Abstract

Background

Adjuvant tamoxifen reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence in women with oestrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer. Tamoxifen also increases the risk of postmenopausal bleeding, endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer. The levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) causes profound endometrial suppression. This systematic review considered the evidence that the LNG‐IUS prevents the development of endometrial pathology in women taking tamoxifen as adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) in pre‐ and postmenopausal women taking adjuvant tamoxifen following breast cancer for the outcomes of endometrial and uterine pathology including abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, and secondary breast cancer events.

Search methods

We searched the following databases on 29 June 2020; The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group specialised register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. We searched the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group specialised register on 4 March 2020. We also searched two trials registers, checked references for relevant trials and contacted study authors and experts in the field to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen that compared the effectiveness of the LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance versus endometrial surveillance alone on the incidence of endometrial pathology.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. The primary outcome measure was endometrial pathology (including polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, or endometrial cancer), diagnosed at hysteroscopy or endometrial biopsy. Secondary outcome measures included fibroids, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, breast cancer recurrence, and breast cancer‐related deaths. We rated the overall certainty of evidence using GRADE methods.

Main results

We included four RCTs (543 women analysed) in this review. We judged the certainty of the evidence to be moderate for all of the outcomes, due to imprecision (i.e. limited sample sizes and low event rates). In the included studies, the active treatment arm was the 20 μg/day LNG‐IUS plus endometrial surveillance; the control arm was endometrial surveillance alone.

In tamoxifen users, the LNG‐IUS probably reduces the incidence of endometrial polyps compared to the control group over both a 12‐month period (Peto odds ratio (OR) 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.08 to 0.64, I² = 0%; 2 RCTs, n = 212; moderate‐certainty evidence) and over a long‐term follow‐up period (24 to 60 months) (Peto OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.39; I² = 0%; 4 RCTs, n = 417; moderate‐certainty evidence). For long‐term follow‐up, this suggests that if the incidence of endometrial polyps following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 23.5%, the incidence following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 3.8% and 10.7%.

The LNG‐IUS probably slightly reduces the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia compared with controls over a long‐term follow‐up period (24 to 60 months) (Peto OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.67; I² = 0%; 4 RCTs, n = 417; moderate‐certainty evidence). This suggests that if the chance of endometrial hyperplasia following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 2.8%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 0.1% and 1.9%. However, it should be noted that there were only six cases of endometrial hyperplasia.

There was insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion regarding the incidence of endometrial cancer in tamoxifen users, as no studies reported cases of endometrial cancer.

At 12 months of follow‐up, the LNG‐IUS probably increases abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting compared to the control group (Peto OR 7.26, 95% CI 3.37 to 15.66; I² = 0%; 3 RCTs, n = 376; moderate‐certainty evidence). This suggests that if the chance of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 1.7%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 5.6% and 21.5%. By 24 months of follow‐up, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting occurs less frequently than at 12 months of follow‐up, but is still more common in the LNG‐IUS group than the control group (Peto OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.04 to 7.10; I² = 0%; 2 RCTs, n = 233; moderate‐certainty evidence). This suggests that if the chance of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 4.2%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 4.4% and 23.9%. By 60 months of follow‐up, there were no cases of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting in either group.

The numbers of events for the following outcomes were low: fibroids (n = 13), breast cancer recurrence (n = 18), and breast cancer‐related deaths (n = 16). As a result, there is probably little or no difference in these outcomes between the LNG‐IUS treatment group and the control group.

Authors' conclusions

The LNG‐IUS probably slightly reduces the incidence of benign endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia in women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen. At 12 and 24 months of follow‐up, the LNG‐IUS probably increases abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting among women in the treatment group compared to those in the control. Data were lacking on whether the LNG‐IUS prevents endometrial cancer in these women. There is no clear evidence from the available RCTs that the LNG‐IUS affects the risk of breast cancer recurrence or breast cancer‐related deaths. Larger studies are necessary to assess the effects of the LNG‐IUS on the incidence of endometrial cancer, and to determine whether the LNG‐IUS might have an impact on the risk of secondary breast cancer events.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Adenocarcinoma; Adenocarcinoma/chemically induced; Adenocarcinoma/prevention & control; Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal; Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal/adverse effects; Breast Neoplasms; Breast Neoplasms/chemistry; Breast Neoplasms/mortality; Breast Neoplasms/prevention & control; Chemotherapy, Adjuvant; Confidence Intervals; Contraceptive Agents, Female; Contraceptive Agents, Female/administration & dosage; Endometrial Hyperplasia; Endometrial Hyperplasia/chemically induced; Endometrial Hyperplasia/epidemiology; Endometrial Hyperplasia/prevention & control; Endometrial Neoplasms; Endometrial Neoplasms/chemically induced; Endometrial Neoplasms/epidemiology; Endometrial Neoplasms/prevention & control; Intrauterine Devices, Medicated; Levonorgestrel; Levonorgestrel/administration & dosage; Levonorgestrel/adverse effects; Neoplasm Recurrence, Local; Neoplasm Recurrence, Local/mortality; Neoplasm Recurrence, Local/prevention & control; Polyps; Polyps/chemically induced; Polyps/epidemiology; Polyps/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tamoxifen; Tamoxifen/adverse effects; Uterine Hemorrhage; Uterine Hemorrhage/chemically induced; Uterine Hemorrhage/epidemiology; Uterus; Uterus/drug effects

Plain language summary

Levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen to prevent recurrence

Review question

Cochrane authors investigated whether the levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) can reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, abnormal thickening of the lining of the uterus and endometrial cancer in women taking tamoxifen following breast cancer. The review also investigated whether use of the LNG‐IUS influences the risk of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, fibroids, breast cancer recurrence or death in women taking tamoxifen following breast cancer.

Background

Tamoxifen is commonly used by women to reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Tamoxifen can also cause abnormal changes to the lining of the uterus (endometrium), including polyps and cancer. The LNG‐IUS is a uterine device that releases the synthetic hormone levonorgestrel into the endometrium and causes marked endometrial suppression. As levonorgestrel is a progestin, and many breast cancers are progesterone‐sensitive, it is important to study the safety of the LNG‐IUS in breast cancer survivors.

Study characteristics

We included four randomised controlled trials involving 543 women. The studies took place in the UK, Turkey, Egypt and Hong Kong, and the primary outcome in all studies was abnormal changes in the lining of the uterus. Three studies reported on the outcome of fibroids. Three studies reported on abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting. Two studies reported on breast cancer recurrence, and three studies reported on breast cancer‐related death. The evidence is current to June 2020.

Key results

This review suggests that the LNG‐IUS probably slightly reduces the risk of endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia over two to five years in women taking tamoxifen following breast cancer. The evidence suggests that if the incidence of endometrial polyps following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 23.5%, the incidence following LNG‐IUS plus endometrial surveillance would be between 3.8% and 10.7%. Evidence also suggests that if 2.8% of women who only had endometrial surveillance developed endometrial hyperplasia, the chance following LNG‐IUS plus endometrial surveillance would be between 0.1% and 1.9%.

The LNG‐IUS probably increases abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting. After one year, the evidence suggests that if the incidence of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 1.7%, the incidence following LNG‐IUS plus endometrial surveillance would be between 5.6% and 21.5%. After two years, if 4.2% of women who only had endometrial surveillance experienced abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, between 4.4% and 23.9% of women who had both surveillance and LNG‐IUS would be expected to experience this. However by five years of follow‐up, no women in either group reported abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting.

We found insufficient evidence to reach a conclusion regarding the effect on incidence of endometrial cancer (a cancer originating in glandular tissue), fibroids, breast cancer recurrence, or breast cancer‐related death.

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the certainty of the evidence to be moderate because the studies only included a limited number of women and there were not many events. Larger studies are necessary to assess the effects of the LNG‐IUS on the incidence of endometrial cancer, and the impact of the LNG‐IUS on the risk of secondary breast cancer events.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. The LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance compared to endometrial surveillance alone for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen.

| The LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance compared to endometrial surveillance alone for endometrial protection in women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen | |||||||

| Patient or population: women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen Setting: hospital, outpatient clinic Intervention: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance Comparison: endometrial surveillance alone | |||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrated comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | ||

| Assumed Risk | Corresponding Risk | ||||||

| Endometrial surveillance alone | LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance | ||||||

| Endometrial polyps follow‐up: range 24 months to 60 months | 235 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 (38 to 107) | OR 0.22 (0.13 to 0.39) | 417 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Endometrial hyperplasia follow‐up: range 24 months to 60 months | 28 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (1 to 19) | OR 0.13 (0.03 to 0.67) | 417 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Endometrial cancer follow‐up: range 24 months to 60 months | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 154 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Fibroids follow‐up: range 12 months to 24 months | 58 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (10 to 82) | OR 0.48 (0.16 to 1.46) | 314 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | follow‐up: 12 months | 17 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (56 to 215) | OR 7.26 (3.37 to 15.66) | 376 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — |

| follow‐up: 24 months | 42 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (44 to 239) | OR 2.72 (1.04 to 7.10) | 233 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| follow‐up: 60 months | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | not estimable | 94 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Breast cancer recurrence follow‐up: range 24 months to 60 months | 80 per 1000 | 131 per 1000 (53 to 291) | OR 1.74 (0.64 to 4.74) | 154 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| Breast cancer‐related death follow‐up: range 12 months to 60 months | 69 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (26 to 174) | OR 1.02 (0.36 to 2.84) | 277 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | — | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; LNG‐IUS: levonorgestrel intrauterine system; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||||

aDowngraded by one level for imprecision due to limited sample size and low event rate.

Background

Description of the condition

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, affecting up to one in eight women in developed countries (ACS 2020). Most of these cancers express the oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). Adjuvant treatment in most cases includes anti‐oestrogen therapy. For most premenopausal and many postmenopausal women, this is with the selective ER modulator tamoxifen. Five‐year treatment with tamoxifen is associated with a 50% relative reduction in the annual risk of recurrence during the first four years, and a 33% relative reduction in the annual risk of recurrence during years five to nine among women with ER‐positive breast cancer (EBCTCG 2011). Additionally, five‐year treatment with tamoxifen is associated with a 33% relative reduction in the annual risk of death among women with ER‐positive breast cancer (EBCTCG 2011). Ten‐year treatment with tamoxifen is associated with significant reductions in the risk of breast cancer recurrence, breast cancer mortality and overall mortality in women with ER‐positive breast cancer (Davies 2013).

Tamoxifen is a selective ER modulator (SERM), which inhibits growth of breast cancer by competitive antagonism at the ER level. However, it has partial agonist effects on the skeletal system, lipid metabolism, the vagina, and the uterus. This oestrogenic effect in the uterus may promote benign and malignant uterine pathology in tamoxifen users, such as uterine fibroids, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial polyps, which is a significant clinical problem. These effects appear to be largely confined to postmenopausal women. For example, among postmenopausal women, tamoxifen use has been associated with an increased incidence of between 8 and 36% of endometrial polyps compared to 0 to 10% in non‐users (Polin 2008). Tamoxifen use has also been associated with an increased incidence of between 1.3 and 20% of endometrial hyperplasia in postmenopausal women compared to 0 to 10% in postmenopausal women not taking tamoxifen (Polin 2008). Further, tamoxifen use has been shown to be associated with a 1.3 to 7.5 increase in the relative risk of endometrial cancer (Polin 2008). Specifically, among women with breast cancer aged 50 or older, the risk ratio was 4.0 (95% confidence interval 1.7 to 10.9) for those taking tamoxifen compared to those taking placebo (ACOG 2014; Fisher 1998). Premenopausal women do not appear to have an increased risk of endometrial cancer while taking tamoxifen (ACOG 2014; Davies 2013). Despite this adverse endometrial profile for tamoxifen users, the benefits of taking tamoxifen for 5 to 10 years outweigh the risks for most women with breast cancer (ACOG 2014; Davies 2013; NCCN 2020).

Description of the intervention

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) releases 20 μg of levonorgestrel daily from a central core. Systemic concentrations of levonorgestrel are low and most of the progestogen is delivered to the endometrial cavity (Xiao 1990), where it causes profound suppression and decidualisation of the endometrium (i.e., morphological and functional cellular changes to the endometrium in preparation for and during pregnancy) (Philip 2019), and glandular atrophy (Scommegna 1970).

How the intervention might work

Because of its profound anti‐proliferative effect, the LNG‐IUS is thought to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, and has been shown to be effective in treating established endometrial hyperplasia (Mittermeier 2020). The LNG‐IUS has been used in women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen as a way of preventing endometrial proliferation. However, the safety of the LNG‐IUS following oestrogen or progesterone receptor‐positive breast cancer is unclear (Gizzo 2014). A case control study from Finland suggested that the LNG‐IUS is associated with an increased risk for developing breast cancer (Lyytinen 2009). Small observational studies suggest that the LNG‐IUS does not adversely impact breast cancer prognosis (Trinh 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

This systematic review evaluated all available data from randomised controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of the LNG‐IUS in preventing the development of endometrial pathology (polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer) in pre‐ and postmenopausal women taking adjuvant tamoxifen following breast cancer. Additionally, it is important to determine the safety of the LNG‐IUS in regards to developing fibroids, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting and secondary breast cancer events. This is an update of a previously published review (Chin 2009b; Dominick 2015).

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) in pre‐ and postmenopausal women taking adjuvant tamoxifen following breast cancer for the outcomes of endometrial and uterine pathology including abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, and secondary breast cancer events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded quasi‐randomised and non‐randomised studies.

Types of participants

Pre‐ and postmenopausal women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen were eligible for inclusion. We excluded women if they had any of the following conditions: contraindications to the LNG‐IUS, evidence of recurrent breast cancer prior to LNG‐IUS insertion, or history of malignant disease other than breast cancer.

Types of interventions

We included trials that compared the LNG‐IUS combined with endometrial surveillance (experimental condition) versus endometrial surveillance alone (control condition).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Endometrial polyps

2. Endometrial hyperplasia

3. Endometrial cancer

Secondary outcomes

4. Fibroids

5. Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting

6. Breast cancer recurrence

7. Breast cancer‐related death

Search methods for identification of studies

Using a search strategy developed in consultation with the Information Specialist for the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGFG), we searched the following databases for all published and unpublished RCTs that compared the LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance versus endometrial surveillance alone, without language or date restrictions.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Specialised Register (CGFG), PROCITE platform (searched 29 June 2020) (Appendix 1);

the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group Specialised Register (CBCG; searched 4 March 2020) (Appendix 2);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), via The Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO) web platform (searched 29 June 2020) (Appendix 3);

MEDLINE, searched from 1946 to 29 June 2020, OVID platform (Appendix 4);

Embase, searched from 1980 to 29 June 2020, OVID platform (Appendix 5);

PsycINFO, searched from 1806 to 29 June 2020, OVID platform (Appendix 6);

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), searched from 1961 to 29 June 2020, OVID platform (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We searched 'ClinicalTrials.gov', a service of the US National Institutes of Health (www.clinicaltrials.gov), and the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch), on 29 June 2020 to identify ongoing and registered trials.

We also searched The Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); The Cochrane Library, (Appendix 8); Web of Science; OpenGrey; LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database); PubMed (Appendix 9); and Google on 29 June 2020. The search strategies for databases without appendices used similar terms as the CGFG and PubMed search strategies.

We searched references of relevant systematic reviews and RCTs, and contacted experts in the field to obtain any relevant trials and additional data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

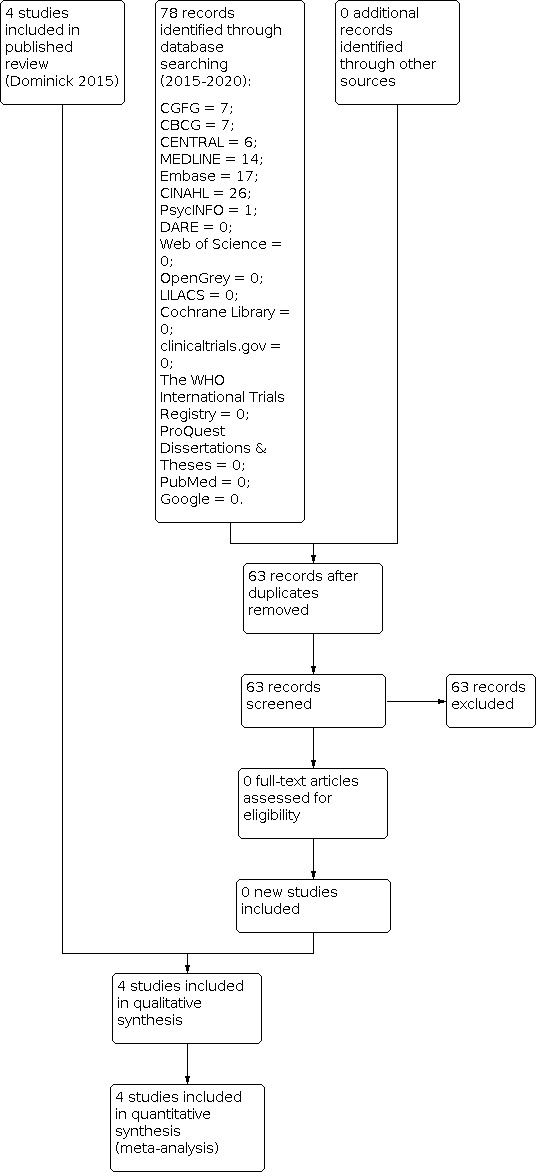

We selected studies in accordance with the described criteria. Three review authors (SADR, KY and HIS) independently, and using a standardised method, assessed eligibility of the studies retrieved from the search, see Figure 1. We resolved any disagreement by consensus.

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SADR and HIS) extracted data independently, using forms designed according to the Cochrane guidelines (Higgins 2011). For each included trial, they collected information regarding the location of the study, methods of the study (as per the 'Risk of bias' assessment checklist), the participants (age range, eligibility criteria), the nature of the interventions, and data relating to the outcomes specified in the section 'Types of outcome measures'.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SADR and HIS) independently assessed the risk of bias for all eligible studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). They resolved any discrepancies by discussion. The 'Risk of bias' criteria were as follows.

1. Selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment)

2. Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel)

3. Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment)

4. Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data)

5. Reporting bias (selective reporting)

6. Other bias

The review authors assigned each domain a high, low or unclear risk of bias rating. This information is presented in 'Risk of bias' tables for each included study as part of the Characteristics of included studies, displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and described in the text of the review (Risk of bias in included studies).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (all the outcome measures in this review), we expressed results for each study as Peto odds ratios (Peto OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We chose the Peto method because it performs well when events are very rare (Higgins 2011). We had no continuous data to consider; however, if we had encountered such data, we would have used mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Unit of analysis issues

We did not identify any unit of analysis issues due to the nature of the data generated.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis. If there had been missing data, we would have sought further information directly from the authors of the RCTs, and analysed only the available data if no additional information was forthcoming.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined the heterogeneity (variation) between the results of different studies by inspecting the scatter in the data points on a graph and the overlap in their CIs; and, more formally, by considering the I² statistic and the Chi² test P value. We would have interpreted a low P value (or a large Chi² statistic relative to its number of degrees of freedom) as providing evidence of heterogeneity of intervention effects (a variation in effect estimates beyond chance). We interpreted the I² statistic, in conjunction with consideration of the magnitude and direction of the effects seen, as follows:

0% to 40%, might not be important;

30% to 60%, may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%, may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%, may represent considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To minimise the potential impact of reporting biases, the authors conducted a comprehensive search for eligible articles and were alert for potential duplication of data. If we had included 10 or more studies in an analysis, we would have constructed funnel plots to detect reporting biases.

Data synthesis

We pooled the results statistically for each comparison (endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, fibroids, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, breast cancer recurrence and breast cancer‐related death). We carried out the meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We used the fixed‐effect method of synthesising the data for the combined analyses. If we had detected a large degree of heterogeneity, we would have considered using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not prespecify any subgroups for analysis. Due to the nature of our findings, we did not require either a post hoc subgroup analysis or an investigation of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes:

restricting eligibility to studies without high risk of bias;

using a random‐effects model; and

calculating a relative risk rather than Peto odds ratio as the summary effect measure.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We generated a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro GDT. In Table 1, we have presented our evaluation of the overall certainty of the body of evidence for the review outcomes (endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, fibroids, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, breast cancer recurrence and breast cancer‐related death) using GRADE criteria: study limitations (i.e. risk of bias); consistency of effect; imprecision; indirectness and publication bias. We have justified our judgements about the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate or low), documented these and incorporated them into the reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

At the 2015 update:

The electronic search in October 2015 retrieved a total of 315 references: CGFG = 16; CBCG = 8; CENTRAL = 5; DARE = 0; The Cochrane Library = 6; clinicaltrials.gov = 1; The World Health Organisation International Trials Registry = 1; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses = 2; MEDLINE = 54; Embase = 162; CINAHL = 37; Web of Science = 8; PsycINFO = 1; OpenGrey = 0; LILACS = 7; PubMed = 6; and Google = 1. From those, review authors identified six potential studies to be read in full; two of these six studies were already included in the previously published review, with no additional references retrieved from the manual search.

At the 2020 update:

We ran the electronic search between 1 January 2015 to 29 June 2020 and retrieved a total of 78 references. From those titles and abstracts, we did not identify any potential studies. We did not retrieve any additional references from the manual search. See Figure 1 for details of the search, screening and selection process.

Included studies

The searches identified four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for inclusion in this review (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). See Characteristics of included studies; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5 for detailed information about the included studies.

1. Chan 2007 & Wong 2013.

| Treatment Group | Control | P value | |

| 6 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 64 | 65 | — |

| Completed | 55 | 58 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 20 | 1 | <0.001 |

| 12 months follow‐up | |||

| Completed | 55 | 58 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 6 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Endometrial polyps | 1 | 9 | 0.02 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Fibroids | 1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| 24 months follow‐up | |||

| Completed | 55 | 57 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 6 | 3 | 0.45 |

| 45 months follow‐up | |||

| Completed | 48 | 52 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 60 months follow‐up | |||

| Completed | 46 | 48 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Endometrial polyps | 2 | 16 | < 0.001 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Endometrial cancer | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Fibroids | 1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Breast cancer recurrence | 10 | 6 | 0.25 |

| Breast cancer‐related deaths | 6 | 5 | 0.71 |

NA: not applicable

2. Gardner 2000 & 2009.

| Treatment Group | Control | P value | |

| 12 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 64 | 58 | — |

| Completed | 47 | 52 | — |

| Endometrial polyps | 1 | 4 | 0.4 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Fibroids | 1 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Final follow‐up (24, 36, or 48 months) | |||

| Completed at 24 months | 31 | 29 | — |

| Completed at 36 months | 19 | 20 | — |

| Completed at 48 months | 6 | 9 | — |

| Endometrial polyps | 3 | 8 | 0.2 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 1 | NR |

| Endometrial cancer | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Breast cancer recurrence | 1 | 1 | NR |

| Breast cancer‐related deaths | 2 | 2 | NR |

NA: not applicable NR: not reported

3. Kesim 2008.

| Treatment Group | Control | P value | |

| 5 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 70 | 72 | — |

| Completed | 70 | 72 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 7 | 0 | NR |

| 12 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 70 | 72 | — |

| Completed | 70 | 72 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 36 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 70 | 72 | — |

| Completed | 70 | 72 | — |

| Endometrial polyps | 4 | 14 | < 0.05 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 4 | < 0.05 |

NA: not applicable NR: not reported

4. Omar 2010.

| Treatment Group | Control | P value | |

| 12 months follow‐up | |||

| Randomised | 75 | 75 | — |

| Completed | 60 | 63 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 22 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Breast cancer‐related deaths | 0 | 1 | NR |

| 24 months follow‐up | |||

| Completed | 59 | 62 | — |

| Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 7 | 2 | 0.08 |

| Endometrial polyps | 1 | 10 | 0.02 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Fibroids | 2 | 4 | 1.1 |

NA: not applicable NR: not reported

Study design and setting

The four RCTs took place in Egypt (Omar 2010), Turkey (Kesim 2008), the UK (Gardner 2000), and Hong Kong (Chan 2007). The Gardner 2000 and Chan 2007 trials published long‐term follow‐up in separate publications (Gardner 2009 and Wong 2013, respectively).

Participants

The trials included 543 pre‐ and postmenopausal women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen; 273 women in the treatment groups and 270 women in the control groups.

Interventions

All four trials compared endometrial surveillance plus the LNG‐IUS, which releases 20 μg/day of the synthetic progestogen levonorgestrel, to endometrial surveillance alone. The Chan 2007 trial (follow‐up: 60 months) compared endometrial surveillance alone versus endometrial surveillance plus the LNG‐IUS insertion before the commencement of tamoxifen in pre‐ and postmenopausal women. The Gardner 2000 trial (follow‐up: 48 months) compared endometrial surveillance alone versus endometrial surveillance with insertion of the LNG‐IUS in postmenopausal women who had been taking adjuvant tamoxifen treatment for at least one year. The Kesim 2008 trial (follow‐up: 36 months) compared endometrial surveillance alone versus endometrial surveillance with insertion of the LNG‐IUS in postmenopausal women who had been taking adjuvant tamoxifen treatment for more than one year. The Omar 2010 trial (follow‐up: 24 months) compared endometrial surveillance alone versus endometrial surveillance with insertion of the LNG‐IUS before the commencement of tamoxifen in pre‐ and postmenopausal women who required postoperative adjuvant tamoxifen.

Outcomes

All four trials reported endometrial polyps diagnosed at hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010).

All four trials reported endometrial hyperplasia diagnosed at hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010).

Two of the four trials reported endometrial cancer (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000).

Three of the four trials reported fibroids (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Omar 2010).

Three of the four trials reported abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting (Chan 2007; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010).

Two of the four trials reported breast cancer recurrence (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000).

Three of the four trials reported breast cancer‐related death (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Omar 2010).

Excluded studies

There were no excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for detailed information.

Allocation

Three trials had a low risk of selection bias related to sequence generation, as they used computer‐generated random number series for allocation (Chan 2007; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). One trial did not describe the sequence generation method used, so had an unclear risk of selection bias related to sequence generation (Gardner 2000).

All trials used pre‐prepared, serially‐numbered sealed envelopes, so had a low risk of selection bias related to allocation concealment (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010).

Blinding

All trials had a low risk of detection and performance bias as the pathologists (i.e. outcome assessors) were blinded (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). Even though the provider and participant were not blinded, given the nature of this clinical intervention (insertion of the LNG‐IUS), the blinding of providers and participants is considered unlikely to influence the outcomes.

Incomplete outcome data

Two trials were at low risk of attrition bias as the majority of randomised participants were included in the final analyses (Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). There were no evidence of differences in baseline data between women who completed and did not complete the study in either of these trials.

The trial by Chan 2007 had an unclear risk of attrition bias. At 12 months of follow‐up, 16/129 (12%) of the participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out (seven women in the control group and nine in the treatment group). At 60 months of follow‐up, 35/129 (27%) participants were lost to follow‐up (17 in the control group and 18 in the treatment group).

The Gardner 2000 trial also had an unclear risk of attrition bias. At 12 months of follow‐up, 23/122 (19%) of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out (six in the control group and 17 in the treatment group). There was no evidence of differences in baseline data between women who completed and did not complete the study; hence the 12‐month follow‐up data are at low risk of attrition bias. However, the follow‐up data at 24, 36 and 48 months are at high risk of attrition bias due to their high losses to follow‐up. At 24 months of follow‐up, 62/122 (51%) of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. At 36 months of follow‐up, 83/122 (68%) of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. At 48 months of follow‐up, 107/122 (88%) of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out.

Selective reporting

Although all four studies reported our review's primary and secondary outcomes, we rated them all to have an unclear risk of reporting bias (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). We could not obtain protocols for any of the trials, and the studies were not prospectively registered, so there was no information we could use to verify the study details. Due to the small number of included studies (less than 10), it was not appropriate to construct funnel plots to investigate publication bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1.

LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance versus endometrial surveillance alone

Primary outcomes

Endometrial polyps

At short‐term follow‐up (12 months), we pooled data from two trials (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000). The pooled result suggests that LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance is probably associated with a slight reduction in the incidence of endometrial polyps compared to endometrial surveillance alone (Peto OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.64; I² = 0%; 2 RCTS, n = 212; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 1: Endometrial polyps

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.1 Endometrial polyps.

At long‐term follow‐up (24 to 60 months), we pooled data from all four trials (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). The pooled analysis suggests that LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance is probably associated with a reduction in the incidence of endometrial polyps compared to endometrial surveillance alone (Peto OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.39; I² = 0%; 4 RCTs, n = 417; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). This suggests that if the incidence of endometrial polyps following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 23.5%, the incidence following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 3.8% and 10.7%.

Endometrial hyperplasia

At long‐term follow‐up (24 to 60 months), the pooled data from all four trials showed only six cases of endometrial hyperplasia in the control group, which suggests that LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance is probably associated with a slight reduction in the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia compared to endometrial surveillance alone (Peto OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.67; I² = 0%; 4 RCTs, n = 417; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). This suggests that if the chance of endometrial hyperplasia following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 2.8%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 0.1% and 1.9%.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 2: Endometrial hyperplasia

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.2 Endometrial hyperplasia.

Endometrial cancer

The included studies reported no cases of endometrial cancer. Hence, we could not calculate statistics for the endometrial cancer outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Fibroids

We pooled data from three trials (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Omar 2010). The pooled analysis showed that there is probably little or no difference in the incidence of fibroids between LNG‐IUS users compared to the control group with endometrial surveillance (Peto OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.46; I² = 0%; 3 RCTs, n = 314; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3; Figure 6). This suggests that if the chance of fibroids following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 5.8%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 1.0% and 8.2%.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 3: Fibroids

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.4 Fibroids.

Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting

At 12 months of follow‐up, three trials reported on abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting in the LNG‐IUS and control groups (Chan 2007; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). At 24 months of follow‐up, two of these trials reported on abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting (Chan 2007; Omar 2010). Only the trial by Chan 2007 reported on findings at 45 and 60 months of follow‐up. At 12 months of follow‐up, LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance is probably associated with an increase in the incidence of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting compared to endometrial surveillance alone (Peto OR 7.26, 95% CI 3.37 to 15.66; I² = 0%; 3 RCTs, n = 376; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 7). This suggests that if the incidence of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 1.7%, the incidence following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 5.6% and 21.5%.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 4: Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.5 Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting.

At 24 months of follow‐up, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting was reduced in both groups, but still higher in the LNG‐IUS group compared to the control group (Peto OR 2.72, 95% CI 1.04 to 7.10; I² = 0%; 2 RCTs, n = 233; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 7). This suggests that if the chance of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 4.2%, the chance following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 4.4% and 23.9%. By 45 and 60 months of follow‐up, no cases of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting were reported in either group (Analysis 1.4; Figure 7).

Breast cancer recurrence

Pooled data from two trials showed that there is probably little or no difference in breast cancer recurrence between LNG‐IUS users compared to the control group with endometrial surveillance (Peto OR 1.74, 95% CI 0.64 to 4.74; I² = 0%; 2 RCTs, n = 154; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 8) (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000). This suggests that if the risk of breast cancer recurrence following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 8.0%, the risk following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 5.3% and 29.1%.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 5: Breast cancer recurrence

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.6 Breast cancer recurrence.

Breast cancer‐related death

Pooled data from three trials showed that there is probably little or no difference in breast cancer‐related deaths in LNG‐IUS users compared to the control group with endometrial surveillance (Peto OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.84; I² = 0%; 3 RCTs, n = 277; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6; Figure 9) (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Omar 2010). This suggests that if the risk of breast cancer‐related deaths following endometrial surveillance alone is assumed to be 6.9%, the risk following LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance would be between 2.6% and 17.4%.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, Outcome 6: Breast cancer‐related death

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone, outcome: 1.7 Breast cancer‐related death.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not conduct the planned sensitivity analysis by risk of bias, because risk of bias was similar across the included studies.

We conducted the planned sensitivity analyses by statistical model and effect estimate. When switching the pooled estimate from Peto odds ratio to Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratio, and from fixed‐effect to random‐effects models for all outcomes, only the pooled estimate for the endometrial hyperplasia outcome changed. This showed little or no difference in endometrial hyperplasia between the groups (RR fixed‐effect 0.19, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.15; 4 RCTs, n = 417).

Discussion

Summary of main results

See Table 1.

This review included four randomised controlled trials that compared endometrial protection by the 20 μg/day levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) plus endometrial surveillance versus endometrial surveillance alone in women with breast cancer on adjuvant tamoxifen. The pooled data from the included studies showed that the LNG‐IUS probably reduces the incidence of endometrial polyps over a 12‐month period and a long‐term follow‐up period (24 to 60 months) among women with breast cancer taking tamoxifen. The LNG‐IUS probably also slightly reduces the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia over a long‐term follow‐up period (24 to 60 months). The pooled data showed the LNG‐IUS probably increases abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting compared to the control group at 12 months and 24 months of follow‐up. However, there was a gradual reduction of abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting from 12 to 24 months, and no bleeding or spotting in either group was reported at 45 or 60 months of follow‐up. Additionally, there was probably little or no difference in the risk of fibroids (n = 13), breast cancer recurrence (n = 18), and breast cancer‐related deaths (n = 16) between the LNG‐IUS treatment group and the control group. Since none of the studies reported cases of endometrial cancer, there were insufficient data to show an effect on the incidence of endometrial cancer.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All four included studies used the 'gold standard' of hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy to diagnose endometrial pathology (ACOG 2015; Chan 2007; Gardner 2000; Kesim 2008; Omar 2010). Endometrial pathology prior to randomisation was excluded by hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy; any endometrial pathology detected at baseline was treated. Endometrial pathology was the primary end point for all four studies. However, the timing of the primary end point assessment varied by study, ranging from 12 to 60 months.

While the four included studies differed in their participant selection, inclusion criteria, secondary outcomes assessed, and overall study design (see Characteristics of included studies), they provided adequate information to answer the review question. The findings of this review provide evidence that the LNG‐IUS prevents endometrial polyps and endometrial hyperplasia in women with breast cancer using tamoxifen. However, the data are insufficient to determine if the LNG‐IUS protects or does not protect tamoxifen users from endometrial cancer.

Quality of the evidence

Using the GRADE system, we assessed the certainty of the evidence to be moderate for all study outcomes (i.e. endometrial polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, fibroids, abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting, breast cancer recurrence and breast cancer‐related death). For all four studies, we downgraded the evidence by one level for imprecision due to limited sample sizes and low event rates for the study outcomes. Of note, none of the studies were sufficiently powered to address whether the LNG‐IUS protects women on tamoxifen against endometrial cancer.

Further, a potential limitation of this review is the inclusion of both pre‐ and postmenopausal women in two of the included studies (Chan 2007; Omar 2010). This may have underestimated the effect of the LNG‐IUS in preventing endometrial pathology in postmenopausal women.

Potential biases in the review process

The authors did not identify any potential biases in the review process. Based on the comprehensive literature search and included search terms, we are confident that all relevant studies were identified and included in this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We did not identify any other reviews.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) probably reduces the risk of benign polyps in tamoxifen users. This is clinically significant since polyps may be symptomatic; when identified they require removal, which is likely to include a general anaesthetic and hysteroscopy. The LNG‐IUS probably slightly reduces the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia in women on tamoxifen following breast cancer. There is no evidence that the LNG‐IUS reduces or does not reduce the risk of endometrial cancer in women on tamoxifen following breast cancer, as there were no cases in any of the included studies. The LNG‐IUS probably increases abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting for up to 24 months in tamoxifen users, which may increase the need for invasive diagnostic procedures to exclude hyperplasia and malignancy. The safety of the LNG‐IUS in women with breast cancer in terms of prognosis, breast cancer recurrence, or breast cancer‐related deaths is uncertain.

Implications for research.

Studies powered to detect changes in the incidence of endometrial cancer in women with breast cancer using tamoxifen are needed. Since endometrial cancer risks with tamoxifen are limited to postmenopausal women, future studies should focus on this population. Larger studies are also necessary to assess whether the LNG‐IUS may impact prognosis after breast cancer or secondary breast cancer events. Since aromatase inhibitors have been shown to be more effective than tamoxifen in preventing recurrence of oestrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer, prescribing patterns of tamoxifen as adjuvant endocrine therapy have changed in the past decade (EBCTCG 2015; NCCN 2020). As a result, endometrial stimulation with tamoxifen and the need for LNG‐IUS to lower this risk may be less clinically significant.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 February 2021 | Review declared as stable | No new studies are expected; any future evidence is unlikely to change the conclusions of this review |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2008 Review first published: Issue 4, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 July 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new studies were identified for inclusion at this update. |

| 8 May 2020 | New search has been performed | Review updated to reflect current formatting of Cochrane Reviews and updated search. |

| 9 November 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No changes to conclusions of this review. |

| 9 November 2015 | New search has been performed | Two new studies (Kesim 2008; Omar 2010) and a follow up of two previously included studies (Chan 2007; Gardner 2000) were identified for inclusion in this update. |

| 20 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. New RCT included into review. |

| 6 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 26 April 2007 | New citation required and major changes | Substantive amendment |

Notes

Former review author Professor Justin C Konje is a co‐author for one of the randomised controlled trials included in this review (Gardner 2000)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group for providing us with the search strategy, support, and advice for this review. In particular, we wish to acknowledge Helen Nagels, Marian Showell and Ava Tan‐Koay for their contributions to this review.

The authors of the 2020 update thank Dr Jason Chin, Dr Justin C. Konje, and Jane Marjoribanks for their contributions to previous versions of this review, and also thank Dr Michelle Wise and Dr Vanessa Jordan for providing peer review feedback.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group's (CGFG) specialised register search strategy

PROCITE platform

Searched 29 June 2020

Keywords CONTAINS "IUD" or "levonorgestrel intrauterine system" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" or "Levonorgestrel‐Therapeutic‐Use" or "LNG‐IUS" or "LNG20"or "Intrauterine Releasing Devices" or "Intrauterine Devices Medicated" or "intrauterine devices" or "intrauterine device" or "intrauterine contraceptive devices" or "Mirena" or Title CONTAINS "IUD" or "levonorgestrel intrauterine system" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device" or "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" or "Levonorgestrel‐Therapeutic‐Use" or "LNG‐IUS" or "LNG20"or "Intrauterine Releasing Devices" or "Intrauterine Devices Medicated" or "intrauterine devices" or "intrauterine device" or "intrauterine contraceptive devices" or "Mirena"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "breast cancer" or "breast cancer incidence" or "breast changes" or "breast disease" or "breast outcomes"or "cancer risk"or "endometrial cancer"or "endometrial hyperplasia"or"endometrial pathology"or"endometrial polyps" or "endometrial proliferation" or "polyps" or Title CONTAINS "breast cancer" or "breast cancer incidence" or "breast changes"or "breast disease"or "breast outcomes" or "cancer risk" or "endometrial cancer" or "endometrial hyperplasia" or "endometrial pathology" or "endometrial polyps" or "endometrial proliferation" or "polyps"

21 records

Appendix 2. Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's (CBCG) specialised register search strategy

Searched 4 March 2020

Details regarding the search strategies used by the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group for the identification of studies and procedures used to code references for the Specialised Register are outlined in the Group’s module: www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clabout/articles/BREASTCA/frame.html

The following key words were used to identify relevant studies for consideration: "IUD", "intrauterine devices", "intrauterine system", "levonorgestrel intrauterine system", "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device", "levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system", "levonorgestrel‐therapeutic use", "LNG‐IUS", "LNG20" and "Mirena".

Appendix 3. CENTRAL via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO) search strategy

Web platform

Searched 29 June 2020

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Breast Neoplasms EXPLODE ALL TREES 12743

#2 (Breast adj2 cancer* ):TI,AB,KY 33473

#3 (Breast adj2 neoplasm* ):TI,AB,KY 13818

#4 (Breast adj2 carcinoma* ):TI,AB,KY 1720

#5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 35387

#6 MESH DESCRIPTOR Intrauterine Devices, Medicated EXPLODE ALL TREES 400

#7 (Intrauterine Device*):TI,AB,KY 1292

#8 (LNG IUS or LNG IUD):TI,AB,KY 316

#9 (Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system*):TI,AB,KY 243

#10 (Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device*):TI,AB,KY 63

#11 mirena:TI,AB,KY 148

#12 IUD*:TI,AB,KY 1196

#13 #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 1960

#14 MESH DESCRIPTOR Intrauterine Devices, Medicated EXPLODE ALL TREES WITH QUALIFIERS AE 175

#15 MESH DESCRIPTOR Neoplasm Recurrence, Local EXPLODE ALL TREES 4041

#16 MESH DESCRIPTOR Endometrial Hyperplasia EXPLODE ALL TREES 146

#17 MESH DESCRIPTOR Endometrial Neoplasms EXPLODE ALL TREES 595

#18 MESH DESCRIPTOR Adenocarcinoma EXPLODE ALL TREES 7265

#19 MESH DESCRIPTOR Neoplasm Metastasis EXPLODE ALL TREES 5057

#20 MESH DESCRIPTOR Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal EXPLODE ALL TREES WITH QUALIFIERS AE 2568

#21 MESH DESCRIPTOR Tamoxifen EXPLODE ALL TREES WITH QUALIFIERS AE 459

#22 (breast cancer adj2 recurrence*):TI,AB,KY 490

#23 (recurrent breast cancer):TI,AB,KY 258

#24 (Local Neoplasm Recurrence*):TI,AB,KY 0

#25 (secondary breast cancer*):TI,AB,KY 12

#26 (secondary neoplasm*):TI,AB,KY 166

#27 (secondary cancer*):TI,AB,KY 67

#28 (Neoplasm Metastasis):TI,AB,KY 3317

#29 (cancer metastasis):TI,AB,KY 92

#30 (advanced breast cancer):TI,AB,KY 3005

#31 (breast cancer survival):TI,AB,KY 112

#32 (Endometrial Hyperplasia):TI,AB,KY 406

#33 (Endometri* patholog*):TI,AB,KY 263

#34 (Endometri* polyp*):TI,AB,KY 212

#35 (Endometr* adenocarcinoma*):TI,AB,KY 103

#36 (endometri* adj2 cancer*):TI,AB,KY 1627

#37 #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 22918

#38 #5 AND #13 AND #37 11

Appendix 4. MEDLINE search strategy

OVID platform

Searched from 1946 to 29 June 2020

1 exp Breast Neoplasms/ (291348) 2 Breast Neoplasms, Male/ (3028) 3 1 not 2 (288320) 4 (Breast cancer$ or Breast Neoplasm$).tw. (273937) 5 3 or 4 (369193) 6 exp Intrauterine Devices, Medicated/ (3345) 7 Intrauterine Device$.tw. (5471) 8 (LNG IUS or LNG IUD).tw. (870) 9 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system$.tw. (668) 10 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device$.tw. (205) 11 (IUD$ or Mirena).tw. (9070) 12 or/6‐11 (12985) 13 Intrauterine Devices, Medicated/ae [Adverse Effects] (484) 14 exp Neoplasm Recurrence, Local/ (117316) 15 exp Endometrial Hyperplasia/ (3515) 16 exp Endometrial Neoplasms/ (21628) 17 exp Adenocarcinoma/ (378194) 18 exp Neoplasm Metastasis/ (202842) 19 exp Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal/ae [Adverse Effects] (18050) 20 exp Tamoxifen/ae [Adverse Effects] (3058) 21 breast cancer recurrence$.tw. (1614) 22 recurrent breast cancer.tw. (1471) 23 Local Neoplasm Recurrence$.tw. (4) 24 secondary breast cancer$.tw. (102) 25 secondary neoplasm$.tw. (534) 26 secondary cancer$.tw. (1225) 27 Neoplasm Metastasis.tw. (93) 28 cancer metastasis.tw. (11227) 29 advanced breast cancer.tw. (8489) 30 breast cancer survival.tw. (1428) 31 Endometrial Hyperplasia.tw. (3099) 32 Endometri$ patholog$.tw. (834) 33 Endometri$ polyp$.tw. (1559) 34 Endometrial adenocarcinoma$.tw. (3157) 35 endometrial cancer.tw. (16521) 36 or/13‐35 (673432) 37 5 and 12 and 36 (64)

Appendix 5. EMBASE search strategy

OVID platform

Searched from 1980 to 29 June 2020

1 exp breast tumor/ (517080) 2 (Breast cancer$ or Breast Neoplasm$).tw. (391862) 3 breast tumor$.tw. (27398) 4 or/1‐3 (565673) 5 exp intrauterine contraceptive device/ (16040) 6 Intrauterine Device$.tw. (6363) 7 (LNG IUS or LNG IUD).tw. (1420) 8 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system$.tw. (908) 9 Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine device$.tw. (277) 10 (IUD$ or Mirena).tw. (9347) 11 or/5‐10 (19511) 12 intrauterine contraceptive device/ae [Adverse Drug Reaction] (630) 13 exp tumor recurrence/ (55980) 14 exp endometrium hyperplasia/ (7326) 15 exp endometrium tumor/ (61399) 16 exp breast adenocarcinoma/ or exp adenocarcinoma/ (216342) 17 exp metastasis/ (610807) 18 "antineoplastic hormone agonists and antagonists"/ae [Adverse Drug Reaction] (601) 19 exp tamoxifen/ae [Adverse Drug Reaction] (7165) 20 breast cancer recurrence$.tw. (2744) 21 recurrent breast cancer$.tw. (2059) 22 Local Neoplasm Recurrence$.tw. (6) 23 secondary breast cancer$.tw. (211) 24 secondary neoplasm$.tw. (753) 25 secondary cancer$.tw. (1929) 26 Neoplasm Metastasis.tw. (89) 27 cancer metastasis.tw. (15530) 28 advanced breast cancer.tw. (12415) 29 breast cancer survival.tw. (1994) 30 Endometrial Hyperplasia.tw. (4378) 31 Endometri$ patholog$.tw. (1328) 32 Endometri$ polyp$.tw. (2590) 33 Endometrial adenocarcinoma$.tw. (4117) 34 endometrial cancer.tw. (25327) 35 or/12‐34 (892520) 36 4 and 11 and 35 (201) 37 Clinical Trial/ (966546) 38 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (604378) 39 exp randomization/ (87180) 40 Single Blind Procedure/ (39259) 41 Double Blind Procedure/ (170471) 42 Crossover Procedure/ (63399) 43 Placebo/ (337665) 44 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (230377) 45 Rct.tw. (37455) 46 random allocation.tw. (2017) 47 randomly allocated.tw. (35256) 48 allocated randomly.tw. (2545) 49 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (816) 50 Single blind$.tw. (24736) 51 Double blind$.tw. (202894) 52 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (1151) 53 placebo$.tw. (303091) 54 prospective study/ (607350) 55 or/37‐54 (2193765) 56 case study/ (69905) 57 case report.tw. (403638) 58 abstract report/ or letter/ (1100959) 59 or/56‐58 (1563903) 60 55 not 59 (2140187) 61 36 and 60 (68)

Appendix 6. PyscINFO search strategy

OVID platform

Searched from 1806 to 29 June 2020

1 exp Intrauterine Devices/ (141) 2 Levonorgestrel.tw. (117) 3 intrauterine device$.tw. (301) 4 iud.tw. (238) 5 mirena.tw. (11) 6 intrauterine system$.tw. (47) 7 exp Breast Neoplasms/ (9851) 8 breast neoplasm$.tw. (160) 9 breast tumor$.tw. (101) 10 (breast adj5 ca).tw. (1) 11 (breast adj5 cancer$).tw. (13688) 12 or/1‐6 (518) 13 or/7‐11 (13957) 14 12 and 13 (2)

Appendix 7. CINAHL search strategy

EBSCO platform

Searched from 1961 to 29 June 2020

| # | Query | Results |

| S13 | S6 AND S13 | 78 |

| S12 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 | 4,877 |

| S11 | TX(IUD* or Mirena*) | 1,968 |

| S10 | TX (Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine) | 402 |

| S9 | TX (LNG IUD) | 106 |

| S8 | TX (LNG IUS) | 276 |

| S7 | TX Intrauterine Device* | 4,245 |

| S6 | (MM "Intrauterine Devices") | 2,072 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 | 110,002 |

| S4 | TX (Breast cancer* or Breast Neoplasm*) | 109,268 |

| S3 | TX breast tumour* | 1,141 |

| S2 | TX breast tumor* | 5,634 |

| S1 | (MM "Breast Neoplasms+") | 72,057 |

Appendix 8. The Cochrane Library

Web platform

Searched 29 June 2020

#1 "Clinical Trial" or "Phase I Clinical Trial" or "Phase II Clinical Trial" or "Phase III Clinical Trial" or "Phase IV Clinical Trial" or "Controlled Clinical Trial" or "Multicenter Study" or "Randomized Controlled Trial" or "Pragmatic Clinical Trial" in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews and Protocols) and Trials

#2 mh "Breast Neoplasms" not mh "Breast Neoplasms, Male" or "Breast cancer" or "Breast Neoplasms"

#3 mh "Intrauterine Devices" or mh "Levonorgestrel" or "Intrauterine Devices" or "IUD" or "Medicated Intrauterine Devices" or "LNG IUS" or "Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" or "Mirena" or "Levonorgestrel"

#4 mh "Intrauterine Devices/adverse effects" or mh "Levonorgestrel/adverse effects" or mh "Neoplasm Recurrence, Local" or mh "Breast Neoplasms/secondary" or mh "Neoplasms/secondary" or mh "Endometrial Hyperplasia" or mh "Neoplasm Metastasis" or "breast cancer recurrence" or "recurrent breast cancer" or "Local Neoplasm Recurrence" or "secondary breast cancer" or "secondary neoplasms" or "secondary cancers" or "Neoplasm Metastasis" or "cancer metastasis" or "breast cancer metastasis" or "advanced breast cancer" or "breast cancer survival" or "Endometrial Hyperplasia" or "Endometrial pathology" or "Endometrial polyps" or "Endometrial adenocarcinoma" or "endometrial cancer"

#5 #1 and #2 and #3 and #4

Appendix 9. PubMed search

Searched from 1946 to 29 June 2020

(("Clinical Trial"[Publication Type]) OR ("Phase I Clinical Trial" OR "Phase II Clinical Trial" OR "Phase III Clinical Trial" OR "Phase IV Clinical Trial" OR "Controlled Clinical Trial" OR "Multicenter Study" OR "Randomized Controlled Trial" OR "Pragmatic Clinical Trial"))

AND

(("Breast Neoplasms"[Mesh] NOT "Breast Neoplasms, Male"[Mesh]) OR ("Breast cancer" OR "Breast Neoplasms"))

AND

(("Intrauterine Devices, Medicated"[Mesh]) OR ("Intrauterine Devices" OR "IUD" OR "Medicated Intrauterine Devices" OR "LNG IUS" OR "Levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system" OR "Mirena"))

AND

(("Intrauterine Devices, Medicated/adverse effects"[Mesh]) OR ("Neoplasm Recurrence, Local"[Mesh] OR "Breast Neoplasms/secondary"[Mesh] OR "Neoplasms/secondary"[Mesh] OR "Endometrial Hyperplasia"[Mesh] OR "Endometrial Neoplasms"[Mesh] OR "Adenocarcinoma" [Mesh] OR "Neoplasm Metastasis"[Mesh] OR "Antineoplastic Agents, Hormonal/adverse effects"[Mesh] OR "Tamoxifen/adverse effects"[Mesh]) OR ("breast cancer recurrence" OR "recurrent breast cancer" OR "Local Neoplasm Recurrence" OR "secondary breast cancer" OR "secondary neoplasms" OR "secondary cancers" OR "Neoplasm Metastasis" OR "cancer metastasis" OR "breast cancer metastasis" OR "advanced breast cancer" OR "breast cancer survival" OR "Endometrial Hyperplasia" OR "Endometrial pathology" OR "Endometrial polyps" OR "Endometrial adenocarcinoma" OR "endometrial cancer"))

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. LNG‐IUS with endometrial surveillance (ES) versus endometrial surveillance alone.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Endometrial polyps | 4 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1.1 Short term follow‐up (12 months) | 2 | 212 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.08, 0.64] |

| 1.1.2 Long term follow‐up (24 to 60 months) | 4 | 417 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.13, 0.39] |

| 1.2 Endometrial hyperplasia | 4 | 417 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.03, 0.67] |

| 1.3 Fibroids | 3 | 314 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.16, 1.46] |

| 1.4 Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting | 3 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.4.1 12 months | 3 | 376 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.26 [3.37, 15.66] |

| 1.4.2 24 months | 2 | 233 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.72 [1.04, 7.10] |

| 1.4.3 45 months | 1 | 100 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.4.4 60 months | 1 | 94 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.5 Breast cancer recurrence | 2 | 154 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [0.64, 4.74] |

| 1.6 Breast cancer‐related death | 3 | 277 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.36, 2.84] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Chan 2007.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Pre‐ and postmenopausal women who required adjuvant tamoxifen for breast cancer after completion of postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy. 129 women randomised. Exclusion criteria included contraindication for intrauterine device, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, congenital uterine anomaly or uterine cavity length > 10 cm. |

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared:

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study funding: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Women were randomized to either LNG‐IUS treatment or control according to a computer‐generated random number series in serially numbered sealed envelopes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Serially numbered sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "A histopathologist was blinded to the randomisation and the stage of tamoxifen treatment." Even though the provider and participant were not blinded given the clinical intervention (insertion of the LNG‐IUS), the blinding of providers and participants is considered very unlikely to influence the outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | At 12 months of follow‐up, 16/129 (12%) participants (7 in the control group and 9 in the treatment group) were lost to follow up or dropped out. 113 women (58 in the control and 55 in the treatment group) were analysed. At 60 months of follow up, 35/129 (27%) participants (17 in the control group and 18 in the treatment group) were lost to follow up. 94 women (48 in the control and 46 in the treatment group) were analysed. There is no description of the population who dropped out or comparison of drop‐outs to participants who remained in the study; as such this is judged as unclear risk of bias. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Although this study reported our review's outcomes, we could not obtain a study protocol and the study was not prospectively registered so there was no information we could use to verify the study details. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No additional biases to report. |

Gardner 2000.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Postmenopausal women who had been on adjuvant tamoxifen for at least 12 months. Postmenopause was defined by serum estradiol < 50 pmol/L. 122 women randomised; 9 were excluded after randomisation (6 were premenopausal, 3 with unsatisfactory hysteroscopy). Additional exclusion criteria included suspected pelvic inflammatory disease, active liver disease, history of malignant disease other than breast cancer, grade 3 submucous fibroid, endometrial polyps, and refusal to receive the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. |

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared:

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study funding: a grant from Trent NHS Research and Development, with support from The University of Leicester and The University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on random sequence generation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation was done by pre‐prepared serially numbered sealed envelopes. Each woman was allocated the next envelope in the series and received either an LNG‐IUS (LNG‐IUS Group) or endometrial surveillance only (Surveillance Group)." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "To keep interobserver error to a minimum, one consultant histopathologist, who was unaware of the randomisation, used standard criteria to assess all endometrial specimens." Even though the provider and participant were not blinded, given the clinical intervention (insertion of the LNG‐IUS), the blinding of providers and participants is considered very unlikely to influence the outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | At 12 months of follow‐up, 23/122 (19%) of participants (6 in control group and 17 in treatment group) were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. 99 women (52 in control and 47 in treatment) were included in the analyses. There were no evidence of differences in baseline data between women who completed and did not complete the study. These data are at low risk of attrition bias. The 24, 36 and 48 months follow up data are considered at high risk of attrition bias. At 24 months of follow‐up, 62/122 (51%) of participants were not included in the analyses as they were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. At 36 months of follow‐up, 83/122 (68%) of participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. At 48 months of follow‐up, only 15 women were included in the analyses, due to 107/122 (88%) of participants lost to follow‐up or dropped out. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Although this study reported our review's outcomes, we could not obtain a study protocol and the study was not prospectively registered so there was no information we could use to verify the study details. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No additional bias to report. |

Kesim 2008.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Postmenopausal women who had been on adjuvant tamoxifen for more than 12 months. 148 women randomised; 6 were excluded after randomisation (2 who refused LNG‐IUS, and 4 in whom the LNG‐IUS could not be fitted). Exclusion criteria included contraindication for intrauterine device (such as pelvic inflammatory disease), progestogen treatment since diagnosis of breast cancer, history of malignant disease other than breast cancer, allergy to polyethylene, and refusal to receive the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. |

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared:

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study funding: not reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was performed by computer‐aided numbering of sealed envelopes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Biopsy specimens were fixed and hemotoxylin‐eosin stained sections were produced in a standard manner and evaluated by the same histopathologist, who was unaware of the randomization." Even though the provider and participant were not blinded given the clinical intervention (insertion of the LNG‐IUS), the blinding of providers and participants is considered very unlikely to influence the outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | After randomisation, 6/148 (4%) of women were excluded (2 who refused LNG‐IUS, and 4 in whom the LNG‐IUS could not be fitted). At 36 months of follow‐up, 0 participants were lost to follow‐up or dropped out. 142 women were included in the analyses. These data are at low risk of attrition bias. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Although this study reported our review's outcomes, we could not obtain a study protocol and the study was not prospectively registered so there was no information we could use to verify the study details. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No additional bias to report. |

Omar 2010.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Pre‐ and postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer who required adjuvant tamoxifen after completion of postoperative radiation and chemotherapy. 150 women randomised; 18 were excluded after randomisation (8 from the control and 10 from the treatment group declined participation). At baseline, 9 women (4 from control and 5 from treatment) were excluded due to an unsuccessful hysteroscopy. Exclusion criteria included age > 60 years, contraindications for intrauterine device (such as pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine cavity > 8 cm), active liver disease, history of progestogen treatment since diagnosis of breast cancer, history of malignant disease other than breast cancer, allergy to polyethylene, and refusal to receive the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. |

|

| Interventions | Two interventions compared:

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Study funding: not reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Women who consented to participate in the study were randomized to the LNG‐IUS treatment or control group according to a computer generated random number series in serially numbered sealed envelopes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "serially numbered sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "All specimens were fixed with hematoxylin and eosin and examined with a pathologist who was blinded to the randomizations." Even though the provider and participant were not blinded given the clinical intervention (insertion of the LNG‐IUS), the blinding of providers and participants is considered very unlikely to influence the outcomes. |