Abstract

Background

Psychosis is an illness characterised by the presence of hallucinations and delusions that can cause distress or a marked change in an individual's behaviour (e.g. social withdrawal, flat or blunted affect). A first episode of psychosis (FEP) is the first time someone experiences these symptoms that can occur at any age, but the condition is most common in late adolescence and early adulthood. This review is concerned with first episode psychosis (FEP) and the early stages of a psychosis, referred to throughout this review as 'recent‐onset psychosis.'

Specialised early intervention (SEI) teams are community mental health teams that specifically treat people who are experiencing, or have experienced a recent‐onset psychosis. The purpose of SEI teams is to intensively treat people with psychosis early in the course of the illness with the goal of increasing the likelihood of recovery and reducing the need for longer‐term mental health treatment. SEI teams provide a range of treatments including medication, psychotherapy, psychoeducation, and occupational, educational and employment support, augmented by assertive contact with the service user and small caseloads. Treatment is time limited, usually offered for two to three years, after which service users are either discharged to primary care or transferred to a standard adult community mental health team. A previous Cochrane Review of SEI found preliminary evidence that SEI may be superior to standard community mental health care (described as 'treatment as usual (TAU)' in this review) but these recommendations were based on data from only one trial. This review updates the evidence for the use of SEI services.

Objectives

To compare specialised early intervention (SEI) teams to treatment as usual (TAU) for people with recent‐onset psychosis.

Search methods

On 3 October 2018 and 22 October 2019, we searched Cochrane Schizophrenia's study‐based register of trials, including registries of clinical trials.

Selection criteria

We selected all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing SEI with TAU for people with recent‐onset psychosis. We entered trials meeting these criteria and reporting useable data as included studies.

Data collection and analysis

We independently inspected citations, selected studies, extracted data and appraised study quality. For binary outcomes we calculated the risk ratios (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes we calculated the mean difference (MD) and their 95% CIs, or if assessment measures differed for the same construct, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created a 'Summary of findings' table using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included three RCTs and one cluster‐RCT with a total of 1145 participants. The mean age in the trials was between 23.1 years (RAISE) and 26.6 years (OPUS). The included participants were 405 females (35.4%) and 740 males (64.6%). All trials took place in community mental healthcare settings.

Two trials reported on recovery from psychosis at the end of treatment, with evidence that SEI team care may result in more participants in recovery than TAU at the end of treatment (73% versus 52%; RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.97; 2 studies, 194 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

Three trials provided data on disengagement from services at the end of treatment, with fewer participants probably being disengaged from mental health services in SEI (8%) in comparison to TAU (15%) (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.79; 3 studies, 630 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

There was low‐certainty evidence that SEI may result in fewer admissions to psychiatric hospital than TAU at the end of treatment (52% versus 57%; RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.00; 4 studies, 1145 participants) and low‐certainty evidence that SEI may result in fewer psychiatric hospital days (MD ‐27.00 days, 95% CI ‐53.68 to ‐0.32; 1 study, 547 participants).

Two trials reported on general psychotic symptoms at the end of treatment, with no evidence of a difference between SEI and TAU, although this evidence is very uncertain (SMD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐4.58 to 3.75; 2 studies, 304 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). A different pattern was observed in assessment of general functioning with an end of trial difference that may favour SEI (SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.66; 2 studies, 467 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

It was uncertain whether the use of SEI resulted in fewer deaths due to all‐cause mortality at end of treatment (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.20; 3 studies, 741 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

There was low risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment in three of the four included trials; the remaining trial had unclear risk of bias. Due to the nature of the intervention, we considered all trials at high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel. Two trials had low risk of bias and two trials had high risk of bias for blinding of outcomes assessments. Three trials had low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data, while one trial had high risk of bias. Two trials had low risk of bias, one trial had high risk of bias, and one had unclear risk of bias for selective reporting.

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence that SEI may provide benefits to service users during treatment compared to TAU. These benefits probably include fewer disengagements from mental health services (moderate‐certainty evidence), and may include small reductions in psychiatric hospitalisation (low‐certainty evidence), and a small increase in global functioning (low‐certainty evidence) and increased service satisfaction (moderate‐certainty evidence). The evidence regarding the effect of SEI over TAU after treatment has ended is uncertain. Further evidence investigating the longer‐term outcomes of SEI is needed. Furthermore, all the eligible trials included in this review were conducted in high‐income countries, and it is unclear whether these findings would translate to low‐ and middle‐income countries, where both the intervention and the comparison conditions may be different.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Young Adult, Bias, Community Mental Health Services, Early Medical Intervention, Early Medical Intervention/methods, Hospitalization, Hospitalization/statistics & numerical data, Psychotic Disorders, Psychotic Disorders/therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Is recent‐onset psychosis best treated by a specialist mental health team?

What is psychosis?

Psychosis describes conditions affecting the mind, in which people have trouble distinguishing what is real from what is not real. This might involve seeing or hearing things that other people cannot see or hear (hallucinations), or believing things that are not true (delusions). The combination of hallucinations and delusional thinking can cause severe distress and a change in behaviour. A first episode psychosis is the first time a person experiences an episode of psychosis. Recent‐onset psychosis is the first few years of the illness after someone experiences it for the first time.

Psychosis is treatable

Many people recover from a first episode and never experience another psychotic episode. Mental health professionals assess a person before recommending a specific treatment. Depending on the services available, they may send people for treatment to:

‐ a community mental health team: mental health professionals who support people with complex mental health conditions;

‐ a crisis resolution team: mental health professionals who treat people who would otherwise need treatment in hospital; or

‐ an early intervention team: mental health professionals who work with people who are currently or have recently experienced their first episode of psychosis.

Early intervention teams specialise in treating recent‐onset psychosis, and aim to treat it as quickly and intensively as possible.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to find out whether specialist early intervention teams were more successful at treating recent‐onset psychosis than outpatient or community mental health teams that do not specialise in treating it.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated the use of early intervention teams to treat recent‐onset psychosis compared with standard community mental health care.

We looked for randomised controlled studies, in which the treatments people received were decided at random. This type of study usually gives the most reliable evidence about the effects of a treatment.

We wanted to find out, at the end of the treatment:

‐ how many people recovered;

‐ how many people stopped their treatment too soon;

‐ how many people were admitted to a psychiatric hospital, and for how long;

‐ the state of people's general mental health and functioning (how well they coped with daily life); and

‐ how many people died.

Search date: we included evidence published up to 22 October 2019.

What we found

We found four studies in 1145 people (65% men; average age 23 to 26 years) with recent‐onset psychosis. The studies compared treatment by specialist early intervention teams against 'usual treatment' (treatment by community health or outpatient mental health teams).

The studies took place in community mental health services in high‐income countries: Denmark, Sweden, the UK and the USA. The studies lasted from 18 to 24 months.

What are the results of our review?

Compared with usual treatment, treatment by an early intervention team:

‐may help more people recover from psychosis (2 studies; 194 people);

‐ probably reduces how many people stop their treatment too soon (3 studies; 630 people);

‐ may reduce the number of people admitted to a psychiatric hospital (4 studies; 1145 people)

‐ may reduce the time spent in a psychiatric hospital (1 study; 547 people); and

‐ may moderately improve people's general functioning (2 studies; 467 people).

We were uncertain about whether treatment by an early intervention team affects general psychotic symptoms (2 studies; 304 people), or its effect on how many people died (3 studies; 741 people).

How reliable are these results?

We are moderately confident that treatment by an early intervention team probably reduces the number of people who stop treatment too soon, although this result may change when more evidence is available.

We are less confident about how many people recover from psychosis, or are admitted to a psychiatric hospital, how long they stay in hospital, and any improvements in people's general functioning. These results are likely to change when more evidence is available.

Key message

Using specialist early intervention teams to treat recent‐onset psychosis is likely to have benefits, such as more people continuing with their treatment, and increasing the number of people who recover.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Specialised early intervention (SEI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) for recent‐onset psychosis at end of treatment.

| SEI compared to TAU for recent‐onset psychosis at end of treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: recent‐onset psychosis (less than three years since the start of psychotic symptoms and either first or second psychotic episode) Setting: community mental health Intervention: specialised early intervention team care Comparison: treatment as usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with TAU | Risk with SEI | |||||

| Global state: recovery (assessed by proportion recovered, as defined by the study, at end of treatment) | Study population | RR 1.41 (1.01 to 1.97) | 194 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ||

| 516 per 1000 | 728 per 1000 (521 to 1000) | |||||

| Service use: disengagement from services (assessed by proportion disengaged, as defined by the study, at end of treatment) | Study population | RR 0.50 (0.31 to 0.79) | 630 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | ||

| 150 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (47 to 119) | |||||

| Service use: admission to psychiatric hospital (assessed by proportion admitted at end of treatment) | Study population | RR 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 1145 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | ||

| 566 per 1000 | 515 per 1000 (464 to 566) | |||||

| Service use: number of days in psychiatric hospital (assessed by mean number of days in hospital at end of treatment) | The mean number of days in psychiatric hospital (end of treatment) in the TAU group was 123 days | MD 27 days fewer (53.68 fewer to 0.32 fewer) | ‐ | 547 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | |

|

Mental state: average endpoint score on a general mental state scale (general psychopathology, assessed by PANNS at end of treatment)g |

‐ | SMD 0.41 points lower (4.58 lower to 3.75 higher) | ‐ | 304 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d,e | SMD of 0.50 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988) |

| Death: all‐cause mortality (assessed by proportion deceased at end of treatment) | Study population | RR 0.21 (0.04 to 1.20) | 741 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowf | ||

| 19 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (1 to 23) | |||||

| Functioning: average endpoint score on general functioning scale (global functioning, assessed by questionnaire at end of treatment) | ‐ | SMD 0.37 points higher (0.07 higher to 0.66 higher) | ‐ | 467 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | SMD of 0.50 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SEI: specialised early intervention; TAU: treatment as usual | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to indirectness. Use of surrogate outcome. Outcome assessment differs between trials. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Wide confidence intervals. cDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. Non‐blinded trials with subjective outcome, where outcomes assessor was either not blinded or allocation could easily be guessed by assessor. dDowngraded one level due to indirectness. Average scores from scales used to measure outcome instead of clinically important change. eDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. Few events, wide confidence intervals and small sample size. fDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Few events and wide confidence intervals. g Both studies used the PANNS scale to measure general psychopathology, but the LEO trial used an edited version with a smaller score range.

Background

Description of the condition

The lifetime prevalence of psychotic illness is estimated to be 4 per 1000 of the population, with first episode psychosis (FEP) incidence estimated at 34 new cases per 100,000 person‐years (Kirkbride 2012; Kirkbride 2017). Psychosis can occur at any age, but most people develop it in late adolescence and early adulthood, with a mean age of onset in the early twenties (Kirkbride 2017). Features of psychosis include hallucinations, delusions and disordered thinking (referred to as positive symptoms) and social withdrawal, flat or blunted affect, and poverty of speech (referred to as negative symptoms) (APA 2013). Psychotic illness encompasses a range of diagnoses, including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar affective disorder and psychotic depression (WHO 2018). The impact on the individual is often significant; a psychotic illness has wide‐ranging implications on quality of life and disability, including effects on physical health, social functioning, social inclusion, and education and employment (Mason 1995; Meltzer 2002).

There is no consensus on the definition of FEP (Breitborde 2009). There may be a considerable delay between the onset of a person's symptoms and their being referred to, and treated by, mental health services (Birchwood 2013). The pathways to care for people with psychosis can also often involve multiple failed attempts at obtaining treatment before mental health services are able to successfully start a treatment regime (Lincoln 1998). As a result, clinical services and research studies use proxy measures for FEP. These are most commonly a 'duration criteria' (e.g. less than three years since first onset of symptoms), a 'contact with mental health services' criteria (e.g. first contact with mental health services), or an initiation of antipsychotic medication criteria (e.g. no more than 6 months of antipsychotic prescriptions). In this review, we will refer to FEP and the early stages of a psychosis as 'recent‐onset psychosis' in order to capture this uncertainty.

Schizophrenia and related psychotic illnesses are major contributors to the global burden of disease, with the associated annual economic costs estimated to range between USD 94 million and USD 102 billion by country (Chong 2016; Murray 1996). People with recent‐onset psychosis can reach remission of psychotic symptoms and functional recovery following an episode of psychosis, but many relapse, and as the number of relapses increases, the likelihood of remission decreases (Morgan 2014; Wiersma 1998). Recent studies have challenged the historically orthodox view that the course of a psychotic illness is deteriorating and progressive. A meta‐analysis on recovery after a first episode of psychosis estimated a 58% rate of remission and a 38% rate of recovery (Lally 2017). Long‐term outcome studies have also shown high rates of symptomatic recovery and (to a lesser extent) functional and social recovery in people being treated for recent‐onset psychosis (Revier 2015).

The growing optimism of remission and recovery following a psychotic episode has been complemented by services with a strong recovery‐oriented purpose that aim to intensively and assertively treat those with early psychosis in order to improve and enhance this recovery (Singh 2017).

Description of the intervention

A specialised early intervention (SEI) service is a phase‐specific multidisciplinary community mental health team that treats people experiencing, or who have recently experienced, their first episode of a psychotic illness (Fusar‐Poli 2017). The objectives of SEI services are two‐fold: first, they aim to intervene at an early stage of the illness, reducing the duration of untreated psychosis; second, they aim to provide a comprehensive package of treatment including medication, psychological therapies, and patient and family education, all backed by assertive case management (NICE 2014). The service model is of standalone, multidisciplinary community teams that provide an assertive outreach model of care, with care co‐ordinators having a restricted caseload size to enable them to work intensively with patients and engage them in treatment (RCPsych 2016). The aim of SEI is to reduce impairment and facilitate recovery, and in turn, improve prognosis.

SEI services are time‐limited to two or three years of treatment (depending on region and health service provision), with the rationale that early intensive treatment will preclude the need for such intensive treatment on an ongoing basis (i.e. a secondary prevention approach).

How the intervention might work

One of the most vocal arguments for the development of early phase treatments is that there is evidence of a 'critical period' in FEP (Birchwood 1998). This period, during the first few years of a psychotic illness, is potentially a period of rapid biological, psychological, and social changes, after which is followed by an eventual plateau of illness severity and functioning (Birchwood 1998). This trajectory of fluctuation of illness in the early years, followed by gradual deterioration has been found to be strongly predictive of later outcomes (Harrison 2001; Wiersma 1998). Standard community mental health teams had particular difficulty engaging this population, making it more challenging to deliver treatment (Birchwood 2014). SEI was developed primarily to improve engagement through assertive outreach, reducing the time to treatment (thereby reducing the duration of untreated psychosis) and potentially minimising the long‐term burden of the illness (Fusar‐Poli 2017). It is not clear however, whether SEI prevents poor outcomes, or alternatively, prevents poor outcomes only as long as SEI treatment is given.

Why it is important to do this review

SEI services are now considered the gold standard of care for people with recent‐onset psychosis in the UK, USA, Europe, and Australasia. In the UK it is the recommended treatment by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2014), and timely access to SEI was the first National Health Service (NHS) waiting time standard for mental health care (NHS England 2015). Despite their widespread use, a previous Cochrane Review of early interventions for psychosis only found one eligible randomised control trial (RCT) of specialist team interventions for recent‐onset psychosis (Marshall 2011). A number of new RCTs comparing various forms of SEI to treatment as usual (TAU) have since been published (for example, GET UP PIANO 2013 and Kane 2016), and a recent meta‐analysis of SEI in the treatment of 'early phase psychosis', which included trials that recruited participants with multiple acute psychotic episodes or people who had already had lengthy community treatment (e.g. up to five years), found SEI superior to standard community mental health care in reducing treatment discontinuation, admission to psychiatric hospital, and psychotic symptoms (Correll 2018). It is important to do this review to ensure that new evidence for SEI services is evaluated.

Objectives

To compare specialised early intervention (SEI) teams to treatment as usual (TAU) for people with recent‐onset psychosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) regardless of blinding, but excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those that allocated interventions by alternate days of the week. Given the nature of the intervention, it would have been difficult to blind participants and clinicians from whether they were receiving the intervention or control condition and so we included both single‐ and double‐blinded studies. Where people were given additional treatments as well as specialised early intervention (SEI) for recent‐onset psychosis, we only included data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the SEI teams that were randomised. We did not exclude studies offering alternative models of care, such as step‐down care, following discharge from the early intervention team.

Types of participants

SEI services are designed to treat people in the early stages of psychosis. Exact eligibility criteria for services often differ both within and between regions and countries, but generally have a ‘time since onset' criterion and a ‘number of onsets’ criterion. We included participants who were within three years of the onset of their first psychotic episode (time since onset) with a first or second episode of psychosis (number of onsets). We included participants who were exhibiting symptoms that matched the criteria for primary psychotic diagnoses according to standardised criteria, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), DSM‐5 (APA 2013), ICD‐10 (WHO 2004), ICD‐11 (WHO 2018) or Melbourne Criteria (Yung 2008). We excluded trials where participants had organic psychoses or head injury, and studies that recruited participants with prodromal symptoms (also known as 'at‐risk mental states') who had not yet transitioned to a psychotic episode. We also excluded trials that included participants whose onset of illness is longer than three years, unless we could extract data on only the eligible participants.

Types of interventions

Specialised early intervention (SEI) team care

These are multidisciplinary, standalone, community‐based mental health teams that take referrals for patients who have recent‐onset psychosis. SEI teams are an alternative, rather than an addition, to standard psychiatric care.

In order to be defined as a SEI service, the intervention had to provide the following.

Be multidisciplinary, standalone community‐based mental health teams that take referrals for patients who have recent‐onset psychosis and which is an alternative to, rather than an addition to, standard psychiatric care. Teams can share facilities with other health providers (for example, a community mental health team) but must operate independently from them. For example, having a separate caseload, separate team meetings, and a dedicated programme specifically aimed at the recent‐onset psychosis caseload.

Provide a package of treatment options that could include (but is not limited to) medication, psychological therapies, psychoeducation to the service user and carers, employment support, and physical health interventions (e.g. smoking cessation, physical health checks). These should be structured around regular, assertive outreach.

Accept service users on to the caseload who are in the first or second episode of psychosis and are within three years of the onset of their psychosis.

Treatment as usual (TAU)

TAU for people with recent‐onset psychosis differs by country, but usually consists of a community‐based or outpatient mental health team that does not provide specialist, phase‐specific (i.e. centred on the early phase of a psychotic illness) treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Timing of outcome assessment

We recorded post‐treatment outcomes and any available outcomes reported at follow‐up time points. Where appropriate, and if the data were available, we aimed to categorise treatment outcomes into end of treatment, medium‐term follow‐up (1 to 60 months post‐intervention), and long‐term follow‐up (longer than 60 months post‐intervention).

Primary outcomes

-

Global state

Recovery, as defined by the study

-

Service use

Disengagement from services, as defined by the study

Secondary outcomes

-

Service use

Admission to psychiatric hospital

Readmission to psychiatric hospital

Number of days in psychiatric hospital

-

Global state

Relapse, as defined by the study

-

Mental state

-

General

Clinically important change in general mental state

Any change in general mental state

Average endpoint/change score on a general mental state scale

-

Specific

Clinically important change in positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking), as defined by individual studies

Any change in positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking), as defined by individual studies

Clinically important change in negative symptoms (avolition, poor self‐care, blunted affect), as defined by individual studies

Any change in negative symptoms (avolition, poor self‐care, blunted affect), as defined by individual studies

Clinically important change in depression, as defined by individual studies

Any change in depression, as defined by individual studies

Average endpoint/change score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale

-

-

Behaviour

Specific

Occurrence of violent incidents (to self, others or property)

-

Adverse effects/events

-

General

At least one adverse effect/event

Average endpoint/change score on adverse effect scale

-

Specific

Incidence of any specific adverse effects, as defined by individual studies

-

-

Leaving the study early

For any reason

Due to adverse effect

-

Quality of life (recipient or informal carers or professional carers)

-

Overall

Clinically important change in overall quality of life

Average endpoint/change score on quality of life scale

-

-

Functioning

-

General

Clinically important change in general functioning

Average endpoint/change score on general functioning scale

-

Specific (including social, cognitive, life skills)

Clinically important change in specific functioning

Average endpoint/change score on specific functioning scale

Any change in educational status

Any change in employment status

-

-

Satisfaction with care (including subjective well‐being and family burden)

-

Recipient

Recipient satisfied with care

Average endpoint/change score on satisfaction scale

-

Carers

Carer satisfied with care

Average endpoint/change score on satisfaction scale

-

'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011); and used GRADEpro GDT to export data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) to create a 'Summary of findings' table. A 'Summary of finding' table provides outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rate as important to patient care and decision making. We selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Global state: recovery, as defined by each study (at end of treatment).

Service use: disengagement from services, as defined by each study (at end of treatment).

Service use: admission to psychiatric hospital (at end of treatment).

Service use: number of days in psychiatric hospital (at end of treatment).

Mental state: clinically important change in general mental state (at end of treatment).

Adverse effects/events: death ‐ all‐cause mortality (at end of treatment).

Functioning: specific ‐ clinically important change in social functioning (at end of treatment).

If data were not available for these prespecified outcomes but were available for ones that are similar, we presented the closest outcome to the prespecified one in the table but took this into account when grading the finding.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia's study‐based register of trials

On 3 October 2018, the Information Specialist searched the register using the search strategy described below. An update of this search strategy was conducted on 22 October 2019.

(*Early Intervention* AND *Special*) in Intervention Field of STUDY

In such study‐based registers, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics (Shokraneh 2017; Shokraneh 2018).

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (AMED, BIOSIS, CENTRAL, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.Gov, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, WHO ICTRP) and their monthly updates, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I and its quarterly update, Chinese databases (CBM, CNKI, and Wanfang) and their annual updates, handsearches, grey literature, and conference proceedings. There are no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register. For the full search strategies used to build Cochrane Schizophrenia's study‐based register of trials, please see: schizophrenia.cochrane.org/register-trials.

Searching other resources

Reference searching

We inspected references of all included studies for further relevant studies.

Personal contact

We contacted known experts in the field for information regarding unpublished trials. We noted the outcome of this contact in the 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of ongoing studies' tables.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors SP and AM independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts; FDC independently re inspected a random 20% sample of the abstracts to ensure reliability of selection. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. SP and AM obtained and inspected full reports of the abstracts or reports meeting the review criteria. FDC re‐inspected a random 20% of these full reports in order to ensure reliability of selection. In case of disagreement, we involved another member of the review team (BL) to reach a final decision. We resolved all disagreements by discussion, and therefore did not need to attempt to contact the authors of the study concerned for clarification.

Data extraction and management

Extraction

Review authors SP, AM, and RH independently extracted data from all included studies. We attempted to extract data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but included the data only if two review authors independently obtained the same result. SP and AM discussed any disagreement and documented our decisions. If necessary, we attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information, or for clarification. AC and BL helped clarify issues regarding any remaining problems and we documented these final decisions.

Management

Forms

We extracted data onto standard, predesigned, simple forms.

Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000);

the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial; and

the instrument should have been a global assessment of an area of functioning and not subscores which are not, in themselves, validated or shown to be reliable.

However there were exceptions; we included subscores from mental state scales measuring positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia where subscales had been previously validated in the empirical literature and were commonly used. Ideally, the measuring instrument should have either been i) a self‐report; or ii) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly; in 'Description of studies' we noted if this was the case or not.

Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data: change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis; however, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint) that can be difficult to obtain in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only used change data if the former were not available (Deeks 2011).

Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to relevant continuous data before inclusion.

Endpoint data from studies with fewer than 200 participants

When a scale started from the finite number zero, we subtracted the lowest possible value from the mean, and divided this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value was lower than one, it strongly suggested that the data are skewed and we excluded these data. If this ratio was higher than one but less than two, there was a suggestion that the data are skewed: we entered these data and tested whether their inclusion or exclusion would change the results substantially. If such data changed the results we entered them as 'other data'. Finally, if the ratio was larger than two we included these data, because it is less likely that they are skewed (Altman 1996).

If a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210 (Kay 1986), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skewed data are present if 2 SD > (S − S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

Please note: we entered all relevant data from studies of more than 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the above rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We also entered all relevant change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether or not data are skewed.

Common measurement

To facilitate comparison between trials we aimed, where relevant, to convert variables that can be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicates a favourable outcome for SEI. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'not unimproved') we reported data where the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome and noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All included studies had two independent 'Risk of bias' assessments. Review authors SP, AM, and RH worked independently to assess risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2011a).

If the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose regarding the category to which a trial is to be allocated, we resolved this by discussion.

We note the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review, Figure 1 and Figure 2, and the 'Risk of bias' tables.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For binary data presented we calculated illustrative comparative risks (Hutton 2009).

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes we attempted to estimate the mean difference (MD) between groups if the measurement scales were the same, otherwise we used standardised mean difference (SMD).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice), but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a unit of analysis error whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated (Divine 1992). This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

Where clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we presented data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We sought to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999).

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data from cluster trials presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation

coefficient (ICC): thus design effect = 1 + (m − 1) * ICC (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported we assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies have been appropriately analysed and taken intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report into account, synthesis with other studies is possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. This occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, participants can differ significantly from their initial state at entry to the second phase, despite a washout phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both carry‐over and unstable conditions are very likely in severe mental illness, we only used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added these and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Where additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce these data.

Dealing with missing data

Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for we would not reproduce these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we addressed this within the 'Summary of findings' table by downgrading certainty. Finally, we also downgraded certainty within the 'Summary of findings' table if the loss was between 25% to 50% in total.

Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT)). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed. We used the rate of those who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ and applied this to those who did not. We undertook sensitivity analyses to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared to the ITT analysis using the above assumptions.

Continuous

Attrition

We used data where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and data only from people who completed the study to that point were reported.

Standard deviations (SDs)

If SDs were not reported, we tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If these were not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exacted standard error (SE) and CIs available for group means, and either P value or t value available for differences in mean, we calculated SDs according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). When only the SE was reported, SDs were calculated by the formula SD = SE * √(n). The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions presents detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2011b). If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which was based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). If studies used different scales to measure the same construct, rather that calculate SDs according to the imputation methods, we followed the rules of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b) and carried the baseline SDs forward to the missing SDs. Although some of these imputation strategies can introduce error, the alternative would have been to exclude a given study's outcome and thus to lose information.

Assumptions about participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up

Various methods are available to account for participants who left the trials early or were lost to follow‐up. Some trials just present the results of study completers; others use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF); while more recently, methods such as multiple imputation or mixed‐effects models for repeated measurements (MMRM) have become more of a standard. While the latter methods seem to be somewhat better than LOCF (Leon 2006), we felt that the high percentage of participants leaving the studies early and differences between groups in their reasons for doing so is often the core problem in randomised schizophrenia trials. We therefore did not exclude studies based on the statistical approach used. However, by preference we used the more sophisticated approaches, i.e. we preferred to use MMRM or multiple imputation to LOCF, and we only presented completer analyses if some kind of ITT data were not available at all. Moreover, we addressed this issue in the item 'Incomplete outcome data' of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies without seeing comparison data to judge clinical heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for participants who were outliers or situations that we had not predicted would arise and, where found, discussed such situations or participant groups.

Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise and discussed any such methodological outliers.

Statistical heterogeneity

Visual inspection

We inspected graphs visually to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

Employing the I² statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I² statistic alongside the Chi² P value. We interpreted an I² estimate greater than or equal to 50% and accompanied by a statistically significant Chi² statistic as evidence of substantial heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). Where substantial levels of heterogeneity were found in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for heterogeneity (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011).

Protocol versus full study

We attempted to locate protocols of included RCTs. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar size.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies, even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. There is, however, a disadvantage to the random‐effects model: it puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose to use a random‐effects model for analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

Standard SEI treatment duration

One of the most vocal arguments for the development of early phase treatments is that there is evidence of a 'critical period' in the early stages of psychosis (Birchwood 1998). This implies that there may be a dose‐response effect for treatment of recent‐onset psychosis (EASY_Extended). The most common duration of SEI treatment given in clinical scenarios is two years, but the duration of treatment given in studies may differ. As a subgroup analysis, where the duration of SEI treatment differed by more than six months from the standard two‐year duration of SEI care, we aimed to include only standard duration SEI trials in a subgroup analysis, however all trials were within six months duration of the standard SEI duration, so we did not perform any subgroup analysis.

Investigation of heterogeneity

We reported if inconsistency was high. Firstly, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Secondly, if data were correct, we inspected the graph visually and removed outlying studies successively to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than 10% of the total weighting, we presented data. If not, we did not pool these data and discussed any issues.

When unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity was obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes only. If there were substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed below, we did not add data from the lower‐quality studies to the results of the higher‐quality trials, but presented these data within a subcategory. If their inclusion did not result in a substantive difference, they remained in the analyses.

Implication of randomisation

If trials were described in some way as to imply randomisation, we aimed to compare data from the implied trials with trials that were randomised. However, all our included trials were randomised and therefore we did not conduct this sensitivity analysis.

Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data) we compared the findings when we used our assumption and where we made the comparison with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

Assumptions for lost continuous data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs (see Dealing with missing data), we aimed to compare the findings when we used our assumption and where we made the comparison with data that were not imputed. If there was a substantial difference, we aimed to report results and discuss them but continued to employ our assumption. However, we did not need to make any assumptions for lost continuous data and therefore did not conduct this sensitivity analysis.

Risk of bias

We aimed to analysed the effects of excluding trials that were at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), however all trials included at least one domain at high risk of bias so we did not conduct this sensitivity analysis.

Imputed values

We aimed to undertake a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster‐randomised trials, but this was not necessary as we did not impute values for ICC in any of the trials.

Fixed‐ and random‐effects

We synthesised data using a random‐effects model; however, we also synthesised data for the primary outcome using a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether this altered the significance of the results.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of the studies please see Included studies, Excluded studies, and Ongoing studies.

Results of the search

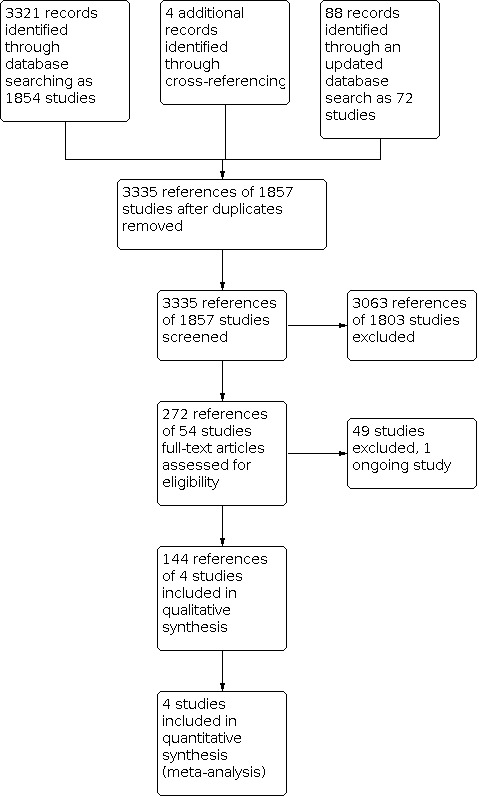

The first electronic search on 3 October 2018 identified 3321 references comprising 1854 studies. The second, updated search on 22 October 2019 identified a further 88 references. We further identified four references but no further studies through a cross‐referencing check of relevant papers. After duplicates were removed, 3335 references remained for screening. We excluded 3063 references through inspection of titles and abstracts, and obtained the full texts for the remaining 272 references, comprising 54 studies, to further assess eligibility. We excluded 49 studies; the reasons for exclusion are described in Excluded studies. One trial with three references is in the Ongoing studies list as the primary outcomes from this study have yet to be published (JCEP 2010). Overall, we included four trials with 144 references in this review. Figure 3 presents the flow chart of the study screening process.

3.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included four studies with a total of 1145 participants.

Design and duration

Three studies were individually‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (LEO; OPUS; OTP), and one was a cluster‐RCT (RAISE). The total treatment duration was 18 months in LEO and 24 months in OPUS, OTP and RAISE.

Participants

Diagnosis

In LEO,participants had to meet the diagnostic criteria for non‐affective psychotic disorders and they had to be presenting to mental health services for the first time, or presenting to services a second time if on the first presentation they disengaged without receiving treatment.

In OPUS, participants had to meet diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and could not have had more than 12 weeks continuous mental health treatment.

In OTP participants had to meet the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform disorders, having only presented to mental health services once (or twice without receiving proper treatment on the first occasion) and having a duration of untreated psychosis of less than 24 months.

In RAISE,participants had to meet diagnostic criteria for non‐affective psychosis, excluding substance induced psychotic disorders. They had to be in their first episode of psychosis with less than six months of lifetime antipsychotic prescriptions.

Age and gender

Age limit criteria were as follows: LEO 16 to 40 years; OPUS 18 to 45 years; OTP 18 to 35 years; RAISE 15 to 40 years. The mean age range in the trials was between 23.1 years (RAISE) and 26.6 years (OPUS). The included participants were 405 females (35.4%) and 740 males (64.6%).

Size

The sample size of the included trials ranged from 50 in OTP to 547 in OPUS, with a total of 1145 participants.

Setting

All four trials took place in community mental health settings in high‐income countries (LEO in England, OPUS in Denmark, OTP in Sweden, and RAISE in the USA).

Interventions

Specialised early intervention (SEI)

LEO was a SEI service with a multidisciplinary team providing an assertive outreach model of care. It provided an extended hours service (including weekend hours), case management with a case manager/service user ratio of 1:15, and offered a low‐dose atypical antipsychotic medication regimen, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), family counselling and vocational strategies, all from manualised protocols.

OPUS was a SEI service with a multidisciplinary team providing an 'enhanced' assertive outreach model of care. The service provided case management for two years, with a caseload ratio of 1:10. The service offered antipsychotic treatment, family psychoeducation, and social skills training.

OTP was a SEI service with a multidisciplinary treatment team. Case management was offered with a caseload ratio of 1:10 and intensive crisis management if needed. In addition, service users were offered low‐dose antipsychotic treatment, structured family psychoeducation, CBT, CBT‐based family communication and problem solving skills training.

RAISE was a standalone SEI service integrated within standard community mental health centres. Treatment was based on four core interventions: medication management, family psychoeducation, resilience‐focused individual therapy, and supported employment and education.

Outcomes

Non‐scale data

We were able to report dichotomous data on recovery, disengagement, leaving the study for any reason, relapse, admission to psychiatric hospital, number of readmissions to psychiatric hospital, number of days in psychiatric hospital, all‐cause mortality, employment, and violent offending.

Recovery was measured in three different ways in the three trials that reported data for the outcome: LEO defined recovery based on two clinicians' independent review of clinical notes over the course of the 18 months. OPUS defined recovery as not being psychotic based on the Life Chart Schedule for the two years prior to the five‐year follow‐up interview. OTP defined recovery through a clinical composite index based on the absence of 1) psychiatric hospital admissions, minor or major psychotic episode and persistent psychotic symptoms (i.e. four or more on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), hallucination or unusual thought content item for six or more consecutive weeks), 2) no suicide attempts, and 3) no poor compliance with treatment, throughout the two‐year follow‐up period.

Disengagement was measured in three different ways in the three trials that reported data for the outcome: LEO defined disengagement as having no contact with any mental health service at the 18‐month follow‐up. OPUS defined disengagement as stopping treatment despite clinical need according to clinical note review. OTP defined disengagement as receiving "little or no treatment" throughout the 24‐month follow‐up period.

We used data for participants leaving the study early for any reason in four trials (LEO; OPUS; OTP; RAISE). Leaving the study early was defined by any drop out from the study for any reason, including loss to follow‐up as reported in the study consort diagram and other supplementary materials. Disengagement relates to leaving treatment from mental health services, while leaving the study for any reason specifically relates to leaving the research study.

Relapse was reported in two studies. LEO defined relapse based on two clinicians' independent review of clinical notes over the course of the18 months of treatment from the SEI service. OTP defined a relapse as either a "major" or a “minor" reoccurrence. We used only major reoccurrence for our data. A major reoccurrence was defined as a two‐point increase in the Target Symptom rating scale and a score of six or seven on one of the key psychotic symptom items on the BPRS scale. In addition, this relapse had to be confirmed by an independent person from the rater (clinical team, or family member) as a significant worsening.

Psychiatric hospital admission was reported in all four trials (LEO; OPUS; OTP; RAISE). Psychiatric hospital admission was collected at multiple time points in LEO and OPUS however, we only used data for time periods measured from randomisation. Results reported in the cluster‐RCT RAISE were adjusted for both site and patient‐level random effects and we synthesised these data using the generic inverse variance technique.

The number of admissions was reported as mean psychiatric hospital admissions from randomisation in two trials (LEO; OTP). The number of psychiatric hospital admission was collected at multiple time points in LEO; however, we only used data for time periods measured from randomisation.

Number of days in psychiatric hospital was reported as mean hospital days per year in three trials (LEO; OPUS; OTP).

Death ‐ through suicide and natural causes was reported in three studies (LEO; OPUS; OTP).

Proportion in employment was measured in two studies (OPUS; RAISE). Results reported in the cluster‐RCT RAISE were adjusted for both site‐ and patient‐level random effects, and we synthesised these data using the generic inverse variance technique.

Violent offending was measured in one study (OPUS). It measured violent offending by the proportion of 'guilty' verdicts for a violent criminal offence during the two‐year and five‐year periods of follow‐up.

Outcome scales providing usable data

We were able to report outcome scale data on general psychopathology, positive psychotic symptoms, negative psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms, general functioning, quality of life and service satisfaction.

Mental state scales

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ‐ PANSS (Kay 1986)

PANSS is a 30‐item scale including three subscales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms, and negative symptoms. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale, with higher scores indicating worse outcome. The Positive and Negative sub scales (with seven questions each) have a range of 7 to 49, whilst the general psychopathology subscale (with 16 questions) has a score range of 16 to 112. Two trials reported outcomes on this scale (LEO; RAISE). Results reported in the cluster‐RCT RAISE were adjusted for both site‐ and patient‐level random effects and we synthesised these data using the generic inverse variance technique.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms ‐ SANS (Andreasen 1984)

The SANS is a valid instrument to assess the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Each item, of which there are 25, is based on six‐point scale, with each domain symptoms rated from 0 (absent) to 5 (severe). Higher scores indicate more symptoms. OPUS reported outcomes on this scale, using the mean of the five global domain scores (range 0 to 5).

Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms ‐ SAPS (Andreasen 2004)

SAPS is a rating scale to measure positive symptoms in schizophrenia. The scale is split into four domains, and within each domain separate symptoms are rated from 0 (absent) to 5 (severe). There are a total of 34 items. OPUS reported outcomes on this scale, using the mean of the four global domain scores (range 0 to 5).

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962)

The BPRS is a 24‐item scale that measures psychiatric symptoms. Each item is marked on a seven‐point Likert scale ranging from one to seven with one being ‘not present’ and seven being ‘extremely severe’. Possible scores range from 24 to 168 with lower scores representing less severe symptoms. Individual questions can be categorised into positive and negative symptoms. OTP reported outcomes on this scale.

Calgary Depression Scale ‐ CDS (Addington 1993)

CDS is a 9‐item scale designed to measure depression in schizophrenia patients without negative symptoms. The possible score ranges from 0 to 27 with higher scores indicating poor depression state. One trial reported outcomes on this scale (LEO).

Social functioning scales

Global Assessment of Functioning ‐ GAF (Jones 1995)

The GAF is a scale to assess psychological, social, and occupational functioning. It is rated on a 100‐point scale with lower scores indicating poorer functioning. Three trials report outcomes on this scale (LEO; OPUS; OTP).

Quality of life scales

Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life ‐ MANSA (Priebe 1999)

MANSA is a self‐report questionnaire that comprises 12 items on a seven‐point rating scale (range from 12 to 84) assessing satisfaction with life ‘in general’, with lower scores representing worse functioning. LEO reported outcomes on this scale; however, items are reversed scored, with lower scores representing better quality of life.

Heinrichs‐Carpenter Quality of Life Scale ‐ QLS (Heinrichs 1984)

The QLS has 21 items rated from semi‐structured interview, with each item rated on a seven‐point scale, for a total range of 0 to 126. Lower scores represent poorer quality of life. RAISE reported outcomes on this scale. Results reported in the cluster‐RCT RAISE were adjusted for both site‐ and patient‐level random effects and we synthesised these data using the generic inverse variance technique.

Service satisfaction scales

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire ‐ CSQ‐8 (De Wilde 2005)

The CSQ‐8 is an eight‐item self‐report of global measure of patient satisfaction with services. The CSQ is substantially correlated with treatment dropout, number of therapy sessions attended, and with change in client‐reported symptoms. The CSQ‐8 consists of eight items rated on a four‐point Likert scale. The items are concerned with quality of services received, how well services met the client’s needs and general satisfaction. The total score ranges from eight to 32. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction of the responders. OPUS reported outcomes on this scale.

Verona service satisfaction scale ‐ VSSS (Ruggeri 1993)

The VSSS is a 32‐item self‐report Likert scale (scored 1 to 5 ) addressing patients’ satisfaction with community‐based psychiatric services. Higher scores represent greater satisfaction. LEO used an eight‐item subscale of the VSSS to determine satisfaction with professionals' skills and behaviour, and reverse‐scored items so that greater satisfaction was represented by lower scores (scored 8 to 40).

Missing outcomes

The following prespecified outcome was not reported: mental state ‐ clinically important change in general mental state.

Excluded studies

We excluded 47 trials from this review. We have summarised them in Characteristics of excluded studies. The most common reasons for exclusion were that studies did not compare a SEI service in 15 (31.9%) studies, that there was no treatment as usual (TAU) condition in 11 (23.4%) studies, and that the intervention was a psychiatric inpatient‐only intervention in six (13.0%) studies.

Ongoing studies

We identified one ongoing trial whose results have not yet been published. Please refer to Ongoing studies for more details.

Awaiting assessment

No studies were awaiting assessment.

Risk of bias in included studies

See also Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

We graded three of the four eligible trials (3/4, 75%) as low risk of bias in relation to sequence generation (LEO; OPUS; OTP). The methods used for sequence generation were either independent or computer‐generated sequencing. We graded RAISE unclear for sequence generation, as it did not describe a method of sequence generation.

Three of the four eligible trials (3/4), 75%) had low risk of bias for allocation concealment (LEO; OPUS; OTP). All three described some form of allocation concealment through either pre‐numbered sealed envelopes or independent central allocation. We graded RAISE unclear for allocation concealment, as it did not describe a method of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Team‐based, long‐term treatment interventions are complex care interventions and would be difficult to mask. Therefore, none of the four trials blinded participants and the treatment team from the treatment arm allocation. We judged that outcome assessment was unlikely to influence results if the primary outcome was an objective outcome (i.e. not a clinical assessment or patient‐reported outcome), or if the primary outcome was subjective (i.e. self‐rated or interviewer‐rated) but those assessing the outcome were blind to the treatment allocation.

We graded all of the four eligible studies as high risk of bias for blinding of the participants. We graded two studies at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessments. In LEO, outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation, however the primary outcome was a subjectively rated outcome made from reading clinical notes of which the outcome assessors were able to guess allocation with 60% accuracy. In OPUS, the primary outcome was an assessor‐rated symptom scale and assessors were not blind to treatment allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

We graded three of the four eligible trials (3/4, 75%) as low risk of bias in relation to incomplete outcome data (LEO; OPUS; OTP). LEO and OTP had a low proportion of incomplete outcome data, while OPUS had 25% missing data at two‐year (end of treatment) follow‐up in the SEI group and 40% missing data in TAU, but accounted for this using appropriate statistics and sensitivity analyses on the missing data. We rated RAISE at high risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data. The authors do not report on the exact figures for missing data but 54% in the intervention group and 68% in the TAU group were considered to have missing data either through exiting the study (34% and 53%, respectively), or completing the study with an assessment gap or gaps by missing more than three consecutive assessments in a row (19% and 13%, respectively). While the authors conducted appropriate analyses to account for missing data, we consider that these data were unlikely to be missing at random. We also consider that the difference in missingness between SEI and TAU would likely lead to bias, and no sensitivity analyses were reported in any published literature to test the assumptions of missingness.

Selective reporting

We considered LEO and RAISE at low risk of bias for selective reporting. Both trials reported prespecified outcomes from a protocol and there is a consistency of reported outcomes in the protocol, primary papers and follow‐up papers. We graded OTP as unknown risk of bias; we were unable to locate a published protocol, and the trial was registered with a trial registry only after the trial was completed. We graded OPUS at high risk of bias for selective reporting; their primary outcome is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not prespecified.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not think there was a high risk of other potential sources of bias within the included trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Specialised early intervention (SEI) compared to treatment as usual (TAU)

Global state: recovery, as defined by the study

End of treatment

Two trials reported end of treatment recovery data. There was a clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups, favouring SEI (risk ratio (RR) 1.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.97; 2 studies, 194 participants; I2 = 18%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 1: Global state: recovery

Medium‐term SEI follow‐up (1 to 60 months post‐treatment)

OPUS reported medium‐term recovery data. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.30; 1 study, 547 participants; Analysis 1.1).

Sensitivity analysis, end of treatment

We found no substantive differences when we used data for completers only in a sensitivity analysis (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.11; 2 studies, 181 participants), or when we used a fixed‐effect model instead of a random‐effects model (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.97; 2 studies, 194 participants; Analysis 1.1).

Service use: disengagement from services, as defined by the study

End of treatment

Three trials reported data on disengagement at the end of treatment. There was a clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups, favouring SEI (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.79; 3 studies, 630 participants; I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 2: Service use: disengagement from services

Sensitivity analysis, end of treatment

We found no differences when we used data for completers only in a sensitivity analysis (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.79; 3 studies, 630 participants), or when we used a fixed‐effect model instead of a random‐effects model in our analysis (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.79; 3 studies, 630 participants; Analysis 1.2).

Service use: admission to psychiatric hospital

End of treatment

Four trials reported end of treatment follow‐up data for admission to psychiatric hospital. The point estimate suggests a difference between SEI and TAU care groups, favouring SEI, but the 95% confidence interval ranged between favouring SEI and no difference (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.00; 4 studies, 1145 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 3: Service use: admission to psychiatric hospital

Long‐term follow‐up (more than 60 months post‐treatment)

OTP reported on long‐term follow‐up data for admission to psychiatric hospital. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.24; 1 study, 50 participants).

Service use: readmission to psychiatric hospital

End of treatment

LEO reported data on this outcome. Data for this outcome were presented as 'other data' because of marked skew (Analysis 1.4), which makes it difficult to interpret the findings.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 4: Service use: readmission to psychiatric hospital ‐ skewed data

| Service use: readmission to psychiatric hospital ‐ skewed data | |||||

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N | Notes |

| end of treatment | |||||

| LEO | SEI | 0.4 | 0.7 | 69 | Reported a difference |

| TAU | 0.8 | 1.0 | 67 | Reported a difference | |

| long term | |||||

| OTP | SEI | 4.4 | 7.9 | 28 | Reported no difference |

| TAU | 6 | 5.7 | 17 | Reported no difference | |

Long‐term follow‐up (more than 60 months post‐treatment)

OTP reported data on this outcome. Data for this outcome were presented as 'other data' because of marked skew (Analysis 1.4), which makes it difficult to interpret the findings.

Service use: number of days in psychiatric hospital

End of treatment

Two trials reported data on this outcome. Data for this outcome from the LEO trial were skewed and we excluded it from the analysis. There was a clear difference between SEI and TAU, favouring SEI (mean difference (MD) ‐27.00, 95% CI ‐53.68 to ‐0.32; 1 study, 547 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 5: Service use: number of days in psychiatric hospital

Medium‐term SEI follow‐up (1 to 60 months post‐treatment)

OTP reported data on this outcome. We excluded data for this outcome from the analysis.

Global state: relapse, as defined by study

End of treatment

Two trials reported end of treatment relapse data. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.08; 2 studies, 194 participants; I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 6: Global state: relapse

Mental state: specific, average endpoint score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale, general psychotic symptoms

End of treatment

Two trials reported data on this outcome. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (standardised mean difference (SMD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐4.58 to 3.75; 2 studies, 304 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 7: Mental state: specific, average endpoint score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale, general psychotic symptoms

Mental state: specific, average endpoint score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale, positive psychotic symptoms

End of treatment

Four trials reported data for average endpoint scores on specific symptom mental state scales. There was a clear difference between SEI and TAU groups, favouring SEI (SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.03; 4 studies, 723 participants; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Specialised early intervention (SEI) versus treatment as usual (TAU, Outcome 8: Mental state: specific, average endpoint score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale, positive psychotic symptoms

Medium‐term SEI follow‐up (1 to 60 months post‐treatment)

OPUS reported medium‐term endpoint score data on positive psychotic symptoms. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (SMD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.29; 1 study, 301 participants).

Long‐term follow‐up (more than 60 months post‐treatment)

OPUS reported long‐term endpoint score data on positive psychotic symptoms. There was no clear difference between SEI and TAU care groups (SMD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.19; 1 study, 547 participants).

Mental state: specific, average endpoint score on specific symptoms mental state scale/subscale, negative psychotic symptoms

End of treatment