in combination with other GCSMs. None of the isolates had mutations at MI-associated positions 363 and 364 of Gag (CA/SP1 cleavage site).

As with SDMs, LEN displayed high potency (mean 50% effective concentration [EC50] of 91 pM compared to WT EC50 of 95 pM) (data not shown) with minimal variability across all 24 TE isolates with GCSMs (Fig. 3B; Table 3; Table S2), similar to the antiviral activity of LEN in isolates without GCSMs (mean EC50 = 80 pM) (data not shown). Statistically significant LEN FCs from WT (P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test) ranging from 0.4 to 1.8 were noted in 7 TE isolates with GCSMs, 5 of them with an FC of ≤0.6 (Table S2). Of note, 5 isolates (4 TE and 1 TN) also harbored the V362I Gag mutation at the CA/SP1 cleavage site, with no effect on LEN susceptibility (mean EC50 = 79 pM) (data not shown). Overall, these data indicate that the susceptibility to LEN was not affected by the presence of GCSMs in the context of complex and diverse genetic makeups present in these patient isolates.

Finally, resistance to the PIs darunavir (DRV) and atazanavir (ATV) was elevated in these TE isolates (Fig. 3B; Table 3; Table S2), with median fold change EC50s greater than the WT value at 1.9 and 38, respectively, reflective of the presence of complex patterns of PI resistance mutations in these isolates. The maturation inhibitors, BVM and GSK-3532795, showed reduced potency in these TE isolates, reflecting the occurrence of naturally existing Gag polymorphisms known to affect the activity of the MI class (Fig. 3B; Table 3; Table S2). No meaningful change in EC50 was noted for the NRTI control TAF (median FC of 0.8 compared to the WT value), consistent with the WT RT in these isolates (pXXLAI background).

DISCUSSION

We have conducted phenotypic analyses to study the effect of preexisting HIV-1 mutations on the activity of lenacapavir in a large panel of HIV-1 mutants. These included mutants harboring resistance to existing drug classes, patient-derived HIV isolates with naturally occurring Gag polymorphisms, and site-directed mutants containing mutations at Gag cleavage sites associated with PI resistance or MI resistance. As the antiviral activity of lenacapavir is aimed at the capsid component of Gag (4, 5), which is itself the main substrate for HIV protease, investigating the potential interplay between Gag mutations and inhibition of capsid function by LEN is an important step in the characterization of the new class of capsid inhibitor (CAI) compounds.

Here, we have shown that the picomolar potency of LEN was not affected (fold changes ≤ 1.5) by the presence of PI-associated Gag cleavage site mutations (GCSMs) selected as a result of prior PI treatment (7, 15, 16), indicating an absence of interplay between the presence of PI-associated GCSMs and capsid function inhibition by LEN. In contrast, low-level resistance (2- to 4-fold) to atazanavir was measured in PI-associated mutants with GCSMs, particularly, the K436E-I437T double mutant that showed a 3.6-fold reduced susceptibility to ATV (2.3-fold for DRV), consistent with prior data (ATV FC = 5 [15]). This mutant (K436E-I437T) also conferred 10- and 6-fold reduced susceptibility to maturation inhibitors (BVM and GSK-795, respectively), while the 3 MI-associated mutants (L363F, L363M, and A364V) showed a low but consistently reduced susceptibility across all 3 mutants (ATV FC ≥ 2.4 and DRV FC ≥ 1.8). These observations suggest some level of cross-resistance between PIs and MIs, which is consistent with their involvement in Gag processing. Overall resistance to BVM with the 3 MI-associated mutants indicated complete loss of activity of the compound, consistent with prior data with these mutants (10, 20). Interestingly, high-level resistance (FC > 200-fold) to the MI GSK-795 was observed only in 2 of the mutants (L363F and A364V), with the 3rd mutant showing markedly less reduction in susceptibility to GSK-795 (FC of 5.3 for L363M mutant). This indicates that these 2 MIs differ in their resistance profiles, consistent with earlier data (19).

Beyond the point mutations mentioned above, clinical resistance to BVM has been shown to be mediated by naturally existing polymorphisms in Gag, particularly in the vicinity of the capsid/SP1 cleavage site of Gag and in the SP1 peptide (8, 18, 20). To assess whether the presence of naturally existing polymorphisms in Gag had an effect on LEN susceptibility, we generated patient-derived HIV-1 mutants containing the entire gag-pro sequence from treatment-naive (TN) and treatment-experienced (TE) HIV-1-infected people and studied their phenotypic susceptibility to LEN and control compounds. We found that the antiviral activity of LEN was unchanged and comparable to that of the wild-type control across both TN and TE patient samples. In contrast, we found that the activity of both BVM and GSK-795 was reduced in nearly half of the samples tested across both TN and TE patient samples, consistent with previously published data on BVM (18). Notably, GSK-795 displayed an improved resistance profile over that of BVM. These data confirm that LEN activity is not constrained by the presence of naturally existing polymorphisms in Gag, emphasizing the lack of overlap in the resistance profile of LEN compared to those of MIs.

In addition to the characterization of LEN antiviral activity in HIV-1 harboring Gag mutations discussed above, we analyzed LEN in vitro susceptibility in mutants with resistance mutations against the 4 main classes of anti-HIV drugs (NRTIs, NNRTIs, PIs, and INSTIs). We found that while control compounds exhibited the expected reduction in susceptibility relative to that for the mutations present, LEN antiviral activity was unchanged and measured at a wild-type level or lower in all 40 mutants tested, emphasizing the lack of cross-resistance between LEN and existing drugs.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the antiviral activity of LEN in vitro is not affected by the presence of mutations such as cleavage site mutations and naturally occurring polymorphisms in Gag and that LEN exhibits no cross-resistance to mutants resistant to the main classes of drugs. In addition, recent data indicated that no preexisting capsid mutations associated with in vitro resistance to LEN were found in an analysis of 1,500 capsid sequences from PWH with diverse ARV treatment experience (6). Furthermore, LEN picomolar susceptibility remained consistent near the wild-type level in all patient isolates tested, whether from treatment-naive or -experienced people. Altogether, these limited in vitro data suggest that LEN has the potential to be efficacious in people with HIV regardless of their treatment history or HIV-1 genetic sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds and reagents.

LEN, bevirimat (BVM), dolutegravir (DTG), darunavir (DRV), atazanavir (ATV), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) were synthesized at Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA, USA). GSK-3532795 was synthesized at GVK Biosciences (Hyderabad, India). GlutaMAX RPMI 1640 culture medium, Gibco Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) high glucose, penicillin (10,000 U/ml), streptomycin (10,000 µg/ml), and 100× HEPES were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT). Cell culture media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 5 ml of penicillin (10,000 U/ml) and streptomycin (10,000 µg/ml), and 5 ml of 100× HEPES per 500 ml medium.

Cells and viruses.

HEK293T cells (also referred as 293T cells) used for virus production were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). MT-2 cells were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD, USA). The viral plasmid pXXLAI used to generate the viruses was a gift from John Mellors. The plasmid was derived from the infectious clone pLAI3.2 which was modified to contain an XmaI and an XbaI restriction site within the HIV RT gene (21) to facilitate cloning.

Cloning of HIV-1 patient isolates.

HIV isolates containing the HIV-1 gag-pro segment were generated from plasma samples from treatment-experienced (TE) and treatment-naive (TN) patient samples from past Gilead clinical studies (GS-99-907, GS-US-183-0105, GS-US-183-0145, GS-US-01-934, and GS-US-292-0104). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Genotypic and phenotypic resistance testing for all these samples had been characterized using the HIV-1 single-cycle PhenoSense GT assay (Monogram Biosciences, South San Francisco, CA, USA) (22) as part of the protocol for the studies. Plasma samples were treated with 4 units of DNase I (New England Biolabs [NEB], Waltham, MA, USA) for 45 min at room temperature, and viral RNA was extracted from 400 μl of plasma using the EZ1 Virus minikit v2.0 with the BioRobot EZ1 workstation (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and eluted in 60 μl. Viral RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Ready-To-Go You-Prime first-strand beads (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with random hexamers (catalog number N8080127; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a final concentration of 1.5 μM. The HIV-1 gag-pro fragments from these plasma samples were amplified by 2 rounds of 35 cycles of PCR (Phusion high-fidelity PCR kit [NEB) using the following primers: 1st round, 1F, GCTTAAGCCTCAATAAAGCTTGCCTTG, and 1R, GGCCCAATTTTTGAAATTTTCCCTTCC; 2nd round, 2F, ATCTCTAGCAGTGGCGCCCGAACAGGGACTTGAAAG, and 2R, GGCCATCCATCCCGGGCTTTAATTTTACTGGTACAGTTTC. PCR primers were purchased from ELIM Pharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA, USA). The wild-type pXXLAI vector was linearized with restriction enzymes at the unique SfoI and XmaI sites (NEB), and the PCR products were inserted into the linearized pXXLAI vector using In-Fusion cloning (TaKaRa, Mountain View, CA, USA). Transformed bacteria were amplified, and the DNA sequence was confirmed by sequencing (TACGen, San Pablo, CA, USA). Plasmid DNA was purified at ELIM Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA, USA).

HIV-1 site-directed mutant virus cloning.

Site directed HIV-1 mutant viruses were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of pXXLAI (Genewiz, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Nineteen viruses were generated to contain GCSMs (K436E, I437T, I437V, I437V plus V82A, K436E plus I437T, A431V, A431V plus V82A, A431V plus I84V, L449H, L449V, L449F, L449F plus I84V, Q430R, Q430R plus I84V, P453L, P453L plus I84V, L363F, L363M, or A364V) with or without the protease resistance mutations V82A or I84V. Viruses with either the V82A or I84V mutation in protease were generated as controls.

Virus production.

pXXLAI DNA plasmids (generated as described above) were transfected into 293T cells with the transfection reagent TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) using 7 µg of the viral plasmid DNA in 2 million 293T cells that were seeded in T-25 cell culture flasks in a 6-ml volume 1 day before transfection. The cell culture supernatant containing the virus stock was harvested on day 1 and day 2 after transfection and tested in infectivity assays.

HIV-1 antiviral assay.

The phenotype of the HIV-1 isolates was determined in a 5-day multicycle antiviral assay in MT-2 cells using a luciferase-based viability readout (CellTiter-Glo; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) (23). Briefly, MT-2 cells (2.4 million) were incubated with virus for 3 h at 37°C in 1-ml screw-cap tubes. The amount of virus used was normalized to yield a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio in the range of 4 to 7, which was equivalent to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.003 for wild-type HIV-1IIIB based on the provided titer. The S/N ratio was calculated from the 300 nM DTG control (maximum cell survival) and the no drug control (minimum cell survival). Fivefold dilutions of the drugs of interest were prepared and transferred in triplicates to the inside wells of 96-well assay plates. After the 3-h incubation, the infected MT-2 cells were diluted 1:14 to a concentration of 0.17 million cells/ml with tissue culture medium, and 50 µl of cell suspension was transferred to all wells in the assay plates. After 5 days of incubation at 37°C (5% CO2, 95% humidity), 100 µl of CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to each well, and luminescence was measured using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA). Percent inhibition in the drug-containing wells in comparison to that in the fully protected DTG control and the associated effective concentration to inhibit 50% of viral replication (EC50) were plotted and calculated using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and XL Fit (IDBS, Alameda, CA, USA). Statistical significance of the fold changes for the mutants compared to the wild-type control was calculated using Excel (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Antiviral activity of LEN in isolates with resistance to the 4 main drug classes.

The in vitro antiviral activity of LEN was also tested against a panel of 40 patient isolates with resistance against the 4 main drug classes, using the single-cycle FDA-approved CLIA-validated PhenoSense assay (Monogram Biosciences, South San Francisco, CA, USA) (22). In that assay, PR-RT or integrase (IN) sequences from patient isolates with resistance mutations were cloned in an env-deleted pNL4-3-based plasmid (GenBank AF324493 for unmodified plasmid), cotransfected with a plasmid producing the envelope proteins from the amphotropic murine leukemia virus, and assayed for drug susceptibility in 96-well plates as described previously (22). Ten isolates per class were tested in the assay (details of the HIV-1 subtype and resistance-associated mutations [RAMs] found in each isolate are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material), including nucleoside RT inhibitor (NRTI)-resistant isolates (containing combinations of RT mutations M41L, A62V, K65R, D67N, T69ins, K70R, L74V, V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M, M184V, L210W, T215Y/F, and/or K219Q), non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI)-resistant isolates (containing combinations of RT mutations A98G, L100I, K101E/H/P, K103N/S, V106A/I/M, E138A/G/K/Q/R, V179D/F/L/T, Y181C/I/V, Y188C/H/L, G190A/E/Q/S, P225H, and/or F227C), protease inhibitor (PI)-resistant isolates (containing combinations of protease mutations D30N, V32I, L33F, M46I/L, I47V, G48V, I50L/V, I54L/V, V82A, I84V, N88D, and/or L90M), and integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-resistant isolates (containing combinations of IN mutations E92Q, T97A, Y143C/R, Q148H/R/K, and/or N155H. All 40 isolates had HIV-1 subtype B.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

All authors are employees of and stockholders in Gilead Sciences Inc., which funded the study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freed EO. 2015. HIV-1 assembly, release and maturation. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:484–496. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrose Z, Aiken C. 2014. HIV-1 uncoating: connection to nuclear entry and regulation by host proteins. Virology 454–455:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spearman P. 2016. HIV-1 Gag as an antiviral target: development of assembly and maturation inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem 16:1154–1166. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150902102143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yant SR, Mulato A, Hansen D, Tse WC, Niedziela-Majka A, Zhang JR, Stepan GJ, Jin D, Wong MH, Perreira JM, Singer E, Papalia GA, Hu EY, Zheng J, Lu B, Schroeder SD, Chou K, Ahmadyar S, Liclican A, Yu H, Novikov N, Paoli E, Gonik D, Ram RR, Hung M, McDougall WM, Brass AL, Sundquist WI, Cihlar T, Link JO. 2019. A highly potent long-acting small-molecule HIV-1 capsid inhibitor with efficacy in a humanized mouse model. Nat Med 25:1377–1384. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link JO, Rhee MS, Tse WC, Zheng J, Somoza JR, Rowe W, Begley R, Chiu A, Mulato A, Hansen D, Singer E, Tsai LK, Bam RA, Chou CH, Canales E, Brizgys G, Zhang JR, Li J, Graupe M, Morganelli P, Liu Q, Wu Q, Halcomb RL, Saito RD, Schroeder SD, Lazerwith SE, Bondy S, Jin D, Hung M, Novikov N, Liu X, Villasenor AG, Cannizzaro CE, Hu EY, Anderson RL, Appleby TC, Lu B, Mwangi J, Liclican A, Niedziela-Majka A, Papalia GA, Wong MH, Leavitt SA, Xu Y, Koditek D, Stepan GJ, Yu H, Pagratis N, Clancy S, Ahmadyar S, et al. 2020. Clinical targeting of HIV capsid protein with a long-acting small molecule. Nature 584:614–618. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2443-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcelin AG, Charpentier C, Jary A, Perrier M, Margot N, Callebaut C, Calvez V, Descamps D. 2020. Frequency of capsid substitutions associated with GS-6207 in vitro resistance in HIV-1 from antiretroviral-naive and -experienced patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:1588–1590. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavel F, Mammano F. 2010. Role of Gag in HIV resistance to protease inhibitors. Viruses 2:1411–1426. doi: 10.3390/v2071411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCallister S, Lalezari J, Richmond G, Thompson M, Harrigan R, Martin D, Salzwedel K, Allaway G. 2008. HIV-1 Gag polymorphisms determine treatment response to bevirimat (PA-457). XVII International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop, Sitges, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F, Goila-Gaur R, Salzwedel K, Kilgore NR, Reddick M, Matallana C, Castillo A, Zoumplis D, Martin DE, Orenstein JM, Allaway GP, Freed EO, Wild CT. 2003. PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13555–13560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234683100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamson CS, Ablan SD, Boeras I, Goila-Gaur R, Soheilian F, Nagashima K, Li F, Salzwedel K, Sakalian M, Wild CT, Freed EO. 2006. In vitro resistance to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 maturation inhibitor PA-457 (bevirimat). J Virol 80:10957–10971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyon L, Croteau G, Thibeault D, Poulin F, Pilote L, Lamarre D. 1996. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J Virol 70:3763–3769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.70.6.3763-3769.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cote HCF, Brumme ZL, Harrigan PR. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease cleavage site mutations associated with protease inhibitor cross-resistance selected by indinavir, ritonavir, and/or saquinavir. J Virol 75:589–594. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.589-594.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang YM, Imamichi H, Imamichi T, Lane HC, Falloon J, Vasudevachari MB, Salzman NP. 1997. Drug resistance during indinavir therapy is caused by mutations in the protease gene and in its Gag substrate cleavage sites. J Virol 71:6662–6670. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.9.6662-6670.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verheyen J, Litau E, Sing T, Daumer M, Balduin M, Oette M, Fatkenheuer G, Rockstroh JK, Schuldenzucker U, Hoffmann D, Pfister H, Kaiser R. 2006. Compensatory mutations at the HIV cleavage sites p7/p1 and p1/p6-gag in therapy-naive and therapy-experienced patients. Antivir Ther 11:879–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nijhuis M, van Maarseveen NM, Lastere S, Schipper P, Coakley E, Glass B, Rovenska M, de Jong D, Chappey C, Goedegebuure IW, Heilek-Snyder G, Dulude D, Cammack N, Brakier-Gingras L, Konvalinka J, Parkin N, Krausslich HG, Brun-Vezinet F, Boucher CA. 2007. A novel substrate-based HIV-1 protease inhibitor drug resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 4:e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dam E, Quercia R, Glass B, Descamps D, Launay O, Duval X, Krausslich HG, Hance AJ, Clavel F, ANRS 109 Study Group. 2009. Gag mutations strongly contribute to HIV-1 resistance to protease inhibitors in highly drug-experienced patients besides compensating for fitness loss. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000345. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatanaga H, Suzuki Y, Tsang H, Yoshimura K, Kavlick MF, Nagashima K, Gorelick RJ, Mardy S, Tang C, Summers MF, Mitsuya H. 2002. Amino acid substitutions in Gag protein at non-cleavage sites are indispensable for the development of a high multitude of HIV-1 resistance against protease inhibitors. J Biol Chem 277:5952–5961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margot NA, Gibbs CS, Miller MD. 2010. Phenotypic susceptibility to bevirimat in isolates from HIV-1-infected patients without prior exposure to bevirimat. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2345–2353. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01784-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowicka-Sans B, Protack T, Lin Z, Li Z, Zhang S, Sun Y, Samanta H, Terry B, Liu Z, Chen Y, Sin N, Sit SY, Swidorski JJ, Chen J, Venables BL, Healy M, Meanwell NA, Cockett M, Hanumegowda U, Regueiro-Ren A, Krystal M, Dicker IB. 2016. Identification and characterization of BMS-955176, a second-generation HIV-1 maturation inhibitor with improved potency, antiviral spectrum, and Gag polymorphic coverage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3956–3969. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02560-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choe SS, Feng Y, Limoli K, Salzwedel K, McCallister S, Huang W, Parkin NT. 2008. Measurement of maturation inhibitor susceptibility using the PhenoSenseHIV assay, poster 880. 15th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi C, Mellors JW. 1997. A recombinant retroviral system for rapid in vivo analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 susceptibility to reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:2781–2785. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.12.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petropoulos CJ, Parkin NT, Limoli KL, Lie YS, Wrin T, Huang W, Tian H, Smith D, Winslow GA, Capon DJ, Whitcomb JM. 2000. A novel phenotypic drug susceptibility assay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:920–928. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.4.920-928.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margot NA, Hluhanich RM, Jones GS, Andreatta KN, Tsiang M, McColl DJ, White KL, Miller MD. 2012. In vitro resistance selections using elvitegravir, raltegravir, and two metabolites of elvitegravir M1 and M4. Antiviral Res 93:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.