Abstract

Background

Shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) is a widely used method to treat renal and ureteral stone. It fragments stones into smaller pieces that are then able to pass spontaneously down the ureter and into the bladder. Alpha‐blockers may assist in promoting the passage of stone fragments, but their effectiveness remains uncertain.

Objectives

To assess the effects of alpha‐blockers as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care compared to placebo and usual care or usual care alone in adults undergoing shock wave lithotripsy for renal or ureteral stones.

Search methods

We performed a comprehensive literature search of the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE, Embase, several clinical trial registries and grey literature for published and unpublished studies irrespective of language. The date of the most recent search was 27 February 2020.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials of adults undergoing SWL. Participants in the intervention group had to have received an alpha‐blocker as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care. For the comparator group, we considered studies in which participants received placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion/exclusion, and performed data abstraction and risk of bias assessment. We conducted meta‐analysis for the identified dichotomous and continuous outcomes using RevManWeb according to Cochrane methods using a random‐effects model. We judged the certainty of evidence on a per outcome basis using GRADE.

Main results

We included 40 studies with 4793 participants randomized to usual care and an alpha‐blocker versus usual care alone. Only four studies were placebo controlled. The mean age of participants was 28.6 to 56.8 years and the mean stone size prior to SWL was 7.1 mm to 13.2 mm. The most widely used alpha‐blocker was tamsulosin; others were silodosin, doxazosin, terazosin and alfuzosin.

Alpha‐blockers may improve clearance of stone fragments after SWL (risk ratio (RR) 1.16, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 1.23; I² = 78%; studies = 36; participants = 4084; low certainty evidence). Based on the stone clearance rate of 69.3% observed in the control arm, an alpha‐blocker may increase stone clearance to 80.4%. This corresponds to 111 more (62 more to 159 more) participants per 1000 clearing their stone fragments.

Alpha‐blockers may reduce the need for auxiliary treatments after SWL (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.00; I² = 16%; studies = 12; participants = 1251; low certainty evidence), but also includes the possibility of no effect. Based on a rate of auxiliary treatments in the usual care arm of 9.7%, alpha‐blockers may reduce the rate to 6.5%. This corresponds 32 fewer (53 fewer to 0 fewer) participants per 1000 undergoing auxiliary treatments.

Alpha‐blockers may reduce major adverse events (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.80; I² = 0%; studies = 7; participants = 747; low certainty evidence). Major adverse events occurred in 25.8% of participants in the usual care group; alpha‐blockers would reduce this to 15.5%. This corresponds to 103 fewer (139 fewer to 52 fewer) major adverse events per 1000 with alpha‐blocker treatment. None of the reported major adverse events appeared drug‐related; most were emergency room visits or rehospitalizations.

Alpha‐blockers may reduce stone clearance time in days (mean difference (MD) –3.74, 95% CI –5.25 to –2.23; I² = 86%; studies = 14; participants = 1790; low certainty evidence). We found no evidence for the outcome of quality of life.

For those outcomes for which we were able to perform subgroup analyses, we found no evidence of interaction with stone location, stone size or type of alpha‐blocker. We were unable to conduct an analysis by lithotripter type. The results were also largely unchanged when the analyses were limited to placebo controlled studies and those in which participants explicitly only received a single SWL session.

Authors' conclusions

Based on low certainty evidence, adjuvant alpha‐blocker therapy following SWL in addition to usual care may result in improved stone clearance, less need for auxiliary treatments, fewer major adverse events and a reduced stone clearance time compared to usual care alone. We did not find evidence for quality of life. The low certainty of evidence means that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Plain language summary

After using shock waves to break up kidney stones, do medicines called alpha‑blockers help to get rid of the stone fragments?

What are kidney stones?

Waste products in the blood can sometimes form crystals that collect inside the kidneys. These can build up over time to form a hard stone‐like lump, called a kidney stone.

Kidney stones can develop in both kidneys especially in people with certain medical conditions or who are taking certain medicines, or if people do not drink enough water or fluids. Stones can cause severe pain, fever and a kidney infection if they block the ureter.

Treatments for kidney stones

Most stones are small enough to pass out in the urine: drinking plenty of water and other fluids will help. Larger kidney stones may be too big to pass out naturally and are usually removed by surgery.

Shock wave lithotripsy is a non‐surgical way to treat stones in the kidney or ureter. High energy sound waves are applied to the outside of the body to break kidney stones into smaller pieces. After shock wave treatment, medicines called alpha‐blockers are sometimes given to help the stone fragments pass out naturally.

Alpha‐blockers work by relaxing muscles and helping to keep blood vessels open. They are usually used to treat high blood pressure and problems with storing and passing urine in men who have an enlarged prostate gland. Alpha‐blockers may relax the muscle in the ureters, which might help to get rid of kidney stones and fragments.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

We wanted to find out how well alpha‐blockers work to help kidney stone fragments pass out in the urine. We also wanted to find out about potential unwanted effects that might be associated with alpha‐blockers.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at giving alpha‐blockers to adults, after shock wave treatment, to clear kidney stone fragments.

We looked for randomized controlled studies, in which the treatments that people received were decided at random, because these studies usually give the most reliable evidence about the effects of a treatment.

Search date: we included evidence published up to 27 February 2020.

What we found

We found 40 studies including 4793 people who had shock wave treatment to break up their kidney stones. Most of the studies were done in Asia; some were in Europe, Africa and South America. Most studies did not report their sources of funding.

The studies compared giving an alpha‐blocker with giving a placebo (dummy) treatment or usual care (could include antibiotics, painkillers and fluids given by mouth or through a drip).

Tamsulosin was the most commonly studied alpha‐blocker; the others were silodosin, doxazosin, terazosin and alfuzosin.

What are the results of our review?

Compared with usual care or a placebo treatment, alpha‐blockers may:

clear kidney stones in more people: in 111 more people for every 1000 people treated (36 studies);

clear stones faster: by nearly four days (14 studies);

reduce the need for extra treatments to clear stones: in 32 fewer people for every 1000 people treated (12 studies); and

cause fewer unwanted effects: affecting 103 fewer people for every 1000 people treated (seven studies).

Most unwanted effects were emergency visits to hospitals, and people going back into hospital for stone related problems. Unwanted effects were more common in people who had usual care or a placebo treatment than in people given alpha‐blockers.

None of the studies looked at people's quality of life (well‐being).

How reliable are these results?

We are uncertain about these results because they were based on studies in which it was unclear how people were chosen to take part; it was unclear if results were reported fully; some results were inconsistent and in some studies the results varied widely. Our results are likely to change if further evidence becomes available.

Conclusions

Giving an alpha‐blocker after shock wave treatment to break up kidney stones might clear the fragments faster, in more people and reduce the need for extra treatments. Alpha‑blockers might cause fewer unwanted effects than usual care or a placebo.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Alpha‐blocker as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care compared to usual care for renal and ureteral stones.

| Alpha‐blocker and usual care compared to usual care for renal and ureteral stones | |||||

| Patient or population: adults with renal and ureteral stones undergoing shock wave lithotripsy Setting: outpatient or inpatient Intervention: alpha‐blocker and usual care Comparison: usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Effect size (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk difference with alpha‐blocker | ||||

|

Stone clearance assessed by imaging Follow‐up range: 1 week to 3 months |

4084 (36 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b,c | RR 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | Moderate risk population | |

| 693 per 1000 | 111 more per 1000 (62 more to 159 more) | ||||

|

Auxiliary treatment Follow‐up range: 1 week to 3 months |

1251 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c,d |

RR 0.67 (0.45 to 1.00) |

Moderate risk population | |

| 97 per 1000 | 32 fewer per 1000 (53 fewer to 0 fewer) |

||||

|

Major adverse events determined by study investigators Follow‐up range: 1 week to 3 months |

747 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | RR 0.60 (0.46 to 0.80) | Moderate risk population | |

| 258 per 1000 | 103 fewer per 1000 (139 fewer to 52 fewer) | ||||

| Low risk populationf | |||||

| 138 per 1000 | 55 fewer per 1000 (139 fewer to 34 fewer) |

||||

| Quality of life | Not reported | ||||

|

Stone clearance time measured in days |

1790 (14 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,g,h | N/A | Moderate risk population | |

| Range: 3.61–47.2 days | 3.74 fewer days (5.25 fewer to 2.23 fewer days) |

||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; N/A: not applicable; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

aDowngraded one level for unclear risk of selection bias, high risk of performance and detection bias, and unclear risk of selective reporting bias. bDowngraded one level due to clinically important, unexplained inconsistency with high I² value. cConcerns over possible publication bias given funnel plot asymmetry contributed to decision to downgraded by two levels overall. dImprecision with wide confidence intervals around absolute effect size estimates that crossed the threshold of 3% clinically relevant absolute risk reduction. eDowngraded two levels for unclear risk of selection bias, high risk of performance and detection bias, and high risk of selective reporting bias for this infrequently reported outcome. fLower, presumably more representative control event rate of 17% obtained by excluding Ahmed 2016. gDowngraded one level given funnel plot asymmetry and serious risk of publication bias. hWe noted a high degree of inconsistency but did not downgrade given its perceived lack of clinical importance.

Background

Description of the condition

Urinary tract stones are the result of a complex cascade of events that involves supersaturation of stone forming salts that precipitate out of solution to form crystals or nuclei. Once formed, these can either flow out and be excreted or they are retained in the kidney where crystals can aggregate and grow to form macroscopic stones that may cause urinary symptoms and obstruction.

Urinary tract stones are a common urologic problem and the worldwide prevalence and incidence is increasing (Chewcharat 2020; Romero 2010). The prevalence has been reported as 16.9% in 1997 in Thailand, 14.8% in 1989 in Turkey and 14% in 2013/2014 in England (Romero 2010; Rukin 2017). In the USA, the prevalence of stone disease has been estimated at 10.6% in men and 7.1% in women in the 2007–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Scales 2012). Proposed modifiable risk factors include maintaining a normal body mass index, drinking an adequate fluids, and eating fruits and vegetables (Ferraro 2017). The cost of this disease is high, with estimates upwards of several billion dollars in 2000 in the USA (Saigal 2005). There are variable costs associated with urinary tract stones based on acute, medical or surgical management options (Canvasser 2017).

Diagnosis

People presenting with clinical suspicion for symptomatic urinary tract stones are evaluated with history and physical exam, followed by imaging studies. The primary imaging modality used depends on the availability of the tools. In an older study of people presenting to an emergency room with a stone, 90% had acute unilateral flank pain, hematuria, and positive imaging by kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) radiograph (Elton 1993). The European Association of Urology (EAU) now recommends ultrasound as the initial diagnostic imaging tool in people suspected of urinary tract stones due to its safety profile and low cost (Turk 2016). However, imaging beyond ultrasound may be needed to best characterize the stone and its location. Non‐contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (NCCT) is the gold standard diagnostic tool for nephrolithiasis in any location of the urinary tract. It characterizes stone density and determines precise location including defining skin‐to‐stone distance – factors important in determining the best treatment modality (El‐Nahas 2007; Kim 2007; Zarse 2007). NCCT has largely replaced intravenous urography in diagnosing acute urinary tract stones due to its higher diagnostic accuracy (Worster 2002). It also represents the most accurate treatment modality to establish treatment success but has the downside of costs and radiation exposure.

Treatment

Urinary tract stones may pass on their own or require intervention to assist with expulsion. The likelihood of spontaneous passage depends on the size and location of the stone. Smaller stones located more distally in the urinary tract, notably the distal ureter and beyond, have the highest rates of spontaneous passage (Hubner 1993). Segments of the ureter are defined radiographically: proximal from its origin to the upper border of the sacroiliac joint; middle overlying the SI joint; and distal from the lower border of the sacroiliac joint and beyond. Ureteral stones less than 10 mm have the highest incidence of spontaneous expulsion, and the American Urological Association (AUA) recommends observation with trial of passage in people whose pain is well controlled and are free of signs of infection or high grade obstruction (Assimos 2016a; Assimos 2016b). Furthermore, for uncomplicated ureteral colic due to ureteral stones of the distal ureter, these guidelines recommend medical expulsive therapy (MET) with alpha‐blockers (alpha‐adrenoreceptor antagonists) (Assimos 2016a; Assimos 2016b). A panel using GRADE and following the British Medical Journal (BMJ) Rapid Recommendations procedure recommend MET, even in settings when stone size and location has not been established by imaging studies (Vermandere 2018). Supporting evidence for the use of MET as primary treatment for ureteral stones comes from several high‐quality reviews (Campschroer 2018; Hollingsworth 2016). It should be noted that MET is an off‐label indication for alpha‐blockers and their actual value for this indication remains controversial given concerns over the quality of the underlying trials as well as their adverse effects and costs (De Coninck 2019; Pickard 2015). In addition, people with a more complicated presentation, for example those with signs of a systemic infection, as witnessed by fever or an elevated white blood cell count (or both), should undergo immediate urinary drainage by ureteral stent or percutaneous nephrostomy placement.

Renal colic is a likely symptom of acute stone episodes and must be treated accordingly. Pain management is part of the usual treatment regimen for symptomatic stones. The EAU and AUA recommend non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including metamizole to treat renal colic (Assimos 2016a; Assimos 2016b; Turk 2016). Definitive stone treatment may be offered to patients if spontaneous stone passage is not achieved or sooner intervention is clinically necessary. The typical timeframe for a trial of spontaneous passage ranges from four to six weeks. People with pain uncontrolled with oral analgesics, worsening renal function or sepsis from the urinary tract require surgical management, either definitive management with stone removal or urinary drainage (in the setting of signs of sepsis) (Assimos 2016a; Assimos 2016b; Turk 2016). Two commonly used options for definitive management are ureteroscopy (URS) and shock wave lithotripsy (SWL). An advantage of URS is the greater stone free rate, which has been shown even when stones less than 10 mm are stratified by location in the ureter (Preminger 2007). The higher stone free rate after a single procedure is particularly notable for distal ureteral stones, and thus URS typically is recommended over SWL. Advantages of SWL over URS are decreased complication rates and lower morbidity (Aboumarzouk 2012). The complications of urinary tract infections (UTI), ureteral strictures and ureteral avulsion are similar between SWL and URS, but URS has a higher risk of ureteral perforation (Aboumarzouk 2012). Additional options for definitive treatment of stones include percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), laparoscopic, open surgical removal or robotic surgical removal.

SWL is a non‐invasive procedure where high energy shock waves are applied to the outside of the body to break up urinary tract stones in the kidney and ureter. The tiny stone fragments can then pass through the urinary system to be excreted. To aid in patient comfort, SWL may be performed under mild sedation, or local or general anesthesia. Fluoroscopy or ultrasound (or both) are used for imaging studies throughout the procedure to localize the stones and monitor treatment progression (Kohrmann 1995). The technique of SWL encompasses several factors to optimize treatment outcomes (Matlaga 2016). Modifiable SWL parameters include the number of shocks, period of shock wave administration, voltage, type of shock wave generator and rate of shock wave delivery. A large skin‐to‐stone distance negatively impact stone fragmentation (Pareek 2005). In addition, focal zones differ considerably by lithotripter type, manufacturer and model, and can greatly impact stone fragmentation effectiveness. Of note, current evidence based guidelines only recommend SWL in people with normal anatomy of the collecting system, normal renal function and the absence of infection. Given its unknown effect on the fetus (especially given the common use of fluoroscopy), SWL is contraindicated in pregnant women (Assimos 2016a; Assimos 2016b; Turk 2016; Turk 2020).

Further possible complications from SWL of renal or ureteral stones are related to incomplete stone fragmentation and renal colic symptoms when fragments cause distention and obstruction of the ureter (Skolarikos 2006). The term steinstrasse refers to when multiple stone fragments or debris line the ureter (Sayed 2001). Steinstrasse occurs in 1% to 4% of SWL cases (Madbouly 2002). This complication can lead to clinically significant obstruction, pain and infection (Sayed 2001). Trauma to the kidneys causes bleeding in the urinary tract when SWL is performed. The shock waves cause small vessels in the kidney to rupture which can lead to hematoma formation (Matlaga 2016).

Description of the intervention

Alpha‐blockers work by relaxing smooth muscle and help keep small blood vessels open. Examples of alpha‐blockers include tamsulosin, alfuzosin, terazosin, naftopidil and silodosin. They are typically used to treat or improve symptoms of high blood pressure and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and are particularly helpful if a person has both conditions. Because there is a lack of evidence supporting the cardioprotective effects of alpha‐blockers compared to placebo, alpha‐blockers are no longer recommended as first‐line treatment for high blood pressure (Pool 2005). Alpha‐blockers have been shown to improve lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), the complex of symptoms associated with BPH (Shapiro 1992). The rationale for the use of alpha‐blockers is that LUTS are at least partly due to bladder outlet obstruction, a process mediated by alpha1 adrenoreceptors in prostatic smooth muscle (Caine 1976).

Alpha‐blockers are available as an adjuvant medical therapy to enhance stone fragment passage after SWL. If fragments do not readily pass after SWL, patients can develop complications including steinstrasse. Urinary tract obstruction, infection and significant pain can develop from incomplete stone passage. The use of SWL as treatment for stones may result in need for repeat or additional procedures to clear all stone fragments. Therefore, we are interested in the use of alpha‐blockers to facilitate stone passage after SWL. Like MET for improvement of spontaneous stone passage, MET after SWL is an off‐label use of the medication in the USA (Campschroer 2018).

Adverse effects of the intervention

The most frequent adverse effects of alpha‐blockers are related to the cardiovascular system. The American Geriatrics Society 2015 recommends avoidance of the alpha‐blockers doxazosin, prazosin and terazosin as antihypertensive medications in elderly people due to the high risk of orthostatic hypotension. Because of the risk of orthostatic hypotension, as well as bradycardia, avoidance of use in people with history of syncope is also recommended (Boehringer 2019). Alpha‐blockers may exacerbate heart failure. Tamsulosin has been reported to cause atrial fibrillation in postmarketing studies (Boehringer 2019). Additionally, those studies have reported adverse effects of palpitations, peripheral edema, tachycardia and cardiac dysrhythmia.

Adverse effects of terazosin on the genitourinary tract have been reported. Erectile dysfunction has been known to occur in 1.2% to 1.6% of men (Abbott Laboratories 2019). Priapism – prolonged and painful erection of the penis – has been reported, but only rarely (Abbott Laboratories 2019). Abnormal ejaculation has been reported with alpha‐blocker use. In men taking tamsulosin, the incidence of abnormal ejaculation is between 8.4% and 18.1% (Boehringer 2019). The abnormal ejaculation was reversible in 76% of men upon discontinuation of the drug (Hofner 1999). Decreased ejaculate volume has been reported in 89.6% of men taking tamsulosin, and anejaculation, the lack of any ejaculation, has been reported in 35.4% of men taking tamsulosin (Hellstrom 2006). Furthermore, alpha‐blockers may worsen incontinence in women with stress or mixed urinary incontinence (Kiruluta 1981; Thien 1978).

How the intervention might work

The rationale for the use of alpha‐blockers as an adjuvant medical therapy for stones is based on the natural history of stones causing contraction of the ureters during passage that may inhibit expulsion. Contractility of the ureters is mediated by alpha‐ and beta‐adrenoreceptors located in the ureteral walls (Park 2007). The ureters contains alpha1D‐ and alpha1A‐adrenoreceptor subtypes and the less prevalent alpha1B‐adrenoreceptor subtype (Itoh 2007; Karabacak 2013; Sigala 2005). The distal ureter contains the highest density of alpha1‐adrenoreceptors, as observed based on the ability of the distal ureter to generate a higher contractile force compared to the proximal ureter (Sasaki 2011).

Adrenergic transmission is mediated by the chemical norepinephrine, which is synthesized within neurons. Norepinephrine activates alpha‐adrenoreceptors and causes stimulation of ureteral activity (Hernández 1992; McLeod 1973). Stimulation of alpha‐adrenoreceptors has been shown to increase contraction of ureteral smooth muscle and promote more frequent peristalsis (Park 2007; Sasaki 2011). Therefore, blockade of alpha‐adrenoreceptors with alpha‐blockers leads to decrease in ureteral contractions (Rose 1974). The decrease in ureteral spasm by alpha‐blockers has the potential benefit of easing spontaneous passage of stones by increasing the rate of expulsion and decreasing pain (Crowley 1990; Laird 1997). It is the alpha‐blockers that have selectivity for alpha1A‐adrenoreceptor subtype, namely alfuzosin, doxazosin, prazosin, tamsulosin, terazosin and silodosin, that have primarily been used for MET.

Pharmacological agents that facilitate ureteral relaxation have the potential to aid in stone expulsion (Sivula 1967). Medications with alpha‐blocking activity help to relax ureteral smooth muscle and could aid in stone passage. Other agents that mediate ureteral relaxation through mechanisms other than alpha‐adrenoreceptors (for example, calcium channel blockers) have been explored in enhancing stone passage, but are outside the scope of this review (Gupta 2014; Pickard 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Whereas several trials have been conducted to assess the effect of alpha‐blockers in people undergoing SWL for urinary tract stones, there is no consensus as to its effects. Underlying issues relate to clinical differences between trials, such as the type of lithotripter and the definition used for successful stone fragmentation as well as varying methodological quality of these trials. These issues mirror those in the use of alpha‐blockers in people with ureteral colic which were addressed in one Cochrane Review (Campschroer 2018). Campschroer 2018 and another high‐quality review (Hollingsworth 2016) have suggested a possible subgroup effect based on stone size with greater effectiveness in larger stones (5 mm and greater). This appear relevant to our review given that SWL stone fragments can be expected to be smaller (3 mm or less) in size, thereby drawing into question the effectiveness of MET in this setting. Our review will, therefore, address the specific clinical scenario of alpha‐blocker use after SWL. Adjuvant treatment to SWL may provide important benefits for people with residual fragments after SWL. There is potential to accelerate stone passage, thereby leading to less analgesic use, faster recovery and less time away from work. Adjuvant treatment may also reduce costly and invasive secondary treatments. Alpha‐blockers are particularly appealing for MET due to their reported favorable adverse effect profile and low cost. We expect this review to provide important guidance for individual patients, clinicians, guideline developers and policy makers by rigorously assessing the magnitude of both potential desirable and undesirable effects and our confidence in these estimates of effect.

Existing systematic reviews on the use of MET after SWL to date have not applied the same methodological rigor as a Cochrane Review (Lee 2012; Li 2015; Losek 2008; Schuler 2009; Seitz 2009; Skolarikos 2015; Yang 2017; Zheng 2010), where we focus on patient‐centered outcomes by applying the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008). Our review is structured to address an ongoing knowledge gap on the effectiveness of MET after SWL in clinical practice.

Objectives

To assess the effects of alpha‐blockers as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care compared to placebo and usual care or usual care alone in adults undergoing shock wave lithotripsy for renal or ureteral stones.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel group randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We included studies regardless of their publication status or language of publication. We considered that cross‐over trials were unsuitable for this review; also, cluster randomized controlled trials were also not relevant to this review question and therefore not considered. We excluded non‐RCTs and trials using pseudo‐randomization techniques as they are at greater risk of bias.

Types of participants

We included studies of men and non‐pregnant women (ages 18 years or older) of either gender who had undergone SWL for renal and ureteral stones. We included trials irrespective of the lithotripter type used, the number of shock waves applied and the number of sessions performed. We included only studies that use imaging to confirm stone diagnosis. The imaging modality may have been a single test – for example, NCCT – or a combination of tests such as KUB radiograph and ultrasound.

We excluded studies on MET for the primary expulsion of stones. We also excluded studies of people with renal insufficiency (defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 ml/minute/1.73 m²), obstructive uropathy or UTI, as these represent contraindications for SWL.

If we identified studies in which only a subset of participants was relevant to this review, we included such studies if data were available separately for the relevant subset.

Types of interventions

We investigated the following comparisons of experimental intervention versus comparator intervention. Concomitant interventions had to be the same in the experimental and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Experimental interventions

Alpha‐blockers as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care.

Comparator interventions

Placebo and usual care, or usual care alone.

Comparisons

Alpha‐blockers as adjuvant medical expulsive therapy plus usual care versus placebo and usual care, or usual care alone.

For the purpose of this review, usual care in the context of SWL for kidney and ureteral stones may have been used in the alpha‐blocker treatment group if the same care was also used in the control group. Usual care may have included oral or intravenous hydration, NSAIDs, pain medication and antibiotics as deemed clinically appropriate. We excluded studies that included antispasmodics, corticosteroids or herbal supplements in the usual care regimens as these could potentially alter the treatment effect; this approach was consistent with that of high‐quality reviews on MET (Hollingsworth 2016). We recognized that this determination may have limited the applicability of our review findings with regard to practice settings in which these adjuvants are commonly used and limit further exploratory analyses as to their role. However, the main objectives of this study were the effects of alpha‐blockers, and inclusion of these adjuvants pose the risk of adding both noise (random error) and bias to the planned analysis.

We anticipated potential variation in the intraoperative management of anesthetic, sedation, pain and antibiotics for people undergoing SWL, but did not consider those factors relevant unless they differed between treatment and control groups.

Types of outcome measures

We did not use the measurement of the outcomes assessed in this review as an eligibility criterion.

Primary outcomes

Stone clearance (dichotomous outcome).

Auxiliary treatment (dichotomous outcome).

Major adverse events (dichotomous outcome).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (continuous outcome).

Stone clearance time (continuous outcome).

Method and timing of outcome measurement

When reviewing outcomes, we considered clinically important differences by predefined thresholds to rate the overall quality of evidence in the 'Summary of findings' table (Jaeschke 1989; Johnston 2013). In the absence of published minimal clinically important differences, we established thresholds with input from our content experts.

Stone clearance

Participants with documented passage of all stones from the kidney and ureter of a given size criterion based on imaging (e.g. KUB radiograph, NCCT) as defined by the investigators.

We assessed this outcome up to 90 days after SWL.

We considered a 5% absolute difference in stone clearance as clinically important.

Auxiliary treatment

Participants requiring unplanned, additional treatments such as URS or stent placement due to failure of stones to pass or to treat secondary complications such ureteral colic or hydronephrosis. We did not consider additional SWL sessions as auxiliary treatment for this analysis.

We assessed this outcome up to 30 days after SWL.

We considered a 3% absolute difference in retreatment rates as clinically important.

Major adverse event

Example: syncope or hypotension requiring hospitalization or unplanned emergency room visit.

We used the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) definition of serious adverse events (FDA 2018).

We assessed this outcome up to 90 days after SWL.

We considered a 1% absolute difference in major adverse events rates as clinically important.

Quality of life

Mean change from baseline or final mean value measured using a validated scale. For example, the RAND 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) (Ware 1992).

We assessed this outcome up to 90 days after SWL.

We considered a clinically important mean difference (MD) of points on quality of life scores based on the specific scale used.

Stone clearance time

Length of time from onset of treatment to stone clearance (in participants who pass their stone) as measured in days.

We considered an MD of one day as clinically important.

Main outcomes for 'Summary of findings' table

We presented a 'Summary of findings' table that reports on the following outcomes (listed according to priority).

Stone clearance

Auxiliary treatment

Major adverse event

Quality of life

Stone clearance time

Search methods for identification of studies

We performed a comprehensive search with no restrictions on the language of publication or publication status. We reran searches within three months prior to anticipated publication of the review; the latest search date was 27 February 2020.

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database (Appendix 1).

-

Cochrane Library via Wiley:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE);

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA).

MEDLINE via PubMed (from 1946).

Embase via Elsevier (from 1974).

We also searched the following.

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

Grey literature repository from the current Grey Literature Report (www.greylit.org).

If detected additional relevant key words during any of the electronic or other searches, we modified the electronic search strategies to incorporate these terms and document the changes.

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports. We also contacted study authors of included trials to identify any further studies that we may have missed. We contacted drug/device manufacturers for ongoing or unpublished trials. We did not search abstract proceedings of relevant meetings, specifically those of the AUA, the EAU and the Endourological Society for the last three years (2017 to 2019; no meetings in 2020) separately for unpublished studies since the abstract proceedings for these meetings were included in our electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used the reference management software EndNote to identify and remove potential duplicate records. Two review authors (MO, RV or NS) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of remaining records retrieved, to determine which studies should be assessed further using Covidence software. Two review authors (MO, RV or NS) independently investigated all potentially relevant records as full text, mapped records to studies, and classified studies as included studies, excluded studies, studies awaiting classification, or ongoing studies in accordance with the criteria for each provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We resolved any discrepancies through consensus or recourse to a third review author (PD). If resolution was not possible, we designated the study as 'awaiting classification' and we contacted study authors for clarification. We documented reasons for exclusion of studies that may have reasonably been expected to be included in the review in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We presented an adapted PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of study selection (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We developed a dedicated data abstraction form that we pilot tested.

For studies that fulfilled inclusion criteria, two review authors (MO, RV or NS) independently abstracted the following information, which we provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design.

Study dates (if dates were not available then we reported as such).

Study settings and country.

Type of lithotripter device used and target size for stone fragments.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e. stone size, stone location).

Participant details, baseline demographics (i.e. participant age, stone size, stone location, laterality).

Procedure details (i.e. mean number of shock waves administered, number of session).

Number of participants by study and study arm.

Details of relevant experimental and comparator interventions (i.e. type of alpha‐blocker, dosage, duration of treatment in weeks).

Definitions of relevant outcomes, and method and timing of outcome measurement as well as any relevant subgroups.

Imaging modality used to assess stone clearance (i.e. KUB radiograph, ultrasound, NCCT).

Study funding sources.

Declarations of interest by primary investigators.

We extracted outcome data relevant to this Cochrane Review as needed for calculation of summary statistics and measures of variance. For dichotomous outcomes, we attempted to obtain numbers of events and totals for population of a 2 × 2 table, as well as summary statistics with corresponding measures of variance. For continuous outcomes, we attempted to obtain means and standard deviations or data necessary to calculate this information.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (PD).

We provided information, including trial identifier, about potentially relevant ongoing studies in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

We attempted to contact authors of included studies to obtain key missing data as needed.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary study, we maximized yield of information by mapping all publications to unique studies and collating all available data. We collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We used the most complete data set aggregated across all known publications. In case of doubt, we gave priority to the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (MO, RV, NS) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We resolved disagreements by consensus, or by consultation with a third review author (PD).

We assessed risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2017). We assessed the following domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other sources of bias.

We judged risk of bias domains as 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We presented a 'Risk of bias' summary figure to illustrate these findings.

For performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), we considered all outcomes similarly susceptible to performance bias.

For detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), we grouped outcomes as susceptible to detection bias (investigator or participant assessed) or not susceptible to detection bias (objective).

We defined the following endpoints as investigator assessed outcomes.

Stone clearance.

Major adverse events.

Stone clearance time.

We defined the following endpoint as a participant assessed outcome.

Quality of life.

We defined the following endpoint as an objective outcome.

Auxiliary treatments.

We assessed attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) on an outcome specific basis and presented the judgment for each outcome separately when reporting our findings in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

We further summarized the risk of bias across domains for each outcome in each included study, as well as across studies and domains for each outcome, in accordance with the approach for summary assessments of the risk of bias presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017).

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We expressed continuous data as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs unless studies use different measures to assess the same outcome, in which case we expressed data as standardized mean differences with 95% CIs. We expressed time‐to‐event data as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant and we accounted for the level at which randomization occurred. If we identified trials with more than two intervention groups for inclusion in the review, we handled these in accordance with guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Dealing with missing data

We obtained missing data from study authors, if feasible, and performed intention to treat (ITT) analyses if data were available; we otherwise performed available case analyses but identified the analysis as such. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals), and critically appraised issues of missing data. We did not impute missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of excessive heterogeneity unexplained by subgroup analyses, we did not report outcome results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis but provided a narrative description of the results of each study.

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) through visual inspection of the forest plots to assess the amount of overlap of CIs, and the I² statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003); we interpreted the I² statistic as follows (Deeks 2017).

0% to 40%: may not be important.

30% to 60%: may indicate moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may indicate substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

When we found heterogeneity, we attempted to determine possible reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to obtain study protocols to assess for selective outcome reporting.

If we included 10 studies or more investigating a particular outcome, we used funnel plots to assess small study effects. Several explanations can be offered for the asymmetry of a funnel plot, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials) and publication bias. Therefore, we interpreted results carefully.

Data synthesis

Unless there was good evidence for homogeneous effects across studies, we summarized data using a random‐effects model. We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects. In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines contained in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). For dichotomous outcomes, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method and for continuous outcomes, we used the inverse variance method. We used Review Manager 5 software to perform analyses (Review Manager 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity and planned to carry out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions.

Stone location (renal or proximal ureter versus distal ureter).

Stone size (less than 10 mm versus 10 mm or greater).

Specific alpha‐blocker (e.g. terazosin versus doxazosin).

Type of lithotripter (HM3 versus others)

The subgroup analyses by stone location, size and type of alpha‐blocker were based on observations of potential subgroup effects demonstrated in previous studies for the use of MET for ureteral colic (Campschroer 2018; Hollingsworth 2016; Preminger 2007). The subgroup analysis based on type of lithotripter was based on the fact that different shock wave lithotripter devices vary in their effectiveness in stone fragmentation with the HM3 lithotripter (as first generation lithotripter with the largest acoustic energy focal zone) being the most powerful in achieving stone fragmentation (McClain 2013).

In addition, we performed post hoc analyses that were suggested by one of the peer reviewers and were based on a different categorization of stone location. The underlying rationale was that the targeted alpha‐1 receptors are primarily found in the ureteral (not renal pelvis), predominantly in its distal part Campschroer 2018; Hollingsworth 2016, therefore raising the possibility of a reduced effect in renal stones.

Stone location (renal or ureter).

We used the test for subgroup differences in Review Manager 5 to compare subgroup analyses if there were sufficient studies (Review Manager 2014). We limited subgroup analyses to primary outcomes only.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses, limited to the primary outcomes, in order to explore the influence of the following factors (when applicable) on effect sizes.

Restricting the analysis by considering risk of bias, by excluding studies at 'high risk' or 'unclear risk'.

Limiting the analysis to studies with a documented single SWL session and studies with multiple SWL sessions that reported outcomes separately by the number of sessions (thereby allowing us to focus on the results of a single session only).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We present the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach, which takes into account five criteria related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), and external validity, such as directness of results (Guyatt 2008). GRADE has good interobserver agreement when used by trained individuals (Mustafa 2013). For each comparison, two review authors (MO, RV or NS) independently rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome as 'high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low' using GRADEpro GDT. We resolved any discrepancies by consensus or, if needed, by arbitration by a third review author (PD). For each comparison, we presented a summary of the evidence for the main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table, which provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies; numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome; and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome (Guyatt 2011; Schünemann 2017). If meta‐analysis had not been possible, we would have presented the results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table. We applied a partially conceptualized approach defining a minimally clinically important difference that was based on the published literature or the input of clinical expertise of the coauthors, or both (Hultcrantz 2017). We used GRADE guidance to describe both the certainty of evidence and the magnitude of the effect size (Santesso 2020).

Results

Description of studies

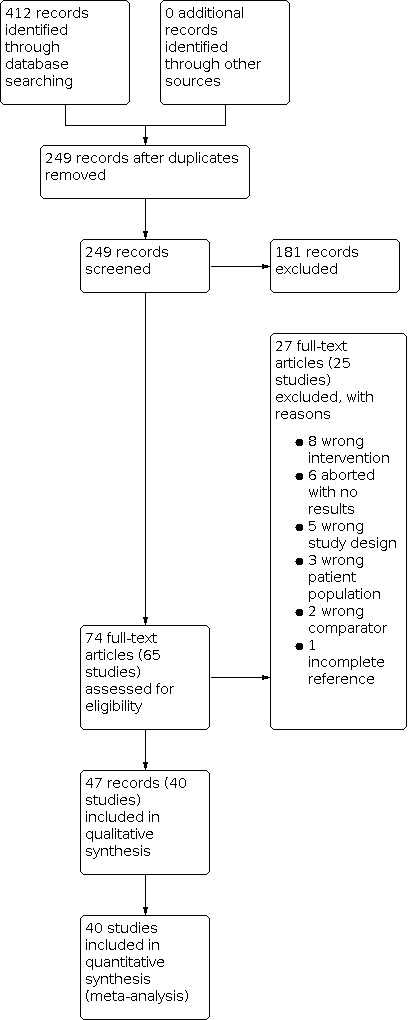

Our comprehensive literature search identified 412 records. We found no applicable records in trials registers or the grey literature repository.

Results of the search

After duplicates were removed, we screened the titles and abstracts of 249 records, and excluded 181 records. We screened 74 full text records (65 studies) and excluded 27 records (25 studies) for the reasons given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We included 47 records (40 studies) in the systematic review. There were no ongoing studies that met inclusion criteria. The details of the literature search are shown in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We presented details of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table, Table 2, and Table 3.

1. Baseline characteristics.

| Study name | Trial period (year to year) | Setting/country | Description of participants | Duration of follow‐up | SWL description (lithotripter; number shocks; power setting) | Number SWL sessions | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Stone location (n) | Largest stone size (mm, mean ± SD) |

| Agarwal 2009 | 2006–2007 | Single center/India | Single upper ureteric stone < 15 mm in size | 3 months | Electromagnetic lithotripter Lithostar Multiline; max 3500 shocks; 14.4–15.1 kV | Max 4 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | 9.4 ± 1.9 |

| Usual care (NSAIDs, antispasmodics, or tramadol PRN) | 10.4 ± 3 | ||||||||

| Ahmed 2016 | 2013–2016 | Multicenter/Saudi Arabia | Solitary renal stone < 20 mm | 12 weeks | Electromagnetic lithotripter Dornier SII; max 3500 shocks; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Renal | 12.06 ± 3.82 |

| Usual care (diclofenac potassium 50 mg BID for 2 days, additional doses PRN; drink plenty of fluids) | 12.56 ± 3.97 | ||||||||

| Ateş 2012 | 2009–2010 | Multicenter/Turkey | Renal colic and upper ureteral stones | 2 weeks | Siemens Lithoscope; max 3000 shocks; NR | Max 2 | Doxazosin 4 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | 9.06 ± 1.45 |

| Usual care (diclofenac sodium PRN; drink fluid to provide urine output ≥ 2 L/day) | 8.3 ± 2.51 | ||||||||

| Baloch 2011 | 2010 | NR/Pakistan | Renal calculi | Max 3 months | NR | 1 | Alfuzosin 10 mg + usual care | Renal | NR |

| Usual care (standard analgesia PRN) | |||||||||

| Bhagat 2007 | 2004–2005 | NR/India | Single radiopaque renal 6–24 mm or ureteral 6–15 mm calculus | 30 days | Dornier Compact S Lithotripter; 1,500 shocks; 14–15 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 14 calyx/6 pelvis/5 upper renal/4 lower ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (proxyvon [65 mg dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride and 400 mg acetaminophen] daily PRN; minimum 2.5 L fluids) | 12 calyx/9 pelvis/6 upper renal/2 lower ureteral | ||||||||

| Cakıroglu 2013 | 2008–2011 | Multicenter/Turkey | Solitary 6–15 mm ureteral stone | 4 weeks | Storz Medical AG Modulith Slk; 2700–3600 shocks; 6–19 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | NR | 11.4 ± 3.01 |

| Usual care (diclofenac 75 mg IM PRN, pantoprazole 40 mg/day, after discharge drink 2 L water daily) | 10.7 ± 3.2 | ||||||||

| Chau 2015 | NR | NR/China | Renal stones undergoing ESWL up to 3 times | 4 weeks | NR | Max 3 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Renal | NR |

| Usual care (analgesic not further defined) | |||||||||

| Cho 2013 | 2010–2011 | Single center/South Korea | Participants with radio‐opaque ureter stones 5–10 mm in diameter | Max 42 days | Comed Lithotripsy SDS‐5000; NR; NR | Max 2 | Alfuzosin 10 mg + usual care | 35 upper ureteral/6 lower ureteral | 7.1 ± 1.7 |

| Usual care (loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg PRN; 2 L fluids daily) | 37 upper ureteral/6 lower ureteral | 7.2 ± 1.8 | |||||||

| De Nunzio 2016 | 2012–2015 | Presumed single center/Italy | Single radiopaque renal stone (0.5–2 cm) | 3 weeks | EDAP integrated Sonolith 4000 plus; max 3500 shocks; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 2 upper renal/7 mid‐renal/5 lower renal/5 pelvis | 10.28 ± 2.46 |

| Usual care not further defined | 5 upper renal/6 mid‐renal/2 lower renal/9 pelvis | 9.23 ± 2.04 | |||||||

| Silodosin 8 mg/day + usual care | 2 upper renal/4 mid‐renal/9 lower renal/4 pelvis | 10.45 ± 1.73 | |||||||

| Elkoushy 2012 | NR | Presumed single center/Egypt | Single radio‐opaque renal or upper ureteral stones ≤ 2 cm in largest diameter | 3 months or until stone free | Electromagnetic Siemens Lithostar; max 4000 shocks; 14–15 kV | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 35 renal (5 upper calyx/3 mid‐calyx/12 lower calyx/15 pelvis)/28 upper ureteral | 12.3 ± 1.8 renal, 9.7 ± 2.6 ureteral |

| Usual care (sodium diclofenac 50 mg oral or 75 mg IM PRN) | 42 renal (4 upper calyx/6 mid‐calyx/14 lower calyx/18 pelvis)/21 upper ureteral | 11.5 ± 2.3 renal, 8.6 ± 1.7 ureteral | |||||||

| Eryildirim 2016 | 2015 | Presumed single center/Turkey | 5 to 10 mm single radio‐opaque upper ureteral stones (above iliac vessels) | 4 weeks | Electromagnetic lithotriptor Compact Sigma; max 4000 shocks; 14–15 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (diclofenac sodium, enteric‐coated tablets 75 mg PRN) | |||||||||

| Falahatkar 2011 | 2008–2009 | Single center/Iran | Renal or ureteral stone 4–20 mm | 12 weeks | Storz lithotriptor; NR; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 69 renal/9 ureteral | 13.22 ± NR |

| Usual care (ofluxacine 200 mg per 12 hours for 5 days; minimum 2 L fluid daily) | 61 renal/14 ureteral | 12.88 ± NR | |||||||

| Gaafar 2011 | NR | NR/Egypt | Solitary renal pelvic calculi who were successfully fragmented by ESWL | 12 weeks | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Renal | NR |

| Usual care (diclofenac sodium 75 mg PRN) | |||||||||

| Doxazocin daily for up to 12 weeks + usual care | |||||||||

| H 2012 | NR | NR/China | 5–20 mm ureteric stone in any position | 4 weeks | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | NR | NR |

| Usual care (analgesic not further specified 1 week PRN) | |||||||||

| Hammoud 2014 | 2010–2012 | Single center/Egypt | Males with solitary, radio‐opaque upper urinary tract stones, ≤ 20 mm in the max diameter | 2 weeks after last SWL session | NR | Max 3 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 35 renal/12 upper ureteral | 13 ± 4.96 |

| Usual care (drink liberal fluids, analgesic not further specified PRN) | 33 renal/10 upper ureteral | 12.3 ± 4.82 | |||||||

| Han 2006 | 2005–2006 | Single center/South Korea | Upper ureteral stone 6–12 mm | 2 weeks | Piezolith‐3000; 3000 shocks; 15 kV | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (drink 2 L fluid daily) | |||||||||

| Hong 2012 | NR | Single center/Singapore | Upper ureteric or renal stones | 12 weeks | NR | 1 | Alfuzosin XL 10 mg + usual care | 11 renal/8 upper ureteral | NR |

| Usual care only (not further described) | 14 renal/7 upper ureteral | ||||||||

| Itaya 2011 | NR | NR/Japan | Males with ureteral stones | 28 days | NR | 1 | Silodosin 0.8 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (pain relieving therapy) | |||||||||

| Janane 2014 | 2008–2012 | Presumed single center/Morocco | Lower ureteral stones undergoing ESWL | 3 months | Storz MODULITH SLX‐F2; NR; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 30 upper calyx/23 mid‐calyx/79 pelvis/54 lumbar ureteral | 9.2 ± 2.8 |

| Usual care (diclofenac 25 mg TID; minimum 2 L water daily) | 26 upper calyx/19 mid‐calyx/75 pelvis/50 lumbar ureteral | 9.4 ± 3 | |||||||

| Kang 2009 | 2007 | Multicenter/South Korea | ≥ 4 mm ureteral stone with acute pain | 1 week | Compact Delta II, E‐3000, Sonolith Praktis; NR; NR | multiple | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and diclofenac 100 mg + usual care | 18 renal/50 upper ureteral/47 lower ureteral | NR |

| Usual care only | 19 renal/34 upper ureteral/39 lower ureteral | ||||||||

| Kim 2008 | 2006–2007 | Single center/South Korea | ≤ 10 mm upper and lower ureteral stone | NR | Sonolith Praktis; 2500–3000 shocks; 10–18 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and pethidine 50 mg IV (once during SWL) + usual care | 18 upper ureteral/24 lower ureteral | NR |

| Education for hydration and exercise + usual care | 21 upper ureteral/13 lower ureteral | ||||||||

| Kobayashi 2008 | 2005–2006 | Multicenter/Japan | Males with ureteral stones > 4 mm | Until stone clearance | Dornier lithotripter, Stoltz SLX‐MX, Simens modularis variostar; NR; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg + usual care | 27 proximal ureteral/3 mid‐ureteral/8 distal ureteral | 10.61 ± 4.45 |

| Usual care (diclofenac 50 mg suppository PRN; 2 L water per day) | 23 proximal ureteral/3 mid‐ureteral/8 distal ureteral | 9.85 ± 3.13 | |||||||

| Küpeli 2004 | 2003–2004 | NR/Turkey | Lower ureteral stones within the distal 5 cm of the ureter 3–15 mm in size | 15 days | Siemens Lithostar Plus; 2000–3500 shocks; 18.7 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | NR | 8.6 ± NR |

| Usual care (diclofenac sodium 100 mg/day for 15 days; oral hydration) | 8.6 ± NR | ||||||||

| Lanchon 2017 | 2015 | Single center/France | Participants with urinary stone | 1 month | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin or silodosin + usual care | 44 renal/24 ureteral | 8.4 ± NR |

| Usual care (analgesic PRN) | 31 renal/26 ureteral | 8.2 ± NR | |||||||

| Liu 2009 | NR | NR/China | Single ureteral stone | 2 weeks | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg + usual care | NR | NR |

| Usual care (hydration, antibiotics, acetaminophen PRN) | |||||||||

| Micali 2007 | 2003–2005 | NR/Italy | Radiopaque or radiolucent ureteral lithiasis | 60 days | Dornier Lithotripter S; NR; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg; ketoprofene 50 mg BID for 7 days + usual care | Lower ureteral | 10 ± 2.59 |

| Usual care (diclofenac 75 mg IM PRN; 1.5–2 L water daily) | 9.9 ± 1.37 | ||||||||

| Mohamed 2013 | 2010–2012 | Single center/Egypt | Solitary ureteric stone 5–15 mm diameter | 90 days | Electromagnetic lithotripter Dornier SII; max 3000–4000 shocks; 12–15 kV | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 25 upper ureteral/14 mid‐ureteral/26 lower ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (furosemide 20 mg every morning; diclofenac sodium 50 mg TID or a 75 mg ampoule PRN; oral fluids) | 31 upper ureteral/13 mid‐ureteral/21 lower ureteral | ||||||||

| Naja 2008 | 2006–2007 | NR/India | Single radiopaque renal stone (5–20 mm) undergoing ESWL | 12 weeks | Electromagnetic lithotripter Siemens Lithostar‐Multiline; max 3500 shocks; 13.4–15.1 kV | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 38 renal pelvis/9 superior calyx/4 middle calyx | 12.12 ± 3.59 |

| Usual care (NSAIDs, antispasmodics or tramadol PRN) | 52 renal pelvis/7 superior calyx/6 middle calyx | 13.06 ± 3.49 | |||||||

| Park 2013 | 2011–2013 | NR/Korea | Ages 18–70 years with symptomatic, unilateral and single proximal ureteral stones 6–20 mm in the longest axis | 3 weeks | Sonolith Praktis electroconductive lithotripter EDAP TMS S.A.; NR; NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg + usual care | Proximal ureteral | 9.2 ± NR |

| Usual care (aceclofenac 100 mg PRN; 1.5–2 L water daily) | 9.6 ± NR | ||||||||

| Qadri 2014 | 2010 | Single center/Pakistan | Single radio‐opaque renal stone (0.5–2.0 cm) | 8 weeks | Electromagnetic shock wave generator Storz Medical Modulith SLK; max 4000 shocks; max 70 kV | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 36 pelvis/17 lower renal/5 mid‐renal/2 upper renal | 11.2 ± 3.1 |

| Usual care (diclofenac sodium 50 mg BID for 1 day) | 43 pelvis/13 lower renal/3 mid‐renal/1 upper renal | 10.5 ± 2.6 | |||||||

| Rakesh 2015 | NR | NR/India | Inclusion criteria for ESWL | NR | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin (dose NR) + usual care | NR | NR |

| Usual care (not further defined) | |||||||||

| Seungok 2009 | NR | NR/NR | Ureteral stones < 10 mm treated with ESWL | NR | NR | Multiple | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg + usual care | NR | NR |

| Usual care (not further defined) | |||||||||

| Shaikh 2018 | 2013 | Single center/Pakistan | Ages > 18 to < 50 years, single radio‐opaque and size < 20 mm | 8 weeks | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Renal | 10.4 ± 2.59 |

| Usual care (diclofenac 50 mg BID) | 10.61 ± 3.01 | ||||||||

| Sighinolfi 2010 | 2009 to NR | NR/Italy | Apparent ESWL‐fragmentation of renal stones | NR | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin (dose NR) + usual care | Renal | 9.8 ± 4.2 |

| Usual care (not further defined) | 9.1 ± 2.6 | ||||||||

| Singh 2011a | 2006–2008 | Single center/India | Ages ≥ 18 years with symptomatic, unilateral, solitary lower ureteric calculus 4–12 mm in major axis | 4 weeks | Electromagnetic lithotripter HK–ESWL–VI; max 3000 shocks; 12–15 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Lower ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (antibiotics and diclofenac PRN during the study period; 2500 mL fluid daily) | |||||||||

| Singh 2011b | 2006–2008 | Single center/India | Ages 18–70 years with symptomatic, unilateral and solitary upper ureteral calculi 6–15 mm in major axis | 3 months | Electromagnetic lithotripter HK–ESWL–VI; max 3000 shocks; 12–15 kV | Max 3 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Upper ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (diclofenac PRN during the study period; 2500 mL fluid daily) | |||||||||

| Tajari 2009 | 2006–2007 | Single center/Iran | 7–19 mm stone diameter | 3 months | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Ureteral | NR |

| Usual care (diclofenac 100 mg suppositories daily; diclofenac 25 mg) orally | |||||||||

| Terazosin 2 mg + usual care | |||||||||

| Teleb 2015 | 2012–2014 | NR/Egypt | Participants who underwent successful SWL (fragments < 4 mm) for single renal stone ≤ 2 cm | 4 weeks | NR | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Renal | NR |

| Usual care (analgesic and anti‐inflammatory) | |||||||||

| Vicentini 2011 | 2006–2009 | Single center/Brazil | Ages > 18 years, radio‐opaque non‐lower pole renal stone (5–20 mm) and ESWL | 30 days | Electromagnetic lithotripter Dornier Compact Delta Lithotriptor; 4000 shocks; 11–14 kV | 1 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | 11 superior calyx/13 mid‐calyx/14 pelvis | NR |

| Usual care (celecoxib 200 mg BID PRN; 3 L liquid daily) | 7 superior calyx/16 mid‐calyx/15 pelvis | ||||||||

| Wang 2008 | 2005–2007 | NR/China | Lower ureteral stones | 2 weeks | NR | NR | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg + usual care | Lower ureteral | 8.6 ± 2.6 |

| Usual care (not further defined) | 8.2 ± 3.1 |

BID: twice daily; ESWL: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy; IM: intramuscular; IV: intravenous; max: maximum; n: number; NR: not reported; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PRN: on demand; SD: standard deviation; SWL: shock wave lithotripsy; TID: three times daily.

2. Participants in included studies and imaging modality used to assess stone clearance.

| Study name | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Screened/eligible (n) | Randomized (n) | Analyzed (n) | Finishing trial (n [%]) | Follow‐up imaging modality |

| Agarwal 2009 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | 55/NR | 20 | 20 | 20 (100) | KUB |

| NSAIDs, antispasmodics or tramadol PRN | 20 | 20 | 20 (100) | |||

| Total | 40 | 40 | 40 (100) | |||

| Ahmed 2016 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | 326/279 | 135 | 123 | 123 (91.1) | KUB, ultrasound and CT |

| Diclofenac potassium 50 mg BID for 2 days, additional doses PRN; drink plenty of fluids | 136 | 126 | 126 (92.6) | |||

| Total | 271 | 249 | 249 (91.9) | |||

| Ateş 2012 | Doxazosin 4 mg | NR/NR | NR | 35 | 35 (NR) | KUB |

| Diclofenac sodium PRN; drink fluid to provide urine output ≥ 2 L/day | NR | 44 | 44 (NR) | |||

| Total | 90 | 79 | 79 (87.7) | |||

| Baloch 2011 | Alfuzosin 10 mg | NR/NR | 65 | 65 | 65 | NR |

| Standard analgesia on demand | 65 | 65 | 65 | |||

| Total | 130 | 130 | 130 (100) | |||

| Bhagat 2007 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 30 | 29 | 29 | KUB |

| Proxyvon (dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride 65 mg and acetaminophen 400 mg ) daily PRN; minimum 2.5 L fluids | 30 | 29 | 29 | |||

| Total | 60 | 58 | 58 (96.7) | |||

| Cakıroglu 2013 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | NR | 59 | 59 | KUB and ultrasound |

| Diclofenac 75 mg IM on demand, pantoprazole 40 mg/day, after discharge drink 2 L water daily | NR | 64 | 64 | |||

| Total | NR | 123 | 123 (NR) | |||

| Chau 2015 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 88 | 88 | 88 | NR |

| Analgesic | 95 | 95 | 95 | |||

| Total | 183 | 183 | 183 (100) | |||

| Cho 2013 | Alfuzosin 10 mg | NR/NR | 45 | 41 | 41 (91.1) | KUB |

| Loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg PRN; 2 L fluids daily | 45 | 43 | 43 (95.6) | |||

| Total | 90 | 84 | 84 (93.3) | |||

| De Nunzio 2016 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | NR | 19 | 19 | Ultrasound and CT |

| No alpha‐blocker | NR | 22 | 22 | |||

| Silodosin 8 mg/day for 21 days | NR | 19 | 19 | |||

| Total | 66 | 60 | 60 (90.1) | |||

| Elkoushy 2012 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 63 | 63 | 63 | KUB and ultrasound |

| Sodium diclofenac 50 mg oral or 75 mg IM PRN | 63 | 63 | 63 | |||

| Total | 126 | 126 | 126 (100) | |||

| Eryildirim 2016 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 40 | 28 | 28 (70) | NR |

| Diclofenac sodium, enteric‐coated tablets 75 mg PRN | 40 | 26 | 26 (65) | |||

| Total | 80 | 54 | 54 (67.5) | |||

| Falahatkar 2011 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 75 | 70 | 70 (93.3) | KUB and ultrasound |

| Ofluxacine 200 mg per 12 hours for 5 days; minimum 2 L fluid daily | 75 | 71 | 71 (94.7) | |||

| Total | 150 | 141 | 141 (94) | |||

| Gaafar 2011 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 50 | NR | NR | NR |

| Diclofenac sodium 75 mg PRN | 50 | NR | NR | |||

| Doxazocin daily for up to 12 weeks | 50 | NR | NR | |||

| Total | 150 | NR | NR | |||

| H 2012 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | NR | 8 | NR | NR |

| Analgesic 1 week PRN | NR | 12 | NR | |||

| Total | NR | 20 | NR | |||

| Hammoud 2014 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 47 | 47 | 47 | NR |

| Drink liberal fluids, analgesic PRN | 49 | 49 | 49 | |||

| Total | 96 | 96 | 96 (100) | |||

| Han 2006 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg | NR/45 | 22 | 22 | 22 | KUB and IVP |

| Drink 2 L fluid daily | 23 | 23 | 23 | |||

| Total | 45 | 45 | 45 (100) | |||

| Hong 2012 | Alfuzosin XL 10 mg | NR/NR | 19 | 19 | NR | NR |

| No alpha‐blocker | 21 | 21 | NR | |||

| Total | 40 | 40 | NR | |||

| Itaya 2011 | Silodosin 0.8 mg | NR/NR | 16 | 16 | NR | NR |

| Pain relieving therapy | 16 | 16 | NR | |||

| Total | 32 | 32 | NR | |||

| Janane 2014 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 186 | 186 | NR | KUB, ultrasound and CT |

| Diclofenac 25 mg TID; minimum 2 L water daily | 170 | 170 | NR | |||

| Total | 356 | 356 | NR | |||

| Kang 2009 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and diclofenac 100 mg | NR/247 | 115 | 115 | 115 | NR |

| No alpha‐blocker | 92 | 92 | 92 | |||

| Total | 207 | 207 | 207 (100) | |||

| Kim 2008 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and pethidine 50 mg IV (once during SWL) | NR/76 | 42 | 42 | 42 | KUB, IVP or CT |

| Education for hydration and exercise | 34 | 34 | 34 | |||

| Total | 76 | 76 | 76 (100) | |||

| Kobayashi 2008 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg | NR/NR | 38 | 38 | 38 | KUB and ultrasound |

| Diclofenac 50 mg suppository PRN; 2 L water per day | 34 | 34 | 34 | |||

| Total | 72 | 72 | 72 (100) | |||

| Küpeli 2004 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/97 | 24 | 24 | 24 | KUB and CT |

| Diclofenac sodium 100 mg/day for 15 days; oral hydration | 24 | 24 | 24 | |||

| Total | 48 | 48 | 48 (100) | |||

| Lanchon 2017 | Tamsulosin or silodosin | NR/NR | 68 | 68 | NR | NR |

| Analgesic PRN | 57 | 57 | NR | |||

| Total | 125 | 125 | NR | |||

| Liu 2009 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg | NR/NR | 53 | 53 | NR | NR |

| Conservative therapy PRN, e.g. hydration, antibiotics, acetaminophen | 55 | 55 | NR | |||

| Total | 108 | 108 | NR | |||

| Micali 2007 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg; ketoprofene 50 mg BID for 7 days | NR/NR | 28 | 28 | 28 | KUB, ultrasound and CT |

| Diclofenac 75 mg IM PRN; 1.5–2 L water daily | 21 | 21 | 21 | |||

| Total | 49 | 49 | 49 (100) | |||

| Mohamed 2013 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | 156/156 | 65 | 65 | 65 | KUB and ultrasound |

| Furosemide 20 mg every morning; diclofenac sodium 50 mg TID or a 75 mg ampoule PRN; oral fluids | 65 | 65 | 65 | |||

| Total | 130 | 130 | 130 | |||

| Naja 2008 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 67 | 51 | 51 (76.1) | KUB and ultrasound |

| NSAIDs, antispasmodics or tramadol PRN | 72 | 65 | 65 (90.3) | |||

| Total | 139 | 116 | 116 (83.5) | |||

| Park 2013 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg | NR/NR | 48 | 44 | 44 (91.7) | KUB and ultrasound |

| Aceclofenac 100 mg PRN; 1.5–2 L water daily | 48 | 44 | 44 (91.7) | |||

| Total | 96 | 88 | 88 (91.7) | |||

| Qadri 2014 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 60 | 60 | 60 | KUB |

| Diclofenac sodium 50 mg BID for 1 day | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||

| Total | 120 | 120 | 120 (100) | |||

| Rakesh 2015 | Tamsulosin (dose NR) | NR/NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| No alpha‐blocker | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Total | 120 | 120 | NR | |||

| Seungok 2009 | Tamsulosin 0.2 mg | NR/NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| No alpha‐blocker | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Total | 55 | 55 | NR | |||

| Shaikh 2018 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 80 | 80 | 80 | NR |

| Diclofenac 50 mg BID | 80 | 80 | 80 | |||

| Total | 160 | 160 | 160 (100) | |||

| Sighinolfi 2010 | Tamsulosin (dose NR) | NR/NR | 60 | 60 | NR | NR |

| No alpha‐blocker | 69 | 69 | NR | |||

| Total | 129 | 129 | NR | |||

| Singh 2011a | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 60 | 60 | 60 (100) | KUB and ultrasound |

| Antibiotics and diclofenac PRN during the study period; 2500 mL fluid daily | 60 | 59 | 59 (98.3) | |||

| Total | 120 | 119 | 119 (99.2) | |||

| Singh 2011b | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | NR | 59 | 59 (NR) | KUB and ultrasound |

| Diclofenac PRN during the study period; 2500 mL fluid daily | NR | 58 | 58 (NR) | |||

| Total | 120 | 117 | 117 (97.5) | |||

| Tajari 2009 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 80 | 80 | NR | NR |

| Diclofenac 100 mg suppositories daily; diclofenac 25 mg orally | 80 | 80 | NR | |||

| Terazosin 2 mg | 80 | 80 | NR | |||

| Total | 240 | 240 | NR | |||

| Teleb 2015 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 106 | 106 | NR | NR |

| Analgesic and anti‐inflammatory | 106 | 106 | NR | |||

| Total | 212 | 212 | NR | |||

| Vicentini 2011 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 45 | 38 | 38 (84.4) | KUB and ultrasound |

| Celecoxib 200 mg BID PRN; 3 L liquid daily | 46 | 38 | 38 (82.6) | |||

| Total | 91 | 76 | 76 (83.5) | |||

| Wang 2008 | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | NR/NR | 40 | 40 | 40 | NR |

| Control group | 40 | 40 | 40 | |||

| Total | 80 | 80 | 80 (100) | |||

BID: twice daily; CT: computer tomography; IM: intramuscular; IV: intravenous; IVP: intravenous pyelography; KUB: kidney, ureter, bladder radiograph; n: number; NR: not reported; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PRN: on demand; SWL: shock wave lithotripsy; TID: three times daily.

Source of data

We included 26 studies published in full text and 14 as abstract proceedings (Baloch 2011; Chau 2015; Gaafar 2011; H 2012; Hammoud 2014; Hong 2012; Itaya 2011; Lanchon 2017; Liu 2009; Rakesh 2015; Seungok 2009; Sighinolfi 2010; Tajari 2009; Teleb 2015). Most studies were published in English; three were in Korean (Han 2006; Kang 2009; Kim 2008), and one in Chinese (Wang 2008). The Korean studies were translated by a review author (ECH) and we used Google translator for the Chinese study. We attempted to contact all corresponding authors of included trials to obtain additional information on study methodology and results and received replies from only a few. Details of this communication are provided in the notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design and settings

We included all parallel RCTs. Only four studies were described as 'double blind' (Bhagat 2007; Elkoushy 2012; Falahatkar 2011; Vicentini 2011). One study was reported as single blind, but it was unclear who was blinded (Cho 2013). It was unclear if blinding was performed in five studies (De Nunzio 2016; Hammoud 2014; Janane 2014; Kang 2009; Wang 2008). The remaining 30 studies were open label.

Studies were performed in both inpatient and outpatient centers. Four studies were in the hospital setting (Ateş 2012; Cakıroglu 2013; Hong 2012; Kobayashi 2008). Eight studies were in an outpatient setting (Cho 2013; Han 2006; Kang 2009; Kim 2008; Mohamed 2013; Park 2013; Singh 2011a; Singh 2011b). Two studies reported they were performed specifically in an SWL center (Falahatkar 2011; Tajari 2009). Most studies were performed in Asia (China, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Turkey), but also in Africa (Egypt and Morocco), Europe (France and Italy) and South America (Brazil). Four trials were multicenter (Ahmed 2016; Ateş 2012; Kang 2009; Kobayashi 2008). The studies were performed from 2003 to 2015.

Participants

We included 4793 randomized participants, of whom 3087 completed the trials. However, six studies did not clearly report the number randomized to each group (Ateş 2012; De Nunzio 2016; H 2012; Rakesh 2015; Seungok 2009; Singh 2011b), and 12 studies did not clearly report the number completing the trial in each group (Gaafar 2011; H 2012; Hong 2012; Itaya 2011; Janane 2014; Lanchon 2017; Liu 2009; Rakesh 2015; Seungok 2009; Sighinolfi 2010; Tajari 2009; Teleb 2015). The mean age of participants was 28.6 years to 56.8 years. Twelve studies did not report participants' age (Baloch 2011; Chau 2015; Gaafar 2011; H 2012; Hong 2012; Itaya 2011; Lanchon 2017; Liu 2009; Rakesh 2015; Seungok 2009; Sighinolfi 2010; Teleb 2015). As reported in Table 2, studies used a variety of lithotripters but no study used the Dornier HM3 device (thereby precluding one of our predefined subgroup analyses).

The mean size of stones prior to SWL was 7.1 mm to 13.2 mm. Twelve studies did not report stone size (Baloch 2011; Chau 2015; Gaafar 2011; H 2012; Hong 2012; Itaya 2011; Lanchon 2017; Liu 2009; Rakesh 2015; Seungok 2009; Sighinolfi 2010; Teleb 2015). The stone location for 12 studies was ureteral (Cakıroglu 2013; Cho 2013; H 2012; Itaya 2011; Kang 2009; Kim 2008; Kobayashi 2008; Liu 2009; Micali 2007; Mohamed 2013; Seungok 2009; Tajari 2009). In 11 it was renal (Ahmed 2016; Baloch 2011; Chau 2015; De Nunzio 2016; Gaafar 2011; Naja 2008; Qadri 2014; Shaikh 2018; Sighinolfi 2010; Teleb 2015; Vicentini 2011). Six studies specified only upper ureteral stones (Agarwal 2009; Ateş 2012; Eryildirim 2016; Han 2006; Park 2013; Singh 2011b). Four studies included only lower ureteral stones (Janane 2014; Küpeli 2004; Singh 2011a; Wang 2008). Three studies included renal and ureteral stones (Bhagat 2007; Falahatkar 2011; Lanchon 2017). An additional three studies included renal and upper ureteral stones (Elkoushy 2012; Hammoud 2014; Hong 2012). One study did not report on stone location (Rakesh 2015).

Interventions, comparators and comparisons

Twenty‐seven of 40 studies used tamsulosin. The dosage of tamsulosin was typically 0.4 mg daily, but seven studies used 0.2 mg daily (Han 2006; Kang 2009; Kim 2008; Kobayashi 2008; Liu 2009; Park 2013; Seungok 2009). Two studies did not report the dosage (Rakesh 2015; Sighinolfi 2010). Three studies compared tamsulosin directly to another alpha‐blocker: to silodosin (De Nunzio 2016), doxazosin (Gaafar 2011), and terazosin (Tajari 2009). One study used either tamsulosin or silodosin (Lanchon 2017). Three studies used alfuzosin (Baloch 2011; Cho 2013; Hong 2012). One study used doxazosin (Ateş 2012) and one used silodosin (Itaya 2011).