A common strategy to identify new antiparasitic agents is the targeting of proteases, due to their essential contributions to parasite growth and development. Metacaspases (MCAs) are cysteine proteases present in fungi, protozoa, and plants.

KEYWORDS: Chagas disease, sleeping sickness, antiparasitic agent, inhibitors, metacaspases, target-based screening

ABSTRACT

A common strategy to identify new antiparasitic agents is the targeting of proteases, due to their essential contributions to parasite growth and development. Metacaspases (MCAs) are cysteine proteases present in fungi, protozoa, and plants. These enzymes, which are associated with crucial cellular events in trypanosomes, are absent in the human host, thus arising as attractive drug targets. To find new MCA inhibitors with trypanocidal activity, we adapted a continuous fluorescence enzymatic assay to a medium-throughput format and carried out screening of different compound collections, followed by the construction of dose-response curves for the most promising hits. We used MCA5 from Trypanosoma brucei (TbMCA5) as a model for the identification of inhibitors from the GlaxoSmithKline HAT and CHAGAS chemical boxes. We also assessed a third collection of nine compounds from the Maybridge database that had been identified by virtual screening as potential inhibitors of the cysteine peptidase falcipain-2 (clan CA) from Plasmodium falciparum. Compound HTS01959 (from the Maybridge collection) was the most potent inhibitor, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 14.39 µM; it also inhibited other MCAs from T. brucei and Trypanosoma cruzi (TbMCA2, 4.14 µM; TbMCA3, 5.04 µM; TcMCA5, 151 µM). HTS01959 behaved as a reversible, slow-binding, and noncompetitive inhibitor of TbMCA2, with a mechanism of action that included redox components. Importantly, HTS01959 displayed trypanocidal activity against bloodstream forms of T. brucei and trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi, without cytotoxic effects on Vero cells. Thus, HTS01959 is a promising starting point to develop more specific and potent chemical structures to target MCAs.

INTRODUCTION

Parasite proteases represent a large and diverse group of enzymes that, having vital roles in nutrition and pathogenicity, offer great potential for drug development. In the past few years, extensive research has been dedicated to a unique family of enzymes called metacaspases (MCAs), which are cysteine peptidases present in plants, fungi, and protozoa (1). MCAs contain a His-Cys catalytic dyad and have been classified into clan CD according to their structural homology with caspases (family C14), clostripain (family C11), gingipain (family C25), and separase (family C50). Among the biochemical similarities inside this clan is the restricted specificity dominated by the nature of the residue on the amino-terminal side of the scissile bond, which in the case of MCAs is a basic amino acid residue (Arg or Lys) (2). MCAs are active as monomers and do not require activation by proteolytic processing but are absolutely dependent on the presence of free calcium (usually at millimolar concentrations) (3–5) to display maximal activity. Among the best-studied MCAs are those present in trypanosomatids (6), parasitic protists that cause serious neglected diseases in humans and animals and affect a large number of people worldwide. They include Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiological agent of Chagas disease in South America, Trypanosoma brucei, which causes African sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals, and different species from the genus Leishmania, which produce diverse clinical forms of leishmaniasis.

The genome of Trypanosoma brucei contains five MCA genes (TbMCA1 to TbMCA5) (7). For TbMCA2, the peptidase activity was experimentally confirmed (4), a finding that can be extrapolated to the almost identical TbMCA3. In addition, and according to the presence of an intact catalytic dyad, TbMCA5 can be predicted to be active. In contrast, TbMCA1 and TbMCA4 have substitutions of these residues and could lack peptidase activity, a fact that was demonstrated for recombinant TbMCA4 (8). Active T. brucei MCAs have stage-regulated expression and are present mainly in mammalian (bloodstream) infective forms, with only TbMCA5 being additionally expressed at the insect (procyclic) stage (9). It is interesting to note that a certain level of redundancy might exist between different MCAs, since individual RNA interference (RNAi) downregulation does not affect parasite growth in culture. However, simultaneous (triple) RNAi silencing leads to a lethal phenotype, indicating that MCAs indeed play a crucial role in the cell (9). In Trypanosoma cruzi, on the other hand, there are two MCA paralogues, named TcMCA3 and TcMCA5, which are present in multiple copies and as a single copy, respectively (10). Both types of genes encode active proteases that are tightly regulated, and roles in cell death, cell cycle progression, and differentiation have been inferred from overexpression experiments (3). More recently, the DNA-damage-inducible protein 1 (Ddi1) was identified as a conserved natural MCA substrate (11). Ddi1 is a proteasomal shuttle delivering proteins for degradation through interaction with the proteasome via their ubiquitin-like domain, as well as ubiquitinated cargoes through their ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain. MCA cleavage eliminates the UBA domain present in Ddi1 and reduces the protein stability, which in turn could affect many diverse and important cellular processes, including protein degradation and cell cycle control.

MCAs arose as attractive potential drug targets due to their absence in mammals, their low sequence similarity to human caspases, and their participation in diverse and important biological events. However, only a few inhibitors based on the Arg specificity of these enzymes have been described to date, exhibiting micromolar inhibition and modest antiparasitic activity (12). Here, we report the adaptation of a continuous fluorescence enzymatic assay to a medium-throughput format to screen the GlaxoSmithKline HAT and CHAGAS boxes. These boxes encompass 404 compounds with great structural diversity that exhibit high antiparasitic potency and no toxicity for mammalian cells. Interestingly, these molecules are novel (as they do not contain analogs to drugs currently used for Chagas disease or sleeping sickness) and display drug-like physicochemical properties (13). In addition, we assessed a third collection of nine compounds from the Maybridge database that were identified by virtual screening as potential inhibitors of the cysteine peptidase falcipain-2 (clan CA) from Plasmodium falciparum (14). For the best resulting compound (HTS01959), we further characterized the inhibition potency for multiple MCAs, the inhibition mode, and finally the antiparasitic activity on T. brucei and T. cruzi infective forms.

RESULTS

Development of a TbMCA5 assay capable of high-throughput screening.

With the aim of screening larger compound collections, we first developed and optimized a continuous fluorogenic assay for TbMCA5 using the prototypic MCA substrate Z-VRPR-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) (15). We carried out the optimization process in solid-black 384-well plates, using a small set of bioactive compounds. A convenient enzyme concentration in the assay was determined through the activity of 2-fold dilutions of recombinant TbMCA5 at a fixed substrate concentration of 75 µM (Fig. 1A). For all of the enzyme concentrations, progression curves remained linear for at least 40 min and the Selwyn test (16) indicated that the enzyme remained stable during the assay (R2 = 0.994 for the linear fit of data from different enzyme concentrations to a single curve) (Fig. 1B). In addition, the V0 versus [E]0 curve showed the expected linear behavior for a wide range of enzyme concentrations (Fig. 1C), and neither Triton X-100 (0 to 0.03% [vol/vol]) nor dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0 to 3% [vol/vol]) induced noticeable changes in enzyme activity (data not shown). Thus, we selected a starting TbMCA5 concentration of 103 nM as the running enzyme concentration for the assay. Surprisingly, the enzymatic activity of TbMCA5 remained linear with respect to Z-VRPR-AMC concentration in the range of 7.81 µM to 1 mM, suggesting that even the highest substrate concentration assayed was well below the Km value (Fig. 1D). Because it was impractical to use such a high substrate concentration for the screening, we continued using a substrate concentration of 75 µM although it would hinder the identification of uncompetitive inhibitors. In the absence of enzyme, no spontaneous hydrolysis of the Z-VRPR-AMC substrate was observed, although some level of photobleaching was suggested by the linear decay in fluorescence readouts with time. Although we were unable to reduce further the moderate dispersion of enzyme positive controls (coefficient of variation of ≤12.5%), the optimized assay exhibited satisfactory performance during preliminary characterization experiments, with a dynamic range (µC+ − µC−) greater than 1,200 relative fluorescence units (RFU)/s, a µC+/µC− ratio of ≥1,000, and a Z′ factor value around 0.6.

FIG 1.

Continuous fluorogenic assay for recombinant TbMCA5. (A) Kinetic progression curves for different TbMCA5 concentrations at a fixed dose (75 µM) of Z-VRPR-AMC. (B) Selwyn test for different TbMCA5 concentrations. Data from different enzyme concentrations (represented by different symbols in the graph) are well fitted by a single curve. (C) Curve of V0 versus [TbMCA5]0. (D) Michaelis-Menten plot. In all cases, data corresponding to a TbMCA5 concentration of 103 nM with a Z-VRPR-AMC concentration of 75 µM, conditions selected for compound screening, are indicated in red. In panels C and D, V0 is defined as the slope (dF/dt) of the linear region of progress (fluorescence versus time) curves.

Five compounds inhibit TbMCA5 in a dose-dependent manner.

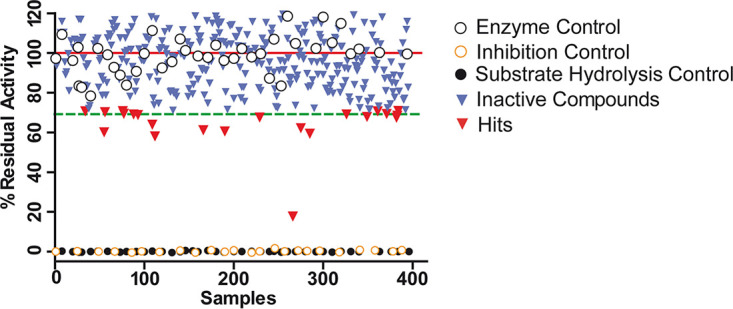

With the aim of identifying new TbMCA5 inhibitors active against T. brucei and T. cruzi, we initially assessed the compound sets identified from high-throughput phenotypic screening against T. brucei (HAT box) and T. cruzi (CHAGAS box). In addition, we also evaluated a small set of nine compounds from the Maybridge database, previously identified by us through structure-based virtual screening as potential inhibitors of the cysteine peptidase falcipain-2 from Plasmodium falciparum (17). All compounds were assayed in singlet (without technical replicates) at a fixed dose of 33.3 µM, due to the limited availability of stocks. As shown in Fig. 2, the vast majority of investigated compounds were inactive on TbMCA5 and those with activity exhibited only modest inhibitory effects. At the tested concentration, 21 compounds reduced TbMCA5 activity by ≥30%. These compounds were included in the secondary screening. Statistics for primary screening are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

FIG 2.

Activity plot for the assayed compounds during primary screening against TbMCA5. The solid red line shows the average of enzyme activity controls (C+), and the dashed green line represents the cutoff value for selection of hits, which is 70% residual activity (equivalent to 30% inhibition). Black open circles represent enzyme controls, black closed circles substrate controls, and orange open circles inhibition controls (Z-VRPR-FMK). Blue and red inverted triangles represent inactive compounds and hits, respectively. Highly autofluorescent compounds (17) were discarded from further analysis due to the negative impact they have on reproducibility (i.e., they are able to interfere significantly with fluorescence assay readouts).

To estimate 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for the resulting hits, 2-fold serial dilutions (ranging from 125 µM to 3.8 pM) were analyzed using identical conditions, except for a reduction in the assay volume to 40 µl to achieve higher compound concentrations. Of the 21 hits selected during primary screening, only 5 showed dose-dependent inhibition of TbMCA5 (Fig. 3A). Among them, 4 hits from the HAT (TCMDC-143373 and TCMDC-143382) and CHAGAS (TCMDC-143071 and TCMDC-143601) boxes showed modest IC50 values, in the range of 79 to 142 µM, while the compound HTS01959 from the Maybridge collection was the most potent TbMCA5 inhibitor, with an IC50 value of 12.6 µM (Fig. 3A). The structures of the identified hits are depicted in Fig. 3B.

FIG 3.

Dose-response curves and structures of the identified TbMCA5 inhibitors. (A) Dose-response curves. For each compound, the solid line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). The best fit for the irreversible inhibitor Z-VRPR-FMK is represented as a gray dashed line. Concentrations of inhibitors (logarithmic x axis) are molar. (B) Structures of identified TbMCA5 inhibitors.

HTS01959 preferentially inhibits the MCAs of T. brucei.

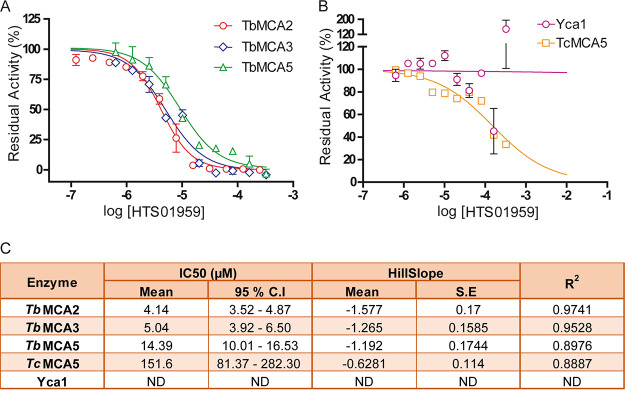

Given that HTS01959 inhibited TbMCA5 6 to 11 times more potently than the rest of the identified inhibitors, we decided to functionally characterize this inhibition in terms of modality and specificity. Initially, we investigated whether HTS01959 was able to inhibit other closely related MCAs. In addition to TbMCA5, HTS01959 inhibited TbMCA2 and TbMCA3 from T. brucei (Fig. 4A). Of note, this compound inhibited both enzymes more potently than TbMCA5, with similar IC50 values in the low micromolar range (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, MCAs from other organisms, such as TcMCA5 (T. cruzi) and Yca1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), were significantly less sensitive to HTS01959 inhibition (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Dose-response curves for the inhibition of different MCAs by HTS01959. (A) Dose-response curves for T. brucei MCAs. (B) Dose-response curves for MCAs from other organisms. For each curve, the solid line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). (C) Summary of results of dose-response assays with different MCAs incubated with HTS01959. HTS01959 concentrations are expressed as molar. ND, not determined.

We further expanded our specificity analysis to prototypical peptidases from different mechanistic classes. As expected, HTS01959 was inactive against nonrelated peptidases such as chymotrypsin (class serine, clan PA, family S1), pepsin (class aspartic, clan AA, family A1), and angiotensin-1-converting enzyme (class metallo, clan MA, family M2) and weakly active against the papain-like cysteine peptidases cruzipain and falcipain-2 (clan CA, family C1) (Fig. S1).

HTS01959 behaves as a reversible, slow-binding, and noncompetitive inhibitor of TbMCA2.

Considering that TbMCA2 was the T. brucei MCA more potently inhibited by HTS01959 and the only one whose crystallographic structure has been determined (18), we decided to continue the characterization of HTS01959 inhibitory activity using TbMCA2 as the model enzyme. Features of the TbMCA2 assay are summarized in Fig. S2.

We next characterized HTS01959 in terms of reversibility and time dependence of TbMCA2 inhibition. Reversible interaction with the enzyme was verified by the recovery of TbMCA2 activity after rapid addition of substrate (100-fold dilution) to the preincubated mixture of enzyme and inhibitor (Fig. 5A). In this experiment, the compound displayed a linear progressive curve (Fig. 5A) with a stable inhibition value, indicative of rapid onset of the steady state (i.e., rapid dissociation of the enzyme-inhibitor complex). In contrast, the inhibitor displayed different kinetic behavior when enzyme was added to a reaction mixture previously containing inhibitor and substrate (Fig. 5B). In this case, HTS01959 showed nonlinear kinetics, with inhibition progressively increasing over time (time-dependent inhibition). Because stable inhibition was observed only after ∼1 h, all subsequent kinetic experiments for this compound included preincubation (≥60 min at 37°C) with the enzyme.

FIG 5.

Reversibility and time dependence of the inhibition of TbMCA2 by HTS01959. (A) Product progress curves for dissociation of the enzyme-inhibitor (E-I) complex by rapid dilution (100-fold) of the enzyme-inhibitor mixture into the substrate solution. (B) Product progress curves for formation of the E-I complex by rapid addition of the enzyme to a substrate-inhibitor mixture. (C) Dose-response curves for HTS01959 at increasing substrate concentrations. (D) Effect of substrate concentration on IC50 values. HTS01959 concentrations are expressed as molar.

To investigate the mode of inhibition of HTS01959 for the activity of TbMCA2, we evaluated the impact of substrate concentration on the apparent IC50 value over the widest range (0.04× Km to 1.6× Km) of substrate saturations we could assess. For this, we used a reduced set of four HTS01959 concentrations selected (i) to include the IC50 value for each substrate condition and (ii) to cover the wider inhibition range (∼10 to 90%) in the central stretch of the dose-response curve. As observed in Fig. 5C and D, IC50 values decreased with the increment of substrate concentration (Table S3), suggesting an apparent noncompetitive inhibition phenotype with an α value of <1. Because complete Michaelis curves were not obtained at each inhibitor concentration, we were unable to estimate definitive values for α and Ki (Fig. S3).

The inhibitory mechanisms of HTS01959 include a redox component.

Given that cysteine peptidases rely on the reduced state of their catalytic sulfhydryl group for maximal enzymatic activity, they are particularly susceptible to thiol-reactive compounds, which can reduce enzyme activity by several redox mechanisms. In many cases, the activity of these compounds can be significantly modified by changing the reduction potential of the activity buffer, thus providing a diagnostic test to detect compound-specific redox effects (19). To establish whether this could be the case for HTS01959, we investigated the effects of the strength and concentration of reducing agents on the inhibition of TbMCA2 by this molecule. As shown in Fig. 6A, the IC50 value increased >2 orders of magnitude with the increment of dithiothreitol (DTT) concentrations (in the range 0.1 to 20 mM) in the assay buffer, suggesting a dose-dependent protective role of strong reducing agents on TbMCA2 activity. A decrease of HTS01959 inhibition with the increment in DTT concentrations was also observed for other cysteine proteases such as cruzipain and falcipain-2 (Table S2).

FIG 6.

Effects of the strength and concentration of reducing agents on the inhibitory activity of HTS01959. (A) Dose-response curves for the inhibition of TbMCA2 by HTS01959 at increasing concentrations of DTT. (B) Dose-response curves in the presence of strong (DTT) and weak (β-mercaptoethanol and cysteine) reducing agents at identical concentrations of 10 mM. For each curve, the solid line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). β-ME, β-mercaptoethanol. (C) Summary of results from panels A and B. N. I., no inhibition. HTS01959 concentrations are expressed as molar.

A significant decrease in the inhibitory potency of HTS01959 was also observed in the presence of Cys (monothiol), which is considered a weak reducing agent in comparison to DTT (dithiol). Strikingly, Cys displayed more potent protection of TbMCA2 activity than did DTT at a wide range of concentrations. At a Cys concentration of 0.1 mM, the IC50 value was 34-fold higher than that with DTT at the same concentration; the value increased to ∼69-fold at 1 mM (Table S3; Fig. 6C). At 10 mM, Cys completely abolished the inhibitory activity of HTS01959 on TbMCA2, while still significant inhibition (IC50 of 49.2 µM) was observed at an identical DTT concentration. Of note, β-mercaptoethanol (10 mM), another monothiol considered a weak reducing agent, also protected TbMCA2 activity from HTS01959 inhibition better than DTT, although less potently (∼6-fold) than Cys (Fig. 6B).

We reasoned that the apparent low efficacy of DTT in protecting TbMCA2 activity from HTS01959 inhibition would result from the balance of opposing (protective versus proinhibitory) effects, which would not occur in the presence of weak reducing agents (which would show only protective effects). Given that some compounds are able to undergo redox cycling in the presence of DTT, leading to the generation of the strong oxidizing agent H2O2, we decided to evaluate whether this could be the case with HTS01959 using a horseradish peroxidase (HRPO)-based colorimetric assay (20). As shown in Fig. 7A, a significant increase in the optical density at 505 nm was observed when HTS01959 was incubated in the presence of DTT (2 mM) but not Cys, suggesting the generation of H2O2 under enzymatic assay conditions. Interestingly, the generation of H2O2 was very low at 10 mM DTT, which is in agreement with our inhibition experiments and previous reports (20). Additionally, the IC50 value of HTS01959 was 4-fold higher (64.4 µM) in the presence of the very efficient H2O2-decomposing enzyme catalase (Fig. 7B). This finding suggests that the generation of H2O2 operates as one of the previously suspected proinhibitory mechanisms that specifically occur in the presence of DTT. Of note, this also suggests that HTS01959 promotes additional inhibitory effects on TbMCA2 activity independent of H2O2 generation, as catalytically competent catalase concentrations were unable to abolish the inhibitory activity of this compound.

FIG 7.

Specific hydrogen peroxide generation by HTS01959 in the presence of low millimolar DTT concentrations. ((A) Enzymatic quantification of H2O2 generated at different conditions by HRPO-catalyzed oxidation of 4-aminophenazone. This reaction produces a colored product with strong absorbance at 505 nm. C28 [2-hydroxy-3-(1-propenyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone] was used as a positive control as a quinoid redox-cycling compound. The statistical significance was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest. ***, P < 0.001. (B) Dose-response curves for the inhibition of TbMCA2 by HTS01959 in the presence (200 µg/ml) and absence of catalase. For each curve, the dashed line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). HTS01959 concentrations are expressed as molar.

HTS01959 is active on T. brucei bloodstream forms and T. cruzi cell-derived trypomastigotes.

Finally, we evaluated the antiparasitic potential of HTS01959 in cultures of T. brucei and T. cruzi. We estimated the 50% effective concentration (EC50) for this compound with T. brucei bloodstream forms by using the resazurin viability assay. As shown in Fig. 8A, HTS01959 reduced the growth in a dose-dependent manner, with an EC50 value of 37.89 µM. In the case of T. cruzi, HTS01959 was not effective against the replicative intracellular amastigote form, as judged by the results obtained in our image-based assays (Fig. 8B), but exhibited modest activity against the cell-derived trypomastigote stage, with a EC50 value of 91.2 µM determined by the resazurin viability assay. Of note, HTS01959 cytotoxicity on Vero cells was negligible at the highest concentration assayed (130 µM) using the highly sensitive luminescent cell viability assay CellTiter-Glo.

FIG 8.

Activity of HTS01959 on cultured T. brucei bloodstream form and Vero cells. (A) Dose-response curves for T. brucei bloodstream forms treated with HTS01959 or nifurtimox as a control. Viability was determined in triplicate using the resazurin method. Averages ± standard deviations (SDs) are shown. For each curve, the dashed line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). (B) Drug efficacy against T. cruzi intracellular amastigotes. The number of infected cells (red bars) and the number of amastigotes (Amas) per cell (blue bars) (average ± SD) were determined by DAPI staining after 2 days of treatment with 130 µM HTS01959, 4 µM benznidazole as a reference inhibitor, or 0.5% (vol/vol) DMSO as a control. The statistical significance was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest. ***, P < 0.001. (C) Dose-response curve for T. cruzi trypomastigotes with HTS01959. Viability was determined in triplicate using the resazurin method. Averages ± SDs are shown. The dashed line represents the best fit of the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data (open symbols). (D) Cytotoxicity assay on Vero cells treated with HTS01959 and DMSO (0.5% [vol/vol]) as a growth control. Viability was determined in triplicate using a luminescence assay. Averages ± SDs are shown. In all cases, HTS01959 concentrations are expressed as molar.

DISCUSSION

MCAs have proved to be important in trypanosomatid parasites. These enzymes have been involved in processes such as differentiation, cell cycle progression, and protein homeostasis, all critical for parasite development and survival (3–5, 9, 10, 21). Given the global incidence (22–24) of these parasites and the absence of MCAs in humans, they arise naturally as interesting drug targets, which have been used previously for structure-based design of bioactive inhibitors (12).

We exploited the availability of a generic fluorogenic substrate and our previous experience in the exploration of GlaxoSmithKline CHAGAS and HAT chemical boxes against different targets to identify new anti-MCA inhibitory scaffolds bearing significant antiparasitic activity. Four hits, each one representing a different inhibitory scaffold, were identified from the two boxes. Although their inhibitory potency against MCAs (79 to 142 µM) was too modest to fully explain their reported trypanocidal activity in culture (0.4 to 1 µM against their respective parasites) (13), these confirmed hits might be structurally optimized to increase their potency, considering that the crystallographic structure of TbMCA2 was determined previously (18). Interestingly, two of these compounds (TCMDC-143071 and TCMDC-143382) were also identified in a previous work as micromolar inhibitors of the Zn-dependent M32 metallocarboxypeptidases TcMCP-1 and TbMCP-1 (25), suggesting the possibility of a combined mode of action in these parasites (polypharmacology).

Although the assessment of the antiparasitic activity of investigated compounds prior to their target-based evaluation is desirable (13), the most potent MCA inhibitor identified by us in this work was not previously explored in phenotypic screenings against trypanosomatid parasites. In the case of HTS01959, the target-based approach led directly to the discovery of a hit that simultaneously inhibited several MCAs in the single-digit micromolar range and showed a suitable enzyme inhibition profile and modest activity against T. brucei and T. cruzi parasites with no apparent toxicity to Vero cells.

This compound displays a unique inhibition phenotype characterized by reversible effects on MCA activity, rapid dissociation from the enzyme, and time-dependent inhibition. Notably, HTS01959 inhibits TbMCA2 noncompetitively, being to the best of our knowledge the first MCA inhibitor displaying this feature. Like all the inhibitors in this class, HTS01959 is expected to be able to bind both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex, although this compound seems to exhibit a higher affinity for the latter. More importantly, this suggests that HTS01959 may target a binding pocket relatively distant from the active site. From a medicinal chemistry perspective, the identification and targeting of nonactive (i.e., allosteric) binding sites within enzyme molecules provide an attractive and effective alternative to traditional active site-directed inhibitors, which might exhibit advantageous properties (i.e., selectivity). Regarding the difference observed in the inhibition for the TcMCA5 enzyme, it is important to note that the sequence identity between TcMCA5 and TbMCA5 catalytic domains is very high and close to 75%, while these enzymes differ considerably at the C-terminal end, with a sequence identity of approximately 18% (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). Taking into account that the compound HTS01959 behaves as a noncompetitive inhibitor and thus exerts its effect outside the active site, one possible explanation is that the divergent C-terminal end might contribute to the different susceptibility of TcMCA5 to this molecule.

Possibly the most prominent functional characteristic of HTS01959 is its ability to generate H2O2 in vitro in the presence of strong reducing agents. Retrospectively, this compound showed several hallmark features of redox cycling compounds, such as time-dependent inhibition and an inhibitory potency dependent on the strength and concentration of the reducing agent used (20). Preliminary estimations showed that ∼360 µM H2O2 was generated by 100 µM HTS01959 in the assay buffer (containing 2 mM DTT) during 1 h at 37°C (Fig. 7A). It is expected that such an amount of H2O2 could cause a significant effect on the enzymatic activity of a wide variety of protein targets. For that reason, redox cycling compounds are often presented as false-positive hits or at least as nonspecific artifacts that are able to interfere with different assays and target types (20). However, not all of the cysteine peptidases assayed in this study (and not even MCAs) displayed a similar degree of susceptibility to HTS01959. This suggests that a specific component exists and that H2O2 is just one of the inhibitory mechanisms exhibited by this compound. In addition, the contribution of this mechanism to the global inhibitory activity of HTS01959 sharply decreased when the DTT concentration was increased to 10 mM, while significant inhibition was still apparent at least for TbMCA2 (IC50 of 49 µM). Finally, the addition of catalase did not eliminate HTS01959 activity, confirming that H2O2 generation was not the only inhibitory mechanism present. Taken together, our results indicate that the effect of HTS01959 on MCA activity, under the specific and nonphysiological conditions assayed here, is complex and multicomponent.

From a chemical point of view, the functional groups present in a molecule define the spectra of chemical reactions in which it might be involved within living cells. In the case of HTS01959, the three ketonic carbonyl groups stand out from the structure for their polar nature and reactivity; they can undergo nucleophilic addition and redox reactions, among others (26, 27). From this fact, several chemical mechanisms can be envisaged to explain part of the antitrypanosomal activity observed for this compound. Some routes of direct consumption of essential reducing power (NADH, NADPH, or trypanothione) by HTS01959 are depicted in Fig. S6 in the supplemental material. It has been shown that the carbonyl group of 9-fluorenone can be reduced in vivo by the NADPH cytochrome P-450 reductase or other dehydrogenases belonging to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family (28, 29). Interestingly, we found several genes encoding functional SDR enzymes in T. brucei and T. cruzi (Table S4), raising the possibility of such a conversion in trypanosomatid parasites. Carbonyl groups in the 1,3-indandione moiety might also be reduced by a similar mechanism. In addition, indirect routes of oxidative stress might be induced by the compound itself through the formation of intramolecular or intermolecular disulfides and sulfenic acids in proteins. In such cases, different redox enzymes within the parasite could cooperate to regenerate proteins to their reduced forms via different trypanothione-consuming routes (30–32). Even the enzyme-dependent generation of highly reactive oxygen species (e.g., H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides) by HTS01959 within the cell cannot be dismissed (20, 33). Finally, it is also possible that trypanothione, which at physiological pH is partially in the deprotonated thiolate form and can act as a nucleophile (32), is conjugated to carbonyl carbon(s) in HTS01959 by diverse trypanosomatid thiol transferase enzymes. Independently of the specific reaction, all of these mechanisms converge in the same final output, which is to disrupt the vital redox balance within the parasites.

It is noteworthy that a number of trypanocidal drugs in clinical use (such as benznidazole, nifurtimox, fexinidazole, melarsoprol, and eflornithine) actually interfere with antioxidant defenses, confirming the potential of this approach (34, 35). Thus, a shortage in redox supply, caused by genetic or pharmacological means, could increase the antiparasitic potency of HTS01959. This not only suggests a route to experimentally validate our hypothesis but also raises the possibility to design drug combinations displaying synergistic effects (i.e., with drugs that enhance parasite sensitivity to oxidative stress or that increase the demand on redox defenses) (36).

In summary, HTS01959 represents an interesting compound displaying a unique inhibitory mechanism toward validated trypanosomatid target enzymes. Although the efficacy in vivo is moderate, the absence of cytotoxicity for mammalian cells together with the potential for chemical optimization encourage additional research to transform this compound into a more suitable candidate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Triton X-100, NaCl, Tris-HCl, HEPES, DMSO, DTT, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), resazurin, arabinose, catalase, and black solid-bottom polystyrene Corning NBS 384-well plates were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cloning, expression, and purification of MCAs.

All MCAs genes were cloned from the corresponding genomes by PCR with the pGEM-T Easy system (Promega), fused with a glutathione S-transferase tag, and then subcloned into the expression vector pBAD as described previously (11). The oligonucleotides used in the PCR cloning of TbMCA2 and TbMCA3 genes were as follows: TbMCA2 sense primer, AAGCTTCATATGTGCTCCTTAATTACACAACTC; TbMCA3 sense primer, AAGCTTCATATGGCCGTGGACCCAAGGTG; TbMCA2 and TbMCA3 antisense primer, ACTAGTTTGGATAGATCTGTCAACAGAAAAC.

Expression of recombinant MCAs in the Escherichia coli Bl21 Codon Plus (DE3) strain and their purification via glutathione-Sepharose resin were performed as described previously (11). Recombinant protein expression levels in a soluble form were considerably higher for TbMCA2 and TbMCA3 than for TbMCA5. Regarding the profiles obtained after purification, a major band corresponding to the full-length proteins could be observed for TbMCA2 and TbMCA3, while the pattern for TbMCA5 was more complex, with the presence of multiple self-processing products, similar to what has been described for the orthologous proteins of Leishmania major (37) and T. cruzi (3). After purification, T. brucei MCAs were changed to activity buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 8.0], 0.01% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 0.8 mM CaCl2) by using PD-10 desalting columns (GE Healthcare) and were incubated for 3 h at 37°C for preactivation before storage at 4°C.

Optimization of MCA enzymatic assay.

MCA activities were assayed fluorometrically with Z-VRPR-AMC (GenScript) as substrate in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 2 mM DTT, supplemented with 0.01% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (38) and different CaCl2 concentrations (10 mM for Yca1 and 0.8 mM for trypanosomatid MCAs TbMCA2, TbMCA3, TbMCA5, and TcMCA5). Assays (final reaction volume of 40 or 60 µl) were performed at 37°C in solid black 384-well plates (Corning) at fixed enzyme concentrations, as determined by titration with the irreversible inhibitor Z-VRPR-fluoromethyl ketone (FMK) (GenScript) (39). Except when stated otherwise, fluorogenic substrate was added at a final concentration of 75 µM. The release of AMC was monitored continuously for 30 to 60 min with a FilterMax F5 multimode microplate reader (Molecular Devices) using a standard 360-nm excitation/465-nm emission filter set. Enzyme activity was estimated as the slope (dF/dt) of the linear region of the resultant progress curves. Under the described conditions, MCA activity showed no significant changes in the presence of DMSO (0 to 3% [vol/vol]) and was completely abolished by 10 mM EDTA.

The performance of the developed assay was estimated by the Z factor parameter (40) using 16 replicates of enzyme (TbMCA5 with DMSO) and inhibition (TbMCA5 with 10 μM Z-VRPR-FMK) controls according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where μp and μn are the averages of positive and negative controls, respectively, and σp and σn are the standard deviation for each control group.

Compound collections.

GlaxoSmithKline HAT and CHAGAS boxes (13) were received as 10 mM stock solutions in DMSO. A working solution (final concentration of 2 mM) of each compound for primary screening was prepared by 1:5 dilution in DMSO, while 1 µl of the 10 mM stock solution was used for secondary screening of selected compounds (41). Nine compounds from the Maybridge database that had been previously identified by virtual screening as potential inhibitors of the cysteine peptidase falcipain-2 (clan CA) from Plasmodium falciparum (14) were also assessed (stock solutions of 25 mM in DMSO). Working solutions of 2 mM and 10 mM in DMSO were prepared for primary and secondary screening assays, respectively.

Primary screening.

To perform primary screening, 1 μl of each compound (2 mM in DMSO), Z-VRPR-FMK (10 μM in DMSO), or DMSO (negative control) was dispensed into 384-well Corning black solid-bottom assay plates. Then, 30 μl of 1× activity buffer containing TbMCA5 (final concentration of 103 nM in the assay) was added to each well, the plates were agitated, and each well was subjected to a single autofluorescence reading (excitation wavelength, 360 nm; emission wavelength, 465 nm). Plates were incubated in the dark for 1 h at 37°C in a wet chamber, and then 30 μl of activity buffer containing Z-VRPR-AMC (final concentration of 75 μM) was added to each well to start the reaction. After agitation, the fluorescence of AMC was acquired kinetically for each well (12 read cycles, with one cycle every 300 s). Considering our previous experiences (25, 41), the autofluorescence cutoff value was arbitrarily set at 5 × 106 RFU, to discard highly interfering compounds. All compounds were assayed in singlet (without replicates) due to the limited availability of stocks.

Raw screening measurements were used to determine the slope (dF/dt) of progression curves by linear regression for control and compound wells. Percentage of inhibition was calculated for each compound according to equation 2:

| (2) |

where dF/dtwell represents the slope of each compound well and μC+ and μC− represent the averages of TbMCA5 (no-inhibition) and substrate (no-enzyme) controls, respectively.

Secondary assay (dose-response curves).

Twenty-one compounds showing >30% inhibition were selected from primary screening and retested in a dose-response manner (final concentrations ranging from 125 µM to 3.8 pM) using identical assay conditions except for a final volume of 40 µl instead of 60 µl. One microliter of compound stocks (10 mM in DMSO) and Z-VRPR-FMK (10 mM in DMSO) was added to the first well in row 1, followed by addition of 30 μl of activity buffer. After addition of 15 μl of the same buffer to subsequent wells, 2-fold serial dilutions were made. Then 15 μl of activity buffer containing TbMCA5 was added to each well except for C− wells, which were completed with 15 μl of activity buffer. After agitation, 60 min of incubation at 37°C, and autofluorescence measurement, 10 μl of activity buffer containing Z-VRPR-AMC substrate was added to the mixture. Data collection and processing were performed exactly as described above. The percentage of TbMCA5 residual activity was calculated for each condition according to equation 3:

| (3) |

where dF/dtwell represents the slope of each compound well and μC+ and μC− represent the averages of enzyme (no-inhibition) and substrate (no-enzyme) controls, respectively. The IC50 and Hill slope parameters for each compound were estimated by fitting the four-parameter Hill equation to experimental data from dose-response curves using the GraphPad Prism program (version 5.03).

Specificity assay with prototypic enzymes from different mechanistic classes.

Cruzipain (EC 3.4.22.51) and falcipain-2 (MEROPS identification number C01.046) were obtained and assessed as described previously (17, 25). Purified rabbit lung angiotensin-1-converting enzyme (ACE) (EC 3.4.15.1) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and evaluated as described (42). Chymotrypsin (EC 3.4.21.1) and pepsin (EC 3.4.23.1) were commercially obtained (Sigma-Aldrich) and assessed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The substrates, inhibitors, and wavelengths used are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Substrates and inhibitors used

| Enzyme | Source | Substratea | Excitation/emission wavelengths (nm) | Classic inhibitor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TbMCA2 | Recombinant | Z-VRPR-AMC | 350/460 | Z-VRPR-FMK |

| TbMCA3 | Recombinant | Z-VRPR-AMC | 350/460 | Z-VRPR-FMK |

| TbMCA5 | Recombinant | Z-VRPR-AMC | 350/460 | Z-VRPR-FMK |

| TcMCA5 | Recombinant | Z-VRPR-AMC | 350/460 | Z-VRPR-FMK |

| Yca1 | Recombinant | Z-VRPR-AMC | 350/460 | Z-VRPR-FMK |

| Cruzipain | Natural | Z-FR-AMC | 350/460 | E64 |

| Falcipain-2 | Recombinant | Z-FR-AMC | 350/460 | E64 |

| Chymotrypsin | Commercial | Suc-AAPF-AMC | 350/460 | PMSF |

| ACE | Commercial | Abz-FRK-DPN-P-OH | 320/420 | Captopril |

| Pepsin | Commercial | Moc-Ac-APAKFFRLK-DPN-NH2 | 330/393 | Pepstatin |

DPN, 2,4-dinitrophenyl; Suc, succinyl; Abz, 2-aminobenzoyl; Moc-Ac, (7-Methoxycoumarin-4-yl)acetyl.

Determining reversibility and mode of inhibition.

The reversibility and time dependence of TbMCA2 inhibition by HTS01959 were assayed as described previously (43). In brief, HTS01959 (200 µM [∼50× IC50]) and TbMCA2 (770 nM [∼100× optimal assay concentration]) were incubated at 37°C for 60 min in activity buffer. The mixture was diluted 100-fold into 40 µl of Z-VRPR-AMC (75 µM in activity buffer) preincubated at the same temperature in a 384-well plate. Immediately after mixing, AMC fluorescence (excitation wavelength, 360 nm; emission wavelength, 465 nm) was continuously monitored every minute for 1 h. Z-VRPR-FMK (40 nM [∼20× IC50]) was used as a control for irreversible inhibition. For the TbMCA2 control, the equivalent volume of DMSO vehicle was preincubated with the enzyme.

To determine the kinetics of inhibition onset, TbMCA2 (final concentration of 7.7 nM) was added to a reaction mixture (final volume of 40 µl), previously equilibrated at 37°C, containing activity buffer, HTS01959 (50 µM), and Z-VRPR-AMC (75 µM). Immediately after mixing, AMC release was monitored as indicated above.

The mode of inhibition of HTS01959 was determined as described previously (17). In brief, TbMCA2 activity was determined for at least six different substrate concentrations (ranging from 62.5 µM to 2.5 mM) in the absence and presence of a reduced set (four) of HTS01959 concentrations selected (i) to include the IC50 value at each substrate condition and (ii) to cover the wider inhibition range (∼10 to 90%) in the central stretch of the dose-response curve. Data were rearranged to estimate the percentage of TbMCA2 residual activity for each condition, and the IC50 and Hill slope values were estimated by fitting experimental data to the four-parameter Hill equation by using GraphPad Prism.

Effect of redox potential in the inhibition of TbMCA2 by HTS01959.

To analyze the effect of redox potential in the inhibitory activity of HTS01959, dose-response curves were constructed for at least eight inhibitor concentrations as described above. Assays were performed in activity buffer containing different concentrations of DTT (0.1 to 20 mM), l-cysteine (0.1 to 10 mM), or β-mercaptoethanol (10 mM). Resultant dose-response curves were fitted as indicated previously to estimate the IC50 and Hill slope values.

Hydrogen peroxide generation assay.

To detect the formation of hydrogen peroxide, we used a commercial kit for glycemia testing (Wiener lab.) following instructions from the manufacturer. Briefly, samples were incubated as indicated to (potentially) generate H2O2. Resultant H2O2 reacts with 4-aminofenazone and 4-hydroxybenzoate in the presence of HRPO to form red quinonimine. The increase in absorbance at 505 nm was measured with a FilterMax microplate reader.

Mammalian cell culture.

Vero cells were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere using minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Natocor), 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma), and 100 U/ml penicillin (Sigma).

Effect of HTS01959 on T. brucei bloodstream forms.

T. brucei parasites were added to black 96-well plates (half area) to a final density of 10,000 parasites/ml (final volume of 125 μl) in HMI-9 medium supplemented with G418 antibiotic (2 µg/ml) and 10% (vol/vol) FBS and containing different concentrations of HTS01959 (up to 130 µM) or DMSO (up to 0.5% [vol/vol]). Cultures were incubated for 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. For viability detection, 12.5 μl of 10× resazurin sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline was added to each well (final concentration of 44 μM) and plates were incubated for another 5 h in the dark. The fluorescence of the resorufin product was determined (excitation wavelength, 530 to 570 nm; emission wavelength, 590 to 620 nm) using a FilterMax microplate reader. Raw measurements were normalized by using 0.5% (vol/vol) DMSO and 50 μM nifurtimox controls (100% and 0% viability, respectively) to estimate the percent viability for each condition to construct dose-response curves. The IC50 value was estimated by fitting experimental data to the four-parameter Hill equation by using GraphPad Prism.

Effect of HTS01959 on T. cruzi trypomastigotes.

Cell-derived T. cruzi trypomastigotes were cultured by passage in Vero cells at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in MEM (Gibco Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin. For dose-response curves, samples enriched in trypomastigotes were obtained by the swimming-up method (44). Parasite suspension (125 μl at 8 × 106 parasites/ml) was added to black 96-well plates (half area) and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 with different concentrations of HTS01959 (ranging from 16 µM up to 130 µM) or DMSO (up to 0.5% [vol/vol]). After incubation, viability for each condition was estimated with resazurin, as described above.

Trypanosoma cruzi intracellular imaging assay.

To evaluate the effect of HTS01959 on amastigote replication, 10,000 Vero cells/well were seeded in a 24-well multiwell plate. After 48 h of growth, cells were infected for 4 h with T. cruzi trypomastigotes at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Then, trypomastigotes were removed by medium aspiration, and fresh medium containing 130 µM HTS01959 was added. After 48 h of incubation, samples were fixed with 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (100 µg/ml) for 1 h. After a final wash with phosphate-buffered saline, the coverslips were mounted with FluorSave reagent. Samples were observed by microscopy with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope, and 30 photos were taken for each sample using a 40× objective. Images were analyzed using ImageJ to identify Vero cell nuclei and parasite nuclei/kinetoplasts. The total number of Vero cells, the number of infected cells, and the number of amastigotes per Vero cell were compared by using GraphPad Prism.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Uren AG, O’Rourke K, Aravind LA, Pisabarro MT, Seshagiri S, Koonin EV, Dixit VM. 2000. Identification of paracaspases and metacaspases: two ancient families of caspase-like proteins, one of which plays a key role in MALT lymphoma. Mol Cell 6:961–967. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minina EA, Staal J, Alvarez VE, Berges JA, Berman-Frank I, Beyaert R, Bidle KD, Bornancin F, Casanova M, Cazzulo JJ, Choi CJ, Coll NS, Dixit VM, Dolinar M, Fasel N, Funk C, Gallois P, Gevaert K, Gutierrez-Beltran E, Hailfinger S, Klemenčič M, Koonin EV, Krappmann D, Linusson A, Machado MFM, Madeo F, Megeney LA, Moschou PN, Mottram JC, Nyström T, Osiewacz HD, Overall CM, Pandey KC, Ruland J, Salvesen GS, Shi Y, Smertenko A, Stael S, Ståhlberg J, Suárez MF, Thome M, Tuominen H, Van Breusegem F, van der Hoorn RAL, Vardi A, Zhivotovsky B, Lam E, Bozhkov PV. 2020. Classification and nomenclature of metacaspases and paracaspases: no more confusion with caspases. Mol Cell 77:927–929. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laverrière M, Cazzulo JJ, Alvarez VE. 2012. Antagonic activities of Trypanosoma cruzi metacaspases affect the balance between cell proliferation, death and differentiation. Cell Death Differ 19:1358–1369. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss CX, Westrop GD, Juliano L, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. 2007. Metacaspase 2 of Trypanosoma brucei is a calcium-dependent cysteine peptidase active without processing. FEBS Lett 581:5635–5639. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe N, Lam E. 2011. Calcium-dependent activation and autolysis of Arabidopsis metacaspase 2d. J Biol Chem 286:10027–10040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez VE, Niemirowicz GT, Cazzulo JJ. 2013. Metacaspases, autophagins and metallocarboxypeptidases: potential new targets for chemotherapy of the trypanosomiases. Curr Med Chem 20:3069–3077. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320250004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mottram JC, Helms MJ, Coombs GH, Sajid M. 2003. Clan CD cysteine peptidases of parasitic protozoa. Trends Parasitol 19:182–187. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proto WR, Castanys-Munoz E, Black A, Tetley L, Moss CX, Juliano L, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. 2011. Trypanosoma brucei metacaspase 4 is a pseudopeptidase and a virulence factor. J Biol Chem 286:39914–39925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.292334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helms MJ, Ambit A, Appleton P, Tetley L, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. 2006. Bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei depend upon multiple metacaspases associated with RAB11-positive endosomes. J Cell Sci 119:1105–1117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosec G, Alvarez VE, Agüero F, Sánchez D, Dolinar M, Turk B, Turk V, Cazzulo JJ. 2006. Metacaspases of Trypanosoma cruzi: possible candidates for programmed cell death mediators. Mol Biochem Parasitol 145:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouvier LA, Niemirowicz GT, Salas-Sarduy E, Cazzulo JJ, Alvarez VE. 2018. DNA-damage inducible protein 1 is a conserved metacaspase substrate that is cleaved and further destabilized in yeast under specific metabolic conditions. FEBS J 285:1097–1110. doi: 10.1111/febs.14390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg M, Van der Veken P, Joossens J, Muthusamy V, Breugelmans M, Moss CX, Rudolf J, Cos P, Coombs GH, Maes L, Haemers A, Mottram JC, Augustyns K. 2010. Design and evaluation of Trypanosoma brucei metacaspase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 20:2001–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peña I, Pilar Manzano M, Cantizani J, Kessler A, Alonso-Padilla J, Bardera AI, Alvarez E, Colmenarejo G, Cotillo I, Roquero I, de Dios-Anton F, Barroso V, Rodriguez A, Gray DW, Navarro M, Kumar V, Sherstnev A, Drewry DH, Brown JR, Fiandor JM, Julio Martin J. 2015. New compound sets identified from high throughput phenotypic screening against three kinetoplastid parasites: an open resource. Sci Rep 5:8771. doi: 10.1038/srep08771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-González JE, Salas-Sarduy E, Hernández Ramírez LF, Pascual MJ, Álvarez DE, Pabón A, Leite VBP, Pascutti PG, Valiente PA. 2018. Identification of (4-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)piperazin-1-yl)methanone derivatives as falcipain 2 inhibitors active against Plasmodium falciparum cultures. Biochim Biophys Acta 1862:2911–2923. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vercammen D, Belenghi B, van de Cotte B, Beunens T, Gavigan J-A, De Rycke R, Brackenier A, Inzé D, Harris JL, Van Breusegem F. 2006. Serpin1 of Arabidopsis thaliana is a suicide inhibitor for metacaspase 9. J Mol Biol 364:625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selwyn MJ. 1965. A simple test for inactivation of an enzyme during assay. Biochim Biophys Acta 105:193–195. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6593(65)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberca LN, Chuguransky SR, Álvarez CL, Talevi A, Salas-Sarduy E. 2019. In silico guided drug repurposing: discovery of new competitive and non-competitive inhibitors of falcipain-2. Front Chem 7:534. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLuskey K, Rudolf J, Proto WR, Isaacs NW, Coombs GH, Moss CX, Mottram JC. 2012. Crystal structure of a Trypanosoma brucei metacaspase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:7469–7474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200885109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne N, Auld DS, Inglese J. 2010. Apparent activity in high-throughput screening: origins of compound-dependent assay interference. Curr Opin Chem Biol 14:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston PA. 2011. Redox cycling compounds generate H2O2 in HTS buffers containing strong reducing reagents: real hits or promiscuous artifacts? Curr Opin Chem Biol 15:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandana, Dixit R, Tiwari R, Katyal A, Pandey KC. 2019. Metacaspases: potential drug target against protozoan parasites. Front Pharmacol 10:790. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Chagas disease: epidemiology and risk factors. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/epi.html.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Leishmaniasis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. DPDx: trypanosomiasis, African. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisafrican.

- 25.Salas-Sarduy E, Landaburu LU, Karpiak J, Madauss KP, Cazzulo JJ, Agüero F, Alvarez VE. 2017. Novel scaffolds for inhibition of cruzipain identified from high-throughput screening of anti-kinetoplastid chemical boxes. Sci Rep 7:12073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12170-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riant O, Hannedouche J. 2007. Asymmetric catalysis for the construction of quaternary carbon centres: nucleophilic addition on ketones and ketimines. Org Biomol Chem 5:873–888. doi: 10.1039/b617746h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg K, Schroer K, Lütz S, Liese A. 2007. Biocatalytic ketone reduction: a powerful tool for the production of chiral alcohols–part I: processes with isolated enzymes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Lefers RC, Brough EL, Gurka DP. 1984. Metabolism of alcohol and ketone by cytochrome P-450 oxygenase: fluoren-9-ol in equilibrium with fluoren-9-one. Drug Metab Dispos 12:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habe H, Chung J-S, Kato H, Ayabe Y, Kasuga K, Yoshida T, Nojiri H, Yamane H, Omori T. 2004. Characterization of the upper pathway genes for fluorene metabolism in Terrabacter sp. strain DBF63. J Bacteriol 186:5938–5944. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5938-5944.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlecker T, Comini MA, Melchers J, Ruppert T, Krauth-Siegel RL. 2007. Catalytic mechanism of the glutathione peroxidase-type tryparedoxin peroxidase of Trypanosoma brucei. Biochem J 405:445–454. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Budde H, Flohé L, Hecht H-J, Hofmann B, Stehr M, Wissing J, Lünsdorf H. 2003. Kinetics and redox-sensitive oligomerisation reveal negative subunit cooperativity in tryparedoxin peroxidase of Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Biol Chem 384:619–633. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manta B, Bonilla M, Fiestas L, Sturlese M, Salinas G, Bellanda M, Comini MA. 2018. Polyamine-based thiols in trypanosomatids: evolution, protein structural adaptations, and biological functions. Antioxid Redox Signal 28:463–486. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forman HJ, Maiorino M, Ursini F. 2010. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry 49:835–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caldas IS, Santos EG, Novaes RD. 2019. An evaluation of benznidazole as a Chagas disease therapeutic. Expert Opin Pharmacother 20:1797–1807. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1650915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patterson S, Fairlamb AH. 2019. Current and future prospects of nitro-compounds as drugs for trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Curr Med Chem 26:4454–4475. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180426164352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babokhov P, Sanyaolu AO, Oyibo WA, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Iriemenam NC. 2013. A current analysis of chemotherapy strategies for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Pathog Glob Health 107:242–252. doi: 10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.González IJ, Desponds C, Schaff C, Mottram JC, Fasel N. 2007. Leishmania major metacaspase can replace yeast metacaspase in programmed cell death and has arginine-specific cysteine peptidase activity. Int J Parasitol 37:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadhav A, Ferreira RS, Klumpp C, Mott BT, Austin CP, Inglese J, Thomas CJ, Maloney DJ, Shoichet BK, Simeonov A. 2010. Quantitative analyses of aggregation, autofluorescence, and reactivity artifacts in a screen for inhibitors of a thiol protease. J Med Chem 53:37–51. doi: 10.1021/jm901070c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. 1999. Caspases: preparation and characterization. Methods 17:313–319. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KK. 1999. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salas-Sarduy E, Landaburu LU, Carmona AK, Cazzulo JJ, Agüero F, Alvarez VE, Niemirowicz GT. 2019. Potent and selective inhibitors for M32 metallocarboxypeptidases identified from high-throughput screening of anti-kinetoplastid chemical boxes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmona AK, Schwager SL, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Sturrock ED. 2006. A continuous fluorescence resonance energy transfer angiotensin I-converting enzyme assay. Nat Protoc 1:1971–1976. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Copeland RA. 2005. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. a guide for medicinal chemists and pharmacologists. Methods Biochem Anal 46:1–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ortega-Rodriguez U, Portillo S, Ashmus RA, Duran JA, Schocker NS, Iniguez E, Montoya AL, Zepeda BG, Olivas JJ, Karimi NH, Alonso-Padilla J, Izquierdo L, Pinazo M-J, de Noya BA, Noya O, Maldonado RA, Torrico F, Gascon J, Michael K, Almeida IC. 2019. Purification of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucins from Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes and synthesis of α-Gal-containing neoglycoproteins: application as biomarkers for reliable diagnosis and early assessment of chemotherapeutic outcomes of Chagas disease. Methods Mol Biol 1955:287–308. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9148-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.