Zika virus causes birth defects and can lead to neurological disease in adults. While infection rates are currently low, Zika virus (ZIKV) remains a public health concern with no treatment or vaccine available.

KEYWORDS: antiviral, autophagy, trehalose, zika virus

ABSTRACT

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne human pathogen that causes congenital Zika syndrome and neurological symptoms in some adults. There are currently no approved treatments or vaccines for ZIKV, and exploration of therapies targeting host processes could avoid viral development of drug resistance. The purpose of our study was to determine if the nontoxic and widely used disaccharide trehalose, which showed antiviral activity against human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in our previous work, could restrict ZIKV infection in clinically relevant neural progenitor cells (NPCs). Trehalose is known to induce autophagy, the degradation and recycling of cellular components. Whether autophagy is proviral or antiviral for ZIKV is controversial and depends on cell type and specific conditions used to activate or inhibit autophagy. We show here that trehalose treatment of NPCs infected with recent ZIKV isolates from Panama and Puerto Rico significantly reduces viral replication and spread. In addition, we demonstrate that ZIKV infection in NPCs spreads primarily cell-to-cell as an expanding infectious center, and NPCs are infected via contact with infected cells far more efficiently than by cell-free virus. Importantly, ZIKV was able to spread in NPCs in the presence of neutralizing antibody.

IMPORTANCE Zika virus causes birth defects and can lead to neurological disease in adults. While infection rates are currently low, Zika virus (ZIKV) remains a public health concern with no treatment or vaccine available. Targeting a cellular pathway to inhibit viral replication is a potential treatment strategy that avoids development of antiviral resistance. We demonstrate in this study that the nontoxic autophagy-inducing disaccharide trehalose reduces spread and output of ZIKV in infected neural progenitor cells (NPCs), the major cells infected in the fetus. We show that ZIKV spreads cell-to-cell in NPCs as an infectious center and that NPCs are more permissive to infection by contact with infected cells than by cell-free virus. We find that neutralizing antibody does not prevent the spread of the infection in NPCs. These results are significant in demonstrating anti-ZIKV activity of trehalose and in clarifying the primary means of Zika virus spread in clinically relevant target cells.

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a positive single-stranded flavivirus that is transmitted by mosquito or sexually from person to person. This pathogen caused a widespread epidemic in 2015 to 2016 and has continued to spread at low levels (1, 2). Zika infection is associated with Guillain-Barre in adults (3, 4) and miscarriage or birth defects such as microcephaly, eye disorders, and neurodevelopmental delay in the case of infection during pregnancy (5–7). The virus can persist in the human body, and infectious virus can be shed in semen for weeks after illness (8). Many cases appear asymptomatic, creating the potential for spread, though significant variation in the reported percentage of asymptomatic infection exists (9). There is currently no approved vaccine or treatment for ZIKV, and details of the interaction between ZIKV and the host cell remain to be elucidated.

To better understand how ZIKV leads to neurological birth defects, multiple models of early neural developmental stages have been used to characterize the neurotoxic effects of African and Asian lineages of ZIKV. While African lineages promote apoptosis and cell death (10–12), Asian lineage ZIKV has been found to interfere with neural differentiation and limit growth of cells in multiple models of neuronal differentiation, including induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs), neurospheres, and animal models (13–17). In addition to being less cytotoxic, Asian lineage ZIKV replicates to lower titers than African lineages in multiple cell types (18), and of the various cell types observed, NPCs appear less permissive than the cell lines Vero, SK-N-SH, and U87-MG (19). A recent study indicates that sequence variation in structural proteins may be responsible for the differences in virulence and demonstrated the greater neurovirulence of the African lineage virus in a mouse model (20).

ZIKV infection affects cellular processes, including macroautophagy, promoting infection. Macroautophagy (referred to here as autophagy) is the process by which cellular components are directed to lysosomes for degradation (reviewed in reference 21). Autophagy is triggered by a low energy state in the cell, leading to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inactivation, or by cellular stress and results in the cargo being engulfed in double-membraned autophagosomes which fuse with lysosomes to degrade the cargo. Many viruses, including flaviviruses, interact with the autophagy pathway (reviewed in reference 22), and modulation of autophagy can support or limit the progression of viral infection, depending on the virus and the cell type. Dengue virus (23) can inhibit autophagy after an initial autophagy induction early in infection.

ZIKV infection has been shown to lead to induction of autophagy during infection of skin cells (24), umbilical vein endothelial cells (25), and neural stem cells (16), and it has been suggested that this promotes infection (reviewed in references 26 and 27). However, a recent study has shown that analogous to Dengue virus (23), autophagy is transiently induced by Zika virus in neuronal and glial cells early in the infection. At later times, there is activation of mTOR and inhibition of autophagy (28). Moreover, inhibition of mTOR and activation of autophagy suppress the infection. It has also been reported that autophagy is antiviral to ZIKV in the drosophila brain (29) and to another flavivirus, Japanese encephalitis virus (30). Thus, the question of whether autophagy is proviral or antiviral is an open one and requires careful consideration of the cell types and specific conditions promoting or inhibiting autophagy.

There are currently no approved antivirals for ZIKV, but potential therapies targeting viral or cellular processes are in various stages of development (31–33). Targeting a cellular pathway to limit virus infection is an attractive option due to the reduced chance of developing drug resistance. We have previously demonstrated that the autophagy-inducing disaccharide trehalose can reduce human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication in multiple primary cell types (34, 35). ZIKV relies on the autophagy pathway, and others have speculated that trehalose may limit vertical transmission of ZIKV (36).

Trehalose is an mTOR-independent autophagy-inducing disaccharide. It is blood-brain barrier-permeable and nontoxic. It shows promise as a potential therapeutic for several diseases, including protein aggregation diseases such as Huntington’s, ALS, and Parkinson’s (reviewed in reference 37). Trehalose has also been shown to be neuroprotective (38) and atheroprotective in models of diabetes and hypertension (39, 40). The mechanism by which trehalose induces autophagy is not completely clear, but it has been shown to induce transcription factor EB (TFEB) nuclear translocation and activation of TFEB’s transcriptional targets, which include genes involved in autophagy and lysosome biogenesis (41, 42). With respect to the inhibition of HCMV infection, we proposed that trehalose blocked virus production by redirecting virions to lysosomes for degradation (34, 35). More recently, studies have reported that trehalose inhibits HIV replication, and this is also associated with TFEB nuclear translocation and induction of autophagy-related gene expression (43, 44).

In the studies presented here, we used clinically relevant NPCs and recent Asian lineage ZIKV isolates from Panama (H/PAN/2016/BEI-259634) and Puerto Rico (PRVABC59) to show that treatment of ZIKV-infected NPCs with trehalose reduces viral output and spread of ZIKV. Additionally, we showed that ZIKV propagates through NPCs as a spreading infectious center and that cell-free virus appears to infect the NPCs inefficiently compared to contact with infected NPCs. This cell-to-cell spread is not prevented by neutralizing antibody.

RESULTS

ZIKV spreads cell-to-cell in NPCs.

Since NPCs are a known in vivo target of ZIKV, and infection of NPCs may be a contributing factor in the neurodevelopmental birth defects in congenital ZIKV syndrome, we focused our studies on this relevant cell type and used induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived NPCs to model infection in the developing brain. Cells were derived as described in Materials and Methods and stain positive for Pax6. Figure 1A shows the infection of these cells with ZIKV, as indicated by the costaining with antibodies to Pax6 and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). While establishing the parameters of infection of the NPCs, we observed by immunofluorescence that ZIKV spreads cell-to-cell as infectious centers (Fig. 1B). We also noted that the NPCs were infected at a significantly lower rate than expected from the multiplicity of infection, as calculated by a plaque assay on Vero cells.

FIG 1.

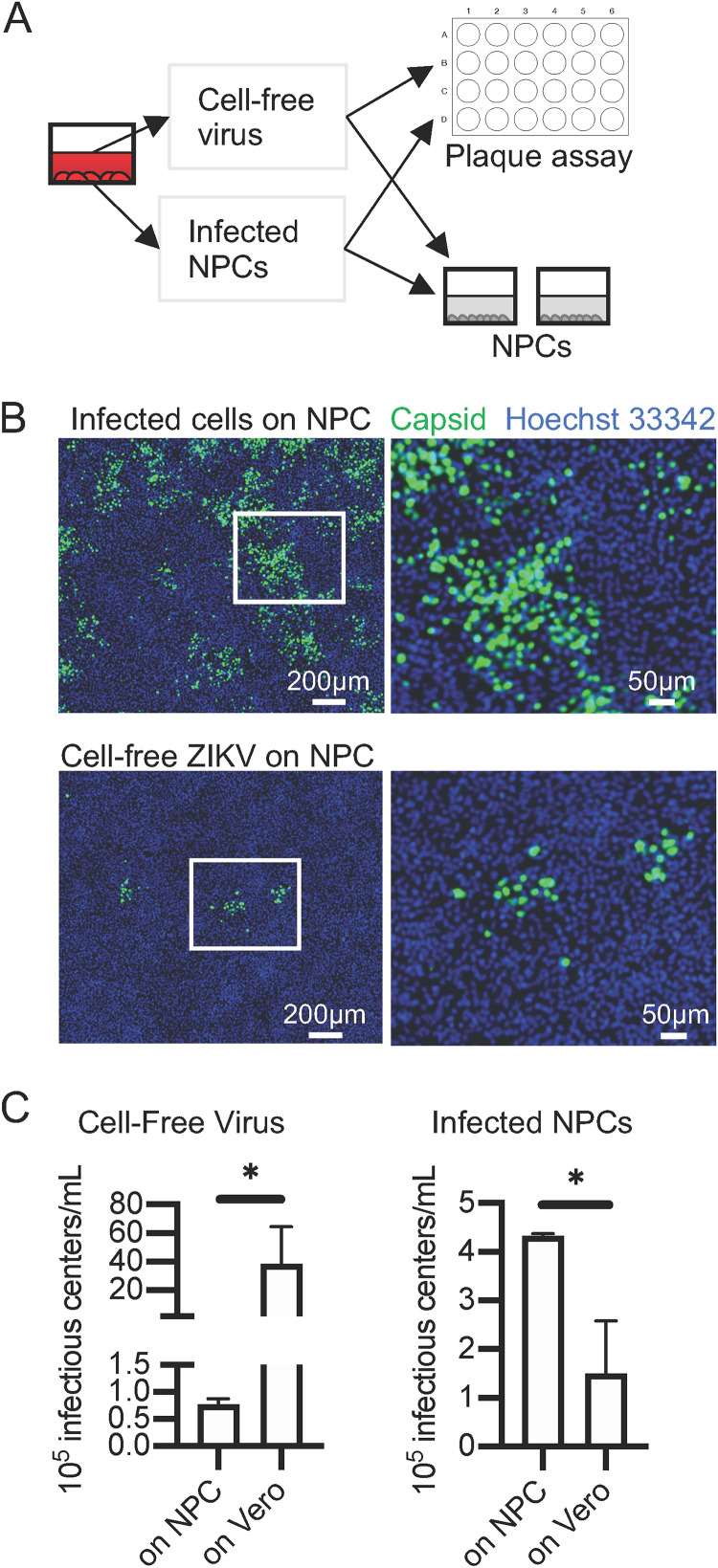

ZIKV spreads cell-to-cell in NPCs and infects NPCs less efficiently than Vero cells. NPCs (WT126) were infected 1 day postseeding on coverslips with ZIKV (PRV). Cells were washed at 2 hpi. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and processed for immunofluorescence with the indicated antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Images are representative of 2 independent experiments. (A) NPCs (WT126) were infected at an MOI of 5. At 72 hpi, cells were fixed for immunofluorescence with antibodies against Pax6 and dsRNA. (B) NPCs (WT126) were infected at an MOI of 0.5 with ZIKV (PRV). Cells were washed at 2 hpi, and medium was added and refreshed every day. Slips were fixed at the indicated times and stained with antibody against capsid protein. (C) Vero cells (top) or NPCs (WT126, bottom) were infected at an MOI of 0.5 on coverslips with ZIKV PRV. At 24 hpi, slips were fixed and stained with antibody against capsid protein. (D) Quantification of panel C. Infected cells were counted for 6 random fields per coverslip. Mean and SD of infected cells per field (left) and percentage infected (right) are displayed.

Lower permissivity of NPCs compared to Vero cells has been reported for Asian lineage isolates H/PF/2013 and ZIKVNL00013 (19), but the basis of this decreased permissivity was not established. To further investigate these observations, ZIKV PRVABC59 (PRV), isolated in Puerto Rico, was added to NPCs or Vero cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. At 24 h postinfection (hpi), cells were fixed and stained with antibody against capsid protein (Fig. 1C). Quantification of infected cells showed that the number of infected NPCs was 100 times lower than the number of infected Vero cells at 24 hpi (Fig. 1D).

Based on the observation that ZIKV appeared to spread through NPCs as an expanding infectious center, we suspected that contact with neighboring infected cells may result in more efficient infection than exposure to cell-free virus. We designed an experiment to address this hypothesis. NPCs and Vero cells were infected via two routes: (i) with cell-free virus produced in NPCs and (ii) via contact with infected NPCs. The resulting infections were compared to determine the efficiency of infection of NPCs by each route using the permissive Vero cells as a benchmark. Infections were quantified by counting the foci of infected NPCs (greater than 4 infected cells in the cluster) by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with antibody to capsid protein and by counting plaques on infected Vero cells in a standard plaque assay (diagrammed in Fig. 2A; IFA shown in Fig. 2B). Infections on NPCs were allowed to progress 48 h so that infectious center foci could be counted, ruling out the possibility that percentage infection is low at 24 hpi due to delayed initiation of infection. We observed that there were 50- to 100-fold fewer foci (infectious centers) after cell-free virus infection of NPCs than expected from the titer on Vero cells by plaque assay (Fig. 2C, left), suggesting that the 100-fold difference in infected NPCs at 24 hpi is not an artifact of delayed infection. We also observed that addition of infected NPCs appeared to produce more infectious centers on NPCs than they did on Vero cells as measured by plaque assay (Fig. 2C, right). Notably, the addition of infected cells to the NPCs was far more effective than addition of cell-free virus despite the higher titer of the cell-free virus measured on Vero cells. The foci of infectious centers on NPCs originating from infection by cells were also much larger (Fig. 2B) than those initiated by cell-free virus, suggesting that initiation of infection of NPCs via contact with an infected cell occurs much more efficiently or bypasses some antiviral step triggered by infection from cell-free virus.

FIG 2.

ZIKV infection via cell-cell spread is more effective than infection via cell-free virus. NPCs (WT126) were infected with ZIKV PRV. Infected cells or cell-free supernatants were subsequently transferred to uninfected NPCs on coverslips to visualize foci by IFA or quantified by plaque assay on Vero cells (diagrammed in panel A). At 48 hpi, NPCs on coverslips were fixed and stained with antibody against capsid protein and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 to visualize focal spread of infection (foci containing greater than 4 infected cells). (B) Representative fields. (C) The number of infectious centers (plaques on Vero cells and foci on NPCs) from infected NPCs for 4 cultures from 2 independent experiments. Means were compared by Mann-Whitney test. *, P < 0.05.

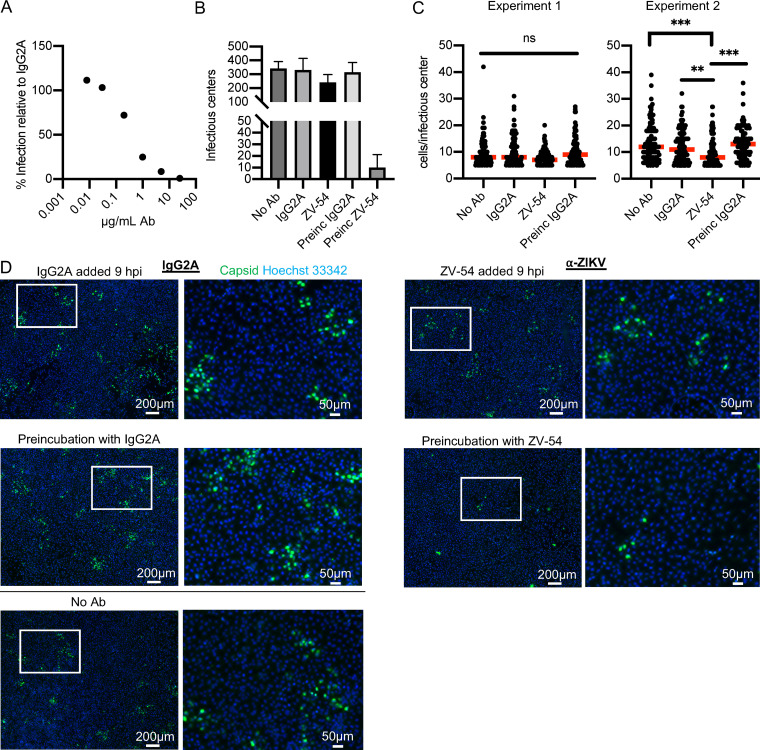

We next addressed whether ZIKV spread in NPCs could be restricted by the neutralizing antibody ZV-54, which has been shown to neutralize multiple strains of ZIKV (45). We established that the antibody neutralized virus by incubating 10,000 PFU of ZIKV with increasing concentrations of ZV-54 antibody or nonspecific IgG2A and performing a plaque assay on Vero cells. Increasing concentrations of ZV-54 resulted in increasing neutralization (Fig. 3A). The data are shown with respect to the nonspecific IgG2A, in which the expected PFU number represents 100% infection. There was no reduction in titer even at the highest concentrations of the nonspecific IgG2A. The concentration of 25 μg/ml reduced the number of PFU to 1% of IgG2A levels and was chosen for the neutralization assay in NPCs. We show the results of 2 independent experiments where multiple conditions were assayed. The neutralization assay was performed on NPCs by infecting them with 25,000 PFU for 2 h. Cells were then washed and incubated in growth medium to allow viral internalization and establishment of infection. At 9 hpi, 25 μg/ml of ZV-54 or nonspecific IgG2A control in growth medium was added, and coverslips were fixed at 48 hpi. Control wells received virus preincubated with 25 μg/ml ZV-54 or IgG2A control for 2 h or virus that had not been incubated with any antibody. Coverslips were stained for ZIKV capsid protein. Entire coverslips were imaged, and representative fields are shown in Fig. 3D. It should be noted that in the figure, a rare area of infected cells after virus that was preincubated with neutralizing antibody is shown for visualization purposes. Infectious centers (foci of greater than 4 infected cells) and cells per infectious center were counted. In Fig. 3B, the number of infectious centers per coverslip is shown as the mean and standard deviation (SD) of 2 to 3 experiments. As expected, preincubation of the virus with the antibody prior to infection decreased the number of foci 30-fold, but the addition of antibody at 9 hpi had no significant effect on the number of foci. For the data shown in Fig. 3C, cells per infectious center were counted for 100 randomly chosen infectious centers and are displayed as individual values with the medians (red bars) for two independent experiments. We have done this to show that in the first experiment, there was little difference in the number of cells/infectious center for all of the conditions—median of 7 cells for neutralizing antibody added at 9 hpi, median of 8 cells for control IgG2A antibody added at 9 hpi, median of 9 cells for control IgG2A preincubated with virus, and median of 8 cells for no antibody. In the second experiment, there is a small difference in the number of cells/infectious center when the cultures that had neutralizing antibody added at 9 hpi (median of 8 cells) are compared to those treated with either control IgG2A antibody added at 9 hpi (median of 11 cells), control IgG2A preincubated with virus (median of 13 cells), or no antibody (median of 12 cells). Because a large number of foci (100) were counted for each condition, the small difference reaches statistical significance. Taken together, these data show that the virus is able to spread in the presence of neutralizing antibody and provide additional evidence that ZIKV is primarily transmitted cell-to-cell in NPCs without exposure to the extracellular space, although a small amount of virus may be exposed to neutralizing antibody during the spread, leading to a slight reduction in the number of infected cells in each infectious center focus.

FIG 3.

ZIKV spreads in the presence of neutralizing antibody. (A) A total of 10,000 PFU of ZIKV (PRV) were incubated with increasing concentrations of ZV-54 ZIKV neutralizing antibody or IgG2A control for 1 h. Virus-antibody mixtures were serially diluted, and infectious titers were quantified by plaque assay on Vero cells. The graph shows the means of two experiments. (B to D) In 2 independent experiments, NPCs (WT126) on coverslips were infected with 25,000 PFU of ZIKV PRV. At 2 hpi, cells were washed and incubated with medium. At 9 hpi, cells were switched to medium with 25 μg/ml ZV-54 or control IgG2A. Control cells received virus that had been preincubated with 25 μg/ml ZV-54 or IgG2A control Ab (Preinc) or received virus with no antibody (No Ab). At 48 hpi, coverslips were fixed and stained for capsid protein. Images were acquired of entire coverslips. (B) The infectious centers per coverslip were counted and shown as the mean and SD of the 2 experiments. (C) The cells per infectious center were counted for 100 randomly chosen infectious centers and are displayed as individual values with the median (red bars) for two independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis test for significance and Dunn’s multiple-comparison test were applied. ns, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) Representative images of infectious centers are displayed.

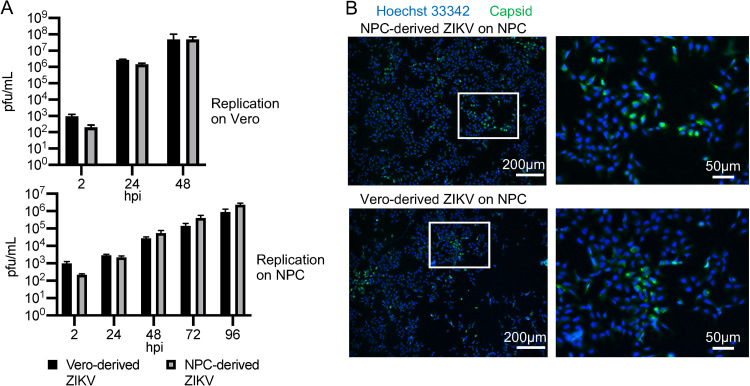

Both the cell-to-cell spread and the reduced infectivity of ZIKV on NPCs compared to Vero could be due to a tropism change during the first round of infection in NPCs, resulting in progeny virions that do not efficiently reinfect NPCs for subsequent rounds of infection. To address this question, we grew ZIKV in NPCs and in Vero cells and compared their respective growth kinetics on Vero cells and NPCs. Figure 4A (top) shows that NPC- and Vero-derived ZIKV have similar kinetics in Vero cells, as expected. Likewise, when we infected NPCs with NPC-derived and Vero-derived ZIKV, we observed no deficiency in the infection kinetics on NPCs with NPC-derived virus relative to Vero-derived virus (Fig. 4A, bottom). Figure 4B shows representative images of 48 hpi NPCs infected with NPC-derived (upper) and Vero-derived (lower) ZIKV. We can therefore conclude that the lower permissivity of NPCs compared to Vero cells is not due to a change in viral tropism early in infection.

FIG 4.

Low infectivity of NPCs compared to Vero is not due to changes in tropism of cell-free virus during replication in NPCs. (A) ZIKV (PRV) was propagated on NPCs (WT126) or on Vero cells, and the titers were quantified via plaque assay on Vero cells. Vero (top) or NPCs (WT126, bottom) were infected with virus derived from each cell type at an MOI of 0.5. Infected supernatants were collected every 24 h, and the titers were quantified on Vero cells. Graphs show the mean and SD from 3 cultures. (B) NPCs (WT126) were infected at an MOI of 0.5 with ZIKV PRV derived from NPCs (top) or Vero cells (bottom) on coverslips. At 48 hpi, coverslips were fixed and stained for capsid protein.

Trehalose reduces ZIKV production in NPCs.

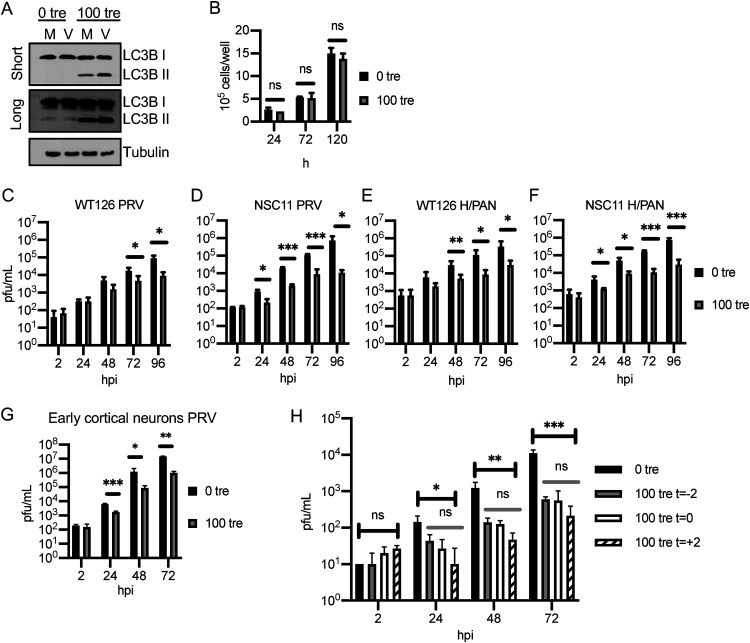

Trehalose has been widely used to induce autophagy in a variety of cell types, and we previously showed that 100 mM trehalose treatment greatly reduces replication of HCMV in multiple neural cell types at various points of differentiation, as well as primary fibroblasts and endothelial cells, with no toxicity (34). One method used to assess autophagy involves measuring the relative levels of both native (LC3B I, 18 kDa) and lipid-associated (LC3B II, 16 kDa) forms of LC3B by Western blotting. During autophagy, the cytosolic LC3B I form is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine to form LC3B II, which binds to the membranes of the phagophore, autophagosome, and autolysosome. Studies of multiple cell types have shown that 100 mM trehalose efficiently induces autophagy as measured by lipidation of LC3B I. To verify that the 100 mM trehalose induces lipidation of LC3B I to LC3B II in the NPCs used in these experiments and determine whether the viral infection would also have an effect, we assayed by Western blotting the amount of LC3B I and LC3B II in NPCs maintained in the absence (0 tre) and presence (100 tre) of 100 mM trehalose and either mock infected (M) or infected (V) with ZIKV (PRV) at an MOI of 5 (Fig. 5A). In this experiment, we used a higher MOI and harvested the cells at 72 hpi to ensure that all of the cells would be infected and there would not be a dilution effect if the viral infection affected the conversion of the cellular protein LC3B I to LC3B II. As expected, trehalose treatment significantly increased the levels of LC3B II. In untreated cells, the levels of LC3B II were very low, and there was no detectable increase in LC3B II in the infected cells (compare M and V at 0 tre). Moreover, the infection did not affect the accumulation of LC3B II in the presence of trehalose (compare M and V at 100 tre). As with previous neural cell types we have worked with, 100 mM trehalose does not affect the growth of the NPCs over multiple days of exposure (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Trehalose reduces ZIKV infection in neural lineage cells. (A) NPCs (WT126) were infected with ZIKV PRV at an MOI of 5 in the presence or absence of 100 mM trehalose. Cell pellets were collected at 72 hpi and processed for Western blot analysis using antibodies against LC3B and tubulin as the loading control. (B) Uninfected WT126 NPCs were treated with 100 mM trehalose beginning 1 day postplating. At the indicated times posttrehalose addition, cells were dissociated with Accutase and counted in Trypan blue to exclude dead cells. The graph shows the mean and SD of two cultures. A t test was performed at each time point. (C to G) NPC lines WT126 (C and E) and NSC11 (D and F) and early cortical neurons (G) were pretreated with 0 or 100 mM trehalose for 2 h. Cells were then infected with the indicated isolates of ZIKV at an MOI of 0.5 in the presence or absence of 100 mM trehalose. Medium with or without trehalose was refreshed, and supernatants were collected every 24 h, and the titers were quantified on Vero cells. The graphs show means and SD from 4 to 8 wells from 2 to 4 independent experiments (panels C to F) and of 2 to 3 cultures from 2 experiments (panel G). A t test was performed at each time point. (H) NPCs (WT126) were infected with ZIKV (PRV) at an MOI of 0.05. Trehalose was added 2 h before (t = −2), at the time of (t = 0), or 2 h after (t = +2) infection. Medium with or without trehalose was refreshed every 24 h. The graph shows the mean and SD of 3 cultures. Results were confirmed with a second independent experiment. At each time point, ordinary unpaired one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing all means was performed on log-transformed data (black bars). Additional ordinary unpaired one-way ANOVA compared means excluding 0 tre (absence of trehalose; gray bars). ns, P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To determine if trehalose negatively affects ZIKV replication, we examined the effect of 100 mM trehalose on ZIKV infection in NPCs. We tested two ZIKV isolates (PRV and H/PAN) and included two lines of NPCs (NSC11 and WT126; Fig. 5C to F). We also tested the effect of trehalose on infection of early cortical neuronal cells (Fig. 5G), which represent a clinically relevant cell type farther along the neuronal differentiation path toward cortical neurons compared with NPCs. Cells were infected at an MOI of 0.5 after 2 h of pretreatment with 100 mM trehalose. After a 2-h adsorption period, viral inocula were removed, and cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then once with medium. Medium with or without 100 mM trehalose was added and refreshed every 24 h throughout the experiment. Supernatants were collected every 24 h, and virus produced was measured by plaque assay on Vero cells. Trehalose treatment reduced the amount of infectious virus produced at least 10-fold in both lines of NPC and cortical neurons and with both isolates of ZIKV. In most cases, a statistically significant (P < 0.05) reduction was established early in infection and maintained over multiple time points (Fig. 5C to G). By 72 hpi, all cell types infected with either isolate showed statistically significant reduction.

In the above-described experiments, the cells were pretreated with trehalose for 2 h prior to infection. To determine whether trehalose had to be present at the beginning of the infection to reduce viral output, we varied the timing of trehalose addition, adding it to the cells at the time of infection, 2 h prior (as in Fig. 5C to G), or after viral adsorption and cell washing at 2 hpi. NPCs (WT126) were infected with PRV at an MOI of 0.05, and trehalose was added at the indicated times. Medium with or without trehalose was then refreshed every 24 h, and supernatants were collected and their titers were determined on Vero cells. We observed that adding trehalose after the adsorption period did not reduce the effect of trehalose on the progression of the infection and may modestly enhance the level of inhibition (Fig. 5H). Similar results were observed when the NPCs were infected at a higher MOI (data not shown). These results suggest that the major effect of trehalose is after the virus enters the cells.

Trehalose reduces viral production and spread at multiple MOIs in NPCs.

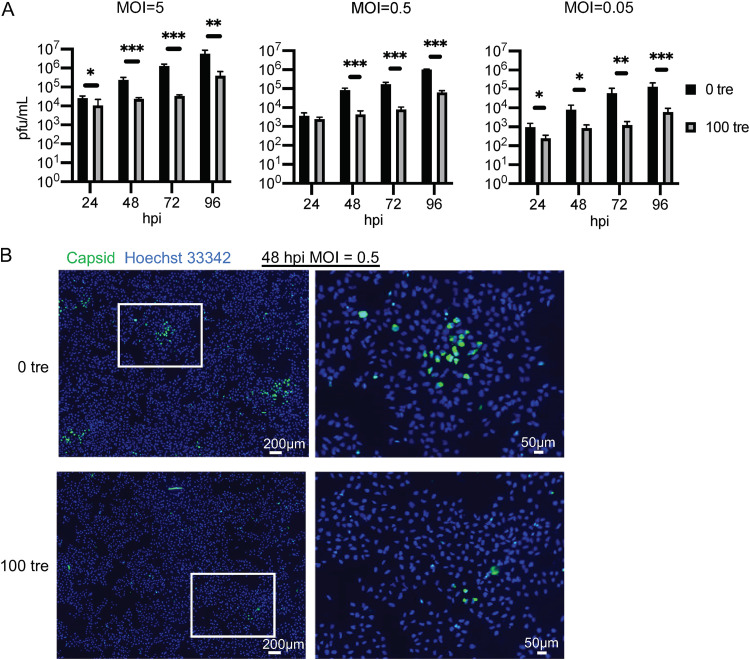

The effects of antivirals on infection may be influenced by the multiplicity of the infection, and higher-MOI infections can sometimes ameliorate the negative effects of an inhibitor. To address this question, we assessed the effect of trehalose in NPCs that were infected with ZIKV PRV at MOIs of 5, 0.5, and 0.05. Medium with or without 100 mM trehalose was added at 2 hpi after the input inoculum was removed. Supernatants were collected and medium with or without trehalose was refreshed every 24 h. NPCs were also cultured on coverslips, infected as above, and fixed at 48 hpi. Viral spread was visualized by staining coverslips with antibody to capsid protein. At low and high MOI, trehalose treatment reduced both release of virus (Fig. 6A) and viral spread (a representative IFA for the 0.5 MOI infection at 48 hpi is shown in Fig. 6B). In all cases, the titers were significantly lower (greater than 10-fold) by 48 hpi (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Trehalose treatment resulted in both fewer and smaller foci of infection at 48 hpi (Fig. 6B). The number of foci was reduced 7-fold in two independent experiments.

FIG 6.

Trehalose reduces ZIKV production and spread in NPCs at various MOIs. NPCs (WT126) were infected with ZIKV (PRV) at the indicated MOIs. After 2 h of adsorption, cells were washed and medium with or without 100 mM trehalose was added. Medium was refreshed every 24 h. (A) Infected supernatants were collected every 24 h, and the titer was quantified by plaque assay on Vero cells. Graphs show the means and SD of 3 to 4 cultures from 1 to 2 experiments. Significance was determined by t test at each time point for log-transformed data. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (B) NPCs (WT126) on coverslips were infected with ZIKV (PRV) at an MOI of 0.5. Coverslips were fixed at 48 hpi and stained for capsid protein. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342.

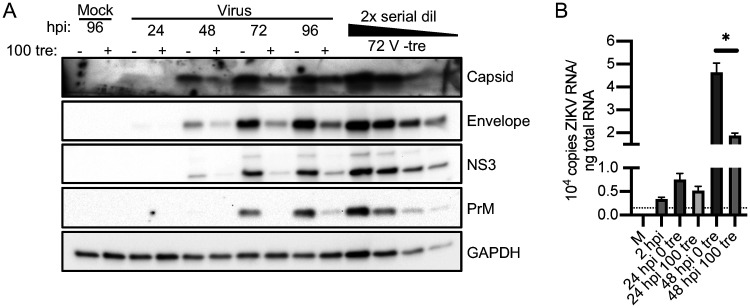

Trehalose treatment reduces viral protein levels and, to a lesser extent, viral RNA.

To determine the effect of trehalose on various steps of viral replication, we next assessed by Western blotting the levels of viral proteins in NPCs infected with ZIKV PRV at an MOI of 1 and treated with or without trehalose. Medium was refreshed and cell pellets were collected every 24 h. Trehalose treatment resulted in a reduction in levels of viral proteins (4- to 8-fold) at all time points (Fig. 7A). The Western blot includes a 2-fold serial dilution series of lysate to show the linear range of each antibody and allow estimation of fold reduction. We also quantified the level of intracellular viral RNA genomes in cells infected with ZIKV PRV at an MOI of 0.1 to ensure measurement of RNA levels at several time points prior to a plateau in untreated cells. Extracted total cellular RNA and an in vitro-synthesized RNA standard curve were reverse-transcribed with a sequence-specific ZIKV reverse transcriptase (RT) primer and detected by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Copies were normalized to GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Trehalose treatment induced approximately a 2.5-fold reduction in intracellular ZIKV RNA in NPCs at 48 hpi (Fig. 7B). This reduction in RNA levels reached statistical significance but was much less than the log reduction in viral titers, indicating that there may be several levels at which trehalose impedes ZIKV infection.

FIG 7.

Trehalose reduces ZIKV protein and RNA levels. WT126 NPCs were infected with ZIKV strain PRV at an MOI of 1 to follow the accumulation of viral protein (A) or 0.1 to follow the accumulation of viral RNA (B). At various times postinfection (p.i.), cell pellets were collected. (A) Pellets were processed for Western blotting using antibodies to detect viral capsid, envelope, NS3, and PrM and cellular GAPDH as the loading control. A 2× serial dilution of lysate indicates the range of each antibody. A representative blot of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Total RNA was extracted. The ZIKV genome and GAPDH cDNA were reverse-transcribed using sequence-specific primers. Copies of the ZIKV genome were quantified by qPCR via comparison to the standard curve of known copies of in vitro-synthesized ZIKV RNA subjected to the same reverse-transcription conditions as the samples. Copy numbers were normalized to GAPDH. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection. The graph shows the mean and SD of 2 experiments. A t test was performed at each time point. *, P < 0.05.

In summary, our data demonstrate that trehalose decreases ZIKV viral production and viral spread in NPCs and early cortical neurons. Viral proteins and RNA are reduced. We also show for the first time that ZIKV spreads inefficiently through the cell supernatant, and progression of the infection occurs via cell-to-cell spread. The finding that the presence of neutralizing antibodies does not prevent viral spread indicates that propagation of the infection can take place without exposure of the virus to the extracellular environment.

DISCUSSION

Targeting cellular processes as an antiviral strategy is attractive due to the reduced concern of antiviral resistance. Progress in this area includes several anti-ZIKV strategies (reviewed in references 31 to 33). These have included targeting nucleoside biosynthesis (46–50), preventing acidification of endosomes (51), and inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases (52). It was hypothesized that trehalose treatment could reduce ZIKV transmission to the fetus (36). In this study, we have demonstrated that trehalose significantly inhibits replication of ZIKV in NPCs and cortical neurons. As with our studies of HCMV, it appears that trehalose acts later in ZIKV infection, as addition of trehalose 2 h after the initiation of the infection did not reduce the inhibition, and we did not observe a major inhibition of viral RNA amplification compared to spread or viral titers.

The inhibitory effect of trehalose on ZIKV is interesting, as there are conflicting data regarding whether autophagy is proviral or antiviral for ZIKV. Some studies have shown that upregulating autophagy by treating infected cells with mTOR inhibitors increased viral infection, and inhibiting autophagosome formation with 3-methyladenine (3MA) and autophagosome degradation via chloroquine reduced infection (16, 24, 25, 53). In contrast, a recent study using neuronal and glial cells showed opposing results, with inhibition of mTOR suppressing the infection and inhibition of autophagosome formation with 3MA enhancing the infection (28). There are several possible reasons for trehalose having an antiviral effect in our studies. First, our studies, like those in reference 28, are conducted in neural cell types. Second, by activating autophagy for the duration of infection, trehalose may disrupt ZIKV’s use of autophagic membranes or maintain high levels of autophagy beyond those which are beneficial for ZIKV. Finally, the mechanism by which trehalose induces autophagy and the compound’s nonautophagy effects are not completely understood, and any of these effects may be unfavorable for the infection.

Trehalose is known to be mTOR-independent and causes localization of the transcription factor TFEB to the nucleus, initiating the proautophagy transcription program (54). Translocation of TFEB follows PIKFYVE activation and has been shown to be dependent on MCOLN1 (43). Transient lysosomal damage was implicated as a possible initiating factor in the translocation of TFEB (42). Trehalose-mediated interference with glucose uptake by blocking the glucose transporter SLC2A takes place in hepatocytes, leading to a starvation response (55, 56). However, this effect may be cell-type dependent, as we did not observe a reduction in glucose uptake in the presence of trehalose in primary human fibroblasts or aortic endothelial cells (35). We showed previously that trehalose treatment of primary human fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and neural cells at multiple stages of differentiation results in an increase in cytoplasmic vacuoles, acidification of cytoplasmic compartments, and an increase in autophagic flux (34). The lysosomal biogenesis protein Rab7 also increases in the presence of trehalose, consistent with an increase in lysosomes (35). Autophagy induced by trehalose has also been recently shown to inhibit HIV replication, and this is also associated with TFEB nuclear translocation and induction of autophagy-related gene expression (43, 44). It has been suggested that secretory autophagy may be involved in ZIKV spread (57). At 24 hpi in skin fibroblasts, ZIKV protein can be observed colocalizing with LC3-positive compartments (24). By increasing degradative autophagy, trehalose may redirect virions to lysosomes, as with HIV and, likely, HCMV, or otherwise restrict access of ZIKV to components of autophagy it might require for replication.

It is also possible that an autophagy-independent effect of trehalose or a nondegradation function of the upregulated autophagy pathway plays a role in the antiviral effect. Our data do not rule out a mechanism that does not directly involve autophagy. An anti-inflammatory effect of trehalose was demonstrated when trehalose treatment reduced transcript and protein levels of inflammatory secreted cytokines in ocular cells under tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and desiccation stress (58). One report suggested that trehalose exerts a protective function against oxidative stress independent of autophagy, as evidenced by its effect in ATG5−/− MEFs (59). Another demonstrated that trehalose raises levels of the neuroprotective glycoprotein progranulin (PGRN) independently of TFEB-mediated activation of autophagy (60). Other autophagy-inducing compounds had mixed results in our hands. SMER28 was strongly antiviral to HCMV by a different mechanism than trehalose (35) but had no effect on ZIKV replication in NPCs (data not shown). The short peptide inducer of autophagy, Tat-Beclin D11 (61) was toxic to NPCs at micromolar concentrations but reduced ZIKV replication in the glioblastoma cell line U87 (data not shown). Because it has been recently shown that ZIKV is highly pathogenic to cancer cells compared with nontransformed cells (62, 63), an anti-ZIKV mechanism in U87 cells may have little bearing on the infection in NPCs.

A surprising outcome of this study was the observation that ZIKV spreads almost exclusively cell-to-cell and that supernatant virus is comparatively noninfectious to the NPCs. Neutralizing antibodies prevented initial infection by cell-free virus, but they did not inhibit spread, although there was some reduction in the size of the foci. This indicates that there is a mechanism of spread that does not involve the viral surface antigen being exposed to the extracellular space. Flaviviruses may spread through exosomes and through tunneling nanotubes to neighboring cells. Exosome-mediated spread of ZIKV in cortical neurons has been demonstrated (64). While ZIKV spread through tunneling nanotubes has not so far been reported in the literature, West Nile virus has been shown to create structures appearing to be tunneling nanotubes in infected Vero E6 cells, and NS1 protein was sufficient to cause cytoskeleton reorganization (65). Discussions of cell-to-cell spread versus spread through cell-free virus suggest that cell-to-cell spread is favored when both permissivity to the virus and output PFU/cell are low (66, 67). In a report in which the authors were attempting to improve ZIKV production for downstream applications, it was noted that growing ZIKV in BHK-21 cells in suspension remained inefficient despite optimization (68), so it is possible that a preference for cell-to-cell spread exists in other cell types. Propagating ZIKV to high titers may not be easily accomplished using single cell suspension culture. Our data showing that adding infected cells to a culture of NPCs results in more, and larger, infectious centers indicates that infection through cell contact bypasses a barrier to the initiation of ZIKV infection in these cells. Dengue virus has also demonstrated a cell-to-cell spread pattern and may take place via autophagy-associated vesicles that are not sensitive to neutralizing antibodies (69). It is possible that trehalose promotes the fusion of these autophagy-associated vesicles with the lysosome, rather than allowing them to be used as vehicles of viral spread.

The antiviral effect of trehalose likely involves several of the above-discussed mechanisms or others that have not yet been reported. The mechanism by which trehalose induces autophagy and its other effects appear to be cell-type specific. It is clear that unlike other autophagy-inducing compounds, trehalose treatment has a negative effect on ZIKV replication in cells of neural lineages. As a compound known to be neuroprotective, it may be the basis of future therapies. Moreover, given its antiviral effect against several different viruses, it would be worthwhile to assess its activity against additional viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the newly emergent pathogen that is responsible for the current pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents.

Vero cells (ATCC CLL-81) acquired from ATCC were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 1 g of glucose per liter supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS), 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated newborn calf serum (HI-NCS), pen/strep, and 2 mM additional l-glutamine. Trehalose (Sigma; catalog no. T0167) was diluted directly in cell culture medium and filtered (0.22 µm).

Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) were the kind gift of Zhe Zhu. The WT126 line was derived in the lab of Alysson Muotri (62, 70). The NPCs were derived from iPSCs by culturing with SMAD inhibitors dorsomorphin and SB431542 for 2 days, scraping off colonies, and culturing as embryoid bodies (EB) for 7 days. EBs were plated and cultured with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF). After 7 days, rosettes were dissociated with Accutase and maintained with bFGF and EGF. They were cultured on Geltrex-coated plates and maintained in neurobasal medium supplemented with 1× B27, 1× N2, 1× GlutaMAX, pyruvate, and pen/strep with added EGF and FGF at 20 ng/ml each. They were passaged by dissociation with Accutase.

Day 22 cortical neurons were a kind gift from Gene Yeo, Florian Krach, and Stefan Aigner. They were derived and cultured as described previously (71) with modifications. Briefly, cells were differentiated from iPSCs by culturing in mTeSR medium (STEMCELL Technologies) containing 1 μM rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor for 1 day and then without ROCK inhibitor until 95% confluence. Neuronal induction was performed by culturing in neural maintenance medium (NMM) with SMAD inhibitor SB431542 and dorsomorphin derivative LDN193189. Forebrain priming was completed by incubating in dispase and then transferring cell clumps to poly-l-ornithine/laminin-coated plates in NMM with ROCK inhibitor and treated with FGF2 for 2 days. When rosettes appeared, FGF2 was withdrawn to induce neurogenesis, and cells were frozen after 10 days (day 22). These early cortical neurons were thawed and cultured on poly-l-ornithine/Geltrex-coated dishes. Rock inhibitor was removed at least 1 day prior to viral infections, and infections took place between day 3 and day 7 postthaw.

ZIKV preparation.

ZIKV human isolate H/PAN/2016/BEI-259634 (BEI Resources; catalog no. NR-50210) from Panama and human isolate PRVABC59 (BEI Resources; catalog no. NR-50240) from Puerto Rico were acquired from ATCC, distributed by BEI. Both were expanded on Vero cells to amplify titers, totaling 2 to 3 serial passages of the original stock. Infected cell supernatants were concentrated through a sucrose cushion, and concentrated virus was resuspended in neural maintenance medium base (50% DMEM/F12 Glutamax, 50% neurobasal medium, 1× N-2 supplement, 1× B-27 supplement, all from Life Technologies) supplemented with 1% DMSO and 5% FBS and stored at −80°C. Viral stock titers were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells and were greater or equal to 108 plaque forming units/ml. Mock medium was prepared by concentrating uninfected Vero cell medium as above.

Viral infections.

Infections on NPCs were carried out 1 day postplating. Virus was diluted in cell growth medium and added to cells. Unless otherwise indicated, virus was then removed 2 hpi, cells were washed with PBS, and medium was returned to cells with or without 100 mM trehalose.

Neutralization assay.

NPCs were seeded in 24-well plates with coverslips and infected 1 day postseeding with 25,000 PFU of ZIKV. Cells were washed, and medium was refreshed at 2 hpi. At 9 hpi, mouse IgG2a anti-ZIKV ZV-54 antibody (Millipore; catalog no. MABF2046) or nonspecific mouse IgG2a antibody (Millipore; catalog no. PP102) was diluted in culture medium at 25 μg/ml and added to cells. At 48 hpi, slips were fixed and processed for fluorescence microscopy. As a control, 25,000 PFU of virus was preincubated with no antibody, IgG2a anti-ZIKV ZV-54 antibody, or nonspecific mouse IgG2a antibody for 2 h at 37°C prior to addition to cells. The cells were washed as described above at 2 hpi and medium was refreshed with or without the same antibodies.

Absolute quantitation of ZIKV genomes.

A standard curve of ZIKV RNAs was created by in vitro transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. To create sense RNA standards to quantify genomes, primers 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGT GAA GCA CGG AGA TCT AGA AG-3′ and 5′-GAT CTT ACC TCC GCC ATG TT-3′ were used to amplify ZIKV H/PAN RNA extracted from infected U-87 MG cells while adding a T7 promoter. The amplified fragment was purified, verified by sequencing, and used as a template for T7 RNA polymerase (New England Biolabs; catalog no. M0251S). The resulting RNA was purified with a Zymo RNA clean and concentrate kit with a DNase step. Purified RNA formed a single band on agarose gel. This RNA was serially diluted 10-fold in the presence of 50 ng/μl carrier yeast tRNA (Life Technologies; catalog no. 15401011) to use as a standard.

RNA from infected cells was extracted and quantified so that genomes and not negative-strand intermediates are detected, as has been described previously for murine norovirus (72). RNA was extracted from cell pellets using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen), and 1 µg of total cellular RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript-III (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with ZIKV-specific primer, which added nonviral sequence (bold) 5′-CGGGAAGGC GACTGGAGTG CCCACCTGAC ATACCTTCCA CAAA-3′ to cDNA created from viral genome (sense strands) side by side with the serially diluted T7-synthesized RNA standard curve. Control reaction mixtures lacking the reverse transcriptase were performed. qPCR using primers that detect tagged ZIKV cDNAs (5′-CGGGAAGGCGACTGGAGTG-3′ and 5′-GGGAAGCTCAA CGAGCCAAA-3′ with probe 5′- CGGCA TACAGCATCA GGTGCATAGG AG-3′) was performed using a CFX96 thermocycler (Bio-Rad). All qPCRs included no RT and no template controls. Primers were chosen so that no differences between ZIKV isolates H/PAN and PRVABC59 would impact detection. Copy numbers per sample were normalized to GAPDH transcript levels. Sequence-specific GAPDH primer (5′-GCC ATG GGT GGA ATC ATA-3′) was used to generate GAPDH cDNA, and cDNA was detected with a qPCR using GAPDH TaqMan assay (Integrated DNA Technologies; catalog no. Hs.PT.39a.22214836).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Staining of NPC cells has been described (73). Briefly, cells cultured on coverslips were fixed for 15 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde. Slips were permeablized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, and primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution with 0.1% Triton-X were incubated on slips overnight at 4°C. After washing, secondary antibodies and Hoechst 33342 as a nuclear counterstain were incubated on coverslips 1 h at room temperature. Images were acquired on a Keyence BZX-700 epifluorescence microscope. Image processing was done in ImageJ so that no features were added or removed. Antibodies for immunofluorescence include anti-Pax6 (BioLegend; catalog no. 901301) 1:300, anti-dsRNA (rJ2; Kerafast; catalog no. ES2001) 1:40, and ZIKV capsid protein (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX133317) 1:300.

Protein gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Cell pellets were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies; catalog no. 9806) with SDS to 1% and 1× halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lysates were passed through a 22-gauge needle to disrupt genomic DNA. Protein was quantified with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and normalized. Then, 3× Laemmli buffer was added, and proteins were boiled 5 min. Samples were run on Tris-glycine precast gradient gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred in a wet transfer apparatus to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blots were blocked for 30 min in TBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) with 5% milk (or 5% BSA for anti-LC3B). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C or for 2 h at room temperature in 5% milk or 5% BSA in TBS-T as indicated by the manufacturer. Secondary antibodies were incubated in 5% milk at room temperature for 1 h. Blots were developed by West Pico ECL solution and visualized on a ChemiDoc system. Primary antibodies used for Western blotting included anti-ZIKV capsid protein (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX133317; 1:1,000), anti-ZIKV PrM (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX133305; 1:2000), anti-Envelope protein (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX133314; 1:2,000), anti-NS3 (GeneTex; catalog no. GTX133309; 1:2,000), anti-LC3B (D11 Cell Signaling Technologies; catalog no. 3868; 1:1,000), and anti-GAPDH (14C10 Cell Signaling Technology; catalog no. 2118; 1:2,000).

Statistical analysis.

Analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8. The figure legends specify which test was used. The random choice of infectious centers to count in Fig. 3 was achieved through the use of a random number generator in Microsoft Excel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jennifer Santini and Marcy Erb at the UC San Diego Microscopy Core for microscopy training and expertise, Christopher Morello for statistical guidance, and Stefan Aigner for expertise in culturing cortical neural cells.

This work was supported by NIAID grant AI129846 to D.H.S. G.W.Y. was partially funded by NIH grant U19 MH107367. Work at the UC San Diego Microscopy Core was funded by NINDS grant NS047101.

G.W.Y. is a cofounder, a member of the Board of Directors and the SAB, and an equity holder of Locana, as well as a paid consultant. G.W.Y.'s interest has been reviewed and approved by the University of California San Diego in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. We declare that we have no other competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weaver SC, Costa F, Garcia-Blanco MA, Ko AI, Ribeiro GS, Saade G, Shi PY, Vasilakis N. 2016. Zika virus: history, emergence, biology, and prospects for control. Antiviral Res 130:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 2019. Zika: the continuing threat. Bull World Health Organ 97:6–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastere S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, Dub T, Baudouin L, Teissier A, Larre P, Vial AL, Decam C, Choumet V, Halstead SK, Willison HJ, Musset L, Manuguerra JC, Despres P, Fournier E, Mallet HP, Musso D, Fontanet A, Neil J, Ghawché F. 2016. Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet 387:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbi L, Coelho AVC, Alencar LCAd, Crovella S. 2018. Prevalence of Guillain-Barre syndrome among Zika virus infected cases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Infect Dis 22:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chibueze EC, Tirado V, Lopes KS, Balogun OO, Takemoto Y, Swa T, Dagvadorj A, Nagata C, Morisaki N, Menendez C, Ota E, Mori R, Oladapo OT. 2017. Zika virus infection in pregnancy: a systematic review of disease course and complications. Reprod Health 14:28. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen-Saines K, Brasil P, Kerin T, Vasconcelos Z, Gabaglia CR, Damasceno L, Pone M, Abreu de Carvalho LM, Pone SM, Zin AA, Tsui I, Salles TRS, da Cunha DC, Costa RP, Malacarne J, Reis AB, Hasue RH, Aizawa CYP, Genovesi FF, Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Pereira JP, Gaw SL, Adachi K, Cherry JD, Xu Z, Cheng G, Moreira ME. 2019. Delayed childhood neurodevelopment and neurosensory alterations in the second year of life in a prospective cohort of ZIKV-exposed children. Nat Med 25:1213–1217. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0496-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrs C, Olson G, Saade G, Hankins G, Wen T, Patel J, Weaver S. 2016. Zika virus and pregnancy: a review of the literature and clinical considerations. Am J Perinatol 33:625–639. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1580089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mead PS, Duggal NK, Hook SA, Delorey M, Fischer M, Olzenak McGuire D, Becksted H, Max RJ, Anishchenko M, Schwartz AM, Tzeng W-P, Nelson CA, McDonald EM, Brooks JT, Brault AC, Hinckley AF. 2018. Zika virus shedding in semen of symptomatic infected men. N Engl J Med 378:1377–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haby MM, Pinart M, Elias V, Reveiz L. 2018. Prevalence of asymptomatic Zika virus infection: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 96:402–413D. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.201541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang J, Tiwari SK, Lichinchi G, Qin Y, Patil VS, Eroshkin AM, Rana TM. 2016. Zika virus depletes neural progenitors in human cerebral organoids through activation of the innate immune receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell 19:258–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, Yao B, Shin J, Zhang F, Lee EM, Christian KM, Didier RA, Jin P, Song H, Ming G-l. 2016. Zika virus infects human cortical neural progenitors and attenuates their growth. Cell Stem Cell 18:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodfellow FT, Willard KA, Wu X, Scoville S, Stice SL, Brindley MA. 2018. Strain-dependent consequences of Zika virus infection and differential impact on neural development. Viruses 10:550. doi: 10.3390/v10100550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Madeiro da Costa R, Higa LM, Trindade P, Delvecchio R, Nascimento JM, Brindeiro R, Tanuri A, Rehen SK. 2016. Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science 352:816–818. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcez PP, Nascimento JM, de Vasconcelos JM, Madeiro da Costa R, Delvecchio R, Trindade P, Loiola EC, Higa LM, Cassoli JS, Vitória G, Sequeira PC, Sochacki J, Aguiar RS, Fuzii HT, de Filippis AMB, da Silva Gonçalves Vianez Júnior JL, Tanuri A, Martins-de-Souza D, Rehen SK. 2017. Zika virus disrupts molecular fingerprinting of human neurospheres. Sci Rep 7:40780. doi: 10.1038/srep40780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Saucedo-Cuevas L, Regla-Nava JA, Chai G, Sheets N, Tang W, Terskikh AV, Shresta S, Gleeson JG. 2016. Zika virus infects neural progenitors in the adult mouse brain and alters proliferation. Cell Stem Cell 19:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang Q, Luo Z, Zeng J, Chen W, Foo SS, Lee SA, Ge J, Wang S, Goldman SA, Zlokovic BV, Zhao Z, Jung JU. 2016. Zika virus NS4A and NS4B proteins deregulate Akt-mTOR signaling in human fetal neural stem cells to inhibit neurogenesis and induce autophagy. Cell Stem Cell 19:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira RO, Garcez PP. 2019. Dissecting the toxic effects of zika virus proteins on neural progenitor cells. Neuron 101:989–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos da Silva S, Cheng F, Huang IC, Jung JU, Gao SJ. 2019. Efficiencies and kinetics of infection in different cell types/lines by African and Asian strains of Zika virus. J Med Virol 91:179–189. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anfasa F, Siegers JY, van der Kroeg M, Mumtaz N, Stalin Raj V, de Vrij FMS, Widagdo W, Gabriel G, Salinas S, Simonin Y, Reusken C, Kushner SA, Koopmans MPG, Haagmans B, Martina BEE, van Riel D. 2017. Phenotypic differences between Asian and African lineage Zika viruses in human neural progenitor cells. mSphere 2:e00292-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00292-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunes BTD, Fontes-Garfias CR, Shan C, Muruato AE, Nunes JGC, Burbano RMR, Vasconcelos PFC, Shi PY, Medeiros DBA. 2020. Zika structural genes determine the virulence of African and Asian lineages. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:1023–1033. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1753583: 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, Klionsky DJ. 2014. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res 24:24–41. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Echavarria-Consuegra L, Smit JM, Reggiori F. 2019. Role of autophagy during the replication and pathogenesis of common mosquito-borne flavi- and alphaviruses. Open Biol 9:190009. doi: 10.1098/rsob.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metz P, Chiramel A, Chatel-Chaix L, Alvisi G, Bankhead P, Mora-Rodriguez R, Long G, Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Bartenschlager R. 2015. Dengue virus inhibition of autophagic flux and dependency of viral replication on proteasomal degradation of the autophagy receptor p62. J Virol 89:8026–8041. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00787-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamel R, Dejarnac O, Wichit S, Ekchariyawat P, Neyret A, Luplertlop N, Perera-Lecoin M, Surasombatpattana P, Talignani L, Thomas F, Cao-Lormeau V-M, Choumet V, Briant L, Despres P, Amara A, Yssel H, Misse D. 2015. Biology of Zika virus infection in human skin cells. J Virol 89:8880–8896. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00354-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng H, Liu B, Yves TD, He Y, Wang S, Tang H, Ren H, Zhao P, Qi Z, Qin Z. 2018. Zika virus induces autophagy in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Viruses 10:259. doi: 10.3390/v10050259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiramel AI, Best SM. 2018. Role of autophagy in Zika virus infection and pathogenesis. Virus Res 254:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gratton R, Agrelli A, Tricarico PM, Brandao L, Crovella S. 2019. Autophagy in Zika virus infection: a possible therapeutic target to counteract viral replication. Int J Mol Sci 20:1048. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahoo BR, Pattnaik A, Annamalai AS, Franco R, Pattnaik AK. 2020. Mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling activation antagonizes autophagy to facilitate Zika virus replication. J Virol 94:e01575-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01575-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Gordesky-Gold B, Leney-Greene M, Weinbren NL, Tudor M, Cherry S. 2018. Inflammation-induced, STING-dependent autophagy restricts zika virus infection in the drosophila brain. Cell Host Microbe 24:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma M, Bhattacharyya S, Nain M, Kaur M, Sood V, Gupta V, Khasa R, Abdin MZ, Vrati S, Kalia M. 2014. Japanese encephalitis virus replication is negatively regulated by autophagy and occurs on LC3-I- and EDEM1-containing membranes. Autophagy 10:1637–1651. doi: 10.4161/auto.29455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mottin M, Borba JVVB, Braga RC, Torres PHM, Martini MC, Proenca-Modena JL, Judice CC, Costa FTM, Ekins S, Perryman AL, Andrade CH. 2018. The A-Z of Zika drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 23:1833–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baz M, Boivin G. 2019. Antiviral agents in development for Zika virus infections. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 12:101. doi: 10.3390/ph12030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou J, Shi PY. 2019. Strategies for Zika drug discovery. Curr Opin Virol 35:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belzile J-P, Sabalza M, Craig M, Clark E, Morello CS, Spector DH. 2016. Trehalose, an mTOR-independent inducer of autophagy, inhibits human cytomegalovirus infection in multiple cell types. J Virol 90:1259–1277. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02651-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark AE, Sabalza M, Gordts PLSM, Spector DH. 2017. Human cytomegalovirus replication is inhibited by the autophagy-inducing compounds trehalose and SMER28 through distinctively different mechanisms. J Virol 92:e02015-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02015-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan S, Zhang Z-W, Li Z-L. 2017. Trehalose may decrease the transmission of Zika virus to the fetus by activating degradative autophagy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:402. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosseinpour-Moghaddam K, Caraglia M, Sahebkar A. 2018. Autophagy induction by trehalose: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic impacts. J Cell Physiol 233:6524–6543. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee H-J, Yoon Y-S, Lee S-J. 2018. Mechanism of neuroprotection by trehalose: controversy surrounding autophagy induction. Cell Death Dis 9:712. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0749-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi S-K, Kwon Y, Byeon S, Lee Y-H. 2020. Stimulation of autophagy improves vascular function in the mesenteric arteries of type 2 diabetic mice. Exp Physiol 105:192–200. doi: 10.1113/EP087737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarthy CG, Wenceslau CF, Calmasini FB, Klee NS, Brands MW, Joe B, Webb RC. 2019. Reconstitution of autophagy ameliorates vascular function and arterial stiffening in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317:H1013–H1027. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00227.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmieri M, Pal R, Nelvagal HR, Lotfi P, Stinnett GR, Seymour ML, Chaudhury A, Bajaj L, Bondar VV, Bremner L, Saleem U, Tse DY, Sanagasetti D, Wu SM, Neilson JR, Pereira FA, Pautler RG, Rodney GG, Cooper JD, Sardiello M. 2017. mTORC1-independent TFEB activation via Akt inhibition promotes cellular clearance in neurodegenerative storage diseases. Nat Commun 8:14338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rusmini P, Cortese K, Crippa V, Cristofani R, Cicardi ME, Ferrari V, Vezzoli G, Tedesco B, Meroni M, Messi E, Piccolella M, Galbiati M, Garre M, Morelli E, Vaccari T, Poletti A. 2019. Trehalose induces autophagy via lysosomal-mediated TFEB activation in models of motoneuron degeneration. Autophagy 15:631–651. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1535292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma V, Makhdoomi M, Singh L, Kumar P, Khan N, Singh S, Verma HN, Luthra K, Sarkar S, Kumar D. 2020. Trehalose limits opportunistic mycobacterial survival during HIV co-infection by reversing HIV-mediated autophagy block. Autophagy 4:1–20. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1725374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rawat P, Hon S, Teodorof-Diedrich C, Spector SA. 2020. Trehalose inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in primary human macrophages and CD4(+) T lymphocytes through two distinct mechanisms. J Virol 94:e00237-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00237-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H, Fernandez E, Dowd KA, Speer SD, Platt DJ, Gorman MJ, Govero J, Nelson CA, Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. 2016. Structural basis of Zika virus-specific antibody protection. Cell 166:1016–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baz M, Goyette N, Griffin BD, Kobinger GP, Boivin G. 2017. In vitro susceptibility of geographically and temporally distinct Zika viruses to favipiravir and ribavirin. Antivir Ther 22:613–618. doi: 10.3851/IMP3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamiyama N, Soma R, Hidano S, Watanabe K, Umekita H, Fukuda C, Noguchi K, Gendo Y, Ozaki T, Sonoda A, Sachi N, Runtuwene LR, Miura Y, Matsubara E, Tajima S, Takasaki T, Eshita Y, Kobayashi T. 2017. Ribavirin inhibits Zika virus (ZIKV) replication in vitro and suppresses viremia in ZIKV-infected STAT1-deficient mice. Antiviral Res 146:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong X, Smith J, Bukreyeva N, Koma T, Manning JT, Kalkeri R, Kwong AD, Paessler S. 2018. Merimepodib, an IMPDH inhibitor, suppresses replication of Zika virus and other emerging viral pathogens. Antiviral Res 149:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rausch K, Hackett BA, Weinbren NL, Reeder SM, Sadovsky Y, Hunter CA, Schultz DC, Coyne CB, Cherry S. 2017. Screening bioactives reveals nanchangmycin as a broad spectrum antiviral active against Zika virus. Cell Rep 18:804–815. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrows NJ, Campos RK, Powell ST, Prasanth KR, Schott-Lerner G, Soto-Acosta R, Galarza-Munoz G, McGrath EL, Urrabaz-Garza R, Gao J, Wu P, Menon R, Saade G, Fernández-Salas I, Rossi SL, Vasilakis N, Routh A, Bradrick SS, Garcia-Blanco MA. 2016. A screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 20:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuivanen S, Bespalov MM, Nandania J, Ianevski A, Velagapudi V, De Brabander JK, Kainov DE, Vapalahti O. 2017. Obatoclax, saliphenylhalamide and gemcitabine inhibit Zika virus infection in vitro and differentially affect cellular signaling, transcription and metabolism. Antiviral Res 139:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu M, Lee EM, Wen Z, Cheng Y, Huang W-K, Qian X, Tcw J, Kouznetsova J, Ogden SC, Hammack C, Jacob F, Nguyen HN, Itkin M, Hanna C, Shinn P, Allen C, Michael SG, Simeonov A, Huang W, Christian KM, Goate A, Brennand KJ, Huang R, Xia M, Ming G-l, Zheng W, Song H, Tang H. 2016. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of Zika virus infection and induced neural cell death via a drug repurposing screen. Nat Med 22:1101–1107. doi: 10.1038/nm.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cao B, Parnell LA, Diamond MS, Mysorekar IU. 2017. Inhibition of autophagy limits vertical transmission of Zika virus in pregnant mice. J Exp Med 214:2303–2313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lotfi P, Tse DY, Di Ronza A, Seymour ML, Martano G, Cooper JD, Pereira FA, Passafaro M, Wu SM, Sardiello M. 2018. Trehalose reduces retinal degeneration, neuroinflammation and storage burden caused by a lysosomal hydrolase deficiency. Autophagy 14:1419–1416. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1474313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeBosch BJ, Heitmeier MR, Mayer AL, Higgins CB, Crowley JR, Kraft TE, Chi M, Newberry EP, Chen Z, Finck BN, Davidson NO, Yarasheski KE, Hruz PW, Moley KH. 2016. Trehalose inhibits solute carrier 2A (SLC2A) proteins to induce autophagy and prevent hepatic steatosis. Sci Signal 9:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Higgins CB, Mayer AL, Mysorekar IU, Razani B, Graham MJ, Hruz PW, DeBosch BJ. 2018. TFEB-dependent induction of thermogenesis by the hepatocyte SLC2A inhibitor trehalose. Autophagy 14:1959–1917. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1493044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Z-W, Li Z-L, Yuan S. 2016. The role of secretory autophagy in Zika virus transfer through the placental barrier. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6:206. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Panigrahi T, Shivakumar S, Shetty R, D’Souza S, Nelson EJR, Sethu S, Jeyabalan N, Ghosh A. 2019. Trehalose augments autophagy to mitigate stress induced inflammation in human corneal cells. Ocul Surf 17:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mizunoe Y, Kobayashi M, Sudo Y, Watanabe S, Yasukawa H, Natori D, Hoshino A, Negishi A, Okita N, Komatsu M, Higami Y. 2018. Trehalose protects against oxidative stress by regulating the Keap1-Nrf2 and autophagy pathways. Redox Biol 15:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holler CJ, Taylor G, McEachin ZT, Deng Q, Watkins WJ, Hudson K, Easley CA, Hu WT, Hales CM, Rossoll W, Bassell GJ, Kukar T. 2016. Trehalose upregulates progranulin expression in human and mouse models of GRN haploinsufficiency: a novel therapeutic lead to treat frontotemporal dementia. Mol Neurodegener 11:46. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0114-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shoji-Kawata S, Sumpter R, Leveno M, Campbell GR, Zou Z, Kinch L, Wilkins AD, Sun Q, Pallauf K, MacDuff D, Huerta C, Virgin HW, Helms JB, Eerland R, Tooze SA, Xavier R, Lenschow DJ, Yamamoto A, King D, Lichtarge O, Grishin NV, Spector SA, Kaloyanova DV, Levine B. 2013. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature 494:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu Z, Mesci P, Bernatchez JA, Gimple RC, Wang X, Schafer ST, Wettersten HI, Beck S, Clark AE, Wu Q, Prager BC, Kim LJY, Dhanwani R, Sharma S, Garancher A, Weis SM, Mack SC, Negraes PD, Trujillo CA, Penalva LO, Feng J, Lan Z, Zhang R, Wessel AW, Dhawan S, Diamond MS, Chen CC, Wechsler-Reya RJ, Gage FH, Hu H, Siqueira-Neto JL, Muotri AR, Cheresh DA, Rich JN. 2020. Zika virus targets glioblastoma stem cells through a SOX2-Integrin αvβ5 Axis. Cell Stem Cell 26:187–204.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu Z, Gorman MJ, McKenzie LD, Chai JN, Hubert CG, Prager BC, Fernandez E, Richner JM, Zhang R, Shan C, Tycksen E, Wang X, Shi P-Y, Diamond MS, Rich JN, Chheda MG. 2017. Zika virus has oncolytic activity against glioblastoma stem cells. J Exp Med 214:2843–2857. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou W, Woodson M, Sherman MB, Neelakanta G, Sultana H. 2019. Exosomes mediate Zika virus transmission through SMPD3 neutral Sphingomyelinase in cortical neurons. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:307–326. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1578188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Furnon W, Fender P, Confort M-P, Desloire S, Nangola S, Kitidee K, Leroux C, Ratinier M, Arnaud F, Lecollinet S, Boulanger P, Hong S-S. 2019. Remodeling of the actin network associated with the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of West Nile virus and formation of NS1-containing tunneling nanotubes. Viruses 11:901. doi: 10.3390/v11100901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhong P, Agosto LM, Munro JB, Mothes W. 2013. Cell-to-cell transmission of viruses. Curr Opin Virol 3:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mothes W, Sherer NM, Jin J, Zhong P. 2010. Virus cell-to-cell transmission. J Virol 84:8360–8368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nikolay A, Castilho LR, Reichl U, Genzel Y. 2018. Propagation of Brazilian Zika virus strains in static and suspension cultures using Vero and BHK cells. Vaccine 36:3140–3145. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu YW, Mettling C, Wu SR, Yu CY, Perng GC, Lin YS, Lin YL. 2016. Autophagy-associated dengue vesicles promote viral transmission avoiding antibody neutralization. Sci Rep 6:32243. doi: 10.1038/srep32243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marchetto MC, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Chen G, Gage FH, Muotri AR. 2010. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Livesey FJ. 2012. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc 7:1836–1846. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vashist S, Urena L, Goodfellow I. 2012. Development of a strand specific real-time RT-qPCR assay for the detection and quantitation of murine norovirus RNA. J Virol Methods 184:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belzile JP, Stark TJ, Yeo GW, Spector DH. 2014. Human cytomegalovirus infection of human embryonic stem cell-derived primitive neural stem cells is restricted at several steps but leads to the persistence of viral DNA. J Virol 88:4021–4039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03492-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]